Abstract

Objectives: Anxiety and depression symptoms are more common in patients with spondyloarthritis (SpA) than in the general population. This study describes prognostic factors for change in self-reported anxiety and depression over 2 years in a well-defined SpA cohort.

Method: In 2009, 3716 adult patients from the SpAScania cohort received a postal questionnaire to assess quality of life (QoL) and physical and mental functioning. A follow-up survey was performed in 2011. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale indicated ‘no’, ‘possible’, and ‘probable’ cases of anxiety and depression. Transitions between the three different categories were analysed and logistic regression analysis determined prognostic factors (patient-reported outcomes and characteristics) for improvement or deterioration.

Results: In total, 1629 SpA patients responded to both surveys (44%) (mean ± SD age 55.8 ± 13.1 years, disease duration 14.6 ± 11.7 years); 27% had ankylosing spondylitis, 55% psoriatic arthritis, and 18% undifferentiated SpA. The proportion of patients reporting possible/probable anxiety decreased from 31% to 25% over 2 years, while no changes in depression were seen. Factors associated with deterioration or improvement were largely the same for anxiety as for depression: fatigue, general health, QoL, level of functioning, disease activity, and self-efficacy. However, reporting chronic widespread pain (CWP) at baseline increased the risk of becoming depressed and decreased the probability of recovering from anxiety.

Conclusion: Self-reported anxiety and depression is common and fairly stable over time in SpA patients. The association between mental health and CWP indicates that both comorbidities need to be acknowledged and treated in the clinic.

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is an inflammatory rheumatic disease which includes the following subtypes: ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), inflammatory arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (Aa-IBD), and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis (USpA) (Citation1). In Europe, the overall prevalence of SpA has been reported to be in the range of 0.3–1.9% (Citation2–Citation7). Despite recent pharmacological improvements and their effectiveness in targeting disease activity and pain in SpA, a considerable proportion of patients face the consequences of SpA in everyday life (Citation8, Citation9). Clinically diagnosed anxiety and clinical depression in rheumatic diseases has about twice the prevalence seen in the general population and the causes of anxiety and depression appear to be multifactorial. Among other factors, disease severity, physical disability, experiencing helplessness, and educational level may be associated with anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatic diseases (Citation10, Citation11). Studies that focus on diagnostic SpA subtypes point in the same direction for AS (Citation12–Citation15) and PsA (Citation16–Citation18), while studies regarding USpA and mental health are rare. A recent population-based cohort study showed a 60% increase in the risk of developing a depressive disorder among AS patients compared to the general population (Citation19). Anxiety and/or depression may cause a decreased level of physical activity and decreased compliance with therapy, which can lead to worsening of disease and poorer health outcomes. Possible depressive disorders need to be acknowledged and treated accordingly to improve general health and quality of life (QoL). In clinical practice it is important to know which SpA patients are susceptible to developing depressive and anxiety disorders, e.g. by means of a self-reported questionnaire or other screening tools. This enables clinicians to prevent the onset of depressive disorders/anxiety or to recognize and start treatment (non-pharmacological or pharmacological) for depressive disorders and anxiety promptly. Nevertheless, little is known about the determinants for change over time in self-reported anxiety and depression in a well-defined cohort of SpA patients. Therefore, this study aims to identify which variables are related to improvement or deterioration in self-reported anxiety and depression over a 2 year follow-up period in patients from the SpAScania cohort, a cohort of adults from one region in Sweden (Skåne) with an established diagnosis of SpA.

Method

Study design and subjects

This longitudinal study on patients identified by the Skåne Healthcare Register (SHR) was based on two postal surveys in the southernmost region of Sweden in 2009 and 2011. The SHR includes all healthcare visits. It is linked to a unique personal identification number (PIN) and provides information about the healthcare provider, date of visit, and diagnosis code according to the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (Citation4, Citation20). The SHR covers one-eighth of the Swedish population (Citation14, Citation19, Citation20). More details on the SHR have been published in previous articles (Citation4, Citation20–Citation23).

All subjects who had received an ICD-10 code diagnosis of the SpA subtypes AS, PsA, or USpA (in this study including both cases of USpA and Aa-IBD) at any time during five calendar years (2003–2007) were identified. The diagnosis was required to be registered at least once by a rheumatologist or specialist in internal medicine, or on at least two separate occasions by any other physician in primary or secondary care. Healthcare-seeking individuals with ICD-10 codes of SpA identified by the register (n = 3711) received a mailed questionnaire in 2009. The follow-up questionnaire in 2011 was sent to all subjects identified in 2009 if they had not declined participation in the study. More details on the surveys have been published elsewhere (Citation4, Citation20–Citation23).

Questionnaire

The baseline and follow-up questionnaire booklet contained validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to structurally evaluate QoL as well as physical and mental functioning. To improve face and content validity, the composite questionnaire was tested in three focus groups including a total of 20 patients with different SpA subtypes. This procedure resulted in minor corrections to improve understanding.

Reminders were sent out on two separate occasions within a 2 month period.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics such as age, gender, and ICD-10 diagnosis were collected from the SHR at baseline. Marital status, employment, living status, disease duration, and educational level were self-reported information.

Anxiety and depression

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) subscale Anxiety (HADS-A) and the HADS subscale Depression (HADS-D) were included in the questionnaire (http://www.scalesandmeasures.net/files/files/HADS.pdf). This self-report scale was originally designed to detect depressive and anxiety symptoms in hospital outpatients, and contains 14 questions (four-point Likert scale 0–3 points), seven on anxiety and seven on depression (Citation24). The final score ranges from 0 to 21 points for each subscale, and a higher score means the presence of increased anxiety or depressive symptoms. For both anxiety and depression, HADS scores ranging from 0 to 8 indicate ‘no case’, from 8 to 11 ‘possible cases’, and from 11 to 21 ‘probable cases’ of anxiety or depression (Citation24).

Disease activity and physical functioning

The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) (Citation25) consists of six questions on pain and stiffness. The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) (Citation26) includes 10 questions on physical function. The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis (BAS) indices were collected together with general health and fatigue measured with numeric rating scales (NRSs). In the BAS indices as well as in the fatigue and pain scales, the total score ranged between 0 and 10 (best to worst). The BAS indices are primarily validated for patients with AS, but studies have also supported good to moderate validity in patients with non-radiographic axial SpA (USpA) and PsA with axial symptoms (Citation27, Citation28).

Health-related QoL

The EuroQol 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) is a generic measure assessing health-related QoL in five dimensions including mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The five three-point Likert questions on the EQ-5D yield a summary score ranging from 0 (no health) to 1 (full health) (Citation29). In the absence of a Swedish tariff for calculating the utility of the EQ-5D, the tariff from the UK was used.

Pain distribution

Chronic pain was assessed by a question on persistent or regularly recurrent pain for more than 3 months in the musculoskeletal system. The location and distribution of pain were reported using a drawing of the body with predefined regions (Citation30). Each region was also described by name, and pain was reported by ticking appropriate boxes next to the descriptions.

The pain model is used to distinguish between no chronic pain, regionally chronic pain, and widespread chronic pain, according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for chronic pain (Citation31).

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was measured using the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (ASES; http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/research/searthritis.pdf) (Citation32, Citation33). The ASES is a self-administered questionnaire that measures the domains of handling pain (five items) and handling other symptoms (six items), originally developed for arthritis patients. Each item is scored on a 10–100 NRS (10-point intervals, worst–best). Pain and Symptom domain scores are obtained by calculating the mean score (10–100, worst–best) for the five, respectively six, items within the domain, resulting in domain scores between 10 and 100, with higher scores representing better self-efficacy skills.

Statistical analysis

Differences in PROMs and sociodemographics

Differences between paired responders in 2009 and 2011 were analysed using the paired t test for numerical data, McNemar’s test for dichotomous data, and chi-squared test for categorical data. Descriptive data are presented as mean ± SD and a value of p < 0.05 was considered the criterion for statistical significance.

HADS scores and transitions between HADS classes over a 2 year period

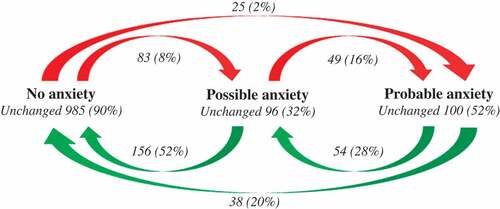

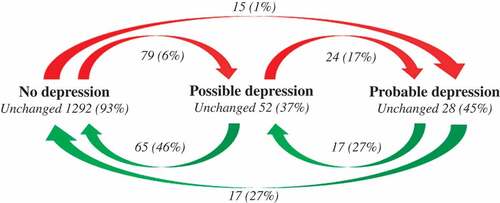

A visual transition scheme described the transitions from 2009 to 2011 in the three HADS-A and HADS-D classes (0–8 ‘no case’, 8–11 ‘possible case’, and 11–21 ‘probable case’) within each individual patient in the SpAScania cohort.

Association between changes in HADS and sociodemographics or PROMs

Univariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine which sociodemographics or PROMs were associated with improvement or deterioration on the HADS-A subscale. Subsequently, the same analyses were performed for HADS-D.

Associations between the transition in HADS categories from 2009 to 2011 were analysed as either improvement (defined as 0 = stable probable/possible disease vs 1 = improving patients from possible or probable disease to non-disease based on HADS) or deterioration in the HADS (defined as 0 = stable non-disease vs 1 = deteriorating patients from non-disease to possible or probable disease based on HADS), as dependent variables. Independent variables were sociodemographics or PROMs at baseline determined by univariate logistic regression analyses.

Results were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All analyses were performed using SPSS v. 22 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics and consent

The Regional Ethical Review Board at Lund University, Sweden, approved the study (301/2007, 406/2008). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki 2013 (Citation34). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Results

In 2009, a total of 2851 out of 3711 patients (76%) responded to the study invitation, of whom 684 (18%) declined participation and 2167 (58%) returned the questionnaire. The analysis of responders versus non-responders in 2009 (Citation21) showed that higher age was significantly associated with a higher response in men. Women’s tendency to respond increased slightly with age as well, except for the subtype AS, where the tendency to respond decreased with age. At the 2011 follow-up survey, 13 patients had died or relocated and 525 patients declined participation or did not respond to the survey and its two reminders. In total, 1629 patients responded to both surveys.

In this cohort of 1629 SpA patients, 434 (27%) had AS, 888 (55%) had PsA, and 307 (18%) had undifferentiated SpA. Statistical differences (marital status, living and employment status, fatigue, general health, and BASFI) between the responders in 2009 and 2011 are shown in . The percentage of cases with self-reported possible and probable anxiety decreased from 31% in 2009 to 25% in 2011 (n = 498 vs n = 411). No change was found for patients with self-reported depression between 2009 and 2011 ().

Table 1. Sociodemographics and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for the spondyloarthritis patients in the 2009 and 2011 cohorts (n = 1629).

Transitions between HADS categories over time

A valid total HADS-A score at both time-points could be calculated for 1586 (97%) of the 1629 responders. Transitions between the three HADS-A categories (no anxiety, possible anxiety, or probable anxiety) over the 2 year follow-up period showed that a total of 248 (16%) patients improved, 157 (10%) deteriorated, and 1181 (74%) remained stable in 2011 compared with 2009 ().

Figure 1. Self-reported anxiety: transitions between the three Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale subscale Anxiety (HADS-A) classes (class I: 0–8 ‘no case’; class II: 8–11 ‘possible case’; and class III: 11–21 ‘probable case’ of anxiety) over a 2 year follow-up period of all patients in the SpAScania cohort who responded to both the 2009 and 2011 questionnaires and had a valid HADS-A score at both time-points (n = 1586).

A valid total HADS-D score at both time-points could be calculated for 1589 (98%) of the 1629 responders. Transitions between the three HADS-D categories (no depression, possible depression, or probable depression) over the 2 year follow-up period showed that a total of 118 (7%) patients improved, 99 (6%) deteriorated, and 1402 (87%) remained stable in 2011 compared with 2009 ().

Figure 2. Self-reported depression: transitions between the three Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale subscale Depression (HADS-D) classes (class I: 0–8 ‘no case’; class II: 8–11 ‘possible case’; and class III: 11–21 ‘probable case’ of depression) over a 2 year follow-up period of all patients in the SpAScania cohort who responded to both the 2009 and 2011 questionnaires and had a valid HADS-D score at both time-points (n = 1589).

Prognostic factors for improvement and deterioration in HADS

Prognostic factors were largely the same for both improvement and deterioration in anxiety scores as well as in depression scores. Patients who improved from possible or probable to no anxiety/depression had better baseline scores in fatigue (anxiety OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.65, 0.83; depression OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46, 0.84), general health (anxiety OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.64, 0.82; depression OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.59, 0.94), EQ-5D (anxiety OR 10.86, 95% CI 4.55, 25.92; depression OR 12.73, 95% CI 2.91, 55.8), BASFI (anxiety OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.72, 0.88; depression OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66, 0.96), BASDAI (anxiety OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.65, 0.83; depression OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46, 0.84), ASES Pain (anxiety OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02, 1.05; depression OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01, 1.08), and ASES Symptom (anxiety OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.04, 1.07; depression OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.05, 1.14). An improvement in anxiety scores to no anxiety was also found in patients who had lower baseline scores on the HADS-D (anxiety OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.17, 0.83) and in patients who did not report chronic widespread pain (CWP) ().

Table 2. Logistic regression analysis of stable disease vs improving to non-disease based on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) as the dependent variable and all independent variables entered separately in the model.

Studying factors relating to a deterioration in anxiety and depression scores, patients with worse baseline scores in Fatigue (anxiety OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.06, 1.23; depression OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15, 1.36), general health (anxiety OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.65, 0.83; depression OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46, 0.84), EQ-5D (anxiety OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.052, 0.26; depression OR 0.10, 95% CI 0.048, 0.22), BASFI (anxiety OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.045, 1.22; depression OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.13, 1.33), BASDAI (anxiety OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02, 1.29; depression OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.16, 1.48), ASES Pain (anxiety OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.98, 1.00; depression OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97, 0.99), ASES Symptom (anxiety OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.96, 0.98; depression OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.95, 0.98), and HADS–other more often deteriorated from no anxiety/depression to possible or probable anxiety/depression (anxiety OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.15, 1.31; depression OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.12, 1.25). In addition, patients with CWP (depression OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.32, 4.25) at baseline had a higher risk of deteriorating from no depression to possible or probable depression at follow-up 2 years later ().

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of stable non-disease vs deteriorating to possible or probable disease based on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) as the dependent variable and all independent variables entered separately in the model.

Discussion

This study structurally describes the course of anxiety and depression over a 2 year period in a well-defined Swedish cohort of SpA patients. The study shows that self-reported anxiety occurs in three out of 10 patients and self-reported depression in one out of 10 patients with SpA, without a clear difference among the subtypes. Self-reported anxiety cases appear to change more over time compared to depression cases. Analysis of transitions between HADS classes revealed that anxiety is indeed a more dynamic concept than the concept of depression, since fewer transitions are seen within depression between ‘no case’, ‘possible case’, and ‘probable case’ classes in the direction of either deterioration or improvement. Furthermore, both deterioration and improvement in self-reported anxiety/depression appeared to be multifactorial. The factors that were associated with deterioration and improvement were largely the same for anxiety as for depression. Moreover, having CWP at baseline increased the risk of becoming depressed but also decreased the possibility of recovering from anxiety.

We and others have previously found that reports of anxiety and depression are common in patients with SpA (Citation12–Citation18, Citation35). It is also well known that patients with SpA often report high levels of fatigue, low general health, poor QoL, impaired function, and decreased self-efficacy, which all are known factors of importance for reports of anxiety and depression (Citation12–Citation15, Citation17, Citation36).

What this study adds is the importance of acknowledging CWP in patients with SpA. We found that CWP was of importance for having possible or probable anxiety/depression.

The prevalence of CWP in SpA has not been well studied, although a few studies have explored fibromyalgia in AS, in which CWP is an important component, and a prevalence of 10–15% has been reported (Citation37–Citation39). In other chronic rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis one-third of all patients reported CWP (Citation40), compared with a prevalence of 11% in the adult population, being more common in women (Citation30). The association between CWP and depression is well known in many chronic diseases and our findings, together with earlier findings, support the view that both comorbidities need to be acknowledged and treated in the rheumatology clinic in patients with a diagnosis of SpA.

The use of self-reported questionnaires to better understand patients’ perception is endorsed by, among others, the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) (Citation41) and the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology group (OMERACT) (Citation42).

These ASAS recommendations do not yet include pain distribution, more often including pain intensity, nor do they recommend the acknowledgement of psychological issues in their core sets (Citation43). The HADS is commonly used to study anxiety and depression, and a recent study using psychiatrist-conducted semi-structured interviews found that both HADS-A and HADS-D were able to discriminate between patients with and without current depressive/anxiety disorders, supporting the use of HADS in patients with SpA. The cut-off of 7/8 in HADS-D yielded a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 79% for depressive disorders, while the cut-off 6/7 in HADS-A yielded a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 74% for anxiety disorders (Citation44). However, recommendations vary, as do the diseases in which the HADS is used to screen for mental problems. A meta-analysis recommended a lower cut-off point of 5 for HADS-D, reaching a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 50%, and a cut-off of 7 or 8 on the HADS-A, with a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 65% (Citation45). In our study, we applied a cut-off of 8 to define possible anxiety/depression based on suggestions from validation studies by the original authors (Citation24). More studies are needed to confirm the best cut-off point for the two HADS subscales to further validate the use of self-reported instruments in clinical practice to identify patients at higher risk of developing reduced mental health.

Several factors were found to be associated with a transition between HADS categories for anxiety and depression. The factors influencing both an improvement and a deterioration were almost the same, and are already well known to be interlinked with anxiety and depression. None of the age, gender, or SpA subgroups was associated with a transition between the states, whereas self-efficacy was. Findings from patients with rheumatoid arthritis suggest that a sense of coherence is important for improvement in psychological distress (Citation46). This is in accordance with our study, where a better score on self-efficacy at baseline was associated with a better outcome in both anxiety and depression.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, no data regarding the use of antidepressants or other adjuvant therapies to treat either anxiety or depression in our cohort were available. In the larger SpAScania cohort, self-reports of pharmacological treatment for the rheumatic disease were recorded in 2009 and 45% of all subjects with a diagnosis of SpA were treated with tumour necrosis factor (TNF), disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, and corticosteroids (solely or in combination). TNF therapy may have a positive effect on depressive disorders (Citation47), but we did not have any information on change in pharmacological treatment or whether a mental disorder was diagnosed and registered in the medical records. However, the percentage of SpA patients with possible anxiety (25%) and depressive disorders (14%) in our study is higher than that found by Chan et al., based on interviews (16% vs 11%) (Citation44). Also, in the adult Portuguese population with a mix of musculoskeletal diseases, 17% and 8% reported anxiety or depression, respectively, using a cut-off point of 11 (Citation7), which is somewhat higher than our findings in 2009 of probable anxiety (12%) () or depression (4%) (). Secondly, the pain model does not distinguish between different origins of pain; it includes all musculoskeletal pain registered by the patient. Enthesitis status and information concerning joint involvement could contribute to better understanding of the different pain patterns.

A third limitation of the study is that the focus of the current manuscript is on transitions in mental states due to the SpA diagnosis. Therefore, the analysis of non-responders and partial responders is limited and a selection bias is present which may lead to an underestimation of self-reported anxiety and/or depression, if one hypothesizes that having anxiety and/or depression limits the willingness to complete a survey.

Fourthly, the data were collected in 2009 and 2011. The growing use of anti-TNF since then has had a favourable effect on clinical symptoms, and consequently on self-reported anxiety and/or depression on baseline as well as 2 year follow-up. Furthermore, today one could expect less anxiety and depression, especially among recently diagnosed patients. Because the use of anti-TNF was already changing between 2009 and 2011, the effects of data age on change in self-reported anxiety and depression are more complex.

Conclusion

In this large population-based study, we found that self-reported anxiety and depression are common and fairly stable over time. The factors that were associated with deterioration or improvement were largely the same for anxiety as for depression and closely related to general health status (i.e. fatigue, general health, health-related QoL, functional capacity, disease activity, and self-efficacy). However, having CWP at baseline not only increased the risk of becoming depressed but also decreased the possibility of recovering from anxiety. The association between anxiety/depression and CWP found in this study, together with earlier findings, supports the view that both mental health status and CWP need to be acknowledged and treated in the rheumatology clinic in patients with a diagnosis of SpA.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the staff at Epi-centre Skåne for their skilful help. This study was funded by Region Skåne and with research grants from the Faculty of Medicine at Lund University, Sweden, the Norrbacka-Eugenia Foundation, Sweden, and the Swedish Rheumatism Association. The follow-up survey was funded by Abbvie and Pfizer.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Khan MA, Braun J. Concepts and epidemiology of spondyloarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006;20:401–17.

- Andrianakos A, Trontzas P, Christoyannis F, Dantis P, Voudouris C, Georgountzos A, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in Greece: a cross-sectional population based epidemiological study. The ESORDIG Study. J Rheumatol 2003;30:1589–601.

- Braun J, Bollow M, Remlinger G, Eggens U, Rudwaleit M, Distler A, et al. Prevalence of spondylarthropathies in HLA-B27 positive and negative blood donors. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:58–67.

- Haglund E, Bremander AB, Petersson IF, Strombeck B, Bergman S, Jacobsson LT, et al. Prevalence of spondyloarthritis and its subtypes in southern Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:943–8.

- Roux CH, Saraux A, Le Bihan E, Fardellone P, Guggenbuhl P, Fautrel B, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathies: geographical variations in prevalence in France. J Rheumatol 2007;34:117–22.

- Saraux A, Guillemin F, Guggenbuhl P, Roux CH, Fardellone P, Le Bihan E, et al. Prevalence of spondyloarthropathies in France: 2001. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1431–5.

- Branco JC, Rodrigues AM, Gouveia N, Eusebio M, Ramiro S, Machado PM, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases and their impact on health-related quality of life, physical function and mental health in Portugal: results from EpiReumaPt- a national health survey. RMD Open 2016;2:e000166.

- Dagfinrud H, Kjeken I, Mowinckel P, Hagen KB, Kvien TK. Impact of functional impairment in ankylosing spondylitis: impairment, activity limitation, and participation restrictions. J Rheumatol 2005;32:516–23.

- van Echteld I, Cieza A, Boonen A, Stucki G, Zochling J, Braun J, et al. Identification of the most common problems by patients with ankylosing spondylitis using the international classification of functioning, disability and health. J Rheumatol 2006;33:2475–83.

- Geenen R, Newman S, Bossema ER, Vriezekolk JE, Boelen PA. Psychological interventions for patients with rheumatic diseases and anxiety or depression. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2012;26:305–19.

- Kilic G, Kilic E, Ozgocmen S. Relationship between psychiatric status, self-reported outcome measures, and clinical parameters in axial spondyloarthritis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e337.

- Baysal O, Durmus B, Ersoy Y, Altay Z, Senel K, Nas K, et al. Relationship between psychological status and disease activity and quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int 2011;31:795–800.

- Durmus D, Sarisoy G, Alayli G, Kesmen H, Cetin E, Bilgici A, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in ankylosing spondylitis: their relationship with disease activity, functional capacity, pain and fatigue. Compr Psychiatry 2015;62:170–7.

- Hakkou J, Rostom S, Aissaoui N, Berrada KR, Abouqal R, Bahiri R, et al. Psychological status in Moroccan patients with ankylosing spondylitis and its relationships with disease parameters and quality of life. J Clin Rheumatol 2011;17:424–8.

- Martindale J, Smith J, Sutton CJ, Grennan D, Goodacre L, Goodacre JA. Disease and psychological status in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:1288–93.

- Husted JA, Tom BD, Farewell VT, Gladman DD. Longitudinal study of the bidirectional association between pain and depressive symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:758–65.

- Khraishi M, MacDonald D, Rampakakis E, Vaillancourt J, Sampalis JS. Prevalence of patient-reported comorbidities in early and established psoriatic arthritis cohorts. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:877–85.

- Ogdie A, Schwartzman S, Husni ME. Recognizing and managing comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015;27:118–26.

- Meesters JJ, Bremander A, Bergman S, Petersson IF, Turkiewicz A, Englund M. The risk for depression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:418.

- Englund M, Joud A, Geborek P, Felson DT, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF. Prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in southern Sweden 2008 and their relation to prescribed biologics. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1563–9.

- Haglund E, Bergman S, Petersson IF, Jacobsson LT, Strombeck B, Bremander A. Differences in physical activity patterns in patients with spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1886–94.

- Haglund E, Bremander A, Bergman S, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF. Work productivity in a population-based cohort of patients with spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1708–14.

- Haglund E, Petersson IF, Bremander A, Bergman S. Predictors of presenteeism and activity impairment outside work in patients with spondyloarthritis. J Occup Rehabil 2015;25:288–95.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70.

- Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91.

- Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, Kennedy LG, O’Hea J, Mallorie P, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2281–5.

- Eder L, Chandran V, Pellett F, Pollock R, Shanmugarajah S, Rosen CF, et al. IL13 gene polymorphism is a marker for psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1594–8.

- Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, Listing J, Marker-Hermann E, Zeidler H, et al. The early disease stage in axial spondylarthritis: results from the German spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:717–27.

- Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53–72.

- Bergman S, Herrstrom P, Hogstrom K, Petersson IF, Svensson B, Jacobsson LT. Chronic musculoskeletal pain, prevalence rates, and sociodemographic associations in a Swedish population study. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1369–77.

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the multicenter criteria committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:160–72.

- Lomi C, Nordholm LA. Validation of a Swedish version of the arthritis self-efficacy scale. Scand J Rheumatol 1992;21:231–7.

- Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, Shoor S, Holman HR. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:37–44.

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4.

- Shen CC, Hu LY, Yang AC, Kuo BI, Chiang YY, Tsai SJ. Risk of psychiatric disorders following ankylosing spondylitis: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. J Rheumatol 2016;43:625–31.

- Brionez TF, Assassi S, Reveille JD, Learch TJ, Diekman L, Ward MM, et al. Psychological correlates of self-reported functional limitation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R182.

- Haliloglu S, Carlioglu A, Akdeniz D, Karaaslan Y, Kosar A. Fibromyalgia in patients with other rheumatic diseases: prevalence and relationship with disease activity. Rheumatol Int 2014;34:1275–80.

- Azevedo VF, Paiva Edos S, Felippe LR, Moreira RA. Occurrence of fibromyalgia in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rev Bras Reumatol 2010;50:646–50.

- Salaffi F, De Angelis R, Carotti M, Gutierrez M, Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F. Fibromyalgia in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: epidemiological profile and effect on measures of disease activity. Rheumatol Int 2014;34:1103–10.

- Andersson ML, Svensson B, Bergman S. Chronic widespread pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the relation between pain and disease activity measures over the first 5 years. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1977–85.

- Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. The assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68(Suppl 2):ii1–44.

- Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d’Agostino MA, et al. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:745–53.

- Escorpizo R, Boers M, Stucki G, Boonen A. Examining the similarities and differences of OMERACT core sets using the ICF: first step towards an improved domain specification and development of an item pool to measure functioning and health. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1739–44.

- Chan CY, Tsang HH, Lau CS, Chung HY. Prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders and validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale as a screening tool in axial spondyloarthritis patients. Int J Rheum Dis 2017;20:317–25.

- Vodermaier A, Millman RD. Accuracy of the hospital anxiety and depression scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1899–908.

- Goulia P, Voulgari PV, Tsifetaki N, Andreoulakis E, Drosos AA, Carvalho AF, et al. Sense of coherence and self-sacrificing defense style as predictors of psychological distress and quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: a 5-year prospective study. Rheumatol Int 2015;35:691–700.

- Arisoy O, Bes C, Cifci C, Sercan M, Soy M. The effect of TNF-alpha blockers on psychometric measures in ankylosing spondylitis patients: a preliminary observation. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:1855–64.