Abstract

Objective

Peripheral neuropathy (PN) is one of the most common diseases of the peripheral nervous system. Symptoms range from mild sensory signs to severe neuropathic pain. Untreated PN is progressive and can lead to complications and impair quality of life (QoL). However, PN prevalence is underestimated in the general population and affected individuals often remain undiagnosed. This study aimed to contribute to the global generation of prevalence data and determine sociodemographic and disease-related characteristics of PN sufferers.

Methods

This cross-sectional study collected information on PN prevalence and associated factors in the adult population (40–65 years) of the Mexico City area. Participants were recruited in public places and screened for PN using the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument (MNSI). Subjects with PN answered the Neuropathy Total Symptom Score-6 (NTSS-6), the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36), and the QoL Pharmacoeconomic Questionnaire. Statistical analysis included descriptive methods and calculation of PN prevalence with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Of 3066 participants, 448 had PN based on the MNSI physical examination. The overall PN prevalence was 14.6%, with the highest (18.9%) seen in subjects aged 61–65 years. PN was undiagnosed in 82.6%, and 62.9% had never heard of PN. Although half of all subjects had only mild PN symptoms, QoL was impacted in 91.8%.

Conclusions

The results confirm that PN prevalence in the general population is high. Despite the disease burden, most affected persons are undiagnosed and unaware of the disease. Almost all felt their QoL was impacted. The data highlight the need to raise awareness and identify undiagnosed individuals to prevent complications.

Introduction

Peripheral neuropathy (PN) is the most common disorder of the peripheral nervous system in adults and results from damage to the peripheral nervous systemCitation1,Citation2. It presents in many clinical ways, depending on the type of peripheral nerves involved (i.e. sensory, motor, or autonomic) and the disease stageCitation1,Citation2. Typical sensory symptoms include numbness, tingling, and burning pain in the extremities, although motor and autonomic symptoms such as muscle weakness and sweating may also occurCitation1–3. PN can be caused by various underlying conditions, including systemic diseases such as diabetes, vitamin deficiencies (e.g. vitamin B1, B6, B12), certain medications, obesity, hereditary disorders, inflammatory and infectious causes, neoplasms, toxic agents, and alcoholCitation1,Citation4,Citation5. Diabetes is globally by far the most common identifiable cause, but PN can also be idiopathic (i.e. cause unknown) in up to every fourth affected personCitation4,Citation6,Citation7. As untreated PN is usually progressive, it will significantly affect quality of life (QoL) at some point. Subjects with PN not only experience QoL impairments due to physical restrictions but may also suffer from depression, anxiety, and an impaired social and working life, particularly when symptoms become painful or cause sleep disturbancesCitation8–11. In addition, PN strongly influences general health and can lead to serious complications such as fractures due to falls or the need for foot amputation due to ulceration, which in turn negatively affects morbidity and increases mortalityCitation12–14. To prevent the progression of PN and such complications, early diagnosis and treatment is of utmost importanceCitation13,Citation15. However, PN frequently remains undiagnosed for long periods of time and is often diagnosed late, for example, when symptoms become painful and bothersome or foot ulceration is already presentCitation15,Citation16.

General reasons for the late recognition of PN include the low awareness of the disease as well as the underestimation of its prevalence and its severe consequencesCitation13,Citation15,Citation16. As scientific data on the prevalence of PN in the general population are scarce, no clear picture of the burden of PN exists. Furthermore, there is a lack of awareness that PN affects a significant part of the general adult population, not only the elderly or patients with diagnosed chronic conditions, but often also adults aged 35 years and older. To make things more complicated, PN can develop over extended periods almost silently with hardly any symptoms; thus, neither patients nor physicians become aware of itCitation17. On the physicians’ side, many healthcare professionals (HCPs), especially in primary care, lack a diagnostic routine for PN and harmonized and established guidelines across regions are scarce. In addition, very limited time per patient at the office represents one of the biggest burdens, which is why physicians often have to prioritize and focus on complications which are top of mind for them or which they consider more relevant and/or severe (e.g. glucose control in diabetes)Citation13,Citation18. The main reasons for underdiagnosis on the patients’ side include difficulty in verbalizing symptoms, ignoring symptoms (especially early sensory signs) or incorrectly linking them to their age, hence, not seeking early adviceCitation19,Citation20.

Around 80% of patients with PN remain undiagnosedCitation21–23. The most recent published figures are similar across different countries and confirm the need to raise awareness in the community and among HCPs and educate on the importance of early diagnosis, especially as risk groups (e.g. people with diabetes or obesity) will continue to grow in the future. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the global number of people with diabetes is estimated to increase from approximately 537 million in 2021 to 783 million by 2045Citation24. As up to 50% of diabetics suffer from diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN)Citation12,Citation25,Citation26, it can be expected that the number of people with DPN will grow accordingly. After diabetes, obesity is emerging as the second most important risk factor for PNCitation27–29. According to the World Obesity Federation (WOF), the prevalence of obesity is expected to increase from 14% in 2020 to 24% in 2035, affecting nearly 2 billion adults, children, and adolescents by 2035Citation30.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of PN in the general population is not as well studied as that in diabetics, cancer patients or other risk groups, with only a few epidemiological studies—mostly from developed countries—being availableCitation16. In addition, figures vary considerably, and many studies also refer to other neuropathies besides PN or only focus on neuropathic pain. Estimates from the National Institute of Health (NIH) assume that around 6% of people in the US over 40 years are affected by some form of PNCitation31,Citation32, while a higher prevalence of 13.5% (>40 years) and of 39.2% (≥70 years) were found via monofilament testingCitation33. Data from the Asia-Pacific region are only available for India, where the estimated prevalence in the general population varies from 0.05 to 24%Citation34. For Latin America, data from Mexico suggest a prevalence of 9.7% among people over 60 yearsCitation35. However, despite varying estimates, experts agree that the overall prevalence of PN, regardless of different regions, is likely significantly higher than any published FiguresCitation4,Citation16.

To draw more attention to the high prevalence of PN, raise awareness, and enable earlier diagnosis and treatment, prevalence data from the general population are crucial but are currently not sufficiently available or are outdated. By focusing not only on well-known subgroups such as diabetics, this study aimed to generate critical data to contribute to the global body of evidence on the prevalence of PN by collecting information from the general population and identifying sociodemographic and disease-related characteristics of PN sufferers as well as the associated patient burden. Mexico was chosen as the country of study conduct as a representative of Latin America with a high prevalence of diabetics, obese people, and other risk groups, which is similar to that of other countries across regions. These data may increase awareness of PN and risk groups beyond diabetics and the sense of urgency among physicians, especially in the primary care setting, as well as knowledge about the disease among the general population.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional epidemiological multicenter study aimed to estimate the prevalence of PN in a population of adults between 40 and 65 years living in the metropolitan area of Mexico City. The study was conducted between May 2022 and April 2023. Participants were recruited in public places (e.g. MOL Plaza Tepeyac, Plaza MAC, downtown of Alcaldía de Coyoacan, Tezozomo park, bus station Central del Norte, subway stations) in the metropolitan area of Mexico City by mobile promoters. People who wished to participate made an appointment with the help of the promoter at one of nine selected clinical sites in Mexico City. All participants provided signed informed consent upon arrival for their single visit. Body temperature was measured, and symptoms of COVID-19 were ruled out before the examination. Persons with COVID-19 or with relatives with COVID-19 at home were excluded. All participants had a basic medical interview and completed the patient-administered part of the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument (MNSI). Following assessment of their lower extremities to confirm or exclude the presence of PN (MNSI physical examination), participants who had PN based on the physical examination results of the MNSI answered the remaining study questionnaires while participants without PN concluded their participation.

Neuropathy and quality of life questionnaires

The MNSI, originally developed and validated in diabetics to assess distal symmetrical PNCitation36,Citation37, has also been used in other populationsCitation38,Citation39 and consists of two separate assessments: a 15-item self-administered questionnaire and a lower extremity examination, including inspection and assessment of vibratory sensation and ankle reflexes by the HCP. While the patient component was available to the physician for assessment, participating sites defined PN as a physical examination MNSI score ≥2.5 without the patient component being considered. This represented a deviation from other studies, where a physical examination MNSI score of ≥2.5 along with a patient questionnaire MNSI score of ≥4 was defined as indicative of PNCitation36,Citation40. The MNSI was used as a screening tool for PN in this study.

The Neuropathy Total Symptom Score-6 (NTSS-6) is another neuropathy sensory symptom scale that has been validated in diabetics and others to assess the intensity and frequency of sensory PN symptomsCitation41–43. The NTSS-6 consists of six physician-administered questions that explore the symptoms numbness, prickling, burning, aching, lancinating pain, and allodynia. A score >6 indicates the clinical presence of neuropathic symptomsCitation44,Citation45. The NTSS-6 was only answered by subjects defined as having PN based on the MNSI screening, to assess symptom burden.

Both MNSI and NTSS-6 have been validated in English and are extensively used in clinical practice in different languages, such as SpanishCitation46–49.

To evaluate QoL, the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36v1) was used, including 36 questions to assess limitations in physical activities, social activities, and usual role activities as well as bodily pain, general mental health, vitality, and general health perceptions, providing scores for eight health-related domains as well as scores of a physical component summary (PCS) and a mental component summary (MCS)Citation50. SF-36 results will be published separately.

To collect data on socioeconomic aspects, participants with PN answered a self-administered QoL Pharmacoeconomic Questionnaire (QoL PE) with 56 questions. This questionnaire was developed specifically for this study by the study sponsor’s clinical research teams to collect data on PN diagnosis and associated challenges for patients as well as their knowledge of PN to gain insights into disease awareness. It also included questions about the symptoms of PN, the treatments used to relieve those symptoms, and the impact on QoL, daily activities, social life, and economic impact. The questionnaire was not validated. A certified translation of the QoL PE into Spanish has been provided by the contract research organization.

Ethical considerations

The study was an epidemiological study and, under Mexican law, required only the evaluation of an independent research and ethics committee. As the study was not a clinical trial, it was not registered in any clinical trial registry. Even though this study was not a clinical trial, all study procedures were conducted in accordance with the protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki with all its modifications, and with ICH Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice ICH E6 (R2) and with written informed consent from the study subjects.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated following a formula for sample size calculations for a proportionCitation51 based on the assumption that 16% of the population may have PN. The 95% confidence level (Z statistic 1.96) and precision (d = 0.013) led to a calculation of 3,055 subjects needed. Statistical analysis included the calculation of PN prevalence overall and by gender and age groups with accompanying 95% confidence intervals. MNSI differences between subjects with and without PN were analyzed using chi-square tests for categorical measures and by t-test for continuous measures (MNSI subject self-total score and MNSI physical total score). Statistical analysis was performed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.15 (Cary, NC, USA). In accordance with the epidemiological nature of the study, the majority of evaluations were simply descriptive methods (frequency responses to questionnaires). The analysis set comprised all participants (no exclusion of records).

Results

Demographic information

A total of 3066 subjects were included in this cross-sectional study. According to the MNSI results and the site-defined threshold for the physical examination score (≥2.5 with no patient component considered), 448 of those had PN, whereas 2,618 did not. MNSI differences were highly significant (p < .0001; except for amputations only) between subjects with and without PN (Supplementary Tables S1, S2 and S3). In the cohort of subjects with PN, 59.8% were female, while a slightly lower proportion (54.1%) was female in the cohort of subjects without PN. With 54.3 (7.74) years, the mean (SD) age was slightly higher in the PN cohort than in the cohort without PN ().

Table 1. Demographic information (all subjects).

Prevalence of PN

Based on the total number of subjects, the overall prevalence of PN was 14.6%. The PN prevalence increased with ascending age categories and was higher than in the overall cohort in subjects aged 61–65 years (18.9%), followed by subjects aged 56–60 years (17.3%), and subjects aged 51–55 years (15.0%). In contrast, the two youngest age subgroups had a PN prevalence lower than that of the overall cohort. In female subjects, PN prevalence was higher (15.9%) than in male subjects (also high at 13.0%). PN prevalence also increased with ascending BMI categories and was higher in obese subjects (16.0%) than in the overall cohort. Subjects with normal BMI still experienced PN at a high rate of 13.9% ().

Table 2. Prevalence of PN based on MNSI results (all subjects).

Symptoms and burden of PN

The occurrence of symptoms was surveyed in the MNSI, NTSS-6 and QoL PE questionnaire.

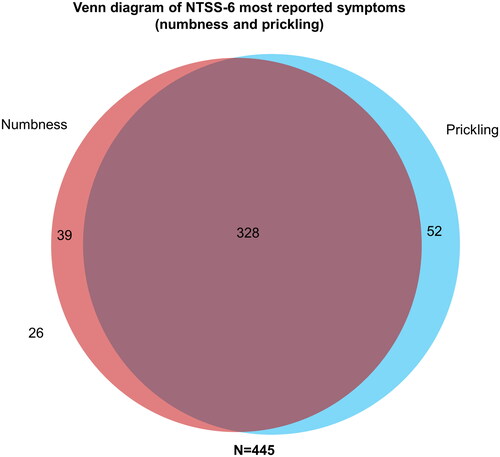

As three subjects with PN did not provide completed NTSS-6 questionnaires, results were only available for N = 445 subjects. Overall, numbness and prickling were the two most frequently reported symptoms according to the NTSS-6. In total, 94% (n = 419) of the PN subjects experienced either numbness OR prickling, and nearly three quarters (74%, n = 328) experienced both numbness AND prickling ().

Figure 1. Venn diagram of NTSS-6 most reported symptoms (numbness and prickling). Three of the 448 PN subjects had missing responses for NTSS-6. NTSS-6, Neuropathy Total Symptom Score-6; PN, peripheral neuropathy. Numbers in and next to circles are absolute numbers (n).

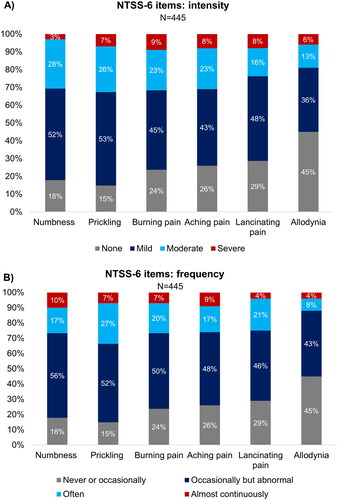

In terms of symptom intensity, most subjects had mild symptoms of numbness (52%), prickling (53%), burning pain (45%), aching pain (43%), and lancinating (stabbing) pain (48%), while the largest proportion of subjects (45%) had no symptoms of allodynia. The symptom with the largest proportion of subjects reporting severe manifestation was burning pain (9%) (). The frequency of symptoms as per NTSS-6 was mostly described as occasionally but abnormal for numbness (56%), prickling (52%), burning pain (50%), aching pain (48%), and lancinating pain (46%) (). Nearly two-thirds (64%) of the PN subjects experienced one or more symptoms at least one third of the time. Nearly one quarter (22%) of subjects experienced symptoms almost continuously (over two-thirds of the time) (Supplementary Figure S1). Beyond that, the MNSI patient questionnaires (available for all N = 448 PN subjects) revealed that 56.5% had worse symptoms at night (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 2. Intensity and frequency of NTSS-6 items in subjects with PN. Three subjects had missing responses for NTSS-6. NTSS-6, Neuropathy Total Symptom Score-6; PN, peripheral neuropathy.

QoL PE results were overall available for the total cohort of N = 448 subjects with PN, but several questions were answered by fewer subjects; therefore, the number of respondents differed per question. The majority of subjects with PN indicated that the disease affected their QoL (91.8%) and their family relationships (85.3%). Almost half of all subjects stated that it impacted their social lives (40.7%) and their professional lives (45.6%). In addition, 60.7% required assistance to perform their daily activities, while 20.1% had lost work days due to PN (Supplementary Figure S2), which summed up to a mean (SD) number of 5.6 (6.9) days per month in the last 6 months (Supplementary Table S4).

Diagnosis of PN and disease awareness

Overall, 62.9% of subjects with PN had never heard about the condition called PN before. Even more subjects (82.6%) had not received a formal PN diagnosis before, whereas 37.7% had at least been diagnosed with burning, tingling or numbness by a family doctor or specialist (Supplementary Figure S3).

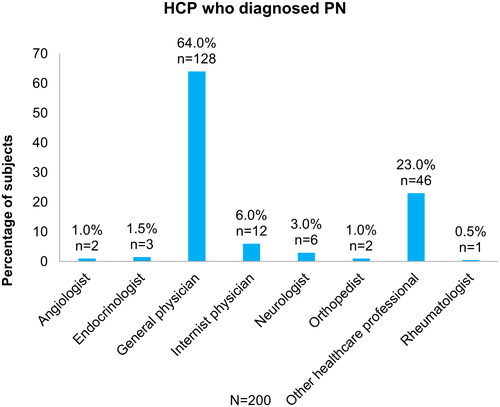

Subjects had suffered from symptoms 2.3 (3.07) years before being diagnosed. In addition, almost one quarter visited a doctor more than once due to PN symptoms before being diagnosed. Interestingly, the intensity of discomfort was rated similarly before and after PN diagnosis (). Most frequently, PN was diagnosed by general physicians (GPs; 64.0%), followed by other HCPs (23.0%), and internist physicians (6.0%) (). Only 15.6% saw a specialist after they were diagnosed ().

Figure 3. HCP who diagnosed PN. HCP, healthcare professional; PN, peripheral neuropathy. Data extracted from Quality of Life Pharmacoeconomic Questionnaire.

Table 3. Information regarding PN diagnosis (subjects with PN only).

Treatment of PN and PN-related symptoms

When asked what treatment their doctor prescribed after PN diagnosis, most subjects with PN mentioned anticonvulsants (29.0%), followed by B vitamins (23.5%) and non-opioid analgesics (20.0%), whereas 7.7% had not received any prescription. Most subjects did not take any supplements or herbal products in addition to the prescribed medication, but homeopathic medicine and other alternative products were mentioned by a few individuals ().

Table 4. Prescribed treatment and supplements taken in addition (subjects with PN only).

Discussion

This epidemiological cross-sectional study collected data from 3,066 subjects aged 40–65 years living in the metropolitan area of Mexico City. The primary objective was to estimate the prevalence of PN in the general adult population. The overall prevalence of PN was 14.6% in this study. As there are only few epidemiological studies estimating the prevalence of PN in general populations, with data mainly generated in European countries and the USCitation16, relating our results to existing data in similar populations is challenging. Several publications reported a lower prevalence in general populations, ranging from as low as 0.2% to 10%Citation4,Citation52,Citation53. With reference to Latin America, one Colombian study reported a PN prevalence of 2.2% in the general population >50 yearsCitation54. Yet, it should be considered that all these figures are mainly based on data collected 20–30 years ago. In contrast, a recent meta-analysis based on studies from six Latin American countries calculated a high PN prevalence of 28.6%, which was primarily driven by the large proportion of diabetics in the general populationCitation55. The prevalence observed in our study is closer to that confirmed by monofilament testing in two studies of US adults aged ≥40 years (13.5% and 14.8%)Citation33,Citation56. Across all age groups, our results are also considerably higher than the previously reported prevalence of 9.7% in the elderly Mexican populationCitation35, which may be mainly explained by methodological differences (i.e. the latter study was not designed to determine the prevalence of PN but to describe the association of frailty with diabetes in the elderly). Since our study was specifically designed to estimate PN prevalence in the general population, and the subjects’ PN status was based on the MNSI physician assessment, it is reasonable to assume that the prevalence observed herein is fairly accurate for the urban Mexican population. Furthermore, because the prevalence of various PN risk factors—including diabetes, prediabetes, and obesity—has increased significantly in recent decades, and demographic changes have increased the average age in the general population, it is likely that the prevalence of PN has also increased and will further increase proportionately. It is therefore plausible that more recent studies determine a higher prevalence than older ones.

Consistent with the well-established fact that age is a risk factor for PNCitation6,Citation57,Citation58, we also observed an increasing prevalence among older age groups (40–45: 10.1%; 46–50: 12.8%; 51–55: 15.0%; 56–60: 17.3%; 61–65: 18.9%). Reasons for the age-related rise include an increasing prevalence of diabetes, other metabolic or chronic diseases, polymedication—and thus drug-induced neuropathies associated with medications such as anticonvulsants, antibiotics, or antiarrhythmics—, as well as B vitamin deficiencies in the elderlyCitation59. Despite the proven higher risk of PN in older people, it is important to emphasize that PN does not solely occur in the elderly but is also widespread in younger age groups and should therefore not be overlooked in those. Since people between 40 and 65 years represent the working population with the greatest influence on the economy, this age span was one of the inclusion criteria for the current study.

Emerging evidence also supports the role of metabolic syndrome as a potential cause of PN, with obesity being a central driverCitation28. Consistent with this, we observed an increase in PN prevalence with increasing BMI, although the range of prevalence rates was narrow (normal BMI: 13.9%; obese BMI: 16.0%).

The most common PN symptoms in our study were numbness and prickling, followed by burning, aching or lancinating pain, which were often worse at night. These findings are consistent with the most commonly published PN symptoms, all of which being considered “typical” sensory symptoms of PNCitation1,Citation60,Citation61.

The observation that the majority of subjects reported significant limitations in their overall QoL and their family relationships confirms that PN not only restricts the physical level, but also represents a significant disease burden on various levels (e.g. emotional, social, professional)Citation8–10. In addition, the journey from experiencing the first PN symptoms to being diagnosed and treated correctly can be extremely long, increasing the burden even further. Subjects in our study reported they had suffered from PN symptoms for approximately 2.3 years before being diagnosed. While only a single article from the 1990s could be identified in the literature that provides an estimate of time to diagnosis between 2 and 77 weeksCitation62, experts believe it may actually take even longer (5 years or more)Citation63.

Our results indicate that—despite having considerable symptoms and impairment in QoL—the vast majority of subjects (82.6%) had not been diagnosed by a physician before inclusion into the study, making PN a silent or almost invisible disease in large parts of the population. This number seems alarmingly high but is unfortunately consistent with published figures from other countriesCitation21–23, confirming the urgent need to educate physicians about the (early) diagnosis of PN. Low disease awareness on the patient side was also confirmed, with 62.9% of subjects having never heard of PN before. Raising awareness of the disease and creating a sense of urgency to seek medical attention will be an important step in improving the diagnosis and treatment of PN.

Almost two-thirds of those subjects who had been diagnosed with PN before participation reported that their general practitioner (GP) diagnosed them. This highlights the key role GPs play in diagnosing PN. In most cases, the GP is the first contact person for a patient when symptoms occur. A referral to a specialist may only be needed in severe cases or to further refine the diagnosis, which explains why only 15.6% saw a specialist after diagnosis. GPs should therefore be further educated and enabled to diagnose PN by using simple tools or asking target-aimed questions rather than referring patients to specialists, which may further delay diagnosis and treatment due to long waiting times.

Although subjects with a previous diagnosis of PN were a minority in this study, the prescription behavior of doctors after establishing the diagnosis was consistent with current treatment guidelines for neuropathic pain and other recommendations on alternative treatmentsCitation64–66. This explains why anticonvulsants were the most commonly prescribed medication, followed by B vitamins. Surprisingly, despite their great burden, the majority of subjects did not use any self-medication in addition to the prescribed medication. This may be due to avoiding additional costs on top of the high cost of prescription medicine, which is usually not reimbursed in Mexico, but also may be due to a lack of knowledge about which product(s) to buy.

Although the study was performed in Mexico, the results may be transferrable to other countries with comparable demographics of the general population and similar prevalence numbers of PN risk factors. For example, current prevalence figures for diabetes in adults in Mexico (17%) are similar to other countries in Latin America (e.g. 11% in Brazil), Europe (e.g. 13% in Portugal), Middle East (e.g. 18% in Saudi Arabia and Egypt), South East Asia (e.g. 11% in Indonesia) and the United States (14%)Citation24. Adults affected by obesity are currently 37% in Mexico, 43% in the United States, and 26% in BrazilCitation67. As prevalence figures for both diabetes and obesity are estimated to continue to rise in the future, the prevalence of PN should be monitored continuously and risk groups should be educated on potential complications. Beyond these similarities, the results on PN symptoms and patient burden may also be transferrable to persons with PN in general as PN symptoms and their impact on QoL are similar across the globe.

Strengths and limitations

The study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this was the first epidemiological study to examine the prevalence of PN in an open population in which enrolled subjects were not preselected in medical units (only as accompanying persons, not patients) or diagnosed with specific types of PN. In addition, the selection of the study location (metropolitan region) allowed the immigrant population from the interior of the country to be taken into account, so that a wide variety of economic, cultural and social backgrounds were covered. In the greater Mexico City area itself, there is no segmentation according to social, cultural, or geographical classes. Additionally, because participants were approached on the street, there was no bias regarding treatments used or disease causes. Furthermore, the prevalence estimate is to be considered fairly accurate since PN status was determined based on a medical examination as part of the study.

One of the limitations was that the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although all government-imposed restrictions in Mexico had been lifted on April 3, 2022, parts of the population—particularly vulnerable individuals—may have self-isolated beyond official restrictions, which may have resulted in an inclusion bias. As participants were recruited in the Mexico City metropolitan area, an urban bias cannot be excluded. Thus, the study population may not be fully representative of the whole Mexican population as it lacks the representation of rural regions. In addition, it is possible that a selection bias (i.e. “healthy volunteer bias”) may have occurred, for example with regard to people with mobility issues who may have less likely been recruited at subway stations and similar public places. However, due to the fact that the targeted age group was 40 to 65 years, the risk of bias due to mobility problems was considered comparably low for the study population in scope. Beyond that, the socio-economic status, education level, and gender balance of the study population was considered similar to the general population in Mexico City, whereas the ethnic background was not investigated as it was not considered relevant in the context of this study.

Different tools and methods exist to diagnose PN; however, until today, there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of PN, which is adding to the issue of underdiagnosis as reflected in the scientific literature. While in this study the MNSI has been chosen as a validated tool to diagnose distal symmetric peripheral neuropathy, which is well-known and established in clinical practice in Mexico, additional tests to confirm the diagnosis (e.g. nerve conduction studies) could have been of value.

In addition, the reporting of comorbidities such as hypertension, depression, hypothyroidism, and risk factors of PN such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and B vitamin deficiencies have been limited to physician and patient reported outcomes. As this was not a primary objective of the study, no laboratory tests or other confirmatory tests have been performed and, hence, results are not presented within this publication. Further epidemiological studies may be needed to investigate comorbidities and potential risk factors of PN in detail.

A certified translation of all study questionnaires into Spanish has been provided by the contract research organization. However, the Spanish version of the questionnaires had not been previously validated. In contrast to the other questionnaires used, the QoL PE Questionnaire was developed specifically for this study and was therefore not previously validated in English neither. Although overall results were available for the entire PN cohort, several questions were answered by fewer subjects. In addition, longer free texts were permitted for some questions which were answered with many ambiguous answers. Those results could only be evaluated in clusters and in some cases to a limited extent. Certainly, validation of the questionnaire or a readability test could have helped to avoid inconsistencies. Another approach could have been electronic data capture to better guide subjects through the questionnaire, enable real-time consistency checks, and reduce the number of unknown or inconclusive answers.

Conclusions

Overall, the study provided unique and highly relevant results that meet the scientific need to close significant data gaps and contribute to a better understanding of the prevalence and impact of PN in the general population. The results confirm for the first time that the prevalence of PN in the general Mexican population is high, while most individuals are undiagnosed and unaware of the disease. The data highlight the urgent need to raise awareness both among HCPs—especially in primary care settings—and communities and to diagnose PN (early). However, further epidemiological studies from other countries may be needed to provide a holistic global picture. This may also allow developing an approach to improve patient care, which includes components such as incorporating PN screening into regular medical examinations for risk groups and establishing training and awareness programs for HCPs and the general population.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The study was conducted by Infinite Clinical Research, S.A. De C.V. Florencia 65, Juárez, Cuauhtémoc, 06600 Ciudad de México, CDMX, Mexico. Medical writing assistance was provided by Dr Julia Dittmann (Dittmann Medical Writing, Hamburg, Germany). The work was funded by Procter and Gamble International Operations S.A.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

CH, DR, and LW are employees and minor shareholders of Procter & Gamble. CH, DR, and LW report no other potential conflicts of interest for this work. JRS and JHSM do not report any potential conflict of interest related to this publication. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

JRS, JHSM, CH, DR, and LW made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download TIFF Image (292.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download TIFF Image (612.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download TIFF Image (836.9 KB)Rodriguez-Saldana_Supplementary_ after resubmission.docx

Download MS Word (596.5 KB)Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Nold CS, Nozaki K. Peripheral neuropathy: clinical pearls for making the diagnosis. JAAPA. 2020;33(1):9–15. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000615460.45150.e0.

- Sommer C, Geber C, Young P, et al. Polyneuropathies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:83–90.

- Watson JC, Dyck PJB. Peripheral neuropathy: a practical approach to diagnosis and symptom management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(7):940–951. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004.

- Callaghan BC, Price RS, Feldman EL. Distal symmetric polyneuropathy: a review. JAMA. 2015;314(20):2172–2181. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13611.

- Jones MR, Urits I, Wolf J, et al. Drug-Induced peripheral neuropathy: a narrative review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2020;15:38–48.

- Landmann G. Diagnostik und therapie der schmerzhaften polyneuropathie. Psychiatr Neurol. 2012;5:13–16.

- Lehmann HC, Wunderlich G, Fink GR, et al. Diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Neurol Res Pract. 2020;2(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s42466-020-00064-2.

- Hakim M, Kurniani N, Pinzon RT, et al. Improvement of quality of life in patients with peripheral neuropathy treated with a fixed dose combination of high-dose vitamin B1, B6 and B12: results from a 12-week prospective non-interventional study in Indonesia. J Clin Trials. 2018;2:1000343.

- Van Acker K, Bouhassira D, De Bacquer D, et al. Prevalence and impact on quality of life of peripheral neuropathy with or without neuropathic pain in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients attending hospital outpatients clinics. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35(3):206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.11.004.

- Riandini T, Wee HL, Khoo EYH, et al. Functional status mediates the association between peripheral neuropathy and health-related quality of life in individuals with diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2018;55(2):155–164. doi: 10.1007/s00592-017-1077-8.

- Yang C-J, Hsu H-Y, Lu C-H, et al. Do we underestimate influences of diabetic mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy on hand functional performance and life quality? J Diabetes Investig. 2018;9(1):179–185. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12649.

- Miranda-Massari JR, Gonzalez MJ, Jimenez FJ, et al. Metabolic correction in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: improving clinical results beyond symptom control. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2011;6:260–273.

- Malik RA, Andag-Silva A, Dejthevaporn C, et al. Diagnosing peripheral neuropathy in South-East Asia: a focus on diabetic neuropathy. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11(5):1097–1103. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13269.

- Hicks CW, Wang D, Daya N, et al. The association of peripheral neuropathy detected by monofilament testing with risk of falls and fractures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(6):1902–1909. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18338.

- Carmichael J, Fadavi H, Ishibashi F, et al. Advances in screening, early diagnosis and accurate staging of diabetic neuropathy. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:671257. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.671257.

- Hakim M, Kurniani N, Pinzon R, et al. A review on prevalence and causes of peripheral neuropathy and treatment of different etiologic subgroups with neurotropic B vitamins. J Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2019;9(4):262. doi: 10.35248/2161-1459.19.9.262.

- Brown JJ, Pribesh SL, Baskette KG, et al. A comparison of screening tools for the early detection of peripheral neuropathy in adults with and without type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:1467213. doi: 10.1155/2017/1467213.

- Malik RA, Aldinc E, Chan S-P, et al. Perceptions of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in South-east asia: results from patient and physician surveys. Adv Ther. 2017;34(6):1426–1437. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0536-5.

- Bongaerts BWC, Rathmann W, Heier M, et al. Older subjects with diabetes and prediabetes are frequently unaware of having distal sensorimotor polyneuropathy: the KORA F4 study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1141–1146. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0744.

- Tesfaye S, Vileikyte L, Rayman G, et al. Painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: consensus recommendations on diagnosis, assessment and management. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27(7):629–638. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1225.

- Ponirakis G, Elhadd T, Chinnaiyan S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic neuropathy and painful diabetic neuropathy in primary and secondary healthcare in Qatar. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12(4):592–600. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13388.

- Ponirakis G, Elhadd T, Chinnaiyan S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for painful diabetic neuropathy in secondary healthcare in Qatar. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(6):1558–1564. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13037.

- Ziegler D, Landgraf R, Lobmann R, et al. Painful and painless neuropathies are distinct and largely undiagnosed entities in subjects participating in an educational initiative (PROTECT study). Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.043.

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 10th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2021.

- Malik RA. Wherefore art thou, O treatment for diabetic neuropathy? Int Rev Neurobiol. 2016;127:287–317. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2016.03.008.

- Hicks CW, Selvin E. Epidemiology of peripheral neuropathy and lower extremity disease in diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(10):86. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1212-8.

- Lim JZM, Burgess J, Ooi CG, et al. The peripheral neuropathy prevalence and characteristics are comparable in people with obesity and long-duration type 1 diabetes. Adv Ther. 2022;39(9):4218–4229. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02208-z.

- Callaghan BC, Gao L, Li Y, et al. Diabetes and obesity are the main metabolic drivers of peripheral neuropathy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(4):397–405. doi: 10.1002/acn3.531.

- Callaghan BC, Xia R, Banerjee M, et al. Metabolic syndrome components are associated with symptomatic polyneuropathy independent of glycemic status. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(5):801–807. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0081.

- World Obesity Federation. World obesity atlas. 2023. [accessed May 2024]. https://data.worldobesity.org/publications?cat=19.

- Cascio MA, Mukhdomi T. Small fiber neuropathy. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Peripheral neuropathy fact sheet. 2018 [accessed 2024 May]. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/peripheral-neuropathy.

- Hicks CW, Wang D, Windham BG, et al. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy defined by monofilament insensitivity in middle-aged and older adults in two US cohorts. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):19159. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98565-w.

- Trivedi S, Pandit A, Ganguly G, et al. Epidemiology of peripheral neuropathy: an Indian perspective. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2017;20(3):173–184. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_470_16.

- Castrejón-Pérez RC, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, et al. Frailty, diabetes, and the convergence of chronic disease in an age-related condition: a population-based nationwide cross-sectional analysis of the mexican nutrition and health survey. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(8):935–941. doi: 10.1007/s40520-017-0852-2.

- Herman WH, Pop-Busui R, Braffett BH, et al. Use of the Michigan neuropathy screening instrument as a measure of distal symmetrical peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes: results from the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications. Diabet Med. 2012;29(7):937–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03644.x.

- Feldman EL, Stevens MJ, Thomas PK, et al. A practical two-step quantitative clinical and electrophysiological assessment for the diagnosis and staging of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 1994;17(11):1281–1289. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.11.1281.

- Bennedsgaard K, Grosen K, Attal N, et al. Neuropathy and pain after breast cancer treatment: a prospective observational study. Scand J Pain. 2023;23(1):49–58. doi: 10.1515/sjpain-2022-0017.

- Dias LS, Nienov OH, Machado FD, et al. Polyneuropathy in severely obese women without diabetes: prevalence and associated factors. Obes Surg. 2019;29(3):953–957. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-03627-0.

- Mete T, Aydin Y, Saka M, et al. Comparison of efficiencies of Michigan neuropathy screening instrument, neurothesiometer, and electromyography for diagnosis of diabetic neuropathy. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:821745–821747. doi: 10.1155/2013/821745.

- Bastyr EJ, Price KL, Bril V. Development and validity testing of the neuropathy total symptom score-6: questionnaire for the study of sensory symptoms of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Clin Ther. 2005;27(8):1278–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.08.002.

- Moors VJ, Graveran KD, Shahsavari D, et al. A cross-sectional study describing peripheral neuropathy in patients with symptoms of gastroparesis: associations with etiology, gastrointestinal symptoms, and gastric emptying. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22(1):315. doi: 10.1186/s12876-022-02372-0.

- Scarpato S, Galassi G, Monti G, et al. Peripheral neuropathy in mixed cryoglobulinaemia: clinical assessment and therapeutic approach. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38:1231–1237.

- Ahmed MA, Muntingh G, Rheeder P. Vitamin B12 deficiency in metformin-treated type-2 diabetes patients, prevalence and association with peripheral neuropathy. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;17(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s40360-016-0088-3.

- Vinik AI, Bril V, Kempler P, et al. Treatment of symptomatic diabetic peripheral neuropathy with the protein kinase C beta-inhibitor ruboxistaurin mesylate during a 1-year, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2005;27(8):1164–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.08.001.

- Ibarra CT, Rocha J de J, Hernández R, et al. Prevalencia de neuropatía periférica en diabéticos tipo 2 en el primer nivel de atención. Rev Med Chil. 2012;140:1126–1131.

- Jiménez Victoria MA. Incidencia de neuropatía diabética con el test de Michigan en la UMF 61. 2015;

- Freeman R, Gonzalez-Duarte A, Barroso F, et al. Cutaneous amyloid is a biomarker in early ATTRv neuropathy and progresses across disease stages. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9(9):1370–1383. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51636.

- Ticse R, Pimentel R, Mazzeti P, et al. Elevada frecuencia de neuropatía periférica en pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 de un hospital general de Lima-Perú. Rev Med Hered. 2013;24(2):114–121. doi: 10.20453/rmh.v24i2.593.

- Ware JEJ, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002.

- García JJG. Muestreo y cálculo de tamaño de muestra. Epidemiol Clnica. 2013:292.

- Lazzarini PA, Hurn SE, Fernando ME, et al. Prevalence of foot disease and risk factors in general inpatient populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e008544. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008544.

- van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, et al. Neuropathic pain in the general population: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain. 2014;155(4):654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013.

- Pradilla Ardila G, Vesga Angarita BE, León-Sarmiento FE. Study of neurological diseases prevalence in Aratoca, a rural area of Eastern Colombia. Rev Med Chil. 2002;130(2):191–199.

- Yovera-Aldana M, Velásquez-Rimachi V, Huerta-Rosario A, et al. Prevalence and incidence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2021;16(5):e0251642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251642.

- Gregg EW, Sorlie P, Paulose-Ram R, et al. Prevalence of lower-extremity disease in the US adult population > =40 years of age with and without diabetes: 1999-2000 national health and nutrition examination survey. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(7):1591–1597. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1591.

- Liu X, Xu Y, An M, et al. The risk factors for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2019;14(2):e0212574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212574.

- Martyn CN, Hughes RA. Epidemiology of peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62(4):310–318. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.4.310.

- Suzuki M. Peripheral neuropathy in the elderly. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;115:803–813. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52902-2.00046-1.

- Nix WA. Muscles, nerves, and pain. Boston: Springer; 2017.

- Boulton AJM, Malik RA, Arezzo JC, et al. Diabetic somatic neuropathies. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1458–1486. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1458.

- Hawke SH, Davies L, Pamphlett R, et al. Vasculitic neuropathy. A clinical and pathological study. Brain. 1991;114(5):2175–2190. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2175.

- Srinivasan A, Paranjothi S, Bhattacharyya K, et al. Consensus recommendation for the management of peripheral neuropathy in India. J Indian Med Assoc. 2018;116:45–55.

- Bril V, England J, Franklin GM, et al. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2011;76(20):1758–1765. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166ebe.

- Head KA. Peripheral neuropathy: pathogenic mechanisms and alternative therapies. Altern Med Rev. 2006;11(4):294–329.

- Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136–154. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2042.

- World Obesity Federation. https://data.worldobesity.org/.