ABSTRACT

John Buchanan was New Zealand’s first locally-based official scientific illustrator, preparing illustrations for a wide range of scientific publications. He was also an experienced botanist, publishing papers on the local flora. From 1862 until his retirement in 1885 Buchanan worked as an assistant to James Hector, undertaking fieldwork and a variety of technical projects. From 1868 onwards he undertook the time-consuming task of preparing illustrations for the first eighteen volumes of the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute.

Introduction

John Buchanan () is remembered today in the scientific community mainly for his botanical contributions, and secondarily as an artist who recorded aspects of the nineteenth century Otago landscape (Adams Citation2002; Tyler Citation2013). But both of these are sidelines in the later part of Buchanan’s career as a scientific illustrator. From 1862 until his retirement in 1885 he was employed as a draftsman by James Hector, firstly for the Geological Survey of Otago for two and a half years, and then for the next 20 years by the Geological Survey and Colonial Museum in Wellington. He undertook a wide range of technical and illustrative work, but his time-consuming role in preparing illustrations for the first eighteen issues of the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute has been largely overlooked.

Buchanan’s background

Born in Scotland, John Buchanan was apprenticed as a pattern designer at a calico printworks in the Vale of Leven. From an early age he was interested in botany, spending much of his spare time collecting plants. He emigrated to New Zealand, arriving in Port Chalmers in February 1852 and later purchased a ten-acre section in North-East Valley, Dunedin. For the next decade, he prospected for gold and worked as a field assistant in reconnaissance surveys of Otago Province. He continued to collect plants, some of which he sent to Dr John Ross, a Scottish doctor and amateur botanist (Adams Citation2002).

James Hector arrived in Otago in 1862 to take up the position of Provincial Geologist. He corresponded regularly with Dr Joseph Hooker of Kew Gardens (Yaldwyn and Hobbs Citation1998; Burns and Nathan Citation2012a). At the time Hooker was working on a handbook of the New Zealand flora and was keen to obtain more plants from Otago. Hooker had heard of Buchanan as a local plant collector in Dunedin from Dr John Ross and suggested that Hector contact him. A few months after his arrival, Hector was able to employ Buchanan as his draftsman – there was no mention of botanical work in the proposals that Hector put to the Otago Provincial Council, which were concerned with the search for gold and other minerals – but there is no doubt that Hector wanted to use Buchanan’s botanical expertise. In September 1862, Hector was able to write with some satisfaction to Hooker telling him that he had employed Buchanan and that he had started collecting plants. He said that,

… Until December he will be working in the North-East Valley – close to Dunedin, which is one of the best and richest spots in the Province. After that I shall be going I hope to the West Coast & of course shall take him with lots of paper, so that I hope to have a fine harvest for you soon. (Burns and Nathan Citation2012a, p. 36)

Hector and Buchanan in Otago

Hector took Buchanan on a number of trips around Otago including his major expedition up the Matukituki valley to try and find a route to the West Coast. Buchanan explored the upper reaches of the Matukituki River, compiling what is probably the first vegetation map produced in New Zealand (Supplementary Figure 1). He also joined Hector on the later stage of his Fiordland trip in the Matilda Hayes, producing sketches of Milford Sound that were to become the basis of his famous watercolour (reproduced by Nathan Citation2015, p. 60). Hooker was well pleased with the Otago plants that Buchanan and Hector had collected, and delayed publication of his Handbook of the New Zealand Flora so that he could incorporate the results of the new collections.

While Buchanan worked for Hector in Otago, from 1862 to 1865, he did a variety of work – drawing maps and illustrations, planning and taking part in fieldwork, and preparing displays and labels for the 1865 Dunedin Exhibition. His magnum opus was undoubtedly the giant geological map of Otago, pulling together Hector’s surveys (Nathan Citation2011). Buchanan’s knowledge of Otago botany was recognised when Hector invited him to write an essay for the 1865 exhibition, which was later published in the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute (Buchanan Citation1868a). But although Buchanan’s botanical expertise was acknowledged by his election as a Fellow of the Linnean Society (for which he was sponsored by both Hector and Hooker), it is noteworthy that he always retained the status of Hector’s collector – all correspondence was between Hector and Hooker, and Buchanan’s plant lists, background information and scientific papers were appended to Hector’s letters. Although his botanical contribution was substantial, he was treated as a paid servant rather than an independent collector like William Colenso (Nathan Citation2017).

Buchanan was well-organised and clearly regarded as the practical man in the office, probably reflecting both his maturity and outdoors experience. Buchanan regularly made the arrangements for major expeditions and fieldwork, including hiring the horses, but he also took on all sorts of other technical tasks ranging from arranging for beached whales to be buried to assembling collections of native woods which were in demand for overseas exhibitions and museums.

Buchanan in Wellington

In 1865, Hector was appointed to set up a Geological Survey of New Zealand, based on Wellington which became the capital that year. He took several of his Otago staff with him, and three of these were to work for him for many years: Richard Gore, Henry Skey and John Buchanan. It was also the beginning of a long association with Walter Mantell, a politician interested in natural science ().

Figure 2. Group photographed in the garden of Walter Mantell (near the present Parliament Buildings, Wellington) in 1865 or 1866. From left: Charles Knight (auditor-general and amateur botanist), John Buchanan, infant Wally Mantell, James Hector, and Walter Mantell (seated on grass). Although Buchanan had working class origins, the photograph illustrates that he mixed with leading figures in the small Wellington scientific community. Toitu Settlers Museum, Dunedin (Buchanan Album).

Hector was very keen to have a Museum to display geological and other natural history specimens. This also included offices for the geological staff and was rapidly constructed so that they were able to move in by the end of 1865. Soon afterwards, Hector helped set up the New Zealand Institute, the forerunner of the Royal Society of New Zealand (Fleming Citation1987; Nathan Citation2015). From the viewpoint of an historian, there is some doubt about exactly what organisation Hector and his staff technically worked for – was it the Geological Survey, the Colonial Museum or the New Zealand Institute? Hector was not consistent, and used whatever name suited him at the time. But the reality is, at least in terms of Parliamentary estimates, that Buchanan spent his whole career working for what was officially called the Geological Department (later the Geological & Meteorological Department), part of the Colonial Secretary’s Office.

In 1866 Buchanan’s annual salary was ₤300, and it stayed the same until 1881 when it rose to ₤325. This compares with Hector’s salary of ₤800, which remained the same 38 years. Although this may sound miserly in 2019, it is often overlooked that there was long-term deflation in the late nineteenth century. In terms of today’s purchasing power, Buchanan was getting the equivalent of $31,000 in 1866, and by 1881 it had risen to $51,200 (estimated using the inflation calculator on the Reserve Bank website, www.rbnz.govt.nz).

When he moved to Wellington it seemed that Buchanan’s work for the national Geological Survey might be as varied as it was in Otago. During the summer of 1865–1866, Hector went on a lengthy trip to Northland to investigate coal resources, and Buchanan accompanied him as field assistant and botanical collector. Buchanan did not enjoy himself on this trip, and we have a candid account of his impressions from several letters he wrote to Richard Gore. Having been brought up in Scotland and acclimatised to Dunedin, he found Northland far too hot, and the local Māori insolent. The botany too was a great disappointment – Colenso had investigated the region twenty years earlier, and there were few new plants to be found (Burns and Nathan Citation2013, p. 26–27 & 31–33). But Hector found the geology fascinating, and the outcome of the trip was a large, coloured geological map of Northland, drafted by Buchanan (Supplementary Figure 2).

Hector was keen to continue sending interesting plants to Hooker at Kew – there was clearly rivalry with Haast, who had made large collections containing new species from the Canterbury mountains (Nolden et al. Citation2013). But there were few places left that had not been botanised by Colenso, who had covered much of North Island, or the provinces of Canterbury and Otago that were relatively well-explored. Hector was committed to investigating the newly discovered West Coast goldfields during the 1866–1867 summer, but he arranged to send Buchanan to look at two of the gaps in the botanical map of New Zealand – the Kaikoura mountains, the last large area of unknown territory in the South Island (Buchanan Citation1868b), followed by a trip to Mt Taranaki which had not visited by Colenso. Buchanan was ostensibly undertaking reconnaissance geological fieldwork, with botany as a sideline, but the way his fieldwork was organised was clearly part of a race to find new plants to impress Joseph Hooker.

Illustrating the transactions and other publications

From 1868 onwards, there was a major change in Buchanan’s routine, and this is when he became a full-time draftsman and illustrator. As Hector consolidated his position as the head of New Zealand’s first scientific organisation, he was keen to start publishing the results of research, and started two major series of annual publications: the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute and the Reports of Geological Exploration (or RGEs).

The Transactions contained papers on a wide range of scientific topics that were submitted through the different branches of the New Zealand Institute, whereas the RGEs were more narrowly focussed on the work of the Geological Survey. Both publications contained illustrations, and these were largely handed over to Buchanan.

Buchanan was now responsible for preparing many tens of diagrams every year – most years between 60 and 100. He was working to tight deadlines all the time. Hector’s publications were printed by the Government Printer at quiet times when parliament was not in session. But a constant problem was the lack of type held by the printing office. So sections of the Transactions were set up, rapidly checked, printed off, and the type was pulled to pieces ready for the next section. The diagrams had to be ready to be inserted in the text when it was being prepared. An examination of the annual volumes of the Transactions shows that they invariably have large lists of Corrigenda inserted at the front because printing was undertaken under high pressure, and there was no time for authors to check proofs.

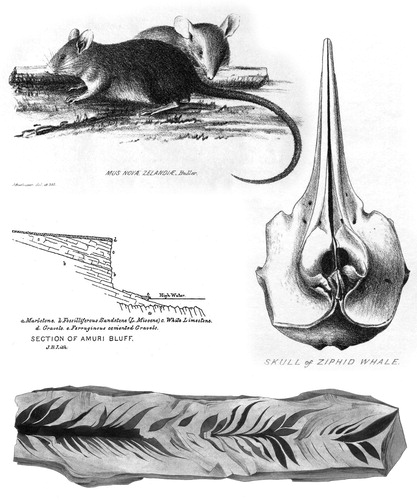

Often Buchanan was simply presented with an object that needed to be illustrated, and had to start by drawing it. includes a small selection of his drawings to show the variety of work he undertook. We know that he used a camera lucida, and also sometimes worked from photographs. When Hector was in England in 1875, he obtained a new instrument (that he called a spectrograph) for Buchanan to use in place of the camera lucida, but unfortunately we have no idea of how effective it was or what Buchanan thought of it. Some of the diagrams that Buchanan produced are labelled ‘J. Buchanan del’ (i.e. drawn by J. Buchanan), and we can be sure that he created the original drawings. Some of the contributors to the Transactions, especially Hutton, Buller and Potts submitted their own drawings, and Buchanan was left with the responsibility of converting them into a form that could be printed, either as a lithograph or a woodcut. We don’t always know exactly which diagrams Buchanan drew himself, but everything certainly passed through his hands, and he can take credit for the consistently high standard of the illustrations in the first 18 volumes of the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute. Hector was well aware of the quality of Buchanan’s work, and wrote to Mantell from London in 1875: ‘ … Buchanan’s drawings are much admired, and the palaeontologists especially like his rendering of the Fossils which they say is almost superior to anything they get in London’ (Burns and Nathan Citation2012b, p. 18).

Figure 3. Examples of the illustrations that Buchanan drew for publication, mainly in the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute. Top: Native kiore, identified by W. Buller. Transactions vol III plate 3. Middle left: Section at Amuri Bluff recorded by Buchanan. Report of Geological Explorations 4, between p. 37 and 38. Middle right: Whale skull. Transactions vol III plate XV. Bottom: Unpublished drawing of fossil leaves that Hector named Auricurites buchanani. GNS Science, Lower Hutt.

Geological maps and fossils

In addition to the never-ending task of preparing diagrams for the Transactions and RGEs, Hector usually had one or more long-term projects underway that required input from Buchanan. He was keen to emulate the British and European geological surveys by publishing coloured geological maps, but this was expensive and he usually was not able to obtain the money. Hector was determined, however, to produce the first geological map of the whole of New Zealand – a strong advertisement for his Geological Survey – and Buchanan worked on this in 1867 and 1868, whenever he had any spare time. The cartography was entirely done by Buchanan, and it is an impressive map showing that detailed information was available over the whole country (Nathan Citation2014, ; a high-resolution copy can be downloaded from the online version of that paper). Hector was to produce two updated versions over the next 15 years as more information came to hand, but there is little change except in the fine detail, to Buchanan’s 1869 edition.

Hector was also keen to see New Zealand’s distinctive fossils described, and planned a series of monographs, of which he was to be the author of several. Unfortunately his ambition to do things was often stronger than his ability to see them through to completion, and in fact, none of his planned monographs was completed. This must have been a source of frustration to Buchanan, who undertook a large number of drawings. Hector lavished a lot of care on a planned monograph on fossil plants, which was intended to be co-authored with Hooker. Although Buchanan completed the drawings (example at the bottom of ), many of which were actually printed, the monograph never appeared – which has been the cause of ongoing problems to later generations of scientists who have worked on fossil plants (Mildenhall Citation1970).

Handbook of New Zealand grasses and other botanical work

Hector complained a number of times that, as a public servant, he had to carry out the whims of politicians. Sir George Grey, premier in the 1870s, felt that research should be done on New Zealand’s native grasses which had been largely neglected by botanists, and managed to get a sum placed on the estimates in 1876 to publish a monograph on native grasses. Hector was unenthusiastic, but it was a block of money he could not turn down, so the task was handed over to Buchanan (Tyler Citation2016). It was, in fact, one of the few times that Buchanan was officially paid to undertake botanical work, and to prepare a monograph on his own. It was completed efficiently, and published in two formats – a large monograph, fully illustrating the grasses (Buchanan Citation1880a), and a smaller handbook that was intended to be more generally available to the public (Buchanan Citation1880b).

From 1868 onwards, when Buchanan started working full-time as a draftsman and illustrator, he got little official time for botanical fieldwork – almost everything he did was in weekends or during his annual holiday. In 1880, the House of Representatives voted £150 for a botanical survey of the Tararua Range, which he undertook – in addition, of course, to his normal cartographic duties. In December 1880 to January 1881 Buchanan accompanied Alexander McKay and James Park on a trip to the mountains of west Otago (Bishop Citation2008, p. 138–141), visiting areas he had seen two decades earlier in order to collect additional specimens requested by Hooker (Buchanan Citation1881).

Some personal notes

As part of a biographical study of James Hector (Nathan Citation2015), I have been involved in transcribing letters written by Hector and some of his contemporaries in the nineteenth century scientific community. One of the things that is obvious in searching through the letters for references to John Buchanan is that comments about him are almost invariably positive, and often affectionate. He is sometimes called ‘Buch’ or ‘Bucky’, and it seems as if he was one of those people who was respected and liked by everyone who worked with him. From time to time he was also called ‘Old Bucky’, and this is a reminder that he was the old man in the office. He was 15 years older than Hector – when he started in 1862 Hector was 28, and Buchanan was 43. In an 1876 letter to Hooker, Hector wrote ‘ … I enclose some interesting papers by Buchanan. That on the Marattia I should think worthy of the Linnaean, & it would please the old man if you communicated it for him’ (Burns and Nathan Citation2012a, p. 177–178). To younger staff such as Alexander McKay and James Park, Buchanan must have seemed like a father-figure.

In 1875–1876 Hector was overseas, leaving Walter Mantell in charge. Mantell wrote Hector a series of gossipy letters (Burns and Nathan Citation2012b), and most people in the office except Buchanan come in for some criticism. But Mantell simply comments on how hard Buchanan is working – and he also refers to the Botanic Gardens, which Buchanan inspected every day, as the ‘Buchanical’ gardens. The comment about how hard Buchanan worked – often until late at night – is a recurrent one from different people. As a bachelor, who lived as a boarder in a private house in Wellington, it seems as if he spent every waking hour during the week at the Museum, and that much of his botanical illustration and writing was done in the evenings, with weekends used for field excursions.

In 1885 Hector wrote to Hooker to say, ‘ … I am afraid that poor old Buchanan is failing fast, but he will insist on working away as hard as ever & I believe will drop in his collar’. Later that year he told Hooker, ‘ … Poor B has retired on a pension so we have lost a valuable help’ (Burns and Nathan Citation2012a, p. 203–204).

Conclusion

In John Buchanan, we celebrate New Zealand’s first professional scientific illustrator, who set high standards for those who followed him. The success of the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute, the parent of later scientific journals in New Zealand, owes much to Buchanan’s work both as illustrator and lithographer.

Supplemental material 2

Download JPEG Image (2.8 MB)Supplemental material 1

Download JPEG Image (7.4 MB)Acknowledgements

This paper was originally presented at a conference, ‘A celebration of John Buchanan FLS: New Zealand artist, botanist and explorer’ held in Dunedin on November 2012. I am grateful to Linda Tyler and the late David Galloway for their helpful comments on the manuscript, and to Philip Carthew (formerly GNS Science) for assistance with the illustrations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Adams NM. 2002. John Buchanan FLS: botanist and artist (1819–1898). Tuhinga. 13:71–115.

- Bishop DG. 2008. The real McKay: the remarkable life of Alexander McKay, geologist. Dunedin: Otago University Press; 252 p.

- Buchanan J. 1868a. Sketch of the botany of Otago. Transactions of the New Zealand Institute. 1:22–37.

- Buchanan J. 1868b. Kaikoura District. Report on the Progress of the Geological Survey of New Zealand During 1866–7. 34–41.

- Buchanan J. 1880a. The indigenous grasses of New Zealand. Wellington: Government Printer. [Issued in three fascicles, 1878, 1879, 1880]; 192 p.

- Buchanan J. 1880b. Manual of indigenous grasses of New Zealand. Wellington: Government Printer; 175 p.

- Buchanan J. 1881. On the alpine flora of New Zealand. Transactions of the New Zealand Institute. 14:342–356.

- Burns R, Nathan S. 2012a. My Dear Hooker: transcriptions of letters from James Hector to Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1860 and 1898. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133B; 207 p.

- Burns R, Nathan S. 2012b. A Quick Run Home: Correspondence while James Hector was overseas in 1875–1876. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133E; 142 p.

- Burns R, Nathan S. 2013. James Hector in Northland, 1865–1866. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133G; 57 p.

- Fleming CA. 1987. Science, settlers and scholars: the centennial history of the royal society of New Zealand. Wellington: Royal Society of New Zealand; 353 p.

- Mildenhall DC. 1970. Checklist of valid and invalid plant macrofossils from New Zealand. Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand (Earth Sciences). 8(6):77–89.

- Nathan S. 2011. James Hector and the Geological Map of Otago. Web feature, Hocken Collections, University of Otago. http://www.otago.ac.nz/library/treasures/hector/.

- Nathan S. 2014. James Hector and the first geological maps of New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 44(2):88–100. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2013.877495

- Nathan S. 2015. James Hector: explorer, scientist, leader. Wellington: Geoscience Society of New Zealand; 264 p.

- Nathan S. 2017. The scientific achievements of William Colenso. eColenso. 8(5):14–21.

- Nolden S, Nathan S, Mildenhall E. 2013. The correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861–1886. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H; 219 p.

- Tyler L. 2013. Art, science and photography: New Zealand illustrator John Buchanan. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art. 13(1):90–103. doi: 10.1080/14434318.2013.11432644

- Tyler L. 2016. Illustrating the grasses and the transactions: John Buchanan’s development of technologies for lithography in natural history. ENNZ: Environment and Nature in New Zealand. 10(1). http://www.environmentalhistory-au-nz.org.

- Yaldwyn J, Hobbs J. 1998. My Dear Hector: letters from Joseph Dalton Hooker to James Hector, 1862–1893. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Technical Report 31; 292 p.