ABSTRACT

There is long-lasting horizontal and vertical segregation between female and male academics in technical fields in Finland. This article takes the lack of female academics as its starting point and focuses on a particular case in Finland: the merger of Tampere University of Technology (TUT) and the comprehensive University of Tampere (UTA), two universities which represented opposite ends in the proportion of female academics in Finland.

Interviews of female academics in technical fields in the newly merged university allow studying individuals’ gendered academic identity in the context of a changing organisational identification. Identity is chosen as the analytic tool to approach the interplay and disparities from organisational, disciplinary, and individual perspectives.

This research demonstrates the significance of gender for disciplinary and organisational identification in technical fields and in the context of a technical university. Taking a gender-neutral approach relates to identifying with technical disciplines and rejecting identification with the new comprehensive merger university. Whereas, with a gender sensitive approach, the new university may offer more possibilities for the female academics to identify with the organisation.

Introduction

There is a long-lasting disparity in the numbers of female and male academics in technical fields, which has been recognised both internationally (Shepherd Citation2017) and in Finland (Pietilä Citation2018). Despite gender equality policies, higher education fields are horizontally segregated in Finland, as in many Western countries, and there is vertical segregation in the academic profession: the share of female academics is particularly low in technical disciplines, and the higher the position, the fewer women there are (Benschop and Brouns Citation2003; Leišytė and Hosch-Dayican Citation2017; Silander et al. Citation2021).

Technical universities have been among the most male-dominated institutions in Finnish higher education.Footnote1 In 2017, 20%–30% of academics at Finland’s three technical universities were female, and the percentage of female professors ranged between 5% and 15%. At the same time, in comprehensive universities, close to 50% of academics were female, with the percentage of female professors ranging between 30% and 60% (Vipunen – Education Statistics Finland: https://vipunen.fi/en-gb/).

One technical university merged with a comprehensive university in 2019 to create a large multi-disciplinary university as part of the restructuring of Finland’s higher education sector. Before the merger, the two universities represented opposite ends of female academic representation. Large comprehensive universities tend to be more equal when examined on the organisational level, but the situation may differ on the disciplinary level.

One explanation for the low numbers of women in technical fields and technical universities may be disidentification with the discipline and organisation (Ahlqvist, London, and Rosenthal Citation2013). Identification is related to the compatibility of one’s own identity with contextual group identities. If one’s identity is compatible with group identities (as in a discipline or organisation), one may identify with the discipline and the organisation, but there may also be discrepancies in those identifications.

There is research on women in academic professions (Barnard et al. Citation2010; Lund Citation2015) and studies addressing why the number of women declines along the university career path (Elg and Jonnergård Citation2010; Hill, Corbett, and St. Rose Citation2010; Shepherd Citation2017). However, there is still little research across different disciplines (Musselin and Becquet Citation2008) or focusing on female academics’ identities in technical disciplines (Howe-Walsh et al. Citation2016).

This article focuses only on women’s identification and contributes to studies where women are in focus, without being compared to men’s views (Silander et al. Citation2021, 8). The present study makes women’s experiences in the technical university context visible and contributes to examining the intersection of academic, disciplinary and organisational identities and gendered practices and thus understanding the difficulty of change.

This research is also situated in the context of a university merger. Radical changes in organisations can significantly affect the identities of individual academics (Billot Citation2010, 709). Identification with the organisation predicts willingness to remain with the organisation and well-being at work (Billot Citation2010). My findings add to knowledge of the difficulties of retaining women in academia, especially technical disciplines.

Previous research concludes that academic careers are ‘linked to an institutional gender structure’ (Silander et al. Citation2021, 12), and the social construction of the ideal academic is implicitly male (Huopalainen and Satama Citation2019; Lund Citation2015). Culturally determined stereotypes of gender roles shape institutional arrangements, causing inequalities in academic career progression (Leišytė and Hosch-Dayican Citation2017, 474).

Technical universities are a specific organisational category with entrepreneurial characteristics and an industry orientation (Larsen, Geschwind, and Broström Citation2020). Technical universities may have a wider disciplinary offer, but generally focus on natural sciences, engineering and technology. Engineering and technology are based on a foundation of mathematics and physics but are orientated towards applications and solutions (Becher and Trowler Citation2001). Engineering can be viewed as a bridge between the natural sciences and societal applications (Pawley Citation2009, 314).

Science and academic work have been perceived as mainly masculine throughout history (Blickenstaff Citation2005; Huopalainen and Satama Citation2019). Despite the diversification and democratisation of access to higher education, engineering and natural sciences remain male-dominated. Gender has been identified as a detractive and directional aspect particularly in engineering identities (Hatmaker Citation2012; Morelock Citation2017). In disciplines associated with masculine traits, women as an underrepresented group may not feel they belong in the field and thus be less likely to persist in academic careers (Ahlqvist, London, and Rosenthal Citation2013; Seyranian et al. Citation2018; Wynn and Corell Citation2018).

In this article, identity is chosen as the analytic tool to examine individuals academic identity alignment with disciplinary and organisational identities (D’Andrea and Gossling Citation2005) and answer the research question:

How does gender affect identification with technical disciplines and the university as an organisation?

This study uses a practical, policy-oriented definition of gender equality whose aim is to increase the number of women in technical disciplines. Policy initiatives seek to foster women’s advancement in technology and science and attain equality, which is a value in itself but is also associated with quality, efficiency, enlarging the recruitment pool, and contributing to economic growth and innovation (Silander et al. Citation2021). This kind of policy can enforce an essentialist binary gender division and presuppose a binary gender distinction. Not all women face the same experiences, and the reasons behind their inequality are varied (Bell et al. Citation2019, 10). In addition, I acknowledge the diversity and fluidity of gendered identification and other intersecting differences that affect people’s identification.

Next, the analytical approach is summarised, after which the context and data and research method are presented. The main part of the article consists of the empirical results.

Analytical framework: academic identities

Individual identities are based on both distinctions and similarities between the self and others as well as a collective similarity of the self with others, which is manifested as group identity (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979). People may belong to several distinct or overlapping groups and have multiple identities that take different forms according to context (D’Andrea and Gosling Citation2005).

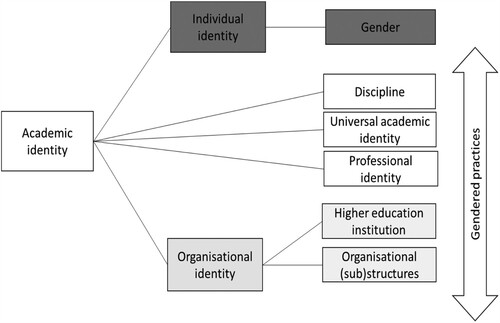

According to D’Andrea and Gosling (Citation2005, 59–60), academic identity may be based on three relevant aspects. First is individual identity, which may involve intersectional differences like gender ethnicity, class and age and personal values, ideologies, history and experiences. Second is organisational group identity, based on membership in an organisation such as a university and its sub-structures. Third is either a specific (sub)discipline or a professional identity typical of applied disciplines (like engineers) and the universal academic identity. The universal academic role has experienced changes as academics are no longer only researchers and teachers; they often fill managerial or other hybrid roles (Whitchurch Citation2008). This article focuses on the researcher identity because academic promotion still relies primarily on success in research (Leišytė and Hosch-Dayican Citation2017).

Some interviewees did identify themselves primarily as teachers, which can be seen as enforcing the gendered division of academic tasks, with teaching duties more commonly associated with women (Leišytė and Hosch-Dayican Citation2017; Silander et al. Citation2021). Leišytė and Hosch-Dayican (Citation2017) found that an enforced distinction between research- and teaching-oriented academics is likely to negatively affect the career prospects of female academics, particularly in mid-career (468).

In higher education, discipline has been considered a reference group that can transcend organisational boundaries and be central to the formation of individual academic identity. Disciplines have their own practices, discourses, ontology, values and culture (Becher and Trowler Citation2001). Identification with a discipline can be quite broad or limited to a certain specialisation (Becher and Trowler Citation2001; D’Andrea and Gosling Citation2005). Engineering and natural sciences are both dominated by male students and faculty and perceived as fostering culturally masculine norms (Wynn and Corell Citation2018). Women pursuing careers in these disciplines are exposed to several forms of social-identity threats: being a minority, lacking support, feeling excluded from networks and facing negative attitudes because of their gender (Blickenstaff Citation2005; Wynn and Corell Citation2018). Academia as an institution is gendered by processes, practices, structures, images and ideologies, and distributions of power historically dominated by men (Acker Citation1990; Henkel Citation2010; Lund Citation2015). There are cultural and institutional barriers to women’s academic recognition and promotion (Bagilhole and Goode Citation2001). Therefore, academia may be a hostile environment for women.

Individual identities affect academic identities even though they are often considered separate. The list of categories affecting academic identities is not exhaustive, as there may be other identity categories that can occur simultaneously or be in conflict with one another. Identities and their combinations may be unique, but they can also form a basis for collective identification such as ‘female academics’ (D’Andrea and Gosling Citation2005). depicts the aspects relevant for this study in a simplified format.

Figure 1. Analytical framework of this article adapted from D’Andrea and Gosling (Citation2005, 59–60); illustration by author.

This paper’s analytical focus is on whether female academics identify with technical disciplines, with the former technical university or with the new comprehensive university and on the relationship between these categories. Reproducing gendered practices is related to how individuals interpret the fit between organisational and disciplinary identification for women (Acker Citation1990). Contradictions between organisational identity, disciplinary identities and the individual identity can exist (Clarke et al. Citation2014).

Identity is not stable but shaped by multiple contexts; it can be ambiguous or even contradictory (Clarke et al. Citation2014), particularly when identities are difficult to reconcile (Henkel Citation2010). The reconstruction of identity may be involuntary when imposed by external changes. In university mergers, incompatible organisational and disciplinary identities may not survive in the new organisation or aspects of identity are affected by these changes (Puusa and Kekäle Citation2015).

Although gender is depicted here as only one aspect of individual identity, it is also present in academic and organisational identities, although they are ostensibly gender-neutral. Gendered practices in academia, disciplines and organisations reproduce gender on the individual level. In this research, the focus is on women and the reproduction of femininely gendered identities in the context of academia, technical disciplines and the technical university, but it this could also be seen as further emphasising the gendering of those identifying or identified as female and reinforcing the ‘neutrality’ and invisibility of male as the norm and thus these gendered practices.

Context

The context of the article is a voluntary but government-supported higher education merger. Twelve mergers of Finnish higher education institutions occurred between 2007 and 2020. This structural development can be seen as reflecting a European focus on increasing institutional competitiveness and economics of scale, with small, specialised universities transformed into larger comprehensive institutions. The changes are also linked to new university legislation that came into force in 2010; it allowed for more autonomy for institutions and led to changes in organisational form and the position of employees.

Data and methods

The research data consist of 13 thematic interviews with female academics who worked at the technical university before the merger and at the comprehensive university after it. The interviewees were recruited by an open call on the university intranet and took part voluntarily. Using an informed voluntary participation approach was considered highly important because the number of female academics in the technical disciplines is small. However, it may also cause volunteer bias, which needs to be considered in the analysis and results.

The interviewees represented all the faculties with technical disciplines in the merged university and different stages of the academic career (levels I–III);Footnote2 the focus was thus on early to mid-career stages (see Appendix 1 for a summary). When the interviews were conducted in 2021, all interviewees had at least five years of academic work experience.

To ensure anonymity, only the researcher knows the interviewees’ names; as little personal information as possible was collected from the interviewees. Preserving anonymity was also considered when selecting direct quotes. The interviewees did not know the researcher personally. However, the fact that the interviews were carried out by a female researcher may have created a more trusting environment in which female academics were able to disclose personal experiences.

The interviewees were asked to recount their academic careers and highlight instances when gender was relevant. They were also asked about their identification with the technical discipline and with the pre- and post-merger university. It was anticipated that the merger would affect organisational and disciplinary identifications (cf. Tienari, Aula, and Aarrevaara Citation2016) and that these changes would be reflected in academic identities when ‘values and identity trickle down’ through the organisation (Larsen, Geschwind, and Broström Citation2020, 5).

A theory-informed qualitative content analysis based on D’Andrea and Gossling’s (Citation2005) analytical framework was used. The keywords ‘academic,’ ‘researcher’, ‘discipline’, ‘university’ (or organisational sub-categories) and ‘gender’ were defined based on earlier research (cf. Bagilhole and Goode Citation2001; D’Andrea and Gosling Citation2005). These keywords were searched in the data, and the analysis continued by coding the larger context, defining categories, and linking them with larger themes. The manifest content in which the defined themes were explicitly discussed was first coded into categories; themes were formulated on various levels. The analysis expanded to interpretations of latent content, looking at patterns of both similarity and difference in the interview data (Graneheim, Lindgren, and Lundman Citation2017). The themes and categories identified in the data were again compared and reflected on in relation to the chosen theories and previous research (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). Particular attention was paid to identifications and disidentifications with the disciplines and organisations and instances where gender was relevant.

Results

The results are presented from individual identity to disciplinary and organisation identifications, with a focus on gendering and gendered practices.

This work is done with the brain – gender does not matter

According to the interviewees’ initial answers, gender is not an important identity category for them personally. Almost all started by saying that gender does not play a role in their academic identity or career experiences:

I have not had experiences related to gender, if that’s what you are looking for. … I think it has been very equal … and in the academic world I have advanced with my own merits and been able do things I’ve wanted. (Isabella)

Another interviewee summarised her view of the relation of gender and work: ‘I don’t think gender matters as this work is done with the brains’ (Bertha). Here, a biological (gendered) body is contrasted with the mind (brain); the importance of the latter is highlighted to undermine the gendered aspects often associated with women and their bodies (Huopalainen and Satama Citation2019). The women considered themselves equally capable in terms of academic work. The interviewees reacted to a biological nature identity and said that such essentialist ideas of women’s capabilities did not and should not exist in academia (cf. Barnard et al. Citation2010)

Gender did not seem to be the most valid frame of inquiry for interviewees to define themselves or their orientation towards others – a finding supported by previous research (Jorgenson Citation2002). This also relates to findings that women, even when aware of the masculine context in technical fields, often assert an individual rather than a gendered identity (Barnard et al. Citation2010).

However, some interviewees did highlight their gender and their pride at being able to succeed against the odds and being the exception in a male-dominated field:

Maybe it is about being proud that as a woman I am here, even though I said that I don’t really have a gendered perspective on things, but maybe it’s this feeling … of being a minority in technical fields and wanting to bring it forward that I’m from there. (Elena)

Despite this, the women did cite instances where gender had made a difference been imposed on them by others, thus recognising gendered practices. Other people in academia, industry or society had stereotypical views of engineers and those in technical disciplines as ‘not wearing skirts’ (Cecilia), ‘working in overalls or something’ (Fiona) or ‘as white men in collared shirts,’ (Hannah), and women broke those stereotypes by their mere existence.

One interviewee also said that what shielded her from experiencing conflict in her individual identity and how she is classified was her inability to be sensitive to gender aspects: ‘I’m quite a gender-neutral person myself, and I’m not very sensitive to realising when I’m being treated as a woman’ (Hannah).

Hannah was aware of breaking stereotypes of engineers and academics in technical fields simply by her gender, but as a weakly gender-identified woman, the stereotypes may be less relevant to her (Ahlqvist, London, and Rosenthal Citation2013; Degn Citation2019). However, this does not automatically prevent gendered practices from affecting her; she is gendered as a female academic through these practices despite her own identifications. As Miller (Citation2002, 155) writes, when women are ‘destabilising gender roles by acting “like men”, at some point the salience of the perception that they are women takes precedence’.

The incompatibility of gender identity with technical, disciplinary or organisational identity are perceived by some but not others, depending on the tendency to perceive a social identity threat (Ahlqvist, London, and Rosenthal Citation2013). To summarise, the ways in which the female academics positioned themselves in relation to gender often relied on the ideal of a gender-neutral (implicitly male) academia and downplaying the role of (implicitly female) individual gendered experiences. The women recognised that technical fields were considered male-dominated. When recognising these gendered stereotypes, the interviewees adopted the approach of succeeding against the odds; these women did see that technical fields were considered masculine, but they were able to master it and overcome the odds. Although they broke the gender stereotype, they did not challenge the ideal of the masculine technical academic as such.

I would want to see some female professor who has been able to do this – career and conflict with potential motherhood

Even though many interviewees denied the importance of gender in their academic careers and did not identify gendered practices in academia, they felt that the identity of ‘mother’ was imposed on them. There is constant interaction between internal self-definition and definition by others, who may affirm or deny an individual’s identity (Henkel Citation2010). These others may be members of an organisation following its (implicit) gendered practices or those imposing their personal views on the gendered aspects of academic and disciplinary identities in technical universities. One female academic resisted this imposed gendered identity: ‘I don’t want to associate women only with family. It really annoys me as a discourse that we are always reduced to motherhood’ (Hannah). The reduction of women to motherhood is extremely problematic; it automatically genders academic careers, with parenthood mainly associated with women and negatively viewed in terms of their careers (Huopalainen and Satama Citation2019, 102).

Many interviewees cited organisational and academic practices that disadvantaged women who had children, such as career breaks affecting evaluation of research merit, expectations that researchers would travel for work or move abroad for an extended period, along with the expectation to work more than regular hours. It seems that gendered practices related to motherhood were easier to identify and define than other organisational gendered practices. The interviewees attested that most of the aspects mentioned would apply to all academic careers but were heightened in technical fields. They speculated that the low number of women enabled retaining these implicitly male-favouring practices and wondered how they were resolved in other academic fields. This is in line with previous findings on the importance of critical mass: ‘a long-term change in numbers may be the only way to change institutionalised, gendered practice’ (Elg and Jonnergård Citation2010, 222). In addition, the gendered practices of academia and technical disciplines may add a ‘layering of multiple masculinities’ (cf. Miller Citation2002, 145). The interviewees discussed the existence of gendered practices as immutable (Acker Citation1990):

Even some professors at post-graduate events said something like ‘this [academic work and mobility] is easy for men as the wife can come along to take care of the children, but for women this is harder’, and so it is. (Cecilia)

However, some interviewees said that motherhood did hinder women’s career prospects but having children was a choice for which one cannot expect to receive compensation:

It’s clear that if you have children and stay at home with them, like one year per child, then you are one year less at work. So, it will definitely affect progress in your career a lot’. (Gabriella)

Theories suggest that family responsibilities and the challenges of combining work and family might be one reason for women opting out of academia (Stack Citation2004). Similarly, the interviewees said that successful women either have no children or caring responsibilities or advance in their career when their children are older. They also mentioned exceptional ‘superwomen’ who managed to have both an academic career and children. However, many cited a lack of female role models, especially those who had combined career and family, in higher academic positions:

I would want to see some female professor who has been able to do this so that she would have only worked eight hours a day or that she has been able to spend time with her kids’. (Cecilia)

Previous research (Nikunen Citation2014) has demonstrated that even women without children are seen as being on the ‘mommy track’ because they are potential mothers and caretakers in both the family and the workplace. This view was offered by younger interviewees who had been warned about the effects of motherhood on their careers even before they felt it was timely or if they were uncertain if they wanted to have children:

It was an assistant professor I think who said to me that he felt sorry that it’s so hard for women in academia when you have children and so on, and I had just started work and I was something like 21’. (Danielle)

I’m not one of those researchers – on the ideal academic

The interviewees recognised the academic as an identity category with certain (gendered) aspects within the university. Several interviewees had difficulties self-identifying as academics, as they associated the characteristics of passion, commitment, ingenuity and calling with the academic identity (Benschop and Brouns Citation2003; Lund Citation2015) and not with themselves. They contrasted themselves with the academic:

I’m not one of those researchers who lives and breathes their work. I just somehow ended up as a doctoral researcher and here I am, but I’m not someone who thinks about their research day and night and is totally on fire about these things’. (Gabriella)

Working full weeks and weekends; maybe not having even summer vacation and working all nights and so on. That’s why I have been so uncertain whether to continue this career, and I’m still not sure’. (Cecilia)

Identity may be based on an individual’s accomplishments and seemingly gender-neutral academic merits, although technical disciplines and merit are inherently masculine (Elg and Jonnergård Citation2010; Nikunen Citation2014; Pietilä Citation2018), the interviewees did not question the gender neutrality of the meritocratic university but enforced it:

There are quite clear criteria for salary and advancement in the career. That’s what I have liked at the university: that there are quite objective criteria for the demand level of the position … they are transparent in that way’. (Isabella)

Interviewees, whether recognising the gendered practices (gender-sensitive) or not (gender-neutral), generally considered academic merit to be neutral. Some did say that there might be (implicit) bias in evaluating merit or that women needed to prove their skills more than men. The existence of bias in the evaluation processes has been demonstrated in research showing that both women and men may have the same kind of bias favouring male candidates (Hill, Corbett, and St. Rose Citation2010).

To conclude, the ideal academic is presented as wholly devoted to research, gender-neutral but implicitly male. This ideal is difficult to combine with family and caretaking responsibilities that are associated with women in the gendered academic culture. Women doubt both their capabilities and commitment to the academic ideal.

I don’t feel that I’m purely a natural scientist or purely an engineering academic

In higher education research, discipline is often considered the most important aspect of identity and was therefore expected to be a powerful point of identification for the interviewees. Many interviewees did identify with their (sub)discipline, but several also proclaimed broader technical identities. Somewhat surprisingly, identification with discipline was not straightforward and differed between interviewees. Anna said, ‘I don’t feel that I’m purely a natural scientist or purely an engineering academic … but quite a mix of everything that I have studied and researched’.

There is fluidity within the technical disciplines and a cross-discipline approach that allows for more general identification. Almost all interviewees had a technical identity based on a discipline or more general technical fields, with the latter aligned with an identification with the technical university. Thus, disciplinary identity was linked with organisational identification.

Some interviewees did not see the status quo changing through the merger, but the technical disciplines maintained their own disciplinary identity in the new university, suggesting that they formed a separate subculture: ‘technical disciplines in the new university are still their own’ (Hannah). In addition, the difference between the technical disciplines and other comprehensive university field was stressed:

The problem of this new university is that some fields have such different ontological approaches than technical fields … and when people have such different viewpoints, it creates a lot of problems’. (Jessica)

Based on previous research (Barnard et al. Citation2010; Elg and Jonnergård Citation2010; Shepherd Citation2017), a tensioned gendered identification with technical disciplines may be expected. The incompatibility of identity categories is highlighted when academic faculty construct academic identities and discover that they need to suppress aspects of their individual identity, such as gender or social class, to fit into the university environment (Archer Citation2008). Gender can thus be regarded as both constituting a gendered identity and resulting in problems of identifying when that aspect is not compatible with other key aspects of academic, disciplinary or organisational identities.

It’s like a family – on research group identification

Some had a smaller reference group for identification – the research group – that did not necessarily conflict with disciplinary or organisational identifications but often came with the explanation of an exceptional research group leader: ‘I have really gotten a lot of support and information like on what kind of possibilities there are, and when to finalise the doctoral degree’ (Danielle). The research group was described by one interviewee in familial terms:

I think it is like a family that you identify with and kind of all the structures around have been shaking and changing … but it has been the permanent structure that I have been able to identify with – the research group’. (Bertha)

Organisational practices could undermine the positive experiences in the research group. Establishing a research group of one’s own was challenging either because of lack of organisational support and difficulties in combining it with family life:

The members of our research group proposed me as the group leader. … I had the support of the group, but then the head of the unit, who is a senior male, asked them to name someone who had more merit, someone more senior. … I felt this was a case where the academic career of a young woman was not supported … I’m not sure if it was a gender or an age issue or what. (Bertha)

The next phase is to establish your own research group. At that stage, it’s really difficult to say to your three doctoral students that you will be on maternity leave for a year. I think these structures should be brought into the discussion. (Isabella)

In practice, I have had to build all this by myself: acquired funding for the whole research group so that I have had from five to 15 researchers hired. It has maybe been mentioned in ceremonial speeches at the university, but there is not really concrete support for my group. (Mariah)

New organisational and disciplinary identity in conflict – keeping with the technical identity or rejecting it?

Previous research on mergers between technical and comprehensive universities reveals that their organisational identities differ significantly (Cremonini, Mehari, and Adamu Citation2019; Vellamo, Pekkola, and Siekkinen Citation2019). Some interviewees identified with the technical university or the campus where technical disciplines are situated, which becomes a surrogate for organisational identification:

I don’t feel I belong to the faculty at all, because we are here in the campus of the technical disciplines … and we feel we are more technical disciplines and part of the community which was here on this campus. (Elena)

The work and the close working environment have remained exactly the same, but still the identification you asked about, it has been difficult. It’s because I feel that the technical identity has somehow disappeared in the new university to the outside world. Maybe not our internal identity: it still is what it is, but to the outside. (Isabella)

According to the interviewees, the new organisation has also enforced the idea of gender being important, especially among those who claimed that gender had no relevance in their work or career. The coping tactics of not recognising gendered organisational practices was undermined by this change: ‘suddenly it matters whether you are a man or a woman when earlier [at the technical university] it didn’t; at least that’s how I felt it’. (Gabriella)

This may be a reaction to the new university culture, where gender is brought into the discussion and (former) gendered practices have become visible. If a female academic identified strongly with technical fields and the former technical university, this often required a personal identity position where gender was irrelevant and the organisation’s gendered practices were not recognised. Those who felt that gender was irrelevant also felt uneasy with the new organisation emphasising equality and bringing up the view that women are treated differently than men. They may be unwilling to take a position that they feel victimises them or jeopardises their technical identity. This was also associated with the positive aspects linked with the technical university which do not fit in the new organisation. The next quote highlights the entrepreneurial quality of the technical university:

I don’t quite fit the model [of the new university], and entrepreneurial activities are not encouraged: things like following one’s own path. I think these were supported during the technical university times. (Bertha)

Those female academics who experienced trouble in identifying with the technical disciplines and technical university often had more multidisciplinary and diversified backgrounds. The interviewees who distanced themselves from the values and culture of the technical disciplines and the technical university were able to challenge more openly the masculinity of technical disciplines and the technical university organisation. Some detached themselves from the technical fields and ‘outdated’ practices and views, referring to the ‘stuffy culture’ in technical disciplines. For them, the new university might offer more equality and opportunities by providing examples from other fields and more open and transparent practices:

We are in a multidisciplinary larger university so maybe that influences the discussion culture. Diversity is coming more forcefully into technical fields; it affects technical fields, so we have to think more about what our diversity looks or doesn’t look like. (Hannah)

I feel better in this new merged university. I was never part of the technical culture. When I started my studies … the culture was quite stuffy … it did not represent my values and I didn’t want to participate in it. (Karen)

These interviewees also reflected upon whether the new university might be more gender-equal and inclusive. They did not take this for granted but were optimistic:

[The merger] is an opportunity for genuinely hearing what the employees have to say and taking the university as a whole in that direction. It’s important to be critical, but then again you can also be optimistic and hopeful. (Karen)

Change is a possibility, but it takes something more than just change. People who seek new ways of doing things are needed. (Lena)

Discussion

Based on previous research (Becher and Trowler Citation2001), the expectation was that discipline would be a strong aspect of identification, but it turned out to be less important than identification with the research group or a more general identification with technical fields or the technical university. This result was somewhat surprising as the context of the research group is not mentioned in other studies or its relation to disciplinary or organisational identity and identification. Previous research has not discussed the importance of the research group as a supportive structure for female academics. It is not certain whether this is a gendered aspect of identification or whether women feel a closer connection with research groups than men.

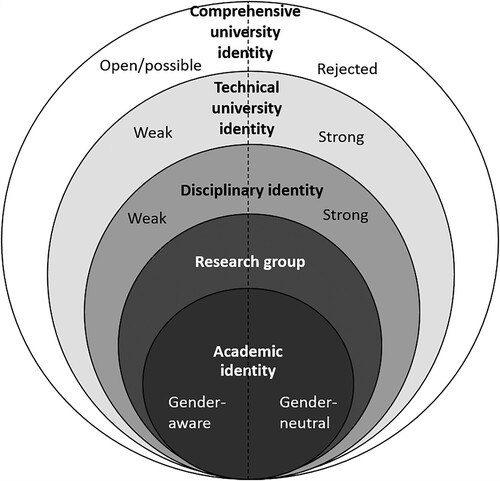

Based on the interview findings, the possible identifications are summarised in .

Figure 2. How gendered identity affects identification with academic and organisational identity (inspired by Välimaa Citation1998, 132).

The two sides of the figure represent the dichotomy of the identifications for female academics in technical fields in the merger context. The role of gender is significant in directing the identification with both discipline and organisation. Adopting a gender-neutral approach and ignoring gendered (disciplinary and organisational) practices enable identification with technical fields. Previous studies have provided somewhat similar results on the relation between gender and technical disciplines (Ahlqvist, London, and Rosenthal Citation2013; Barnard et al. Citation2010; Jorgenson Citation2002), supporting the view that assimilation in technical disciplines requires disqualifying femininity, which can be done by claiming that ‘it is not about gender’. In this kind of assimilation strategy, there is a lack of awareness of the masculine nature of the context (Miller Citation2002, 157).

Many interviewees referred to equality of opportunities in academia and technical disciplines, thus adopting gender-neutral perceptions of merit. In a prototypically masculine field, women are disadvantaged in their position based on their gender and must employ adaptive responses. They must assimilate to succeed, leave if they cannot adapt or remain with a risk of becoming isolated and excluded (Bagilhole and Goode Citation2001; Barnard et al. Citation2010). All these responses were present in the interview data. In addition to the female academics’ personal experience, these ‘adaptation strategies reinforce the masculine value system resulting in short term, individual success, and long-term failure for gender change’ (Miller Citation2002, 145).

The right side of shows that a gender-neutral approach allows for a stronger disciplinary identification with technical fields and organisational identification with the former technical university. In this view, the organisation’s and discipline’s gendered practices are not recognised. On the left side, a gender-sensitive approach makes it more difficult to identify with the discipline and the former technical university, and gendered practices in the organisation and discipline are (to some extent) recognised. In addition, identification with the new university is seen as possible. This is in line with the discovery that difficulties in defining an academic identity within a discipline could also hinder identification with the linked organisation (Degn Citation2019) if technical disciplines are seen as aligned with the technical university. Such strong identification with the organisation may be a trait specific to technical universities; in comprehensive universities, disciplinary identification may be stronger and transcend organisational ties.

This study has offered insights into the strong institutional-level identification with the technical university in the context of the merger. Those who strongly identified with technical disciplines and the former university were most sceptical about the merger-related changes relative to their academic careers and rejected the new university identity.

Recognising gendered aspects in the interviewees’ academic identification was linked to feeling alienation or being marginalised in the technical university organisation and technical disciplines. This disidentification with disciplinary and organisational identities could be further enhanced by the gendered practices of a discipline and organisation: the ‘layering of multiple masculinities’ (Miller Citation2002).

Some interviewees acknowledged the need to address equality and the existing gendered practices in the organisation but were uncertain how to do so. The new university may appear as more identifiable and inclusive from the gender perspective and could contribute to equality by establishing new practices, enabling more discussion and employing benchmarking with other disciplines, although there is still a long way to go before a strong identification with the new university, even for those who distanced themselves from technical fields. Organisational identity work on what the new university stands for and whom it represents and includes can either mute or amplify the significance of gender in relation to other dimensions (Puusa and Kekäle Citation2015).

It remains uncertain whether gender segregation will be alleviated in technical fields as they are incorporated into the comprehensive university and how (new) gendered practices will develop in the new university. The interviewees also identified aspects that might hinder positive development, as emphasising gender may cause a backlash in technical fields. The new comprehensive university might also threaten technical identities and even annihilate their positive aspects.

Conclusion

This article sought to answer the question, ‘How does gender affect identification with technical disciplines and the university as an organisation?’ The focus was on the experiences of female academics. The findings are based on a theory-informed content analysis of data from interviews with 13 female academics in technical fields. The main results are as follows:

Identifying strongly with a technical discipline entails disavowing the gendered experience in academia and is related to retaining the technical university identity and rejecting the new university identity.

Recognising the significance of gender and distancing oneself from technical disciplines allow for a more open approach to the new university and the possibilities and identifications it may offer.

Using gender as an analytic category poses the risk of reducing differences between women and reproducing gender dichotomies. This article does not address any other differences that might intersect with gender. Examining such other intersectional differences could be a valuable avenue for future research.

Gendered practices lead to treating women and men differently while reproducing gender. Generally, a gender-neutral approach is also associated with reproducing segregation and differences between men and women without acknowledging the gendered practices within a discipline and organisation. It is important to recognise the practices and beliefs that enforce segregation and inequality, as they are often hidden behind seemingly neutral organisational practices. These also affect the identification of female academics with both discipline and organisation.

An additional and unexpected finding was the importance of the research group for female academics’ identification. Research groups appeared to provide valuable support that the institution did not. This gendered perspective on research group support should be investigated in greater depth.

As to limitations, this study involved a specific context and a rather small number of interviewees. This was partially due to the limited number of potential interviewees (about 100). Including other Finnish technical universities in a future study would offer a wider perspective. Additionally, a quantitative survey on identifications with discipline and organisation from a gendered perspective would enable probing the links between technical disciplines and identifications from larger data.

Examining the same university several more years after the merger would allow for a longitudinal perspective on changes, analysing identifications and whether the new university is better able to attract female academics and retain them in academic careers.

From the practical point of view, the technical disciplines need to be involved in preparing organisational equality plans and setting goals to develop more inclusive practices in the new university. In addition, the positive aspects of long-standing technical identities should be maintained in the new organisational identity.

Biographical note

M.A. M.Sc. (Admin) Tea Vellamo is a Doctoral Researcher finalising her PhD dissertation on technical identities in a university merger at the Faculty of Management and Business, Tampere University. She has worked both at the former University of Tampere and the Tampere University of Technology. Her research interest include internationalisation, organisational identity, gender studies and higher education policy and governance.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Jussi Kivistö and University Lecturer Elias Pekkola from Tampere University for their constructive comments on the article.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, study participants did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 There were three technical universities in Finland before 2019. In 2022, there are only two technical universities, but a total of eight universities offer a Master of Science degree (https://dia.fi/haluan-diplomi-insinooriksi/, accessed July 7, 2022).

2 Finland’s Ministry of Education and Culture introduced a four-tier career model to increase the comparability of academic careers between institutions. Typical positions in each career stage are doctoral student (stage I), postdoctoral researcher, assistant professor (stage II), senior research fellow, associate professor (stage III) and (full) professor (stage IV).

References

- Acker, J. 1990. “Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations.” Gender & Society 4 (2): 139–158. doi:10.1177/089124390004002002.

- Ahlqvist, S., B. London, and L. Rosenthal. 2013. “Unstable Identity Compatibility: How Gender Rejection Sensitivity Undermines the Success of Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Fields.” Psychological Science 24 (9): 1644–1652. doi:10.1177/0956797613476048.

- Archer, L. 2008. “Younger Academics’ Constructions of ‘Authenticity,’ ‘Success,’ and Professional Identity.” Studies in Higher Education 33 (4): 385–403. doi:10.1080/03075070802211729.

- Bagilhole, B., and J. Goode. 2001. “The Contradiction of the Myth of Individual Merit, and the Reality of a Patriarchal Support System in Academic Careers: A Feminist Investigation.” European Journal of Women's Studies 8 (2): 161–180. doi:10.1177/135050680100800203.

- Barnard, S., A. Powell, B. Bagilhole, and A. Dainty. 2010. “Researching UK Women Professionals in SET: A Critical Review of Current Approaches.” International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology 2 (3): 65. https://genderandset.open.ac.uk/index.php/genderandset/article/view/65.

- Becher, T., and P. R. Trowler. 2001. Academic Tribes and Territories: Intellectual Enquiry and the Culture of Disciplines. 2nd ed. London: Society for Research into Higher Education.

- Bell, E., S. Meriläinen, S. Taylor, and J. Tienari. 2019. “Time’s Up! Feminist Theory and Activism Meets Organization Studies.” Human Relations 72 (1): 4–22. doi:10.1177/0018726718790067.

- Benschop, Y., and M. Brouns. 2003. “Crumbling Ivory Towers: Academic Organizing and its Gender Effects, Gender, Work and Organization 10: 194–212. doi:10.1111/1468-0432.t01-1-00011.

- Billot, J. 2010. “The Imagined and the Real: Identifying the Tensions for Academic Identity.” Higher Education Research & Development 29 (6): 709–721. doi:10.1080/07294360.2010.487201.

- Blickenstaff, J. C. 2005. “Women and Science Careers: Leaky Pipeline or Gender Filter?” Gender and Education 17 (4): 369–386. doi:10.1080/09540250500145072.

- Clarke, M., J. Drennan, A. Hyde, and Y. Politis. 2014. “Academics’ Perceptions of Their Professional Contexts.” In Academic Careers in Europe: Trends, Challenges, Perspectives, edited by T. Fumasoli, G. Goastellec, and B. Kehm, 117–131. Cham: Springer.

- Cremonini, L., Y. Mehari, and A. Y. Adamu. 2019. “University Mergers in Finland.” In Mergers in Higher Education: Practices and Policies, edited by L. Cremonini, S. Paivandi, and K. M. Joshi, 289–306. Delhi: Studera Press.

- D’Andrea, V., and D. Gosling. 2005. Improving Teaching and Learning: A Whole Institutional Approach. New York: Open University Press.

- Degn, L. 2019. “Investigating Organisational Identity in HEIs.” In The Three Cs of Higher Education: Competition, Collaboration and Complementarity, edited by R. M. O. Pritchard, M. O’Hara, C. Milsom, J. Williams, and L. Matei, 51–69. Budapest: Central European University Press.

- Elg, U., and K. Jonnergård. 2010. “Included or Excluded? The Dual Influences of the Organisational Field and Organisational Practices on New Female Academics.” Gender and Education 22 (2): 209–225. doi:10.1080/09540250903283447.

- Graneheim, U. H., B. M. Lindgren, and B. Lundman. 2017. “Methodological Challenges in Qualitative Content Analysis: A Discussion Paper.” Nurse Education Today 56: 29–34. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002.

- Hatmaker, D. M. 2012. “Practicing Engineers: Professional Identity Construction Through Role Configuration.” Engineering Studies 4 (2): 121–144. doi:10.1080/19378629.2012.683793.

- Henkel, M. 2010. “Introduction: Change and Continuity in Academic and Professional Identities.” In Academic and Professional Identities in Higher Education: The Challenges of a Diversifying Workforce, edited by G. Gordon, and C. Whitchurch, 3–12. New York: Routledge.

- Hill, C., C. Corbett, and A. St. Rose. 2010. Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Washington, DC: American Association of University Women.

- Howe-Walsh, L., S. Turnbull, E. Papavasileiou, and N. Bozionelos. 2016. “The Influence of Motherhood on STEM Women Academics’ Perceptions of Organizational Support, Mentoring and Networking.” Advancing Women in Leadership Journal 36: 54–63. doi:10.21423/awlj-v36.a21.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Huopalainen, A. S., and S. T. Satama. 2019. “Mothers and Researchers in the Making: Negotiating ‘New’ Motherhood Within the ‘New’ Academia.” Human Relations 72 (1): 98–121. doi:10.1177/0018726718764571.

- Jorgenson, J. 2002. “Engineering Selves: Negotiating Gender and Identity in Technical Work.” Management Communication Quarterly 15 (3): 350–380. doi:10.1177/0893318902153002.

- Larsen, K., L. Geschwind, and A. Broström. 2020. “Organisational Identities, Boundaries, and Change Processes of Technical Universities.” In Technical Universities: Past, Present and Future, edited by L. Geschwind, A. Broström, and K. Larsen, 1–14. Cham: Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007978-3-030-50555-4_1.

- Leišytė, L., and B. Hosch-Dayican. 2017. “Gender and Academic Work at a Dutch University.” In The Changing Role of Women in Higher Education edited by H. Eggins, 95–117. Cham: Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007978-3-319-42436-1_5.

- Lund, R. 2015. Doing the Ideal Academic: Gender, Excellence and Changing Academia.” PhD diss., Aalto University.

- Miller, G. 2002. “The Frontier, Entrepreneurialism, and Engineers: Women Coping with a Web of Masculinities in an Organizational Culture.” Culture and Organization 8 (2): 145–160. doi:10.1080/14759550212836.

- Morelock, J. R. 2017. “A Systematic Literature Review of Engineering Identity: Definitions, Factors, and Interventions Affecting Development and Means of Measurement.” European Journal of Engineering Education 42 (6): 1240–1262. doi:10.1080/03043797.2017.1287664.

- Musselin, C., and V. Becquet. 2008. “Academic Work and Academic Identities: A Comparison Between Four Disciplines.” In Cultural Perspectives on Higher Education, edited by J. Välimaa and O.-H. Ylijoki, 91–107. Dordrecht: Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007978-1-4020-6604-7_7.

- Nikunen, M. 2014. “The ‘Entrepreneurial University,’ Family and Gender: Changes and Demands Faced by Fixed-Term Workers.” Gender and Education 26 (2): 119–134. doi:10.1080/09540253.2014.888402.

- Pawley, A. L. 2009. “Universalized Narratives: Patterns in How Faculty Members Define “Engineering”.” Journal of Engineering Education 98 (4): 309–319.

- Pietilä, M. S. 2018. Making Finnish Universities Complete Organisations: Aims and Tensions in Establishing Tenure Track and Research Profiles.” PhD diss., University of Helsinki.

- Puusa, A., and J. Kekäle. 2015. “Feelings over Facts: A University Merger Brings Organisational Identity to the Forefront.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 37 (4): 432–446. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2015.1056602.

- Seyranian, V., A. Madva, N. Duong, N. Abramzon, Y. Tibbetts, and J. M. Harackiewicz. 2018. “The Longitudinal Effects of STEM Identity and Gender on Flourishing and Achievement in College Physics.” International Journal of STEM Education 5: 40. doi:10.1186/s40594-018-0137-0.

- Shepherd, S. 2017. “Why Are There so Few Female Leaders in Higher Education: A Case of Structure or Agency?” Management in Education 31 (2): 82–87. doi:10.1177/0892020617696631.

- Silander, C., U. Haake, L. Lindberg, and U. Riis. 2021. “Nordic Research on Gender Equality in Academic Careers: A Literature Review.” European Journal of Higher Education 12 (1): 72–97. doi:10.1080/21568235.2021.1895858.

- Stack, S. 2004. “Gender, Children and Research Productivity.” Research in Higher Education 45: 891–920. doi:10.1007/s11162-004-5953-z.

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Inter-Group Conflict.” In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by W. G. Austin, and S. Worchel, 7–24. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

- Tienari, J., H. M. Aula, and T. Aarrevaara. 2016. “Built to Be Excellent? The Aalto University Merger in Finland.” European Journal of Higher Education 6 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1080/21568235.2015.1099454.

- Ursin, J. 2004. Characteristics of Finnish Medical and Engineering Research Group Work.” PhD diss., University of Jyväskylä.

- Vabø, A., A. Alvsvåg, S. Kyvik, and I. Reymert. 2016. “The Establishment of Formal Research Groups in Higher Education Institutions.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 2016 (2–3): 33896. doi:10.3402/nstep.v2.33896.

- Välimaa, J. 1998. “Culture and Identity in Higher Education Research.” Higher Education 36 (2): 119–138.

- Vellamo, T., E. Pekkola, and T. Siekkinen. 2019. “Technical Education in Jeopardy? – Assessing the Interdisciplinary Faculty Structure in a University Merger.” In The Responsible University: Exploring the Nordic Context and Beyond, edited by M. P. Sørensen, L. Geschwind, J. Kekäle, and R. Pinheiro, 203–232. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vipunen – Education Statistics Finland: https://vipunen.fi/en-gb/

- Whitchurch, C. 2008. “Shifting Identities and Blurring Boundaries: The Emergence of Third Space Professionals in UK Higher Education.” Higher Education Quarterly 62 (4): 377–396. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00387.x.

- Wynn, A. T., and S. J. Correll. 2018. “Puncturing the Pipeline: Do Technology Companies Alienate Women in Recruiting Sessions?” Social Studies of Science 48 (1): 149–164. doi:10.1177/0306312718756766.