ABSTRACT

Growing evidence from multiple countries in Africa documents sexual violence in schools. However, when that violence is committed by teachers it is shrouded in secrecy. This article identifies disconnects between quantitative and qualitative research, policy and practice, which have contributed to these silences. We address some of these silences through a dialogical analysis of mixed methods data from the Contexts of Violence in Adolescence Cohort study (CoVAC) with young people in Uganda. The analysis illuminates girls’ experiences of sexual violence by school staff, and patterns of discrimination and inequality that increase vulnerabilities. The data reveal how schools vary in their institutional responses and, in the absence of institutional support, girls develop strategies to resist sexual coercion. Overall, our analysis exposes significant disconnects between policies and practices of sexual exploitation in schools. We conclude that dialogical, mixed methods research approaches have strong potential to better understand and address silences in policy and practice on highly sensitive topics.

Introduction

It was not until the 1990s that the existence of sexual violence in schools entered public awareness, and a cluster of studies around the turn of the century raised alarms about girls’ safety in schools (Mirsky Citation2003; Mirembe and Davies Citation2001). Several of these studies reported girls’ victimisation by male teachers, including sexual taunts and threats, unsolicited sexual physical contact, sexual favours in return for goods or grades, or rape and sexual assault (Jewkes et al. Citation2002; Leach et al. Citation2003; George Citation2001). Much of this work was located in Sub-Saharan Africa, stemming from research and practice addressing girls’ vulnerability to HIV/AIDs, and gender disparities in access to school (Leach and Humphreys Citation2007). Synthesising emerging evidence, the UN World Report on Violence Against Children (2005) stated:

Studies suggest that sexual harassment of schoolgirls is common throughout the world, to varying degrees by teachers themselves as well as by students, and that it may be particularly common and extreme in places where other forms of school violence are also prevalent (119).

In this article, we reflect on silences surrounding sexual violence committed by teachers. There are significant ethical, normative and methodological barriers hindering research on teacher sexual violence. Back in 2001, Ugandan researchers reflected on the challenges of researching sex with young people:

Studying sexual behaviour is problematic. It is largely hidden and all we have to go on is what informants tell us about their behaviour. However, people do not talk about sex easily in formal research settings, particularly when older researchers are interviewing adolescents (Nyanzi, Pool, and Kinsman Citation2001, 84)

Quantitative and qualitative researchers address this problem in divergent ways, through lenses that draw on different and seemingly incommensurate ways of understanding social phenomena (Greene Citation2005). Within a positivist paradigm, complexity is addressed reductively, by dividing social phenomena into manageable variables, and then studying associations between variables. Although some quantitative approaches consider how contexts shape social phenomena, positivist approaches also often reduce the exploration of social phenomena to the individual level. In contrast, interpretive, qualitative approaches to social inquiry view human experience as deeply embedded within contexts, and seek to describe contextual dynamics of experience, viewing knowledge not as neutral but as imbued with values and subjectivities, including those of the researchers. In developing research tools for research on gender-based violence, quantitative researchers emphasise careful design of survey questions, additional training for researchers, and selecting a data collection method designed to increase disclosure (WHO Citation2016a), with some evidence that more anonymous methods like a computer-assisted self-administered screening increased disclosure of intimate partner violence compared to face to face interviews (Hussain et al. Citation2015). Qualitative researchers have taken almost the opposite direction, not reducing but increasing human interaction, through participatory and ethnographic research designs, that aim to create ‘safe’ interactions with familiar yet non-judgemental researchers to stimulate open discussion, in the hope that this will increase disclosure (Chilisa and Ntseane Citation2010; Moletsane, Mitchell, and Lewin Citation2015). Perhaps therefore it is not surprising that these different approaches produce different stories about the nature of violence. But how does each version capture the lived experiences of young people? Which version has most influence on policy and practice? How can they be reconciled? Might reconciliation help to produce better insights into the nature of teacher sexual violence in schools?

In this article, we discuss our attempts to resolve these questions through analysing quantitative and qualitative data from the Contexts of Violence in Adolescence Cohort study (CoVAC). This is an ongoing longitudinal, mixed methods study (2017–2023), which explores violence through childhood, adolescence and into early adulthood with young people in central Uganda. Our intention is to generate a nuanced analysis of girls’ experiences of sexual exploitation in schools, and to address some of the silences at the interface of research, policy and practice. In researching violence in schools, there are multiple layers of translation and reinterpretation needed, between the voices of young people, teachers, and their communities, and between policy actors who frame or enact local, national, and international policies, and between researchers. Between these layers, we suggest, sexual violence by school staff sometimes emerges and more often remains hidden. We begin by scrutinising literature on teacher sexual violence globally, and in Uganda, and identify how gaps in research are echoed by silences in policy and practice. In reflecting on research approaches that can address these silences, we draw insights from scholarship on mixed methods (Greene Citation2005, Citation2012; Fetters and Molina-Azorin Citation2017) and comparative education (Unterhalter Citation2009) that have articulated ways of bridging disconnects in research approaches, and policy and practice linked to gender and education, through dialogue. We discuss quantitative and qualitative evidence on girls’ experiences of teacher sexual violence. Through documenting the dialogue within the research team, our aim is to shed further light on why there are so many silences, and to show the potential for mixed methods research to better inform policy and practice on sensitive topics.

Teacher sexual violence in research-policy-practice

Since the 2005 UN Report, there has been a growing impetus among international organisations and NGOs to implement policy and programmes on violence in schools, and its gender dimensions. This work has its roots in two major strands, one concerned with children’s rights, the other with women’s rights. The first strand, associated with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), and, more recently SDG 16.2, ‘end abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children’, is exemplified by the World Health Organisation’s influential INSPIRE framework (WHO Citation2016b), which presents seven strategies for ending violence against children. The second strand, associated with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and SDG Target 5.2: ‘eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation’, has generated the RESPECT framework, with seven strategies to prevent violence against women (WHO Citation2019). Although both frameworks recognise the complexity of violence, and the need to intervene across multiple sites, including within schools, in neither is there any mention of teacher sexual violence. Nor has teacher sexual violence featured prominently within interventions within these strands. For example, none of the 67 trials using the WHO Health Promoting School Framework focused on violence interventions in low or middle-income countries, nor had teacher sexual violence as a primary outcome (Langford et al. Citation2015). Of the 16 interventions evaluated using RCTs and quasi-experimental studies for the UK FCDO’s flagship programme: What Works to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls, which infomred the WHO RESPECT framework, two were school-based interventions of dating violence and peer violence, but the report makes no mention of teacher sexual violence (Kerr-Wilson et al. Citation2020).

Attempting to bridge these strands is a third strand, focusing on school-related gender-based violence (SRGBV) – sexual, physical or psychological acts or threats of violence, in and around schools, as a result of gender norms and stereotypes, and enforced through unequal power dynamics (UNESCO and UN Women Citation2016). With its more explicit focus on gender-based violence in schools, interventions to prevent SRGBV have paid some attention to sexual violence by school staff, including through guidance on Codes of Conduct (UNESCO and UN Women Citation2016; UNGEI Citation2019), and a Connect with Respect curriculum tool for teachers (UNESCO Citation2018). These guidance documents draw from a wide range of evidence sources, not limited to experimental research designs and trials, and often grounded in NGO practice. Missing from their reports, however, is robust evidence on the scale or dynamics of teacher sexual violence.

Robust quantitative data are elusive on teacher sexual violence. Currently, there are no routine international and comparable surveys that ask specifically about forms of teacher violence within school environments. There are several large-scale national surveys that have been used to inform work on violence in childhood and adolescence, but only two include questions on sexual violence by teachers: Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Violence Against Children surveys (VACS). Though their country reports do not report findings on teacher sexual violence, there have been occasional secondary analyses to examine sexual violence by teachers. Jewkes et al. (Citation2002) analysed the 1998 DHS in South Africa, and reported that 1.6% of women (aged 15-49) had been raped before the age of 15 years, with teachers the largest group of perpetrators (33%) (Jewkes et al. Citation2002). In a series of factsheets on SRGBV drawing from VAC surveys with 13–24 year old young people, Together for Girls reported 2% of girls and less than 1% of boys surveyed in Uganda in 2016 had experienced sexual violence by teachers (Together for Girls Citation2021). Both DHS and VACS are household surveys that were not explicitly developed to ask questions about teacher sexual violence in schools. Both surveys ask whether participants have experienced forms of sexual violence, and then include teachers as one option in a list of perpetrators, which may lead to lower prevalence estimates compared to asking specifically about teacher violence (Tanton et al. Citation2022). The low numbers reported in surveys mean that researchers tend therefore to present overall sexual violence figures rather than reporting separately on sexual violence by teachers. Perceptions of low prevalence may in turn help to explain why explicit mention of teacher sexual violence is missing from the intervention strategies, like INSPIRE and RESPECT, that draw primarily on evidence from trials. Interventions seek robust evidence to underpin their designs, but by relying on quantitative methods that do not adequately capture this evidence, they reinforce the silences around teacher sexual violence.

Accounts of teacher sexual violence in qualitative studies contrast sharply with the quantitative evidence in presenting a picture of the normalisation of sexual violence in schools. While qualitative evidence has grown on how schools provide environments that condone or foster sexual harassment between pupils, there are, however, relatively few in-depth analyses of sexual violence committed by school staff, which remains shrouded in a culture of silence (Chikwiri and Lemmer Citation2014; Turner Citation2020). A study using interviews and focus groups to discuss SRGBV with young people in 14 secondary schools in western and central Uganda traced the unequal power relations and sexual double standards operating in schools that rendered girls vulnerable to sexual harassment, particularly when they refused sexual advances of male pupils and teachers, though teachers denied this (Muhanguzi Citation2011). An ethnographic study on gender violence in two primary schools in central Uganda, which involved the researcher spending several months using a range of interviews, participatory activities, observations and informal conversations with children and school staff, revealed how some male teachers used their institutional positioning to exercise authority in sexualised ways and to sexually exploit female pupils (Turner Citation2020). An earlier ethnographic study of gender socialisation in six secondary schools in Botswana and Ghana traced gendered inequitable practices, including sexist remarks and innuendos in male teachers’ communications with female pupils, and rumours of teachers seeking sexual favours (Dunne Citation2007). One study using interviews and focus groups with teachers in an Ethiopian secondary school, discussed how male teachers narrated sex between teachers and female pupils as commonplace, though none of them admitted to engaging in these practices themselves (Altinyelken and Le Mat Citation2018).

Other studies have discussed how teacher sexual violence mirrors practices of violence or transactional sex in the communities outside schools. In a focus group study with six girls in a low income township neighbourhood in South Africa, girls reported enduring experiences of sexual violence in and out of the school, involving boyfriends, male teachers, and men in the neighbourhood and at home (Bhana Citation2012). Girls’ attempts to exercise agency were constrained in the context of structural and social inequalities and pervasive gender norms through which male sexual violence was asserted. In post-conflict settings, including Liberia, Burundi and Sierra Leone, studies have reported heightened sexual violence (Steiner et al. Citation2021; Hendriks et al. Citation2020). For example, a study involving interviews and focus groups in six intervention areas by Plan International in Sierra Leone found sexual exploitation by teachers in junior secondary schools took the form of sex for grades, with girls without financial means to pay bribes to progress to the next class particularly vulnerable (Reilly Citation2014).

The emerging qualitative evidence paints a picture of commonplace teacher sexual violence, with risks to girls elevated in contexts with high levels of poverty, food insecurity and gender inequality, with poorly managed and resourced education systems (Leach, Dunne, and Salvi Citation2014). But the evidence remains limited, with case studies too small scale to provide reliable data about prevalence and patterns. The Human Rights Watch study ‘Scared at School’, for example, which was cited in the UN World Report as demonstrating that abuse of girls by teachers and students in South African schools was ‘widespread’ (120), based its evidence on interviews in 3 provinces with 36 girls reported by NGOs to have experienced sexual abuse or harassment by teachers or students (George Citation2001). Often the reports of teacher sexual violence are second hand, sometimes based on rumour and hearsay. While the secrecy surrounding such violence may make this inevitable, there can be a tendency to over-infer, that, for example, teacher sexual violence is ‘pervasive’ in Ethiopia (Altinyelken and Le Mat Citation2018, 648), or that data from 20 sexual abuse cases provides a ‘comprehensive picture of gender-based violence in primary schools’ in Zimbabwe (Chikwiri and Lemmer Citation2014, 95). Though the emerging qualitative evidence from diverse locations is compelling, it is important not to compensate for the lack of quantitative evidence by over-generalising from qualitative studies that have not been designed to draw conclusions about other contexts, or to be generalised across contexts. In turning to how one mixed methods research project has attempted to tackle the silences surrounding teacher sexual violence, we begin by discussing the Ugandan context.

Teacher sexual violence in policy and research in Uganda

Article 24 of Uganda’s Constitution (1995) protects every person from any form of torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and gives children a right to be educated without humiliating and degrading treatment. Since this time, the Government of Uganda has signed and put in place a significant number of international and national legal and policy frameworks and instruments to protect children (MoESTS Uganda Citation2015, 8–10). One of the most notable frameworks is the National Strategic Plan on Violence against Children in Schools (2015–2020), developed by the Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports (MoESTS) together with the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development (MGLSD). The strategic plan, at the time of writing still being revised for the period of 2021–2025, provides clear instructions for implementing the national strategy on violence in schools, including sexual violence. It identifies key actors (involving inter alia school officials or local councils) and key instruments (policies or legal institutions) and specifies their roles in the reporting, tracking, referral and responses chain (MoESTS Uganda Citation2015, 18, Figure 2.2). The plan does not, however, discuss the penalties specifically on teacher sexual violence. The code of conduct (Government of Uganda Citation2012) lists sanctions (from warnings/reprimands, to withholding increments, to dismissal), but does not provide guidance on which sanction should be implemented for specific offences. More generally, Uganda’s Penal Code (Amendment) Act 8 (2007) abolishes corporal punishment and sets out strong measures against defilement. Under point 129 (1) of the Penal Code (Amendment) Act 8, any person who attempts to perform a sexual act with another person who is below the age of 18 years commits an offence and is on conviction, liable to imprisonment not exceeding 18 years. Uganda’s Children Act (Amendment) 2016 (Government of Uganda Citation2016) specifies mandatory reporting of child abuse (including sexual abuse) by medical practitioners, teachers and social workers or counsellors, but the penalties are only vaguely specified, with the stipulation under point ‘8A Prohibition of sexual exploitation’ (9), that a person who commits a sexual offence (against children) is liable, on conviction, to a fine not exceeding 100 currency points or to a term of imprisonment, not exceeding five years.

Uganda has also had a large number of NGO programmes working to prevent violence, some of which have been supported by in-depth research. As with the research globally discussed above, there is a disjuncture between qualitative and quantitative evidence in relation to teacher sexual violence in Uganda, with the very limited quantitative data indicating low prevalence (Together for Girls Citation2021), while it is a recurrent theme of qualitative studies. One strand of the Ugandan research, stemming from work in public health linked to HIV/AIDs along with women’s rights, has focused on community-based interventions to reduce intimate partner violence and transactional sex (Abramsky et al. Citation2014). Some of these studies have argued that girls have some agency in transactional sex, through using sexual relationships to improve their material situation (Nyanzi, Pool, and Kinsman Citation2001; Bell Citation2012). Others have traced how gender norms constrain girls’ agency, with men’s control of resources and norms about feminine submissiveness restricting girls’ capacity to negotiate safe sex (Ninsiima et al. Citation2018). Though mostly focusing on transactional sex in communities, a few studies cite male teachers among the perpetrators (Nyanzi, Pool, and Kinsman Citation2001; Kyegombe et al. Citation2020), though not the role of school institutions. Another strand has focused on violence in schools, documenting widespread use of corporal punishment, and that school-based initiatives can significantly reduce violence (Devries et al. Citation2015). While teacher sexual violence has not been a central theme, several qualitative studies of violence in schools in Uganda have reported male teachers coaxing girls into sex, and institutional disregard for sexual harassment by boys and teachers (Jones Citation2011; Muhanguzi Citation2011; Turner Citation2020). There appears therefore to be a disjuncture between the legislative and policy framework, which regulates against sexual violence by teachers, and practices at school level, where sexual violence by school staff persists, though its prevalence remains unclear.

CoVAC study methods

The analysis for this paper was conducted as part of a broader research project: Contexts of Violence in Adolescence Cohort Study (CoVAC) (2018–2023). CoVAC is a research collaboration led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), UCL Institute of Education (IoE) and the Ugandan NGO, Raising Voices, in partnership with the Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI). CoVAC is a mixed methodology longitudinal cohort study that aims to build understanding on how family, peer, school and community contexts affect young people’s experiences of violence in adolescence and early adulthood. Young people from 42 primary schools in Luwero District, Uganda were invited to participate in 2014 following a school-wide violence prevention intervention. More information about CoVAC’s study design and ethics protocol is available elsewhere (Devries et al. Citation2020). Briefly, quantitative data were collected at three time points (2014, 2018, 2021/2022). 3820 young people participated in the first wave of data collection in 2014, and 2773 of these young people (1445 girls and 1328 boys) participated in the wave 2 face to face survey in 2018. In this paper, we analyse data collected at wave 2. We describe the prevalence of teacher sexual violence overall, and then explore if, and how, teacher sexual violence varied by age, poverty, disability, and connectedness to caregivers, peers, and teachers. We then investigate how teacher sexual violence varied by the primary school the participant attended in 2014, describing the percentage of girls reporting sexual violence grouped by their primary school and then exploring how much of the variation in sexual violence at wave 2 was attributable to the primary schools girls attended. Analyses were conducted using the statistical software package, Stata 16. Qualitative data were collected for 2–3 months each year from 2018 to 2022, with 36 core participants (18 female, 18 male), aged 15–17 (in 2018), and with their teachers, caregivers, peers, and other stakeholders. The young people have engaged in a series of biographical narrative interviews, focus groups, community walks and unstructured discussions with their ‘key’ researchers, with whom they have built strong research relationships through multiple encounters. After each period of fieldwork, data were translated (from Luganda to English), transcribed, with pseudonyms, coded thematically using NVivo, and with biographical narratives co-constructed over time for each participant.

Dialogical analysis

The analysis for this paper began with discussions between the quantitative and qualitative research teams on preliminary analyses of 2018 data from young people on sexual violence. Our research team is interdisciplinary, combining the fields of public health, gender and education, and violence prevention practice, and from research and practice institutions in Uganda and the UK. Recognising both the power and the limitations of the positionality of some team members within knowledge systems of the global north, throughout the research there has been an emphasis on dialogue and processes of learning across the project teams, as we attempt to understand the multiple dimensions of violence, how acts of violence are linked to gendered identities, and embedded within larger structures of power and intersecting inequalities.

Reflecting on the immense difficulties of translating meanings of ‘gender’ across different spaces of education theory, policy and practice, Unterhalter (Citation2009) argued that processes of dialogue between different positionings are possible, through ‘transversal dialogue’. Drawing on Yuval-Davies’ writing on transversal politics (Yuval-Davis Citation2006) and Sen’s work on dialogue and justice (Sen Citation2012), she identifies three steps to support mobility of ideas. The first step is rooting, which entails reflective knowledge of one’s own positionality and identity. Reflexivity has become increasingly central in comparative education debates on decolonising research and the implications of ‘foreignness’ of researchers, from the contexts in which they work (Kim Citation2020). Within this paper, we are also concerned with positionality within particular research traditions and methodologies. The second step is shifting, which involves recognising and respecting other positions, and acknowledging vertical and horizontal differences in social, economic and political power, including within research processes. The third step is the practical evaluation of what may make one approach better than another. Dialogic approaches have also been advocated in writing on mixed methods, where too researchers seek pragmatic ways to bring together seemingly incommensurate ways of understanding complex social phenomena. While for some the different world views associated with positivist and interpretivist research make the approaches irreconcilable, others argue for integration through mixed methods (Fetters and Molina-Azorin Citation2017). In relation to educational research, Greene (Citation2005) argues:

A mixed method way of thinking seeks not so much convergence as insight; the point is not a wellfitting model or curve but rather the generation of important understandings and discernments through the juxtaposition of different lenses, perspectives, and stances; in a good mixed methods study, difference is constitutive and fundamentally generative. (208)

Fetters and Molina-Azorin (Citation2017) trace how mixing methods can take place at all stages of research. Here we focus on the interpretation of data from qualitative and quantitative strands, to the fit or coherence between these. Comparing data can be confirmatory, when qualitative and quantitative findings seem to point to similar conclusions; or complementary, telling different but non-contradictory stories; or expansive, through layering or overlapping understanding; or it can be discordant, when data conflict with each other (Fetters and Molina-Azorin Citation2017). Discordance may lead to digging further through re-analysing, explaining using theory, collecting more data, and through reflexive questioning on rigour. Though we present our data as separate quantitative and qualitative blocks, the process of analysing and interpreting has been dialogical, involving multiple discussions within and between the research teams. Each stage of the analysis required ‘translations’ of the different languages associated with quantitative and qualitative, positivist and interpretive research paradigms, as we discuss further below. First, however, we present synthesised findings of the quantitative and then the qualitative data.

Quantitative data on teacher sexual violence

The quantitative survey asked about specific acts of violence from a teacher. Young people were asked whether they experienced any of the following from a teacher ever, in the past week, and in the past year: sexual comments about their breasts, genitals, buttocks; sexual touching; money to do sexual things; threats or pressure to have sex or do sexual things; forced sex. Overall, 4.9% (41 of 844) girls who were in school at wave 2 had experienced lifetime sexual violence from a teacher and 4.2% (35 out of 844) reported experiencing teacher sexual violence in the past year. Among girls in school, the overall prevalence of sexual violence from any perpetrator was 23.8% (201 of 844 girls) compared to 14.3% (87 out of 681) among boys. Girls who had experienced lifetime sexual violence reported peers (16.0%), partners (6.3%), and then teachers as perpetrators. Fewer than 2% of girls reported caregiver (1.8%) or employer (1.4%) sexual violence. Among boys, 1.8% (12 out of 681) reported lifetime and past year sexual violence from a teacher, and 14.2% (97/681) reported lifetime sexual violence from any perpetrator. Boys reported sexual violence from partners (7.9%) and peers (5.9%) most often, followed by teachers. Less than 1% of boys reported sexual violence from a caregiver (0.4%) or employer (0.9%).

Among girls who experienced lifetime teacher sexual violence, 36/41 (87.8%) were aged 13–18 years in wave 2, 38/41 (92.7%) were in households in the highest two asset clusters, and 26/41 (63.4%) reported no difficulties. shows that a greater proportion of older adolescent girls and young women had experienced lifetime teacher sexual violence compared to the younger age group (9.6% vs 4.6%) and that a greater proportion of girls with low peer connectedness had experienced lifetime sexual violence compared to the high peer connectedness group (6.2% vs 3.8%), however these associations were not statistically significant. Levels of asset ownership, a measure of socio-economic status, was not associated with teacher sexual violence victimisation among girls who were in school. We observed some evidence for an unadjusted association between disability and lifetime sexual violence: among girls in school at wave 2, having a disability was associated with higher odds of teacher sexual violence and among girls with disabilities, 16% (5/41) experienced teacher sexual violence. Finally, we found evidence for an unadjusted association between lifetime sexual violence and both low school and low family connectedness

Table 1. Sexual violence among girls in school at wave 2: overall prevalence and by girls’ characteristics.

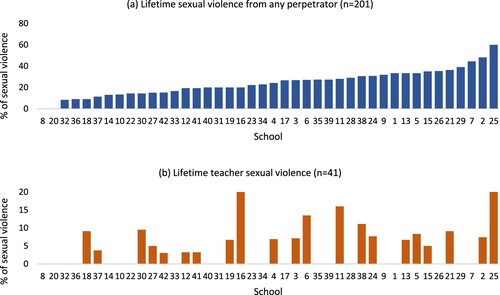

Variability between schools in teacher sexual violence has received surprisingly little research attention, given its potential for generating insights into how institutions can prevent and protect from violence. shows the percentage of girls who reported lifetime sexual violence at wave 2 in 2018 from (a) any perpetrator (b) from teachers, grouped by the primary school of the participant in 2014. The quantitative data does not include data on the secondary schools of participants so we grouped participants by the primary school they were attending at wave 1, to explore the role of primary school contexts. At wave 2, girls from 40 out of 42 wave 1 primary schools reported sexual violence from any perpetrator which ranged from 8.3% to 48.2%. At wave 2, girls from 21 out of 42 primary schools, reported experiencing teacher sexual violence either in their primary school or in any other subsequent school, which ranged from 3% to 30%.

Figure 1. Lifetime sexual violence and teacher sexual violence among girls in school at wave 2 by primary school.

Figure shows (a) lifetime sexual violence from any perpetrator and (b) lifetime teacher sexual violence at wave 2 grouped by participant's primary school at wave 1. We also specified a null two-level random intercepts model with participants nested in schools to calculate the Variance Partition Coefficient (VPC). The VPC was 2.3% for lifetime sexual violence and 7.4% for lifetime teacher sexual violence.

With regard to how school contexts affect sexual violence, among girls who were in school in Wave 2, we found that 2.3% of the variation in lifetime sexual violence from any perpetrator was due to between school variation in the primary schools of participants, and 7.4% of variation in lifetime teacher sexual violence is due to between primary school variation. Primary school environments and contexts may not have a bearing on lifetime experiences of sexual violence from ‘any perpetrator’ (employers, caregivers, partners, peers, teachers) as many of these experiences of violence occur outside of school. However, primary schools do matter for lifetime teacher sexual violence. They appear to make a difference to girls’ experiencing teacher sexual violence not only when they are at primary school, but also afterwards when they are in secondary schools. Further research is needed, however, to understand how institutional processes at primary level are having a bearing on girls’ safety in the next phase of their education. Although our analysis is descriptive and does not adjust for any confounding variables, this finding further affirms the importance of changing school environments, including early in life, to prevent teacher violence and of opportunities for institutional action at the school level.

Qualitative data on sexual exploitation by teachers

Instead of asking whether girls had experienced specific acts of violence perpetrated by teachers, the qualitative discussions focused more on the contexts and relationships surrounding violence, with, over time, dialogue with young people about the emerging evidence, including their perspectives on data on sex between teachers and pupils from previous rounds of fieldwork. Our qualitative data suggested that sexual exploitation of girls by teachers was both more commonplace and took more varying forms than reported in the quantitative data. Though none of our 18 female core participants reported having sex with teachers themselves, some narrated their personal experiences of repudiating teachers’ sexual advances, and many reported incidents disclosed to them by friends. Discourses around gender, sexuality, age and authority could be deployed by male teachers in ways that were sexually exploitative and that constrained girls’ freedoms to refuse sexual advances, as narrated by Otim (age 16) in discussion with her key researcher, Rehema:

What challenges have you encountered at school?

The challenge I am seeing comes from the teachers mostly the male teachers. He can approach you seeking for an intimate relationship with you and when you turn down his offer, he can start under marking you with the aim of failing you. He does that so that you can fall into his trap and he gives you good marks.

Has such a thing ever happened to you?

Yes, it has happened to me recently when I was in S.3 and it was the computer teacher who was seeking for an intimate relationship with me. We 10 students in total who were doing his subject of only 1 was a boy the rest of were girls. I used to perform so well in his subject as I was always in the 2nd position. So he one time in class asked me about my family details, he then offered to pay my school fees but I told him I had a sponsor. He then offered to buy me all the scholastic materials I need but I told him my mother was able to provide for me, he told me that he wanted to support my education and after school he makes me his wife. When I gave him no for an answer, he gave me zero in his subject at the BOT [Beginning of Term] exams.

Hmmmm

I took my complaint to this teacher that I wasn’t satisfied with the marks and he told me that he will continue to give me these marks until I accept his offer. He told me he was willing to wait until I finish my O level then we go for marriage, when I threaten to report him to relevant authority.

Whenever he would give an assignment as a class and I happened to fail even just a single number, he would jealously beat me. There are times I would score 60% and he would beat me more than even those who scored the worst.

There is a girl who brought her art course work for submission because it is a requirement for us to do Art coursework before the actual final O level exams. So this girl brought her coursework for submission late and when she greeted the teacher he demanded that she first gives him a hug, to which the girl refused. This teacher told her that he won’t receive her coursework until she hugs and kisses him. He said that to her knowing that she will give in because if he doesn’t submit her coursework this means that she would get X grade in Art subject and this simply means one has to repeat S.4.

The other time that very old man asked a girl to come with him to the Geography room and he give her past examination papers for revision. The girl followed him because towards exams such papers are very helpful to prepare ourselves for final exams. On reaching this room, this teacher locked it and asked her to first give in to having sex with him for him to give her these past papers.

As well as illustrating the abuse of institutional authority by these teachers, these examples show how difficult it can be for girls to refuse teachers’ advances. The material benefits are significant, in a context where many young people are compelled to drop out because of the costs of schooling and the requirement to repeat school years if achieving low grades in examinations. In contrast to the quantitative data, the qualitative data more clearly signalled that risks of exploitation could be amplified for girls with fewer economic resources. The deference expected of girls towards authority figures makes it difficult to say no, and when they did refuse consent, they could be punished with beatings or unfair grades.

While mostly girls were repelled by teachers’ sexual advances, occasionally they spoke of attraction, particularly to young male teachers. Apio (age 15), for example, was critical of the school authorities for employing an attractive, young male doctor, now rumoured to be in a sexual relationship with a female pupil at the school:

It is even their fault that they employed such a youth to work in a secondary school. These girls in my school get so excited when they see a young handsome man passing by. Even when they see him when it is classroom or during chapel, they all get disorganized.

He can’t chase you out over the reason of a girl, he will find other minor reasons like he can ask you why you haven’t written the date on your work for that day and chases you out of class and he causes you to miss classes or he can wait at the end of the lesson and say such a student told me this and that and because he is among fellow teachers you as a student can’t go on defending yourself to every teacher. He can say you are undisciplined and you are sent home for like two weeks suspension but all that originates over a girl if he suspects you like a girl that he also likes.

While the qualitative data suggest widespread sexually exploitative practices by male teachers, variations between school institutions identified in the quantitative data were also evident in the qualitative data. Despite the coercive practices deployed by teachers to ensure girls’ silence, girls told researchers how they refused or evaded teachers’ advances, with varying levels of institutional support and redress. Otim resisted directly by threatening to report the teacher:

I would first report to the school head, then to my parents and finally to police. But he pleaded with me not to and I also warned him not to bother me again, this teacher hated me until I left that school.

He told me that if I date him I will not need to work so hard to score high in his subject. I fooled him that I was accepting all that he was telling me but I wasn’t taking it at heart.

This teacher was seriously warned against that and they threatened to fire him from his job. It was later discovered that he had dated so many children in school, there are even twins he was dating at the same time, he even used to keep us in class until late in the evening just because he wanted to escort some female students back to their homes and he could take advantage of them.

In other cases, there were institutional mechanisms in place, but not functioning effectively. For example, in Cathy’s school, though she is aware of teachers at the school who have sex with pupils and punish girls if they refuse sex, girls do not report cases to the disciplinary committee:

I have not heard of any student who has come up to report such cases in our school. The best thing these girls do, they just seek for advice from their friends who in most cases advise them not to give such teachers an ear

What do you think about that whole thing of teachers dating their students?

It is a very bad thing and if possible I would like such teachers to be handled in the disciplinary committee but it is so sad these girls they approach don’t come out to report

There were, however, schools where more effective actions were taken. Ruth, for example, explained that a teacher’s practice of ‘caressing students’ stopped after girls reported:

They wrote notes and dropped them in the suggestion box. This box is opened so often, so when this issue was brought to the attention of the school admin then it was handled.

Is there anything in particular that was done to the teacher?

I don’t know what exactly was done to him but I think they sat him down or if they warned him against repeating this very mistake. But for us as students we noticed a change in his conduct since the issue was raised in the suggestion box.

Reflections on quantitative and qualitative data through a dialogical analysis

The process of analysis that generated the quantitative and qualitative findings we have presented has involved multiple translations, between research participants and researchers, and between qualitative and quantitative researchers with differing world views, methodologies and methods. Our preliminary comparisons of the quantitative and qualitative data indicated both confirmatory and discordant findings. While both data sources revealed commonplace experiences of sexual violence, the prevalence data showed that most commonly this was perpetrated by peers or intimate partners. In the qualitative data, however, girls much more frequently raised concerns about sexual exploitation by teachers, with accounts that were so recurrent that we began to suspect that some sexually exploitative practices by school staff were not being picked up in the survey. Dialogical analysis requires reflexivity on our positionality, and recognising and respecting other positions, while recognising the power they carry. Across the research, we have conceptualised gender violence as multi-dimensional, with acts of violence linked to gendered identities, embedded within larger structures of power and intersecting inequalities (Merry Citation2009). Acculturated in the world views of our scholarly communities, for those with epidemiological roots core questions concern how to get the most accurate data on prevalence of violence, while those of us with interpretive roots are more concerned with the subjective meanings and contextual dynamics surrounding violence. The divergence in the datasets we have presented can be accounted for partly by the different questions asked, with the quantitative questions focusing on acts of violence, while the qualitative accounts were about feelings, situations and relationships.

The headline figure, that 4.9% of schoolgirls experienced sexual violence by a teacher, bears the power of numbers that may have most weight for policy makers. The dialogue within the research team, and interrogation of the qualitative and quantitative data, reinforced our suspicions that these figures, though shocking, are likely to under-estimate prevalence. The qualitative data remind us that there may be stigma and shame in speaking about such experiences, or girls may fear repercussions of the coercive practices they have described. Quantitative questions about violence may not capture sex with teachers that is perceived as consensual, nor the sexualised atmosphere fostered by some teachers, which creates the conditions for sexual harassment to be normalised in school spaces. Quantitative data also do not capture experiences that participants witness or the experiences of their friends. However, the qualitative findings reveal that girls are discussing their own experiences, their role in supporting friends, and experiences they have seen or heard about in their schools more broadly.

The dialogue on these headline figures also generated questions about the integrity of our interpretation of the qualitative data, and the power of the quote. Young people’s narratives about violence evoke emotional responses, and in research just as in media reports there may be a tendency to focus on extreme examples, to over-infer about the normalisation of violence, and to over-claim what can be drawn from qualitative data. It is also important to recognise the silences in qualitative data. While sustained relationships with familiar researchers, open-ended questions and flexible research instruments may help to facilitate discussion on sensitive topics and erode some of the power imbalances in research relationships, they also enable young people to choose not to disclose experiences of violence. The taboos, threats and secrecy surrounding teacher sexual violence help to explain why girls and boys may prefer not to admit to such experiences in both surveys and informal research discussions.

There were two further pivotal moments in the analysis, both stemming from these processes of reflexivity and dialogue on the veracity of our data sources. The first began with reflections on the intersecting discourses around gender, sexuality, age, socio-economic status and authority that suffused the qualitative data on sexual exploitation in schools. This prompted further analysis of quantitative data on intersecting vulnerabilities, generating illuminating findings on how disability, school connectedness and family connectedness intersect with gender in increasing risk of teacher sexual violence – dimensions that are missing from other studies on teacher sexual violence. The other pivotal moment emerged from the finding on school connectedness, that most girls who experienced teacher sexual violence also reported low school connectedness. Experiencing teacher sexual violence could affect and reduce feelings of connnectedness to school. And, at the same time, in schools where girls feel a sense of belonging and safety they may be less likely to experience teacher sexual violence. Our analysis does not allow us to untangle the directionality of this link, raising important questions for future research. This finding prompted further quantitative and qualitative analysis of variations between schools, including the interesting quantitative finding that primary school environments could make a difference to teacher sexual violence several years later, when the girls have moved to secondary schools. The qualitative data reveal girls’ resourcefulness in the actions they take to protect themselves, and marked variability in institutional processes that hold school staff accountable. While our data suggest that in some schools, laws and policies are being translated into the institutional cultures, more fine-grained analyses of the processes entailed are needed.

Transversal dialogue, recognising the complexities of translating between different perspectives on gender, education and violence, stresses reflexivity and respect for other positions (Unterhalter Citation2009), and mixed methods researchers also stress the importance of toleration and respect (Greene Citation2012). To these we add humility, recognising the limits of our positionality and our tools in understanding silences around sexual violence and exploitation by school staff of girls.

Conclusion

Although the impetus to address violence in schools through policies and practice has grown, we have shown how sexual violence committed by teachers is often missing from these interventions, or, when it is included, the interventions are not well served by the existing research base. There are many ethical and methodological challenges in researching a topic that is shrouded in secrecy, shame, stigma and coercion, and, we have argued, privileging narrow research designs, such as reliance only on survey data, has contributed to the gaps in knowledge. Through a dialogical analysis of quantitative and qualitative data from a longitudinal study in central Uganda, a fuller picture emerges of girls’ experiences, patterns of discrimination and inequality that increase vulnerabilities, and varying institutional responses.

Echoing other studies from Uganda (Muhanguzi Citation2011; Turner Citation2020), our findings reveal disconnects between policies and practices of sexual exploitation in schools. They show that many girls endure sexual exploitation by school staff, with discourses around gender, sexuality, age and authority deployed by male teachers to coerce girls for sex, and constraining girls’ freedoms to refuse these sexual advances. Risks of exploitation are particularly high for girls who have disabilities, or who have fewer economic resources, including struggling to pay schooling costs, while supportive family relationships may be protective. With a lack of institutional support, girls rely on their own resourcefulness, and their informal social networks, to deter sexual violence, facing risks of further punishment for their refusals to submit. However, there are variations between schools, with some schools developing systems to encourage reporting and to hold staff accountable. More broadly, our findings suggest that a sense of belongingness and connectedness in school may be protective, though further research is needed to look more closely at the processes entailed. Though the extent of sexually exploitative practices is deeply concerning, that some schools are taking steps to tackle this provides a foundation for dialogues coordinated by Raising Voices, with school staff and policy actors in the next phase of the research.

Mixed methods research is immensely challenging, and our analysis shows how whatever methods are used, some sexual violence by school staff will remain hidden; young people will feel constrained or choose not to speak about their experiences. However, when mixed methods research designs build in dialogical analyses they have, we suggest, rich potential for research on gender violence, where the scope for misunderstanding is amplified by secrecy, coercion, deception, contestation, power imbalances and abuses. These dialogues entail reflexivity with humility on our knowledge systems, and our ties to particular methodological systems, alongside respect for other positions. Longitudinal research designs are particularly valuable, as setting multiple methods in dialogue with each other helps to avoid reifying particular forms of knowledge, and they allow time and flexibility to reflect on silences and disclosures, and to refine and shift their methods and questions as the dialogues unfold.

Our analysis has focused on dialogues with young people, notably how to learn from them about sexual violence committed by teachers. A challenge for policy and practice remains how to ensure that schools are indeed ‘safe spaces’, where sexual violence in its multiple guises is not tolerated. A key area for dialogue moving forward will be working with teachers, to help fill knowledge gaps concerning changes and continuities in practices of teacher sexual violence over time, how these relate to legislative and policy developments, and to professional identities, institutional cultures, work conditions, and gender discourses in schools and communities. Relationships built up over time between violence prevention practitioners and teachers may help to erode some of the barriers to speaking out that have stymied research with teachers on this topic. Our findings affirm the importance of engaging with young people and of building opportunities for institutional action at the level of the school, including early in life, to prevent these forms of violence. While global policy concerns with girls’ education have increasingly recognised the need to tackle gender-based violence, these efforts, we argue, have not paid enough attention to teacher sexual violence. Tackling sexual exploitation of girls in schools requires multiple dialogues, building connections between differently positioned research, policy and practice partners, acknowledging and valuing the knowledges they bring, to support work in schools that disrupts the silencing of girls’ voices and tackles sexual violence and exploitation in school spaces.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of Junior Brian Musenze and Joan Ritar Kasidi, talented researchers formerly at MRC/UVRI Uganda. We would also like to thank Janet Nakuti, Tvisha Nevatia, and Angel Mirembe, at Raising Voices. The research was funded by the Medical Research Council, grant number: MR/R002827/1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jenny Parkes

Jenny Parkes is Professor in Education, Gender and International Development at UCL Institute of Education, and leads the qualitative longitudinal component of the Contexts of Violence in Adolescence Cohort Study. Her research interests include violence, gender, and intersecting inequalities affecting young people's lives, and the role of education.

Amiya Bhatia

Amiya Bhatia is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Global Health and Development at the LSHTM. Amiya is a social epidemiologist and mixed methods researcher. Her work examines social inequalities in violence against children, birth registration, child labour and child marriage. She is also interested in biases and blindspots in violence data, and how global and local organisations collect and use data on violence.

Simone Datzberger

Simone Datzberger is a Lecturer in Education and International Development at UCL Institute of Education. She is a political scientist by training, engaging in multi-disciplinary research projects and collaborations combining the fields of international development, education, political science, peace and conflict studies, and recently also public health. Since 2018 her research mainly focuses on violence against children and youth from an interdisciplinary angle. She has conducted extensive field research in Sierra Leone and Uganda.

Rehema Nagawa

Rehema Nagawa is Research Assistant at the Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute. Her research interests include gender, violence, child participation and inclusion. She has worked with other organizations like RHSP and Plan International on studies with young people in different districts of Uganda.

Dipak Naker

Dipak Naker is Co-Founder of Raising Voices and of the Coalition For Good Schools. He has worked in East Africa for more than twenty years and has developed award winning, evidence-based interventions to prevent violence against children.

Karen Devries

Karen Devries is a Professor of Social Epidemiology at the LSHTM, and leads the Child Protection Research Group. She applies epidemiological and mixed methods to the study of violence prevention. Currently, she partners with colleagues in Uganda, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and Cote d'Ivoire to develop and test interventions to reduce violence against children, and to explore the causes and consequences of violence.

References

- Abramsky, T., K. Devries, L. Kiss, J. Nakuti, N. Kyegombe, E. Starmann, B. Cundill, et al. 2014. “Findings from the SASA! Study: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess the Impact of a Community Mobilization Intervention to Prevent Violence Against Women and Reduce HIV Risk in Kampala, Uganda.” BMC Medicine 12: 122. doi:10.1186/s12916-014-0122-5.

- Altinyelken, Hülya Kosar, and Marielle Le Mat. 2018. “Sexual Violence, Schooling and Silence: Teacher Narratives from a Secondary School in Ethiopia.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 48 (4): 648–664.

- Bell, Stephen A. 2012. “Young People and Sexual Agency in Rural Uganda.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 14 (3): 283–296.

- Bhana, Deevia. 2012. ““Girls are not free”—In and Out of the South African School.” International Journal of Educational Development 32 (2): 352–358.

- Chikwiri, E., and E. M. Lemmer. 2014. “Gender-based Violence in Primary Schools in the Harare and Marondera Districts of Zimbabwe.” Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology 5 (1): 95–107.

- Chilisa, Bagele, and Gabo Ntseane. 2010. “Resisting Dominant Discourses: Implications of Indigenous, African Feminist Theory and Methods for Gender and Education Research.” Gender & Education 22 (6): 617–632.

- Devries, K. M., L. Knight, J. C. Child, A. Mirembe, J. Nakuti, R. Jones, J. Sturgess, et al. 2015. “The Good School Toolkit for Reducing Physical Violence from School Staff to Primary School Students: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial in Uganda.” The Lancet Global Health 3 (7): e378–e386. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00060-1.

- Devries, K., J. Parkes, L. Knight, E. Allen, S. Namy, S. Datzberger, W. Nalukenge, et al. 2020. “Context of Violence in Adolescence Cohort (CoVAC) Study: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Longitudinal Study in Uganda.” BMC Public Health 20 (1): 43. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7654-8.

- Dunne, Máiréad. 2007. “Gender, Sexuality and Schooling: Everyday Life in Junior Secondary Schools in Botswana and Ghana.” International Journal of Educational Development 27 (5): 499–511.

- Fetters, Michael D, and José F Molina-Azorin. 2017. “The Journal of Mixed Methods Research Starts a New Decade: The Mixed Methods Research Integration Trilogy and its Dimensions.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 11 (3): 291–307.

- George, Erika. 2001. Scared at School: Sexual Violence Against Girls in South African Schools. New York: Human Rights Watch.

- Government of Uganda. 2012. “Education Service (Teachers’ Professional Code of Conduct), Legal Notices Supplement to The Uganda Gazette No. 47 Volume CV dated 24 August 2012.” Accessed 13 October 2022. https://www.esc.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Legal-notices-supplement-2012.pdf

- Government of Uganda. 2016. “The Children (Amendment) Act, 2016.” Accessed 13 October 2022. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/104395/127307/F-171961747/UGA104395.pdf

- Greene, Jennifer C. 2005. “The Generative Potential of Mixed Methods Inquiry.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 28 (2): 207–211.

- Greene, Jennifer C. 2012. “Engaging Critical Issues in Social Inquiry by Mixing Methods.” American Behavioral Scientist 56 (6): 755–773.

- Hendriks, Tanja D, Ria Reis, Marketa Sostakova, and Lidewyde H Berckmoes. 2020. “Violence and Vulnerability: Children’s Strategies and the Logic of Violence in Burundi.” Children & Society 34 (1): 31–45.

- Hussain, Nasir, Sheila Sprague, Kim Madden, Farrah Naz Hussain, Bharadwaj Pindiprolu, and Mohit Bhandari. 2015. “A Comparison of the Types of Screening Tool Administration Methods Used for the Detection of Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 16 (1): 60–69.

- Jewkes, Rachel, Jonathan Levin, Nolwazi Mbananga, and Debbie Bradshaw. 2002. “Rape of Girls in South Africa.” The Lancet 359 (9303): 319–320.

- Jones, Shelley Kathleen. 2011. “Girls’ Secondary Education in Uganda: Assessing Policy Within the Women's Empowerment Framework.” Gender & Education 23 (4): 385–413.

- Kerr-Wilson, A., A. Gibbs, E. McAslan Fraser, L. Ramsoomar, A. Parke, H. M. A. Khuwaja, and R. Jewkes. 2020. “A Rigorous Global Evidence Review of Interventions to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls.” What Works to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls Programme. Pretoria, South Africa.

- Kim, Terri. 2020. “Biographies of Comparative Education: Knowledge and Identity on the Move.” Comparative Education 56 (1): 1–2.

- Kyegombe, N., R. Meiksin, S. Namakula, J. Mulindwa, R. Muhumuza, J. Wamoyi, L. Heise, and A. M. Buller. 2020. “Community Perspectives on the Extent to Which Transactional sex is Viewed as Sexual Exploitation in Central Uganda.” BMC International Health & Human Rights 20 (1): 1–16.

- Langford, Rebecca, Christopher Bonell, Hayley Jones, Theodora Pouliou, Simon Murphy, Elizabeth Waters, Kelli Komro, Lisa Gibbs, Daniel Magnus, and Rona Campbell. 2015. “The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools Framework: A Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMC Public Health 15 (1): 1–15.

- Leach, Fiona, Máiréad Dunne, and Francesca Salvi. 2014. School-Related Gender-Based Violence: A Global Review of Current Issues and Approaches in Policy, Programming and Implementation Responses to School-Related Gender-Based Violence (SRGBV) for the Education Sector. Paris: UNESCO.

- Leach, Fiona, Vivian Fiscian, Esme Kadzamira, Eve Lemani, and Pamela Machakanja. 2003. “An Investigative Study of the Abuse of Girls in African Schools.” Education Research Report No. 54. London: DfID.

- Leach, Fiona, and Sara Humphreys. 2007. “Gender Violence in Schools: Taking the ‘Girls-as-Victims’ Discourse Forward.” Gender & Development 15 (1): 51–65.

- Merry, Sally Engle. 2009. Gender Violence: A Cultural Perspective. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Mirembe, Robina, and Lynn Davies. 2001. “Is Schooling a Risk? Gender, Power Relations, and School Culture in Uganda.” Gender & Education 13 (4): 401–416.

- Mirsky, Judith. 2003. Beyond Victims and Villains: Addressing Sexual Violence in the Education Sector. London: Panos Institute.

- MoESTS Uganda. 2015. “National Strategic Plan on Violence Against Children in Schools [2015 - 2020].” Kampala. Accessed 19 January 2022. https://eprcug.org/children/publications/health/protection-and-participation/violence-against-children/national-strategic-plan-on-violence-against-children-in-schools-2015-2020

- Moletsane, Relebohile, Claudia Mitchell, and Thandi Lewin. 2015. “Gender Violence, Teenage Pregnancy and Gender Equity Policy in South Africa.” In Gender Violence in Poverty Contexts: The Educational Challenge, edited by Jenny Parkes, 183–196. London: Routledge.

- Muhanguzi, Florence Kyoheirwe. 2011. “Gender and Sexual Vulnerability of Young Women in Africa: Experiences of Young Girls in Secondary Schools in Uganda.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 13 (06): 713–725.

- Ninsiima, Anna B, Els Leye, Kristien Michielsen, Elizabeth Kemigisha, Viola N Nyakato, and Gily Coene. 2018. “Girls Have More Challenges; They Need to be Locked up”: A Qualitative Study of Gender Norms and the Sexuality of Young Adolescents in Uganda.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (2): 193.

- Nyanzi, Stella, Robert Pool, and John J Kinsman. 2001. “The Negotiation of Sexual Relationships among School Pupils in South-Western Uganda.” AIDS Care 13 (1): 83–98.

- Reilly, Anita. 2014. “Adolescent Girls’ Experiences of Violence in School in Sierra Leone and the Challenges to Sustainable Change.” Gender & Development 22 (1): 13–29.

- Sen, Amartya. 2012. The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and Identity. London: Penguin Books.

- Steiner, Jordan J, Laura Johnson, Judy L Postmus, and Rebecca Davis. 2021. “Sexual Violence of Liberian School Age Students: An Investigation of Perpetration, Gender, and Forms of Abuse.” Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 30 (1): 21–40.

- Tanton, C., A. Bhatia, Pearlman, and K. Devries. 2022. “Increasing Disclosure of School-Related Gender-Based Violence: Lessons from a Systematic Review of Data Collection Methods and Existing Survey Research.” [Under review].

- Together for Girls. 2021. “School-related Gender-based Violence Factsheet: Uganda.” Accessed 14 October 2022. https://www.ungei.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/Uganda-fact-sheet-School-Related-Gender-Based-Violence-2020-eng.pdf

- Turner, Ellen. 2020. “Doing and Undoing Gender Violence in schools: An Examination of Gender Violence in Two Primary Schools in Uganda and Approaches for sustainable Prevention.” PhD thesis, University College London.

- UNESCO. 2018. “Connect with Respect: Preventing Gender-Based Violence in Schools: Classroom Programme for Students in Early Secondary School (Ages 11–14).” UNESCO Bangkok. Accessed 14 October 2022. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000243252

- UNESCO and UN Women. 2016. “Global Guidance on Addressing School-Related Gender-Based Violence.” Accessed 14 October 2022. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2016/12/global-guidance-on-addressing-school-related-gender-based-violence

- UNGEI. 2019. “A Whole School Approach to Prevent School-Related Gender-Based Violence: Minimum Standards and Monitoring Framework.” Accessed 14 October 2022. United Nations Girls Education Initiative, New York. https://www.ungei.org/publication/whole-school-approach-prevent-school-related-gender-based-violence-1

- UNICEF. 2014. Hidden in Plain Sight: A Statistical Analysis of Violence Against Children. New York: United Nations Childrens Fund.

- Unterhalter, Elaine. 2009. “Translations and Transversal Dialogues: An Examination of Mobilities Associated with Gender, Education and Global Poverty Reduction.” Comparative Education 45 (3): 329–345.

- WHO. 2016a. Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Intervention Research on Violence Against Women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO. 2016b. “INSPIRE: 7 Strategies for Ending Violence Against Children.” World Health Organisation, Geneva. Accessed 14 October 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/inspire-seven-strategies-for-ending-violence-against-children

- WHO. 2019. “RESPECT: 7 Strategies to Prevent Violence Against Women.” World Health Organisation, Geneva. Accessed 14 October 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-19.11

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2006. “Human/Women’s Rights and Feminist Transversal Politics.” In Global Feminism: Transnational Women’s Activism, Organizing, and Human Rights, edited by Myra Myra Marx Ferree, and Aili Mari Tripp, 275–295. New York: New York University Press.