?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) framework has highlighted the link between an adverse early life environment and later disease risk. There is an increasing focus on adolescents as the next generation of parents as DOHaD agents of change to break the disease cycle. However, DOHaD awareness in adolescents is key to enabling knowledge uptake and behavioural change, particularly in Pacific adolescents who have a higher non-communicable disease (NCD) burden. The present study investigated understanding of DOHaD-related concepts among Pacific, Māori and other ethnic groups in New Zealand (ages 16–19 years, n = 209). Awareness of the term NCDs was low across all groups with awareness of the term DOHaD or the First 1000 Days lower in the Pacific group compared to others. Similarly, awareness of some key DOHaD concepts was low overall with some gender differences in response within ethnicity. Interestingly, adolescents' understanding that the early life nutritional environment can impact health across the life-course diminishes significantly with each advancing life-course stage. These results indicate that both education and healthcare DOHaD-related health promotion are lacking with a need for increased engagement with adolescents, particularly Pacific adolescents, to develop and communicate DOHaD content and messaging relevant to this demographic.

Introduction

Life course health and wellbeing trajectories are often set during the early-life developmental stage of an individual's life (Gluckman and Hanson Citation2006; Hanson and Gluckman Citation2014). The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) framework highlights that exposure to adverse early life environments can modify latent phenotypes (Gluckman et al. Citation2011) and contribute to the alteration of an individual's susceptibility to disease risk later in life (Jiang Citation2016). Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) represent the most common diseases spanning the life-course and have transgenerational impacts. Between the ages of 30 and 69, more than 15 million people die prematurely from NCDs annually (World Health Organization Citation2021). Increasing our understanding of the DOHaD contribution to NCD risk and early life ‘developmental programming’ (Bay et al. Citation2019) enables the development of targeted risk reduction strategies that offer opportunities for disease ‘circuit breakers’ can interrupt the transgenerational cycle of NCD risk globally (Chestnov et al. Citation2013). Social determinants of health are complex and significantly affect health outcomes. These include multidimensional factors linked to an individual’s birthplace, upbringing, activities, residence, workplaces, socioeconomic and environmental structures (Chaturvedi et al. Citation2024). Literature underscores the importance of focusing on enhancing educational opportunities, income distribution, health-related behaviours, and access to healthcare as efforts to mitigate inequalities in health due to NCDs (Andrade et al. Citation2023).

The translation of DOHaD knowledge into practice is critical for encouraging evidence-based action that supports later-life disease prevention strategies (Jeet et al. Citation2018). Although NCD prevention initiatives often focus on optimisation during pregnancy and the First 1000 Days (conception until 2 years of age) (World Health Organization Citation2018) or lifecourse approaches to healthy aging (Kuruvilla et al. Citation2018), there is increasing interest in adolescence as a critical window to convey DOHaD knowledge to the next generation of parents. As such, health promotion and knowledge translation of DOHaD concepts have been undertaken with adolescents in countries such as New Zealand (NZ) (Bay et al. Citation2012), Japan (Oyamada et al. Citation2018), Tonga (Bay et al. Citation2016), Uganda (Macnab and Mukisa Citation2018), United Kingdom (Grace et al. Citation2012) and The Cook Islands (Bay et al. Citation2017b). This work is also further supported by the World Health Organisation with proven success in not only engaging youth via the Health Promoting School model, but also improving youth health behaviours (Stewart-Brown Citation2006; Tang et al. Citation2008; St Leger and Young Citation2009; Macnab Citation2013).

A recent systematic review by our group highlighted that adolescent baseline understanding or DOHaD concepts was consistently low although noted a lack of studies in this area, particularly in population groups characterised by a high NCD burden (Tohi et al. Citation2023). In the NZ context, awareness of DOHaD concepts has received increasing attention, particularly given the disparity in NCD prevalence among Pacific and Indigenous Māori communities (Merriman and Wilcox Citation2018). The prevalence of NCDs, such as cardiovascular disease, some cancers, Type 2 diabetes and obesity, is disproportionately higher among Pacific people compared to other ethnic groups in NZ (Winter-Smith et al. Citation2021; Cleverley et al. Citation2023). For example, 71.3% of Pacific people in NZ are affected by obesity compared to 50.8% in Māori and 31.9% in European or other ethnic groups (Ministry of Health Citation2021). The NZ Health Survey 2021 also reported that 35.3% of Pacific children and 17.8% of Māori children were living with obesity (Ministry of Health Citation2021). The high prevalence rates of obesity in these youthful populations highlight the need for interventions during adolescence; a period where experimentation and increased freedom and agency related to dietary and lifestyle choices occur, and where such behaviours can track into adulthood (Epstein and Wrotniak Citation2010). In this context, improved DOHaD awareness during the period of adolescence could help equip and empower adolescents with the necessary knowledge and capabilities to be catalysts of change in their families, schools and communities (Tohi et al. Citation2022).

Previous work by our group has highlighted a marked disconnect between where DOHaD research is undertaken and where the most significant NCD disease burden exists (Tu’akoi et al. Citation2020). As such, improving DOHaD understanding in the most at-risk populations is key to informing the development of effective, targeted strategies that can contribute to reducing the incidence of NCDs globally. Earlier work in the NZ school-based setting highlighted that engagement with 11–14-year-olds to improve health literacy and understanding of basic DOHaD concepts resulted in positive behavioural changes, but this was only followed through to six months post-intervention (Bay et al. Citation2017). A further study in the United Kingdom showed that positive behavioural changes following an intervention to improve knowledge around DOHaD concepts were not sustained beyond 12 months and highlighted that the mode of engagement with adolescents was key to sustainable impact (Woods-Townsend et al. Citation2018). Thus, current interventions may not be appropriate and emphasises the need for culturally and contextually relevant approaches to be undertaken in this area.

There are currently no data on the understanding of DOHaD concepts among Pacific adolescents based in NZ. The current study investigated the level of knowledge around key DOHaD concepts among Pacific adolescents compared to adolescents across other ethnic groups in NZ. This new knowledge will offer important information that can guide researchers in developing potential education and public health promotion strategies around this concept that are culturally and contextually relevant. Investment in today's adolescents has the potential to yield significant dividends by enabling them to act as NCD ‘circuit breakers’ to mitigate disease risk across future generations.

Method

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (Reference number: 25604). The study is a cross-sectional survey of adolescents aged 16–19 years living in NZ. All adolescents aged 16–19 years old living in NZ who had access to a computer/tablet or a phone during the administration of the Qualtrics survey from April 2023 to November 2023 were eligible to participate.

Online questionnaire

A standardised questionnaire which examines public understanding of DOHaD concepts and has been previously described by our group and others was utilised for this study (Gage et al. Citation2011; Bay et al. Citation2012). Of relevance to the current study, consultations have previously been held with Cook Island Māori community leaders and health professionals to enable contextualisation of the survey tool. Questions assessed awareness of basic DOHaD concepts related to the impact of nutritional exposures in early life on health and wellbeing throughout the lifecourse. The questionnaire consisted of two ‘Yes/No’ questions relating to awareness of NCDs and the phrases ‘DOHaD’ or ‘First 1000 Days’, followed by ten statements utilising Likert attitude scales that explored awareness of life course determinants of health and well-being. The statements are as follows:

Statement (i): The food we eat affects our health and wellbeing

Statement (ii): A mother’s health BEFORE pregnancy affects the health of the baby (fetus) during pregnancy

Statement (iii): A father’s health BEFORE his partner becomes pregnant affects the health of the baby (fetus) during pregnancy

Statement (iv): The food a mother eats DURING pregnancy affects the health of the baby (fetus) during the pregnancy

Statement (v): The food a mother eats DURING pregnancy affects the health of the baby in the FIRST TWO YEARS of life

Statement (vi): The food a mother eats DURING pregnancy affects the health of the baby throughout CHILDHOOD

Statement (vii): The food a mother eats DURING pregnancy affects the health of the baby throughout ADULTHOOD

Statement (viii): The food that a CHILD is fed during the first two years of life affects their health throughout CHILDHOOD

Statement (ix): The food that a CHILD is fed during the first two years of life affects their health throughout ADULTHOOD

Statement (x): A mother’s exposure to tobacco smoke DURING pregnancy affects the health of the child

The online software platform Qualtrics was used for data collection. The survey began with written explanations of the study and a link to a participant information sheet. Once participants indicated that they consented to the survey, two eligibility questions were presented. To be eligible for the survey, participants needed to be at least 16 years of age (but no older than 19 years) and be able to understand English. Participation in the survey was entirely voluntary and participants could skip questions or exit the survey at any time. Participant information was anonymous, as names and identifying information were not recorded.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited via social media advertising (Facebook and Instagram), research team networks and other local networks focusing on NZ Pacific community members. Social media advertisements ran from the 3rd of March to 31st of July 2023. The survey was made available from when the social media advertisement began and closed off in November 2023. We started with a focus on recruitment from social media and ended with more focus on utilising networks to increase participation of Pacific and Māori adolescents. Advertisements were targeted based on the inclusion criteria and to obtain a representative cross-section of adolescents across NZ and in Auckland. As the risks of developing NCDs are higher amongst Māori and Pacific populations, some oversampling of these ethnic groups was attempted to obtain adequate data representing these perspectives. Snowball sampling was also utilised, where participants were invited to share the questionnaire link with their friends and family upon completion.

Statistical analyses

Demographic and socioeconomic data were measured by self-report. The majority of the participants were from the Auckland region (74.2%), with some representation from all across NZ, from Northland through to Otago (25.8%). Statistical analysis showed no significant difference in participant responses to DOHaD-related concepts regardless of where in NZ they resided. Likewise, statistical analysis showed no significant difference in participant responses regardless of whether one was employed or unemployed at the time of the survey. Moreover, in education, there was no significant difference in participant responses between those with identified educational backgrounds and those with no identified educational background.

Ethnicity was assessed using the standard total response measure developed for the NZ census (Statistics New Zealand Citation2005), where participants can select all of the ethnic groups they identify with. A follow-up question was then asked to participants regarding which ethnic group they identify with most. To facilitate statistical analyses for participants that did not prioritise a single ethnic group, discrete ethnic populations were created using a prioritisation method, where participants were assigned to one ethnic group in the following order: Māori (Indigenous people of NZ); Pacific (includes Samoa, Tonga, Cook Island, and other Pacific Islands); Asian; different ethnicities; and European (Statistics New Zealand Citation2005). The responses were grouped to Pacific vs Māori vs Other ethnic groups in preparation for the analysis of the data. The response choices for Likert questions were ‘Agree’, ‘Disagree’ or ‘I Don't Know’. ‘I Don't Know’ was coded as neither ‘Agree’ nor ‘Disagree’ as published in previous literature (Al-Haqwi Citation2010).

In this questionnaire, participants could identify their gender as ‘Male’, ‘Female’, ‘Gender diverse’ or ‘Prefer not to say’. Six participants preferred not to say, while one participant identified as gender diverse. Due to the low power of responses in these groups, the analysis focused primarily on comparing male and female responses within each ethnic group.

Terminology definition provided by the participants had to be specific for it to be accepted as a correct response. A correct definition includes explanations of how exposures to adverse early life environments can increase a person’s risk for developing NCDs in later life. An incorrect definition had answers that did not provide an explanation that aligned with the terms. They indicated that they did not know or give a description of a health complication instead of the link between early life exposure and later life health. The main part of this survey consisted of ten statements. Nine statements were employed to explore adolescents’ awareness of DOHaD concepts, and one was used as the control statement for the survey.

Descriptive statistics were used to identify frequencies. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 29.0, IBM Statistics) to compare responses between different ethnic groups and genders. One-way ANOVAs were used to compare between the age means across the ethnic groups. For identification of which age means were different from each other, we carried out a Post Hoc test with adjusted p-values, Bonferroni method (Bland and Altman Citation1995). Variance in the frequency of Yes/No responses relating to awareness of the terms ‘DOHaD’ or ‘First 1000 Days’ was compared between genders within different ethnic groups using a Chi-Square test with adjusted p-values. For the responses to the statements, we performed Chi-square tests. However, due to the Chi-Square assumptions being violated (i.e. some missing values and some cells count being lower than the expected count), we utilised Fishers Exact test p-values. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was utilised in this study.

Results

A total of 219 survey responses were collected. After data cleaning, whereby participants who did not identify with any ethnic group or gender were removed, the number of valid survey responses was 209. presents the characteristics of the 209 adolescent respondents.

Table 1. Demographics (age and gender by ethnicity) of the adolescents that participated in the survey (n = 209).

Awareness of terminology – NCDs, DOHaD and First 1000 Days

When asked if participants had heard of the term ‘NCDs’, only 21% of participants responded positively. No significant differences were found among ethnic groups, gender, or age groups. More than half of those who indicated that they had heard of NCDs correctly described what an NCD was and provided at least one correct example. Almost all (99%) participants correctly listed factors that could increase overweight or obesity.

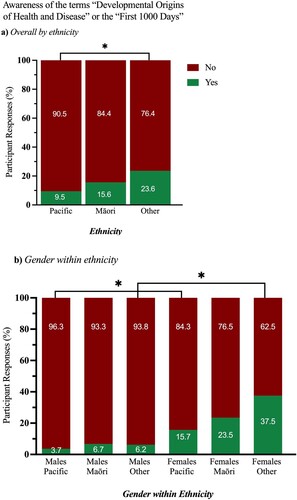

Awareness of the terms ‘DOHaD’ or the ‘First 1000 Days’ was low overall with only 9.5%, 15.6% and 23.6% awareness for Pacific, Māori and Other respectively. Awareness of these terms was significantly lower in Pacific adolescents compared to Other (A). When looking at gender within ethnicity, there was increased awareness of these terms in females in the Pacific and Other groups compared to males (B). Although the awareness rate was higher in Māori females compared to males, it did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 1. Awareness of the terms ‘Developmental Origins of Health and Disease’ or the ‘First 1000 Days’ by A, ethnicity and B, gender within ethnicity. *p < 0.05.

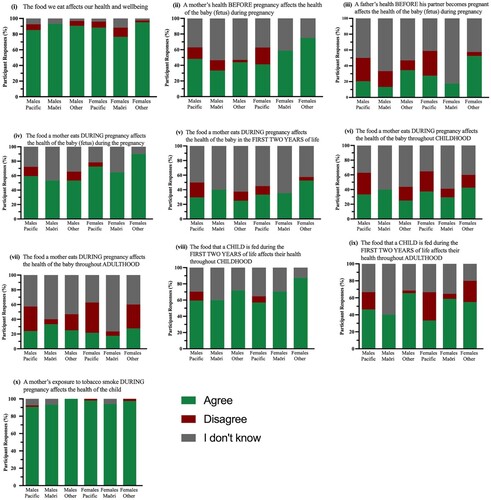

The responses to the 10 statements linked to DOHaD awareness are presented in (i-x). shows the difference in responses between genders across ethnic groups. Statistical analysis showed no significant difference in participant responses to the DOHaD related statements between adolescents who were employed and those unemployed at the time of the survey (p > 0.05 via Chi-Square test). On the other hand, participants with educational backgrounds were more likely to be aware of DOHaD related statements than participants with no educational background (p < 0.05 via Chi-Square test).

Figure 2. Adolescents’ awareness of life course determinants of health and wellbeing as explored in statements (i) to (x).

Table 2. Comparison of response distributions across ethnic groups by gender.

Statement (i): the food we eat affects our health and wellbeing

Agreement with this statement was very high overall for Pacific, Māori and Other with no significant differences across groups (i). There were no differences in awareness between gender within each ethnic group ().

Table 3. Comparison of the distribution of responses detailing the differences in responses between genders within each ethnic group.

Statement (ii): a mother’s health BEFORE pregnancy affects the health of the baby (fetus) during pregnancy

There were no significant differences in awareness in males across the different ethnic groups. There was a significant difference in agreement of this statement in females being significantly lower in Pacific females compared to Other females (41.2% vs 75%, (ii)). This was also reflected in significant differences in the number of Pacific females who disagreed with this term (21.6% in Pacific versus 0% for both Māori and Other groups). There were no differences in responses between gender in the Pacific and Māori groups but awareness was significantly different in males in the Other group compared to females ().

Statement (iii): a father’s health BEFORE his partner becomes pregnant affects the health of the baby (fetus) during pregnancy

Awareness was low overall in males and was not significantly different in males across the different ethnic groups. In females, agreement was significantly lower in Pacific and Māori groups compared to other (p < 0.001, (iii)). Pacific females also disagreed with this statement significantly more than Māori or Other females. Māori females had a significantly higher ‘I don’t know’ response compared to both Pacific and Other groups. Overall, there were no differences between gender within the ethnic groups ().

Statement (iv): the food a mother eats DURING pregnancy affects the health of the baby (fetus) during the pregnancy

There were no significant differences between responses across the different ethnic groups ((iv)). Within ethnicity, overall agreement with this statement was higher in females compared to males but only reached statistical significance in the Other group ().

Statement (v): the food a mother eats DURING pregnancy affects the health of the baby in the FIRST TWO YEARS of life

Overall agreement was low and there were no significant differences across the different ethnic groups ((v)). Within ethnicity, there was an (p = 0.049) increased agreement with this statement in Other females compared to males ().

Statement (vi): the food a mother eats DURING pregnancy affects the health of the baby throughout CHILDHOOD

Agreement of this statement was generally low for all groups and was not different across ethnic groups ((vi)). However, in males, those who disagreed with this statement were significantly different, being higher in Pacific compared to Māori groups. There were no significant differences between gender within each ethnic group ().

Statement (vii): the food a mother eats DURING pregnancy affects the health of the baby throughout ADULTHOOD

There were no differences in male responses across the ethnic groups with those in agreement with this statement being generally low ((vii)). In females, those in agreement with this statement did not differ across ethnicities. However, disagreement was significantly higher in Pacific females compared to Māori females. A ‘I don’t know’ response was significantly higher in Māori females compared to Pacific and Other females. There were no significant differences for gender within ethnicity ().

Statement (viii): the food that a CHILD is fed during the first two years of life affects their health throughout CHILDHOOD

There were no overall differences in awareness of this statement across males for each ethnic group. Agreement of this statement was significantly higher in Other compared to Pacific females ((viii)). This is paralleled by an ‘I don’t know’ response being significantly higher in Pacific compared to Other females. There were no significant differences between gender within each ethnic group ().

Statement (ix): the food that a CHILD is fed during the first two years of life affects their health throughout ADULTHOOD

For males, there were no differences in agreement with this term across the different ethnic groups. However, the ‘Disagree’ response was significantly higher in Pacific males compared to Māori and Other males ((ix)). There were no significant differences in response for females across the ethnic groups. For gender within ethnicity, there was a significant overall difference in the Other group ().

Statement (x): a mother’s exposure to tobacco smoke DURING pregnancy affects the health of the child

The question functions as a control question to validate the survey tool. Awareness of this statement was very high (>90% agreement) across all groups ((x)) with no significant differences across ethnicities. Similarly, there were no significant differences between gender within each ethnic group ().

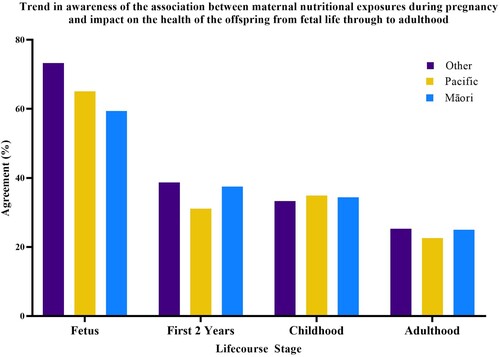

illustrates that the understanding of the impact of the early life environment on later life outcomes decreases with each advancing life course stage. Although awareness that the maternal diet impacts the health of the fetus is generally high overall (66%), there was decreasing awareness of the implications of the early life nutritional environment on impacts across the later lifecourse stages through to adulthood (24.3%).

Discussion

The current study is the first to assess adolescent understanding of DOHaD-related concepts in 16–19 year olds in the NZ setting and examination of potential gender and ethnic-specific differences in DOHaD awareness.

Understanding of NCDs was overall low with only around 20% of adolescents having heard of the term and only half of those being able to correctly describe an example – there we no differences across ethnic groups or gender. Understanding of the terms ‘DOHaD’ or ‘The First 1000 Days’ was similarly low overall cross all ethnic groups but was significantly lower in Pacific adolescents (9.5%) versus Other (23.6%). Further, understanding of these concepts was higher in females compared to males for both the Pacific and Other groups and trended in this direction for Māori. Overall, our findings serve to highlight that understanding of basic descriptors, including those popularised more recently including the ‘First 1000 Days’, is low in NZ adolescents. This general pattern of low awareness is in agreement with previous work showing that, on entry to undergraduate study, most students had no awareness of the terms ‘DOHaD’ or ‘First 1000 Days’ (Oyamada et al. Citation2018). Of note, although this low level of awareness increased to 60% when DOHaD-related concepts were incorporated into the course structure, this still remains inadequate. Our findings are also in agreement with findings of a study based in Africa where the lack of awareness among youth identified an important learning opportunity for DOHaD-related health promotion among this age group (Macnab and Mukisa Citation2018). Further, a programme designed to engage adolescents with DOHaD concepts in the United Kingdom similarly revealed low initial awareness of such concepts. Following an intervention strategy to improve knowledge and lifestyle behaviours, there were improvements in awareness at 12 months but these were not sustained (Woods-Townsend et al. Citation2018).

Although approximately two-thirds of adolescents were aware of the link between maternal nutrition and the health of the fetus, this still remains too low. Moreover, as clearly evidenced by , an understanding that the early life nutritional environment can impact on health across the lifecourse diminishes significantly with each advancing lifecourse stage detailed. Furthermore, Other adolescents showed the most awareness across the lifecourse compared to Pacific and Māori adolescents. The link between maternal nutrition during pregnancy and the health of the offspring during the first two years of life showed Pacific adolescents to be less in agreement than any other ethnic groups. However, current literature lacks an examination as to why knowledge in adolescents diminishes with respect to impact on each advancing lifecourse stage, particularly through a cultural and contextual lens. Thus, focus groups are currently underway to capture adolescents’ perspectives on this stepped reduction in knowledge amongst adolescents living in NZ. As such, this presents a further knowledge gap that requires addressing, particularly in the context of breaking the transgenerational cycle of disease. The differential levels of awareness of the association between nutrition and lifelong health expressed by some adolescents may be influenced by their frames of reference and exposure to ideas from their families, communities, education and society (Oyamada et al. Citation2018). For example, in Pacific cultures, there are known cultural beliefs and ways of life that can influence the health of Pacific individuals and which may provide intervention opportunities to strengthen key protective factors (Lilo et al. Citation2020).

The present study has several limitations. Firstly (with the exception of the question related to NCD descriptors), the survey tool only assesses awareness, as opposed to awareness and understanding of concepts. The Likert style questions do not differentiate between awareness and knowledge with awareness in this study defined as recognition of a concept or phrase. This may be associated with declarative knowledge but may also be present as knowing the idea of a phrase without understanding it (Oyamada et al. Citation2018). Therefore, the statements did not engage participants in questions that could uncover why they select specific responses towards the statements. This gap can potentially be addressed via focus groups as detailed below. Although 219 adolescents were surveyed and the general patterns of awareness aligned with other international surveys in this area, it may not be generalisable to the NZ adolescent demographics, particularly that of Māori adolescents. Despite efforts to increase participation via social media advertisements and the distribution of flyers to different youth groups and organisations, fewer Māori adolescents engaged in the survey and thus are relatively underpowered compared to the Pacific and Other groups. In general, Māori have been found to participate in surveys at much lower rates than other New Zealanders (Fink et al. Citation2011; NZ Ministry of Health Citation2017) and more likely to remove themselves from survey-based studies over time (Satherley et al. Citation2015). We acknowledge that more needs to be done to ensure Māori are represented and empowered to engage in future studies.

A second limitation is around that of culture and context and understanding the rationale between some of the gender and ethnic differences observed. Further independent research is currently underway utilising focus group interviews to uncover the potential reasons as to why some adolescents disagreed with some of the statements presented in the survey. Moreover, exploration of the trends deduced by the results of this study can help health promoters extend and strengthen their work in this field empowering adolescents to understand DOHaD concepts, how it applies to their lives and its impacts on the health of future generations. Given NZ’s proximity to its neighbouring Pacific Island countries, it is in a unique position to work multisectorally and be a leader in system approaches to tackling obesity and NCDs in the Pacific beginning with the reduction of NCD risks within our Pacific communities living in NZ. This requires using the current evidence to help inform on the development of culturally appropriate initiatives aimed at improving DOHaD awareness.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrated generally low awareness of DOHaD concepts with some evidence for gender and ethnicity-related differences that require further exploration. A primary focus around NCDs to date has been on treatment approaches to disease once manifested as opposed to strategies aimed at prevention. However, recent work spanning a range of disciplines has clearly highlighted that a lifecourse approach is required in order to establish an effective framework for NCD prevention (Tohi et al. Citation2022). The next step is to then engage with adolescents to co-develop effective and appropriate resources to promote the importance of the adolescent life stage and to empower them as potential agents of change to break the NCD cycle.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all of the adolescents who gave of their time to participate in this survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Haqwi AI. 2010. Smoking prevalence and smoking cessation services for pregnant women in Scotland. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 5(1):1–6. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-5-1.

- Andrade CAS, Mahrouseh N, Gabrani J, Charalampous P, Cuschieri S, Grad DA, Unim B, Mechili EA, Chen-Xu J, Devleesschauwer B. 2023. Inequalities in the burden of non-communicable diseases across European countries: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. International Journal for Equity in Health. 22(1):140. doi:10.1186/s12939-023-01958-8.

- Bay J, Mora H, Sloboda D, Morton S, Vickers M, Gluckman P. 2012. Adolescent understanding of DOHaD concepts: a school-based intervention to support knowledge translation and behaviour change. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 3(6):469–482. doi:10.1017/S2040174412000505.

- Bay J, Vickers MH, Mora HA, Sloboda DM, Morton SM. 2017. Examining study habits in undergraduate STEM courses from a situative perspective. International Journal of STEM Education. 4(1):1–20. doi:10.1186/s40594-017-0055-6.

- Bay J, Yaqona D, Barrett-Watson C, Tairea K, Herrmann U, Vickers M. 2017. We learnt and now we are teaching our family. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 8(Suppl 1):s152–s152.

- Bay J, Yaqona D, Oyamada M. 2019. DOHaD interventions: opportunities during adolescence and the periconceptional period. In: Sata F, Fukuoka H, Hanson M, editors, Pre-emptive medicine: public health aspects of developmental origins of health and disease. Singapore: Springer; p. 37–51. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-2194-8_3.

- Bay JL, Fohoko F, La'Akulu M, Leota O, Pulotu L, Tu'Ipuloto S, Tutoe S, Tovo O, Vekoso A, Pouvalu EH. 2016. Questioning in Tongan science classrooms: a pilot study to identify current practice, barriers and facilitators. Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching. 2(17):article 10.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. 1995. Statistics notes: multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ. 310:170. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170.

- Chaturvedi A, Zhu A, Gadela NV, Prabhakaran D, Jafar TH. 2024. Social determinants of health and disparities in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Hypertension. 81(3):387–399. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.123.21354.

- Chestnov O, Hilten MV, McIff C, Kulikov A. 2013. Rallying United Nations organizations in the fight against noncommunicable diseases. Bull World Health Organ, 91(9):623–623A.

- Cleverley T, Meredith I, Paotonu D, Gurney J. 2023. Cancer incidence, mortality and survival for Pacific peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand. The New Zealand Medical Journal. 136(1586):12–31. doi:10.26635/6965.6299.

- Epstein LH, Wrotniak BH. 2010. Future directions for pediatric obesity treatment. Obesity, (Md.). 18(Suppl 1):S8. doi:10.1038/oby.2009.425.

- Fink JW, Paine S-J, Gander PH, Harris RB, Purdie G. 2011. Changing response rates from Māori and non-Māori in national sleep health surveys. NZ Medical J. 124(1328):52–63.

- Gage H, Raats M, Williams P, Egan B, Jakobik V, Laitinen K, Martin-Bautista E, Schmid M, von Rosen-von Hoewel J, Campoy C. 2011. Developmental origins of health and disease: the views of first-time mothers in 5 European countries on the importance of nutritional influences in the first year of life. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 94(suppl_6):S2018–S2024. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.001255.

- Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. 2006. The developmental origins of health and disease: an overview. In: Hanson M, Gluckman P, editors. Developmental origins of health and disease. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; p. 1–5. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511544699.002.

- Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Low FM. 2011. The role of developmental plasticity and epigenetics in human health. Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews. 93(1):12–18. doi:10.1002/bdrc.20198.

- Grace M, Woods-Townsend K, Griffiths J, Godfrey K, Hanson M, Galloway I, Azaola MC, Harman K, Byrne J, Inskip H. 2012. Developing teenagers’ views on their health and the health of their future children. Health Education. 112(6):543–559. doi:10.1108/09654281211275890.

- Hanson Ma, Gluckman P. 2014. Early developmental conditioning of later health and disease: physiology or pathophysiology? Physiological Reviews. 94(4):1027–1076. doi:10.1152/physrev.00029.2013.

- Jeet G, Thakur JS, Prinja S, Singh M, Paika R, Kunjan K, Dhadwal P. 2018. Effectiveness of targeting the health promotion settings for non-communicable disease control in low/middle-income countries: systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 8(6):e014559. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014559.

- Jiang X. 2016. Nutrition in early life, epigenetics, and health. Epigenetics, the Environment, and Children’s Health Across Lifespans. 1:135–158. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25325-1_6.

- Kuruvilla S, Sadana R, Montesinos EV, Beard J, Vasdeki JF, de Carvalho IA, Thomas RB, Drisse M-NB, Daelmans B, Goodman T. 2018. A life-course approach to health: synergy with sustainable development goals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 96(1):42. doi:10.2471/BLT.17.198358.

- Lilo L, Tautolo E, Smith M. 2020. Health literacy, culture and Pacific peoples in Aotearoa, New Zealand: a review. Pacific Health. 3:3.

- Macnab A. 2013. The Stellenbosch consensus statement on health promoting schools. Global Health Promotion. 20(1):78–81. doi:10.1177/1757975912464252.

- Macnab AJ, Mukisa R. 2018. Priorities for African youth for engaging in DOHaD. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 9(1):15–19. doi:10.1017/S2040174417000423.

- Merriman TR, Wilcox PL. 2018. Cardio-metabolic disease genetic risk factors among Māori and Pacific Island people in Aotearoa New Zealand: current state of knowledge and future directions. Annals of Human Biology. 45(3):202–214. doi:10.1080/03014460.2018.1461929.

- Ministry of Health. 2017. Methodology report 2016/17: New Zealand health survey. Ministry of Health Wellington.

- Ministry of Health. 2021. New Zealand Health Survey. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/annual-update-key-results-2021-22-new-zealand-health-survey.

- Oyamada M, Lim A, Dixon R, Wall C, Bay J. 2018. Development of understanding of DOHaD concepts in students during undergraduate health professional programs in Japan and New Zealand. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 9(3):253–259. doi:10.1017/S2040174418000338.

- Satherley N, Milojev P, Greaves LM, Huang Y, Osborne D, Bulbulia J, Sibley CG. 2015. Demographic and psychological predictors of panel attrition: evidence from the New Zealand attitudes and values study. PLoS One. 10(3):e0121950. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121950.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2005. Statistical standard for ethnicity. Wellington, New Zealand: Statistics New Zealand.

- Stewart-Brown S. 2006. What is the evidence on school health promotion in improving health or preventing disease and, specifically, what is the effectiveness of the health promoting schools approach? World Health Organization, Health Evidence Network Report. 34:1–26.

- St Leger L, Young IM. 2009. Creating the document ‘Promoting health in schools: from evidence to action’. Global Health Promotion. 16(4):69–71. doi:10.1177/1757975909348138.

- Tang K-C, Nutbeam D, Aldinger C, St Leger L, Bundy D, Hoffmann AM, Yankah E, McCall D, Buijs G, Arnaout S. 2008. Schools for health, education and development: a call for action. Health Promotion International. 24(1):68–77. doi:10.1093/heapro/dan037.

- Tohi M, Bay JL, Tu’akoi S, Vickers MH. 2022. The developmental origins of health and disease: adolescence as a critical lifecourse period to break the transgenerational cycle of NCDs—a narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19(10):6024. doi:10.3390/ijerph19106024.

- Tohi M, Tu’akoi S, Vickers M. 2023. A systematic review exploring evidence for adolescent understanding of concepts related to the developmental origins of health and disease. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 14(6):755–762. doi:10.1017/S2040174423000442.

- Tu’akoi S, Vickers MH, Bay JL. 2020. DOHaD in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review exploring gaps in DOHaD population studies. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 11(6):557–563. doi:10.1017/S2040174420000276.

- Winter-Smith J, Selak V, Harwood M, Ameratunga S, Grey C. 2021. Cardiovascular disease and its management among Pacific people: a systematic review by ethnicity and place of birth. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 21:1–11. doi:10.1186/s12872-021-02313-x.

- Woods-Townsend K, Leat H, Bay J, Bagust L, Davey H, Lovelock D, Christodoulou A, Griffiths J, Grace M, Godfrey K. 2018. LifeLab Southampton: a programme to engage adolescents with DOHaD concepts as a tool for increasing health literacy in teenagers –a pilot cluster-randomized control trial. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 9(5):475–480. doi:10.1017/S2040174418000429.

- World Health Organization. 2018. Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/272603/9789241514064-eng.pdf.

- World Health Organization. 2021. World Health Statistics 2021: Monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/whs-2021_20may.pdf.