Abstract

Objective

To assess the journey of individuals from experiencing a traumatic event through onset of symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Methods

Patient- and psychiatrist-level data was collected (02/2022–05/2022) from psychiatrists who treated ≥1 civilian adult diagnosed with PTSD. Eligible charts covered civilian adults diagnosed with PTSD (2016–2020), receiving ≥1 PTSD-related treatment (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], atypical antipsychotics [AAs]), and having ≥1 medical visit in the last 12 months. Collected information included clinical and treatment characteristics surrounding the PTSD diagnosis.

Results

A total of 273 psychiatrists contributed data on 687 patients with PTSD (average age 36.1; 60.4% female). On average, the traumatic event and symptom onset occurred 8.7 years and 6.5 years prior to PTSD diagnosis, respectively. In the 6 months before diagnosis, 88.9% of patients had received a PTSD-related treatment. At time of diagnosis, 87.8% of patients had intrusion symptoms and 78.9% had alterations in cognition/mood; 41.2% had depressive disorder and 38.7% had anxiety. Diagnosis prompted treatment changes for 79.3% of patients, receiving treatment within 1.9 months on average, often with a first-line SSRI as either monotherapy (52.8%) or combination (24.9%). At the end of the 24-month study period, 34.4% of patients achieved psychiatrist-recorded remission. A total of 23.0% of psychiatrists expressed dissatisfaction with approved PTSD treatments, with 88.3% at least somewhat likely to prescribe AAs despite lack of FDA approval.

Conclusion

PTSD presents heterogeneously, with an extensive journey from trauma to diagnosis with low remission rates and limited treatment options.

1. Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex and debilitating neuropsychiatric disorder that can occur in individuals following personal or indirect exposure to traumatic events, such as actual or threatened death, physical or sexual abuse, combat, serious accidents, and natural disastersCitation1. Manifestation of PTSD is heterogeneous and includes four core symptom clusters: intrusion symptoms such as recurring unwanted traumatic memories, persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivityCitation1,Citation2. Posttraumatic reactions of individuals vary widely and may range from resilient to those that are major and chronicCitation3.

PTSD inflicts a substantial humanistic and economic burden. The condition is associated with frequent psychiatric and somatic comorbidities (e.g. depression, anxiety, suicidality, substance use disorder, pain, sleep disturbances), marked functional disability, psychosocial dysfunction, premature death, and increased medical and mental health service useCitation4,Citation5. The annual excess economic burden associated with PTSD among adults in the United States (U.S.) has been estimated at $232 billion in 2018, with over 80% of the burden borne by civilian adults, primarily in direct healthcare and unemployment costsCitation6.

In the U.S. general population, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD is estimated at 6.1%, with higher prevalence rates among women, younger adults, and those with lower education and incomeCitation7. Nonetheless, it has been recognized that PTSD is frequently undiagnosed or misdiagnosed in both primaryCitation8,Citation9 and secondary care settingsCitation10 for patient-driven reasons (e.g. hesitation to disclose trauma and seek care, fear of repercussions) or physician-driven reasons (e.g. lack of recognition of PTSD symptoms that overlap with other psychiatric comorbidities, reluctance to ask patients about trauma) Citation11–13. Importantly, a prior study has shown that undiagnosed individuals may experience comorbidities and use healthcare services (e.g. inpatient admissions) at levels that are similar to that of patients with diagnosed PTSDCitation14, suggesting that improved detection of PTSD to prompt a formal diagnosis of PTSD may be important to facilitate the initiation of proper PTSD-targeted treatment.

For patients with diagnosed PTSD, most evidence-based guidelines recommend psychotherapy, including both general cognitive behavioral therapy and trauma-focused psychotherapies, as the cornerstone treatmentCitation15–17. Pharmacological treatments are also recommendedCitation16, and real-world studies have suggested that pharmacological treatments may be used to manage more severe PTSD symptoms and PTSD-related comorbidities in clinical practiceCitation18,Citation19; but with limited approved options, symptoms can be difficult to manage. The American Psychological Association recommends four agents for the treatment of PTSD, including three selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), namely fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, and one serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), venlafaxineCitation3. Of these therapies, only paroxetine and sertraline are currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of PTSD; however, response rates to SSRIs rarely exceeds 60%Citation20. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) guidelines further recommend off-label use of antipsychotic medication, particularly quetiapineCitation21, as a second-line treatment. Prior studies have also noted some evidence of the effectiveness of agents such as prazosin and risperidone when added to an SSRI or SNRICitation22–24.

The diagnosis and management of PTSD may be more challenging among civilians compared to veterans, given less access to dedicated screening and care programs compared to those provided by the Veterans Health AdministrationCitation25,Citation26. To date, research on general civilian adults with PTSD remains more limited compared to other commonly identified subgroups of individuals with PTSD such as veterans or childrenCitation27–29, and there is scarce literature characterizing the journey of adult civilians with PTSD in the U.S., particularly of patients with more severe symptoms who may require pharmacological treatment.

Knowledge on the patient journey from trauma exposure to pre-diagnosis disease and treatment history and to post-diagnosis clinical trajectory may help identify unmet needs and areas for interventions to reduce PTSD burden, which could be particularly crucial for patients with more severe symptoms requiring pharmacological treatment. Therefore, the current study aimed to add to the scarce literature on PTSD in civilian adults and provide a comprehensive description of characteristics and treatment patterns of U.S. civilian adults diagnosed with, and pharmacologically treated for, PTSD by a psychiatrist. Medical charts were abstracted by psychiatrists, whose clinical practices and perspectives on civilian PTSD management, including potential reasons for not documenting a PTSD diagnosis, were described. Furthermore, this study sought to understand the civilian adult patient journey before and after receiving a PTSD diagnosis to identify the timing of key clinical milestones as well as potential diagnosis and treatment delays, treatment patterns, and their impact on patients’ clinical trajectories.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

This descriptive retrospective panel-based chart review study analyzed anonymized data obtained through an online medical chart abstraction conducted from February to May 2022. Psychiatrists in the U.S. who treat patients with PTSD were recruited among one of the largest panels of healthcare providers in the U.S., M3 Global Research, which is representative of the American Medical Association Masterfile. An email invitation was sent to eligible psychiatrists who met the following eligibility criteria: (1) practicing psychiatry in the U.S.; (2) had diagnosed and treated at least one adult patient with PTSD; (3) had access to detailed patient medical charts, including the traumatic event(s), diagnosis, treatments received, treatment patterns, and reasons for treatment changes for at least 24 months following the PTSD diagnosis; and (4) were willing to provide information from at least one patient’s medical chart. Eligible psychiatrists who were willing to participate provided their written informed consent. Participating psychiatrists were asked to provide patient-level clinical information on 1–5 patients with PTSD via an electronic case report form (eCRF) designed specifically for this study. To minimize selection bias, psychiatrists were asked to compile a list of patients who met the selection criteria and enter information for an individual patient whose last name began with a letter randomly generated by the survey.

The collected data did not include any patient-identifying information. This study was conducted in accordance with the applicable ethical regulations; it was exempt from full review and approved through an expedited review by the Western Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board (work order: 1-1485181-1).

To capture a population of treated patients with PTSD with the goal of assessing treatment patterns, patients meeting the following eligibility criteria were included in the study: (1) at least 18 years of age at the time of the PTSD diagnosis; (2) not an active military member or a veteran, and without military healthcare coverage (i.e. civilian); (3) treated with at least one PTSD-related therapeutic agent (i.e. SSRI, SNRI, atypical antipsychotic [AA]) on or following the PTSD diagnosis; and (4) had at least one recorded visit with the participating psychiatrist in the 24 months following the PTSD diagnosis. SSRIs, SNRIs, and AAs were selected to determine whether patients were treated, as these categories broadly capture commonly used therapies for PTSD, in accordance with treatment guidelines. Information on augmenting agents, such as benzodiazepines and anti-hypertensive agents, was also collectedCitation3,Citation22–24.

The study index date was the date of the formal PTSD diagnosis, the pre-diagnosis period was the 6-month period prior to the index date, and the post-diagnosis period was the 24-month period following the index date.

2.2. Measures

Psychiatrist characteristics, including demographics (e.g. age, gender), clinical practice characteristics (e.g. practice type, size, region), and reasons for documenting and not documenting a PTSD diagnosis were summarized.

Data collected from the patient chart review included demographics on the index date, information about the traumatic event(s), and clinical and disease characteristics (e.g. comorbidities, symptoms, physician-reported PTSD severity). Treatment characteristics were captured as nonpharmacological treatments (e.g. trauma-focused psychotherapies, non-trauma-focused psychotherapies), PTSD-related therapeutic agents (SSRIs, SNRIs, AAs), and PTSD-related augmenting agents that may be used to treat symptoms of PTSD (e.g. benzodiazepines, antihypertensives). Psychiatrists were asked to report reasons for initiating treatments, the direct treatment changes occurring following the PTSD diagnosis, and whether remission from PTSD (i.e. patients no longer met the clinical criteria for PTSD) had occurred by the end of the 24-month post-diagnosis period. Patient journey was assessed by capturing the timing of the traumatic event(s), PTSD symptom presentation, PTSD diagnosis, treatment initiation, and remission, as available.

2.3. Data analysis

Means, medians, interquartile ranges, and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables. Counts and percentages were reported for categorical variables.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Enterprise Guide, Version 7.1 (SAS, Cary, North Carolina, U.S.) and R 4.1.0 (R Core Team, 2021). Sankey plots were generated to visualize treatment sequences: the nodes represent treatment regimens during the 6-month pre-diagnosis period, as of the index date, and up to 3 lines of therapy in the 24-month post-diagnosis period; the links represent the proportion of patients receiving the line of therapy at each node.

3. Results

3.1. Psychiatrist characteristics

A total of 273 psychiatrists treating adults with PTSD participated in the study (). The majority were 35–64 years old (75.8%), male (60.1%), practiced general psychiatry (93.0%), and were in private/community practice (67.8%). Participating psychiatrists followed an average of 396 civilian adult patients annually, 25% of which were estimated to have PTSD. Over half of participating psychiatrists (51.6%) reported that 50–100% of their civilian adult patients with PTSD had chronic PTSD (defined as PTSD symptoms persisting for at least 2 years). The average number of patient reviews contributed per psychiatrist was 2.5, with 41.8% of psychiatrists contributing data from a single patient chart.

Table 1. Psychiatrist and practice setting characteristics.

3.2. Psychiatrists’ reasons on documenting a diagnosis of PTSD

The most common reasons for not documenting a diagnosis of PTSD were symptoms remained sub-threshold (45.8%), at least partial symptom management by treatment of a comorbid condition (21.6%), and social or legal concerns (19.0%). The most frequent reasons given for documenting a diagnosis of PTSD were to facilitate targeted PTSD symptom management (92.7%), patient acceptance of their condition (58.2%), and PTSD-specific treatment access (56.0%; ).

Table 2. Psychiatrists’ reasons on documenting a diagnosis of PTSDTable Footnotea.

3.3. Patient characteristics at time of PTSD diagnosis

A total of 687 civilian adults with PTSD were included in the study (). As of the index date, patients were on average 36.1 years old, and the majority of patients were female (60.4%), white (64.5%), and had commercial/private insurance (58.8%). Almost half of patients with PTSD (43.8%) experienced a single traumatic event. The vast majority of patients (84.7%) experienced the traumatic event directly, 10.6% witnessed an event, and 2.5% learned that it had happened to a close family member or friend. The most frequently reported traumatic event(s) included interpersonal violence (48.3%), sexual relationship violence (39.4%), and interpersonal-network traumatic experience (14.0%).

Table 3. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics.

At the time of PTSD diagnosis, patients presented with a range of PTSD-related symptoms, including intrusion symptoms (87.8%), alterations in cognition and mood (78.9%), avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event(s) (77.9%), and alterations in arousal and reactivity (76.4%). Over 40% of patients had psychiatric comorbidities as of the index date, the most frequent being depressive disorder (41.2%), anxiety disorder (38.7%), insomnia (26.5%), substance use disorder (17.2%), and suicidal ideation (12.7%).

3.4. Patient journey

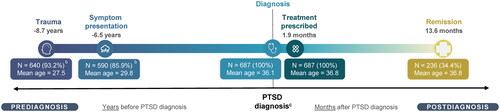

The overall patient journey depicting the mean times between key clinical milestones, both before and after PTSD diagnosis, is presented in . On average, the time from trauma to symptom presentation was 2.2 years, a formal PTSD diagnosis was documented on average 6.5 years following symptom onset, pharmacological treatment was prescribed within an average of 1.9 months of the PTSD diagnosis, and of the 34.4% of patients who achieved remission, remission occurred within an average of 13.6 months from the diagnosis.

Figure 1. Description of patient journey among adults with PTSDa. Abbreviations. N, number; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder. aAverage time from PTSD diagnosis to reported trauma, symptom presentation, pharmacological treatment prescription, and remission, as applicable. All average time points are out of patients with psychiatrist reported dates of events. Average age of the patient at each time point is also reported. bReported for charts where the exact time from traumatic event or symptom presentation to PTSD diagnosis was collected. cThe origin is set to the time of PTSD diagnosis. The horizontal axis is presented in years for the pre-diagnosis period and months for the post-diagnosis period.

3.5. Impact of PTSD diagnosis on treatment and disease characteristics

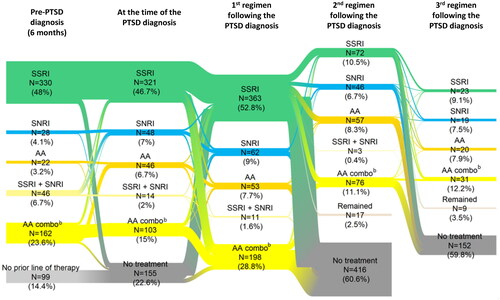

The treatment characteristics as of the index date and in the 6-month pre-diagnosis period are presented in . In the 6 months prior to a formal PTSD diagnosis, half of patients (50.1%) received nonpharmacological therapy, including trauma-focused psychotherapy (27.5%) and non-trauma-focused psychotherapy (28.5%). Most patients (85.6%) received treatments commonly used for PTSD (i.e. an SSRI, SNRI, and/or AA) prior to receiving a PTSD diagnosis, including 48.0% who received an SSRI in monotherapy and 23.6% who received an AA in combination with another PTSD-related agent (AA combo; ). In addition to the PTSD-related agents, 52.8% of patients had also received a PTSD-related augmenting agent prior to the diagnosis, including benzodiazepines/sedatives (29.5%), anti-hypertensive agents (18.5%), and other antidepressants (i.e. other than SSRI/SNRI; 11.8%).

Figure 2. Sankey diagram of PTSD-related pharmacological treatment sequences, with nodes representing the proportion of patients receiving each regimen at key stages from 6 months pre-PTSD diagnosis to 24 months post-PTSDa. Abbreviations. AA, atypical antipsychotic; N, number; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. aThe analysis was conducted at the agent level, but reported at the class level (i.e. change within class is a continuation, change to another class is a switch). bAA combo includes all treatment regimens with an AA and ≥1 other treatment class (i.e. SSRI or SNRI). Figure can be read left to right starting with treatment received prior to the PTSD diagnosis spanning to the right for up to 3 regimens following the PTSD diagnosis, as applicable. Width of each connecting band is proportional to the quantity represented.

Table 4. Impact of PTSD diagnosis on treatment characteristics.

The treatment characteristics during the 24-month post-diagnosis period are presented in . The majority of patients (58.8%) received at least 2 distinct PTSD-related agents within 24 months of diagnosis, with an average number of 1.6 distinct lines of therapy. Psychiatrists reported that the formal PTSD diagnosis led to a nonpharmacological treatment change in 32.9% of patients, most commonly to prescribe a new trauma-focused therapy (71.2%), and a pharmacological treatment change in 68.9% of patients. As first-line therapy post-PTSD diagnosis, 52.8% of patients received an SSRI in monotherapy, 9.0% received an SNRI in monotherapy, 7.7% received an AA in monotherapy, and 28.8% received an AA in combination with an SSRI and/or SNRI; as second-line therapy, 10.5% of patients received an SSRI in monotherapy, 8.3% received an AA in monotherapy, 6.7% received an SNRI in monotherapy, and 11.1% received an AA in combination with an SSRI and/or SNRI (). In addition to the PTSD-related agents in first-line therapy, 46.3% of patients received an augmenting agent and 28.8% received nonpharmacological therapy. Within the first line of therapy, 56.3% of patients experienced a dose change outside of any planned titration (i.e. increase or decrease in the dose of SSRI, SNRI, or AA). The most frequently reported reasons for any treatment change in the 24-month period following diagnosis were inadequate/suboptimal management of PTSD symptoms with prior treatment (51.5%) and initiation of targeted PTSD symptom management (30.7%; ). As of 24 months following the PTSD diagnosis, 82.7% of patients were no longer receiving a PTSD-related agent.

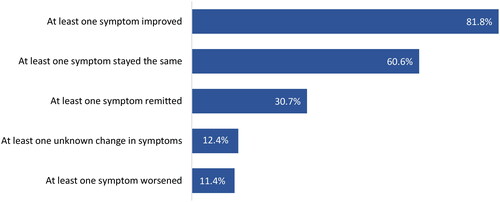

Psychiatrists reported that patients’ PTSD symptoms were most commonly assessed via general clinical interviews (90.5%), with just under a quarter (23.3%) assessed via self-report measures. At the time of diagnosis, almost half of patients (49.1%) presented with severe or extreme PTSD. In the 6-month period following the PTSD diagnosis, at least one symptom improved in 81.8% of patients, and at least one symptom remitted in 30.7% of patients ().

4. Discussion

This retrospective chart review study of civilian adults diagnosed with PTSD and treated with PTSD-related pharmacotherapy under a psychiatrist’s care highlights that PTSD is a highly heterogeneous condition with diverse clinical trajectories. Patients often experience multiple traumatic events, present with a complex symptom and comorbidity profile, and typically go through a lengthy patient journey with long intervals between the traumatic event(s), symptom onset, formal PTSD diagnosis, and treatment initiation. In addition to the substantial lag of over 6 years between symptom onset and initiation of pharmacological treatment for PTSD, patients were often observed with multiple lines of therapy, involving different combinations of trauma-focused and other psychotherapies, PTSD-related therapeutic agents, and augmenting agents. Within the 24 months following the PTSD diagnosis, just over one-third of patients achieved remission; yet, more than 80% of patients were no longer receiving a PTSD-related agent by that time. Collectively, the findings of this study underscore several unmet needs along the journey of civilians with PTSD in the U.S. in regard to long diagnosis and treatment delays, multiple treatment changes, low remission rates, and poor persistence to pharmacological treatments.

The high rates of PTSD-related treatments prior to a PTSD diagnosis found in this study may reflect the treatment of individual PTSD-related symptoms and/or related comorbidities, while overlooking or potentially misdiagnosing the underlying PTSD condition. PTSD has diverse manifestations and symptoms are often similar to those with other common mental health conditions (e.g. depression or anxiety), which, when compounded by patients’ reluctance to disclose the traumatic eventCitation11, may impede clinicians’ ability to distinguish PTSD from other conditions. A prior U.S.-based chart review of primary care patients with PTSD found that although 49% of patients had received a mental health treatment in the previous 12 months, most (71%) of those treated were diagnosed with depression, and only 18% were specifically diagnosed with PTSDCitation9. Additionally, a 2018 systematic review found that undetected PTSD was common in secondary care mental health services, presented in 28.6% of patientsCitation10. The current study also found that partial symptom management by comorbidity treatment was among the top reason for a psychiatrist to not document a PTSD diagnosis, which could have contributed to the underdiagnosis of PTSD. Together, these findings suggest that future research focusing on raising awareness of PTSD among civilians and clinicians and reducing mental health stigma may help alleviate some barriers to PTSD diagnosis and treatment.

Unlike veterans in the U.S. who have access to dedicated screening and care for PTSDCitation25, most civilians need to actively seek professional help for their PTSD symptoms and disclose their potentially sensitive traumatic experience to be diagnosed. Although military personnel were excluded from this study, the pre-existing work in this population is still relevant and should be leveraged when considering policy or programming that may benefit the civilian population. Despite a lack of studies on the impact of PTSD screening on treatment outcomes, the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense PTSD guidelinesCitation1 recommends periodic PTSD screening based partly on evidence of beneficial outcomes from screening for other psychiatric disorders, such as depression, in which primary care screening has been shown to be associated with a greater reduction and/or remission in depression symptomsCitation30. Furthermore, reducing the time between symptom onset and PTSD diagnosis through effective screening can help ensure patients obtain treatment earlier on in the disease course, which has been shown to outperform treatment as usual or no treatment among hospitalized civilian trauma survivorsCitation31. Further evidence to support early intervention in the context of PTSD is warranted, but the results from the current study describe a long period in which civilian patients may be struggling with PTSD symptoms without receiving targeted care, pointing to the potential benefits of developing and implementing PTSD screening tools for the wider population.

In addition to the long gap from symptom onset to PTSD diagnosis of 6.5 years, patients were also found to experience an average delay of 1.9 months between diagnosis and pharmacological treatment initiation. Overall, these diagnosis and treatment delays align with the findings of the 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III), a large U.S.-based national survey that found an average of 4.5 years elapsed from PTSD onset to first treatmentCitation7. Meanwhile, the delay in pharmacological treatment initiation is in line with a study among U.S. veterans that showed the time from PTSD diagnosis to first pharmacotherapy prescription ranged from 47 to 84 days (i.e. approximately 1.5–3 months) depending on the type of medication prescribed, which was in turn related to the type and severity of PTSD symptoms and comorbidities presentedCitation18.

Although PTSD-related treatment was frequently received prior to the PTSD diagnosis, the current analysis found that a formal PTSD diagnosis often led to a change in pharmacological treatment, followed by newly prescribed trauma-focused and non-trauma-focused psychotherapy, which may indicate residual core PTSD symptoms that were challenging to address without a formal PTSD diagnosis. Moreover, while the most frequently prescribed first-line pharmacological treatment was SSRI monotherapy, the use of AA monotherapy and combinations were also common, a finding that is consistent with previous studiesCitation19,Citation32. With limited approved therapies for PTSD, off-label use of AAs has been observed in clinical practice to manage specific PTSD-related symptoms and comorbidities such as psychosis, sleep disturbances, and depressionCitation18,Citation33,Citation34. Notably, both comorbid psychiatric (e.g. depression, anxiety) and somatic (e.g. pain, trouble sleeping, cardiovascular disease) conditions could have a considerable impact on the overall well-being of patients with PTSDCitation5,Citation35–38; thus, comorbidity management is a crucial component of PTSD careCitation3.

In the 6 months after diagnosis, most patients experienced improvement in at least one PTSD symptom (81.8%), suggesting that targeted PTSD care prompted by a diagnosis may lead to positive improvements in the patient’s condition. However, it is important to note that despite observed improvements in symptoms associated with PTSD-targeted therapy, the symptoms persist in some form, with only 34.4% of patients achieving clinically evaluated remission after 24 months. The remission rate is in line with that reported in a systematic review, which found an average remission rate of 44% after 40 months, although the rates varied widely across studiesCitation39. The current study also found that 82.7% of patients were no longer treated with a PTSD-related agent at 24 months post-diagnosis, suggesting poor persistence to pharmacological treatments despite ongoing symptoms. A meta-analytic study has suggested that untreated PTSD tends to persist over time, and PTSD is unlikely to spontaneously subside without an intervention once the initial remission period (i.e. within 3 months following a traumatic event) has passedCitation40. Another study has found that experience of multiple traumatic events may broaden the PTSD symptom spectrum and render the condition more difficult to treatCitation41, highlighting the importance of timely treatment provision and long-term persistence.

Multiple levels of interventions may be possible to help patients with PTSD become resilient and attain positive outcomesCitation42. Novel psychological intervention techniques and related policy programs informed by neuroscientific research such as those investigating the impact of traumatic stress on the whole brain network may help reduce the population burden of PTSDCitation42. With an increased understanding on the underlying pathology of PTSD, psychotherapy may be packaged and delivered with modified protocols to emphasize on core mechanisms or prioritize the most critical symptoms that may influence other symptoms or outcomes based on neural connectivityCitation43. Prior research in veterans has also suggested that changes in the severity of PTSD symptoms over time may differ by symptom clusters, and targeting hyperarousal symptoms at early stages of PTSD may help reduce subsequent symptoms of intrusion and avoidanceCitation44; future studies examining potential changes in various symptom clusters on the longitudinal course of PTSD among civilians may provide insight on more targeted interventions for individuals with PTSD. Meanwhile, research on more safe and effective pharmacological treatment options is also warranted to help advance PTSD care.

Historically, a majority of PTSD research has centered on combat-related PTSD in active-duty military members and veterans, who are disproportionately white and male. However, women are twice as likely to develop PTSD as men in the civilian population, and a growing body of research indicates disparities in patient and treatment characteristics linked to gender, race/ethnicity, age, cultural context, and socioeconomic statusCitation35. The current study helps to fill knowledge gaps pertaining to civilians by analyzing an exclusively civilian sample of patients treated for PTSD by psychiatrists in a real-world clinical setting, with gender, age, and race distribution largely reflecting the U.S. populationCitation7,Citation45,Citation46. Additional research focusing on the civilian population is needed to help raise awareness of PTSD manifestation in patients at risk and to enable treating physicians to identify and treat patients with PTSD earlier in the disease course, which may lead to improved patient outcomes.

4.1. Limitations

The findings of this study should be considered in light of limitations. Primarily, information captured by the study’s eCRF was input by the psychiatrist, and a second reporter was not required to assess inter-reporter reliability; therefore, data may be subject to miscoding. Furthermore, data collected are limited to information available in the patients’ medical record held by the psychiatrists participating in the study. Information was not available on healthcare services and treatments received outside of the psychiatrist’s care setting that were not recorded in the medical chart, and data collected was further limited to the questions asked as part of the eCRF. Therefore, complete information (e.g. comprehensive patient history and comorbidities, comprehensive treatment patterns and treatment dosing, etc.) was not available. The study included only psychiatrists accessible through the M3 panel who wished to participate in this study; accordingly, the sample may not be fully representative of the U.S. psychiatrist population treating adults with PTSD. Furthermore, although participating psychiatrists were instructed to select patients at random, selection bias may still arise (e.g. bias toward selecting patients recently seen by the treating psychiatrist, or with strongly favorable or unfavorable outcomes). Lastly, as per the design, this study focused on adult patients diagnosed with PTSD by a psychiatrist, who were treated with pharmacological agents. As such, it was not possible to compare the characteristics of treated and untreated adults with PTSD, or between adults with PTSD treated by other professionals (e.g. primary care physicians).

5. Conclusions

Findings from the present study highlight that civilian adults with PTSD represent a heterogeneous population with a range of traumatic experiences and clinical and treatment characteristics. Civilian patients with PTSD often contend with an extensive patient journey and a long delay from trauma to symptom onset, and to diagnosis. Patients had high rates of comorbidities and often received PTSD-related treatment prior to their formal PTSD diagnosis. Following diagnosis, patients commonly used concurrent psychotherapy, combination pharmacotherapy, and augmenting agents, potentially indicating the presence of residual core PTSD symptoms that are difficult to address. Taken together with the low remission rates observed, this study highlights the complex nature of PTSD that may pose challenges for psychiatrists to identify and treat appropriately, in part due to limited treatment options.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. and Lundbeck LLC. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Lori Davis has previously received consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Signant Health and research funding and/or materials from Alkermes, Aptinyx, Tonix, Social Finance, and Westat. Annette Urganus is an employee of Lundbeck LLC. Patrick Gagnon-Sanschagrin, Jessica Maitland, Jerome Bedard, Remi Bellefleur, Martin Cloutier, and Annie Guérin are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. and Lundbeck LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. Jyoti Aggarwal is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Patrick Gagnon-Sanschagrin, Jessica Maitland, Jerome Bedard, Remi Bellefleur, Martin Cloutier, and Annie Guérin contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. Lori Davis, Jyoti Aggarwal, and Annette Urganus contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the applicable ethical regulations; it was exempt from full review and approved through an expedited review by the Western Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board (work order: 1-1485181-1). Eligible psychiatrists who were willing to participate in the study provided their written informed consent.

Previous presentations

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the ASCP 2023 held May 30-June 2, 2023 in Miami Beach, FL, U.S. as a poster presentation.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by professional medical writers, Eva Chanda, MSc, and Flora Chik, PhD, MWC, employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. and Lundbeck LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder Washington, DC. 2017 [cited 2022 Nov 16]. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults 2017 [cited 2022 Nov 28]. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.

- Watson P. PTSD as a public mental health priority. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(7):61. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1032-1.

- McFarlane Ao AC, Graham DK. The ambivalence about accepting the prevalence somatic symptoms in PTSD: is PTSD a somatic disorder? J Psychiatr Res. 2021;143:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.030.

- Davis LL, Schein J, Cloutier M, et al. The economic burden of posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States from a societal perspective. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(3):21m14116. doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m14116.

- Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Chou SP, et al. The epidemiology of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions-III. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(8):1137–1148. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1208-5.

- Liebschutz J, Saitz R, Brower V, et al. PTSD in urban primary care: high prevalence and low physician recognition. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):719–726. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0161-0.

- Meltzer EC, Averbuch T, Samet JH, et al. Discrepancy in diagnosis and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): treatment for the wrong reason. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2012;39(2):190–201. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9263-x.

- Zammit S, Lewis C, Dawson S, et al. Undetected post-traumatic stress disorder in secondary-care mental health services: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(1):11–18. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2017.8.

- Thibodeau R, Merges E. On public stigma of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): effects of military vs. civilian setting and sexual vs. physical trauma. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2022. doi: 10.1007/s11469-022-00870-6.

- Campodonico C, Varese F, Berry K. Trauma and psychosis: a qualitative study exploring the perspectives of people with psychosis on the influence of traumatic experiences on psychotic symptoms and quality of life. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):213. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03808-3.

- Chessen CE, Comtois KA, Landes SJ. Untreated posttraumatic stress among persons with severe mental illness despite marked trauma and symptomatology. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(10):1201–1206. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.10.pss6210_1201.

- Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Schein J, Urganus A, et al. Identifying individuals with undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder in a large United States civilian population – A machine learning approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):630. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04267-6.

- Chen L, Zhang G, Hu M, et al. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing versus cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult posttraumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(6):443–451. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000306.

- Martin A, Naunton M, Kosari S, et al. Treatment guidelines for PTSD: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2021;10(18):4175. doi: 10.3390/jcm10184175.

- Mendes DD, Mello MF, Ventura P, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38(3):241–259. doi: 10.2190/PM.38.3.b.

- Harpaz-Rotem I, Rosenheck R, Mohamed S, et al. Initiation of pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder among veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan: a dimensional, symptom cluster approach. BJPsych Open. 2016;2(5):286–293. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.002451.

- Harpaz-Rotem I, Rosenheck RA, Mohamed S, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder among privately insured Americans. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(10):1184–1190. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.10.1184.

- Berger W, Mendlowicz MV, Marques-Portella C, et al. Pharmacologic alternatives to antidepressants in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.12.004.

- Crapanzano C, Damiani S, Casolaro I, et al. Quetiapine treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2023;21(1):49–56. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2023.21.1.49.

- Isaacson B. Mental disorders: posttraumatic stress disorder. FP Essent. 2020;495:23–30.

- Coventry PA, Meader N, Melton H, et al. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: systematic review and component network meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2020;17(8):e1003262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003262.

- Bisson JI. Pharmacological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(2):119–126. doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.105.001909.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Help for veterans. Washington (DC): National Center for PTSD; 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 5]. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/help_for_veterans.asp

- Vanneman ME, Harris AHS, Chen C, et al. Postdeployment behavioral health screens and linkage to the veterans health administration for army reserve component members. Psychiatr Serv. 2017; Aug 168(8):803–809. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600259.

- Davis LL, Ambrose SM, Newell JM, et al. Divalproex for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a retrospective chart review. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2005;9(4):278–283. doi: 10.1080/13651500500305564.

- Richardson JD, Fikretoglu D, Liu A, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation in the treatment of military-related PTSD with major depression: a retrospective chart review. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):86. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-86.

- Keeshin BR, Ding Q, Presson AP, et al. Use of prazosin for pediatric ptsd-associated nightmares and sleep disturbances: a retrospective chart review. Neurol Ther. 2017;6(2):247–257. doi: 10.1007/s40120-017-0078-4.

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380–387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392.

- deRoon-Cassini TA, Hunt JC, Geier TJ, et al. Screening and treating hospitalized trauma survivors for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(2):440–450. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002370.

- Davis LL, Urganus A, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, et al. Patient journey before and after a formal post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis in adults in the United States – A retrospective claims study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2023;10:1–10. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2023.2269839.

- Bajor LA, Balsara C, Osser DN. An evidence-based approach to psychopharmacology for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – 2022 update. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114840. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114840.

- Vilibić M, Peitl V, Živković M, et al. Quetiapine add-on therapy may improve persistent sleep disturbances in patients with PTSD on stabile combined SSRI and benzodiazepine combination: a one-group pretest-posttest study. Psychiatr Danub. 2022;34(2):245–252. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2022.245.

- Grasser LR, Javanbakht A. Treatments of posttraumatic stress disorder in civilian populations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(2):11. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-0994-3.

- Kovačić Petrović Z, Peraica T, Eterović M, et al. Combat posttraumatic stress disorder and quality of life: do somatic comorbidities matter? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207(2):53–58. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000928.

- Sagud M, Jaksic N, Vuksan-Cusa B, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a narrative review. Psychiat Danub. 2017;29(4):421–430. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2017.421.

- Wang S, Mosher C, Perkins AJ, et al. Post-intensive care unit psychiatric comorbidity and quality of life. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(10):831–835. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2827.

- Morina N, Wicherts JM, Lobbrecht J, et al. Remission from post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of long term outcome studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(3):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.03.002.

- Diamond PR, Airdrie JN, Hiller R, et al. Change in prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in the two years following trauma: a meta-analytic study. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2022;13(1):2066456. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2022.2066456.

- Hagenaars MA, Fisch I, van Minnen A. The effect of trauma onset and frequency on PTSD-associated symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2011;132(1-2):192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.02.017.

- Weems CF, Russell JD, Herringa RJ, et al. Translating the neuroscience of adverse childhood experiences to inform policy and foster population-level resilience. Am Psychol. 2021;76(2):188–202. doi: 10.1037/amp0000780.

- Weems CF. Getting effective intervention to individuals exposed to traumatic stress: dosage, delivery, packaging, and profiles. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;68:102154. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.102154.

- Solomon Z, Horesh D, Ein-Dor T. The longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters among war veterans. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(6):837–843. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04347.

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, et al. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol Med. 2011;41(1):71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401.

- USAFacts.org. Our changing population: United States 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 16]. https://usafacts.org/data/topics/people-society/population-and-demographics/our-changing-population.