Abstract

Objective: Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a debilitating inflammatory skin condition, often impacting quality of life. International guidelines recommend omalizumab, an anti-immunoglobulin E antibody, for second-line treatment. Our objective was to understand patient characteristics associated with prescription of omalizumab, and assess real-world outcomes in patients with CSU treated with omalizumab.

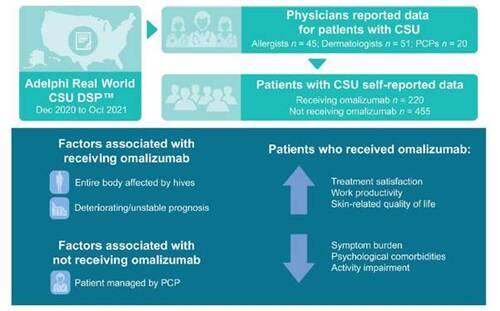

Methods: We analyzed data from the Adelphi Real World CSU Disease Specific Programme™, a cross-sectional survey with retrospective data collection (December 2020–October 2021) from physicians and patients with CSU in the United States.

Results: Data from allergists (n = 45), dermatologists (n = 51), and primary care physicians (PCPs; n = 20) were included. At the time of data collection, one-third of patients were receiving omalizumab (n = 220) and 67% were eligible for but not receiving omalizumab (n = 455). Using logistic regression, the odds of receiving omalizumab were higher in patients whose entire bodies were affected by hives [OR = 2.551; 95% CI 1.502-4.333; p < 0.001] or with deteriorating/unstable prognoses at treatment initiation [OR = 2.219; 95% CI 1.031-4.777; p = 0.042], and lower in patients managed by PCPs [OR = 0.276; 95% CI 0.130-0.584; p < 0.001]. Estimates from an inverse probability weighted regression adjustment model indicated that patients receiving omalizumab had higher treatment satisfaction, improvements in itching, hives, angioedema, insomnia, and anxiety, and lower impact on work productivity, compared with patients not receiving omalizumab.

Conclusion: Around two-thirds of patients with CSU considered eligible for omalizumab were not receiving the guideline-recommended therapy. Patients receiving omalizumab had better real-world outcomes compared with patients not receiving omalizumab. Ensuring patients receive the most appropriate treatment could benefit patients with CSU.

Plain language summary

People with a skin rash known as chronic spontaneous urticaria (also called long-lasting hives) have itchy spots that last longer than 6 weeks. People with long-lasting hives may be treated with a medicine called omalizumab to help their itching. We asked doctors why they gave some people omalizumab. We found that only one out of every three people with long-lasting hives were given omalizumab. Doctors gave some people omalizumab because they had long-lasting hives on their whole body or their hives were getting worse. Other people received omalizumab because they were seeing a specialist doctor (allergist) instead of a primary care physician (also called a general practitioner). When compared with people who received other medicines, people being treated with omalizumab had reduced itching, less anxiety, and better well-being. These findings could help doctors in choosing the right medicine for people with long-lasting hives.

Disclaimer

As a service to authors and researchers we are providing this version of an accepted manuscript (AM). Copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proofs will be undertaken on this manuscript before final publication of the Version of Record (VoR). During production and pre-press, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal relate to these versions also.Introduction

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a debilitating inflammatory skin condition characterized by the development of wheals (hives), angioedema, or both that last for >6 weeks [1]. Patients with CSU often experience impaired quality of life (QoL) and activities of daily living, impacting their social functioning, sleep, exercise, and work productivity [2-7]. In addition, patients may experience feelings of anxiety, self-consciousness, embarrassment, and a lack of control over their lives [5]. These feelings may underlie the range of psychological comorbidities reported in patients with CSU, including anxiety and depression, which can further reduce QoL [8,9].

As CSU is not life threatening, its impact is often underestimated, resulting in underdiagnosis and undertreatment. Delayed diagnosis is a particular problem; in one study of 1037 patients with CSU, patients experienced urticaria symptoms for an average of 3 years before receiving a diagnosis [10]. Patients in this study were undertreated; although 80% had uncontrolled symptoms in the previous 4 weeks, only 40% were currently receiving treatment [10]. Undertreatment was also reported in the prospective, noninterventional AWARE study of 1539 patients with CSU unresponsive to high-dose second-generation H1-antihistamines, with only 58% of patients receiving treatment for CSU at baseline [11].

International guidelines recommend omalizumab, a recombinant, humanized, anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) monoclonal antibody, for “patients with CSU unresponsive to high-dose second-generation H1-antihistamines” [1]. Omalizumab has been shown to positively impact QoL and additional outcomes, such as psychological well-being, in phase 3 [12,13] and real-world studies [5,14-18]. Although most physicians are aware of the clinical guidelines that recommend omalizumab for patients with CSU, research suggests that >20% of physicians deviate from these guidelines [19]. In one study, 42% of patients with CSU unresponsive to high-dose second-generation H1-antihistamines were not escalated to a treatment option such as omalizumab [20], suggesting a missed opportunity for many patients.

The aim of this study was to better understand the patient characteristics associated with prescription of omalizumab and gain insights into real-world outcomes in patients who are treated according to guideline recommendations compared with those who are not (i.e. patients with moderate-to-severe CSU who receive omalizumab vs. patients who are eligible for but do not receive omalizumab), using data from the Adelphi Real World CSU Disease Specific Programme™ (DSP™).

Methods

The Adelphi CSU DSP™

Data were sourced from the Adelphi Real World CSU DSP™ from December 2020 through October 2021. The Adelphi CSU DSP™ is a large cross-sectional survey (with elements of retrospective data collection) of allergists, dermatologists, primary care physicians (PCPs) with special interests in dermatology, and their patients with CSU in the United States (US). The DSP™ methodology has been previously validated and published [21-24]. Briefly, these surveys combine physician- and patient-reported questionnaires to describe patient characteristics, disease burden, and treatment. The survey was performed in full accordance with relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act legislation, and the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association [25-27]. Ethical approval for conducting the DSP™ was obtained from the Western Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board, and patients provided informed consent by ticking a checkbox.

Physicians were identified by local fieldwork agents and were invited to participate if they were actively involved in the management of CSU. All physicians were seeing a monthly minimum of eight patients with CSU. Patients were aged ≥18 years at data collection and had a physician-confirmed diagnosis of CSU; patients participating in clinical trials were excluded. Physicians completed electronic patient record forms (PRFs) for their next eight to ten consecutively consulting patients with CSU. PRFs covered each patient’s management, including clinical characteristics, tests and assessments used, and treatment patterns. Data were collected only once for each patient; physicians provided data on each patient’s condition at the time of data collection, as well as providing retrospective time-stamped data, such as clinical status at diagnosis. Patients for whom a PRF had been completed were invited to voluntarily complete a “pen and paper” self-completion form including patient-reported outcome measures and treatment satisfaction.

Patients were classified according to whether they were currently receiving omalizumab or were eligible for but not currently receiving omalizumab (“not receiving omalizumab”). Patients were considered eligible for omalizumab if they were categorized by their physician as experiencing moderate or severe CSU at the time of the current treatment initiation, based on data availability for this patient group in the literature [28]. Two analyses were conducted; the first analysis utilized a sample of 760 PRFs to identify factors associated with receiving omalizumab, and the second analysis utilized a sample of 675 PRFs to compare real-world outcomes of patients receiving omalizumab vs. not receiving omalizumab.

Physician-reported outcome measures

Patient demographics and characteristics included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, time since CSU diagnosis, time on current treatment, employment status, CSU severity at initiation of current treatment, symptoms at initiation of current treatment, and psychological comorbidities at initiation of current treatment. Physicians assessed CSU severity, including the individual symptoms of itch, hives, angioedema, and insomnia, as mild, moderate, severe, extremely severe, or not present and noted whether patients were experiencing anxiety/distress or depression. In addition, physicians indicated their satisfaction with the current control of the patient’s CSU as: “satisfied and I believe this is the best control that can be realistically achieved for this patient”; “satisfied, but I believe better control can be achieved for this patient”; “not satisfied, but I believe this is the best control that can be realistically achieved for this patient”; or “not satisfied, and I believe better control can be achieved for this patient”.

Patient-reported outcome measures

As part of the patient self-completion form, patients were asked to complete four validated patient-reported outcomes measures: the EQ-5D 5-level version, the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire adapted for patients with CSU, and the Jenkins Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire (JSEQ). The EQ‐5D is a five-dimension questionnaire used to assess QoL: index scores range from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 1 (best imaginable health state) [29]. A US-based value set was used for the ED-5D questionnaire [30]. The DLQI is a 10-question validated QoL questionnaire that assesses the impact of skin conditions and their treatment on patients’ lives [31] across six domains: symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relationships, and treatment. Totals range from 0 to 30 (less to more impairment), and a 5-point change from baseline is considered clinically relevant. The WPAI questionnaire is a six-item questionnaire used to assess impairment in work-related productivity and daily activities due to disease, with higher scores indicating greater impairment and reduced productivity [32]. The WPAI measures the percentage of work time missed, work time impaired, overall work impairment, and impairment in regular activities within the past 7 days. The JSEQ assesses the frequency of sleep disturbance in four categories: trouble falling asleep, waking up several times during the night, having trouble staying asleep, and waking up after the usual amount of sleep feeling tired and worn out [33]. The total JSEQ score ranges from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater sleep disturbance. In addition, patients indicated how satisfied they were with the current control of their CSU as: “satisfied – this is the best result my treatment can achieve”; “satisfied – but I think my treatment could do better”; “not satisfied – but this is the best result my treatment can achieve”; or “not satisfied – I think my treatment can do better”.

Statistical analyses

All data were aggregated, de-identified, and anonymized before receipt by Adelphi Real World. Depending on the type of variable being assessed, descriptive statistics, including numerical outcome variables and categorical outcome variables, were used.

Data were analyzed using logistic regression models and inverse probability weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA) models. Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with current omalizumab treatment, adjusting for other covariates. IPWRA was used to compare real-world outcomes in patients treated with omalizumab (the study group) vs. those who were eligible for but were not currently receiving omalizumab (the control group) and only included patients for whom complete data were available. IPWRA was used to balance prespecified covariates between the study group and the control group using inverse probability weights (inverse of the propensity score). The propensity scores were estimated using a logistic regression model including the variables of age, sex (male vs. female), and BMI; severity of CSU, itching, hives/wheals, angioedema, and insomnia/sleep disturbance at initiation of current treatment; and presence of anxiety or depression at initiation of current treatment. Balance between the study and control groups was assessed by the standardized mean differences (SMDs) of the covariates. An SMD between –0.1 and 0.1 (not inclusive) was indicative of adequate balance. Once balance was met, weighted regression adjustment was performed (using the inverse probability weights), adjusting for time on current treatment. For binary outcomes, logistic regression was used, and for continuous outcomes, linear regression was used. The weighted regression coefficients were then used to calculate the average of each outcome for the “currently receiving omalizumab” and the “not receiving omalizumab” groups. The differences between these averages estimated the treatment effects. p values indicate estimated differences in outcomes between the two cohorts included in the model; a p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using Stata Version 17 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Physician and patient characteristics

A total of 116 physicians across the US (45 allergists, 51 dermatologists, and 20 PCPs) participated. Physicians completed a total of 1082 PRFs (414 by allergists, 466 by dermatologists, and 202 by PCPs). Of these, 760 PRFs were included in the analysis of factors associated with receiving omalizumab. Overall, 675 patients were included in the real-world outcomes analysis, of whom one-third of patients (220/675, 33%) were receiving omalizumab and 67% were eligible for but were not receiving omalizumab (455/675) (Table 1). Of the 675 patients, 191 (28%) had completed a self-completion form. Mean age was 43.7 years for patients receiving omalizumab and 39.0 years for patients not receiving omalizumab, and most patients in both groups were female (Table 1). For patients receiving omalizumab (n = 220), 5% (12/220) received 150 mg every 2 weeks, 45% (100/220) received 150 mg every 4 weeks, <1% (2/220) received 300 mg every 2 weeks, 43% (95/220) received 300 mg every 4 weeks, and 5% (11/220) were on another dosing regimen. At initiation of current treatment, CSU was assessed as severe in 44.5% of patients receiving omalizumab and in 19.3% of patients not receiving omalizumab. The proportion of patients with severe or extremely severe itching, hives/wheals, angioedema, and insomnia was higher among patients who received omalizumab than among those who did not.

Factors associated with receiving current omalizumab

By logistic regression, several physician-reported factors were significantly associated with receiving current omalizumab treatment (Figure 1). A patient’s entire body being affected by hives (odds ratio [OR] = 2.551; 95% CI 1.502-4.333; p < 0.001) and/or a deteriorating/unstable prognosis at the time of omalizumab initiation (OR = 2.219; 95% CI 1.031-4.777; p = 0.042) were both associated with receiving current omalizumab treatment. Patients who were managed by a PCP (OR = 0.276; 95% CI 0.130-0.584; p < 0.001) were less likely to be receiving current omalizumab treatment. Directional (but not statistically significant, p > 0.05) associations were also observed (Figure 1); for example, patients receiving omalizumab were more likely to have visible body areas affected, the presence of angioedema, severe itching, and severe overall CSU at the time of omalizumab initiation and less likely to be managed by a dermatologist.

Real-world outcomes

The mean proportion of patients receiving and not receiving omalizumab who experienced improvements in real-world outcomes, including CSU symptoms and QoL, was estimated using IPWRA models.

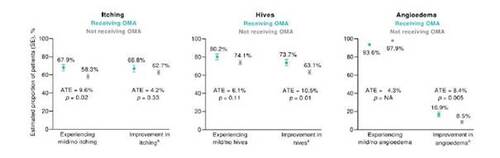

Physician-reported CSU symptoms

In general, the estimated proportion of patients with mild or no CSU symptoms at the time of the survey and with improvements in itching, hives, or angioedema since initiating the current treatment was higher in patients receiving omalizumab (Figure 2). A significantly higher proportion of patients receiving omalizumab vs. not receiving omalizumab had mild or no itching (p = 0.02), improvement in hives since initiation of current treatment (p = 0.01), or improvement in angioedema (p = 0.005).

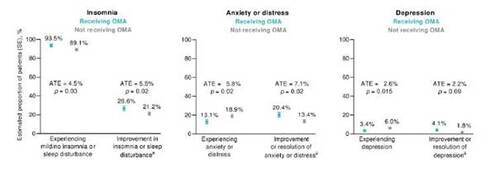

Physician-reported psychological outcomes

A larger estimated proportion of patients with CSU treated with omalizumab experienced improvements in insomnia/sleep disturbance and anxiety/distress compared with patients not receiving omalizumab (Figure 3; p < 0.05). Patients with CSU treated with omalizumab were also less likely to experience depression compared with patients not receiving omalizumab (Figure 3; p = 0.015). However, no statistical difference in improvement or resolution of depression was observed between groups (p = 0.09).

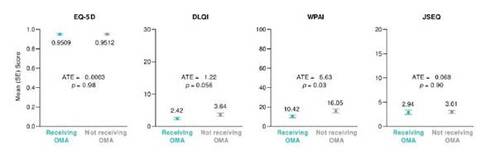

Patient-reported QoL

Patients receiving omalizumab had similar estimated overall QoL (EQ-5D) and sleep disturbance (JSEQ) as patients not receiving omalizumab (Figure 4). The impact of CSU on work productivity and activity was significantly lower in patients receiving omalizumab vs. those not receiving omalizumab, as indicated by lower mean estimated WPAI scores (p < 0.05). The estimated impact of CSU on skin-related QoL (DLQI) appeared lower in patients receiving omalizumab vs. those not receiving omalizumab, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.056).

Physician and patient satisfaction with treatment

A higher estimated proportion of physicians were satisfied with treatment and believed the best control had been achieved for patients receiving omalizumab compared with patients not receiving omalizumab (71.7% vs. 55.7%; average treatment effect = 16.0%; p < 0.0001). Overall, an estimated 85% of patients receiving omalizumab and 65% of patients not receiving omalizumab reported being satisfied with treatment and felt the best control had been achieved.

Discussion

This real-world analysis of patients with CSU found that although all patients were eligible for omalizumab treatment according to their physician-assessed disease severity status, only one-third of patients were receiving omalizumab at the time of the survey. In our analysis, patients were more likely to receive omalizumab if their entire body was affected by hives or if they had deteriorating or unstable prognosis at the time of treatment initiation, and patients who were not receiving omalizumab were more likely to have moderate CSU and a lower symptom burden. Interestingly, patients were less likely to receive omalizumab if they were managed by a PCP. Overall, physicians appear to be selecting appropriate patients for omalizumab using the international guideline recommendations [1]. However, given that two-thirds of eligible patients were not receiving omalizumab, there is a missed opportunity for many suitable patients with CSU to benefit from omalizumab.

The IPWRA model indicated that a larger estimated proportion of patients with CSU currently receiving omalizumab reported being satisfied with their treatment and experienced improvements in CSU symptoms as well as insomnia and anxiety comorbidities, although this may be partly reflective of their capacity to improve with treatment. Patients currently receiving omalizumab also reported lower impact on work productivity and lower activity impairment compared with patients not receiving omalizumab, which aligns with previous studies [5,12,13,34]. In the pivotal phase 3 studies, patients with moderate-to-severe CSU treated with omalizumab experienced significant improvements in CSU symptoms and QoL compared with placebo [12,13]. Improvements have also been seen in patients with CSU and angioedema: in the phase 3 X-ACT study, patients receiving omalizumab reported significant improvements in angioedema- and skin-related QoL and symptoms of depression compared with placebo [14]. In noncomparative real-world studies, patients receiving omalizumab experienced improvements in CSU symptoms, skin-related QoL, work productivity, activity, sleep, perceived stress, anxiety and depression, perceived loss of control, embarrassment, and self-consciousness [5,15-18]. Overall, our findings suggest that patients with moderate-to-severe CSU using omalizumab experience beneficial outcomes compared with patients who did not receive omalizumab.

Our findings are strengthened by the IPWRA model, which adjusts for potential confounders and represents a pragmatic approach to analyzing this type of data, and by most patients receiving omalizumab every 4 weeks at either 150 mg or 300 mg in line with international guidelines. However, there are several limitations to our analysis: participating patients may not reflect the general global CSU population as the DSP™ only includes patients based in the United States who are consulting with their physicians (patients who consult more frequently may possibly have a higher likelihood of being included); the DSP™ is based on a pseudo-random sample of physicians or patients (minimal inclusion criteria governed the selection of participating physicians and participation was influenced by their willingness to complete the survey); recall and selection biases, both common limitations of surveys, might also have affected responses of physicians and patients (but physicians had the ability to refer to the patients’ records while completing the PRF and were asked to provide data for a consecutive series of eligible patients, thus minimizing the possibility of recall and selection biases); patient eligibility was based on the judgment of the respondent physician and not on a formalized diagnostic checklist (but is representative of the physician’s real-world classification of their patients); baseline serum IgE data (a potential predictor of response to omalizumab) was not collected due to the nature of the survey; and the cross-sectional design of this survey prevented any conclusions about causal relationships (although identification of significant associations was possible). Of note, the omalizumab eligibility criteria used in the analysis may be different to the recommendations set out in the international guidelines [1], as full treatment history was not available in the DSP for all patients. We selected patients with moderate-to-severe CSU as a proxy for the omalizumab-eligible cohort, based on data availability from phase 3 omalizumab studies [28]. Despite these limitations, real-world analyses provide important insights that can complement findings from clinical trials [24] and may also address some of the shortcomings of clinical trials, such as limited external validity when applied to more general patient populations [35]. Importantly, real-world analyses provide insight into the effectiveness of treatments when used in routine clinical practice.

Conclusions

Our analysis found that patients with CSU receiving omalizumab showed greater improvements in disease symptoms, psychological comorbidities, and QoL outcomes compared with patients not receiving omalizumab. However, around two-thirds of patients with CSU considered to be eligible for omalizumab treatment were not receiving the guideline-recommended therapy. Although this analysis provides insight into the factors associated with omalizumab use and adds to the growing body of evidence demonstrating improvements in outcomes for patients with CSU receiving omalizumab, further research is needed to understand why physicians do not always follow guideline recommendations. Given omalizumab use was lower in patients managed by PCPs, additional physician education may be beneficial, including consideration of referral to an allergist. Ultimately, ensuring patients receive the most appropriate treatment may benefit all patients with moderate-to-severe CSU.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The analysis described here used data from the Adelphi Real World CSU DSP™, a wholly owned Adelphi Real World product, of which Genentech, Inc., a member of the Roche Group, is one of multiple subscribers. Genentech, Inc. did not influence the original survey through contribution to the design of questionnaires or data collection. Genentech, Inc. was involved in the analysis design, data interpretation, and preparation of the manuscript. Publication of survey results was not contingent on the subscriber’s approval or censorship of the publication.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AS and MH are employees of and stockholders in Genentech, Inc. JH, AK, and PS are employees of Adelphi Real World. JAB and TBC are consultants and speaker bureau members for Genentech, Inc. and consultants for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Natalie Roberts, MSc, and Nilisha Fernando, PhD, of Envision Pharma Group and was funded by Genentech, Inc., a member of the Roche Group. Envision Pharma Group’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022). The data in this manuscript have been presented in part at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting and the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 2022 Annual Meeting.

Author contributions

AS, MH, JH, AK, and PS designed the analysis. All authors interpreted the results, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final draft.

Table 1. Patient characteristics at the time of the survey.

Figure 1. Factors associated with receiving omalizumab (OMA; n = 760; n = 242 receiving OMA; n = 518 not receiving OMA) were identified by logistic regression (odds ratios [OR] and 95% confidence intervals [CI] are presented). An OR >1 indicates that the factor is associated with receiving OMA, whereas an OR <1 indicates that the factor is not associated with receiving OMA. With the exception of age and number of symptoms present, all other ORs are defined in comparison to a reference group: physician specialty general practitioner (GP)/primary care physician (PCP) or dermatologist (compared with allergist); experiencing a symptomatic period (compared with not experiencing a symptomatic period; male (compared with female); experiencing depression (compared with no depression); experiencing anxiety/distress (compared with no anxiety/distress); severe/extremely severe insomnia (compared with none/mild/moderate insomnia); intense hives (>50 hives/24 hours) (compared with none/mild/moderate hives [≤50 hives/24 hours]); visible areas affected, including hands/fingers, face, head, and neck (compared with no visible areas affected); severe/extremely severe itch (compared with none/mild/moderate itch); experiencing an angioedema episode (compared with not experiencing an angioedema episode); experiencing severe chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU; compared with moderate CSU); deteriorating/unstable progression of CSU (compared with improving/stable progression); and entire body affected by hives/itching (compared with not entire body). All patients were physician-categorized as having moderate or severe CSU at the time of current treatment initiation. *p < 0.05 receiving OMA vs. not receiving OMA.

![Figure 1. Factors associated with receiving omalizumab (OMA; n = 760; n = 242 receiving OMA; n = 518 not receiving OMA) were identified by logistic regression (odds ratios [OR] and 95% confidence intervals [CI] are presented). An OR >1 indicates that the factor is associated with receiving OMA, whereas an OR <1 indicates that the factor is not associated with receiving OMA. With the exception of age and number of symptoms present, all other ORs are defined in comparison to a reference group: physician specialty general practitioner (GP)/primary care physician (PCP) or dermatologist (compared with allergist); experiencing a symptomatic period (compared with not experiencing a symptomatic period; male (compared with female); experiencing depression (compared with no depression); experiencing anxiety/distress (compared with no anxiety/distress); severe/extremely severe insomnia (compared with none/mild/moderate insomnia); intense hives (>50 hives/24 hours) (compared with none/mild/moderate hives [≤50 hives/24 hours]); visible areas affected, including hands/fingers, face, head, and neck (compared with no visible areas affected); severe/extremely severe itch (compared with none/mild/moderate itch); experiencing an angioedema episode (compared with not experiencing an angioedema episode); experiencing severe chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU; compared with moderate CSU); deteriorating/unstable progression of CSU (compared with improving/stable progression); and entire body affected by hives/itching (compared with not entire body). All patients were physician-categorized as having moderate or severe CSU at the time of current treatment initiation. *p < 0.05 receiving OMA vs. not receiving OMA.](/cms/asset/622979e2-5e62-4692-ba9a-9b9669c7da7a/icmo_a_2354534_f0001.jpg)

Figure 2. Physician-reported symptoms in patients receiving and not receiving omalizumab (OMA), as estimated using an inverse probability weighted regression adjustment model (n = 675; n = 220 receiving OMA; n = 455 not receiving OMA). aSince initiation of current treatment. ATE, average treatment effect; NA, not available; SE, standard error.

Figure 3. Sleep and psychological outcomes in patients receiving and not receiving omalizumab (OMA), as estimated using an inverse probability weighted regression adjustment model (n = 675; n = 220 receiving OMA; n = 455 not receiving OMA). aSince initiation of current treatment. ATE, average treatment effect; SE, standard error.

Figure 4. Patient-reported quality of life outcomes in patients receiving and not receiving omalizumab (OMA), as estimated using an inverse probability weighted regression adjustment model (n = 188; n = 60 receiving OMA; n = 128 not receiving OMA). ATE, average treatment effect; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; JSEQ, Jenkins Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire; SE, standard error; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment.

References

- Zuberbier T, Abdul Latiff AH, Abuzakouk M, et al. The international EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2022;77:734-766. doi: 10.1111/all.15090.

- Maurer M, Abuzakouk M, Berard F, et al. The burden of chronic spontaneous urticaria is substantial: Real-world evidence from ASSURE-CSU. Allergy. 2017;72:2005-2016. doi: 10.1111/all.13209.

- Sanchez-Borges M, Ansotegui IJ, Baiardini I, et al. The challenges of chronic urticaria part 1: Epidemiology, immunopathogenesis, comorbidities, quality of life, and management. World Allergy Organ J. 2021;14:100533. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2021.100533.

- Staubach P, Eckhardt-Henn A, Dechene M, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic urticaria is differentially impaired and determined by psychiatric comorbidity. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:294-298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06976.x.

- Porter E, Tierney E, Byrne B, et al. 'It has given me my life back': a qualitative study exploring the lived experience of patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria on omalizumab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2032-2034. doi: 10.1111/ced.15321.

- Hoskin B, Ortiz B, Paknis B, et al. Humanistic Burden of Refractory and Nonrefractory Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria: A Real-world Study in the United States. Clin Ther. 2019;41:205-220. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.12.004.

- Hoskin B, Ortiz B, Paknis B, et al. Exploring the real-world profile of refractory and non-refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria in the USA: clinical burden and healthcare resource use. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:1387-1395. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1586222.

- Engin B, Uguz F, Yilmaz E, et al. The levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:36-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02324.x.

- Staubach P, Dechene M, Metz M, et al. High prevalence of mental disorders and emotional distress in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:557-561. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1109.

- Wagner N, Zink A, Hell K, et al. Patients with Chronic Urticaria Remain Largely Undertreated: Results from the DERMLINE Online Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1027-1039. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00537-5.

- Maurer M, Staubach P, Raap U, et al. H1-antihistamine-refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: it's worse than we thought - first results of the multicenter real-life AWARE study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47:684-692. doi: 10.1111/cea.12900.

- Kaplan A, Ledford D, Ashby M, et al. Omalizumab in patients with symptomatic chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria despite standard combination therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:101-109. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.013.

- Maurer M, Rosen K, Hsieh HJ, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:924-935. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215372.

- Staubach P, Metz M, Chapman-Rothe N, et al. Omalizumab rapidly improves angioedema-related quality of life in adult patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: X-ACT study data. Allergy. 2018;73:576-584. doi: 10.1111/all.13339.

- Salman A, Demir G, Bekiroglu N. The impact of omalizumab on quality of life and its predictors in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: Real-life data. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12975. doi: 10.1111/dth.12975.

- Diluvio L, Piccolo A, Marasco F, et al. Improving of psychological status and inflammatory biomarkers during omalizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria. Future Sci OA. 2020;6:FSO618. doi: 10.2144/fsoa-2020-0087.

- Patella V, Zunno R, Florio G, et al. Omalizumab improves perceived stress, anxiety, and depression in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1402-1404. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.026.

- Casale TB, Murphy TR, Holden M, et al. Impact of omalizumab on patient-reported outcomes in chronic idiopathic urticaria: Results from a randomized study (XTEND-CIU). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2487-2490 e2481. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.04.020.

- Kolkhir P, Pogorelov D, Darlenski R, et al. Management of chronic spontaneous urticaria: a worldwide perspective. World Allergy Organ J. 2018;11:14. doi: 10.1186/s40413-018-0193-4.

- Maurer M, Costa C, Gimenez Arnau A, et al. Antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria remains undertreated: 2-year data from the AWARE study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50:1166-1175. doi: 10.1111/cea.13716.

- Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, et al. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: Disease-Specific Programmes - a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3063-3072. doi: 10.1185/03007990802457040.

- Babineaux SM, Curtis B, Holbrook T, et al. Evidence for validity of a national physician and patient-reported, cross-sectional survey in China and UK: the Disease Specific Programme. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010352. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010352.

- Higgins V, Piercy J, Roughley A, et al. Trends in medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term view of real-world treatment between 2000 and 2015. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:371-380. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S120101.

- Anderson P, Higgins V, Courcy Jd, et al. Real-world evidence generation from patients, their caregivers and physicians supporting clinical, regulatory and guideline decisions: an update on Disease Specific Programmes. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2023:1-9. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2023.2279679.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule [internet]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/index.html [last revised May 2003; accessed July 2023] 2003.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act 2009 [internet]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/hitech-act-enforcement-interim-final-rule/index.html [last revised June 2017; accessed July 2023] 2009.

- European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association. Code of Conduct. Available at: https://www.ephmra.org/code-conduct-aer. [last revised September 2023; accessed December 2023].

- Giménez-Arnau AM. Omalizumab for treating chronic spontaneous urticaria: an expert review on efficacy and safety. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17:375-385. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2017.1285903.

- Devlin N, Parkin D, Janssen B. Methods for analysing and reporting EQ-5D data. Springer Nature; 2020.

- Pickard AS, Law EH, Jiang R, et al. United States Valuation of EQ-5D-5L Health States Using an International Protocol. Value in Health. 2019;22:931-941. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.02.009.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006.

- Jenkins CD, Stanton BA, Niemcryk SJ, et al. A scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:313-321. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90138-2.

- Akdas E, Adisen E, Oztas MO, et al. Real-life clinical practice with omalizumab in 134 patients with refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: a single-center experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:240-242. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2022.06.003.

- Saunders C, Byrne CD, Guthrie B, et al. External validity of randomized controlled trials of glycaemic control and vascular disease: how representative are participants? Diabet Med. 2013;30:300-308. doi: 10.1111/dme.12047.