Abstract

Objective

Although dosing regimens of targeted therapies (TT) for ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are guided by market authorizations and clinical guidelines, little is known about clinical guideline adherence or outcomes in patients receiving escalated doses of TT due to lack of response. This real-world study explored the prevalence of dose escalation and compared outcomes between patients receiving standard and escalated TT doses.

Methods

Data were from the 2020–2021 Adelphi Disease Specific Programme for inflammatory bowel disease, a cross-sectional survey of gastroenterologists and their UC and CD patients across five European countries and the US. Physicians provided retrospective data collection of patient demographics, clinical characteristics, treatment history, and satisfaction; patients reported quality-of-life and work productivity. Patients were grouped by TT maintenance dose; standard and escalated dose groups were compared. Outcomes were adjusted for time on current TT and severity at current TT initiation using regression analyses.

Results

Of 1,241 UC and 1,477 CD patients, 19.1% and 24.1%, respectively, received escalated TT doses. Despite escalation, a substantial proportion of patients had not achieved remission, had moderate or severe disease activity, or were flaring. Most physicians were not fully satisfied with treatment in the escalated dose group and were more likely to switch patients to another treatment regimen than patients on standard dose.

Conclusion

Dose escalation is not always an effective approach to resolve inadequate or loss of response in UC and CD, highlighting a need for more therapeutic options or alternative treatment strategies in patients unresponsive to TT.

Introduction

The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are chronic, relapsing and remitting, inflammatory conditions, characterized by debilitating gastrointestinal symptoms which increase healthcare and emotional burdens and reduce quality-of-life (QoL), ability to work, attend school, and be productive. Highest incidence and prevalence rates of IBD are reported in North America and Europe, though considerable variation both within and between geographic regions has been observedCitation1–3. Trends in prevalence rates also vary by region, while prevalence rates have started to drop in many parts of North America and Europe, rates in much of the rest of the world continue to increaseCitation4. In 2020, in newly industrialized regions in Asia and Latin America, the rapidly rising incidence of IBD was attributed to the improved detection of IBD and the westernization of societyCitation5.

Although the pathogenesis of IBD is not completely understood, it is thought to result from an inappropriate immune response to gastrointestinal antigens and/or environmental triggers in genetically susceptible individualsCitation6. The primary aim of medical management is therefore to induce and maintain remission, with the long-term goals of preventing hospitalization, disability, surgery, and colorectal cancer. Increased knowledge of the immunopathogenesis of IBD has led to the advent of targeted therapies (TT) that inhibit crucial mediators of the inflammatory process. These include biologic anti-tumor necrosis factors (anti-TNFs), integrin inhibitors, inhibitors of interleukin 12/23 (IL-12/23), small molecules such as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulatorsCitation7.

Several anti-TNFs (e.g. golimumab, adalimumab, and infliximab), the integrin inhibitor vedolizumab, and the IL 12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab are licensed for use in IBD, with JAK inhibitors tofacitinib, filgotinib, and upadacitinib, and S1P receptor modulator ozanimod also licensed for use in UC. Response to these medications is limited, however, with up to one third of patients with IBD found to have primary non-response or sub-optimal response to biologics and small moleculesCitation8. In addition, up to 50% of patients may experience loss of initial responseCitation8. This high rate of secondary loss of response prevents many patients from achieving stable, durable remission, allowing increased disease activity and progressionCitation9. It is therefore imperative that physicians understand when, and how, to optimize TTCitation8.

The decision to dose-escalate or stop an unsuccessful therapy is key to optimizing TT. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), in which drug concentrations in a patient’s bloodstream are measured at specific intervals, could aid this decision by indicating whether primary non-response or secondary loss of response is attributed to low drug concentrations or failed mechanism of actionCitation10. This approach may help physicians adjust TT regimens based on objective biomarkers instead of using empirical dosage escalation, or making symptom-based adjustmentsCitation11. While several studies have demonstrated that reactive TDM improves outcomes for some patients receiving anti-TNF therapy, proactive TDM may also provide a further strategy to avoid secondary loss of response to biologics, to improve the primary response of biological therapies and thus to improve long-term clinical outcomes in patients with IBDCitation11. Recent data indicate that proactive TDM is associated with better therapeutic outcomes than empiric dose escalation and/or reactive TDM in some anti-TNF agentsCitation11. However, despite this potential for dose-optimization, patients may still experience limited primary or increasing secondary loss of response. In addition, while several studies have shown that TDM and testing of anti-TNF antibody levels may lead to improved clinical outcomes and help guide the timing and appropriateness of dosage adjustmentsCitation12, further research is needed before TDM can be implemented for newer TTsCitation10. Moreover, limited access, due to cost and availability, may reduce the value of TDM, missing standardization of available assays and standardized cut-off values. Hence, at the current time, dosing regimens must be guided by market authorizations and clinical guidelines, indicating a need for greater knowledge regarding guideline adherence and outcomes in patients receiving escalated doses of TT.

Aim of the study

This real-world study aimed to assess the proportion of patients with UC and CD who are receiving standard and escalated maintenance doses of TT, and to compare the clinical status and patient-reported outcomes between these two groups.

Methods

Study design

Data were drawn from the Adelphi IBD Disease Specific Programme (DSP), a cross-sectional retrospective survey of gastroenterologists and their patients presenting in a real-world clinical setting in five European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom) and the United States (US) between January 2020 and March 2021. DSPs are large, multinational, observational studies collecting information on real-world clinical practice, designed to identify current disease management and patient- and physician-reported disease impactCitation13.

A geographically representative sample of physicians were recruited by local fieldwork agents, with physicians eligible to participate in the DSP if they were personally responsible for treatment decisions and management of patients with IBD. Physicians were invited to complete a record form for five to seven consecutive patients with UC and five to eight patients with CD under routine care. This record form comprised detailed retrospective questions on patient demographics, clinical characteristics, medication use, and healthcare resource utilization, including the number of healthcare consultations, imaging tests, and blood/laboratory tests in the previous 12 months. Physicians consulted existing patient clinical records and used their judgement and diagnostic skills to complete questionnaires. This was considered to be representative of decisions made in routine clinical practice.

Each patient for whom the physician completed a form was then invited to complete a patient-reported questionnaire, after providing informed consent to participate. The questionnaire collected data on the emotional and physical impact of the patient’s condition on their QoL and productivity, using the EQ-VASCitation14, Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ)Citation15, and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaireCitation16. The EQ-VAS measures the respondent’s current health state on a scale of 0–100, with 0 corresponding to the worst imaginable health state and 100 to the best imaginable health stateCitation14. THE SIBDQ total score assesses QoL in terms of social, emotional, and physical well-being on a scale of 10 (indicating worst health) to 70 (indicating best health)Citation15. The WPAI questionnaire measures IBD-related time missed from work and impairment of work and regular activities, with component scores reported as percentage impairment (0% indicates no impairment, 100% indicates total impairment)Citation16.

To allow for the classification of patients by disease activity (in remission/mild/moderate/severe), the components of the Mayo ScoreCitation17 for UC patients and Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI)Citation18 for CD patients were captured. For the Mayo Score, this included four physician-reported components: stool frequency, rectal bleeding, physician global assessment, and a measure of mucosal inflammation at endoscopyCitation17. The CDAI components comprised both physician- and patient-reported elements, meaning a CDAI score could only be calculated for those patients completing a patient-reported questionnaire.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if aged ≥18 years with a physician-confirmed diagnosis of UC or CD, were receiving maintenance TT, and were not involved in clinical trials. Patient-reported questionnaire forms were completed by the patient independently from their physician and returned in a sealed envelope, ensuring responses were kept confidential. Respondents who met the eligibility criteria were subsequently invited to participate in the full program and participation was solely dependent on the physician’s willingness to take part. Physicians were compensated for participating in the DSP according to fair market rates consistent with the time involved.

Data analysis

As the primary objective of the survey was descriptive (i.e. no a priori hypotheses specified), the sample size was fixed by the duration of the survey period. Patients in the maintenance phase of TT at the time of data collection were included and grouped by their prescribed dose:

Standard dose at standard frequency or equivalent (standard);

Higher than standard dose or increased frequency (escalated); and

Lower than standard dose or decreased frequency (de-escalated).

Missing data were not imputed; therefore, the base of patients for analysis could vary from variable to variable and is reported separately for each analysis. Categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and proportions, while normally distributed continuous data were expressed as means and standard deviations (SD) and not normally distributed data were expressed as medians and interquartile range [IQR]. Data for standard and escalated dose groups were compared using t-tests for numeric variables (where data is parametric), or Mann-Whitney for numeric variables (where data is non-parametric). Fisher’s exact test was used for binary outcomes and chi-squared tests for other categorical outcomes. All p values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Outcomes relating to patients’ current clinical status (disease activity and symptom severity), healthcare resource utilization, QoL, and current TT (performance, satisfaction, and likelihood of switching treatment) were adjusted for time on current TT and disease severity prior to initiation of current TT using linear, logistic, and multinomial logistic regressions. Data were expressed as adjusted means/percentages and standard errors (SE) as appropriate. Analysis was conducted in Stata Statistical Software 17Citation19.

Ethical considerations

A complete description of the methods of the survey has been previously published and validatedCitation13,Citation20,Citation21. Using a check box, patients provided informed consent for use of their anonymized and aggregated data for research and publication in scientific journals. Data were collected in such a way that patients and physicians could not be identified directly; all data were aggregated and de-identified before receipt. This research also obtained ethics approval from the Western Institutional Review Board (Study protocol number 1-1238963-1).

Results

Ulcerative colitis

Data were provided by 313 gastroenterologists (US, n = 84; Europe, n = 229) on a total of 1,241 patients with UC (US, n = 292; Europe, n = 949) that were included in the analysis dataset. Of the 1,241 patients with UC receiving maintenance doses of TT, 78.4% in the US and 72.7% in Europe were receiving standard doses and 19.1% in the US and 24.1% in Europe received escalated doses, with a small group receiving de-escalated doses (US, 2.5%; Europe, 3.2%). By TT class, 72.2% of patients on anti-TNFs, 79.7% on anti-integrins, 66.1% on anti-IL-12/23, and 84.6% on JAK inhibitors were receiving a standard dose. For escalated dose, this was 24.5%, 19.9%, 21.4%, and 15.4% (n = 8) respectively, and the remainder were receiving a de-escalated dose.

Patient demographics were similar across the standard and escalated dose groups with respect to age, sex, BMI, and duration of disease (all p >.05), and minimal differences were seen in extension of disease (). Patients in the US had been receiving their current regimen for a median (IQR) 12.3 (5.4–23.4) months, compared with 13.0 (7.7–24.3) months in Europe. In the US, 49.1% of patients on escalated dose and 34.9% of patients on standard dose had severe disease prior to initiation of current therapy (p = .06), while there was a significantly higher proportion of severe patients in the escalated dose group compared to the standard dose group in Europe (50.4% vs 36.7%, p <.01; ). A higher proportion of escalated dose patients in Europe were currently flaring compared to standard dose patients (17.3% vs 7.8%, p <.01; ). The current prescription and history of TT received in combination with conventional therapies was similar across patient groups; most patients were receiving TT as monotherapy (US, 57.1–57.6%, p = 1.00; Europe, 49.1–53.3%, p = .29; ), and 14.3% of escalated and 8.3% of standard dose patients in the US were receiving TT in combination with an immunomodulator, compared to 15.7% escalated and 15.2% standard dose patients in Europe. Steroids were prescribed to 10.7% of escalated and 9.6% of standard dose patients in the US at the time of survey, and 8.3% of escalated and 5.5% of standard dose patients in Europe, however, almost half of the patients received steroids immediately prior to the current TT (US, 38.3–40.6%, p = .84; Europe, 38.4–46.4%, p = .06; ).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients with ulcerative colitis.

Patients on escalated doses in the US had significantly more imaging tests within the last 12 months than standard dose patients (mean: 2.1 vs 1.5, p = .02). In Europe, escalated dose patients had significantly more blood/laboratory tests (mean: 20.8 vs 17.9, p <.01; ). No significant differences were observed in the proportion of patients undergoing surgeries in the last 12 months in either the US or Europe (p >.05; ). Patients across all dosage groups reported similar mean scores, with no significant differences, on both the SIBDQ and EQ-VAS, and similar levels of overall work and activity impairment in the WPAI (). However, patients in the US on escalated doses reported significantly more work time missed than those on a standard dose (18.6% vs 3.9%, p = .01; ).

Table 2. Healthcare resource utilization and patient reported outcomes of patients with ulcerative colitis.

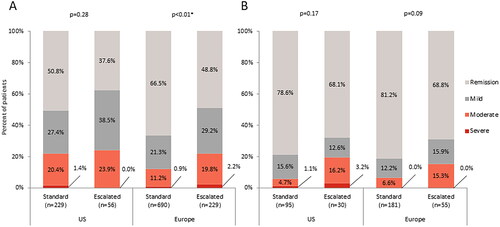

In the US, 62.4% of escalated dose patients and 49.2% of standard dose patients were not in remission, with 23.9% and 21.8% reported to have moderate or severe disease activity based on their Mayo score, respectively (p = .28). A similar trend was observed in Europe, with 51.2% of escalated dose patients and 33.5% of standard dose patients not in remission, of whom 22.0% and 12.1% were reported to have moderate or severe disease activity based on their Mayo score, respectively (p <.01; ).

Figure 1. Current disease activity in (a) patients with ulcerative colitis defined by Mayo score†, or (b) patients with Crohn’s disease defined by Crohn’s Disease Activity Index score‡.

Abbreviations: US, United States; Europe, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom; † Based on derived Mayo Score (remission: 0–2, mild: 3–5, moderate: 6–10, severe: 11–12); ‡ Based on derived Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) scores (remission: 0–150, mild: 151–219, moderate: 220–450, severe: 450–600); Data were collected on components of the Mayo Score/CDAI, allowing Mayo Score/CDAI to be calculated for patients; Data adjusted for time on and severity prior to initiation of current treatment; * Statistical significance at α = .05.

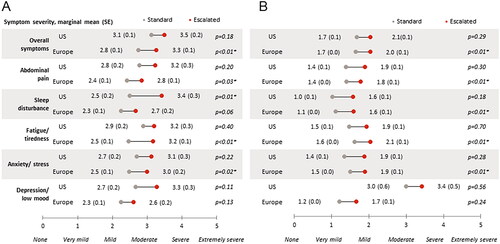

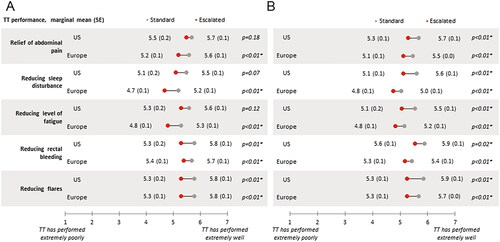

Among patients with moderate to severe disease activity, those receiving escalated doses were generally reported to be more severe than standard dose patients in terms of current symptom severity, with significant differences in sleep disturbance in the US, and in overall symptoms, abdominal pain, and anxiety in Europe (all p <.05; ). Physicians perceived significantly greater relief of abdominal pain, reduced sleep disturbance, fatigue, rectal bleeding, and flares among European patients receiving standard doses compared to patients on escalated doses (all p <.01); in the US, statistical significance was achieved only for reduced rectal bleeding (p = .01) and flares (p <.01; ).

Figure 2. Gastroenterologist-reported current symptom severity in (a) patients with moderate to severe disease activity for ulcerative colitis defined by Mayo score† or (b) patients with moderate to severe disease activity for Crohn’s disease Defined by Crohn’s Disease Activity Index score‡.

Abbreviations: US, United States; Europe, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom; SE, standard error; † Based on derived Mayo Score (remission: 0–2, mild: 3–5, moderate: 6–10, severe: 11–12); ‡ Based on derived Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) scores (remission: 0–150, mild: 151–219, moderate: 220–450, severe: 450–600); Includes moderate/severe patients with known data. Base sizes vary – Ulcerative colitis US: standard n = 48–49, escalated n = 15; Ulcerative colitis Europe: standard n = 78–83, escalated n = 47–51; Crohn’s disease US: standard n = 5, escalated n = 7; Crohn’s disease Europe: standard n = 11–12, escalated n = 8; Data adjusted for time on and severity prior to initiation of current treatment; * Statistical significance at α = .05.

Figure 3. Gastroenterologist-reported targeted therapy performance (adjusted mean scores) in (a) patients with ulcerative colitis, or (b) patients with Crohn’s disease.

Abbreviations: US, United States; Europe, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom; TT, targeted therapy; SE – standard error; Ulcerative colitis US: standard n = 229, escalated n = 55; Ulcerative colitis Europe: standard n = 690, escalated n = 228; Crohn’s disease US: standard n = 252, escalated n = 76; Crohn’s disease Europe: standard n = 844, escalated n = 247; Data adjusted for time on and severity prior to initiation of current treatment; * Statistical significance at α = .05.

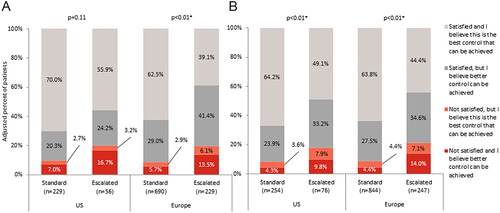

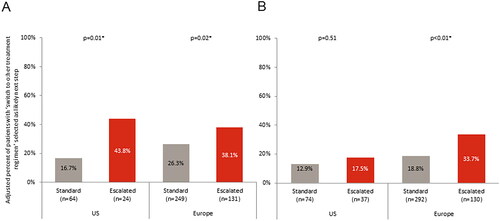

Physicians were dissatisfied with TT or were satisfied but believed better control could be achieved for 44.1% of patients on escalated doses in the US and 60.9% in Europe, compared with 30.0% of standard dose patients in the US and 37.5% in Europe (). Where the physician was not satisfied or believed better control could be achieved, patients on an escalated dose were significantly more likely to be switched to a different treatment regimen in both the US (43.8% vs 16.7%; p = .01) and Europe (38.1% vs 26.3%; p = .02) as the next step in their treatment pathway (). Patients who were receiving steroids were no more likely to be switched to a different treatment regimen than those not receiving steroids, irrespective of whether they were receiving a standard (22.3% vs 25.3%, p = .68) or escalated (38.6% vs 37.2%, p = .90) dose of TT.

Figure 4. Gastroenterologist satisfaction with current treatment in (a) patients with ulcerative colitis, or (b) patients with Crohn’s disease.

Abbreviations: US, United States; Europe, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom; Data adjusted for time on and severity prior to initiation of current treatment; * Statistical significance at α = .05.

Figure 5. Likelihood that a gastroenterologist will switch treatment regimen if not satisfied with current regimen in (a) patients with ulcerative colitis, or (b) patients with Crohn’s disease.

Abbreviations: US, United States; Europe, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom; Includes patients for which gastroenterologists selected “Not satisfied” with current control or “believe better control can be achieved”; Data adjusted for time on and severity prior to initiation of current treatment; * Statistical significance at α = .05.

Crohn’s disease

Data were provided by 320 gastroenterologists (US, n = 91; Europe, n = 229) for 1,477 patients with CD (US, n = 338; Europe, n = 1,139). Of these patients, 75.1% in the US and 74.1% in Europe were receiving standard doses and 22.5% in the US and 21.7% in Europe received escalated doses, with a small group receiving de-escalated doses (US, 2.4%; Europe, 4.2%). By TT class, 73.5% of patients on anti-TNFs, 81.9% on anti-integrins, and 72.9% on anti-IL-12/23 were receiving a standard dose, and 22.6%, 17.5%, and 21.7% were receiving an escalated dose, respectively. The remainder were receiving a de-escalated dose.

Patient demographics were similar across the standard and escalated groups in Europe with respect to age, sex, BMI, and disease duration (all p >.05; ). In the US, sex and disease duration were similar (p >.05), although some differences were seen between escalated and standard dose patients in terms of age (mean: 44.7 vs 39.0, p <.01) and BMI (26.5 vs 25.0, p =.02; ). No significant differences were seen in disease location between patients receiving escalated and standard doses. Significantly more patients on an escalated dose had severe disease prior to initiation of the current therapy compared to patients on a standard dose (US, 55.3% vs 30.6%, p <.01; Europe, 38.9% vs 31.6%, p = .04), with significantly more flaring disease in escalated dose patients (US, 23.4% vs 5.9%, p <.01; Europe, 14.3% vs 7.1%, p <.01; ). In the US, median (IQR) time on current TT was 12.2 (6.8–22.6) and 16.3 (8.4–32.9) months for escalated and standard dose patients, respectively. Patients in Europe on an escalated dose had been on their current therapy significantly longer than those on standard therapy (median [IQR] = 19.7 [9.5–35.4] vs 14.8 [8.8–28.0] months, p <.01).

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of patients with Crohn’s disease.

Steroids were prescribed in a significantly higher proportion of escalated dose patients compared to standard dose patients in both the US (22.4% vs 7.5%, p <.01) and Europe (11.7% vs 4.5%, p <.01). Immunomodulator combinations were used significantly more among patients on escalated therapy in Europe (28.7% vs 18.6%, p <.01). More than half of all patients were receiving anti-TNF in combination with immunomodulators, yet no significant differences were observed between standard and escalated dose patients in both the US and Europe regarding TT class and immunomodulator combinations (both p >.05). When adjusting for severity prior to initiation, and duration of current treatment, patients on escalated doses in the US had significantly more imaging tests than patients on standard dose within the last 12 months (mean = 2.3 vs 1.6, p <.01). Patients in Europe on escalated doses had significantly more healthcare consultations (mean = 8.3 vs 6.8, p <.01) and blood/laboratory tests (22.5 vs 18.7, p <.01) than patients on a standard dose (). A larger proportion of US patients on an escalated dose had experienced surgery in the last 12 months in relation to their disease than patients receiving a standard dose (26.8% vs 12.3%; p = .031), however no significant differences were seen between dosing groups in Europe regarding the proportion of patients that experienced surgery in the last 12 months (p = .084; ).

Table 4. Healthcare resource utilization and patient reported outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease.

Patients on escalated doses in Europe reported significantly worse scores on the SIBDQ compared to standard dose patients (mean = 45.8 vs 54.0; p <.01), and significantly lower EQ-VAS scores were observed in escalated dose patients in both the US (73.2 vs 81.6; p = .04) and Europe (68.5 vs 77.4; p <.01; ). Whereas patients in the US missed similar amounts of work time on both dose regimens (mean: 4.0 vs 5.2; p = .81), those on escalated doses had greater activity impairment (28.5 vs 18.0, p = .02) as measured by the WPAI. In Europe, patients on escalated doses missed significantly more work compared to those on a standard dose (mean = 16.7 vs 2.9, p <.01), and had greater activity impairment (36.0 vs 20.6, p <.01; ).

Of patients with known CDAI scores in the US, 31.9% of patients on an escalated dose were not in remission, compared to 21.4% of standard dose patients (p = .17). In Europe, 31.2% in the escalated group were not in remission, compared to 18.8% on a standard dose (p = .09). Of those patients on an escalated dose, 19.4% in the US and 15.3% in Europe had moderate or severe disease activity (). Among patients with moderate or severe CD activity, the only difference observed between standard and escalated dose patients was in Europe, where fatigue was reported as being more severe among standard dose patients (mean: 3.8 vs 2.9, p = .01; ). Physicians perceived significantly greater relief of abdominal pain, reduction of flares, rectal bleeding, sleep disturbance, and fatigue for patients receiving standard doses compared to patients on escalated doses in both the US and Europe (all p <.05; ).

Physicians were dissatisfied with TT or were satisfied but believed better control could be achieved for 50.9% of escalated patients in the US and 55.6% in Europe, compared with 35.8% of standard dose patients in the US (p <.01) and 36.2% in Europe (p <.01; ). Where the physician was not satisfied or believed better control could be achieved, patients in Europe on an escalated dose were significantly more likely to be switched to a different treatment regimen as the next step in their treatment pathway than standard dose patients (33.7% vs 18.8%; p <.01, ). Patients who were receiving steroids were no more likely to be switched to a different treatment regimen than those not receiving steroids, irrespective of whether they were receiving a standard (24.6% vs 16.4%, p = .19) or escalated (28.8% vs 31.6%, p = .76) dose of TT.

Discussion

This study of patients with IBD, in five major European countries and the US, aimed to assess the clinical care and impact of escalating TT in patients with inadequate response to a standard dosage regimen of various approved IBD treatments. In our study, 19.1% and 24.1% of patients with UC and CD, respectively, received an escalated dose of TT. Anti-TNFs were the most prevalent and commonly escalated TT class. Dose de-escalation was rarely observed, meaning no conclusions could be drawn due to limited sample sizes.

The low rates of dose de-escalation may be partly explained by a lack of evidence in support of a de-escalation strategy. In a systematic review of 20 studies with a total of 995 patients with IBD who had their biologic dose de-escalated, clinical relapse occurred in 0–54% of patients, with clinical relapse rates of 7–50% after 1 yearCitation22. Hence, while data relating to dose de-escalation is limited, this approach may lead to loss of response to treatment and negative outcomes.

Despite dose escalation, over half of the patients with UC and approximately one third with CD in our study had not achieved remission, with a substantial proportion reported to have moderate or severe disease activity currently and a significant proportion currently experiencing a flare. Moreover, physicians perceived greater response to treatment in relation to relief of a number of key symptoms among patients receiving a standard dose compared to an escalated dose. However, patients currently receiving an escalated dose are likely to have had their dose escalated due to a lack of response to the initial standard dose, suggesting potential mechanistic failure or a more severe or refractory disease course. Although it is to be expected that patients with more severe disease will be more difficult to treat, the high level of non-response indicates that current treatment optimization strategies, such as increased dose or frequency of TT administration, fail to maintain clinical response and remission in many patients.

For those patients who still experience inadequate clinical response despite dose escalation, rates of dissatisfaction with treatment and treatment switching are high. We found that more than half of the physicians overall were either dissatisfied with treatment or were satisfied but believed better control could be achieved in the escalated dose group in both patients with UC or CD. Physicians were also statistically significantly more likely to switch those patients to another treatment regimen than patients currently on their standard labelling dose. Similar results were observed in a previous real-world study of biologic use in IBD; while many patients discontinued their biologic treatment due to loss of response, side effects, or fear of side effects, the persistence profiles also suggested a high rate of dissatisfaction with the biologics assessed. This resulted in 20% switching to a different biologic and less than half of the patients staying on their initial biologics for 1 yearCitation23. A need for alternative treatment options exists for those patients not responding to dose-optimization, as loss of response is associated with higher rates of surgery, hospitalization, and/or prolonged corticosteroid use as well as impaired QoLCitation24.

The purpose of this study was not to analyze differences between US and Europe. Nevertheless, it was noteworthy that prescription behavior appeared to vary between regions; the different classes of TT were prescribed with comparable frequency in both regions in UC, whereas high levels of anti-TNF biologics were prescribed for CD in Europe. Steroid use was notably high in the US when compared to Europe, particularly in CD. In terms of HCRU, the low number of imaging tests performed for UC in the US was also noteworthy. Differences in clinical guidance and reimbursement polices likely account for many potential differences in prescribing and HCRU.

For more than a decade, anti-TNFs were the only available TT for patients with IBD. In recent years, the medical understanding of IBD pathogenesis has increased with the identification of novel therapeutic targets, such as IL-23, anti-adhesion strategies, or S1P modulation in UC or CDCitation7,Citation25. In our real-world study evaluating the clinical management of patients with IBD, the magnitude and benefit of dose escalation with TT highlight an unmet need for many UC and CD patients and the opportunity for alternative treatment options to maximize response and remission. In addition, while treatment optimization may be an appropriate and effective strategy for some patients, this study demonstrates that there is a subset of patients who do not respond to TT even when the dose is optimized. Further prospective studies are needed to identify predictors of sustained remission following dose escalation strategies in IBD, the role of dose escalation in clinical practice, and the increased potential for dose-optimization through the use of TDMCitation12.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered in the evaluation of our findings. Firstly, the DSP is not based on a true random sample of physicians or patients; while minimal inclusion criteria governed the selection of the participating physicians, participation is influenced by willingness to complete the survey. Patients participating in the surveys may also not reflect the general IBD population as patients who are visiting their physician are those who visit more frequently and may be more severely affected than those who do not consult their physician as frequently.

Secondly, physicians were asked to provide data for a consecutive series of patients to avoid selection bias, but no formal patient selection verification procedures were in place. Identification of the target patient group was based on the judgement of the respondent physician and not a formalized diagnostic checklist, although it was considered representative of a physician’s real-world classification of the patient. Since missing data were not imputed, the base of patients for analysis could vary from variable to variable and is reported separately for each analysis, and, while the duration of the current TT was known, the timepoint at which the dose of TT was escalated for each patient was not captured.

Furthermore, due to our patient selection and eligibility criteria, as well as chosen definitions of clinical response and remission, our population is likely to be heterogenous, and may be biased. However, this does reflect physicians’ opinions and thus is likely to be representative of current real-world clinical practice.

It should be noted that the survey was designed to facilitate understanding of real-world clinical practice, and thus physicians could only report on data they had to hand at the time of the consultation. Therefore, this represents the evidence they had when making any clinical treatment and other management decisions at that consultation. Finally, the cross-sectional design of this study means that previous treatment failures and disease course were not completely known and no conclusions about causal relationships can be drawn, although identification of significant associations was possible.

Despite such limitations, real-world studies are an important way to investigate clinical practices outside of the clinical trial setting. Real-world evidence generated from physician observation in normal clinical practice and patient reported data can identify factors of comparative clinical effectiveness and the personalization of patient care. In randomized controlled trials conducted among highly homogeneous groups of patients this is difficult and less representative of a wider population. As a result, data from real-world studies can complement clinical trials and provide insight into the effectiveness of interventions in patients commonly seen in clinical practice.

Conclusion

This real-world study found that approximately a fifth of patients with IBD were receiving an escalated dose of TT. The primary aim of medical management in IBD is to induce and maintain remission, however this is not achieved in a significant proportion of patients, even with escalated doses of TT. Our findings therefore suggest that the dose escalation strategy is not always an effective approach to resolve loss of response in IBD, confirming and expanding on previous single-country analysisCitation26. Hence, our data highlight the need for more therapeutic options to treat patients with IBD and achieve optimal treatment response.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Data collection was undertaken by Adelphi Real World as part of an independent survey, entitled the Adelphi Real World IBD DSP. The analysis described here used data from the Adelphi Real World IBD DSP. The DSP is a wholly owned Adelphi product. Eli Lilly and Company is one of multiple subscribers to the DSP. Eli Lilly and Company did not influence the original survey through either contribution to the design of questionnaires or data collection.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Axel Dignass has received fees for participation in clinical trials, review activities, such as data monitoring boards, statistical analysis, and end point committees from Falk, Abivax, AbbVie, Janssen, Gilead, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, and Pfizer; consultancy fees from AbbVie, MSD, Ferring, Roche/Genentech, Takeda, Vifor, Pharmacosmos, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Galapagos, Biogen, Celltrion, Falk, Janssen, Pfizer, Sandoz/Hexal, Fresenius Kabi, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, Tillotts, Lilly, Amgen, and Fresenius Kabi; payment from lectures including service on speakers bureaus from Falk Foundation, Ferring, MSD, Amgen, AbbVie, Vifor, Janssen, Pfizer, Tillotts, Takeda, Biogen, Lilly, and Gilead/Galapagos. Isabel Redondo, Petra Streit, Susanne Hartz, Gamze Gurses, and Theresa Hunter are all employees of Eli Lilly and Company, and may hold stock or stock options. Hannah Knight, Sophie Barlow, and Niamh Harvey are employees of Adelphi Real World. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Axel Dignass: Investigation (supporting); Supervision (equal); Writing – review and editing (equal). Isabel Redondo: Supervision (equal); Writing – review and editing (equal). Petra Streit: Supervision (equal); Writing – review and editing (equal). Susanne Hartz: Supervision (equal); Writing – review and editing (equal). Gamze Gurses: Supervision (equal); Writing – review and editing (equal). Hannah Knight: Investigation (lead); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Resources (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing – review and editing (equal). Sophie Barlow: Formal analysis (lead); Methodology (equal); Software (lead); Validation (lead); Writing – review and editing (equal). Niamh Harvey: Methodology (supporting); Project administration (equal); Resources (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing – review and editing (equal). Theresa Hunter: Conceptualization (lead); Project administration (equal); Supervision (equal); Writing – review and editing (equal). Theresa Hunter is acting as the submission’s guarantor. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support (including development of a draft outline and subsequent drafts in consultation with the authors, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copy editing, fact checking, and referencing) was provided by K. Ian Johnson BSc, MBPS, SRPharmS, Harrogate House, Macclesfield, UK and funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Data availability statement

All data, i.e. methodology, materials, data, and data analysis, that support the findings of this survey are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. All requests for access should be addressed directly to Hannah Knight ([email protected]).

References

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46–54.e42; quiz e30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001.

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769–2778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0.

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1756–1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32126-2.

- Wang R, Li Z, Liu S, et al. Global, regional and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e065186. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065186.

- Kaplan GG, Windsor JW. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(1):56–66. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00360-x.

- D’Haens G, Lindsay JO, Panaccione R, et al. Ulcerative colitis: shifting sands. Drugs R D. 2019;19(2):227–234. doi: 10.1007/s40268-019-0263-2.

- Atreya R, Neurath MF. IL-23 blockade in anti-TNF refractory IBD: from mechanisms to clinical reality. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(Supplement_2):ii54–ii63. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac007.

- Annese V, Nathwani R, Alkhatry M, et al. Optimizing biologic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a Delphi consensus in the United Arab Emirates. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211065329. doi: 10.1177/17562848211065329.

- Privitera G, Pugliese D, Lopetuso LR, et al. Novel trends with biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: sequential and combined approaches. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211006669. doi: 10.1177/17562848211006669.

- Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Therapeutic drug monitoring in patients on biologics: lessons from gastroenterology. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2020;32(4):371–379. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000713.

- Wu JF. Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: how, when, and for whom? Gut Liver. 2022;16(4):515–524. doi: 10.5009/gnl210262.

- Ehrenberg R, Griffith J, Theigs C, et al. Dose escalation assessment among targeted immunomodulators in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(6):758–765. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2020.19388.

- Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, et al. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: Disease-Specific Programmes—a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–3072. doi: 10.1185/03007990802457040.

- Szende A, Janssen B, Cabases J, editors. Self-reported population health: an international perspective based on EQ-5D. Dordrecht (The Netherlands): Springer; 2014.

- Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(8):1571–1578.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006.

- Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68(Suppl 3):s1–s106. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484.

- Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, et al. Development of a Crohn’s Disease Activity Index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70(3):439–444. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(76)80163-1.

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station (TX): StataCorp LLC; 2021.

- Babineaux SM, Curtis B, Holbrook T, et al. Evidence for validity of a national physician and patient-reported, cross-sectional survey in China and UK: the Disease Specific Programme. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e010352. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010352.

- Higgins V, Piercy J, Roughley A, et al. Trends in medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term view of real-world treatment between 2000 and 2015. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:371–380. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S120101.

- Little DHW, Tabatabavakili S, Shaffer SR, et al. Effectiveness of dose de-escalation of biologic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(11):1768–1774. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000783.

- Chen C, Hartzema AG, Xiao H, et al. Real-world pattern of biologic use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: treatment persistence, switching, and importance of concurrent immunosuppressive therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(8):1417–1427. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz001.

- Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Kierkus J, et al. Efficacy and safety of mirikizumab in a randomized phase 2 study of patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(2):495–508. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.050.

- Gottlieb ZS, Sands BE. Personalised medicine with IL-23 blockers: myth or reality? J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(Supplement_2):ii73–ii94. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab190.

- Khan S, Rupniewska E, Neighbors M, et al. Real-world evidence on adherence, persistence, switching and dose escalation with biologics in adult inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: a systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(4):495–507. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12830.