ABSTRACT

This study looks at educational inequality in China, a country that has greatly expanded access to education in recent decades. It uses a sequential logit model to study the changing impact of family background on educational transitions, comparing birth cohorts that completed their schooling during different stages of the market transition process. Data are derived from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a large and nationally representative household survey that provides detailed retrospective information. The findings show that educational inequality in reform-era China followed a pattern of maximally maintained inequality. Although educational expansion diminished disparities in obtaining basic education, inequality persisted or even increased in the more advanced levels, especially at the crucial transition to senior high school. Inequalities only started to decrease for the most recent cohorts, when higher-level transitions became almost universal among high-status groups. These findings can be explained by the nature of China’s economic and educational policies, which heavily favoured urban residents and other privileged groups.

Introduction

Transition societies experience widespread social upheaval and restructuring, as the old social and economic order is replaced by the new. China is an exemplary case in this regard, as its ‘Great Transformation’ is unparalleled in terms of magnitude, speed, and geo-political significance. The changing nature of social stratification in transitional societies is an important topic in sociological research (Jackson & Evans, Citation2017; Nee, Citation1989). I contribute to this field by describing trends in educational inequality during China’s Reform Era (1978-present), focusing on the changing role of parents’ education, household registration and political capital. I limit myself to the reform period because I am interested in the most recent developments, and because variations in educational opportunities under state socialism (1949–1977) have been well documented elsewhere (Deng & Treiman, Citation1997; Zhou et al., Citation1998).

China is a particularly interesting case to study historical trends in educational stratification. Following the 1978 reforms, it moved from a highly egalitarian state socialist system to a market economy. Contrary to most other transitional societies, China’s market transition took place in a context of relative political stability and was accompanied by an unprecedented economic boom, which increased both educational demand and returns to education. In the new market economy, educational success has become synonymous with economic advancement and social prestige. A fierce competition over access to more prestigious schools and universities emerged, and even the most disadvantaged parents generally have high hopes for their children’s educational careers (Liu & Xie, Citation2015). In spite of skyrocketing socio-economic and geographic inequality, educational advancement continues to be seen as a relatively meritocratic process in China. This is partially the result of the nationwide system of high school and college entrance examinations, which was (re)instated following the market transition. The Confucian ideal of meritocracy and the promise of social mobility are important elements of the Communist Party’s ‘socialist market economy’, and help to explain why the Chinese population continues to accept increasing levels of distributive inequality (Whyte & Im, Citation2014).

The study extends the literature on educational inequality in China in a number of ways. First, it compares cohorts that completed their schooling during different stages of the market transition process, including the most recent graduates, and addresses all relevant transitions within an integrated framework. It thereby provides a more comprehensive picture of trends in educational stratification than previous studies, which generally focus on specific transitions and time periods. Second, it looks at both relative and absolute trends in inequality of educational opportunity, in order to address some of the shortcomings of the classic educational transition model (Mood, Citation2010). Finally, it uses a large and nationally representative dataset, which contains highly detailed measures of respondents’ social origin.

The following sections provide some historical background on the Chinese education system, followed by the analytical strategy and empirical results. Finally, I discuss how my findings compare to those observed in other societies and identify potential explanations for the observed pattern of inequality.

Background: the Chinese education system

China’s education system is characterised by an unusually high degree of standardisation and uniformity. In spite of massive social, economic and political upheavals, its underlying structure has remained virtually unchanged since the mid-20th century (Treiman, Citation2013). Children usually start primary school, which takes six years, at the age of six or seven. This is followed by three years of junior high school (JHS), three years of senior high school (SHS), and three or four years of college. The following sections provide a brief historical overview of educational policy in China and discuss potential implications for educational inequality.

1949–1977: The Maoist period

In line with the egalitarian political objectives, the focus of educational expansion during the Communist era was on elementary schooling, and children from peasants and workers were sometimes given preferential treatment in accessing higher education (Hannum et al., Citation2007; Tsang, Citation2000). Various studies have shown that class-based inequalities in education were comparatively low during the Communist era (Gruijters et al., Citation2019; Zhou et al., Citation1998). The impact of family background on educational outcomes was particularly suppressed during the Cultural Revolution, a period of great social upheaval during which universities were closed and urban students were ‘sent down’ to work in the countryside (Deng & Treiman, Citation1997). Although the Cultural Revolution policies expanded access to basic education in rural areas, the quality of schooling was often poor (Andreas, Citation2004).

While suppressing class-based advantages, the state socialist system under Mao perpetuated or created other forms of inequality, especially between rural and urban residents and between Communist Party officials and others. A particular aspect of social stratification in China is the household registration or hukou system, which limits geographic mobility and assigns rural residents a lower level of public services and benefits, effectively creating an institutionalised form of social inequality (Rozelle & Hell, Citation2020; Wu & Treiman, Citation2004). In studying educational stratification in China, it is therefore important to consider the political status and household registration of the household of origin, in addition to traditional measures such as parental class and education.

1978-present: the market era

After the death of Mao in 1976, the reformist Party leadership under Deng Xiaoping soon embarked on a fundamentally different course, dismantling the planned economy, and initiating the transition to a market-based economic system. The impact of the market transition on educational policy can hardly be underestimated. The reformers ‘not only repudiated the radical education policies of the Cultural Revolution, but completely disavowed class levelling in the cultural field, freeing the party from a doctrinal commitment that had complicated its educational policies since 1949’ (Andreas, Citation2009, p. 224). The ideological goals of the Maoist period were replaced by the principles of meritocracy, efficiency and technical expertise. Following Deng Xiaoping’s call to ‘respect knowledge and talent’ (1977), the SHS entrance examination (zhongkao) and college entrance examination (gaokao) were (re)instated. At the same time, the main focus of educational policy shifted from providing broad-based access to training a new class of technical experts (Pepper, Citation1996; Tsang, Citation2000).

A major implication of the post-1978 reforms was the increasing horizontal differentiation of the educational system. Essentially, the reformers envisioned a bifurcated educational system, ‘with a small “elite” sector to train the first-class scientists and engineers (…) alongside a large, “mass” sector that is expected to provide basic educational skills, with the possibility of additional vocational training, for the majority’ (Rosen, Citation1985, p. 301). This was accomplished through the (re-)establishment of key point secondary schools, which purposely prepare the most promising students for the college entrance examination. Key point schools have better funding and more qualified teaching staff, and admission is limited to those with very high test scores (Ye, Citation2015). High demand in combination with the crucial importance of standardised entrance tests created a system geared towards exam preparation. Test-based teaching permeates all the way down to the primary level, and students with little prospect of excellent test scores frequently become demotivated or leave the education system altogether (Andreas, Citation2004; Hannum et al., Citation2011).

In spite of its meritocratic rhetoric, the Chinese state continues to play an important role in the allocation of resources, including educational credentials (Bian & Logan, Citation1996). As a result, state policy and institutional arrangements remain a crucial determinant of educational inequality. Education policy during the market era has often been described a urban-biased (Tam & Jiang, Citation2015). Since the early 1980s, a process of decentralising educational funding has taken place in the name of creating a more diversified revenue base (Tsang, Citation2000). In practice, this created increased disparities in the quality and availability of education between regions, as well as between rural and urban areas within regions (Hannum & Wang, Citation2006). Decentralisation therewith entrenched or even intensified hukou-based inequality. In effect, China operates two school systems, one for rural and one for urban children (Rozelle & Hell, Citation2020). Rural schools tend to be of lower quality and children with rural hukou status were generally not allowed to attend urban schools, even if their parents had migrated to urban areas (Lai et al., Citation2014).

A further reform involved the gradual marketisation of the educational system, especially through the introduction of tuition fees. Although basic education (primary and JHS) is largely free, cost can constitute a substantial barrier to entry for SHS and higher education. Tuition fees have increased dramatically since the early 1990s, and are now very high both in international comparison and relative to household income. For example, it was estimated that for a family living at the poverty line, the annual cost of sending a child to SHS was equivalent to 4 times the annual per capita income, while university costs over 9 times that amount (Wang et al., Citation2011).

Marketisation has also created opportunities for wealthy parents to directly influence their children’s educational outcomes. For example, parents may pay a substantial fee to allow their child to attend school in another district, or to attend a key point school without obtaining the required test score (Tsang, Citation2000). Parents can also decide to avoid the public system altogether and send their child to a private school. Although the core of the education system remains government-run, private schools became a common phenomenon during the 1990s, particularly at the secondary and tertiary level.

The initial effect of the post-1978 reforms was a steep decline in enrolment rates, particularly at the secondary level, as substandard rural schools established during the Cultural Revolution were closed (Andreas, Citation2009; Treiman, Citation2013). Another factor that contributed to the decline in (rural) enrolment rates was the introduction of the household responsibility system, in which collective farming was replaced by individual family plots. An unintended side-effect of this reform was that it increased the opportunity cost of sending teenage children to school (Wu, Citation2010).

Eventually, however, the economic success of the market reforms fuelled the need for skilled labour, and thereby the demand for education (Tsang, Citation2000). Educational attainment increasingly became an essential marker of social status and the key to success in the new market economy.

Educational expansion during the early reform period was largely focused on primary and junior secondary education, with comparatively less expansion at the senior secondary and tertiary level (Treiman, Citation2013). In line with the bifurcated approach, educational officials had long worried that broadening access to these higher levels would lead to a drop in quality. As a result, a fierce competition over the limited number of university places emerged, which is reflected in the emergence of a vast extracurricular tuition industry and an intense pressure on students to perform well in exams. Driven by economic imperatives and the increasing demand for higher education from the emerging middle class, the State Council ushered in a new phase of educational reforms with its 1998 ‘Plan for Revitalizing Education in the Twenty-First Century’, which largely focused on expanding tertiary enrolment. The annual number of higher education entrants increased from 1.1 million in 1998 to 5.0 million in 2005 and 7.2 million in 2014 (National Bureau of Statistics of China, Citation2015). The increase in enrolment was not accompanied by a corresponding increase in public funding, however, so that colleges were forced to drastically increase tuition and other fees to cover the cost of the expansion. Since 2002, China has also rapidly expanded vocational secondary education, especially in rural areas. These schools are often of low quality, however, and do not provide a pathway to tertiary education (Rozelle & Hell, Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2018).

Educational inequality in the market era

The purpose of this study is to analyse trends in educational stratification during China’s market area (1978-present). Empirical evidence suggests that educational inequality increased in the period immediately following the 1978 market reforms (Deng & Treiman, Citation1997; Zhou et al., Citation1998). Zhou et al. concluded that reform ‘appears to have favored the most advantaged groups in the population: the children of high-rank cadres and professionals, residents of large cities, and men more than women’ (Zhou et al., Citation1998, p. 217). This is hardly surprising because the reforms followed the Cultural Revolution, a unique experiment in class levelling in education. We know comparatively less about the trends in educational mobility during the market transition process.

In order to explain long-term trends in inequality of educational opportunity, Raftery and Hout (Citation1993) developed the Maximally Maintained Inequality (MMI) hypothesis. MMI states that inequalities at a given level of education will only reduce when the demand from advantaged groups has been saturated. For example, as high school attendance becomes universal, class-based differences in the transition to high school will, by definition, disappear. At this point, however, children from more advantaged families are likely to seek a tertiary degree in order to maintain their relative advantage. As a result, educational inequality shifts from lower- to higher-level transitions as societies move from elite to mass education. If the MMI hypothesis holds, we would expect inequality of opportunity to decline only for transitions where attendance from high-status children has become saturated, and to remain stable in all other cases. Trends in educational inequality conforming to the MMI pattern have been observed in a variety of contexts (Blossfeld et al., Citation2015; Gamoran, Citation2001), but the hypothesis has not yet been comprehensively tested in post-reform China.

Studies of educational inequality in China have generally focused on specific transitions and relatively brief periods. For example, Wu (Citation2010) suggested that household registration and fathers’ socio-economic status became increasingly important determinants of high school enrolment and transitions between 1990 and 2000. Using more recent data, Yeung (Citation2013) found a decreasing effect of fathers’ education on SHS transitions and an increasing effect on the transition to college following the 1998 higher education reforms.

In order to fully understand the implications of China’s market transition for educational inequality, there remains a need for a comprehensive assessment of the effects of social origin across all relevant transitions between cohorts that completed their education during different phases of the market transition process, which is what this study seeks to provide.

Method

Data

All analyses are based on the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a high-quality, nationally representative survey managed by Peking University. The initial 2010 CFPS sample covered 42,590 individuals in 14,960 households, covering 25 provinces or regions in mainland China. These individuals, and their descendants, have been re-interviewed biennially, with the most recent round of data collection taking place in 2018. Importantly, the CFPS sampling frame includes household members who temporarily live elsewhere, such as students or labour migrants (for more information on sampling procedures and representativeness, see Xie et al., Citation2017).

The CFPS provides detailed measures of respondents’ educational attainment, as well as other basic demographic characteristics. Moreover, the 2012 round contains detailed retrospective measures of social origin, including parental education level, occupation, and Party membership when the respondent was 14 years old.

This study covers individuals born between 1960 and 1994 (aged between 24 and 58 in 2018). Whereas most people born before 1960 would have completed their educational career when the market reforms started, those born after 1994 might still be in (higher) education by the time of the most recent survey. The analytical sample contains 20,513 individuals. Some of the covariates contained missing or unknown values, notably hukou origin (2.0%), parents’ educational attainment (3.3%), and parents’ party membership (2.2%), which were treated as a separate category in the analyses.

Measures

provides descriptive statistics for each of the analytical variables, by cohort. The outcome variable, educational attainment of respondents, is measured using a 5-point scale based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED): no degree (1), completed primary school (2), completed Junior High School (JHS) (3), completed Senior High School (SHS) (4), and completed college or higher (5).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the analytical sample, by birth cohort

My first variable of interest is parents’ educational attainment when respondents were aged 14, measured on the same ISCED scale. Parents’ education serves as a proxy for household income and socio-economic status. It also reflects the ‘educational resources’ available in a household, which relate to a supportive home learning environment as well as parental guidance in educational decision-making (Bukodi & Goldthorpe, Citation2013). In the interest of parsimony, I applied the dominance approach instead of assessing the effect for fathers and mothers separately. suggests that parental education increased substantially across cohorts, in line with overall educational expansion.

The second variable of interest is household registration or hukou status when the respondent was 12 years old. Wu (Citation2011) demonstrates a persistently negative effect of rural household registration status on high school transitions as well as on overall years of schooling attained.

In a state-controlled market economy such as China, it is useful to add political capital as a further element of parental background. In reform-era China political connections continue to provide substantial benefits, which may result in educational advantages for children of party members (Andreas, Citation2009; Yang & Chen, Citation2016). I therefore included a dummy variable indicating whether any parent was a Communist Party member when the respondent was 14 years old. In each cohort, between 11 and 22 per cent of respondents had at least one parent that was a Party member ().

Finally, I looked at gender differences in educational opportunity. Chinese families have a long history of differential investment in male and female children, in line with patriarchal and patrilineal Confucian family norms. As in most modernising societies, however, gender gaps in schooling have disappeared or even reversed among the most recent cohorts (Hannum, Citation2005).

Analytical approach: measuring inequality of educational opportunity

The classic tool for analysing inequality of opportunity in education, and particularly its development over time, is the sequential transition model (Mare, Citation1980). Transition models compare the impact of parental background or other ascribed characteristics at each educational transition. In this study, I look at four key transitions: completing primary (1), completing JHS conditional on completing primary (2), completing SHS conditional on completing JHS (3) and obtaining a college degree conditional on completing SHS (4). The sequential transition model is particularly applicable in this case because the Chinese education system is vertically structured, and completing the previous level is a precondition for entering the next. It is therefore possible to deduce each respondent’s educational path by looking at the highest level attained.

I distinguish between seven birth cohorts: 1960–64, 1965–69, 1970–74, 1975–79, 1980–84, 1985–89, and 1990–94. By calculating separate models for each cohort and transition, covariates and intercepts can vary freely between cohorts, reflecting the changing nature of inequality of educational opportunity over time. The resulting odds ratios are independent of educational expansion (e.g. an overall increase in school attendance), and thus reflect the degree of relative educational inequality. Strictly speaking, the odds ratios cannot be compared across cohorts, however, because the comparison could be affected by between-group differences in residual variation (unobserved heterogeneity) (Mood, Citation2010). In addition to the odds ratios, I therefore also present plots of origin-specific conditional transition probabilities. These plots, which are derived from the same sequential logit model, are not affected by this identification problem and provide an easily interpretable picture of cohort trends in educational expansion as well as absolute educational inequality. In combination, these metrics provide a comprehensive picture of cohort change in educational inequality.

Results

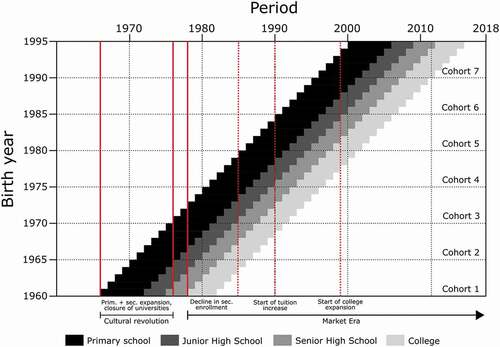

shows at which point in historical time each of the five cohorts identified in this study would have reached the key educational transitions, provided they had followed a ‘regular’ educational career. Their overall levels of educational attainment, and the derived transition rates, are presented in . The overall picture is a substantial contraction for the immediate post-reform cohorts followed by a gradual expansion of access to education. Access to higher education increased particularly rapidly for the youngest cohorts, and reached 54% for those born in 1990–94. also shows substantial attrition at each transition. Especially among the earlier cohorts, the majority of students left the education system before they reached the higher-level transitions.

Figure 1. Historical context of the sampled birth cohorts.

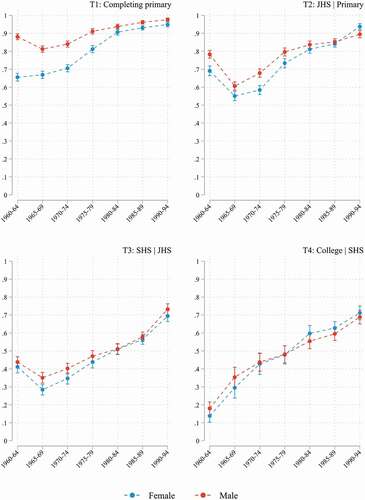

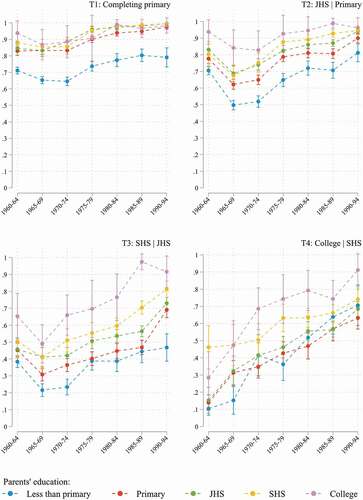

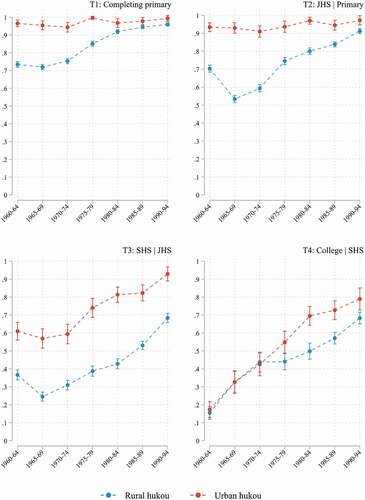

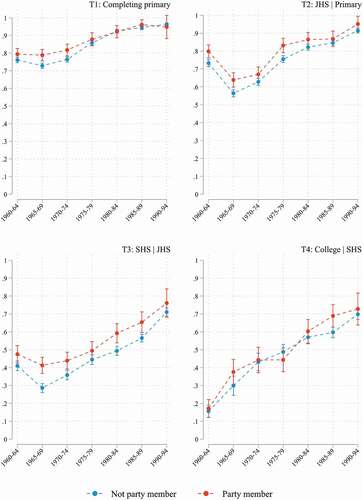

Overall increases in transition rates are likely to mask substantial differences based on social origin and other ascribed characteristics. Results from the sequential logit models are presented as odds ratios () as well as predicted conditional transition probabilities (). Whereas the odds ratios provide a measure of inequality net of educational expansion (relative inequality), differences in the conditional transition probabilities reflect the degree of absolute educational inequality. Cohort trends in conditional transition probabilities are plotted by parental education (), by household registration at age 12 (), and by parents’ party membership ().Footnote1 While a convergence of origin-specific transition probabilities would suggest a reduction in absolute inequality, divergence would suggest the opposite: increasing inequality. Moreover, the plots allow us to observe the degree of educational expansion (which would result in an overall upward trend in the transition probabilities) as well as the cohorts and transitions for which the demand from high status groups has been ‘saturated’.

Table 2. Results from the sequential logit models: odds ratios, by birth cohort

Figure 2. Average conditional transition probabilities, by birth cohort and parents’ education.

Figure 3. Average conditional transition probabilities: by birth cohort and household registration at age 12.

Figure 4. Average conditional transition probabilities: by birth cohort and parents’ party membership.

The first set of findings, using the entire sample as a risk set, relates to obtaining at least a primary school degree. shows that an increasing share of respondents in each birth cohort had completed primary school, although a substantial proportion left school without an elementary degree up to the 1980s and early 1990s, in spite of the mandatory education law introduced in 1986.Footnote2

As primary attainment became nearly universal for younger cohorts, absolute differences in transition rates based on household registration () and parents’ party membership () declined. Relative inequality appeared to increase, however, particularly for children whose parents did not have a primary school degree themselves (see ). The apparently worsening position (in relative terms) of children with uneducated parents is probably due to the increased selectivity of this group. Whereas it constituted 54.9% of the 1960–64 cohort, it made up only 10.3% of the 1990–94 cohort (see ). It is likely that the later cohort is more negatively selected on unobserved characteristics, such as geographic isolation. In other words, when a particular level of education nears universal attendance, the dropouts become an increasingly stratified group (Kröger & Skopek, Citation2017).

The second transition in the Chinese school system is the completion of Junior High School (JHS). shows that 76% of primary school graduates born between 1960 and 1964 went on to complete JHS. The transition rate dropped by 14 percentage points for cohort 2, which would have entered JHS shortly after the start of the market transition, and then continued to increase to 93.5% for the most recent cohort. It is likely that the post-reform contraction relates to the closure of (mostly rural) secondary schools that were set up during the Cultural Revolution, and which mainly catered for students from less advantaged social backgrounds (Andreas, Citation2004; Treiman, Citation2013). This hypothesis is supported by (T2), which shows that completing JHS was virtually universal for urban children of all birth cohorts. The post-transition decline in the transition rate thus only affected rural children, although the rural-urban gap in JHS completion decreased for subsequent cohorts. Attrition at this level is also strongly differentiated by parental education and party membership, whose effects are relatively persistent across birth cohorts (see , as well as ).

Because of its relatively large risk pool and low transition rate, it could be argued that the transition to SHS is the main bottleneck in the Chinese education system (see ). As a result, inequality emerging at this level will have a particularly strong effect on the final distribution of educational outcomes (Buis, Citation2015). (T3), which looks at transition probabilities by parental education, shows a drop in the transition rate for cohort 2, similar to the one observed in the transition to JHS. In this case, however, the subsequent increase in transition rates is accompanied by a divergence of the origin-specific trends, suggesting an increase in (absolute) educational inequality. In the 1960–64 cohort, having parents with a college degree improved the conditional probability of completing SHS by 20 percentage points, compared to having parents with only a primary school degree (65% vs. 45%). In the 1985–89 cohort, this gap had increased to 51 percentage points (98% vs. 47%). The odds ratios presented in confirm this pattern, showing substantial increases in the effect of parental education, net of an overall increase in SHS completion. Stratification by parental education is compounded by rural-urban differences and, to a somewhat smaller extent, differences by party membership. The rural-urban gap in the transition to SHS is particularly striking: it increased from 24 percentage points (37% vs. 61%) in the 1960–65 cohort to 38 percentage points (43% vs. 81%) in the 1980–84 cohort (see ). There may be several reasons for the increasing importance of family background in completing SHS. Being the first (nominally) non-compulsory level of education, senior high schools typically require minimum entrance examination scores and charge tuition fees. Moreover, while tuition fees for compulsory levels of schooling have been gradually abolished, those for SHS (which are often designed as boarding schools) increased substantially in the 1990s, making a senior high school degree almost unaffordable for children from low-income families (Wang et al., Citation2011). For the two youngest cohorts, born between 1985 and 1994, the transition to SHS became almost universal for urban children and the rural-urban gap started to decrease. This is in line with the findings from Wang et al. (Citation2018), who observed a sharp increase in rural high school enrolment between 2005 and 2015.

The final transition (T4) refers to the completion of a college degree, conditional on completing SHS. Entry to higher education, particularly the most prestigious universities, is highly competitive and conveys important social and economic rewards (Wu, Citation2017). With few exceptions (e.g. private colleges or studying abroad), the available options are determined by one’s College Entrance Examination score. Although the progression rate into tertiary education has increased substantially as a result of the 1998 reforms (see ), a substantial number of SHS graduates are still sorted out each year, and many repeat the entrance exam for several years until they obtain the required score (Andreas, Citation2004).

Both the odds ratios () and the predicted probabilities () show that origin-based differences in the transition to higher education are less pronounced in comparison to earlier transitions. Particularly in the first three cohorts, the association between college graduation and hukou, parental education, and parents’ party membership was small and mostly not significant. Does this mean that access to higher education in China is relatively egalitarian? That would be a questionable conclusion, for a number of reasons. First, the risk set for the transition to higher education consists of those that have successfully completed the previous three transitions. Especially for the older cohorts, this group is relatively small (see ) as well as highly socially selected, as we have seen in the previous analyses. If children from less advantaged social origins are sorted out early on in the transition process, higher education institutions no longer ‘need’ to select on the same characteristics to obtain a high-status student body (Shavit et al., Citation2007, p. 47).

Moreover, among the most recent cohorts we can observe an increasing importance of social origin, particularly in the form of a widening rural-urban gap (). The increasing disadvantage of rural students has been well documented elsewhere, and is related to widening disparities in access and quality earlier on in the educational pipeline, particularly at the SHS level (Loyalka et al., Citation2017; Tam & Jiang, Citation2015; Yeung, Citation2013). It is important to remember that most rural students leave the education system before reaching the final transition.

Finally, an important aspect of educational inequality that has not been discussed thus far relates to the role of gender. Gender differences used to be particularly pronounced in the transition to primary school and JHS, but they have narrowed considerably across cohorts (see Appendix ). For the most recent cohort (1980–78) there is virtually no gender gap at any of the lower transitions, and women even hold a slight advantage in the transition to college. This is in line with what has been found in previous studies (e.g. Hannum, Citation2005).

Discussion

The objective of this article was to assess the changing role of social origin in the process of educational attainment in China, with a focus on changes that occurred during the market era (1978-present).

The findings show that the effect family background – particularly hukou origin and parental education – increased during the early reform period, in which overall educational attainment declined. Inequality thereafter followed a pattern of maximally maintained inequality, where inequality decreased at lower-level transitions, but increased at higher levels of attainment. The gains in absolute educational attainment made by the lower socio-economic strata are therefore illusive in comparison, particularly when we consider education to be a positional good. Only for the most recent cohorts, born in the early 1990s, can we observe a narrowing of inequalities, partially because of massive expansion of (vocational) SHS and tertiary education in the early 2000s.

Particularly for children from less privileged social backgrounds, the Chinese school system can be perceived as a hurdle race, in which a high number of participants drop out at each barrier. Inequality was particularly pronounced at the transition from junior to senior high school, where the degree of attrition is highest. Although inequality of opportunity in access to higher education was comparatively less pronounced, the sorting that took place at earlier transitions meant that most disadvantaged students never managed to reach this stage.

The institutionalised discrimination inherent in the household registration system is a unique feature of the Chinese stratification system (Wu & Treiman, Citation2007). While hukou-based differences declined at the transition to primary and JHS, which was virtually universal for urban children, they increased at the transition to SHS and, to a lesser extent, college. Rural Chinese children have to overcome a triple structural disadvantage in the competition for higher educational degrees: attending lower quality schools, they face higher relative costs and less favourable admission criteria than their urban counterparts (Tam & Jiang, Citation2015).

The changes in inequality of educational opportunity are remarkable, particularly when we consider that the cohorts observed in this study span only 35 years. In the comparative literature on educational inequality, which now covers most developed and emerging economies, increases in inequality during educational expansion are an uncommon phenomenon. The only cases in which similar patterns have been observed are post-Soviet Russia (Gerber, Citation2000) and Latin America in the 1980s (Torche, Citation2010). In both cases, increases in inequality were the result of profound economic crises which depressed educational demand and increased the relative cost of schooling. Post-reform China, however, is the only known case in which inequality increased in a context of rapid economic growth and rising living standards. It is therefore unlikely that the observed patterns arise from socio-economic differences in educational demand or expectations. Instead, I suggest that the observed patterns result from a combination of urban- and elite-biased educational reforms, increasing returns to education and massive increases in wider social and economic inequality.

During the Maoist era (1949–1978), income inequality was comparatively low and children from upper class origins were often blocked from progressing through the educational system, as part of a deliberate effort to disrupt the intergenerational reproduction of inequality. These attempts were abandoned with the market transition, and replaced by a system based on achievement selection. Other educational reforms implemented during the market transition period involved the establishment of elite schools and colleges, the decentralisation of education funding, and the introduction of tuition fees. Each of these reforms primarily benefited children of the urban elites, who were best positioned to capitalise on the new opportunities for social advancement provided by educational expansion. Urban, middle class children were more likely to do well in the system of competitive examinations that determines post-reform educational outcomes (Andreas, Citation2004; Hannum et al., Citation2011). Even if their children do not manage to obtain the required grades to enter prestigious key point schools, wealthy parents have the option to send them to expensive private schools or even abroad. For the poorest households, on the other hand, obtaining advanced education became simply unaffordable.

The effect of marketisation in the educational system, which elevated the importance of family resources, was compounded by the surge in income inequality and in returns to education, both of which took place in approximately the same period (Xie & Zhou, Citation2014). Income inequality amplified the disparity in ability to pay for education between different socio-economic strata, placing less fortunate households at an increasing competitive disadvantage. At the same time, increasing returns to education raised the stakes, intensifying the competition for the limited supply of higher educational degrees (Li, Citation2003).

These findings show that educational stratification can increase even during periods of educational expansion. In China, educational policy has helped elites to entrench their advantaged position and strengthened the intergenerational reproduction of inequality. These findings run counter to the government’s ‘Harmonious Society’ agenda, which seeks to equalise opportunities and reduce socio-economic disparities. Both policymakers and opinion leaders have referred to the Confucian ideal of meritocracy to explain and justify high levels of social inequality in contemporary China (Whyte & Im, Citation2014). Although inequalities have begun to decrease among the youngest cohorts, the educational attainment of rural children remains decades behind that of their urban counterparts. Moreover, it has been observed that many of the newly built vocational schools and colleges in rural areas are of low quality (Rozelle & Hell, Citation2020).

The size and representativeness of the CFPS sample ensures that these findings can be generalised to the Chinese population. Nevertheless, a number of limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. First, although the study focused on the association between social origins and educational outcomes, it did not address the mechanisms through which such associations arise. Future research could look at the role of institutional features such as tuition fees and entrance examinations, as well as the discriminatory policies that prevent migrant children from attending urban schools. Moreover, further inequalities may manifest themselves when looking at selection within education levels, for example, between vocational and academic high schools, or between elite universities and less selective colleges. Finally, for reasons mentioned earlier, it is difficult to link changes in educational inequality across cohorts to period-specific educational policies. It is possible, for example, that earlier cohorts benefited from the 1998 college expansion by entering college at a later stage in life.

These limitations notwithstanding, the study contributes to our understanding of educational inequality in several ways. Empirically, it documents trends in educational stratification during China’s ‘Great Transformation’, providing robust evidence of substantial increases in inequality of opportunity, particularly at the crucial transition to senior high school. Theoretically, it shows that the trends follow the pattern of maximally maintained inequality, which has previously been observed in several Western contexts. Methodologically, it highlights the importance of looking at absolute as well as relative levels of inequality in interpreting the findings from educational transition models.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank John Ermisch, Tak Wing Chan, the members of the Center for Social Research (CSR) at Peking University, as well as the participants in the Nuffield College Postdoc Seminar and the Sociology Reading Group at the University of Oxford for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rob J. Gruijters

Rob Gruijters is a lecturer in education and international development at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, where he is affiliated with the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre. His current research focuses on social stratification, educational inequality, and school effectiveness in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. His recent work has been published in Sociology of Education, the Journal of Marriage and Family, the Comparative Education Review, and the European Sociological Review.

Notes

1. Trends by gender are presented in the Appendix Figure A1.

2. This is in line with official statistics, which show that primary school enrolment only reached nearly universal levels by the end of the 20th century (Treiman, Citation2013). It is important to note that many of those without a primary school certificate have completed at least a few years of schooling.

References

- Andreas, J. (2004). Leveling the Little Pagoda: The impact of college examinations, and their elimination, on rural education in China. Comparative Education Review, 48(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/379840

- Andreas, J. (2009). Rise of the red engineers: The cultural revolution and the origins of China’s new class. Stanford University Press.

- Bian, Y., & Logan, J. R. (1996). Market transition and the persistence of power: The changing stratification system in Urban China. American Sociological Review, 61(5), 739–758. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2096451

- Blossfeld, P. N., Blossfeld, G. J., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2015). Educational expansion and inequalities in educational opportunity: Long-term changes for East and West Germany. European Sociological Review, 31(2), 144–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv017

- Buis, M. L. (2017). Not all transitions are equal: The relationship between effects on passing steps in a sequential process and effects on the final outcome. Sociological Methods & Research, 46(3), 649-680. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124115591014

- Bukodi, E., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2013). Decomposing “social origins”: The effects of parents’ class, status, and education on the educational attainment of their children. European Sociological Review, 29(5), 1024–1039. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs079

- Deng, Z., & Treiman, D. J. (1997). The impact of the cultural revolution on trends in educational attainment in the people’s republic of China. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 391–428. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/231212

- Gamoran, A. (2001). American schooling and educational inequality: A forecast for the 21st Century. Sociology of Education, 74(2001), 135–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2673258

- Gerber, T. P. (2000). Educational stratification in contemporary Russia: Stability and change in the face of economic and institutional crisis. Sociology of Education, 73(4), 219–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2673232

- Gruijters, R. J., Chan, T. W., & Ermisch, J. (2019). Trends in educational mobility: How does China compare to Europe and the United States? Chinese Journal of Sociology, 5(2), 214–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X19835145

- Hannum, E. C. (2005). Market transition, educational disparities, and family strategies in rural China: New evidence on gender stratification and development. Demography, 42(2), 275–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2005.0014

- Hannum, E. C., An, X., & Cherng, H.-Y. S. (2011). Examinations and educational opportunity in China: Mobility and bottlenecks for the rural poor. Oxford Review of Education, 37(2), 267–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2011.559387

- Hannum, E. C., Park, A., & Cheng, K. (2007). Introduction: Market reforms and educational opportunity in China. Emily Hannum & Albert Park, (eds). Education and reform in China.Routledge. (pp. 1–23). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203960950

- Hannum, E. C., & Wang, M. (2006). Geography and educational inequality in China. China Economic Review, 17(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2006.04.003

- Jackson, M., & Evans, G. (2017). Rebuilding walls: Market transition and social mobility in the post-socialist societies of Europe. Sociological Science, 4, 54–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15195/v4.a3

- Kröger, H., & Skopek, J. (2017, April). Logistic confusion - an extended treatment on cross-group comparability of findings obtained from logistic regression. Working Paper, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28652.16006

- Lai, F., Liu, C., Luo, R., Zhang, L., Ma, X., Bai, Y., & Rozelle, S. (2014). The education of China’s migrant children: The missing link in China’s education system. International Journal of Educational Development, 37, 68–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2013.11.006

- Li, H. (2003). Economic transition and returns to education in China. Economics of Education Review, 22(3), 317–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(02)00056-0

- Liu, A., & Xie, Y. (2015). Influences of monetary and non-monetary family resources on children’s development in verbal ability in China. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 40, 59–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2015.02.003

- Loyalka, P., Chu, J., Wei, J., Johnson, N., & Reniker, J. (2017). Inequalities in the pathway to college in China: When do students from poor areas fall behind? The China Quarterly, 229, 172–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741016001594

- Mare, R. D. (1980). Social background and school continuation decisions. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 75(370), 295–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1980.10477466

- Mood, C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp006

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2015). China Statistical Yearbook 2015. China Statistics Press.http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2015/indexeh.htm

- Nee, V. (1989). A theory of market transition: From redistribution to markets in state socialism. American Sociological Review, 54(5), 663–681. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2117747

- Pepper, S. (1996). Radicalism and education reform in twentieth-century China: The search for an ideal development model. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/369893

- Raftery, A. E., & Hout, M. (1993). Maximally maintained inequality: Expansion, reform and opportunity in Irish education, 1921–75. Sociology of Education, 66(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2112784

- Rosen, S. (1985). Recentralization, decentralization, and rationalization: Deng xiaoping’s bifurcated educational policy. Modern China, 11(3), 301–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/009770048501100302

- Rozelle, S., & Hell, N. (2020). Invisible China: How the urban-rural divide threatens China’s rise. University of Chicago Press.

- Shavit, Y., Yaish, M., & Bar-Haim, E. (2007). The persistence of persistent inequality. In S. Scherer, R. Pollak, G. Otte, & M. Gangl (Eds.), From origin to destination: Trends and mechanisms in social stratification research (pp. 37–57). Campus Verlag.

- Tam, T., & Jiang, J. (2015). Divergent urban-rural trends in college attendance: State policy bias and structural exclusion in China. Sociology of Education, 88(2), 160–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040715574779

- Torche, F. (2010). Economic crisis and inequality of educational opportunity in latin America. Sociology of Education, 83(2), 85–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040710367935

- Treiman, D. J. (2013). Trends in educational attainment in China. Chinese Sociological Review, 45(3), 3–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA2162-0555450301

- Tsang, M. C. (2000). Education and national development in China since 1949: Oscillating policies and enduring dilemmas. China Review (pp. 579–618).

- Wang, L., Li, M., Abbey, C., & Rozelle, S. (2018). Human capital and the middle income trap: How many of China’s youth are going to high school? Developing Economies, 56(2), 82–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/deve.12165

- Wang, X., Liu, C., Zhang, L., Luo, R., Glauben, T., Shi, Y., … Sharbono, B. (2011). College education and the poor in China: Documenting the hurdles to educational attainment and college matriculation. Asia Pacific Education Review, 12(4), 533–546. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-011-9155-z

- Whyte, M. K., & Im, D. K. (2014). Is the social volcano still dormant? Trends in Chinese attitudes toward inequality. Social Science Research, 48, 62–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.05.008

- Wu, X. (2010). Economic transition, school expansion and educational inequality in China, 1990 – 2000. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 28(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2009.12.003

- Wu, X. (2011). The household registration system and rural-urban educational inequality in contemporary China. Chinese Sociological Review, 44(2), 31–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA2162-0555440202

- Wu, X. (2017). Higher education, elite formation and social stratification in contemporary China: Preliminary findings from the Beijing college students panel survey. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 3(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X16688144

- Wu, X., & Treiman, D. J. (2004). The household registration system and social stratification in China: 1955–1996. Demography, 41(2), 363–384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2004.0010

- Wu, X., & Treiman, D. J. (2007). Inequality and equality under Chinese socialism: The huko system and intergenerational occupational mobility. American Journal of Sociology, 113(2), 415–445. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/518905

- Xie, Y., Zhang, X., Tu, P., Ren, Q., Sun, Y., Lv, P., Wu, Q. (2017). China family panel studies user’s manual (3rd.). China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/docs/20180928161838082277.pdf

- Xie, Y., & Zhou, X. (2014). Income inequality in today’s China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(19), 6928–6933. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1403158111

- Yang, W., & Chen, L. (2016). Political capital and intergenerational mobility: Evidence from elite college admissions in China. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 2(2), 194–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X16641046

- Ye, H. (2015). Key-point schools and entry into tertiary education in China. Chinese Sociological Review, 47(2), 128–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2014.990321

- Yeung, W. J. (2013). Higher education expansion and social stratification in China. Chinese Sociological Review, 45(4), 54–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA2162-0555450403

- Zhou, X., Moen, P., & Tuma, N. B. (1998). Educational stratification in Urban China: 1949–94. Sociology of Education, 71(3), 199–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2673202