Abstract

We investigated the framing of climate change science in New Zealand newspapers using quantitative content analysis of articles published in The New Zealand Herald, The Press and The Dominion Post between June 2009 and June 2010. The study sample of 540 articles was collected through the electronic news database Factiva, using the search terms ‘climate change’ or ‘global warming’. Frames were analysed deductively according to an experimental frame typology. Sources were also coded and basic descriptive data recorded. Content analysis showed the Politics (26%), Social Progress (21%) and Economic Competitiveness (16%) frames were the most prominent in coverage. Political actors (33%) and Academics (20%) appeared most commonly as sources, while Sceptics represented just 3% of total sources identified. The results suggest that New Zealand newspapers have presented climate change in accordance with the scientific consensus position since 2009, focusing on discussion of political, social and economic responses and challenges.

Introduction

Anthropogenic climate change is a major environmental issue of our time. Successive reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have established the warming of the atmosphere and ocean system as ‘unequivocal’ and revealed increasing levels of confidence that human influence has been the dominant cause of warming observed since 1950. The IPCC suggests the warming effects of climate change are likely to have significant impacts on physical and biological systems during the 21st century and beyond (McCright & Dunlap Citation2000; IPCC Citation2007a, Citationb). In New Zealand, the general impacts of climate change over the next 30 to 40 years are likely to include rising sea levels, higher temperatures, more extreme weather events such as droughts and floods, and changes in rainfall patterns (Ministry for the Environment Citation2009a).

Despite trading on a ‘clean and green’ image, New Zealand's output of greenhouse gases (GHGs) ranks as the 11th highest per capita in the world, owing significantly to emissions produced by its strong agricultural industry (Dew Citation1999; Coyle & Fairweather Citation2005; Ministry for the Environment Citation2009b). The economic reliance on agriculture, combined with the country's comparatively low reliance on fossil fuels in energy generation, means that New Zealand faces some unique challenges in seeking to reduce its emissions output and this is reflected in the country's cautious approach on climate change policy domestically and internationally. New Zealand's original legislation in response to climate change was established in 2002 and the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) was established in 2008 to put a price on carbon emissions (Ministry for the Environment Citation2014). Amendments to this legislation were made in 2009, 2012 and 2014, largely to reduce the impact of its costs on the economy (Ministry for the Environment Citation2014). Since 2010, the New Zealand Government made it clear that it intended to be a ‘fast follower’ rather than a leader on climate change policy, and sought to achieve a balance between ‘the environmental risks of climate change [and] the economic impacts on New Zealand of reducing emissions’ (Ministry for the Environment Citation2009b).

According to polls, New Zealanders are somewhat ambivalent in their attitudes and beliefs around climate change. While many think it is a serious issue, it ranks relatively low overall, in terms of concern and priority, in comparison with issues such as education, health, cost of living and domestic environmental issues (TNS Conversa Citation2008; ShapeNZ Citation2009; Stuart Citation2009). Despite the broad scientific consensus, recent studies also reflect mixed findings among the public regarding the certainty and causes of climate change. One national survey in 2009, for example, found that 41% of respondents believed humans had a very direct impact on climate (Stuart Citation2009). A 2010 UMR Research report for the Greenhouse Policy Coalition, in contrast, indicated a growing perception among the New Zealand public that climate change was caused by natural rather than anthropogenic causes and found that more than two-thirds of respondents believed that the evidence for climate change was a matter of significant disagreement among scientists (UMR Research Citation2010).

As a primary source of public information on science and technology, the news media are understood to play an important role in shaping public understanding of and attitudes towards complex and/or abstract scientific issues (Bell Citation1994; Nelkin Citation1995; Wilson Citation1995). Science is reconstructed in the media according to a complex interaction of choices, norms and pressures that determine if an issue features and is supported in the news (Carvalho Citation2007, p. 223). The particular filter or frame through which audiences come to perceive issues is the outcome of a process of selection, emphasis and presentation in the construction of news texts, by which certain perspectives on a given issue are chosen over others (Entman Citation1993). Given that most people are unlikely to have relevant first-hand experience of scientific issues such as climate change, their framing in the media can play a significant role in shaping public understanding and attitudes towards them (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur Citation1976; Corbett Citation2005; Dirikx & Gelders Citation2009).

In terms of media attention to climate change, 2009 represented a historical high-water mark: the apex of a rapid increase in media coverage observed in the latter part of the 2000s, which had seen the issue thrust firmly into mainstream public consciousness. Researchers tracking climate change coverage in 50 influential newspapers around the world (including New Zealand), observed a five-fold increase in the volume of coverage between 2000 and the end of 2009 (Boehnert et al. Citation2014; Boykoff Citation2014). This particular peak in coverage can be associated with two discursive moments in the recent development of climate change as an issue: the ‘Climategate’ saga and the Copenhagen Summit in December that year (Boykoff Citation2010; Anderson Citation2011).

Climategate

In late November 2009, extracts of emails hacked from the accounts of researchers at the University of East Anglia's Climatic Research Unit in the UK were leaked online, appearing to show that some of the world's foremost climate scientists had conspired to exaggerate warming trends, suppress the publication of conflicting research and to delete evidence systematically that conflicted with established models (Hasselmann Citation2010; Anderson Citation2011; Greenberg et al. Citation2011). Although the scientists were eventually cleared of misconduct, some of the exchanges revealed unprofessional and antagonistic behaviour, which plainly cast some in an unflattering light (Adam Citation2010; Hasselmann Citation2010). Scholars have suggested that the Climategate saga, as it was dubbed, dealt a significant blow to ‘the credibility of the climate science establishment’ (Greenberg et al. Citation2011, p. 66).

Copenhagen

The United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark (the Copenhagen Summit), held from 7–18 December 2009, presented a potential step towards international policy measures on emissions reductions and was proposed to produce a framework for a successor to the Kyoto Protocol. One of the key objectives of the conference was to negotiate a legally binding agreement among the 192 signatory nations that would commit them to ambitious emissions reductions post-2012 (Bodansky Citation2010; Falkner et al. Citation2010). Such an agreement proved to be elusive. Negotiations broke down following disagreements over differences in the level of commitment expected of certain developed and emerging economies, and as a result, the conference was unsuccessful in producing a binding agreement. In its stead, the Copenhagen Accord, a document drafted by the USA and other major emitters, was ‘taken note of’ by delegates at the summit (see Bodansky Citation2010 for a review of the Copenhagen Summit). The highly conditional emissions reductions target of 10%–20% below 1990 levels taken to negotiations by the 2010 National New Zealand Government at the Copenhagen Summit was met with strong criticism both domestically and internationally. In late 2009 there was also significant political dialogue around the 2010 National Government's Emissions Trading scheme, which was eventually criticised on grounds of being unambitious and ‘watered down’ to the point that it offered only ‘weak incentives for subsidised industries to change … while generating few environmental gains’ (Hood Citation2010; Williams Citation2010).

Previous research has looked extensively at how climate change has been framed in the broadsheet newspapers of a wide range of countries (e.g. Boykoff & Boykoff Citation2004; Brossard et al. Citation2004; Boykoff Citation2007; Carvalho Citation2007; Grundmann Citation2007; Boykoff Citation2008; Carvalho & Pereira Citation2009; Dirikx & Gelders Citation2009; Olausson Citation2009; Billett Citation2010; Gordon et al. Citation2010; Takahashi Citation2011), including New Zealand (Kenix Citation2008).

These studies have highlighted some differences in the emphasis of newspaper coverage between countries. Analyses of the US press have revealed a tendency to frame climate change in terms emphasising scientific controversy and disagreement, whereas newspapers in the UK, Germany and Sweden have framed the issue in terms emphasising potentially catastrophic consequences (Weingart et al. Citation2000; Zehr Citation2000; Boykoff & Boykoff Citation2004; Antilla Citation2005; Ereaut & Segnit Citation2006; Hulme Citation2007; Olausson Citation2009; Nerlich et al. Citation2010). While climate ‘sceptics’ and sceptical organisations have featured fairly prominently as sources in US climate change coverage, they have been largely absent in the German press (Grundmann Citation2007). These differences reflect the varying political, economic and cultural contexts of news in these countries, as well as variations in journalistic norms around ‘objectivity’ and the construction of ‘exciting’ stories.

Previous analyses of coverage in New Zealand newspapers suggest that climate change has been framed in terms largely consistent with the ‘scientific consensus’ position affirmed by the IPCC and other scholarly bodies, and that the sceptical or ‘denialist’ voice has had little space in news discourse (Dispensa & Brulle Citation2003; Kenix Citation2008; Howard-Williams Citation2009).

There are some limitations to these previous New Zealand studies. Howard-Williams' study (Howard-Williams Citation2009), for example, was based on a sample drawn from a single month of coverage in 2007, and was skewed towards Australian coverage, in that just 40 of the 135 articles analysed were drawn from The New Zealand Herald and The Press. Although certainly more robust, and drawing also from The New Zealand Herald, Kenix's findings (Kenix Citation2008) are potentially limited by the fact that, in its function as an aggregator of press releases, the content of Scoop.co.nz is not wholly comparable to news stories produced by journalists and editors in broadsheet newspapers. Furthermore, Williams' study (Williams Citation2010) of front-page articles in The Press was an analysis of story topics driving reporting, and not an analysis of framing per se.

Current understanding on the framing of climate change in New Zealand newspapers is therefore limited by a dearth of relevant and comparable data. Moreover, the current body of work is based almost entirely on coverage in The New Zealand Herald and The Press published prior to 2008 (Dispensa & Brulle Citation2003; Kenix Citation2008; Howard-Williams Citation2009; Williams Citation2010).

There has yet to be an analysis of coverage in the country's second most widely read newspaper The Dominion Post, which is published in Wellington, New Zealand's capital city and political centre. Furthermore, little research has been carried out on coverage that has been published since the beginning of 2009—a significant time in the recent development of climate change as an issue in the media.

Methods

Selection of frames

This study used an experimental typology (see ) based on the findings of previous framing studies on climate change and structured through the use of a more generalisable typology designed by Nisbet (Nisbet & Scheufele Citation2009; Nisbet Citation2010). As Nisbet's typology was itself designed from previous studies on science issues, including climate change, it provided a useful scaffold for organising the heterogeneous collection of frames defined in the literature from which this study draws. Although a certain degree of sensitivity was ostensibly lost as a result of a decision to homogenise and consolidate certain frames sharing similar attributes (e.g. international politics, domestic politics and public accountability were combined), this typology is representative of the frames most commonly identified across the literature to date, and particularly so with previous studies of New Zealand newspapers.

Table 1 Frame typology.

Research questions

This study aimed to analyse how climate change has been framed in recent coverage across New Zealand's major newspapers. The following research questions were posed:

What frames were most/least prominent in coverage of climate change across The Dominion Post, The New Zealand Herald and The Press over the period between June 2009 and June 2010?

Were there any differences in the prominence of frames between The Press, The New Zealand Herald and The Dominion Post over the study period?

What sources were most prominent in coverage over this period?

How did attention to climate change vary over the study period?

The sample

Articles on climate change published in The New Zealand Herald, The Dominion Post and The Press over a 12-month period between 1 June 2009 and 31 May 2010 were analysed. This time frame was chosen because climate change was high on public and political agendas over this period, both in New Zealand and internationally. This period included intense debate over the merits and costs of the revised Emissions Trading Scheme, the breaking of the Climategate email hacking incident, and the international climate policy summit in Copenhagen, Denmark.

The New Zealand Herald, The Dominion Post and The Press were chosen for analysis as they represent New Zealand's three largest daily broadsheet newspapers in terms of readership. With circulations covering the upper North Island, the lower North Island, and much of the South Island, respectively, The New Zealand Herald, The Dominion Post and The Press together offer a representative cross-section of mainstream broadsheet newspaper coverage of climate change in New Zealand (APN.com.au/; http://www.fairfaxmedia.co.nz). As of 2011, the APN News & Media-owned New Zealand Herald had the highest readership of 17.6%; this was followed by The Dominion Post (6.8%) and The Press (6.5%), which, while retaining editorial independence, share ownership as well as a copy-sharing agreement under Fairfax Media Limited (Williams Citation2010; Nielsen & Kjaergaard Citation2011). It is worth noting that New Zealand newspapers generally have no overt political alignments, with their editorial foci and readerships largely defined by their geographical distribution in the country (Campbell & Cleveland Citation1973).

The sample was collected by running a search through the electronic news database Factiva for articles containing either the term ‘climate change’ or ‘global warming’ in the headline or first paragraph.Footnote1 Limiting the search to these sections aided in reducing the number of articles returned, in which climate change was peripheral (Pan & Kosicki Citation1993; Trumbo Citation1996; D'Angelo Citation2002; Antilla Citation2005; Gordon et al. Citation2010). The search parameters excluded letters to the editor, limiting the sample to hard news, features, comment and editorials. A total of 1104 articles published over the study period were collected. These were manually refined to remove duplicates, letters, news briefs and peripheral stories. The final sample of 540 articles included 243 from The New Zealand Herald, 153 from The Dominion Post and 144 from The Press. Before the onset of data collection, a pilot study of 50 random articles was conducted in order to further refine the frame typology and ensure consistency in the coding process.

Content analysis of frames

During the examination of each article, the newspaper of publication was recorded (H = The New Zealand Herald, P = The Press, D = The Dominion Post), with the date of publication, the name of the reporter, and a short summary of the key points/issues. In the second reading, frames were identified according to criteria established in the frame typology (). This was facilitated by the systematic application of basic analytical tools adapted from Olausson (Olausson Citation2009), designed to help deconstruct and highlight elements of meaning, implicit in the text. Using an instrument designed originally by McComas & Shanahan (Citation1999), and employed in similar studies by Brossard et al. (Citation2004) and Kenix (Citation2008), frames were coded as either absent (0), present (1) or dominant (2), if they were prominent in the headline and leading sentences, or represented the central organising idea for the article as a whole. Although multiple frames could be coded as present in the text, only one could be coded as dominant. Sources, defined as actors quoted or paraphrased in articles, were similarly coded as either absent (0) or present (1) according to categories outlined in .

Table 2 Source categories.

Statistical analysis

Basic descriptive statistics were employed to measure and compare the frequency or prominence of frames and sources. The overall prominence of each frame was measured as the percentage of articles out of the total (n = 540), in which a given frame was coded as either present (1) or dominant (2). The prominence of sources appearing in coverage was measured as a percentage of the total number coded as present. Publication frequency or coverage was calculated as the total number of articles published per month.

Differences in the prominence of frames between newspapers were measured slightly differently. The mean prominence of each frame was calculated by finding the average of the total scores coded (from the range of 0, 1 or 2) for each newspaper subsample (Brossard et al. Citation2004; Kenix Citation2008). For example, if the Morality frame was coded as 0, 0, 0, 2, 1 across five articles, the mean prominence (m) would be calculated as 0.6. These were calculated for each frame, across the three newspapers. A one-way ANOVA was used to detect any significant differences in the prominence of frames between each newspaper. As the data met the condition of homoscedasticity, post-hoc comparisons were carried out for significant findings using the Tukey HSD test.

Results

Newspaper attention over the study period

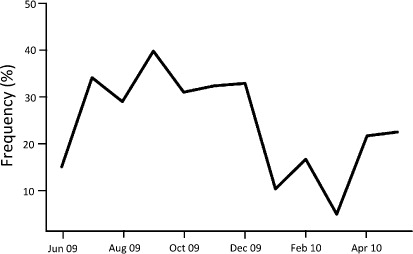

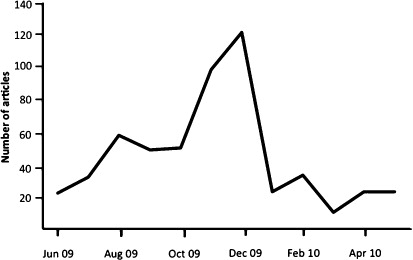

Coverage showed a trend of growth over the first half of the study period, reaching a peak during November (99 articles) and December 2009 (122 articles), coinciding with the breaking of the Climategate email hacking and the highly anticipated Copenhagen Summit (). The peak in coverage occurred within the same time frame as the leak of the Climategate emails in late November, and the holding of the Copenhagen Summit in December 2009.

Frame prominence

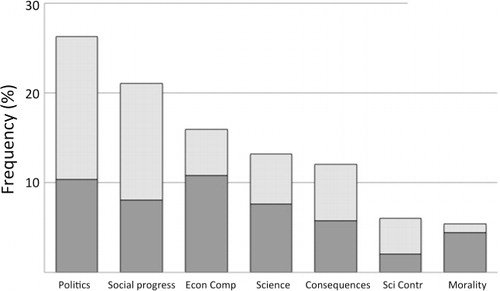

Prominence of each frame is shown in . The Politics frame was the most prominent across coverage, making up 26% of the total frames identified. The Social Progress frame was the second most prominent, with 21% of the total frames. Both of these frames were more likely to be Dominant than Present in the articles in which they appeared. The Economic Competitiveness frame was the third most prominent frame making up just less than 16% of the total, and was much less likely to be Dominant in articles in which it appeared. The Science and Consequences frames made up 13% and 12% of frames coded, respectively. The Scientific Controversy and Morality frames were the least prominent in the study sample, making up 6% and 5% of the total frames coded, respectively ().

Differences in the prominence of frames between newspapers

The overall prominence of frames between newspapers was similar (). One-way ANOVA showed that the Consequences frame was significantly more prominent in both The Dominion Post (m = 0.405, n = 144) and The New Zealand Herald (m = 0.424, n = 243), than it was in The Press (m = 0.208, SD = 0.514) (F [2,537] = 4.880, P < 0.005). The Science frame was found to be significantly more prominent in The New Zealand Herald (m = 0.461, SD = 0.717) than in The Press (m = 0.28, SD = 0.62) (F [2,537] = 4.633, P < 0.05) and the Economic Competitiveness frame was found be significantly more prominent in The Dominion Post (m = 0.575, SD = 0.758) than it was in The New Zealand Herald (m = 0.29630, SD = 0.577) (F [2,537] = 8.606, P < 0.05).

![Figure 3 Mean frame score (0–2) of each frame, comparing The New Zealand Herald (n = 243, pale grey), The Dominion Post (n = 153, dark grey) and The Press (n = 144, white). Significant differences were detected in the mean scores of the Economic Competitiveness (Economic Comp.) (F [2,537] = 8.606, P < 0.05), Science (F [2,537] = 4.633, P < 0.05) and Consequences (F [2, 537] = 4.880, P < 0.05) frames.](/cms/asset/bb2f848c-2328-479d-b21c-35624edfbb5d/tnzr_a_996234_f0003_b.jpg)

Frame content analysis

Politics frame

Articles employing the Politics frame generally emphasised policy-based solutions for the problems of climate change, and politicians, world leaders and nation states as the primary actors accountable for the issue and ultimately possessing the ability to solve the problem. The Politics frame was perhaps best characterised by an emphasis on political actors as ‘responsible for and/or capable of alleviating climate change problems’ (Dirikx & Gelders Citation2010, p. 732). An emphasis on the Politics frame was more commonly manifested in coverage of the actions and comments of world leaders in relation to talks and negotiations at various international policy events (see Appendix 1 for quotes from each frame).

The Politics frame was also characterised by an emphasis on climate policy as a point of significant conflict between political actors, on a scale from regions divided along developmental lines to individual nation states. The frame was also evident in an emphasis on negotiations and propositions around climate policy as a matter of strategy between political actors. This was evident at the level of national policy and political parties, particularly in ongoing speculation over the New Zealand Government's attempt to win support for its' amended Emissions Trading Scheme (Appendix 1, Frame 1b).

The employment of the Politics frame appeared to be related to key policy disputes and events that occurred over the study period. A steep drop in frame frequency occurred in January 2010 following the failure of the Copenhagen Summit, before it began to rise again in May, from renewed debate around the Emissions Trading Scheme ().

Social Progress frame

The Social Progress frame was characterised by an emphasis on the accountability and efficacy of individual citizens, local communities and business and industry in efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change, either directly, or indirectly through sociopolitical action and raising awareness.

Alongside coverage of the celebrity-endorsed Greenpeace ‘Sign-on’ campaign, notable emphasis was accorded to human interest-style reporting on the grassroots efforts of citizens and communities to raise awareness for reduction in emissions as part of the 350.org movement (Appendix 1, Frame 2a).

At a broader societal level, efforts to reduce emissions were similarly framed not only in terms of avoiding negative outcomes, but also in terms of producing positive outcomes, of improvement through ‘gain framing’ (Spence & Pidgeon Citation2010). An article by Malcolm Rands in The New Zealand Herald, for example, suggested ‘What's good for the climate is also good for our health’, linking emissions reductions to a reduction in asthma-related illness and deaths through an improvement in air quality (Rands Citation2009). Similarly, a story entitled ‘Doctors attack climate change stance’, stated ‘… mitigating climate change also presents “unrivalled opportunities” to improve public health. Policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions could also bring about substantial reductions in heart disease, cancer, obesity, diabetes, road deaths and injuries, and air pollution’ (Johnston Citation2009).

The Social Progress frame also provided an emphasis on technological solutions and innovation to reduce emissions and tackle climate change, often with a focus on advances in energy generation. An article headlined ‘Absorbing ideas to combat warming’ outlined potential solutions developed by British engineers, including ‘artificial’ trees that could be ‘several thousand times more effective at removing carbon dioxide than any natural tree’ and the incorporation of ‘photobioreactors’ into building structures, to absorb carbon dioxide while producing energy for light and heat generation (Doesburg Citation2009).

This was also evident in coverage of innovation towards greater sustainability and efficiency in industry, and was often paired with an economic competiveness frame. Innovation in renewable energy generation and shifts away from fossil fuels were often linked to wider benefits to security and economic growth (Appendix 1, Frame 2b).

Economic Competitiveness frame

The Economic Competitiveness frame was overall the third most frequently identified in the study sample; however, it was twice as likely to be Present than it was to be the Dominant frame in the articles in which it appeared (). This reflected the finding that while considerations of economic impacts and costs were common in coverage, they were for the most part ancillary to the main topics of news stories.

In general, the Economic Competitiveness frame was evoked through an emphasis on the potential opportunities and/or costs to economies presented by policy measures to mitigate GHG emissions, and the wider challenge of climate change. At the most basic level, this was evident in a focus on financial costs to taxpayers of the New Zealand Government's Emissions Trading Scheme, and of meeting its 2020 emissions reduction targets (Appendix 1, Frame 3a).

Considerations of cost vs benefit were particularly evident in deliberation over the level of ambition New Zealand should adopt in its approach to domestic emissions policy measures. Overall, it was broadly consistent with the National Government's stated approach of seeking to balance ‘New Zealand's economic opportunities with its environmental responsibilities’ in its approach to climate change (Ministry for the Environment Citation2009a). Indeed, Williams found that coverage of climate change in The Press tended to focus strongly on ‘economic elements of proposals such as the boost to the region in terms of gross domestic product or jobs’ (Williams Citation2010, p. 37).

A tension between the potential economic implications of being ‘too ambitious’ and of not being seen to be ambitious enough was frequently constructed in coverage around domestic emissions policy (Appendix 1, Frame 3b). Criticising the government's eventual policy response as ‘overly cautious’ and ‘timid’, a number of articles emphasised the potential costs to the New Zealand economy of not living up to the country's ‘clean green’ brand. This framing was often employed by spokespeople of environmental groups and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), for example by the executive director of Oxfam New Zealand and by Gary Taylor, executive director of the New Zealand Environmental Defence Society (Appendix 1, Frame 3c). This was taken a step further in a small number of articles highlighting the potential opportunities for economies, presented by the wider challenge of climate change (Appendix 1, Frame 3d).

Science frame

In the Science frame, climate change was largely presented as a scientific issue in which the expert authority of scientists and academics was emphasised. The Science frame was commonly found in articles presenting new research and findings and was often characterised by use of technical details and terminology, emphasising the expert nature of the subject (Appendix 1, Frame 4). The Science frame was also evident in articles presenting the scientific background of climate change and recapitulating what is ‘known vs unknown’. The fact that articles discussing this kind of information often did so with regard to claims regarding controversy and ongoing debate might explain why the Science frame was more likely to be Present rather than the Dominant focus of the articles in which it appeared. Following the leak of the Climategate emails and revelations of mistakes in the 2007 IPCC report, for example, Peter Hardstaff (Citation2010) attempted to ‘take a step back from the hype and put things in perspective’ by reiterating the consensus position on climate change, while acknowledging where uncertainties still remained (Appendix 1, Frame 4).

Consequences frame

The Consequences frame generally featured an emphasis on the potential effects of climate change on people and the environment as central to considerations of the problem, and the need to act to mitigate it. The frame was characterised through the use of dramatic language and the outlining of potential, often disastrous, future impact scenarios (Appendix 1, Frame 5).

Impacts on human health were also a significant focus of the Consequences frame, their severity linked to the extent of action taken to stem GHG emissions (Appendix 1, Frame 5).

Scientific Controversy frame

The perception of an ongoing scientific debate over the reality and causes of climate change was evoked through an emphasis on disputes and the construction of two irreconcilable, although ostensibly equally legitimate, sides on which experts and laypeople are divided. This was evident, for example, in coverage of disagreement over the significance of a paper, claiming that temperature rises were related to el Niño/la Niña weather patterns (natural causes), rather than to GHG emissions (anthropogenic causes) (McLean et al. Citation2009). The Scientific Controversy frame was evident in a series of articles (e.g. Coates Citation2009a), discussing a dispute between the New Zealand authors of a scientific paper on the effects of the Southern Oscillation on global temperatures (McLean et al. Citation2009) and New Zealand climate scientists from the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), Jim Salinger and James Renwick. These articles employed a ‘duelling experts’ scenario to depict controversy and lack of certainty (Corbett & Durfee Citation2004; Anderson Citation2009; Coates Citation2009a,Citationb; Russill & Nyssa Citation2009). In this scenario, drama was elicited through the interpolation of comments and criticisms from Salinger and Renwick, with claims made by the authors McLean, de Freitas and Carter, as ‘experts’ engaged in dispute over the research (Appendix 1, Frame 6). The dispute was also positioned within the context of a broader, ongoing, back-and-forth debate between sceptics and climate scientists, emphasising the perception of a continuing scientific controversy and conflict over the true causes of climate change (Appendix 1, Frame 6).

The perception of climate change as a scientific controversy was also evoked through the establishment of causal links between otherwise disparate events that occurred over the study period. This was evident for example in the linking of allegations of data manipulation arising from the Climategate emails in November 2009, and the finding of mistakes in the 2007 IPCC report in early 2010 (Appendix 1, Frame 6). Uncertainty and controversy were also played down, through the dismissal of climate sceptics as doubters or deniers.

Morality frame

The Morality frame was the least prominent in the sample, consisting of just 5% of the total frames coded, and Dominant in less than a fifth of those. Where the frame was identified, there was often an emphasis on the charge to act on climate change for the sake of future generations and the environment, establishing both individuals and humanity as a whole as accountable for the problem (Appendix 1, Frame 7). Moral and ethical considerations of fairness were emphasised as the justification for why rich countries in the developed world should shoulder a greater share of the burden in efforts to mitigate emissions. Articles also underscored the disparity between the relatively low contribution of people in developing and poor countries to the climate change problem, and the high level of risk they faced from it. New Zealand was implicated in this divide as one of the rich countries that have created the problem. The moral responsibility of New Zealand to be bold in its efforts to mitigate emissions was emphasised through a focus on the plight of island nations in the Pacific as ‘our neighbours’ (Appendix 1, Frame 7).

Analysis of sources

Political sources featured most commonly in coverage, representing 33% of all sources identified, followed by scientists/academics (20%) and NGOs (13%). Sceptics made up just 3% of sources, ahead of economists (2%) and unnamed experts (<1%). Articles in which no source was present, or an unnamed expert was referred to, together made up 2% of the total.

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of the current study was to investigate how climate change had been framed in coverage in New Zealand's major daily newspapers The New Zealand Herald, The Press and The Dominion Post during a critical time in the recent development of climate change as an issue in the media. By using a quantitative content analysis of coverage between June 2009 and June 2010, this study found that climate change was framed in a manner that reflected a strong alignment with the scientific consensus position: that it is real and very likely to be anthropogenic in cause. Climate change was positioned as an issue that could be addressed if necessary steps were taken by policymakers and political leaders, as well as by individuals and through technological innovation to mitigate GHG emissions. What is more, such steps were regularly framed in terms of the potential additional benefits they could offer to the economy, to individuals and to the ‘progress’ of society more generally.

Sceptics or deniers were given little voice, and on the relatively rare occasion that controversy or disagreement over the scientific evidence for climate change was emphasised in coverage, it was often attenuated through a recapitulation of a broad scientific consensus saying otherwise. Moreover, as evidenced in the dominance of Politics, Social Progress and Economic Competitiveness frames, coverage over the study period was focused strongly on ways of responding to climate change, rather than on the potential consequences, moral implications or indeed the ‘certainty’ of the problem itself.

The prominence of these frames appears to be linked to a focus on climate policy in the lead up to the Copenhagen Summit, which included discussion around the 2010 National Government's proposed Emissions Trading Scheme. The findings are nonetheless broadly consistent with previous research over the past decade in The New Zealand Herald and The Press by Dispensa & Brulle (Citation2003), Kenix (Citation2008), Howard-Williams (Citation2009) and Williams (Citation2010). Taken together, these findings show that New Zealand's major newspapers over the past decade have not given undue emphasis to claims challenging the scientific evidence for climate change, and for the most part have framed it in accordance with the scientific consensus position, as a legitimate and ‘real’ issue that demands a response.

In light of similar findings in recent studies around the world, the current study provides further evidence to suggest that quality newspapers have generally moved past questioning the scientific evidence for climate change; certainly a promising sign for advocates and science communication professionals working in the field of climate change communications (Carvalho Citation2007; Carvalho & Pereira Citation2009; Billett Citation2010; Takahashi Citation2011). By the same token, the current study further evidences the tendency to frame climate change in terms of ‘controversy’ and disagreement, which has been largely centred in the US media (Dispensa & Brulle Citation2003; Dirikx & Gelders Citation2009; Billett Citation2010). This study also highlights a contrast in New Zealand media coverage to the sensationalist emphases on potentially catastrophic ‘consequences’ (e.g. through omitting or underplaying uncertainties surrounding particularly extreme claims and projections) that have pervaded in coverage of climate change in the British and German presses (e.g. Ereaut & Segnit Citation2006; Grundmann Citation2007; Kenix Citation2008). Future studies may seek to further explore differences in how climate change has been framed in New Zealand versus other nations, with the experimental frame typology used in this study serving as a promising tool to allow for closer comparison with existing international data.

The complexity of framing effects means that it is not possible to infer with any certainty how the dominant media representations identified in this study might have shaped attitudes and perceptions of climate change among the New Zealand public. Nonetheless, the uncertainty and controversy that studies argue are likely to undermine public engagement and action to address climate change, have rarely been emphasised in New Zealand newspaper coverage (Corbett Citation2005; Lorenzoni et al. Citation2007; Morton et al. Citation2011). Rather, studies have suggested that an emphasis on the potential ‘gains’ to human health and the economy, as evidenced in the prominence of Social Progress and Economic Competitiveness frames, could in fact be effective in facilitating public engagement and action with regard to climate change (Shellenberger & Nordhaus Citation2009; Maibach et al. Citation2010; Spence & Pidgeon Citation2010). In other words, given the role the news media are understood to play in shaping public understanding of and attitudes towards scientific issues, we might expect the representations of climate change evident in New Zealand newspapers to facilitate public understanding and engagement on the issue (Bell Citation1994; Nelkin Citation1995; Wilson Citation1995). Some polls and surveys suggest that this is the case for a proportion of the population (e.g. TNS Conversa Citation2008; Stuart Citation2009). Whether this segment of the population in fact overlaps with the newspaper audiences opting to read stories on climate change is an interesting question for future research.

Despite this finding, the results of this study otherwise reflect something of a disconnect between aspects of the framing and presentation of climate change in New Zealand newspapers, and the apparently mixed and ambivalent attitudes and perceptions held by the public (ShapeNZ Citation2007). One interpretation of this finding could be that the dominant frames in New Zealand newspaper coverage around climate change resonate very differently with different New Zealanders. Indeed, audiences do not simply absorb or adopt the frames they are presented with, and far from a hypodermic model of media effects, the way in which frames are interpreted by individuals within differing political, economic or social contexts can vary widely (Gamson & Modigliani Citation1989; Entman Citation1993; Takahashi Citation2011). Interpretations of Political and Economic Competitiveness frames, for example, could vary significantly depending on the reader's trust in the current government's economic nous, or the industry they belong to, in turn reflecting the priority placed on addressing climate change.

There is also the possibility that the framing of climate change communications in other media channels has contributed to these ambivalent beliefs and attitudes. The findings of this research point to a need to further analyse coverage of climate change in television news and current affairs programming—the most widely cited source of science and technology news among the New Zealand public (ShapeNZ Citation2007)—as well as in news websites, blogs and social media. As news today is increasingly consumed across an array of formats and channels, analyses that span these formats could contribute to a more complete understanding of the set of frames that audiences are engaged with on climate change and other issues (Rosenstiel et al. Citation2014).

Paired with sensitive analyses of public attitudes and values, together with a nuanced understanding of media usage among specific audience segments, these insights could aid in the development of improved, targeted communication strategies to engage the public on climate change and similar science-related issues. In doing so, such strategies could perhaps help to facilitate efforts to stimulate bottom-up pressure for meaningful national and international measures to mitigate the threat of climate change.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding and support from the Centre for Science Communication at the University of Otago.

Notes

1. Although the terms ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’ are not technically equivalent, previous studies suggest that there is a tendency for them to be used interchangeably in news discourse. These search terms have been used across the majority of similar studies (e.g. Carvalho Citation2007; Boykoff Citation2008; Dirikx & Gelders Citation2010; Takahashi Citation2011).

References

- Adam D 2010. Climategate scientists cleared of manipulating data on global warming. The Guardian, 8 July. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/jul/08/muir-russell-climategate-climate-science ( accessed 28 January 2015).

- Anderson A 2009. Media, politics and climate change: towards a new research agenda. Sociology Compass 3: 166–182. 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00188.x

- Anderson A 2011. Sources, media, and modes of climate change communication: the role of celebrities. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews—Climate Change 2: 535–546.

- Antilla L 2005. Climate of scepticism: US newspaper coverage of the science of climate change. Global Environmental Change—Human and Policy Dimensions 15: 338–352.

- Armstrong J 2009. No date set for agriculture's inclusion in ETS. New Zealand Herald, 1 September, p. A004. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/climate-change/news/article.cfm?c_id=26&objectid=10594425 (accessed 9 February 2015).

- Ball-Rokeach SJ, DeFleur ML 1976. A dependency model of mass-media effects. Communication Research 3: 3–21. 10.1177/009365027600300101

- Barroso JM 2009. Now is the time to walk the walk, away from the abyss. New Zealand Herald, 22 September, p. A009. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/opinion/news/article.cfm?c_id=466&objectid=10598747 (accessed 9 February 2015).

- Bell A 1994. Climate of opinion—public and media discourse on the global environment. Discourse & Society 5: 33–64. 10.1177/0957926594005001003

- Billett S 2010. Dividing climate change: global warming in the Indian mass media. Climatic Change 99: 1–16. 10.1007/s10584-009-9605-3

- Bodansky D 2010. The Copenhagen climate change conference: a postmortem. American Journal of International Law 104: 230–240.

- Boehnert J, Andrews K, Wang X, Nacu-Schmidt A, McAllister L, Gifford L et al. 2014. World newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming, 2004–2014. Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado. http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/media_coverage ( accessed 27 October 2014).

- Boykoff M 2010. Turning down the heat: the politics of climate policy in affluent democracies. Environment and Planning C—Government and Policy 28: 569–570.

- Boykoff MT 2007. Flogging a dead norm? Newspaper coverage of anthropogenic climate change in the United States and United Kingdom from 2003 to 2006. Area 39: 470–481. 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2007.00769.x

- Boykoff MT 2008. The cultural politics of climate change discourse in UK tabloids. Political Geography 27: 549–569.

- Boykoff MT 2014. Media discourse on the climate slowdown. Nature Climate Change 4: 156–158. 10.1038/nclimate2156

- Boykoff MT, Boykoff JM 2004. Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press. Global Environmental Change—Human and Policy Dimensions 14: 125–136.

- Brossard D, Shanahan J, McComas K 2004. Are issue-cycles culturally constructed? A comparison of French and American coverage of global climate change. Mass Communication and Society 7: 359–377. 10.1207/s15327825mcs0703_6

- Bryant C 2009. The Pacific Islands on the road to Copenhagen. Opinion: British High Commission. Scoop World Independent News, 4 August. http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/WO0908/S00033/the-pacific-islands-on-the-road-to-copenhagen.htm(accessed 18 February 2015).

- Campbell RJ, Cleveland L 1973. Research notes: daily newspaper journalists in New Zealand. Political Science 25: 144–149.10.1177/003231877302500206

- Carvalho A 2007. Ideological cultures and media discourses on scientific knowledge: re-reading news on climate change. Public Understanding of Science 16: 223–243.

- Carvalho A, Pereira E 2009. Communicating climate change in Portugal: a critical analysis of journalism and beyond. In: Carvalho A ed. Communicating climate change: discourses, mediations and perceptions. Braga, Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade (CECS), Universidade do Minho. Pp. 126–156.

- Coates B 2009a. NZ's fair share of climate change effort. The Press, 8 August. http://www.celsias.co.nz/article/nzs-fair-share-climate-change-effort/ ( accessed 29 January 2015).

- Coates B 2009b. A cop-out in Copenhagen can be avoided if they try. The Dominion Post, 14 December, 2nd edition, p. 5.

- Corbett JB 2005. Altruism, self-interest, and the reasonable person model of environmentally responsible behavior. Science Communication 26: 368–389. 10.1177/1075547005275425

- Corbett JB, Durfee JL 2004. Testing public (un)certainty of science: media representations of global warming. Science Communication 26: 129–151. 10.1177/1075547004270234

- Coyle F, Fairweather J 2005. Challenging a place myth: New Zealand's clean green image meets the biotechnology revolution. Area 37: 148–158.

- D’Angelo P 2002. News framing as a multiparadigmatic research program: a response to Entman. Journal of Communication 52: 870–888. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02578.x

- Dew K 1999. National identity and controversy: New Zealand's clean green image and pentachlorophenol. Health & Place 5: 45–57.

- Dirikx A, Gelders D 2009. Newspaper communication on global warming: different approaches in the US and the EU? In: Carvalho A ed. Communicating climate change: discourses, mediations and perceptions. Braga, Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Universidade do Minho. Pp. 98–109.

- Dirikx A, Gelders D 2010. To frame is to explain: a deductive frame-analysis of Dutch and French climate change coverage during the annual UN Conferences of the Parties. Public Understanding of Science 19: 732–742.

- Dispensa JM, Brulle RJ 2003. Media's social construction of environmental issues: focus on global warming—a comparative study. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 23: 74–105. 10.1108/01443330310790327

- Doesburg A 2009. Absorbing ideas to combat warming. New Zealand Herald, 11 September, p. K018.

- The Dominion Post 2009a. Editorial: Lost opportunity on emissions deal. The Dominion Post, 16 September. 2nd edition, p. 4. http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/comment/editorials/2868063/Editorial-Lost-opportunity-on-emissions-deal (accessed 9 February 2015).

- The Dominion Post 2009b. Sea absorbs carbon. The Dominion Post, 14 November, p. 13.

- Entman RM 1993. Framing—toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Ereaut E, Segnit N 2006. Warm words: how are we telling the climate story and can we tell it better? http://www.ippr.org ( accessed 3 June 2014).

- Espiner C 2009. Climate conference visit unlikely—PM. The Press, 19 November. http://www.knowledge-basket.co.nz.ezproxy.otago.ac.nz/databases/newztext-newspapers/view/?d1=ffxstuff/text/2009/11/19/112224/doc00080.html ( accessed 28 January 2015).

- Falkner R, Stephan H, Vogler J 2010. International climate policy after Copenhagen: towards a “building blocks” approach. Global Policy 1: 252–262. 10.1111/j.1758-5899.2010.00045.x

- Fallow B 2010. The upside of climate change. New Zealand Herald, 21 January, p. B002. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=10621304 (accessed 9 February 2015).

- Gamson WA, Modigliani A 1989. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology 95: 1–37.

- Gibson E 2009. ‘Too soon’ to set binding NZ target. New Zealand Herald, 14 December. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10615360615360 (accessed 9 February 2015).

- Gordon JC, Deines T, Havice J 2010. Global warming coverage in the media: trends in a Mexico City newspaper. Science Communication 32: 143–170. 10.1177/1075547009340336

- Gray L 2009. Survival in the world's most vulnerable climate. New Zealand Herald, 7 December, p. A008.

- Greenberg J, Westersund E, Knight G 2011. Spinning climate change: corporate and NGO PR strategies in Canada and the United States. International Communication Gazette 73: 65–82. 10.1177/1748048510386742

- Grice A 2009. G8 agree on bold target for carbon emission reduction. New Zealand Herald, 10 July, p. A013. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/news/article.cfm?c_id=2&objectid=10583531 (accessed 9 February 2015).

- Grundmann R 2007. Climate change and knowledge politics. Environmental Politics 16: 414–432. 10.1080/09644010701251656

- Hardstaff P 2010. Rising degrees of uncertainty and temperature. The Dominion Post, 8 February, 1st edition, p. 5.

- Hasselmann K 2010. The climate change game. Nature Geoscience 3: 511–512. 10.1038/ngeo919

- Hood C 2010. Free allocation in the New Zealand emissions trading scheme. Policy Quarterly 6: 30–36.

- Howard-Williams R 2009. Ideological construction of climate change in Australian and New Zealand newspapers. In Boyce T, Lewis J eds. Climate change and the media. New York, Peter Lang. Pp. 28–40.

- Huck P 2009. Clean dream – a U.S. energy transformation. New Zealand Herald, 9 November, p. K012.

- Hulme M 2007. Newspaper scare headlines can be counter-productive. Nature 445: 818–818. 10.1038/445818b

- IPCC 2007a. Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. In: Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE eds. Climate change 2007. Cambridge, The Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Summary for Policymakers. Pp. 1–22.

- IPCC 2007b. Working group I: the physical science basis. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt K, Tignor MMB, Miller HL eds. Climate change 2007. Cambridge, The Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 996 p.

- Irvine E 2009. Mum's plans to help safeguard our planet. Bay of Plenty Times, 16 October, p. A028.

- Johnston M. 2009. Doctors attack climate change stance. New Zealand Herald, 9 October, p. A003.

- Kay M 2009. Key keeps to schedule despite Obama plan. The Dominion Post, 27 November. http://www.knowledge-basket.co.nz.ezproxy.otago.ac.nz/databases/newztext-uni/view/?d1=ffxstuff/text/2009/11/27/112242/doc00121.html ( accessed 28 January 2015).

- Kenix LJ 2008. Framing science: climate change in the mainstream and alternative news of New Zealand. Political Science 60: 117–132. 10.1177/003231870806000110

- Lorenzoni I, Nicholson-Cole S, Whitmarsh L 2007. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Global Environmental Change—Human and Policy Dimensions 17: 445–459.

- Maibach EW, Nisbet M, Baldwin P, Akerlof K, Diao G 2010. Reframing climate change as a public health issue: an exploratory study of public reactions. BMC Public Health 10: 299.

- McComas K, Shanahan J 1999. Telling stories about global climate change: measuring the impact of narratives on issue cycles. Communication Research 26: 30–57. 10.1177/009365099026001003

- McCright AM, Dunlap RE 2000. Challenging global warming as a social problem: an analysis of the conservative movement's counter-claims. Social Problems 47: 499–522. 10.2307/3097132

- McLean JD, de Freitas CR, Carter RM 2009. Influence of the Southern oscillation on tropospheric temperature. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 114: D14104.

- Ministry for the Environment 2009a. Climate change impacts in New Zealand. Wellington, Ministry for the Environment. http://www.mfe.govt.nz/climate-change/how-climate-change-affects-nz (accessed 11 November, 2014).

- Ministry for the Environment 2009b. New Zealand's 2020 emissions target. Wellington, Ministry for the Environment. http://www.mfe.govt.nz/publications/climate/nz-2020-emissions-target/index.html (accessed 11 November, 2014).

- Ministry for the Environment 2014. Climate change information: act and amendments. Wellington, Ministry for the Environment, NZ Government. http://www.climatechange.govt.nz/emissions-trading-scheme/building/policy-and-legislation/acts-and-amendments.html (accessed 12 November 2014).

- Morton TA, Rabinovich A, Marshall D, Bretschneider P 2011. The future that may (or may not) come: how framing changes responses to uncertainty in climate change communications. Global Environmental Change 21: 103–109. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.09.013

- Nelkin D 1995. Babies in bottles: twentieth-century visions of reproductive technology—Susan Merrill Squier. Isis 86: 619–621. 10.1086/357323

- Nerlich B, Koteyko N, Brown B 2010. Theory and language of climate change communication. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews—Climate Change 1: 97–110.

- The New Zealand Herald 2009. Climate for change. New Zealand Herald, 25 September, p. K012.

- Nicholson D 2009. Getting real about emissions. The Press, 28 August, p. 15.

- Nielsen KH, Kjaergaard RS 2011. News coverage of climate change in nature news and ScienceNOW during 2007. Environmental Communication—A Journal of Nature and Culture 5: 25–44.

- Nisbet MC 2010. Knowledge into action: framing the debates over climate change and poverty. In: D’Angelo P, Kuypers JA eds. Doing news framing analysis: empirical and theoretical perspectives. New York, Routledge. Pp. 43–83.

- Nisbet MC, Scheufele DA 2009. What's next for science communication? Promising directions and lingering distractions. American Journal of Botany 96: 1767–1778. 10.3732/ajb.0900041

- Olausson U 2009. Global warming—global responsibility? Media frames of collective action and scientific certainty. Public Understanding of Science 18: 421–436. 10.1177/0963662507081242

- Pan Z, Kosicki GM 1993. Framing analysis: an approach to news discourse. Political Communication 10: 55–75. 10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963

- The Press 2009. Key to dine in palace as Smith talks. The Press, 14 December, 2nd edition, p. 1.

- Rands M. 2009. What's good for the climate is also good for our health. New Zealand Herald, 2 November. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/opinion/news/article.cfm?c_id=466&objectid=10606665 (accessed 28 January 2015).

- Rosenstiel T, Sonderman J, Loker K, Tran M, Tompson T, Benz J et al. 2014. The personal news cycle. Chicago, The Media Insight Project. www.MediaInsight.org (accessed 11 November 2014).

- Russill C, Nyssa Z 2009. The tipping point trend in climate change communication. Global Environmental Change—Human and Policy Dimensions 19: 336–344.

- Shanahan M 2007. Talking about a revolution: climate change and the media. An IIED Briefing. London, International Institute for Environment and Development. http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17029IIED.pdf (accessed 9 February 2015).

- ShapeNZ 2007. New Zealanders’ views on climate change and related policy options. Auckland, NZ Business Council for Sustainable Development.

- ShapeNZ 2009. New Zealanders’ attitudes to climate change. National climate change survey of 2,851 New Zealanders conducted by ShapeNZ. Auckland, NZ Business Council for Sustainable Development.

- Shellenberger M, Nordhaus T 2009. The death of environmentalism: global warming politics in a post-environmental world. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 1: 121–163.

- Small V 2009. Treasury warns of ETS bill risks. The Dominion Post, 25 September, 2nd edition, p. 9. http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/news/politics/2900871/Treasury-warns-of-ETS-bill-risks (accessed 9 February 2015).

- Spence A, Pidgeon N 2010. Framing and communicating climate change: the effects of distance and outcome frame manipulations. Global Environmental Change 20: 656–667. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.002

- Stewart G 2009. In our hands to force change. New Zealand Herald, 2 October, p. A028.

- Stuart D 2009. Survey on public attitudes to climate change and the emissions trading scheme. Wellington, New Zealand, Greenhouse Policy Coalition.

- Takahashi B 2011. Framing and sources: a study of mass media coverage of climate change in Peru during the V ALCUE. Public Understanding of Science 20: 543–557. 10.1177/0963662509356502

- Taylor G 2009. NZ is now climate change laggard. New Zealand Herald, 28 September, p. A007. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/climate-change/news/article.cfm?c_id=26&objectid=10599933 (accessed 9 February 2015).

- TNS Conversa and The New Zealand Institute of Economic Research 2008. Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) research: national survey (quantitative): a summary of quantitative research amongst the general public. Auckland, New Zealand, TNS Conversa. http://nzier.org.nz/static/media/filer_public/ba/7c/ba7cba6d-2678-4084-807f-c9f2b943c72d/ets_tns_conversa_080707-1.pdf ( accessed 7 June 2009).

- Trumbo C 1996. Constructing climate change: claims and frames in US news coverage of an environmental issue. Public Understanding of Science 5: 269–283. 10.1088/0963-6625/5/3/006

- UMR Research 2010. Survey shows climate change ranks lowest among issues and concerns about its costs have risen. Press Release. Greenhouse Policy Coalition. http://www.gpcnz.co.nz/Site/News_Releases/GPC_survey_2010.aspx ( accessed 20 September 2010).

- Walsh S 2010. Standing up for climate change. The Press, 17 October. http://www.stuff.co.nz/the-press/news/2972259/Standing-up-to-climate-change ( accessed 29 January 2015).

- Watkins T 2009a. 2020 vision: drop emissions by up to 20pc. The Dominion Post, 11 August. http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/news/politics/2738240/2020-vision-Drop-emissions-by-up-to-20pc ( accessed 28 January 2015).

- Watkins T. 2009b. Climate change: $26pp a week. The Dominion Post, 27 July. http://www.stuff.co.nz/environment/2675509/Climate-change-26pp-a-week ( accessed 29 January 2015).

- Weingart P, Engels A, Pansegrau P 2000. Risks of communication: discourses on climate change in science, politics, and the mass media. Public Understanding of Science 9: 261–283. 10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/304

- Williams D. 2009. Seabed research to shed more light on climate change. The Press, 17 November, 2nd edition, p. 4.

- Williams D 2010. How a change in government affects climate change coverage at ‘The Press’. New Zealand Journal of Media Studies 12: 27–39. 10.11157/medianz-vol13iss2id45

- Wilson TA 1995. Media guide for academics—Rodgers, JE, Adams, WC. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 72: 970–971.

- Zehr SC 2000. Public representations of scientific uncertainty about global climate change. Public Understanding of Science 9: 85–103. 10.1088/0963-6625/9/2/301

Appendix 1 Quotes from New Zealand newspapers illustrating the frames analysed

1. Politics frame

(a) Political actors

President Barack Obama cleared the way for what Gordon Brown called an ‘historic agreement’ at the G8 summit in Italy by signing the US up to a firm emissions target for the first time—a complete contrast to the intransigence of his predecessor, George Bush. The G8 move is designed to revitalise United Nations-led talks on a global ‘son of Kyoto’ agreement, which reach a climax in Copenhagen in December. (Grice Citation2009)

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon and Yvo de Boer, head of the UN framework convention on climate change, will attend the biennial [Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting] in a sign of desperation for a deal on emissions targets and penalties to be signed off. There have been reports that French President Nicolas Sarkozy and Danish Prime Minister Lars Loekke Rasmussen may also attend CHOGM, which is the last major international summit before Copenhagen. (Kay Citation2009)

(b) Climate policy

Associate Climate Minister Tim Groser said draft texts tabled at the conference on Friday would not be acceptable to the developed world. ‘All the onus is now on the major developing-country emitters.’ New Zealand and other developed nations want developing countries to agree to cuts in ‘business as usual’ greenhouse gas emissions of between 15 and 30 per cent on 1990 levels. (The Press Citation2009)

The US says China does not need its money and the fund should go to the poorest countries. This sparked a bristling response from the Chinese. They said rich countries owed a debt for their decades of pouring greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, and called on the US to toughen its domestic target. US climate envoy Todd Stern took umbrage at the ‘debt’ suggestion, saying that for most of the last 200 years industrial countries did not know greenhouse gases caused global warming. (Gibson Citation2009)

The Maori Party either u-turns…Or it risks seeing a gutted emissions trading scheme which makes little impact on emission-cutting targets—the result if National has to turn to Act for support. The Prime Minister was yesterday making little secret that he intends playing off political friend and foe in such fashion. That modus operandi will be applied to Labour, too. That party is still indicating it is willing to be flexible about changing its own scheme to avoid it being watered down completely. But only up to a point. Its bargaining chip is time—or rather John Key's lack of it. The nature of the revised emissions trading system is now a simple game of parliamentary numbers. (Armstrong Citation2009)

2. Social Progress frame

(a) Citizens, community and business

Students at Christchurch's Rangi Ruru Girls’ School made a stand against carbon emissions yesterday, in support of an international climate change campaign. Almost 250 girls gathered in the school's gymnasium to form a human sculpture representing the number 350. The display showed support for the 350.org campaign that aims to raise awareness and encourage a reduction in carbon emissions. (Walsh Citation2010)

A Bethlehem mother-of-two is spearheading a climate change awareness event in Tauranga. Melany Clement has always been interested in the environment, but it wasn’t until she became a mother that she really started thinking about the long-term impact we have on the planet. And when she heard about climate change and the 350 movement, she knew she wanted to be a part of it. ‘It's just people getting together, standing up and saying “we have to do something about this”’. (Irvine Citation2009)

(b) Solutions and innovations

Clean tech and software companies…are racing to develop everything from algae biofuel to photovoltaic panels that absorb 10 times more energy from the sun than current models. Such projects mesh with Obama's belief that renewable energy will wean the US from imported oil, enhance national security, fight climate change and recharge the economy. (Huck Citation2009)

3. Economic Competitiveness frame

(a) Opportunities and costs

The draft bill shows the changes will cost taxpayers $415 million by 2013, before moving into the black over the next four years. However, as the price of longer-term assistance to big polluters takes effect, the bill for taxpayers blows out to $2 billion by 2030. (Small Citation2009)

The cost of doing our bit in the battle against climate change will be $27 a week each by 2020 as the Government prepares to sign Kiwis up to a global pact. (Watkins Citation2009a)

(b) Domestic emissions and the economy

Prime Minister John Key said yesterday that there needed to be a ‘healthy dose of realism’ between the cost to NZ of doing nothing, and the ‘huge economic implications both to NZ and the average worker's pocket’ of meeting the more ambitious 40% target’…‘Achieving these…reductions will mean higher costs for consumers and business for petrol and electricity. I’m not prepared to see an even higher target of minus 40 per cent, which our advice says will cost jobs for already struggling Kiwi families’. (Watkins Citation2009b)

Not only are the environmental risks high. Unless NZ produces a credible policy, it faces the serious risk of finding its tourist flights empty and its exports boycotted, or worse, shut out of overseas markets. …At the same time, New Zealand cannot cripple its economy with a policy so rigorous that it puts it at a disadvantage to its competitors. That would simply invite New Zealand industry to up sticks and set up where the restrictions on emissions were not so fierce. (The Dominion Post Citation2009a)

Climate Change Minister Nick Smith said the report [by the NZ Institute of Economic Research] highlighted that getting too far ahead of other countries raised the cost to New Zealand. But doing nothing was not an option either: ‘If we slip too far behind international efforts we damage our clean, green reputation and may put our export market access at risk’. (Watkins Citation2009b)

(c) Clean green brand

We need to take into account the costs of setting too low a target…We are putting our huge asset—our clean green brand—at risk by being one of the climate change pariahs in negotiations…Potential damage to our image from dragging our feet on climate change is enormous, as is the cost to our businesses if they fall behind international standards of good practice. (Coates Citation2009b)

You’d have also thought a business-savvy Government would realise the dangers such a weak response poses to our international reputation. As an exporting nation we’re very vulnerable to changes in purchasing behaviours caused by growing awareness about climate change and environmental performance. This is particularly so when our goods travel long distances to their markets. We could make a real virtue out of being truly 100% pure but instead we place our powerful, compelling national brand at risk by a limp response. (Taylor Citation2009)

(d) Potential opportunities

Business leaders have been pressing the Government to look on climate change not just as a risk to be managed or a cost to be allocated, but a potentially transformative opportunity to be seized…It is also about shoring up the national clean, green brand, which is increasingly under threat. And more broadly it is about reducing future risks to the economy ranging from oil shocks to carbon tariffs imposed on countries seen as free riders. (Fallow Citation2010)

There is not just a climate threat, but a climate opportunity as well. The 21st century must be the era of the low carbon green revolution. Thousands of green jobs, earning millions of dollars, are up for grabs. The country—or region—which recognises this will win business and export markets as well as help to save the planet from dangerous climate change. (Bryant Citation2009)

4. Science frame

Global warming has been blamed for the alarming loss of ice shelves in Antarctica, but a new study says newly exposed areas of sea are soaking up some of the carbon gas causing the problem. (The Dominion Post Citation2009b)

Deep holes drilled in the seabed off the Canterbury coast this summer will help scientists determine the link between climate and sea-level changes over the past 35 million years. (Williams Citation2009b)

The study, led by NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York…found methane and another pollutant, carbon monoxide, soaked up an atmospheric ‘scrubber’ called hydroxyl that would otherwise join other substances to make cooling aerosols. The sulphate aerosols elbowed aside by methane cooled the earth by scattering light and affecting the clouds. (Gibson Citation2009)

The facts on climate change and its causes remain unchanged. The overwhelming majority of scientists from all relevant fields continue to support the conclusion of climate science: the Earth is warming because of rising levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and this is a result of human activities such as deforestation and burning fossil fuels…There is, of course, uncertainty on the extent of climate change impacts. Projecting what will happen in different countries or ecological zones is not simple. (Hardstaff Citation2010)

Dr Renwick said there were already signs of wet places getting wetter and dry places getting drier…But that is on a global scale. ‘Teasing that out into how rainfall is going to change over the Wellington region versus Hawkes Bay, that is hard,’ said Dr Renwick…‘The smaller the scale you go to the more variable things are and the harder it is to pin down what is causing what—is this natural variability or is it climate change?’ (Gibson Citation2009)

5. Consequences frame

[Global warming] also increases the chances of catching the life-threatening diseases that are more prevalent in poorer countries…Warmer weather allows the bugs to move into previously unaffected altitudes, spreading a disease [malaria] that is already the biggest killer in Africa…Dengue fever has been expanding its range: its incidence doubled in parts of the Americas between 1995–97 and 2005–07. On one estimate, 60 per cent of the world's population will be exposed to the disease by 2070. (The New Zealand Herald Citation2009)

Climate change is happening faster than we believed only two years ago. Continuing with business as usual almost certainly means dangerous, perhaps catastrophic, climate change during the course of this century…We have less than 80 calendar days to go till Copenhagen. As of the Bonn meeting last month, the draft text contains some 250 pages—a feast of alternative options, a forest of square brackets. If we don’t sort this out, it risks becoming the longest and most global suicide note in history. (Barroso Citation2009)

The New Zealand Medical Journal recently published an article supported and/or written by more than 100 senior doctors, health professionals and health organisations calling for New Zealand to have more responsible targets and rapid action on climate change. We are faced with a future of worsening food and water shortages, and disasters arising from floods, droughts, storms and sea-level rise. All of these threaten our basic needs for health and survival, and the scale of the damage depends on the degree to which we act now to prevent catastrophic warming. (Stewart Citation2009)

6. Scientific Controversy frame

De Freitas said the research had found about 80 per cent of temperature change was caused by atmospheric circulation…‘We have used three sets of data…satellite data…radiosonde balloon data…and surface temperatures back to 1961.’ Renwick said he had talked about the paper with NIWA colleagues and their concerns were with the data and the conclusion. ‘They have used their favourite versions of the radiosonde data and don’t discuss the possible issues with some of the radiosonde and satellite data,’ Renwick said. (Shanahan Citation2007)

‘De Freitas said yesterday he had received congratulatory messages from overseas about the peer reviewed research. However, he was expecting a backlash this week from those who believed greenhouse gases were responsible for climate change’. (Shanahan Citation2007)

First, there was the hacking of emails…which show scientists behaving in ways that fall far short of the candour and integrity expected of top researchers. Then there was the disappointment of Copenhagen…And since then it has emerged that two rather startling predictions of climate-change disaster [referring claims in the IPCC report] turn out to rest on nothing more substantial than a magazine interview and an article by non-scientific members of a pressure group. (Espiner Citation2009)

January 2010: United Nation's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change retracts a claim in its 2007 report about the rate at which Himalayan glaciers will melt…December 2009: Leaked emails…prompted allegations that scientists were skewing climate data and withholding information.

In New Zealand, [NIWA] has been accused of altering its climate data, and has published online explanations of why it made the adjustments. (Nicholson Citation2009)

Imagine this scenario—a doctor sees a patient who has all the signs of pneumonia, a serious disease that can kill if not treated quickly. The doctor knows that the patient is likely to have pneumonia, but cannot be sure which germ is causing it without doing more tests—the results of which may take days to come back. What should this doctor do? Here's what doctors do in this situation—they start treatment anyway, as soon as they can. (Stewart Citation2009)

7. Morality frame

It's not just for ‘greenies’ and ‘tree huggers’. It's for grandparents who may already have a personal connection to the end of this century through precious little ones in their own family. It's for people who think the term ‘environmental refugee’ should not need to exist. It's for those who feel the Arctic's polar bears are more important than ice-free shipping lanes. (Stewart Citation2009)

Bangladeshis have one of the lowest carbon footprints per head in the world, at 1.1 tonnes a year, compared with 29 tonnes for the average American and 15 tonnes for Britons, yet they are suffering most from global warming. ‘It is time for rich countries to accept their responsibilities in terms of reducing emissions and providing assistance to developing countries that did not cause the problem but are going to suffer the consequences’. (Gray Citation2009)

If we do something that harms others, we should put it right, even if it costs us to do so…We are among a relatively small proportion of the world's population that caused the problem, and our industrialised countries grew rich from using cheap fossil fuels. Collectively, we have contributed about three-quarters of the world's greenhouse gases from human sources into the atmosphere. The injustice is that a billion of the world's poorest people…are responsible for just 3 per cent of global emissions, but are bearing the brunt of our pollution. (Coates Citation2009a)