ABSTRACT

Promising lines of scholarship have emerged on how International Organisations (IO’s) deploy anticipatory techniques aimed at colonising the future as a means of governing in the absence of sovereignty. It follows that securing hegemony over a vision of the future is important strategic work for IOs, and a source of legitimacy derived from authority beyond procedure and performance. This is called promissory legitimacy. Yet what happens when this promised future arrives and is problematic? How does an IO creatively strategise this shortfall? In this paper, we identify five strategies deployed by the OECD in its Future of Education and Skills 2030 programme aimed to re-negotiate a failed present and anticipate a new future. We also reflect on the ideational underpinnings of the OECD’s new futures programme, and argue it is being mobilised to, on the one hand, get beyond the limitations of data governance, and on the other to help selectively shape a new cognitariat subjectivity engaged with immaterial labour in emerging post-industrial capitalism.

1. Introduction

The English idiom and the title of our paper – ‘promises promises’ – are saturated with futurity and incredulity. It simultaneously faces the future whilst seeding a moment of doubt that this promise might actually not materialise. This paper engages with recent scholarship on how International organisations (IOs) deploy anticipatory techniques aimed at governing the future (Berten and Kranke Citation2022; Robertson Citation2022), focusing specifically on the relationship between promised futures and legitimacy to govern. We engage with Beckert’s (Citation2020) concept of ‘promissory legitimacy’. That is, it can only be promissory in that any expectation about the future is at best a ‘fictional expectation’ (Beckert Citation2016). But what happens when this promise is not what eventually emerges? How is the inconvenient truth managed? This matters for IOs, as their authority is dependent upon promissory legitimacy. Any shortfall is a cause of major concern triggering new strategies for re-narrating and re-negotiating the failed present and reimagining a new future.

In this paper, we examine how one IO, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD), strategically dances between promises, futurity, and credibility to ensure ongoing authority and legitimacy. We focus specifically on the OECD’s programme launched in 2015; the Future of Education and Skills 2030 (OECD Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Briefly, the OECD argues a ‘new normal’ is emerging because of the ‘evolving’ world of work, and that new values are being prioritised by societies (Berger and Frey Citation2017; OECD Citation2020). As a result, education systems are said to be ‘evolving’ in response to these changes. These shifts are used to legitimate a new agenda for the OECD that appears to radically depart from the one the OECD has not only engaged with for almost three decades but has, until recently, enabled it to dominate what is described as the global governing complex in education (Sorensen, Ydesen, and Robertson Citation2021).

Theoretically, we focus on the anticipatory governing practices, instruments of imagination, and ideational power of the OECD. We link these to changes in the nature of production and social reproduction, drawing on work charting transformations in contemporary capitalism and society, and its implications for education and work (cf. Balibar Citation2019; Berardi Citation2009; Davies Citation2018; Dorahy Citation2022). Methodologically, we examine the comprehensive body of publicly available resources on the OECD’s website as part of its Future of Education and Skills 2030 programme (see ). We use critical discourse analysis (Fairclough Citation2013) as a broad approach aimed at understanding ideational power.

Table 1. Data sources: OECD The Future of Education and Skills 2030.

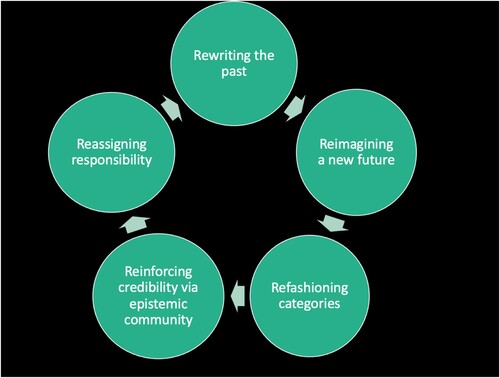

The structure of the paper is as follows. We begin by discussing the idea of the future, fictional expectations, and instruments of imagination aimed at shaping anticipations of the future. Second, we reflect on potential problems of legitimation that have arisen more recently for the OECD when their imagined future brings inconvenient truths. Third, we distil five strategies deployed by the OECD in its portfolio of documents to manage its legitimation shortfall: (i) the systematic rewriting of a once future, then present and now past, to erase the link to the OECD as an implicated subject; (ii) a reimagined new future presented as having its own teleology whilst at the same time now needing to be navigated by the student; (iii) the refashioning of key discursive categories, such as ‘students’, ‘education’ and ‘the future’ so that newer concepts like ‘student agency’, ‘well-being’ and ‘reflexivity’ now dominate, making less visible, but not erasing, older concepts like human capital and skills; (iv) reinforcing its imagined future via narratives from an extensive epistemic community; and (v) reassigning responsibility for the potential failure of unrealised promises to the student, in turn creating a distance between the OECD as the architect of imagination and the future. In our conclusion, we reflect on how best to understand these strategies, as efforts to constitute new sets of social relations in the context of contemporary capitalism.

2. The future, fictional expectations, and instruments of imagination

Studying the future and its power to shape the present is not simple, not least because the future has not yet arrived. Nor do all societies have the same way of understanding the complex relationship between the self, the body, space, and time (cf. Szerszynski Citation2017 for an elaboration of this latter point). For some societies, the future is ahead; for others, the future is unseen and thus behind.

For Strassheim (Citation2016, 151), theories of time are also always political, not only because of their analytic value but also because temporal frames and framings have important implications for how power, rationality, and collectivity, are related to each other. How time is used to manage debates about futures, along with the ways in which specific futures are imagined, prioritised, materialised, and managed, reveal the ways in which the future is also the object of exploration, calculation, anticipation, and control.

A number of fields and disciplines have opened promising lines of enquiry regarding how best to understand governing the future via anticipatory practices (Berten and Kranke Citation2022). Broadly, anticipation captures the modes and effects of acting in the name of the future; as a concept, it pays attention to how the future is constructed in the present (Alvial-Palavicino Citation2015, 137). In this process, ‘ … expectations – as promises or concerns – play an important role. It is through expectations that promises about the future are produced, shaped and circulated’ (Alvial-Palavicino Citation2015, 139; Beckert Citation2013).

IOs particularly use anticipatory techniques aimed at colonising the future as a means of governing in the absence of sovereignty (cf. Berten and Kranke Citation2022; Robertson Citation2022). Securing hegemony over a vision of the future is important strategic work for IOs, and a source of legitimacy derived from authority beyond procedure and performance (Dellmuth, Scholte, and Tallberg Citation2019; Zürn Citation2018). IOs use a range of instruments of imagination to represent the future they consider best to those they seek to influence. These can include statistical representations of future trends, scenarios, credible narratives by epistemic experts, and foresight activities.

3. Problematic presents and promissory legitimacy

Legitimation is a concept linked to the question of authority to govern. Governments do this as sovereign actors given authority under international law, on the one hand, and electoral politics, on the other (Zürn Citation2018). International organisations may be given authority and accorded legitimacy to act based on the ceding of some national state authority upward, but given their limited sovereignty, they need further political strategies to legitimate their work and negotiate their relevance as they compete with other organisations to influence policies (Berten and Kranke Citation2022). In doing so, they use a range of ‘instruments of imagination’ (Beckert Citation2020), such as indicators and statistics, epistemic experts, and other policy devices.

Beckert (Citation2020) distinguishes between input and output-oriented legitimation (following Scharpf Citation1997) and argues that there is a third form linked to promised futures. He calls this promissory legitimacy. Keynesianism, for example, is dependent on ‘input-oriented’ legitimacy, including financial resources, to support its policy regime (Jessop Citation1999). ‘Output legitimacy’, by way of contrast, refers to the effectiveness of achieving results, an approach to legitimation prominent in neoliberal orders (Hood Citation1991). ‘Promissory legitimacy’ is sought through policies that portend to know the future (e.g. forecasting, probabilistic statistics, trends) (Beckert Citation2020). For example, a common promise in neoliberal informed policymaking is the metaphor of ‘all boats rising’. That quite the opposite has happened undermines the credibility of those organisations who have single-mindedly promoted neoliberal policies. Similarly, public-private-partnerships have been promoted as more efficient and effective in delivering public services, where the risks are shared. That this has not been the case requires ongoing political work to manage appearances, outcomes, and potential legitimation shortfalls (Robertson et al. Citation2012).

The OECD is a particularly interesting IO to examine regarding matters of governing, legitimation, and the future. Elsewhere we have argued the OECD has, over time (beginning in the 1990s), managed to govern education futures relatively effectively, mastering the use of indicators, statistics, and large-scale assessments, and expanding the range of assessment programmes and including a growing number of countries (Robertson Citation2022; Sorensen, Ydesen, and Robertson Citation2021). More recently, it has sought to engage with cultural and social concerns via its PISA global competences framework (Martini and Robertson Citation2022; Robertson Citation2021). This latter initiative has been a response to deepening social inequalities, a stalling in social mobility, the challenges of mass migration, concerns over economic growth, climate change, authoritarian populism, and rising nationalisms.

Even prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the OECD began to concern itself with growing social inequalities (cf. OECD Citation2008; Citation2011), rising nationalisms, and authoritarian populism (OECD Citation2016). Acknowledging that income inequality in its member states was at its highest level in the last 50 years, the OECD Secretary General stated: ‘We have reached a tipping point. Inequality can no longer be treated as an afterthought. We need to focus the debate on how the benefits of growth are distributed’.Footnote1

We note that growing social inequalities were particularly evident in those societies who committed themselves to neoliberal policies, under strong policy guidance from the OECD. The figures are startling, as Davies (Citation2018, 76–77) points out:

… research shows that whilst the income of the American people rose by 58% between 1978 and 2015, the income of the bottom half actually fell by 15% over the same period. The gains were clustered heavily among those at the top end of the income distribution: the top 10% of earners experienced a 115% increase over this period, while the top 0.001% saw their incomes rise by an astonishing 685%. The richer one is the faster one’s wealth and income has grown. The practical implication of this data is that half of the American population experienced no form of economic progress in nearly 40 years.

Dig below the surface of the figures and it is evident that national statistics of the kind that the OECD collected and promoted in no way enabled it to ‘read’ the geographic unevenness of more than three decades of neoliberal globalisation and its effects on those increasingly resentful they had been left behind. This outcome ought not to have been a surprise to the OECD because: ‘ … a pure free-market ideology installs social Darwinism as the organising principle of society, resulting inevitably in spiralling inequality … . The strains on physical and mental health of constant competition, and dwindling chances of “winning” become clearer all the time’ (Davies Citation2018, 172). More than three decades of competition, spurred on by large-scale assessments and the global ranking of nation education systems, policies to legitimise outsourcing jobs to cheaper parts of the world, and promises that if you invested in education (buoyed by the knowledge economy and human capital justifications) you would secure a well-paid job, were all called into question (Robertson Citation2021).

Yet the OECD’s policy architecture – its Global Positioning System of statistics, country reports, trends reports, league tables, and policies charting best practices, seemed unable to grasp an emerging zeitgeist that erupted with full force in 2016 with the Brexit vote in the UK, the election of Donald Trump as President in the USA, Erdogan in Turkey, or Bolsonaro in Brazil (to name just a few). This is in part because as Davies argues, ‘ … statistical frameworks had moved even further from lived experiences, as the expert worldview had shifted to even larger scales of government’ (Citation2018, 78). But the OECD had always worked with the national as the main scale through which it has governed statistically, aside from a few occasions when it used a different geographic scale, such as a city (Shanghai) or region (Ontario), or PISA for Schools. Although these latter examples have been unusual.

The dependence on numbers, famously justified by OECD’s chief scientist, Andreas Schleicher in charge of education indicators and statistics with: ‘ … without data you are just another person with an opinion’, had its own flaws as a mode of governing. For one: ‘Numbers allow us to see the world objectively, but the flip side is that they eliminate feeling’ (Davies Citation2018, 71). There was now a palpable air of resentment that was being aired in the ballot boxes across the OECD world and beyond, litmussed in a surge in right wing parties, and the election of authoritarian governments. How had the OECD missed this? ‘Strategic ignorance’ (cf., McGoey Citation2019), or simply an obfuscation that sets in when the tools for governing provide partial information on who and what is being governed? And as Davies elaborates: ‘Statistics might capture who belongs to a category but is far less effective at grasping how intensely they are affected by something’ (Citation2018, 79). The OECD’s ‘data evangelism’ needed to be replaced by another mode of justification.

Some work had already begun on a repair strategy with the launch of the OECD’s PISA Global Competences framework in 2016 (OECD Citation2016), with data gathered in 2018. Global competences, the OECD hoped, would reorient the learner to ‘others’ and their different experiences of, and views on, the world. However, it remained committed to generating measures of competencies and a one-size-fits-all test; a formula that had proven highly successful since its launch in 2000. However, the OECD’s PISA Global Competences Framework had run into difficulties. The national teams had queries about the robustness of the measures, whilst the promised values and beliefs element were dropped in the final test round (Robertson Citation2021). The results were released more than a year later; many countries had not participated, and if they had, only selectively. Many of the indicators were viewed as problematic and the underpinning episteme (Western middle-class culture) was called into question (Auld and Morris Citation2019; Rappleye et al. Citation2020). The shift to working with culture, and the early promise to foreground radical concepts like degrowth, issues of redistribution, climate change, and digital divides, were in the end watered down and discursively realigned with the OECD’s economic mandate (Martini and Robertson Citation2022).

Something more radical than incremental adjustments (Hall Citation1993) to smooth over ongoing legitimation issues was clearly needed. The future had now arrived, and it brought with it inconvenient truths writ large. Its promises needed new narratives for credibility. The future that the OECD had been a key choreographer of and orchestrator for needed to be re-narrated. How it is seeking to do this is addressed in the following section.

4. The OECD – choreographing the ‘New Normal’

In this section, we report on our discursive analysis of the various data sources that constitute the Future of Education and Skills 2030 programme (see ).

Here we briefly sketch out the overall justification by the OECD for the shift in goals in the Future of Education and Skills 2030 programme. Broadly, the OECD argues there is an urgent need to open a global discussion about education and the future aimed at setting new goals and a common language for teaching and learning. This is justified by asserting that a ‘new normal’ is ‘evolving’ (OECD Citation2020) which is changing the world of work, whilst new values of collaboration and concerns for individual and societal well-being now ask for new positive changes in education systems (see ). The old normal (past), of didactic pedagogy, a linear curriculum, standardisation, and individualised learning is contrasted with the new (emerging) normal: one defined by flatter structures, sharing, collaboration, well-being, compassion, different (non-standardised) assessment, and non-linear learning.

Table 2. The OECD’s representation of an emerging new normal in education.

We now turn to exploring five main strategies (see ) we have distilled from the OECD’s futures programme regarding how it is attempting to re-negotiate promissory legitimacy: rewriting the once future, now present and past; reimagining a new future narrative; refashioning discursive categories; reinforcing the credibility of the epistemic community, and reassigning responsibility to students for potential failures for promised futures to materialise (see ).

Strategy 1: rewriting the past

In this first strategy rewriting the past, the past is re-represented not simply through a rear-view window of what was, or back then, but it is rewritten as something very different to what is now. This difference is magnified via a contrast between the two (OECD Citation2018a). Using phrases like ‘we are facing’, ‘unprecedented challenges’, ‘accelerating globalisation’, ‘faster technological development’, ‘rapidly changing world’ ‘widening inequalities’ ‘adversity’ – the future (by way of contrast with this rewritten past) is represented as more unpredictable, more uncertain, and more hazardous, whilst the past is static, more certain and less ambiguous (OECD Citation2018b). Past and present schools are contrasted, conveyed as a ‘strawman’ with the school visualised as a Fordist factory; students only learning by listening to teachers, the curriculum is linear, standardised, and academic performance is prioritised, and students are assessed through standardised tests.Footnote2

This stark difference between a future as accelerating and the past as static (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2014), in turn, justifies the OECD’s intervention as epistemic expert and legitimate guardian of the challenges ahead. This in turn demands a response, which justifies the OECD’s second strategy which we present below; that of reimagining the future.

That the OECD has routinely launched all of its policies over the past three decades with a view of the future as heralding radical change (see Beech Citation2011; Rizvi and Lingard Citation2009) seems forgotten. That the OECD was a key architect and orchestrator of this now ‘problematic’ but receding present (as workplaces and societies are evolving to a new normal) is also made invisible. Instead, the arrow of time, as past, present, and future, seems to have its own momentum and to take the material form of its own volition, excusing the OECD from any part it might have played in the imagining and materialising of what must now be replaced. Yet just in case this new promised future presents itself as uninviting, it is also replete with more exciting opportunities and challenges (OECD Citation2018c).

Strategy 2: reimagining a new future

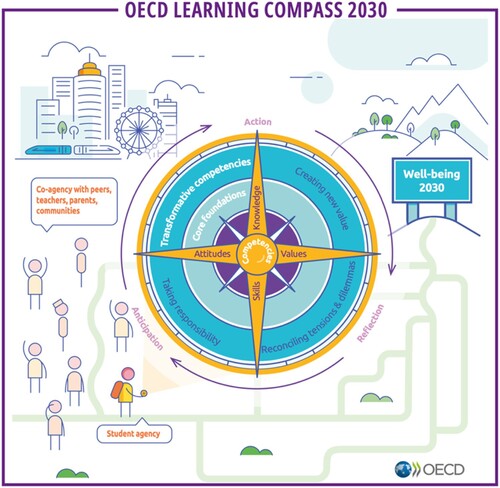

A second strategy follows from the first – that of reimagining of a new future for the student, schools, education systems, and societies. Here, the Learning Compass 2030 (Citation2019a) is presented as the main instrument of imagination for students regarding the future. This reimagined future, whilst hazardous, accelerating, unpredictable, and yet full of new opportunities, is to be navigated through learning new knowledge, ‘anticipating’ the outcomes of one’s ‘actions’, making responsible ‘decisions’ and ‘reflecting’ on these and their effects on oneself and others.

The Learning Compass 2030 (Citation2019a; also see ) is not simply ‘just a metaphor’; it is a pedagogical device (Bernstein Citation2000) inscribed with meaning (new demeanour and cognitive and affective attributes), saturated with a purpose (destination well-being), and charged with direction (the future). The coordinates of the destination that orient the learner/compass holder is a future state of ‘well-being’; a sign staked into the distant mountain to which the student must move (see ).

Figure 2. OECD Learning Compass 2030. (Source: OECD Citation2015. Learning Compass 2030 Concept Note Series, page 15, accessed at https://www.oecd.org/education/ 2030-project/contact/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf.).

The Learning Compass and its accompanying documents foreground the key dimensions to be developed by the individual: (i) taking responsibility, (ii) acquiring ‘transformative’ competences and not simply competences, (iii) creating new value (economic), and (iv) reconciling tensions and dilemmas (OECD Citation2019e). It is intended to shape a new way of acting and being in the world as a responsible agent. By implication, not engaging with the Learning Compass suggests irresponsibility.

The OECD positions the individual as responsible for their own fate, tasked with being entrepreneurial and with creating value for the economy. It is the student that ‘holds the compass’ to navigate towards their well-being (and their responsibility for realising it – see Strategy 5 below). And though the Learning Compass 2030 (OECD Citation2019a) includes gestures towards the collective and the environment, for example, it is acknowledged that students are not alone and that parents, teachers, and the community ‘interact with and guide the student towards well-being’ these are construed from the logic of the individual student as agent. Further, in the imagined workplace of the future (the new normal), it is represented as one shaped by harmonious teamwork and interaction in which there is no place for conflict. The kind of fundamental challenges that ‘are transforming our world and disrupting the institutional status quo in many sectors’ (OECD Citation2019b, 4) and are the trigger for the framework, melt into the air.

Similarly, the OECD (Citation2019a) gestures to the collective well-being as part of the destination to which the student is guided. Yet, here again, conflict is unimaginable; rather, the pursuit of individual well-being will somehow (magically) result in the well-being of society. And ‘even though there may be many visions of the future we want, the well-being of society is a shared “destination”’ (OECD Citation2019b, 9). But who are the ‘we’ represented in this assertion? As Sennett (Citation1998) reminds us, ‘we’ is a dangerous pronoun that can condense and make invisible complex sets of politics around collective formations, struggles over resources and status, and injustices.

Furthermore, the issue of ecological challenges is addressed from a purely anthropocentric and individualistic perspective: ‘Individual well-being helps build economic, human, social and natural capital – which, in turn, enhances individual well-being over time’ (OECD Citation2019b, 8). Not only is ‘nature’ reduced to a residual form of capital, but it is individuals who are responsible for building this form of capital which is only meaningful as much as it will benefit individuals.

Despite the rhetoric of newness, what really is different in the OECD’s framing of the student and education for the future in contrast with the past? A first glance suggests not much. The various elements of the Learning Compass 2030—attitudes, values, knowledge, and skills—are also elements in the OECD’s various programmes of large-scale assessments of competences, much of which continues in the background. But there is a shift in language regarding learning, learner, and workplace in framing the ‘new normal. A key difference is that a more explicit set of references to well-being and shared futures suggests a more humanistic set of concerns on the part of the OECD; a more general reorientation that Li and Auld (Citation2020) have also pointed to. We offer a different reading in our conclusions linked to changes in contemporary capitalism and the rise of immaterial labour.

Strategy 3: refashioning discursive categories

In a third strategy, key discursive concepts such as students, the future, schools, assessment, work, and knowledge – are refashioned to now imbue them with new meaning. Doing so enables a break with the past, and its promissory failures. Schools are presented as morphing effortlessly towards being hubs of collaboration and harbingers of personalisation, no longer closed off from the rest of the world.

The category ‘student’ is no longer represented as human capital and holder of skills but as an agentic, reflective, individual whose well-being is to be prioritised (OECD Citation2019c; Citation2019d). Students, we are reminded throughout the documents in both textual and visual form (OECD Citation2019a), have agency, and can be powerful actors whose orientation to responsibilities, actions, and reflexivity can lead to social transformations (see ). But what theory of agency does the OECD draw on, and what are the implications of this for the way in which the student is understood? In their publication Trends Shaping Education 2022 (OECD Citation2022, 85) student agency is defined as ‘ … the capacity of individuals to act independently and to make their own free choices’. In short, they are to be ‘future ready’ (OECD Citation2018a). This is an ethico-political take on agency, rather than a sociological one. A sociological view of agency of the kind that Archer (Citation1995) is concerned with might be more inclined to consider the relational and dynamic relationship between agency (people), structure (things), and culture (parts) to theoretically and empirically examine the ongoing relationships between cultural and structural systems, socio-cultural interactions, reflexivity, social statis, and social transformation.

By way of contrast, this ethico-political conception of agency has at its heart a liberal view of the human as making ‘free choices’; a set of assumptions Archer (Citation1995, 7) describes as an example of ‘upward conflation’ where causal efficacy is only granted to the agent whilst structures are given no autonomy. This liberal view of agency is also culturally specific; a Western Enlightenment ontology that can be contrasted with other social ontologies (Rappleye et al. Citation2020). Some of the visual references to students carry this agency story (cf. OECD Citation2018c): for example, a pair of shoe’d feet on a path marked ‘THE FUTURE WE WANT’. The assumption here is that the individual student can step out along the right path to make the ‘we’ future happen.

Yet this view of agency sits in ongoing tension with other assumptions and statements that run throughout the various texts underpinning the OECD’s futures programme. For example, in the video The New Normal (OECD Citation2020), societies are described as ‘evolving’, with education paralleling this evolution, through a magical ‘hidden hand’ (like that of the putative ‘free market’). The student is described as ‘adapting’ to these changes, rather than shaping them. In this moment we see an example of what Archer (Citation1995, 8) calls ‘downward conflation’; the agent adapts to structures, rather than shapes structures, as structures in this moment are given causal efficacy. Furthermore, the shift to the notion of the ‘learner’ suggests an entrepreneurial autonomous subject that individually accumulates knowledge and skills for their well-being to materialise. This is a rather schizophrenic rendering of the student, as simultaneously powerful and powerless as they face an unfolding future. Its opposing assumptions destabilises the coherence of the OECD’s narrative and potentially undermines its credibility.

‘The future’ is also viewed as having agency; as an actor without a subject, similar to how globalisation was narrated in the early 2000s (Watson and Hay Citation2003, 289); as ‘a non-negotiable external economic constraint in order to render contingent policy choices “necessary” in the interests of electoral rejuvenation’. It is also parsed as ‘by definition unpredictable’ (an unpredictable agent) (cf. video The New Normal, OECD Citation2020a), and full of shocks and shifts which in turn present ongoing navigational challenges. The global challenges identified are demographic shifts, resource capacity, and climate change, the importance of economic growth, and new challenges in terms of social development. These challenges are presented as creating new tensions, dilemmas, and trade-offs; between equity and freedom, autonomy and solidarity, efficiency and democratic processes, ecology and simplistic economic models.

The future is also a techno-science one that is digital, and increasingly automated leading to fewer jobs, with uneven skill distributions (apparently clustered in cities), and financialised. Yet unsurprisingly, this re-rendering of this future, as on the one hand now less concerned with profit and more engaged by purpose, shaped by flattened hierarchies and greater teamwork, and on the other hand dominated by digital technologies, has very little to say about the big tech giants who dominate digital infrastructures on which more and more of education, including the work of the OECD (via its many partnerships) depends on (Morosov Citation2022). What is needed for this kind of work in the future, argues the OECD, are students who can become more entrepreneurial, creative, and innovative, with social and emotional intelligence, and cognitive skills (OECD Citation2018a). The competences the student is to learn will enable them to solve problems through being resilient, reflexive, compassionate, and empathetic. To ‘create new value’, a student needs to have a sense of purpose, curiosity, and ‘an open mindset’ towards new ideas, perspectives, and experiences. Creating new value requires critical thinking and creativity so as to ‘spark’ innovation, argues Grey and Morris (Citation2022). And here we’re now in familiar territory for the OECD, as the aim of creating new value is a euphemism for economic growth (OECD Citation2019a).

Strategy 4: reinforcing credibility by epistemic community

A fourth strategy is to represent and engage an epistemic community to tell stories of what is important to them, and why the OECD future is to be seen as credible. Beckert (Citation2016) argues that these stories, of sage advice, expertise-based endorsements, and need, generate authority for this new promise. A very long list of ‘contributors’ is presented over 9 pages (OECD Citation2018a, 8–17); these are experts of various kinds, some described as ‘thought leaders’, others are well-known academics, like Harvard’s Professor Howard Gardner, whose narratives are intended to promote the credibility of the OECD’s new concepts and programme (OECD Citation2019g). A range of ‘on the ground’ examples are also presented from students speaking (OECD Citation2018d), schools engaging, and teachers talking, all aimed at building up credibility as they refer to environmental sustainability, nuclear energy, or domestic decisions concerning how to decide on detergents.

This almost unprecedented level of invoking ‘stakeholders’ (including students and teachers), together with the notion of ‘co-production’ may well also be the result of growing criticisms levelled at the OECD. Critics point to the growing power of the OECD’s education assessment portfolio, on the one hand, and question whether it really adds value to a nation’s education programming aimed at improvement, on the other, because of its one-size fits all policy prescription (Rappleye et al. Citation2020; Rizvi and Lingard Citation2009).

Strategy 5: reassigning responsibility for future failures

A final fifth strategy by the OECD involves reassigning responsibility for the potential failure to deliver a promised future ‘the learner’ as agent, whose navigational competences can either lead to social transformations and thus well-being, or its opposite. This in turn relieves the OECD of the legitimation burden when an undesirable present arrives. Despite the fact it is the OECD who is the master choreographer and orchestrator of the student’s future, it is the student as navigator who is responsible for using the Learning Compass wisely to attain well-being.

Yet there are also instabilities in meaning arising from inconsistencies as to who the initiative is for and who it is speaking to. In the main document of the Learning Compass 2030 (Citation2019a; Citation2019b) the OECD states repeatedly this is neither an assessment framework nor a curriculum framework, that it is a ‘learning framework’, though quite what the difference is not evident. That said, this conceptual obfuscation allows the OECD to move beyond its fixation with competencies that can be measured through standardised tests.

The framework offers a broad vision of the types of competencies students need to thrive in 2030, as opposed to what kind of competencies should be measured or can be measured. While it is often said that ‘what gets measured gets treasured’, this learning framework allows for what cannot be measured (at least, for the time being) to be treasured (OECD Citation2019b, 5).

Yet the same document describes the current initiative of the OECD as a guide to make curriculum design more ‘evidence base and systematic’ (OECD Citation2019b, 4). In the introductory video Schleicher not only repeats this emphasis on helping curriculum designers all over the world to ‘build national curricula in a way that is predictable’, but he also suggests the real challenge is in designing learning environments and practices that help students learn what the OECD mandates as their needs for their future wellbeing. In this way, if the promises of the future do not materialise, the responsibility for the failure can also be reassigned not just to students, but to local leaders and teachers.

5. Promises promises – final reflections

We began this paper by reflecting on the English idiom, ‘promises, promises’, the title of our paper, to explore how an IO like the OECD, engages in anticipatory governance, on the one hand, and manages the legitimation burden of inconvenient truths and failed promises, on the other. This is especially so for the OECD whose role as thinktank and epistemic expert has enabled it to use ideational power to shape sub/national education debates and agendas in quite profound ways over the past decades. In this conclusion we want to reflect on two key matters raised by this paper: first, the ‘how’ (that is strategies to manage legitimation shortfalls and advance a new future with authority) question; and second, the ‘what’ and ‘why’ matter (the underlying political project that is being ideationally advanced) of the OECD’s 2030 Futures initiative.

In relation to the matter of ‘how’, we show using the OECD’s programme on the Future of Education and Skills 2030 there is a great deal of ongoing work the OECD engages in to re-renegotiate a new education future in ways that attempt to remove the legitimation burden of a failed set of promises largely tied to neoliberal policies. We have identified and explored five; rewriting the past, reimagining a new future, refashioning the core discursive categories to give them new meanings, reinforcing credibility via an expanded epistemic community, and reassigning responsibility to students going into the future for what might emerge as an inconvenient present. It is quite likely other strategies will emerge over time, in relation to different anticipatory governance projects, or as a result of the IOs own mission and history. In doing this work, we therefore hope this contributes to emerging research on anticipatory governance (Berten and Kranke Citation2022), promissory legitimacy (Beckert Citation2020), and the strategic management of present futures and future presents.

In relation to the matter of ‘what’ and ‘why’ of the OECD’s shift to individual agency, well-being, anticipation, and reflexivity in its new rendering of the future for education and societies, we argue it is important not to be distracted by appearances. Nor do ideas float free; they are also linked to material conditions and interests. In relation to appearances, at first glance, the OECD’s emerging ‘new normal’ for society, education, and work, and the ideal subject (agentic, reflexive, cooperating, and so on), suggests a radical, more humanistic, agenda for the OECD more akin to that of UNESCO (see Robertson Citation2022 and Elfert Citation2023). This could be read as witnessing a shift from neoliberalism to a form of humanism in the OECD’s narrative, or to paraphrase, is this simply neoliberalism with a humanistic face in the face of the failures of neoliberalism? Yet historically, the mission and vision of the OECD have been to advance the economic and development interests of the rich countries club (Woodward Citation2004) via a technocratic set of programmes through ideational renderings such as human capital, modernisation theory, competition, and innovation. There is little reason to see that anything has changed. Rather that it is capitalism that is transforming, and as a result, the ideational work of the OECD must follow along with the instruments of imagination that it uses to govern.

Given this, we offer two explanations that penetrate appearances. Our first concerns the limits of data evangelism as a mode of governing (national league tables and competition), which is unable to detect emotions, like the resentment of those left behind following decades of neoliberal policies, and which have fuelled authoritarian populist politics (Davies Citation2018). As Davies (Citation2018, 141) reminds us, emotions ought not to be romanced and placed in the ‘soft and cuddly’ basket. War, too, ‘ … demands a science of feelings which might help manufacture greater morale’. The task of governing is to mobilise whatever instruments of imagination for the purpose of governing those that it does not know, but whom it needs to control. The OECD, by making visible emotions and feelings along with cognition, enables it as governor to also detect and manage outraged bodies and not simply ‘value producing’ minds.

Our second explanation engages with work on the new demands of post-industrial capitalism, rapid digitalisation, and immaterial labour (cf. Berardi Citation2009; Dorahy Citation2022). Berardi’s (Citation2009) The Soul at Work explores the rise of cognitive capitalism as a new phase of capitalist development beyond industrial capitalism. In the Preface, Smith (13-14) argues what we are witnessing is human capital being harnessed and put to work, not in an abstract general force of labour, but now as a ‘unique combination of psychic, cognitive and affective powers’ that Berardi (Citation2009, 21) calls ‘soul’. Soul is used as a euphemism to describe the labour process which is fundamental to immaterial production characteristic of the new digitally mediated economy. Immaterial labour, by contrast with industrial labour, is increasingly personalised, with immaterial workers incomparably less interchangeable than their industrial forebears. This is because of the range of individual and specific competencies required in the performance of their role. This fact brings about an important shift in the social relationships between high tech or immaterial workers, and their work. ‘Whilst industrial workers invested their physical energies in the process of social production, immaterial workers are called upon to invest, amongst other things, their creative sensibilities and communicative capacities.’ Concomitant to this is the tendency of such work to emerge as a primary centre in the focus of individual desire. Contemporary work, for increasing sections of society, has become ‘the object of an investment that is not only economical but psychological’ (our italics, Dorahy Citation2022, 26). The ongoing importance of positive integration to ensure the ongoing productivity of the immaterial labourer helps us recognise why happiness and agency are also viewed by the OECD as central psychological attributes.

That said, the OECD’s 2030 futures programme faces many challenges as a promised future. This is in part because its other programme of policy work tied to skills, large-scale assessments and standardisation, have not disappeared. Instead, they sit in the background. Orchestrating the two, seemingly contrasting, approaches – of an ‘old normal’ and a ‘new normal’ – suggests a lack of ideational clarity, solidity and thus hegemony, on the part of the OECD. This may well be the case, but this will only become clearer over time. We also note rather schizophrenic tensions between concepts making up the new futures programme – between no agency and much agency, a future to be made and a future already made, of discretion, cooperation, and creativity and standardisation. Is this the result of an ongoing ambivalence, and which might disappear, or is this strategically useful to the OECD?

Clearly, not all work into the future will require a cognitariat engaged in immaterial labour in the digital economy, and that massification and industrialisation will continue in some form in the developed economies, for example in the expanded services sector (Oesch Citation2006). Education systems will also still need to legitimate new forms of stratification, reproduce the division of labour, and justify inequalities as failures of aspiration and effort. Does assigning greater agency to the student in turn stitch neoliberal meritocracy more firmly into the education ideational landscape, so that getting ahead is viewed as the outcome of one’s own (failed or successful) individual agentic efforts? We think so.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the two SI Editors, the 4th September Webinar participants, our colleague Fazal Rizvi, and the two anonymous reviewers, for their generous and constructive engagements with our text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Susan L. Robertson

Susan L. Robertson is Professor of Sociology of Education, University of Cambridge, UK, Fellow Wolfson College, and Distinguished Professor at Aarhus University. She has written extensively on transformations of the state and education policy, globalisation and global governance, and multilateralism. Susan is founding and current co-editor of the journal Globalisation, Societies and Education.

Jason Beech

Jason Beech is Associate Professor of Global Policy in Education at the Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne. He examines how ideas about education are developed in global educational spaces and influence education policies and practices in different parts of the world. Jason is also a visiting professor in the School of Education at Universidad de San Andrés in Argentina, where he is Director of a UNESCO Chair in Education for Global Citizenship and Sustainability.

Notes

References

- Alvial-Palavicino, Carla. 2015. “The Future as Practice. A Framework to Understand Anticipation in Science and Technology.” Tecnoscienza–Italian Journal of Science & Technology Studies 6 (2): 135–172.

- Archer, Margaret. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Auld, Euan, and Paul Morris. 2019. “Science by Streetlight and the OECD’s Measure of Global Competence: A New Yardstick for Internationalisation?” Policy Futures in Education 17 (6): 677–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318819246

- Balibar, Étienne. 2019. “Towards a New Critique of Political Economy: From Generalized Surplus Value to Total Subsumption.” In Capitalism: Concept, Idea, Image. Aspects of Marx’s Capital Today, edited by Peter Osborne, Eric Alliez, and Eric-John Russel, 36–57. London: CRMEP Books.

- Beckert, Jens. 2013. “Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations in the Economy.” Theory and Society 42 (3): 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-013-9191-2

- Beckert, Jens. 2016. Imagined Futures. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Beckert, Jens. 2020. “The Exhausted Futures of Neoliberalism: From Promissory Legitimacy to Social Anomy.” Journal of Cultural Economy 13 (3): 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2019.1574867

- Beech, Jason. 2011. Global Panaceas, Local Realities: International Agencies and the Future of Education. Lausanne: Peter Lang.

- Berardi, Franco Bifo. 2009. The Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e).

- Berger, Thor, and Carl Benedikt Frey. 2017. “Future Shocks and Shifts. Challenges for the Global Workforce and Skills. Trends Analysis.” OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/about/documents/Future-Shocks-and-Shifts-Challenges-for-the-Global-Workforce-and-Skills-Development.pdf.

- Bernstein, Basil. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control, and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. Vol. 5. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Berten, John, and Matthias Kranke. 2022. “Anticipatory Global Governance: International Organisations and the Politics of the Future.” Global Society, 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2021.2021150

- Davies, William. 2018. Nervous States: Democracy and the Decline of Reason. London: WW Norton & Company.

- Dellmuth, Lisa Maria, Jan Aart Scholte, and Jonas Tallberg. 2019. “Institutional Sources of Legitimacy for International Organisations: Beyond Procedure Versus Performance.” Review of International Studies 45 (04): 627–646. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026021051900007X

- Dorahy, James Francis. 2022. “Notes Towards the Critical Theory of Post-Industrialism Capitalism.” Thesis Eleven 171 (1): 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/07255136221116381

- Elfert, Maren. 2023. “Humanism and Democracy in Comparative Education.” Comparative Education, 1–18.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2013. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. London: Routledge.

- Grey, Sue, and Paul Morris. 2022. “Capturing the Spark: PISA, Twenty-First Century Skills and the Reconstruction of Creativity.” Globalisation, Societies and Education. DOI: 10.1080/14767724.2022.2100981

- Hall, Peter A. 1993. “Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain.” Comparative Politics 25 (3): 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246

- Hood, Christopher. 1991. “A Public Management for All Seasons?” Public Administration 69 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

- Jessop, Bob. 1999. “The Changing Governance of Welfare: Recent Trends in Its Primary Functions, Scale, and Modes of Coordination.” Social Policy & Administration 33 (4): 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00157

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 2014. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. Vol. 8. New York: Verso Books.

- Li, X., and E. Auld. 2020. “A Historical Perspective on the OECD’s ‘Humanitarian Turn’: PISA for Development and the Learning Framework 2030.” Comparative Education 56 (4): 503–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2020.1781397

- Martini, Michele, and Susan L. Robertson. 2022. “Erasures and Equivalences: Negotiating the Politics of Culture in the OECD’s Global Competence Project.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2022.2084035.

- McGoey, Linsey. 2019. The Unknowers: How Strategic Ignorance Rules the World. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Milanovic, Branko. 2016. Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. New York: Harvard University Press.

- Morosov, Eugeny. 2022. “Techno-feudal Reason.” New Left Review 133/134: 89–126.

- OECD. 2008. Growing Unequal? Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2011. Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2015. “OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030. Thought Leaders.” https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/thought-leaders/.

- OECD. 2016. Global Competency for an Inclusive World. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2018a. “The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030 Position Paper.” Accessed 14 August 2023. http://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/about/documents/E2030% 20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf.

- OECD. 2018b. “The Future of Education and Skills: Learning Compass 2030.” https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/.

- OECD. 2018c. “The Future of Education and Skills: The Future We Want.” Accessed 14 August 2023. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf.

- OECD. 2018d. “The Future of Education and Skills: The Future We Want. Video of students.” Accessed 14 August 2023. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/well-being/.

- OECD. 2019a. “OECD Learning Compass 2030. In Brief.” https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/in_brief_Learning_Compass.pdf.

- OECD. 2019b. “The Future of Education and Skills 2030, Conceptual Learning Framework. Concept Note.” Accessed 14 August 2023. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_concept_note.pdf.

- OECD. 2019c. “In Brief. Student Agency for 2030.” https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/student-agency/in_brief_Student_Agency.pdf.

- OECD. 2019d. “Conceptual Learning Framework. Student Agency for 2030.” https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/student-agency/Student_Agency_for_2030_concept_note.pdf.

- OECD. 2019e. “In Brief. Anticipation-Action-Reflection for 2030.” https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/aar-cycle/in_brief_AAR_Cycle.pdf.

- OECD. 2019g. “Towards Collective Wellbeing. Howard Gardner.” https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/Thought_leader_written_Gardner.pdf.

- OECD. 2020. “Future of Education and Skills 2030.” The new normal. Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9YNDnkph_Ko.

- OECD. 2022. “Megatrends Shaping Education.” https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/trends-shaping-education-22187049.htm.

- Oesch, Daniel. 2006. Redrawing the Class Map: Stratification and Institutions in Britain, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. New York: Springer.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rappleye, Jeremy, Hikaru Komatsu, Yukiko Uchida, Kuba Krys, and Hazel Markus. 2020. “‘Better Policies for Better Lives’?: Constructive Critique of the OECD’s (mis) Measure of Student Well-Being.” Journal of Education Policy 35 (2): 258–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1576923

- Rizvi, Fazal, and Bob Lingard. 2009. Globalizing Education Policy. London: Routledge.

- Robertson, Susan L. 2021. “Provincializing the OECD-PISA Global Competences Project.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 19 (2): 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1887725

- Robertson, Susan L. 2022. “Guardians of the Future: International Organisations, Anticipatory Governance and Education.” Global Society 36 (2): 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2021.2021151

- Robertson, Susan, Karen Mundy, Antoni Verger, and Francine Menashy. 2012. Public Private Partnerships in Education: New Actors and Modes of Governance in a Globalizing World. Cheltenham, UK; Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 1997. “Economic Integration, Democracy and the Welfare State.” Journal of European Public Policy 4 (1): 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/135017697344217

- Schmelzer, Matthias. 2016. The Hegemony of Growth: The OECD and the Making of the Economic Growth Paradigm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sennett, Richard. 1998. The Corrosion of Character: The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism. London: WW Norton & Company.

- Sorensen, Tore Bernt, Christian Ydesen, and Susan Lee Robertson. 2021. “Re-reading the OECD and Education: The Emergence of a Global Governing Complex – An Introduction.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 19 (2): 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1897946

- Strassheim, Holger. 2016. “Knowing the Future: Theories of Time in Policy Analysis.” European Policy Analysis 2 (1): 150–167. https://doi.org/10.18278/epa.2.1.9

- Streeck, Wolfgang. 2014. “How Will Capitalism End?” New Left Review 87: 35–64.

- Szerszynski, Bronislaw. 2017. “Gods of the Anthropocene: Geo-Spiritual Formations in the Earth’s New Epoch.” Theory, Culture & Society 34 (2-3): 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276417691102

- Watson, Matthew, and Colin Hay. 2003. “The Discourse of Globalisation and the Logic of No Alternative: Rendering the Contingent Necessary in the Political Economy of New Labour.” Policy & Politics 31 (3): 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557303322034956

- Woodward, Richard. 2004. “The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.” New Political Economy 9 (1): 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356346042000190411

- Zürn, Michael. 2018. A Theory of Global Governance: Authority, Legitimacy, and Contestation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.