Abstract

Background

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a common progressive neurodegenerative disorder that leads to an imbalance of various neurotransmitters and affects cognitive, motor and non-motor function. Safinamide inhibits monoamine oxidase B in a highly selective and reversible manner and beyond that has anti-glutamatergic properties, with positive effects on motor and non-motor symptoms. The aim of the study was to obtain data about the effectiveness and tolerability of safinamide under routine clinical practice conditions in unselected patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Methods

A post-hoc analysis of the German cohort of the European SYNAPSES study (a non-interventional cohort study). Patients were treated with safinamide as an add-on to levodopa and followed-up for 12 months. Analyses were done in the total cohort and in clinically relevant subgroups (patients older than 75 years; with relevant comorbidities; with psychiatric conditions).

Results

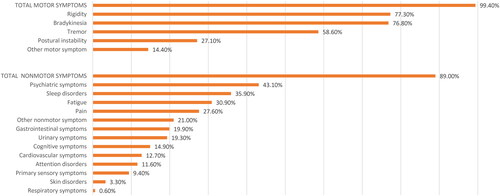

181 PD patients were eligible for analysis. Motor symptoms included bradykinesia (76.8%), rigidity (77.3%), tremor (58.6%), and postural instability (27.1%). Non-motor symptoms were reported in 161 patients (89.0%), mainly psychiatric symptoms (43.1%), sleep disorders (35.9%), fatigue (30.9%), and pain (27.6%). 28.7% of patients were aged 75 years or older, 84.5% had relevant comorbidities, and 38.1% had psychiatric conditions. During treatment, the rate of motor complications decreased from 100.0% to 71.1%. UPDRS scores improved under safinamide, with a clinically important effect in 50% in the total score and 45% in the motor score. The positive effect on motor complications occurred already at the 4-month visit and was maintained over 12 months. At least one adverse event (AE)/adverse drug reaction (ADR) was reported by 62.4%/25.4% of patients, AEs were generally mild or moderate, and completely resolved. Only 5 (1.5%) AEs had a definite relationship to safinamide.

Conclusions

The benefit-risk profile of safinamide was favourable and consistent with the total cohort of the SYNAPSES study. In the subgroups, findings were congruent with the total population, which allows the clinical utilisation of safinamide also in more vulnerable patient groups.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second-most common neurodegenerative disorder and affects predominantly persons at higher ages. In Germany, the German Society of Neurology assumed a crude prevalence in the population aged 65 years and older of 1800/100,000 personsCitation1. Based on recent population-based health claims data, the total number of patients with PD in Germany aged 50 years and older lies between 245,000 and 296,000 personsCitation2.

Neuropathological hallmarks of PD are neuronal loss in the substantia nigra, which causes striatal dopamine deficiency, and intracellular inclusions containing aggregates of α-synucleinCitation3. The imbalance of various neurotransmitters among and in PD patients is complex and heterogeneous and involves glutamate excitotoxicityCitation4.

Clinical diagnosis is mostly made on the presence of bradykinesia and other cardinal motor symptoms, but PD is associated with many non-motor symptoms that add to general disabilityCitation5. Treatment of PD is currently symptomatic and focusses on the pharmacological substitution of striatal dopamine. Device-based treatments such as continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion, levodopa-carbidopa and levodopa-carbidopa-entacapone intestinal gels delivered by a pump through a surgically placed percutaneous endoscopic jejunal tube, and deep brain stimulation are increasingly used in GermanyCitation6,Citation7.

The major unmet needs in the medical treatment of PD are reduction of motor complications coming from dopaminergic drugs, management of non-motor symptoms and disease modificationCitation8.

Safinamide is the only compound among the anti-parkinsonian drugs that combines both dopaminergic (MAO-B inhibition) and non-dopaminergic (anti-glutamatergic) properties in oneCitation9. The inhibition of MAO-B by safinamide is accomplished in a highly selective and reversible manner. This dopaminergic mode of action is accompanied by an activity-dependent blockage of voltage-dependent sodium channels, entailing the modulation of calcium channels, and as a consequence the inhibition of excess glutamate release in PD. Hence, the dual mechanism of action of safinamide facilitates the potentiation of dopamine and modulation of glutamate levels down to the physiological levelCitation10.

Owing to this unique specific pharmacological profile not shared by any of the other PD drugs, the Movement Disorder Society has placed safinamide in a class of agents different from selegiline and rasagilineCitation11.

Safinamide has been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of mid- to late-stage idiopathic PD patients with motor fluctuations as add-on therapy to a stable dose of levodopa alone or in combination with other PD medicationCitation12.

Safinamide is orally active and administered as a fixed dose (50/100 mg/d). In the clinical 24-week, placebo-controlled registration studies (016 and SETTLE), as an adjunct to levodopa, it significantly increased daily ON time with no troublesome dyskinesia in patients with mid- to late-stage PD with motor fluctuationsCitation13,Citation14. Further outcomes, including motor function and overall clinical status, were also improved. In the long-term studies, treatment benefits were sustained over 24 months of treatmentCitation15,Citation16. Several analyses of the registration studies and post-marketing studies support the finding that safinamide has sustained beneficial effects on non-motor symptoms including sleep, mood fluctuations, depression or pain, and health-related quality of lifeCitation15,Citation17–21. Safinamide is well tolerated; dyskinesia is the most common adverse eventCitation12.

Post-marketing studies have an important role for collecting data from everyday clinical practice in patient groups who were previously not studied or underrepresented, and from large populations to determine the risk-benefit profile of a drug in the long term. Such real-world evidence is useful for the generation of hypotheses, has an impact for new drug indications and label extensions, and may inform treatment guidelinesCitation22.

For safinamide, the EMA recommended during the approval process to collect such evidence in the form of a post-authorisation safety study (PASS). SYNAPSES (“European multicenter retrospective-prospective cohort StudY to observe safiNAmide safety profile and pattern of use in clinical Practice during the firSt post-commErcialization phaSe”) was a retrospective-prospective, non-interventional cohort studyCitation23, registered in the EU PAS Register under the identifier EUPAS-13745. The objective of SYNAPSES was to provide real-world data on the utilisation, safety and effectiveness in patients who are not well represented in clinical trials (those aged > 75 years, with psychiatric conditions or with relevant comorbidities such as depression, hypertension, heart diseases and metabolic disorders. The study was performed in 128 neurologic and geriatric sites with expertise in PD treatment in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Of the 1610 patients enrolled, 25.1% were over 75 years old, 70.8% had relevant comorbidities (hypertension and heart diseases in 37.8%, metabolic disorders in), and 42.4% had psychiatric conditions. In the 12 months after treatment initiation, 27.7% of patients experienced adverse drug reactions, which in most cases were mild or moderate and completely resolved. Clinically significant improvements were observed in the UPDRS motor score and in the total score in ≥40% of patients. Further, the rate of subjects with motor fluctuations decreased by 40–50% by study end in the course of the studyCitation23.

In Germany, 14 sites took part and contributed 189 PD patients (11.7% of the study cohort). As socioeconomic, cultural and other factorsCitation24 may influence the way in which PD is managed and PD medications are utilised, country-specific analyses are useful. The present paper describes the utilisation, effectiveness and safety of safinamide in the German cohort of the SNYAPSES study.

Methods

Design and patients

The study materials were approved by the local independent ethics committees and the study was performed in line with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the Declaration of Helsinki in its most recent version. We make reference to the recent publication of Abbruzzese et al. for an in-depth description of the study designCitation23. In brief, this was an open-label non-interventional study. Patients aged ≥18 were eligible, if they started treatment with safinamide at the enrolment visit or in the previous four months, with signed informed and privacy consent forms. Patients were not eligible if they were participating in any clinical trial with safinamide at study inclusion. Further, in Germany in compliance with §67 section 6 of the German Drug Law only patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PD were included for whom safinamide was prescribed in accordance with its summary of product characteristics (SmPC). It specifies that “Xadago® is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD) as add-on therapy to a stable dose of levodopa (L-dopa) alone or in combination with other PD medicinal products in mid-to late-stage fluctuating patients”Citation12. Thus, patients with PD were not eligible when being treated off-label or if they had contraindications to safinamide.

All patients were followed up for 12 months after the start of safinamide treatment. Data were recorded at the treatment start and at 4, 8, and 12 months thereafter. If a patient discontinued treatment with safinamide during the study, the observation continued. Data of patients enrolled at the start of treatment were prospectively collected. Otherwise, data of patients enrolled after the start of treatment were partially retrospective and updated in the continuum during the course of the study.

Outcome measures

The post-hoc analyses reported in this publication cover the data extracted from the German cohort of the SYNAPSES study. Data were analysed for the total cohort and for subgroups: patients aged ≥ 75 years, patients with relevant comorbidities and patients with psychiatric conditions. Evaluation of motor function was done through UPDRS III and total UPDRS scores during ON timeCitation25. The primary objective of the study was to describe the rate, type, severity and outcomes of adverse events (AEs) in patients treated with safinamide in real-life conditions for up to one year. The secondary objectives were to describe the characteristics of patients treated with safinamide according to clinical practice and to describe safinamide treatment patterns and outcomes in a real-life setting.

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis was done on all German “evaluable patients for the Full Analysis Set (FAS)” defined as the patients fulfilling all eligibility criteria and not violating any exclusion criteria. Descriptive statistics were used.

Categorical variables were described by means of absolute and relative frequencies, while continuous variables were done so by means of mean, standard deviation, quartiles, minimum and maximum values. Data collected on all patients were pooled for statistical analyses. Patients with missing values were not excluded from the analysis, and their data were not replaced or imputed; the frequency of missing data was given for all analysed variables.

Analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365 MSO (16.0.13801.21050) 32-bit, Version 2102.

Results

Demography

The patients’ overview is shown in . Of the 189 patients enrolled in Germany, 181 (95.8%) were eligible for the analysis (full analysis set), with 149 (78.8%) followed up prospectively for one year.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the total cohort and in subgroups of interest.

52 patients (28.7%) were older than 75 years, 153 patients (84.5%) had relevant comorbidities and 69 patients (38.1%) had psychiatric conditions. In the latter subgroup, mainly depression (30.9%) and behavioural disturbances (10.5%) were reported. Prevalent comorbidities were hypertension and heart diseases (45.3%), metabolic disorders (23.8%), joint, bone and pain disorders (18.2%), and hormonal disorders (14.9%).

The mean age at enrolment was 69.1 ± 8.7 years (). More males than females were enrolled (70.7% versus 29.3%). All patients were Caucasian (100.0%).

The mean age at the onset of first PD symptoms was 59.8 ± 10.5 years, the mean time since the onset of first symptoms 8.8 ± 6.6 years, and since PD diagnosis 7.2 ± 5.3 years.

displays the motor and non-motor symptoms of patients at baseline. Almost all patients had motor symptoms, specifically, bradykinesia (76.8%), rigidity (77.3%), tremor (58.6%), and postural instability (27.1%). Non-motor symptoms were reported in 161 patients (89.0%): mainly psychiatric symptoms (43.1%), sleep disorders (35.9%), fatigue (30.9%), and pain (27.6%).

Enrolled patients were mostly staged at Hoehn and Yahr 2 (54.10%). Mean Hoehn and Yahr stage was 2.5 ± 0.8, and 63 patients (42.6%) were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 3+. Mild cognitive impairment was reported in 18 (9.9%) patients, dementia in 3 (1.7%).

PD medication and safinamide utilisation

Previous and terminated PD drug treatments were reported in 54 patients (29.8%). Of these, 50 (27.6%) discontinued a MAO B-inhibitor, 2 (1.1%) a dopamine agonist and 2 (1.1%) a catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor before starting treatment with safinamide and having been enrolled into the SYNAPSES study. Five (2.8%) of the patients even changed their L-dopa preparation before enrolment

All patients (100.0%) received levodopa at the start of safinamide therapy (). In addition, 106 (58.6%) received a dopamine agonist, 76 (42.0%) a COMT inhibitor, 40 (22.1%) amantadine, and 3 patients (1.7%) anticholinergics. None received a MAO-B inhibitor (rasagiline, selegiline). Further, 10 patients (5.5%) had a medical device (deep brain stimulator).

Table 2. Concomitant PD treatments at the start of safinamide.

In the group of psychiatric medications, antidepressants were given in 39 patients (21.5%), antipsychotics in 16 (8.8%), procholinergics in 3 (1.7%), and other psychiatric drugs in 25 patients (13.8%). The range of given antidepressants included SSRI (8.3%), SNRI (2.2%), tricyclic agents (0.6%) and others (12.7%; e.g. mirtazapine in 10.5%).

Safinamide treatment was initiated in all patients with the 50 mg tablet once daily. Over the course of the observation, 112 (61.9%) reported at least one dose increase. Treatment was temporarily interrupted in 8 patients (2.4%).

Safety profile of safinamide

During observation, 113 patients (62.4%) experienced at least one adverse event (AE) (29 patients a serious AE, 16.0%) and 46 (25.4%) experienced at least one adverse drug reaction (ADR) (5 patients a serious ADR, 2.8%) (). The monthly incidence rate for ADR was very low (0.04; 95% CI 0.03–0.5). Adverse events were mainly mild (53.6%) or moderate (35.2%). The distribution of AE by severity and by system organ class (SOC) are shown in .

Table 3. AEs and SAEs overview in the FAS and relevant subgroups.

Table 4. Fluctuations at the start of treatment with safinamide and during the follow-up.

The majority of AEs fell into the SOC of nervous system disorders, with a total number of 80 AEs reported in this category, corresponding to 24.2% of all AEs (). Breaking down all covered SOCs to specific symptoms/medical conditions the most frequently reported AEs, albeit none of them reached the 5%-threshold, were: hallucinations (4.8%), tremor (3.3%), dyskinesia (3.0%), hypokinesia (2.7%), falls (2.4%), constipation (2.1%), and fatigue (1.8%).

Table 5. Distribution of adverse events (AE) severity by system organ class.

In terms of outcomes, 158 AE (47.9%) had recovered, 5 (1.5%) were recovered with sequelae, 125 (37.9%) were not recovered, 13 (3.9%) were recovering at the last report, and 2 (0.6%) AE were fatal.

The relationship between the AE and safinamide was considered to be definitive in 5 cases (1.5%), probable in 19 (5.8%), possible in 35 (10.6%), unlikely in 17 (5.2%), and not related in 254 (77.0%).

As the action in response to the AE, safinamide was temporarily interrupted in 8 cases (2.4%), permanently discontinued in 28 (8.5%), and the dosage reduced in 17 (5.2%). No action was taken in 274 cases (83.0%).

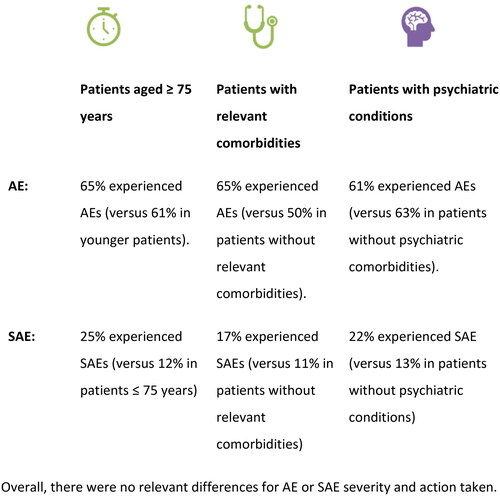

A graphical summary of AE and SAE by subgroup of interest is displayed in .

UPDRS scores

After 12 months treatment with safinamide, compared to baseline, 50% of patients showed a clinically relevant difference in the UPDRS Total Sore (≥ 4.3 points according to the criteria developed by ShulmanCitation25 and 45% in the UPDRS Motor Examination Score (≥ 2.5 points) ().

Table 6. UPDRS scores.

Motor fluctuations

All patients reported motor complications at study entry, with wearing off (78.5%) being the most frequent one, followed by early morning fluctuations (33.1%) and dyskinesia (27.6%) (). During treatment, the rate of patients with fluctuations decreased steadily. More than a quarter of patients (28.9%) did not have any motor complication at 12 months. The improvements seen after 4 months indicate a rapid onset of the effectiveness of safinamide and are maintained in the long term.

Subgroups of interest

The subgroup of patients with comorbidities was considerable, overlapped largely with the FAS (84.5%) and was generally similar in characteristics. The subgroup of patients with psychiatric conditions was about a third of the FAS and comprised a higher proportion of females (39.1% versus 29.4%). The “elderly patients” subgroup was by definition older than the FAS (mean age 79.7 versus 69.1 years), but otherwise similar in characteristics ().

In terms of tolerability, the rate of patients with at least one AE was similar in the subgroup of patients aged 75+ years compared to the FAS (65.4% versus 62.4%); and the rate of patients with at least on SAE was higher (25.0% versus 16.0%, ). Similar findings were noted for ADR and Serious ADR. Also, in the other subgroups of interest, the rates of SAEs and SADRs were somewhat higher compared to patients in the FAS. The pattern of AE by SOC, severity, causal relationship and action taken did not differ much between the subgroups. No new safety signal was detected.

Discussion

The current analysis on a geographically defined subgroup of the SYNAPSES study provides evidence about the real-world use of safinamide in Germany overall, and also in clinically relevant subpopulations of patients in higher age groups, those with psychiatric conditions, or with relevant comorbidities. Safinamide was well tolerated and effective in the total group and the three subgroups of interest.

Compared to the full SYNAPSES data set, we identified some differences in the patient profilesCitation23. In Germany, a higher proportion of patients were males (70.7% versus 61.7%), While the proportion of males is somewhat higher than in the total SYNAPSES study (61.7%), it is in line with the overall picture. PD affects men twice more often than womenCitation26. Further, in the present subset most patients were in the higher Hoehn & Yahr stages III-IV (42.6% 84% versus 70.8% in the full data set), while the other characteristics were similar.

According to the prescribing information, the recommended starting dose of safinamide is one 50 mg tablet daily that may be increased to one 100 mg. The registration studies complemented by the post-marketing studies have shown a greater efficacy on motoric as well as non-motor symptoms for the 100 mg doseCitation12,Citation13. In practice, nearly two-thirds of patients (62%) received the full dose, while the dose decreases (from 100 mg/d back to 50 mg/d), and temporary interruptions were infrequent.

Overall, safinamide was well tolerated, and no major or unexpected safety signals were noted. The overall AE pattern was in line with the one described in the package leaflet.

The rate of patients who experienced at least one AE was higher compared to the international total SYNAPSES cohort (62.4% in Germany versus 45.8% overall), but the rate of patients with an ADR was similar (25.4% in Germany versus 27.7% in the total cohort)Citation23. Compared to the earlier pivotal (registration) studies, the rate of patients with AE was substantially lower in the SYNAPSES study (European and German data), which is noteworthy as the clinical studies owing to their strict inclusion and exclusion criteria usually document patients who have less comorbidities. The relationship between the AEs and safinamide was considered to be definitive in 1.5% of all patients in the German group which was lower as in the overall population (2%).

Dyskinesia only accounted for 3.0% of AEs in the German cohort, and therefore at a much lower frequency compared to the total SYNAPSES cohort (13.7%) and compared to the previous pivotal trials (18%).

No serotonergic syndrome occurred among the patients (21.5%) who were taking antidepressants additionally. The high selectivity towards MAO-B of safinamide as seen in no other MAO- B inhibitor provides an extra safety aspectCitation27,Citation28.

In terms of effectiveness, UPDRS scores improved under safinamide, with a clinically important effect in 50% in the total score and 45.0% in the motor score after 12 months of treatment. As the annual decline is about 5–6 points in early untreated PDCitation29 and about 3.3 points for the UPDRS motor score under dopaminergic therapiesCitation30, the addition of safinamide to levodopa antagonises the progressive deterioration of function in a substantial proportion of patients. Early morning fluctuations among the German patients were more frequent than in the total SYNAPSES cohort (33.1% versus 23.3%), while unpredictable fluctuations were less frequent (9.4% versus 16.9%). The rate of patients affected by such motor complications decreased to a similar extent in the German and the total cohort. The effect occurred early at 4 months and was maintained long-term. Remarkable percentage improvements were seen in all categories of motor fluctuations, especially Dyskinesia (56%), delayed on fluctuations (55.6%), wearing-off (42.3%), unpredictable fluctuations (41.2%) and early morning fluctuations (40%).

Methodological considerations

When interpreting the results of the present study, methodological considerations need to be taken into account. The study used an observational design, which may lead to an unquantifiable bias in the selection of PD patients (i.e. underrepresentation of critically ill individuals)Citation31. Further, neurologists and geriatricians willing to participate in the survey are likely to represent a selection of physicians with a particular interest and knowledge in the field of PD management. It is known that adherent patients are more likely to provide their informed consent for study participationCitation32.

The study cohort here is relatively small, which limits its ability to identify new safety signals substantially. According to the “rule of three”, three times as many subjects must be followed in order to observe an event when it is assumed that the adverse event of interest does not normally occur in the absence of the medicationCitation33.

Among the strengths of the study are its coverage of all regions in Germany, and its strong focus on the ambulatory setting rather than on university or specialist centers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results from the present long-term non-interventional study demonstrate the sustained effectiveness and good tolerability of safinamide in addition to levodopa (given as specified in the SmPC) in the treatment of patients with PD over a 12-month period. Of note, motor complications and UPDRS motor score improved substantially and were maintained in the long term, which makes the agent appropriate for patients with motor fluctuations in L-dopa-treated patients. The benefit-risk profile of safinamide remains favourable and is consistent with the benefit-risk ratio evaluated during other studies of the drug. In patients from subgroups of interest (elderly; with psychiatric conditions; with comorbidities) findings were congruent with the total population, which allows the clinical utilisation of safinamide also in more vulnerable patient groups.

Transparency

Author contributions

All authors contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics statement

The study was designed, in agreement with the European Agency (EMA), to investigate how safinamide is prescribed and used in routine clinical practice and to collect safety and effectiveness data. Both protocol and patient materials were approved by Independent Ethics Committees and Health Authorities of the participating countries. All patients signed informed and privacy consent forms and the study was conducted according to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Personal data were collected, stored, and processed exclusively in pseudonymized form and in compliance with the regulatory requirements for the protection of confidentiality of patients. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Trial registration

EUPAS-13745 https://www.encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=41165 Registered 9. June 2016.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the investigators and the patients involved in the trial. In Germany, the following investigators contributed to the study: Blersch WK, Delf M, Hellwig B, Herbst HP, Kupsch A, Jost WH, Lang M, Muhlack S, Nastos I, Oehlwein C, Schlegel E, Schwarz J, Warnecke T, Woitalla D.

Declaration of funding

The SYNAPSES study was funded by Zambon S.p.A, the present analysis by Zambon GmbH, Berlin, Germany.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Wolfgang H. Jost has received consultancy fees from Zambon. Ivonne Gluth, Jennifer C. Lück, Olga I. Fonseca da Cruz Lopes are employees of Zambon. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation upon request.

References

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (DGN). S3 guideline idiopathic parkinson syndrome. 2016 (currently under revision). AWMF Registry no: 030-010. Internet. [cited 2023 Jan 24]. Available from: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/030-010

- Nerius M, Fink A, Doblhammer G. Parkinson’s disease in Germany: prevalence and incidence based on health claims data. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(5):386–392. doi: 10.1111/ane.12694.

- Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, et al. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17013. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13.

- Wang J, Wang F, Mai D, et al. Molecular mechanisms of glutamate toxicity in Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:585584. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.585584.

- Titova N, Qamar MA, Chaudhuri KR. The nonmotor features of Parkinson’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;132:33–54.

- Richter D, Bartig D, Jost W, et al. Dynamics of device-based treatments for Parkinson’s disease in Germany from 2010 to 2017: application of continuous subcutaneous apomorphine, levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel, and deep brain stimulation. J Neural Transm. 2019;126(7):879–888. doi: 10.1007/s00702-019-02034-8.

- Nyholm D, Jost WH. Levodopa-entacapone-carbidopa intestinal gel infusion in advanced Parkinson’s disease: real-world experience and practical guidance. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2022;15:17562864221108018. doi: 10.1177/17562864221108018.

- deSouza RM, Schapira A. Safinamide for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(9):937–943. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1329819.

- Blair HA, Dhillon S. Safinamide: a review in Parkinson’s disease. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(2):169–176. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0408-1.

- Muller T. Safinamide in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2020;10(4):195–204. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2020-0017.

- Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Lim SY, et al. International Parkinson and movement disorder society evidence-based medicine review: update on treatments for the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2018;33(8):1248–1266. doi: 10.1002/mds.27372.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Xadago (Safinamide) summary of product characteristics [Internet]. London: EMA; 2015. [cited 2023 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/xadago.

- Schapira AH, Fox SH, Hauser RA, et al. Assessment of safety and efficacy of safinamide as a levodopa adjunct in patients with Parkinson disease and motor fluctuations: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(2):216–224. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4467.

- Borgohain R, Szasz J, Stanzione P, et al. Randomized trial of safinamide add-on to levodopa in Parkinson’s disease with motor fluctuations. Mov Disord. 2014;29(2):229–237. doi: 10.1002/mds.25751.

- Cattaneo C, Jost WH, Bonizzoni E. Long-term efficacy of safinamide on symptoms severity and quality of life in fluctuating Parkinson’s disease patients. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(1):89–97. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191765.

- Borgohain R, Szasz J, Stanzione P, et al. Two-year, randomized, controlled study of safinamide as add-on to levodopa in mid to late Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29(10):1273–1280. doi: 10.1002/mds.25961.

- Cattaneo C, Barone P, Bonizzoni E, et al. Effects of safinamide on pain in fluctuating Parkinson’s disease patients: a post-hoc analysis. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7(1):95–101. doi: 10.3233/JPD-160911.

- Cattaneo C, Sardina M, Bonizzoni E. Safinamide as add-on therapy to levodopa in mid- to late-stage Parkinson’s disease fluctuating patients: post hoc analyses of studies 016 and SETTLE. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6(1):165–173. doi: 10.3233/JPD-150700.

- Geroin C, Di Vico IA, Squintani G, et al. Effects of safinamide on pain in Parkinson’s disease with motor fluctuations: an exploratory study. J Neural Transm. 2020;127(8):1143–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00702-020-02218-7.

- Liguori C, Stefani A, Ruffini R, et al. Safinamide effect on sleep disturbances and daytime sleepiness in motor fluctuating Parkinson’s disease patients: a validated questionnaires-controlled study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018;57:80–81. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.06.033.

- Jost WH, Kupsch A, Mengs J, et al. Effectiveness and safety of safinamide as add-on to levodopa in patients with Parkinson’s disease: non-interventional study. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2018;86:624–634.

- Mofid S, Bolislis WR, Kuhler TC. Real-world data in the postapproval setting as applied by the EMA and the US FDA. Clin Ther. 2022;44(2):306–322. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.12.010.

- Abbruzzese G, Kulisevsky J, Bergmans B, et al. A european observational study to evaluate the safety and the effectiveness of safinamide in routine clinical practice: the SYNAPSES trial. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(1):187–198. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202224.

- GBD 2016 Parkinson’s Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:939–953.

- Shulman LM, Gruber-Baldini AL, Anderson KE, et al. The clinically important difference on the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(1):64–70. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.295.

- Cerri S, Mus L, Blandini F. Parkinson’s disease in women and men: what’s the difference? [review]. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019;9(3):501–515. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191683.

- Fariello RG. Safinamide. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4(1):110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2006.11.011.

- Onofrj M, Bonanni L, Thomas A. An expert opinion on safinamide in Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17(7):1115–1125. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.7.1115.

- Poewe W, Mahlknecht P. The clinical progression of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15(Suppl 4): S28–S32. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70831-4.

- Schrag A, Dodel R, Spottke A, et al. Rate of clinical progression in Parkinson’s disease. A prospective study. Mov Disord. 2007;22(7):938–945. doi: 10.1002/mds.21429.

- Delgado-Rodriguez M, Llorca J. Bias. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(8):635–641. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.008466.

- van Onzenoort HA, Menger FE, Neef C, et al. Participation in a clinical trial enhances adherence and persistence to treatment: a retrospective cohort study. Hypertension. 2011;58(4):573–578. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.171074.

- Onakpoya IJ. Rare adverse events in clinical trials: understanding the rule of three. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23(1):6. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110885.