ABSTRACT

This paper proposes an alternative typology of contract farming arrangements (CFA) based on transaction cost theory. To construct the typology, we first surveyed managers of agribusiness firms and contracted farmers in Zimbabwe to understand the provisions in their contracts, the motivations for their inclusion and the level of transaction attributes, particularly the sub-categories of asset specificity and uncertainty. We then developed a two-by-two matrix of contract types based on the interaction of transaction attributes. The results show that four contract types can be distinguished: total, group, lean and market contracts. Furthermore, CFAs that are misaligned with transaction attributes have problems of side-selling and inefficiency. Our new empirically based categorisation can help managers and policymakers to design CFAs that match with underlying transaction attributes, thus enhancing the stability and efficiency of CFAs.

1. Introduction

Agribusiness firms requiring a consistent supply of high quality agricultural raw materials have widely adopted contract farming as the dominant approach to coordinate their supply chains. Contract farming can be defined as an institutional arrangement under which an agribusiness firm contracts the production of agricultural commodities out to farmers (Bellemare and Novak Citation2017). The trend towards contract farming is also evident in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where the institutional arrangement is considered a mechanism for helping farmers to overcome pervasive market failures. Indeed, recent estimates based on multi-country surveys suggest that about 5% of smallholder farmers in SSA are involved in contract farming arrangements (CFAs) and the number is increasing (Reardon et al. Citation2019).

Empirical studies in developing countries emphasise the diversity of CFAs (e.g., Kirsten and Sartorius Citation2002; Vermeulen et al. Citation2008; Bellemare and Lim Citation2018). To structure the analysis of these varied forms of CFAs, various typologies have been proposed in the literature. The commonly used typology was developed by Mighell and Jones (Citation1963) who distinguished between market-specification, production-management, and resource-providing contracts. However, this typology has been criticised for not capturing the diversity of contemporary CFAs (Hueth et al. Citation2007; Swinnen and Maertens Citation2007). Furthermore, as Mighell and Jones admit, “The boundaries of these groups are not precise. It may be difficult to decide where to place a particular contract” (14). The purpose of this study is to demonstrate that the use of transaction cost analysis can contribute to a better classification of modern CFAs. The study takes an agribusiness firm perspective, as CFAs are usually instigated and designed by agribusiness firms (Key and Runsten Citation1999; Bijman Citation2008; Jaffee et al. Citation2011).

The specific objectives of the study are: (1) to identify provisions in contemporary agricultural contracts; (2) to explore the determinants of observed contract provisions; (3) to match transaction characteristics with variations in contract provisions; and (4) develop a CFA typology based on correlates of contract provisions and transaction attributes. To achieve these objectives, a conceptual framework based on transaction cost theory (TCT) is first constructed for the purpose of developing the most appropriate contract type with an agribusiness partner. Secondly, the framework is tested through the analysis of contract data obtained through surveys among agribusiness firms and farmers. Third, a CFA typology is developed, based on the observed variations in provisions and transaction characteristics. The study focuses on agricultural sectors in which the contracts show significant variation in their structures, thus making it possible to capture the diversity of CFAs.

The study aims to contribute to the literature by using a transaction cost framework as an approach to differentiate and classify contemporary CFAs. This is a departure from the dominant Mighell and Jones (Citation1963) typology which does not explicitly link transaction costs to contract types. Second, this study extends the work of Bellemare and Lim (Citation2018) who simply describe the various forms CFAs can take. Third, the study will build on the work of Kirsten and Sartorius (Citation2002) and Sartorius and Kirsten (Citation2005, Citation2007) who matched transaction cost characteristics (asset specificity, uncertainty and transaction frequency) to generic governance structures proposed by Williamson (Citation1979). The present study takes a step further by identifying contract provisions and relating them to transaction characteristics. Finally, the study contributes a further perspective to the operationalisation of TCT in agricultural settings; an approach is complementary to Williamson (Citation2000), Kirsten and Sartorius (Citation2002) and Sartorius and Kirsten (Citation2005, Citation2007).

A focus on transactions is logical as transaction costs are the underlying reason agribusiness firms and farmers engage in CFAs (Hobbs and Young Citation1999; Key and Runsten Citation1999). In this regard, a TCT-based typology of CFAs can help managers of agribusiness firms to select an appropriate CFA for known transaction characteristics. The importance of selecting the right CFA is underlined by the high failure rate of the institutional arrangement in developing countries (Sartorius and Kirsten Citation2007; Barrett et al. Citation2012). Indeed, a few studies that document failed CFAs (e.g., Baumann Citation2000; Eaton and Shepherd Citation2001) suggest that a mismatch between transaction characteristics and the CFA may partly explain the high failure rate.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows. Section 2 develops the transaction cost framework that will be applied to the analysis of the case studies. Section 3 presents methods and data. Section 4 presents the results, discussion and proposes the alternative typology of CFAs. Section 5 concludes.

2. Transaction cost framework

The objective of this section is to develop a framework that permits the differentiation and classification of contemporary CFAs. In this regard, the transaction costs facing agribusiness firms in modern agrifood chains are first discussed before a conceptual framework is developed.

2.1 Agribusiness firm transaction costs in modern agrifood chains

The cost of carrying out exchange between a buyer and a seller are called transaction costs. In the context of agri-food value chains, transaction costs occur prior (ex ante) and after (ex post) the agribusiness firm and the farmer physically exchange the agricultural commodity. Ex ante costs comprise search and screening costs involved in identifying and assessing potential growers on their ability and willingness to produce under contract. These costs can take various tangible forms such as staff time, travel and communications costs. Bargaining costs, which include time spent on negotiating the agreement and legal fees in drawing up and signing contracts, are also a type of ex ante transaction costs. Ex post transaction costs, on the other hand, are incurred in coordinating production, harvesting, delivery, and processing, as well as monitoring and enforcing compliance with the agreement. Furthermore, insurance costs, investments in measurement devices, storage, and handling costs are incurred when transferring physical possession and ownership of the product. Transaction costs arise because of the existence of asymmetric information, bounded rationality, and the possibility of opportunistic behaviour (Williamson Citation1985).

Williamson (Citation1979) asserts that transaction costs are a function of asset specificity, uncertainty and transaction frequency. Asset specificity refers to the degree to which durable investments are unique to certain activities such that they cannot be redeployed to other uses without significant loss of value. Uncertainty, on the other hand, refers to behavioural and/or environmental disturbances to which transactions are exposed to. Lastly, transaction frequency refers to the repetitiveness of transactions between contracting parties, which can be one-off, occasional, or recurrent.

TCT suggests that the interaction of asset specificity, uncertainty and transaction frequency determines the level of transaction costs and therefore the choice of governance structures, which are the set of rules by which an exchange is carried out (Williamson Citation1985). A CFA can be conceptualised as a specific form of a governance structure whose main function is to economise on the sum of transaction and production costs.

Drawing on Williamson’s (Citation1985) original framework, this paper primarily examines the impact of the interaction of asset specificity and uncertainty on CFAs. The effect of transaction frequency on governance structures is not analysed separately in this study because it remains somewhat ambiguous. According to Williamson’s (Citation1979) interpretation, highly frequent transactions are associated with hierarchical governance because the repeated cost of enacting contracts would be excessive in conditions of opportunism and information asymmetry. An alternative interpretation, however, is that highly frequent transactions build trust among contracting parties such that spot market transactions or self-enforcing contracts would suffice (Weseen et al. Citation2014). In this view, frequent transactions lead to market governance. Considering these opposing views, we conclude that an assessment of the effect of the transaction frequency on governance structures must be taken in the context of the other two transaction characteristics: uncertainty and asset specificity, which are widely considered the primary drivers of transaction costs (Williamson Citation1979, Citation1985; Jaffee Citation1995; Ménard Citation2004; Bijman et al. Citation2011; Weseen et al. Citation2014).

2.1.1 Transaction costs related to asset specificity in modern agrifood chains

According to Williamson (Citation1988), asset specificity takes several forms, including site, physical, dedicated, human, temporal and brand capital specificity. Asset specificity creates hold-up problems where one party to a contract can expropriate the returns from an investment made by its transacting partner (Williamson Citation1975, Citation1976). Asset specificity leads to the need to craft safeguards, which entails increased transaction costs. However, not all types of specific assets are equally relevant as to cause hold up problems in agricultural transactions (Masten Citation2000). For instance, even though human skills necessary for participation in modern agrifood chains can be very specialised, they are largely re-deployable in transactions with different contractual partners. The most relevant types of specific assets for our purpose are physical, temporal, and brand name capital.

Physical asset specificity refers to investments in specialised equipment that are designed for a particular transaction and have limited value outside the specific relationship. Modern agri-food chains involve high physical asset specificity due to the proliferation of private standards in recent decades (Henson et al. Citation2011) and the adoption of quality differentiation as a competitive strategy by wholesalers and retailers (Kirsten and Sartorius, Citation2002). Private quality standards such as hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP) systems, for example, often require to be customised to the buyers’ requirements, thus implying more specificity of assets (Martino and Perugini Citation2006). Likewise, the requirement by European retailers for suppliers of perishables in developing countries to have GLOBALGAP certification involves significant asset specificity as the agribusiness firm may not be able to quickly find alternative qualified producers, thus increases its switching costs (Reardon and Zilberman Citation2018).

Temporal asset specificity relates to transactions where timing and coordination are important. Most agricultural transactions have high temporal asset specificity because they are perishable and are harvested seasonally (Masten Citation2000). Thus, their value is highly dependent on reaching the user within a limited period. Here, the risk for the agribusiness firm is that the farmer, knowing that timely performance is critical, may deliberately withhold delivery as a strategy to renegotiate the contract and thereby extract additional gains from the transaction. Such hold-up problems are highly relevant in modern agrifood chains given that the bulk of exports from developing countries are fresh food products such as meat, fresh fruits and vegetables (Kirsten and Sartorius Citation2002; Henson et al. Citation2011; Ajwang Citation2019). In domestic markets, the rise of supermarkets and large processors, coupled with preference for processed and fresh foods (Tschirley et al. Citation2015) similarly imply high temporal asset specificities and hold up problems.

Lastly, brand name specificity refers to the agribusiness firm’s investment in reputation. Owning brands increases transaction costs as the agribusiness firm has to craft safeguards, such as monitoring routines and measurement devices, to prevent the farmer from damaging the brand reputation.

2.1.2 Transaction costs related to uncertainty in modern agrifood chains

Uncertainty is widely considered to be the most important determinant of governance structures in modern food chains (Masten Citation2000; Abebe et al. Citation2013; Martino and Frascarelli Citation2013). The presence of uncertainty increases the possibility of opportunistic behaviour in transactions (Williamson Citation1975). High uncertainty increases transaction costs because the agribusiness firm must develop safeguards to guarantee itself adequate supplies of quality raw produce.

Two forms of uncertainty that can be discerned in the literature are environmental and behavioural uncertainty (Li et al. Citation2018). Environmental uncertainty relates to the inability to predict the quantity and quality of outputs due to uncontrollable factors such as weather effects and pests, but also due to rapid market changes. Agricultural transactions involve high environmental uncertainty because of the biological nature of production which makes it impossible to precisely control, and therefore, forecast the volume and quality of production (Bogetoft and Olesen Citation2002). Agricultural transactions also involve high uncertainty due to the perishability and seasonality of products. Furthermore, rapidly changing consumer tastes increase uncertainty in output markets as the agribusiness firm cannot accurately forecast demand. Finally, environmental uncertainty arises due to food safety and quality standards which are constantly changing and becoming more stringent. Complying with these standards implies increased coordination cost as food safety failures can have deleterious consequences to the agribusiness firm in terms of legal liability, reputational damage, consumer confidence and future earnings (Fulponi Citation2006).

Behavioural uncertainty emerges because contracting parties may behave opportunistically. This is a key issue in modern agrifood chains because agricultural products are now increasingly valued for specific attributes and for the practices used in their production (Kirsten and Sartorius Citation2002; Bijman et al. Citation2011). Such products pose performance measurement difficulties as the seller has an informational advantage and may gain from quality cheating (Raynaud et al. Citation2009; Bijman et al. Citation2011). Transaction costs resulting from this measurement problem include searching, screening, selection and monitoring costs.

2.2 A conceptual framework for classifying contemporary CFAs

A conceptual framework for differentiating and classifying contemporary CFAs is developed as follows. First, reference is made to the conclusions of Williamson (Citation1979) as shown in . The table shows that the agribusiness firm seeks to economise the sum of its production and transaction costs by selecting an appropriate contract type: classical, neo-classical, bilateral relational or unified relational contract. The choice of contract type is dependent on the conditions of the exchange relationship.

Table 1. Economising transaction costs.

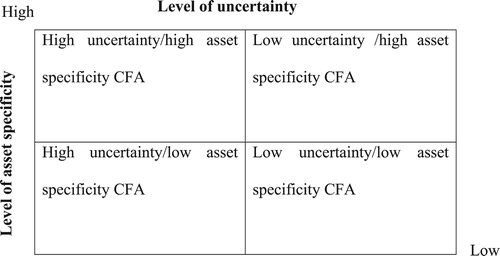

An assignment of agricultural contracts to Williamson’s (Citation1979) contract categories, however, only permits a rough and imprecise classification. For instance, boundaries between neoclassical and relational contracts are blurred (Drescher Citation2000). To improve on the framework, reference is made to Williamson (Citation1985, 60) who asserted that “ … the interaction effects between uncertainty and asset specificity are important to an understanding of economic organization”. If asset specificity and uncertainty can be high or low, a two-by-two matrix of CFAs emerges ().

Figure 1. Interaction of transaction attributes. Source: Based on Williamson (Citation1985).

Finally, the conceptual framework is developed by matching governance structures in with transaction attributes in using TCT, as shown in . For example, high asset specificity/high uncertainty transactions can be matched to Williamson’s (Citation1979) unified relational contracting in line with TCT where hierarchical or hierarchy-like governance is predicted. Additionally, each transaction attribute is broken down into sub-categories as explained in sub-sections 2.1.1 and 2.1.2. The sub-categories are allocated equal weight, except for brand name capital asset specificity which is allocated more weight as it implies tangible (e.g., investments in promotion and product quality) and intangible value such as goodwill (Raynaud et al. Citation2009).

Table 2. Conceptual framework.

How intensive is the vertical coordination under each governance structure and why? Four propositions are put forward based on the literature.

2.2.1 High asset specificity/High uncertainty transactions

TCT suggests that high levels of asset specificity and uncertainty will lead to hierarchical control because the risk of opportunism and information asymmetry is much higher (Williamson Citation1979). Accordingly, it is expected that high asset specificity/high uncertainty transactions will be governed by detailed specifications in written contracts, which essentially “produce the effects of hierarchies” (Stinchcombe Citation1985, 165). Thus, the following proposition is made:

P1. High asset specificity/ high uncertainty transactions will be governed by hierarchy-likeFootnote1CFAs.

2.2.2 Low asset specificity/Low uncertainty transactions

TCT suggests that low levels of asset specificity and uncertainty leads to market coordination because of the low potential for opportunism and information asymmetry (Williamson Citation1979). Accordingly, simple written, oral or informal contracts with few provisions are expected, and price incentives will be the dominant coordinating mechanism. Following Sartorius and Kirsten (Citation2005, Citation2007), the following proposition is made:

P2. Low asset specificity/low uncertainty transactions will be governed by market-likeFootnote2 CFAs.

2.2.3 High asset specificity/Low uncertainty transactions

TCT suggests that high levels of asset specificity tend to make the investing party wary of hold-up by the non-investing party (Williamson Citation1985). Producer organisations and cooperatives may be preferred to prevent hold-up in agriculture because they can pool resources to make reciprocal investments, which raise the exit costs for farmers (Gow and Swinnen Citation1998). As such, it is expected that high asset specificity/low uncertainty transactions will be governed by bilateral relational structures or farmer groups which rely on peer pressure, trust and socially embedded relationships for coordinating transactions. Accordingly, it is postulated as follows:

P3. High asset specificity/ low uncertainty transactions are coordinated by contracts with farmer groups.

2.2.4 Low asset specificity/High uncertainty transactions

High uncertainty makes it more difficult for the buyer to predict the supplier’s actions (Williamson Citation1975). When uncertainty is significant in a low-asset specificity transaction, the buyer will be reluctant to commit to a long-term relationship or to enter into interlocking contracts due to high risk of opportunism and information asymmetry. For example, Repar et al. (Citation2018) show how, faced with high behavioural opportunism, price and environmental uncertainty, a paprika buyer in Malawi reduced the input provision to the minimum to reduce the risk of financial loss. Accordingly, it is proposed as follows:

P4. Low asset specificity/high uncertainty transactions will be governed CFAs with no or minimum inputs.

3. Methods and data

3.1 Research method

A collective case study design (Stake Citation1995) was chosen because this approach allows researchers to study multiple cases jointly to examine a phenomenon. Moreover, a collective case study enables simultaneous cross-case analysis to be undertaken to discern patterns across cases, thereby increasing the potential for generalising beyond particular cases (Yin Citation2003).

The study was exploratory in nature. First, a desk review of publicly available literature on CFAs in Zimbabwe was conducted to understand the spread of contract farming, the contracted commodities, and the agribusiness firms involved. Following the desk study, interviews were held with four consultants who participated in two recent donor-funded surveys on the state of contract farming in Zimbabwe. The consultants introduced the authors to key managers in agribusiness firms. Lastly, three expertsFootnote3 were interviewed to triangulate data obtained from the desk study and interviews with consultants. Following the desk study and expert interviews, eight agribusiness firms engaged in contract farming in the tomato and wheat sectors were selected for in-depth study. The main criteria used to select the case studies are (i) heterogeneity of contract types; (ii) heterogeneity of agribusiness firms and farmers (small, medium or large-scale); and (iii) access to accurate contract data.

presents a summary of the eight case studies. The tomato sector is an interesting case study because the impacts of safety and quality standards are most evidently played out in the fresh produce sector in SSA (Henson et al. Citation2011). Concerning the wheat sector, increased incomes, urbanisation and trends towards supermarket bakeries in SSA are leading to high demand for wheat with specific quality attributes, such as longer shelf-life and texture (Tadesse et al. Citation2018), making contracts in the sector interesting for our study.

Table 3. Wheat and tomato contracting firms in Zimbabwe.

For confidentiality reasons, four case firms involved in contracting in wheat production are referred to as Case 1, 2, 3 and 4, while tomato case firms are referred to as Case 5, 6, 7 and 8.

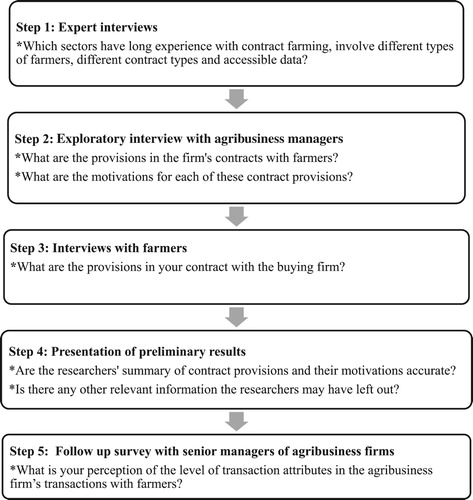

3.2 Data collection

Data was collected through face-to-face interviews with agribusiness firm managersFootnote4 and farmers in 2015. We first developed and pilot tested an interview protocol to clarify, prioritise and ensure consistency of questions across respondents and then used semi-structured questionnaires to collect data. Face-to-face interviews allowed for follow up questions to be asked and for collection of examples of written contracts. A 5-point Likert scale was used to collect data on the level of transaction attributes, as described in the section below. summarises the five steps that were followed to collect data, and the main topics addressed at each step.

3.3 Data analysis and validation

Data analysis and validation were carried out as follows. Regarding the motivation for provisions in the contract, each rationale mentioned by agribusiness managers was categorised according to the conceptual framework. For instance, if a manager said the contract provides credit because it enables farmers to produce enough quantities for the processing facility, the agribusiness firm’s motivation was categorised as driven by physical asset specificity.

Case study validation was achieved by data triangulation and respondent feedback as follows. First, if the form of contract was written, the authors reviewed the document, produced a list of provisions and confirmed the accuracy of the list with agribusiness managers. In the case of oral contracts, agribusiness managers in each company were interviewed individually to develop a list of the contract provisions. Second, five farmers participating in each CFA were interviewed to confirm the information provided by the agribusiness firm. Finally, the list of contract provisions was presented to agribusiness managers in each firm for validation before analysis began.

A 5-point Likert scale in which “1” represented “low” or “strongly disagree” and “5” represented “high” or “strongly agree” was used to determine agribusiness managers’ opinions regarding the level of transaction attributes in relation to direct competitors. In addition, we also obtained USD values of the investment, where appropriate. The sub-categories of asset specificity and uncertainty were operationalised based on the literature ().

Table 4. Measures of transaction attributes.

The level of transaction attributes was analysed by computing the median response by agribusiness managers for each case study and then multiplying the score with the weight for each sub-category in line with the conceptual framework. below is an example of how the level of asset specificity for Case 1 is calculated. In the case, the median score from managers’ responses regarding the physical asset specificity of the agribusiness firm was 2.5. This is multiplied by the weight to give 0.75 as the level of physical asset specificity for the firm. Adding the scores of the three sub-categories of asset specificity gives an overall level 1.90 (out of 5), which is categorised as low because it is less than 2.5, which is the cut-off point adopted for the study.

Table 5. Measuring level of asset specificity.

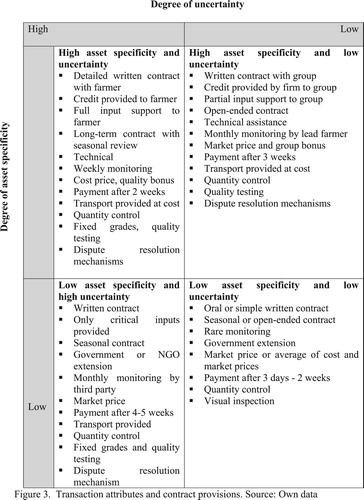

Finally, in line with the conceptual framework for this study and based on agribusiness firm managers’ perceptions of the level of transaction attributes (uncertainty and asset specificity), each contract was allocated to one of the quadrants (). The contract provisions in each contract were then analysed and summarised in the corresponding quadrants.

4. Results and discussion

This section presents and discusses the findings of the study. Sub-section 4.1 combines answers to research questions 1 (what are the provisions in contemporary agricultural contracts?) and 2 (what are the determinants of observed contract provisions?). Sub-section 4.2 provides an answer to research question 3 (how can transaction characteristics and variations in contract provisions be matched?), while sub-section 4.3 answers research question 4 by developing a transaction cost-based typology of CFAs.

4.1 Research questions 1 and 2: contract provisions and motivations

The results show that formal and informal contracts are used, sometimes simultaneously in the same CFA. In the CFAs using both forms of contract, managers explained that formal contracts were used for large and medium-scale farmers. These farmers demanded written contracts as a means to hold buying firms accountable in case of breach. They also used written contracts as collateral for crop financing from financial institutions. This finding is consistent with prior literature which shows that farmers prefer written contracts because they provide avenues for legal redress in case of buyer noncompliance (e.g., Harou and Walker Citation2010). The agribusiness firms, on the other hand, preferred informal contracts as they were less costly to administer. This is consistent with the empirical literature which highlights that agribusinesses prefer informal contracts when legal recourse is too costly (Fafchamps and Minten Citation2001) and flexibility to renege is needed such as when there is uncertainty about retail demand volumes or supplier yields (Barrett et al. Citation2012, 719).

We also found that contract provisions differ in the number and kind of specifications, depending on the interaction of transaction attributes. Thus, the intensity of vertical coordination differed markedly between CFAs. The specifications in contracts in our case studies included credit, input provision, contract duration, technical assistance, monitoring, pricing formula, payment terms, transport, contract quota, quality testing, and grading and dispute resolution. These contract provisions are consistent with findings in other studies (e.g., Eaton and Shepherd Citation2001; Kirsten and Sartorius Citation2002).

We found that a contract provision may have multiple objectives in a single CFA. For instance, while a seasonal contract could be used to cope with environmental uncertainty (by allowing the agribusinesses to make quantity or quality adjustments upon renewal), it can also be used to protect brand reputation (by terminating contracts with poor farmers at the end of the season) and to increase use of specific assets (by retaining the best producers). This finding is consistent with Bogetoft and Olesen (Citation2002) who demonstrate that a contract provision may serve several purposes such as minimising transaction costs, providing incentives, penalties, and sharing of risks.

Finally, our findings confirm that physical, brand name capital and temporal asset specificity are relevant sub-categories. For uncertainty, behavioural and environmental uncertainty are the main sub-categories of transaction attributes that shape CFAs.

4.2 Research question 3: matching transaction characteristics to contract provisions

relates the level of transaction characteristics to contract provisions. The results show that two transactions characterised by high uncertainty and high asset specificity (Cases 2 and 5) are mainly coordinated by hierarchy-like governance, thus supporting the proposition in our conceptual framework.

Table 6. Transaction characteristics and CFAs (< 2.5 = low; = / >2.5 = high).

In case 2, specific assets mainly comprise processing facilities and brand name capital. High uncertainty derives from low trust between the buyer and farmers. The low trust environment imposes additional coordination, monitoring and measurement costs for buyers supplying export markets that have strict food quality and safety standards. Agribusiness managers in the wheat sector mentioned that a key food safety issue associated with wheat is mycotoxin contamination which occurs in the field and during storage. It was mentioned that importing countries have imposed stricter standards and, in the past, commodity brokers have experienced losses due to mycotoxin contamination. Furthermore, wheat commodity brokers explained that they face high uncertainty because the observable characteristics of raw wheat (e.g., damage, cleanliness or weight) were poorly correlated with desirable end-use characteristics (e.g., protein, loaf volume or mix tolerance). The transaction costs implied by these food and safety issues and unobservability include monitoring and measurement costs.

Case 5 specific assets include machinery used in tomato paste, peeled tomato, pulp, tomato sauce, and ketchup production. The firm sells tomato sauce and ketchup in local and export markets, the latter which have stringent food safety and quality standards. Tomato transactions in Case 5 are highly uncertain due to susceptibility to physical, chemical and microbiological food safety hazards during production and handling. Another important issue increasing uncertainty in transactions relates to pesticide residue. Failure of growers to observe maximum residue limits (MRLs) can have deleterious consequences for the firm through export bans, product recalls and bad market reputation. The transaction cost implications of MRL standards include monitoring and measurement costs, as well as staff time where the agribusiness firm sends its own personnel to apply pesticides.

Due to high asset specificity and uncertainty, Cases 2 and 5 include provisions such as production budgets, delivery schedules, input control, supervision, written contracts, and detailed instructions. These hierarchy-like mechanisms enable agribusiness firms to exert control over farmers’ production decisions, thus safeguarding the investment into the asset and reducing behavioural uncertainty. In the two cases, agribusiness firms supply all inputs. Contracts are open-ended, or long-term with provisions for seasonal review. Long-term contracts allow firms to recoup the cost of specific assets over many growing seasons.

Case 6 is contrary to TCT predictions. The company opted for simple, informal contracts yet provided full input support to farmers. However, the company was not able to receive enough produce to satisfy the installed capacity due to pervasive side-marketing. Agribusiness managers noted that the situation did not maximise returns to the company, and they were in the process of reviewing the CFA. This supports Williamson’s (Citation1991) discriminating alignment hypothesisFootnote5 under which a mismatch between transaction characteristics and governance structure is predicted to lead to inefficiencies. Our finding raises the question: “What causes misalignment between transaction characteristics and governance structure in the first place?” The literature suggests two contradictory explanations. On one hand, an agribusiness firm may initially offer generous contract terms as it establishes itself and must attract farmers (Barrett et al. Citation2012). In such situations, the firm’s overriding objective is to attract farmers to participate in the CFA. Thus, contract design is rational and strategic. A contrary explanation is that the agribusiness firm’s contract design process may be unsystematic and based on trial and error (Bogetoft and Olesen Citation2002). Hence, the CFA may be established without a careful assessment of transaction characteristics. Our interviews with Case 6 management lend support to the rational design perspective. Management stated that misalignment was due to a strategic decision made by the firm to attract farmers to participate in the CFA. It was planned that efficient alignment between the CFA and transaction characteristics would be achieved gradually as bilateral dependence increased between the contracting parties.

Case 7 displays high asset specificity/low uncertainty. Specific assets include in-house brands and high temporal asset specificities associated with perishability of produce. As expected, the CFA uses group mechanisms to mitigate the hold-up problem posed by high asset specificity. The key issue for the agribusiness firm is to secure a steady flow of high-quality produce that maximises asset utilisation and brand reputation. A long-term written contract allows the firm to recoup the costs of its specialised investments.

Low asset specificity/ high uncertainty transactions characterise Cases 1 and 3. These firms are commodity traders. Asset specificity is low because they do not process wheat or have brands on the market. However, significant uncertainty is faced as wheat prices are determined on international markets. Consequently, the contracts specify import parity prices, which reduce moral hazard problemsFootnote6 by potentially benefitting both parties if price changes are favourable. Case 1 contract reduces side-selling through a “right of first refusal” clause that allows the producer to sell to other buyers if proof of a valid higher offer is provided.

Finally, as expected, transactions characterised by low asset specificity and low uncertainty (Cases 4 and 8) are coordinated by simple market-like contracts. In these two cases, farmers have long-term informal relationships with buyers. This suggests high levels of trust in these informal institutions, which may mean formal institutions are not required. Volumes and quality were considered important and yet the environment led to uncertainty of supply.

4.3 Research question 4: CFA typology based on correlates of contract provisions and transaction attributes

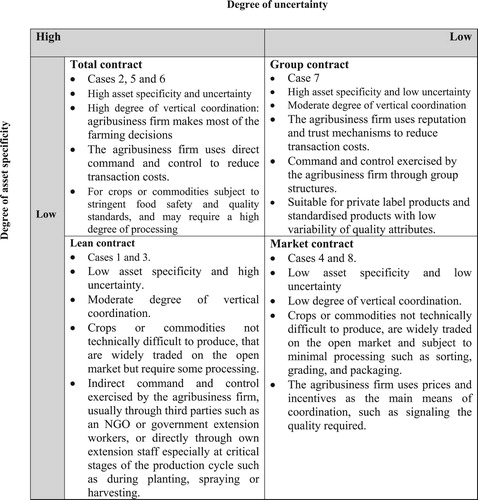

Based on the research results summarised in , observed CFAs can be categorised in the context of TCT. Following the conceptual framework, four uniquely different contract types can be distinguished, which we name total, group, lean and market contracts ().

Figure 4. Summary of contract types and characteristics. Source: Based on Williamson (Citation1985).

The four contract types are distinguished by different contract provisions and therefore, different degrees of vertical coordination in line with given transaction attributes. Instead of the Mighell and Jones (Citation1963) typology which “is of very little value for understanding the range of contemporary agricultural contracts” (Hueth et al. Citation2007, 1276), our classification is based on transaction characteristics (asset specificity and uncertainty) that are highly important and relevant in modern agrifood chains. Below, we describe the unique features of each CFA.

Total contract

Following Saussier (Citation2000), we define a total contract as one that “gives a more precise definition of the transaction and of the means to carry it out … a contract that specifies how to perform the transaction in every conceivable case” (192). Cases 2 and 5 are examples of total contracts.

A total contract is used for high asset specificity/high uncertainty transactions. It is a robust agreement that provides strict hierarchy-like control by the firm over the farmer’s production decisions, thus combines elements of resource-providing and production management contracts (Mighell and Jones Citation1963) and unified relational contract (Williamson Citation1979). It is suited for perishable products with variable quality such that the timing of growing, harvest, storage and transport are important. Thus, strict quality control and vertical coordination are required.

A written contract is used to provide the firm with better contract enforcement possibilities. The contract specifies the detailed roles, rights, and responsibilities of the parties. It also includes provisions on contract duration, technical assistance, procedures for supervision and monitoring, pricing formula, contract quota, quality testing procedures, penalties for noncompliance and dispute resolution mechanisms.

Under a total contract, the agribusiness firm provides all inputs and requires the farmers to follow a specific production method. The farmer may also be required to keep detailed records that are reviewed by the firm. For instance, Case 5 requires farmers to keep records on planting dates, the type and quantity of fertilisers applied and to provide pictures and samples of pests to the firm immediately in the event of crop infestation. Furthermore, the firm’s extension staff apply pesticides on the farmer’s crop to comply with MRL requirements in foreign markets. Thus, the farmer essentially participates in the CFA as a quasi-employee.

(b) Group contract

A group contract is used for high asset specificity/low uncertainty transactions. Instead of contracting individual farmers (and incurring high transaction costs), the firm signs a contract with a formal or informal producer organisation, an NGO or a group of farmers. A distinctive feature of a group contract is that it relies on shared norms and peer pressure to control hold-up. It builds on embedded social relationships, trust, reputation and identity to curb opportunistic behaviour and thus reduce transaction costs (Ouchi Citation1980).

The main concerns for the buying firm are to assure consistent supply, reduce the transaction and production costs, standardise product requirements and retain producers. As individual farmers often do not have the resources to make capital investments, a group of farmers may overcome this constraint by pooling resources (Gow and Swinnen Citation1998). By making reciprocal investments (such as warehouses, transportation), group mechanisms increase exit costs for farmers, thus ensuring assured supply for the firm’s specific assets.

Case 7 is an example of a group contract where the agribusiness firm organised farmers using pyramidal structures developed in consultation with traditional leaders. Self-selecting groups of up to 20 farmers elected a lead farmer for representation. Lead farmers combined to form a lead farmer committee that elected an executive chairman or area representative who dealt directly with the company agronomist. The firm also employed local extension agents. Contracts were signed with lead farmers. The lead farmer guaranteed input loan repayment and minimum quota deliveries by group members.

A group contract mitigates potential hold-up through a long-term contract which encourages the group to make reciprocal investments. A group bonus scheme based on volume, yield, and quality also provides incentives for farmers to supply enough quantity for the agribusiness firm’s processing capacity. For instance, Case 7 in our study pays a group bonus to lead farmers to incentivise them to recruit and retain competent farmers, achieve high yields, good product quality and repayment of loans. Temporal asset specificity is reduced through the provision of cold transport by the firm immediately after harvest.

(c) Lean contract

A lean contract is used for low asset specificity/high uncertainty transactions. The contract involves minimum input provision by the firm due to high uncertainty. High uncertainty can be due to pervasive side-marketing but may also emanate from other environmental factors such as high inflation, political instability, failing input markets, demand fluctuations, and price movements – which increase the potential for farmer opportunism (Gow and Swinnen Citation1998).

Cases 1 and 3 are examples of lean contracts. The agribusiness firms are commodity traders who contract with wheat farmers, consolidate purchases and sell to wheat processors with minimal processing. Thus, they have low asset specificity. However, they face high uncertainty in output markets as wheat prices are determined on international markets, the product is sold under forward contracts and has high quality variability. Due to this high uncertainty, the commodity traders provide a few critical inputs to farmers to guarantee themselves a minimum quantity of supply.

(d) Market contract

Our findings show that low asset specificity/low uncertainty transactions are associated with market contracts. As the potential for hold-up and opportunism is trivial and switching costs are low, it is expensive for the firm to craft, monitor and enforce complex contractual safeguards (Williamson Citation1979). Thus, the firm makes a simple promise to buy the product from farmers upon delivery.

Quality may not be a critical issue, or the product has common quality standards, and quality characteristics are observable. Sale and purchase conditions may be specified in a market contract, which may be written or oral. The agreement may also specify the location of sales and the quality of the product. A market contract differs from spot market transactions as, in the former, the buyer specifies certain conditions in advance and the identity of the producer is known.

In a market contract, the farmer maintains most of the decision rights over his farming activities and thus bears most of the risk of his production decisions. The contracts are often simple and seasonal. The contracting firm may not provide input credit or technical assistance at all. It is suitable for agricultural products requiring minimal processing.

5. Conclusions

This study sought to demonstrate that the use of transaction cost analysis can contribute to a better classification of contemporary CFAs. We argued that asset specificity and uncertainty are increasingly important determinants of governance structures in modern agri-food chains. For this purpose, the study took an agribusiness perspective and operationalised the insights of TCT in the study of tomato and wheat contracts in Zimbabwe. Specifically, we asked agribusiness managers their motivations for specific provisions in contracts and the level of the agribusiness firm’s transaction attributes. This way, we correlated contract provisions to transaction attributes and then developed a transaction cost-based CFA typology. Consequently, four unique CFA types are identified: total, lean, group, and market. The CFAs types are characterised by different combinations of asset specificity and uncertainty, and concomitantly, mechanisms for achieving coordination and control.

In summary, our results show that high asset specificity/ high uncertainty transactions are associated with detailed contracts and strict coordination which essentially “produce the effects of hierarchies” (Stinchcombe Citation1985, 165). We call this a total contract. Under a total contract, the agribusiness firm supplies and controls all the inputs on the farm and the farmer just provides land and labour.

High asset specificity/ low uncertainty transactions are governed by what we call group contracts. Group contracts are characterised by contracting by buyers to partner intermediaries (e.g., lead farmers, cooperatives and producer organisations) who manage out-growers and provide services. As such, there is limited direct agribusiness firm/farmer interaction. The group itself operates through trust, repeated transactions, and social control.

Low asset specificity/ high uncertainty transactions are governed by what we call lean contracts which provide minimal input. In a lean contract, the agribusiness firm only provides critical inputs to enable farmers to produce the contracted commodity. The agribusiness firm also can provide some level of production support to ensure contract compliance.

Low asset specificity/low uncertainty transactions are governed by simple selling and buying agreements, which we call market contracts. Here, the agribusiness firm simply guarantees a market but does not interfere in the production decisions of the farmer or supply inputs.

Our results also show that CFAs which are misaligned with underlying transaction attributes face problems of inefficiencies, side-marketing, and poor productivity. These findings lend support to the discriminating alignment hypothesis which attributes “excesses of waste, bureaucracy, slack” to alignment failures (Williamson Citation1991, 79). In our case study, misalignment reflected the company’s market entry strategy under which it offered generous contract provisions to attract growers to the CFA.

Our study makes three main contributions to the literature. First, the study connects transaction attributes to contract provisions to categorise contemporary agricultural contracts, thus going beyond the existing literature which merely describes the different forms of CFAs (e.g., Bellemare and Lim Citation2018).

Second, the study contributes the literature by proposing a theoretically-derived CFA typology that: (i) combines a production-management and resource-providing contract into “total contract”; (ii) identifies “group contract” as a specific type of contract; and (iii) splits the market specification contract in the classical typology into lean and market contract types. The typology proposed in this study can be used analytically and normatively to assist managers and farmers to select appropriate governance structures, given known transaction characteristics. Scholars and policymakers can also use the typology to compare and evaluate the performance of CFAs.

Third, the study extends Williamson’s (Citation1979) generic typology of contracts to contemporary CFAs. While Williamson’s typology related asset specificity to transaction frequency, this study related asset specificity to uncertainty, which are the most relevant attributes in contemporary agrifood chains (Ménard Citation2004; Weseen et al. Citation2014).

Our findings have managerial and policy implications. For managers, our transaction cost-based typology can help in the selection of a contract type that matches known transaction attributes. Arguably, such a typology is needed given the high failure rate of CF schemes which may, partly, result from misalignment between CFAs and transaction attributes.

From a policy perspective, our findings imply that policymakers can contribute to the modernisation of agriculture by accommodating the varieties of CFAs described in . For instance, because the value of transactions in lean and market CFAs tend to be low relative to the costs of legal recourse – in terms of time and money in the event of contract breach (Bellemare and Lim Citation2018) – matching dispute resolution mechanisms to contract types could yield efficiency gains by encouraging compliance.

Our findings suffer two limitations. First, because our CF typology is derived from a cross-sectional study of contract practices at a single point in time in Zimbabwe, it may be limited in its external validity. However, our use of a collective case study mitigates this limitation. Second, because our study is descriptive and does not establish causal relationships, its internal validity may be limited.

Future research could focus on incorporating trust and transaction frequency in the conceptual model, along the lines of Sartorius and Kirsten (Citation2007). Furthermore, further research in other commodities and institutional environments is needed to validate the typology in different contexts. Lastly, the literature shows that CFAs involving staples may face transaction risks such as the difficulty of contract enforcement, low perishability and high likelihood of contract breach (Maertens and Velde Citation2017). Hence, would be worthwhile to investigate if CFAs in staple crops can fit into the typology presented in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Throughout this paper, we use the term hierarchy-like to denote a hybrid structure with hierarchical attributes such as formal rules and plans, procedures and articulation of division of labour.

2 We use the terms “market-like” or ‘market contract’ to refer a hybrid structure with market attributes such as intensive use of incentives and prices as the main means of coordination (Ouchi Citation1980).

3 Lecturers at the University of Zimbabwe’s Department of Agricultural Economics.

4 Agribusiness managers typically comprised agronomy, procurement, and quality control managers in each company.

5 The discriminating alignment hypothesis predicts that managers who align governance structures with transaction attributes will achieve superior results.

6 According to Gow and Swinnen (Citation1998), moral hazard problems occur when one contracting party faces the risk that the other party will engage in activities that are undesirable from their perspective, such as shirking or debasing quality.

References

- Abebe, G.K., J. Bijman, R. Kemp, O. Omta, and A. Tsegaye. 2013. Contract farming configuration: Smallholders’ preferences for contract design attributes. Food Policy 40: 14–24.

- Ajwang, F. 2019. Relational contracts and smallholder farmers’ entry stay and exit in Kenyan fresh fruits and vegetables export value Chain. Journal of Development Studies 56, no. 4: 782–797.

- Barrett, C.B., M.E. Bachke, M.F. Bellemare, H.C. Michelson, S. Narayanan, and T.F. Walker. 2012. Smallholder participation in contract farming: Comparative evidence from five countries. World Development 40, no. 4: 715–30.

- Baumann, P. 2000. Equity and efficiency in contract farming schemes: The experience of agricultural tree crops. Vol. 111. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Bellemare, M.F., and S. Lim. 2018. In all shapes and colors: Varieties of contract farming. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 40, no. 3: 379–401.

- Bellemare, M.F., and L. Novak. 2017. Contract farming and food security. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 99, no. 2: 357–78.

- Bijman, J. 2008. Contract farming in developing countries. An overview of the literature. Working Paper, Wageningen University, Department of Business Administration.

- Bijman, J., R. Muradian and A. Cechin. 2011. Agricultural cooperatives and value chain coordination. In Value chains, social inclusion and economic development: Contrasting theories and realities, ed. A.H.J. (Bert) Helmsing, Sietze Vellema, 82-101. Routledge

- Bogetoft, P., and H.B. Olesen. 2002. Ten rules of thumb in contract design: Lessons from Danish agriculture. European Review of Agriculture Economics 29: 185–204.

- De Vita, G., A. Tekaya, and C.L. Wang. 2010. Asset specificity’s impact on outsourcing relationship performance: A disaggregated analysis by buyer–supplier asset specificity dimensions. Journal of Business Research 63, no. 7: 657–66.

- Drescher, K. 2000. Assessing aspects of agricultural contracts: An application to German agriculture. Agribusiness 16, no. 4: 385–98.

- Eaton, C., and A. Shepherd. 2001. Contract farming: Partnerships for growth ( No. 145). Rome: FAO.

- Fafchamps, M., and B. Minten. 2001. Property rights in a flea market economy. Economic Development and Cultural Change 49, no. 2: 229–67.

- Fulponi, L. 2006. Private voluntary standards in the food system: The perspective of major food retailers in OECD countries. Food Policy 31, no. 1: 1–13.

- Gow, H.R., and J.F.M. Swinnen. 1998. The impact of FDI on CEEC agricultural growth: Case studies. Policy Research Group Working Paper, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

- Harou, A., and T. Walker. 2010. The pineapple market and the role of cooperatives. Working Paper, Cornell University.

- Henson, S., O. Masakure, and J. Cranfield. 2011. Do fresh produce exporters in Sub-Saharan Africa benefit from GlobalGAP certification? World Development 39, no. 3: 375–86.

- Hobbs, J.E., and L.M. Young. 1999. Increasing vertical linkages in agrifood supply chains: A conceptual model and some preliminary evidence. Trade Research Center, Montana State University.

- Hueth, B., E. Ligon, and C. Dimitri. 2007. Agricultural contracts: Data and research needs. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 89, no. 5: 1276–81.

- Jaffee, S. 1995. Transaction costs, risk and the organization of private sector food commodity systems. In Marketing Africa’s high value foods: Comparative experiences of an emergent private sector, ed. S. Jaffee and J. Morton. Dubuque (USA), Kendall Hunt Publishing.

- Jaffee, S., S. Henson, and L. Diaz Rios. 2011. Making the grade: Smallholder farmers, emerging standards, and development assistance programs in Africa - A research program synthesis. World Bank.

- Key, N., and D. Runsten. 1999. Contract farming, smallholders, and rural development in Latin America: The organization of agroprocessing firms and the scale of outgrower production. World Development 27, no. 2: 381–401.

- Kirsten, J., and K. Sartorius. 2002. Linking agribusiness and small-scale farmers in developing countries: Is there a new role for contract farming? Development Southern Africa 19, no. 4: 503–529.

- Li, L., H. Guo, J. Bijman, and N. Heerink. 2018. The influence of uncertainty on the choice of business relationships: The case of vegetable farmers in China. Agribusiness 34, no. 3: 597–615.

- Maertens, M., and K.V. Velde. 2017. Contract-farming in staple food chains: The case of rice in Benin. World Development 95: 73–87.

- Martino, G., and A. Frascarelli. 2013. Adaptation in food networks: Theoretical framework and empirical evidences. International Journal on Food System Dynamics 4, no. 1: 1–14.

- Martino, G., and C. Perugini. 2006. Food safety and governance choices. Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali 3, no. 9: 433–58.

- Masten, S.E. 2000. Transaction-cost economics and the organization of agricultural transactions. In Industrial organization advances in applied microeconomics, ed. Michael Baye and John Maxwell, 173–95. Bingley. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Ménard, C. 2004. The economics of hybrid organizations. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 160, no. 3: 345–76.

- Mighell, R.L., and L.A. Jones. 1963. Vertical coordination in agriculture. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Agricultural Economics Report No. 19. Washington, DC, February.

- Ouchi, W.G. 1980. Markets, bureaucracies and clans. Administrative Science Quarterly 25: 129–41.

- Raynaud, E., L. Sauvée, and E. Valceschini. 2009. Aligning branding strategies and governance of vertical transactions in agri-food chains. Industrial and Corporate Change 18, no. 5: 835–68.

- Reardon, T., T. Awokuse, S. Haggblade, T. Kapuya, S. Liverpool-Tasie, F. Meyer, B. Minten, et al. 2019. The quiet revolution and emerging modern revolution in agri-food processing in Sub-Saharan Africa. Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Reardon, T., and D. Zilberman. 2018. Climate smart food supply chains in developing countries in an era of rapid dual change in agrifood systems and the climate. In Climate smart agriculture, 335–51. eds. David Zilberman, Renan Goetz and Alberto Garrido Cham: Springer.

- Repar, L.A., S. Onakuse, J. Bogue, and A. Afonso. 2018. Is it all about the money? Extent, reasons and triggers for side-selling in Malawi’s paprika supply chain. International Journal on Food System Dynamics 9, no. 1: 38–53.

- Sartorius, K., and J.F. Kirsten. 2005. The boundaries of the firm: Why do sugar producers outsource sugarcane production? Management Accounting Research 16, no. 1: 81–99.

- Sartorius, K., and J. Kirsten. 2007. A framework to facilitate institutional arrangements for smallholder supply in developing countries: An agribusiness perspective. Food Policy 32, no. 5–6: 640–55.

- Saussier, S. 2000. Transaction costs and contractual incompleteness: The case of Électricité de France. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 42: 189–206.

- Stake, R. 1995. The art of case study research: Perspective in practice. London: Sage.

- Stinchcombe, A.L. 1985. Contracts as hierarchical documents. In Organizational theory and project management, ed. A.L. Stinchcombe and C. Heimer, 121–71. Oslo: Norwegian University Press.

- Stump, R., and J. Heide. 1996. Controlling supplier opportunism in industrial relationships. Journal of Marketing Research 33, no. 4: 431–41.

- Swinnen, J.F.M., and M. Maertens. 2007. Globalization, privatization, and vertical coordination in food value chains in developing and transition countries. Agricultural Economics 37, no. 1: 89–102.

- Tadesse, W., Z. Bishaw, and S. Assefa. 2018. Wheat production and breeding in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 11, no. 5: 696–715.

- Tschirley, D., T. Reardon, M. Dolislager, and J. Snyder. 2015. The rise of a middle class in urban and rural east and Southern Africa: Implications for food system transformation. Journal of International Development 27, no. 5: 628–46.

- Vermeulen, H., J. Kirsten, and K. Sartorius. 2008. Contracting arrangements in agribusiness procurement practices in South Africa. Agrekon 47, no. 2: 198–221.

- Weseen, S., J.E. Hobbs, and W.A. Kerr. 2014. Reducing hold-up risks in ethanol supply chains: A transaction cost perspective. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 17, no. 2: 83–106.

- Williamson, O.E. 1975. Markets and hierarchies. Free Press. New York, 26–30.

- Williamson, O.E. 1976. The economics of internal organization: exit and voice in relation to markets and hierarchies. The American Economic Review 66, no. 2: 369-377.

- Williamson, O.E. 1979. Transaction cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. The Journal of Law and Economics 22: 233–61.

- Williamson, O.E. 1985. The economic institutions of capitalism. New York: The Free Press.

- Williamson, O.E. 1988. The logic of economic organization. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 4: 65–93.

- Williamson, O.E. 1991. Strategizing, economizing, and economic organization. Strategic Management Journal 12: 75–94.

- Williamson, O.E. 2000. The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature 38, no. 9: 595–613.

- Yin, R.K. 2003. Case study research: Design and methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.