Abstract

Objective

Describe and characterize treatment patterns, satisfaction, improvement in pain and functional impairment (health-related quality of life [HRQoL]) in users of over the counter (OTC) Voltaren gel diclofenac (VGD) 2.32% and 1.16% in a real-world setting.

Methods

This observational real-world German study had prospective and retrospective components. The prospective data were collected from electronic surveys completed by adults who purchased VGD to treat their musculoskeletal pain at baseline and 4 and 12 weeks after baseline. Retrospective data were from a 12-month (March 2019 to February 2020) abstraction from dispensing software platforms used in select German pharmacies.

Results

Surveys from 467 participants (mean age 60.8 years) were analyzed. Average pain severity at baseline was 6.0 on an 11-point Numeric Rating Scale (0 = no pain, 10 = worst possible pain), improving by 0.8 and 1.2 points at Weeks 4 and 12, respectively. Performance of functional activities (daily/physical/social activities and errands/chores) improved and the proportion of participants with at least moderate interference decreased at both follow-up timepoints. Retrospective analyses indicated that majority of patients receiving VGD (n = 95,085) were ≥65 years old (67.9%), had one dispensed tube (70.8%) and did not switch to another topical treatment (including other NSAIDs) (77.3%), and were co-prescribed at least one cardiovascular medication (74.3%).

Conclusions

This study provides the first real-world insights into OTC VGD use in Germany. The participants using VGD reported a decrease in pain severity and an improvement of HRQoL while under treatment, as well as resulting satisfaction with treatment. Patients infrequently switched to alternate topical therapies/NSAIDs.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal pain, including low back pain, neck pain, fractures, injuries, and osteoarthritis, is a prevalent condition, affecting about 1.7 billion people worldwide in 2019Citation1–3. One type of musculoskeletal pain, acute low back pain, has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 80% of adults in GermanyCitation4. As the world’s population ages, the prevalence of pain is projected to rise as it is primarily reported by working-aged people and the elderlyCitation5,Citation6. Reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and day-to-day decline in function and mobility are commonly associated with musculoskeletal painCitation7, which is among the leading causes of severe HRQoL impairment worldwideCitation4. Pain can be responsible for decreasing independence and decreasing functional capacityCitation8,Citation9. Current international guidelines and definitions of pain imply that treatment should go beyond the reduction of pain intensity and should improve wellbeing and the patient’s ability to participate in lifeCitation10,Citation11. To achieve these expectations and advance critical medical objectives, musculoskeletal pain management must be effective.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) applied topically have been found to be equally as effective as oral drug preparations at treating acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain through randomized, double blind, active-controlled trialsCitation10,Citation11. The topical route of administration maximizes local delivery and minimizes systemic exposure, thereby reducing the risk of systemic side effects (e.g. gastrointestinal [GI] and cardiovascular [CV] complications) and potential drug-drug interactions traditionally associated with oral drug preparationsCitation12–14. Therefore, topical NSAIDs may be of particular benefit to populations with comorbidities, such as older adultsCitation15. Of the available topical NSAIDs, Voltaren gel diclofenac (VGD) formulation has high clinical efficacy in acute musculoskeletal pain with the lowest number needed to treat (NNT) of 1.8 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5–2.1)Citation14. In Germany, VGD is available as an over the counter (OTC) topical treatment, under the brand names Voltaren Schmerzgel (1.16%) and Voltaren Schmerzgel forte (2.32%) for the symptomatic treatment of pain from acute bruising, strains or sprains as a result of blunt trauma, e.g. sports injuries or accidents. The 1.16% strength is also indicated for osteoarthritic pain of the knee and finger joints, pain on the outside of the elbow (epicondylitis) and muscle pain in the back. Despite the fact that topical analgesics are widely used and typically sold OTC, there is limited information about how they are being used in the real world, factors that may influence their usage, and the characteristics of said users.

Several randomized, double blind, placebo and active-controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of VGD in relieving pain associated with musculoskeletal disordersCitation16–20; however little is known about usage patterns in the OTC setting, patient satisfaction with the treatment results, and impact on their daily lives. This observational study aimed to investigate the real-world benefit of VGD use through a hybrid approach using prospective surveys to evaluate satisfaction, pain relief and impact on HRQoL for adults who purchased topical VGD 1.16% or 2.23% OTC in a self-care setting, and a retrospective secondary analysis of pharmacy dispensing records to describe dispensing patterns of VGD OTC alone or with other medications.

Study methods

The study had two components: (1) prospective survey of German adults (referred to throughout as “participants”) who purchased VGD 1.16% or VGD 2.32% OTC (GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare a Haleon Company) and (2) retrospective analysis of VGD 1.16% and 2.32% OTC sales from pharmacy dispensing records (referred to throughout as “patients”) in Germany.

Prospective survey about topical VGD treatment

The prospective participant survey was developed to characterize treatment satisfaction, functional impairment, and pain severity across 12 weeks after VGD purchase. The brand name Voltaren Schmerzgel was used throughout the participant survey to align with the name participants are most familiar with. Three surveys (baseline, Week 4, and Week 12) were developed by the study team and translated into German. Usability, comprehension of the survey instructions and questions, appropriateness of response options, and technical functionality of the electronic surveys were tested, in German, during cognitive debriefings with 10 adults who used VGD in the previous six months. Changes were made to the surveys following the cognitive debriefings and the final surveys were linguistically validated by a second independent translation agency. The final baseline survey included 16 questions on demographics, reason for treatment, relevant medical comorbidities, VGD strength purchased and purchase history (new vs repeat user), other pain treatments, pain severity, pain continuity, and pain-related functional impairment (ability to perform daily activities, errands and chores in and around the house, physical activities, and social activities i.e. HRQoL). The HRQoL items were adapted from the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)Citation21 and the Pain Disability Index (PDI)Citation22 instruments. The follow-up surveys (Weeks 4 and 12) included 11 questions covering concepts repeated from the baseline survey (pain severity, HRQoL), with additional items on satisfaction with treatment result and in pain relief. The recall period for pain and functional interference items was the previous week.

Pain severity was evaluated using a Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), which is commonly used to assess pain. The NRS ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain)Citation23. NRS scores for pain were categorized as mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), and severe (7–10), based on clinical practice documented in previous studiesCitation24–26.

Functional impairment, functional improvement (compared to before using VGD), and satisfaction with treatment results were assessed with Likert-type questions. These survey items and scoring are presented in .

Table 1. Functional impairment and select satisfaction follow-up survey items.

Participants were recruited in two waves: in-person at select physical German pharmacies from December 2020 to February 2021 (wave 1) and through an online German pharmacy from November 2021 to February 2022 (wave 2). In wave 1, staff at local pharmacies invited consumers to participate immediately following purchase of VGD. In wave 2, consumers received a study leaflet in their purchased VGD parcel inviting them to participate. Potential participants in both waves could scan a QR code or enter a URL to go to the study website to complete the study eligibility screener. The screening questions assessed the following inclusion criteria: (1) ability to provide informed consent; (2) willingness and availability to complete electronic surveys over 12 weeks, with the first survey to be completed within five days of VGD purchase; (3) purchase or repurchase of VGD 1.16% or 2.32% OTC for immediate self-use; (4) plan to start (or continue) VGD use within five days of purchase; and (5) are at least 18 years old. The decision to treat their condition with VGD, and the actual usage according to the product label, was at the participant’s discretion. After providing consent, participants then entered their contact information to receive an e-mail or text message with a personalized link to complete the electronic baseline survey. The Week 4 and Week 12 personalized links were sent to the same contact details at the appropriate time, with a reminder to maximize responses. Survey responses were collected without participant-identifying information. Participants could withdraw at any time. Participants were compensated according to fair-market value after completing the three surveys.

Retrospective data analysis of topical VGD sales

Data for the retrospective analysis of VGD dispensing in Germany were obtained through dispensing software platforms used in certain German community pharmacies that had opted-in and consented to share data with third parties. The dataset represented approximately 13% of Germany’s total number of pharmacies and contained a geographically diverse sample of longitudinal pharmacy data from different regions in Germany. The data contained information on all drugs that were available for dispensing in community pharmacy but did not differentiate between prescriptions provided by primary care versus specialists or OTC purchase based on patient request or healthcare practitioner recommendation (e.g. pharmacist or physician recommendation via green prescriptions in Germany, so called “Grünes Rezept”). The software provider was responsible for sharing data that complied with German regulations. The data cut from 1 March 2019 to 29 February 2020 contained de-identified patient-level data with the following variables: patient identification, year of birth, gender, product code so called “Pharma-Zentral-Nummer (PZN),” brand name, product description, manufacturer and quantity dispensed.

Ethics and regulatory authority reviews

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA) code of conduct ensuring compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and all European data protection requirements. There was no basis for submission to an ethics committee in Germany as the prospective study did not meet the criteria per German Drug Law. However, the prospective and retrospective components were submitted to a central institutional review board (IRB) in the United States (US) for review. The IRB reviewed and approved the prospective analysis based on English documents and signed attestation that German language documents translations were accurate. For the retrospective component, a determination of non-human subject research was delivered since the dataset was going to be anonymized and no human subjects were directly involved in the study.

German regulatory (German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices [BfArM]) and health insurance associations (Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung [GKV], Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung [KBV], and private Krankenversicherung [PKV]) were notified of the study per German Medicinal Act §67 para. 6.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were calculated, including frequencies and percent for categorical variables and means with standard deviations (SD), median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum for continuous variables.

The prospective analyses were conducted using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). There were no formal statistical comparisons or hypotheses to be tested. Target survey sample sizes were calculated based on precision calculations for level of satisfaction and attrition rates at Week 4 and Week 12 (n = 600 and n = 360, respectively). Higher-than-expected completion rates of the follow-up surveys meant fewer participants than predicted needed to be enrolled in the study. Subgroup analyses, including by age (≥65 vs. ≤64 years old), were performed.

The retrospective analyses were conducted with Python-SQL. Medications were identified using PZN drug codes. The number of days between refills (gap) was calculated by subtracting the supply duration (calculated based on the VGD pack size and recommended total daily dose for each formulation strength) from the number of days between refills (calculated by dispensing dates). Due to the cross-sectional nature of the analysis resulting in a variation of observed time across the records, the VGD gap and switch analyses were conducted relative to whether the first dispensing was filled within the first three months (before month 4), or first six months (before month 7) in the 12-month observational period.

Results

Prospective participant survey about VGD pain severity, pain interference and treatment satisfaction

Disposition and baseline demographics

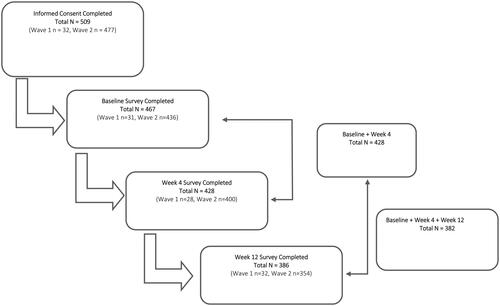

Overall, 509 participants consented to participate in the prospective study. Of those, 467 (91.7%) completed the baseline survey, 428 (84.1%) completed the Week 4 survey, and 386 (75.8%) completed the Week 12 survey. Longitudinally, 428 (91.6%) completed the baseline and Week 4 surveys and 382 (81.8%) completed all three surveys. Any patient who did not complete the baseline survey and complete a follow-up survey was removed from the analysis ().

Of the 467 participants who completed the baseline survey, the mean (SD) age was 60.8 (15.3) years, 43.5% were ≥65 years old (range 18 to 92), and 46.0% were female. Nearly half of the participants (47.1%) reported having underlying CV disease (heart problems, high blood pressure) and 3.2% reported an underlying GI disorder (stomach or intestinal ulcers, bleeding from stomach, or blood in stools).

Baseline pain severity, management and functional impairment

Participants reported purchasing VGD to treat pain such as body pains not specific to arthritis (39.8%), back pain (23.8%), and arthritis pain (12.4%), while 24.0% purchased it for treating sports or accidental injuries.

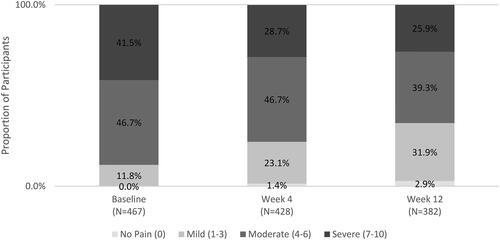

Participants reported pain severity across the NRS, with 11.8% reporting mild pain (1–3), 46.7% reporting moderate pain (4–6), and 41.5% reporting severe pain (7–10). The mean (SD) worst pain in the previous week was 6.0 (1.9) on the NRS, indicating high moderate pain.

The majority (70.9%) of participants purchased VGD 2.32% strength. More than three-quarters of all participants had previously purchased VGD (77.5%) in the 12 months prior to study participation. The most common reason provided by participants for re-purchase was related to the perceived effectiveness of VGD (86.5%). More than one-third (37.7%) of the participants reported using other pain treatment products to treat the same condition in the four weeks prior study start, with ibuprofen tablets being the most commonly used.

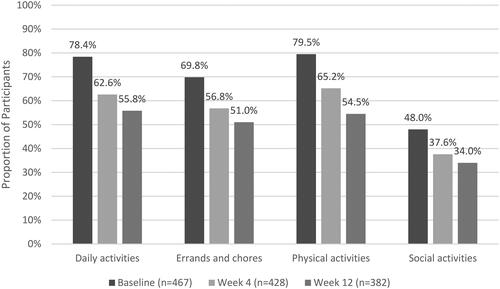

Most participants reported that their pain interfered at least “moderately” with their physical activities (79.5%), daily activities (78.4%), and errands and chores (69.8%), while slightly less than half (48.0%) reported the same level of interference with social activities.

Pain relief, pain severity and functional impairment at weeks 4 and 12

Reported pain relief and pain severity

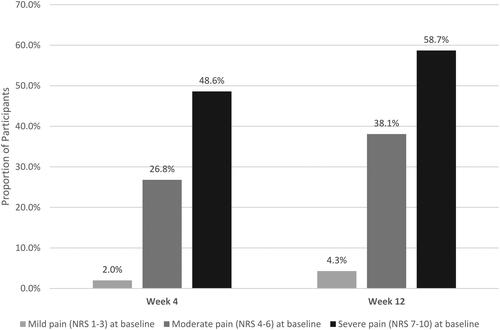

Mean (SD) worst pain score on the NRS decreased over time, with an overall change of −1.2 from baseline to Week 12. Mean (SD) worst pain score at Week 4 was 5.1 (2.2), corresponding to a mean reduction of 0.8 from baseline. The mean (SD) worst pain score at Week 12 was 4.7 (2.4), representing a further reduction in mean pain of 0.4 from Week 4. By Week 12, more than one-third (34.8%) of participants reported no or mild pain on NRS ().

Figure 2. Percentage of Survey participants reporting pain on NRS pain Scale.

Scores are based on the pain NRS, with 0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain.

Among all participants, 32.7% improved to a less severe pain category (from mild at baseline to no pain; from moderate at baseline to mild or no pain; from severe at baseline to moderate, mild, or no pain) at Week 4, and 42.4% at Week 12. Participant changes by pain level are presented in . Among participants who started with moderate or severe pain (NRS 4–10), 36.8% moved to a less severe pain category by Week 4 and 47.6% by Week 12.

Reported improvement in functional impairment

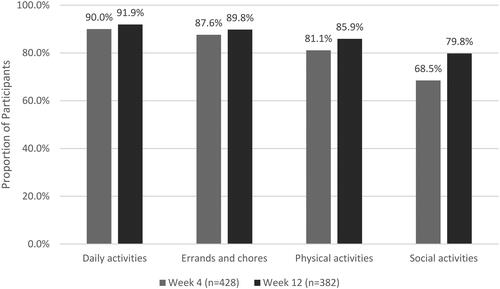

Overall, there was an improvement in participants’ ability to participate in functional activities (). Improvement was defined as selecting “A little better,” “Much better,” or “Very much better” when asked to describe their ability to participate in functional activities compared to baseline.

Figure 4. Percentage of Survey participants with improvement in ability to participate in functional activities from baseline to weeks 4 and 12.

Improvement defined as selecting ‘A little better’, ‘Much better’, or ‘Very much better’ when asked to describe ability to participate in functional activities compared to baseline.

Among participants who reported at least “Quite a bit” of interference at baseline, most improved in the ability to participate in daily activities (87.1% at Week 4 and 88.7% at Week 12), errands and chores around and outside the home (82.1% at Week 4 and 84.6% at Week 12), physical activities (75.6% at Week 4 and 80.5% at Week 12), and social activities (65.1% at Week 4 and 74.4% at Week 12). The proportion of participants who reported at least “Moderate” interference with functional activities at baseline decreased over the course of the study ().

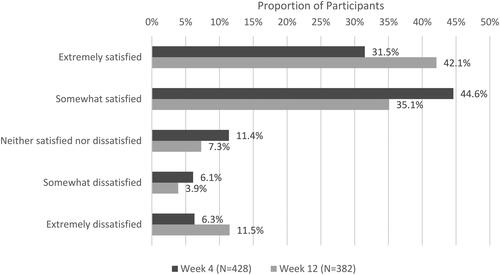

Reported treatment satisfaction

More than three-quarters of participants were “Somewhat” or “Extremely” satisfied with VGD treatment results (76.2% at Week 4; 77.2% at Week 12) ().

Participants reported that VGD helped them “maintain their social independence” (i.e. do not need to ask for help, feel in control, carry out daily activities, participate in recreational activities, or stay social) (92.3% at Week 4; 92.5% at Week 12). Participants also reported that they were satisfied with VGD treatment because it was “easy to use” (81.6% at Week 4; 77.6% at Week 12) and “it helps me carry out normal daily activities” (76.7% at Week 4 and 76.3% at Week 12) (). The participants who reported “Quite a bit” or “Extreme” interference with functional activities (daily activities, errands and chores, physical activities, and social activities) at baseline also reported that they were “Somewhat” or “Extremely” satisfied with treatment result at Week 4 and Week 12 ().

Table 2. Reasons for satisfaction with VGD treatment results among survey participants.

Table 3. Satisfaction with VGD treatment results for survey participants with "quite a bit” or “extreme” interference with functional activities at baseline.

Use of VGD among older adults (≥65 years old)

Among the 203 elderly participants (aged ≥65 years), 87.2% reported that the purchase of VGD at study baseline was a repurchase, which was higher than the rate for the full study sample. About two-thirds (65.5%) of the older participants reported being told by their doctor that they had underlying CV disease and 3.0% reported underlying GI disorders.

Participants ≥65 years old selected the following reasons for satisfaction with treatment results at Week 4 and Week 12, respectively: “It helps me carry out my normal daily activities” (74.6% and 82.1%); “It helps me to avoid having to go to my doctor to get a treatment” (47.7% and 50.4%); “It makes me feel I can take care of myself as I do not need to ask for help” (34.6% and 49.6%); “It helps me to be able to participate in recreational activities” (48.5% and 54.7%).

Among participants ≥65 years old, improvements were seen in ability to participate in daily activities (87.9% at Week 4, 92.9% at Week 12), errands and chores (85.7% at Week 4, 89.1% at Week 12), physical activities (75.8% at Week 4, 85.3% at Week 12), and social activities (70.9% at Week 4, 82.7% at Week 12) compared with baseline. Results for participants aged 18 to 64 and those ≥65 years old are presented in .

Table 4. VGD Use, pain, and treatment satisfaction results between older and younger survey population.

Adverse events

Adverse events reported by study participants that met minimum criteria to identify health and safety incidents were reported by the study data control partner according to standard pharmacovigilance processes. There was one non-serious adverse event reported during the study. The adverse event reported was exacerbation of underlying pain.

Secondary retrospective data analysis of topical VGD Sales

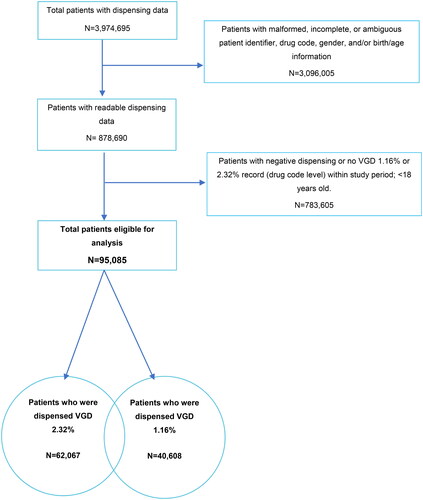

A total of 3,974,695 patients (96,449,144 records) were identified in the dispensing software platform dataset between 1 March 2019 and 29 February 2020. Records that were malformed, incomplete, or missing key information were excluded from the analyses. Patients <18 years of age and patients who did not have records in the 12-month observation period or who did not have at least one dispensing of VGD 1.16% or 2.32% were also excluded. The final analysis population consisted of 95,085 patients (2,327,901 records), including 62,067 who were dispensed VGD 2.32% and 40,608 who were dispensed VGD 1.16%; some patients were dispensed both strengths ().

Figure 7. Patient selection data flow from pharmacy dispensing software.

Negative dispensing could occur if a patient returned previously collected drug. Patients with dispensing <0 returned all dispensed packs within the study period.

The sum of patients who were dispensed 2.32% and 1.16% strength is greater than the total patients eligible for analysis because some patients had both strengths dispensed during the 12-month period.

Abbreviations. VGD, Voltaren gel diclofenac.

Patients were predominantly female (60.9%) with a mean age of 72.0 years (minimum to maximum: 18–118 years) for both strengths purchased. About two-thirds of patients (67.9%) were older adults (≥65 years old).

During the 12-month period of interest, 70.8% (n = 67,279) of patients received only one dispensing of VGD; it was dispensed twice to 15.4% patients, three times to 5.8% of patients and more than three times to 8.0% of patients. On average, 0.289 (95% CI, 0.288, 0.291) dispensings of VGD overall were collected by each patient per month. Among patients with at least two dispensings over the 12-month period, the mean interval between dispensings was 88 days (median 60 days) for those who purchased VGD in the first three months and 85 days (median 61 days) if the first dispensing was purchased during the first six months.

Most patients did not switch from VGD to another topical treatment in the 12-month period (77.3% of patients with one dispensing before month 4 and 78.0% of patients with one dispensing before month 7).

Over the 12-month period, 74.3% of patients dispensed VGD had also been dispensed treatments associated with CV disease and 35.4% for GI conditions. Of those, 30.9% received CV and GI medications. Less than 1% of the patients using VGD also had a dispensing of an oral NSAID within seven days of VGD purchase.

Discussion

This study took a unique approach, investigating both retrospective dispensing patterns of topical VGD OTC over a 12-month period and prospective survey results of the impact of VGD on patients’ pain, HRQoL, and satisfaction with treatment in a real-world setting. This dual approach allowed a deep understanding of the patient experience as well as provided evidence of usage patterns of the medicinal product and patient profiles in the real world. Current international guidelines for osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal pain recommend topical NSAIDs as first-line treatment prior to oral NSAIDsCitation27,Citation28, depending on location of osteoarthritis and severity of musculoskeletal painCitation14,Citation29–32. This recommendation is due to several advantages of topical application: the medication is applied directly to the site of pain, it avoids first-pass effect, minimizes systemic exposure which reduces the risk of systemic side effects and potential drug-drug interactions, and it may allow for reduced dosage of oral analgesics if used in combination with the topical formulationCitation33. In Germany, VGD was predominately dispensed to older adults: in the retrospective component, the mean age of patients was 72.0 years; similarly, the mean age of participants who completed the prospective survey was 60.8 years. The skew towards older age in our study population is likely due to a higher prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in older populations and, potentially, the fact that older adults more frequently have co-medications. Results of this study also suggest that patients with underlying CV and GI conditions may use VGD. Dispensing records showed that 74.3% of patients dispensed VGD had also been dispensed treatments associated with CV disease and 35.4% for GI conditions with similar findings from the participant survey. This may suggest that those with contraindications for oral NSAIDs could potentially use topical NSAIDs as an alternative to treat their musculoskeletal pain.

Topical NSAIDs such as VGD are considered to be well-tolerated and effective for the treatment of pain relief. In fact, some studies have shown that VGD may be more effective in treating symptomatic musculoskeletal pain than other topical NSAIDsCitation14,Citation34. Participants’ mean worst pain score of 6.0 ± 1.9 on the NRS decreased with VGD treatment with an overall change of −1.2 from baseline to Week 12. The literature supports that a change in NRS score of at least one point represents the minimal clinically important change for musculoskeletal painCitation35,Citation36. Our findings from the participant survey indicate that VGD provides clinically important change in NRS score, as well as increasing ability to participate in activities of daily life.

Adequate pain relief enables the patient to be physically active, thereby supporting the healing process. Therefore, a multimodal therapy approach that involves patients staying active as much as possible for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain is recommendedCitation37–40. In addition, studies have shown that inadequate pain management can lead to bad or protective posture, which can lead to new or worsening musculoskeletal issuesCitation41,Citation42. For these reasons, it is important that patients are able to manage their pain quickly and effectively. The prospective survey enabled a deeper understanding of the impact that VGD had on participants. In particular, an improved HRQoL was observed with an improvement in functional activities from baseline following use of VGD, e.g. in daily activities (90.0% at Week 4 compared to baseline; 91.9% at Week 12). Participants also reported being satisfied with the pain relief resulting from their treatment with VGD. At Week 4 (76.2%) and Week 12 (77.2%) more than three-quarters of participants were somewhat or extremely satisfied with the result of their treatment.

Additionally, our results indicate that VGD is well accepted by participants for the treatment of pain, illustrated not only by the high treatment satisfaction ratings in the prospective survey, but also by the fact that most patients did not switch treatments in the retrospective analyses. During the 12-month period, more than three-quarters of patients with one dispensing of VGD did not switch treatments. Additionally, 77.5% of all participants and 87.2% of participants aged 65 years and older chose to repurchase VGD OTC, indicating that participants trust VGD to be an effective treatment option to alleviate their pain.

Although the participant survey did not explore VGD usage patterns, participants were asked about reasons for their satisfaction with VGD, which may provide alternative reasons for choosing VGD to treat pain. The results of the survey showed that the most common reason for participants’ satisfaction with treatment had to do with the ability to maintain social independence (92.3% at Week 4 and 92.5% at Week 12). Our results confirm that increasing independence is important to VGD users and that participants in this survey were satisfied with treatment in that regard. Ease of use was a common reason for participant satisfaction with VGD. At Week 4 and Week 12, 81.6% and 77.6% of participants who were at least somewhat satisfied reported ease of a use as a reason for their satisfaction with VGD. These findings are supported by a previous study that explored patient and physician perceptions of factors that may influence greater satisfaction with topical NSAIDs which showed that patients prioritize both efficacy and comfort or ease of useCitation43.

Topical NSAID application may be of particular benefit to elderly adults who are at greater risk for musculoskeletal and joint pain due to aging and disability, and side effects due to oral NSAID use, and who frequently have CV and GI comorbidities and co-medication. Use of topical NSAIDs reduces the risk for drug interaction with other medications that elderly patients may require. VGD’s OTC status also provides benefit to elderly patients by eliminating the need to visit a physician’s office in a population who may see many doctors or specialists already. OTC status can also provide benefit to working-age adults whose pain may affect their ability to work or tend to their family. The ability to purchase VGD OTC allows patients to directly treat musculoskeletal pain and its associated functional impairment without the need schedule a doctor’s visit and wait for a prescription. Treating pain quickly is important, especially in the elderly patient population, to prevent bad posture and support movement, which is beneficial to the healing process and improves HRQoL. The safety profile, OTC status, and overall efficacy in treating pain makes VGD an important treatment option for musculoskeletal pain and can potentially contribute to limiting pressure on the healthcare system.

Although participants reported improvement in functional impairment through the survey, additional studies may be beneficial to further evaluate this reported improvement. Nevertheless, this real-world evidence study shows the impact that VGD has on well-being and HRQoL and how it helps patients to regain control over their pain. With its OTC status in Germany, the results of this study show that VGD is valuable treatment option especially in vulnerable populations such as older patient population.

Limitations/advantages

Due to the nature of the study’s design and objectives, a control group was not utilized and, therefore, we were not able to make comparisons related to effectiveness VGD in treating musculoskeletal pain. Retrospective data analysis was limited by the data available in the pharmacy dispensing records (e.g. strength [1.16% or 2.32%], number of dispensings, participant health, and comorbidities).

As with any self-reported real-world survey, responses relied on participants’ ability to recall information. It is possible that participants who were dissatisfied with VGD treatment withdrew from the study prior to Week 4 or Week 12, which may have inflated the treatment satisfaction scores. The majority of participants were also repeat users of VGD which may have influenced treatment satisfaction if participants based their degree of satisfaction on their past experiences with VGD or conflated their past experiences with their current experience. Responses from participants were not validated by a healthcare provider, nor was their use of VGD. It is possible that some musculoskeletal pain associated with self-resolving conditions may improve with the passage of time which would contribute to the improvements seen in the Week 4 and Week 12 surveys. Additionally, an analysis of patients who purchased VGD at a physical pharmacy (wave 1) versus an online pharmacy (wave 2) was not undertaken to determine any differences in characteristics between the two participant groups.

Lastly, survey data collection was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic. Risk of COVID-19 infection and mandated lockdowns limited people from leaving their homes to go to the pharmacy. This led to slow recruitment and the decision to switch to an online recruitment model. In addition, the possibility to carry out functional activities was impaired due to COVID-19 safety restrictions. However, our results still demonstrated that VGD improved patients’ ability to perform functional activities.

Online point-of-purchase and recruitment may have also limited the pool of participants reached and may not be representative of the entire population in Germany. Those without access to the internet or lacking digital literacy would not have been able to participate in the study. That said, demographics of survey participants were similar to that of German VGD users overall and the mean age of the survey study population (60.8 years) indicates that older adults were able to successfully participate in the study.

While there were limitations, this study also had multiple strengths. The real-world setting in which the study was carried out allows for a deeper understanding of the participants who purchased VGD OTC for musculoskeletal pain and their experience. The combination of the prospective and retrospective components provided an overall picture of VGD use. These findings highlight the perspective of the participant while managing pain in order to achieve better HRQoL and independence.

Conclusions

Improvement in HRQoL and the ability to get back to daily activities are important pain treatment outcomes. This real-world evidence study showed that patients treating their pain with VGD see benefits of use and have less pain interference in their daily lives. Retrospective analysis results from this study indicate that VGD is a treatment option for pain that is often used alongside other medications for CV and/or GI issues, indicating that patients experience benefits due to the well-established efficacy and safety profile of VGD. VGD is also predominately dispensed to older adults in Germany, with most dispensing records belonging to patients who were ≥65 years. Prospective analysis results of the participant survey demonstrated that VGD is accepted by participants for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain indicated by high rates of satisfaction, high rate of repurchase, and improvement in the ability to perform activities in their daily life. Similarly, the retrospective analysis showed that a low percentage of patients switched to other medications, suggesting strong patient satisfaction with VGD. This study demonstrated through a prospective and retrospective approach that patients benefit from the use of VGD for the treatment of pain, improving HRQoL and increasing the ability of patients to stay active.

Transparency

Author contributions

CM, KF, VS, GS, and EC contributed to the conception and design of the study and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. AdH contributed to the interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted. TKW contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following Haleon contributors: Anela Lihic Haveric and Denise Pohlhaus for contributing to study design, Roberto Bazzanella and Simon Arnold for helping in to define the research area, Daniela Deutsch for contributing to the interpretation of data, Vishal Rampartaap as project lead, and Farzana Sufi for editorial inputs; Laura Sayegh and Mary Kay Margolis (PPD, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific) for medical writing, editorial assistance, and their contributions to the design, analysis, and interpretation of the data; Chester Wong, Adrian Jackson and Maria Olimpia Perulan-Escanilla (Clarivate Plc, formerly Patient Connect Limited) for performing data analysis of the secondary database, consumer enrollment and their contributions for hosting the consumer survey; Erica Zaiser (Evidera, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific) for cognitive interviews.

Declaration of funding

The study and medical writing were funded by Haleon (formerly GSK Consumer Healthcare).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Christian Maihöfner has received honorarium payments for advising on study methodology. Anke de Haas, Vidhu Sethi, Gilbert Shanga and Kate Fabrikant are employees of Haleon (formerly GSK Consumer Healthcare). Teresa Wilcox was an employ of PPD, Part for Thermo Fisher Scientific, during the conduct of the study. Emese Csoke was an employee of GSK Consumer Healthcare during conduct of the study. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

- Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, et al. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the global burden of disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The. Lancet. 2021;396(10267):2006–2017. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32340-0.

- Fuchs J, Rabenberg M, Scheidt-Nave C. Prävalenz ausgewählter muskuloskelettaler Erkrankungen. 2013.

- Schmidt CO, Raspe H, Pfingsten M, et al. Back pain in the German adult population: prevalence, severity, and sociodemographic correlates in a multiregional survey. Spine. 2007;32(18):2005–2011. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318133fad8.

- Überall MA. Praxisleitfaden zu akuten Kreuz-und Rückenschmerzen. MMW – Fortschritte der Medizin. 2022;164:12–17.

- Schnitzer TJ. Update on guidelines for the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25(Suppl 1):S22–S29. doi:10.1007/s10067-006-0203-8.

- Pergolizzi J, Böger RH, Budd K, et al. Opioids and the management of chronic severe pain in the elderly: consensus statement of an international expert panel with focus on the six clinically most often used world health organization step III opioids (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone). Pain Pract. 2008;8(4):287–313. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2008.00204.x.

- Buchman AS, Shah RC, Leurgans SE, et al. Musculoskeletal pain and incident disability in community‐dwelling older adults. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(9):1287–1293. doi:10.1002/acr.20200.

- da Silveira MM, Potulski AP, Vidmar MF, et al. Atividade Física e Qualidade de Vida em Idosos. Saúde e Pesquisa. 2011;4(3):417.

- Hagen M, Madhavan T, Bell J. Combined analysis of 3 cross-sectional surveys of pain in 14 countries in Europe, the Americas, Australia, and Asia: impact on physical and emotional aspects and quality of life. Scand J Pain. 2020;20(3):575–589. doi:10.1515/sjpain-2020-0003.

- Mason L, Moore RA, Edwards JE, et al. Topical NSAIDs for acute pain: a meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2004;5:10. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-5-10.

- Mason L, Moore RA, Edwards JE, et al. Topical NSAIDs for chronic musculoskeletal pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5:28. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-5-28.

- Hagen M, Baker M. Skin penetration and tissue permeation after topical administration of diclofenac. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(9):1623–1634. doi:10.1080/03007995.2017.1352497.

- Schmidt M, Sørensen HT, Pedersen L. Diclofenac use and cardiovascular risks: series of nationwide cohort studies. BMJ. 2018;362:k3426. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3426.

- Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H, et al. Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(6):CD007402.

- McPherson ML, Cimino NM. Topical NSAID formulations. Pain Med. 2013;14(Suppl 1):S35–S39. doi:10.1111/pme.12288.

- Niethard FU, Gold MS, Solomon GS, et al. Efficacy of topical diclofenac diethylamine gel in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(12):2384–2392.

- Predel HG, Giannetti B, Pabst H, et al. Efficacy and safety of diclofenac diethylamine 1.16% gel in acute neck pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:250. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-14-250.

- Zacher J, Burger KJ, Färber L, et al. Topical diclofenac versus oral ibuprofen: a double blind, randomized clinical trial to demonstrate efficacy and tolerability in patients with activated osteoarthritis of the finger joints (Heberden and/or Bouchard Arthritis). Akt Rheumatol. 2001;26(1):7–14. doi:10.1055/s-2001-11369.

- Predel HG, Hamelsky S, Gold M, et al. Efficacy and safety of diclofenac diethylamine 2.32% gel in acute ankle sprain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012; Sep44(9):1629–1636. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318257ed41.

- Yin F, Ma J, Xiao H, et al. Randomized, double-blind, noninferiority study of diclofenac diethylamine 2.32% gel applied twice daily versus diclofenac diethylamine 1.16% gel applied four times daily in patients with acute ankle sprain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1125. doi:10.1186/s12891-022-06077-z.

- Poquet N, Lin C. The brief pain inventory (BPI). J Physiother. 2016;62(1):52. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2015.07.001.

- Tait RC, Pollard CA, Margolis RB, et al. The pain disability index: psychometric and validity data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987;68(7):438–441.

- Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, et al. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain. 1999;83(2):157–162. doi:10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00101-3.

- Kapstad H, Hanestad BR, Langeland N, et al. Cutpoints for mild, moderate and severe pain in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee ready for joint replacement surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:55. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-9-55.

- Li KK, Harris K, Hadi S, et al. What should be the optimal cut points for mild, moderate, and severe pain? J Palliat Med. 2007;10(6):1338–1346. doi:10.1089/jpm.2007.0087.

- Boonstra AM, Stewart RE, Koke AJ, et al. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the numeric rating scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: variability and influence of sex and catastrophizing. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1466. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01466.

- Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: a clinical guideline from the American college of physicians and American academy of family physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):739–748. doi:10.7326/M19-3602.

- Rafanan BS, Jr., Valdecanas BF, Lim BP, et al. Consensus recommendations for managing osteoarthritic pain with topical NSAIDs in Asia-pacific. Pain Manag. 2018;8(2):115–128. doi:10.2217/pmt-2017-0047.

- Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(11):1578–1589. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011.

- Bruyere O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, et al. A consensus statement on the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis-From evidence-based medicine to the real-life setting. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(4 Suppl):S3–S11. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.11.010.

- Kloppenburg M, Kroon FP, Blanco FJ, et al. 2018 Update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(1):16–24. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826.

- Rillo O, Riera H, Acosta C, et al. PANLAR consensus recommendations for the management in osteoarthritis of hand, hip, and knee. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22(7):345–354. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000449.

- McMahon SB, Dargan P, Lanas A, et al. The burden of musculoskeletal pain and the role of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in its treatment. Ten underpinning statements from a global pain faculty. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(2):287–292. doi:10.1080/03007995.2020.1847718.

- Sethi V, Van der Laan L, Gupta S, et al. Perspectives of healthcare professionals towards combination use of oral paracetamol and topical non-steroidal inflammatory drugs in managing mild-to-moderate pain for osteoarthritis in a clinical setting: an exploratory study. J Pain Res. 2022;15:2263–2272. doi:10.2147/JPR.S373382.

- Kendrick DB, Strout TD. The minimum clinically significant difference in patient-assigned numeric scores for pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23(7):828–832. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2005.07.009.

- Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, et al. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(4):283–291. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.004.

- Hsu JR, Mir H, Wally MK, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for pain management in acute musculoskeletal injury. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33(5):e158–e182. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000001430.

- Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 2017;389(10070):736–747. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30970-9.

- McSwan J, Gudin J, Song XJ, et al. Self-healing: a concept for musculoskeletal body pain management – scientific evidence and mode of action. J Pain Res. 2021;14:2943–2958. doi:10.2147/JPR.S321037.

- Chenot J-F, Greitemann B, Kladny B, et al. Non-specific low back pain. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. 2017;114(51–52):883.

- Swann J. Good positioning: the importance of posture. Nurs Res Care. 2009;11(9):467–469. doi:10.12968/nrec.2009.11.9.43734.

- Überall MA. Behandlung von akuten Kreuz-und Rückenschmerzen. Schmerzmedizin. 2021;37:51–54.

- Takeda O, Chiba D, Ishibashi Y, et al. Patient-physician differences in desired characteristics of NSAID plasters: an online survey. Pain Res Manag. 2017;2017:5787854. doi:10.1155/2017/5787854.