Abstract

Objectives

Inflammatory joint diseases (IJDs) substantially affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL). We aimed to compare HRQoL between patients with gout, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and ankylosing spondylitis (AS): (i) overall; (ii) stratified by sex; and (iii) between women and men with the same IJD diagnosis.

Method

A survey including the RAND36-Item Health Survey for assessing HRQoL was sent to patients with a diagnosis of gout, PsA, RA, or AS, registered at a rheumatology clinic or primary care centre during 2015–2017. HRQoL was compared across IJDs. Because of age differences between diagnoses, age-matched analyses were performed.

Results

In total, 2896/5130 (56.5%) individuals responded to the questionnaire. Of these, 868 had gout, 699 PsA, 742 RA, and 587 AS. Physical component summary (PCS) scores were more affected than mental component summary (MCS) scores for all diagnoses (PCS range: 39.7–41.2; MCS range: 43.7–48.9). Patients with gout reported better PCS scores than patients with PsA, RA, and AS, who reported similar scores in age-matched analysis. MCS scores were close to normative values for the general population and similar across IJDs. When comparing women and men with respective IJDs, women reported worse PCS (range, all IJDs: 34.5–37.4 vs 37.5–42.5) and MCS (PsA: 44.0 vs 46.8; RA: 46.1 vs 48.7) scores.

Conclusion

We found that patients with gout reported better PCS scores than patients with other IJDs, for whom the results were similar. Women reported overall worse PCS and MCS scores than men.

Gout, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are the most common inflammatory joint diseases (IJDs). Gout is the most prevalent IJD, typically affecting more men than women (Citation1) and usually diagnosed around 60–70 years of age (Citation2). The disease usually presents with attacks of monoarticular arthritis in a peripheral joint, most commonly in the foot, with intercritical periods of various length. PsA typically develops in up to 30% of psoriasis patients (Citation3). PsA has an even gender distribution, with a peak incidence around 50–59 years of age (Citation4). PsA involves the peripheral joints and entheses and, in some cases, the axial skeleton (Citation3). RA is the most studied IJD and is characterized by symmetric polyarticular synovitis, systemic inflammation, and often the presence of autoantibodies (Citation5). In RA there is a female predominance. The median age of diagnosis is around 60 years of age (Citation6). AS is more common in men and is characterized by inflammation in the spine and sacroiliac joints, resulting in inflammatory back pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility (Citation7). In a Swedish study, around 95% of AS patients had symptom onset before the age of 45 years (Citation8). Similarly to other chronic diseases, IJDs substantially affect the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (Citation9–15). This is likely to be due to both the IJD itself and associated comorbidities, which have been shown to negatively affect HRQoL in gout, PsA, RA, and AS (Citation12, Citation16). We have previously shown that patients with gout report more cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, compared with patients with PsA, RA, and AS (Citation17). HRQoL is often described as how well the individual functions in his or her life and the perceived well-being in social, physical, and mental domains of health (Citation18). It is often affected by disease or treatment. The most widely used instrument for measuring HRQoL is the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), which is available in different languages for commercial use. The SF-36 covers eight different domains, reflecting physical and mental domains (Citation19). The RAND-36 is a licence-free alternative to the SF-36, which includes the same items. A Swedish study showed that the Swedish RAND-36 is reliable (Citation20), and similar results for the summary scores have been reported for the SF-36 and RAND-36 (Citation21). The SF-36 has been shown to be valid in gout (Citation22), PsA (Citation23), RA (Citation15, Citation24), and AS (Citation14). Previous studies have found significantly lower HRQoL in gout (Citation16), PsA (Citation12, Citation25), RA (Citation10, Citation12, Citation15), and AS (Citation10, Citation14, Citation26) compared with controls, the general population, or reference values for patients without IJDs. To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing HRQoL in these four IJDs in the same setting. Our aims were to compare HRQoL between patients with gout, PsA, RA, and AS: (i) overall, (ii) stratified by sex, and (iii) between women and men with the same IJD diagnosis.

Method

Setting

The study was set in Western Sweden, where we performed a questionnaire study.

Study population

Individuals ≥ 18 years and with at least one International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis for gout, PsA, RA, or AS, recorded at a healthcare visit to a physician at any of three rheumatology clinics (for all patients) or at any of 12 primary care centres (for gout patients) during January 2015 through February 2017 were identified. The primary care centres are different in terms of urban/rural location and number of registered patients. Ninety-one per cent of patients with gout were recruited from primary care centres. For PsA and RA, all available patients were retrieved from the hospital clinics diagnosis register; for each diagnosis, a sample with a predefined sex distribution of 50% women and 50% men was randomly selected for the present survey. This sex distribution was chosen to facilitate analyses across diagnoses by age and sex. For AS, all available patients were selected from the hospital clinics diagnosis register. All of the selected patients with gout (n = 1589), PsA (n = 1200), RA (n = 1246), and AS (n = 1095) were sent a questionnaire. A reminder survey was sent to those who did not reply to the initial questionnaire. Recruitment of patients and non-responder data are further described in . The IJD diagnoses used in this study have previously been validated in primary care [gout (Citation27)] and secondary care [PsA (Citation28), RA (Citation29), and AS (Citation8)]. Returning the questionnaire was considered informed consent and all participants were informed in writing that the reported data would be published. The Regional Ethic Review board in Gothenburg, Sweden, approved the study (23 August 2016, Dnr 519-16). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1. Selection site and demographic characteristics of responders and non-responders according to inflammatory joint disease diagnosis.

Definition of variables

The questionnaire included questions on demographics, comorbidities, and, for non-gout patients, current treatment with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which were grouped into either conventional synthetic (cs) or biologic (b) DMARDs. Use of antidepressants [Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code N06A)] was also assessed. For all patients, we collected information on numeric rating scales (NRSs) (0–10), with a score of 10 being most severe, for global health, pain, and fatigue. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (Citation30) (total score ranging from 0 to 3.0, with 0 indicating no impairment and 3 indicating complete impairment) was also collected, as well as HRQoL using the RAND-36 (https://www.rand.org/pubs/reprints/RP971.html). A comorbidity score (range 0–6) was created, where one point was given to each self-reported diagnosis of diabetes, myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer, kidney disease, and lung disease. Highest completed education was assessed and divided into ≤ 12 years (which in Sweden includes 9 years of elementary school and 3 years of high school education) or > 12 years. In patients with AS, we collected the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) (Citation31) and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) (Citation32), which have total scores ranging from 0 to 10 points, with a higher score being worse (Citation31, Citation32). In patients with PsA, we collected the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), with a total score ranging from 0 to 30, where 0 indicates no effect on quality of life (Citation33).

RAND-36

The RAND-36, containing 36 items, is divided into eight domains; physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), social functioning (SF), role emotional (RE), mental health (MH), vitality (VT), bodily pain (BP), and general health (GH). The different domains and the component summary scores range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating a better health status. The physical and mental component summary (PCS and MCS) scores reflect the individual subscales well, and using PCS and MCS has the advantage of reducing the number of statistical tests and reducing the role of chance when drawing statistical conclusions (Citation34). Higher scores on PCS and MCS represent better health, but the scales are slightly different compared to the subscales. Normal values, standardized to the Swedish SF-36 normative population, for PCS and MCS are (mean ± sd) 50 ± 10, where a value below 50 represents worse health status than the general population. Values for SF-36 domains from the SF-36 Swedish normative population (n = 8930) from 1991 to 1992, consisting of 48.2% men, age range 15–93 years, mean age 42.7 years, have previously been published (Citation35). The mean ± SD values for SF-36 domains were as follows: PF 87.9 ± 19.6, RP 83.2 ± 31.8, BP 74.8 ± 26.1, GH 75.8 ± 22.2, VT 68.8 ± 22.8, SF 88.6 ± 20.3, RE 85.7 ± 29.2, and MH 80.9 ± 18.9. According to recommendations, we chose to report the subscale scores together with the summary scores (Citation36).

Statistics

The mean and standard deviation (sd) were presented for continuous data. Frequencies and percentages were presented for categorical data. The independent samples t-test was used for comparisons of mean values for continuous variables. For comparisons of mean values across multiple groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. For comparing distributions of categorical data, the chi-squared test was used. Owing to differences in age among the four groups of IJD, age and sex matching (1:1:1:1) across individuals with each IJD diagnosis was performed. Age was matched on ± 2 years. Raw scores for individual RAND-36 subscales were calculated, recalibrated, summed, and transformed to 0–100 scales, where 0 represented the worst health and 100 the best health, using standard guidelines (Citation19).

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS version 9.4 were used for statistical analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Characteristics of the responders are shown in . In total, there were 2896/5130 (56.5%) individuals who responded to the questionnaire. Of these, 868 patients had gout (mean age 71.3 years, 79.6% men), 699 had PsA (mean age 56.6 years, 46.9% men), 742 had RA (mean age 66.8 years, 47.8% men), and 587 had AS (mean age 51.1 years, 56.4% men). The response rates were 54.6% in gout, 58.3% in PsA, 59.6% in RA, and 53.6% in AS. Non-responders were younger than responders for all diagnoses (p < 0.01). (Non-responders are further described in and Supplementary Table S1.) As seen in , there were marked differences in sex and age distributions between the different diagnoses, despite our effort to balance the sex ratio for RA (see Method). Patients with gout were significantly older (p < 0.001), were more frequently men (p < 0.001), and reported more comorbidities compared with the other IJDs, as previously published (Citation17). To be living alone was less common in AS, whereas the proportions were similar between the other IJDs. Among patients with PsA, RA, and AS, 22–36% reported current treatment with bDMARDs and more than half of the patients with PsA and RA reported current treatment with csDMARDs. Some sociodemographic differences between genders were noted; educational level was lower in male (but not female) RA versus gout patients, alcohol consumption was higher in male (but not female) gout patients, and use of antidepressants was more frequent in female (but not male) PsA patients. The NRS ratings for global health, pain, and fatigue, and HAQ scores were more favourable in patients with gout (overall as well as in women and men separately) compared with the other IJDs. DMARD users were younger and reported better PCS scores but similar MCS scores compared to non-DMARD users (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2. Characteristics of the survey population (n = 2896), stratified by inflammatory joint disease diagnosis.

Table 3. Characteristics of the survey population, women (n = 1191), stratified by inflammatory joint disease diagnosis.

Table 4. Characteristics of the survey population, men (n = 1705), stratified by inflammatory joint disease diagnosis.

RAND-36 scores across diagnoses

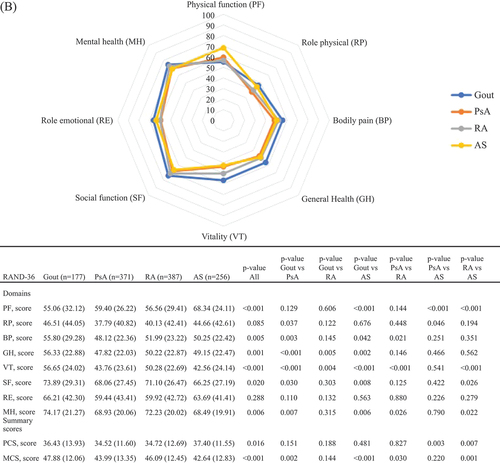

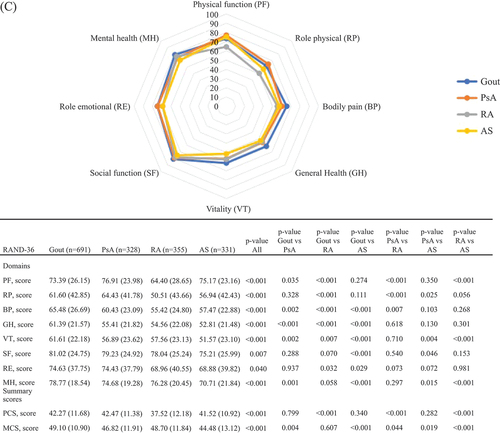

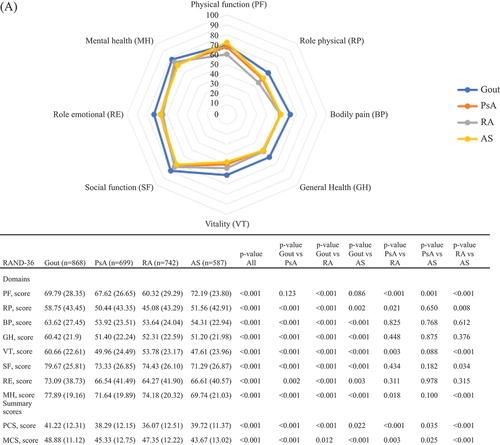

In the entire study population as well as in women and men separately (), physical HRQoL, represented by PCS scores, was poorer than mental HRQoL, represented by MCS scores. This pattern was similar for all IJDs. In , RAND-36 values are presented stratified by IJD diagnosis and by sex. Patients with gout reported better PCS and somewhat better MCS scores compared with the other IJDs. Patients with RA reported the worst PCS scores overall and stratified by sex (except in women, where PsA and RA had similar scores), whereas for MCS, patients with AS reported the worst scores, overall and stratified by sex.

Figure 1. The RAND 36-Item Health Survey scores for inflammatory joint disease diagnoses: (A) overall (n = 2896); (B) in women (n = 1191); and (C) in men (n = 1705). Comparisons across diagnoses are assessed by independent t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Values are shown as mean (sd) or number of patients. PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; PF, physical functioning; RP, role physical; BP, bodily pain; GH, general health; VT, vitality; SF, social functioning; RE, role emotional; MH, mental health; PCS, physical component summary; MCS, mental component summary.

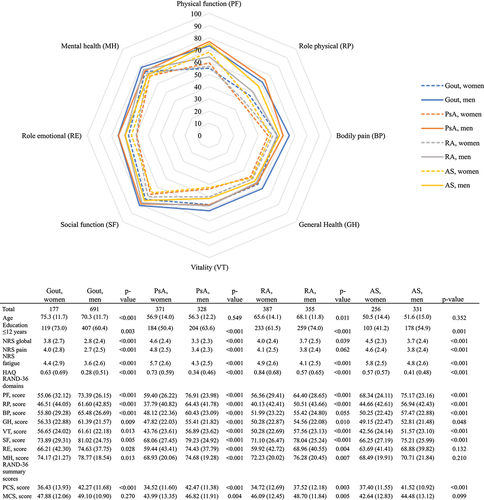

RAND-36, NRS, and HAQ scores between women and men

When comparing women and men with a particular IJD diagnosis, worse scores for PCS were noted for women compared with men for all IJDs (). For MCS scores, women also scored lower than men (PsA and RA). Women also reported significantly worse NRS scores for global health, pain, and fatigue, compared with men for all IJDs, except for NRS scores for pain in RA, where the difference was non-significant. HAQ scores were worse in women compared with men in all IJDs.

Figure 2. Comparison of the RAND 36-Item Health Survey scores between women (n = 1191) and men (n = 1705), stratified by inflammatory joint disease diagnosis. Comparisons between women and men are assessed by independent samples t-test or chi-squared test. Values are shown as mean (sd) or number of patients (%). PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; NRS, numeric rating scale; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; PF, physical functioning; RP, role physical; BP, bodily pain; GH, general health; VT, vitality; SF, social functioning; RE, role emotional; MH, mental health; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary.

Age-matched RAND-36, NRS, and HAQ scores

Overall results regarding differences between IJD and sex were similar in analyses matching for age differences between groups (Supplementary Table S3a–c). PCS was more affected than MCS (overall, as well as in women and men separately) in all IJDs. Better scores for PCS in patients with gout compared with the other IJDs, overall and stratified by sex, remained in age-matched analyses. MCS scores were similar between IJDs, except for gout reporting more favourable MCS scores compared with AS overall, but not when stratified by sex. HAQ and NRS scores (global health, pain, and fatigue) were also better in gout compared with the other IJDs.

Discussion

In this questionnaire study assessing HRQoL, measured by RAND-36, in gout, PsA, RA, and AS, we found that HRQoL was more impaired in physical domains than in mental domains, across all IJDs overall and stratified by sex. Furthermore, patients with gout reported better scores for HRQoL, HAQ, and NRS global health, pain, and fatigue, compared with the other IJDs both with and without age matching, whereas HRQoL, HAQ, and NRS scores for global health, pain, and fatigue were more similar across PsA and AS, although RA patients had slightly worse scores compared with PsA and AS. Women reported worse HRQoL compared with men across all IJDs.

RAND-36 scores compared between IJDs

Although the SF-36 has been shown to be valid in gout (Citation22), the episodic nature of the disease may not be captured by this survey, since it assesses HRQoL during the last 4 weeks, which could be one reason for the better RAND-36 scores reported in the patients with gout. We observed that patients with RA reported worse PCS scores than patients with PsA and AS before age matching, but the differences disappeared after age matching, suggesting that this was largely an effect of higher age in RA patients. Previous studies comparing PCS and MCS in different IJDs have shown conflicting results; furthermore, the treatment of many IJDs has dramatically improved during the past few decades, highlighting the importance of up-to-date data, such as in the present study, on HRQoL. Some studies have reported better PCS scores in AS compared with RA (Citation10, Citation37), whereas a review study stated similar reductions in HRQoL among patients with AS and RA (Citation26). Salaffi et al found worse PCS scores in RA compared with PsA and AS, although their analyses were not age matched (Citation12). A small study by Sokoll and Helliwell from 2001, assessing HRQoL in 47 PsA patients and 47 RA patients, matched for disease duration, showed no significant difference in HRQoL in PsA versus RA (Citation38). In a larger study by Husted et al, similar MCS scores, but better PCS scores, were reported when comparing 107 PsA patients and 43 RA patients (Citation39). We found PCS to be more affected in all IJDs compared with MCS, in both crude analyses and analyses on age-matched samples in both women and men. In line with our study, previous studies have shown that PCS was more affected than MCS in PsA (Citation12), AS (Citation12, Citation40), RA (Citation12), and gout (Citation41). In age-matched samples, MCS scores were similar in PsA and RA (see Supplementary Table S3a–c), which may be surprising given the frequent psychological problems reported by patients with psoriasis (Citation42); however, patients with RA may also suffer emotional problems and fatigue that can cause reduced MCS, even early in the disease (Citation43). In gout, a systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2021 found an association between gout and anxiety and depression (Citation44). In our study, women with PsA reported significantly higher use of antidepressants compared with those with other IJDs. MCS scores showed small reductions that were frequently close to the normative value of 50 and are likely to be of minor clinical importance. It is, however, important to note the extent to which IJDs can affect mental health.

Sex-based differences in RAND-36 scores in IJDs

We observed a difference in HRQoL by sex, with women scoring worse than men on both PCS and MCS for all IJDs. Previous studies have shown that women with AS (Citation40) and RA (Citation15) tend to report lower values on MCS compared with men. In AS, men and women have reported similar scores (Citation40), as well as worse scores in women in physical domains (Citation45). In a systematic review, female sex was associated with better PCS scores but worse MCS scores in patients with RA (Citation15). Explanatory factors for these sex differences could include both the observed worse scoring in women for patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and HAQ, as well as differences in disease phenotypes between sexes. In a study on early RA patients, women reported more disabilities, reflected by worse HAQ scores after 8 years of follow-up compared with men despite similar HAQ values at baseline (Citation46). In addition to worse HAQ scores, women with RA frequently reported higher levels of pain compared with men with RA (Citation47). It should also be noted that in a study of the general population in Sweden (n = 8930), women reported worse HRQoL compared with men (Citation48), indicating a general phenomenon rather than a consequence of disease. This overall tendency for women to score worse on various PROMs and HRQoL could have several explanations, including differences in biology, culture, and societal settings.

Limitations

There are some weaknesses of this study which should be addressed. First, differences in age and sex may have hampered comparisons between diagnoses, although we actively recruited a larger proportion of men with RA. We also stratified analyses by sex and performed comparisons both without taking age into account and using age-matched samples. Secondly, differences in age and sex between responders and non-responders, and between the different IJDs, may affect the generalization of results to other populations. Thirdly, diagnostic misclassification may be present, although validation studies performed in Sweden on gout in primary care (Citation27), and on PsA (Citation28), RA (Citation29), and AS (Citation8) in secondary care, have shown high validity. Fourthly, the study would have benefited from having a control group without IJD.

Strengths

Strengths of our study are the comparison of HRQoL in four IJDs in the same geographical setting and including gout in the comparisons of HRQoL between IJDs, which has not been done before.

Conclusion

For all IJDs, PCS was more affected than MCS. Patients with gout scored better on PCS compared with those with PsA, RA, and AS. MCS was somewhat better in patients with gout compared with those with other IJDs, who had more similar scores. Women scored worse than men on PCS (all IJDs) and MCS (PsA and RA) scores. These overall observed differences in HRQoL between IJDs and sexes are important to be aware of when evaluating changes over time, setting treatment goals, and evaluating the effect of therapy in the IJDs.

Authors’ contributions

AL, MD, and EK had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors conceived and designed the study. All authors obtained the funding and acquired the data. AL, MD, and EK analysed the data. AL, MD, and EK interpreted the data. All authors drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the final version of the manuscript for important intellectual content. MD, EK, and LJ supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was granted from the Ethical Review Board of Gothenburg, Sweden. Replying to the questionnaire was considered informed consent.

Availability of data and material

The data analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (39.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the patients who participated in the study. We also want to thank Tatiana Zverkova Sandström for statistical guidance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03009742.2022.2157962

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dehlin M, Drivelegka P, Sigurdardottir V, Svard A, Jacobsson LT. Incidence and prevalence of gout in western Sweden. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:164.

- Drivelegka P, Sigurdardottir V, Svard A, Jacobsson LTH, Dehlin M. Comorbidity in gout at the time of first diagnosis: sex differences that may have implications for dosing of urate lowering therapy. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:108.

- Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:957–70.

- Exarchou S, Giuseppe D, Alenius G, Klingberg E, Sigurdardottir V, Wedrén S, et al. The national incidence of clinically diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in Sweden 2014-2016. [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73(Suppl 9).

- Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2010;376:1094–108.

- Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: a review. JAMA 2018;320:1360–72.

- Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet 2007;369:1379–90.

- Lindstrom U, Exarchou S, Sigurdardottir V, Sundstrom B, Askling J, Eriksson JK, et al. Validity of ankylosing spondylitis and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis diagnoses in the Swedish national patient register. Scand J Rheumatol 2015;44:369–76.

- Chen HH, Chen DY, Chen YM, Lai KL. Health-related quality of life and utility: comparison of ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus patients in Taiwan. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:133–42.

- Ovayolu N, Ovayolu O, Karadag G. Health-related quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis, fibromyalgia syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison with a selected sample of healthy individuals. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:655–64.

- Gudu T, Gossec L. Quality of life in psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2018;14:405–17.

- Salaffi F, Carotti M, Gasparini S, Intorcia M, Grassi W. The health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with a selected sample of healthy people. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:25.

- Bavière W, Deprez X, Houvenagel E, Philippe P, Deken V, Flipo RM, et al. Association between comorbidities and quality of life in psoriatic arthritis: results from a multicentric cross-sectional study. J Rheumatol 2019;47:369–76.

- Yang X, Fan D, Xia Q, Wang M, Zhang X, Li X, et al. The health-related quality of life of ankylosing spondylitis patients assessed by SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res 2016;25:2711–23.

- Matcham F, Scott IC, Rayner L, Hotopf M, Kingsley GH, Norton S, et al. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;44:123–30.

- Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. Is gout associated with reduced quality of life? A case-control study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1441–4.

- Landgren AJ, Dehlin M, Jacobsson L, Bergsten U, Klingberg E. Cardiovascular risk factors in gout, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: a cross-sectional survey of patients in western Sweden. RMD Open 2021;7:e001568.

- Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics 2016;34:645–9.

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83.

- Orwelius L, Nilsson M, Nilsson E, Wenemark M, Walfridsson U, Lundström M, et al. The Swedish RAND-36 Health Survey – reliability and responsiveness assessed in patient populations using Svensson’s method for paired ordinal data. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2017;2:4.

- Laucis NC, Hays RD, Bhattacharyya T. Scoring the SF-36 in orthopaedics: a brief guide. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:1628–34.

- Janssen CA, Oude Voshaar MAH, Ten Klooster PM, Jansen T, Vonkeman HE, van de Laar M. A systematic literature review of patient-reported outcome measures used in gout: an evaluation of their content and measurement properties. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2019;17:63.

- Husted JA, Gladman DD, Farewell VT, Long JA, Cook RJ. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 1997;24:511–7.

- Kvien TK, Kaasa S, Smedstad LM. Performance of the Norwegian SF-36 Health Survey in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. II. A comparison of the SF-36 with disease-specific measures. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1077–86.

- Jajic Z, Rajnpreht I, Kovacic N, Lukic IK, Velagic V, Grubisic F, et al. Which clinical variables have the most significant correlation with quality of life evaluated by SF-36 survey in Croatian cohort of patient with ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis? Rheumatol Int 2012;32:3471–9.

- Kiltz U, van der Heijde D. Health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009;27:S108–11.

- Dehlin M, Landgren AJ, Bergsten U, Jacobsson LTH. The validity of gout diagnosis in primary care: results from a patient survey. J Rheumatol 2019;46:1531–4.

- Wallman JK, Alenius GM, Klingberg E, Sigurdardottir V, Wedrén S, Exarchou S, et al. Validity of clinical psoriatic arthritis diagnoses made by rheumatologists in the Swedish national patient register. Scand J Rheumatol 2022:1–11. doi:10.1080/03009742.2022.2066807

- Waldenlind K, Eriksson JK, Grewin B, Askling J. Validation of the rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis in the Swedish national patient register: a cohort study from Stockholm county. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:432.

- Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1980;23:137–45.

- Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91.

- Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, Kennedy LG, O’Hea J, Mallorie P, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2281–5.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19:210–6.

- Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care 1995;33:As264–79.

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE Jr. The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey – I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med 1995;41:1349–58.

- Simon GE, Revicki DA, Grothaus L, Vonkorff M. SF-36 summary scores: are physical and mental health truly distinct? Med Care 1998;36:567–72.

- Chorus AM, Miedema HS, Boonen A, Van Der Linden S. Quality of life and work in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis of working age. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1178–84.

- Sokoll KB, Helliwell PS. Comparison of disability and quality of life in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1842–6.

- Husted JA, Gladman DD, Farewell VT, Cook RJ. Health-related quality of life of patients with psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:151–8.

- Law L, Beckman Rehnman J, Deminger A, Klingberg E, Jacobsson LTH, Forsblad-d’Elia H. Factors related to health-related quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis, overall and stratified by sex. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:284.

- Khanna PP, Nuki G, Bardin T, Tausche AK, Forsythe A, Goren A, et al. Tophi and frequent gout flares are associated with impairments to quality of life, productivity, and increased healthcare resource use: results from a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:117.

- Fortune DG, Richards HL, Griffiths CE. Psychologic factors in psoriasis: consequences, mechanisms, and interventions. Dermatol Clin 2005;23:681–94.

- Suurmeijer TP, Waltz M, Moum T, Guillemin F, van Sonderen FL, Briancon S, et al. Quality of life profiles in the first years of rheumatoid arthritis: results from the EURIDISS longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:111–21.

- Howren A, Bowie D, Choi HK, Rai SK, De Vera MA. Epidemiology of depression and anxiety in gout: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 2021;48:129–37.

- Dagfinrud H, Mengshoel AM, Hagen KB, Loge JH, Kvien TK. Health status of patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a comparison with the general population. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1605–10.

- Hallert E, Björk M, Dahlström O, Skogh T, Thyberg I. Disease activity and disability in women and men with early rheumatoid arthritis (RA): an 8-year followup of a Swedish early RA project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1101–7.

- Thyberg I, Dahlström Ö, Björk M, Stenström B, Adams J. Hand pains in women and men in early rheumatoid arthritis, a one year follow-up after diagnosis. The Swedish Tira Project. Disabil Rehabil 2017;39:291–300.

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J. The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey III. Evaluation of criterion-based validity: results from normative population. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1105–13.