Abstract

The diversionary theory of war is one of the best-known conflict initiation theories focusing on democratic leaders’ incentives to divert public attention away from political scandals or economic policy failures. While this assumption is well-known, few studies have examined if and how the use of force could divert public attention from such a scandal or failure. By using cross-national experiments in Japan and Israel, we provide empirical tests of this particular assumption and test the other theoretically discussed implications. Our contribution is twofold. First, we confirm that, in both Japan and Israel, diverting public attention from salient political scandals may fail. Second, drawing from an experiment using a mock news article predicting the prime minister’s hawkish policy, we demonstrate that actual escalation against a potentially nuclear-armed enemy would not directly lead to greater support for the prime minister compared to the mere emphasis on the threat posed by the enemy. Simply warning of an imminent threat from North Korea or Iran is critical and sufficient to induce political support from the general public; we call it threat-induced political support.

La teoría de la guerra de distracción es una de las más conocidas sobre el inicio de los conflictos que se enfoca en los intereses de los líderes democráticos de desviar la atención pública de los escándalos políticos o las políticas económicas fallidas. Si bien este postulado es bien conocido, en pocos estudios se analizó si el uso de la fuerza podría desviar la atención del público de un escándalo o una política fallida, y de qué manera. Mediante la utilización de experimentos transnacionales en Japón e Israel, proporcionamos pruebas empíricas de este supuesto en particular y ponemos a prueba las otras implicancias debatidas en marcos teóricos. Nuestro aporte es doble. En primer lugar, confirmamos que, tanto en Japón como en Israel, desviar la atención de la opinión pública de los escándalos políticos más destacados puede fracasar. En segundo lugar, a partir de un experimento en el que se utiliza un artículo de prensa simulado que predice una política agresiva del primer ministro, demostramos que la escalada real contra un potencial enemigo armado con armas nucleares no conduce directamente a un mayor apoyo al primer ministro en comparación con el mero énfasis en la amenaza que supone el enemigo. La simple advertencia de una amenaza inminente por parte de Corea del Norte o Irán es determinante y suficiente para inducir el apoyo político del público; lo llamamos “apoyo político inducido por la amenaza.”

La théorie de la diversion de la guerre est l’une des théories les plus connues sur le déclenchement des conflits. Elle se concentre sur les motivations des dirigeants démocratiques à détourner l’attention du public des scandales politiques ou des échecs de la politique économique. Bien que cette hypothèse soit bien connue, peu d’études ont examiné si et comment le recours à la force pouvait détourner l’attention du public de tels scandales ou échecs. Nous nous appuyons sur des expériences transnationales menées au Japon et en Israël, nous proposons des analyses empiriques de cette hypothèse particulière et nous analysons les autres implications qui sont discutées d’un point de vue théorique. Notre contribution est en deux volets. D’une part, nous confirmons que, tant au Japon qu’en Israël, les tentatives de détourner l’attention du public des scandales politiques importants peuvent échouer. Et d’autre part, à partir d’une expérience reposant sur un article de presse fictif prédisant une politique belliciste du premier ministre, nous démontrons que l’escalade réelle du conflit contre un ennemi potentiellement doté de l’arme nucléaire ne conduirait pas directement à un plus grand soutien pour le premier ministre par rapport à la simple insistance sur la menace présentée par l’ennemi. Le simple fait d’avertir d’une menace imminente de la part de la Corée du Nord ou de l’Iran est essentiel et suffisant pour déclencher le soutien politique du grand public; nous qualifions cela de soutien politique induit par la menace.

Introduction

The diversionary theory of war is one of the best-known conflict initiation theories focusing on democratic leaders’ incentives. According to the theory, democratic leaders who face greater electoral challenges, either due to political scandals or an economic downturn, are more likely to choose provocative foreign policies and seek to lead the country into diplomatic crises, in hopes of inciting nationalistic sentiments that will boost their approval ratings via the so-called “rally around the flag” effect (e.g. Gaines Citation2002; Hetherington and Nelson Citation2003; Mueller Citation1973).

Despite the intuitive appeal of this theory, empirical studies have been largely unable to find consistent evidence to corroborate the purported theoretical mechanisms. Findings from observational studies have been quite mixed. The fact that a diverse set of findings have been reported from observational studies suggests that unobservable confounders arising from strategic interactions greatly hinder our ability to tease out the causal effect of electoral hardship on conflict behaviors.

In this research note, we claim that the key assumption of the theory does not work as expected. That is, a political leader cannot divert attention from his/her political scandals by emphasizing a foreign threat and alerting the general public that the country may go to war against an enemy. Although the assumptions that the threat or use of force is salient and that an acute enemy threat would create a rally-around-the-flag effect are common, they have rarely been tested at a micro-level in an experimental setting. Our team conducted a cross-national experiment to find out whether and how political leaders could divert the public’s attention away from their political scandals.

We selected Japan and Israel as fields of the experiment. Both are comparable parliamentary democracies that have witnessed a series of serious political scandals. Moreover, the general Japanese and Israeli public could plausibly expect a hawkish national security policy against the potentially nuclear-armed enemy states of North Korea and Iran, respectively, both of which are widely represented as “evil” and “mad” enemies.Footnote1 While we acknowledge that Japan and Israel have significantly different military cultures and distinct records of militarized interstate disputes, we consider them to be interesting, important, and comparable cases that could generate significant findings in testing the above-mentioned assumptions of diversionary war theory.

Our contribution is twofold. First, we confirm that, in both Japan and Israel, diverting public attention from salient political scandals would fail even if a political leader emphasizes the enemy threat or alerts the public to potential escalatory moves against the enemy. In particular, the most escalatory hawkish policy—a preemptive move—would not help the government hide its political scandals from the general public. Second, we found that, when we showed a (mock) news article predicting the prime minister’s hawkish policy (i.e. an escalation against a potentially nuclear-armed enemy), this would not directly lead to greater support for the prime minister compared to the mere emphasis on the threat level posed by the enemy. Just warning of an imminent threat from North Korea or Iran proves critical and sufficient to induce political support from the general public; we call this threat-induced political support.

Literature Review

As a theory connecting domestic politics and interstate use of force, the diversionary theory of war gathers wide scholarly attention. Consequently, there has been an accumulation of fine empirical studies, mainly examining macro-level conflict data (e.g. Haynes Citation2017; Kisangani and Pickering Citation2009, Citation2011; Oneal and Tir Citation2006; Powell Citation2014; Richards et al. Citation1993; Singh and Tir Citation2018, Citation2019; Theiler Citation2018; Tir Citation2010; Tir and Singh Citation2013).

Thanks to methodological advances in gathering public perception information, some scholars have started using microfoundation levels of data to directly observe individual perceptions during crisis situations. For instance, Theiler (Citation2018) is pioneering work to directly test popular perception change at the individual level. Using Russia’s seizure of Crimea in early 2014 as a case study, the surveys by Theiler suggest that the Crimea conflict increased national pride among Russians and support for President Vladimir Putin rose dramatically.

Furthermore, other works, such as Tir and Singh (Citation2013) and Singh and Tir (Citation2018, Citation2019) use cross-national public opinion surveys to investigate whether countries’ participation in foreign crises is connected to support for political leaders. Multiple analyses reveal that foreign crisis participation draws attention to foreign policy issues and increases support for the leaders. In particular, by using nearly 30 countries’ cross-national Comparative Study of Electoral Systems data, Tir and Singh (Citation2013) show that international crises are capable of rallying the citizenry and boosting the political leader’s support regardless of the individual’s employment status.

Recently, political scientists and social psychologists have presented experimental evidence of the rally effect. Lambert, Schott, and Scherer (Citation2011) find support for an anger-based conceptualization of the rally effect. By using a short video clip of the 9/11 attack in the USA which induces both anxiety and anger, they determined that only the latter emotion directly leads to support for the political leader as well as for the war efforts. Kobayashi and Katagiri (Citation2018) have conducted experiments in Japan and show the rally effect applies among politically liberal people. They further reveal that the improved approval ratings among liberals are completely eliminated when subjects are primed with an image of the prime minister highlighting his role as supreme commander of the Self-Defense Forces. These studies imply that a nuanced relationship exists between international crises and public support for the leader gained through the rally effect and more general diversionary mechanisms.

Although such microfoundational studies are providing new and useful evidence regarding citizens’ support of political leaders in times of crises, surprisingly few studies employ such experiments to uncover the hypothesized mechanisms at work in diversionary theories, such as the rally-around-the-flag effect. Lambert, Schott, and Scherer (Citation2011) and Kobayashi and Katagiri (Citation2018) are exceptions, and we claim that there should be more attempts at using such experiments—ours is such an attempt, as we conduct experiments in cross-nationally comparable settings.

Hypotheses

In this research note, we test the following hypotheses on the rally effect and diversionary theory. They are, in our eyes, hypotheses that could be tested in micro-level settings, but which have never been tested by experiment. We rely on previous research for the theoretical rationale of those causal connections we test, and thus the originality of this project does not reside in the theory, rather our contribution here is empirical and offers cross-countries evidence experimentally. More importantly, we will test the key assumption of the diversionary theory—whether a political leader could effectively divert the public’s attention from their scandals.

Haynes (Citation2017) conducts macro-level data analyses to test which mechanism—“rally around the flag” or “gambling for resurrection”—is most closely related to the diversionary use of force. Haynes argues that the rally and gambling theories predict diversionary conflicts that would target different types of states: diversionary wars led by a rally logic would target traditional enemies and out-groups while wars undertaken as a gamble for the resurrection would push political leaders to target powerful states to demonstrate competence to their constituents. The empirical analysis offers substantial support for the gambling for resurrection argument. Such observational studies are compelling in connecting theoretical expectations to observable phenomena, i.e., connecting independent variables, such as government unpopularity or domestic unrest to the dependent variable: militarized disputes. However, they tend to overlook the importance of directly measuring how the general public would react in an international crisis.

Drawing on Haynes’ argument, we consider both kinds of mechanisms—“rally around the flag” and “gambling for resurrection”—could be tested at a micro-level. In the former "rally" mechanism, an emphasis on the enemy and the high threat it poses is expected to garner public support for a leader via out-group/in-group psychological processes (Kobayashi and Katagiri Citation2018). The “gambling” mechanism, on the other hand, posits that a leader needs to demonstrate competence to (re)gain the public’s favor and opts to do so by initiating hawkish, escalatory policies, signaling their willingness to contain an enemy threat. To put them into testable statements, we hypothesize as follows;

Hypothesis H1a: If citizens receive information about an imminent foreign/enemy threat, their support for political leaders will increase.

Hypothesis H1b: If people receive information regarding both an imminent foreign threat and regarding the government’s hawkish national security policy against the enemy, their support for political leaders increases.

Moreover, the nature of an enemy threat may prove significant. A recent argument by McManus (Citation2021) suggests the possibility that different sources of madness may prove to be critical pieces of information given to the general public regarding enemy threats.Footnote2 At least two types of “mad” enemies exist: the first is characterized by rational but extreme preferences, while the second is characterized by irrationality and unpredictability. The former presents a certain threat insofar as the enemy is determined to attack, even at the cost of its own survival. The latter constitutes an uncertain threat as the enemy is unpredictable and cannot be deterred as predicted by rational IR theory.

We predict that diversionary mechanisms, such as “rally” attempts, would work only in a rationalist setting since an international crisis involving an irrational enemy is uncontrollable and diversionary tactics could backfire. Controlled escalation could boost the popularity of political leaders, but an uncontrollable escalation may be seen as too risky by the public, and it may not cause the desired rally effect. This leads us to further hypothesize that:

Hypothesis H1c: If citizens receive information regarding an imminent threat coming from an enemy identified as irrationally mad, political leaders’ support will not improve.

Finally, and as our key contribution to the literature, we test whether varying information treatments directly affect the people’s tolerance regarding leaders’ political scandals—a key assumption of diversionary war theory which has yet to be tested at the micro level. In theory, attention should be diverted to the crisis as citizens tend to worry more about international crises than domestic political scandals. This is a commonly shared assumption of diversionary theory, and we consider this could and should be tested by experiment. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis H2a: If citizens receive information regarding an imminent foreign threat, they will become less concerned about their leaders’ political scandals.

Hypothesis H2b: If citizens receive information regarding both an imminent foreign threat and their government’s hawkish national security policy against this enemy, they will become less concerned about their leaders’ political scandals.

Experiment Design

The comparable survey experiments were conducted in Japan and Israel, both handled by Nikkei Research (Inc.) with its collaborative partner company in Israel. Survey fielding began on January 28, 2021, and ended in Japan on February 3, 2021 and on February 10, 2021 in Israel. The English version of the scenario/questions is attached in the Appendix; the Japanese and Hebrew versions are included in the replication data package that is made available at the Harvard Dataverse. We gathered 2,907 samples in Japan and 2,852 samples in Israel.Footnote3

Japan and Israel were selected because they are both parliamentary democracies led by the center-right, conservative party and facing a potentially nuclear-armed enemy state, North Korea and Iran, respectively. Furthermore, both were experiencing salient political scandals at the time of the experiment. In Japan, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga had succeeded former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s coalition government in September 2020. The Abe government, though it had been the longest-lasting cabinet in Japanese history, had dealt with a wide variety of political scandals. In December 2020, Abe was summoned by the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office; Abe was not indicted, but the people had heard more suspicious stories about him and his former cabinet, most of which remained as the members of the succeeding Suga cabinet. Additionally, Suga himself was exposed to various political scandals in early 2021. In Israel, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who was also the country’s longest-serving prime minister, has been indicted on charges of bribery, fraud, and breach of trust, and was summoned to appear in court in early February 2021.Footnote4

In our experiment, we first asked the respondents to answer some questions regarding politics in general and international affairs (e.g., Which of the following countries are the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council? What is the most important source of information on foreign policy/international politics?), and moved on to read one of the hypothetical news scenarios that we prepared as an experiment stimulus.Footnote5

We consider that the prime minister could justify making a preemptive moveFootnote6 by manipulating North Korea and Iran as high threats, in particular, as “mad” enemies—exhibiting either rational or irrational madness.Footnote7 Providing madness information is expected to increase the people’s threat perception and might thus lead to even greater political support for a leader. We also include versions of high and low threat framing of North Korea and Iran. They are randomized to test hypotheses.

There were thus four treatments in total; [T1] preemption (i.e. military escalation) against a high threat when the enemy exhibits rational “madness,” [T2] preemption against a high enemy threat when the enemy is irrationally “mad,” [T3] no preemption information but a high enemy threat, and [Control] no preemption information but a low enemy threat.Footnote8 The baseline category is the control condition, thus a low threat scenario. However, to test for H1b, we also compare outcomes among the three treatments to see if hawkish policies [T1 and T2] achieve (or fail to achieve) a diversionary effect relative to the scenario in which leaders simply emphasize the threat [T3]. Those treatments enable us to see the differences between conditions of high/low threat and the presence/absence of escalatory moves by the democratic leader (see the actual texts of the treatments in the Appendix).Footnote9 We compare the mean scores of the dependent variables.

Our dependent variable for Hypotheses H1a through H1c was the respondents’ level of support for the prime minister. To gauge this, we asked the respondents: Do you support or do not support the Israeli (Japanese) Prime Minister? and gave them four choices (Support, Somewhat support, Somewhat not-support, and Not-support). To test Hypotheses H2a and H2b, we further posed the following question: Which statement do you agree with more?

"The Prime Minister’s political scandal is a more important agenda/issue for the country than managing Iran (North Korea),"

"The Prime Minister’s political scandal is a less important agenda/issue for the country than managing Iran (North Korea),"

"Cannot judge which is more/less important."

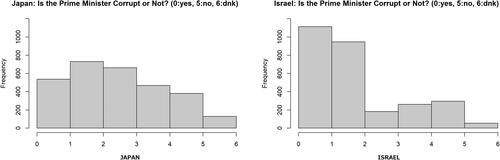

Before moving to the result section, we present which shows the descriptive statistics of the pre-treated question, included in the very first part of the survey, over respondents’ perception of the prime minister’s potential corruption. Panel A presents Japanese data and panel B the Israeli ones. The data suggest a contrast between the two countries. In Israel, a clear majority of the respondents consider the prime minister to be corrupt, but in Japan, the trend is not so clear. While many people think that the Japanese prime minister is corrupt, others disagree with that statement.

Results

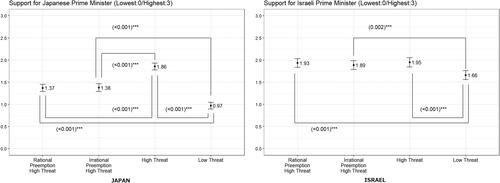

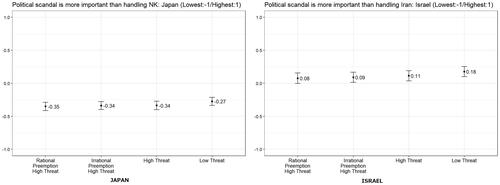

and present the main outcomes of the study. shows the mean support rate for the prime minister separated by the four treatment conditions, and reports the mean scores obtained from the question on the comparative importance of political scandals relative to international crises (i.e. handling North Korea or Iran) separated along with the four treatment conditions. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals. Significance tests were conducted by using multiple comparison methods (Tukey-Kramer).

suggests that the Japanese respondents who received information on the imminent threat of foreign enemies increased their support for political leaders compared with the case of low threat conditions. As predicted in hypothesis H1a, a higher mean support rate of 1.86 was obtained in the high threat condition, compared to a rate of 0.97 for the low threat condition; their difference is statistically significant. The more severe the threat perception is, the more people tend to support their prime minister.

Moreover, those who received information on the imminent threat of foreign enemies and the hawkish national security policy against the enemy also displayed increased support for political leaders in Japan, compared with a low threat condition. A difference between 1.37 or 1.38 for the two preemptive conditions and 0.97 for the low threat condition is also statistically significant. This suggests that support for a prime minister could rise if a person is alarmed by a higher threat from the enemy and if there is a chance of a preemptive attack against the enemy. Both hypotheses H1a and H1b are supported.

Importantly, we must note that in the Japanese case, the support level of those two conditions [T1 and T2] were (significantly) lower than the high threat only condition [T3]. This particular finding is consistent with Kertzer and Brutger’s belligerence cost argument. Kertzer and Brutger (Citation2016, 235) argue that there is a belligerence cost—“a sunk cost for threatening the use of force in the first place.” The Japanese case seems to suggest that a hawkish national security policy could reduce citizens’ support for their political leaders (relative to warning of a high foreign threat without preemptive intentions), as a result of this belligerence cost. By contrast, in the Israeli case, high threat conditions consistently led to an increased level of support for the prime minister, regardless of preemptive intentions or the enemy’s “madness” type. A support rate of 1.66 for the low threat condition is significantly different from and negatively correlated with the other three conditions.Footnote10

On the other hand, we failed to see a significant difference between the two kinds of madness in either country; hypothesis H1c is thus not supported. The “mad” nature of a threat does not matter, while the level of threat (i.e. high or low) does.

offers interesting and robust evidence that fails to support hypotheses H2a and H2b. In both Japan and Israel, respondents’ perceptions of the importance of political scandals did not change, regardless of the given treatment. As shows, there were significant differences between Japan and Israel over the level of distrust in the government leadership. When the people are more suspicious of the prime minister and his political scandals, they tend to emphasize the importance of handling the scandals rather than handling the enemy (see this difference in Panel B for Israel [above 0] in comparison to Panel A for Japan [below 0]). This means that we could not confirm the key assumption of the diversionary theory. A leader cannot divert their people’s attention from their scandals by warning them of an international crisis and implying an escalatory policy against the enemy.

This finding is important since we could not confirm a commonly-held assumption underlying diversionary theory. We realize, however, that a single mock news article may not be sufficient to divert the attention of the public away from scandals. It is possible that an accumulation of relevant information and the actual development of an acute international crisis may be necessary to induce the diversion. Nonetheless, our experiments were conducted under credible threat contexts in East Asia and the Middle East—failure of confirming the diversionary assumption under such conditions is important to note. It may not be as easy to reduce the population’s concern about political scandals as our theory expects.

Conclusion

By using Japan and Israel as distinctive but comparable fields of research for an online survey experiment, we find that warning of a high (level) enemy threat is enough to induce higher political support for a leader in the midst of a scandal. Moreover, we did not find much evidence to support the theory that people forget about political scandals when they are aware of an international crisis and are faced with a potentially nuclear-armed enemy state. Diverting people’s eyes from political scandals is tough.

The experiment lends evidence to the “rally around the flag” theory, which posits that a foreign threat is sufficient to garner greater support for political leaders. The experiment also supports the “gambling for resurrection” argument but in a more nuanced way. In the latter case, the country’s general security situation and national security culture seem to play a role in determining whether preemptive action has a positive or negative effect on leaders’ ability to garner support. However, the evidence suggests that the government should not expect the general public to be easily manipulated into forgetting a political scandal under a high threat situation. Emphasizing a growing enemy threat is sufficient to gain greater political support from the general public, what we call threat-induced political support. Nevertheless, citizens will still recall political scandals and place importance upon holding their leaders accountable.

Our originality and main contribution lay in the confirmation that these mechanisms are at work in Japan and Israel, two parliamentary democracies that have experienced serious political scandals, despite having quite different military-national security cultures. By using two very distinctive countries, we confirmed that leaders could use verbal tactics of emphasizing external threats to boost domestic support, but that would not enable them to escape their political scandals. It is similarly important to note that belligerence costs (Kertzer and Brutger Citation2016) seem to exist only in Japan, where the people rarely witness threatening gestures against the enemy. This difference in belligerence costs could be a critical variance of the people in a "pacifist" country compared to those of a “fight-aholic” country (Maoz Citation2004).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.4 KB)Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As is widely known, US President Bush and his government designated those two countries as part of the “axis of evil.” The Japanese and Israeli governments, as the official and de facto allies of the USA, share a highly similar perception of/attitude toward those two states, especially under the governments led by Shinzo Abe and Benjamin Netanyahu. See more on this framing, Choi (Citation2010) and Tankel (Citation2018, Chapter 1). Furthermore, for a comparison of Israel and Japan’s perception that Iran and North Korea are their critical enemy, respectively, see Ben-Ari and Kawano (Citation2020).

2 We must note that McManus' madman argument is about if and how leaders who are “mad” themselves, or at least those who pretend to be, can more effectively extract bargaining concessions. Since the “madness” of the North Korean and Iranian regimes is often argued and becoming a national consensus in Japan and Israel respectively, we believe that this/our study can contribute to elaborate further how others respond to “mad” leaders.

3 This experiment was conducted as part of a larger project which consisted of six treatments in total. In this particular paper, we only examined four treatments, as further explained in this section. For these four treatments, we gathered 1,952 samples in Japan and 1,902 samples in Israel.

4 Although we considered including South Korea as a candidate in Asia, we deemed it would not offer a comparable case since it was led by a left-wing political leader and is known for its conciliatory attitude toward North Korea.

5 A page before the newspaper article had presented the respondents with the following information; Now we will ask you to read a hypothetical newspaper article concerning international relations. Please answer the questions following this article. Until you finish reading the article, you cannot proceed further.

6 We assume that the people of Japan and Israel think that North Korea and Iran are with limited intelligence capability to detect preemption, and thus they believe a preemptive attack would be successful. Here, “preemption” is inserted to capture the "hawkish national security policy" initiated by the political leader.

7 As stated in the literature review section, McManus (Citation2021) is a key recent study on the “madman” theory. Here, we included two kinds of “madness” information. One madness is based on rational but extreme preferences and the other madness is based on irrationality and unpredictability.

8 We need to note that the gambling for resurrection logic of diversion (i.e. hypothesis H1b) may require more than hawkish policy information, and it must include some favorable outcome information to the crisis. However, initiating an attack implies the leader expects a favorable outcome, and their optimism for success could be sufficient for respondents to assume their leader is confident in their capacity to respond to the crisis. Having said that, though, we recognize that the favorable outcome information may be crucial in detecting the gambling for resurrection logic of diversion theory and thus note this as a task left for future studies. We deeply thank Referee 2 for their comment on this point.

9 The experimental treatments for preemption use longer texts than threat only treatments. It is reasonable to doubt that this difference (i.e. added information in preemption cases) conveys a far higher threat level than the baseline (high threat treatment) in testing H1b, H2a, and H2b. We understand this concern and thus note that further tests would be important in future follow-up studies. However, our main findings hold, even if a confounding effect exists. We deeply thank Referee 2 for pointing out this important concern.

10 Since its independence, Israel has repeatedly threatened its surrounding enemies. The belligerence cost may only exist in a relatively peaceful country like Japan, which has avoided fighting in a large-scale war since 1945. Due to the difference in perceiving belligerence costs, preemption can be a popularity generator in Israel, but not in Japan. This difference could be due to the countries’ divergent national security cultures—one is a widely known pacifist and the other is a “fight-aholic” state (Maoz Citation2004).

References

- Ben-Ari, Eyal, and Hitoshi Kawano. 2020. Military and Society in Israel and Japan: Family Support, Mental Health and Public Support: Global Security Seminar Series No. 5. Yokosuka: Center for Global Security, National Defense Academy. http://www.nda.ac.jp/cc/gs/results/series/seminarseries05.pdf

- Choi, Jinbong. 2010. “The Framing of the Axis of Evil.” Journal of Global Mass Communication 3 (1–4): 29–38.

- Gaines, Brian J. 2002. “Where’s the Rally? Approval and Trust of the President, Cabinet, Congress, and Government since September 11.” Political Science & Politics 35 (3): 531–536.

- Haynes, Kyle. 2017. “Diversionary Conflict: Demonizing Enemies or Demonstrating Competence?” Conflict Management and Peace Science 34 (4): 337–358. doi:10.1177/0738894215593723.

- Hetherington, Marc J., and Michael Nelson. 2003. “Anatomy of a Rally Effect: George W. Bush and the War on Terrorism.” Political Science and Politics 36 (01): 37–42. doi:10.1017/S1049096503001665.

- Kertzer, Joshua D., and Ryan Brutger. 2016. “Decomposing Audience Costs: Bringing the Audience Back into Audience Cost Theory.” American Journal of Political Science 60 (1): 234–249. doi:10.1111/ajps.12201.

- Kisangani, Emizet F., and Jeffrey Pickering. 2009. “The Dividends of Diversion: Mature Democracies’ Proclivity to Use Diversionary Force and the Rewards They Reap from It.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (3): 483–515. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000598.

- Kisangani, Emizet F., and Jeffrey Pickering. 2011. “Democratic Accountability and Diversionary Force: Regime Types and the Use of Benevolent and Hostile Military Force.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55 (6): 1021–1046. doi:10.1177/0022002711414375.

- Kobayashi, Tetsuro, and Azusa Katagiri. 2018. “The ‘Rally ‘Round the Flag’ Effect in Territorial Disputes: Experimental Evidence from Japan-China Relations.” Journal of East Asian Studies 18 (3): 299–319. doi:10.1017/jea.2018.21.

- Lambert, Alan J., J. P. Schott, and Laura Scherer. 2011. “Threat, Politics, and Attitudes: Toward a Greater Understanding of Rally-Round-the-Flag Effects.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 20 (6): 343–348. doi:10.1177/0963721411422060.

- Maoz, Zeev. 2004. “Pacifism and Fightaholism in International Politics: A Structural History of National and Dyadic Conflict, 1816–1992.” International Studies Review 6 (4): 107–133.

- McManus, Roseanne W. 2021. “Crazy like a Fox? Are Leaders with Reputations for Madness More Successful at International Coercion?” British Journal of Political Science 51 (1): 275–293. doi:10.1017/S0007123419000401.

- Mueller, John E. 1973. War, Presidents, and Public Opinion. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Oneal, John, and Jaroslav Tir. 2006. “Does the Diversionary Use of Force Threaten the Democratic Peace? Assessing the Effect of Economic Growth on Interstate Conflict, 1921–2001.” International Studies Quarterly 50 (4): 755–779. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00424.x.

- Powell, Jonathan M. 2014. “Regime Vulnerability and the Diversionary Threat of Force.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58 (1): 169–196. doi:10.1177/0022002712467938.

- Richards, Diana, T. Clifton Morgan, Rick K. Wilson, Valerie L. Schwebach, and Garry D. Young. 1993. “Good Times, Bad Times, and the Diversionary Use of Force: A Tale of Some Not-So-Free Agents.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 37 (3): 504–535. doi:10.1177/0022002793037003005.

- Singh, Shane P., and Jaroslav Tir. 2018. “Partisanship, Militarized International Conflict, and Electoral Support for the Incumbent.” Political Research Quarterly 71 (1): 172–183. doi:10.1177/1065912917727369.

- Singh, Shane P., and Jaroslav Tir. 2019. “The Effects of Militarized Interstate Disputes on Incumbent Voting across Genders.” Political Behavior 41 (4): 975–999. doi:10.1007/s11109-018-9479-z.

- Tankel, Stephen. 2018. With Us and Against Us: How America’s Partners Help and Hinder the War on Terror. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Theiler, Tobias. 2018. “The Microfoundations of Diversionary Conflict.” Security Studies 27 (2): 318–343. doi:10.1080/09636412.2017.1386941.

- Tir, Jaroslav. 2010. “Territorial Diversion: Diversionary Theory of War and Territorial Conflict.” The Journal of Politics 72 (2): 413–425. doi:10.1017/S0022381609990879.

- Tir, Jaroslav, and Shane P. Singh. 2013. “Is It the Economy or Foreign Policy, Stupid? The Impact of Foreign Crises on Leader Support.” Comparative Politics 46 (1): 83–101. doi:10.5129/001041513807709374.