ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to stretch spatial theorising in the field of comparative education. Among the different spatial theoretical approaches that have been explored in educational research in the last 10 years, we review social topology, spatial-temporalities, and beyond-human spatialities and how they have been used in comparative education research. To illustrate the potential of these approaches we then use them to analyse recent technological changes, shifts in governance, the impacts of global crises and the complicated ways in which they are spatially related to education. Through our analysis, we argue that comparative education research would benefit from making space for spatial theorising in relation to time, materiality, and the beyond-human, not only to better understand the world, but also to consider how education is ethically linked to the existential challenges humanity is facing today.

摘要

本文旨在扩展比较教育领域的空间理论研究。近十年来,教育学界已探索不同的空间理论方法,我们从中选取社会拓扑学、空间 – 时间性和超越人类的空间性这三种方法,并回顾它们在比较教育研究中的应用。为说明这些方法的潜力,我们随后用它们来分析近期的技术变革、治理方式的转变、全球危机的影响以及这些现象与教育在空间上的复杂关系。通过分析,我们认为比较教育研究将受益于与时间、物质性和超越人类相关的空间理论,这不仅是为了更好地理解世界,也是为了探讨教育如何在伦理上与当今人类面临的生存挑战联系在一起。

Introduction

Comparative Education (CE) is intrinsically related to spatial thinking. In other words, as much as we can think of the history of education as being involved with education across time, the field of CE is concerned with education across space. Ten years ago, two of us, Beech and Larsen, published two articles which promoted ‘new’ spatial thinking in comparative and international education (Beech and Larsen Citation2014; Larsen and Beech Citation2014). We called for deeper engagement among CE researchers with the spatial turn in the social sciences and the use of relational spatial approaches; overcoming spatial binaries such as global/local and space/place. We discussed the constitution of space as assemblages of relations and emphasised the performativity of space by arguing that space is both produced by and at the same time produces social activities.

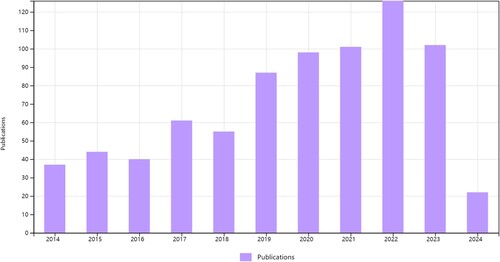

Since then, as illustrates, there has been an explosion of publications within the field of education that draw upon a spatial lens (Web of Science Citation2024).Footnote1

The widespread deployment of spatial theories in educational research can be viewed as a response to the contemporary re-organisation of space and time in society evidenced by significant technological shifts, as well as a wide range of crises facing our planet such as the Covid-19 pandemic and the climate crisis. These transformations are significant because they have occurred almost everywhere in the world crossing political, economic, and cultural boundaries. These shifts have had a major impact on the spatial and temporal dimensions of education. Given these ongoing changes in society, we assert that spatial theoretical and methodological constructs afford comparative education scholars the tools required to research and write about education in a world soaked in spatialisation.

In the first half of this article, we discuss spatial approaches that we find productive to problematise education within the contemporary zeitgeist. Among the spatial theoretical approaches that have been explored in educational research in the last ten years, we are particularly interested in the use of social topology, spatial-temporality, and beyond-human spatialities. In the second half, we integrate these spatial theories into analyses of significant spatial trends affecting education. First, we examine technological developments associated with platformisation, digitalisation, and datafication. Next, we draw upon spatial theories to analyse shifts in governance across educational settings. And finally, we turn our attention to how spatial theories facilitate a deeper understanding of inequalities and injustices emerging through the global crises our world faces today.

Overall, then, the aim of this article is to inspire further, more explicit spatial theorising in the field of CE. We are gratified to see so many comparativists engaging with spatial theories over the past decade and refer to much of that work in our article. However, we also urge those within our field to stretch space even further in their research by being even more explicit about how they are using space theoretically; considering the methodological, analytic and ethical consequences of the spatial concepts that they use. Through our analysis, we demonstrate the value of making space for space in relation to time, materiality and the beyond-human world in educational research, not only to better understand the world, but also to consider how education is ethically linked to the existential challenges the world is facing.

Spatial theoretical approaches

Social topology

Social topology has its roots in the eighteenth-century mathematical discipline of topology, which focuses on how the properties of forms, shapes, and figures are preserved through deformations and transformations.Footnote2 Topology identifies the essential properties of forms and figures, while simultaneously dealing with how they stretch and shape (e.g. how a circle can be squeezed into the form of a triangle, and yet retain its essential properties). As such, topology as the ‘geometry of rubber sheets’ is less interested in measurement and scale, and more in the essential spatiality, shape, or structure of a figure/form that remains the same under transformation. This is equated to the concept of the manifold, a stretchy, flexible sheet that can bend and twist into various forms, allowing for the study and description of spaces that have different geometries and structures. In this respect, topology is concerned with what happens to a form over time and, thus, is considered ‘geometry plus time, geometry given body by motion’ (Conner Citation2004, 106).

Mathematician’s interest in topology was taken up by social scientists and reframed as social/cultural topology. In a seminal article, Lury, Parisi, and Terranova (Citation2012) argue that culture is becoming more topological with the use of topology as a way of analysing culture. Hence, topology is both ontological in terms of the nature of being of contemporary life, and epistemological in terms of how we come to understand modern society. As a method to analyse contemporary culture, social topology focuses on interrelationships between space and time, how spatial relations of social life exist and how they are transformed by and through the actors that produce them (Decuypere and Simons Citation2016; Kallio Citation2021). However, topology does not merely direct us to the idea that space emerges from relations between things, but to the spatial operation of continuity and change, repetition, and difference (Decuypere and Lewis Citation2023). Thus, it is concerned with how continuity and change take place together, forcing us to reconsider relationality itself and how relations are formed and endure despite conditions of continual change (Lury, Parisi, and Terranova Citation2012).

Additionally, social topology shifts focus away from traditional units, levels, and scales of analysis. Rather than considering scales of analysis (e.g. local, national, global) as being nested within one another and unfolding chronologically over time, social topology frames these as near and far in terms of their relational connectedness to and through one another (Decuypere and Lewis Citation2023). In other words, the local, national, and global exist in multiple relations to one another along a topological continuum of the in-between and over time. Thus, instead of positing the ‘global’ as acting on ‘local’ settings, social topology considers the ways in which different enactments of, for example, educational accountability (e.g. in-school student assessments and the publishing of large-scale cross-national testing data), produce and govern the individual student, school, etc. as a unified whole. That being said, traditional scales of analysis (e.g. the nation-state) have not simply become obsolete, but rather ‘are understood as parts of multiple scalar and (also de)territorial transformations, in which governmental power is constantly created or (de)stablised’ (Hartong Citation2018, 135).

These ideas have been explored within much recent comparative education (CE) policy research that has focused on concepts such as assemblages, networks, connectivity, reterritorialisation and re-bordering (e.g. Addey and Gorur Citation2020; Gorur Citation2011; Gulson and Sellar Citation2019; Salajan and Jules Citation2022; Sellar and Gulson Citation2018). And as we explore in further detail below, attention has also been drawn to the ways in which a range of educational policy actors are now creating new governing policy spaces that transcend cultural and national boundaries (Hartong Citation2018; Lewis Citation2020; Lewis and Lingard Citation2023; Lewis, Sellar, and Lingard Citation2016; Lingard Citation2019; Citation2022).

This social topological research has built upon a rich history of earlier CE policy research concerned with the flows and movement of policies across space and time. In writing about the problematique of studying the movement of educational ideas, policies and processes, Cowen (Citation2009) alerted us to the fact that ‘as it moves, it morphs’ (315). This notion of ‘morphing’ is close to the topological process of twisting and bending associated with manifolds. This concept of manifolds helps us understand and model phenomena in the real world that have complex and changing properties. Further, topological research allows us to better understand the essential properties of educational forms over time and space, while simultaneously dealing with the morphing, bending, and shaping of those forms over time and space.

What a topological approach adds to CE policy mobility research is a richer understanding of how policies move within and across sites, remain the same and yet also simultaneously are reconfigured and reconfigure these spaces. These interactions, flows and movements through space, as well as local processes of enactment, reshape the policies and actors involved. There is room, however, for policy mobility researchers engaging with social topology to be more explicit about how they define the properties of educational ‘forms’ under study and how they are preserved through transformation. Adopting a social topological lens will be useful for education policy researchers seeking to address the networked nature of education policy making across borders, as well as for understanding how the enactment of ‘global’ policy flows is shaped by decidedly ‘local’ conditions and contexts, and vice-versa. Next, we turn our attention to spatial-temporalities, a related spatial theoretical approach.

Spatial-temporalities

Modernist logics frame time as linear, evolutionary, universalist and running infinitely into the future. These understandings of time have colonised and shaped the development of education systems and research about them based on the assumption that education (and empirical research) are based on linear, universal paths to enlightenment and truth. These assumptions of linear progress continue to influence the enterprise of educational systems today that focus on the large-scale, standardised collection of quantitative data about students to measure success, understood as the contribution of education to unlimited economic growth without consideration of the finiteness of natural resources.

In place of this logic, we propose an analytical perspective that shifts this understanding of time, and simultaneously considers time in relation to space (Seddon Citation2023). Rather than perceiving time as linear, many scholars conceive of time as being circular and cyclical. For example, Japanese scholar Maki Yusuke proposes the notion of ‘Circular Time’ reflecting patterns of recurrence such as the sun rising and setting (Rappleye and Komatsu Citation2020). Similarly, in Latvian culture, the conceptualisation of time is strongly connected to the circularity of seasons and the interconnection between time and space is always highlighted (Silova Citation2019).

Indigenous scholars and those working with Indigenous ways of knowing similarly view time as non-linear, multiple, and spiralling. Time in these cosmologies is agential, affective and deeply situated in place. Such Indigenous conceptualisations point to the relational connections between and co-constitution of people, places (or spaces), and times (Wright et al. Citation2020).

These relational connections between space and time do not give primacy to time over space, but contend that spaces and times evolve conjunctly and mutually shape the constitution of each other. As Lingard (Citation2022) explains, spatio-temporality is ‘a recognition that we live and work in the interrelatedness between time and space, both of which help constitute the local, national, supranational, regional and global’ (985). Rather than recognising time ‘as a side element to social life’, as Atkinson (Citation2019, 951) puts it, there is more to gain epistemically when we weave time into our explanatory accounts of spatial relations in education.

For instance, Lingard and Thompson (Citation2017) advocate the concept of ‘timespace’ to describe what happens in international large-scale assessments such as PISA when students from different parts of the world take the tests on the same days, test results are also released at the same time, and analysis takes place ‘“in real time” in the not-too-distant future’ (10). Moreover, research on the digitalisation of education through a spatial–temporal lens elaborates on the constitution of new educational spaces and their effects. Research on the European digitalisation of education strategies, Opening Up Education and Digital Education Action Plan, demonstrates that time is no longer discursively constructed as a singular progression based on the assumption of a cumulative growth of student learning in the future. Instead, the policies highlight the future as part of the present with risks and uncertainty. That is ‘progression is no longer what can be assumed or taken for granted, the way to temporally act is by means of establishing foresight and … designing futures drawing on what is possible in the present’ (Decuypere and Simons Citation2016, 7). In alignment with this logic, a European educational space is created through the adoption of digital platforms where students can access learning resources and opportunities. Such a learning space is different from the traditional bounded physical space of a classroom in the way it assembles teachers, students and digital content from all levels of education, and enables the flows of scholars and learners as well as knowledge across various regions.

Finally, from a spatial–temporal perspective, time and space are not universally fixed or measurable, but together are experienced subjectively. Time is considered subjective in the ways in which it is experienced by daily practices and individuals’ sensational experiences (Gulson Citation2015; Silova Citation2019; Webb, Sellar, and Gulson Citation2020). Focusing on the duration and personal experiences, time is no longer ‘a container for events’ (Williams Citation2011, 62), but sensed through lived experience with particular attention to memory and habits (Deleuze Citation1994). In this regard, the construction of space–time is relational and embedded in one’s social, cultural, and political background, as well as our relationships with the beyond-human world as we will read further below.

Beyond-human spatialities

Above we discussed the intertwined relationships between space and time. Here we argue that educational research should also pay much more attention to the connections of humans to the material world and to our relationships or entanglements with the non-human. The artificial borders established between the realms of ‘the social’ and ‘the natural’ are not only an epistemological problem that hinders our capacity to understand relevant connections and flows of power, but in times of planetary ecological crises, contributes to a significant ethical dysfunction. Chakrabarty describes the challenge eloquently:

How do we (re) imagine the human as a form of life connected to other forms of life, and how do we then base our politics on that knowledge? Our political categories are usually imagined not only in profoundly anthropocentric terms but in separation from all these connections. But can we extend them to account for our relationship to nonhuman forms of life or even to the non-living that we can damage (such as rivers and glaciers)? (Chakrabarty Citation2021, 126)

Piattoeva (Citation2018), for example, has explored how transnational governance can be seen as a networked structure that is held together by human and beyond-human elements, such as international large-scale assessments and global metrics. She shows how these ‘[a]ssessment tools join and co-produce transnational policy networks, which extend across and draw together broad spaces, distances and times’ (114). One of the most significant insights that ANT has contributed to CE is the notion of policy as an assemblage (Gorur Citation2011) that has provided a generative means for analysing the socio-technical work of policy production and policy mobility across educational spaces (e.g. Lewis, Savage, and Holloway Citation2020).

The notion of infrastructure has also been used in CE, mostly to analyse the kinds of entanglements that are part of international large-scale assessments and the processes of datafication and digitalisation (Gulson and Sellar Citation2019; Lingard Citation2019; Sellar and Gulson Citation2018). Infrastructural approaches follow a methodological logic quite similar to the notion of assemblages in understanding the ways in which humans and non-humans constitute networks that produce power effects.

In this kind of work as expressed both in the notions of assemblages and infrastructures, the agency of the material is acknowledged, but overall, the kind of non-human entities that are considered are artificial human-made technologies. As much as this is a very important move to consider the relevance of the non-human and a significant step is taken in decentring the human, objects are considered mostly as conduits of human power, as nodes that connect human actors and relays of social interaction.

A whole realm of the non-human – what we normally associate with ‘nature’ – is ignored or weakly acknowledged. Furthermore, from the perspective of new materialist and post-human theorisations of matter and materiality, one of the biggest problems with ‘the material turn’ in the social sciences is that matter is reduced to language, culture and discourse (Bryant Citation2014). In other words, from the mainstream anthropocentric categories of the social sciences, particularly post structuralist approaches, perspective and positionality define reality. There is not such a thing as reality, but shattered and fragmented interpretations of the world that depend on the perspective of the interpreter. The world becomes an ‘alienated mirror of humans’ (Bryant Citation2014, 3). Humans are so dominant that the ontological being of things depends on our gaze. However, matter is more than just the conduit of social relations and meanings. What the material world is, does not depend on how we see it. Different people have different experiences of the consequences of global warming and how they interpret this phenomenon and how they react to it is important. But it is also important to acknowledge that climate change is out there, is real and even if we have contributed to its existence, it happens irrespective of how we see it. If we only stay with the discursive and language, we are missing at least half of the picture.

Decentring the human and thinking beyond anthropocentrism implies understanding that we are part of nature and that non-human (or what we might now call ‘beyond-human’) beings have agency and power of their own (Bryant Citation2014). Social and environmental struggles are not discrete issues, but interrelated with one another. In considering the spatial dimensions of inequalities and environmental crises, Latour (Citation2018) points to acknowledging ‘what the bond with coal or with oil does to the earth, to the workers, engineers and companies’ (62), and to Indigenous populations around the world. The paradigm of an economic logic based on the belief that there are no material limits, that has been spatially stretched through colonial and post-colonial connections is also entrenched in the ways in which we think about education (e.g. calls for more digital technologies in schools without any consideration of their ecological impact). By pushing us to think analytically and ethically about these entanglements, Latour (2018) refers to the ‘new geo-social question’ (63).

In the field of CE, Silova (Citation2021) has encouraged comparativists to consider more than human entanglements in their spatial categories, arguing that education helps to perpetuate ‘the logic of human exceptionalism and the hierarchical “man over nature” relationship, while simultaneously reducing nature to its exploitable value to benefit humans in pursuit of infinite economic growth’ (593). She calls for imagining and learning new ways of living with others, with the earth and other species; and suggests that in doing so we need to develop new vocabularies to consider and make sense of the human and beyond-human interconnections.

She highlights the notion of sympoiesis that, citing Harway, she understands as denoting the idea that ‘nothing makes itself; nothing is really autopoietic or self organizing … Sympoiesis is a word proper to complex, dynamic, responsive, situated, historical systems. It is a word for worlding-with, in company’ (594). This is a spatial concept, as much as it focuses on the ways in which human beings are related and connected with each other and with the more than human.

Rethinking spatial categories to decentre the human and place at the centre of educational research our connections with beyond-human entities, as many cosmologies have done since ancient times, would not only help researchers understand analytically the way in which education is entangled with the world, but is also key in reformulating ethical approaches to education and its effects.

Having introduced these three spatial approaches, in the second part of the article we show how they can help us understand some of the pressing intellectual and ethical educational challenges of our times. First, we examine the technological trends of platformisation, digitisation, and datafication through the lens of the spatial theories described above. Then we discuss how those spatial approaches can help us make sense of shifts in educational governance, and finally, we use these theoretical approaches to examine aspects of the relationship between the spatiality of education and planetary crises. To be clear, we do not aim to provide a full analysis of these issues, but rather demonstrate the productivity of spatial theories to interpret these contemporary challenges.

Platformisation, digitisation, and datafication (PDD) through a spatial lens

Over the last decade or so, the rapid advancement of technology has transformed society. Various terms describe these shifts including platformisation, digitisation, and datafication (PDD); which have been made possible by improved Internet access and the global proliferation of mobile devices. In a platform society, ‘social, economic, and interpersonal traffic is largely channelled by a global online platform ecosystem that is fuelled by data and organized through algorithms’ (van Dijck, Poell, and de Waal Citation2017). Platformisation affects sectors such as transport, hospitality, health, news and education. As much as platforms can be seen as technological tools that facilitate social interaction and our routine everyday activities, they also shape how society is organised, transforming almost every aspect of our lives, including how we understand and manage knowledge, teaching and learning.

Related phenomena that have become more widespread and normalised in everyday life are digitisation and datafication. Digitisation is the process of converting information into a digital format, allowing for it to be organised into discrete units of data. Datafication is a broader process that involves quantifying previously qualitative information that has been converted into digital data and making it visible, and then tracked, organised, and monitored. In this way, data storage, management and analysis technologies now provide the tools to identify patterns and trends, shaping political, economic and social relationships through algorithmic logics.

Contemporary culture has become more topological through the spread of these practices. Topologies emerge and are evidenced through a wide range of technologies commonplace to modern society such as the census, registers and filing systems that organise, list, sort, number, track, calculate, compare, and connect people, objects, and activities (Lury, Parisi, and Terranova Citation2012). Thus, we have a proliferation of topological cultural forms such as lists, models, networks, and flows, which are created and spread through the related processes of PDD.

The fact that culture has become more topological is linked to the new spatialities that have accompanied globalisation. Lury, Parisi, and Terranova (Citation2012) note that ‘as the rationality of culture is becoming coextensive with the globe, the globe itself is simultaneously being brought into existence as a topological space’ (28). However, what Lury, Parisi, and Terranova (Citation2012) propose is not simply a correspondence between culture becoming more topological and topology providing a new method for studying culture, but rather that topology has emerged in and through the very ways we now use to organise, order, and understand culture, technology, and science. These practices have introduced continuities into a discontinuous world (through establishing equivalences), and make and mark discontinuities through contrasts over time. In this way, topology itself now shapes, orders, and creates social/cultural life, and this has profound implications for education.

Together these topological technological trends have reshaped educational spaces, teaching and learning in ways unimaginable a few decades ago. As digitisation has spread globally, we have witnessed pervasive adoption of digital instruments in teaching and learning, including laptops, tablets, interactive whiteboards and educational software. While present in many schools for several decades, the pandemic rapidly accelerated digitisation as school buildings in most parts of the world were closed and educational practices shifted from school-based/on-site to fully online learning. As a result, personal devices were transformed into classrooms and the spatiality of schooling was radically reconfigured (UNESCO Citation2021).

Education has also been reshaped by platformisation. Online educational platforms, while present in many schools prior to the pandemic, grew exponentially after 2020. This included the spread of Massive Open Online Courses, and learning platforms such as Moodle and Google Classrooms, which have allowed students located in different physical places and across time zones to be simultaneously present in a class through their digital devices and the Internet. This shows how digitisation challenges taken for granted assumptions about what it means to be present in the ‘here and now’, but equally to what it means to be ‘near’ or ‘far’ or what it means to be positioned ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ a specific educational practice (Decuypere, Hartong, and van de Oudeweetering Citation2022).

These shifts contributed to the creation of new spatial-temporalities of education. Prior to the spread of online learning platforms, in a ‘normal’ school day, students left home and went to school, typically a physical building, which was spatially divided based on different functions: the classroom for learning, the playground for leisure time, etc. and their activities were chronologically scheduled according to the school’s timetable. The digitisation of learning through online platforms has created new space-times for those engaged in learning and teaching. The division between lesson and leisure time as well as the boundary between public (school space) and private space (home space) were ruptured during the pandemic as beds, bedrooms and kitchens became offices and classrooms (Borduas, Kehler, and Knott-Fayle Citation2023). Moreover, the use of screens blurred boundaries between different temporalities such as social time (through SMS with friends and family), economic time (through online shopping) and school time (through online learning).

Finally, platformisation is also constituted by the significant increase in the collection, calculation, and comparison of large amounts of educational data, such as demographic information, grades and student behaviours, through learning management systems (LMSs), platforms that contain digital information about students. Datafication in education is constituted by the ways that educational actors (both students and teachers) are assessed and measured, locally, nationally, and globally, and by the almost immediate way data are generated and circulated across space. Data and insights collected from LMSs have enabled the development of learning analytic platforms (LAPs), which collect, analyse and report data about learners and contexts in which learning occurs (Siemens and Gašević Citation2012).

Ostensibly, these forms of platformisation and datafication enable ‘an unprecedented number of people (e.g. students, teachers), institutions (e.g. schools, schooling systems) and processes (e.g. learning, pedagogy, improvement) to now be rendered as digital data, and for these data to subsequently inform decision-making around how education is understood, practiced and governed’ (Lewis, Holloway, and Lingard Citation2022, 71). If more educational practices can be rendered as data, which can then be organised, sorted, classified and compared, more opportunities arise not only for knowing the subject (e.g. student), but governing that subject and their practices in educational settings. In other words, these technological processes function topologically to constitute new spatial relations of governance in education, the theme we explore next.

Understanding shifts in governance through a spatial lens

Spatial theories shed light on how the technological processes we just discussed shape schools and educational systems as knowable and governable spaces. Here we extend our discussion on shifts in educational governance through a spatial lens (Seddon Citation2023). Research on PISA, for example, drawing upon a social topological lens directs our attention to power dynamics and governance across educational spaces. In studying the OECD’s program, PISA for Schools, researchers have shown how the enactment of new re-spatialised modes of educational governance can be understood as topological spaces of measurement and comparison (Lewis Citation2020; Lewis, Sellar, and Lingard Citation2016). These modes involve the participation of new actors in the global education field, including schools, school boards, departments, and ministries of education, for-profit ed-tech companies, as well as non-profit and philanthropic organisations (Lewis, Sellar, and Lingard Citation2016). More recent research on the impact of PISA for Schools further illustrates the emergence of new topological spatialities of globalisation whereby schools ‘by-pass’ their national governments and directly participate in the globally referenced PISA for Schools program, distinguishing themselves topologically from the state and national school systems performance mechanisms (Lewis and Lingard Citation2023).

How do spatial theories facilitate further understanding of these power-laden processes? The notion of infrastructure to account for spatial relations that extend beyond the human is productive in understanding the ways in which digitisation and platformisation affect decision-making in education. For example, Sellar and Gulson (Citation2021) analyse cognitive infrastructures, arguing that digital platforms and artificial intelligence (AI) contribute to new forms of automated thinking that change the ways in which humans make decisions about education policies. This itself promotes a form of synthetic governance in which human values, language and practices are combined with data infrastructures and algorithmic decisions making (Gulson et al. Citation2022). Digital data infrastructures connect what were previously discreet educational spaces with for-profit technological companies and other governing actors, allowing for new forms of governance to emerge. As much as the organisation of large sets of digital data into user-friendly visualisations can project an aura of objectivity and neutrality, these governing devices project and promote particular visions of what is a good education, what knowledge is valuable and how good teachers and students should behave (Lewis, Holloway, and Lingard Citation2022). In other words, the datasets produced through these infrastructures do not only represent educational actors and practices, but they actively constitute them.

Through a topological lens, it is possible to demonstrate how these governable spaces simultaneously change and yet remain durable. In this way, topology directs us to consider relationality itself and to question how relations are formed and then are sustained despite conditions of continual change. Regarding data infrastructures, social topology directs our attention not only to the governing logics mobilised and enabled by the joining-up of the human and beyond-human actors that constitute the infrastructure, but also to the mechanisms that sustain these relations and subsequently create the topology of the infrastructure. In their study of the US school monitoring data infrastructure known as EDFacts, Lewis and Hartong (Citation2022) illustrate how processes of governance shift when schooling becomes datafied. They analyse how EDFacts incentivises compliance to federal standards by encouraging teachers to submit data, and EDFacts staff to maintain flows of ‘quality’ data, and ensure compliance with EDFacts technical rules. Their study illustrates how topological thinking enables researchers to explore the governing spaces that emerge and operate through different modes of dataflows that contribute to reconstitute scales such as ‘federal’ and ‘local’, and the borders between them (Lewis and Hartong Citation2022).

Learning analytic platforms (LAPs) can also be analysed through spatial-temporalities. Webb, Sellar, and Gulson (Citation2020) highlight competing conceptions of time that LAPs have performed in anticipating futures. Specifically, LAPs collect and analyse vast amounts of data with the purpose of not only auditing students’ previous academic performance but also predicting their future learning outcomes (Gulson et al. Citation2022; Lewis, Holloway, and Lingard Citation2022). As such, LAPs are premised on and produce forms of anticipatory governance (ways of managing expectations so that they prescribe the policies then enacted) ‘through chronological computations of serial arrangements of past, presents, and futures’ (Webb, Sellar, and Gulson Citation2020, 288).

Nevertheless, even though there are multiple spatial-temporalities constituting new modes of educational governance, the values underpinning the design of standards and algorithms adopted in LAPs and recent policies remain the same. First, ‘the capacities of AI now accelerate the chronological epistemologies that have been used to govern education since the 1950s’ (Webb, Sellar, and Gulson Citation2020, 289). Second, ideas such as outcome-based performance and the development of human capital still remain central. ‘The integration of novel forms of data and the creation of new data platforms, in addition to the infusion of business principles into educational governance networks, produce intensified interactions between people, networks, algorithms and computational capacities’ (Webb, Sellar, and Gulson Citation2020, 287).

The notion of anticipatory governance has also been used by Robertson and Beech (Citation2023) to analyse, through a spatial–temporal lens, how international organisations use the future as a mode of legitimation and an instrument to govern educational spaces. They demonstrate how the OECD uses scenarios, forecasting, probabilistic modelling and other instruments of imagination to construct a particular vision of the future in the present. Through these fictional expectations (Beckert Citation2013), the OECD and other international organisations seek to position themselves as those capable of anticipating future educational challenges and finding the solutions to these problems. In this way, they seek to gain global legitimacy and help to promote and consolidate global policy spaces in education through calls for all educational systems to adapt to a single narrative about future challenges.

Through these examples, we can identify a shift of spatial-temporalities in educational governance. In the traditional governmental logic built on a belief in progress and linear time, macro-level statistics were used to interpret the past and act upon present education policies to influence the future (e.g. educational planning). In contrast, the PDD of education allows for the development of education futures based on the capacity to produce and analyse vast amounts of data about the minutiae of student and teacher behaviour and performance. The past is no longer perceived as being separated from the present but lives through both the present and the future enabled by the speed at which detailed micro-data can be collected and analysed through algorithms that reinscribe the past as a set of statistical representations from which trends and future scenarios can be constructed and used to establish and govern educational spaces almost in real time.

The impacts of global crises through a spatial lens

Over the past decade, our planet has experienced numerous global crises, facilitated in some degree by the technological trends and governance shifts outlined above. Here we consider, through a spatial lens, these crises, topics which Cowen (Citation2023) notes are ‘major silences’ in comparative education, which ‘have not entered our past very much, never mind our future’ (330). Today’s world faces increasing numbers of armed conflicts and wars, accelerating extinctions, groundwater depletion, mountain glacier melting, and unbearable heat due to the climate crisis and uninsurable futures. All these unsustainable pressures on our planet are exacerbated by (and contribute to) growing inequalities between and among groups of people even amidst growing economies (Piketty Citation2022). These crises have devastating impacts on education. For example, children and education systems are often on the front lines of armed conflict as populations are displaced, and schools and school children are viewed by combatants as legitimate targets. This has led to tens of millions of children and young people in crisis-affected countries being out of school (UNESCO Citation2023a).

One cannot discuss the world over the past decade without reference to the Covid-19 pandemic. The emergence of the novel coronavirus and its subsequent global spread resulted in a devastating pandemic, leading to millions of deaths, straining healthcare systems, causing economic disruptions, and prompting the widespread adoption of preventive measures like lockdowns, school closures, mask-wearing, and vaccination campaigns. During the height of the pandemic, 1.3 billion students were out of school around the world (UNESCO Citation2023a; Citation2023b).

What then can a spatial lens do to help facilitate our understanding of how education is entangled with these challenges our planet faces? And how can a spatial perspective potentially alert us to possibilities for envisioning an education that can contribute to more healthy and sustainable futures for both the human and beyond-human world?

Both social topological and spatial–temporal lenses help us understand how global flows of educational discourses and associated material elements contribute to the global spread of these crises. For example, our growth-based economic thinking and the belief that technology is the panacea that can solve all our problems have been promoted in topological ways along the globe through transnational educational infrastructures such as PISA (Komatsu, Rappleye, and Silova Citation2020).

A social topology analytical lens also sheds light on how stability and change took place together during the pandemic when various stringent policies were implemented across the world. Those policies seem to be different in form, but shared similarities in terms of reinforcing disparities between the privileged and the marginalised. Specifically, those who lived in poverty were impacted the most by those policies. Those who were not allowed to work from home did not get paid. Students who did not have Internet access could not participate in online courses. And women paid a high career price in terms of the additional demands made on them, compared to their male peers, in terms of assisting their children with online learning at home during the pandemic. Thus, even as new forms of learning (e.g. distance learning) and working (e.g. working from home) emerged, the form/shape of socio-economic and gender inequality essentially remained the same or was even reinforced.

Furthermore, social topology, beyond-human spatiality and spatial-temporalities theoretical lenses illustrate how the spread of digital technologies has been uneven and inequitable. First, social topology demonstrates how learning platforms, for example, can be transformed by local cultures, but at the same time, they preserve their essential properties in terms of, for example, how they package knowledge in a certain way (Dussel and Ferrante Citation2023). From a different angle, social topology with its focus on how relations are formed and endure despite conditions of continual change also illustrates how processes of platformisation both retain essential characteristics of what we have come to associate with modern schooling (a prescribed curriculum with a class of students taught by a teacher), but through a completely different format (online learning). And in doing so, continues to reproduce inequalities within and across nation-states associated with modern schooling such as the reproduction of English and Western knowledge as ‘superior’ forms of knowing.

Furthermore, a beyond-human spatial lens illustrates the ethical implications of the spread of PDD in education. In line with other spatial theorists, we call for attention to the environmental costs of the spread of digital technologies including the mining of materials for digital hardware and the ‘cloud’, spaces required for data storage, and e-waste, all of which contribute to pollution including greenhouse gas emissions. The impact of technology when the whole cycle of its deployment is considered, also includes the social costs of extraction, such as child labour in cobalt mines, and the unequal global distribution of the costs and benefits of digital technology’s use in educational settings (McKenzie and Gulson Citation2023; Werse Citation2023). These ecojustice (Werse Citation2023) issues are spatial as they make connections visible, but also as they are strongly linked to the global circulation of power in education. In this sense, the growing influence of Ed Tech giants such as Apple, Google Meta and Microsoft should not only be considered in terms of a shift in influence over educational practices, but also as contributing, at least in their current form, to the unsustainability of the world.

The spatiality of education is not only connected to the ethical challenges of our times through its link to ecojustice issues, but also in terms of how it interacts with growing global inequalities. Historically, education has been a key instrument in normalising and reproducing spatially unequal power relations, for example as a device for the legitimation of colonial and post-colonial exploitation. Epistemic injustice in which ‘legitimate’ knowledge flows through educational institutions from certain parts of the world to others is instrumental to the movement of students (and money) moving in the opposite direction. Mobilities of policies, technologies, knowledge, students, and expertise (in the form of brain drain/gain) can be read as education’s contribution to widening global inequalities.

Spatial scholars, Trauger and Fluri (Citation2021) propose the concepts of ‘zones of accumulation’ and ‘spaces of dispossession’ to consider how zones of wealth are relationally connected to spaces of poverty through extractive and colonial practices. These spatial categories are also helpful in avoiding methodological nationalism by noting that accumulation and dispossession operate at scales that cannot be simply equated with nation-states. In education, mobilities mentioned above could be analysed within this logic, but also, we could also consider how zones of educational privilege are relationally associated with spaces of educational dispossession. The chains of low-fee private schools for the poorest populations in the world promoted by networks of for-profit corporations, philanthropies, international organisations and entrepreneurs (Srivastava Citation2016) can also be seen spatially as connecting the educational needs of the most disadvantaged with the profit-making appetite of global capital, perpetuating and extending geopolitical differences and post-colonial practices in education.

Conclusion

We started this article by noting that space is central to comparative education and calling for comparativists to stretch and extend how they use space theoretically in our field. We then presented our key premises about spatial theories derived from social topology, spatial-temporalities, and beyond-human spatialities. These approaches alert us to the fact that space is relational, dynamic, continuously unfolding, and productive. In conceiving space as a product of interrelationships we are stretching our previous research (Beech and Larsen Citation2014; Larsen and Beech Citation2014) to illustrate how space needs to be understood in relationship with time(s), humans and beyond human worlds.

To illustrate these points, we then discussed some prominent work that has used these spatial lenses to analyse technological changes, shifts in governance and the impacts of global crises and the complicated ways in which they are spatially related to education. In particular, we pointed out the relational ways in which space produces and shapes social and educational practices. Through these analyses we demonstrated how these processes produce new spaces of governance that are unstable and unequal. While they provide new learning opportunities and could potentially improve access to knowledge, they are based on an economic logic that can have damaging consequences for those involved in educational enterprises, as well as our planet as a whole.

We end our article with some spatial words of hope. Massey (Citation2005) writes that thinking about the spatial as being relational and productive ‘can shake up the manner in which certain political questions are formulated, can contribute to political arguments already under way, and – most deeply – can be an essential element in the imaginative structure which enables in the first place an opening up to the very sphere of the political’ (9). Liberating space from its old fixed, narrow meanings and understanding space as open, relational and always in a state of becoming is more productive, more political, and even more hopeful. Indeed, this is not solely an academic exercise in developing new vocabularies and new theories, but also a call to use those tools to re-imagine education to help us learn how to live in relationship with all others, human and beyond.

Paying attention to the entanglements of education with the more than human is an important ethical move. It illustrates a way forward for us to live our moral ‘response-abilities as [entangled beings] through multi-species, more-than-human generations’ (Wright et al. Citation2020, 302). Being fully human is about a deep understanding of our interrelationships with time, with one another and the natural world; and recognising the impacts of our actions on this planet we inhabit. From a spatial perspective that shines a light on the inequalities and injustices that have spread more widely over the last decades, we see a need to co-produce with all living beings a better world. In this respect, spatial theoretical lenses inhabit a sphere of possibility for educational futures that have the potential to help us slow down, repair and restore broken relationships between ourselves and our beyond-human world. This is an ethical quest in shifting our ontological thinking about the nature of space today, and our epistemological practices in considering how we can stretch our spatial lenses to study and potentially change a world soaked in spatiality in relation to all living beings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgement

We are deeply grateful to Dr. Robert Cowen who continued to inspire and support us in the writing of this article right up until days before he passed away in 2023.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jason Beech

Jason Beech is an Associate Professor in Global Policies in Education at the Faculty of Education, University of Melbourne and Visiting Professor at Universidad de San Andrés in Buenos Aires where he holds a UNESCO Chair in Education for Sustainability and Global Citizenship. His research focuses on the globalisation of knowledge and policies related to education. He has also written and is passionate about the challenges of educating for global citizenship and a sustainable future.

Marianne A. Larsen

Marianne A. Larsen is a Professor Emerita from the Faculty of Education, Western University. Her research has focused on the internationalisation of higher education, teacher education, international higher education research partnerships, and academic mobilities. She has a long-standing interest in writing about how we can rethink the work we do as comparative education scholars, methodologically, theoretically, and ethically. Currently, she is serving as an elected public school board trustee in Ontario, Canada.

Wei Wei

Wei Wei is a graduate of the Faculty of Education, Western University. Her doctoral research focused on the transfer of leadership standards and its contextualisation in China. Currently, she is based in Beijing, China and continues to research and publish on the cultural politics of policy mobilities and the modes of educational governance driven by the datafication and platformisation in education.

Notes

1 To create this bar chart, we searched for the combination of two keywords, ‘spatial theory’ and ‘education’, in Web of Science to identify related publications focusing on the topic of spatial theory in the area of education. Our search covered databases including Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Citation Index, and Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science. presents the numbers of publications respectively from 2014 to May 2024, over which time there have been over 770 publications focusing on space in relation to education.

2 Topology and geometry are closely related mathematical subjects dealing with space. However, geometry deals with Euclidean objects that have definite shape and clear angles, area, volume, etc. Topology as non-standard geometry is concerned with the intrinsic properties of spatial configurations that remain the same when deformed. In other words, topology is about connections or relations between the properties of a form/figure.

References

- Addey, Camilla, and Radhika Gorur. 2020. “Translating PISA, Translating the World.” Comparative Education 56 (4): 547–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2020.1771873.

- Atkinson, Will. 2019. “Time for Bourdieu: Insights and Oversights.” Time & Society 28 (3): 951–970. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X17752280.

- Beckert, Jens. 2013. “Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations in the Economy.” Theory and Society 42 (3): 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-013-9191-2.

- Beech, Jason, and Marianne A. Larsen. 2014. “Replacing Old Spatial Empires of the Mind: Rethinking Space and Place Through Network Spatiality.” European Education 46 (1): 75–94. https://doi.org/10.2753/EUE1056-4934460104

- Borduas, Chris, Michael Kehler, and Gabriel Knott-Fayle. 2023. “School Spaces, School Places: Shifting Masculinities During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” International Journal of Educational Research 120 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2023.102211.

- Bryant, Levi R. 2014. Onto-cartography. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2021. The Climate of History in a Planetary Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Conner, Steven. 2004. “Topologies: Michel Serres and the Shapes of Thought.” Anglistik 15: 105–117.

- Cowen, Robert. 2009. “The Transfer, Translation and Transformation of Educational Processes: And Their Shape-Shifting?” Comparative Education 45 (3): 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060903184916.

- Cowen, Robert. 2023. “Comparative Education: And Now?” Comparative Education 59 (3): 326–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2023.2240207.

- Decuypere, Mathias, Sigrid Hartong, and Karmijn van de Oudeweetering. 2022. “Introduction―Space-and Time-Making in Education: Towards a Topological Lens.” European Educational Research Journal 21 (6): 871–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041221076306.

- Decuypere, Mathias, and Steven Lewis. 2023. “Topological Genealogy: A Methodology to Research Transnational Digital Governance in/Through/as Change.” Journal of Education Policy 38 (1): 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2021.1995629.

- Decuypere, Mathias, and Maarten Simons. 2016. “Relational Thinking in Education: Topology, Sociomaterial Studies, and Figures.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 24 (3): 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2016.1166150.

- Deleuze, Gillies. 1994. Difference and Repetition. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Dussel, Inés, and Patricia Ferrante. 2023. “Global Connective Media: YouTube as an educational infrastructure.” In Globalization and the Shifting Geopolitics of Education. Vol 1. of the Elsevier International Encyclopaedia of Education, edited by Fazal Rizvi and Jason Beech, 622–629. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Gorur, Radhika. 2011. “Policy as Assemblage.” European Educational Research Journal 10 (4): 611–622. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2011.10.4.611

- Gulson, Kalervo N. 2015. “Relational Space and Education Policy Analysis.” In Education Policy and Contemporary Theory, edited by Kalervo N. Gulson, Matthew Clarke, and Eva Bendix Petersen, 219–229. London: Routledge.

- Gulson, Kalervo N., Dan Cohen, Steven Lewis, Emma Rowe, Ee Seul Yoon, and Chris Lubienski. 2022. “Spatial Theories, Methods and Education Policy.” In International Encyclopedia of Education: Fourth Edition, edited by Rob Tierney, Fazal Rizvi, and Kadriye Ercikan, 9–36. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Gulson, Kalervo N., and Sam Sellar. 2019. “Emerging Data Infrastructures and the New Topologies of Education Policy.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (2): 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818813144.

- Hartong, Sigrid. 2018. “Towards a Topological Re-assemblage of Education Policy? Observing the Implementation of Performance Data Infrastructures and ‘Centers of Calculation’ in Germany.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 16 (1): 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2017.1390665.

- Kallio, Kirsi Pauliina. 2021. “Topological Mapping: Studying Children’s Experiential Worlds Through Spatial Narratives.” In Narrating Childhood with Children and Young People: Diverse Contexts, Methods and Stories of Everyday Life, edited by Lisa Moran, Kathy Reilly, and Bernadine Brady, 329–352. Cham: Springer.

- Komatsu, Hikaru, Jeremy Rappleye, and Iveta Silova. 2020. “Will Education Post-2015 Move us Toward Environmental Sustainability?” In Grading Goal Four Tensions, Threats, and Opportunities in the Sustainable Development Goal on Quality Education, edited by Antonia Wulff, 297–321. Leiden: Brill.

- Larsen, Marianne A., and Jason Beech. 2014. “Spatial Theorizing in Comparative and International Education Research.” Comparative Education Review 58 (2): 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1086/675499

- Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor–Network Theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 2018. Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Lewis, Steven. 2020. “New Topological Spaces and Relations of the OECD’s Global Educational Governance.” In PISA, Policy and the OECD, Respatialising Global Educational Governance Through PISA for Schools, edited by Steven Lewis, 171–188. Singapore: Springer.

- Lewis, Steven, and Sigrid Hartong. 2022. “New Shadow Professionals and Infrastructures Around the Datafied School: Topological Thinking as An Analytical Device.” European Educational Research Journal 21 (6): 946–960. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041211007496.

- Lewis, Steven, Jessica Holloway, and Bob Lingard. 2022. “Emergent Developments in the Datafication and Digitalization of Education.” In Reimagining Globalization and Education, edited by Fazal Rizvi, Bob Lingard, and Risto Rinne, 52–78. New York: Routledge.

- Lewis, Steven, and Bob Lingard. 2023. “Platforms, Profits and PISA for Schools: New Actors, By-passes, and Topological Spaces in Global Educational Governance.” Comparative Education 59 (1): 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2022.2145006

- Lewis, Steven, Glenn Savage, and Jessica Holloway. 2020. “Standards Without Standardisation? Assembling Standards-Based Reforms in Australian and US Schooling.” Journal of Education Policy 35 (6): 737–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1636140

- Lewis, Steven, Sam Sellar, and Bob Lingard. 2016. “PISA for Schools: Topological Rationality and New Spaces of the OECD’s Global Educational Governance.” Comparative Education Review 60 (1): 27–57. https://doi.org/10.1086/684458

- Lingard, Bob. 2019. “The Global Education Industry, Data Infrastructures, and the Restructuring of Government School Systems.” In Researching the Global Education Industry: Commodification the Market and Business Involvement, edited by Marcelo Parreira do Amaral, Gita Steiner-Khamsi, and Christiane Thompson, 135–155. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave, Macmillan, Springer Nature.

- Lingard, Bob. 2022. “Relations and Locations: New Topological Spatio-Temporalities in Education.” European Educational Research Journal 21 (6): 983–993. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041221076323.

- Lingard, Bob, and Greg Thompson. 2017. “Doing Time in the Sociology of Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2016.1260854.

- Lury, Celia, Luciana Parisi, and Tiziana Terranova. 2012. “Introduction: The Becoming Topological of Culture.” Theory, Culture & Society 29 (4-5): 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276412454552.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- McKenzie, Marcia, and Kalervo N. Gulson. 2023. “The Incommensurability of Digital and Climate Change Priorities in Schooling: An Infrastructural Analysis and Implications for Education Governance.” Research in Education 117 (1): 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/00345237231208658.

- Piattoeva, Nelli. 2018. “How Can Transnational Connection Hold? An Actor- Network Theory Inspired Approach to the Materiality of Transnational Education Governance.” In Education Governance and Social Theory. Interdisciplinary Approaches to Research, edited by Andrew Wilkins and Antonio Olmedo, 103–119. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2022. A Brief History of Equality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rappleye, Jeremy, and Hikaru Komatsu. 2020. “Towards (Comparative) Educational Research for a Finite Future.” Comparative Education 56 (2): 190–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2020.1741197.

- Robertson, Susan L., and Jason Beech. 2023. “‘Promises Promises’: International Organisations, Promissory Legitimacy and the re-Negotiation of Education Futures.” Comparative Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2023.2287938.

- Salajan, Florin D., and Tavis Jules. 2022. Comparative and International Education (re) Assembled: Examining a Scholarly Field Through an Assemblage Theory Lens. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Seddon, Terri. 2023. “Comparative Comparative Education Concepts, Methods and Practices in the Emerging Anthropocene Educational Space: From ‘Measuring the Other’ to ‘Supporting the Other’?” Comparative Education 59 (3): 436–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2023.2215643

- Sellar, Sam, and Kalervo N. Gulson. 2018. “Dispositions and Situations of Governance: The Example of Data Infrastructure in Australian Schooling.” In Education Governance and Social Theory. Interdisciplinary Approaches to Research, edited by Andrew Wilkins and Antonio Olmedo, 63–82. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Sellar, Sam, and Kalervo N. Gulson. 2021. “Becoming Information Centric: The Emergence of new Cognitive Infrastructures in Education Policy.” Journal of Education Policy 36 (3): 309–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1678766

- Siemens, George, and Dragan Gašević. 2012. “Guest Editorial – Learning and Knowledge Analytics.” Educational Technology & Society 15: 1–2.

- Silova, Iveta. 2019. “Toward a Wonderland of Comparative Education.” Comparative Education 55 (4): 444–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2019.1657699.

- Silova, Iveta. 2021. “Facing the Anthropocene: Comparative Education as Sympoiesis.” Comparative Education Review 65 (4): 587–616. https://doi.org/10.1086/716664.

- Srivastava, Prachi. 2016. “Questioning the Global Scaling Up of Low-Fee Private Schooling: The Nexus Between Business, Philanthropy and PPPs.” In The Global Education Industry—World Yearbook of Education 2016, edited by A. Verger, C. Lubienski, and G. Steiner-Khamsi, 248–263. New York: Routledge.

- Trauger, Amy, and Jennifer Fluri. 2021. “Zones of Accumulation Make Spaces of Dispossession: A New Spatial Vocabulary for Human Geography.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 20 (1): 1–16.

- UNESCO. 2021. “The Platformization of Education: A Framework to Map the New Directions of Hybrid Education Systems.” https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377733.locale=en.

- UNESCO. 2023a. “What You Need to Know About Education in Emergencies.” https://www.unesco.org/en/emergencies/education/need-know.

- UNESCO. 2023b. “Dashboards on the Global Monitoring of School Closures Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic.” https://covid19.uis.unesco.org/global-monitoring-school-closures-covid19/.

- van Dijck, José, Thomas Poell, and Martijn de Waal. 2017. The Platform Society. New York: Oxford Academic.

- Webb, P. Taylor, Sam Sellar, and Kalervo N. Gulson. 2020. “Anticipating Education: Governing Habits, Memories and Policy-Futures.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (3): 284–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1686015.

- Web of Science. 2024. “Growth in Publications on Spatial Theories and Education Since 2014.” Retrieved from https://www-webofscience-com.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/wos/woscc/citation-report/7560828c-8a06-4e99-b540-cb84232c2dca-d981e282.

- Werse, Nicholas R. 2023. “The Quest to Cultivate an Ecocritical Awareness in Educational Technology Scholarship: A Question of Disciplinary Focus in the age of Environmental Crisis.” British Journal of Educational Technology 54 (6): 1878–1894. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13327

- Williams, James. 2011. Gilles Deleuze's Philosophy of Time: A Critical Introduction and Guide. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Bawaka Country, S. Wright, S. Suchet-Pearson, K. Lloyd, L. Burarrwanga, R. Ganambarr, M. Ganambarr-Stubbs, B. Ganambarr, and D. Maymuru. 2020. “Gathering of the Clouds: Attending to Indigenous Understandings of Time and Climate Through Songspirals.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 108: 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.05.017.