ABSTRACT

This narrative review summarises the latest evidence on the causes and consequences of substance use in adolescence and describes long-term trends in adolescent alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use in Aotearoa. Adolescence is a time of rapid brain development when young people are uniquely vulnerable to the risks of substance use. It is a major cause of health and social harm in this age group and can affect adult outcomes and the health of the next generation. Therefore, substance use trends are central to understanding the current and future state of child and youth wellbeing in Aotearoa. Adolescent use of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis peaked in the late 1990s/early 2000s, then declined rapidly, and prevalence is now much lower than 20 years ago. However, levels of adolescent binge drinking remain high by international standards and disparities in tobacco and cannabis use by ethnicity and socioeconomic status are wide. Evidence suggests we may again be at a turning point, with-long term declines stalling or reversing in the past 2–5 years, and vaping emerging as a new risk. Greater investment in primary prevention is indicated, including restrictions on alcohol marketing and availability, and alleviation of poverty, racism and marginalisation.

Introduction

Substance use is a major cause of health and social harm in adolescents (13-19 years) and is linked to the two leading causes of death in this age group: road crashes and suicide (Ministry of Health Citation2021b). As well as having immediate risks, substance use at an early age is a predictor of long-term health and social problems including addiction issues, mental health problems and financial problems in adulthood (Cerda et al. Citation2016; Hall et al. Citation2016). Adolescence is a time of rapid brain development when young people are uniquely vulnerable to the risks of substance use (Hall et al. Citation2016; Romer et al. Citation2017). Therefore, substance use trends are highly salient to the current and future state of child and youth wellbeing in Aotearoa.

In this narrative review we summarise evidence about the causes and consequences of adolescent substance use from a public health perspective. We explore long-term trends in adolescent tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use in Aotearoa, and emerging issues such as vaping. We discuss evidence about the drivers and impacts of population-level trends. Finally, we discuss policy implications and comment on the urgent need for improved monitoring of substance use and associated harm in young people, and increased investment in prevention.

Causes and consequences of substance use

Reasons for substance use

Adolescents engage in substance use for many reasons, and it is important to recognise that, from a young person’s perspective, substance use can offer benefits and rewards as well as risks (Bonino et al. Citation2005). Some teens are naturally curious about psychoactive substances, and experimentation can be part of bonding with friends, asserting independence from parents, and exploring the world. Substance use may also be seen by young people as ‘adult-like’, and therefore have symbolic significance as a rite of passage. The physiological effects of substance use (e.g. intoxication with alcohol or cannabis, or the nicotine hit associated with smoking and vaping) are often experienced as pleasurable (Arnull and Ryder Citation2019), and – coupled with the psycho-social rewards discussed above – mean substance use can be self-reinforcing.

Substance-related harm

Although many adolescents experiment with substances such as alcohol, nicotine and cannabis recreationally without overt negative effects, evidence about substance-related harm is compelling. Tobacco is highly addictive and estimated to kill at least half of long-term users (Schane et al. Citation2010; Ministry of Health Citation2021a). Most young people do not intend to become long-term smokers, but many underestimate the addictiveness of nicotine (Gray et al. Citation2016). Similarly, those who experiment with nicotine vaping may unwittingly find themselves addicted to a behaviour which – although less harmful than smoking – is nonetheless health damaging (St Helen and Eaton Citation2018; Wilson et al. Citation2021). Alcohol is a carcinogen with no safe lower limit to avoid increased risk of breast, colorectal and other cancers (Scoccianti et al. Citation2016). For adolescents, acute risks of alcohol intoxication (e.g. associated violence, sexual assault, injury, and road crashes) are of public health concern, as well as the development of drinking habits that may cause long-term harm (Connor et al. Citation2009; Taylor et al. Citation2010). Cannabis intoxication is also associated with increased risk of road crashes and injury, as well as drug-induced psychosis and other acute and long-term health and social problems (Volkow et al. Citation2014). Cannabis possession remains illegal in New Zealand and contact with the justice system has been a major source of cannabis-related harm, particularly for young Māori (Fergusson et al. Citation2003; Theodore et al. Citation2020). Evidence indicates that the negative impacts of substance use are more pronounced when substance use begins at a young age (e.g. under 16 years) and when multiple substances are used (Moss et al. Citation2014; Volkow et al. Citation2014).

Links between substance use and suicide

Because New Zealand has the highest rate of teenage suicide in the OECD (OECD Citation2017), the links between substance use and suicidal behaviour deserve specific attention. Heavy substance use and suicidal behaviour are both ‘externalising’ behaviours (i.e. they can be ways of expressing distress) with similar underlying risk factors, so it is unsurprising they are associated (Esposito-Smythers and Spirito Citation2004). However, there is growing evidence of a causal relationship, with the case strongest for alcohol. Alcohol can influence several pathways in the biopsychosocial model for suicide risk (Turecki et al. Citation2019). For example, alcohol use can contribute to the development and maintenance of depression (Fergusson et al. Citation2009), which may then increase suicide risk (McManama O'Brien et al. Citation2014). Acute alcohol use acts as a risk factor for suicide through: 1) increasing disinhibition, impulsivity and aggression (Heinz et al. Citation2011; Bagge et al. Citation2015), 2) impairing the ability to identify other coping strategies (Giancola et al. Citation2010), 3) an association with more lethal suicide means (Sher et al. Citation2009), and (4) potentiating the effects of other drugs in relation to self-poisoning (Hawton et al. Citation1989). There is limited evidence for individual-level alcohol interventions being effective in reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Witt et al. Citation2021), but a recent systematic review found evidence that population-level alcohol interventions (e.g. enforcement of a minimum drinking age, drink-driving countermeasures) can be effective at reducing youth suicide rates (Kolves et al. Citation2020). The evidence for a causal relationship between cannabis use and suicide is less well developed, but recent studies suggest causal pathways via depression and disinhibition are plausible (Orri et al. Citation2020; Han et al. Citation2021). Research also indicates tobacco may be a causal factor in suicidal behaviour, although the causal mechanism is unclear. Prospective twin studies have found a dose–response relationship between tobacco use and suicidal behaviour (Evins et al. Citation2017; Korhonen et al. Citation2018) and a US study found counties that increased tobacco taxes or strengthened smoke-free air laws decreased their suicide rates relative to control counties (Grucza et al. Citation2014).

Risk factors for substance use

Risk of substance-related harm is greater in young people who use substances in response to previous or current adverse life experiences, as the dosage and frequency of use tend to be higher in this group (Patrick et al. Citation2019; Heim et al. Citation2021). There is evidence that acute and chronic stress have physiological effects that increase the reinforcing effects of drugs (Moustafa et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, trauma or stress in early life can cause permanent neurological changes that make people more vulnerable to problematic substance use (Moustafa et al. Citation2018). A 2012 study found that about 11% of secondary school students in Aotearoa (about 10% of girls and 13% of boys) reported levels of substance use that put them at significant risk of harm (Fleming et al. Citation2014). Secondary school students who reported they did not feel close to at least one parent or had experience of sexual abuse or family violence were much more likely to report problematic levels of substance use than those without these risk factors. Based on the same dataset, another study found experience of ethnic discrimination was associated with smoking in secondary students (Crengle et al. Citation2012). Substance use patterns in adolescence predict substance use behaviour in early adulthood, when many will become parents themselves. Problematic substance use can have intergenerational consequences, since in-utero exposure and parenting affected by substance use may have lifelong physical and psychological consequences for the next generation (Irner Citation2012; Mund et al. Citation2013; Kepple Citation2018).

Young people may turn to substance use as a coping mechanism but unfortunately it tends to compound psycho-social and mental health problems, rather than alleviating them. The physiological effects of alcohol can cause or exacerbate depression (Fergusson et al. Citation2009), while nicotine and other stimulants can lead to anxiety and mood disorders (Laviolette Citation2021). The behavioural aspects of substance use can result in relationship difficulties, disciplinary issues at school, and contact with the justice system (Slade et al. Citation2008; Bax Citation2021). There are also bi-directional associations between substance use and sleep disturbance in young people, with inadequate sleep impacting on health and functioning (Pasch et al. Citation2012; Shochat et al. Citation2014). Young people can find themselves in a vicious circle of life difficulties leading to heavy substance use, which in turn leads to further life difficulties and mental health issues.

Demographic differences in substance use

Because of greater exposure to risk factors (including structural determinants like poverty and racism), some demographic groups are more likely to engage in early substance use than others and are therefore at greater risk of harm. For example, prevalence of substance use tends to be higher among adolescents living in high-deprivation neighbourhoods, rangatahi Māori and sexual and gender minority youth (Fleming, Ball, et al. Citation2020, Fenaughty et al., forthcoming). Minority stress theory (Mereish Citation2019) and the intergenerational trauma associated with colonisation (Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor Citation2019) help to explain elevated substance use in structurally disadvantaged groups. Environmental determinants such as exposure to alcohol marketing and greater concentration of alcohol and tobacco retailers in deprived neighbourhoods also help to explain disparities. For example, research undertaken in Aotearoa using wearable cameras found children were exposed to alcohol marketing 4.5 times per day on average, e.g. via shop front signage, merchandise and sports sponsorship. Exposure rates for Māori children were over five times that of NZ European children (Chambers et al. Citation2018). Although their likelihood of substance use may be higher than other groups, it is important to note that the majority of Māori, rainbow, and low socioeconomic status adolescents in Aotearoa do not smoke, binge drink or take other drugs. Nor is substance use exclusive to these groups.

Substance use trends

Repeat cross-sectional surveys enable us to observe changes in prevalence of adolescent substance over time. To analyse trends, we collated data from all New Zealand repeat cross-sectional surveys that included questions on substance use in adolescents. Surveys that did not have publicly available and comparable data for at least three survey iterations were excluded. Data sources are detailed in .

Table 1. New Zealand data sources on adolescent substance use.

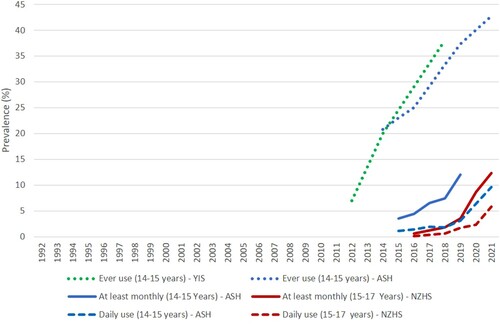

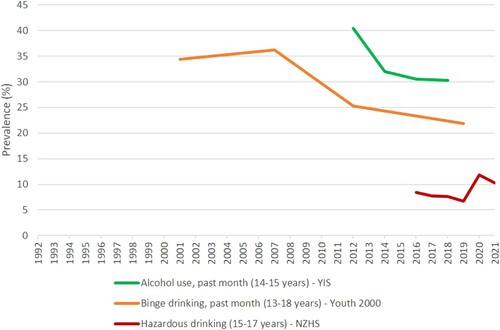

Alcohol

Alcohol is the most commonly used substance by adolescents. Long-term data series are lacking, but research suggests adolescent alcohol use increased in the late 1990s, peaked in the early 2000s (Kalafatelis et al. Citation2003; Huckle et al. Citation2011, Citation2012) and subsequently declined substantially (Jackson et al. Citation2017; Gurram and Brown Citation2020). Between 2007 and 2012 an increasing proportion of secondary school students abstained from drinking, and drinkers drank less frequently (Jackson et al. Citation2017). YIS findings suggest the decline in prevalence and/or frequency of drinking continued from 2012 to 2016 at least among younger students, with past month drinking prevalence falling from 40% to 30% among 14–15-year-olds (). The Youth 2000 series shows the prevalence of past month binge drinking (five or more drinks in a session) in secondary students declined from 36% to 22% between 2001 and 2019 () but remains high compared to similar countries. Although directly comparable measures are unavailable, less than 10% of US students aged 13–18 years and 7% of English students aged 11–15 years reported getting drunk in the previous month, and only 5% of Australian students aged 12–17 years reported having five or more drinks in one session in the past week (Guerin and White Citation2020; Johnston et al. Citation2020; NHS Digital Citation2021).

Figure 1. Prevalence of adolescent alcohol use, Aotearoa, 1992-2021. Binge drinking = 5 + drinks in a session. Hazardous drinking = AUDIT score of 8 or above.

Since 2019 there has been an increase in hazardous drinking (i.e. drinking patterns associated with acute and long-term risk) among 15–17-year-olds according to the NZHS (). Although this finding should be treated with caution due the small sample size for this age band, it suggests the long-term decline in adolescent drinking may be over.

Adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking is common across the socioeconomic spectrum, and in both males and females (Gurram and Brown Citation2020). For example, the Youth19 survey found that among secondary school students in 2019, the prevalence of past month binge drinking was 22% overall and did not differ significantly between low, medium and high decile schools, or by gender (Fleming, Ball, et al. Citation2020). However, binge drinking was patterned by ethnicity with Māori and European students having the highest prevalence (28% and 24%, respectively), followed by Pacific (13%) and Asian (8%) students.

Over the past two decades, adolescent substance use trends have been distinct from adult trends. For example, between 2011/12 and 2015/16 the proportion of adults considered to be hazardous drinkers increased considerably, while decreasing among adolescents (Ministry of Health Citation2016).

Tobacco

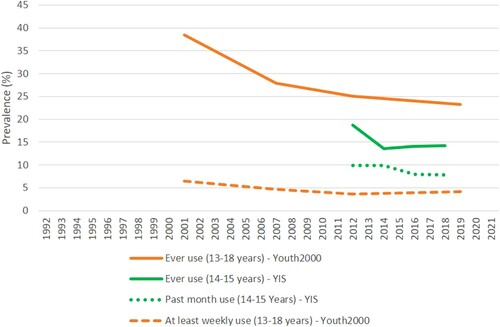

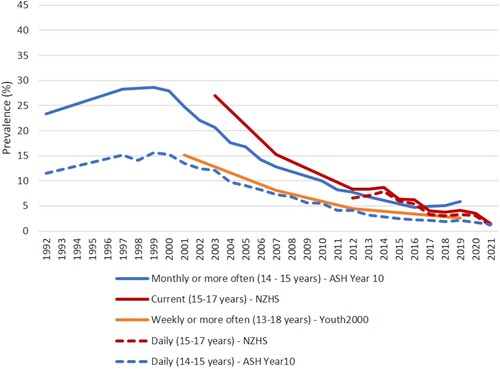

Whereas adult smoking rates have slowly but steadily declined since the 1960s, the prevalence of regular (at least monthly) smoking in Year 10 students (14-15 years) rose in the 1990s, peaking at 29% in 1999 before declining rapidly in the 2000s to a low of 4.7% in 2016 (). Between 2016 and 2019 regular smoking rose slightly to 5.9%. Daily smoking in this age group also rose in the 1990s, rapidly declined in the 2000s and was stable at 2% for the 2016–2019 period before reaching an all-time low of 1.3% in 2021(). The most recent NZHS findings suggest that, for 15–17-year-olds, a daily smoking plateau from 2016/17 to–2019/20 was followed by a substantial decline from 3% to 1% between 2019/20 and 2020/21. Smoking is strongly patterned by deprivation and ethnicity. For example, the Youth19 survey found students in Decile 1–3 secondary schools (high deprivation) were four times more likely to smoke at least weekly (5.2%) than students in Decile 8–10 schools (1.3%) (Fleming, Ball, et al. Citation2020). The same survey found weekly smoking was highest in Māori (4.6%), followed by Pacific (4.3%), European (2.1%) and Asian (0.9%) secondary students. Although absolute differences by ethnicity and deprivation narrowed in the 2000s (ASH (NZ) Citation2014, Citation2018), the increase in regular smoking observed in the ASH survey between 2016 and 2019 was concentrated in Māori and students from low decile schools. In these groups, prevalence of regular smoking increased from 11% to 14%, and from 9% to 12% respectively.

Figure 2. Prevalence of adolescent tobacco smoking, Aotearoa, 1992-2021. Current = has smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime and currently smokes at least once a month.

Adolescent tobacco use is similar in male and female secondary school students overall (Fleming, Ball, et al. Citation2020). However, regular smoking is slightly more common in Year 10 girls than boys (ASH (NZ) Citation2020; Gurram and Brown Citation2020) suggesting girls may initiate smoking at a younger age than boys.

E-cigarettes

Vaping has emerged as a new issue in the past decade, with data sources all showing a rapid increase in adolescent e-cigarette use (). The majority of e-cigarette use among adolescents is experimental, with ever use high compared to regular use (). However, prevalence of at least monthly use increased from 3.5% (2015) to 12% (2019) in Year 10 students, and from less than 1% (2015/16) to 12% (2020/21) in the NZHS community sample of 15–17-year-olds (). Similarly, between 2015 and 2021 daily e-cigarette use increased from 1% to 10% among Year 10 students, and from less than 1% to 6% in the NZHS 15–17 years age group.

The relationship between vaping and smoking is complex and contested. On one hand the prevalence of vaping, in relative terms, is much higher among adolescents who have tried smoking or who are current smokers (Lucas et al. Citation2020; Walker et al. Citation2020; Ball, Fleming et al. Citation2021). However, because most adolescents are never smokers a substantial proportion of adolescents who vape are never smokers – around two-thirds of those who have ever vaped, half of those who vape monthly or more often, and about a third of weekly vapers, according to the Youth19 survey (Ball, Fleming et al. Citation2021). Youth19 data indicate that over 80% of secondary school students who had tried e-cigarettes were non-smokers when they vaped for the first time (Ball, Fleming et al. Citation2021). The most recent iteration of the NZHS suggests both a leap in vaping and a sharp decline in smoking between 2019/20 and 2020/21 among 15–17-year-olds ( and ). However, surveys consistently show that vaping has increased to a greater extent than smoking has decreased. Thus, while some evidence suggests e-cigarettes are attracting youth who would otherwise be smoke free into nicotine use, the most recent NZHS data provide the first local evidence that vaping may be displacing smoking in older adolescents.

Unlike smoking, which is concentrated in high-deprivation neighbourhoods, regular e-cigarette use is more evenly spread across the socio-economic spectrum. In fact, the Youth19 study found vaping weekly or more often with nicotine was significantly more prevalent in NZ Dep 1-2 (affluent) areas (7%) compared with NZ Dep 9–10 areas (deprived) (3%). The same study found ethnic patterning of e-cigarette use was similar to alcohol, with Māori and European students having the highest prevalence, followed by Pacific and then Asian students (Ball, Fleming et al. Citation2021). However, Year 10 studies have found vaping to be more prevalent in Māori and Pacific students than European (Gurram et al. Citation2019; Walker et al. Citation2020). This apparent discrepancy (in studies with otherwise consistent findings) could be explained by Maori and Pacific students taking up vaping at a younger age than European students. The surveys consistently show that e-cigarette use is more common in boys than girls.

Cannabis

Data on adolescent cannabis use is scare, but evidence suggests declining use from 2000 with a plateau in use since around 2012/2014 (). For example, YIS data show a decline in prevalence of ever use from 19% (2012) to 14% (2014–2018), and in past month use from 10% (2012 and 2014) to 8% (2016 and 2018) among 14-15 year olds (Ball et al. Citation2020). In secondary school students (13–18 years), at least weekly cannabis use declined from 6.5% in 2001 to about 4% in 2012, with no significant change between 2012 and 2019 (Fleming, Ball, et al. Citation2020).

Cannabis use is now more prevalent than tobacco use in secondary school students, due to the dramatic decline in tobacco use. For example, the Youth19 study found use of cannabis weekly or more often was 4.1% in secondary students compared with 2.6% for tobacco smoking (Fleming, Ball et al. Citation2020). Demographic patterning of cannabis use is like that of tobacco, with prevalence notably higher in Māori and in students living in high-deprivation neighbourhoods. Declines between 2001 and 2012 were greatest in these groups, resulting in narrowing of ethnic and socio-economic disparities (Ball et al. Citation2019), but Youth19 findings show that the proportion of adolescents who use cannabis weekly or more often is still greater in high (5.4%) compared to low (3.3%) deprivation neighbourhoods, and greater in Māori (8.4%) than Pacific (3.6%), European (3.3%) or Asian (1.1%) students (Fleming, Ball, et al. Citation2020)

Cannabis vaping has emerged as a new mode of use, with vaporisers available that allow users to vape dried herb rather than smoking it. Anecdotal evidence suggests that black market producers are also creating and selling e-liquids containing THC (the active ingredient in cannabis) in Aotearoa. In fact, a local website provides a step-by-step guide to making cannabis e-liquid at home (Vapemate Citation2021). The emergence of black market and homemade e-liquids in Aotearoa is concerning given the 2019 US outbreak of acute lung injury that killed 68 people and hospitalised thousands (mostly young men), which was traced to black market THC e-liquids containing Vitamin E acetate (Muthumalage et al. Citation2020; Werner et al. Citation2020). Cannabis vaping is under-researched in Aotearoa. The only study we are aware of used 2016–2018 YIS data and found that among Year 10 students, about a quarter of those who had used cannabis in the past month had vaped cannabis in that time (Ball, Zhang et al. Citation2021).

Adolescent cannabis trends are distinct from adult trends. Among adults, past year cannabis use (excluding medicinal use) almost doubled from 8.1% in 2011/12 to 15.5% in 2018/19, with no significant change between 2018/19 and 2020/21 (Ministry of Health Citation2021c).

Other substances

Adolescent use of other substances such as methamphetamine (‘P’), solvents, ecstasy and cocaine is not well researched in Aotearoa, but data from the Youth2000 series suggests use of such substances is uncommon in secondary students. For example, in 2019 less than 4% of secondary school students reported ever using other substances. Research indicates that, as seen with smoking, cannabis and alcohol use, prevalence of other substance use declined in the 2001–2012 period (Ball et al. Citation2019). However, trends for the 2012–2019 period, trends for specific drugs, and trends in demographic sub-groups have not been explored.

Substance use trends: Summary of key points

Adolescent drinking and smoking increased in the 1990s.

Subsequently, there has been a substantial decline in drinking, smoking and cannabis use over the past two decades.

However, vaping has emerged as a new issue, and there is evidence that declines in smoking, drinking and cannabis use may have come to an end.

Recent increases in regular smoking and hazardous drinking among adolescents are concerning.

Despite declines, levels of adolescent binge drinking remain high in Aotearoa compared with similar countries.

Declines in adolescent drinking, smoking and cannabis use have occurred in all genders, ethnicities and socioeconomic strata, and ethnic differences have narrowed in absolute terms.

However, the persistent ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in adolescent substance use are likely to contribute to health inequities across the life course.

It is concerning to see widening disparities in regular smoking in Year 10 students between 2016 and 2019, following a decade in which the gaps had been narrowing in absolute terms.

Discussion

What caused the major decrease in adolescent substance use since 2000?

The major changes in drinking, smoking, and cannabis use observed over the past 20 years are not unique to Aotearoa. They reflect patterns seen in almost all English-speaking and Northern European countries (Kristjansson et al. Citation2016; Arnett Citation2018; Vashishtha et al. Citation2020). This international decline in adolescent substance use is not fully understood, but US research shows that the declines across behaviours are linked (Grucza et al. Citation2017; Borodovsky et al. Citation2019), and several studies using data from Europe and North America indicate that less unstructured in-person socialising is an important contributing factor, resulting in fewer opportunities for risk behaviours of all kinds (de Looze et al. Citation2019; Borodovsky et al. Citation2021). Evidence indicates changes in parenting – e.g. less permissive attitudes to adolescent alcohol use and improved parent–child relationships – may also have played a role (Vashishtha et al. Citation2019; Koning et al. Citation2020; Boden et al. Citation2021).

The popular idea that young people are too busy on their smartphones to engage in substance use is not supported by empirical research. Rather than having a protective effect, there is consistent individual-level evidence that heavy internet users (particularly social media users) are more likely to drink and smoke than those less active online (Vannucci et al. Citation2020). At the country level, there is no relationship between trends in online activity (including gaming) and substance use (de Looze et al. Citation2019; Vashishtha et al. Citation2022).

New Zealand research shows young people’s attitudes to smoking and drinking and the age at which these behaviours are considered acceptable has shifted substantially. The proportion of secondary students aged under 16 who thought regular smoking and drinking was OK in people their age fell by over 70% and 62%, respectively, between 2001 and 2012 and was a key driver of the declines in adolescent drinking and smoking in Aotearoa over that period (Ball Citation2019). This shift is reflected internationally in delayed uptake of tobacco and alcohol in more recent cohorts in the US and Australia as well as Aotearoa (Keyes et al. Citation2018; Ball Citation2019; Livingston et al. Citation2020). Qualitative research from Europe and Australia suggests that alcohol may play a less central role in youth culture than it did in previous generations, with a diversity of youth lifestyles (including non-drinking lifestyles) seen as a legitimate and socially acceptable (Törrönen et al. Citation2019; Scheffels et al. Citation2020; Caluzzi et al. Citation2022).

Has decreased substance use resulted in decreased harm?

It is important to distinguish between substance use (which is not necessarily harmful) and substance-related harm. Nutt et al. developed a widely-used framework for defining drug harm which divides harm into two categories: ‘harm to self’ and ‘harm to others’ which are further divided in 16 sub-categories (Nutt et al. Citation2010). This framework has not yet been explicitly tested for applicability to adolescents, and it is possible that adolescents might rank or define harms differently. For example, a recent Australian study found that two of the harms most commonly experienced by youth were that someone else’s drinking had ‘ruined a party or social gathering’ or ‘ruined your clothes or other belongings’ (Lam et al. Citation2019). These harms do not neatly fit into Nutt et al.’s framework, suggesting the need for a substance-related harm construct specifically applicable to adolescents.

Although there are a range of routine data sources in Aotearoa (e.g. emergency department records, police records) that could be used to monitor trends in substance-related harm (Crossin et al. CitationIn press), substance-related harm is not systematically monitored in Aotearoa. Therefore, there is little direct evidence about the impacts of declining substance use. However, trends in several indicators suggest that declining substance use has had positive effects on adolescent health, safety and wellbeing.

Police estimate that about one-third of crime is alcohol-related (Law Commission Citation2009). Therefore, it is unsurprising that declining adolescent drinking has corresponded with a decline in juvenile crime in Aotearoa. For example, the youth offending rate declined by over 60% in the decade between 2009/10 and 2019/20, and by nearly 70% for Māori (Ministry of Justice Citation2020). Although the crime decline undoubtedly has multiple causes, decreasing prevalence and frequency of adolescent binge drinking is almost certainly one of them. What some have referred to as the de-facto decriminalisation of drug use (with police directed not to prosecute low level drug offences unless in the public interest) is also likely to be a contributor.

Declining rates of sexual activity, teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections have also occurred alongside the decline in substance use in adolescents (ESR Citation2019; Clark et al. Citation2020). Parallel trends in sexual behaviour and substance use may have common underlying drivers (e.g. less in-person socialising), but a causal relationship is also plausible. Intoxication is associated with disinhibition and increased likelihood of risky sexual behaviour (Ritchwood et al. Citation2015), so it is possible that the decline in binge drinking and marijuana use has contributed to these positive sexual health trends.

The decline in substance use is also likely to have contributed to the decline in adolescent mortality since the late 1990s (), since substance use is linked to the two leading causes of death in this age group – motor vehicle accidents and suicide. Fatal road crashes involving adolescents have declined substantially, and although the reasons are multi-factorial (e.g. safer roads, safer vehicles, fewer adolescents driving), a decrease in alcohol- and drug-impaired driving among young people is likely to have contributed. The Youth2000 surveys show that the proportion of secondary students involved in dangerous driving (either as a driver or passenger) fell substantially between 2001 and 2019 (Fleming et al, overview paper in this special issue).

Figure 5. Mortality rates, 15–19 years – All cause, suicide and motor vehicle accidents, Aotearoa, 1996–2017. Source: Ministry of Health.

Adolescent suicide rates have decreased since the late 1990s (), when adolescent substance use was at its peak. The prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of depression among secondary school students approximately doubled between 2012 and 2019 (Fleming, Tiatia-Seath, et al. Citation2020), but was not accompanied by an increase in teen suicide overall, or among rangatahi Māori (Ministry of Health Citation2021b). As discussed above, substance use and suicidal behaviour may be causally linked, with evidence strongest for alcohol. Therefore, lower levels of substance use (particularly binge drinking) may have helped to keep youth suicide rates relatively stable in the face of substantial increases in adolescent mental health problems.

Implications for policy and practice

As discussed, substance use in adolescents has declined markedly in Aotearoa over the past two decades, and ethnic disparities have narrowed in absolute terms. However, we appear to be at a turning point in adolescent substance use trends. What should be done to address recent plateaus and increases in substance use?

Surveillance of substance use across the adolescent age range is currently inadequate in Aotearoa, as is monitoring of substance-related harm. There is a lack of regular in-depth information on most topics, and (with the exception of the ASH Year 10 survey, which only covers tobacco and e-cigarette use among a limited age range) data series are lacking, meaning policy makers are poorly placed to quickly detect and respond to changes. To inform policy and practice, we need regular data collection on all substances and across the full adolescent age range, covering not only prevalence of use but also frequency and dosage, reasons for use, how substances are sourced, attitudes and beliefs, and relevant risk factors. Emerging issues such as e-cigarette use and cannabis vaping need particular attention, since products and behaviours are evolving rapidly, creating knowledge gaps and making existing survey question wording out-of-date (Ball, Zhang et al. Citation2021). Future monitoring should be designed not only to capture changing patterns of use but also to enhance understanding of why changes are occurring. Substance use does not always lead to harm, and we need a better understanding of the nature and prevalence of substance-related harm in adolescents, predictors of harm, and how harm (as opposed to use) can be prevented. Contemporary thinking about indigenous data sovereignty (Te Mana Raraunga Māori Data Sovereignty Network Citation2022) needs to be incorporated into our surveillance systems and research methods.

We also need greater investment in policies aimed at preventing substance-related harm, including broad-based measures (e.g. secure and healthy housing, decent family incomes and freedom from discrimination), and substance-specific measures (e.g. reduced availability of alcohol). Educational programmes aimed at reducing substance use are generally ineffective unless wider structural influences on health behaviour are also addressed (Skager Citation2007; Jancey et al. Citation2016). Policy and practice development should explicitly consider inequities and the likely impact (intended and unintended) of proposed changes on inequities. The recently announced Smokefree2025 Action Plan provides an example of a comprehensive evidence-based approach that is likely to greatly reduce tobacco-related harm and inequities in Aotearoa by making tobacco less available and less addictive to young people. The focus is on reducing uptake via product and supply-side regulation, rather than educational approaches. Unfortunately, the Government has been less responsive to evidence-based recommendations to reduce alcohol harm, for example the Law Commission Review of 2010 and the Inquiry into Mental Health and Addictions of 2018. Alcohol harm would be greatly reduced if the WHO’s ‘best buys’ were introduced: restrict availability (e.g. licensng hours and density of off-licences), restrict marketing (e.g. disallow alcohol sponsorship in sports) and increase the price of alcohol (e.g. through increased excise tax and/or minimum unit pricing) (World Health Organization Citation2018). Although cannabis remains illegal in Aotearoa, its use is more widespread than tobacco among young people and new high-potency cannabis products are increasingly available. Cannabis should be included in the remit of the national Health Promotion Agency, Te Hiringa Hauora, as part of a health-based approach to illicit drug use.

The upcoming health reforms and establishment of the Māori Health Authority will empower Iwi, hapū, Māori communities and Māori providers to develop and implement Māori-led solutions. Māori and Pacific leaders (including adolescent leaders) need to be at the policy table and leading community action to reduce substance-related harm among young people. The Covid19 pandemic has demonstrated how quickly and effectively Māori and Pacific communities can mobilise when resourced and empowered to do so. Youth voices need to be heard, with acknowledgement that today’s adolescents have grown up in a very different world from that of the 1970s–1990s when most of today’s decision-makers were teenagers.

Strengths and limitations

This review draws on a wide range of New Zealand data sources, and therefore presents a more comprehensive picture of adolescent substance use trends than a single data source allows. However, it also highlights significant gaps in the available data, and associated knowledge gaps. At the time of writing, the 2021 ASH Year 10 Snapshot findings on regular smoking and vaping had not been released publicly, so those measures could not be updated. Due to space limitations, substance use in rainbow youth, migrant youth and other specific groups was not covered in detail. Our narrative review of the causes and consequences of adolescent substance use draws on the authors’ expertise in these topic areas, since systematic review methods were not appropriate for such a broad topic area. Lack of systematic literature search and selection methods could have resulted in bias or omissions.

Conclusions

Trends in adolescent substance use are distinct from adult trends. Use of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis among adolescents in Aotearoa peaked in the late 1990s/early 2000s, then declined rapidly, and levels of use are now much lower than 20 years ago. However, levels of adolescent binge drinking remain high by international standards, and disparities in tobacco and cannabis use by ethnicity and socioeconomic status are wide. Furthermore, evidence suggests we may again be at a turning point, with long-term declines stalling or reversing since about 2014–2016, and e-cigarette use emerging as a new risk.

Therefore, ongoing monitoring of substance use and substance-related harm is vital, along with redoubled efforts to prevent or reduce substance use and associated harm. Māori, Pacific and youth leadership is needed at every level. Because risk of harm is strongly associated with the context for use (i.e. it is higher in young people who have experienced childhood adversity and/or marginalisation), harm-reduction includes ensuring every child and adolescent has the basics for psychosocial and physical wellbeing: love, safety, a secure home, food on the table, freedom from discrimination and support to overcome life’s challenges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arnett JJ. 2018. Getting better all the time: trends in risk behavior among American adolescents since 1990. Arch Sci Psychol. 6(1):87–95.

- Arnull E, Ryder J. 2019. ‘Because it’s fun’: English and American girls’ counter-hegemonic stories of alcohol and marijuana use. J Youth Stud. 22(10):1361–1377.

- ASH (NZ). 2014. Factsheet: youth smoking in New Zealand by socio-economic status. Auckland: ASH New Zealand.

- ASH (NZ). 2018. 2016 ASH Year10 snapshot: smoking by ethnicity. Auckland: ASH New Zealand.

- ASH (NZ). 2020. 2019 ASH Year 10 snapshot: topline results: smoking. Auckland: ASH Action for Smokefree 2025.

- Bagge CL, Conner KR, Reed L, Dawkins M, Murray K. 2015. Alcohol use to facilitate a suicide attempt: an event-based examination. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 76(3):474–481.

- Ball J. 2019. Sex, drugs, smokes and booze: what's driving teen trends? [Doctoral thesis]. Wellington, New Zealand: University of Otago.

- Ball J, Fleming T, Drayton B, Sutcliffe K, Lewycka S, Clark TC. 2021. New Zealand youth19 survey: vaping has wider appeal than smoking in secondary school students, and most use nicotine-containing e-cigarettes. Aust N Z J Public Health. 45(6):546–553.

- Ball J, Gurram N, Martin G. 2020. Adolescent cannabis use continues its downward trend, New Zealand 2012-2018. NZ Med J. 133(1510):91–93.

- Ball J, Sim D, Edwards R, Fleming T, Denny S, Cook H, Clark T. 2019. Declining adolescent cannabis use occurred across all demographic groups and was accompanied by declining use of other psychoactive drugs, New Zealand, 2001–2012. NZ Med J. 132(1500):12–24.

- Ball J, Zhang J, Hammond D, Boden J, Stanley J, Edwards R. 2021. The rise of cannabis vaping: implications for survey design. NZ Med J. 134(1540):95–98.

- Bax T. 2021. The life-course of methamphetamine users in aotearoa/New Zealand: school, friendship and work. J Criminol. 54(4):425–447.

- Boden JM, Crossin R, Cook S, Martin G, Foulds JA, Newton-Howes G. 2021. Parenting and home environment in childhood and adolescence and alcohol use disorder in adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 69(2):329–334.

- Bonino S, Cattelino E, Ciairano S, Mc Donald L, Jessor R. 2005. Adolescents and risk: behavior, functions, and protective factors. New York: Springer.

- Borodovsky JT, Krueger RF, Agrawal A, Elbanna B, de Looze M, Grucza RA. 2021. U.S. trends in adolescent substance use and conduct problems and their relation to trends in unstructured in-person socializing with peers. J Adolesc Health. 69(3):432–439.

- Borodovsky JT, Krueger RF, Agrawal A, Grucza RA. 2019. A decline in propensity toward risk behaviors among U.S. adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 65(6):745–751.

- Caluzzi G, Livingston M, Holmes J, MacLean S, Lubman D, Dietze P, Vashishtha R, Herring R, Pennay A. 2022. Declining drinking among adolescents: are we seeing a denormalisation of drinking and a normalisation of non-drinking? Addiction. 117(5):1204–1212.

- Cerda M, Moffitt TE, Meier MH, Harrington H, Houts R, Ramrakha S, Hogan S, Poulton R, Caspi A. 2016. Persistent cannabis dependence and alcohol dependence represent risks for midlife economic and social problems: a longitudinal cohort study. Clin Psychol Sci. 4(6):1028–1046.

- Chambers T, Stanley J, Signal L, Pearson AL, Smith M, Barr M, Ni Mhurchu C. 2018. Quantifying the nature and extent of children's real-time exposure to alcohol marketing in their everyday lives using wearable cameras: children's exposure via a range of media in a range of key places. Alcohol Alcohol. 53(5):626–633.

- Clark T, Lambert M, Fenaughty J, Tiatia-Seath J, Bavin L, Peiris-John R, Sutcliffe K, Crengle S, Fleming T. 2020. Youth19 Rangatahi Smart Survey, Initial Findings: sexual and reproductive health of New Zealand secondary school students. Wellington: The Youth19 Research Group, University of Auckland & Victoria University of Wellington.

- Connor J, You R, Casswell S. 2009. Alcohol-related harm to others: a survey of physical and sexual assault in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 122(1303):10–20.

- Crengle S, Robinson E, Ameratunga S, Clark T, Raphael D. 2012. Ethnic discrimination prevalence and associations with health outcomes: data from a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of secondary school students in New Zealand. BMC Public Health. 12: Article No. 45.

- Crossin R, Cleland L, Rychert M, Wilkins C, Boden J. In press. Measuring drug harm in New Zealand: a stocktake of current data sources. New Zealand Medical Journal.

- de Looze M, van Dorsselaer S, Stevens G, Boniel-Nissim M, Vieno A, van den Eijnden R. 2019. The decline in adolescent substance use across Europe and North America in the early twenty-first century: a result of the digital revolution? Int J Public Health. 64(4):229–240.

- Esposito-Smythers C, Spirito A. 2004. Adolescent substance use and suicidal behavior: a review with implications for treatment research. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 28(5 Suppl):77S-88S.

- ESR. 2019. STI epidemiology update. New Zealand: ESR.

- Evins AE, Korhonen T, Kinnunen TH, Kaprio J. 2017. Prospective association between tobacco smoking and death by suicide: a competing risks hazard analysis in a large twin cohort with 35-year follow-up. Psychol Med. 47(12):2143–2154.

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. 2009. Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 66(3):260–266.

- Fergusson DM, Swain-Campbell NR, Horwood LJ. 2003. Arrests and convictions for cannabis related offences in a New Zealand birth cohort. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 70(1):53–63.

- Fleming T, Ball J, Peiris-John R, Crengle S, Bavin L, Tiatia-Seath J, Archer D, Clark T. 2020. Youth19 Rangatahi Smart Survey, Initial Findings: substance use. Wellington, New Zealand: Youth19 Research Group, The University of Auckland and Victoria University of Wellington.

- Fleming T, Lee A, Moselen E, Clark T, Dixon R., The Adolescent Health Research Group. 2014. Problem substance use among New Zealand secondary school students: findings from the Youth’12 national youth health and wellbeing survey. Auckland, New Zealand: The University of Auckland.

- Fleming T, Tiatia-Seath J, Peiris-John R, Sutcliffe K, Archer D, Bavin L, Crengle S, Clark T. 2020. Youth19 Rangatahi Smart Survey, Initial Findings: Hauora hinengaro / emotional and mental health. Wellington, New Zealand: The Youth19 Research Group, The University of Auckland and Victoria University of Wellington.

- Giancola PR, Josephs RA, Parrott DJ, Duke AA. 2010. Alcohol myopia revisited: clarifying aggression and other acts of disinhibition through a distorted lens. Perspect Psychol Sci. 5(3):265–278.

- Gray RJ, Hoek J, Edwards R. 2016. A qualitative analysis of ‘informed choice’ among young adult smokers. Tob Control. 25(1):46–51.

- Grucza RA, Krueger RF, Agrawal A, Plunk AD, Krauss MJ, Bongu J, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Bierut LJ. 2017. Declines in prevalence of adolescent substance use disorders and delinquent behaviors in the USA: a unitary trend? Psychol Med. 48(9):1494–1503.

- Grucza RA, Plunk AD, Krauss MJ, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Deak J, Gebhardt K, Chaloupka FJ, Bierut LJ. 2014. Probing the smoking-suicide association: do smoking policy interventions affect suicide risk? Nicotine Tob Res. 16(11):1487–1494.

- Guerin N, White V. 2020. ASSAD 2017 statistics and trends: trends in substance use among Australian secondary students. 2nd ed. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria.

- Gurram N, Brown L. 2020. Substance use behaviour among 14 and 15-year-olds: results from a nationally representative survey. Wellington, New Zealand: Health Promotion Agency/Te Hiringa Hauora.

- Gurram N, Thomson G, Wilson N, Hoek J. 2019. Electronic cigarette online marketing by New Zealand vendors. NZ Med J. 132(1506):20–33.

- Hall WD, Patton G, Stockings E, Weier M, Lynskey M, Morley KI, Degenhardt L. 2016. Why young people's substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry. 3(3):265–279.

- Han B, Compton WM, Einstein EB, Volkow ND. 2021. Associations of suicidality trends with cannabis use as a function of sex and depression status. JAMA Netw Open. 4(6): Article No. e2113025.

- Hawton K, Fagg J, Mckeown S. 1989. Alcoholism, alcohol and attempted suicide. Alcohol Alcohol. 24(1):3–9.

- Heim D, Monk RL, Qureshi AW. 2021. An examination of the extent to which drinking motives and problem alcohol consumption vary as a function of deprivation, gender and age. Drug Alcohol Rev. 40(5):817–825.

- Heinz AJ, Beck A, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Sterzer P, Heinz A. 2011. Cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms of alcohol-related aggression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 12(7):400–413.

- Huckle T, Pledger M, Casswell S. 2012. Increases in typical quantities consumed and alcohol-related problems during a decade of liberalizing alcohol policy. J Studies Alcohol Drugs. 73(1):53–62.

- Huckle T, You RQ, Casswell S. 2011. Increases in quantities consumed in drinking occasions in New Zealand 1995-2004. Drug Alcohol Rev. 30(4):366–371.

- Irner TB. 2012. Substance exposure in utero and developmental consequences in adolescence: a systematic review. Child Neuropsychol. 18(6):521–549.

- Jackson N, Denny S, Sheridan J, Fleming T, Clark T, Peiris-John R, Ameratunga S. 2017. Uneven reductions in high school students’ alcohol use from 2007 to 2012 by age, sex, and socioeconomic strata. Subst Abus. 38(1):69–76.

- Jancey J, Barnett L, Smith J, Binns C, Howat P. 2016. We need a comprehensive approach to health promotion. Health Promot J Austr. 27(1):1–3.

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. 2020. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use 1975-2019: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

- Kalafatelis E, McMillen P, Palmer S. 2003. Youth and Alcohol: 2003 ALAC Youth Drinking Monitor. Report prepared for the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand by BRC Marketing & Social Research. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency; [accessed 16 December 2021]. https://www.hpa.org.nz/sites/default/files/imported/field_research_publication_file/YDM2003full.pdf.

- Kepple NJ. 2018. Does parental substance use always engender risk for children? Comparing incidence rate ratios of abusive and neglectful behaviors across substance use behavior patterns. Child Abuse Negl. 76:44–55.

- Keyes KM, Rutherford C, Miech R. 2018. Historical trends in the grade of onset and sequence of cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use among adolescents from 1976-2016: implications for ‘gateway’ patterns in adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 194:51–58.

- Kolves K, Chitty KM, Wardhani R, Varnik A, de Leo D, Witt K. 2020. Impact of alcohol policies on suicidal behavior: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(19):7030–7054.

- Koning I, de Looze M, Harakeh Z. 2020. Parental alcohol-specific rules effectively reduce adolescents’ tobacco and cannabis use: a longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 216: Article No. 108226.

- Korhonen T, Sihvola E, Latvala A, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Nurnberger J, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. 2018. Early-onset tobacco use and suicide-related behavior – a prospective study from adolescence to young adulthood. Addict Behav. 79:32–38.

- Kristjansson AL, Sigfusdottir ID, Thorlindsson T, Mann MJ, Sigfusson J, Allegrante JP. 2016. Population trends in smoking, alcohol use and primary prevention variables among adolescents in Iceland, 1997-2014. Addiction. 111(4):645–652. English.

- Lam T, Laslett AM, Ogeil RP, Lubman DI, Liang W, Chikritzhs TN, Gilmore WG, Lenton SR, Fischer J, Aiken A, et al. 2019. From eye rolls to punches: experiences of harm from others’ drinking among risky-drinking adolescents across Australia. Public Health Res Pract. 29: Article No. e2941927.

- Laviolette SR. 2021. Molecular and neuronal mechanisms underlying the effects of adolescent nicotine exposure on anxiety and mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 184: Article No. 108411.

- Law Commission. 2009. Alcohol in our lives: an issues paper on the reform of New Zealand’s liquor laws. Wellington: Law Commission.

- Livingston M, Holmes J, Oldham M, Vashishtha R, Pennay A. 2020. Trends in the sequence of first alcohol, cannabis and cigarette use in Australia, 2001–2016. Drug Alcohol Depen. 207: Article No. 107821.

- Lucas N, Gurram N, Thimasarn-Anwar T. 2020. Smoking and vaping behaviours among 14 and 15-year-olds: results from the 2018 Youth Insights survey. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency/Te Hiringa Hauora Research and Evaluation Unit.

- McManama O'Brien KH, Becker SJ, Spirito A, Simon V, Prinstein MJ. 2014. Differentiating adolescent suicide attempters from ideators: examining the interaction between depression severity and alcohol use. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 44(1):23–33.

- Mereish EH. 2019. Substance use and misuse among sexual and gender minority youth. Curr Opin Psychol. 30:123–127.

- Ministry of Health. 2016. Annual update of key results 2015/16, New Zealand Health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health. 2021a. Health effects of smoking. Wellington: Ministry of Health; [accessed 2021 13 December]. https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/healthy-living/addictions/quitting-smoking/health-effects-smoking.

- Ministry of Health. 2021b. Mortality web tool. Wellington: Ministry of Health; [accessed 13 December 2021]. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/mortality-web-tool.

- Ministry of Health. 2021c. New Zealand Health Survey Annual Data Explorer 2020/2021; [accessed 20 September 2021]. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/annual-update-key-results-2020-21-new-zealand-health-survey.

- Ministry of Justice. 2020. Youth Justice Indicators Summary Report. Wellington Ministry of Justice; [accessed 28 September 2021]. https://www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/Youth-Justice-Indicators-Summary-Report-December-2020-FINAL.pdf.

- Moewaka Barnes H, McCreanor T. 2019. Colonisation, hauora and whenua in Aotearoa. J R Soc N Z. 49(sup1):19–33.

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi H-y. 2014. Early adolescent patterns of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana polysubstance use and young adult substance use outcomes in a nationally representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depen. 136:51–62.

- Moustafa AA, Parkes D, Fitzgerald L, Underhill D, Garami J, Levy-Gigi E, Stramecki F, Valikhani A, Frydecka D, Misiak B. 2018. The relationship between childhood trauma, early-life stress, and alcohol and drug use, abuse, and addiction: an integrative review. Curr Psychol. 40(2):579–584.

- Mund M, Louwen F, Klingelhoefer D, Gerber A. 2013. Smoking and pregnancy–a review on the first major environmental risk factor of the unborn. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 10(12):6485–6499.

- Muthumalage T, Friedman MR, McGraw MD, Ginsberg G, Friedman AE, Rahman I. 2020. Chemical constituents involved in e-cigarette, or vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI). Toxics. 8(2):25–37.

- NHS Digital. 2021. Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England; [accessed 23 July 2021]. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/areas-of-interest/public-health/smoking-drinking-and-drug-use-among-young-people-in-england.

- Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD. 2010. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. The Lancet. 376(9752):1558–1565.

- OECD. 2017. OECD family database. child outcomes 4.4: teenage suicides (15-19 years old). Paris: OECD; [accessed 2021 December 13]. https://www.oecd.org/els/family/CO_4_4_Teenage-Suicide.pdf.

- Orri M, Seguin JR, Castellanos-Ryan N, Tremblay RE, Cote SM, Turecki G, Geoffroy MC. 2020. A genetically informed study on the association of cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco smoking with suicide attempt. Mol Psychiatry. 26(9):5061–5070.

- Pasch KE, Latimer LA, Cance JD, Moe SG, Lytle LA. 2012. Longitudinal bi-directional relationships between sleep and youth substance use. J Youth Adolesc. 41(9):1184–1196.

- Patrick ME, Evans-Polce RJ, Kloska DD, Maggs JL. 2019. Reasons high school students use marijuana: prevalence and correlations with use across four decades. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 80(1):15–25.

- Ritchwood TD, Ford H, DeCoster J, Sutton M, Lochman JE. 2015. Risky sexual behavior and substance use among adolescents: a meta-analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev. 52:74–88.

- Romer D, Reyna VF, Satterthwaite TD. 2017. Beyond stereotypes of adolescent risk taking: placing the adolescent brain in developmental context. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 27:19–34.

- Schane RE, Ling PM, Glantz SA. 2010. Health effects of light and intermittent smoking: a review. Circulation. 121(13):1518–1522.

- Scheffels J, Buvik K, Tokle R, Rossow I. 2020. Normalisation of non-drinking? 15-16-year-olds’ accounts of refraining from alcohol. Drug Alcohol Rev. 39(6):729–736.

- Scoccianti C, Cecchini M, Anderson AS, Berrino F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Espina C, Key TJ, Leitzmann M, Norat T, Powers H, et al. 2016. European code against cancer 4th edition: alcohol drinking and cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 45:181–188.

- Sher L, Oquendo MA, Richardson-Vejlgaard R, Makhija NM, Posner K, Mann JJ, Stanley BH. 2009. Effect of acute alcohol use on the lethality of suicide attempts in patients with mood disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 43(10):901–905.

- Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. 2014. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 18(1):75–87.

- Skager R. 2007. Replacing ineffective early alcohol/drug education in the United States with age-appropriate adolescent programmes and assistance to problematic users. Drug Alcohol Rev. 26(6):577–584.

- Slade EP, Stuart EA, Salkever DS, Karakus M, Green KM, Ialongo N. 2008. Impacts of age of onset of substance use disorders on risk of adult incarceration among disadvantaged urban youth: a propensity score matching approach. Drug Alcohol Depend. 95(1-2):1–13.

- St Helen G, Eaton DL. 2018. Public health consequences of e-cigarette use. JAMA Intern Med. 178(7):984–986.

- Taylor B, Irving HM, Kanteres F, Room R, Borges G, Cherpitel C, Greenfield T, Rehm J. 2010. The more you drink, the harder you fall: a systematic review and meta-analysis of how acute alcohol consumption and injury or collision risk increase together. Drug Alcohol Depend. 110(1-2):108–116.

- Te Mana Raraunga Māori Data Sovereignty Network. 2022. Te Mana Raraunga Māori Data Sovereignty Network. Aotearoa New Zealand; [accessed 4 March 2022]. https://www.temanararaunga.maori.nz/nga-rauemi.

- Theodore R, Ratima M, Potiki T. 2020. Cannabis, the cannabis referendum and māori youth: a review from a lifecourse perspective. Kōtuitui. 16(1):1–17.

- Törrönen J, Roumeliotisa F, Samuelssona E, Krausa L, Rooma R. 2019. Why are young people drinking less than earlier? Identifying and specifying social mechanisms with a pragmatist approach. Int J Drug Policy. 64:13–20.

- Turecki G, Brent DA, Gunnell D, O'Connor RC, Oquendo MA, Pirkis J, Stanley BH. 2019. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 5(1): Article No. 74.

- Vannucci A, Simpson EG, Gagnon S, Ohannessian CM. 2020. Social media use and risky behaviors in adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Adolesc. 79:258–274.

- Vapemate. 2021. Make your own cannabis eliquid NZ. New Zealand: Vapemate; [accessed 17 December 2021]. https://vapemate.co.nz/pages/make-your-own-cannabis-e-liquid.

- Vashishtha R, Holmes J, Pennay A, Dietze PM, Livingston M. 2022. An examination of the role of changes in country-level leisure time internet use and computer gaming on adolescent drinking in 33 European countries. Int J Drug Policy. 100: Article No. 103508 .

- Vashishtha R, Livingston M, Pennay A, Dietze P, MacLean S, Holmes J, Herring R, Caluzzi G, Lubman DI. 2019. Why is adolescent drinking declining? A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Addict Res Theory. 28(4):275–288.

- Vashishtha R, Pennay A, Dietze P, Marzan MB, Room R, Livingston M. 2020. Trends in adolescent drinking across 39 high-income countries: exploring the timing and magnitude of decline. Eur J Public Health. 31(2):424–431.

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. 2014. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 370(23):2219–2227.

- Walker N, Parag V, Wong SF, Youdan B, Broughton B, Bullen C, Beaglehole R. 2020. Use of e-cigarettes and smoked tobacco in youth aged 14–15 years in New Zealand: findings from repeated cross-sectional studies (2014–19). Lancet Public Health. 5(4):e204–e212.

- Werner AK, Koumans EH, Chatham-Stephens K, Salvatore PP, Armatas C, Byers P, Clark CR, Ghinai I, Holzbauer SM, Navarette KA, et al. 2020. Hospitalizations and deaths associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 382(17):1589–1598.

- Wilson N, Summers JA, Ait Ouakrim D, Hoek J, Edwards R, Blakely T. 2021. Improving on estimates of the potential relative harm to health from using modern ENDS (vaping) compared to tobacco smoking. BMC Public Health. 21(1): Article No. 2038.

- Witt K, Chitty KM, Wardhani R, Varnik A, de Leo D, Kolves K. 2021. Effect of alcohol interventions on suicidal ideation and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 226: Article No. 108885.

- World Health Organization. 2018. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization.