ABSTRACT

This paper contributes to current discussions of digital teaching and technology within the field of engineering design education. We enter this dialogue by analysing a hybrid digital learning design for a 15-ECTS engineering design course. The course design pedagogically integrates principles from networked learning research, Problem-Based learning (PBL), as well as established pedagogical traditions. Specifically, we analyse and discuss the case based on four pedagogical principles underpinning the course: structured freedom, flipped engagement, hybridity, and transparency. The purpose of our discussions is to understand and contribute knowledge of digitalising engineering design education. Specifically, our pedagogical approach to hybrid and digital modes of learning rethink and expand the integration of digital technologies in physical design studios in a PBL context by employing networked learning principles. Following this, we draw out interesting contributions that have emerged and use the discussions to feed into the ongoing research on digitalising engineering design education.

Introduction

In engineering design education, there is a long tradition of learning through practice-based design projects. Over the years design engineering institutions have developed a pedagogical framework, which builds on in-situ, studio-based project activities that are practical (and somewhat unstructured) to facilitate integrative learning-by-doing (Lawson Citation2019). A core purpose for many design engineering programmes is to develop designers’ methodological competencies (Laursen and Tollestrup Citation2017), such as reflective practice (Adams, Turns, and Atman Citation2003; Ellmers and Foley Citation2020; Schön, Citation1983), dialogue with the situation (Ge, Leifer, and Shui Citation2021), and co-development of problem and solution (Dorst and Cross Citation2001; Lotz et al. Citation2015). For this purpose, teaching design engineering in higher education has developed into a distinct pedagogy which characteristically is based in a physical studio to support the practical, hands-on, integrative, and reflective activities that drive critical learning (Lawson and Dorst Citation2013).

The physical studio has particularly been studied as an enabler that unifies many social and cultural learning elements (Lawson, Citation2019). The design studio setting is a characteristic pedagogy in design education, as it in many ways mimics real design practice (Crowther Citation2015). It is a physical space that can be either private or public, where students work on projects individually or in groups. It facilitates a learning-by-doing approach, puts informal structures in an unrestricted timetable, and enables a cross-domain integrative approach (Lawson and Dorst Citation2013). The studio is therefore central to the educational framework of design engineering education, as it embodies design as a cognitive and experience-based discipline, as well as a community of practice that builds on the methodological approaches of the design engineering domain. For example, the studio has been analysed as a site where students develop a ‘professional dialogic practice’ in architecture and design education (Davidsen, Ryberg, and Bernhard Citation2020).

However, the global COVID-19 pandemic forced higher education institutions and Engineering Design programmes all over the world to abruptly switch to online education. This even occurred in programmes that traditionally have been heavily reliant on physical spaces, such as the design studio. The crisis, therefore, has pushed educators to adapt and integrate digital technologies to substitute or augment core and foundational educational elements in design engineering education, such as studio project work, critique sessions, exemplar libraries, and tutoring (Lawson and Dorst Citation2013). This radical shift and implementation of online digital learning in design engineering education may be a turning point for the pedagogical tradition within design engineering education. Rather than returning to ‘business as usual’ in a post-pandemic future, we are at a point where we can begin to address central challenges in relation to rethinking digital pedagogical practices for design engineering education.

As COVID-19 has pushed digitalisation to be implemented across all educational activities, this ‘experiment’ from a research perspective provides a window of opportunity where we need to discuss and reflect upon the way forward for design engineering education. We argue there is a third way, moving beyond the historic physical presence in studios and the recent ‘COVID-19’ fully online education.

It is worth noting that research and development have already investigated studios in virtual settings. Virtual design studios (VDS) are an approach to learning where students’ communication and collaboration mainly are carried out through asynchronous digital means to overcome spatial barriers, such as time and geography (Rodriguez et al., Citation2018). This is opposed to how core parts of the learning design traditionally are based on the social and cultural features of the physical studio, such as co-location, learning-by-doing, unrestricted timetable, integration, and mimicking practice. VDS uses interactive technologies such as Microsoft Teams, Skype, Zoom and Facebook to enable design students to communicate with, peers, supervisors, and lecturers. Moreover, such technologies allow students to carry out classes individually at any time and place (Meshur, Alkan, and Bala Citation2014). Scholars have shown how VDS may move away from linear and one-directional learning modes towards spatial flexibility, which may enable more independence, motivation, and a broader diversity of social interactions (Kramer et al. Citation2015). However, scholars have also raised concerns that VDS may limit student engagement, as when provided with too much freedom, students may not be able to regulate interaction and engage in learning (Sun and Rueda Citation2012). Also, there may be more barriers to collaboration with peers and feedback and support from lectures (Tuckman Citation2007). Further, studies of VDS argue we need to design for more passive learning behaviours, such as listening in, which is identified as important in a design studio setting (Cennamo and Brandt Citation2012; Jones, Lotz, and Holden Citation2021).

In the paper, we present an example of a ‘fully online’ design course which was crafted to meet the challenge of how to deliver a previously studio-anchored physical course in a fully online mode. The course we explore is titled ‘Introduction to the industrial design-engineers design, terminology, process, and methodology,’. It is a 15-ECTS course in the second semester of the Architecture and Design bachelor’s programme in Denmark based on a Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model.

We position the course as a good or ‘best practice’ example of a conversion from onsite to online teaching while also recognising that the course was well-sourced and thrived on strong institutional support. However, the main point of the paper is not only to present a ‘good example’ and the underlying pedagogical principles; rather, we use the course as a springboard to discuss the future direction of courses in a post-COVID world. We position the course, its design, and its principles as a window of opportunity to begin discussing the future of engineering and design education. In the return to a ‘normal’ situation within education, what are the lessons we can learn from the COVID-19 period in terms of the future design of courses within an onsite/physical context?

The research question guiding the paper, therefore, is: How can we use experiences from COVID-19 to rethink and expand the integration of digital technologies in physical design studios within a PBL context through employing networked learning principles? While much of engineering design education research deals with new technologies, this paper leads us into a pedagogical-based discussion on how we may integrate new technologies in engineering design education to enable elements of structured freedom, flipped engagement, hybridity, and transparency.

Paper outline

We begin the paper by presenting the background of the study. Then we present the pedagogical ideas underpinning the course. These are explored through four principles derived from Networked Learning and PBL (structured freedom, flipped engagement, hybridity, and transparency), which we apply as a lens to re-interpret the role of the physical studio for an online format. The four pedagogical principles emerged through the two authors’ discussions of the course and its design, the data collected, as well as theory. We then present the course’s design and the various resources (teaching notebooks, road maps, theory pages, worksheets) that were developed to support the students’ project work and scaffold their design process in the absence of a physical studio. This includes the digital tools, resources, and infrastructures (videos, podcasts, and knowledge sharing via Instagram) that were implemented to support the online delivery of the course. Following this, we analyse and discuss the students’ feedback and evaluation of the course based on an open-answer survey and a focus group interview.

Background of the study

The course sits within the wider framework of the AAU-PBL model (Kolmos et al. Citation2004). The AAU-PBL model encompasses problem-oriented project work where students work closely together in smaller groups over three to four months on solving an open-ended problem or design challenge. Students (often) choose their theories, methods, and problems to address (within a frame defined in a programme’s semester curriculum). The project work accounts for half the students’ credit for a semester (15 ECTS); The remaining credits come through courses typically with individual exams. The courses support the project work with relevant knowledge and methods or provide essential disciplinary knowledge within a field. This model is practised across AAU, although varying slightly across programmes and faculties. The course discussed in this article deviates slightly from the standard.

It encompasses a studio- and student-driven, problem-oriented project running over 8 weeks, as well as course and teaching activities (lectures and workshops) to support the students’ project work. The project work is assessed through an oral project group exam (based on the student’s written work and design solution). The course is labelled: ‘Introduction to the Industrial design-engineers design, terminology, process, and methodology’ and is the student’s first encounter with the design domain. They have no prior experience in designing or running design processes (See for an overview of the course outline). The semester poses a project frame where students in groups are asked to design a lamp for a specific target group. The target group is randomly assigned in advance, for example, including a mountain biker, package post, golfer, auto mechanic, baking enthusiast, gardener, dog owner, gamer, runner, delivery person, YouTuber, homeschooler, horse owner, or skater.

Table 1. Course outline.

It is important to notice that the course was not part of the first wave of ‘emergency remote teaching’ (Hodges et al. Citation2020). In Spring 2020, COVID-19 forced many higher education institutions to abruptly switch to online mode. This resulted in cancellations, postponed courses, and emergency lectures over Teams and Zoom, etc. The following year, the situation in many places around the world still did not allow for physical teaching in higher education, meaning that online teaching became a core element of planning education.

The course was scheduled for Spring 2021, having a full year of preparation under the new pandemic circumstances. Due to the high number of students (120), the second semester (Spring 2021) of Architecture and Design was planned a year in advance to be a fully digital course. In this design, a new digital pedagogical structure and elements were designed to embrace and integrate an online mode in a way that would augment the missing physical co-located studio, that is so characteristic of the implicit pedagogical values of design engineering education.

Theoretical framework: structured freedom, flipped engagement, hybridity, and transparency

A design studio is usually a physical place where students are located together and work on design projects. It enables a combination of seamless transition between private and public work, such as peer-to-peer help, tutoring, feedback, advice, and sharing of knowledge. It is a social learning community modelled after the Bauhaus School of Design, where students often have plentiful contact with and learn from each other. Scholars have discussed whether it is a competitive or collaborative environment (Dutton & Grant, Citation1991), and we argue that its main feature is neither. Rather the studio facilitates shared experiences. Research shows people are gathered at the same time and place and go through the same experiences, with the primary purpose being to move and advance a group together (Laursen Citation2017). In the rapid transition to online learning, many teachers had to directly translate traditional onsite educational experiences into a similar online format (Green, Burrow, and Carvalho Citation2020). For example, teachers had to translate conventional lectures 1:1 into online Zoom lectures. However, transitioning a course from onsite to online requires a re-mediation and fundamental rethinking of the pedagogical activities. Rather than focusing on translating the immediate properties of the physical studio, we attempt to re-read and understand the physical studio through the lens of four principles (structured freedom, flipped engagement, hybridity, and transparency) adopted from the area of Networked Learning and PBL (Jones Citation2015; Ryberg et al. Citation2020) to remediate and rethink the role of the physical studios.

Networked Learning is an area of research that emerged in the 1990s as a critical response to how online learning or distance education was predominantly designed with a strong focus on making content available to individual learners (Goodyear et al. Citation2004; Jones Citation2015). In contrast, Networked Learning theory and practice emphasise connections not only between learners and content, but between learners, between learners and tutors, and between learners and a wider learning community i.e. emphasising the importance of social and collaborative learning processes (Dohn et al. Citation2021; NLEC, Citation2021). Rather than being a fixed pedagogical framework, Networked Learning theory and practice rest on shared values, for example, summarised by Hodgson et al. (Citation2012, p. 295):

- Cooperation and collaboration in the learning process.

- Working in groups and communities.

- Discussion and dialogue.

- Self-determination in the learning process.

- Difference and its place as a central learning process.

- Trust and relationships: weak and strong ties.

- Reflexivity and investment of self in the networked learning processes.

- The role technology plays in connecting and mediating.

These values resonate well with underlying principles of problem- and project-based learning (PBL) (Hodgson et al., Citation2012; Ryberg, Davidsen, and Bernhard (Citation2019). PBL can be practised in many ways, but across several authors (Dirckinck-Holmfeld, Citation2002; Kolmos & Graaff, Citation2003; Savery, Citation2006; Savin-Baden, Citation2007) we can derive some more general principles. For instance, that a problem must be the starting point for learning; that problems should be authentic, complex, or real-life problems; that problems are best addressed through active engagement involving research activities, decision-making and writing; that problems should connect to students’ previous experiences. Furthermore, learners must have a high degree of autonomy and responsibility for their learning. Finally, PBL is predominantly conceived of as a collaborative where students work together to address and solve problems. Like the Networked Learning values, PBL can thus be understood as general, flexible pedagogical principles, and it is from these two frameworks we have derived the four more specific principles we discuss in the following: structured freedom, flipped engagement, hybridity, and transparency.

Structured freedom

Structured freedom refers to the principle of balancing structure and freedom in a pedagogical design. A core value in both Networked Learning and PBL is self-determination in the learning process and that students have a high degree of freedom, autonomy, and responsibility. However, it can be challenging for students who are less experienced in taking responsibility for their learning to be confronted with such demands (Cutajar Citation2018). Thus, when working with Networked Learning and PBL principles there is a tension between creating tasks that are too open-ended and unstructured leaving students uncertain, and on the other hand, over-scripting tasks leaving little room for participant direction (thus undermining central pedagogical values). The principle of structured freedom addresses this tension and relates pedagogically to the idea of indirect design from Networked Learning (Goodyear, Citation2015; Jones Citation2015). Indirect design means that teachers cannot design learning as such, but can design for learning to occur by providing worthwhile tasks, appropriate places and tools that students then self-appropriate into their learning activity. The framing of the structured freedom of tasks in a studio setting is central to the pedagogical design of engineering design education (Feast and Laursen Citation2023). In design projects, most of the studio time is unstructured, meaning students are largely free to choose when, how, and where to work. However, the studio setting provides a peer-to-peer learning structure, where students indirectly, because they are co-located, are heavily influenced by each other’s work processes. This serves both as an inspiration, benchmark, support, guidance, and assurance.

Flipped engagement

The concept of flipped engagement is closely related to structured freedom, as it concerns self-determination, but also reflexivity and investment of self in the learning processes. Self-determination and investment of self are important in relation to both PBL and Networked Learning, as students are expected to take ownership of their learning processes. The term flipped is adopted from concepts such as ‘flipped learning’ or ‘flipped classroom’ (Reidsema et al. Citation2017). These approaches hold similarities to active learning and PBL and are in their simplest forms an attempt to use classroom time for active engagement rather than lecturing. For example having students prepare before coming to class by watching video lectures explaining central concepts and then discussing these in class. On a more profound level ‘flipped learning’ is about helping students to take ownership and engage more in their learning – a process that can meet resistance from some students (Kavanagh et al. Citation2017). We, therefore, prefer the term ‘flipped engagement’ as a way of highlighting that it is not only about flipping activities but rather about focusing on students’ investing themselves in the learning process and taking ownership. Flipped Engagement therefore reflects an intention of prompting, provoking, or inviting students to take more ownership of the learning process. Studio work in design engineering education is historically built on a high degree of self-engagement and requires students to include self-directed work and activities. Often, the more ambitious and motivated students take the initiative and display a high degree of ownership, thereby serving as exemplary and becoming the semester’s working norm. Thus, the idea of flipped engagement entails a wish to heighten the students’ engagement, curiosity, and interest by granting more ownership and responsibility over the learning process.

Hybridity

With the term hybridity, we point to the co-presence and integrative nature of the so-called digital and analogue, online and physical, but also to how we can think of hybridity as something extending discussions of the digital and the analogue, such as formal/informal or educational/professional (Nørgård Citation2021). The term hybrid has roots in biology and refers to: ‘cross-fertilisation or the fusion of separate parts or species into a new one […] At its core, hybridity refers to a mixture of different parts into a new breed, form or culture.’ (Hilli, Nørgård, and Aaen Citation2019, 68–69). What is significant to notice in this definition is the emphasis on something ‘new’ underlining that a hybrid is not merely two parts ‘stapled’ together but a genuinely new breed and existence. While some authors, as highlighted by Hrastinski (Citation2019), may use hybrid and blended interchangeably, others interpret it as a term specifically grappling with troublesome dichotomies such as online/offline or digital/analogue, and as implying the emergence of something new. This is elegantly expressed by e.g. (Stommel Citation2012): ‘Hybridity is about the moment of play, in which the two sides of the binaries begin to dance around (and through) one another before landing in some new configuration.’ Apart from implying the emergence of something new, hybridity is also about looking beyond the immediately appearing binaries, such as digital or analogue, and exploring a greater wealth of possibilities such as informal/formal learning contexts, on-ground classroom/ online classroom, disciplinarity/interdisciplinarity, permanent faculty/contingent faculty, learning at the university/learning in the world (Hilli, Nørgård, and Aaen Citation2019; Stommel Citation2012).

Concerning the latter, the physical studio plays a central role in the seamless transition between disciplines, activities, private/public, action/reflection, and educational/professional settings. Furthermore, digital technologies play a central role in physical studios, for example, in relation to mediating collaboration and learning, but also for developing professional knowledge and disciplinary competence (Bernhard et al. Citation2019; Davidsen, Ryberg, and Bernhard Citation2020; Ryberg, Davidsen, and Bernhard Citation2019). With the term hybridity, we emphasise that the digital/non-digital or online/onsite aspects are always co-present and tightly interwoven, but also that we can think of hybridity as involving other dimensions.

Transparency

Transparency, as described by Dalsgaard and Paulsen (Citation2009), refers to the sharing of ongoing work and projects among peers and involves the conscious design of an infrastructure that enables students to follow each other’s work. In studios, the physical co-location means the individual work, progress, pressures, and problems are private, yet visible and accessible to other students (Lawson and Dorst Citation2013). This may be via the sharing of individual work with the group or sharing group work with other groups, such as knowledge sharing among peers. This enables students to become resources for each other and learn beyond the project group through more weakly-tied networks (such as a semester cohort (Ryberg and Davidsen Citation2018)), thus alternating between weak and strong ties (Ryberg and Larsen Citation2008). In design studies, the physical co-presence creates a social community where students may alternate between strongly tied collaboration in small groups to being inspired by others via more loosely tied cooperative forms of engagement (McConnell Citation2002). Here, digital technologies can play a role in connecting and mediating groups and wider networks in new ways. Thus digital technologies can extend transparency beyond what can be accomplished in physical studios, as we explore in discussing the design of the course.

While the physicality of the studio is designed to both socially and culturally scaffold co-located project-led learning, we discuss below the structure and overall design of the digital course to support transparency of group progression, individually structured freedom, a flipped engagement, and integrated hybridity.

The design of the pedagogical elements

As part of the overall design of the course, several learning resources and materials were designed. The course was designed and carried out by the first author, based on her teaching practices and new ideas for executing the course during COVID restrictions. The theoretical framework used in this article to describe and analyse the pedagogical approach was introduced by the second author, whose involvement began during the finalisation and evaluation of the course. Through a process of going back and forth between the course design and educational theory, the authors subsequently identified the four underlying pedagogical principles. This was done through a systematic combining process where theoretical framework, empirical insights, and case analysis emerged simultaneously (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002). In the following, we will reflect on the intent and design of the course material to accommodate the need for pedagogical elements.

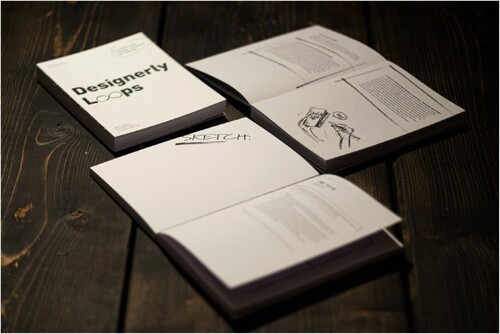

Structuring the freedom through a book

Usually, the physical setting allows the educator to ‘read the studio’ and enable students to follow their peers. Learning design has moved from an apprenticeship to a peer learning PBL activity. This is however challenged in a digital setting, where students are isolated at home. Building on experience, it is challenging for less experienced students, such as early-year students, to handle a high degree of freedom, autonomy, and responsibility in their learning process (Cutajar Citation2018). The course coordinator therefore designed a physical teaching book, with a somewhat different concept.

The book included a blend of theory pages, roadmaps (overview + daily task agenda), worksheets, and reflections. The central idea was that the students had one core teaching roadmap, which supported and offered a structure for new students. The book highlighted how they needed to prioritise and partake in responsibility. The road map intended to offer a learning process, in an open cookbook format. Through the years, the first author (as coordinator) had experienced that 1st-year students otherwise find a process recipe themselves, such as design thinking (that in many cases has a poor fit in terms of learning outcome, depth, and detail in the methods, process, and reflections). The book contained a structure and the methods needed for the eight weeks, explaining in detail what the students could do every day, while also explicitly encouraging the students to follow their individual process when they felt an urge or felt confident to do so. See .

At the end of each chapter, there were reflection pages. These were open reflections, that after an intense structured design action, sought to create a structure, that encouraged students to reflect upon their actions. The reflections were open in the sense, that students themselves decide the level, content and whether they want to partake in the reflection, but it provided a structure that encouraged both reflection in and on action.

Flipped engagement: videos, workshops and a book

A series of worksheets in the book, supported by online workshops were created to enable a more activity-based learning design, that could address the gap between theories/lectures and students’ self-directed work (Goodyear Citation2015). The worksheets in the book were designed to prompt students with questions that could help them break down and focus on their tasks. We were inspired by books such as the business model canvas, that prompts students to engage in workshops and assignments.

To further heighten the students’ engagement, curiosity, and interest, the course coordinator designed a series of online workshops and milestones, with the intent to grant more ownership and responsibility over the learning process. For the workshop, the students were in clusters of four groups. They were typically topic-focused. One example concerned ‘light experiments’, and the students discussed and presented their planned light experiments while getting feedback and inspiration on how to improve them from lecturers and peers. Thus, it was the students’ pre-work and activities, that created the foundation for learning. Similar online milestones were arranged as presentations of students’ work. In the design critique sessions, the students presented the project status to clusters of six peer groups and lecturers. This is to get feedback on their project and to be able to understand the limits of their knowledge. To obtain perspective and insights on how to improve, the pedagogical elements were built on a high degree of self-learning. The main intent was to prompt and invite students to take more ownership of the learning process.

Likewise, 19 short ‘DIY- like’ videos, prompted activities, that the students should engage in. The videos were intentionally kept at an approximate 5-minute length, with one activity and one main message in each of the videos. Therefore, one traditional lecture was replaced with several videos that were made in the style of relevant situated instructions. Most of the videos were illustrative videos, where two designers acted as role models, doing the task the students were about to complete (like watching TV chefs)

See .

Hybridity: company visits

The course podcasts were designed with a hybridity intent. They were designed to embody the co-presence and integrative nature of the digital and analogue, online and physical, educational and professional. Often as a part of design education, students visit professional design studios to ‘get a feel and insight into the design profession’. This proves an inspiration from practice and professional designers become role models. The podcasts were designed as company visits and designer keynotes, that allowed the students to explore a greater wealth of possibilities. Design discussion podcasts were created, and key questions or relevant subjects were discussed and answered. This was meant to be a supplement and to create a design universe where the students are immersed in the design profession’s way of thinking. See . It sought to capture the essence of the physical/digital.

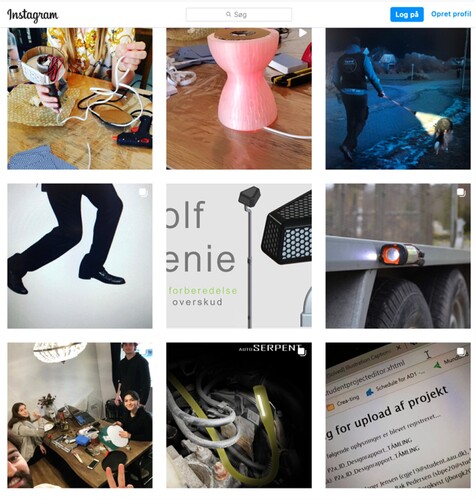

Transparency via instagram

Peer-to-peer learning is essential in the PBL model and is often limited when the students do not physically sit together. As a third space for sharing progress and getting a sense of their peers’ process, the coordinator introduced an Instagram hashtag: #designerlyloops, as an ‘influencing each other’ medium. Instagram was chosen, as it was already widely adopted among the students and rather than setting up an alternative platform, the intention was to tap into their existing social media practices. The activity was introduced as a suggested peer-to-peer knowledge-sharing activity for the student’s own sake. It was not a course requirement; students were motivated by sharing and seeing the processes of their peers. The hashtag was consciously introduced as an infrastructure, that enabled students to follow each other’s work. In a physical co-location, individual progress is visible. The coordinator attempted to mimic this as the students were asked to take photos of their work and photos of the process using the #designerlyloops hashtag (See ). Instagram succeeded in creating transparency in terms of the sharing of ongoing work, and their day-to-day progress, among peers.

Methodology

Study setting

The context of the study was a 2nd-semester 15-ECTS engineering design course for 120 students in Spring 2021. The 120 students were a relatively homogenous group. All were Danish citizens (Danish speaking), between 18–24 years old, gender distribution: 88 females and 32 males, and all obtained a high-school degree. The students were all based near Aalborg, Denmark. Due to COVID-19, the course was organised as a hybrid digital learning design. The projects ran for eight weeks, where the regular university campuses were closed, and students worked from home.

Data collection instruments

In Spring 2021, the first author who coordinated and taught the course collected two types of data from students. As a third data collection instrument, she also kept a record of her observational notes and reflections produced throughout the course. First, focus group interviews were carried out with representatives from each student work group (n = 15). The intent was to collate data from a collective purposeful interaction and discussion between the 15 student representatives simultaneously. Second, an individual evaluation of the course was carried out in the form of an online open-answer survey to collect students’ self-reported assessments (n = 40). This was to ensure a diversity of views and to be able to compare data and insights across the data types obtained from students. Moreover, these were contrasted with my own observational notes based on lectures, discussions, guidance, as well as online posts from Instagram.

Data collection procedure

Group interviews were carried out with the main intent to create a purposeful interaction used to generate data (McLafferty Citation2004). The first author decided to conduct the interviews as part of the formal course/semester evaluations that are mandated by the quality assurance policies in the educational programme. Here students and lecturers meet to critically discuss the course/semester, and this was used as an occasion to conduct the interviews. From the 120 students, each student group (7-8 students) was asked to elect one member of the group to represent the views of the entire group and partake in the focus group interview. The students’ self-selection criteria for the group representative could vary; however, it was typically students comfortable in expressing the group's views in this setting. In total 15 (out of 16) student representatives partook in the focus group interview. Their task was to represent the views of their group (the representative from the 16th group did not show, thus this session missed insights from one group consisting of 8 students). Before the focus group interview an agenda with a list of discussion points was sent out, covering six central issues concerning the learning elements. In preparation, the students were asked to discuss their experiences in their project groups, and then provide feedback in the focus group to encourage and facilitate a contribution of collective participants’ views. For the focus group interviews, the first author acted as moderator, setting the agenda, and opening the discussion. The session was opened as a feedback session, where the students could contribute with feedback and influence the future design of the course. The focus group was openly structured according to a main agenda. To make it tangible for the informants the discussion covered feedback and evaluation of all redesigned learning elements, specifically: (1) book, (2) video courses, (3) podcasts, (4) Instagram, (5) milestones and (6) workshops. The main points of the focus group interview were noted down by the first author and a student minute taker. The focus group interviews were conducted by the end of the course. The insights were then analysed to create themes used as the basis for the online evaluation survey (see Data Analysis).

The open-answer online evaluation survey was sent out by email one week after course finalisation. The individual open-ended survey was intended to allow each student to individually write about their experiences (long answers) and was secondarily intended for data collection with regard to analysing the course design. The second author was involved at this point and the first steps to developing an analytical theoretical framework were started. Based on these initial ideas, the survey contained five questions on the students’ experiences of (1) the hybrid structure, (2) the transparency and knowledge sharing, (3) the notion of structured freedom, (4) the flipped (activity-based) engagement, and (5) other thoughts. Each topic included a theme, e.g. (1) How have you experienced the project's hybrid structure concerning digital and non-digital elements? The main question was followed by elaboration, naming the digital elements (videos, podcasts, Instagram) and non-digital elements (book, physical group work). The question was then followed by a textbox which indicated a place for elaborated feedback. 40 out of 120 students elaborated on their experiences and evaluated the pedagogical design.

Data analysis

To analyse the data, the collected information from the focus group interviews was read by both researchers to generate initial insights. The insights were a first attempt to read into the interviews and represent a first broad qualitative reading of the material that was then expanded into a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The second author, who is an educational researcher specifically interested in digital education, was not part of designing or running the course. The second author was invited as a sparring partner to critically discuss and analyse the course and the data. It was through mutually analysing the interview data and discussing the course design from the theoretical perspective of networked learning (introduced by the second author) that structured freedom, flipped engagement, hybridity and transparency emerged as meaningful theoretical constructs to conceptualise the course design and analyse the students’ experiences. Therefore, these categories were used to design the open-answer survey.

The insights across all data types were then ordered and categorised according to each theme in the theoretical framework: structured freedom, flipped engagement, hybridity, and transparency across the data types. To accomplish this the authors used Miles and Huberman’s (Citation1984) approach to data reduction, data display and conclusion drawing. In the data reduction, the process was to select, sort, focus and simplify the raw data that appeared in the minutes, survey responses and researchers’ notes. The aim was to organise the data into meaningful chunks (i.e. the themes) so conclusions could be drawn. All the responses were printed and cut out. The cut-outs were then structured and clustered into the themes to understand differences and similarities and to conduct further analysis and conclusions. These conclusions were then tested and verified looking for inconsistencies and verification across the different data types. For example, to identify if there were responses that did not fit or would contradict the categorisations.

Critical reflection on data collection and analysis

Collecting data from a course where a researcher/author is a lecturer raises issues. Firstly, doubt can arise as to whether students are sufficiently critical and honest in their feedback. Secondly, whether the author/lecturer can critically distance themselves and look objectively at the data. Regarding the first reservation, the interviews were woven into the formal evaluation process as part of the oral evaluation. These evaluations are carried out routinely every semester, and the students are used to participating in critical discussions and reflections with a course or semester responsible present. Adding to this, the data collected via the open-answer survey were anonymous. We could therefore critically assess whether there were clear discrepancies between viewpoints expressed in the interviews and the open survey (which was not the case). Regarding the second reservation, the data have been discussed and analysed amongst the authors, and as the second author was not part of designing or running the course, he could ask critical questions of observations and present alternative interpretations of statements made by the students. Thus, we have sought to ameliorate these issues in our work by collecting and analysing the data.

An additional critical note is that the depth and breadth of the student’s responses to the open-text questions in the online survey varied. Particularly, the answers (students #30-40) that came in later (after a reminder) were shorter and more superficial (the students are numbered in the order they responded),

Data presentation

In the students’ evaluations of the course, from the focus group and the open-ended questionnaire, different elements of the course stand out. Since the students previously experienced a regular first-semester project in a conventional physical studio (where they were exposed to lectures alongside free-project time) they compared the course to the previous semester where there was a minimum of scaffolding in relation to the structure (according to the students).

Structured freedom

The students approved the course approach to structured freedom. The students mention the very detailed and scheduled beginnings as enabling and creating a sense of security in a new group.

We have a comment regarding the structure of the book; it [the book] ensures that you as a group, can relate your progress [to the other groups]. It is a benchmark of whether you are ahead or behind the process. (Student representative, focus group interview)

As it is stated in the book, we are newcomers, so it has been quite comfortable to have a clear phase-divided structure to get introduced to ID methods and process management, especially later in the process where larger degrees of freedom allowed me to reflect and independently improve, which I found quite exciting and fun. (Student #18)

I thought it worked really well, but sometimes it also falls to the ground. Then you do some things that you just do because the book says so and thus don't quite know why you do it. (Student #16)

I had a hard time staying motivated when there was too much freedom (Student #29)

It was so great to be led by the hand from the start of the project and to be guided directly into the process, especially because nobody knew each other, and I think there would have been complications with stepping forward and taking responsibility. Here it happened by itself, and as we got to know each other better, it fitted well with the structure being freer, and people now were more inclined to step forward and take responsibility. A totally structured process throughout the period had been too much and removed all responsibility, which means a lot. (Student #11)

Flipped engagement

While some students briefly described the course’s organisation as being great or working well in terms of ownership, others elaborated and pointed out, particularly positive motivating aspects.

Super good experiments/methods to get through. Personally, I got a greater sense of ownership through some of them. (Student #17)

It is a super cool way to be activated and for me, it has been a very great learning opportunity, as it gave me a much deeper understanding and insight into the design process than just reading in a book or listening to a presentation. (Student #2)

In a way, I like the fact that we are forced to come out to the user since it is necessary in many contexts. In another way, I would perhaps prefer to see the groups themselves come to realize that you have to go on a context safari or user visit. Sometimes it was somewhat imposed that it should happen. (Student #4)

I feel the hybrid structure gives a particularly well-functioning and effective process. We are introduced to some well-considered, short, concrete, and well-articulated videos, that basically give the same information in 10 min that would normally take a whole lecture. It seems to me this is the way the development is heading, and I see many good elements in this approach. Larger flexibility, especially for large groups. (Student #25)

Hybridity

In general, the students were positive about the digitalisation of the course, and the organisation with a book that provided structure, short video lectures, podcasts for inspiration, Instagram for knowledge sharing across the semester cohort, and milestone/workshops for knowledge sharing in-between semester groups.

It has worked very well. And there has been a fairly fluid connection between the two structures. (Student #24)

The small interactions with the supervisors and lectures are not so freely available. (Student representative, focus group interview)

In the evaluations, we find a surprising positivity related to the course’s online organisation.

I think it worked well. It was really nice that there were no heavy lectures, but that you could ‘discover” the methods yourself in different ways. (Student 37)

It was difficult to keep concentrated in front of your computer for several hours at, for example, milestone meetings. (Student #23)

Transparency

Regarding transparency and knowledge sharing across the semester, the students generally have positive comments despite the university campus being shut down for the project period.

For me personally, it has worked better than the previous semester (physical), as it allowed me to be more focused on my project and be more independent in my project work. Also, it worked well with Instagram, as a platform to show and keep an eye on others’ progress and thoughts. (Student #7)

You were sometimes surprised by the level of other groups for milestones. So, it also helped that people later shared the process “behind the scenes” on Instagram. So, that you could see differences and similarities in the processes that you were not aware of. (Student #20)

It's a fun idea, but we have not used it [Instagram] enough. (Student representative, focus group interview)

I appreciate the mixture of approaches, between reading methods in the book and getting methods explained in the videos. Great to see the engagement in the podcasts and Instagram, it made it easier to feel like a part of a larger semester project, even though we sat alone with our groups. However, I would have liked some physical lectures during the semester, as it is nice to get live explanations and live questions. (Student #14)

Discussion

In looking back at the COVID-19 period and asking what we can learn, different positions emerge. Some have posited the move as a ‘grand experiment’ for online learning that can help us understand the potential and limitations of online learning (Zimmerman Citation2010). Other more cautious voices have raised concerns about comparing rapid experimentation to carefully designed online learning (Hodges et al. Citation2020; Suchman Citation1987). Hodges et al. (Citation2020) argue that we need to understand the rapid experiment as ‘emergency remote teaching’ rather than as examples of ‘online learning’ per se.

Online remote teaching has a longer and richer history. There is a vast body of literature within research areas, such as online learning, distance education, networked learning, blended learning, and mobile learning. There are years of accumulated knowledge on how to design productive online learning, active and engaging learning, and online communities of practice (Hilli, Nørgård, and Aaen Citation2019; Kramer et al. Citation2015). On the other hand, it is also evident (Hodges et al. Citation2020; NLEC, Citation2021) that the period of ‘emergency remote teaching’ has prompted innovation. Many lecturers have creatively, passionately, and competently responded to the difficult situation by developing thoughtful and interesting designs.

In our view, we must not unreflectively slip back into ‘business as usual,’. Instead we should use the current period to think and critically reflect on the insights we might have gained from the COVID-19 period. We can think of the period as a springboard for development, which enables us to ask more fundamental ‘why’ and ‘where to’ questions over merely ‘what’ and ‘how.’ While it is tempting to focus, e.g. on the positive attitude towards video lectures (which is a broader and more general finding (Noetel et al. Citation2021)) and think in terms of ‘blended’ or ‘flipped’ learning, we believe it is important to take a step back.

We have pursued this through a pedagogical-based discussion on ‘How to integrate new technologies to enable networked learning principles such as transparency, hybridity, structured freedom and flipped engagement.’ The study has taken its point of departure in a particularly well-sourced and well-planned course. The digital tools were reframed and re-designed to augment the pedagogical elements which the physical design studios enable.

The physical design studio in many ways provides transparency, structured freedom, hybridity and flipped engagement through peer-to-peer learning. In the physical design studio students are indirectly, through being co-located, heavily influenced by each other’s work processes. Drawings and visual boards such as mood boards, style boards and concept boards are omnipresent (Munk, Sørensen, and Laursen Citation2020). To augment this, social media platforms (Instagram) were utilised to share ongoing work and projects among peers. Likewise, digital media, such as inspirational talks and discussions with professionals on podcasts were published on Spotify and instruction videos on YouTube.

The study aimed to understand: How we can use experiences from COVID-19 to rethink and expand the integration of digital technologies in physical design studios within a PBL context through employing networked learning principles. In reading and analysing students’ thoughtful feedback and reflections, issues are emerging which go beyond the tools and infrastructures mentioned. Issues, such as flexibility, the need for structure and scaffolding, and the appreciation of being able to follow peers (transparency). In working with new directions for engineering design education, it is therefore important that we elevate the discussions of digital education above discussing tools, media, and formats exclusively. Instead, we encourage to focus more on underlying pedagogical principles, such as those we have presented in this paper.

In the study, we find structured freedom, flipped engagement, hybridity and transparency in design education may however serve to be a double-edged sword. While the students in many cases enjoyed and benefitted from the structured freedom, there is a challenge in structuring ill-defined, fuzzy, and wicked problems. This also resonated in the students’ reflections e.g. ‘A totally structured process throughout the period had been too much and removed all responsibility, which means a lot’ (Student #4). A central part of design expertise, hence design education, is dealing with unforeseen uncertainty and ambiguity (Laursen and Tollestrup Citation2015). That means teaching students to be familiar with and handle, what designers are describing as ‘hitting the wall’ and the feeling of having to redo it all (Lawson Citation2019). However, when designing structured freedom, it often results in a well-planned learning process, in which students’ crisis experience is difficult to replicate, which may result in students being less robust in handling inevitable, unique, situated, and unexpected crises.

Moreover, while flipped engagement and hybridity create larger flexibility (e.g. digital/analogue, synchronous/asynchrony, hi-flex/fusion learning) it also moves larger parts of the responsibility for the individual learning experience from the lecturer to the student. This creates a larger pressure and demand on students. Not only do they have to learn something, but they must also be engaged in, take responsibility for, and drive the learning process. Some students are comfortable with that, but in the analysis, we also see that some students wish for more help and interactions during lectures and Q&A sessions: ‘However, I would have liked some physical lectures during the semester, as it is nice to get live explanations and live questions.’ (Student #14) and ‘I have missed being able to ask questions during the videos, as you can in lectures if there is something you have not understood’ (Student #12).

Beyond the professional content, students raise issues regarding having shared experiences and random micro-interactions: ‘Really, you need to see, sit next to, and randomly talk to someone other than your group. Also, since they have largely become your social bubble, and study and free time become very much the same.’ (Student #5). Shared experiences are important in bringing and moving a group together (Laursen Citation2017). This opens a discussion of how digital technologies may foster education as shared experiences with random micro peer-to-peer interactions, where not only knowledge, skills and expertise are built, but also where unexpected relations form and a group is emotionally brought together through shared experiences.

Finally, the increased transparency of using public, social media such as YouTube and Instagram create an infrastructure, that allows outsiders to ‘pass by’. This can support serendipity in the learning process, as outsiders might contribute with additional material or perspectives. However, it also becomes a radically transparent environment, where the students’ peer-to-peer learning environment becomes public to everyone. This makes it an open, hence less safeguarded space for learning.

In this vein, we would encourage more studies on what Cennamo and Brandt (Citation2012) referred to as the ‘right kind of telling’ in academic design studios: How may instructors digitally create an environment where design knowledge can be co-constructed? Where our study shows Instagram and podcasts may serve as parts of a listening-in (provide hybridity and transparency), how can digitalisation further support reflection in and on action? We, for example, encourage future studies on how to support modelling, meta-discussions, and in-progress critiques, which is important for intentional participation in academic design studios (Cennamo and Brandt Citation2012). Such questions are not merely pedagogical or technological but rather try to re-formulate these questions within the values, purpose, and context of engineering design education.

Since the design studio education setting pedagogy in many ways mimics real design practice (Crowther Citation2015), we also suggest instructors and researchers experimenting with design education may find inspiration in how practising design studios integrate new digital technologies and developments such as AI, VR, remote working, digital meetings, extended reality (XR) etc. What digital tools do professional designers find meaningful in their practice? How is the design studio developing, and what could such development entail for design education? Conversely, as instructors are educating the designers of tomorrow, we may ask, which habits and practices should we experiment with? How do instructors want to influence the design practices of tomorrow?

Conclusion

COVID-19 has pushed digitalisation to be implemented at a rapid speed across universities around the world. While this may not necessarily model the way forward for education, these real-life teaching ‘experiments’ provide opportunities for learning and reflecting upon the future of technology implementation in engineering design education. Therefore, our research question was: How can we use experiences from COVID-19 to rethink and expand the integration of digital technologies in physical design studios within a PBL context through employing networked learning principles?

The study has provided several insights and suggested recommendations to the question of the inclusion of online technologies. To summarise some of the main points:

The integrated hybrid structure with digital (videos, podcasts, Instagram, guidance) and non-digital elements (book, physical group work) led to increased focus, motivation, and security throughout the project

Several of the students expressed an appreciation of the videos and podcasts and emphasised the flexibility in allowing for ‘watching it again and again’ as they saw fit.

Some mention the informality of Instagram to keep track of the semester’s progress, whereas others mention they have not used Instagram sufficiently.

The use of Instagram and Podcasts led to interactions with people outside the course (designers, alumni, other lecturers or students), but this also raises questions about privacy and vulnerability when exposing students to an external audience.

All the students appreciated the flow of digital activities that promoted self-directed work in terms of (1) introduction to theory, (2) practice and (3) reflection.

We have highlighted, however, that it is important to look beyond particular tools and media to focus more on underlying pedagogical principles and we have discussed and exemplified the course design through the four networked learning principles. Simultaneously, we have emphasised that digital technologies ‘speak back’ and enable new, unplanned, or unintended opportunities. For example, the open infrastructure added additional transparency to people outside the course, such as designers, alumni, other students, and lecturers. We have therefore suggested that we need to understand the relations between technology and pedagogy as complex. To develop engineering design education, it is therefore important to understand pedagogy and technology as interdependent and to work with both within the wider values, purpose, and context of engineering design education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Linda N. Laursen

Linda N. Laursen is Head of Research at the AAU Design Lab and Associate Professor at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering at Aalborg University. Her main research interests are Design, Circularity, and Innovation.

Thomas Ryberg

Thomas Ryberg is Professor of PBL and digital learning and director of Institute for Advanced Study in PBL (IAS PBL). His primary research interests are within the fields of Networked Learning and Problem Based Learning (PBL).

References

- Adams, R. S., J. Turns, and C. J. Atman. 2003. “Educating Effective Engineering Designers: The Role of Reflective Practice.” Design Studies 24 (3): 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-694X(02)00056-X.

- Bernhard, J., A.-K. Carstensen, J. Davidsen, and T. Ryberg. 2019. “Practical Epistemic Cognition in a Design Project—Engineering Students Developing Epistemic Fluency.” IEEE Transactions on Education 62 (3): 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2019.2912348.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Cennamo, K., and C. Brandt. 2012. “The “Right Kind of Telling”: Knowledge Building in the Academic Design Studio.” Educational Technology Research and Development 60 (5): 839–858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-012-9254-5.

- Crowther, P. 2015. “Understanding the Signature Pedagogy of the Design Studio and the Opportunities for its Technological Enhancement.” Journal of Learning Design 6 (3): 18–28. https://doi.org/10.5204/jld.v6i3.155.

- Cutajar, M. 2018. “Variation in Students’ Perceptions of Others for Learning.” Networked Learning: Reflections and Challenges 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74857-3_5.

- Dalsgaard, C., and M. Paulsen. 2009. “Transparency in Cooperative Online Education.” The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 10 (3): 1492.

- Davidsen, J., T. Ryberg, and J. Bernhard. 2020. ““Everything Comes Together”: Students’ Collaborative Development of a Professional Dialogic Practice in Architecture and Design Education.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 37:100678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100678.

- Dirckinck-Holmfeld, L. 2002. “Designing Virtual Learning Environments Based on Problem Oriented Project Pedagogy.” In Learning in Virtual Environments, edited by L. Dirckinck-Holmfeld and B. Fibiger, 31–54. Samfundslitteratur.

- Dohn, N. B., J. J. Hansen, S. B. Hansen, T. Ryberg, and M. de Laat, eds. 2021. Conceptualizing and Innovating Education and Work with Networked Learning. Switzerland AG: Springer International Publishing.

- Dorst, K., and N. Cross. 2001. “Creativity in the Design Process: Co-Evolution of Problem-Solution.” Design Studies 22 (5): 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-694X(01)00009-6.

- Dubois, A., and L. E. Gadde. 2002. “Systematic Combining: An Abductive Approach to Case Research.” Journal of Business Research 55 (7): 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8.

- Dutton, T. A., and B. C. Grant. 1991. “Campus Design and Critical Pedagogy.” Academe 77 (4): 37–43.

- Ellmers, G., and M. Foley. 2020. “Developing Expertise: Benefits of Generalising Learning from the Graphic Design Project.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 39 (2): 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12260.

- Feast, L., and L. N. Laursen. 2023. “Design from Waste Materials: Situation, Problem, and Solution.” In The 7th International Conference for Design Education Researchers, 29 November - 1 December 2023, edited by Derek Jones, Naz Borekci, Violeta Clemente, James Corazzo, Nicole Lotz, Liv Merete Nielsen, Lesley-Ann Noel. London. https://doi.org/10.21606/drslxd.2023.056.

- Ge, X., L. Leifer, and L. Shui. 2021. “Situated Emotion and its Constructive Role in Collabora-Tive Design: A Mixed-Method Study of Experienced Designers.” Design Studies 75:101020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2021.101020.

- Goodyear, P. 2015. “Teaching as Design.” HERDSA Review of Higher Education 2: 27–50.

- Goodyear, P., S. Banks, V. Hodgson, and D. McConnell. 2004. Advances in Research on Networked Learning, 1–9. Klüwer Academic Publishers.

- Networked Learning Editorial Collective (NLEC), L. Gourlay, J. L. Rodríguez-Illera, E. Barberà, M. Bali, D. Gachago, et al. 2021. “Networked Learning in 2021: A Community Definition.” Postdigital Science and Education 3:326–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00222-y.

- Green, J. K., M. S. Burrow, and L. Carvalho. 2020. “Designing for Transition: Supporting Teachers and Students Cope with Emergency Remote Education.” Postdigital Science and Education 2 (3): 906–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00185-6.

- Hilli, C., R. T. Nørgård, and J. H. Aaen. 2019. “Designing Hybrid Learning Spaces in Higher Education.” Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Tidsskrift 14 (27): 66–82. https://doi.org/10.7146/dut.v14i27.112644.

- Hodges, C. B., S. Moore, B. B. Lockee, T. Trust, and M. A. Bond. 2020. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning.

- Hodgson, V., D. Mcconnell, and L. Dirckinck-Holmfeld. 2012. “The Theory, Practice and Pedagogy of Networked Learning.” In Exploring the Theory, Pedagogy and Practice of Networked Learning, edited by L. Dirckinck-Holmfeld, V. Hodgson, and D. McConnell, 291–305. New York: Springer. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4614-0496-5_17.

- Hrastinski, S. 2019. “What Do We Mean by Blended Learning?” TechTrends 63 (5): 564–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00375-5.

- Jones, C. 2015. Networked Learning: An Educational Paradigm for the age of Digital Networks. Cham, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Jones, D., N. Lotz, and G. Holden. 2021. “A Longitudinal Study of Virtual Design Studio (VDS) use in STEM Distance Design Education.” International Journal of Technology and Design Education 31 (4): 839–865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-020-09576-z.

- Kavanagh, L., C. Reidsema, J. McCredden, and N. Smith. 2017. “Design Considerations.” In The Flipped Classroom, edited by C. Reidsema, L. Kavanagh, R. Hadgraft, and N. Smith, 15–35. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3413-8_2.

- Kolmos, A., F. K. Fink, and L. Krogh. 2004. The Aalborg PBL Model—Progress Diversity and Challenges. Aalborg University Press.

- Kolmos, A., and E. D. Graaff. 2003. “Characteristics of Problem-Based Learning.” International Journal of Engineering Education 2003 (19): 657–662.

- Kramer, B., J. Neugebauer, J. Magenheim, and H. Huppertz. 2015. “New Ways of Learning: Comparing the Effectiveness of Interactive Online Media in Distance Education with the European Textbook Tradition.” British Journal of Educational Technology 46:965–971. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12301.

- Laursen, L. N. 2017. Matching to Openly Innovate with Suppliers: The Phenomenon of Innovation Summits.

- Laursen, L. N., and C. Tollestrup. 2015. “The Role of Ambiguity and Discrepancy in Early Phases of Innovation.” In DS 80-8 Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 15) Vol 8: Innovation and Creativity, Milan, Italy, 27-30.07. 15 (pp. 081-090).

- Laursen, L. N., and C. Tollestrup. 2017. “Design Thinking-a paradigm.” DS 87-2 Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 17) Vol 2: Design Processes, Design Organisation and Management, Vancouver, Canada, 21-25.08. 2017, Aalborg University, Denmark. 21-25 August 2017. pp. 229-238.

- Lawson, B. 2019. The Design Student's Journey: Understanding How Designers Think. Oxon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lawson, B., and K. Dorst. 2013. Design Expertise. Abingdon, Oxon: Architectural Press.

- Lotz, N., H. Sharp, M. Woodroffe, R. Blyth, D. Rajah, and T. Ranganai. 2015. “Framing Behaviours in Novice Interaction Designers.” In Proceedings of DRS 2014: Design’s Big Debates. Vol. 20, 1187–1190. Umeå Institute of Design, Umeå University.

- McConnell, D. 2002. “Action Research and Distributed Problem-Based Learning in Continuing Professional Education.” Distance Education 23 (1): 59–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910220123982.

- McLafferty, I. 2004. “Focus Group Interviews as a Data Collecting Strategy.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 48 (2): 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03186.x.

- Meshur, H., F. Alkan, and H. A. Bala. 2014. “Distance Learning in Architecture/Planning Education: A Case Study in the Faculty of Architecture at Selcuk University.” In Assessing the Role of Mobile Technologies and Distance Learning in Higher Education, edited by P. Ordon∼ez, R. Tennyson, and M. Lytras VC 2016 British Educational Research Association Collaborative Learning in Architectural Education 353, 1–28. Hershey: IGI Global.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1984. “Drawing Valid Meaning from Qualitative Data: Toward a Shared Craft.” Educational Researcher 13 (5): 20–30.

- Munk, J. E., J. S. Sørensen, and L. N. Laursen. 2020. Visual Boards: Mood Board, Style Board or Concept Board? In DS 104: Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (E&PDE 2020), VIA Design, VIA University in Herning, Denmark. 10th-11th September 2020.

- Noetel, M., S. Griffith, O. Delaney, T. Sanders, P. Parker, B. P. Cruz, and C. Lonsdale. 2021. “Video Improves Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Review.” Review of Educational Research 91 (2): 204–236. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654321990713.

- Nørgård, R. T. 2021. “Theorising Hybrid Lifelong Learning.” British Journal of Educational Technology 52 (4): 1709–1723. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13121.

- Reidsema, C., L. Kavanagh, R. Hadgraft, and N. Smith. 2017. The Flipped Classroom: Practice and Practices in Higher Education. Springer. https://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-981-10-3411-4.

- Rodriguez, C., R. Hudson, and C. Niblock. 2018. “Collaborative Learning in Architectural Education: Benefits of Combining Conventional Studio, Virtual Design Studio and Live Projects.” British Journal of Educational Technology 49 (3): 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12535.

- Ryberg, T., L. B. Bertel, M. T. Sørensen, J. G. Davidsen, and U. Konnerup. 2020. “Hybridity, Transparency, Structured Freedom and Flipped Engagement – an Example of Networked Learning Pedagogy.” In Networked Learning 2020: Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Networked Learning, edited by S. Børsen Hansen, J. J. Hansen, N. Bonderup Dohn, M. de Laat, and T. Ryberg, 276–285. Aalborg: Aalborg University Press.

- Ryberg, T., and J. Davidsen. 2018. “Establishing a Sense of Community, Interaction, and Knowledge Exchange Among Students.” SpringerLink 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-19925-8_11.

- Ryberg, T., J. G. Davidsen, and J. Bernhard. 2019. “Knowledge Forms in Students’ Collaborative Work: Pbl as a Design for transfer.” In Designing for Situated Knowledge Transformation, edited by N. B. in Dohn, B. Børsen Hansen, and J. J. Hansen, 127–144. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429275692-8.

- Ryberg, T., and M. C. Larsen. 2008. “Networked Identities: Understanding Relationships Between Strong and Weak Ties in Networked Environments.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 24 (2): 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2007.00272.x.

- Savery, J. R. 2006. “Overview of Problem-Based Learning: Definitions and Distinctions.” Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1002.

- Savin-Baden, M. 2007. “Challenging PBL Models and Perspectives.” In Management of Change—Implementation of Problem-Based and Project-Based Learning in Engineering, edited by E. D. Graaff and A. Kolmos, 9–30. Sense Publishers. http://www.sensepublishers.com/catalog/files/90-8790-013-9.pdf#page=19.

- Schön, D. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner. London: Temple Smith.

- Stommel, J. 2012. “Hybridity, pt. 2: What is Hybrid Pedagogy? Hybrid Pedagogy.” http://hybridpedagogy.org/hybridity-pt-2-what-is-hybrid-pedagogy/.

- Suchman, L. A. 1987. Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sun, J. C. Y., and R. Rueda. 2012. “Situational Interest, Computer Self-Efficacy and Self-Regulation: Their Impact on Student Engagement in Distance Education.” British Journal of Educational Technology 43 (2): 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01157.x.

- Tuckman, B. 2007. “The Effect of Motivational Scaffolding on Procrastinators’ Distance Learning Outcomes.” Computers & Education 49:414–422.

- Zimmerman, J. 2010. “Coronavirus and the Great Online-Learning Experiment.” The Cronicle. https://www.chronicle.com/article/coronavirus-and-the-great-online-learning-experiment/.