ABSTRACT

Kilns used for drying grain and for malting are common features of archaeological excavations in medieval towns and in the countryside. They occur in a variety of situations, including within urban tenement plots, open spaces within the urban landscape, manorial enclosures and field systems. This paper examines what the situation of drying kilns can reveal about the ways in which household and community labour were organised and the role of infrastructure in cultivating and maintaining variegated forms of rural and urban sociality. In doing so, it seeks to contribute to ongoing debates about the legacy of ‘binary’ logics relating to urban and rural life and to the gendered use of space and forms of labour.

The centrality of food and drink to economy, social relations and sustenance means that their study has unique potential to reveal the complex dynamics of medieval life. Their production and consumption transcend perceived dichotomous relations between economy (agriculture and marketing) and domesticity (cooking and consumption), between male (producers) and female (processors) and between rural communities (net producers) and urban ones (net consumers). In medieval studies the binary associations between male and female labour and particular spaces have been subject to extensive critique.Footnote1 Whilst the evidence suggests arable cultivation was primarily male work, women were a part of the agricultural workforce, just as the home was not a site of exclusively female labour. Similarly, historical and archaeological evidence for cultivation in towns, whether in gardens or areas of open ground, challenge a clear distinction between urban and rural, particularly at the level of the small town or borough.Footnote2 Any distinction between ‘economic’ and ‘rural’ spheres is also problematic, given the centrality of the household as a unit of production and the home as place of work.

The dissolution of binary logic, for example in relation to gendered labour, has been stimulated by a diverse range of influences. The growing body of archaeological evidence for domestic space, as well as an increasingly nuanced understanding of historical sources, have contributed substantially to demonstrating simplistic, dichotomous models to be untenable.Footnote3 More generally, across the humanities the influence of feminist, post-human and post-colonial thinking have shifted focus from exploring a simplistic gender divide to the exploration of variegated processes of gendered becoming.Footnote4 Rather than seeking to associate particular activities with specific contexts or groups, the productive potential of a relational approach, in which activities can be viewed as generative ‘assemblages’ of relations between people, materials, objects and other living things, is increasingly being realised, particularly within archaeology.Footnote5 A focus on relations allows us to extend our scope beyond, for example, the processes of brewing ale or cultivating food, to exploring the wider affective capacities of these everyday practices.

Such a focus on the capacity of practice to generate difference also creates the opportunity to challenge other binary distinctions, such as the existence of an urban–rural dichotomy. In urban theory, perceptions of urbanity as being rooted in the stable, material form of the city have been critiqued, with it being recast as a spatially delimited set of productive social processes.Footnote6 Such an approach is valuable for medieval studies, given our continuing pre-occupation with seeking to define urban forms at the expense of understanding the resonances and continuities between urban and rural life. Focusing on these resonances allows us to conceive of urbanity not as an essential property of non-rural places, but as a ‘flickering’ quality which is rendered visible through specific processes and social relations.Footnote7 Such a perspective can already be seen in analyses of the proto-industrialisation of the countryside, for example in relation to the extraction and processing of mineral resources, which have demonstrated there to be varying levels of reliance on agrarian production among rural communities.Footnote8 Gendered analyses of textile production show regional variation in the roles of men, women and children in non-agrarian activities at varying levels of intensity.Footnote9 The phenomenon of specialised, rural, non-agrarian production, alongside the evidence for urban agriculture and horticulture, clearly demonstrates the complex relationship between rural and urban economies, which cannot be neatly differentiated. Food production provides a further example of how urbanity extends beyond towns and cities, shaping rural economies and agrarian regimes, and, by extension, the labour and social relationships underpinning them.

One outcome of this sustained critique of binary logic is to rethink how the concept of difference frames our perspectives on the medieval past. Rather than being defined in relation to normative expectations, difference can be understood as a productive force, central to investigating the diversity of medieval experience and understanding the implications of the multitude of relations between people, their environments, spaces and material possessions.Footnote10 Here, this perspective is adopted to explore the way in which kilns, used for malting and the drying of agricultural produce, could become implicated in the emergence of a range of relations of community, power and commodification. The paper begins with a brief discussion of malting, brewing and the social significance of kilns, before discussing the archaeological evidence for the operation of kilns in towns and the countryside, chiefly between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries.Footnote11

The social dynamics of brewing, malting and the use of kilns

Thanks to the work of Judith Bennett and Mavis Mate in particular, brewing has become the archetypal example of gendered work in medieval England.Footnote12 They demonstrate how, particularly in the period before the Black Death, brewing was dominated by women. Whilst there was variability in how frequently women brewed, the extent to which men were also engaged in brewing and the level of capital investment in specialist facilities, such as boilers (sometimes referred to as furnaces or vat stands), leads (large, often cumbersome vessels used in the mashing process) and brewhouses,Footnote13 brewing was ubiquitous in both town and country. Urban demand for ale impacted agrarian regimes. Demesne producers in the London region turned to the cultivation of barley and dredge, a pattern also observed around other large urban centres such as Salisbury.Footnote14 Despite its ubiquity, archaeological evidence for brewing is limited. The best evidence comes in the form of circular hearths interpreted as vat stands. These occur within buildings interpreted as brewhouses, although there are possible examples from houses.Footnote15 This lack of evidence is likely due to brewing being undertaken intermittently using the domestic hearth and cooking utensils. The evidence provided by lists of goods seized from felons supports this suggestion, with brewing leads being comparatively rare occurrences, implying that the ubiquitous brass pots and pans were used for small scale brewing in non-elite households.Footnote16

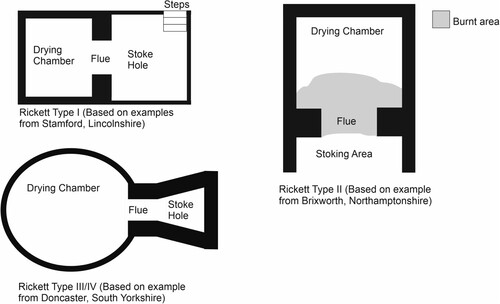

Archaeology can, however, contribute more strongly to our understanding of malting. Manorial records provide indications of the demesne production of malt, and we know that it was traded widely, particularly into major towns. Court records demonstrate the small scale, informal marketing of malt within rural communities.Footnote17 However, these records do not clearly elucidate who was undertaking malting and where this process took place beyond the demesne sector. The archaeological evidence comes in the form of kilns. These are typically situated outside of buildings (although they are sometimes present within barns or malthouses) and are variously interpreted as grain driers, ovens or malting kilns.Footnote18 These kilns typically comprise three elements; a drying chamber, flue and stoking area (). Because the temperature had to be kept relatively low, the fire was typically lit within the flue and, in some cases, a baffle stone was used to further protect the contents of the kiln from intense heat. A range of fuels could be used, including straw, chaff and faggots, depending both upon availability and, perhaps, the specific produce being dried.Footnote19 Where fast burning fuels were used, these kilns were perhaps sealed to retain the heat. The kilns were probably used for a range of purposes including malting and drying grains, with their function rarely being exclusive. They were regularly raked out, meaning that whilst the presence of germinated barley or oats among an assemblage of charred grain from the kiln provides an indication that malting was taking place, its absence does not discount this possibility, nor does its presence imply a kiln was used exclusively for malting.

Figure 1. The key elements of medieval drying kilns based on excavated examples. Source: Drawn by author, after R. Rickett and M. McKerracher, Post-Roman and Medieval Drying Kilns (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2021).

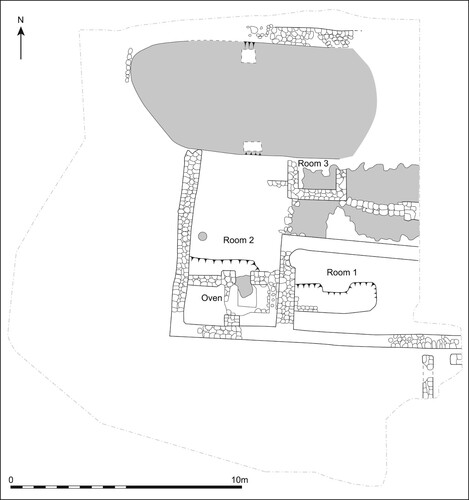

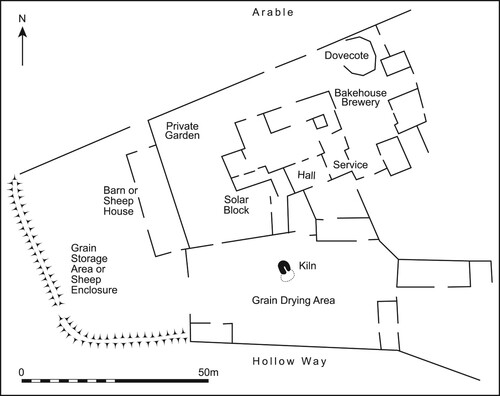

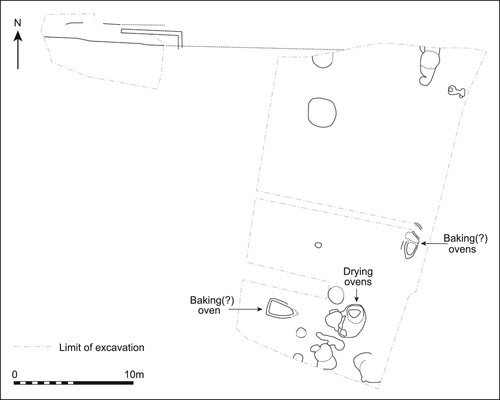

Ovens for baking bread are referred to relatively regularly in historical sources. These are different in form, needing to reach a much higher temperature with the fire situated within the oven itself. The assizes of bread and ale regulated the activities of bakers and brewers, and the imposition of ‘suit of oven’ could compel tenants of villages and small towns to take their bread to a communal oven for baking.Footnote20 Malting ovens are less commonly mentioned, but written sources provide some insight into their use. The pipe rolls of the bishopric of Winchester, the main sequence of manorial accounts for the bishopric estates, record the purchase of haircloth, which was spread over the floor of malting kilns to contain the grain, at the manors of Brightwell (Oxfordshire) and Overton (Hampshire) in 1409–10. At Brightwell 100 nails were purchased at the cost of 1s. 6d. for the repair of the kiln.Footnote21 Elsewhere the cost of maintaining ovens is recorded; for example, at Witney (Oxfordshire) in 1301–2 a man was hired for three days to make a new hearth for the oven and repair the kiln at a cost of 6d.Footnote22 References to the ownership and operation of kilns are more opaque. Whilst it has been proposed that these could have functioned as manorial infrastructure, administered in the same way as bread ovens, this is not a hypothesis that can be easily substantiated.Footnote23 However, inquisitions post mortem reveal some details of malting kilns which potentially mirror the archaeological evidence. For example, at Great Busby (Yorkshire) there was a brewhouse and an oven in 1389, and at Crakehall (Yorkshire) there was an oven with a brewhouse in 1475.Footnote24 Similarly, in 1420 there was a malt kiln and malthouse at Kirkby Bellars (Leicestershire).Footnote25 These are suggestive of the kinds of ovens contained within or adjacent to brewhouses seen in the archaeological record at places such as Brackley (Northamptonshire; ). In other instances, these inquisitions record the division of profits from the kiln: at Dodford (Northamptonshire), Christine, widow of John Cressy the elder was granted access to a malt kiln as well as a third of its profits (perhaps derived from tolls levied on its use), whilst at Kendal (Westmorland) in 1409, Agnes, widow of John de Par, was also entitled to a third of the profits of a malt kiln.Footnote26 Reference to the urban ownership of a malt kiln is made in relation to David the Miller, who owned one near the corn market in Chester.Footnote27 These occasional references demonstrate the variability in the relationship between kilns and brewhouses, their situation as a part of manorial infrastructure and their occurrence in urban settings, all of which can be further investigated through analysis of the archaeological evidence.

Figure 2. Plan of the excavated plot at High Street, Brackley, thirteenth century. Source: Redrawn by Kirsty Harding after R. Atkins, A. Chapman and M. Holmes, ‘The Excavation of a Medieval Bake/Brewhouse at The Elms, Brackley, Northamptonshire, January 1999’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 28 (1999): 5–24.

Kilns have not been the subject of sustained archaeological research. Ricketts’ important study laid out their key elements from a typological perspective, but the potential for understanding kilns as a social presence, bound up in dynamics of power and community, remains untapped.Footnote28 This is despite ethnographic evidence demonstrating how ovens provide an important focus for communal interaction, in their production, maintenance and use, which are often strongly gendered. For example, in Anatolia, Parker demonstrates how the production of the clay domes covering bread ovens, as well as their use in baking, are tasks undertaken by communities of women, with knowledge and skill being passed through generations.Footnote29 In contrast, in Morocco, Steiner shows how the communal bakery is largely a space of male socialisation and interaction, becoming an extension of domestic spaces.Footnote30 Analyses of the construction and situation of ovens in prehistoric settlements have shown how their location in open or communal spaces gave them a role in sustaining gendered communities of practice, which brought together households into relations of co-operation and interdependence.Footnote31 Kilns are a form of infrastructure, which enable, but also demand, labour and as such have social consequences. Kilns facilitate the storage and processing of crops and the sustenance of households and communities, but they also require maintenance and are situated in relation to other forms of infrastructure, such as barns, upon which their function is co-dependent. Kilns are encountered in a variety of urban and rural contexts and the diversity of their situation highlights how the potential of infrastructural relations is highly contextual.Footnote32 It can, therefore, be proposed that understanding the situation of kilns for drying produce and for malting can reveal how this infrastructure could play a role in the emergence and maintenance of variegated urban and rural socialities in medieval England.

Power and profit? The association between kilns and tenement plots

In his analysis of the social organisation of the small town of Godmanchester (Huntingdonshire), J. Ambrose Raftis concludes that ‘in the variety of component elements, although not necessarily the quality of these, the messuage complex at Godmanchester resembled more the curia of the lord in a village than the villager’s tenement.’Footnote33 In this analysis, Raftis is seeking to understand the societal composition of that most elusive of medieval settlement forms: the small town. Such small towns had a strong agrarian base, but also levels of administrative and economic distinctiveness.Footnote34 Implicit within this quote is a contrast in the forms of household and community which we might envisage between village and small town. In likening the Godmanchester messuage to that of a manorial complex, we picture a household that was enclosed and in possession of its own means of subsistence and production, and which operated infrastructure on behalf of others. We might draw this into contrast with the archetypal village household, bound into a regime of obligation and service, and reliant on communal infrastructure. Such stereotyping of communal relations of course masks what was a far more complex picture, in which individuals and households might be a part of multiple communities, enacted and sustained through social ties as diverse as religious belief and the management of common fields.Footnote35

Raftis’ observations about the character of the small town messauge, as well as references in inquisitions post mortem to brewhouses with ovens, resonate with some archaeological evidence for kilns. At High Street, Brackley (Northamptonshire), a detached bakehouse or kitchen was erected in the thirteenth century with a malting kiln coursed with limestone blocks inserted into the south-west room ().Footnote36 Similarly, at the contemporary site of College Street, Higham Ferrers (Northamptonshire), a circular kiln was associated with ancillary buildings.Footnote37 Other similar examples can be observed at Deene End, Weldon (Northamptonshire), Elephant Yard, Kendal (Westmorland), where two large stone-lined kilns were associated with lined pits potentially used for grain storage, and 4 Church Street, Bawtry (Yorkshire), where a kiln was present within a post-built structure.Footnote38 This infrastructure is suggestive of a specialised, likely commercialised, level of production, through which creeping commercialisation became entangled within the spaces and rhythms of domesticity. These relations reveal how forms of labour which might be comfortably associated with the domestic life could potentially become commodified, ultimately resulting in a shifting perception in the value of brewing and malting as reflected in the increasing dominance of, largely male, commercial specialists.Footnote39

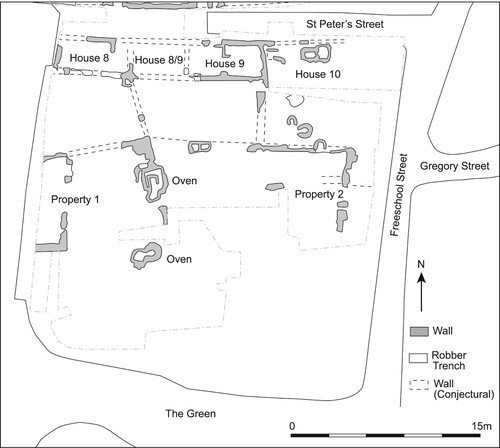

More generally though, kilns are found outside, at the rear of tenement plots. For example, at 71–2 Churchgate Street, Bury St Edmunds (Suffolk), a large kiln, was situated to the rear of the property and similar evidence comes from elsewhere in the town.Footnote40 Comparable evidence comes from sites along St Peter’s Street and at The Green, Northampton, where multiple properties had kilns in their backlands ().Footnote41 Comparable evidence comes from many other towns.Footnote42 Such kilns are also found in smaller towns. In Doncaster (Yorkshire), multiple kilns have been excavated. These include examples from Low Fishergate, where a range of other industrial processes are attested from the archaeological evidence, and Church Walk, adjacent to a tannery.Footnote43 Elsewhere, for example at Sherrard Street, Melton Mowbray (Leicestershire); High Street Reigate (Surrey); and High Street, Much Wenlock (Shropshire), kilns are present within tenement plots fronting main routes through the town.Footnote44 This is a feature of many small towns, for example at Uxbridge High Street (Middlesex) a keyhole shaped kiln was ramped up against the rear wall of a house.Footnote45

Figure 3. Plan showing the location of drying kilns at The Green, Northampton, late thirteenth to late fifteenth century. Source: Redrawn by Kirsty Harding after M. Shaw, ‘Excavations at The Green, Northampton 1983: The Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Phases’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 41 (2021): 257–304.

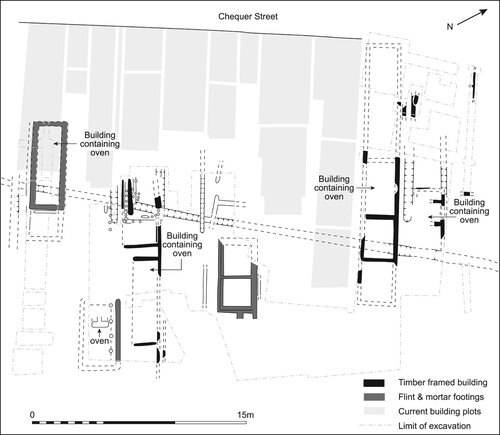

Some urban examples are associated with barns. These could be representative of households engaged in agrarian production, or of them gathering, processing and storing produce, perhaps acting as grain merchants. Two examples come from Bell Street, Reigate (Surrey), with additional examples from St Mary’s Grove, Stafford (Staffordshire) and Pound Lane, Christchurch (Dorset, formerly Hampshire).Footnote46 At Chapel Walk, Dunstable (Bedfordshire), two malt kilns were possibly associated with a barn and at Bishops Garages, Corbridge (Northumberland), a small stone-built kiln was adjacent to buildings of agricultural or industrial function.Footnote47 Indeed, this is not only a feature of smaller towns; at Chequer Street, St Albans, kilns were excavated to the rear of several properties, at least one of which was within a barn ().Footnote48

Figure 4. Plan showing the location of drying kilns at Chequer Street, St Albans, between the late fourteenth and the sixteenth centuries. Source: Redrawn by Kirsty Harding after Rosalind Niblett and Isobel Thompson, Alban’s Buried Towns. An Assessment of St Albans’ Archaeology up to AD 1600 (Oxford: Oxbow, 2005), 274–8.

Kilns and rural households

Such features are not exclusively the preserve of towns, but kilns and brewhouses associated with ‘peasant’ houses are relatively rare in the countryside. Whilst households in isolated areas such as the uplands of south-west England often had their own drying kiln,Footnote49 across the central band of the country it is surprisingly rare to find drying or malting kilns associated with ‘peasant’ plots. One example is Faxton (Northamptonshire), where two phases of malting kiln were associated with an excavated house.Footnote50 The best evidence comes from West Cotton (Northamptonshire) where a remarkable series of malthouses were associated with tenements.Footnote51 These contain stone kilns suggestive of a high intensity of malting at a commercial scale, potentially illustrative of a pervasive ‘urbanisation’ of production as can also be seen, for example, in changes to cropping regimes. At Burton Dassett (Warwickshire) a structure interpreted as a brewhouse, incorporating a malting kiln, was situated adjacent to a house structure.Footnote52 A final rural example is that from the market village of Boteler’s Castle (Warwickshire) where a malting kiln was associated with buildings of twelfth- to thirteenth-century date.Footnote53

Across the zone of nucleated settlement which characterises much of midland England, rural drying kilns are most commonly a feature of manorial complexes, as is suggested by references to these kilns in inquisitions post mortem and the Winchester pipe rolls. Whilst essential for processing the crops of demesne holdings, these may also have been available for the use of tenants. As with manorial mills, such arrangements can be viewed from two perspectives; on the one hand kilns may have provided the lord with an opportunity to extract revenue or service from tenants, on the other there was efficiency in operating kilns as a communal enterprise. In either case, the kilns can be situated within an asymmetric dynamic of dependence, between labour and infrastructure in which households’ access to infrastructure had implications for their subsistence. In many cases there is no clear evidence that these kilns were used for malting specifically. At Wharram Percy (Yorkshire) a drying kiln was found within the area of the north manor, interpreted as a grain drying area ().Footnote54 At Little London, Lechlade (Gloucestershire), a large, stone, eleventh- to thirteenth-century drying kiln was associated with a possible demesne farmstead, which was also equipped with a dovecote and an ancillary building containing an internal kiln. The charred plant remains contained no direct evidence of malting.Footnote55 A similar arrangement can be seen at Raunds Burystead (Northamptonshire). At Rodley Manor, Lydney (Gloucestershire), a drying kiln was situated close to the manorial complex, in association with a probable barn.Footnote56 Other kilns seemingly associated with discrete working areas of apparently high-status rural sites include examples from Rectory Farm, Laughton-en-le-Morethen (Yorkshire), and Days Road, Capel St Mary (Suffolk), where the presence of two kilns and a lined pit (perhaps for steeping) are suggestive of grain processing.Footnote57

Figure 5. Plan of the north manor at Wharram Percy around the mid thirteenth to mid fourteenth century, showing the location of the postulated grain processing area. Source: Redrawn by Kirsty Harding after Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts, Wharram. A Study of Settlement on the Yorkshire Wolds, IX. The North Manor Area and North-West Enclosure. York University Archaeological Publications 11 (York: University of York, 2004), 32–3.

Three examples from Northamptonshire are more conclusively associated with malting. At Raunds Furnells, a malting complex, comprising a kiln and stone-lined tank, was associated with the western manor complex (c.1200–1350).Footnote58 A malting kiln, circular baking oven and a vat stand were situated within the kitchen block erected in the later fourteenth century. At Lime Street, Irthlingborough, a malthouse or barn of a scale suggestive of commercial production was part of the fourteenth-century manorial farm, whilst at West Cotton there was a manorial malthouse in use by the twelfth century.Footnote59

These kilns were presumably used for the drying and processing of crops from demesne holdings, being a tool not only of agrarian production but of exerting seigniorial power over the community whose service obligations would have included contributing to the harvesting of crops. We can only speculate whether these kilns were also available to tenants and, if so, whether payment was required. Regardless of how they were used, we can envisage the area around the kiln being a social space in which people came together to load and unload fuel and produce, and to maintain the kiln. These kilns represent a kind of quasi-public space, situated within the confines of the manorial messuage but in the open, creating opportunities for socialisation, for gossip and community building.Footnote60 These were not only sites of seigniorial control, but also locales in which the labour of maintaining the kilns, processing produce and sustaining the household and community took place. Similar opportunities were, of course, afforded in the cultivation of open fields. We can, then, situate these kilns at a nexus between imposed power and the potential of social interaction for the building of community and all that entailed; resistance, co-operation, social and economic relationships, and as a part of the material processes through which forms of sociality were sustained.

Kilns in larger towns

The most striking contrast between the urban and rural evidence is the density of kilns within some urban neighbourhoods. Whilst it is impossible to determine how many kilns were in use simultaneously, the occurrence of kilns in adjacent plots in places such as The Green/St Peter’s Street, Northampton, and Chequer Street, St Albans, suggests a strong association between households and their kilns.Footnote61 Whereas the rural evidence, from areas dominated by nucleation at least, appears characterised by communal infrastructure of various sorts, the urban evidence is suggestive of investment in ‘private’ infrastructure. In some instances, this infrastructure was situated within the house itself. At Townwall Street, Dover (Kent), an area occupied by fishermen around the waterfront, a grain processing area was identified at one end of a domestic dwelling, into which were incorporated multiple phases of malting kilns.Footnote62

These urban kilns are firmly situated within domestic spaces. To call these spaces private is disingenuous; as Vanessa Harding argues, plots often shared facilities and access, and the boundaries between plots would have been low enough to facilitate observation and socialisation.Footnote63 Given the strong agrarian base of small towns in particular, it is probable that these kilns represent the domestic-scale processing of agricultural produce, be that malting, parching or drying, which our understanding of the balance of labour would suggest was chiefly undertaken by women, perhaps as an extension of their role as alewives. Particularly in boroughs, we might consider how the administrative context stimulated the emergence of a more privatised form of infrastructure and with it a more insular social dynamic. Households were in greater control of the infrastructure of production, could potentially operate it for profit, and its use did not facilitate communal interaction in the same way as seen in the countryside. This contrast vividly demonstrates how infrastructural relations have highly contextual consequences and are bound up in the material processes through which individuals, households and communities work to maintain their ways of being.Footnote64

This privatisation of production is most apparent at the unambiguously commercial end of the scale. Intensive malting can be inferred from the scale and longevity of kilns, as well as the presence of associated infrastructure such as steeping pits. Particularly good examples come from Northampton, Leicester and Norwich. At St John’s Street, Northampton, a twelfth- to thirteenth-century maltsters’ premises was excavated.Footnote65 This tenement has the infrastructure required for commercial malting; three drying kilns, a well and lined pit. Other excavated evidence from the town is more ambiguous, but the presence of potential malthouses and the occurrence of multiple kilns may be suggestive of relatively intensive malting or grain drying. For example, at Kingswell Street two wells and two malting kilns, one of which appears to be situated within a malthouse, were excavated, with an adjacent plot having a bread oven within an ancillary building.Footnote66 On the north side of Woolmonger Street there were two kilns to the rear of one excavated property, one of which was seemingly incorporated into a malthouse with an adjacent well.Footnote67

In Norwich, excavations at Alms Lane demonstrate all stages of malting and brewing to have taken place. This includes the processing of unthreshed barley, steeping in a clay-lined pit, drying in a kiln and grinding the malt using quern stones.Footnote68 A final example is the site at High Street, Leicester, where a brewhouse incorporating a large malting kiln and multiple hearths for the mashing process were present in a building occupying the rear of a tenement, with a further malt kiln to the rear of an adjacent property.Footnote69 Perhaps related to this group, given the labour required to construct them, are Nottingham’s distinctive cave maltings, where malting kilns and wells were situated within excavated subterranean caves, seemingly aligned to above-ground plot boundaries.Footnote70 Further evidence of commercial malting comes from Brandon Road, Thetford (Norfolk). Here, at a peripheral site, some 17 kilns dating from the twelfth to sixteenth century are suggested to be representative of intensive commercial scale malting, perhaps targeted at the export market.Footnote71

This focus on the infrastructure of crop drying and malting highlights diversity and difference, and lays the limitations of binary thinking bare. Whilst a contrast can be drawn between a general tendency for ‘private’ infrastructure in towns and communal infrastructure in the countryside, a clear urban–rural divide is undermined by the fact that households from those living in the smallest farmsteads to the largest towns were engaged in grain processing. We can also conceive of commercialised malting and brewing taking place both in large towns and in the countryside, closely linked to domestic spaces. Urbanisation and commerce stimulated an intensification of production, demanding new forms of interaction with tools, infrastructure and produce, being generative of new forms of social relations and domestic economy. Similarly, considering brewing as largely the domain of women tells only a part of the story. The dynamics of community, of social interaction, which emerge out of the use of kilns are inconsistent; in short different ways of drying grain mediated the emergence of different forms of sociality, which transcend any straightforward divide between the urban and rural.

Kilns and community: ‘isolated’ kilns in town and country

In both town and country kilns associated with house-plots and farmsteads are only one part of the picture. Kilns are commonly found in isolated locations, associated with field systems. In some instances, these are a part of wider grain processing facilities, perhaps operating under the authority of the demesne. The site at Great Gabbard Windfarm, near Sizewell (Suffolk), is particularly remarkable.Footnote72 Here post-built structures are interpreted as granaries and multiple kilns were excavated. The presence of milled grains has been taken to suggest that these features represent infrastructure for both the drying and processing of grains. Less elaborate infrastructure is seen at Weekley Wood Lane (Northamptonshire) and Mytton Oak Road (Shropshire), where kilns appear associated with barns.Footnote73 Others, such as those at White Horse Stone and Northumberland Bottom (both Kent) are more isolated.Footnote74 It would seem logical to interpret such kilns as drying, rather than malting, kilns, with drying taking place following harvesting, away from settlements, mitigating the risk of fire and reducing the costs of transporting fuel and storing damp grain. Even among these isolated examples, though, there is some suggestion that malting was taking place. At Warren Farm, Ashford (Kent), the presence of quantities of charred barley has been taken to tentatively suggest that malting could have been taking place, with similar evidence coming from Harry Weston Road, Binley (Coventry), where grain was potentially being processed for sale and consumption within Coventry.Footnote75 At Great Barton (Suffolk), on the outskirts of Bury St Edmunds, it is possible that excavated kilns were used for malting.Footnote76 These are associated with lava quern fragments, indicating the grinding of grain. It might be proposed that this infrastructure was used by townspeople who worked on the surrounding land but lacked the land to operate a kiln, of which several have been excavated from the urban core. Although appearing isolated, such kilns would have been situated within lively landscapes of cultivation and industry.

This infrastructure might be considered as communal, an extension of the communal management of open fields. It is perhaps coincidental that examples come from counties such as Kent and Suffolk in which seigniorial power was weaker than elsewhere in the country and, therefore, tenants potentially had greater control over the infrastructure of production. Yet, they might also be sites of tension; for example, conflict might emerge over access to fuel between rural artisans and landowners, especially where wood was being used.Footnote77 From the perspective of gender, these kilns pose a question: were they primarily used by men, given their location away from settlements, or were they operated by women, or members of the community as a whole? Like those kilns within manorial complexes, these appear to be a form of communal infrastructure, which could serve to mediate and strengthen the bonds of sociality which underpinned community, although here, perhaps, away from the observation of manorial officials and passing neighbours.

‘Isolated’ kilns in the urban landscape

Such relatively ‘isolated’ kilns also occur in both large and small towns, either singly or as a part of a cluster of such features. These are often, but not always, in peripheral areas, associated with industry or cultivation. For example at Derngate and Marefair/Sol Central, Northampton, kilns have been excavated from such areas, and a similar example comes from St Peter Street, Norwich.Footnote78 In Bury St Edmunds, at St Mary’s Square and Peckham Street, multiple kilns came from sites seemingly given over to industrial use ().Footnote79 Comparable evidence comes from The White Hart, Ely (Cambridgeshire), where a total of 11 kilns dating to the fourteenth to fifteenth centuries were excavated from an area characterised by cultivation soils, whilst at Silver Street, to the south of Ely Cathedral a further baking oven or drying kiln was located within an area shown to be largely vacant on Speed’s seventeenth-century map.Footnote80 Similar evidence comes from Huntingdon (Huntingdonshire), where three kilns dating to the period c.1150–1250 come from an area used for industrial processes and horticulture, and from the Eastgate Motors site in Lincoln.Footnote81 Examples from smaller towns include those from 8 Manor Street, Berkhamsted (Hertfordshire), where two possible malting kilns were situated beyond the town ditch within an area of industrial production, and at Bread and Meat Close, Warwick, where a stone-lined kiln and several hearths were situated close to a thirteenth-century tile kiln.Footnote82 At Southgate, Hartlepool (Co. Durham), several kilns were situated around the waterfront.Footnote83 They are of a form considered by the excavator to be appropriate for grain drying or malting and were associated with clay-lined troughs, suggestive of the latter.

Figure 6. The location of the drying kiln at Peckham Street, Bury St Edmunds (Suffolk), twelfth to thirteenth century. Source: Redrawn by Kirsty Harding after David Gill, ‘40 Peckham Street, Bury St Edmunds' (Unpublished report, Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service, 2012).

That towns possessed the infrastructure for the processing of crops should not be surprising given the widespread use of gardens and open areas for crop husbandry. However, we might question whether the dynamics behind their operation were the same as their rural counterparts. Multiple hypotheses could be advanced to interpret these features. They may have simply been built and operated by households with insufficient land to erect a kiln within their plot. They could represent communal infrastructure or some form of commercial enterprise. Where kilns were clearly a part of demesne infrastructure they might be understood, like mills, as tools of seignorial authority, as bound up in the dynamics of class division within communities. Elsewhere, they are perhaps representative of non-elite agency over rural infrastructure, their situation within shared agrarian landscapes, be that fields or areas of urban cultivation, implying communal collaboration or enterprise. That drying kilns occur in comparable urban situations may represent the establishment and curation of communal bonds through co-operation at a level beneath that of the formal institutions of urban life, particularly within larger towns. The possibility remains that these were commercialised drying facilities; however, their situation can be contrasted with those kilns found within more bounded, nominally private, spaces.

Conclusion: kilns, difference and medieval sociality

The production of food and drink transcends many of the divides which have shaped our understanding of medieval society; those between male and female, town and country and class. By focusing on the infrastructure of production, my aim here has been to shift focus from the question of what was produced. to explore how production was organised and, by extension its social implications. The evidence presented here allows for difference in the use of kilns to be laid out. Whilst a broad scheme can be presented, whereby kilns might be situated within plots or in open areas, as communal or private, this only takes us so far. We can begin to tease out some conclusions about how the processing of grain had implications for the emergent dynamics of communities. Firstly, we can conceive of communal kilns mediating relations of co-dependence and co-operation (as well, perhaps, as tension and conflict) with the location of these kilns, within manorial complexes, open fields or peripheral urban areas, intersecting with the dynamics of power, and the ways in which the agency of peasants and townspeople might exercise communal control over key pieces of infrastructure. Secondly, and in contrast, we can consider how certain households, predominantly, but not exclusively, those in towns, were able to invest in ‘private’ infrastructure. In turn, this can be related to the breakdown of seigniorial control, the freedoms granted to burgesses and growing commercialisation, which incentivised the intensification and specialisation of activities and, with it, capital investment in malting kilns, malthouses and brewhouses. This variability demonstrates the contextual specificity of labour relations, showing how they are not directly transferable between households or communities, being relationally, and therefore contextually, constituted.

These observations can, in turn, be related to two key areas of enquiry. The first of these is gender, and the association between brewing and women. The archaeological evidence is mute on who was operating kilns, whether communal or private (although it is clear from the inquisitions post mortem that profits from, and access to, kilns were granted to widows). It does, however, allow us to consider how households were drawn into social relations with their neighbours or existed as self-sufficient units, which in turn has implications for gendered experiences. We can question whether the communal use of kilns led to the emergence of homosocial group identities, the kiln being a nodal point in the social networks underpinning a community as suggested by ethnographic parallels, or whether the presence of kilns in the home served to reinforce the links between women, victualling and domestic spaces.

The second relates to the contrast between town and country. The evidence provided by kilns does not sit neatly into an urban–rural dichotomy and challenges our perceptions about the essential characteristics of urban and rural life. Even in larger towns, the presence of kilns in open spaces shows the importance of agrarian production to everyday life, whilst commerce seemingly stimulated investment in infrastructure by both urban and rural households. Perhaps the biggest distinction is not in relation to economy but power and the comparative freedom of urban, and some rural, households, to exercise control over the infrastructure of production. Kilns then are situated at a nexus of economic, political and social agencies and their use resulted in a diversity of social forms, the social potential of infrastructure being highly contextual. This is a key turn in the study of medieval food culture, demanding us to shift focus from asking how food culture reflected medieval society, to questioning how the processes of food and drink production were shaped by, and mediated the emergence and sustenance of, diverse and complex forms of sociality.

The evidence provided by drying kilns shows us that the need to dissolve binary thinking and embrace complexity is more than a philosophical imperative, it is one demanded by the growing body of evidence we have for medieval life. Drying and malting grain clearly transcended any urban–rural divide, but in the underpinning dynamics of power, of communal labour, of household inter- or in-dependence a flickering urbanity can be drawn into focus within certain places and communities. But we must take care in advancing interpretations too. It would be tempting to propose that private infrastructure, linked to the urban home, belongs in an urban, feminine, sphere, whilst the more communal and often isolated rural kilns suggest labour was gendered differently in the countryside. To do so risks advancing a simple binary logic. Rather, we can reflect on how diverse gendered urban and rural bodies emerged from entanglements with these kilns, which extended beyond just the processing of grain; the kilns can act as a starting point for questioning the multiplicity of gendered bodies which could emerge from these variegated communities of practice.

Open data statement

The data underpinning this paper are accessible in the supplementary materials.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (43.1 KB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful to members of the Medieval Diet Group, particularly Jim Galloway, David Hinton, Chris Woolgar and Chris Dyer for their useful comments on elements of this research and to Kirsty Harding for the production of illustrations.

Data availability statement

The Kilns Online Dataset is available as a supplementary file.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ben Jervis

Ben Jervis is Reader in Archaeology at Cardiff University, where he specialises in the archaeology of later medieval England. His research focuses particularly on urbanism and material culture. He is the PI of the UKRI funded project Endure: Urban Life in a Time of Crisis. Enduring Urban Lifeways in Later Medieval England, which examines the archaeology of small towns from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries.

Notes

1 E.g. P.J.P. Goldberg, ‘Space and Gender in the Later Medieval English House’, Viator 42, no. 2 (2011): 202–32; M. Howell, ‘The Gender of Europe’s Commercial Economy, 1200–1700’, Gender & History 20 (2008): 519–38; Sarah Rees Jones, ‘Public and Private Space and Gender in Medieval Europe’, in The Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe, eds. Judith Bennett and Ruth Karras (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 246–61, doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199582174.013.023.

2 Christopher Dyer, ‘Gardens and Orchards in Medieval England’, in idem, Everyday Life in Medieval England (London: Hambledon Press, 1994), 113–31 (121–4); B. Jervis and others, ‘The Archaeology of Emptiness? Understanding Open Urban Spaces in the Medieval World’, Journal of Urban Archaeology 4 (2021): 221–46 (238–9).

3 Goldberg, ‘Space and Gender’; K. Catlin, ‘Re-Examining Medieval Settlement in the Dartmoor Landscape’, Medieval Settlement Research 31 (2016): 36–45 (44); Miriam Müller, ‘Peasant Women, Agency and Status in Mid-Thirteenth to Late Fourteenth-Century England: Some Reconsiderations’, in Married Women and the Law in Premodern Northwest Europe, eds. Cordelia Beattie and Matthew Stevens (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2013), 81–113 (112–13); and Sherri Olson, ‘Women’s Place and Women’s Space in the Medieval Village’, in Rural Space in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age. The Spatial Turn in Premodern Studies, ed. Albrecht Classen (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012), 209–26.

4 E.g. Hannah Stark, Feminist Theory after Deleuze (London: Bloomsbury, 2017); Rosi Braidotti, Posthuman Feminism (Cambridge: Polity, 2022); and H. Cobb and R. Crellin, ‘Affirmation and Action: A Posthuman Feminist Agenda for Archaeology’, Cambridge Archaeological Journal 32 (2022): 265–79.

5 E.g. B. Jervis, ‘Becoming through Milling: Challenging Linear Economic Narratives in Medieval England’, Cambridge Archaeological Journal 32 (2022): 281–94; O. Harris. ‘(Re)assembling Communities’, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 21 (2014): 76–97; and K.A. Antczak and M. Beaudry, ‘Assemblages of Practice: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Human-Thing Relations in Archaeology’, Archaeological Dialogues 26, no. 2 (2019): 87–110.

6 E.g. N. Brenner and C. Schmid, ‘Towards a New Epistemology of the Urban’, City 19, nos. 2–3 (2015): 151–82 (165–6); K. Derickson, ‘Urban Geography I: Locating Urban Theory in the “Urban Age”’, Progress in Human Geography 39 (2015): 647–57.

7 B. Jervis, ‘Assemblage Theory and Town Foundation in Medieval England’, Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26 (2016): 381–95 (392).

8 E. Carus-Wilson, ‘Evidences of Industrial Growth on some Fifteenth-Century Manors’, Economic History Review, 2nd series, 12 (1959): 190–205; Joan Thirsk ‘Industries in the Countryside’, in Essays in the Economic and Social History of Tudor and Stuart England in Honour of Professor R.H. Tawney, ed. F.J. Fisher (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961), 70–88; J. Birrell, ‘Peasant Craftsmen in the Medieval Forest’, Agricultural History Review 17 (1969): 91–107; and I. Blanchard, ‘The Miner and the Agricultural Community in Late Medieval England’, Agricultural History Review 20 (1972): 93–106.

9 John Lee, The Medieval Clothier (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2018), 120–43; John Oldland, ‘The Economic Impact of Clothmaking on Rural Society’, in Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, eds. Martin Allen and Matthew Davis (London: Institute of Historical Research, 2016), 249.

10 B. Jervis, ‘Examining Temporality and Difference: An Intensive Approach to Understanding Medieval Rural Settlement’, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 29 (2022): 1229–58 (1232); Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman (Cambridge: Polity, 2013), 15, 21.

11 A list of kilns identified through this research can be found in the additional digital materials to this essay. This is not a comprehensive list and excludes those identified with certainty as bread ovens. The list was populated through a search of historic environment datasets available through Heritage Gateway, the list of excavations detailed in Medieval Britain and Ireland published by the Society for Medieval Archaeology and a rapid survey of published archaeological reports.

12 E.g. Judith Bennett, Ale, Beer and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300–1600 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996); P.J.P. Goldberg, Women, Work and Life Cycle in a Medieval Economy: Women in York and Yorkshire c.1300–1520 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992); Mavis Mate, Daughters, Wives and Widows after the Black Death. Women in Sussex 1350–1535 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1998); and D. Postles, ‘Brewing and the Peasant Economy: Some Manors in Late Medieval Devon’, Rural History 3 (1992): 133–44.

13 C.M. Woolgar, The Culture of Food in England 1200–1500 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 35–8.

14 James Galloway, ‘Driven by Drink? Ale Consumption and the Agrarian Economy of the London Region, c.1300–1400’, in Food and Eating in Medieval Europe, eds. Martha Carlin and Joel T. Rosenthal (London: Hambledon, 1998), 87–100 (97–8); John Hare, A Prospering Society. Wiltshire in the Later Middle Ages (Hatfield: Hertfordshire University Press, 2011), 60.

15 Jervis, ‘Temporality and Difference’, 1248.

16 Ben Jervis and others, The Material Culture of English Households c.1250–1600 (Cardiff: Cardiff University Press, 2023), 73–80.

17 J. Galloway, ‘The Malt Trade in Later Medieval England’, (paper presented at the International Medieval Congress 2016); Postles, ‘Brewing in the Peasant Economy’, 135; and P. Slavin, ‘Ale Production and Consumption in Late Medieval England, c.1250–1530: Evidence from Manorial Estates’, Avista Forum Journal 21, nos. 1–2 (2011): 62–72 (63–5).

18 See Robert Rickett and Mark McKerracher, Post-Roman and Medieval Drying Kilns (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2021) for a survey.

19 Rickett and McKerracher, Drying Kilns, 13, 24.

20 E.g. J. Davis, ‘Baking for the Common Good: A Reassessment of the Assize of Bread in Medieval England’, Economic History Review, 2nd series, 57 (2004): 465–502; Christopher Dyer, Peasants Making History. Living in an English Region 1200–1540 (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2022), 318.

21 Mark Page, ed., The Pipe Roll of the Bishopric of Winchester 1409–10. Hampshire Record Series 16 (Winchester: Hampshire County Council, 1999), 109, 220.

22 Mark Page, ed., The Pipe Roll of the Bishopric of Winchester 1301–2. Hampshire Record Series, 14 (Winchester: Hampshire County Council, 1996), 137.

23 Christopher Dyer, ‘The Late Medieval Village of Wharram Percy: Living and Consuming’, in A History of Wharram Percy and its Neighbours, ed. Stuart Wrathmell. York University Archaeological Publications 15 (York: University of York, 2012), 327–49 (333).

24 Calendar of Inquisitions post mortem and Other Analogous Documents, vol. 14: Edward III (London: H.M.S.O., 1952), 78 (no. 80); Calendar of Inquisitions post mortem … , vol. 16: 7–15 Richard II (London: H.M.S.O., 1974), 284 (no. 740).

25 Calendar of Inquisitions post mortem … , vol. 21: 6–10 Henry V 1418–1422 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2002), 151 (no. 520).

26 Calendar of Inquisitions post mortem … , vol. 21: 6–10 Henry V 1418–1422, 352 (no. 964); Calendar of Inquisitions post mortem … , vol. 19: 7–14 Henry IV 1405–1413 (London: H.M.S.O., 1992), 241 (no. 667).

27 Christopher Lewis and Alan Thacker, eds., A History of the County of Chester: vol. 5, part 1: The City of Chester: General History and Topography. Victoria Histories of the Counties of England (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, 2003), 44–55.

28 Rickett and McKerracher, Drying Kilns.

29 B. Parker, ‘Bread Ovens, Social Networks and Gendered Space: An Ethnoarchaeological Study of Tandir Ovens in Southeastern Anatolia, American Antiquity 76, no. 4 (2011): 603–27 (611–13).

30 Robin Steiner, ‘The Moroccan Public Oven Project’ (PhD diss., Brown University, 2006), 37–9.

31 Parker, ‘Bread Ovens’, 621–3; Jennie Ebeling, ‘Making Space: Women and Ovens in the Iron Age Southern Levant’, in In Pursuit of Visibility. Essays in Archaeology, Ethnography and Text in Honour of Beth Alpert, eds. Jennie Ebeling and Laura Mazow (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2022), 92–102 (97–100).

32 Noel Cass, Tim Schwanen, and Elizabeth Shove, ‘Infrastructures, Intersections and Societal Transformations’, Technological Forecasting & Social Change 137 (2018): 160–7 (165–6); D. Wilkinson, ‘Towards an Archaeological Theory of Infrastructure’, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 26 (2019): 1216–41 (1238).

33 J.A. Raftis, Small Towns in Late Medieval England: Godmanchester 1278–1400 (Toronto: Pontifical Institute, 1983), 142.

34 Christopher Dyer, ‘Small Places with Large Consequences: The Importance of Small Towns in England, 1000–1540’, Historical Research 75 (2002): 1–24 (6–9).

35 M. Müller, ‘A Divided Class? Peasants and Peasant Communities in Late Medieval England’, Past & Present 195 (Supp. 2) (2007): 115–31 (120–2); Phillipp Schofield, Peasant and Community in Medieval England (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2003), 213.

36 R. Atkins, A. Chapman, and M. Holmes ‘The Excavation of a Medieval Bake/Brewhouse at The Elms, Brackley, Northamptonshire, January 1999’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 28 (1999): 5–24 (11–14).

37 C. Jones and A. Chapman, ‘A Medieval Tenement at College Street, Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 31 (2003): 125–36 (129–31).

38 A. Thorne, ‘A Medieval Tenement at Deene End, Weldon, Northamptonshire’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 31 (2003): 105–124 (112); N. Hair, ‘Elephant Yard, Kendal, Cumbria. Stage Two Archaeological Evaluation and Excavation’ (Unpublished report, Lancaster Archaeological Unit, 1998); B. Nenk, S. Margeson and M. Hurley, ‘Medieval Britain and Ireland in 1991’, Medieval Archaeology 35 (1991): 184–308 (277–8).

39 Bennett, Ale, Beer and Brewsters, 145–7.

40 Andrew Tester, ‘71–72 Churchgate Street, Bury St Edmunds’. BSE 339 (Unpublished report, Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service, 2010); Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service, ‘BSE 155 7–11 Westgate Street, Bury St Edmunds’ (Unpublished report, Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service, 1998); and John Duffy, ‘Angel Hotel: Bury St. Edmunds BSE 231. A Report on the Archaeological Excavations, 2004’ (Unpublished report, Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service, 2006).

41 M. Shaw, ‘Excavations at the Green, Northampton 1983: The Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Phases’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 41 (2021): 257–304 (267–9).

42 See for example Craig Cessford, ‘Former Old Examination Hall, North Range Buildings, New Museums Site, Cambridge. An Archaeological Excavation’ (Unpublished report, Cambridge Archaeological Unit, 2017), https://doi.org/10.5284/1088728; Craig Cessford, Mary Alexander, and Alison Dickens, Between Broad Street and the Great Ouse: Waterfront Archaeology in Ely. East Anglian Archaeology 114 (Cambridge: Cambridge Archaeological Unit, 2006) 34–5; Phil Chavasse and Chris Clay, ‘Archaeological Evaluation Report: Trial Trenching at 116 High Street, Lincoln’ (Unpublished report, Allen Archaeology, 2008), https://doi.org/10.5284/1017480; Pre-Construct Archaeology (Lincoln), ‘Archaeological Watching Brief at 320 High Street, Lincoln, Lincolnshire’ (Unpublished report, Pre-Construct Archaeology, 1997), https://doi.org/10.5284/1015884; K. Nichol, ‘Land to the North of Sandford Street, Lichfield, Staffordshire: A Post-Excavation Assessment and Research Design’ (Unpublished report, Birmingham Archaeology, 2001), https://doi.org/10.5284/1032468; A.G. Kinsley, ‘Excavations on the Saxo-Norman Town Defences at Slaughterhouse Lane, Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society 97 (1993): 14–63 (28–30); Alan Vince and others, Excavations in Newbury, Berkshire 1979–1990 (Salisbury: Wessex Archaeology, 1997), 88–9; Richard Brown and Alan Hardy, Trade and Prosperity, War and Poverty. An Archaeological and Historical Investigation into Southampton’s French Quarter (Oxford: Oxford Archaeology, 2011), 146; and Christine Mahany, Alan Burchard, and Gavin Simpson, Excavations in Stamford, Lincolnshire. 1963–69. Society for Medieval Archaeology, monograph series 9 (London: Society for Medieval Archaeology, 1982), 19.

43 J. McComish and others, ‘Excavations at Low Fisher Gate, Doncaster, South Yorkshire’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 82 (2010): 73–230 (97–8); A. Chadwick, ‘Church Walk (Formerly Askew’s Print Shop), Doncaster, South Yorkshire. Archaeological Post-Excavation Report Volume 1’ (Uunpublished report, Archaeological Services WYAS, 2008), https://doi.org/10.5284/1029313.

44 Stephen Jones, ‘An Archaeological Excavation at 14–24 Sherrard Street, Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire’ (Unpublished report, University of Leicester Archaeological Services, 2005), https://doi.org/10.5284/1010962; D. Lewis, ‘High Street, Much Wenlock: Post-Excavation Assessment’ (Unpublished report, Archenfield Archaeology, 2008), https://doi.org/10.5284/1002337; and D. Williams, ‘Excavations at 43 High Street, Reigate, 1981’, Surrey Archaeological Collections 75 (1984): 111–53 (121).

45 J. Mills, ‘Excavations in Uxbridge, 1983–84’, London Archaeologist 5, no. 1 (1984): 3–11 (8–9).

46 David Williams and Rob Poulton, The Medieval and Later Development of Reigate. Excavations in Bell St and High St, 1979–90 (Woking: Spoilheap Monographs, 2022), 21; Keith Jarvis, Excavations in Christchurch 1969–1980 (Dorchester: Dorset Archaeological Society, 1983), 22–4; and M.O.H. Carver, ‘Excavations at St Mary’s Grove, 1980–84’, Anglo-Saxon Stafford. Archaeological Investigations 1954–2004. Field Reports On-line, FR5 ST29 [data-set] (York: Archaeology Data Service, [distributor], 2010), https://doi.org/10.5284/1000117.

47 North Pennines Archaeology, ‘Report on An Archaeological Field Evaluation on Land at Bishops Garages Car Park, Corbridge, Northumberland’ (Unpublished report, North Pennines Archaeology, 2004).

48 Rosalind Niblett and Isobel Thompson, Alban’s Buried Towns. An Assessment of St Albans’ Archaeology up to AD 1600 (Oxford: Oxbow, 2005), 274–8.

49 E.g. G. Beresford, ‘Three Deserted Medieval Settlements on Dartmoor: A Report on the late E. Marie Minter’s Excavations’, Medieval Archaeology 23 (1979): 98–158 (140–2); E.M. Jope and R.I. Threlfall, ‘Excavation of a Medieval Settlement at Beere, North Tawton, Devon’, Medieval Archaeology 2 (1958): 112–40 (123).

50 Laurence Butler and Christopher Gerrard, Faxton. Excavations in a Deserted Northamptonshire Village 1966–68. Society for Medieval Archaeology monograph series 42 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), 248–50.

51 Andy Chapman, West Cotton, Raunds. A Study of Medieval Settlement Dynamics AD 450–1450. Excavation of a Deserted Medieval Hamlet in Northamptonshire 1985–89 (Oxford: Oxbow, 2010), 225–9.

52 N. Palmer and J. Parkhouse, ‘Burton Dassett Excavations: A Digital Supplement to Burton Dassett Southend, Warwickshire: A Medieval Market Village’ [data-set] (York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor], 2022), https://doi.org/10.5284/1083492.

53 C. Jones and others, ‘Excavations in the Outer Enclosure of Boteler’s Castle, Oversley, Alcester, 1992–93’, Transactions of the Birmingham and Warwickshire Archaeological Society 101 (1997): 1–98 (32–5).

54 Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts, Wharram. A Study of Settlement on the Yorkshire Wolds, IX. The North Manor Area and North-West Enclosure. York University Archaeological Publications 11 (York: Department of Archaeology, University of York, 2004), 32–3.

55 D. Stansbie and others, ‘The Excavation of Iron Age Ditches and a Medieval Farmstead at Allcourt Farm, Little London, Lechlade, 1999’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 131 (2013): 25–92 (32–5).

56 Headland Archaeology, ‘Highfield Hill, Lydney, Gloucestershire. Archaeological Mitigation’ (Unpublished report, Headland Archaeology, 2021), https://doi.org/10.5284/1089118. A further drying oven is situated closer to the manorial complex, but is likely to be of Roman date.

57 I. Roberts and M. Rowe, ‘Rectory Farm, Laughton-en-le-Morethen; (Unpublished report, Archaeological Services WYAS, 2007), https://doi.org/10.5284/1030616; J.L. Tabor, ‘Land East of Days Road, Capel St Mary, Suffolk. An Archaeological Excavation’ (Unpublished report, Cambridge Archaeological Unit, 2010), https://doi.org/10.5284/1012066.

58 Michael Audouy and Andy Chapman, Raunds. The Origin and Growth of a Midland Village AD 450–1500. Excavations in North Raunds, Northamptonshire 1977–87 (Oxford: Oxbow, 2009), 98–9.

59 A. Chapman, R. Atkins, and R. Lloyd, ‘A Medieval Manorial Farm at Lime Street Irthlingborough, Northamptonshire’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 31 (2003): 71–104 (81–6); Chapman, West Cotton, 225–9.

60 C. Wickham, ‘Gossip and Resistance among the Medieval Peasantry’, Past & Present 160 (1998): 3–24.

61 Shaw, ‘Excavations at The Green’, 267–70; Niblett and Thompson, Alban’s Buried Towns, 276.

62 Keith Parfitt, Barry Corke, and John Cotter, Townwall Street, Dover. Excavations 1996 (Canterbury: Canterbury Archaeological Trust, 2006), 30, 37.

63 V. Harding, ‘Space, Property, and Propriety in Urban England’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History 32 (2002): 549–69.

64 Cass and others, ‘Infrastructures’ 165–6; Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, ‘Matters of Care in Technoscience: Assembling Neglected Things’, Social Studies of Science 41, no. 1 (2011): 85–106 (90, 96).

65 Jim Brown, Living Opposite to the Hospital of St John: Excavations in Medieval Northampton 2014 (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2021), 58–77.

66 J. Brown, ‘Excavations at the Corner of Kingswell Street and Woolmonger Street, Northampton’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 35 (2008): 173–214 (189–91).

67 I. Soden, ‘A Story of Urban Regeneration: Excavations in Advance of Development off St Peter’s Walk, Northampton, 1994–7’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 28 (1998–9): 61–127 (75–6).

68 Malcolm Atkin, Alan Carter, and D.H. Evans, Excavations in Norwich 1971–1978, Part 2. East Anglian Archaeology, Report 26 (Norwich: Norwich Survey, 1985), 144–260.

69 R. Buckley, N.J. Cooper, and M. Morris, Life in Roman and Medieval Leicester. Excavations in the Town’s North-East Quarter, 1958–2006. Leicester Archaeology Monographs 26 (Leicester: University of Leicester School of Archaeology and Ancient History, 2021), 485–8.

70 A. MacCormick, ‘Nottingham’s Underground Maltings and Other Medieval Caves: Architecture and Dating’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society 105, 2001: 73–99.

71 Carolyn Dallas, Excavations in Thetford by B.K. Davison between 1964 and 1970. East Anglian Archaeology Report 62 (Dereham: Field Archaeology Division, Norfolk Museums Service, 1993), 57.

72 David Gill and Simon Cass, ‘Greater Gabbard Wind Farm Onshore Works, Sizewell Wents, Leiston. Post-Excavation Assessment Report’ (Unpublished report, Suffolk County Council, 2013).

73 T. Molloy, ‘52 Weekley Wood Land, Weekley, Northampton: Report on a Programme of Archaeological Observations’ (Unpublished report, Pre-Construct Archaeology, 2015), https://doi.org/10.5284/1089612; R. Bradley, ‘Archaeological Investigations at Land South of Mytton Oak Road, Shrewsbury, Shropshire’ (Unpublished report, Worcester Archaeology, 2016), https://doi.org/10.5284/1040063.

74 Museum of London Archaeology, ‘Northumberland Bottom, Gravesend, Kent – Integrated Site Report’ (Unpublished report, Museum of London Archaeology, 2009), https://doi.org.10.5284/1044802; Oxford Archaeology (South), ‘White Horse Stone, Aylesford, Kent – Integrated Site Report’ (Unpublished report, Oxford Archaeology, 2017), https://doi.org/10/5284/1044807.

75 R. Atkins and M. Webster, ‘Medieval Corn-Driers Discovered on Land probably once part of Repton Manor, Ashford’, Archaeologia Cantiana 132 (2014): 275–90 (277–82); Paul Mason, ‘Archaeological Evaluation of Land off Harry Weston Road, Binley, Coventry’ (Unpublished report, Northamptonshire Archaeology, 2007), https://doi.org/10.5284/1018836.

76 John Craven, ‘Moreton Hall East, Great Barton, Bury St Edmunds’ (Unpublished report, Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service, 2005), https://doi.org/10.5284/1010602.

77 E.g. J. Galloway, D. Keene, and M. Murphy, ‘Fuelling the City: Production and Distribution of Firewood and Fuel in London’s Region, 1290–1400’, Economic History Review, 2nd series, 49 (1996): 447–72; J. Birrell, ‘Peasant Craftsmen’, Agricultural History Review 17 (1969): 91–107 (96).

78 M. Shaw, ‘Excavations on a Medieval Site at Derngate, Northampton’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 19 (1984): 63–82 (75); Pat Miller, Tom Wilson, and Chiz Harwood, Saxon Medieval and Post-Medieval Settlement at Sol Central, Marefair, Northampton. Archaeological Excavations 1998–2002 (London: MoLAS, 2005), 62; A. Shelley and S. Tremlett, ‘Excavations at St Peter’s Street, Norwich, 2001’, Norfolk Archaeology 44 (2001): 644–75.

79 John Craven, ‘New Store, Nuffield Hospital, St Mary’s Square, Bury St Edmunds’ (Unpublished report, Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service, 2006); David Gill, ‘40 Peckham Street, Bury St Edmunds’ (Unpublished report, Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service, 2012).

80 A. Jones, ‘Archaeological Investigations at The White Hart, Ely, 1991–2’, Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society 82 (1993): 113–38; S. Kenney and R Casa-Hatton, ‘A Medieval Oven and Ditches at the Railway Mission, Silver Street, Ely: An Archaeological Evaluation’ (Unpublished report, Cambridgeshire County Council Field Unit, 2000).

81 Rachel Clarke, ‘Bronze Age, Roman, Late Saxon, Medieval and Post-Medieval Remains in Huntingdon Town Centre, Cambridgeshire: An Archaeological Evaluation’ (Unpublished report, Cambridgeshire County Council Field Unit, 2004); Colin Palmer-Brown, ‘Archaeological Evaluation Report: Former Eastgate Motors, Wragby Road, Lincoln’ (Unpublished report, Pre-Construct Archaeology (Lincoln), 2002).

82 Martin Cuthbert, ‘Post-Excavation Assessment and Updated Project Design: 8 Manor Street, Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire Post-Excavation Assessment’ (Unpublished report, Archaeological Services & Consulting Ltd, 2011); Danny McAree, ‘Archaeological Excavation at Bread and Meat Close, Warwick, Warwickshire’ (Unpublished report, Northamptonshire Archaeology, 2007).

83 R. Daniels, ‘The Development of Medieval Hartlepool: Excavations at Church Close, 1984–85’, Archaeological Journal 147 (1990): 337–410 (403).