ABSTRACT

How do international norms affect respect for human rights? We report the results of an audit experiment with foreign missions that investigates the extent to which state agents observe international norms and react to the potential of international shaming. Our experiment involved emailing 669 foreign diplomatic missions in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom with requests to contact domestic prisoners. According to the United Nations, prisoners have the right for individuals to contact them. We randomly varied (1) whether we reminded embassies about the existence of an international norm permitting prisoner contact and (2) whether the putative email sender is associated with a fictitious human rights organization and, thereby, has the capacity to shame missions through naming and shaming for violating this norm. We find strong evidence for the positive effect of international norms on state respect for human rights. Contra to our expectations, though, we find that the potential of international shaming does not increase the probability of state compliance. The positive effect of the norms cue disappears when it is coupled with the shaming cue, suggesting that shaming might have a ‘backfire’ effect.

How do international norms affect state respect for human rights? The theoretical literature argues that states’ compliance with human rights norms is induced by a socialization process through which compliance is encouraged by “diplomatic praise or censure … which is reinforced by material sanctions and incentives” (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998). After a sufficient number of states are persuaded by norm entrepreneurs to adopt a new international norm, other states experience an effect similar to “peer pressure”, which induces them to adhere to this new norm. One possible explanation for the effectiveness of this mechanism is that states want to demonstrate that they are legitimate members of the international human rights regime. Another possible explanation is that leaders want to make a good international impression in order to “enhance national esteem” (Creamer and Simmons Citation2015; Hill Citation2010).

Perhaps the most convincing explanation, though, is that states abide by international norms to placate other international actors who also act as agents of socialization (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998). This is particularly true in the case of human rights organizations (HRO), who can “name and shame” regimes that do not comply with international standards. Although HROs have limited power to directly sanction regimes, they can impose reputation costs on a regime by shaming them and thereby help spur public condemnation that might lead to the imposition of sanctions, such as decreased multilateral aid allocations (Lebovic and Voeten Citation2009). This suggests that while other factors might influence state compliance with international norms, compliance should be higher in the presence of HRO oversight. In line with this logic, “naming and shaming” campaigns are considered to be one of the best strategies for enforcing human rights norms (Brysk Citation1993; Keck and Sikkink Citation1998).

While these theoretical claims about the influence of international norms and shaming are intuitively appealing, the empirical support for these effects is less clear. One problem is that many studies rely on observational research designs, from which it is often difficult to make causal claims. Moreover, the effect of norms and shaming on some rights—such as empowerment rights or prisoners’ rights—remains almost wholly unstudied. We address these possible issues by focusing on prisoner’s rights and leveraging an experimental design.

We also re-focus the analysis by looking at the state agents who implement policy. The literature on norms and shaming has focused on state-level analyses of how the executive or judiciary responds to international norms or shaming. Less consideration has been given to whether state agents respect human rights in practice. This is potentially an important oversight, as individual state agents have considerable influence over human rights practices (Lipsky Citation2010). There is a growing appreciation that studying state agents can facilitate a more robust understanding of human rights practices.

To address these gaps in the literature, we conducted a field experiment with foreign embassies. We designed the experiment to examine (1) the effect of international norms and (2) the effect of potential shaming on respect for prisoners’ rights. We conducted the experiment by emailing foreign diplomatic missions in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom with requests to contact domestic prisoners, a right acknowledged by the United Nations. To test the effect of norms, we randomly varied whether we reminded embassies about the existence of an international norm permitting prisoner contact. To test the effect of possible shaming, we randomly varied whether the putative email sender is associated with a fictional HRO. The benefit of our research design is that it allows us to identify the causal effects of norms and shaming, while also examining how state agents respond to these factors.

Our results suggest that international norms have a strong effect on respect for human rights. Contra to expectation, though, we find that the potential of international shaming does not increase the probability of state compliance. Indeed, the positive effect of the norms cue disappears when it is coupled with the shaming cue, suggesting that shaming might have a ‘backfire’ effect.

This paper makes several contributions to the human rights literature. First, we situate prisoner’s right within existing conceptualizations of human rights. Second, we focus on agents of the state in understanding human rights practices. Third, we provide empirical evidence for the effect of international norms on the behavior of state agents. This evidence suggests that international institutions can influence respect for human rights by creating self-enforcing norms. Fourth, we find that efforts to induce human rights compliance may have unintentionally deleterious consequences. These contributions have clear policy implications for HROs and states seeking to influence respect for human rights.

Theory and Hypotheses

There are several ways to think about international human rights law. Some scholars argue that it affects states’ behavior through obligation, rule-making, and delegation (Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter, and Snidal Citation2000). Critics of this “naive legalism” apply a regulative model to international law, assessing law’s effectiveness in terms of its ability to regulate, constrain, or directly alter the behaviors of state leaders (Goldsmith and Krasner Citation2003). Recent improvements in human rights and the development of human rights law suggest, however, that the most promising way of thinking about international law is the constitutive model. In this view, international law is constituted by, and generative of, political struggles between the powerful (state) and the weak (rights claimants) (Dancy and Fariss Citation2017). The constitutive model assumes that international law does not need centralized enforcement (Dancy and Fariss Citation2017). The proponents of this model emphasize the jurisgenerative power of international human rights norms to serve as a local framework for these political interactions (Benhabib Citation2009; Dancy and Fariss Citation2017). These political struggles occur not only within states but outside of sovereign boundaries as well. Adoption of a norm by a large number of states redefines the appropriate behavior of other states as members of the international community in the process of socialization. In this context, socialization can be considered as a “mechanism through which norms leaders persuade others to adhere” ((Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998: 902). States’ adherence to international norms is one of the sources of international legitimation, which in turn contributes to the government’s domestic basis of legitimation. In other words, states’ compliance with international norms affects the compliance of their own citizens with government rules and law (Buchanan Citation2007).

In addition, human rights law is a basis for a number of transnational social movements and HROs—agents of socialization (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998). These groups promote human rights norms implementation by pressuring target states and monitoring their compliance. For instance, transnational advocacy groups use a variety of tactics, including generating politically usable information and mobilizing it around their policy targets, using symbolic interpretation in order to raise awareness about norms violation, seeking the leverage over more powerful actors, and holding powerful actors accountable to their pronouncements, to the law, and to their contracts related to human rights (Keck and Sikkink Citation1998).

All of these tactics are used in “naming and shaming” campaigns, perhaps the most effective method in human rights norms enforcement (Brysk Citation1993). These campaigns can induce policy change through several mechanisms. Shaming reports are likely to have a significant impact on public opinion of human rights conditions, spurring policy change from the bottom-up (Ausderan Citation2014; Dietrich and Murdie Citation2017). HROs can also generate incentives for aid officials and institutions to change aid policy (Dietrich and Murdie Citation2017). For example, “shaming” in the UNCHR through resolutions that explicitly criticize governments for their human rights record tend to result in the reduction of multilateral aid received by the targets of these resolutions (Lebovic and Voeten Citation2009).

The existing literature, however, provides us with little rigorous, empirical evidence that norms and shaming influence human right practices. Furthermore, most of the literature focuses solely on international-level politics, overlooking the political processes that occur inside states. More recent studies argue that analyzing norm implementation at the domestic level can be a more fruitful approach for human rights research (Krook and True Citation2012; Zimmermann Citation2016). International norms tend to be vague, which enables their content to be interpreted in many ways and subjected to different framing by various international and domestic actors. According to this literature, it is the ability of norms to contain different meanings that can be one of the explanations for both the speed of the norms diffusion and for the gap between the normative institutionalization and norms implementation (Betts and Orchard Citation2014; Sandholtz Citation2008; Wiener Citation2004).

This relatively recent shift toward domestic-level explanations can partially explain why the role of state agents in human rights practices has been undertheorized. We would expect, however, the effect of norms on state behavior to manifest in the decisions of individuals when they act as state representatives in bureaucratic entities. For instance, Lipsky (Citation2010) argues that the attitudes and behaviors of street-level bureaucrats are affected by norms, which are usually derived from the society within which the bureaucratic agents live and work. Marrow (Citation2009), citing Lewis and Karthick Ramakrishnan (Citation2007), makes a similar point: “Likewise, some of the inclusive, service-oriented professional norms that affect bureaucrats’ behaviors today – such as ideals of pluralism and diversity in schools and the ideal of community policing in law enforcement – have grown out of past electoral political pressures.”

In the process of professionalization, transnational advocacy networks influence individuals either directly or indirectly through the leaders of their political regime. In particular, they do this by promoting professional norms and shared values and by providing technical assistance. As a result, states are subjected to pressure from international authorities and are encouraged to adopt and respect international norms to benefit from their membership in the international community. Thus, naming and shaming campaigns change leader and regime behavior by affecting their incentives, including their reputation, domestic and/or international legitimacy, and foreign aid or foreign direct investment (Bush Citation2011). Bureaucratic agents are central to the implementation of new policies adopted by leaders (Meier and O’Toole Citation2006). Due to professional incentives, bureaucratic agents should be aware of human rights-related norms and therefore be receptive to their usage (Lewis and Karthick Ramakrishnan Citation2007; Lipsky Citation2010). This leads us to our International Norms Hypothesis.

International Norms Hypothesis: State agents will exhibit greater compliance when reminded about international norms.

While HROs do not have enforcement power over rights perpetrators, they have the ability to shame them by putting their violations in the international spotlight. They also can raise their concerns with more powerful actors, such as international organizations, that have leverage over states and affect their behavior. For example, Murdie and Peksen (Citation2013) show that HRO activities increase the likelihood of economic sanctions against repressive regimes through information production and local population empowerment.

Following Lewis and Karthick Ramakrishnan (Citation2007), we expect bureaucratic agents who work at foreign embassies to be more receptive to human rights-related requests when there is a possibility of punishment. This expectation is captured in our Shaming Hypothesis.

Shaming Hypothesis: State agents will exhibit greater compliance when the requester’s profession is associated with a possibility of shaming the state.

In line with the literature, we also expect that the effects of international norms and shaming are reinforcing. This means that the positive effect of norms on compliance should increase when coupled with the prospect of shaming. This logic is outlined in the Conditional International Norms and Shaming Hypothesis.

Conditional International Norms and Shaming Hypothesis: The positive effect of reminding state agents about international norms is greater when the requester has a perceived ability to shame the state than when they do not.

Research Design

To test our theoretical expectations we conduct an audit experiment with a sample of foreign missions. The benefit of our research design is that it allows us to identify the causal effects of norms and the possibility of shaming.

Prisoner’s Rights

We selected the topic of prisoner’s rights for our correspondence because according to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, prisoners have the right for individuals to contact them. In asking the embassy personnel to put us in touch with a prisoner, it is within the power of the state agent to facilitate the exercise of this right.

Prisoner’s rights are not codified in international treaties, and as such fall under human rights soft law. Soft law is generally understood as non-binding and the legal basis of commitments articulated under soft law is often contested within a public international law framework. This raises a couple of issues. First, there is the question of whether state agents will be familiar with the norm that prisoners have the right to communicate with the outside world. If not, they may be disinclined to grant our request; another way of thinking about this is that the norms cue may be a weak treatment. We return to this issue in the analysis.

The second issue relates to what sort of theoretical traction we can obtain by studying a soft right; how well can our findings travel to other rights regulated under international human rights law? Our take is that by studying soft rights, we are putting our theory to a hard test since soft rights are the least likely to be normatively consolidated and violations cannot lead to formal sanctioning (although they can plausibly induce reputation costs). This leads us to speculate that if we indeed find that reminding state agents about soft rights induces compliance, we would theoretically expect the finding to travel to rights protected under international treaties.

Sample

Our population of interest consists of the 1098 foreign missions and consulates general in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom.Footnote1 We selected missions and consulates in these countries because they exhibit similarly high levels of state respect for human rights. The idea here is to observe how bureaucrats from foreign regimes respond to international norms and the threat of sanctioning in contexts where the public and political elites strongly support human rights issues. In such places, we would expect the power of norms and potential sanctions to be at their highest. In that sense, we conduct an “easy test” of our theory: if the relationships that we are looking for exist, we should find them in these places.

We attempted to collect email addresses for this census of missions. Many missions, however, do not provide general email addresses for public correspondence. We exclude these from our sample. Some missions, on the other hand, list the same email address as other missions. In this case, we randomly dropped all but one of the missions from our sample. Additionally, some missions either listed obviously incorrect email addresses or provide email addresses that did not work. We also excluded those from our sample. Our final sample then consisted of 669 missions. It consists of 246 embassies and 423 consulates that cover 155 countries in the 3 host countries in our sample.

Before sending emails to foreign missions, we spoke with staffers at several of them. Our goals were to (1) determine who replies to emails like the ones we were about to send and to (2) assess the believability of our email requests. We learned that emails are generally answered by foreign staff, particularly in consulates, where local national staff numbers are often small. We also learned that foreign missions receive many emails every day dealing with a wide variety of subjects and each typically receives a reply. Based on the descriptions of these emails, we have little reason to think that ours stood out as odd. This is even more likely because our understanding of the daily workflow for most staff suggests that they had little time to assess the believability of our emails.

Experimental Design

As specified in our pre-registration plan, the study occurred over three waves. In the first wave, we emailed foreign missions with a basic request. We did this to establish a baseline response rate. presents the email text used in wave one. While we kept the text of the email the same, we randomized the separators, such as white space, valediction, and sender identity.Footnote2 We did this to preserve participant naivety and to minimize the possibility of spillover. We delivered these emails from April 27 to April 28, 2016.

In the second wave, we sent each mission a request for information about contacting domestic prisoners. We selected this topic for our correspondence because according to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, prisoners have the right for individuals to contact them. Each email contained this request along with a set of randomized cues designed to test our theoretical expectations.

To test our four hypotheses, we used a 2 × 2 factorial design. The first factor varies whether or not we include a norms reminder. This is indicated by language that reminds the recipient of the acknowledged right that prisoners have to communicate with the outside world. The idea here is that reminding recipients of this norm might increase norm compliance.

The second factor varies the extent to which we signal our ability to shame the recipient for disregarding our request. This is indicated by whether the putative sender works as a social sciences teacher or for a fictional human rights advocacy group. The idea here is that an advocacy group has a greater ability to highlight, and possibly shame, a recipient’s unhelpfulness than a sender in some other line of work, such as a teacher.

Importantly, we do not specify the name of the HRO in our email. We omitted this information because we wanted to be able to separate the effect of shaming capacity from any particular effects related to specific HROs. It is possible that we might find different results if we had claimed to write on behalf of a specific HRO. Indeed, the effects might vary across HROs. We think that examining the potential conditionality of this treatment might be a fruitful area of future research.

presents the cues. As in the first wave, we randomized the separators, valediction, and sender identities.Footnote3 presents the email text used in wave two. We sent these emails on May 2, 2016.

Table 1. Request texts

We block randomized our treatments based on a key pre-treatment covariate plausibly predictive of mission responsiveness—the mission’s host country (Moore and Schnakenberg Citation2012). The intuition here is that missions might respond at different rates across these countries because of local norms, such as expectations about political elite communication.

In the third wave, which occurred a week after the first and second waves, we emailed all missions with a reminder about our request to contact prisoners. We sent them the same emails as in wave two but added to the top of each email a sentence stating that we were following up on our previous request.Footnote4 We did this because our pre-experiment interviews with diplomatic staff suggested that since they receive many requests we should be persistent with our requests. presents the email text used in wave three. We sent these emails on May 6, 2016.

After sending the third wave emails, we waited two weeks to receive replies. We then collected our outcome measures. As indicated in our pre-registration plan, we collected two outcome measures. The first, Email Response is coded 1 if missions reply to our email and 0 otherwise. While we think that this is an informative outcome—real-world email senders would rather want their emails to be replied to than not—we also know that senders typically care about the contents of the emails they receive. In this case, they would want helpful replies. Examining whether our treatments have an effect on that outcome, though, is difficult because email response is a post-treatment outcome and conditioning on it “derandomizes the experiment”. We circumvent this problem by creating a second outcome measure, Helpful Email, which is coded 1 if missions send a helpful reply to our email and 0 otherwise. This means that unhelpful responses and non-replies are both coded as 0. We distinguish helpful replies and unhelpful replies based on whether they provide actionable information. A common example of this is contact information for a national Prison and Probation Service headquarters. A typical example of an unhelpful reply is one that advises us to consult Google.

Results

The overall response rate for our experimental emails was 29.30%. This is slightly higher than the response rate for our baseline emails (24.36%). In general, this reply rate is in line with response rates from audit experiments with elites (Costa Citation2017). Taken together, these two facts suggest that our emails were taken at face value.

As expected, the response rates differ by treatment condition. presents the raw response rates. Shaming denotes emails that received the shaming condition, Norms denotes emails that received the norms reminder condition, and Norms and Shaming denote emails that received both conditions. The table shows that compared to the control email, responses were slightly higher for emails that contained the shaming cue and much higher for emails that contained the norms cue. Indeed, the raw response rate for emails with the norms cue is 185% the raw response rate for control emails. These two patterns are in line with our theoretical expectations. On the other hand, the response rate is slightly lower for emails with both the norms and shaming cues, which runs counter to our expectations.

Table 2. Raw response rates

To investigate the effect of individual treatments, we estimate a linear probability model (LPM). We use an LPM because estimates are unbiased if the model is correctly specified and because the results are easy to interpret (Wooldridge Citation2010).Footnote5 Our models include treatment indicators, the blocking covariate, and fixed effects for the other randomized aspects of our email texts.Footnote6 The reference category for this model is the control condition that contains no reminder about international norms and comes from a putative social studies teacher. To account for heterogeneity in the error term, we use Bell-McCaffrey adjusted standard errors as recommended by Lin and Green (Citation2016).Footnote7

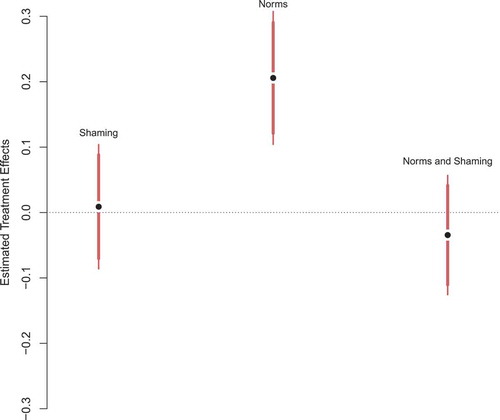

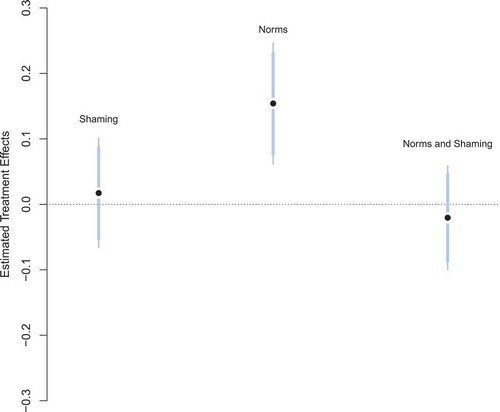

displays the results of this model.Footnote8 Black plotted points represent estimated coefficients, thick red bars represent 90% confidence intervals, and thin red bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The size and direction of the estimated coefficients are in line with the raw response patterns in . The estimate for the shaming treatment is positive, as we would expect, but is estimated imprecisely. We cannot reject the null that our shaming cue has no effect on state agent compliance.Footnote9

On the other hand, there appears to be strong evidence for the International Norms Hypothesis. This is indicated by the positive and statistically significant coefficient on the Norms coefficient (p value <.01). The effect of this cue is substantively meaningful. It increases the probability of receiving a reply by approximately 21%. This means that a basic reminder about the existence of an internal norm has a large, important effect on state compliance. Earlier, we raised the question of whether the norms treatment would be weak due to the soft law status of prisoner’s rights. The findings suggest this not to be the case; recipients were willing to take our invocation of UN standards at face value, resulting in a higher probability of response.

Contrary to our expectations, though, the combined effect of these cues is lower than the effect of the Norms cue. In other words, the norms cue on its own does more to increase compliance than the norms cue combined with the shaming (potential sanctions) cue. One possible explanation for this counterintuitive finding is that when the treatments are combined it creates a ‘backfire’ effect. The intuition here is that when missions receive both cues, they might prefer not to respond at all than to reply in a way that will not satisfy the research officer of a human rights advocacy group.

Next we examine whether our treatments affect our other outcome measure—Helpful Response. As a reminder, this outcome is coded 1 if we receive a helpful response and 0 otherwise, and we defined a helpful reply as one that provides actionable information. In effect, our coding rule means that we recode Email Response so that unhelpful replies are coded as 0. Approximately 20% of the missions sent us a helpful response.

The raw helpful reply rates mirror the email response rates. Emails that contained the shaming or norms reminder cues were more likely to receive a helpful reply, while emails that contained the compound treatment were less likely to receive a helpful reply. We again investigate the effect of individual treatments by estimating an LPM with BM-adjusted standard errors. displays the results of this model.Footnote10 Black plotted points represent estimated coefficients, thick blue bars represent 90% confidence intervals, and thin blue bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Again we find little evidence for our Shaming Hypothesis; nor is the Conditional International Norms and Shaming Hypothesis supported. This is indicated by the imprecise estimates on the Shaming and Norms and Shaming cues. There is, however, strong evidence for the International Norms Hypothesis. This is indicated by the large and statistically significant Norms coefficient (p value <.01).

Treatment Effect Heterogeneity

We expected treatment effects to be heterogeneous. In particular, we anticipated that the treatment effect would be lower for missions from autocratic countries than for missions from democratic countries, as well as for missions from states that routinely violate human rights than states that do not. We find little evidence, however, that these country-level characteristics influence the effect of treatments on either of our outcome measures. As pre-specified, we also investigate in an exploratory fashion whether treatment effects vary as a function of the global region in which states are located. Again, we find little evidence that treatment effects are conditional on these characteristics. We interpret the lack of evidence for treatment effect heterogeneity as a sign that the strategic calculus of mission responsiveness is widely shared.

Conclusion

Having conducted an audit experiment with foreign missions, we find strong evidence for the effect of international norms on state respect for prisoners’ rights. A simple reminder about the norm significantly increased both mission response rates as well as the helpfulness of the response. However, we find little evidence for an independent effect of shaming.

Most surprisingly, and counter to our expectations, we find that when we combine the norms and shaming cues, the effect is much smaller (and in opposite sign) than the effect for norms alone. This suggests a ‘backfire’ effect, where mission personnel who received the shaming and norms cues were deterred from replying. We speculate that when bureaucrats at foreign missions receive both cues, they might prefer not to respond than to reply in a way that might be unsatisfying to an individual with potential shaming power. In effect, a non-reply is less risky to the career of a bureaucrat than a reply.

The results from our experiment contribute to the human rights literature by providing empirical evidence for the effect of international norms on the behavior of state agents. This evidence is consistent with the constitutive model of international law and suggests that international institutions can affect state behavior by creating self-enforcing norms. Furthermore, these findings provide partial evidence for the effect of international norms and the possibility of shaming on the individual level. This suggests that researchers should devote more attention to street-level bureaucrats, who are commonly tasked with implementing state policy. For this reason, and because state agents are typically the individuals that citizens are most likely to interact with, they play a central role in whether human rights are respected in practice. Finally, the results suggest that state compliance with some human rights norms is not always conditional on such state characteristics like regime type or human rights record.

This paper presents a stylized experiment with a fairly narrow scope. Situating this within the broader literature on norms and human rights presents challenges because the literature on naming and shaming has been observational, aggregated, and focused almost exclusively on the response of a government. By thinking about the individual foreign service worker or diplomat and the types of diplomatic actions they take on a daily basis, we are able to begin considering how the daily interactions and communication patterns are influenced by different appeals. The topic, the required work, and the number of steps required are important features of the intervention that we sought to control. We also sought to minimize the complexity of our request, and we expect that our findings would generalize to other similar topics, with clearly defined organizational tasks. But as the organizational complexity of the requested task increases or as the topic of the request varies across other categories, we are less certain about the generalizability of our findings. We believe however that this is an important area for future international relations research.

These findings have clear policy implications for HROs and states seeking to enforce human rights norms. In particular, our finding on the joint effect on norms and shaming highlights an important proviso for human rights advocates that there may be unintended and deleterious consequences to efforts aimed at inducing compliance if they increase the risk to individual agents. This finding can possibly explain why some HROs prefer to use soft tactics over hard pressure on states and their agents in order to change their behavior. While our explanation of this finding remains speculative, it suggests that future research should investigate the parameters under which state agents are willing and able to respect rights. In addition, the empirical evidence for the effect of international norms suggests the importance of addressing human rights issues through international law and international community pressure in improving human rights practices across states.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (109.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Annekatrin Deglow, Rob Carrol, Eric Gartzke, Nadiya Kostyuk, and Barry Hashimoto for their extremely helpful comments. We would also like to thank attendees of the 2016 Peace Science Annual Meeting and the 2017 meetings of the American Political Science Association and the Midwest Political Science Association. The Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB STUDY00004057).

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 There are 128 countries represented by 277 foreign diplomatic missions in Canada, 176 countries represented by 693 foreign diplomatic missions in the United States, and 164 countries represented by 191 foreign diplomatic missions in the United Kingdom.

2 We used two identities—Ben Adam and Dmitri Morozov. We picked male names because our past experience conducting audit studies with political elites suggests that recipients are more likely to answer emails from males than females. We used more than one name to make sure that our results were not specific to that name.

3 The randomization of sender identity was constrained so that we did not use the same identity in both wave one and wave two emails.

4 One might think about sending the follow-up emails only to missions who did not yet reply. The problem with this, however, is that it would make the reminder conditional on treatment assignment. We wanted to avoid this unnecessary complication. An objection to our approach, however, is that the reminder email might seem odd to missions who did reply. We think, however, that mission personnel would have an understanding of this given that individuals often overlook emails and that many email replies are erroneously sent to SPAM folders.

5 Since our outcome measure is bound between [0–1], we could also use logit or probit models to estimate effects. The results from these models are substantively similar to estimates from the LPM model.

6 As described above, these include the wave in which the email was sent and the valediction and separator used in the email.

7 Our results are substantively the same if we use classic standard errors or if we use HC2 robust standard errors (Angrist and Pischke Citation2008).

8 Appendix A presents these results in tabular form.

9 There are potentially many reasons for this. One might be that mission staff did not believe our emails actually came from an employee at an HRO. If this was the case, then they would have not worried about our potential power to sanction them for a non-reply. If this were true, though, we should see that the response rate for emails with the shaming cue would be much lower than the response rate for emails from the putative social studies teacher. We do not see this pattern, however. In fact, though, there is essentially no difference in these reply rates.

10 Appendix B presents these results in tabular form.

References

- Abbott, Kenneth W., Robert O. Keohane, Andrew Moravcsik, Anne-Marie Slaughter, and Duncan Snidal. (2000) The Concept of Legalization. International Organization 54(3):401–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/002081800551271.

- Angrist, Joshua D., and Jörn-Steffen Pischke. (2008) Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ausderan, Jacob. (2014) How Naming and Shaming Affects Human Rights Perceptions in the Shamed Country. Journal of Peace Research 51(1):81–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343313510014.

- Benhabib, Seyla. (2009) Claiming Rights across Borders: International Human Rights and Democratic Sovereignty. American Political Science Review 103(4):691–704. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990244.

- Betts, Alexander, and Phil Orchard. (2014) Implementation and World Politics: How International Norms Change Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brysk, Allison. (1993) From above and below Social Movements, the International System, and Human Rights in Argentina. Comparative Political Studies 26(3):259–285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414093026003001.

- Buchanan, Allen E. (2007) Justice, Legitimacy, and Self-Determination: Moral Foundations for International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bush, Sarah Sunn. (2011) International Politics and the Spread of Quotas for Women in Legislatures. International Organization 65(1):103–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818310000287.

- Costa, Mia. (2017) How Responsive are Political Elites? A Meta-Analysis of Experiments on Public Officials. Journal of Experimental Political Science 4(3):241–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2017.14.

- Creamer, Cosette D., and Beth A. Simmons. (2015) Ratification, Reporting, and Rights: Quality of Participation in the Convention against Torture. Human Rights Quarterly 37(3):579–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2015.0041.

- Dancy, Geoff, and Christopher Fariss. (2017) Rescuing Human Rights Law from International Legalism and Its Critics. Human Rights Quaterly 39(1):1–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2017.0000.

- Dietrich, Simone, and Amanda Murdie. (2017) Human Rights Shaming through INGOs and Foreign Aid Delivery. The Review of International Organizations 12(1):95–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-015-9242-8.

- Finnemore, Martha, and Kathryn Sikkink. (1998) International Norm Dynamics and Political Change. International Organization 52(4):887–917. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/002081898550789.

- Goldsmith, Jack, and Stephen D. Krasner. (2003) The Limits of Idealism. Daedalus 132(1):47–63.

- Hill, Daniel W. (2010) Estimating the Effects of Human Rights Treaties on State Behavior. The Journal of Politics 72(4):1161–1174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000599.

- Keck, Margaret, and Kathryn Sikkink. (1998) Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Krook, Mona Lena, and Jacqui True. (2012) Rethinking the Life Cycles of International Norms: The United Nations and the Global Promotion of Gender Equality. European Journal of International Relations 18(1):103–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066110380963.

- Lebovic, James H., and Erik Voeten. (2009) The Cost of Shame: International Organizations and Foreign Aid in the Punishing of Human Rights Violators. Journal of Peace Research 46(1):79–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343308098405.

- Lewis, Paul G., and S. Karthick Ramakrishnan. (2007) Police Practices in Immigrant- Destination Cities Political Control or Bureaucratic Professionalism? Urban Affairs Review 42(6):874–900. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087407300752.

- Lin, Winston, and Donald P. Green. (2016) Standard Operating Procedures: A Safety Net for Pre-Analysis Plans. PS: Political Science & Politics 49(3):495–500.

- Lipsky, Michael. (2010) Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Marrow, Helen B. (2009) Immigrant Bureaucratic Incorporation: The Dual Roles of Professional Missions and Government Policies. American Sociological Review 74(5):756–776. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400504.

- Meier, Kenneth J., and Laurence J. O’Toole. (2006) Political Control versus Bureaucratic Values: Reframing the Debate. Public Administration Review 66(2):177–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00571.x.

- Moore, Ryan T., and Keith Schnakenberg. (2012) blockTools: Blocking, Assignment, and Diagnosing Interference in Randomized Experiments. R package version 0.5-6. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/blockTools/blockTools.pdf

- Murdie, Amanda, and Dursun Peksen. (2013) The Impact of Human Rights INGO Activities on Economic Sanctions. The Review of International Organizations 8(1):33–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-012-9146-9.

- Sandholtz, Wayne. (2008) Dynamics of International Norm Change: Rules against Wartime Plunder. European Journal of International Relations 14(1):101–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066107087766.

- Wiener, Antje. (2004) Contested Compliance: Interventions on the Normative Structure of World Politics. European Journal of International Relations 10(2):189–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066104042934.

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. (2010) Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Zimmermann, Lisbeth. (2016) Same Same or Different? Norm Diffusion between Resistance, Compliance, and Localization in Post-Conflict States. International Studies Perspectives 17(1):98–115.