Abstract

Do consumers discriminate against foreign products made in countries they deem adversarial? While previous studies have examined how nationalist boycotts influence trade, there is little evidence consumers “follow the flag” more generally. In this study, we employ a conjoint choice survey experiment in the United States and India to assess how individuals’ geopolitical attitudes affect their product preferences. By permitting heterogeneity in perceptions of foreign relations, and examining how these perceptions affect consumer behavior, we reveal one of the micro-level mechanisms at work in the macro-level relationship between trade and conflict. The results show that, when compared to goods made in countries perceived as “neutral” or “friendly,” consumers are 2–6% less likely to select goods made in countries they perceive as being “hostile.” We conclude that, along with organized boycotts, firms, and states, consumers are also partially responsible for the observed correlation between international political relations and trade flows.

¿Los consumidores discriminan los productos extranjeros fabricados en países que consideran adversos? Si bien estudios anteriores han examinado la forma cómo los boicots nacionalistas afectan al comercio, hay pocas pruebas de que, de un modo más general, los consumidores prefieran «lo nacional». En este estudio, empleamos un experimento de encuesta de elección conjunta realizada en los Estados Unidos y en la India para evaluar cómo las actitudes geopolíticas de los individuos afectan a sus preferencias a la hora de elegir un producto. Al permitir la heterogeneidad en las percepciones de las relaciones exteriores, y examinar cómo estas percepciones afectan al comportamiento de los consumidores, desvelamos uno de los mecanismos a nivel micro que actúan en la relación a nivel macro entre el comercio y el conflicto. Los resultados muestran que, en comparación con los productos fabricados en países percibidos como «neutrales» o «amistosos», los consumidores son entre un 2% y un 6% menos propensos a escoger productos fabricados en países que perciben como «hostiles». Concluimos que, además de los boicots organizados, las empresas y los Estados, los consumidores también son parcialmente responsables de la correlación observada entre las relaciones políticas internacionales y los flujos comerciales.

Les consommateurs sont-ils réticents à acheter des produits étrangers provenant de pays qu’ils considèrent comme antagonistes ? Si de précédents travaux ont examiné l’influence de boycotts nationalistes sur le commerce, il est plus difficile de trouver des preuves attestant d’une tendance plus générale au patriotisme de la part des consommateurs. Cet article s’appuie sur une enquête conjointe réalisée aux États-Unis et en Inde, destinée à évaluer dans quelle mesure les postures des individus en matière de géopolitique affectent leurs choix de consommation. Grâce à la pluralité des perceptions des relations internationales reflétée et à l’analyse de l’impact de ces perceptions sur les comportements des consommateurs, nous révélons l’un des mécanismes à l’oeuvre, au niveau micro, dans la relation qui s’observe au niveau macro entre commerce et conflits. Les résultats de nos recherches démontrent que les consommateurs sont 2 à 6 % moins enclins à acheter des produits provenant de pays perçus comme « hostiles » que des produits issus de pays considérés comme « neutres » ou « amis ». Nous en concluons que, tout comme les entreprises, les États et les boycotts organisés, les consommateurs sont partiellement responsables des corrélations observées entre relations politiques internationales et flux commerciaux.

Are international commercial relations influenced by political conflict? This is an important and practical question for firms and policymakers, but it’s also important for resolving a key international relations (IR) debate. Proponents of liberal theory claim and present observational evidence that trade and commerce reduce bilateral conflict (e.g. Gartzke, Li, and Boehmer Citation2001). A persistent criticism is that “trade follows the flag,” which implies that the empirical relationship between bilateral trade and peace is driven by a reverse causal process (Gowa Citation1994; Keshk, Pollins, and Reuveny Citation2004). Some split the difference by claiming that the relationship between trade and conflict flows in both directions, with mutually reinforcing effects (Pollins Citation1989; Hegre, Oneal, and Russett Citation2010). Others, still, argue that the impact of political relations on international commerce is generally overstated because internationally agreed-upon rules prevent states from restricting trade in response to conflict (Davis and Meunir Citation2011). Attempts to resolve these debates have relied heavily on aggregated bilateral trade statistics (Keshk, Pollins, and Reuveny Citation2004). However, in the absence of a convincing identification strategy (Goenner Citation2011), there is still disagreement about the direction(s) of causality.

Solutions to this problem might be found by testing the arguments’ micro-foundations. A few studies have done just that. For example, Tanaka, Tago, and Gleditsch (Citation2017) find that individuals are less likely to support belligerent acts when they are provided information about trade’s opportunity costs. In a nod to the “trade follows the flag” argument, some have focused on nationalist boycotts in response to contentious political events. Pandya and Venkatesan (Citation2016), for instance, found that, among US citizens, those most supportive of the Iraq war and most exposed to information about a boycott on French goods bought fewer supermarket items associated with France during debates about the invasion. Fouka and Voth (Citation2013) find that Greek consumers purchase fewer German goods at times of high hostility between the two countries in the aftermath of the debt crisis and that this behavior is most prominent where Germans committed war crimes in Greece during WWII. This is consistent with works showing that specific events, like the Muhammad Cartoon Crisis, can impact trade in consumer goods (Heilmann Citation2016).

These recent studies, and others like them, are insightful in demonstrating that the consumer is sometimes responsive to international relations. However, they have several limitations. First, these research designs only allow for the observation of a decline in trade, which requires meaningful trade to already exist between countries. As such, these studies might underestimate the effect of politics on trade if firms are selecting themselves out of markets where consumer perceptions of hostility could create a competitive disadvantage or where there is a high probability of a boycott. Second, by focusing only on flashpoints in bilateral political relations, they ignore how general perceptions of hostility or friendliness, independent of easily identifiable short-lived events, might influence consumer preferences for imported goods. Third, these studies also ignore heterogeneity in beliefs about the hostility or friendliness of foreign states (Kleinberg and Fordham Citation2010).

Our research design overcomes some of these limitations. We present the results of two conjoint choice experiments examining Indian and US consumer preferences for hypothetical goods (T-shirts and Televisions). We find that when goods originate in a country respondents perceive as having hostile relations with their home country, they are 2–6% less likely to prefer that good to alternatives coming from nations perceived as friendly. Our findings are unique in several ways. First, they do not suffer from identification problems as we use an established experimental method of eliciting consumer preferences over country-of-origin (Verlegh and Steenkamp Citation1999). Second, they reveal a general link between consumers’ perceptions about international politics and their preferences for imported goods—one that is independent of singular events, specific bilateral relations, or existing trade. Third, they are resilient to potential confounding by product quality, perceptions of labor conditions, and other factors.

Our study does not resolve debates over the direction of causality in the relationship between trade and conflict. However, it provides the first non-observational evidence in support of the claim that trade does indeed “follow the flag” outside of boycotts. Further, we demonstrate that, beyond state action and strategic behavior by firms (Gowa Citation1994), this is at least partially driven by consumer preferences—a feature of the argument which is often claimed (Pollins Citation1989) but lacks rigorous testing. While the effect size is small in comparison to other product attributes like price and quality, it is not trivial. Firms engaging in intra-industry trade face a great deal of competition and must make large investments when entering into or sourcing from new markets (Freund and McLaren Citation1999; Gowa and Mansfield Citation2004). Potentially, small differences in preferences can deter firms from doing commerce with specific countries.

While the primary motivation for this study is the “trade and conflict” debate in the IR literature, we also draw from, and contribute to, the marketing literature on country-of-origin (COO) effects (Bilkey and Nes Citation1982). This is a large body of work that has often emphasized COO as a “signaling” devise, informing consumers’ beliefs about product quality and style when such information is otherwise unknown (Li and Wyer Citation1994). Another notable COO effect is reflected in consumers’ commonly expressed preference for domestically produced goods over foreign imports—a general attitude termed “consumer ethnocentrism” in the literature (Shimp and Sharma Citation1987). Some researchers have taken this idea a step forward by considering how consumers’ personal attitudes toward specific foreign countries might influence their consumption choices. In a landmark study, Klein, Ettenson, and Morris (Citation1998) found that Chinese consumers’ animus toward Japan influenced their expressed willingness to purchase Japanese goods. The finding has been replicated several times since, in other contexts and under other conditions (see Riefler and Diamantopoulos Citation2007 for a review).

The “consumer animosity” research clearly parallels the present study. But our approach is distinct and offers several advantages that we believe make it a useful contribution to that literature. First, “animosity” in these studies is conceptualized and operationalized as residual anger against another country that is rooted in historical grievances and traumas (Papadopoulos, Banna, and Murphy Citation2017). We, instead, focus on consumers’ assessments of geopolitical rivalry and “hostility” in the present. The two concepts almost certainly correlate, and the distinction is perhaps a subtle one; but perceptions of contemporary relations are not the same thing as old hatreds and resentments. Second, because of the historical specificity built into the “animosity” concept, most studies in this vein focus on consumers’ attitudes toward only one or two other countries (e.g. Klein, Ettenson, and Morris Citation1998; Klein Citation2002; Nijssen and Douglas Citation2004; Ang et al. Citation2004). In contrast, our design includes upwards of ten COO candidates, and measures respondents’ foreign policy perceptions toward each. Third, we permit a spectrum of perceptions, ranging from “hostile” to “friendly.” This mirrors and (partially) satisfies a recent call in the literature to marry “consumer animosity” with its counterpart, “consumer affinity” (Oberecker, Riefler, and Diamantopoulos Citation2008; Papadopoulos, Banna, and Murphy Citation2017). Finally, the dependent variable in this research is typically measured by directly asking the respondents to report their “willingness to buy” products from country x (Klein, Ettenson, and Morris Citation1998). We opt for a conjoint choice experiment, which is a more accurate and reliable method for estimating the effects of COO (and other product attributes) on consumers’ behavior (Cui, Wajda, and Hu Citation2012).

Research Design: Consumer Behavior

We aim to show that perceptions of foreign relations influence consumer preferences, thus illustrating an important mechanism linking politics with trade flows. As noted, several other studies have explored the relationship between international politics and consumer preferences. However, our research design overcomes several limitations in previous work and is focused more broadly on the implications for the trade and conflict debate. Consider, for instance, the impact of consumer boycotts on existing trade (e.g. Pandya and Venkatesan 2016; Heilmann 2016; Luo and Zhou Citation2020). While an interesting and important subject, political relations may leave longer-lasting imprints on consumer attitudes.Footnote1 A focus on boycotts specifically misses how firms influenced by embedded political perceptions might select themselves out of foreign markets. A decline in trade is then unobservable in response to political events. As such, scholars potentially underestimate the impact of foreign relations on consumer choices.

To address these shortcomings, we administer a conjoint choice survey experiment in which we present respondents with hypothetical products from a variety of countries that vary in political and economic relations with the homeland. We ask convivence samples of Indian and U.S consumers (recruited through the Mechanical Turk platform) to indicate which product they are most likely to purchase from a set of three product profiles.Footnote2 The design requires that consumers choose between different versions of a single good type. We ask Indian respondents about their preferences for flat-screen televisions, and US respondents about preferences for a plain solid color t-shirt. We use two different goods to demonstrate that any findings are persistent across both expensive goods and cheap goods.Footnote3

While the samples are unrepresentative, they compare similarly to, if not better than, those traditionally used in marketing research, which frequently relies on student populations. Indeed, recruiting respondents in this way has been shown to provide valid inferences among US consumers (Berinsky, Huber, and Lenz Citation2012; Boas, Christenson and Glick Citation2020). The Indian sample is less representative of the population than the US sample. They are significantly more educated, less likely to come from a lower caste, have a higher income, are more likely to be male, more conservative, and more politically interested than the average Indian (Boas, Christenson, and Glick Citation2020). One notable difference is that our sample is much more Christian (13.5% vs. 2.4%) and less Muslim (6% vs 13%) than population-based surveys indicate (Sahgal et al. Citation2021). However, despite these differences, we note that the Indian “MTurkers” are more likely to represent the consumer class in India given their access to a computer, higher incomes, and English language skills. As such, they are a highly relevant sample for our purposes. The US sample, in comparison, is more educated, more male, less religious, and younger but tends to be similar in income, marital status, and race (Boas, Christenson, and Glick Citation2020).

Recent studies have observed declining quality among MTurk respondents due to efforts to overcome the platform’s geographic constraints and recommend steps to address the problem (Kennedy et al. Citation2020). We follow their recommendations by first omitting responses from IP addresses that have been identified as being associated with VPNs. We also omit the responses in the bottom 10th percentile of completion time across the five product evaluation tasks.

The three product profiles presented to respondents include several attributes. The entries for each attribute field are randomly assigned from a list of potential values. Randomization allows us to assess the causal effect of each attribute, and the interactive effects between them. That is, we can estimate the size and significance of each attribute’s impact on the probability that a respondent chooses a product relative to a baseline condition. The attribute we’re primarily concerned with is the country of origin, and how it is perceived politically in relation to the respondent’s home country. Recording this variable was a two-step process that is detailed below. The other attributes were selected because they are known to have a strong influence on consumer choice. Presenting multiple treatments also allows us to address possible confounding. For instance, since most contemporary threats to the United States come from developing countries, (perceived) hostile relations might be confounded by quality. Our design allows us to directly address this possibility by specifying the quality of the product. This is done using the standard Consumer Reports scale for the US sample, and the average customer review (as found on Amazon.in) in the India sample (1 to 5 stars). In addition, we address confounding by product price and design; and, in the case of televisions, brand, resolution, and refresh rate. Table A1 in the Supplementary Appendix presents all the possible values for each attribute.

Examples of what our US and Indian respondents encounter can be seen in and , respectively. Note that the “style” attribute is recorded by randomly assigning one of several stock images from popular retail websites. For t-shirts, this is limited to color (The gendered style is automatically triggered by the respondent’s reported gender identity). For TVs, all are images of 55” models with slight variation in frames and more notable variation in projected pictures. Company logos or other identifying characteristics are removed from the TV images; this information is instead randomly assigned in the “brand” field, with options informed by the choices available on Amazon.in. While the product image is always reported in the first line, the other attributes are ordered randomly at the respondent level. This is to minimize any bias in attribute salience that might result from list order. The overall design approximates the real-life process of shopping among products that differ along several dimensions. It is an especially good approximation of online shopping, where goods are often placed side-by-side with the relevant information attached so that the consumer can skim over it without the need to search for it on labels. We aimed to replicate this experience to the greatest extent possible.

Figure 1. Examples of Choice Task for Men and Women Shoppers in the US Sample.

Note: For respondents that identified as female, we displayed images with a different style of t-shirt.

One potential concern with our design is that some combinations of profile attributes might not be realistic. Products that are simultaneously high quality and cheap, for example; or, if the country listed in the “made in” field is different from the country commonly associated with a particular brand (e.g. Samsung of South Korea). However, such profiles are not as “impossible,” or even as unusual, as they might seem at first glance. Indeed, though certain brands might be associated with specific countries, these are multinational companies that routinely manufacture their products in many different places. Consumers are now accustomed to this reality. Also, we report perceptions of product quality via reviews. It is not uncommon to encounter high-priced products with negative reviews, nor to find lower-priced products with positive reviews. As such, we fully randomize each of the profile attributes with the expectation that, in the vast majority of cases, the options presented will seem “normal.”

Each consumer choice survey, depicted in the two figures above, represents a single task. We present the respondents with one task at a time, asking: “Which of the following products are you most likely to purchase?” Their response is recorded and is used as the dependent variable in subsequent analyses. We repeat this process five times for each respondent. We conducted additional analyses to ensure that our results are not influenced by task effects. Isolating tasks 1 and 5 produced similar results. Further, we did not see significant variance in the amount of time respondents took to complete tasks 1–5 (See Figure A5 in the Supplementary Appendix).

To gauge how individuals’ perceptions of political relations influence their purchasing preferences, we include the country of origin (i.e. the “made in” field) in the product profiles. As with the other attributes, it is randomly drawn from a list of several possible options. The list is comprised of nine large Asian countries in the US experiment, and ten large Asian countries in the Indian experiment. While India is included as an option for US respondents, it is excluded for Indian respondents. This is to eliminate the potential that the results are skewed by a well-known and strong preference for domestically produced goods (Shimp and Sharma Citation1987; Verlegh and Steenkamp Citation1999). We limited the lists to countries from a single region (Asia) to minimize confounding by any overarching regional or cultural prejudices. For example, respondents might believe goods from one region are superior in quality to those from another region. Focusing on only one region helps mitigate this risk.

Permitting the country of origin to vary is only one step in the process. Even if we find that product choice covaries reliably with COO, there would not be sufficient information to conclude that it is the country’s foreign policy relationship with the homeland that is driving the correlation. Isolating this particular factor requires tying the “made in” attribute to respondents’ underlying attitudes about who is a “friend” and who is a “foe” in world politics. We solve this problem by asking respondents: “Based on your existing knowledge, how would you rate the relations between the following countries and the United States [Indian] Government? Hostile, Neutral, or Friendly?” For the US experiment, this task was administered as part of an earlier survey; we then re-contacted these same respondents 3–5 days later to carry out the conjoint product choice tasks.Footnote4 For the Indian experiment, a two-wave survey of this type was not possible. Instead, country threat assessments were performed at the start of a single survey before the five product choice tasks. In our statistical analysis, we replace the discreet COO indicator with the respondent’s categorical assessment of the given country.Footnote5 This means that rather than identifying generic country effects (e.g. China vs. Thailand vs. the Philippines vs. etc…), we instead identify geopolitical perception effects (i.e. neutral vs. friendly vs. hostile)—a more targeted and appropriate test of the hypothesis. displays the heterogeneity in respondents’ assessments of foreign states.

Table 1. Perception of threat by country (percentage).

It’s feasible that the geopolitical concerns we’re interested in here are entangled with, and therefore confounded by, economic concerns about unfair labor practices that put the home country at a competitive disadvantage. As such, we also ask respondents to assess working conditions in each country using a similar three-category metric (i.e. poor, fair, and good). In sensitivity tests, we find that perceptions of labor rights do not confound perceptions of hostility, and our central findings stand (See Figure A3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

In sum, the conjoint choice design, coupled with our separate probe of each respondent’s geopolitical perceptions, allows us to gauge the effect of (perceived) international political relations on consumer choice. Importantly, we do so while addressing potential confounding by, and facilitating direct comparisons with, other important factors like price, quality, style, and material.

Results

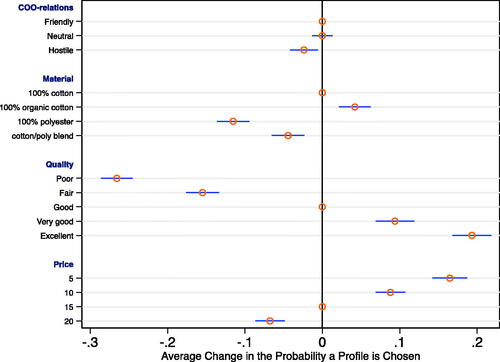

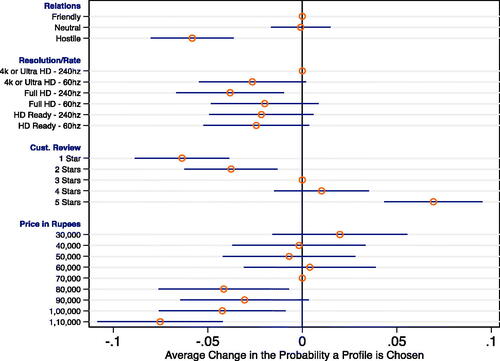

The results of the US and Indian experiments are presented in and respectively. The unit of analysis in both experiments is product profile. Recall that there are three profiles presented to the respondent for each consumer choice task, and five such tasks assigned to each respondent. This means that there are fifteen observations per respondent. The outcome choice (i.e. the profile is selected or not) is regressed on dummy variables for each attribute using a non-parametric linear probability model. This estimates the average marginal component effect (AMCE) for each attribute and can be interpreted as the difference between the probability that a product profile with the given attribute is selected versus the probability of selecting an otherwise identical product profile reporting the baseline attribute category instead (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). For example, consider the effect of price in . We can see that, relative to the baseline category of $15, a $20 price decreases the probability that a respondent chooses the t-shirt profile by 7%—a statistically significant change, as indicated by the confidence intervals (blue bars) which do not overlap with zero.Footnote6

Figure 3. Conjoint with Political Relations (US Sample—T-Shirt).

Note: The hollow circles with blue bars indicate the AMCE and their 95% confidence intervals. The hollow circles without blue bars indicate the baseline attribute. N = 15,435

Figure 4. Conjoint with Political Relations (India Sample—Television).

Note: The hollow circles with blue bars indicate the AMCE and their 95% confidence intervals. The hollow circles without blue bars indicate the baseline attribute. We exclude the brand category to improve the presentation of the results. Brand had a minimal impact on consumer choice. N = 13,485.

At the top of , we can see how perceptions of political relations between the US and a product’s country of origin affect consumer behavior. Relative to the baseline condition of perceiving “friendly” relations, respondents are 2.4% less likely to select t-shirts originating in countries perceived as “hostile” to US interests. This difference is statistically significant, as is the difference between “hostile” and “neutral” relations. However, we find no difference between the “neutral” and “friendly” categories. It appears, at least, that negative sentiments are more influential than positive sentiments (Papadopoulos, Banna, and Murphy Citation2017). Although the magnitude of the effect is small relative to the effects exerted by price, quality, and material, it is not trivial. In a competitive industry with tight margins, losing even 2–3% of potential sales is a problem. Companies that are not sensitive to this reality may find themselves disadvantaged. Importantly, those who are sensitive to it are likely strategic about where they source their finished products. As we’ve noted, such strategic behavior would affect trade flows downstream, with significant implications for macro-level observational research linking commerce and conflict.

The results of the Indian TV experiment tell a similar story.Footnote7 As indicated in , Indian respondents were 6% less likely to prefer a television if it originated in a country that they perceived as having “hostile” relations with India. The effect size is similar to the difference between a 3-star and a 1-star average customer review. Indeed, perceived political “hostility” with the source country compares more favorably overall with other product attributes than we found in the previous experiment. It’s a factor that seemed to resonate more with the Indian respondents than it did the American ones. This may be a function of relative product costs (Verlegh and Steenkamp Citation1999). Alternatively, it might reflect India’s weaker and therefore less secure position in the international system. Or, it’s possible that the results are being skewed by India’s uniquely contentious and rivalrous relationship with Pakistan (e.g. Klein, Ettenson, and Morris Citation1998). While the first two possibilities would only imply that the relationship between geopolitical perceptions and product choice is systematically conditioned by other factors, the third is more concerning because it threatens the validity and accuracy of our basic findings. We thus tested the sensitivity of our results by excluding from the analysis all product profiles that were part of a conjoint choice task in which Pakistan was included as one of the COO options. These results are presented in the Supplementary Appendix (Figure A4), and they demonstrate that, though slightly diminished in magnitude, the effect of perceived “hostility” is still substantively and statistically significant.

We took several other steps to demonstrate the robustness of the results. The estimates are stable when including individuals’ perceptions of labor conditions, indicating that concerns about unfair or unjust economic practices do not confound geopolitical perceptions. We also estimate models with the original COO entries left intact. The results do not appear to be driven by specific countries. See Figures A2 and A3 in the Supplementary Appendix. Finally, readers might be skeptical that consumers pay attention to the country of origin at all. Existing research, however, suggests that some do (Klein, Ettenson, and Morris Citation1998; Verlegh and Steenkamp Citation1999). Indeed, a majority of the respondents in our samples self-report, post-treatment, that they pay attention to the country of origin at least half the time (54%, 50%; see Supplementary Appendix Table A2).

Conclusion

Our results do not resolve debates about the direction of causality between trade and conflict. Such a task is beyond what either current observational or experimental studies can achieve. However, experimental methods, like those we’ve employed above, can provide evidence for specific mechanisms pertaining to this long-standing debate, particularly where public opinion or consumer preferences are relevant. Here, we have presented evidence that consumers do indeed “follow the flag” when considering different products and their countries of origin. This supplements micro-foundational research in IR demonstrating that information about economic interdependence can reduce support for hostile actions (Tanaka, Tago, and Gleditsch Citation2017). It also builds on research into the effectiveness of organized consumer boycotts (Pandya and Venkatesan Citation2016), revealing that everyday consumption is constrained by individuals’ perspectives on foreign relations. An important implication is that, while economically motivated preferences certainly influence trade flows, non-economic motives likely matter, too. Such motives not only inform trade policy preferences (DiGiuseppe and Kleinberg Citation2019) but perhaps even compel citizens to exert a more immediate and direct influence on trade through their purchasing preferences and behaviors.

Executing this research entailed applying some of the tools and insights from the field of marketing. And the results have implications for that literature, in turn. Indeed, our findings are broadly consistent with the “consumer animosity” hypothesis, which posits that national resentments stemming from war and exploitation have long-lasting effects on consumers’ attitudes, biasing them against the goods produced by historical antagonists (e.g. Klein, Ettenson, and Morris Citation1998; Riefler and Diamantopoulos 2007; Cui, Wajda, and Hu Citation2012). However, the “animosity” mechanism is perhaps just one aspect of a larger phenomenon. It’s not only the residual grievances from past wounds that motivate behavior; rather, consumers appear to be generally aware of the contemporary geopolitical landscape and are (at least partially) sensitive to their country’s position in relation to others.

Of course, more research will have to be done. But we have demonstrated here that developing theoretical and empirical linkages between these two traditionally distinct literatures presents a promising path forward for both.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (631.4 KB)Notes

1 See the “consumer animosity” literature, for example (Klein, Ettenson, and Morris Citation1998; Riefler and Diamantopoulos 2007).

2 See Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto Citation2014 for a more detailed explanation of the conjoint method.

3 Marketing research suggests that “country-of-origin” (COO) has the largest effect on more expensive products (Verlegh and Steenkamp Citation1999). As such, the use of a relatively cheap product in our US sample should prove a hard test for our hypothesis.

4 In the US sample, we initially contacted 2500 respondents on December 2nd 2019. The second wave, fielded on December 6th, yielded 1233 respondents. We had an attrition rate of 48%. We report in the Supplementary Appendix that the respondents that took the second wave do not differ substantively than the respondents that took the first wave. We fielded the Indian survey on December 2, 2019. Note that the surveys predate any reporting of the Covid19 pandemic.

5 This procedure is motivated by an established method. Conjoint survey experiments have been used by many scholars to examine how the attributes of a candidate impact the choice of voters or party leaders (e.g. Doherty, Dowling, and Miller Citation2019). In such studies, respondents are asked to identify a candidate they would support. Instead of explicitly including the candidates’ race and gender in the survey, they include the candidates’ names. However, when it comes time to perform the statistical analysis, names are replaced with their corresponding race and gender. We are taking a similar approach here, substituting respondents’ perceptions of different countries of origin for the actual countries themselves. This is a novel innovation, but it is not without justification.

6 Also, keep in mind that since we present each respondent with three profiles, interpretations of the substantive effects appreciate that random selection implies a 33% probability a profile is chosen, rather than the 50% probability traditionally assumed when there are two profiles.

7 We also ran a television experiment on our US sample. However, a coding error prevented the experiment from generating reliable data.

References

- Ang, Swee Hoon, Kwon Jung, Ah Keng Kau, Siew Meng Leong, Chanthika Pornpitakpan, and Soo Jiuan Tan. 2004. “Animosity towards Economic Giants: What the Little Guy Thinks.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 21 (3): 190–207. doi:10.1108/07363760410534740.

- Berinsky, Adam, Gregory A. Huber, and Gabriel S. Lenz. 2012. “Evaluating Online Labor Markets for Experimental Research.” Political Analysis 20 (3): 351–368. doi:10.1093/pan/mpr057.

- Bilkey, Warren J., and Erik Nes. 1982. “Country-of-Origin Effects on Product Evaluations.” Journal of International Business Studies 13 (1): 89–99. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490539.

- Boas, Taylor, Dino P. Christenson, and David M. Glick. 2020. “Recruiting Large Online Samples in the United States and India: Facebook, Mechanical Turk, and Qualtrics.” Political Science Research and Methods 8 (2): 232–250. doi:10.1017/psrm.2018.28.

- Cui, Annie Peng, Theresa A. Wajda, and Michael Y. Hu. 2012. “Consumer Animosity and Product Choice: Might Price Make a Difference?” Journal of Consumer Marketing 29 (7): 494–506. doi:10.1108/07363761211275009.

- Davis, Christina, and Sophie Meunir. 2011. “Business as Usual? Economic Responses to Political Tensions.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (3): 628–646. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00507.x.

- DiGiuseppe, Matthew, and Katja Kleinberg. 2019. “Economics, Security, and Individual-Level Preferences for Trade Agreements.” International Interactions 45 (2): 289–315. doi:10.1080/03050629.2019.1551007.

- Doherty, David, Conor Dowling, and Michael G. Miller. 2019. “Do Local Party Chairs Think Women and Minority Candidates Can Win? Evidence from a Conjoint Experiment.” The Journal of Politics 81 (4): 1282–1297. doi:10.1086/704698.

- Fouka, Vasiliki, and Hans-Joachim Voth. 2013. “Massacre Memories: German Car Sales and the EZ Crisis in Greece.” VOX CEPR's Policy Portal, October 23. Accessed 01 July 2021. https://voxeu.org/article/massacre-memories-german-car-salesand-ez-crisis-greece

- Freund, Caroline, and John McLaren. 1999. “On the Dynamics of Trade Diversion: Evidence from Four Trade Blocs.” International Finance Discussion Paper 1999 (637): 1–52. doi:10.17016/IFDP.1999.637.

- Gartzke, Erik, Quan Li, and Charles Boehmer. 2001. “Investing in the Peace: Economic Interdependence and International Conflict.” International Organization 55 (2): 391–438. doi:10.1162/00208180151140612.

- Goenner, Cullen F. 2011. “Simultaneity between Trade and Conflict.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 28 (5): 459–477. doi:10.1177/0738894211418414.

- Gowa, Joanne, and Edward D. Mansfield. 2004. “Allies, Imperfect Markets, and Major-Power Trade.” International Organization 58 (04): 775–805. doi:10.1017/S002081830404024X.

- Gowa, Joanne. 1994. Allies, Adversaries, and International Trade. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hainmueller, Jens, Daniel J. Hopkins, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2014. “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices via Stated Preference Experiments.” Political Analysis 22 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1093/pan/mpt024.

- Hegre, Håvard, John Oneal, and Bruce Russett. 2010. “Trade Does Promote Peace: New Simultaneous Estimation of the Reciprocal Effects of Trade and Conflict.” Journal of Peace Research 47 (6): 763–774. doi:10.1177/0022343310385995.

- Heilmann, Kilian. 2016. “Does Political Conflict Hurt Trade? Evidence from Consumer Boycotts.” Journal of International Economics 99 (2): 179–191. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.11.008.

- Kennedy, Ryan, Scott Clifford, Tyler Burleigh, Philip D. Waggoner, Ryan Jewell, and Nicholas J. G. Winter. 2020. “The Shape of and Solutions to the MTurk Quality Crisis.” Political Science Research and Methods 8 (4): 614–629. doi:10.1017/psrm.2020.6.

- Keshk, Omar M., Brian M. Pollins, and Rafael Reuveny. 2004. “Trade Still Follows the Flag: The Primacy of Politics in a Simultaneous Model of Interdependence and Armed Conflict.” The Journal of Politics 66 (4): 1155–1179. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3816.2004.00294.x.

- Klein, Jill Gabrielle, Richard Ettenson, and Marlene D. Morris. 1998. “The Animosity Model of Foreign Product Purchase: An Empirical Test in the People’s Republic of China.” Journal of Marketing 62 (1): 89–100. doi:10.1177/002224299806200108.

- Klein, Jill Gabrielle. 2002. “Us versus Them, or Us versus Everyone? Delineating Consumer Aversion to Foreign Goods.” Journal of International Business Studies 33 (2): 345–363. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8491020.

- Kleinberg, Katja, and Benjamin O. Fordham. 2010. “Trade and Foreign Policy Attitudes.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 54 (5): 687–714. doi:10.1177/0022002710364128.

- Li, Wai-Kwan, and Robert S. Wyer Jr. 1994. “The Role of Country of Origin in Product Evaluations: Informational and Standard-of-Comparison Effects.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 3 (2): 187–212. doi:10.1016/S1057-7408(08)80004-6.

- Luo, Zijun, and Yonghong Zhou. 2020. “Decomposing the Effects of Consumer Boycotts: Evidence from the anti-Japanese Demonstrations in China.” Empirical Economics 58 (6): 2615–2634. doi:10.1007/s00181-019-01650-3.

- Nijssen, Edwin J., and Susan P. Douglas. 2004. “Examining the Animosity Model in a Country with a High Level of Foreign Trade.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 21 (1): 23–38. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2003.05.001.

- Oberecker, Eva M., Petra Riefler, and Adamantios Diamantopoulos. 2008. “The Consumer Affinity Construct: Conceptualization, Qualitative Investigation, and Research Agenda.” Journal of International Marketing 16 (3): 23–56. doi:10.1509/jimk.16.3.23.

- Pandya, Sonal S., and Rajkumar Venkatesan. 2016. “French Roast: Consumer Response to International Conflict – Evidence from Supermarket Scanner Data.” Review of Economics and Statistics 98 (1): 42–56. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00526

- Papadopoulos, Nicolas, Alia El Banna, and Steven A. Murphy. 2017. “Old Country Passions: An International Examination of Country Image, Animosity, and Affinity among Ethnic Consumers.” Journal of International Marketing 25 (3): 61–82. doi:10.1509/jim.16.0077.

- Pollins, Brian M. 1989. “Does Trade Still Follow the Flag?” American Political Science Review 83 (2): 465–480. doi:10.2307/1962400.

- Riefler, Petra, and Adamantios Diamantopoulos. 2007. “Consumer Animosity: A Literature Review and a Reconsideration of Its Measurement.” International Marketing Review 24 (1): 87–119. doi:10.1108/02651330710727204.

- Sahgal, Neha, Jonathan Evans, Ariana Monique Salazar, Kelsey Jo Starr and Manolo Corichi. 2021 “Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/06/29/religion-in-india-tolerance-and-segregation/

- Shimp, Terence A., and Subhash Sharma. 1987. “Consumer Ethnocentrism: Construction and Validation of the CETSCALE.” Journal of Marketing Research 24 (3): 280–289. doi:10.1177/002224378702400304.

- Tanaka, Seiki, Atsushi Tago, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch. 2017. “Seeing the Lexus for the Olive Trees? Public Opinion, Economic Interdependence and Interstate Conflict.” International Interactions 43 (3): 375–396. doi:10.1080/03050629.2016.1200572.

- Verlegh, Peeter W. J., and Jan-Benedict E. M. Steenkamp. 1999. “A Review and Meta-Analysis of Country-of-Origin Research.” Journal of Economic Psychology 20 (5): 521–546. doi:10.1016/S0167-4870(99)00023-9.