Abstract

Objective

Post-hoc analysis examined health-related quality of life and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) symptoms in the Asian subgroup of patients in RATIONALE-302 (NCT03430843).

Methods

Patients were randomized 1:1 to either tislelizumab or investigator-chosen chemotherapy (paclitaxel, docetaxel, or irinotecan). Health-related quality of life was measured using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-OES18. Least-squares mean score changes from baseline to weeks 12 and 18 in health-related quality-of-life scores were assessed using a mixed model for repeated measurements. Reported nominal p-values are for descriptive purposes only.

Results

Of the 512 patients, this analysis was conducted in 392 Asian patients (tislelizumab, n = 192; investigator-chosen chemotherapy, n = 200). The tislelizumab arm had stable global health status/quality of life, but fatigue scores worsened in both arms. The change from baseline was similar for physical functioning in both arms at weeks 12 and 18. Eating and dysphagia scores remained stable in the tislelizumab arm. Reflux improved at week 12 in the tislelizumab arm and worsened in the investigator-chosen chemotherapy arm.

Conclusions

Overall, the health-related quality of life and ESCC-related symptoms of patients receiving tislelizumab in the Asian subgroup remained stable or improved, while patients receiving investigator-chosen chemotherapy experienced worsening. These results in Asian patients corroborate the findings in the intent-to-treat population, suggesting tislelizumab is a potential new second-line treatment option for patients with advanced or metastatic ESCC.

Trial registration

The RATIONALE-302 study is registered on clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03430843.

Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is the most common histological subtype of esophageal cancer worldwide, with 90% of all esophageal cancers globally classified as ESCCCitation1. Analysis of real-world cancer registries suggests that the highest incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is observed among White patients, while the incidence of ESCC is the highest in Asian adultsCitation2. In fact, the prevalence of esophageal cancer increased worldwide between 1990 and 2019, with the highest incidence reported in Eastern Asia (12.2 per 100,000 people)Citation3. Consequently, the Asian continent accounts for 78% of all esophageal cancer deathsCitation3.

Individuals with ESCC typically experience severe symptom burden and associated reduction in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at diagnosis, which worsens with advanced disease severityCitation4–7. Recent clinical trials of immuno-oncology therapies targeting the programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathways, collectively referred to as PD-(L)1, have reported maintenance (reduced risk of deterioration) as well as improvements in HRQoL and symptom burden in patients with esophageal cancer treated with a PD-(L)1 therapy versus chemotherapyCitation8–11.

Similar results were recently reported for RATIONALE-302 (NCT03430843), a global, open-label, randomized, phase 3 study investigating tislelizumab, a humanized immunoglobulin G4 variant monoclonal antibody against PD-1, compared with investigator-chosen chemotherapy (ICC) in patients with advanced or metastatic ESCC whose disease progressed after first-line systemic therapyCitation12. Analysis of the intent-to-treat (ITT) population of RATIONALE-302 found overall HRQoL, fatigue, and physical functioning were maintained in patients receiving tislelizumab, while they worsened in patients receiving ICCCitation13. Other clinical trials have also demonstrated that patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with tislelizumab experienced maintenance or improvement in HRQoL as well as reduced cancer-specific symptoms compared with patients receiving chemotherapyCitation14,Citation15.

Given the heavy disease burden of ESCC in the Asian population, the current post-hoc analysis examined whether tislelizumab improved HRQoL and reduced symptom burden compared with ICC in the Asian subgroup of patients in RATIONALE-302.

Materials and methods

Study design, population, and treatment

Eligible patients from RATIONALE-302 (NCT03430843) were randomized (1:1) to receive tislelizumab or ICC (one of the following single-agent chemotherapies: paclitaxel, docetaxel, or irinotecan). The study design and primary efficacy and safety data have been published elsewhere12. Tislelizumab was administered intravenously (IV) 200 mg every 3 weeks (Q3W). Paclitaxel was administered as 135–175 mg/m2 IV Q3W or in doses of 80–100 mg/m2 weekly according to regional guidelines. In Japan, paclitaxel was administered as 100 mg/m2 IV in cycles consisting of weekly dosing for 6 weeks, followed by 1 week of rest. Docetaxel was administered as 75 mg/m2 IV Q3W (70 mg/m2 IV Q3W in Japan). Irinotecan 125 mg/m2 IV was administered on days 1 and 8, every 21 days. Randomization was conducted by using permuted block stratified randomization with the following stratification factors: region (Asia [excluding Japan] vs Japan vs Europe/North America), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (0 vs 1), and ICC (paclitaxel vs docetaxel vs irinotecan).

Eligible patients were adults (≥18 years of age) with histologically confirmed ESCC who had advanced or metastatic disease that progressed during or after first-line systemic treatment. Patients who had tumor progression during or within 6 months after definitive chemoradiotherapy, neo-adjuvant therapy, or adjuvant therapy were also eligible. Patients were required to have an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1, at least one measurable/evaluable lesion by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors v1.1, and adequate hematological, hepatic, renal, and coagulation function. Patients who received prior therapies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1, active brain or leptomeningeal metastasis, active autoimmune disease, or other prior malignancies active within 2 years before randomization were ineligible. The study was carried out in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guideline, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and local laws and regulations. All patients provided written informed consent before participation.

HRQoL measures

HRQoL and ESCC symptoms were assessed via two validated patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments administered via the paper versions: the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality-of-Life Questionnaire Core 30 items (QLQ-C30)Citation16 and the EORTC Quality-of-Life Questionnaire Oesophageal Cancer Module 18 items (QLQ-OES18)Citation17. Specific PRO endpoints were selected from the QLQ-OES18 based on the most prevalent ESCC symptoms of dysphagia, eating, reflux, and pain (single items), as well as the full QLQ-OES18 symptom index score; the QLQ-C30 global health status/quality-of-life (GHS/QoL) scale, physical functioning scale, and fatigue symptom scale were also selected as they prominently measured the disease impact. The criteria for the selection of these specific endpoints were based on ESCC data from internal studies and previous publications of ESCC clinical trialsCitation9,Citation10,Citation18. The key clinical cycles, cycles 4 and 6, were selected to represent times around weeks 12 and 18 of study treatment to minimize data loss due to disease progression or death. Cycles 4 and 6, which represented the end of ICC for most patients, were selected to measure the long-term effects of treatment.

For the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OES18 assessments at each visit, the raw scores for functional and symptom scales and items were transformed from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better outcomes on the GHS/QoL scale and physical functioning scale and worse outcomes on the symptom scalesCitation19.

Statistical analyses

The PRO analyses included all randomized patients who completed baseline, received at least one dose of study drug, and completed at least one HRQoL assessment at a future cycle. Completion rates were defined as the number of patients who completed all the questionnaires divided by the total number of patients in the relevant treatment arm. Adjusted completion rates were defined as the proportion of patients that completed all the questions in a questionnaire divided by the total number of patients in the study at the relevant visit in the relevant treatment arm.

Evaluation of least square (LS) mean change from baseline to weeks 12 and 18 in the PRO instrument scores was based on a mixed effect model for repeated measurements, with the PRO score as the response variable. The covariates included treatment, study visit, treatment by study visit interaction, baseline score, and randomization stratification factors (ECOG performance status [0 vs 1] and ICC option [paclitaxel vs docetaxel vs irinotecan]). The models were based on the missing at random assumption. Between-group comparisons were reported as differences in the LS mean change from baseline with the 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

The Asian subgroup was comprised of 404 patients (tislelizumab, n = 201; ICC, n = 203) from a total of 512 patients in the RATIONALE-302 ITT population. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the Asian subgroup are presented in and were similar to those reported in the ITT population. The data cutoff date for the current analysis was December 1, 2020.

Table 1. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics in the ITT population and Asian subgroup.

Adjusted completion rates

For the QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-OES18, the completion rates and adjusted completion rates for the Asian subgroup were comparable to those of the ITT population. In the Asian subgroup at baseline, the completion rates were 95.5% or greater, as were the adjusted completion rates (Supplementary Table S1). At weeks 12 and 18, the completion rates and the adjusted completion rates remained high (96.4% or higher).

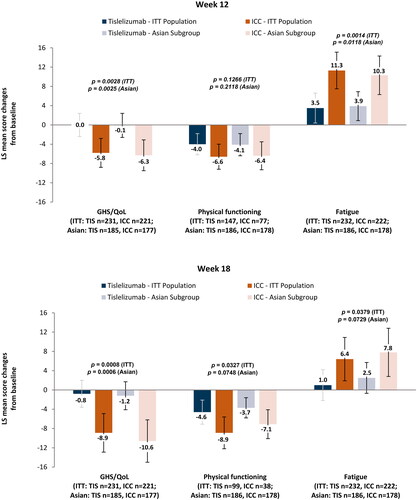

EORTC QLQ-C30

Results from the mixed effect model for repeated measurements indicated that the tislelizumab-treated patients maintained QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL scale scores () at both week 12 (LS mean change = −0.1 [95% CI = −2.5 to 2.4]) and week 18 (LS mean change = −1.2 [95% CI = −4.0 to 1.7]), while the ICC arm experienced worsening at both week 12 (LS mean change = −6.3 [95% CI = −9.4 to −3.1]) and week 18 (LS mean change = −10.6 [95% CI = −15.1 to −6.2]). There was a difference in change from baseline between the two arms (tislelizumab vs ICC) at week 12 (difference in LS mean change = 6.2 [95% CI = 2.2 to 10.2], p = .0025) and week 18 (difference in LS mean change = 9.4 [95% CI = 4.1 to 14.7], p = .0006).

Figure 1. Change from baseline for EORTC QLQ-C30 at weeks 12 and 18.

Abbreviations: EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; GHS/QoL, global health status/quality of life; ICC, investigator-chosen chemotherapy; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least square; n, patents with baseline and at least one post-baseline measurement; QLQ-C30, Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30.

There were no differences in the change in physical functioning from baseline between the two arms at week 12 (difference in LS mean change = 2.3 [95% CI = −1.3 to 6.0], p =.2118) or at week 18 (difference in LS mean change = 3.4 [95% CI = −0.3 to 7.1], p =.0748). However, the worsening of physical functioning from baseline was less noticeable in the tislelizumab arm at both time points (week 12: LS mean change = −4.1 [95% CI = −6.4 to −1.8]; week 18: LS mean change = −3.7 [95% CI = −5.9 to −1.6]) compared with the ICC arm (week 12: LS mean change = −6.4 [95% CI = −9.3 to −3.5]; week 18: LS mean change = −7.1 [95% CI = −10.1 to −4.1]).

Finally, fatigue symptoms worsened less at week 12 in the tislelizumab arm (LS mean change = 3.9 [95% CI = 0.8–6.9]) relative to the ICC arm (LS mean change = 10.3 [95% CI = 6.3–14.3]). At week 18, fatigue in the tislelizumab arm worsened less (LS mean change = 2.5 [95% CI = −0.7 to 5.7]) than in the ICC arm (LS mean change = 7.8 [95% CI = 2.9–12.8]). The worsening of fatigue was less marked in the tislelizumab arm than in the ICC arm at week 12 (difference in LS mean change = −6.4 [95% CI = −11.5 to −1.4], p =.0118) and week 18 (difference in LS mean change = −5.4 [95% CI = −11.2 to 0.5], p =.0729).

EORTC QLQ-OES18

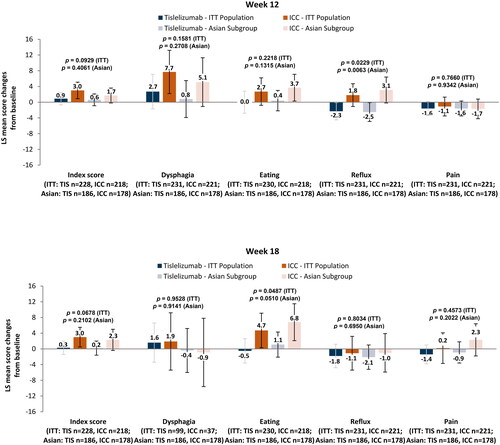

Results from the mixed effect model for repeated measurements indicated that the QLQ-OES18 symptom index scale scores () in the tislelizumab arm were maintained at both week 12 (LS mean change = 0.6 [95% CI = −0.9 to 2.1]) and week 18 (LS mean change = 0.2 [95% CI = −1.6 to 2.0]), while the ICC arm experienced maintenance at week 12 (LS mean change = 1.7 [95% CI = −0.3 to 3.6]) and worsening at week 18 (LS mean change = 2.3 [95% CI = −0.4 to 5.0]). However, there was no difference in change from baseline between the two arms at either week 12 (difference in LS mean change = −1.0 [95% CI = −3.5 to 1.4], p =.4061) or week 18 (difference in LS mean change = −2.1 [95% CI = −5.3 to 1.2], p =.2102).

Figure 2. Change from baseline for QLQ-OES18 scores at weeks 12 and 18.

Abbreviations: ICC, investigator-chosen chemotherapy; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least square; n, patients with baseline and at least one post-baseline measurement; QLQ-OES18, Quality-of-Life Questionnaire – Oesophageal Cancer Module.

Dysphagia symptoms at week 12 remained stable in the tislelizumab arm (LS mean change = 0.8 [95% CI = −3.9 to 5.5]) and worsened in the ICC arm (LS mean change = 5.1 [95% CI = −1.0 to 11.3]); however, there was no difference between the two arms (difference in LS mean change = −4.3 [95% CI = −12.0 to 3.4], p =.27080). At week 18, the tislelizumab arm (LS mean change = −0.4 [95% CI = −5.9 to 5.2]) and the ICC arm (LS mean change = −0.9 [95% CI = −9.6 to 7.8] experienced similar changes from baseline in dysphagia symptoms, and there was no difference between the arms (difference in LS mean change = 0.6 [95% CI = −9.8 to 10.9], p =.9141).

With regards to eating symptoms, patients in the tislelizumab arm maintained their scores at week 12 (LS mean change = 0.4 [95% CI = −2.3 to 3.0]), while the ICC arm experienced worsening in problems with eating (LS mean change = 3.7 [95% CI = 0.2 to 7.1]); however, there was no difference between the arms (difference in LS mean change = −3.3 [95% CI = −7.6 to 1.0], p =.1315). At week 18, there was a difference in change from baseline in eating problems (difference in LS mean change = −5.7 [95% CI = −11.3 to 0.0], p =.0510), with the tislelizumab arm experiencing maintenance of eating problems (LS mean change = 1.1 [95% CI = −2.1 to 4.3]) and the ICC arm experiencing an increase in eating problems (LS mean change = 6.8 [95% CI = 2.0 to 11.5).

For reflux symptoms at week 12, there was a difference in change from baseline (difference in LS mean change = −5.7 [95% CI = −9.7 to −1.6], p =.0063), with the tislelizumab arm experiencing a reduction in reflux symptoms from baseline (LS mean change = −2.5 [95% CI = −4.9 to −0.1]) compared with the ICC arm, which experienced a worsening in reflux symptoms (LS mean change = 3.1 [95% CI = −0.1 to 6.4]). At week 18, both arms experienced a similar slight reduction from baseline in reflux symptoms, but the differences in change between the two arms were not substantial (difference in LS mean change = −1.1 [95% CI = −6.9 to 4.6], p =.6950).

Finally, for pain symptoms, tislelizumab-treated patients consistently maintained their scores at both week 12 (LS mean change = −1.6 [95% CI = −3.4 to 0.3]) and week 18 (LS mean change = −0.9 [95% CI = −3.7 to 1.8]), as did the ICC-treated patients at both week 12 (LS mean change = −1.7 [95% CI = −4.2 to 0.8]) and week 18 (LS mean change = 2.3 [95% CI = −1.9 to 6.4]). There were no differences in change from baseline between the two arms at either week 12 (difference in LS mean change = 0.1 [95% CI = −3.0 to 3.2], p =.9342) or week 18 (difference in LS mean change = −3.2 [95% CI = −8.1 to 1.7], p =.2022).

Discussion

The results of this post-hoc analysis of the Asian subgroup largely mirrored those previously reported in the ITT population of RATIONALE-302Citation13. Specifically, for the EORTC QLQ-C30, like in the ITT population, patients in the Asian subgroup who received tislelizumab experienced maintenance in GHS/QoL at weeks 12 and 18 while patients receiving ICC experienced a decline. Results similar to the ITT population were also found for physical functioning and fatigue in the Asian subgroup, with the ICC arm experiencing more fatigue at weeks 12 and 18 than the tislelizumab arm.

For the EORTC QLQ-OES18, the results for the Asian subgroup were again similar to the ITT population. The tislelizumab arm experienced maintenance in the symptoms index score while the ICC arm experienced worse symptoms relative to baseline, particularly at week 18. This was also found in the ITT population. For dysphagia, the ICC arm experienced a greater increase in symptoms compared with the tislelizumab arm in the ITT population, while in the Asian subgroup the tislelizumab arm experienced maintenance at both weeks 12 and 18, but the ICC arm had increased dysphagia symptoms at week 12. In addition, like the results from the ITT population, reflux improved at week 12 in the tislelizumab arm while worsening in the ICC arm. Changes from baseline in pain were similar in both arms of the Asian subgroup at weeks 12 and 18, mirroring the results of the ITT population.

The favorable results of the PRO endpoints are aligned with the improved tumor response of treatment with tislelizumab over ICC. Treatment with tislelizumab was associated with a higher objective response rate (20.3% vs 9.8%) and a more durable antitumor response (median = 7.1 vs 4.0 months) versus ICCCitation12. Future analysis will incorporate statistical modeling to investigate associations among the changes in PRO endpoints and the primary clinical endpoints as well as the incidence of adverse events and time to adverse events.

The outcomes of the current study were similar to previous findings of PD-(L)1 inhibitors in ESCC, however, patients in the RATIONALE-302 study were followed up for longer and treatment with tislelizumab had a positive effect on more symptoms than those reported in previous ESCC immune checkpoint inhibitor studiesCitation9,Citation10. Additionally, the post-hoc analysis reported here is one of the few that has analyzed PROs with a focus on the Asian population and throughout a longer period of time (weeks 12 and 18). While the ESCORT trial reported the effects of camrelizumab on GHS and fatigue in patients from China, their findings were limited to week 8 of treatmentCitation10. Similarly, in the KEYNOTE-181 trial, the reported maintenance in QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OES18 endpoints among patients treated with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy were limited to only week 9Citation9.

While the results of this study are encouraging, they should be considered alongside the following limitations. As expected, the completion rates at weeks 12 and 18 were lower than at baseline. However, the adjusted completion rates remained high in both arms at each assessment period. Within the mixed effect model for repeated measurements analysis, the missing at random assumption was used to consider the missing data. In addition, limitations regarding the open-label design could be applied.

Conclusions

The HRQoL and ESCC-related symptoms of patients in the Asian subgroup treated with tislelizumab were maintained or improved, while patients treated with ICC experienced worsening. These HRQoL results support the HRQoL findings in the total ITT population, indicating that tislelizumab monotherapy is a potential new second-line treatment option for patients with advanced or metastatic ESCC.

Transparency

Author contributions

Kim, Van Cutsem, Ajani, Shen, Kato, and Barnes were responsible or study design and data collection. Kim, Van Cutsem, Ajani, Shen, Barnes, Ding Tao, Xia, Zhan, and Kato were responsible for data interpretation and reviewing drafts of the manuscript. Ding and Barnes were responsible for data analysis.

Ethics statement

This protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the participating sites. The study was performed according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the requirements of the public registration of clinical trials. Written informed consent was obtained prior to participation in the study.

302PRO_Supplement_13Jan2023.docx

Download MS Word (17.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the investigative centers’ study staff and study patients and to recognize those from BeiGene, Ltd. who have substantially contributed to the development of this manuscript. Editorial assistance was provided by Jason C. Allaire, PhD (Generativity – Health Economics and Outcomes Research, Durham, NC). This assistance was funded by BeiGene, Ltd.

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by BeiGene, Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

SBK reports receiving research funding from Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, and DongKook Pharm Co. SBK also reports receiving consulting fees from and participating on in advisory boards for Novartis, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Dae Hwa Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, ISU Abxis, and Daiichi-Sankyo. SBK also reports owning stocks in Genopeaks and NeogeneTC. EVC reports receiving grants or contracts from Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Ipsen, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Roche, and Servier. EVC also reported receiving consulting fees from Array, Astellas, Astrazeneca, Bayer, BeiGene, Biocartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Daiichi-Sankyo, Halozyme, GSK, Incyte, Ipsen, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Servier, Sirtex, and Taiho. LS reports advisory board membership for BeiGene. KK reports receiving grants or contracts from the following ONO, BMS, MSD, Shionogi, BeiGene, Chugai, Astra Zeneca, BAYER, and Oncolys Biopharma. GB, ND, AT, TX, and LZ are employees of BeiGene. JA reports no conflicts.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Data availability statement

BeiGene voluntarily shares anonymous data on completed studies responsibly and provides qualified scientific and medical researchers access to anonymous data and supporting clinical trial documentation for clinical trials in dossiers for medicines and indications after submission and approval in the United States, China, and Europe. Clinical trials supporting subsequent local approvals, new indications, or combination products are eligible for sharing once corresponding regulatory approvals are achieved. BeiGene shares data only when permitted by applicable data privacy and security laws and regulations. In addition, data can only be shared when it is feasible to do so without compromising the privacy of study participants. Qualified researchers may submit data requests/research proposals for BeiGene review and consideration through BeiGene’s clinical trial webpage at https://www.beigene.com/our-science-and-medicines/our-clinical-trials/.

References

- Wang QL, Xie SH, Wahlin K, et al. Global time trends in the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:717–728. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S166078.

- Chen S, Zhou K, Yang L, et al. Racial differences in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: incidence and molecular features. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1204082. doi: 10.1155/2017/1204082.

- Uhlenhopp DJ, Then EO, Sunkara T, et al. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer: update in global trends, etiology and risk factors. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13(6):1010–1021. doi: 10.1007/s12328-020-01237-x.

- Sunde B, Lindblad M, Malmström M, et al. Health-related quality of life one year after the diagnosis of oesophageal cancer: a population-based study from the Swedish National Registry for Oesophageal and Gastric Cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1277. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-09007-9.

- Davis LE, Gupta V, Allen-Ayodabo C, et al. Patient-reported symptoms following diagnosis in esophagus cancer patients treated with palliative intent. Dis Esophagus. 2020;33(8):doz108. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz108.

- Ter Veer E, van Kleef JJ, Schokker S, et al. Prognostic and predictive factors for overall survival in metastatic oesophagogastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.07.132.

- van Kleef JJ, Dijksterhuis WPM, van den Boorn HG, et al. Prognostic value of patient-reported quality of life for survival in oesophagogastric cancer: analysis from the population-based POCOP study. Gastric Cancer. 2021;24(6):1203–1212. doi: 10.1007/s10120-021-01209-1.

- Takahashi M, Kato K, Okada M, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in Japanese patients with advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a subgroup analysis of a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial (ATTRACTION-3). Esophagus. 2021;18(1):90–99. doi: 10.1007/s10388-020-00794-x.

- Adenis A, Kulkarni AS, Girotto GC, et al. Impact of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy as second-line therapy for advanced esophageal cancer on health-related quality of life in KEYNOTE-181. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(4):382–391. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00601.

- Huang J, Xu J, Chen Y, et al. Camrelizumab versus investigator’s choice of chemotherapy as second-line therapy for advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCORT): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):832–842. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30110-8.

- Kato K, Cho BC, Takahashi M, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to previous chemotherapy (ATTRACTION-3): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(11):1506–1517. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30626-6.

- Shen L, Kato K, Kim SB, et al. Tislelizumab versus chemotherapy as second-line treatment for advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (RATIONALE-302): a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(26):3065–3076. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01926.

- Van Cutsem E, Kato K, Ajani J, et al. Tislelizumab versus chemotherapy as second-line treatment of advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (RATIONALE 302): impact on health-related quality of life. ESMO Open. 2022;7(4):100517. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100517.

- Wang J, Yu X, Barnes G, et al. The effects of tislelizumab plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment on health-related quality of life of patients with advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer: results from a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2021;30:100501. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100501.

- Lu S, Yu Y, Barnes G, et al. Examining the impact of tislelizumab added to chemotherapy on health-related quality-of-life outcomes in previously untreated patients with nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer J. 2022;28(2):96–104. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000583.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365.

- Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Hammerlid E, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(10):1384–1394. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00270-3.

- Luo H, Lu J, Bai Y, et al. Effect of camrelizumab vs placebo added to chemotherapy on survival and Progression-Free survival in patients with advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the ESCORT-1st randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326(10):916–925. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12836.

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims; [Published 2009. Cited 2022 Dec 1]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download.