ABSTRACT

An essay on North Island geology by J. Coutts Crawford (1817–1889) was published in the first issue of Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute in 1868. Regional geological studies of New Zealand at that time were few. However, Crawford’s outline of the geology of the North Island is creditably accurate, with the distribution of rock types and rock ages broadly correct. Although he lacked formal scientific training, Crawford was a valued and influential member of the Wellington science scene in the 1860s and 1870s, and played an active role in the early years of the New Zealand Institute/Royal Society of New Zealand.

Introduction

It is a pleasure and an honour to help mark the sesquicentennial of the Royal Society of New Zealand and its predecessor, the New Zealand Institute, in my capacity as a geologist and Senior Editor of the New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. Early New Zealand scholars published many geological papers in Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute (TPNZI) between 1868 and 1934. In the preface to volume 1, its founding editor James Hector (Director of the New Zealand Geological Survey and of the Colonial Museum) noted that, in addition to transactions submitted by the constituent provincial institutes, volume 1 contained eight essays, originally prepared for the New Zealand Exhibition hosted in Dunedin in 1865. One of these essays was written by James Coutts Crawford () and has the title ‘Essay on the geology of the North Island of New Zealand’ (Crawford Citation1865, Citation1868). Crawford’s essay is the basis for this retrospective consideration of New Zealand geology in the 1860s.

Figure 1. James Coutts Crawford. S. P. Andrew Ltd: portrait negatives. Ref: 1/1-013727-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23077708

As the title suggests, Crawford (Citation1868) is a synthesis. Today’s synthesis papers have to distil an abundance of data and interpretations into an honest, readable account. In the 1860s geological exploration of New Zealand was in its infancy and Crawford would have faced the opposite problem—huge data gaps and incomplete understanding.

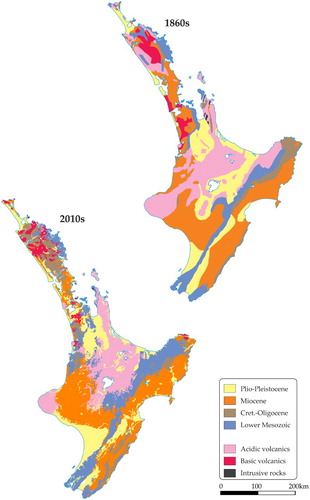

Crawford’s well-organised essay is c. 11,000 words, so longish but nevertheless of an acceptable length for the modern New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. As was fairly common for the time, but certainly not today, the paper has no diagrams, maps or illustrations. To provide a graphical comparison between the state of knowledge of North Island geology in the 1860s and 2010s, I have redrafted part of Hector’s (Citation1869) map on a modern base, and modified the 1:1 000 000 geological map of Edbrooke et al. (Citation2015) so its colour legend is identical to that used in the older map (). The use of Hector’s map is particularly appropriate as the version Hector prepared for the 1865 New Zealand Exhibition is entitled ‘Sketch Map of the Geology of New Zealand compiled to illustrate the geological essays of J.C. Crawford, J. Haast and J. Hector’ (Nathan Citation2014).

Figure 2. Simplified geological maps of the North Island. Upper: redrafted after Hector (Citation1869) in Nathan (Citation2014). Lower: Edbrooke et al. (Citation2015). The legend for both maps is based on Hector (Citation1869).

To make sense of Crawford’s essay, and evaluate it in context, some background information about Crawford is necessary. For this I have drawn heavily on Crawford (Citation1880) and short biographies by ‘Condor’ Citation1929 and Rosier (Citation1990). Following this I track the structure and subheadings of the original Crawford (Citation1868) paper, selecting some of the key observations he made and offering some commentary of my own.

Crawford’s life and times

James Coutts Crawford (referred to by himself and his contemporaries as Coutts) was born in Scotland in 1817, the son of a Royal Navy captain. He was educated at the Royal Naval College, Portsmouth, and served in the Royal Navy as a midshipman on the 120 gun HMS Prince Regent, in the Mediterranean and around South America from 1831–1836. He left the navy and, in 1838, sailed to Sydney. He first arrived in New Zealand in the schooner Success on 4 December 1839, making landfall at the Kapiti whaling station and travelling overland to Petone. For the next 20 years Crawford travelled between Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand, engaging in land purchases and stock activities and gradually building up his cattle farms in Wellington. In 1845 the Scottish geologist Hugh Miller introduced Crawford (then an employee of the New Zealand Company and already interested in geology) to a fellow Scot, the rising geologist Roderick Murchison (Stafford Citation2002).

Crawford settled permanently in New Zealand in 1857 and was active in local affairs and mining, cattle and flax investments. Murchison (by then Director-General of the British Geological Survey) recommended that Crawford be appointed Wellington Provincial Geologist (Stafford Citation2002), a post which he took up in 1861. In this role he became a peer of Haast and Hector who were provincial geologists in Canterbury and Otago, respectively. Crawford was the only person ever to have the title of Wellington Provincial Geologist; the post was disestablished in 1864 and the New Zealand Geological Survey, with Crawford’s full support, was founded in 1865 with Hector as Director. In his time as Provincial Geologist, Crawford explored the upper Whanganui, upper Rangitikei and Moawhango valleys, the Tokaanu area, Tararua Ranges and Wairarapa coast. Crawford wrote many reports on his trips (listed in Adkin & Collins Citation1967) and published a geological map of the Province of Wellington (Crawford Citation1864). Crawford’s lower North Island expeditions complemented Hochstetter’s 1858–1860 investigations in the Auckland region, central and upper North Island, and Nelson. Crawford’s tenure as Provincial Geologist did not result in significant finds of valuable natural resources such as gold, iron or coal that were considered important to New Zealand’s development at the time. This was not due to any shortcoming on his part, but simply because they do not exist in any abundance in the lower North Island.

As noted by Fleming (Citation1967), the New Zealand natural science scene in the 1840–1860s comprised visits by professional naturalists such as Dana, Hochstetter and Forbes, and important contributions by resident settlers who established a tradition of enthusiastic amateur science of whom Crawford was a leading example. Fleming’s use of the word ‘amateur’ may be a little harsh; although not professionally trained, these motivated local naturalists held meetings, exchanged ideas and published papers. Today we might call them avocational. Crawford made important and influential contributions to Wellington regional geology. He corresponded with Hochstetter, and regularly interacted with Hector and McKay, all prominent geologists of the time (Grapes et al. Citation2011).

Crawford was elected a member of the Geological Society (of London) in 1865. At various times he was a militia captain, an appointee to the New Zealand Legislative Council (effectively the upper house of parliament), President of the Wellington Philosophical Society, a governor of the newly-founded New Zealand Institute (the predecessor of the Royal Society of New Zealand), a justice of the peace, a magistrate and a sheriff. According to Adkin & Collins (Citation1967), Crawford published a total of 32 geological papers between 1855 and 1885, 22 of them in TPNZI. Crawford had broad interests and also published on botany, engineering, language and agriculture, and even coffee (Crawford Citation1876)! The 163 m high Mount Crawford on Wellington’s Miramar Peninsula is named after him. Crawford died in London in 1889, age 72.

Crawford (1868) revisited

Introduction

Crawford’s (Citation1868) North Island essay starts with an acknowledgment of earlier geological contributions by Ernest Dieffenbach, John Bidwill, Walter Mantell, Charles Heaphy, Charles Darwin, Charles Forbes, Arthur Thomson, William Lyon, Thomas Triphook, Reverend William Clarke and Ferdinand Hochstetter. There is a candid admission that his essay is a reconnaissance account, based largely on Hochstetter’s and his own observations.

Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks

Crawford recognised that the oldest rocks in the North Island were steeply-dipping sandstones and slaty rocks, some with plant beds, and some containing ‘jasperoid rocks and a little serpentine’. These underlay three main regions, the high axial ranges from Wellington to inland Hawkes Bay, the ranges north of the Cape Palliser area, and north, east and south of Auckland (). Crawford noted the uncertainty in their exact age and wrote that Hector considered a Mesozoic (c. 250–65 Ma) rather than Paleozoic (c. 540–250 Ma) age more likely—a surmise subsequently proven correct. Crawford also quoted verbatim Hochstetter’s description of fossiliferous Mesozoic strata on the Waikato coast, and added his own speculation that the Mesozoic Cape Palliser rocks were younger than those around Wellington.

Although the extent of the old basement rocks is now mapped more precisely, Crawford’s, Hector’s and Hochstetter’s outline was basically right (), as was their depiction of younger strata in the Waikato and Cape Palliser areas (Jurassic rather than Triassic; Edbrooke et al. Citation2015).

Cenozoic formations

Most of the North Island is underlain by Cenozoic (c. 65–0 Ma) sedimentary rocks. Crawford (and Hochstetter) recognised a basic motif that has been confirmed in most New Zealand sedimentary basins: coal measures overlain by limestone and then sandstone. Associated with the latter in the central and northern North Island are lava flows.

In a couple of places, Crawford refers to ‘the usual Tertiarys’ and ‘the usual Tertiary fossils’ (Tertiary is an old name for most of the Cenozoic), but the only mention of epochs is a quote by Hochstetter speculatively referring to Eocene (c. 56–35 Ma) and Miocene (c. 23–5 Ma). Crawford draws attention to limestone beds containing the bivalve mollusc Cucullaea singularis Zittel on both sides of the main ranges in the southern North Island, and offers interpretations of regional subsidence followed by uplift. It is worth pointing out that Crawford’s mention of Zittel’s naming probably would have come via Hochstetter (H. J. Campbell, GNS Science, pers. comm., December 2016): Crawford was very much up to date with the geological literature.

Given the rudimentary state of paleontology in the 1860s, it is a testament to Crawford’s knowledge and expertise that his account of the distribution of Cenozoic strata in the North Island area is still valid today. However, the name Cucullaea singularis is no longer used (Beu et al. Citation2012).

Volcanic rocks

Some things never change: Crawford (Citation1868) succinctly and accurately stated that the limits of volcanic rocks in the North Island lie north and west of a line between Mount Egmont, Mount Ruapehu and Whakatane. For his account of the volcanic rocks, Crawford quotes liberally from Hochstetter who thought Mount Egmont and Mount Ruapehu were extinct and that only Mount Tongariro and Mount Ngauruhoe were active. Crawford himself adds some text about hot springs.

The extent of siliceous volcanic rocks in and around Lake Taupō on the 1860s map is different than the 2010s version. In part this could possibly be due to lack of investigation at the time, or because of two somewhat subjective choices faced by the field geologist: 1. a volcanic versus sedimentary origin for reworked tuff and ash; and 2. how thick does a deposit have to be before it is shown on a map?

Of note to me as a petrologist is Hochstetter’s (and hence Crawford’s) liberal use of the words ‘trachyte’ and ‘trap’, and non-use of ‘andesite’ for the siliceous rocks that occur in the central North Island. A trachyte sensu stricto is a rock consisting essentially of alkali feldspar, of which there is almost none in the central North Island. In contrast, andesite (a plagioclase feldspar-rich rock) is abundant. According to Google Books Ngram Viewer (Google Ngram Citation2017) the term ‘trachyte’ has been in fairly common use since the 1820s, ‘andesite’ only since the 1880s. So trachyte was, at the time, probably an acceptable field name for generally feldspathic siliceous rocks. The lavas of the Wellington region are described as ‘trap’ (a now obsolete general term for basaltic volcanic and intrusive sheets) and Crawford interpreted them as dikes in the main ranges.

Terraces and raised beaches

Crawford notes that these are characteristic features of New Zealand geology, from pumice-stone terraces fringing the volcanic chain to coastal terraces, and many in between. The latest terrace uplift on the south coast, related to the 1855 earthquake, gets a special mention.

Gold

In the 1860s, the Coromandel was the only significant gold-producing area in the North Island, a situation that is still true today. Crawford lamented the extent of Cenozoic sedimentary cover in the North Island which covers the interior ‘and renders the search for gold difficult and uncertain’. Crawford erroneously repeated Hochstetter’s belief that the Coromandel gold came from quartz veins in Paleozoic strata and intrusions (). The actual situation is that quartz veins cut, and are related to, Miocene volcanic rocks.

Earthquakes

Crawford states, presumably as general geological knowledge of the time, that New Zealand is located on a long line of crustal weakness extending from Mount Erebus in Antarctica, through New Zealand, to New Guinea and Sumatra. Earthquakes occurred along this and other lines, but Crawford laments the lack of knowledge regarding why or when they happen. The strongest shaking in central New Zealand took place during the 1843, 1848, 1855 and 1863 earthquakes. Of these, Crawford was present in New Zealand only for the 1863 earthquake.

Comparison with Middle (South) Island

Crawford devotes a few lines to comparing the North Island geology with that of the South Island, particularly in regard to regional subsidence and uplift. He notes that the greater extent of Cenozoic strata in the North Island indicates greater submergence of the North Island compared with the South Island. Furthermore, he states the greatest depression was in the west side of the North Island and on the east side of the South Island. This insight is partially correct: his areas of greatest depression corresponding to what are now recognised as the Taranaki–Whanganui Basin and the Canterbury Basin.

Aerolites (meteorites)

As of 1865, one meteorite had been recovered in New Zealand—near the left bank of the Waingawa River close to Masterton. It was sent to the laboratory of the Otago Geological Survey at Dunedin, and was described by James Hector (Crawford Citation1868).

Dune formation

Three sentences on dune formation is a curious and abrupt way to end an essay on the geology of the North Island. Nonetheless, Crawford notes that the prevailing westerly winds confine extensive sand hills to the west coast.

Concluding remarks

The geosciences have matured considerably since Crawford’s time. Our present day knowledge of North Island geology is understandably much richer and more holistic. Geophysical techniques give us a 3D perspective of geology, and we recognise that active crustal movements (plate tectonics) control many aspects of North Island rock generation and deformation. Crawford’s (Citation1868) essay was an excellent summary of the state of knowledge of North Island geology. The inevitable fate of synthesis or review papers is that they are superseded within a decade by improved overviews that incorporate additional data and new ideas. Thus Crawford (Citation1868) would rapidly have been overtaken by the subsequent reports and maps of the national (as opposed to provincial) New Zealand Geological Survey geologists such as James Hector and Alexander McKay. By the same token, Hector openly acknowledged Crawford’s generosity in letting his lower North Island mapping be used in the national map (Nathan Citation2014).

Crawford’s (Citation1868) essay was both useful in its day, and also a stepping stone to further geological investigations. The value of a synthesis is that someone has made the effort to think things through at a different scale from the norm that most individuals address. As such it can trigger significant new perspectives and realisations. The broad similarity in the two maps of is testament that Crawford and his contemporaries made some shrewd calls and basically got the geology right. Science activities in 1860s Wellington clearly benefited from Crawford’s presence and influence. His Fellowship of the Geological Society, and his achievements as Wellington Provincial Geologist would have given him credibility as a governor of the fledgling New Zealand Institute, later to become the Royal Society of New Zealand.

Acknowledgements

I thank Ewan Fordyce for the invitation to write this paper. Earlier versions of the manuscript were improved by comments from Hamish Campbell, Ewan Fordyce, Mike Johnston and Rodney Grapes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Nick Mortimer http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6812-3379

References

- Adkin GL, Collins BW. 1967. A bibliography of New Zealand geology to 1950. New Zealand Geological Survey Bulletin. 65:243.

- Beu AG, Nolden S, Darragh TA. 2012. Revision of New Zealand Cenozoic fossil Mollusca described by Zittel (1865) based on Hochstetter’s collections from the Novara expedition. Association of Australasian Palaeontologists Memoirs. 43:1–71.

- “Condor” [nom de plume]. 1929. Makers of Wellington, pioneers of the ‘forties. XVI James Coutts Crawford. Evening Post. v. CVIII, issue 84, 5 October 1929 [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jan 17]. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19291005.2.68

- Crawford JC. 1864. Geological sketch map of the province of Wellington, New Zealand, and geological sections, province of Wellington, New Zealand. Christchurch: Ward and Reeves.

- Crawford JC. 1865. Essay on the geology of the North Island of New Zealand. Dunedin: Printed for the New Zealand Exhibition, 27 pp.

- Crawford JC. 1868. Essay on the geology of the North Island of New Zealand. Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. 1:305–328.

- Crawford JC. 1876. On New Zealand coffee. Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. 9:545–546.

- Crawford JC. 1880. Travels in New Zealand and Australia. Edinburgh: Ballantyne Press.

- Edbrooke SW, Heron DW, Forsyth PJ, Jongens R (compilers). 2015. Geological map of New Zealand 1:1 000 000. GNS Science Geological Map 2. Lower Hutt, New Zealand: GNS Science.

- Fleming CA. 1976. DSIR 50 guest editorial: earth science in the service of the state. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 19:1–7. doi: 10.1080/00288306.1976.10423545

- Google Ngram. 2017. Google Books Ngram Viewer [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jan 15]. Available from: https://books.google.com/ngrams

- Grapes R, Campbell HJ, Eagar S, Ruthven J. 2011. A history of the geology of Wellington Peninsula, New Zealand: an analysis of nineteenth to early twentieth century observations and ideas. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 41: 167–204. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2010.524227

- Hector J. 1869. Sketch map of the geology of New Zealand. Unpublished map, Archives New Zealand R17916896.

- Nathan S. 2014. James Hector and the first geological maps of New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 44: 88–100. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2013.877495

- Rosier L. 1990. ‘Crawford, James Coutts’, from the dictionary of New Zealand biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jan 7]. Available from http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/1c26/crawford-james-coutts

- Stafford RA. 2002. Scientist of empire: Sir Roderick Murchison, scientific exploration and Victorian imperialism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 297 pp.