ABSTRACT

The earliest concerns New Zealand farmers had about ticks are chronicled here, together with the eventual invasion and establishment of Haemaphysalis longicornis, which, still today, remains the only livestock tick parasite in this country. Early attempts, legislative and practical, to restrict the spread of the tick, and later attempts to manage a permanent problem are presented and discussed. Brief biographies of many of the main persons mentioned in this history are presented in an Appendix, as is a reconsideration of how the tick may have arrived.

Introduction

Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann, Citation1901, is the only ixodid tick in New Zealand affecting livestock and the only one introduced by human agency. Heath (Citation2016) reviewed the biology, ecology and management of the tick, only briefly touching on the early history and circumstances surrounding its introduction, originally discussed by Myers (Citation1924, ). This review expands upon published information and also examines early (nineteenth century) attitudes to, and concerns about, ticks in general in New Zealand, as well as eventual recognition that a cattle tick was established, and the response of government to combat it.

Figure 1. Cover of Myers’ (Citation1924) classic study of the New Zealand cattle tick. Photo: A.C.G Heath

Haemaphysalis longicornis is an east Asian endemic tick, most likely introduced to New Zealand from Australia (Heath Citation2016), where it was first discovered in 1897 in Lithgow, NSW, possibly of Japanese origin (Hoogstraal et al. Citation1968). The first New Zealand tick specimen for which there is a reliable record was found in December 1910 near Kaitaia (Myers Citation1924, p. 99), and the species’ more widespread occurrence was obvious by 1911 (Myers Citation1924, p. 95). The tick was undoubtedly present for some time before then as its distribution through much of North Auckland suggests, with many more records accruing throughout 1912–1918 (Myers Citation1924, p. 96). A report by W.D.S. MacDonald, then Minister for Agriculture (Evening Post, Wellington, 19 April, Citation1919, p. 9) stated that the tick had been known ‘in the extreme north’ for at least 25 years, which would make 1894 its possible earliest record, but he also said it had been known for 12 years in ‘another area north of Auckland’, i.e. from 1907.

Live animal imports to New Zealand, especially cattle, began in 1839 (Stevens and Barton Citation1966) and these, together with imports of hides (Wairarapa Daily Times, Masterton, 16 July, Citation1896, p. 2; New Zealand Mail, Wellington, 13 August, Citation1896, p. 4), were possible means of tick entry. Salting of hides (six days soaking in brine; New Zealand Mail, Wellington, 13 August, Citation1896, p. 4) was, however, considered a safe procedure that killed ticks and avoided live tick importation (Auckland Star, Auckland, 29 September Citation1896, p. 5). Cattle shipped to Australia from Batavia (present day Jakarta, Indonesia) were washed in sea water during the voyage, although Gilruth (Citation1912, p. 21) was convinced that such treatment would not have killed ticks.

Until a correct identification was established, it was thought either Ixodes ricinus (Linnaeus, 1758) or Haemaphysalis punctata Canestrini and Fanzago, 1878 were present, but both were misidentifications. The error regarding I. ricinus is discussed in Heath and Palma (Citation2016), whereas H. punctata – a species name overlooked by Heath and Palma (Citation2016) – is a Palearctic tick never recorded in New Zealand, nor intercepted at the border (Heath and Hardwick Citation2011). Haemaphysalis longicornis was originally known as H. bispinosa until differentiated from that species by Hoogstraal et al. (Citation1968). When known as H. bispinosa its early discovery and distribution were chronicled by Myers (Citation1924; see Appendix 2) and with earlier, but less detailed accounts by Reakes (Citation1918; see Appendix 2) and Miller (Citation1922; see Appendix 2). These various circumstances and response to the tick menace are examined in more detail here.

The common name for Haemaphysalis longicornis shows some variations over its history. Neumann (Citation1901, p. 261) in his original description stated: ‘ … s’en distingue … par la … plus grande de l’épine infére retrograde du 3° article des palpes, par l’épine des hances I bien plus développée … aussi’. Thus, the rearward-pointing ventral spine on palp article 3 and that on the first coxa were large enough to warrant the specific epithet, ‘longicornis’. Hoogstraal et al. (Citation1968) called the species: ‘The Australian-Northeast Asian haemaphysalid’, and earlier, Roberts (Citation1952), in an Australian setting, referred to ‘the New Zealand cattle tick, or bush tick’. The former name, or just ‘cattle tick’, is used in New Zealand (following Myers Citation1924 and others), whereas ‘bush tick’ tends to be the Australian epithet. These common names were in regular use, at least in the western Pacific, until 2018, when H. longicornis was found to be present in the eastern USA (Rainey et al. Citation2018). This first record did not employ a common name for the new invasive. It was only when Egizi (Citation2018) applied to the Entomological Society of America to establish a new common name for the tick, that the name ‘Asian longhorned tick’ came into common use, at least in the USA publications (e.g. Wormser et al. Citation2020).

Methods

Early records about ticks were found on-line in New Zealand Government Parliamentary Papers, part of which were searched on Papers Past, (https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/parliamentary), first from the Votes and Proceedings of the House of Representatives (1854–56), then Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives (1858–1950). The latter contain within them the Annual Reports of the Department of Agriculture (1886–1910), the Department of Agriculture, Commerce and Tourists (1910–1919), and the Board of Agriculture (1919–1920), then the Department of Agriculture from 1920 onwards. Within these volumes Directors-General, Divisional Directors, Veterinarians and Inspectors of Stock presented their reports. Individual reports of the Department of Agriculture post-1950 were also consulted, together with searches of digitised newspapers in the Papers Past database using search terms such as: ‘tick’ and ‘cattle tick’. Regulations regarding cattle tick were located principally within The New Zealand Gazette. Scientific publications and other relevant literature provided the remaining material.

Direct quotes and verbatim excerpts from reports have been given in some sections of this review to give a sense of the immediacy of the moment. The newspaper articles cited provided information (and interpretation) for a public either less inclined to read official reports, or with no access to them.

Possible means of entry of the tick

A discussion about ways in which the tick is thought to have entered New Zealand is presented in Appendix 1.

Historical personages named in text

Most of the veterinarians, scientists and members of parliament mentioned in the text have brief biographical entries in Appendix 2.

The historical setting before the arrival of the tick

Even though New Zealand became a colony in its own right in 1841, previously being administered as part of New South Wales (Sinclair Citation1959), there was subsequently still close contact between the two territories, and farmers were alert to the dangers of importing livestock diseases from what in a sense was a local market. For example, Graham (Citation1861; see Appendix 2) expressed concern about pleuro-pneumonia being brought in by cattle from NSW. It was not until 1880, however, that there was any consideration of prohibiting imports of cattle (Wanganui Herald, Wanganui, 12 June Citation1880, p. 2) because of the disease. Farmers were still agitating in 1888 for quarantine regulations that would prevent the introduction of cattle diseases from Australia (New Zealand Herald, Auckland, 1 October Citation1888, p. 5).

To add to public concerns, and before there was a livestock tick in New Zealand, farmers were warned of the discovery of another cattle tick, known then as Boophilus microplus Canestrini, 1888 – now Rhipicephalus australis Fuller, 1899 (Estrada-Peña et al. Citation2012) – present in Queensland, Australia, with the earliest mention in 1895 (The Press, Christchurch, 12 December Citation1895, p. 2.). Entomologist, W.M. Maskell (see Appendix 2) is quoted that it was ‘ … not likely the Queensland tick would be introduced into New Zealand as it was a tropical insect [sic], and did not come further than latitude 26’ (South Canterbury Times, Timaru, 21 January Citation1897, p. 3). In fact, R. australis – known as the Australian cattle tick – now reaches as far as 31°S (Barker and Walker Citation2014) and strict quarantine measures at the NSW border, as well as bioclimatic constraints, may stop further progression southwards.

A Papers Past search using the term ‘Cattle tick’ resulted in 4015 ‘hits’ and ‘Cattle tick in New Zealand’ a more manageable 44. Early Australian records found ‘their’ tick on the east coast of Queensland as far south as the Burdekin River. A little earlier, the experience of USA with Texas fever, and ticks as carriers, was reported (Bruce Herald, Tokomairiro, 16 May Citation1893, p. 4), but no comment on Australia or New Zealand. These were the earliest references to ticks that could be found in local New Zealand newspapers.

Discovery of the tick

When New Zealand was found to have its own cattle tick (Reid Citation1911; Wairarapa Age, Masterton, 23 November Citation1911, p. 3; Myers Citation1924), there was considerable concern over the following years that it might be the Queensland tick, despite reassurances to the contrary (South Canterbury Times, Timaru, 21 January Citation1897, p. 3). Strangely, apart from these public notifications in the newspaper and a farmers’ journal, there was no mention of the new arrival in Government reports until 1918 (Pope Citation1918; Reakes Citation1918). There was too some confusion as to the actual species involved, with Reid (Citation1911; see Appendix 2) naming I. ricinus as the culprit and Reakes (Citation1918) implicating both H. punctata and I. ricinus, but a little later (Wairarapa Age, Masterton, 18 October Citation1919, p. 6) he reassured farmers that the tick was not from Australia as suggested by some. Neither of the two species he named occurred in Australia (Roberts Citation1970).

Reakes was reported (Wairarapa Age, Masterton, 18 October Citation1919, p. 6) that he had been informed by Professor George H. F. Nuttall (Cambridge University, England) that the tick was a species associated with India, China and Japan. Reakes (Citation1919) did not name the tick, but it could have been either of two species as Nuttall and Warburton (Citation1915, p. 509) listed both H. bispinosa Neumann. 1897 and H. campanulata Warburton, 1908 from that combination of regions. Haemaphysalis punctata and I. ricinus are Palearctic (Northern Hemisphere) species found commonly on mammals and birds, although both are also known from lizards and tortoises (Guglielmone et al. Citation2014), but neither are found in New Zealand.

Eventually Haemaphysalis bispinosa was declared by Reakes to be the species present (Northern Advocate, Whangarei, 10 February Citation1920, p. 3), following a recommendation by W. F. Cooper and L.E. Robinson of G.H.F. Nuttall’s laboratory in Cambridge, who had received the ticks in 1918. Subsequently, Hoogstraal et al. (Citation1968, Citation1969) demonstrated that H. bispinosa was not the species present in New Zealand, but the resurrected H. longicornis, thus placing the New Zealand cattle tick geographically within the western Pacific, and separating it from H. bispinosa which occurs in the Indian/west Asian faunal region(s).

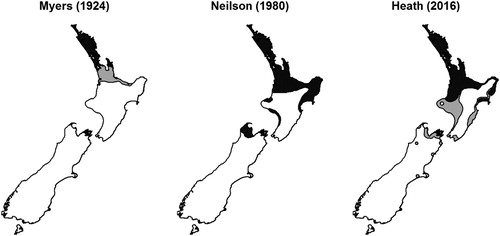

Although it had now been confirmed that the New Zealand cattle tick was not the same as the Queensland tick, R. australis (Otago Witness, Dunedin, 30 April Citation1919, p. 9), it was still considered a ‘growing menace’ as it was spreading from its original North Auckland locality (Taranaki Daily News, New Plymouth, 1 April, Citation1919, p. 7). There were even discussions about placing an embargo on cattle going to the South Island (Wanganui Chronicle, Wanganui, 3 May, Citation1919, p. 8). There was a suggestion that, if left unchecked, it could overrun the whole of the North Island (Young Citation1920b; see Appendix 2). This concern has been largely realised () because, except for the higher altitude regions, the tick has now nearly reached the limits of its potential geographical range in New Zealand (Lawrence et al. Citation2017), with predicted climate change unlikely to alter this situation greatly.

Figure 2. Change of distribution of Haemaphysalis longicornis with time. Black areas indicate high risk and grey low risk. In the 1924 map the black area corresponds to Area A, and the grey to Area B, as originally designated in the cattle tick regulations (Cattle-tick regulations … Citation1922). Reproduced with permission. Published in Veterinary Parasitology, volume 243. Lawrence KE, Summers SR, Heath ACG, McFadden AMJ, Pulford DJ, Tait AB, Pomroy WE. Using a rule-based envelope model to predict the expansion of habitat suitability within New Zealand for the tick Haemaphysalis longicornis, with future projections based on two climate change scenarios. pp. 226–234. Copyright Elsevier (2017).

Confusion: too many ticks

To the untrained or unaided eye all ticks can look very similar, so it was not unusual that, in the early days, the New Zealand cattle tick was confused with other species. In addition, hosts with their specific tick were sometimes accused of disseminating cattle tick. The kiwi especially was blamed as its own tick (Ixodes anatis Chilton, 1904) was commonly seen in the early days. In fact, W.W. Smith, a New Plymouth naturalist, reported he had found ticks on kiwis in Pukekura Park, on the fringes of New Plymouth city over a 9-year study period (Stratford Evening Post, Stratford, 8 October, Citation1931, p. 5; Medway Citation2012). In this instance the tick species was not named, although, given the scare about cattle tick and misunderstandings about ticks in general, there may have been an implication that the kiwi was culpable of disseminating ticks harmful to livestock.

It transpired that such misgivings were not without substance as kiwis have been found to harbour immature H. longicornis (see Heath Citation2010a) and other wildlife was found to be at risk too. In 1918, a Wanganui farmer caught wekas (Gallirallus australis greyi (Buller, 1888)) with: ‘ … ticks clinging to them so tenaciously that they could not be pulled away without tearing the skin’. He also reported that the birds were ‘far gone’. His view was that the tick had caused a reduction in weka numbers (Horowhenua Chronicle, Levin, February 11, Citation1936, p. 4). Somewhat surprisingly, the first and only confirmed record of H. longicornis on a weka was made over 70 years later (Heath Citation2010b), with Myers (Citation1924) not finding any wekas infested during his exhaustive study. It is unlikely that the seabird tick Ixodes auritulus zealandicus Dumbleton, 1961, the only other species of the New Zealand tick fauna found to date on weka (Bishop and Heath Citation1998), would occur in the Wanganui region.

Black-backed gulls were also blamed as carriers of cattle ticks (Lyons Citation1930; Chronicle, Levin, 25 March 1930, p. 6; Evening Post, Wellington, 19 April Citation1930, p. 13), although it is more likely that the ticks were Ixodes laridis Heath and Palma Citation2017, a species found on gulls, gannets and cormorants (Heath and Palma Citation2017). Haemaphysalis longicornis has never been recorded from seabirds (Heath et al. Citation2011).

From 1918 to 1949, information on cattle tick featured regularly in Annual reports of the Department of Agriculture, as did the then very prevalent sheep ked (Melophagus ovinus Linnaeus, 1758; Diptera: Hippoboscidae) known, incorrectly, as the sheep-tick. This duplication of names can cause confusion, even today, although the cattle-tick regulations (Cattle-tick regulations … Citation1919; Reid Citation1923) explicitly excluded M. ovinus from the provisions of the Stock Act.

Dealing with the tick problem

The long gap between 1911, when the cattle tick was known to be present, and ‘official recognition’ in 1918 is not fully explicable, despite many accumulated tick records within North Auckland between 1911 and 1918. The first mention of the tick in a Government annual report (Pope Citation1918, p. 4) appeared to try and diminish any concerns:

What might be termed a mild scare was caused in the North Auckland district by an abnormal occurrence of ticks on cattle, horses &c. These ticks are identified as distinct from the Queensland cattle-tick, and tick fever has never been present in New Zealand; moreover, importation of cattle from affected countries is prohibited; there is thus small cause for alarm. Regulations dealing with the matter, are, however, being considered.

The following is a record of early discussions on preparations for dealing with the tick, summarised by Director-General of Agriculture Reakes (Citation1919, p. 7), but given in full by the Director of the Live-stock Division Young (Citation1919, p. 11) and here verbatim:

During the past season considerable attention and consideration has been directed to this pest. Two very representative meetings of farmers, auctioneers, and others were held in Auckland, which were largely attended. The whole question was discussed at conssiderable length in all its aspects, and it was decided at the first meeting not to definitely fix a quarantine area until information could be gathered as to the extent in which the parasites had actually spread. During the six months following a large amount of available information was collected, and it was found that the original suggestion regarding a quarantine area would be likely to be impracticable. A further meeting was therefore called, at which, after careful consideration and. discussion, it was recommended that the idea of quarantining a given district be abandoned. This was practically due to the extreme difficulty which would have existed in securing a workable scheme at any boundary which might have been fixed. The alternative was to place cattle-tick in much the same category as lice in sheep – that is to say, in any district or place where cattle-ticks were found that place would at once come under the operations of comprehensive regulations to be drawn up for this purpose. These regulations have now been drafted and submitted for approval and amendment, if necessary, pending which no compulsory action has been taken with regard to the eradication of the pest, but every endeavour has been made to secure this by the spread of information amongst the settlers in the affected districts, and by the erection of cattle-dips subsidized by the Government. One of these is in course of erection at Oakleigh. It was considered advisable to have this dip completed and in working-order before commencing to erect others, as it may be found that many improvements could be effected that did not show up until after the dip was in working-order. Mr. H. Munro, who was sent to Queensland to investigate the Queensland tick, has been stationed as Principal District Inspector in the Auckland Province. It may therefore be reasonably expected that the spread of this pest will be arrested, and that a decided reduction of its activity may be anticipated in the near future.

Cattle tick regulations: the political solution

During the tenure of William Nosworthy (see Appendix 2), Minister of Agriculture between 1919 and 1926, and after the official acceptance of the tick’s presence and recognition of its harmful potential, regulations were drawn up (Young Citation1919) and a draft soon produced and gazetted in 1919 (Reakes Citation1920a, Citation1920b). Thus, the cattle tick became a scheduled (notifiable) disease, although dipping facilities had not yet been provided (Young Citation1920a). Regulations to govern the compulsory dipping of cattle were finally proposed in 1919 (Cattle-tick regulations … Citation1919) and publicised (New Zealand Herald, Auckland, 16 September, Citation1919, p. 8.), with erection of dips and dipping commencing around two years later (Poverty Bay Herald, Gisborne, 31 May, Citation1921, p. 3; Reakes Citation1921). Initially, four dips were erected at the southern limits of the tick distribution and all cattle needing to move beyond were dipped. Dipping of cattle within the endemic area (most of North Auckland) was required every 21 days (Auckland Star, Auckland, 11 May, Citation1921, p. 5).

Amended regulations were gazetted in 1922 (Cattle-tick regulations … Citation1922). They consisted of 24 clauses (regulations) relating mainly to notification when ticks were found, movements of tick-infested stock, obtaining permits to move stock and requirements to dip infested stock, with penalties ranging from £5 to £200 on conviction. In addition, Areas A and B were defined (), and designated crossing places for stock named (Cattle-tick regulations … Citation1922; Myers Citation1924). In 1923 the dipping requirement was expressed in greater detail, being made compulsory and incumbent upon stock owners to keep stock free of tick (Amending regulations … Citation1923; Cattle-tick regulations … Citation1923). The regulations were maintained until 1940 (The stock (cattle-tick) regulations … Citation1940), then revoked (Revocation of stock … Citation1940).

At the start, pressure was put on farmers to provide dipping facilities under what in fact was a compulsory process, the threat being, especially in Northland, that the cattle business would be held up, and land values would go down (Northern Advocate, Whangarei, 30 September, Citation1920, p. 1).

There was a minimum fine of £10 for any vehicle suspected of, or carrying infested stock and, if so, it had to be cleaned before being used again, Furthermore, no stock were to be shipped from North Island to South Island unless an inspector had declared them free of ticks. The Divisional Director’s report for that year (Young Citation1921, p. 13) is here verbatim:

During the year the regulations for the control of cattle-tick have been much more stringently enforced than during the previous year, and the construction of cattle-dips in the tick infected areas has been considerably accelerated in consequence. The Government subsidy of pound for pound up to £150 towards the construction of public cattle-dips which are erected in conformity with the Government plans and specifications has been approved in connection with thirty-four dips. Of this number nineteen have already been completed, seven are in course of construction, and work has not yet commenced on the remaining eight. The plan on which the dips are being built has given general satisfaction, and those so far completed have been erected in a satisfactory manner. Stockowners and auctioneering companies in the tick-infested areas have co-operated well with the Department’s officers in fighting the tick pest, and every endeavour will be made to ensure a continuation of this desirable condition. The practice of passing all cattle through a dip immediately prior to their being offered for sale at public auctions has become practically universal in the badly infested areas, and is freely submitted to by stockowners, notwithstanding that there is no provision in the regulations enforcing such practice. The beneficial effect which dipping has on the general health and well-doing of the cattle, quite outside its tick-killing qualities, is being recognized and appreciated by stockowners. During the past year advantage has been taken of every available source of information, for the purpose of ascertaining as accurately as possible just what localities arc affected with tick, and our knowledge on this point is now fairly accurate. The necessity for strengthening and enlarging the scope of the regulations has been recognized, and the defining of areas for the better control of the tick within those areas, and for the protection of clean districts, is also being carefully gone into, and recommendations regarding new or amending regulations towards this end will shortly be submitted.

Compulsory dipping and its practicality

Swim (also known as plunge) dipping, with arsenical dip fluids (arsenious oxide: 7 lbs [3.2 kg] in 400 gallons [1818.4 litres] of water; Cattle-tick regulations … Citation1922) was initially seen as the way to keep the tick both confined in its original locality and to reduce numbers on stock. A total of 38 dips was in use by 1922, 19 of those being added in that year (Reakes Citation1922), and dip strength was being tested in tick-infested areas to ensure standard concentrations were maintained (Aston Citation1922).

A swim dip design was produced with full-sized plans available from the Department of Agriculture (Young Citation1920b). Spraying and hand dressing with dip chemical were also offered as treatment options. By 1923, a total of 49 dips had been completed ‘to protect clean areas from ticks’ (Reakes Citation1923). In what appears to be an attempt to provide a framework for monitoring and managing the tick as outlined by Young (Citation1922) (above), its distribution () was divided into two areas or districts: A and B. The following is a verbatim newspaper report that shows the extent to which information was conveyed to farmers, and the clear, concise language used by Director of the Live-stock Division, A.R. Young (Northern Advocate, Whangarei, 28 February Citation1922, p. 7):

For some time past it has been common knowledge that cattle tick has existed amongst the herds of the northern portion of the North Island, and was causing grave concern to pastoralists. To such an extent was the pest affecting herds in the north that many of the settlers in order to protect their cattle went to the expense of creating dips in which the cattle could be treated with a view to exterminating the vermin which were making so much headway. A ‘Dominion’ reporter waited upon Colonel A. R Young, Director of the Live Stock Division of the Agricultural Department, with a view to ascertaining the reasons for amending the regulations dealing with cattle tick. ‘There were several factors responsible for this,’ said Colonel Young. ‘All over the world, where cattle ticks exist, they are regarded as most unwelcome visitors, as they cause great loss by undermining the health of cattle, damage the hides, and also spread the disease over the countryside. The Department has taken this action with the view of preventing the further spread of the disease.' The Director of the Live Stock Division went on to explain that the new regulations now in force embrace the whole of the north, which has been divided into two sections – (a) An area well known to be infested, and (b) an area where occasionally ticks are being found. Much controversy, he stated, had taken place over the boundaries so drawn, as it appeared that in many cases patches of country in each appear to be free from tick. ‘But against this,’ declared Colonel Young, ‘the explanation of the Department has been that ticks may be conveyed a long distance, yet not make their presence known for two or three years. It was, therefore, decided that it was a sounder policy to get well outside where ticks at present existed, so that as time warranted the boundaries could be contracted than to adopt a narrower sphere, and be continually extending so as to overtake fresh cases’.

DIPPING IN A. AREA COMPULSORY

Colonel Young said that under the new regulations the dipping of cattle in the A. area had been made compulsory. This was brought about by the fact that some settlers were not taking advantage of the dips already erected in the district by other energetic settlers. That being so, it was a hopeless task to try and eradicate tick, as a few breeding grounds would always be left. No cattle may now leave A. area, whether infected or not, before they are first passed through an approved dip. This would ensure that B. area, which in reality is a buffer state, would not be further infected. Dips should not, however, he advised, be erected too close to the boundary, so as to allow of this being gradually contracted when the time proved opportune, as’ such contraction would leave the dips outside the area, and they would, therefore, not be available. ‘Is is [sic] possible to eradicate tick:’ was a question put by the reporter. ‘Yes,’ replied the Director of the Live Stock Division; ‘it has been demonstrated in America and Africa that ticks can be eradicated where systematic dipping is in force and where the settlers co-operate wholeheartedly in the matter, not only by dipping, but by (burning off all rough herbage at the proper season of the year’. The young seed ticks, he explained, gain access to the cattle principally by climbing up the stalks of long grass. It was necessary that dipping should take place at regular intervals, otherwise the ticks would drop to the ground in a fertile state and carry on business as usual. ‘The practical way to look upon the procedure,’ said Colonel Young, ‘is to recognise that the ground is infected with tick, and that the cattle only act as collectors thereof. So soon, therefore, as they have collected a number of ticks these must be destroyed by dipping or other means, whilst the stock return to the pasture to collect more ticks’. It would appear that the Department has taken every precaution, as no cattle can now leave A. area without a certificate that they have been dipped, and no cattle can leave B. area before they get a permit from an inspector of stock. There are no restrictions upon the importation of cattle into the prescribed areas, but no cattle will be allowed oat of the infected areas, even for show purposes. The A. area embraces all the territory north of a line drawn from Manukau Harbour to Coromandel, while the B. area consists of the country below this to a line stretching from Kawhia to Cape Runaway.

Detailed description of the areas – reprinted from the Stock Act, Citation1922 – is given in Cattle-tick regulations … (Citation1922) and again by Reid (Citation1923, p. 550), with Myers (Citation1924, p. 68) briefly describing their limits, but also providing a map. shows approximate boundaries. Area A was the North Auckland district, bounded by Auckland City in the south (north of a line drawn from Manukau Harbour to Coromandel) and Area B (all the territory south to a line from Kawhia to Cape Runaway) wherein there were scattered tick populations. This represented what was the remainder of the tick’s range, being bounded in the south around latitude 38°S, near Whakatane. In 1923, slight amendments were made to district boundaries and crossing areas, especially in the Bay of Plenty (Amending regulations … Citation1923).

John Golding Myers and the cattle tick study

During 1923–1924, J.G. Myers, then a scientist at the Biological Laboratory (New Zealand Department of Agriculture) in Wellington, undertook a comprehensive study on the cattle tick which examined every aspect of its biology, ecology, distribution and history that could be gleaned, and which stands today as a classic of its kind (). Most of his findings have not been superseded and remain a sound base upon which most future studies were launched. A brief biography of Myers is given in Appendix 2.

Importance of tick questioned. Australian advice

Despite the preventive measures advocated and regulations in place, the tick and its harmful implications appeared not to be fully accepted by parliamentarians: ‘The Minister of Agriculture, O. J. Hawken (1926–1928, see Appendix 2), in reply to a question, said experiments had shown that cattle tick in New Zealand was not likely to be the menace it was once thought’ (Otago Daily Times, Dunedin, 2 August Citation1926, p. 8). This view somewhat understated later evidence of the economic impact of H. longicornis (Heath Citation2016) and the recent introduction of more pathogenic theileriosis-causing organisms (McFadden et al. Citation2016). In 1925, S.B. Gange, an Australian member of the NSW Cattle Tick Committee, came to New Zealand to give his opinion that the tick: ‘could be eradicated at comparatively small cost’ (Auckland Star, Auckland, 24 January Citation1925, p. 7). He recommended that farms be quarantined and then dipping would ‘have the desired effect’. His optimism was somewhat premature, especially given that Australia had not been able, at that time, to contain R. australis. Containment of any sort for H. longicornis was unsuccessful however and, by 1929, the tick was found in the South Island, in Hamama near Takaka (Stratford Evening Post, Stratford, 21 January Citation1930, p. 6.) showing eradication to be a vain hope.

The substance of farmer concerns, and the reality

The discovery of a livestock tick in New Zealand aroused concerns in farmers that there would be a problem akin to that in Australia where Rh. australis had been found to transmit the disease called ‘Tick fever’ also known as redwater fever. Now known to be caused by Babesia bigemina, with the later addition of B. bovis, these protozoa (piroplasms) were fatal to many cattle and left debilitated survivors. The first confirmed record of redwater fever in Australia was said to be in 1880–1881 with cattle brought into the Northern Territory (NT) from Queensland (Gilruth Citation1912, p. 19), yet despite careful interrogation of graziers with a long history of cattle farming, evidence of redwater fever earlier or in other states could not be discovered. Eventually, Gilruth concluded that the year 1872 and cattle imported from the Dutch Indies were the source of both the tick and babesiosis in the NT, which had been the source of the disease for Queensland, which had reintroduced it to the NT later. It was estimated that there had been a nearly 50% reduction in cattle numbers in Queensland between 1894 and 1900, the majority of deaths being ascribed to tick fever (Anon. Citation1919). Sprent (Citation1986) in a brief history of parasitology in Brisbane wrote that the causative organism of redwater disease (also called Texas fever) was identified in the NT in 1894 by CJ Pound but no specific link made to Texas fever. That connection was made in 1895 by JS Hunt who confirmed the identity and pathogenesis of what was probably B. bigemina. No mention of Gilruth’s (Citation1912) report was made by Sprent (Citation1986).

New Zealand farmers were understandably worried about these diseases occurring in a country relatively close to them and with whom they shared livestock and livestock products. It was natural that tick-borne disease in general would become a focus for concern, and questions as to the potential for H. longicornis to transmit tick fever were raised. New Zealand newspapers carried many stories about tick fever, with the term providing 904 ‘hits’ on the Papers past website, the earliest in 1896. Once it became established that the New Zealand tick did not pose the danger inherent in R. australis, the government and farmers relaxed, seemingly unaware that even in the absence of disease, H. longicornis could still debilitate stock if present in large numbers (‘tick worry’), damage hides, and some animals died. Myers (Citation1924) discussed the effects of tick although he described the data as ‘fragmentary’ (p. 44). Hide damage, irritation, loss of condition and possibly a decrease in milk yield were the only effects on cattle mentioned.

Damage to pelts, hides and velvet by cattle tick is still common, and there are production-limiting effects in stock, as well as deaths (Oswald 2109). In 1982 Theileria orientalis was found (James et al. Citation1984) in the north of New Zealand, with instances of ill thrift, decline in milk and meat production, anorexia, malaise, depression and diarrhoea (Watts et al. Citation2016). There were further cases, specifically by T. orientalis Chitose in 2006 and 2009, and in 2012T. orientalis Ikeda was identified, and found to cause significant economic damage to dairy cattle (McFadden et al. Citation2016).

Later years; living with cattle tick

The introduction of compulsory dipping as a preventative measure did not extend to Taranaki, which was unfortunate as the tick had established in that region by 1925, having only been ‘considered’ (not proven) present earlier in that region (New Zealand Herald, Auckland, 12 January Citation1925, p. 9).

Between 1925 and 1940, when compulsory dipping finally ended (Evening Post, Wellington 18 July Citation1940, p. 15), the tick was watched closely and demonstrated the versatility with which it could flummox farmers and government. Official opinion on the tick was a mix of concern and confidence, as follows (Reakes Citation1926, p. 4): ‘[Ticks] … have continued to be harmless so far as any ill effect upon the health of animals is concerned’. Ticks were sent to Townsville to Queensland Government laboratory, and, continued Reakes:

… found incapable of transmitting tick-fever from animal to animal. As these ticks progress southwards in the Dominion they seem to find it increasingly difficult to establish themselves, especially when away from the coastal areas, and a number of farms where they at one time appeared in small numbers are now quite clear of them. They damage hides when present in sufficient number, and this point needs special attention and in itself warrants farmers doing all that is possible to eradicate them.

Distribution changes

Lyons (Citation1926, p. 13), as Director of the Livestock Division (see Appendix 2), reported that there was ‘No diminution in “A” area, no tendency to spread to … area known as B, and may actually be said to have decreased or almost disappeared from some districts where it was previously found’. The quarantine area in the Waitara district had been enlarged as ticks were found on a farm outside the original area. A dip had been erected at Mohakatino by the Government near the northern boundary of Taranaki and all cattle going south were required to be dipped. A dip was also erected by farmers at Waitara.

The next year, Lyons (Citation1927, p. 16 & 17, verbatim) wrote that: Coromandel districts has [sic] been much lighter than for some years past. The cold season experienced may account for this to some extent. There are, however, other factors at work, such as picking and spraying. It is also realized that better farming methods, such as top-dressing, keeping the roughage eaten out, ploughing, and burning, are all factors which assist in reducing the ticks to a minimum. The hearty co-operation of the settlers is asked for in this respect. If owners will individually see that their stock is kept free from ticks, and that their pastures are kept free from roughage, which affords a breeding-ground for the tick, it will go a long way towards the eradication of the pest. Where dairying is carried on, the method of control is comparatively simple. It is on the grazing-runs, where stock are seen only at irregular intervals, that difficulty is experienced, however much may be done in the latter case by occasional dipping, and also in destroying all roughage on the farm. In area B the position is better than it has been for several years. Very few fresh farms were infested, and in the majority of farms where ticks were found on stock in previous years none was found. The position at Waitara has improved; only a few ticks were found this season, and those all on properties previously affected. A constant inspection of all cattle within the area has been maintained, and all cattle within the area have been dipped or sprayed before removal.

It is to be regretted that during the season a further development took place regarding cattle-tick in Poverty Bay. Ticks were reported on several properties in an area adjacent to Tolaga Bay. Every endeavour was made to locate and eradicate the parasites in this district. Regular inspection of all neighbouring stock was carried out, and spraying and burning of cover were resorted to, and it is to hoped that by these means the ticks will be eradicated.

As it can be seen, there was some early hope of eradication; ‘ … as has been the case in previous instances when a single outbreak occurred’ (Lyons Citation1929, p. 15). Farmers who flouted the compulsory dipping or who moved stock without permit from one area to another were fined (e.g. Poverty Bay Herald, Gisborne, 29 April, Citation1929, p. 6). The tick continued to invade new areas and fluctuated in numbers (and consequent severity) in those areas where it was established, despite restricting stock movements, heroic efforts with dipping, as well as clearing and burning of scrub and herbage generally. Good advice, centred on dipping and pasture management was always forthcoming, with that given by Dr Reakes a prime example (Poverty Bay Herald, Gisborne, 25 March, Citation1936, p. 4).

The problem looks less of a problem

By 1928, a note of cautious optimism was seen in Lyon’s (Citation1928, pp. 15–16, verbatim) report, thus: An increase in the infestation of stock with cattle-tick is reported from the Whangarei, Tauranga, and Coromandel districts. With the exception of the foregoing, the indications from the remainder of the affected districts are that ticks are decreasing. In the infested area at Waitara the position this season is very satisfactory, only one tick having been found during the year. Indications at present point to the fact that there is every prospect of ticks being eradicated from this district. I regret to report, however, that a fresh outbreak occurred on a farm at Tataramaka, situated on the coast about twenty miles south of Waitara. Every precaution was taken to prevent the spread of the ticks, by spraying the stock, ploughing, and cutting and burning the scrub. As regards the Poverty Bay district, on farms situated from Tolaga Bay northwards, it may be mentioned that at a meeting of the settlers, convened by the Department, held at Tolaga Bay in January, arrangements were made to extend the area A boundary to a few miles south of Tolaga, while at the same time B boundary was extended to provide a good buffer area between the infected and clean country. Both sheep and cattle dips are in process of erection, and no stock will be permitted to leave the district without a permit. By this means it is hoped to protect clean areas from infection.

Confidence short-lived

Despite Lyons’ confidence, by 1929 the tick was reported to be abundant or damaging in the Gisborne area (Lyons Citation1929) and, more worryingly, it crossed Cook Strait with specimens recorded on farms in the Nelson District; one on a farm near Collingwood and another in the Takaka district, with the source not found despite exhaustive enquiries. Official suspicions that ticks were being carried by the agency of sea-birds were strengthened by a cattle tick supposedly being found on a gull on D’Urville Island (Lyons Citation1930; Horowhenua Chronicle, Levin, 25 March Citation1930, p. 6; Evening Post, Wellington, 19 April Citation1930, p. 13). As discussed earlier, the ticks on the gull were more likely to be I. laridis which is commonly found on gulls, a seabird group that has never had H. longicornis recorded from it (see Heath et al. Citation2011; Heath and Palma Citation2017).

From 1930 to 1933, cattle tick numbers and perceived severity fluctuated; worse in Area A in some localities, e.g. Opotiki, or stayed the same: Dargaville and Coromandel (Lyons Citation1930, p. 13). The situation in Area B of the Auckland district showed slight improvement, marked by fewer ticks and no fresh outbreaks. Further south, there was an increase in ticks and movement into ‘clean’ (tick-free) country in the northern Poverty Bay and unrestricted movement of sheep was blamed. Farmer concern was such that consideration was given to altering the boundaries governing tick movement and stock dipping (Lyons Citation1930, p. 14). There were also fresh outbreaks in Taranaki in farms close to the coast, southwest of New Plymouth towards Opunake, but no ticks were found in Waitara where ticks had appeared earlier.

During the years 1931–1933 there were occasional fresh outbreaks (Lyons Citation1931, Citation1932, Citation1933), and some districts with fewer ticks, but there was continued emphasis on keeping farms well-grazed and with rushes cleared and burned. Generally, Area A, Auckland District (north Auckland), where ticks had first been found and were well-established, maintained a sort of equilibrium, with districts further south more volatile as the distribution of tick increased by natural means and human agency.

By 1934, there was a new Director of the Live-stock Division, W.C. Barry (see Appendix 2) who, initially, was also fairly optimistic, noting (Barry Citation1934, p. 13) that although the tick was more numerous that season, there was too: ‘ … a realization that the tick is not a dangerous stock parasite having taken the place of the dread at first created by its discovery’. In addition to suggesting that farmers burn or otherwise destroy all cover for overwintering immature ticks; dipping and hand-picking was also promoted. Barry (Citation1936, p. 20) recognised that: ‘ … tick incidence to a large extent [is] governed by seasonal climatic condition. The varied means by which ticks can spread without agency of cattle makes control difficult … cattle-tick must not be regarded as a serious parasite of stock … ’.

In the light of later (and earlier) experience, this optimism was somewhat misleading, especially as new districts were becoming infested but, even so: ‘It is difficult to understand the importance which is attached to this parasite in the light of present knowledge’ (Barry Citation1937, p. 7) and: ‘There is growing appreciation among farmers regarding comparative innocuity of cattle-tick as skin parasite’ (Barry Citation1938, p. 10).

Farmers seek change

These attempts to diminish cattle tick as a problem may have been why, as far back as 1937 (Poverty Bay Herald, Gisborne, 20 March, Citation1937, p. 15), a farmers’ executive was pressing for the removal of the dip at Tolaga Bay and for cattle leaving the district to do so without needing dipping. This was because: ‘ … there was practically no tick in Tolaga Bay or thereabouts … ’. This was despite farmer concerns back in 1935 that ticks had been found on bobby calves originating in Opotiki, and en route to Gisborne, and that the calves should be dipped before leaving Opotiki so as to prevent ticks being moved to high country in the Matawai area (Poverty Bay Herald, Gisborne, 27 September Citation1935, p. 4). This prompted Barry to promise to investigate the problem (Poverty Bay Herald, Gisborne, 30 September Citation1935, p. 6). There may have been an enquiry, but in 1937 stock inspectors and farmers were still concerned and wanting cattle coming to Gisborne from the coast to be dipped before movement because, in their view, tick numbers had become ‘infinitesimal’ in Gisborne. A newspaper report (Poverty Bay Herald, Gisborne, 23 March Citation1937, p. 4) illustrated the nature of concerns outlined above.At one point even circus elephants were sprayed before the circus was allowed to move on. The effects of ticks appeared to be considered minimal, and in response to a question as to whether cattle ticks did any real damage, a stock inspector, Mr. Bould remarked: They damage all the lighter portions of the hides. Mr. Veitch: That is the cheapest part, of the hides. Mr. Bould: They will keep the condition down where the cattle are very thin. If that dip was done away with, in two years cattle from the northern area would be carrying ticks down here by the hundreds, and spraying would not be sufficient for fat stock shipped away from here. If the dip was moved to Mohaka, Gisborne would be an infested area, and bullocks going away from here would have to be dipped, not sprayed.

Despite these localised concerns, there were other farmers asking for the cattle tick regulations to be rescinded, and although concessions had been given on dipping, Barry (Citation1938) felt the whole position had to be carefully considered. There was certainly an appreciation how difficult the tick was to manage and restrain: ‘ … given the presence of disseminating agents such as birds and hares, etc.’ (Barry Citation1938). Dry conditions in the north in 1939 were postulated as leading to plentiful ticks, but there was no serious spread and no ‘clean’ areas became infested (Barry Citation1939, p. 10).

From this point on, at least for a few years, tick slipped from being a problem of semi-concern, to disappearing from Agriculture Department reports completely until 1949. The Second World War would have been a possible factor, providing more serious concerns, and there was no 1942 report, possibly because of the war. Barry (Citation1940, Citation1941) reported that there had been no spread of the tick to ‘clean’ areas and that an amendment to cattle-tick regulations (compulsory dipping requirement dropped) had no noticeable effect on the prevalence or otherwise of the parasite.

A new era; new weapons

World War II and later is recognised as the period of introduction of modern insecticides, replacing arsenicals, petroleum oils, nicotine, pyrethrum, rotenone and sulphur that had comprised the active ingredients of earlier pesticides (Ware and Whitacre Citation2004). In particular, D.D.T. (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) was available for public sale in the USA by 1948 (DDT. Wikipedia … Citation2019) and by 1949 was being tested for efficacy, in comparison with other active ingredients, against cattle tick in New Zealand (Filmer Citation1949, p. 90). Preliminary tests of various compounds used as sprays against the adult cattle-tick were conducted in the North Auckland peninsula. Both D.D.T. and Derris gave rapid kill, but within three days reinfestation had taken place and adults were engorging. Arsenical preparations were slower acting but gave more lasting protection; reinfestation occurred within ten to fourteen days. Benzene hexachloride (B.H.C., also known as Lindane) had the grave disadvantage that it was fat soluble and had a very persistent musty odour. There was concern that its use in dairy herds and premises may result in severe tainting of cream.

Tick has less heat, but still simmering

From 1949 until around 1969, cattle tick had no part in Department of Agriculture research projects directed by Filmer (see Appendix 2), although its effects were occasionally mentioned. For instance, McIlwaine (Citation1952, p. 85; see Appendix 2) reported that cattle tick was found to be in greater than usual numbers in the north, and similarly the following year (Fawcett Citation1953, p. 77; see Appendix 2), although the tick’s ability to transmit Rickettsia burnetii Derrick, 1939 (now Coxiella burnetii; Q-fever) and canine babesiosis, was mentioned, despite neither occurring in New Zealand.

The tick was not mentioned in 1954, although the next year Fawcett (Citation1955, p. 106) noted that infestations had been particularly heavy in the previous (1954) summer, and death of one sheep was ascribed to septicaemia following puncture wounds. There was also damage due to irritation and loss of blood in cattle (Fawcett1955, p. 109) with a line of lamb pelts in Poverty Bay severely damaged due to tick bites. Dairy cattle in that district were also reported to be affected (Fawcett Citation1956, p. 113). At that time also, cattle tick was defined as a disease in the Second Schedule of the Stock Act (Fawcett Citation1955, p. 106), unlike lice and keds.

Between 1957 and 1961 inclusive, ticks were not mentioned in the Department of Agriculture annual reports. Internal parasites were under study and there was concern about photosensitivity following use of the anthelmintic phenothiazine. It was found too that smaller particle size made that drench more efficacious. Dips against lice and keds were evaluated and blowfly strike became another emerging issue. Phenothiazine was in widespread use then, being a precursor to the modern, selectively-toxic drenches, such as thiabendazole, the application of which began in 1961 (Brown et al. Citation1961).

Tick comes to the fore again: 1968 and later

Taxonomic clarity by Hoogstraal et al. (Citation1968) showed H. bispinosa to be a species quite different from the tick present in New Zealand, with the name H. longicornis coming into use instead of H. bispinosa. Coincidentally with the revelation of this nomenclatorial distinction, farmers were starting to become concerned about ticks again (Cattle ticks … Citation1971). At that time the tick was known to have a distribution that reached as far as Waikanae on the west coast of the North Island and as far as Hastings in the east. More recently (Heath Citation2016; Lawrence et al. Citation2017), the tick has been found in scattered populations in the southern Wairarapa in the North Island, and with similarly localised populations on the West Coast of the South Island, and in Canterbury to the east and north of Christchurch (). Modelling has shown that there is potential for further expansion (Lawrence et al. Citation2017). Currently, however, apart from scattered populations outside the principal parts of its range, cattle tick distribution is much the same as the 1970s (Heath Citation1973).

Is Haemaphysalis longicornis the only tick threat?

Interest in H. longicornis in New Zealand and ticks generally has not dimmed. Many species sympatric with the cattle tick in its original range in Asia would find New Zealand and other regions with similar climatic, host and vegetation features, suitable for establishment, should they successfully invade. Heath (Citation2013) explored this possibility for New Zealand and compiled a list of 17 species that could potentially establish in New Zealand if they fulfilled a suitable set of criteria. Coincidentally, a successful invasion has happened in the USA where H. longicornis may have been present in the north east since around 2012 and by 2018 had spread to nine states on the eastern seaboard (Beard et al. Citation2018; Rainey et al. Citation2018) and to 11 by 2020 (Pritt Citation2020). The source of the founding population has not yet been established. This demonstrates how, even with knowledge and stringent biosecurity measures, ticks can ‘slip past the net’.

New Zealand recognises the risk that exotic ticks pose and these are notifiable, with Ixodidae (but not, inexplicably Argasidae), ticks of all genera (except, surprisingly Haemaphysalis) of biosecurity concern to this country (Biosecurity (Notifiable organisms) … Citation2018). The regularity with which exotic species are found on companion animals and humans justifies such concerns (Heath and Hardwick Citation2011; Heath Citation2013).

Tackling the tick today

Up to the present, a considerable body of information has accumulated, reviewed in Heath (Citation2016), adding to knowledge of biology and ecology which, when applied, provides farmers with a methodological framework to combat the parasite (see Oswald Citation2019). This was found especially important for deer farming as these animals were becoming increasingly managed as livestock after 1968, with the first licence granted in 1969, but with 1540 farms by 1980 (Drew Citation2008). Myers (Citation1924) did not record ticks from deer but they had been known on that host at least since the 1960s (Andrews Citation1964). Deer were found to be especially prone to tick infestations (Neilson and Mossman Citation1982; Roper Citation1987) and, from a behavioural point of view, not as easy to manage as cattle and sheep, especially where acaricide application was concerned (Heath et al. Citation1988). It is disappointing however, that even with the passage of a century and scientific efforts, ways to manage cattle tick still centre on time-honoured techniques employed by farmers in the early twentieth century; dipping and grazing management. The reason lies largely with the wide host range of H. longicornis, as well as its prolificacy, and the impossibility of eliminating innumerable ticks from vast tracts of farmland and bush, and from wild animals that support tick populations. Extension material such as that given by Oswald (Citation2019) provides practical knowledge and guides farmers’ efforts, and it is still necessary in the absence of the fabled ‘silver bullet’.

Biological control

In addition to the characteristics outlined above, this tick poses a challenge for farmers because of its 3-host life cycle, and the disproportionate amount of time spent off the host (ca. 80% of life cycle) compared with feeding times on the host. That means that acaricides (dipping) are not particularly effective at reducing the total tick population. The large range of mammalian and avian hosts for the tick also ensures that all stages can be dispersed widely throughout the environment to acquire a blood meal with little difficulty. In the early days it was thought that birds would be able to keep tick numbers down and various species such as the New Zealand pipit (known then as a ground lark; Anthus novaeseelandiae), common starling (Sturnus vulgaris) and song thrush (Turdus philomelos) had been seen either eating ticks on the ground or taking them direct from cattle (New Zealand Herald, Auckland, January 20, Citation1934, p. 23).

Reference to egrets as tick predators in Africa was made by Myers and Atkinson (Citation1924) who responded with scorn to a suggestion that such a bird be introduced to New Zealand to combat H. longicornis, the authors being strongly opposed: ‘ … to “acclimatization” in any form’.

In addition to dipping and importation of predators, a suggestion was made (Manawatu Times, Palmerston North, 9 January Citation1926, p. 11) that the starling, then a protected bird, be encouraged to breed in large numbers so as to be available to pick ticks off cattle. An astounding assertion was made in Druett (Citation1983, p. 113) that: ‘ … the sparrow helped greatly in ridding North Auckland of cattle ticks’. There were no data given to support this view and the fact that H. longicornis is still widespread in North Auckland suggests there is nothing behind the claim. Today, control of cattle tick still relies on pasture management and grazing strategies, combined with judicious and timely use of chemicals (Oswald Citation2019).

What could come?

By virtue of its isolation and stringent quarantine procedures, New Zealand has been able to keep free of most of the diseases that are actually or potentially vectored by H. longicornis. The list now is worrying long and includes: Theileria spp. (other than that species already present), Babesia spp., Anaplasma spp., Coxiella burnetii, Rickettsia spp., (Heath Citation2002), Francisella tularensis (Wang et al. Citation2018),Tick-borne encephalitis virus (Yun et al. Citation2012), the virus of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (SFTS; Luo et al. Citation2015; Jung et al. Citation2019), Thogoto virus (Talactac et al. Citation2018) and meat allergy in humans following a tick bite (Chinuki et al. Citation2016). The question of whether the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi can be transmitted by H. longicornis is in question, with some authors listing the tick as a vector (Yu et al. Citation2015), and more recent work establishing that H. longicornis is unable to act in that capacity (Breuner et al. Citation2020).

Enhanced border protection measures and exclusion of live animal imports will be the main barriers against additional tick-borne diseases entering New Zealand. The cattle tick itself has the potential to become slightly more widely distributed (Heath Citation2016; Lawrence et al. Citation2017), and also more numerous under long-term climate change that could bring favourable bioclimatic conditions (higher rainfall and temperatures) to parts of New Zealand that are currently unfavourable. At present these regions are too dry at times critical to the tick’s reproductive cycle, or have a mean annual temperature that is either too low to meet the development threshold, or prolongs diapause and questing, such that water balance becomes fatally low. Should favourable bioclimatic needs be met however, there is no reason why the tick could not make slight incursions into more of the east coast and central parts of the North Island, and more of Canterbury and Southland. Seasonal activity could be prolonged in current highly favourable regions, and reproductive potential (and thus numbers) enhanced.

Such changes would add further to economic burdens of livestock farming and, given the difficulty inherent in vaccine development (particularly for a three-host tick that spends only a brief time on the host) and tick control in general (see Aguirre et al. Citation2015), which relies still on acaricides and pasture and grazing management, the future will still present challenges.

Conclusions

It is now well over a century since H. longicornis was first found in New Zealand, and almost 100 years since the first regulations governing its control and management were promulgated. It is safe to say that a considerable amount of knowledge has accumulated about its biology, ecology, physiology and vector potential, and its genomic details have been largely revealed (Guerrero et al. Citation2019). This finding may provide promise of a vaccine (Aguirre et al. Citation2015) that could protect livestock for life against this intractable parasite, to replace the still blunt instruments of chemical control and pasture management, and to reduce substantially, if not forever, the economic and welfare impacts the tick imposes.

Acknowledgements

Deirdre Congdon (AgResearch Ltd, Ruakura, Hamilton) and Joy Dick (AgResearch Ltd, Grasslands, Palmerston North) provided considerable help in obtaining many references. Dr Brian Michael Fitzgerald (Stokes Valley, Wellington), Kevin Lawrence (Massey University, Palmerston North), Ricardo Palma (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington) are thanked for reading and commenting on an earlier draft. Iain McLachlan, Veterinary Council of New Zealand, is thanked for his help in the search for records of Joseph Lyons. Two anonymous referees made helpful comments and suggested improvements. No external funding was sought in the preparation of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aguirre A, Garcia MV, Szabó MPJ, Barros JC, Andreotti R. 2015. Formula to evaluate efficacy of vaccines and systemic substances against three-host ticks. International Journal for Parasitology. 45:357–359.

- Amending regulations. 1923. Amending regulations under the Stock Act, 1908, for the prevention of the spread of ticks (Ixodidae) among cattle. Notice No. Ag.2293. The New Zealand Gazette, number 68, 13 September 1923, 2387–2387.

- Andrews JRH. 1964. The arthropod and helminth parasites of red deer (Cervus elaphus L.) in New Zealand. Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 5:97–121.

- Anon. 1919. The cattle tick pest. Bulletin No. 13, Melbourne, Institute of Science and Industry, The Executive Committee of the Advisory Council. 40pp.

- Arnold EH. 1953. Some sub-tropical and other grasses in Northland. Proceedings of the New Zealand Grasslands Association. 15:79–89.

- Ashburton Guardian. 1892. Farm notes. Ashburton Guardian, April 22, p. 2. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Aston BC. 1922. Chemistry Section, pp. 15–16, Department of Agriculture. Annual Report for 1921–22. Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session I, volume 2, section H-29. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Auckland Star. 1896. New Zealand Government Veterinary. Auckland Star, September 29, p. 5. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Auckland Star. 1921. Cattle tick. Proposed regulations. Auckland Star, May 11, p. 5. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Auckland Star. 1925. Cattle tick menace. Auckland Star, January 24, p. 7. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Barker SC, Walker AR. 2014. Ticks of Australia. The species that infest domestic animals and humans. Zootaxa. 3816:1–144.

- Barry WC. 1934. Live-stock Division. Department of Agriculture Annual Report for 1933–34, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session I, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 13–20. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Barry WC. 1936. Live-stock Division. Department of Agriculture Annual Report for 1935–36, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session I, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 19–26. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Barry WC. 1937. Livestock Division, Department of Agriculture Annual Report for 1936–37, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session I, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 6–14. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Barry WC. 1938. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture Annual report for 1937–38: Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session 1, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 9–21. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Barry WC. 1939. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture Annual Report 1938–39, p. 9. Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session 1, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 9–22. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Barry WC. 1940. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture Annual Report 1939–40, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session 1, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 5–15. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Barry WC. 1941. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture Annual Report 1940–41, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session 1, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 5–17. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Beard CB, Occi J, Bonilla DL, Egizi AM, Fonseca DM, Mertins JW, Backenson MS, Bajwa WI, Barbarin AM, Bertone MA, et al. 2018. Multistate infestation with the exotic disease-vector tick Haemaphysalis longicornis-United States, August 2017–September 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 67(47):1310–1313. US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Checklist Committee (O.S.N.Z.) Gill BJ (Convener), Bell BD, Chambers GK, Medway DG, Palma RL, Scofield RP, Tennyson AJD, Worthy TH. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th ed. Wellington: Ornithological Society of New Zealand & Te Papa Press; x+501 pp.

- Biosecurity (Notifiable organisms). 2018. Biosecurity (Notifiable organisms) Order 2016. Reprint as at 10 September 2018. 11 pp. file:///C:/Users/User/Documents/Notifiable%20organisms.pdf. From: Biosecurity New Zealand. [accessed 2019 Nov 2]. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/protection-and-response/finding-and-reporting-pests-and-diseases/registers-and-lists/ Last reviewed 27 June 2019.

- Bishop DM, Heath ACG. 1998. Host-parasite checklist for ectoparasites of New Zealand birds. Surveillance. 25(Special Issue):13–31.

- Breuner NE, Ford SL, Hojgaard A, Osikowicz LM, Parise CM, Rizzo MFR, Bai Y, Levin ML, Eisen RJ, Eisen L. 2020. Failure of the Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, to serve as an experimental vector of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases. 11:101311. 6pp. DOI:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.101311.

- Brown HD, Matzuk AR, Ilves IR, Peterson LH, Harris SA, Sarett LH, Egerton JR, Yakstis JA, Campbell WC, Cuckler AC. 1961. Antiparasitic drugs, IV. 2-(4′-thiazolyl)-benzimidazole, a new anthelmintic. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 83:1764–1765.

- Bruce Herald. 1893. Texas fever. Bruce Herald, May 16, p. 4. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Cattle-tick regulations. 1919. Cattle-tick regulations. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture. 19:263–263. See also: The New Zealand Gazette, no. 119, 2 October 1919, 3040–3041.

- Cattle-tick regulations. 1922. Cattle-tick regulations. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture. 24:188–191. See also: The New Zealand Gazette, no. 10, 16 February 1922, 470–473.

- Cattle-tick regulations. 1923. Cattle-tick regulations. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture. 26:130–130.

- Cattle ticks. 1971. Cattle ticks Increasing. New Zealand Farmer. 91:23–24.

- Chinuki Y, Ishiwata K, Yamaji K, Takahashi H, Morita E. 2016. Haemaphysalis longicornis tick bites are a possible cause of red meat allergy in Japan. Allergy. 71:421–425. DOI:10.1111/all.1280.

- Choi C-Y, Kang C-W, Kim E-M, Lee S, Moon K-H, Oh M-R, Yamauchi T, Yun Y-M. 2014. Ticks collected from migratory birds, including a new record of Haemaphysalis formosensis, on Jeju Island. Korea. Experimental and Applied Acarology. 62:557–566. DOI:10.1007/s10493-013-9748-9.

- Cock MJW, Bennett FD. 2011. John Golding Myers (1897–1942), an extraordinary exploratory entomologist. CAB Reviews. 6:1–18.

- DDT. 2019. DDT. Wikipedia. Last edited 8 October 2019. [accessed 2019 Oct 16]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DDT.

- Drew K. 2008. Deer and deer farming. Te Ara-The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. [accessed 2019 Sep 28]. https://teara.govt.nz/en/deer-and-deer-farming/print.

- Druett J. 1983. Exotic intruders. The introduction of plants and animals into New Zealand. Auckland: Heinemann Publishers. vi+291pp.

- Egizi A. 2018. Entomological Society of America. Proposal form for a new common name or change of ESA-approved common name, 17 August 2018. 5 pp. https://www.entsoc.org/sites/default/files/files/Asian%20longhorned%20tick_August%202018.pdf.

- Estrada-Peña A, Venzal JM, Nava S, Mangold A, Guglielmone AA, Labruna MB, de la Fuente J. 2012. Reinstatement of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) australis (Acari: Ixodidae) with redescription of the adult and larval stages. Journal of Medical Entomology. 49:794–802. DOI:10.1603/ME11223.

- Evening Post. 1919. The cattle tick, scientific investigation. Evening Post, April 19, p. 9. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Evening Post. 1930. Nature notes. Cattle ticks on birds? Evening Post, April 19, p. 13, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Evening Post. 1940. Cattle tick regulations. Evening Post, July 18, p. 15. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Evening Post. 1943. Department of Agriculture. Mr. E.J. Fawcett appointed. Evening Post, January 14, p. 4. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Fawcett EJ. 1953. Animal Industry Division Report, pp. 73–90. In: Annual Report of the Director-General of Agriculture for the Year ended 31 March 1953.

- Fawcett EJ. 1955. Animal Industry Division Report, pp. 101–128. In: Annual Report of the Director-General of Agriculture for the Year ended 31 March 1955.

- Fawcett EJ. 1956. Animal Industry Division Report, pp. 109–138. In: Annual Report of the Director-General of Agriculture for the Year ended 31 March 1956.

- Filmer JF. 1949. Parasitology, pp. 88–90, In: Animal Research Division, pp. 69–94. Department of Agriculture Annual Report for year 1948–49. Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session 1, volume 3, section H-29. http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Gilruth JA. 1912. The introduction and spread of the cattle tick (Boophilus annulatus var. microplus) and of the associated disease tick fever (Babesiosis) in Australia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 25, Part I, 15–22.

- Graham R. (chair). 1861. Report and Evidence of the Select Committee on Pleuro-Pneumonia. Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, session I, volume 1, section F-01, pp. 1–9. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Guerrero F, Bendele KG, Ghaffari N, Guhlin J, Gedye KR, Lawrence KE, Dearden PK, Harrop TW, Heath ACG, Lun Y, et al. 2019. The Pacific Biosciences de novo assembled genome data set from a parthenogenetic New Zealand wild population of the longhorned tick. Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann, 1901. Data in Brief 27, 104602, 6pp. DOI:10.1016/j.dib.2019.104602.

- Guglielmone AA, Robbins RG, Apanaskevich DA, Petney TN, Estrada-Peña A, Horak IG. 2014. The hard ticks of the world (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae). Heidelberg: Springer Dordrecht. 738pp.

- Heath ACG. 1973. Ticks on cattle and sheep. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture. 127(2):64–67.

- Heath ACG. 2002. Vector competence of Haemaphysalis longicornis with particular reference to blood parasites. Surveillance. 29:12–14.

- Heath ACG. 2010a. A review of ectoparasites of Apteryx spp. (kiwi) in New Zealand, with new host records, and the biology of Ixodes anatis (Acari: Ixodidae). Tuhinga. 21:147–159.

- Heath ACG. 2010b. Checklist of ectoparasites of birds in New Zealand: additions and corrections. Surveillance. 37:12–17.

- Heath ACG. 2013. Implications for New Zealand of potentially invasive ticks sympatric with Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann, 1901 (Acari: Ixodidae). Systematic and Applied Acarology. 18:1–26.

- Heath ACG. 2016. Biology, ecology and distribution of the tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann (Acari: Ixodidae) in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 64:10–20.

- Heath ACG, Hardwick S. 2011. The role of humans in the importation of ticks to New Zealand; a threat to public health and biosecurity. New Zealand Medical Journal. 124: 16 pp. https://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/124-1339/4785/

- Heath ACG, Palma RL. 2016. A re-examination of doubtful New Zealand tick records: lost species, misidentifications or contamination? New Zealand Entomologist. 39:79–90.

- Heath ACG, Palma RL. 2017. A new species of tick (Acari: Ixodidae) from seabirds in New Zealand and Australia, previously misidentified as Ixodes eudyptidis. Zootaxa. 4324(2):285–314.

- Heath ACG, Palma RL, Cane RP, Hardwick S. 2011. Checklist of New Zealand ticks (Acari: Ixodidae, Argasidae). Zootaxa. 2995:55–63.

- Heath ACG, Wilson PR, Roberts HM. 1988. Evaluation of the efficacy of flumethrin 1% pour-on against the New Zealand cattle tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, on farmed red deer, using laboratory-reared ticks. Veterinary Medical Review. 59:23–27.

- Hoogstraal H, Lim B-L, Anastos G. 1969. Haemaphysalis (Kaiseriana) bispinosa Neumann (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae): evidence for consideration as an introduced species in the Malay peninsula and Borneo. The Journal of Parasitology. 55:1075–1077.

- Hoogstraal H, Roberts FHS, Kohls GM, Tipton VJ. 1968. Review of Haemaphysalis (Kaiseriana) longicornis, Neumann (resurrected) of Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia, Fiji, Japan, Korea, and Northeastern China and USSR and its parthenogenetic and bisexual populations (Ixododea: Ixodidae). Journal of Parasitology. 54:1197–1213.

- Horowhenua Chronicle. 1930. Seagull proved to be cattle tick host. Horowhenua Chronicle, March 25, 1930, p. 6. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Horowhenua Chronicle. 1936. Advertisements, Horowhenua Chronicle, February 11, p. 4, column 3). https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Hoy JM. 1965. David Miller-entomologist. The New Zealand Entomologist. 3(4):3–7.

- James M, Saunders B, Guy L, Brookbanks E, Charleston W, Uilenberg G. 1984. Theileria orientalis, a blood parasite of cattle. First report in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 32:154–156.

- Jung M, Kho J-W, Lee W-G, Roh JY, Lee D-H. 2019. Seasonal occurrence of Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae) and Haemaphysalis flava, vectors of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) in South Korea. Journal of Medical Entomology. 20:1–6. DOI: 10.1093/jme/tjz033.

- Kim HC, Chong ST, Choi CY, Nam HY, Chae HY, Klein TA, Robbins RG, Chae J-S. 2016. Tick surveillance, including new records for three Haemaphysalis species (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from migratory birds during 2009 on Hong Island (Hong-do), Republic of Korea. Systematic and Applied Acarology. 21:596–606. DOI:10.11158/saa.21.5.4.

- Kirk T. 1896. On the products of a ballast-heap. Transactions of the New Zealand Institute. 28:501–507.

- Lake County Press. 1901. Anglo-colonial notes. Lake County Press, March 14, p. 2. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Lawrence KE, Summers SR, Heath ACG, McFadden AMJ, Pulford DJ, Tait AB, Pomroy WE. 2017. Using a rule-based envelope model to predict the expansion of habitat suitability within New Zealand for the tick Haemaphysalis longicornis, with future projections based on two climate change scenarios. Veterinary Parasitology. 243:226–234.

- LeS DH. 1975. Obituary, J.E. McIlwaine. New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 23:71–71.

- Luo L-M, Zhao L, Wen H-L, Zhang Z-T, Liu J-W, Fang L-Z, Xue Z-F, Ma D-Q, Zhang X-S, Ding S-J, et al. 2015. Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks as reservoir and vector of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in China. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 21:1761–1767. DOI:10.3201/eid2110.150126.

- Lyons J. 1926. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture Annual Report 1925–26, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session I, volume 2, section H-29, pp. 11–20. http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Lyons J. 1927. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture Annual Report 1926–27, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session I, volume 2, section H-29, pp. 15–25. http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Lyons J. 1928. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture Annual Report 1927–28, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session 1, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 13–27. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Lyons J. 1929. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture. Annual Report for 1928–29, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Session 1, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 13–23. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Lyons J. 1930. Live-stock Division. Department of Agriculture. Annual Report for 1929–30, Appendix to the House of Representatives, Session I, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 12–19. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Lyons J. 1931. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture. Annual Report for 1930–31, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Sessions I-II, volume 2, section H-29, pp. 9–16. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Lyons J. 1932. Live-stock Division, Department of Agriculture. Annual Report for 1931–32, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, Sessions I–II, volume 3, section H-29, pp. 9–16. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.