Abstract

Previous research suggests that wartime sexual violence by rebel groups should generally be committed between rather than within ethnic groups. Since rebels can mobilize through and draw support from coethnic civilian networks, they should be less prone to commit sexual violence against their ethnic brethren. Moreover, ethnic divisions between groups are argued to spur inter-ethnic sexual violence as a strategy of war. Yet, much remains to be tested empirically. A major hindrance has been the lack of data on sexual violence that captures the ethnic identities of victims. This issue is circumvented by geocoding occurrences of sexual violence from the SVAC dataset and intersecting these with geographic patterns of ethnic settlement. Interestingly, the results show no indication of restraint in coethnic areas. They also indicate that mixed areas with both coethnic and non-coethnic civilians are more likely to experience sexual violence than entirely non-coethnic areas.

Investigaciones anteriores sugieren que la violencia sexual en tiempos de guerra por parte de grupos rebeldes generalmente debería cometerse entre grupos étnicos y no dentro de ellos. Dado que los rebeldes pueden movilizarse a través de redes civiles coétnicas y obtener el apoyo de estas, deberían ser menos propensos a cometer actos de violencia sexual contra sus hermanos étnicos. Además, se argumenta que las divisiones étnicas entre grupos estimulan la violencia sexual interétnica como estrategia de guerra. Sin embargo, aún queda mucho por comprobar empíricamente. La falta de datos sobre la violencia sexual que capten las identidades étnicas de las víctimas ha sido un obstáculo importante. Este problema se evita mediante la geocodificación de los casos de violencia sexual del conjunto de datos sobre la violencia sexual en los conflictos armados y mediante su intersección con los patrones geográficos de asentamiento étnico. Curiosamente, los resultados no muestran ningún indicio de moderación en las zonas coétnicas. También indican que las zonas mixtas con civiles coétnicos y no coétnicos tienen más probabilidades de sufrir violencia sexual que las zonas totalmente no coétnicas.

Une recherche antérieure laisse à penser que les violences sexuelles perpétrées en temps de guerre par des groupes rebelles devraient généralement être commises entre groupes ethniques plutôt qu’au sein d’un même groupe ethnique. Les rebelles, pouvant se mobiliser grâce aux réseaux civils de leur ethnie et obtenir le soutien de ces derniers, devraient être moins enclins à commettre des violences sexuelles à l’encontre de leurs frères ethniques. De plus, on estime que les divisions ethniques entre les groupes stimulent les violences sexuelles entre les ethnies en tant que stratégie militaire. Toutefois, beaucoup reste à tester empiriquement. L’absence de données sur les violences sexuelles enregistrant l’identité ethnique des victimes constituait un obstacle majeur. Le géocodage des occurrences de violence sexuelle émanant de l’ensemble des données SVAC et leur recoupage avec les modèles géographiques de peuplement ethnique ont permis de contourner ce problème. Curieusement, les résultats ne montrent aucune indication de retenue dans les zones coethniques. Ils indiquent également que les zones mixtes, peuplées à la fois de civils de la même ethnie ou non, ont davantage de probabilité de connaître des violences sexuelles que celles qui sont entièrement peuplées d’ethnies différentes.

Keywords:

Introduction

There is a wealth of literature on why rebel groups commit sexual violence against civilians in armed conflict.Footnote1 Previous works have discussed how pre-war gender inequality (Davies and True Citation2015), hyper-masculine norms and ideals (Eriksson Baaz and Stern Citation2009, Citation2013; Meger Citation2015), shifts in power balance (Johansson and Sarwari Citation2019), forced recruitment (Cohen Citation2013), non-alignment of combatant and commander preferences (Hoover Green Citation2016), and organizational constraints (Eriksson Baaz and Stern Citation2009; Meger Citation2015) affect the risk of sexual violence. Wood (Citation2018) and others have advanced the typology and moved away from rigidly viewing sexual violence as strategic or non-strategic. They propose a “policy versus practice” narrative instead and the resulting discussion has highlighted that combatant preferences interact with the commander’s stance to shape rebels’ propensity for sexual violence.

The role of ethnicity, however, remains understudied, particularly in terms of large-N empirical analysis (see Nagel Citation2019). Regardless, ethnicity is often assumed to influence sexual violence in armed conflict. Two mechanisms prevail in the literature: ethnicity as a driver of cooperation between coethnics and ethnicity as a point of contention between non-coethnics. Ethnic divisions are argued to motivate extreme violence while coethnicity incentivizes restraint. I refer to these synchronous mechanisms as the restraint and division mechanisms, respectively. Both assume the same outcome, namely that sexual violence is committed across ethnic groups rather than within. However, the reality is often more complex. First, rebel commanders may not always be able to enforce restraint. Second, ethnic heterogeneity might condition both division and restraint. Previous comparative large-N studies of ethnicity and sexual violence have been limited to the actor, country, or conflict level and relied on aggregate measures of ethnic conflict (e.g. Cohen Citation2013; Whitaker, Walsh, and Conrad Citation2019). As such, these studies have not been able to explicitly connect the ethnic identities of rebels and civilians to the propensity of sexual violence by the former against the latter. The lack of proper data has been and remains a major obstacle. The data on sexual violence that does exist cannot capture its intersectional nature, particularly not the ethnic dimension (Nagel Citation2019). The principal data source on sexual violence, the Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict (SVAC) dataset (Wieselgren Citation2022), is limited to indicating whether or not sexual violence was motivated primarily by ethnicity (Cohen and Nordås Citation2014). This means that seemingly indiscriminate sexual violence cannot be investigated for an underlying ethnic bias. Moreover, the ethnic dimension of perpetrator-victim dyads cannot be studied even when sexual violence is ethnically motivated since SVAC does not code the ethnicities of victims. Examining these aspects requires disaggregated data that captures the ethnicity of both perpetrator and victim.

In this paper, I seek to test assumptions about ethnicity and sexual violence by analyzing spatial patterns. Events of sexual violence from the SVAC dataset are geocoded and connected to data on rebel ethnic ties and ethnic group settlement from the Ethnic Power Relations data family (Vogt et al. Citation2015). Consequently, I uncover where ethnic groups that have ties to rebel actors are located, and whether the same rebel groups have committed sexual violence at that location. Areas are categorized as coethnic, mixed, or non-coethnic to account for ethnic heterogeneity. Potential issues of ecological inference are also discussed and addressed. I conduct binomial logit regression to estimate the probability of sexual violence in coethnic and mixed areas, compared to non-coethnic areas. Since the influence of rebel commanders might condition the effect of ethnic ties, I include an interaction showing that rebel groups with a weak command are more likely to commit sexual violence in mixed areas compared to in non-coethnic areas. Rebel groups with strong command are not found to discriminate between coethnic, mixed, and non-coethnic areas. This calls for further study into how to rebel governance, ethnicity, and sexual violence interact. Future research should investigate how if at all, ethnic identity affects the risk of sexual violence in rebel-controlled territories. The empirical strategy demonstrates how spatial data can advance our understanding of ethnicity and sexual violence but reveals that, ultimately, more granular data on sexual violence will be needed.

Theoretical Mechanisms

Previous research on ethnicity and wartime sexual violence has generally argued for either of two pathways, both of which assume that sexual violence is committed along ethnic lines. The restraint mechanism posits that rebel groups can benefit from intra-ethnic civilian support networks and that reliance on civilians in turn produces disincentives for committing sexual violence against them. Commanders will not tolerate sexual violence against civilians that the group relies on for fear of such violence eroding local support. Therefore, they will enforce restraint among their combatants (Muvumba Sellström Citation2015; Wood Citation2006, Citation2009). For example, rebels that rely on smuggling rather than extortion are argued less likely to commit sexual violence since they rely on civilian cooperation to a greater extent (Whitaker, Walsh, and Conrad Citation2019). This logic of restraint is extended to rebel coethnics (Wood Citation2018, 14) since rebel actors can draw on ethnic networks to enhance their capability for armed struggle (Lilja and Hultman Citation2011). Ethnic networks lower the transaction costs of a rebellion (Sambanis Citation2001) and coethnic constituents can be relied upon for the acquisition of recruits, intelligence, and funds (Cederman et al. Citation2020; Eck Citation2009; Fjelde and Hultman Citation2014; Ottmann Citation2017). Since coethnic civilians can constitute a strong source of support, rebels are assumed less likely to commit sexual violence against coethnics than against other civilians.

The division mechanism posits that ethnic grievances can motivate the use of extreme violence. It departs from the understanding of sexual violence as a weapon of war, a perspective that gained momentum following events such as the mass rapes in Bosnia in 1992 (see Benard Citation1994). Ethnic grievance in the context of armed conflict is argued to lead to a sense of existential threat, which in turn motivates the use of extreme violence in response (Fearon Citation2008; Horowitz Citation1985). Rape and sexual violence are particularly rife in these conflicts (Meger Citation2016), likely because sexual violence can be an effective method of asserting ethnic dominance over the enemy (Doja Citation2019). Rape and degradation of the enemy ethnic group’s women and men demonstrate victory over the group and assert dominance over their ethnic identity; rape of the person symbolizes rape of the community (Alison Citation2007). Evidence of this mechanism can be found in Kosovo, where sexual violence was used to forcefully remove the enemy population (Di Lellio and Kraja Citation2021), and Iraq, where ISIS used sexual slavery to humiliate and dominate non-Muslim communities (Ahram Citation2019). Accordingly, the division mechanism also expects that sexual violence will be more likely across ethnic groups than within.

Based on these mechanisms, rebel groups should limit sexual violence against coethnic civilians but might commit sexual violence as a weapon of war against ethnic enemies. Hence, hypothesis 1 expects that:

H1: Rebel actors are less likely to commit sexual violence in coethnic areas than in non-coethnic areas.

However, the first hypothesis assumes that commanders are capable of enforcing restraint. While commanders may strive to enforce restraint, their ability to do so will be conditional on the influence they have over their combatants. If prohibition is too costly in terms of status or resources, commanders may have to tolerate sexual violence, even against coethnics (Wood Citation2018). This is the case for rebel groups that rely on forced recruitment and suffer from poor social cohesion as a result. Cohen (Citation2013) argues that sexual violence, particularly gang rape, can increase trust and strengthen bonds within these groups. Weak commanders might decide that the benefits of tolerating such practices, even among rebels’ coethnics, outweigh the costs. In general, rebel groups where commanders exert a strong influence over their combatants should be expected to conform to commander rather than combatant preferences. Having a strong command structure should therefore lead to a more effective prohibition of violence against coethnics, given the benefits of restraint. Hence, hypothesis 2a expects that:

H2a: Rebel actors with a strong command are less likely to commit sexual violence in coethnic areas compared to rebel actors with a weak command.

The ethnic composition of the civilian population should also condition the assumed mechanisms. Traditional theory on ethnic grievance posits that ethnic heterogeneity increases the overall risk of armed conflict (see Sambanis Citation2001). Greater heterogeneity is argued to exacerbate the fear of ethnic rivals that motivates extreme violence. Sexual violence against non-coethnics should then be more likely in heterogeneous populations, where coethnics and non-coethnics live in close proximity. From a practical standpoint, strategic violence such as ethnic cleansing should also disproportionately affect non-coethnics that live near coethnics. As for the restraint mechanism, it should be weaker in heterogeneous populations. Meger (Citation2016) discusses the use of sexual violence to enforce submission and deter collaboration with the enemy. In heterogeneous populations, there might be a greater need to forcibly exert control over coethnics than there are inhomogeneous populations. This follows the reasoning of Asal and Nagel (Citation2021), who find that ethnically mobilized rebel groups are less likely to commit sexual violence the longer they have held territory. They theorize that territories homogenize over time and that incentives for committing sexual violence are gradually outweighed by the risk of eroding local support during this process. Ethnically heterogeneous areas should therefore be at greater risk than others. Hence, hypothesis 2b expects that:

H2b: Rebel actors are more likely to commit sexual violence in mixed areas than in coethnic or non-coethnic areas.

Research Design

To test the restraint and division mechanisms at an actor-target level, I rely on spatial patterns of sexual violence and rebels’ coethnic populations.Footnote2 The data is structured around first-order administrative divisions or units (i.e. states, provinces, regions) as gathered from the Database of Global Administrative Areas (GADM) version 3.6, corresponding to the administrative divisions as of 2020. While GADM is public and easily accessed, it unfortunately does not provide a historical version of the data. Structuring the data around admin units serves to provide variation across space and is the first building block of the unit of analysis. First-order admin units constitute the optimal compromise in the trade-off between accuracy and data availability. A lower level of disaggregation (e.g. counties) would increase accuracy at the cost of data since reports of sexual violence are often difficult to situate beyond the regional level. To attain variation across rebel groups, the next building block of the unit of analysis, each admin unit appears once for each rebel group that is active in the country. Some groups are active across multiple countries (such as the Lord’s Resistance Army), while others are only active in a particular region of their origin country. Rebel groups like the LRA that have been active across multiple countries (such as the Lord’s Resistance Army) are only tied to the country/countries with which they have a state-based incompatibility (in this case Uganda). While this is a simplification of rebel activity, it lends itself well to the SVAC data. SVAC only reports locations of sexual violence that lie within the respective countries with which the rebels have incompatibilities. The authors do not comment on this, but it is likely a consequence of the source material for SVAC being country reports. In short, all admin units of a country appear once for each rebel group that has an incompatibility in the country. Admin units of countries in which multiple rebel groups have an incompatibility appear multiple times.Footnote3 The final building block is time, where a calendar year is the most fine-grained unit for both data on ethnic settlement and sexual violence. The scope is limited to Africa from 1989 to 2009, due to constraints in the data on sexual violence.Footnote4 The unit of analysis is rebel group—admin unit—year and the number of observations is 18,303 rebel-admin-years. The data consists of 449 unique admin units in twenty-seven countries and 116 rebel groups across 21 years.

To measure sexual violence across rebel actor, time, and space, I rely on the Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict (SVAC) dataset version 1.1 (Cohen and Nordås Citation2014). SVAC has an actor-year structure with three ordinal prevalence measures of sexual violence. I integrate these measures into a single dichotomous measure. I geocode the prevalence of sexual violence by using the string variable “location” in SVAC 1.1 which lists keywords of the location/s at which sexual violence was reported for the actor-year.Footnote5 The level of detail in this string variable varies greatly between observations, with keywords ranging from “in the bush” to “suburb of Monrovia.” Where rebel groups are reported to have committed sexual violence in multiple locations in a year, the locations are listed after each other. Each discernible location is geocoded to an admin unit and year using map tools and consulting the country reports from which they were originally coded by the SVAC coders. Now, there are limitations to using SVAC to geocode sexual violence. For example, the coding of the location variable was not rigorously standardized across SVAC coders. The authors also highlight the inconsistency in detail between observations, explaining that it stems from the original source material being varyingly specific from report to report. To check the sensitivity of the results to the coding procedure, I drop all rebel years that report locations of sexual violence that could not be geocoded as a robustness test. This eliminates potential systematic bias by excluding rebel groups that appear as non-perpetrators simply because the sexual violence they have committed cannot be geocoded.

To measure ethnic ties between rebels and civilian populations, I rely on data from the Ethnic Power Relations data family (Vogt et al. Citation2015). I use the GeoEPR dataset to calculate the overlap of politically relevant ethnic groups’ settlement patterns and admin units. If the overlap of an ethnic group polygon and an admin unit is equal to or higher than twenty percent of the total size of the admin unit, the admin unit is coded as being inhabited by the ethnic group.Footnote6 The ethnic groups inhabiting an admin unit are then checked for ties to rebel groups active in the country. Data on rebel groups’ ties to ethnic groups are gathered from the ACD2EPR dataset of the EPR family. If a rebel group has made an exclusive claim to fight for an ethnic group or there is widespread support among members of an ethnic group for the rebels, that admin unit is coded as being inhabited by coethnics to the rebel group. For admin units that are inhabited by coethnics, a distinction is made between those that are solely inhabited by coethnics and those that house multiple politically relevant ethnic groups. The resulting independent variable is a categorical variable with the responses “coethnic,” “mixed,” and “non-coethnic.” Unfortunately, the Geo-EPR data only covers politically relevant ethnic groups. This means that there may well be additional ethnic groups in the admin units that are coded as coethnic, just not groups that are politically represented. For a more detailed description of the procedure for geocoding sexual violence and ethnic ties, please see Supplementary Appendix B.

These measures of ethnic ties and sexual violence introduce some issues of ecological inference. Ideally, one would not have to rely on geographical patterns to examine individual-level phenomena, or at the very least be able to use a lower-level administrative unit. But since the data on sexual violence cannot be disaggregated further without losing a significant amount of data, I have to be content with taking other steps. The alternative thresholds for coethnic and mixed areas, dropping unclear prevalence years as well as other robustness tests introduced later reduce the risk of ecological fallacy. But even with these, there are limits to what this study can achieve given the data it relies on. The aim cannot be to provide strong empirical evidence on which a new theory can be built. Instead, this paper strives to broadly outline patterns of ethnicity and sexual violence in armed conflict, and in doing so test prevailing assumptions, outline avenues for future research and stress the need for more disaggregated data. To this end the design is appropriate.

To measure the reinforcing effect of command strength, I rely on the Non-State Actor (NSA) dataset by Cunningham, Gleditsch, and Salehyan (Citation2013). From it, I draw a dichotomous measure of command strength based on the three-point ordinal central command strength variable, with a threshold between “high” and “moderate.” The original three-point ordinal scale is used in the robustness tests. NSA data only includes active conflict years, so the last reported value is imputed to post-conflict years to reduce missing data. Considering that the NSA data is time-invariant, aside from when rebel groups undergo a transformation, this is not expected to affect the main findings. Additionally, I include two variables on ethnic dynamics, using data from the EPR data family (Vogt et al. Citation2015). One controls whether the rebel group is ethnically mobilized and the other for the number of politically relevant ethnic groups in the admin unit. I also include a logged measure of the population from the World Development Indicators (World Bank Citation2021), since a larger population increases the general risk of conflict (Fearon and Laitin Citation2003). I control for the natural log of rebel battle-related deaths and one-sided violence, using data from the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset version 19.1 (Sundberg and Melander Citation2013). Battle-related deaths reflect rebel activity. Intense fighting can motivate rebels to resort to alternative strategies, such as sexual violence (e.g. Johansson and Sarwari Citation2019), and rebels are likely to be most active near their ethnic constituents. One-sided violence controls for path dependence in coercive behavior toward civilians; rebels who have abused civilians in the past may be more likely to continue to do so (Weinstein Citation2006). To control for path dependence in sexual violence specifically, I include the dependent variable lagged by one year.

Results

Based on the restraint and division mechanisms, the results are expected to show a lower prevalence of rebel sexual violence in coethnic areas compared to non-coethnic areas. Accounting for ethnic heterogeneity, a higher prevalence of sexual violence in mixed areas than in non-coethnic areas is also expected. shows that the distribution of both ethnic ties and sexual violence is quite skewed. Less than 3% of all observations in the data are coethnic and about twenty percent are mixed. Sexual violence is also rare, with only about half a percent of all observations taking a value of one. The overlap of ethnic ties and sexual violence is visually presented in . The highlighted admin units reflect which admin units have experienced sexual violence by rebels. The shades represent the ties that the perpetrator had to the admin unit. Admin units that are striped have experienced sexual violence by multiple groups that have different ties to the area. Western Sahara is not included in the GADM data.

Table 1. Distribution of ethnic ties and sexual violence.

The results from binomial logit regressions are presented in , where models 1 and 2 are estimated using the full set. For both model specifications, coethnic and mixed ties are positively associated with sexual violence, meaning that rebel groups are found more likely to perpetrate sexual violence in such areas than in areas without coethnics. Furthermore, model 2 shows that rebels with a strong command are more likely to commit sexual violence in general, but that the interaction of mixed ties and a strong command is negative. The magnitude is estimated just slightly greater than the positive coefficient of command strength’s main effect, meaning that they largely cancel each other out. These initial findings show no support for H1 or H2a, given that areas, where rebels have coethnics, are suggested more likely to experience sexual violence than areas where they do not. Rebel command strength does not seem to make a significant difference, perhaps not entirely surprising given the aggregate nature of the variable. The findings do indicate support for H2b, however, suggesting that mixed areas are more likely to experience sexual violence than non-coethnic areas. Additionally, all controls behave as expected apart from the population measure. Typically, larger populations on the country level are associated with a higher risk of conflict. Given that these findings are based on aggregate spatial measures of ethnicity and sexual violence, I rerun the first model specification on three subsets where the hypothesized outcomes should be most likely.Footnote7 In the subset Conflict zone, only active conflict areas are included, i.e. admin units where there has been at least one conflict-related fatality in the current year. Intense conflict areas should be more likely to see other forms of violence, including sexual violence. In the subset Ethnic mobilization, only rebel groups that have ties to an ethnic group are included. This limits the analysis to contexts where ethnicity is politicized and a relevant factor. In the subset History of SV, only rebel groups that have previously committed sexual violence are included. Groups that do not commit sexual violence may refrain from it for any number of reasons, so this subset limits the analysis to groups where non-prevalence is a clearer sign of restraint. These results are also presented in . The results are consistent with the findings from the full set.

Table 2. Ethnic ties and sexual violence by rebels.

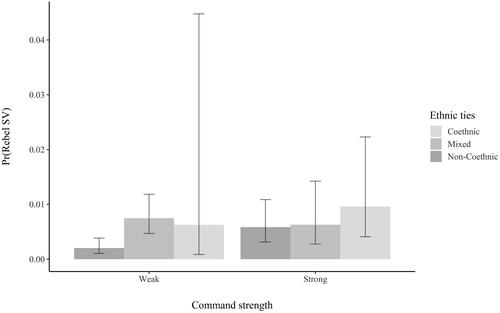

To further probe the findings, I estimate predicted probabilities of sexual violence at different values of Ethnic ties and Command strength using the second model specification on the full set. shows the probability of sexual violence in coethnic, mixed, and non-coethnic units, respectively. The categories of rebel command strength are shown on the horizontal axis. All controls are set at their mean, except ethnic mobilization which is set at its median value of one. The error bars signify the upper and lower bounds of a ninety-five percent confidence interval. The figure shows that for rebels with a weak command, the risk of sexual violence is considerably higher in coethnic and mixed areas compared to in non-coethnic areas. The difference is significant for mixed areas, while the confidence interval is extremely wide for coethnic areas, due to the limited variation on the ethnic ties variable. For rebels with a strong command, the risk of sexual violence in coethnic areas is slightly higher than for the other categories, but the difference is well within the bounds of the confidence interval. Importantly, the expected probability of sexual violence is very low, between one and two percent, across all categories of ethnic ties and command strength. This is partially a result of the data structure, where each rebel group is assumed equally likely to do commit sexual violence across all admin units in their country. However, the effect is exceptionally low, calling into question the relevance of ethnicity as a predictor of sexual violence. Though weak rebel groups are found more likely to commit sexual violence in mixed areas than in non-coethnic areas, ethnic ties may not be substantively meaningful for the broad patterns of sexual violence.

I run some robustness tests using both model specifications from . First, I use a subset in which no locations reported in SVAC were lost as a result of the geocoding. Dropping these observations reduces the sample size to 13,961 and 10,566 for the respective models. I also try an alternative procedure for coding ethnic ties. First, I swap the support indicator from ACD2EPR for an indicator on rebel recruitment from ethnic groups. Next, I use alternative thresholds of overlap for an ethnic group to be considered present in an admin unit. In addition to the twenty percent threshold, I set the threshold at five, fifty, and ninety-five percent overlap. I add time and country fixed effects to control for temporal and spatial interdependence. Finally, I swap the dichotomized command strength variable for its original three-point ordinal version, with a medium set as the reference category. The main findings of models 1 and 2 in are robust in all tests.Footnote8

Conclusion

This paper has sought to test the prevailing assumption that rebels generally commit sexual violence along ethnic lines, and in doing so it has produced two main insights. First, the results indicate that to the extent that ethnicity matters, rebels do not exercise restraint in coethnic areas. Second, the low substantive effect of ethnic ties provides cause for questioning the importance of ethnicity as a predictor of sexual violence.

The lack of evidence for a restraint mechanism in coethnic areas is interesting and quite puzzling. Asal and Nagel (Citation2021) find that ethnically mobilized rebels are less likely to commit sexual violence than other groups and that this effect becomes stronger the longer they hold territory. The results here do not indicate such a pattern. But Asal and Nagel (Citation2021) also argue that the forms of sexual violence vary based on territorial control. When rebels establish control over territory, they commit sexual violence for the purpose of coercion and cleansing. Once control is achieved, they violently maintain it through sexual violence; seeking control over territory through control over bodies. This explanatory model is compatible with the results of this paper, where occurrences of coethnic sexual violence could be committed by rebels seeking to maintain control. It might also explain why mixed areas are associated with a high risk of sexual violence, since these may be areas where rebels seek to establish control. Unfortunately, SVAC is not granular enough to discern the prevalence of individual forms of sexual violence spatially. Qualitative research on sexual violence in territories of notorious perpetrators such as UNITA or Boko Haram might shed more light on how ethnicity overlaps with territorial control.

On the substantive effect, it is important to state that the relevance of ethnicity in specific cases of violence is not disputed. Ethnic divisions were at the center in cases like Srebrenica in Bosnia and the genocide of Yazidis by the Islamic State. But the findings suggest that other dynamics are far more important in shaping the overall patterns of sexual violence. Mixed areas being found more likely to experience sexual violence is likely, at least in part, driven by other factors than ethnicity. Ethnic heterogeneity per se should not be the cause, since there was no effect on the number of ethnic groups in an admin unit. It is possible that ethnic divisions are exacerbated and acted upon to a greater extent in heterogeneous populations, as per H2b. It is also possible that rebels perceive a greater need to assert dominance and control in heterogeneous areas, as mentioned previously. But likely, the reason is mainly practical; sexual violence is more likely where rebels are active because rebels that mobilize through ethnic networks are active where there are ethnic divisions.

Lastly, future research might investigate how different forms of violence against civilians affect each other. The association between one-sided and sexual violence in this paper lends some support to the idea that abusive rebel-civilian relations perpetuate (Weinstein Citation2006). In pursuit of these questions, future researchers would make a huge contribution by collecting individual-level or granular spatial data on sexual violence that accounts for social identifiers. While this empirical strategy has shown that spatial data can help to make sense of how ethnicity affects sexual violence, further research will ultimately demand better data.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (124.3 KB)Acknowledgments

I owe thanks to Karin Johansson, Maxine Leis, and Angela Muvumba Sellström as well as three anonymous reviewers for their excellent feedback and comments on earlier versions of this paper. I am also immensely thankful to Lisa Hultman for giving me advice and guidance throughout the process.

Data Availability Statement

The geocoded SVAC data used for this study is openly available in Mendeley Data, at: http://doi.org/10.17632/fyyp694myt.1.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This paper is limited to sexual violence committed by rebel actors due to the scope of the restraint mechanism.

2 Aggregating individual-level phenomena to geographic areas introduces issues of measurement reliability. I mitigate these issues through alternative specifications of what constitutes a coethnic area in the robustness tests.

3 As the entire time-period is set prior to the independence of South Sudan, the collective admin units of Sudan and South Sudan are treated as one country. Instances of sexual violence in Sudan are therefore geocoded using all admin units of modern-day Sudan and South Sudan and rebel groups are expanded across all these units. The same procedure was employed for Eritrea, where all modern-day admin units of Eritrea were treated as part of Ethiopia 1989–1993, the year of independence. The independence of Namibia from South Africa in 1990 is unproblematic as neither country appears as a location in SVAC.

4 The proportion of sexual violence observations that could be geocoded is higher in Africa compared to all other continents.

5 Neither SVAC 2.1 nor Geo-SVAC can be used for the geocoding. The former dropped the location variable from the update and the latter offers geolocation of conflict events involving actors that use sexual violence, not actual events of sexual violence.

6 The main findings are also robust to alternative thresholds, see the robustness tests.

7 Model 1 is chosen in lieu of model 2 to increase model performance. There is not enough variation within the coethnic category of ethnic ties to include the interaction term with a reduced sample size. Even in the full set, there is just one event of sexual violence in a coethnic area by a rebel group with a weak command.

8 See Supplementary Appendix A for the full results of the robustness tests.

References

- Ahram, A. I. 2019. “Sexual Violence, Competitive State Building, and Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 13 (2): 180–196. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1541577.

- Alison, M. 2007. “Wartime Sexual Violence: Women’s Human Rights and Questions of Masculinity.” Review of International Studies 33 (1): 75–90. doi:10.1017/S0260210507007310.

- Asal, V., and R. U. Nagel. 2021. “Control over Bodies and Territories: Insurgent Territorial Control and Sexual Violence.” Security Studies 30 (1): 136–158. doi:10.1080/09636412.2021.1885726.

- Benard, C. 1994. “Rape as Terror: The Case of Bosnia.” Terrorism and Political Violence 6 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1080/09546559408427242.

- Cederman, L.-E., S. Hug, L. I. Schubiger, and F. Villamil. 2020. “Civilian Victimization and Ethnic Civil War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (7–8): 1199–1225. doi:10.1177/0022002719898873.

- Cohen, D. K. 2013. “Explaining Rape during Civil War: Cross-National Evidence (1980–2009).” American Political Science Review 107 (3): 461–477. doi:10.1017/S0003055413000221.

- Cohen, D. K., and R. Nordås. 2014. “Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict: Introducing the SVAC Dataset, 1989–2009.” Journal of Peace Research 51 (3): 418–428. doi:10.1177/0022343314523028.

- Cunningham, D. E., K. S. Gleditsch, and I. Salehyan. 2013. “Non-State Actors in Civil Wars: A New Dataset.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 30 (5): 516–531. doi:10.1177/0738894213499673.

- Davies, S. E., and J. True. 2015. “Reframing Conflict-Related Sexual and Gender-Based Violence: Bringing Gender Analysis Back in.” Security Dialogue 46 (6): 495–512. doi:10.1177/0967010615601389.

- Di Lellio, A., and G. Kraja. 2021. “Sexual Violence in the Kosovo Conflict: A Lesson for Myanmar and Other Ethnic Cleansing Campaigns.” International Politics 58 (2): 148–167. doi:10.1057/s41311-020-00246-4.

- Doja, A. 2019. “Politics of Mass Rapes in Ethnic Conflict: A Morphodynamics of Raw Madness and Cooked Evil.” Crime, Law and Social Change 71 (5): 541–580. doi:10.1007/s10611-018-9800-0.

- Eck, K. 2009. “From Armed Conflict to War: Ethnic Mobilization and Conflict Intensification.” International Studies Quarterly 53 (2): 369–388. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00538.x.

- Eriksson Baaz, M., and M. Stern. 2009. “Why Do Soldiers Rape? Masculinity, Violence, and Sexuality in the Armed Forces in the Congo (DRC).” International Studies Quarterly 53 (2): 495–518. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00543.x.

- Eriksson Baaz, M., and M. Stern. 2013. Sexual Violence as a Weapon of War? Perceptions, Prescriptions, Problems in the Congo and Beyond. London: Zed Books.

- Fearon, J. D. 2008. “Ethnic Mobilization and Ethnic Violence.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Economy, edited by B. Weingast and D. Wittman, 852–868. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fearon, J. D., and D. D. Laitin. 2003. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War.” American Political Science Review 97 (1): 75–90. doi:10.1017/S0003055403000534.

- Fjelde, H., and L. Hultman. 2014. “Weakening the Enemy: A Disaggregated Study of Violence against Civilians in Africa.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58 (7): 1230–1257. doi:10.1177/0022002713492648.

- Hoover Green, A. 2016. “The Commander’s Dilemma: Creating and Controlling Armed Group Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 53 (5): 619–632. doi:10.1177/0022343316653645.

- Horowitz, D. L. 1985. Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Johansson, K., and M. Sarwari. 2019. “Sexual Violence and Biased Military Interventions in Civil Conflict.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 36 (5): 469–493. doi:10.1177/0738894216689814.

- Lilja, J., and L. Hultman. 2011. “Intraethnic Dominance and Control: Violence against Co-Ethnics in the Early Sri Lankan Civil War.” Security Studies 20 (2): 171–197. doi:10.1080/09636412.2011.572676.

- Meger, S. 2015. “Toward a Feminist Political Economy of Wartime Sexual Violence: The Case of the Democratic Republic of Congo.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 17 (3): 416–434. doi:10.1080/14616742.2014.941253.

- Meger, S. 2016. Rape Loot Pillage: The Political Economy of Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Muvumba Sellström, A. 2015. “Stronger than Justice Armed Group Impunity for Sexual Violence.” PhD thesis, Uppsala University.

- Nagel, R. U. 2019. The Known Knowns and Known Unknowns in Data on Women, Peace and Security. LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security Working Paper. Accessed October 30, 2020. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/104048/

- Ottmann, M. 2017. “Rebel Constituencies and Rebel Violence against Civilians in Civil Conflicts.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 34 (1): 27–51. doi:10.1177/0738894215570428.

- Sambanis, N. 2001. “Do Ethnic and Nonethnic Civil Wars Have the Same Causes?” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 45 (3): 259–282. doi:10.1177/0022002701045003001.

- Sundberg, R., and E. Melander. 2013. “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 50 (4): 523–532. doi:10.1177/0022343313484347.

- Vogt, M., N.-C. Bormann, S. Rüegger, L.-E. Cederman, P. Hunziker, and L. Girardin. 2015. “Integrating Data on Ethnicity, Geography, and Conflict: The Ethnic Power Relations Data Set Family.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (7): 1327–1342. doi:10.1177/0022002715591215.

- Weinstein, J. M. 2006. Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Whitaker, B. E., J. I. Walsh, and J. Conrad. 2019. “Natural Resource Exploitation and Sexual Violence by Rebel Groups.” The Journal of Politics 81 (2): 702–706. doi:10.1086/701637.

- Wieselgren, H. 2022. “SVAC Geocoded.” Mendeley Data, V1. Accessed September 1, 2022. http://doi.org/10.17632/fyyp694myt.1

- Wood, E. J. 2006. “Variation in Sexual Violence during War.” Politics & Society 34 (3): 307–342. doi:10.1177/0032329206290426.

- Wood, E. J. 2009. “Armed Groups and Sexual Violence: When is Wartime Rape Rare?” Politics & Society 37 (1): 131–161. doi:10.1177/0032329208329755.

- Wood, E. J. 2018. “Rape as a Practice of War: Toward a Typology of Political Violence.” Politics & Society 46 (4): 513–537. doi:10.1177/0032329218773710.

- World Bank. 2021. World Development Indicators. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators