ABSTRACT

This special issue reviews the state of biodiversity conservation in New Zealand, following the establishment of the Department of Conservation (DOC) in 1987. Here we summarise events that led to the formation of DOC, and the unprecedented series of changes in how biodiversity conservation has been viewed and conducted. Subsequent papers in this issue outline the successes, failures and key technological shifts in biodiversity conservation in New Zealand in the past 30 years; how visionary people and institutions have instigated conservation at landscape scales and in urban areas; the growing roles of Māori and non-Māori communities; and audacious new goals that reflect continuing attitudinal changes to the conservation of native biodiversity alongside the global and local implications of climate change.

Introduction

On 26 November 2004, the last known po’ouli (Melamprosops phaeosoma) died in a captive- breeding facility in Hawai’i. This honeycreeper, known only from the rainforest on the slopes of Haleakala volcano on Maui, had become known to science just 30 years earlier. Viewed from afar, an obvious question is: ‘How could the world’s largest economy allow this extinction to happen?’ The question bothered an investigative reporter, Alvin Powell (Citation2008), who found that the po’ouli’s demise was attributed to the usual agents: habitat degradation, disease, and introduced predators. But he found a fourth problem: extraordinary bureaucratic inefficiency, including disagreements between federal and state agencies, turf protection, personality clashes, and glacially slow decision making, which delayed tangible action to save the birds by six years. The structure of some responsible agencies made conflicts inevitable. For example, although po’ouli habitat destruction was largely due to rooting by feral pigs (Sus scrofa), the Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR), through their Division of Forestry and Wildlife, delayed construction of a fence that would exclude the pigs from sensitive habitat – even when the funds to do so were provided by the Federal Government. Perhaps the resistance was not surprising, given that DLNR gains some of its revenue from selling licenses for the public to hunt pigs. Rooting by the pigs was only part of the problem. Depressions in the churned-up ground can fill with water and provide a breeding ground for mosquitos carrying avian malaria. As Powell (Citation2008) recounts, the last known po’ouli had been infected by avian malaria.

Such convoluted approaches to environmental management are not unique to Hawai’i. Good fortune and a handful of dedicated individuals in the 1980s saved endemic New Zealand (NZ) birds such as black robin (Petroica traversii) and kākāpō (Strigops habroptilus) from the same fate as po’ouli (Butler and Merton Citation1992; Ballance Citation2007). The last known extinctions of NZ vertebrates were two species of bird and one of bat following the invasion of the Tītī Islands by ship rats (Rattus rattus) in the early 1960s (Bell Citation1978). Although lacking the state-federal divide experienced in the USA, NZ nonetheless had its environmental management spread across at least three independent agencies that not only competed with each other but also struggled with conflicting statutory requirements. For example, one section of the NZ Forest Service (NZFS) was responsible for harvesting native trees and converting forest to exotic plantations, while a second section was responsible for protecting these same native forests. As one Director General of NZFS admitted, it was an inefficient structure that led to ‘ … joint outputs [that] are likely to be in conflict … ., the highest attainable goal [being] a state of moderate dissatisfaction’ and a tendency for agencies to develop a ‘fortress mentality’ (Young Citation2004).

Unlike Hawai’i, however, the NZ public had become disillusioned by such inefficiencies and behind-the-scene deals between government and industry. Threats to raise the level of Lake Manapouri in Fiordland National Park as part of a hydro-electricity development generated public outrage. By 1987, this galvanised environmental activism had led to formation of the Department of Conservation (DOC) as replacement for fragmented conservation responsibilities lodged mainly in agencies focused on economic development (Young Citation2004). DOC was given a clear brief for biodiversity management on about 30% of the New Zealand landmass, as well as a mandate to advocate for indigenous biodiversity, a radical change indeed.

This special issue on the State of NZ Conservation examines the outcomes and continuing development of this conservation revolution. When the special issue was conceived in 2017, DOC had been in existence for 30 years. In recognition of this milestone, the following issue is largely about changes, challenges and opportunities that have arisen for the conservation of the nation’s biodiversity over these three decades. Our contributors have been asked to consider the following questions. How has NZ conservation management changed over the last 30 years? What are the successes and failures? And what challenges and opportunities lie ahead?

To provide context, we begin with a summary of the events that led to the formation of DOC through a brief precis from historical accounts and our own experiences. We then outline changes to environmental administration that followed the establishment of DOC; new responsibilities to facilitate guardianship by Māori; revolutionary changes in public sentiment, which have led to burgeoning community–based participation in conservation activities; new approaches to funding; and finally, collaborative approaches leading to new conservation initiatives at an unprecedented scale. For the purposes of this account we distinguish conservation administration (legal structures) from conservation management (implementation). We also assume that the term ‘indigenous species’ (identified in the Conservation Act and the Resource Management Act) refers to species endemic or self-dispersed to NZ; native species is used here as a synonym for those that are indigenous.

Conservation controversy and the establishment of DOC

The Department of Conservation emerged from a period when dissatisfaction at the lack of recognition and protection of the natural environment generated activism, protest and challenges to established views. As detailed by Young (Citation2004), a series of events in the decades before 1987 led to suspicion and sometimes public protests over impacts on indigenous species and habitats. Examples include: (1) prospecting on public lands, such as the proposal to reopen copper mine workings on Coppermine Island, despite the presence of a threatened tuātara (Sphenodon punctatus) population; (2) secretive deals between the government and Comalco® to provide electricity for the aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point while raising Lake Manapouri and drowning part of a National Park; and (3) the clearance of native forests on Crown land by government departments, including destruction of old-growth podocarp forests, which were converted to exotic pine (Pinus radiata) plantations, thus reducing habitat for threatened endemic birds such as the North Island kōkako (Callaeas wilsoni). In particular, the Save Manapouri campaign demonstrated the effectiveness of the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society (Forest and Bird) as an environmental lobby, led to reviews of environmental legislation, and culminated in the Reserves Act, 1977 and National Parks Act, 1980. Both Acts enhanced statutory support for biodiversity conservation by restricting access for extractive industry.

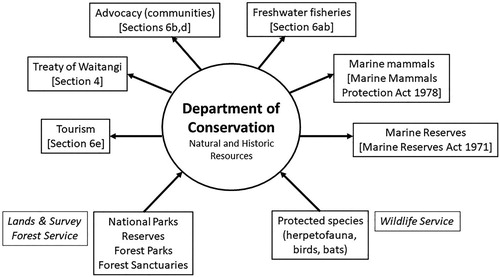

Public concern and environmental activism were also reflected in massive reconstruction of Public Services by the Labour government of 1984, which included radical changes to the administration of conservation and the environment. A single conservation management agency, DOC, was formed by consolidating environmental sections of an array of other government departments. The largest of these agencies were the Department of Lands and Survey (L&S), NZ Forest Service (NZFS), and the Wildlife Service (WLS). Fragmented responsibilities for biodiversity management among the previous agencies had almost ensured failure to protect biodiversity (). For example, WLS was responsible only for protected terrestrial vertebrates, but for virtually none of their habitats. Competing bureaucracies guaranteed conflicts to the detriment of threatened species and habitats. With responsibilities for land (habitats) largely vested in L&S or NZFS, access by WLS to protected fauna within their habitats was at the mercy of bureaucrats within (or associated with) the other departments. Delays and obfuscation were common. Decisions by land management agencies often appeared to have little concern for biodiversity, and there was no recourse if one of these departments destroyed the other’s resources. As one ex-field officer recounted, WLS staff could only watch when NZFS destroyed tracts of forests that had just been surveyed for birds (A. Saunders, Waikato Regional Council, pers. comm.). On the other hand, WLS maintained hatcheries for stocking fresh waters with introduced salmonids, but ignored their potential effects on indigenous species. Similarly, while WLS encouraged farmers to create wetlands for waterfowl, L&S had advised (and participated in) wetland drainage for farm development. With different historical responsibilities, each department’s environmental staff thus entered DOC with their own legislation, culture and history of contradictory land and biodiversity management ().

Table 1. Government departments that became the primary contributors of staff and expertise to the formation on DOC based on the personal experience of KB, ST and DRT respectively.

Radical new approaches to conservation administration

The early years of DOC

Unsurprisingly, the first two years of DOC’s existence were chaotic, with budget blowouts, restructuring and staff layoffs, reducing staff from >2000 to 1400 (Young Citation2004). The remaining staff had to cope with the unfamiliar and revolutionary responsibilities embedded in the new Conservation Act 1987 (). First, the Act required DOC to take over management responsibilities for wild and scenic rivers, freshwater fisheries and their habitats, protected marine mammals and marine reserves – but also to advocate for conservation, at the time a unique and almost revolutionary role for a Government Department in NZ. Furthermore, the way conservation policy developed changed. Instead of the ‘fortress mentality’ developed in some of DOC’s parent agencies, the public could now be involved in decisions over conservation policy through a network of regional Conservation Boards and a national Conservation Authority, which provided a communication pathway to regional DOC authorities as well as independent advice to the Minister of Conservation (Anon Citation2002). But a particularly audacious and challenging requirement was for DOC to give effect to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (Section 4 of the Act). This directive, along with a similar one in the Environment Act passed in 1986 (see below), meant that almost 150 years after the Treaty was signed with Māori in 1840, two government agencies were required to recognise the fundamental roles of Māori in management of natural resources.

Figure 1. Responsibilities for conservation of natural resources acquired by the Department of Conservation, with historic responsibilities of the three main contributing agencies (italics, inward arrows) and new responsibilities either defined as Sections within the Conservation Act or gained (with their statutory responsibilities) from other government departments.

Within DOC, tight budgets were further restricted as the government set targets for cost recovery. Tourism was promoted as a means of generating revenue, but businesses could no longer operate on public land administered by DOC unless they paid a concession (Anon Citation2002). Links established to large NGOs such as Forest & Bird and World Wildlife Fund NZ were broadened as engagement and cost savings were sought through community involvement in conservation activities. The latter took two forms: encouraging communities to take up their own conservation initiatives on DOC land and seeking corporate sponsorship for high profile threatened species (Young Citation2004).

By the mid-1990s, DOC had already made considerable progress with organisational development and with protecting species and habitats (Anon Citation2002). New methods for eradicating introduced pests such as rats from island Nature Reserves were developed, assisted by an infrastructure that facilitated communication with communities and iwi (Māori tribes), as well as a national development strategy aimed at increasingly ambitious pest eradication targets (Towns and Broome Citation2003). Furthermore, substantial corporate sponsorship was obtained for iconic species, notably kakapo and kiwi (Apteryx spp.). Recovery groups, which laid out strategy for future work on the more threatened and at-risk species, were also developed for a range of species, including kākāpō, kiwi and tuātara (Sphenodon punctatus; Nelson et al. Citation2019).

But difficulties also became apparent. Technical assistance for the recovery of protected species was still largely confined to terrestrial vertebrates, especially iconic birds. Neither capacity nor funding was available to seriously address issues affecting many other NZ species, although their needs were mostly unclear because threats had not been assessed. Furthermore, from inception, DOC faced limited capacity to undertake conservation of threatened plants and invertebrates or to deal with threats to freshwater and marine ecosystems.

As DOC attempted to grapple with these limitations, tragedy struck. The collapse of a viewing platform built by DOC staff as a team-building exercise in April 1995, killed a staff member and 13 teenage students. Unsurprisingly, DOC’s activities and administrative structures were reviewed once more. The so-called Cave Creek disaster revealed a culture of ‘making do’ on limited budgets (Gregory Citation2008), and the department was restructured yet again (Anon Citation2002). Funds for biodiversity tightened further as DOC gave priority to infrastructure improvement, health and safety training, and employment of building inspectors and structural engineers.

The culture of ‘making do’ on limited budgets was reactivated in DOC when the government cut at least $29 million from its budget after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. Almost 100 staff were laid off, those remaining were subjected to yet another (but particularly ill-conceived) deep restructuring, and external consultants were engaged to retrieve what was described as a ‘train wreck’ (Williams Citation2018). The government’s operational vote for conservation then remained around $350 million until a change of government was followed by an increased allocation to $400 million in fiscal year 2018–19 (DOC Citation2019).

It took 20 years and at least three iterations to develop a comprehensive process for assigning conservation threats to native species. The NZ threat classification system was broadly based on assessments developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), but does not assign priorities for action (Townsend et al. Citation2008). Although the DOC system could assess threats for all native organisms from fungi to bats, government funding had already been committed to the more charismatic vertebrates (Hare et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, the causes of these threats such as habitat loss and the effects of invasive species spread well beyond DOC’s responsibilities on public land. A mechanism for wider involvement of landowners and other land administrators was needed.

Complementary environmental administration?

A second piece of legislation facilitated new approaches to conservation problems. The Environment Act 1986 came into effect in January 1987, four months before DOC began, but its implications and effectiveness were only later to become fully apparent. The Environment Act created the office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE). Appointed by Parliament, the Commissioner is required to provide independent reports on environmental issues and threats, but also the effectiveness of agencies managing natural and physical resources. The Act also established the Ministry for the Environment (MfE), required to advise the Minister for the Environment on how best to monitor and assess environmental impacts, pollution control and hazardous substances (Environment Act, 1986). However, it was the fundamental change to planning regulations as laid out in the Resource Management Act (RMA) in 1991, and administered by MfE, that had particularly wide-ranging implications.

The RMA was intended as a mechanism through which urban and rural planning rules would guarantee citizens access to the services provided by ecosystems while minimising effects on the environment through sustainable management. As Young (Citation2004) recounts with some irony, it was touted as far-sighted environmental legislation released to an astonished world. However, fundamental to the legislation were environmental deregulation and devolution of responsibilities to Territorial Local Authorities (TLAs) with oversight from Regional Councils. This devolution led to two problems: (1) TLAs felt empowered – and perhaps encouraged through government’s aims at devolution – to interpret the regulations in ways that suited them, leading to inconsistencies across regional boundaries; (2) because officials leading the TLAs and Councils were elected, they often included, or became dominated by, the very people responsible for environmental degradation (Brown et al. Citation2016).

Central government had thus developed sophisticated and radical planning guidelines, but devolved enforcement and management to local authorities that often neither understood nor effectively implemented this vision (Young Citation2004). In some rural communities, this devolution meant ‘business as usual’ with light-handed approaches to the harmful environmental consequences of changing farming practices, such as conversion from sheep to dairy farming and stock level intensification (Foote et al. Citation2015). Over the short duration of the RMA thus far, urban and rural water quality has deteriorated to levels that make it a primary public concern according to a Colmar Brunton poll conducted in 2017 by Fish and Game New Zealand (Cosgrove Citation2018). The decline has also increased threats to an array of aquatic species (Hare et al. Citation2019) as well as the freshwater fisheries for which DOC is responsible.

Opportunities and alliances

Despite these issues, the new statutes had many positive outcomes. The Conservation Act and RMA were complementary pieces of legislation with far-reaching potential if the three arms of environmental management – DOC, MfE and PCE – could work together. Tangible evidence of this collaboration came with development of the NZ Biodiversity Strategy (NZBS) in partial fulfilment of obligations under the Convention on Biological Diversity for which NZ became a member in 1993 (Anon Citation2000).

The NZBS was developed after a state of environment report (Taylor Citation1997) to the PCE methodically documented the historic declines of indigenous biodiversity and warned of further declines due to the direct and indirect effects of marine harvesting, terrestrial ecosystem degradation and penetration by invasive species. The NZBS aimed to reverse these declines, restore viable populations and maintain their genetic diversity (e.g. Nelson et al. Citation2019; Wallis Citation2019). Key requirements for this reversal were identified (Anon Citation2000) as: (1) shared responsibility, in which the community at large should understand that biodiversity declines were their problem to be shared with government and (2) understanding the implications of the Treaty of Waitangi in which interests of iwi in biodiversity should be protected (e.g. Lyver et al. Citation2019). Progress with halting biodiversity decline, protecting interests of iwi, and sharing actions and responsibilities with the community are reported annually by DOC to parliament (e.g. Anon Citation2017).

Completion of the NZBS was also an incentive for government to mandate environmental outcomes through its research funding. Crown Research Institutes such as Manaaki Whenua/Landcare Research, often in partnership with universities, were thus empowered to take a strategic approach to biodiversity conservation. For example, multi-institutional teams were funded for the development of novel and more humane toxins for use against invasive mammals (Murphy et al. Citation2007), new methods of pest control (Blackie et al. Citation2014) and increased understanding of the behavioural responses by invasive species to intensive management (Ruscoe et al. Citation2011). Other multiagency research was directed towards understanding how entire ecosystems function and how they were modified by introduced mammals (e.g. Fukami et al. Citation2006).

The quiet revolution: guardianship for Māori

With specific requirements to give effect to principles of the Treaty of Waitangi enshrined in their statutes, government environmental agencies needed to accommodate the aspirations of iwi into their decision making. The Māori liaison sections of DOC quickly established pathways for understanding and communicating with local iwi. When processes for settlements of historical grievances were recommended by the Waitangi Tribunal, DOC was thus well placed to implement them. One of the first settlements was for a high-profile Nature Reserve, Takapourewa/Stephens Island, which holds by far the largest extant population of tuatara. The Deed of Settlement signed in 1994 establishes a co-management agreement with Ngāti Koata where the iwi are recognised as the tangata whenua (people of the land) with historical association with the island, and provides them with consultation rights for all management and access to the island (Cree Citation2014).

Other forms of agreements for island reserves have followed. Some, such as Te Hauturu-o-Toi (Little Barrier Island) and four other islands in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, have been supported with their own Acts of Parliament, which enshrine the mana (prestige, moral authority) of ownership with the relevant iwi and accept the need for co-management mechanisms. These changes have not directly affected the public at large, the flora and fauna of the islands, nor the level of protection they have been given. But they have returned to tangata whenua a mandatory voice and role, which in the case of Te Hauturu-o-Toi, had been denied to the local iwi, Ngāti Manuhiri, for at least 100 years. Other protected areas have followed, including the revesting of Te Urewera National Park to Tuhoe, and more such agreements are likely. More importantly, the 2011 ruling by the Waitangi Tribunal (Wai 262) on biodiversity emphasises that governments should facilitate kaitiakitanga (guardianship) of natural resources by Māori. Innovative recognition of relationships between iwi and places have since been recognised with entire landscapes and waterbodies now persons in law. Examples include Whanganui River, Te Urewera Forest and the maunga (mountain) of Taranaki (Warne and Svold Citation2019) This realignment of responsibilities and perceptions of place are now raising a new set of opportunities and challenges (Lyver et al. Citation2019).

Communities mobilised and divided

With encouragement from DOC and later by Regional Councils through the NZBS, community groups of varying sizes have developed their own projects for biodiversity conservation. One of the earliest of these was the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi. Their 1500 volunteers, alongside DOC, have funded and managed an entire island ecosystem, including forest replanting, animal translocations, pest eradication and weed control (Galbraith Citation2013). The Tiritiri Matangi project is now seen as a model for community participation and partnership with DOC, and has become an important destination for nature tourism, awareness raising about NZ biodiversity and conservation education (Butler et al. Citation2014). Recent estimates identified at least 600 community groups active on public land administered by DOC (Peters et al. Citation2015) and up to 4000 when private, iwi and locally governed lands are included (Butler et al. Citation2014). By any measure, this is an extraordinary global example of community mobilisation (e.g. Innes et al. Citation2019).

Despite earlier confusion over application of the RMA, several Regional Councils developed their own biodiversity strategies, with ambitious targets for conservation in partnership with the citizens in built urban landscapes (e.g. Wallace and Clarkson Citation2019). Given the rapid return of indigenous biodiversity to islands after introduced mammalian pest removals (e.g. Jones et al. Citation2016), community groups realised the potential benefits of comprehensive mammal control on the mainland, including eradications of most invasive species and the recovery of native ecosystems within predator-exclusion fences. Seizing the initiative, these groups raised their own funds and developed and tested fencing technologies, which were rapidly deployed. The first fenced sanctuary, 225 ha in the catchment of Karori Reservoir, Wellington (now Zealandia), was completed in 1999. Modified construction methods led to the establishment of commercial fence construction enterprises, with the longest fence of 47 km completed around 3400 ha of forest at Maungatautari in 2006 (Butler et al. Citation2014). Most of the fenced sanctuaries have been catchment-based, and some are larger than most offshore islands now cleared of mammals (Innes et al. Citation2019). Regional Councils and local authorities are now supporting many of these initiatives because the urban ones, such as Zealandia in Wellington, have spill-over or ‘halo’ effects that expand the growing range for native biodiversity well beyond the sanctuary boundaries (Innes et al. Citation2019). By re-creating insular sanctuaries on the mainland, not only did the thinking and practice of conservation change, but public consciousness of the rarest national treasures has been raised. Many New Zealanders now experience the excitement of having populations of long-absent native bird species return to their gardens, replacing destructive, introduced brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula). Initiatives aimed at intensive management or exclusion of introduced predators are now established in Auckland, Hamilton, Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin, and other cities are following as well.

But as the number and scale of these ventures has increased, so has limited but focused orchestrated resistance to the notion of invasive mammal control. This resistance has now taken the form of a militant backlash by some hunters and a range of groups opposing the use of toxins such as Compound 1080, which can be spread by helicopters. Hansford (Citation2016) found that the tactics of these groups often paralleled those used by climate change deniers: heavy use of grey literature, quotations out of context, conspiracy theories, disinformation and the use of social media to spread their ‘alternative facts’. Opponents have threatened acts that amount to eco-terrorism, including re-introducing pests into locations from where they have been cleared, including offshore islands free of invasive mammals (Hansford Citation2016). The low risks of 1080 and its unique efficacy for biodiversity protection in NZ where indigenous terrestrial mammals did not occur were outlined in meticulous PCE reports to Parliament (Wright Citation2011, Citation2013). These landmark reports recommended increasing (rather than decreasing) the use of 1080 until better means for dealing with invasive predatory mammals became available (Wright Citation2013). Opponents to the use of 1080 have largely ignored conclusions from the PCE reports, and active opposition, including street marches in late 2018, has continued.

Nonetheless, community-based engagement in predator removal and biodiversity enhancement has continued to grow. These initiatives are now being supported by business, philanthropists and public figures in support of a national vision for coordinated invasive predator control. All major political parties have supported this groundswell.

From sponsorship to philanthropy

DOC sought sponsorship to aid in conservation activities soon after its formation in 1987. In 1990, the same aluminium smelting company associated with plans to raise Lake Manapouri (Comalco®) began sponsorship of the kākāpō recovery programme, only concluding its support after 25 years and donations of $NZ 4.5 million (Hobson Citation2015). The kākāpō programme is now sponsored by Meridian Energy® Other species supported by multi-year sponsorship agreements include all seven species of kiwi (Apteryx) through the Bank of New Zealand, kōkako through State Insurance® and the Norwich Union Group®, whio (Hymenolaimus malachorynchos) through the electricity supplier Genesis® and takahē (Porphyrio hochstetteri) through the infrastructure construction company Fulton Hogan®. With annual contributions estimated at NZ$ 1.3 million this focus on large, charismatic birds has the inherent risk of funding for threatened species based on social attractiveness (Bennett et al. Citation2015). Management agencies may also feel pressure to divert funds from other deserving but less charismatic species (e.g. Hare et al. Citation2019). Nonetheless, sponsorship funding for charismatic ‘flagship’ species can build public awareness and support extensive habitat restoration that benefits other threatened species (Bennett et al. Citation2015).

In contrast to offshore islands, habitat restoration through pest control (rather than eradication) in mainland ecosanctuaries (sensu Innes et al. Citation2019) requires very long-term commitment (and partnerships) between government agencies and community groups that may be difficult to sustain. Numerous island examples globally and from NZ have demonstrated the efficacy of pest eradication rather than control (Jones et al. Citation2016). Attempts to replicate these examples on the mainland have involved a shift towards species management within large habitats or ecosystems and have been accompanied by the first substantial philanthropic approaches in NZ to biodiversity conservation. Instead of the modest goals of reversing declines in the abundance of selected species, a new generation of wealthy and financially well-connected visionaries has urged more audacious undertakings, including conservation on landscape scales, the development of new technologies, and heavy investment in education and social engagement (see also Innes et al. Citation2019) so that such projects are more likely to have a financially and socially sustainable future.

Industrial strength conservation: predator-free New Zealand

In a 2012 public address, the eminent physicist, Sir Paul Callaghan, challenged New Zealanders to get serious about conservation of their natural heritage by removing invasive mammals at the scale of 100,000’s of hectares. He also proposed scaling this up and ‘getting rid of the lot’ throughout the entire country starting with Stewart Island/Rakiura (Priestley Citation2012). A similar observation – that we may be aiming too low with pest eradication – was made previously by Simberloff (Citation2002). Calling this proposal his ‘crazy idea’, Callaghan said it could be ‘New Zealand’s Apollo Mission’.

The challenge was first accepted by the economist Gareth Morgan, through the Morgan Foundation. Morgan challenged DOC and the 400 residents of Stewart Island (174,600 ha) to develop a plan for the world’s largest island free of invasive predators, a campaign called Predator Free Stewart Island (https://www.morganfoundation.org.nz/predator-free-stewart-island-whats-next). Feasibility, costings and plans for a predator-proof fence were completed, but this NZ$ 50 million project faltered. A new commitment to predator-free Stewart Island was announced in 2019 following signing of a memorandum of understanding between iwi, Government (DOC), Southland Regional and District Councils, a major tourism operator and an organisation representing recreational hunters (Edwards Citation2019).

Other projects supported by philanthropists have already been completed or are underway, often in partnership with DOC, regional councils or both (). Some of the figures are extraordinary. For example, the NEXT foundation has pledged $NZ 100 million over 10 years for the development and implementation of conservation initiatives. The four mainland examples listed here involve almost 95,000 ha () and funding likely in excess of $NZ 50 million. The government has also endorsed the concept of a Predator-Free NZ by 2050 (PFNZ 2050), with funding for technical development and a nationally coordinated ‘science challenge’ (Clarke and Russell Citation2019; Peltzer et al. Citation2019). Sadly, Sir Paul Callaghan died a month after his seminal address. His legacy is a philanthropic, institutional, government and public conservation movement that has embraced his national ‘Apollo Project’ (Priestley Citation2012). Furthermore, government support for PFNZ 2050 acknowledges community views that native species deserve special attention in the face of threats from invasive imports, which belatedly should be viewed as a commitment under the Treaty of Waitangi (Peltzer et al. Citation2019).

Table 2. Recent examples of large projects for conservation of biodiversity supplemented by philanthropic support, all of which have strong iwi involvement including participation in governance. Those involving Morgan and NEXT Foundations involved proportional matching of institutional, corporate or public funds (e.g. NEXT Foundation is $1 Foundation:$3 other).

Outline of this special issue

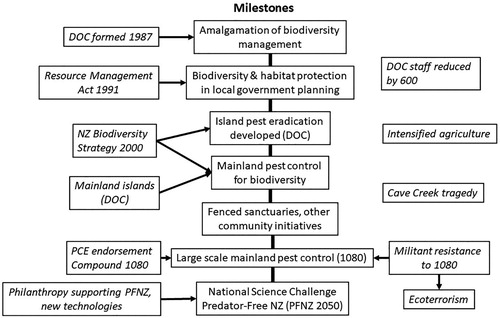

In 1987, the government made a bold move to ‘join the green dots’ of fragmented conservation responsibilities spread across a fractious array of departments (Young Citation2004). By itself, the move was revolutionary. But extraordinary changes in public attitudes and a range of additional legislative reforms have, within a generation, instigated a cascade of unprecedented and unanticipated advances, new opportunities and innovative approaches to the New Zealand conservation landscape ().

Figure 2. Milestones and their influences in the evolution of conservation planning for New Zealand biodiversity with events on the left side of the figure providing support and those on the right as major impediments.

The papers in this special issue detail the successes, failures, opportunities and challenges that have arisen as these changes gained momentum during the last 30 years. The accounts are prefaced by a guest contribution (Simberloff Citation2019) that emphasises the components of NZ conservation with international influence including a review of the role of invasive species in NZ ecosystems, the way attitudes to them have changed, and the influence of technical advances in NZ on invasive species management elsewhere. The remaining contributions focus on conservation issues within NZ. The first of these, by Nelson et al. (Citation2019), provides examples of successful species-based conservation activities – often following predator control or management. A companion paper follows, where examples of less successful activities are identified despite, for some of them, the application of considerable effort (Hare et al. Citation2019). Many of the successes with threatened species, new understandings of biogeography and phylogeny, and even innovative methods for tracking invasive species were aided by technical advances in conservation genetics (Wallis Citation2019), which is the fourth paper that focuses on biodiversity.

The remaining four papers are based on another set of key elements in conservation: social licence, or the ways in which buy-in, participation and support for biodiversity conservation have been – and could be – generated by people, local authorities, and commercial interests. The first of these describes success with forest regeneration within an urban environment (Wallace and Clarkson Citation2019), and is followed by an analysis of the scope and outcomes of unfenced and fenced sanctuaries, most of which were initiated and funded by the public (Innes et al. Citation2019). Perspectives of the way iwi can contribute and legal instruments that could make this possible are provided by Lyver et al. (Citation2019). The last of the reviews focuses on the concepts and issues that will need to be addressed if predator management is to be scaled up towards a Predator-Free New Zealand (Peltzer et al. Citation2019). The issue concludes by looking to the next 30 years, describing the enormous and growing challenges ahead and asks if the present momentum can be sustained and enhanced during the next 30 years (Daugherty and Towns Citation2019). Past biodiversity conservation in NZ benefitted from NZ’s geographic isolation, able to focus internally without the need to engage with other countries on any scale in managing our biological heritage. Global climate change as well as growth in transportation, trade, and tourism mean that NZ is no longer isolated from international challenges. How we address these new challenges will determine the fate of our indigenous species and ecosystems.

A final question: would Hawai’i still have the po’ouli and six other species of forest birds (see Powell Citation2008) had there been attitudinal changes and reforms to conservation agencies similar to those over the last 30 years in NZ? Of course, it is a question that has no answer. Experiences in NZ do, however, provide hope for others and a glimpse of the attitudinal evolution behind comprehensive approaches to invasive species management. In sum, NZ conservation has shifted from a small number of visionaries late in the nineteenth Century (Young Citation2004) to a motivated public developing their own initiatives and respect for nature. As papers in this issue indicate, there is at last awareness of cultural intersections between Māori and non-Māori views of the natural environment. There will be resistance from some who see these revolutionary changes as a threat. The challenge now is to find ways to accommodate voices of the sceptics to the burgeoning support for Sir Paul Callaghan’s ‘crazy idea’ (Priestley Citation2012).

Acknowledgements

The issue was conceived by the editorial staff of the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand and generously assisted by financial support from Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research through the NZ Biological Heritage Science Challenge. As Guest Editors for the Special Issue, Towns and Daugherty thank the many authors who have contributed their special knowledge to the broad scope of issues included in this issue. We thank Alison Cree and Sally Bryant for their thoughtful suggestions for improvements to this manuscript and Kelly Hare who stepped in as handling editor for this contribution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Anon. 2000. New Zealand biodiversity strategy. Wellington: Department of Conservation and Ministry for the Environment.

- Anon. 2002. A guide to the Department of Conservation Vol. 2. Wellington: Department of Conservation.

- Anon. 2017. Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai annual report for the year ending 30 June 2017. Wellington: Department of Conservation.

- Ballance A. 2007. Don Merton. The man who saved the black robin. Auckland: Reed.

- Bell BD. 1978. The Big South Cape islands rat irruption. In: Dingwall PR, Atkinson IAE, Hay C, editors. The ecology and control of rodents in New Zealand nature reserves. Department of Lands and Survey Information Series No. 4:33–40.

- Bennett JR, Maloney R, Possingham HP. 2015. Biodiversity gains from efficient use of private sponsorship for flagship species conservation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282:20142693.

- Blackie HM, MacKay JWB, Allen WJ, Smith DHV, Barrett B, Whyte BI, Murphy EC, Ross J, Shapiro L, Ogilvie S, et al. 2014. Innovative developments for long-term mammalian pest control. Pest Management Science. 70:345–351.

- Brown MA, Peart R, Wright M. 2016. Evaluating the environmental outcomes of the RMA. Environmental Defence Society.

- Butler D, Lindsay T, Hunt J. 2014. Paradise saved. Auckland: Random House.

- Butler D, Merton D. 1992. The black robin. Saving the world’s most endangered bird. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Clarke E, Russell J ( Converners). 2019. Predator Free New Zealand: social, cultural and ethical challenges. Bioheritage Challenge, New Zealand.

- Cosgrove R. 2018. Water pollution remains major concern for New Zealanders. https://fishandgame.org.nz/news/water-pollution-remains-major-concern-for-new-zealanders/.

- Cree A. 2014. Tuatara. Biology and conservation of a venerable survivor. Christchurch: Canterbury University Press.

- Daugherty CH, Towns DR. 2019. One ecosystem, one national park: a new vision for biodiversity conservation in New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(3):440–448. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1659834.

- Department of Conservation. 2019. Budget 2019 − DOC funding increase. http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/P01905/S00460/budget-2019-doc-funding-increase.htm.

- Edwards J. 2019, Jul 13. Pledge to make Stewart Island predator free. Otago Daily Times.

- Foote KJ, Joy MK, Death RG. 2015. New Zealand dairy farming: milking our environment for all its worth. Environmental Management. 56:709–720.

- Frankham J. 2016, Jan-Feb. Treasure Island, New Zealand Geographic.

- Fukami T, Wardle DA, Bellingham PJ, Mulder CPH, Towns DR, Yeates GW, Bonner KI, Durrett MS, Grant-Hoffman MN, Williamson WM. 2006. Above- and below-ground impacts of introduced predators in seabird-dominated island ecosystems. Ecology Letters. 9:1299–1307.

- Galbraith M. 2013. Public and ecology – the role of volunteers on Tiritiri Matangi Island. New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 37:266–271.

- Gregory R. 2008. Political responsibility for bureaucratic incompetence: tragedy at Cave Creek. In: Boin A, editor. Crisis management volume III. Los Angeles: Sage; p. 519–538.

- Hansford D. 2016. Protecting paradise 1080 and the fight to save New Zealand’s wildlife. Nelson: Potton & Burton.

- Hare KM, Borrelle SBB, Buckley HL, Collier KJ, Constantine R, Perrott JK, Watts CH, Towns DR. 2019. Intractable: species in New Zealand that continue to decline despite conservation efforts. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(3):301–319. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1599967.

- Hobson B. 2015, Dec 10. NZAS ends kakapo recovery sponsorship. 3News.

- Innes J, Fitzgerald N, Binny R, Byrom A, Pech R, Watts C, Gillies C, Maitland M, Campbell-Hunt C. 2019. New Zealand sanctuaries: origins, attributes and outcomes. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(3):370–393. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1620297.

- Jones H, Holmes N, Keitt B, Campbell K, Kappes P, Tershy B, Spatz D, Butchart SHM, Armstrong D, Seddon P, et al. 2016. Invasive mammal eradication on islands results in substantial conservation gains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113:4033–4038.

- Lyver PO’B, Ruru J, Tylianakis JM, Arnold J, Maliner S, Bataille C, Herse M, Jones C, Timoti P, Wilcox M, et al. 2019. Building biocultural approaches into Aotearoa-New Zealand's conservation future. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 49(3):394–411. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2018.1539405

- Murphy EC, Eason CT, Hix S, MacMorran D. 2007. Developing a new toxin for potential control of feral cats, stoats, and wild dogs in New Zealand. In: Witmer GW, Pitt WC, Fagerstone KA, editors. Managing invasive species: proceedings of an international symposium. Fort Collins: Aphis, Wildlife Services; p. 469–473.

- Nelson N, Briskie JV, Constantine R, Monks J, Wallis G, Watts C, Wotton D. 2019. The winners: species that have benefited from 30 years of conservation action. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(3):281–300. doi:10.1080/03036758.2018.1518249.

- Peltzer D, Bellingham PJ, Dickie IA, Hulme PE, Lyver PO’B, McGlone M, Richardson SJ, Wood J. 2019. Scale and complexity implications for Predator-Free New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(3):412–439. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1653940.

- Peters MA, Hamilton D, Eames C. 2015. Action on the ground: a review of community environmental groups’ restoration objectives, activities and partnerships in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 39:179–189.

- Powell A. 2008. The race to save the world’s rarest bird: the discovery and death of the po’ouli. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books.

- Priestley R. 2012, Apr 14. Sir Paul Callaghan’s crazy idea. Listener.

- Ruscoe WA, Ramsay DS, Pech RP, Sweetapple PJ, Yockney I, Barron MC, Perry M, Nugent G, Carran R, Warne R, et al. 2011. Unexpected consequences of control: competitive vs. predator release in a four-species assemblage of invasive mammals. Ecology Letters. 14:1035–1042.

- Simberloff D. 2002. Today Tiritiri Matangi, tomorrow the world! Are we aiming too low in invasives control? In: Veitch CR, Clout MN, editors. Turning the tide: the eradication of invasive species. Gland (Switzerland): IUCN; p. 4–12.

- Simberloff D. 2019. New Zealand as a leader in conservation practice and invasion management. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(3):259–280. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1652193.

- Taylor R. 1997. The state of New Zealand’s environment. The Ministry for the Environment. Wellington: GP Publications.

- Towns DR, Broome KG. 2003. From small Maria to massive Campbell: forty years of rat eradications from New Zealand islands. New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 30:377–398.

- Townsend AJ, DeLange PJ, Duffy CAJ, Miskelly CM, Molloy J, Norton DA. 2008. New Zealand threat classification system manual. Wellington: Department of Conservation.

- Wallace KJ, Clarkson BD. 2019. Urban forest restoration ecology: a review from Hamilton, New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(3):347–369. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1637352.

- Wallis G. 2019. Thirty years of conservation genetics in New Zealand: what have we learnt? Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(3):320–346. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1586735.

- Warne K, Svold M. 2019. The Whanganui River in New Zealand is a legal person. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2019/04/maori-river-in-new-zealand-is-a-legal-person.

- Williams D. 2018, Sept 13. DOC takes lesson from mining firm. Newsroom. https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2018/09/12/234731/doc-takes-lesson;from-mining.

- Wright J. 2011. Evaluating the use of 1080: predators, poisons and silent forests. Wellington: Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment.

- Wright J. 2013. Update report evaluating the use of 1080: predators, poisons and silent forests. Wellington: Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment.

- Young D. 2004. Our islands, our selves. Dunedin: University of Otago Press.