Abstract

Cyber operations as a facet of international competition pose a direct challenge to alliances. Designed to respond to conventional military attacks, alliances like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization must now determine whether their defensive commitments extend into cyberspace. This question is not limited to political and military elites, as the use of force in defense of allies is among the most politically charged decisions a state can make and relies significantly on public support. This article extends recent public opinion literature on cyber conflict to investigate public attitudes towards existing treaty commitments following a destructive cyber operation against an allied state. Using a survey experiment involving United States nationals, we find that while participants are sensitive to treaty obligations, these effects are moderated by individual factors like domain expertise. Furthermore, we observe that specific aggressor-ally dyads tied to geographic regions can shape public preferences, with participants being more reactive to Europe-based scenarios than comparable treatments in Asia.

Las operaciones cibernéticas, como una faceta de la competencia internacional, plantean un desafío directo a las alianzas. Aunque fueron diseñadas para responder a ataques militares convencionales, alianzas como la Organización del Tratado del Atlántico Norte deben determinar ahora cómo se traducen sus compromisos defensivos en el ámbito digital. Esta cuestión no está limitada a las élites políticas y militares, ya que el uso de la fuerza para la defensa de los aliados es una de las decisiones con mayor carga política que puede tomar un Estado y depende en gran medida del apoyo público. Este artículo amplía la literatura reciente, en materia de opinión pública, sobre conflictos cibernéticos con el fin de investigar las actitudes públicas hacia los compromisos de los tratados existentes después de una operación cibernética destructiva contra un Estado aliado. Descubrimos, mediante el uso de un experimento de encuesta en el que participaron ciudadanos estadounidenses, que, si bien los participantes son sensibles a las obligaciones de los tratados, estos efectos están moderados por factores individuales como la experiencia en el dominio. Además, observamos que las díadas específicas agresor-aliado que están vinculadas a regiones geográficas pueden dar forma a las preferencias del público, y que los participantes son más reactivos a los escenarios que tienen lugar en Europa que a aquellos comparables en Asia.

Les cyberopérations, facettes de la concurrence internationale, présentent un défi direct pour les alliances. Conçues pour répondre aux attaques militaires conventionnelles, les alliances comme l’Organisation du Traité de l’Atlantique Nord doivent aujourd’hui déterminer comment leurs engagements défensifs se traduisent dans le domaine numérique. Cette question ne se limite pas aux élites politique et militaire, car l’usage de la force pour défendre des alliés compte parmi les décisions les plus polémiques qu’un État peut prendre. Or, elles reposent en grande partie sur le soutien public. Cet article s’inscrit dans le prolongement de la littérature récente sur l’opinion publique en matière de cyberconflits. Il s’intéresse à l’attitude de la population à l’égard des engagements existants par traité à la suite d’une cyberopération destructrice à l’encontre d’un État allié. À l’aide d’une expérience de sondage impliquant des citoyens américains, nous remarquons que bien que les participants soient sensibles aux obligations au titre de traités, leurs effets sont modérés par des facteurs personnels comme l’expertise au sein d’un domaine. De plus, nous remarquons que certaines dyades agresseur-allié au sein de régions spécifiques peuvent façonner les préférences de la population, les participants réagissant davantage à des scénarios basés en Europe qu’à des traitements comparables ayant lieu en Asie.

Keywords:

Alliances & Cyber Conflict

In 2013, a United States Department of Defense task force assessed that offensive cyber operationsFootnote1 should be considered like any other attack on the nation and that using military forces is an appropriate response (Defense Science Board Citation2013). Determinations such as this not only codified the transformation of cyberspace into a domain of military conflict but also heralded a new age in collective security. Beyond threats against its territory, the United States is a party to seven collective defense agreements that oblige Washington to aid its allies in the event of an armed attack (United States Citation2022b). The United States implicitly extends these allied defensive commitments into cyberspace by defining cyber aggression as an armed attack. Indeed, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO. Citation2019) and the United States-Japan Alliance (Japan Citation2019) explicitly acknowledge that cyber operations fall within the scope of their collective security obligations.

However, pronouncements of alliance policies do not guarantee action, and the decision over how the United States would respond to a cyberattack on an allied state is not the purview of political elites alone (Chiba, Johnson, and Leeds Citation2015; Gartzke and Gleditsch Citation2004; Tomz, Weeks, and Yarhi-Milo Citation2020). Public opinion affects policymakers and shapes policy (Kertzer and Zeitzoff Citation2017). This is particularly true regarding the use of military forces, where public considerations like casualty aversion (Gartner Citation2008), outcomes (Eichenberg Citation2005), and inconsistency (Tomz Citation2007) shape the political calculus for policymakers. Public opinion scholarship concerning cyber conflict distinguishes popular attitudes towards cyber and conventional military operations. Specifically, studies involving United States nationals illustrate that these individuals view cyber conflict as a distinct phenomenon, possibly constraining public support for defending allies during cyber conflict (Kreps and Schneider Citation2019). Consequently, expanding United States treaty commitments into this environment may prove illusory if the American public is unwilling to support such endeavors.

To assess how the American public might respond to offensive cyber operations against an allied state, we conducted a survey experiment involving 1,424 United States nationals.Footnote2 The experiment presents a hypothetical scenario that varies (1) mutual defense obligations, (2) casualties, and (3) the aggressor-ally dyad based on region. Following the scenario, participants are asked how much they would favor retaliating through cyber or conventional means. Our findings are consistent with recent scholarship (Guenther and Musgrave Citation2022) that found defense obligations and casualties provoking a desire to aid allies. However, our study also finds that these preferences are not uniform across individuals or situations, with contextual factors playing a pivotal role in determining responses. Our respondents distinguish between situations based on actors and regions, with subjects more willing to respond to a European incident involving Russia and the United Kingdom than an equivalent event in Asia. Furthermore, we find that domain expertise exerts a significant effect on preferences. Individuals more familiar with cybersecurity support allied commitments in cyberspace regardless of geography and appear more reluctant to respond to attacks that produce casualties. This indicates that as the novelty of cyber conflict wanes, people’s preferences change as well, with individuals being more likely to treat cyber means as a normal facet of international security. This is a significant boon for the substantive extension of alliance commitments into the digital domain and the realities of collective cybersecurity.

Cyber Conflict & Public Opinion

Cyber conflict challenges traditional conceptions of coercion and the use of force in international affairs (Buchanan Citation2020; Valeriano, Jensen, and Maness Citation2018). Although eschewing the state-destroying cyberattacks prevalent in popular culture, states have nevertheless embraced cyber operations as an instrument of foreign policy to advance their strategic interests while operating below the threshold of armed conflict (Fischerkeller, Goldman, and Harknett Citation2022). The potential to reshape security conditions through cyber means without incurring severe political or diplomatic costs (Harknett and Smeets Citation2020) has encouraged both the proliferation of military cyber capabilities (Blessing Citation2021) and the need to incorporate cybersecurity within national security strategies (Dunn Cavelty Citation2013).

While elites increasingly espouse a robust response to cyber threats, the public appears more reticent. Nascent public opinion literature on cyber conflict finds that cybersecurity is a severe concern to the public (Raine, Anderson, and Connolly Citation2014). However, while populations take this issue seriously, how they would respond to cyber operations as a form of conflict remains contested. Kreps and Schneider (Citation2019) found that publics perceive cyber operations as different from conventional or nuclear uses of force and are reluctant to escalate aggressively in response to cyberattacks even when those attacks cause destruction equivalent to a conventional attack. Conversely, studies examining the effects of cyber operations suggest that this distinction may be because of the operation’s effects rather than any partiality towards cyber. Experiments by Kreps and Das (Citation2017) and Gross, Canetti, and Vashdi (Citation2017) found that hypothetical cyberattacks that caused the loss of life did not enjoy the same novelty and instead triggered a forceful response analogous to conventional uses of force.

Even as literature increasingly unpacks public reaction to cybersecurity incidents (Kreps and Das Citation2017; Kreps and Schneider Citation2019; Shandler, Gross, Backhaus, et al. Citation2021; Leal and Musgrave Citation2023), it has narrowly framed the realities of cyber conflict by only examining public attitudes of direct participants (i.e., immediate victims and their response). This neglects alternative dispositions, such as cyber operations affecting an allied country where a population may not be victimized but is still expected to undertake action in defense of an ally. Such considerations are particularly acute with the onset of the Russo-Ukrainian War and the prospect of Russian cyber aggression against NATO in response to Western sanctions and military aid to Kyiv (Whyte Citation2022).

Guenther and Musgrave (Citation2022) represent an initial attempt to answer this quandary. Given the uncertainties of extending alliance commitments to cover cyber operations, Guenther and Musgrave leverage survey experiments to investigate how an American population would respond to hypothetical Russian cyberattacks on a NATO ally. They test whether different motivating factors such as formal commitments and normative considerations color reactions as well as how preferences are shaped by other scenario conditions like whether the attack had a military or civilian target or resulted in casualties. The study shows that a treaty commitment significantly increases support for aiding an ally after a cyberattack – especially if the attack produced casualties. However, this digital comradery is not without limits as reactions appear to be tempered by fears of additional retaliation and moderated by the victim being a civilian target.

Although scholarship unpacking the influence of cyber operations on alliance dynamics continues to grow, these are limited on two fundamental fronts. Contemporary studies are oriented towards NATO, which is unsurprising given the importance of cybersecurity within this grouping of states and the cases wherein members have considered invoking allied commitments following malicious behavior in cyberspace. However, such dynamics are not restricted to this geographic region, with allied states in the Indo-Pacific integrating cybersecurity into existing mutual defense agreements. As such, it is necessary to determine whether public preference varies as a function of regional context. Moreover, the influence of domain expertise on individual preferences requires further investigation. This is noteworthy since expertise is shown to temper the response of publics who are the immediate targets of cyber operations (Gomez Citation2019). However, this moderating effect is not tackled by existing studies on alliances. Consequently, it is this existing gap that we endeavor to address.

Research Design & Theoretical Expectations

To address the gaps in the literature, we conducted a survey experimentFootnote3 using hypothetical scenarios to gauge how the American public might respond to cyber operations against allied states. The survey was fielded with a representative sample using Lucid Theorem in December 2022 and recruited 1,424 participants.

The scenarios vary across three (3) experimental treatments: explicit mention of mutual defense commitments (commitment), the presence of casualties (casualties), and aggressor-ally dyads (dyad). This yields a 2x2x2 design with participants randomly assigned to one of eight scenarios based on the variations in the commitment, casualties, and dyad treatments. The commitment treatment varies the scenario such that half the participants are informed that the United States and the allied states are committed to each other’s defense. The casualties treatment, relatedly, varies the severity of the incident by informing half the participants that over a hundred nationalsFootnote4 from the allied state lost their lives following the cybersecurity incident.

Finally, the dyad treatment varies the aggressor-ally dyad within the scenario. Two scenarios are posited based on geographic region, with participants seeing either a Russia-United Kingdom scenario or one involving China-Japan. Varying the actors in the scenario and notably including an Asia-based scenario is a crucial contribution of this study. An actor’s identity may color widespread reactions (Herrmann et al. Citation1997; Rousseau and Garcia-Retamero Citation2007), and scenarios cannot be divorced from ongoing interstate interactions and preconceptions (Brutger et al. Citation2022). Although previous studies have found that populations are concerned about cybersecurity incidents (Kreps and Schneider Citation2019; Shandler, Gross, Backhaus, et al. Citation2021), the extent to which different threats or victims influence those concerns remains unclear. While United States policy documents highlight both Russia and China as malicious actors, they are characterized as different types of threats. The 2022 United States National Security Strategy identifies China as a pacing threat to the United States in a global competition, while Russia is a dangerous but acute threat to be constrained (United States Citation2022a). This distinction in threat perceptions has been echoed in recent cyber strategies (United States Citation2023a, Citation2023b), and different threat perceptions between Russia and China may lead to a divergence in popular responses to their activities.

Similarly, although NATO and the United States-Japan alliance have formally stated that a cyberattack could trigger the alliance’s mutual defense responsibilities (Japan 2019), it is unclear whether the American people feel this commitment equally. Partner identity can be an essential component of alliance reliability (Crescenzi et al. Citation2012; Mattes Citation2012), with an affinity between partners adding credibility to security commitments. Consequently, while the United Kingdom and Japan are prominent allies, American willingness to defend both equally cannot be assumed. Although varying our experiment along attacker-victim dyads (Russia-United Kingdom and China-Japan) collapses these differences in threat perception and victim identity into a single variable, it allows us to distinguish whether cybersecurity commitments are categorical or contextual in the public’s minds.

After reading the scenario, participants use a six-point Likert scale to indicate their support for retaliation through cyber or conventional means. Participants are asked whether “the United States should conduct a [retaliatory cyber attack/conventional retaliatory military operation] against the aggressor despite the possibility of an equivalent retaliatory strike against the U.S. [critical infrastructure/military interests]”. We diverge from related studies in that we ask participants to rate their support for broad, rather than specific, modes of response (i.e., conventional retaliatory military operation as opposed to an airstrike or special operations raid). We assumed limited participant knowledge of the nuances of conventional and cyber operations and, instead, leveraged the observed means-based difference driving preference, which can also be validated by our design. Finally, it is essential to note that, unlike previous studies, participants are explicitly informed of possible repercussions if they were to retaliate. This minimizes the risk of participants discounting the future cost of their decisions – a common occurrence when individuals are faced with hypothetical scenarios (Huddleston Citation2019).

The experiment then captures participants’ cybersecurity knowledge (cyber), political knowledge (political), foreign policy preferencesFootnote5 (cooperative, militant, isolationist), ideological alignment (ideology), and (6) demographic information as control variables. These control variables are important because they allow us to assess the extent to which individual knowledge bases may shape policy preferences in conflict situations. This is particularly significant as it pertains to cybersecurity knowledge, as including this relative expertise as a control variable will help us discern how much a respondent’s reaction to a cyber incident may be driven by the novelty of the cyberattacks and popular narratives of cyber doom (Jarvis et al. Citation2017) versus a considered opinion based on familiarity.

We use a series of prospective hypotheses to structure our analysis. Research on alliances finds that populations are willing to absorb costs associated with fulfilling treaty obligations owing to an underlying sense of morality, shared identity, strategic interest, and reputation (Berejikian and Justwan Citation2021; Tomz and Weeks Citation2021). Guenther and Musgrave (Citation2022) demonstrated that this dynamic can carry into the digital domain and a willingness to aid allies following a cyberattack. Consequently, we anticipate that while the distinct logic of cyberspace may exist, the binding logic of alliances endures and elicits a willingness to aid an ally. Importantly, this design presents a specific challenge in assessing underlying motivations given the relationship between our commitment and dyad variable. While we vary the countries being attacked in each vignette, both victims – the United Kingdom and Japan – are prominent allies of the United States. This makes the invocation of American obligations viable but also challenges our commitment variable, as respondents may be aware of the bilateral relationship regardless of whether it is mentioned in the scenario or not. As such, our commitment variable is best conceived as measuring the effects of explicitly telling respondents that an obligation exists rather than whether the commitments are present.

H.1

Explicitly highlighting existing alliance commitments increases the likelihood that the public will support defending allies from cyber threats.

While effects-based cyber operations that extend beyond virtual harm and cause physical damage in the real world are rare, they exist and have increasingly approached the line of inflicting human casualties. Cyberattacks have crippled medical facilities leading to the indirect loss of life (Miller Citation2022a), and unsuccessful attacks on both a petrochemical plant in Saudi Arabia (Perlroth and Krauss Citation2018) and a water treatment plant in Florida (Greenberg Citation2021) appeared to have had lethal intent. Experimental research consistently identifies cyberattacks that cause human casualties can trigger a strong public reaction comparable to the conventional uses of force (Shandler, Gross, Backhaus, et al. Citation2021). Although these studies focus on the target population as the immediate victim, a similar phenomenon appears to extend to foreign states, with cyber-induced casualties increasing both the stakes associated with the incident and the salience of the alliance (Gomez and Villar Citation2018; Guenther and Musgrave Citation2022).

H.2

Casualty-producing cyber operations increase the likelihood that the public will support defending allies from cyber threats.

As noted earlier, we also cannot be deaf to the context in which a cyber operation may occur. While the United States has extended alliance commitments to include cybersecurity in Europe and Asia, it is unclear whether the population would value these commitments equally. Europe and Asia are distinct realms of geopolitical competition (United States Citation2022a), and public polls show that this difference has resonated with the broader public. Americans have prioritized European security since the war in Ukraine (Smeltz et al. Citation2022). While Russia is primarily seen as an “enemy,” China is contextualized as a “competitor” (Silver, Gubbala, and Lippert Citation2023). As understandings of national interests are a critical determinant of alliance creation and fulfillment (Leeds, Mattes, and Vogel Citation2009), these divergent views about Asia and Europe as American priorities may translate into different willingness to aid regional partners following an act of foreign aggression. Conversely, literature on alliance reliability suggests that the desire of the United States public to aid a partner may ultimately be predicated on endogenous concerns, including the need to maintain the credibility of the alliance (Morrow Citation2000), international reputation (Gibler Citation2008; Crescenzi et al. Citation2012), or values (Bennis, Medin, and Bartels Citation2010; Tomz and Weeks Citation2013). If such internal motives are more significant than regional contexts, we should not see a distinction between our dyads.

H.3a

Cyber operations against an ally in Europe will increase the likelihood that the public will support defending allies.

H.3b

Cyber operations against an ally in Asia will increase the likelihood that the public will support defending allies.

H.3c (null)

The aggressor-ally dyad will have no effect on the likelihood that the public will support defending allies.

Lastly, we cannot dismiss the possibility that widespread reactions to cyber operations are the byproduct of ignorance more than intent. Hyperbolic depictions of cyber conflict are prominent in both news coverage and popular media (Jarvis, Macdonald, and Whiting Citation2017) and may warp public opinion in ways that are not conducive to the realities of cybersecurity. Shandler, Gross, Backhaus, et al. (Citation2021) and Gomez and Whyte (Citation2021) demonstrated that greater familiarity with cybersecurity could influence policy preferences and assuage calls for retaliation. A similar expertise-based rationale may color alliance commitments as well.

H.4

The public’s reactions to a cyber operation against an ally will be moderated by the individual’s level of domain expertise.

Analysis & Discussion

A total of 1,424 participants were recruited for this experiment. Corresponding balance checks (see Supplementary Material Appendix D) reveal successful randomization. On average, participants are 45 years of age, with 637 participants (44.73%) identifying as male. Regarding education, most participants (66.08%) attended college for at least two years and reported consuming the news four (4) times within the week on average. Regarding their ideological orientation, the sample consists primarily of moderates (3.93, SD = 1.63) and does not lean excessively towards either the Democrat or Republican camp. Concerning underlying policy attitudes, participants slightly favor cooperative (4.120, SD = 1.01) policies as opposed to militantism (3.9, SD = 0.78) or isolationism (3.7, SD = 0.88)Footnote6. However, domain expertise is poor (0.29, SD = 0.24), with limited knowledge of the political system of the United States (0.4, SD = 0.29).

As for the outcome variables, support for cyber (3.37, SD = 1.45) or conventional (3.26, SD = 1.42) retaliation is comparable irrespective of the corresponding treatments. However, a corresponding t-test shows these to be statistically distinct (2.023, p < 0.05), with participants favoring responding through cyber means. To test our proposed framework, we regress cyber and conventional on the (1) commitment, (2) casualties, and (3) dyad treatments along with the covariates mentioned previously using Ordinary Least Squares. The results are seen in . As a robustness check, two additional models are specified using Ordinal Logistic Regression (see Supplementary Material Appendix B).

Table 1. Main effects models.

shows that mutual defense commitments and different aggressor-ally dyads (i.e., Russia-United Kingdom) increase support for retaliation through cyberspace. This supports our H1 hypothesis and state identity mattering for fulfilling alliance responsibilities (H3a). These treatments, however, do not significantly influence public support for retaliation through conventional means and raise the possibility that the American public views events in cyberspace as distinct, requiring different logic to formulate an adequate response. Such distinctions may be grounded on their knowledge of the domain and its possibilities. Interestingly, casualties do not appear to impact shaping respondent preferences. This challenges our severity hypothesis (H2) and studies (Gross, Canetti, and Vashdi Citation2017; Leal and Musgrave Citation2023; Shandler, Gross, Backhaus, et al. Citation2021) that find significant reactions to cyber-casualty events. Two additional models with (cyber) domain expertise interacting with the respective treatments are specified as a further test.

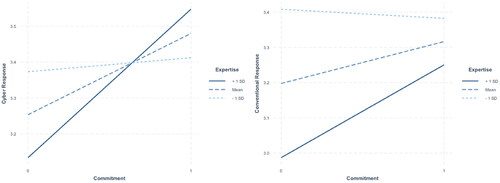

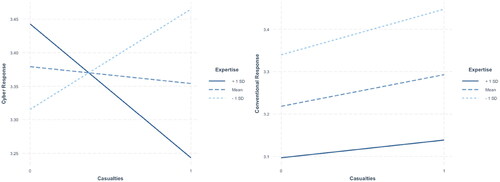

Both models show comparable values concerning the main effects. The interacted terms (see Supplementary Material Appendix C), however, provide further insight into the decision-making logic of the participants. Across both models, the interaction between explicit commitments and cyber knowledge increases support for cyber and conventional retaliation (see ). When directly informed of existing defense commitments, a unit increase in domain knowledge encourages a response through both cyber (0.792, p < 0.05, CILow = 0.187, CIHigh = 1.397) and conventional (0.612, p < 0.05, CILow = 0.020, CIHigh = 1.204) means. As we hypothesize (H4), this suggests that participants with greater familiarity with cybersecurity concepts and events see the applicability of alliances to this domain. Furthermore, the salience of the incident (i.e., casualties) appears also to be contingent on domain expertise. Still, it is only statistically significant with respect to retaliation through cyber means ().

Interacting casualties with domain expertise suppresses public support for a cyber-based retaliation (−0.738, p < 0.05, CILow = −1.344, CIHigh = −0.133). It is worth noting that the magnitude and direction of this interaction nearly nullifies that of commitment and domain knowledge. This observation leads to two distinct perspectives. Knowledgeable publics may feel that severe cybersecurity incidents (e.g., leading to loss of life) are rare occurrences and might not be willing to commit themselves (Gomez and Whyte Citation2021), or greater familiarity with cybersecurity may lead to a rejection of our hypothetical scenario given the non-existence of cyber-casualty events. The design of our experiment does not allow us to pick one explanation or another definitively but establishes an avenue for future research.

Finally, the aggressor-dyad treatment increases support for retaliation but is only statistically significant when doing so through cyber means. The fact that participants are willing to defend an ally when the dispute involves Russia and the United Kingdom is telling (H3a). This heightened reactivity may be a reaction to the ongoing war in Ukraine, an affinity for the United Kingdom, or a greater willingness to engage in cyber conflict with Russia over China (Jensen and Valeriano Citation2019). We cannot discern the underlying motivation for this finding. Still, the muted results of the China-Japan scenario are significant and suggest that dynamics present in European scenarios may not be evident in other regions and that respondents distinguish between regional contexts when evaluating a scenario.

Conclusion

We find significant evidence supporting H1 and that explicit statements of allied commitments increase the willingness of publics to aid allies following a malicious cyberattack. This result echoes Guenther and Musgrave (Citation2022), indicating that extending alliance responsibilities to include cybersecurity accentuates public preferences. However, these reactions remain confined to the digital domain. We find no evidence of cross-domain dynamics with individuals preferring to respond to a cyberattack with cyber means only – not conventional military forces. Furthermore, it is significant that the effects of explicit commitments were evident despite both of our victims (United Kingdom and Japan) being prominent allies of the United States. Respondents who were not given the commitment treatment may have been aware of the preexisting relationship and willing to aid the victim state. That a statistically significant margin nevertheless boosted this willingness by directly communicating this commitment illustrates that extending allied commitments to cyberspace has utility beyond signaling and can meaningfully influence public opinion even when sympathetic sentiment may exist. Conversely, while not tested in this study, we would anticipate a reluctance to extend such support to non-allies or even partners where the commitments to mutual cyber defense are not explicit.

Although we find a willingness to abide by allied commitments in cyber conflict, our results show that this phenomenon is colored by context and individual attributes. Participants were not responsive to our casualty variable, which contrasts sharply with our expectations (H2) and previous studies that found a significant reaction to cyber-casualties. Our finding suggests that while the public is highly reactive when casualties are inflicted against their country, this same consideration may not be extended to partners. Similarly, participants demonstrated greater responsiveness to the European scenario involving Russia and the United Kingdom than the China-Japan dyad. This result was not apparent in previous studies that only looked at NATO and is evidence in support of our contexts hypothesis (H3) and indicates that responses to a cyber incident are influenced by the states involved. Unfortunately, our experiment cannot state whether this difference stems from a greater willingness to respond to a European scenario or wariness towards a similar event in Asia. Regardless of the mechanism, that this distinction emerged at all suggests that alliance obligations may not be equally felt or applied in different situations. Such results may foreshadow significant difficulties for alliances attempting to respond to harmful cyber operations and warrants further study.

Lastly, the individual characteristics of our participants were important for explaining their preferences. Individual elements like news awareness, political knowledge, and support for international cooperation were all significant and increased a respondent’s willingness to aid a stricken ally. We also find that familiarity with cybersecurity did substantively influence preferences. Participants more familiar with cyber issues did not distinguish between the European and Asian dyads and seemed more open to fulfilling commitments to allies in both cases. However, increased domain awareness decreased support for responding to cyberattacks that caused casualties. This result could indicate skepticism towards our hypothetical scenario given the current lack of cyber-casualties in the real world or an increased risk sensitivity following a significant attack. Nevertheless, as cyber conflict becomes normalized as a common feature of world affairs, our results imply that peoples’ reactions will evolve as they acclimate to the digital domain. This finding is significant for understanding the behavior of policymakers. Foreign policy and defense professionals are already familiar with international cyber conflict, and their behavior will more likely gravitate towards our high-knowledge respondents. We can better predict practitioner behavior by assessing how this knowledge base informs preferences. Notably, this high-information population was most supportive of allied cyber commitments, suggesting that policymakers may back such obligations even if the general population is more cautious.

Cyber conflict is no longer a fringe security concern but a burgeoning domain of international competition (Fischerkeller, Goldman, and Harknett Citation2022). As governments embrace cybersecurity as a national security issue and develop their digital capabilities (Harknett and Smeets Citation2020), security alliances will be expected to expand their digital portfolios. Already, we have seen evidence of this evolution with an Iranian cyberattack against Albania in 2022, stoking a significant discussion about NATO's Article V (Miller Citation2022b). Determining how such situations are addressed is not solely the privilege of political elites. Our study finds that while populations support fulfilling alliance commitments following cyberattacks, this support is less a function of a blanket adherence to treaty commitments and instead predicated on individual and contextual factors. These observations need not paint a bleak picture of collective cybersecurity. Rather, their value lies in highlighting potential intervention points where sources of misperception can be remedied. Increasing public knowledge of cybersecurity can counter alarmist narratives and lead to broader acceptance of cyber as a normal defense responsibility. Moreover, as national security professionals have identified cyber as a form of “armed attack” akin to conventional uses of force, this conclusion must be inculcated within the public to prevent misinterpretations and fortify commitments to allies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (221.9 KB)Notes

1 “Offensive cyber operations” and “cyber operations” are used interchangeably to refer to the exercise of cyber power that degrade or destroy some aspect of the target’s networks, operations, or functions (Valeriano, Jensen, and Maness Citation2018). However, it is worth noting that most operations reflect limited, if any, physical effects (Harknett and Smeets Citation2020; Zetter Citation2022). Yet in spite of this reality, there notion of highly disruptive operations remains persistent amongst the public (Jarvis, Macdonald, and Whiting Citation2017).

2 The experiment underwent an ethics review at the University of Cincinnati and was approved, IRB ID: 2022-0461; In excess of the apriori power analysis requiring a sample size of 1,333 for an alpha of 0.8.

3 See Supplementary Material Appendix A for the corresponding instrument.

4 Cyber conflict scholars remain divided over the benefit of including casualties as part of the treatment given the rarity of such events. However, as the public’s understanding of this issue may be shaped by narratives that include this possibility, there may be some benefit to matching these expectations.

5 These include cooperative internationalism, militant internationalism, and isolationism (Kertzer et al. Citation2014).

6 Post-hoc analysis reveals the following Cronbach Alphas: cooperative (0.830), militant (0.588), and isolationist (0.684).

References

- Bennis, Will M., Douglas L. Medin, and Daniel M. Bartels. 2010. “The Costs and Benefits of Calculation and Moral Rules.” Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 5 (2): 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610362354

- Berejikian, Jeffrey, and Florian Justwan. 2021. “Defense Treaties Increase Domestic Support for Military Action and Casualty Tolerance.” Contemporary Security Policy 43 (2): 308–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2021.2023290

- Blessing, Jason. 2021. “The Global Spread of Cyber Forces, 2000–2018.” In 13th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Going Viral, edited by Tatiana Jančárková, Lauri Lindström, Gabor Visky, and Philippe Zotz, 233–256. Tallinn: NATO CCDCOE.

- Brutger, Ryan, Joshua Kertzer, Jonathan Renshon, and Chagai Weiss. 2022. Abstraction in Experimental Design. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Buchanan, Ben. 2020. The Hacker and the State. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Chiba, Diana, Jesse C. Johnson, and Brett Ashley Leeds. 2015. “Careful Commitments.” Journal of Politics 77 (4): 968–982. https://doi.org/10.1086/682074

- Crescenzi, Mark J. C., Jacob D. Kathman, Katja B. Kleinberg, and Reed M. Wood. 2012. “Reliability, Reputation, and Alliance Formation.” International Studies Quarterly 56 (2): 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00711.x

- Defense Science Board 2013. Resilient Military Systems and the Advanced Cyber Threat. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense.

- Dunn Cavelty, Myriam. 2013. “From Cyber-Bombs to Political Fallout.” International Studies Review 15 (1): 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/misr.12023

- Eichenberg, Richard C. 2005. “Victory Has Many Friends: U.S. Public Opinion and the Use of Military Force.” International Security 30 (1): 140–177. https://doi.org/10.1162/0162288054894616

- Fischerkeller, Michael P, Emily Goldman, and Richard J. Harknett. 2022. Cyber Persistence Theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gartner, Scott S. 2008. “The Multiple Effects of Casualties on Public Support for War.” American Political Science Review 102 (1): 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055408080027

- Gartzke, Erik, and Kristian S. Gleditsch. 2004. “Why Democracies May Actually Be Less Reliable Allies.” American Journal of Political Science 48 (4): 775–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00101.x

- Gibler, Douglas M. 2008. “The Costs of Reneging: Reputation and Alliance Formation.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 52 (3): 426–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002707310003

- Gomez, Miguel Alberto N. 2019. “Sound the Alarm! Updating Beliefs and Degradative Cyber Operations.” European Journal of International Security 4 (2): 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2019.2

- Gomez, Miguel Alberto, and Eula Bianca Villar. 2018. “Fear, Uncertainty, and Dread: Cognitive Heuristics and Cyber Threats.” Politics and Governance 6 (2): 61–72. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i2.1279

- Gomez, Miguel Alberto, and Christopher Whyte. 2021. “Breaking the Myth of Cyber Doom.” International Studies Quarterly 65 (4): 1137–1150. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab034

- Greenberg, Andy. 2021. “A Hacker Tried to Poison a Florida City’s Water Supply, Officials Say.” Wired. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.wired.com/story/oldsmar-florida-water-utility-hack/.

- Gross, Michael L., Daphna Canetti, and Dana R. Vashdi. 2017. “Cyberterrorism: Its Effects on Psychological Well-Being, Public Confidence and Political Attitudes.” Journal of Cybersecurity 3 (1): 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyw018

- Guenther, Lindsey, and Paul Musgrave. 2022. “New Questions for an Old Alliance: NATO in Cyberspace and American Public Opinion.” Journal of Global Security Studies 7 (4). https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogac024

- Harknett, Richard J., and Max Smeets. 2020. “Cyber Campaigns and Strategic Outcomes.” Journal of Strategic Studies 45 (4): 534–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1732354

- Herrmann, Richard K., James F. Voss, Tonya Y. E. Schooler, and Joseph Ciarrochi. 1997. “Images in International Relations.” International Studies Quarterly 41 (3): 403–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00050

- Huddleston, R. Joseph. 2019. “Think Ahead: Cost Discounting and External Validity in Foreign Policy Survey Experiments.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 6 (02): 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2018.22

- Japan. 2019. “Japan-U.S. Security Consultative Committee (Japan-U.S. “2 + 2”).” Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Accessed April 19, 2019. https://www.mofa.go.jp/na/fa/page3e_001008.html.

- Jarvis, Lee, Stuart Macdonald, and Andrew Whiting. 2017. “Unpacking Cyberterrorism Discourse.” European Journal of International Security 2 (1): 64–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2016.14

- Jensen, Benjamin, and Brandon Valeriano. 2019. “What Do We Know About Cyber Escalation?.” Atlantic Council. Accessed November, 2019. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/What_do_we_know_about_cyber_escalation_.pdf.

- Kertzer, Joshua D., Kathleen E. Powers, Brian C. Rathbun, and Ravi Iyer. 2014. “Moral Support: How Moral Values Shape Foreign Policy Attitudes.” Journal of Politics 76 (3): 825–840. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381614000073

- Kertzer, Joshua D., and Thomas Zeitzoff. 2017. “A Bottom‐up Theory of Public Opinion about Foreign Policy.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (3): 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12314

- Kreps, Sarah, and Debak Das. 2017. “Warring from the Virtual to the Real.” Research & Politics 4 (2): 205316801771593. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168017715930

- Kreps, Sarah, and Jacquelyn Schneider. 2019. “Escalation Firebreaks in the Cyber, Conventional, and Nuclear Domains.” Journal of Cybersecurity 5 (1): tyz007. https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyz007

- Leal, Marcelo, and Paul Musgrave. 2023. “Hitting Back or Holding Back in Cyberspace: Experimental Evidence regarding Americans’ Responses to Cyberattacks.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 40 (1): 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/07388942221111069

- Leeds, Brett Ashley, Michaela Mattes, and Jeremy S. Vogel. 2009. “Interests, Institutions, and the Reliability of International Commitments.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (2): 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00381.x

- Mattes, Michaela. 2012. “Reputation, Symmetry, and Alliance Design.” International Organization 66 (4): 679–707. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081831200029X

- Miller, Maggie. 2022a. “The mounting death toll of hospital cyberattacks,” Politico. Accessed December 29, 2022. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/12/28/cyberattacks-u-s-hospitals-00075638

- Miller, Maggie. 2022b. “Albania weighed invoking NATO's Article 5 over Iranian cyberattack.” Politico. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/10/05/why-albania-chose-not-to-pull-the-nato-trigger-after-cyberattack-00060347.

- Morrow, James D. 2000. “Alliances: Why Write Them down?” Annual Review of Political Science 3 (1): 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.63

- NATO. 2019. “NATO will defend itself.” NATO. Accessed August 27, 2019. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_168435.htm?selectedLocale=en.

- Perlroth, Nicole, and Clifford Krauss. 2018. “A cyberattack in Saudi Arabia had a deadly goal. Experts fear another try.” New York Times. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/15/technology/saudi-arabia-hacks-cyberattacks.html.

- Raine, Lee, Janna Anderson, and Jennifer Connolly. 2014. “Cyber Attacks Likely to Increase.” Pew Research Center. Accessed October 29, 2014. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2014/10/29/cyber-attacks-likely-to-increase/.

- Rousseau, David L., and Rocio Garcia-Retamero. 2007. “Identity, Power, and Threat Perception – A Cross-National Experimental Study.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 51 (5): 744–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002707304813

- Shandler, Ryan, Michael Gross, Sophia Backhaus, and Daphna Canetti. 2021. “Cyber Terrorism and Support for Retaliation.” British Journal of Political Science 52 (2): 1–19.

- Shandler, Ryan, Michael L. Gross, and Daphna Canetti. 2021. “A Fragile Public Preference for Cyber Strikes.” Contemporary Security Policy 42 (2): 135–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2020.1868836

- Silver, Laura, Sneha Gubbala, and Jordan Lippert. 2023. “Americans See Both Russia and China in a Negative Light – But More Call Russia an Enemy.” Pew Research Center. Accessed October 5. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/05/10/americans-see-both-russia-and-china-in-a-negative-light-but-more-call-russia-an-nemy/#:∼:text=Nearly%20two%2Dthirds%20of%20Americans,see%20it%20as%20a%20partner.

- Smeltz, Dina, Ivo H. Daalder, Karl Friedhoff, Craig Kafura, and Emily Sullivan. 2022. “Survey of Public Opinion on U.S. Foreign Policy.” Global Affairs. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/2022-chicago-council-survey.

- Tomz, Michael. 2007. “Domestic Audience Costs in International Relations.” International Organization 61 (04): 821–840. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818307070282

- Tomz, Michael R., and Jessica L. P. Weeks. 2013. “Public Opinion and the Democratic Peace.” American Political Science Review 107 (4): 849–865. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000488

- Tomz, Michael, and Jessica Weeks. 2021. “Military Alliances and Public Support for War.” International Studies Quarterly 65 (3): 811–824. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab015

- Tomz, Michael, Jessica Weeks, and Karen Yarhi-Milo. 2020. “Public Opinion and Decisions about Military Force in Democracies.” International Organization 71 (1): 526–545.

- Valeriano, Brandon, Benjamin Jensen, and Ryan C. Maness. 2018. Cyber Strategy: The Evolving Character of Power and Coercion. New York: Oxford University Press.

- United States 2022a. National Security Strategy. Washington, D.C.: The White House.

- United States 2022b. U.S. Collective Defense Arrangements. Washington, D.C.: Department of State.

- United States 2023a. National Cybersecurity Strategy. Washington, D.C.: The White House.

- United States 2023b. 2023 Cyber Strategy of the Department of Defense. Washington, D.C: Department of Defense.

- Whyte, Christopher. 2022. “An Isolated Russia Will Pose New Cyber Threats.” The National Interest. Accessed March 18, 2022. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/techland-when-great-power-competition-meets-digital-world/isolated-russia-will-pose-new-cyber.

- Zetter, Kim. 2022. “What It Means that the U.S. Is Conducting Offensive Cyber Operations Against Russia.” Zero Day. Accessed June 18, 2022. https://zetter.substack.com/p/what-it-means-that-the-us-is-conducting.