Abstract

Objective

Zanubrutinib is a highly selective, next-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor. In the phase 3 SEQUOIA trial (NCT03336333), treatment with zanubrutinib resulted in significantly improved progression-free survival compared to bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) in adult patients with treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) without del(17p). The current analysis compared the effects of zanubrutinib versus BR on patients’ health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL).

Methods

In the SEQUOIA trial, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were assessed at baseline and every 12 weeks (3 cycles) using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EQ-5D-5L. Descriptive analyses were performed on all the questionnaires’ scales and a mixed model for repeated measures was performed using the key QLQ-C30 endpoints of global health status/QoL (GHS/QoL), physical and role functioning, and symptoms of fatigue, pain, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting at weeks 12 and 24.

Results

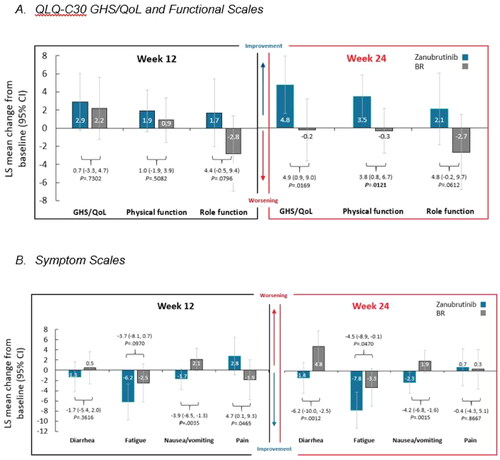

Compared with BR-treated patients, those in the zanubrutinib arm experienced greater improvements in HRQoL outcomes at both weeks 12 and 24. By week 24, mean change differences (95% confidence interval) between the arms were significant for GHS/QoL (4.9 [0.9, 9.0]), physical functioning (3.8 [0.8, 6.7]), diarrhea (−6.2 [−10.0, −2.5]), fatigue (−4.5 [−8.9, −0.1]), and nausea/vomiting (−4.5 [−8.9, −0.1]); role functioning (4.8 [−0.2, 9.7]) was marginally better in the zanubrutinib arm and there were no differences in pain symptoms (−0.4 [−4.3, 5.1]) between the arms.

Conclusions

During the first 24 weeks of treatment, zanubrutinib was associated with better HRQoL outcomes in patients with treatment-naive CLL/SLL without del(17p) compared to BR.

Trial registration

The SEQUOIA trial is registered on clinicaltrials.gov as SEQUOIA trial (NCT03336333).

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) are different manifestations of the same disease and are the most common type of leukemia in adults in the Western worldCitation1–3. Compared with the general population, patients with CLL/SLL have substantially worse health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL)Citation4. The negative impact on HRQoL may be due to the disease itself, the side-effects related to treatment (e.g. nausea, diarrhea), or bothCitation4–8.

Until recently, initial treatment for CLL has been chemoimmunotherapy; however, advances in development of new Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors have transformed the therapeutic landscape for CLL/SLLCitation2,Citation9–12. Zanubrutinib is a highly selective next-generation BTK inhibitor which was designed to have fewer off-target effects associated with earlier generation BTK inhibitorsCitation13–15. SEQUOIA (BGB-3111-304; NCT03336333), a global, open-label, randomized, phase 3 clinical trial, compared zanubrutinib versus bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) combination chemoimmunotherapy in adult patients with treatment-naive CLL/SLL. After a median follow-up of 26.2 months for this interim analysis, CLL/SLL patients without del(17p) demonstrated significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) with zanubrutinib versus BR (hazard ratio = 0.42 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.28–0.63]; 2-sided p <.0001)Citation16.

The current analysis focused on HRQoL using patient-reported outcome (PRO) assessments from the prespecified interim analysis of SEQUOIA in a cohort of patients with treatment-naive CLL without del(17p). The objective was to compare the effects of receiving zanubrutinib versus BR on the patients’ HRQoL.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

In the SEQUOIA study (NCT03336333), treatment-naive patients without del(17p) (cohort 1) were randomized 1:1 to receive either zanubrutinib or BR using a centralized interactive web response systemCitation16. Randomization was stratified by age (<65 years versus ≥65 years), Binet stage (C versus A or B), immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region mutational status (mutated versus unmutated), and geographic region (North America versus Europe versus Asia-Pacific). Treatment with BR was considered a standard of care in patients with untreated CLL/SLL in the participating countries and was deemed acceptable as a comparator by regulatory authorities.

Zanubrutinib was administered orally as 160 mg twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity; bendamustine was administered intravenously as 90 mg/m2/day on the first 2 days of cycles 1 through 6 (each cycle lasted 28 days) and rituximab was administered intravenously as 375 mg/m2 on the day before or day of the start of cycle 1, then 500 mg/m2 on the first day of cycles 2–6. Eligible patients had CLL/SLL that required treatment and were unsuitable for treatment with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab. Premedication to reduce and manage symptoms in accordance with institutional standards before administering bendamustine was permitted per protocol. In accordance with Good Clinical PracticeCitation17, the protocol and amendments were reviewed and approved by the study sites’ institutional review boards/independent ethics committees. Written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to any participation in the study.

PRO endpoints

HRQoL was assessed via the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core 30 (QLQ-C30)Citation18 and the EuroQoL 5-dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaireCitation19, both of which are validated and widely used PRO instruments to assess HRQoL in patients with cancerCitation18. The QLQ-C30 and EQ-5D-5L were administered at baseline and then every 12 weeks (3 cycles) until disease progression, death, or withdrawal of consent, regardless of study treatment discontinuation. Patients completed the questionnaires before any other procedure.

The QLQ-C30 is used to assess the overall HRQoL of cancer patients during the past week and includes a global health status/quality-of-life (GHS/QoL) index scale, five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning), and nine symptom scales (fatigue, pain, nausea/vomiting, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial impact)Citation18,Citation20. The GHS/QoL scale items are rated using a numeric rating scale from 1–7 (anchored at very poor and excellent), whereas the remaining items are rated using a verbal-descriptive scale from 1–4 (not at all, a little, quite a bit, and very much). Higher scores on the GHS/QoL and functioning scales indicate better HRQoL, whereas higher scores on the symptom scales suggest worsening HRQoL. Key PRO endpoints were prespecified based on the most relevant disease- and treatment-related scales of the QLQ-C30 for patients with CLL/SLLCitation3–5,Citation21. They included GHS/QoL, physical and role functioning, as well as the symptom scales for diarrhea, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and painCitation5–7. Additionally, the EQ-5D-5L’s visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS), which asks patients to rate their general health prior to administration of the questionnaire, on a scale from 0 (the worst health you can imagine) to 100 (the best health you can imagine), was used to descriptively assess general health status.

Statistical analysis

All randomized patients in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population who received at least one dose of study drug and completed the baseline and at least one post-baseline PRO questionnaire were included in this analysis. Completion rates were defined as the ratio of patients who completed the questionnaires at each treatment cycle to patients randomized that were still on treatment. PRO endpoints were evaluated at Weeks 12 and 24 in order to assess the impact of HRQoL during active treatment cycles.

Raw scores were calculated as the average of the item(s) that contribute to each scale; a linear transformation to standardize the raw scores was then utilized so that the scores for each scale ranged from 0–100. Descriptive analyses using means and standard deviations (SD) were performed on all the PRO scales of QLQ-C30 and the EQ-VAS. To assess differences within and between the arms from baseline to the key clinical cycles, a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) was used with the key PRO endpoint’s score as the response variable. Covariates included treatment, study visit, treatment by study visit interaction, and three randomization stratification factors (age [<65 years versus ≥65 years], Binet stage [C versus A or B], and immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region mutational status [mutated versus unmutated]). Within- and between-group comparisons were reported as differences in the least-squares (LS) mean change from baseline with 95% CIs. Between-group p values were two-sided and nominal, without multiplicity adjustment. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4. Clinical meaningfulness was defined as ≥5% (i.e. 5-point) mean change from baselineCitation22–24.

Results

Demographics

As of the May 7, 2021 data cut-off, 479 patients were enrolled in cohort 1, with 241 patients randomized to zanubrutinib and 238 randomized to BR. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were generally balanced between the treatment groups (); full demographic information is available in Tam et al.Citation16 Antiemetics and antinauseants were administered as premedication/prophylaxis in 77.5% (n = 183) of patients in the BR arm during the treatment phase.

Table 1. Demographics and baseline disease characteristics.

Completion rates

Across all patients in the ITT population, completion rates for both PRO questionnaires were greater than 74% at weeks 12 and 24 (). Completion rates for both PRO questionnaires at weeks 12 and 24 were higher in the zanubrutinib arm relative to the BR arm, with completion rates exceeding 83% and 74%, respectively, post-baseline.

Table 2. Completion rates.

Change from baseline at weeks 12 and 24

Baseline scores of the QLQ-C30 scales and EQ-VAS were similar across the two treatment arms (Supplementary Table S1). Overall, the PRO endpoints’ scores in the zanubrutinib arm showed more improvement from baseline to both weeks 12 and 24 in comparison with the BR arm (). Of note, pain symptom scores improved more from baseline to week 12 for BR patients as compared to zanubrutinib and were maintained in both arms by week 24.

Table 3. Mean change in the QLQ-C30 scales from baseline to weeks 12 and 24.

MMRM analysis

Results of the MMRM analysis examining the within- and between-group changes from baseline to the clinical cycles associated with weeks 12 and 24 in the key PRO endpoints are reported in ; data from all the QLQ-30 scales are presented in Supplementary Table S2. The LS mean change from baseline in GHS/QoL and physical functioning were similar in patients who received zanubrutinib and BR at week 12; however, by week 24, in patients receiving zanubrutinib, significant differences in improvement for GHS/QoL and physical functioning were observed compared with patients receiving BR (). Role functioning scores worsened for patients treated with BR compared to improvements in the zanubrutinib arm at both weeks 12 and 24; the differences between treatments approached significance at both cycles.

Figure 1. Least-squares mean change from baseline in key PRO endpoints at weeks 12 and 24.

Abbreviations: BR, bendamustine plus rituximab; CI, confidence interval; GHS, global health status; LS, least-squares; PRO, patient-reported outcome; QLQ-C30, Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core 30; QoL, quality-of-life.

Higher scores on the GHS/QoL index and functional scales and lower scores in the symptom scales indicate better health-related quality-of-life. Analysis is based on a linear mixed model for repeated measures; the dependent variable of this model is the QLQ-C30 scale score at different visits (baseline, week 12, and week 24). The model includes treatment (pre-treatment/baseline versus BR versus zanubrutinib), time (as a categorical variable), treatment by time interaction, as well as the three randomization stratification factors as fixed effects; and patient as the random intercept. All p values are nominal and for descriptive purposes.

While diarrhea scores were generally unchanged in patients receiving zanubrutinib from baseline to weeks 12 and 24, these scores worsened over time in patients receiving BR (). By week 24, the difference in diarrhea scores between treatment arms was statistically significant, with the scores remaining unchanged in patients receiving zanubrutinib and worsening in the patients receiving BR. Clinically meaningful reduction from baseline was also observed in the zanubrutinib arm for fatigue symptoms. Even though fatigue decreased in both arms, the differences between the arms widened over time, with the zanubrutinib arm having significantly more improvement in fatigue at week 24. At weeks 12 and 24, patients in the zanubrutinib arm reported decreased nausea/vomiting and patients in the BR arm reported increased nausea/vomiting; the differences between the arms were significant at both weeks 12 and 24. Finally, although patients who received BR initially experienced significantly lower pain scores at week 12 compared with patients who received zanubrutinib; by week 24, pain scores were similar, with no significant differences between the arms.

EQ-VAS

The zanubrutinib and BR arms experienced similar improvements in general health status according to the VAS score of the EQ-5D-5L (mean [SD] of 78.6 [15.9] for zanubrutinib and 74.5 [17.6] for BR at week 12 and 79.5 [16.6] for zanubrutinib and 76.3 [16.9] for BR at week 24). At both follow-up visits, the zanubrutinib arm had numerically better scores compared to the BR arm, although the magnitude of change was not an indication of a meaningful difference between the two arms.

Discussion

Analysis of PRO data in patients with treatment-naive CLL/SLL without del(17p) mutation from the randomized SEQUOIA trial found that those who were treated with zanubrutinib reported better HRQoL than patients who were treated with BR. The ability of zanubrutinib to improve or maintain patients’ HRQoL was initially observed at week 12 on all key endpoints from the EORTC QLQ-C30, with the exception of pain; these improvements continued through week 24. By cycle 6 (week 24), significant improvements relative to the BR arm were seen in overall health status and physical functioning, as well as diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, and fatigue symptom scores. Additionally, patients in the zanubrutinib treatment arm reported marginally better role functioning compared to BR at week 24; there were no significant differences in pain symptom scores. Of note, scores on the EQ-5D-5L VAS did not show any differences between the arms at either follow-up visit. Patients in both treatment arms reported similar improvements when rating their general health using the EQ-5D-5L; this generic instrument with a single-day recall period might not be sensitive enough to detect any differences between treatments.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 assesses the overall HRQoL of cancer patients during the week prior to administration of the questionnaire, and is among the most frequently used HRQoL instruments in clinical trials of patients with CLLCitation25. The EORTC originally developed a 16-item CLL-specific questionnaire that is no longer recommended by the developer; instead, a revised 17-item version is now available (QLQ-CLL17)Citation26. The QLQ-CLL17 includes scales assessing symptom burden due to disease and/or treatment, physical condition/fatigue, and worries/fears about health and functioning. Instruments that are applicable to a broad range of cancer patients such as the QLQ-C30 have the advantage of being broadly comparable across studies, yet they may not adequately capture specific aspects of HRQoL – including functional limitations and symptoms – that are more important for patients with CLL/SLL.

Unfortunately, there are limited comparable PRO data available from other clinical trials focused on the impact of BTK inhibitors in patients with CLL, and no prior study has provided a head-to head comparison of a BTK inhibitor to BRCitation11,Citation12,Citation27,Citation28. Previous trials comparing ibrutinib plus BR versus placebo and BR found no differences between treatment arms in HRQoLCitation12,Citation28. The improvements in HRQoL reported in this study follow a similar pattern observed in the clinical outcomes of SEQUOIA where prolonged PFS and lower incidence of grade 3 or worse adverse events (AEs) at a median follow-up of 26 months was reported in patients who were treated with zanubrutinib versus BRCitation16.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include the possibility that treatment-emergent AEs, especially nausea and diarrhea, may have impacted patient reports of functioning and symptoms. Future analysis that examines the direct associations between AEs and relevant PRO endpoints should be explored. The data presented here show the impact of zanubrutinib versus BR on HRQoL in the first 24 weeks following treatment initiation (i.e. the treatment phase). However, it is notable that zanubrutinib is a continuous oral therapy while BR is a time-limited chemoimmunotherapy regimen, and analysis of PRO impact beyond the 24-week treatment cycle duration of BR was not performed. Although such analysis is confounded by treatment regimen, further examination to compare longer-term follow-up on zanubrutinib versus the post-treatment phase of BR may be warranted as mature data.

Conclusions

PROs, assessed during the first 6 months of treatment in the phase 3 SEQUOIA trial, demonstrate that patients treated with zanubrutinib had significantly improved and clinically meaningful HRQoL compared with BR in patients with treatment-naive CLL/SLL without del(17p) mutation. These data highlight improvements of patients’ global health, physical functioning, and key symptoms of nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and fatigue in this patient population. Long-term follow-up and further analyses will help determine the full extent to which zanubrutinib improves patient HRQoL.

Transparency

Author contributions

Ghia, Tam, Tadeusz, Brown, Kahl, Robak, Shadman, and Barnes were responsible for the study design and data collection. Barnes, Yang, Tian, Szeto, and Paik were responsible for data interpretation and reviewing drafts of the manuscript. Barnes and Tian were responsible for data analysis. All authors contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript.

Ethics statement

This protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the participating sites. The study was performed according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the requirements of the public registration of clinical trials.

Written informed consent was obtained prior to participation in the study.

Spp Table 2 304.docx

Download MS Word (20 KB)Spp Table 1 304.docx

Download MS Word (15.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the investigative centers’ study staff and study patients and to recognize those from BeiGene, Ltd. who have substantially contributed to the development of this manuscript. Editorial assistance was provided by Jason C. Allaire, PhD (Generativity – Health Economics and Outcomes Research, Durham, NC). This assistance was funded by BeiGene, Ltd.

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by BeiGene, LTD.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Consultant/Advisor: Paolo Ghia: Advisory boards and consultancy fees from AbbVie, AstraZenenca, BMS, BeiGene, Janssen, Lilly/Loxo Oncology, MSD, Roche; Tadeusz Robak: BeiGene Participation in advisory board; Jennifer R. Brown: AbbVie, Acerta/AstraZeneca, Alloplex Biotherapeutics, BeiGene, Genentech/Roche, Grifols Worldwide Operations, iOnctura, Kite, Merck, Numab Therapeutics, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics; Brad S. Kahl: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Genentech, Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Seattle Genetics, Kite; Mazyar Shadman: AbbVie, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Pharmacyclics, BeiGene, BMS, MorphoSys/Incyte, Kite, Eli Lilly, Genmab, Mustang Bio, Regeneron, ADC therapeutics, Fate Therapeutics, Nurix and MEI Pharma.

Stock/Shareholder: Gisoo Barnes, Keri Yang, Tian Tian, Andy Szeto, and Jason C. Paik: BeiGene.

Other: Gisoo Barnes, Keri Yang, Tian Tian, Andy Szeto, and Jason C. Paik: Employees of BeiGene; Constantine S. Tam: Honorarium from AbbVie, Janssen, BeiGene, LOXO and Roche; Mazyar Shadman: Participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board for Fate Therapeutics and BeiGene. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Data availability statement

BeiGene voluntarily shares anonymous data on completed studies responsibly and provides qualified scientific and medical researchers access to anonymous data and supporting clinical trial documentation for clinical trials in dossiers for medicines and indications after submission and approval in the United States, China, and Europe. Clinical trials supporting subsequent local approvals, new indications, or combination products are eligible for sharing once corresponding regulatory approvals are achieved. BeiGene shares data only when permitted by applicable data privacy and security laws and regulations. In addition, data can only be shared when it is feasible to do so without compromising the privacy of study participants. Qualified researchers may submit data requests/research proposals for BeiGene review and consideration through BeiGene’s clinical trial webpage at https://www.beigene.com/our-science-and-medicines/our-clinical-trials/.

References

- Yao Y, Lin X, Li F, et al. The global burden and attributable risk factors of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Biomed Eng Online. 2022;21(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12938-021-00973-6.

- Eichhorst B, Robak T, Montserrat E, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.019.

- National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Stat Facts: chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. [cited 2023 Jun 25]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cllsll.html

- Waweru C, Kaur S, Sharma S, et al. Health-related quality of life and economic burden of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of novel targeted agents. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(9):1481–1495. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2020.1784120.

- American Cancer Society. Signs and symptoms of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. [cited 2023 Jun 25]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html

- Holtzer-Goor KM, Schaafsma MR, Joosten P, et al. Quality of life of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in The Netherlands: results of a longitudinal multicentre study. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(12):2895–2906. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1039-y.

- Lipsky A, Lamanna N. Managing toxicities of Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2020;2020(1):336–345. doi: 10.1182/hematology.2020000118.

- Shanafelt TD, Bowen D, Venkat C, et al. Quality of life in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an international survey of 1482 patients. Br J Haematol. 2007;139(2):255–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06791.x.

- Scheffold A, Stilgenbauer S. Revolution of chronic lymphocytic leukemia therapy: the chemo-free treatment paradigm. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22(2):16. doi: 10.1007/s11912-020-0881-4.

- Smolej L, Vodárek P, Écsiová D, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy in the first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: dead yet, or alive and kicking? Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(13):3134. doi: 10.3390/cancers13133134.

- Burger JA, Barr PM, Robak T, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with CLL/SLL: 5 years of follow-up from the phase 3 RESONATE-2 study. Leukemia. 2020;34(3):787–798. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0602-x.

- Cramer P, Fraser G, Santucci-Silva R, et al. Improvement of fatigue, physical functioning, and well-being among patients with severe impairment at baseline receiving ibrutinib in combination with bendamustine and rituximab for relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma in the HELIOS study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59(9):2075–2084. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2017.1416364.

- GlobeNewswire. BeiGene announces the approval of BRUKINSATM (zanubrutinib) in China for patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma and relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma; 2020 [cited 2023 Jun 25]. Available from: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/06/03/2042805/0/en/BeiGene-Announces-the-Approval-of-BRUKINSA-Zanubrutinib-in-Chinafor-Patients-with-Relapsed-Refractory-Chronic-Lymphocytic-Leukemia-or-Small-Lymphocytic-Lymphoma-and-Relapsed-Refra.html

- Guo Y, Liu Y, Hu N, et al. Discovery of zanubrutinib (BGB-3111), a novel, potent, and selective covalent inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. J Med Chem. 2019;62(17):7923–7940. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00687.

- Tam CS, Opat S, D'Sa S, et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of zanubrutinib vs ibrutinib in symptomatic Waldenström macroglobulinemia: the ASPEN study. Blood. 2020;136(18):2038–2050. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006844.

- Tam CS, Brown JR, Kahl BS, et al. Zanubrutinib versus bendamustine and rituximab in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SEQUOIA): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(8):1031–1043. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(22)00293-5.

- International conference on harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use (ICH) adopts consolidated guideline on good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. Int Dig Health Legis. 1997;48(2):231–234.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x.

- Kemmler G, Holzner B, Kopp M, et al. Comparison of two quality-of-life instruments for cancer patients: the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(9):2932–2940. doi: 10.1200/jco.1999.17.9.2932.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Plymouth Meeting (PA): National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2022.

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–144. doi: 10.1200/jco.1998.16.1.139.

- Shields A, Coon C, Hao Y, et al. Patient-reported outcomes for US oncology labeling: review and discussion of score interpretation and analysis methods. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(6):951–959. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2015.1115348.

- Sloan JA, Dueck AC, Erickson PA, et al. Analysis and interpretation of results based on patient-reported outcomes. Value Health. 2007;10(Suppl 2):S106–S115. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00273.x.

- Müller D, Fischer K, Kaiser P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of rituximab in addition to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (R-FC) for the first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(5):1130–1139. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1070151.

- van de Poll-Franse L, Oerlemans S, Bredart A, et al. International development of four EORTC disease-specific quality of life questionnaires for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, high- and low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(2):333–345. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1718-y.

- Hillmen P, Janssens A, Babu KG, et al. Health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes of ofatumumab plus chlorambucil versus chlorambucil monotherapy in the COMPLEMENT 1 trial of patients with previously untreated CLL. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(9-10):1115–1120. doi: 10.1080/0284186x.2016.1205217.

- Wang ML, Jurczak W, Jerkeman M, et al. Ibrutinib plus bendamustine and rituximab in untreated mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(26):2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201817.