ABSTRACT

While it has long been acknowledged that issues play an important role in conflict processes, research on war duration has paid insufficient attention to them. In this paper, I help to remedy this deficiency by devising an original theory concerning the role of issues in war. I do this by focusing on the tangibility of the issues under dispute. I contend as the intangible salience increases, the more difficult it will be for states to bring their wars to an end. Ultimately, the more intangible salience that the issues possess, the longer wars will be. I use a mixed-methods approach. In the quantitative analysis, I employ original measures of intangible salience using data from a world-wide expert survey as well as new data on issues fought over during war. In the qualitative portion, I perform an in-depth case study on the effects of the issues on the war duration during the Vietnam War. Ultimately, I find strong support for my assertions that the issues lead states to engage in war prolongation behavior which in turn leads to longer wars.

Si bien se reconoce desde hace tiempo que las problemáticas desempeñan un papel importante en los procesos de conflicto, la investigación sobre la duración de la guerra no les ha prestado suficiente atención. En este artículo, contribuyo a subsanar esta deficiencia formulando una teoría original sobre el papel de las problemáticas en la guerra. Lo hago centrándome en la tangibilidad de las problemáticas en disputa. Sostengo que, a medida que aumente la relevancia de lo intangible, más difícil será para los Estados poner fin a sus guerras. En definitiva, cuanto más intangibles sean las problemáticas, más largas serán las guerras. Utilizo un enfoque de métodos mixtos. En el análisis cuantitativo, empleo medidas originales de relevancia intangible utilizando datos de una encuesta a expertos de todo el mundo, así como nuevos datos sobre las problemáticas que se disputan durante la guerra. En el aspecto cualitativo, llevo a cabo un exhaustivo estudio de caso sobre los efectos de las problemáticas relacionadas con la duración de la guerra en el caso de la guerra de Vietnam. Por último, compruebo fuertemente mis afirmaciones acerca de que las problemáticas llevan a los Estados a adoptar un comportamiento de prolongación de la guerra que, a su vez, conduce a guerras más largas.

Bien qu’il ait longtemps été admis que les enjeux jouaient un rôle important dans les processus de conflits, les recherches sur la durée des guerres leur ont accordé une attention insuffisante. Dans cet article, je contribue à combler cette lacune en élaborant une théorie originale concernant le rôle des enjeux dans la guerre. Pour ce faire, je me concentre sur la tangibilité des enjeux du conflit. Je soutiens que plus l’intangibilité de la saillance des enjeux augmente, plus il sera difficile pour les États de mettre un terme à leurs guerres. En fin de compte, plus la saillance des enjeux sera intangible, plus les guerres seront longues. J’ai utilisé une approche par méthodes mixtes. Dans l’analyse quantitative, j’ai employé des mesures originales de l’intangibilité de la saillance des enjeux reposant sur des données issues d’une enquête d’experts mondiaux ainsi que sur de nouvelles données sur les enjeux au nom desquels les guerres étaient menées. Dans la partie qualitative, j’ai effectué une étude de cas approfondie des effets des enjeux sur la durée de la guerre du Viêtnam. En définitive, j’ai trouvé un solide soutien à mes affirmations selon lesquelles les enjeux conduisaient les États à s’engager dans un comportement de prolongation des guerres, ce qui, à son tour, menait à des guerres plus longues.

In July 1965, the Lyndon B. Johnson administration made a series of decisions that deepened the United States’ military involvement in Vietnam. Although policy-makers thought that it would take two or more years to achieve US objectives, they did not anticipate the full costs of the decisions made that month. Despite the expenditure of billions of dollars and the loss of thousands of lives, the war ended with the United States making embarrassing concessions to a much weaker state (Logevall Citation2001). The United States’ experience in Vietnam is puzzling not because the United States fought a protracted conflict against a much weaker state or that it lost it lost the war.Footnote1 What makes this case puzzling is that even after the United States acknowledged that military victory was unlikely and the war had become extremely unpopular, it continued to fight. Even more puzzling is that the agreement that ended the war in 1973 was the same deal that North Vietnam had offered four years earlier (Berman Citation2001; Issacson Citation2005). Why did the Vietnam War last past the point that the United States knew it had very little chance of victory or of achieving any of its main objectives?

Current explanations of the war duration fail to explain the Vietnam war. The US was fully informed of its capabilities and resolve relative to Vietnam. Despite this, it refused to negotiate an end to the war or even engage in serious talks until the fighting had gone on for years (Berman Citation1991). Further, the deal the United States agreed to in 1973 did very little to ensure South Vietnam’s survival after it had left. With the United States unilaterally withdrawing from South Vietnam, the North gained a large advantage in terms of relative capabilities throwing the South’s survival into doubt (Berman Citation2001). When the United States’ behavior is compared to the broader historical record it is not an aberration. (above) shows the distribution of the duration of wars. It is one of several wars that both continue long past the point wherein both sides have reliable information about the other’s relative capabilities and resolve and that end with a negotiated settlement that does little to ensure the stability of the postwar status-quo (Langlois and Langlois Citation2009, Citation2012; Nolan Citation2017). If previous explanations cannot offer a compelling explanation in a single narrative for the duration of these wars, what can?

I argue that an examination of the issues helps explain the duration of wars generally, as well as US behavior in Vietnam specifically.Footnote2 Building upon insights from the issues approach to war, (Diehl Citation1992; Hensel and Mitchell Citation2005; Wiegand Citation2011) I devise a theory that explores the effect of issues on war duration. Issues possess both tangible and intangible value. Intangible value cannot be divided. Because intangible values cannot be shared, states will be unwilling to concede issues possessing intangible value unless they receive appropriate compensation (i.e., the value of the issue multiplied by the probability of victory). The more intangible salience the issues possess the higherthe necessary war ending payment will be. The larger the side payment needed to bring the war to an end the more unwilling or unable warring states will be to pay it. However, a state can bring down the cost of the necessary compensation by driving up the costs of the war for its opponent. This is because the costs of the side payment are a function of the intangible value of the issues multiplied by the probability of victory. This gives states an incentive to drive up their opponent’s costs and engage in the piecemeal destruction of their forces in the hopes of driving down their probability of victory and making a peace agreement possible. Ultimately, the more intangible salience the issues possess the longer wars will be. I find strong evidence for my argument through a mixed-methods approach. I first perform a large-N statistical analysis of my theory, wherein I find strong evidence that intangible salience drives war duration. I then perform an in-depth case study of the Vietnam War, in which I trace the causal process I lay out in my theory.

In this paper, I make two contributions to the study of war: I fill a gap within the study of war duration. Scholarship on war duration has paid little attention to the role of issues in driving the length of wars; my study helps to remedy this deficiency. I introduce novel data. I devise measures of divisibility and salience using data taken from a world-wide survey which I designed and administered to experts of international relations. Not only is this measure successfully applied to answering questions concerning war duration but has applications for other questions in the study of conflict processes. I also expand and update Holsti’s data on the issues wars have been fought over (Holsti Citation1991). Finally, I break down territorial issues to lower order categories to allow for variation by territory type.

When Wars End

Much of the research on war duration relies heavily upon the bargaining model of war. This model posits three causes of war: the information problem, the commitment problem, and indivisible issues. In this line of thinking, wars will end once the problem which led to the war is resolved.

An information problem leads to war when competing states cannot agree on their relative probabilities of successfully winning the war. These disagreements occur because both sides have an incentive to bluff regarding their capabilities making the information communicated unbelievable. As states fight, they obtain information leading them to a convergence regarding the likely outcome (Slantchev Citation2003a). After their expectations converge, states will end the war and distribute the issues in line with their relative probabilities of success (Goemans Citation2000; Smith and Stam Citation2004; Weisiger Citation2016). In this line of thinking, wars will vary in duration the worse the information problem. Meaning the more distance there is between the states’ ex ante estimates of the likely outcome and the true state of the world the longer it will take for the states to come to a convergence concerning their relative probabilities of success (Powell Citation2006; Ramsay Citation2008).

Critics of the information problem approach have suggested that states often fail to engage in negotiations and other behavior that will lead to a convergence of expectations. (Langlois and Langlois Citation2012) In a historical survey of war, Pillar(Citation2014) finds that states engaged in wartime negotiations in only 19 of 142 cases . A prominent example is the First World War, wherein serious negotiations did not take place until after an armistice was reached between the belligerents. Scholars have further shown that several psychological factors interfere with decision-makers’ ability to appropriately assess battlefield information and come to an accurate estimate of their relative probability of success (Dolan Citation2016).

Proponents of the commitment problem contend that it can account for the weaknesses of the information problem (Powell Citation2006). A commitment problem exists when states anticipate that a future shift in power will render void potential agreements. Wars that arise due to the commitment problem will vary in duration based upon the size of the anticipated shift in power. The larger the anticipated future shift in power the longer the war (Reiter Citation2009).

A number of studies have found that it is difficult to find historical evidence of war resolving the commitment problem. In many cases, states are content with the war ending agreements that slow but do not halt potential shifts in power (Goemans Citation2000). According to the logic of the commitment problem, this should not be the case. States seeking to resolve this problem should only be content with the war ending when the problems associated with the shift in endogenous or exogenous power are ameliorated (Reiter Citation2009; Weisiger Citation2013). If neither the information nor the commitment problem convincingly explain the duration of a considerable number of wars what does?

Research has demonstrated that a war’s duration is determined by a state’s ability and will to keep fighting rather than either the events on the battlefield or at the negotiating table (Nolan Citation2017). To this end, scholars recognize that in many cases states purposefully prolong their wars, and refuse to negotiate until one side nears exhaustion (Malkasian Citation2004). States engaging in this behavior seek to force their opponent to concede to their demands (Langlois and Langlois Citation2012). Wars end when one of the two warring states have exhausted the resources, they are willing to expend, or they can no longer impose costs on their opponents (Langlois and Langlois Citation2009; Slantchev Citation2003b). This suggests that the most pertinent information in determining the length of a war is the costs a state is willing to pay to see that the war is fought to a successful conclusion (Rosenau Citation1980). If states have very strong incentives to fight short wars, what drives them to engage in behavior that seems to purposefully prolong their wars?

I contend that the issues underlying the dispute provide the answer. Previous research has not systematically examined the role of issues in driving war duration. However, there is a large body of literature that has explored the role that the issues under dispute have on conflict processes. Previous research examining the role of issues on conflict processes has largely fallen into two camps: issue indivisibility – one of the three rationalist explanations proposed by Fearon (Citation1995), – and the issues approach to war (Mansbach and Vasquez Citation1981; Rosenau Citation1980). The issue indivisibility approach begins with the assumption that an issue is indivisible if it cannot be divided without losing much of its value (Toft Citation2006). This will lead actors to take steps to ensure that it is not divided. Studies employing this approach have shown that indivisible issues can lead to war (Hassner Citation2007; Johnson and Toft Citation2014; Toft Citation2006, Citation2003) as well as how indivisible issues can be used to strategic effect (Goddard Citation2009). Research employing the issues approach to war has explored the effect that the tangibility and salience of issues have on conflict processes. Scholars in this line of research have shown that the issues have an impact on the outbreak of interstate wars (Holsti and Holsti Citation1991; Senese and Vasquez Citation2010; Vasquez Citation1983, Citation2009), the likelihood that disputes will lead to militarized conflict (Hensel Citation1996; Hensel et al. Citation2008), as well as a large number of other phenomena (Gibler Citation2007; Owsiak and Mitchell Citation2019; Wiegand Citation2011). Although these studies have considerably enhanced our understanding of conflict, there has not yet been a study that explores the role of issues on war duration. Using insights from both approaches to issues – similar to the approach taken by Hensel et al. (Citation2005), –, I explain the role of issues on war duration.Footnote3

Issues and War Duration

I begin with the assumption that states fight wars over specific issues and will quit fighting when the disagreement over the issues has been resolved. This occurs when they come to an agreement of their relative probabilities of success. After this happens, states will distribute the issues according to these probabilities (Toft Citation2006). This is assuming the states can divide the issues. The ease with which warring states can divide the issues depends upon their nature.

An issue is defined as the subject of a conflict or controversy (Diehl Citation1992). Common issues in international relations include such things as territory, ideology, natural resources, status, and power. A large body of research has shown that conflicts and wars over issues are more or less difficult to resolve based upon their tangibility and salience (Rosenau Citation1980; Holsti Citation1991; Diehl Citation1992; Hensel Citation1996; Hensel and Mitchell Citation2005; Owsiak and Mitchell Citation2019; Zellman Citation2018; Mansbach and Vasquez Citation1981b).

The tangibility of an issue refers to the extent to which the value of the issue is specific and concrete. The less concrete the values associated with the issue the more intangible the value of the issue will be; in contrast, the more concrete the values associated with the issue, the more tangible the value of the issue. An issue can have tangible or intangible values, but few issues have only one type (Diehl Citation1992; Hensel et al. Citation2008). For example, territory possesses tangible value as it has obvious concrete economic, and in some cases strategic, worth. However, in many cases territory also possesses intangible value. States often tie their prestige and identity to the possession of certain pieces of territory (Mansbach and Vasquez Citation1981b; Senese and Vasquez Citation2010). A prominent example of an issue having both tangible and intangible value is the territory fought over during the Badme border war between Ethiopia and Eritrea (1998–2000). The territory, while having some economic and strategic value, possessed a considerable amount of intangible value. Eritrean leaders saw possession of the border region as being tied to their prestige and honor while Ethiopian leaders saw the border region as being an inseparable part of the nation’s ethnic homeland and identity (Negash and Tronvoll Citation2000).

The presence of intangible value makes disputes difficult to end. This difficulty stems from a number of factors. Chief among these is the fact that intangible values are likely to be extremely difficult if not impossible to divide without the issue losing much of its value (Mansbach and Vasquez Citation1983, 63; Toft Citation2006). In many cases, the competition over issues with high levels of intangible value often become zero-sum and all inclusive – making the issues indivisible to those that value them (Mansbach and Vasquez Citation1983). This suggests that even in cases where the parties desire to divide issues with high levels of intangible salience, it is highly unlikely that they will be able to do so (Hensel and Mitchell Citation2005).Footnote4

Because most issues in international relations possess some intangible salience, states will have difficulty working around these values to reach a negotiated peace. However, even when issues have intangible salience, a negotiated settlement can still be reached. This can be done through a compensatory payment (Pillar Citation2014). The value of this payment required to agree on the distribution of the issues is found by taking the intangible value and multiplying it by the probability of victory. The more intangible value under dispute the higher the price of the requisite payment. The higher the price of the payment, the more likely it will be that a state will be unwilling or unable to make the payment without significantly reducing the other sides probability of victory.Footnote5 This leads to the second pertinent dimension of issues: salience.

Issue salience is defined as the importance or value the issue has to the actors involved (Diehl Citation1992). An issue’s salience is determined by assessing the number of people who can possess the issue and the intensity with which they desire it (Hensel et al. Citation2008; Randle Citation1987). The more salient an issue is, the more value it will have to those that desire to possess it. This suggests two things: 1) that the more salience an issue has the higher the price both sides will be willing to pay in order to obtain it; 2) Because intangible values are usually non rival (meaning that one persons consumption does not another persons consumption) within groups, more people can possess the intangible values attached to an issue. Because more people can possess the intangible values attached to an issue, the intangible aspects of an issue will often have more salience than the tangible aspects and will subsume them in bargaining. Ultimately, the more intangible salience the issues possesses the more difficult it will be for the two sides to come to a war ending agreement over the distribution of the issues. The more intangible salience the issues have the more willingness states will be to pay the price needed to achieve victory.

Intangible Salience and How Wars are Fought

I assume that states desire to end their wars quickly and at minimal cost with the assumption being that long wars are more costly than short wars.Footnote6 The length of a war and the way a war is fought are largely determined by the issues states are competing over. When the issues have low levels of intangible salience, states will fight short intense wars that end once the two sides come to a convergence of their relative probabilities of success. This is because payment for the intangible value of the issues is possible. However, as the intangible salience increases, states will be forced to engage in strategies and behavior intended to push their opponent to a point of exhaustion and drive down their chances of victory in order to bring the costs of a war ending side-payment within reach. Ultimately, the duration of war is driven by the intangible salience of the issues and how states are subsequently forced to fight. In the section below, I will explain this line of reasoning in greater detail

The lower the intangible salience, the more easily states will be able to offer compensation for the intangible value being lost. This allows them to divide the tangible values according to their agreed-upon probabilities of success while offering payment for what cannot be divided. In such a case, states will have little incentive to drive up the costs of war and will instead engage in direct and repeated battles. This is because direct, intense battlefield confrontation, despite its limits and messiness, allows the disputants to overcome the information problem and arrive at an estimate of their relative probabilities of success.

Examples of short intense wars over issues with low intangible salience are the cabinet wars fought between various European monarchs before the Napoleonic era. In these wars, both sides usually fought over small pieces of territory with largely mercenary armies and agreed to divide the issues under dispute according to the outcome of a battle, or series of battles (Bond Citation1998; Freedman Citation2015). This is also the case for several colonial wars between western powers in the late 19th century. An example is the Spanish-American War of 1898. The war ostensibly began over the sinking of the American battleship the Maine, human rights and Cuban self-determination but was also related to American economic interests in Cuba and other Spanish colonial possessions. Overall, these issues possessed low levels of intangible salience for both sides. After a brief period of military buildup and naval battles, Spanish and American troops fought three major battles on land and two at sea in eight days (June 24, 1898-July 1, 1898), with almost constant smaller skirmishes between battles. Following a brief siege of a Spanish garrison, the Spanish agreed to a ceasefire (August 12, 1898) (Clodfelter Citation2002). In negotiations to end the war, the United States acquired Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. In exchange, it paid 20 million USD to the Spanish. Nominally, this money was paid in exchange for infrastructure projects built by Spain in their colonial possession but was, in reality, a means of the United States paying off the Spanish for the sacrifice of the intangible issues (international prestige) lost by sacrificing these colonies (Goldstein Citation2014).

As the intangible salience of the issues being disputed increases, states will be forced to engage in strategies that reduce the probabilities of victory for their opponent through the piecemeal destruction of their military (which harms their means of achieving victory) and slowly wearing down their will to fight (which affects the likelihood that they will want to go on). Ultimately, for a state seeking to drive up its opponent’s cost, time plus pressure is its best route to victory (Malkasian Citation2002, Citation2004). This is due to the fact that a short decisive victory wherein one side compels the other to drop their claim to the disputed issues is unlikely (Bond Citation1998; Nolan Citation2017) The longer a state’s opponent is forced to fight, the higher its costs will be. The higher its costs, the less ability it will have to fight in the future. The less capable a state is of continuing the fight the lower probability the state will have of winning the war. The lower the probability the state has of winning the war, the lower the price of the war ending side-payment. This is not to suggest that this approach to fighting a war is desirable. Long and prolonged wars, regardless of intensity, are extraordinarily costly. States are forced to lean heavily upon the domestic population and expend resources on the war-fighting effort that otherwise would have gone elsewhere (Malkasian Citation2002). However, as the intangible salience of the issues increases, it becomes the only means of successfully driving down the costs of the concessionary payment and bringing the war to an end.Footnote7

In summary, as the intangible salience increases, states will have more difficulty being able to afford a war-ending payment offered in exchange for the intangible value of the issues. To drive down the price of the necessary payment, they seek to impose costs on their opponent on the battlefield. From my theory, I derive the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The higher the intangible salience of the issues under dispute, the longer the war will be.

Research Design

In this section, I test Hypothesis 1 using a mixed-methods approach. First, I perform an empirical analysis using a series of duration models. I use a dataset that includes dyadic pairings of major participants in interstate wars from 1817 to 2007. The data is structured so that the unit of observation is the war day (Weisiger Citation2016). The dataset has 44,036 observations across 85 wars.Footnote8 The results of this analysis demonstrate the link between intangible salience and war duration.

However, they do not fully demonstrate the causal process I lay out in my theory. To more fully analyze the causal process; I will also perform a longitudinal case study of the Vietnam War. Tracing the causal mechanism through an in-depth case study is an ideal way of observing the causal process that would be difficult, if not impossible, to do with quantitative analysis (Goertz Citation2017).

Quantitative Analysis

Because I am testing the effect of the issues under dispute on war duration, my dependent variable is a count of the days that elapsed from the war’s onset until it ended. The longest war in the dataset lasted 3,735 days and the shortest war lasted 1 day, with the mean war lasting 767 days (Weisiger Citation2016).

My main independent variable is the intangible salience of the issues under dispute at the wars outset. To create a measure of intangible salience, I first had to identify all of the disputed issues for each war in my dataset. I started with the data from Holsti (Citation1991). Holsti identifies the issues for many of the cases included in the data. However, there are some gaps in coverage. Specifically, Holsti’s data end in 1987 and does not include non-European wars in the 19th century or some smaller wars in the 20th.Footnote9 To fill in these gaps in coverage, I first identify the definition for each issue used by Holsti. I then match these definitions against the historical records of the missing cases. For an issue to be included in the data, I have to find two sources that cite the issue as having been fought over by either of the combatants at the outset of the war.Footnote10 Holsti also uses broad categories for territorial disputes. Because different types of territorial disputes vary in their levels of intangible salience, I break these down into lower-order categories: possession of border territory, possession of colonial territory, revanchism, and territorial expansion. In , I present the frequency with which each issue has been fought over.

I then create a measure of intangible salience. To operationalize this variable, I conducted a worldwide survey of experts.Footnote11 In the survey, I ask experts to score issues according to their tangibility and salience.Footnote12 Respondents score an issue on a continuum from 0 to 100, with higher scores suggesting that more of an issue’s value was tangible.Footnote13 To find the intangible value associated with each issue, I first find the proportion of the value of the issue that is intangible by subtracting the tangibility score from 100 and then dividing it by 100. I then multiply this number by the issue’s salience score – which was found by asking respondents to assess the salience of the issues under dispute on a scale of 0 to 100 with 0 being the least salient and 100 being the most. This process gives me the intangible salience of each issue. I then match these scores to the issues in the data and find the sum of the intangible salience for each dyad war observation. I then scaled the measure by dividing the sum of the intangible salience for each dyad war observation by 100. Ultimately, this variable ranges from a minimum of 0.368 to a maximum of 2.661 and has a mean of 1.499.Footnote14 In below, I present the intangible salience scores for each of the issues.

I also control for relative capabilities using a measure of the stronger side’s share of dyadic power. The relative capabilities measure is operationalized using the Composite Index of National Capabilities scores (David, Bremer, and Stuckey Citation1972). The larger the imbalance between the disputants’ relative capabilities the shorter the war (Bennett and Stam Citation1996). I further control for the contiguity of the two states. Dyads are coded as a 1 if they share a land border and a 0 if they do not (Stinnett et al. Citation2002). Wars between two contiguous states should be shorter since they can be fought more intensely. I then control for the regime type of the challenger assigning the observation as a 1 if the polity score is greater than or equal to 7 and a 0 if the polity score is less than 7 (Marshall and Jaggers Citation2002). Scholars have found evidence that democratic challengers will fight more intense and shorter wars (Reiter and Stam Citation2002). I also control for the number of disputants participating in the war. The expected relationship is that the more states participating, the harder it will be to come to a war-ending agreement (Cunningham Citation2012). I control for the terrain upon which the war was fought. Research has shown that the rougher the terrain the longer the war will last (Slantchev Citation2004). I also control for major power dyads and major power initiators (Singer, Bremer, and Stuckey Citation1972). Further, I control for leadership turnover using data from (Weisiger Citation2016). Previous research shows that once a new leader enters into office the more likely the war is to end (Croco Citation2011). I also use the total salience score, which is operationalized using data from the expert survey described above. In , I provide the summary statistics for all of my independent variables.Footnote15

Table 1. Summary statistics for independent variables

Analysis

To assess hypothesis 1, I perform a Cox proportional hazards analysis across a series of model specifications.Footnote16 I present the findings for each of my covariates in hazard ratios. The interpretation of hazard ratios is somewhat counter-intuitive. Unlike coefficients, with hazard ratios there are no negative values to signify shorter lengths of time to failure. A Hazard ratio below one signifies that a one unit increase in the variable of interest leads to a reduction in the risk of failure. On the other hand, values higher than one signify that a one-unit increase in the variable of interest will lead to a corresponding increase in the risk of failure. Additionally, in each of my models, I employ robust standard errors. I present the results of this analysis in .

Table 2. Cox models on war duration (robust standard errors)

In model 1, I present a model that only includes intangible salience, my variable of interest. I add in a core set of control variables in model 2, and I present a fully specified model in model 3. As can be seen, the intangible salience variable behaves consistently and as expected across all three models. This suggests that my findings are not sensitive to model specification. I now turn to a more in-depth analysis of the results from Model 3, the fully specified model. In model 3, the hazard ratio is statistically significant and below 1. This suggests as the intangible salience of the issues under dispute increase, the longer the war will take to come to an end. Specifically, for every 1 unit increase in intangible salience there is a corresponding 52.4% reduction in the hazard rate of the war ending. These findings provide strong support for my theory and suggest that intangible salience makes it more difficult for states to come to a war ending agreement thus leading to longer wars.

In addition to the findings for my variable of interest, I also find that the hazard rations for terrain, strategy, and the number of states is statistically significant and below 1. This suggests that as these variables increase in value the longer a war will be. I also find that the hazard ratios for the major power dyad variable and the new leader variable are statistically significant and over 1. This means that as these variables increase in value, the shorter the war.

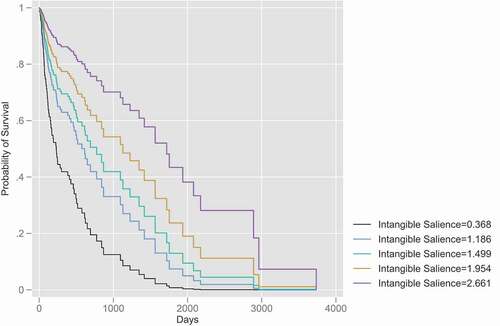

To further interpret the findings from , I provide predicted survival curves at the minimum value of intangible salience (0.368), the 25th percentile (1.186), the mean (1.499), the 75th percentile (1.954), and the maximum value (2.661) in . As can be seen, at the minimum value, the probability of wars continuing diminishes relatively rapidly. Specifically, at around 1,000 days the war has around a .15 probability of continuing and approaches 0 at around 1800 days. At the mean value (1.499) the probability of a war continuing declines at a relatively slower rate. The war has around a .40 probability of continuing past 1,000 days and around a .10 probability of going beyond 2,000 days. Further, at the maximum level of intangible salience, the probability decreases at a much slower rate. These wars have around a .70 probability of lasting longer than 1,000 days, a .40 probability of lasting longer than 2,000 days, and a .20 probability of lasting 3,000 days. As with the findings presented above, this provides strong evidence for my theory. It further suggests that as the intangible salience increases it becomes much more difficult to drive down the opponent’s probability of victory to a point wherein a side payment is possible. These findings add more support for the theory described above.

The statistical analysis provides very strong evidence for the theory I have laid out in this paper. However, the analysis is only designed to demonstrate the relationship between the intangible salience of the issues but does not fully demonstrate that the causal process laid in my theory. To do this, I will now turn to my case study of the Vietnam War.

Case Study

Of the large number of possible cases to choose from, I study the case of the Vietnam WarFootnote17 because it gives me the best means of exploring how the causal process I laid out in the theory operates (Goertz Citation2017, 56). This case is ideal because during the Vietnam War the United States and North Vietnam fought over issues that possessed high levels of intangible salience. Additionally, the war lasted for a considerable amount of time. Both of these facts suggest that I should be able to find the causal process operating in this case. Since I am only analyzing one case, I will be unable to make any cross-case claims about the validity of my argument by appeal to the qualitative portion of the analysis. However, process tracing, in combination with the quantitative analysis, further establishes the general explanatory power of my theory and the causal mechanism I specify (Collier Citation2011; Mahoney Citation2012).

If my theory can explain the case of the Vietnam War, I will be able to provide a few pieces of evidence. First, I will be able to demonstrate that the issues which North Vietnam and the United States fought over held high levels of intangible salience. Further, the nature of the issues led the disputants to conclude that a peace ending agreement was not possible at the war’s outset. Second, I will be able to show that because of the intangible salience of the issues, the states engaged in behavior that drove up the costs of the war over an extended time since alternate means did not offer a viable way of achieving success. Third, I will be able to offer evidence that as the costs of the war mounted, the states began to consider offering payments in exchange for one side sacrificing issues with high levels of intangible salience. Finally, I should be able to demonstrate that when the war was over, it ended because the states were able to make a war-ending payment in exchange for the intangible value of the issues.

The Vietnam War

The issues

North Vietnam sought ideological and national reunification. Vietnam was divided after the signing of the Geneva accords in 1954. The agreement created two countries: the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) in the north and the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) in the south (Berman Citation2001). North Vietnam was never content with this arrangement and continued to seek to reincorporate South Vietnam. For North Vietnam, ideological and national reunification were tied to its national identity and communist ideology. Policy-makers intimated in numerous public statements, that they, along with the North Vietnamese population, were willing to pay extraordinarily high costs to achieve these goals. From the mid-1950s on, North Vietnam backed up their words with actions. They provided various means of support to an increasingly successful communist insurgency in South Vietnam. North Vietnam continued down this path despite growing fears that its support for the insurgency would lead to war with the United States (Ang Citation2009; Asselin Citation2013).

Likewise, for the United States, the survival of South Vietnam was of the utmost importance. There existed a consensus in the United States that if it allowed one noncommunist state to fall to communism, then others would follow. The US commitment to Vietnam was even more important than most others. Unlike its many unspoken commitments, its military commitment to South Vietnam was laid out in the Geneva Accords. There was a belief among many that allowing South Vietnam to fall would lead to the failure of the containment policy worldwide and the damage done to US credibility and worldwide democracy would be irreparable (Logevall Citation2001). To this end, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk said, “If the communist world finds out that we will not pursue our commitments to the end, I don’t know where they will stay their hand” (Daddis Citation2011, 78).

The issues under dispute influenced policy-makers’ calculations of how the war would be fought and limited their ability to negotiate. Policy-makers in the United States anticipated that it would have to expend vast amounts of resources to ensure South Vietnam’s survival (Daddis Citation2011). The recognition of this fact led many inside and outside of the government to call on the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to find a negotiated settlement that would help them avoid war. These detractors believed that the survival of South Vietnam was not worth the blood and treasure that would be required to be successful in any war with North Vietnam. These calls fell on deaf ears. Both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations believed that any compromise would be devastating to US credibility. For many Americans, the country’s commitments to noncommunist states undergirded a deeper commitment against the existential threat of communism (Logevall Citation2001). These dearly held issues were not up for division or negotiation. When it came to Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge (the US ambassador to South Vietnam) summed up US sentiment by saying, “We cannot envisage any points that would be negotiable” (Logevall Citation2001, 68).

Ultimately neither the United States nor North Vietnam was willing or able to reach a negotiated settlement over the issues that were under dispute. This was because any agreement would require the other side to sacrifice far more than they were willing or able to.

The way they fought

Both the US and North Vietnam recognized that to achieve their objectives they would have to push the costs of the war to a point where a settlement might be possible. North Vietnam chose to dictate the tempo and the intensity of the fighting. To this end, they only engaged in direct battlefield confrontation when they were in an advantageous position interspersed with numerous raids and ambushes. This strategy allowed North Vietnam to continue to fight the war over an extended time against a much stronger power: “They Metered out their casualties when the casualties were getting too high, they just backed off and waited … They were more elusive, they were the ones that decided whether or not there would be a fight” (Van de Mark 2018, 250). The North Vietnamese military and political leaders knew that if they prolonged the war, they might not win battles, but they could win the war by driving down the United States will to continue the fight and subsequently their probability of victory. North Vietnam’s intentions were not lost on US policy-makers: Robert McNamara the US Secretary of Defense said, “I see no reasonable way to bring this war to an end soon. Hanoi has adopted a strategy of attriting our national will” (Berman Citation1991, 13). General William Westmoreland (the commander of US forces in Vietnam) echoed this sentiment in a report to his superiors, “the enemy is waging against us a conflict of strategic political attrition in which, according to this equation, victory equals time plus pressure”(Daddis Citation2011).

To defeat North Vietnam, US policy-makers came to acknowledge there was no means of victory other than imposing costs over an extended time. William Westmoreland said in 1965: “We are deluding ourselves if we feel some novel arrangement is going to get quick results. We must think in terms of extended conflict; be prepared to support a greatly increased effort” (Malkasian Citation2004). To this end, the United States sought to increase the pressure on North Vietnam, by increasing the numbers of troops and ramping up the intensity of the fighting and ultimately killing more North Vietnamese Soldiers. The United States increased the number of troops in Vietnam from 184,300 troops in 1965 to 536,100 in 1968 (Clodfelter Citation2002). The US sought to put pressure on the North Vietnamese economy and infrastructure through an aerial bombardment of industrial sites during operation rolling thunder which lasted from 1965 to 1968. By engaging in this strategy, the United States hoped it could slowly break North Vietnam’s will and destroy their means of waging war (Berman Citation1991).

Despite desires expressed by policy-makers – on both sides – throughout the dispute, to engage in alternate strategies that might bring the war to a speedier end, these strategies proved ineffective (Ang Citation2013; Berman Citation1991; Daddis Citation2011; Malkasian Citation2004). These strategies proved ineffective because no single battle could compel either side to concede – as evidenced by America’s response following the Tet Offensive in January and February of 1968 (Berman Citation1991). Alternate means of ending the war could not succeed, because they did not significantly alter either side’s probability of achieving victory enough that either side could afford a war ending side payment.

The negotiating table

The first serious effort to negotiate a settlement was in 1968. At this point, both sides perceived that the costs of the war had driven down the price of the necessary payment and that they could now reach a settlement. Chester Cooper, a US diplomat, who was intimately involved in these talks suggested, “there was nothing that we could propose until 1968 that would elicit a positive, constructive response in respect to negotiations” (Ang Citation2009, 135). Despite the optimism as the negotiations began, the two sides found that they were nowhere near an agreement. North Vietnam was not prepared to accept anything short of unilateral withdrawal of US troops from South Vietnam. Nguyen (Citation2012) and Asselin (Citation2003) suggest that claims of Richard Nixon sinking the chances of an early peace in 1968 are overblown. Hanoi was never serious about reaching a war-ending agreement. At this time, withdrawal was out of the question for the United States, who felt that its credibility was dependent upon the continued survival of South Vietnam and that there was still some probability of victory if the United States engaged in more aggressive tactics (Berman Citation2001; Issacson Citation2005)

At the negotiating table, North Vietnam found it was unable to make concessions large enough to compensate the United States for sacrificing the credibility of its commitment to South Vietnam. On the other hand, the United States could not offer anything that would come close to compensating North Vietnam depriving it of national unification. This was due to the fact Vietnam still anticipated that they had a high probability of winning the war. North Vietnam continued to make it clear that the price of conceding national unification had not been met when Le Duc Tho told Kissinger in 1970:

With over one million U.S. and Saigon troops, you have failed. Now how can you win, if you let the South Vietnamese army fight alone and if you only give them military support, how can you win? How can you win when you could not do it with 600,000 men? If our generation cannot win then our sons and nephews will continue. We will sacrifice everything, but we will not again have slavery. This is our iron will. We have been fighting for 25 years, the French and you. You wanted to quench our spirit with bombs and shells. But they cannot force us to submit (Berman Citation2001, 66).

The impasse at the negotiating table led to the continuation of the war. For the next three years, the North Vietnamese stubbornly refused to alter their demands. They insisted that the US must unilaterally withdraw its troops, the removal of the South Vietnamese president, and the immediate unification of Vietnam (Nguyen Citation2012). As time wore on and the costs mounted, the willingness of the United States to pay the costs of war was approaching its limits. At the negotiating table, the United States increasingly tried to signal that the side payment it would be will to accept to end the war was becoming lower and lower as it became increasingly clear that the United States was not likely to win the war even if it changed tactics (Issacson Citation2005).

By 1973, US policy-makers and politicians continued to look for a way out of the war while still saving face (Nguyen Citation2012). The United States was willing to accept an agreement that they found unacceptable four years early. To this end, the US agreed to end military activities in South Vietnam, unilaterally withdrawing troops in exchange for assurances from the North that it would allow President Thieu to remain in office and that South Vietnam’s ultimate fate would be determined by elections. Both sides knew that the United States’ withdrawal would lead to the reunification of Vietnam. By allowing Thieu to stay in office, North Vietnam was able to compensate the United States for unilaterally withdrawing from South Vietnam. The concession would, at most, cost the North Vietnamese a few more years without obtaining their objectives, but all sides knew that reunification was imminent. Henry Kissinger, the US Secretary of State, said of the chances of South Vietnam remaining independent, “I think if they are lucky, they can hold out for a year and a half” (Berman Citation2001). The concession, however, was enough to compensate the United States for the price of its damaged credibility, and was a way to save face.

The findings from my case study analysis, provide support for the argument I have made in this paper and help to illuminate the causal process I lay out. Specifically, the intangible salience attached to the issues under dispute precluded the possibility of a negotiation, that this led the states to engage in behavior intended to drive up the war over an extended time, and that a peace settlement was only possible when the costs of war made a war-ending payment possible.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have provided a new explanation for war duration based on the issues under dispute. Using original data, I have found strong support for my argument through a series of statistical analyses. These tests have shown that as the intangible salience of the issues increases the more difficult it will be for states to end their wars. This difficulty will lead them to take the steps required to drive down the price of a war-ending payment.

This theory and findings I lay out in this paper have important implications for the study of war. Specifically, they suggest that issues drive decisions about how wars are fought and the agreements they can accept. Since the issues drive the warfighting process to a greater extent than was previously suggested, scholars should take steps to include issues into their explanation of the warfighting process. Further, future work should explore the interactive effect between explanations based upon the distribution of power, and the issues under dispute, as power will undoubtedly have a dynamic effect on the role that issues play in the warfighting process.

Because the issues under dispute are part of a social process, they can be manipulated to strategic effect (Berman Citation2001). Future research should explore how issues are manipulated to strategic effect during war. There is a reason to suspect that leaders will employ issues to make their wars more or less difficult to resolve. Since making war more costly to resolve, is extraordinarily costly states can use this as a signal of resolve, as it can send a credible signal to their opponents that they are willing to pay the high costs of war prolongation.

My findings also have implications for third party policy-makers seeking to bring a war to an end. If one of the driving factors that drive states to prolong their wars is their inability to afford a war-ending side payment for the intangible value of the issues. To this end, third party policy-makers can help warring states afford the side payment by offering the parties financial or other forms of assistance to help them be able to pay the necessary price.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (304.1 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Notes

1 see Arreguin-Toft (Citation2001)

2 An issue is defined as the subject of a conflict or controversy (Diehl Citation1992).

3 The theory I lay out follows a similar logic and makes similar predictions as Reiter (Citation2009). Reiter’s theory, as mentioned above, is based upon the logic of the commitment problem. Some scholars such as Powell (Citation2006) contend that the problems introduced by indivisible issues are another type of commitment problem. Regardless of whether or not this is the case, an examination of the issues adds considerably to the literature. Focusing on the issues allows for an ex-ante explanation for the variation in the length of wars. It also allows for the measurement of the “increment of the good that alleviates post-war commitment problems” (Reiter Citation2009, 45). Finally, focusing on the issues under dispute picks up on far more variation in war duration than a consideration of power shifts alone (for empirical evidence see appendix I).

4 For an extensive discussion of the relationship between intangibility and indivisibility see Appendix A.

5 To this end, there may be issues that have such high levels of intangible salience that an acceptable side payment will not be possible. In such cases, I anticipate that the two sides will find until one side reaches a point of exhaustion

6 For the justification behind this assumption please see Appendix B.

7 For an extended discussion of the logic of violence underlying this assertion, please see Appendix C.

8 This does not represent the entire universe of cases. I was unable to find reliable information on the issues being disputed in several smaller wars in Central America and wars between former European states during the 19th century.

9 For a list of updated cases and sources used see Appendix D.

10 For a list of the references used to code the issues under dispute in various wars see Appendix D. Note that in each war multiple issues were fought over. Further, the issues also vary between belligerents. For example, one state can be seeking to expand its territory while another state might be engaging in the maintenance of border territory.

11 For more information about the survey see Appendix C.

12 I considered a person an expert if they had a Ph.D. in political science, were employed in academia, and specialized in international relations. The survey was sent to 1,531 experts with 123 completed surveys returned.

13 Each issue’s salience and tangibility scores were found by averaging the survey takers’ responses.

14 To see the intangible salience and total salience scores for each issue as well as histograms of total salience and intangible salience see Appendix F.

15 To see a correlation matrix of all independent variables see Appendix G.

16 Because of missingness, I do not include Weisiger’s (Citation2013) power shift variable in my main analysis. However, I do present models with this variable included in Appendix I. The results are consistent with those found in the main analysis.

17 In Appendix K, I provide a brief process-tracing analysis of the Mexican-American War.

References

- Alperovitz, Gar. 2010. The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb. New York: Vintage Books.

- Ang, Cheng G. 2009. Southeast Asia and the Vietnam War. New York: Routledge.

- Ang, Cheng G. 2013. The Vietnam War from the Other Side. New York: Routledge.

- Beevor, Anthony. 2012. The Second World War. New York: Back Bay Books.

- Arreguin-Toft, Ivan. 2001. “How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict.” International Security 26 (1): 93–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/016228801753212868

- Asselin, Pierre. 2003. A Bitter Peace: Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Asselin, Pierre. 2013. Hanoi’s Road to the Vietnam War, 1954-1965. Vol. 7. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Berman, Larry. 1991. Lyndon Johnson’s War: The Road to Stalemate in Vietnam. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Berman, Larry. 2001. No Peace, No Honor: Nixon, Kissinger, and Betrayal in Vietnam. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Bond, Brian. 1998. The Pursuit of Victory: From Napoleon to Saddam Hussein. London: Oxford University Press.

- Clodfelter, Michael. 2002. Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

- Collier, David. 2011. “Understanding Process Tracing.” PS: Political Science & Politics 44 (4): 823–30.

- Croco, Sarah E. 2011. “The Decider’s Dilemma: Leader Culpability, War Outcomes, and Domestic Punishment.” American Political Science Review 105 (3): 457–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055411000219

- Cunningham, David E. 2012. “Who Gets What in Peace Agreements.” In The Slippery Slope to Genocide: Reducing Identity Conflicts and Preventing Mass Murder, edited by Mark Anstey, Paul Meerts, and I. William Zartman, 248–69. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Daddis, Gregory A. 2011. No Sure Victory: Measuring US Army Effectiveness and Progress in the Vietnam War. London: Oxford University Press.

- Singer, J. DavidStuart Bremer, and John Stuckey. 1972. “Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 1820-1965.” Peace, War, and Numbers 19:48.

- Diehl, Paul F. 1992. “What are They Fighting For? The Importance of Issues in International Conflict Research.” Journal of Peace Research 29 (3): 333–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343392029003008

- Dolan, Thomas M. 2016. “Emotion and Strategic Learning in War.” Foreign Policy Analysis 12 (4): 571–90.

- Fearon, James D. 1995. “Rationalist Explanations for War.” International Organization 49 (3): 379–414. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300033324

- Freedman, Lawrence. 2015. Strategy: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gibler, Douglas M. 2007. “Bordering on Peace: Democracy, Territorial Issues, and Conflict.” International Studies Quarterly 51 (3): 509–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00462.x

- Goddard, Stacie E. 2009. Indivisible Territory and the Politics of Legitimacy: Jerusalem and Northern Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goemans, Hein Erich. 2000. War and Punishment: The Causes of War Termination and the First World War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Goertz, Gary. 2017. Multimethod Research, Causal Mechanisms, and Case Studies: An Integrated Approach. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Goldstein, Kalman. 2014. The Spanish-American War: A Documentary History with Commentaries. Madison, WI: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Hassner, Ron E. 2007. “The Path to Intractability: Time and the Entrenchment of Territorial Disputes.” International Security 31 (3): 107–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2007.31.3.107

- Hensel, Paul R. 1996. “Charting a Course to Conflict: Territorial Issues and Interstate Conflict, 1816-1992.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 15 (1): 43–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/073889429601500103

- Hensel, Paul R., and Sara McLaughlin Mitchell. 2005. “Issue Indivisibility and Territorial Claims.” GeoJournal 64 (4): 275–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-005-5803-3

- Hensel, Paul R., Sara McLaughlin Mitchell, Thomas E. Sowers, and Clayton L. Thyne. 2008. “Bones of Contention: Comparing Territorial, Maritime, and River Issues.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 52 (1): 117–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002707310425

- Holsti, Kalevi J. 1991. Peace and War: Armed Conflicts and International Order, 1648-1989. Vol. 14. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Issacson, Walter. 2005. Kissinger: A Biography. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Johnson, Dominic P., and Monica Duffy Toft. 2014. “Grounds for War: The Evolution of Territorial Conflict.” International Security 38 (3): 7–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00149

- Langlois, Catherine C., and Jean-Pierre P. Langlois. 2009. “Does Attrition Behavior Help Explain the Duration of Interstate Wars? A Game Theoretic and Empirical Analysis.” International Studies Quarterly 53 (4): 1051–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00568.x

- Langlois, Jean-Pierre P., and Catherine C. Langlois. 2012. “Does the Principle of Convergence Really Hold? War, Uncertainty and the Failure of Bargaining.” British Journal of Political Science 42 (3): 511–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123411000354

- Logevall, Fredrik. 2001. Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mahoney, James. 2012. “The Logic of Process Tracing Tests in the Social Sciences.” Sociological Methods & Research 41 (4): 570–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124112437709

- Malkasian, Carter. 2002. A History of Modern Wars of Attrition. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Malkasian, Carter. 2004. “Toward a Better Understanding of Attrition: The Korean and Vietnam Wars.” The Journal of Military History 68 (3): 911–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jmh.2004.0129

- Mansbach, Richard W., and John A. Vasquez. 1981. In Search of Theory: A New Paradigm for Global Politics. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Marshall, Monty G., and Keith Jaggers. (2002) ‘Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2002ʹ.

- Negash, Tekeste, and Kjetil Tronvoll. 2000. Brothers at War: Making Sense of the Eritrean-Ethiopian War. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Nguyen, Lien-Hang T. 2012. Hanoi’s War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Nolan, Cathal J. 2017. The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Owsiak, Andrew P., and Sara McLaughlin Mitchell. 2019. “Conflict Management in Land, River, and Maritime Claims.” Political Science Research and Methods 7 (1): 43–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2016.56

- Pillar, Paul R. 2014. Negotiating Peace: War Termination as a Bargaining Process. Vol. 695. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Powell, Robert. 2006. “War as a Commitment Problem.” International Organization 60 (1): 169–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818306060061

- Ramsay, Kristopher W. 2008. “Settling It on the Field: Battlefield Events and War Termination.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 52 (6): 850–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002708324593

- Randle, Robert F. 1987. Issues in the History of International Relations: The Role of Issues in the Evolution of the State System. New York: Praeger.

- Reiter, Dan. 2009. How Wars End. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Reiter, Dan, and Allan C. Stam. 2002. Democracies at War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rosenau, James N. 1980. The Scientific Study of Foreign Policy. New York. Frances Pinter.

- Bennett, D. Scott, and Allan C. Stam. 1996. “The Duration of Interstate Wars, 1816–1985.” American Political Science Review 90 (2): 239–57.

- Senese, Paul Domenic, and John A. Vasquez. 2010. Steps to War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Slantchev, Branislav L. 2003a. “The Principle of Convergence in Wartime Negotiations.” American Political Science Review 97 (4): 621–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000911

- Slantchev, Branislav L. 2003b. “The Power to Hurt: Costly Conflict with Completely Informed States.” American Political Science Review 97 (1): 123–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305540300056X

- Slantchev, Branislav L. 2004. “How Initiators End Their Wars: The Duration of Warfare and the Terms of Peace.” American Journal of Political Science 48 (4): 813–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00103.x

- Smith, Alastair, and Allan C. Stam. 2004. “Bargaining and the Nature of War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 48 (6): 783–813. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002704268026

- Stinnett, Douglas M., Paul F. Jaroslav Tir, Philip Schafer Diehl, and Charles Gochman. 2002. “The Correlates of War (Cow) Project Direct Contiguity Data, Version 3.0.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 19 (2): 59–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/073889420201900203

- Toft, Monica Duffy. 2003. The Geography of Ethnic Conflict: Identity, Interest, and the Indivisibility of Territory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Toft, Monica Duffy. 2006. “Issue Indivisibility and Time Horizons as Rationalist Explanations for War.” Security Studies 15 (1): 34–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09636410600666246

- Vasquez, John A. 1983. “The Tangibility of Issues and Global Conflict: A Test of Rosenau’s Issue Area Typology.” Journal of Peace Research 20 (2): 179–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002234338302000206

- Vasquez, John A. 2009. The War Puzzle Revisited. Vol. 110. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Weisiger, Alex. 2013. Logics of War: Sources of Limited and of Unlimited Conflicts. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Weisiger, Alex. 2016. “Learning from the Battlefield: Information, Domestic Politics, and Interstate War Duration.” International Organization 70 (2): 347–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818316000059

- Wiegand, Krista Eileen. 2011. Enduring Territorial Disputes: Strategies of Bargaining, Coercive Diplomacy, and Settlement. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Zellman, Ariel. 2018. “Uneven Ground: Nationalist Frames and the Variable Salience of Homeland.” Security Studies 27 (3): 485–510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2017.1416830