?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Academic writing is a complex competence in higher education. To develop this competence, teachers’ written feedback is vital, especially if it contains feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information. However, academic writing does not always improve after provision of written feedback. The purpose of this study was to explore if peer-to-peer dialogue between students about teachers’ written feedback does enhance students’ understanding of written feedback. Sixty-three second-year university students participated in a pre-test-post-test design with mixed methods. Questionnaire data showed that peer-to-peer dialogue increased students’ understanding of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information. Focus group data demonstrated that the dialogue helped students to understand the assessment criteria better (feed up) and offered suggestions for improvement (feed forward). High quality teachers’ written feedback was perceived as an important condition. Peer-to-peer dialogue among students about teachers’ written feedback seems promising in enhancing students’ understanding on how to improve their academic writing assignments.

Introduction

In the academic setting of higher education, students need to become competent in academic writing. Both teachers and students consider written feedback essential in the process of developing this competence (Adcroft Citation2011; Carless Citation2006; Weaver Citation2006; Winder, Kathpalia, and Ling Koo Citation2016). However, academic writing does not automatically improve after providing written feedback (Burke and Pieterick Citation2010; Crisp Citation2007; Higgins, Hartley, and Skelton Citation2001; Rae and Cochrane Citation2008; Weaver Citation2006). Students do not always understand the feedback that is given to them (Adcroft Citation2011; Chanock Citation2000; Glover and Brown Citation2006; Higgins, Hartley, and Skelton Citation2001; Williams Citation2005).

Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007) concluded in their review on feedback that, although feedback in a broad sense is one of the most powerful influences on learning and achievement, other factors mediate its effectiveness. To improve effectiveness of feedback, they proposed a model of feedback, which contains three questions that effective feedback should provide answers to: “Where am I going?”, “How am I doing?” and “Where to next?” (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007, 87). These questions were categorised as “feed up”, “feed back”, and “feed forward”, respectively. While feed up provides the learner with information about the goals and assessment criteria of the assignment, feed back gives details about the discrepancy between the intended and actual performance; finally, feed forward explains to the learner how to move to the next step or which strategies to choose to improve. Van den Berg et al. (Citation2006, 135) earlier suggested that “written feedback is adequate if this written feedback is orally explained and discussed with the receiver”. Black and Wiliam (Citation2009) emphasised the importance of interactions among the student, the peers and the teacher. The theory they proposed assigns specific teaching and learning roles to the student, the peers and the teacher. Since peers use a language that is well understood by fellow students, they can make a valuable contribution to the feedback process. Moreover, they are cognitively and socially more congruent with fellow students than with teachers (Bloxham and West Citation2004; Schuitema et al. Citation2018). Peer feedback is also known to enhance students’ sense of belonging to the group, which can motivate students to learn from each other (Bloxham and West Citation2007). Hence, peer-to-peer dialogue about written feedback could be a viable way to improve the effectiveness of feedback (Duijnhouwer, Prins, and Stokking Citation2012). This dialogue is assumed to contribute towards a better understanding of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information provided by teachers’ written feedback, and could enhance students’ reflection on feedback (Duijnhouwer, Prins, and Stokking Citation2012; Van der Schaaf et al. Citation2013).

Previous studies investigating effective feedback dialogues in academic writing highlighted the importance of providing learners with criteria, worked-examples, training, and opportunities to revise drafts (Cartney Citation2010; Connor and Asenavage Citation1994; Hedgcock and Lefkowitz Citation1992; Hendry, Armstrong, and Bromberger Citation2012; Liu and Sadler Citation2003; Yucel et al. Citation2014). Overall, students perceived these interventions to be beneficial for their learning, but not all studies demonstrated positive findings and academic writing did not always improve after these interventions (Connor and Asenavage Citation1994; Yucel et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, only a limited number of studies explicitly investigated the effectiveness of dialogue (Krych-Appelbaum and Musial Citation2007; Van der Schaaf et al. Citation2013) and so far no study has been conducted to investigate how peer-to-peer dialogue among students could enhance a better understanding of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information in teachers’ written feedback.

This study adds to previous studies in this field by investigating the effects of peer-to-peer dialogue on students’ understanding of teachers’ written feedback in terms of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information. Additionally, this study will explore how and under which conditions, from the students’ perspective, peer-to-peer dialogue contributes to improved understanding of the teachers’ written feedback. This leads to the following research questions:

To which extent does peer-to-peer dialogue about teachers’ written feedback enhance students’ understanding of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information?

How and under which conditions does peer-to-peer dialogue about teachers’ written feedback enhance students’ understanding of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information?

Method

A mixed-methods sequential explanatory design was used. In such a design, a quantitative study is followed by a qualitative study to account for the quantitative results (Creswell Citation2012). Moreover, a pre-test-post-test approach with questionnaires was adopted to investigate a possible improved understanding of teachers’ written feedback in students after peer-to-peer dialogue.

Participants

Sixty-three second-year students of a bachelor’s programme with parallel tracks in Biomedical Sciences at Maastricht University participated. The bachelor programme has a Problem-Based Learning curriculum. In such a curriculum, students are used providing each other with feedback and discussing in small groups (Moust, van Berkel, and Schmidt Citation2005). Students took either the first two courses of the Biological Health Sciences (BHS) track (courses 1 and 2) or the first two courses of the Human Movement Sciences (HMS) track (courses 3 and 4). The number of students per course varied between 23 and 35 (see ). Four teachers were involved in this study as assessors, each of them being responsible for the written feedback for all individual students within one course. The participating teachers did attend the so-called University Teaching Qualification programme. The aim of the programme is to support teaching staff to improve their teaching competencies which relate to the delivery of teaching, such as activating students, providing feedback, the design of course materials, and assessment. For this study that means the involved teachers were trained in how to provide students with feedback.

Table 1. Summary of number of participants and subject of the writing assignment per course

Intervention

To ensure high quality feedback provision, the participating teachers attended an additional one-hour fine-tune session on how to provide students with written feedback. They were also instructed about the importance of providing feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information to the students in their written peer feedback. They provided narrative written feedback (via Track Changes mode in MS Word) that was based on the assessment criteria of the specific writing assignment. The written feedback and a provisional grade were included in the student’s report. The grade was on a 1–10 scale, less than 6 being insufficient (fail) and 10 being excellent (pass). For each course, students were required to participate in an oral “peer-to-peer dialogue” about teachers’ written feedback in groups of 2 to 4 students, without the presence of the feedback-providing teacher. Students with different performance levels, as indicated by the grades received on the draft report, were allocated to a certain dialogue group. The dialogue was conducted according to the 4-step model of Sargeant et al. (Citation2011). In step one of this model, the teacher provided written feedback as described above which included feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information as defined by Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007). Students were instructed before the peer-to-peer dialogue session to read the feedback provided by the teacher on their own assignment and on the assignments of their peer students in the group. Students received no training in advance. At the start of the dialogue session students were instructed to follow the three subsequent steps of Sargeant et al.’s (Citation2011) model by the principal researcher of this study. In step two, the first part of the dialogue session, the facilitator, being an expert in leading focus groups, explored students’ initial reactions regarding the written feedback by asking about their first impression of this written feedback. In step three, students discussed the content of their teachers’ written feedback with each other. In step four, students offered each other additional guidance on how to proceed or move forward. No moderator was available to facilitate the peer-to-peer dialogue in the small groups, but the principal researcher was available if needed.

Procedure

The procedure within a course spanned several consecutive phases:

First, students attended a biomedical practical training session which they concluded by writing an individual scientific report as a writing assignment. Both the practical training session and the writing assignment were part of the 8-week course. The length of the reports was 4–6 pages and the report made up 25% of the final course grade. Assessment criteria for each report were available to students.

Students prepared for the peer-to-peer dialogue by reading the reports and the accompanying teacher remarks of two or three peers. These assignments of fellow students served as worked-examples. In a subsequent meeting, the facilitator first explained the structure of the session in plenary and students filled out the pre-test questionnaires. Before starting the actual feedback dialogue, the facilitator explored students’ reactions to the received written feedback (step 2 of Sargeant’s model).

For approximately 45 minutes, in groups of 2 to 4, students discussed the content of the written feedback (step 3 of Sargeant’s model) and they discussed possible strategies to improve the report (feed forward or step 4 of Sargeant’s model).

The meeting ended in a plenary session, where students had the opportunity to ask remaining questions. Additionally, the post-test questionnaire was filled out.

In the last phase of the procedure, students individually revised the report as part of the completion of the writing assignment. Revision of the draft report was mandatory to receive a final grade. This procedure is standard in the series of communication skills courses in the Biomedical Bachelor programme. Students had a week for revision and resubmission of the final report. In cases of no resubmission or insufficient revision after receiving feedback, the grade would be a 5 (a fail); for that matter, even a preliminary pass grade could become worse. Students who had a fail grade before revision could obtain a maximum pass grade of 6 after sufficient revision of the report, whereas students who already had a pass grade (for example 6, 7, 8 or 9) obtained their initial grade after revision as their final grade. In case this grade was a fail, the student was allowed a resit.

Focus groups took place after completion of the second assignment.

All participants gave their written informed consent. The Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO, number 344) approved the study.

Instruments

Questionnaires

Students’ perceptions of the quality of both the written feedback in terms of feed up, feed back and feed forward and the feedback dialogue were measured using an adjusted version of a validated questionnaire by De Kleijn et al. (Citation2014). The questionnaire contained 16 items of which one item targeted the overall quality of teachers’ written feedback on a ten-point scale, ranging from 1 to 10. The remaining 15 items were distributed among three subscales, specifically “feed up” (four items), “feed back” (six items) and “feed forward” (five items), and rated on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (fully disagree) to 5 (fully agree). An example of a feed-up item is: “By means of the written feedback it is clear what the assessment criteria of a scientific report are”. An example of a feed-back item is: “The written feedback indicates what I do wrong” and an example of a feed-forward item is: “The written feedback indicates how I can improve my report”. The questionnaire that was administered before and after the intervention comprised similar items. In the post-test questionnaire, a few items were added to measure how students perceived the quality of the feedback dialogue. A reliability analysis of the feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward subscales within pre- and post-test questionnaires yielded acceptable reliability coefficients ranging from 0.79 to 0.91 (Peterson Citation1994). Preliminary pilot-tests were conducted to determine item clarity and adjustments were made to unclear items. Additionally, the logistics of the intervention were tested during the pilot-test.

Focus groups

To provide more in-depth data focus groups were conducted (Stalmeijer, McNaughton, and Van Mook Citation2014). At the end of the last feedback dialogue session of both tracks, each student was invited for a focus group session. Eventually, two focus groups comprised six students and lasted approximately one hour. The third focus group contained 12 students; it was a combined group of two times six students, because we unfortunately scheduled the meetings at the same time. To ensure each student’s voice to be heard, this focus group continued for one and a half hour. Each focus group was guided by a moderator (fourth author) and was observed by one member of the research team. In semi-structured interviews, the actual topics discussed in the focus groups covered student experiences regarding the content of the written teacher feedback as well as the added value of the peer-to-peer dialogue about this written feedback. The interviews were audiotaped.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis

First, means and standard deviations of the continuous variables, overall instructiveness of written feedback and overall instructiveness of feedback dialogue, were calculated. To test an expected improved instructiveness, one-sided paired t-tests were performed on a 5% significance level to compare the pre- and post-test scores. This was done for the total data set (N = 114) and for the four courses separately.

Secondly, to provide a more detailed view, the median and interquartile range (25% and 75%) of perceived instructiveness of written feedback (pre-test) and perceived instructiveness of feedback dialogue (post-test) for the subscales of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information were computed. This again was done for the total data set and per course. One-sided differences between pre- and post-test results were tested with the Wilcoxon-signed-rank test on a 5% significance level.

Qualitative analysis

Focus group sessions were transcribed verbatim and read independently by the first and fourth authors. In the first round of the qualitative analysis, both authors individually and manually assigned themes and subthemes relevant to the research question on how and under which conditions peer-to-peer feedback dialogue is instructive. To improve the credibility and transferability of the data, both authors compared the themes and discussed differences until they reached consensus. Next, the principal author selected quotes that were representative of the themes that had emerged, after which all authors discussed these themes and selected quotes until they were all in agreement.

Results

All students (N = 63) who submitted the writing assignment participated in this study, resulting in a response rate of 100%.

Quantitative results

The overall perceived instructiveness of the teachers’ written feedback was statistically significantly higher after the peer-to-peer dialogue session as compared to the perceived instructiveness before the dialogue (resp. 7.20.9 and 6.9

1.3; t(113) = −2.27, p < .001; ). These findings differed per course: the scores in courses 1 and 4 improved significantly, while the score in course 3 did improve after the dialogue, but not statistically significantly. On the contrary, in course 2 the scores decreased after the intervention as shown in .

Table 2. Students’ mean ratings (scale 1–10) of the overall perceived instructiveness of the written feedback (pre-test) and the perceived understanding of the written feedback after the peer-to-peer feedback dialogue (post-test), overall and per course

Regarding the subscales of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information, students scored the overall instructiveness after the dialogue significantly higher as compared to the pre-test scores. A Wilcoxon-signed-rank test indicated that the median post-test scores for feed-up information, Mdn = 4.0, were statistically significantly higher than the median pre-test scores, Mdn = 3.5, Z= −5.08, p < 0.001. The same held for feed-back information (Mdn = 3.5 compared to Mdn = 3.2, Z = −5.16, p < .001) and for feed-forward information (Mdn = 4.0 compared to Mdn = 3.6, Z = −6.25, p< .001). The findings per course were similar: all courses showed an increase in scores after the peer-to-peer dialogue, except for the post-test scores related to feed-up and feed-back information in course 3, which did not differ significantly (see ).

Table 3. Students’ median pre- and post-test ratings (Likert scale, 1–5) of the instructiveness of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information, overall (N= 114) and for each course separately

Qualitative findings

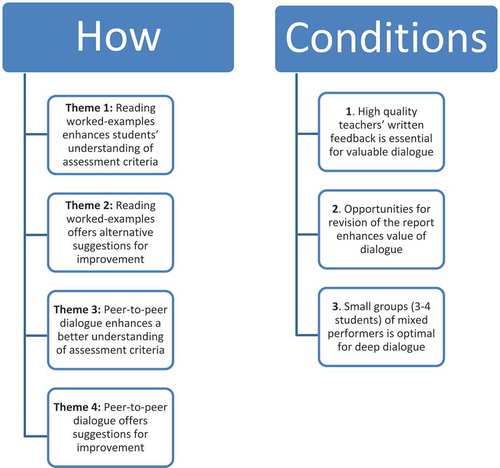

The focus group sessions resulted in four themes, specifying how peer-to-peer dialogue enhanced understanding of feed up, feed back and feed forward. Also, three major conditions that influenced the peer-to-peer dialogue could be distinguished (see ).

Figure 1. Main findings of qualitative analysis on how and under which conditions the dialogue intervention enhances learning in students

The first two themes focus on students’ reading of the worked-examples, while themes 3 and 4 are directed on the peer-to-peer dialogue.

Theme 1: Reading worked-examples enhanced students’ understanding of the assessment criteria.

The assessment criteria regarding writing aspects were the same for each assignment and were given prior to writing the assignment. Each course made use of these assessment criteria but also defined some additional assignment-specific criteria developed by the teachers. By reading the reports of peers and the accompanying written feedback of teachers, students experienced a better understanding of what the teacher meant. Furthermore, the assessment criteria became clearer by reading how fellow students applied the criteria and by comparing the written feedback provided to the students in the group.

… .I could more or less reconstruct the assessment criteria based on three reports by contemplating: that one has received a good assessment here and that has received a good assessment there (FG1, student 1).

Theme 2: Reading worked-examples offered alternative suggestions for improvement.

The normal procedure for the writing assignment is that students work independently on a writing assignment and they individually hand in their report. Students in the focus groups revealed they seldom work together or ask each other for help or feedback on how to write a report. The opportunity to examine and compare peer reports including teachers’ written remarks enhanced the creation of alternative ideas for writing and improving one’s own report.

I need to say that it was beneficial for me, just comparing different kinds of feedback: one person did this well, the other did that well and, yes, you can look at other reports: yes, how exactly did that person do that? (FG1, student 2).

Theme 3: Peer-to-peer dialogue enhanced a better understanding of the assessment criteria.

The peer-to-peer dialogue also improved students’ understanding. During this dialogue, students not only had the opportunity to ask peers for clarifications about teachers’ written feedback, but could also explain teachers’ written feedback to each other. This conversation was beneficial since it helped them to gain a better understanding of the assessment criteria. Through discussion, students came to learn their peers’ different interpretations of and perspectives on their teachers’ written remarks:

Yes, other people interpreted the feedback differently than I did. So, I got to hear different opinions and then I finally understood it (FG1, student 3).

Theme 4: Peer-to-peer dialogue offered suggestions for improvement.

During the dialogue students helped their peers with what to improve in the report and how to do it. Students provided each other suggestions for improvement and they exchanged tips and strategies to do so.

… .I got advice like: ‘You can do this or that better’, which allowed me to revise my report in a much better way (FG2, student 1).

Low achieving students were especially likely to benefit from the explanations and suggestions for improvement by their high-achieving peers during the dialogue.

… I screwed up my own report … .and there was someone in the group who had a higher grade and that person then explained several issues during the discussion … this helped me to improve my report (FG2, student 2).

The focus groups revealed three major conditions that influenced the understanding of feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information during the dialogue: the quality of teachers’ written feedback, the mandatory revision of the report and the level of students’ performance (see ).

Condition 1: Quality of teachers’ written feedback is essential: it should contain feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information.

A first condition for the level of instructiveness of the peer-to-peer dialogue was the quality of teachers’ written feedback. Although the students in the focus groups generally appreciated their teachers’ written feedback, they also perceived great variation in the quality of this feedback. The written feedback was of less quality and thus less useful if, for instance, the teacher just jotted down a question mark or added “reformulate” or “I do not understand this” or “no” to a large amount of selected text. On the other hand, good-quality feedback was included in a specific location in the report, clearly formulated, understandable and useful. Written feedback was perceived as useful if this was explicit enough, stimulated further thinking in students and provided feed-up, feed-back and feed-forward information. Under these circumstances, the peer-to-peer feedback dialogue was perceived to be instructive, because it enhanced students’ understanding about academic writing:

Well, the teacher often selects a certain word or sentence which does not make sense and makes the remark: ‘Is this scientific language?’ Then I started thinking by myself … what is not correct? … I know it is not correct … . And if I thought for a while I also thought … . Yes, it is not scientific, it should be different … (FG3, student 1).

Condition 2: Opportunities for revision of the report enhanced the added value of the peer-to-peer dialogue.

A second condition is the mandatory revision and final grading of the report. Students acknowledged that the obligatory revision motivated them to take the feedback more seriously, to reflect upon it more critically and hence to be more involved. Through revision, it became relevant for students to act upon the written feedback. Two students phrased it as follows:

In my case, when I had a sufficient grade last year, I did not even bother to open the report with the feedback and I just believed it all. Now you really need to read it … (FG2, student 3).

Yes, and now I think critically about it once more and I have to revise it, even if I got a sufficient grade. That makes me think more like: ‘Oh yes, this is actually wrong’. Even if I got a sufficient grade, it can be done even better (FG3, student 2).

Condition 3: Small group discussions with 3–4 students with a mixed level of performance were perceived optimal for a deep dialogue.

A third contributing condition was the group arrangement of the feedback dialogue with respect to group size and students’ level of performance. Students in the focus groups preferred a group size of 3–4 students, as it provided a sufficient number of worked-examples and at the same time allowed sufficient time to read each other’s reports and accompanying teachers’ written feedback in preparation for the feedback dialogue session. With this group size, each student also had the opportunity to ask his/her own questions during the dialogue session.

With regard to students’ level of performance, low- and high-achieving students held different views. Low-achieving students preferred mixed groups, because of the examples and explanations they received from high-achieving students. Hence, the intervention was especially beneficial for this group. Several high-achieving students, on the other hand, felt they were being exploited by low-achieving students and felt they gained too little in return, because, for example, their specific questions could not be answered. Some high-achieving students would have appreciated the presence of the feedback-providing teacher. One high-achieving student pointed out:

I think, if I have a lower grade, then it is useful, but if I have a nine [out of ten], then it is actually a waste of time for me. Yes, I can explain it to others, but there is nothing in it for myself (FG2, student 4).

Discussion

The main conclusion from the quantitative results was that from the students’ perspective peer-to-peer dialogue seems to enhance students’ understanding of feed-up, feed-back as well as feed-forward information provided by the teachers’ written feedback. The qualitative findings further revealed that students not only learned from reading the worked-examples of the assignments and teachers’ feedback, but also from the dialogue with other students, which enhanced their understanding of the assessment criteria and provided them with suggestions for improvement. This learning process takes place under the condition that 1) the written feedback provided by the teacher is clear and consistent, 2) students are offered opportunities to revise their assignment and 3) the dialogue is performed in small groups of students of different levels of performance. Based on the findings of this study we conclude that, from the students’ perspective, peer-to-peer dialogue among students about teachers’ written feedback on academic writing assignments does enhance students’ understanding of how to improve. .

This conclusion is in line with previous studies, which demonstrate that dialogue interventions improve understanding and help students to move forward (Hendry, Bromberger, and Armstrong Citation2011; Reese-Durham Citation2005; Yucel et al. Citation2014). This study adds to our understanding that peer-to-peer dialogue based on worked-examples and teachers’ written feedback is perceived by students to contribute to a better understanding of the assessment criteria and offers suggestions and solutions for improvement of the academic writing assignment. Moreover, this study reveals conditions that support this learning process. These findings are consistent with earlier studies, which also demonstrated that high quality of written feedback is crucial (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick Citation2006), that providing revisions is helpful (Jonsson Citation2012; Weaver Citation2006) as well as mixing students of different performance levels is beneficial for learning (Tsui and Ng Citation2000; Yucel et al. Citation2014). Nevertheless, these earlier studies did not provide specific insight into the role of peer-to-peer dialogue and the enhanced understanding of feed-up and feed-forward information.

The theoretical implications of the findings concerning the conditions on the dialogue are now further discussed. Regarding the first condition, the quality of written feedback, the overall perceived instructiveness of the teachers’ written feedback did show a significant increase after the subsequent peer-to-peer dialogue; however, there were differences among the courses. In course 2, the overall perceived instructiveness score showed a decrease after the intervention (see ), although the distinct scores related to feed up, feed back and feed forward did show an increase in . Moreover, these separate scores were relatively high before the dialogue took place (pre-test) as compared to the pre-test scores for the other courses in . A possible explanation might be that the written feedback provided by the teacher was of such a high quality that the peer-to-peer dialogue did not add that much, as was explained by students in the respective focus groups. The course 3 results did show an increased instructiveness, however this was not significant. A possible explanation might again be that the quality of the written feedback provided by the teacher was already rated as sufficient and the dialogue did not add that much.

A second condition that influenced the peer-to-peer dialogue was the obligatory revision and submission for end-term assessment of the report. Students perceived this obligation as an important factor for the instructiveness of peer-to-peer dialogue. The need to revise the report requires students to understand teachers’ written feedback and motivates them to participate constructively in peer-to-peer dialogue. This finding is consistent with other research (Jonsson Citation2012; Weaver Citation2006). However, the qualitative findings of this study show that not every student, for example a higher achieving student, is motivated to participate in the dialogue.

As to the third condition, the performance level of the students in the dialogue groups, high-achieving students experienced little immediate gain by dialogue. As a result, several high-achieving students were less motivated during the peer-to-peer feedback dialogue. However, other high-achieving students did value the feedback dialogue, as they acknowledged that their role of high- or low-achiever could shift from one writing assignment to another: being a high- or medium achiever during one assignment to being a low-achiever during another assignment. Overall, low- as well as high-achieving students in this study perceived the use of mixed groups in the peer-to-peer dialogue intervention to be stimulating their peer learning. This finding is similar to other research on this topic (Tsui and Ng Citation2000; Yucel et al. Citation2014).

The implications of the findings of the present study for educational practice in higher education are threefold. Firstly, peer-to-peer dialogue does seem to enhance students’ understanding, especially if written teacher feedback is not of high quality. Secondly, for an optimal instructiveness of the peer-to-peer dialogue within academic writing courses, opportunities for revision of the report are strongly advised. Thirdly, the use of mixed groups with students of different performance levels for the peer-to-peer dialogue is recommended. For that matter, teachers need to ensure that high-achieving students are also motivated to participate in the dialogue. One way to motivate even high-achieving students could be to engage students in providing peer feedback. Fourthly, to fully benefit from peer-to-peer dialogues it is suggested to also ensure high quality of teacher feedback. For example, by organizing peer group reflections among teachers on how to facilitate peer feedback and provide student with high quality written feedback on academic writing assignments.

Although this study provided rich insights into how and under which conditions peer-to-peer dialogue about teachers’ written feedback enhanced students’ understanding of this feedback in order to improve their academic writing assignments, this study has three major limitations. First of all, the quality of written teacher feedback was measured by means of student perceptions only. Although the participating teachers were experienced, and their feedback was assumed to be of a certain quality level, explicit analysis of their written feedback was not performed. A second limitation concerns the quality of the peer-to-peer dialogue, which was also measured via student perceptions only. Although student perceptions are important data, the explicit content of the dialogue was not determined in this study. A final limitation of this study relates to the quality of the academic writing products, which were not measured end-term. It is therefore not clear if students’ writing skills indeed improved after the intervention.

For future research, it is recommended that the quality of teachers’ written feedback be measured, for example by an independent evaluator. In addition, it would be worthwhile to observe and analyse the peer-to-peer dialogue to determine its quality. To monitor the development of students’ writing skills it is suggested that the writing products be evaluated mid-term as well as end-term by an independent assessor. Finally, further research needs to investigate the effects of peer-to-peer dialogue in a two group pre-test-post-test design setting.

The final conclusion of this study is that, from the students’ perspective, peer-to-peer dialogue among students about teachers’ written feedback on academic writing assignments does enhance students’ understanding of how to improve. The quality of teachers’ written feedback was perceived to be an important condition for the instructiveness of the dialogue. To help students to deal with teachers’ written feedback in order to enhance academic writing skills, peer-to-peer feedback dialogue could offer a viable way to achieve this, especially in low-achieving students.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating students and staff from the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences for their contribution in this study. Furthermore, we thank Angelique van den Heuvel and Neill Wylie for editing this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marlies Schillings

Marlies Schillings is a lecturer at Maastricht University. She is currently undertaking a PhD in the School of Health Professions Education at Maastricht University, The Netherlands. Her educational and research interests involve writing curricula in the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences.

H. Roebertsen

H. Roebertsen is a senior lecturer and educational adviser at Maastricht University, in the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences.

H. Savelberg

H. Savelberg is a professor of evolving academic education at Maastricht University. Furthermore, he is director of Education for Biomedical Sciences in the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences at Maastricht University.

J. Whittingham

J. Whittingham is a lecturer at Maastricht University. She is the chair for taskforce programme evaluation in the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences. Her research interests involve the different aspects of quality assurance.

D. Dolmans

D. Dolmans is a professor of innovative learning arrangements at Maastricht University. She has published on problem-based learning, faculty development and quality assurance in higher education.

References

- Adcroft, A. 2011. “The Mythology of Feedback.” Higher Education Research and Development 30 (4): 405–419. doi:10.1080/07294360.2010.526096.

- Black, P., and D. Wiliam. 2009. “Developing the Theory of Formative Assessment.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 21 (1): 5–31. doi:10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5.

- Bloxham, S., and A. West. 2004. “Understanding the Rules of the Game: Marking Peer Assessment as a Medium for Developing Students’ Conceptions of Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 29 (6): 721–733. doi:10.1080/0260293042000227254.

- Bloxham, S., and A. West. 2007. “Learning to Write in Higher Education: Students’ Perceptions of an Intervention in Developing Understanding of Assessment Criteria.” Teaching in Higher Education 12 (1): 77–89. doi:10.1080/13562510601102180.

- Burke, D., and J. Pieterick. 2010. Giving Students Effective Written Feedback. New York: Open University Press.

- Carless, D. 2006. “Differing Perceptions in the Feedback Process.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (2): 219–233. doi:10.1080/03075070600572132.

- Cartney, P. 2010. “Exploring the Use of Peer Assessment as a Vehicle for Closing the Gap between Feedback Given and Feedback Used.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (5): 551–564. doi:10.1080/02602931003632381.

- Chanock, K. 2000. “Comments on Essays: Do Students Understand What Tutors Write?” Teaching in Higher Education 5 (1): 95–105. doi:10.1080/135625100114984.

- Connor, U., and K. Asenavage. 1994. “Peer Response Groups in ESL Writing Classes: How Much Impact on Revision?” Journal of Second Language Writing 3 (3): 257–276. doi:10.1016/1060-3743(94)90019-1.

- Creswell, J. W. 2012. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

- Crisp, B. R. 2007. “Is It Worth the Effort? How Feedback Influences Students’ Subsequent Submission of Assessable Work.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 32 (5): 571–581. doi:10.1080/02602930601116912.

- De Kleijn, R. A. M., P. C. Meijer, A. Pilot, and M. Brekelmans. 2014. “The Relation between Feedback Perceptions and the Supervisor–Student Relationship inMaster’s Thesis Projects.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (4): 336–349. doi:10.1080/13562517.2013.860109.

- Duijnhouwer, H., F. J. Prins, and K. M. Stokking. 2012. “Feedback ProvidingImprovement Strategies and Reflection on Feedback Use: Effects on Students’ Writing Motivation, Process and Performance.” Learning and Instruction 22 (3): 171–184. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.10.003.

- Glover, C., and E. Brown. 2006. “Written Feedback for Students: Too Much, Too Detailed or Too Incompressible to Be Effective?” Bioscience Education 7 (1): 1–16. doi:10.3108/beej.2006.07000004.

- Hattie, J., and H. Timperley. 2007. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of EducationalResearch 77 (1): 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487.

- Hedgcock, J., and N. Lefkowitz. 1992. “Collaborative Oral/Aural Revision in Foreign Language Writing Instruction.” Journal of Second Language Writing 1 (3): 255–276. doi:10.1016/1060-3743(92)90006-B.

- Hendry, G. D., S. Armstrong, and N. Bromberger. 2012. “Implementing Standards-based Assessment Effectively: Incorporating Discussion of Exemplars into Classroom Teaching.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 37 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1080/02602938.2010.515014.

- Hendry, G. D., N. Bromberger, and S. Armstrong. 2011. “Constructive Guidance and Feedback for Learning: The Usefulness of Exemplars, Marking Sheets and Different Types of Feedback in a First Year Law Subject.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 36 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/02602930903128904.

- Higgins, R., P. Hartley, and A. Skelton. 2001. “Getting the Message Across: The Problemof Communicating Assessment Feedback.” Teaching in Higher Education 6 (2): 269–274. doi:10.1080/13562510120045230.

- Jonsson, A. 2012. “Facilitating Productive Use of Feedback in Higher Education.” Active Learning in Higher Education 14 (1): 63–76. doi:10.1177/1469787412467125.

- Krych-Appelbaum, M., and J. Musial. 2007. “Students’ Perception of Value of Interactive Oral Communication as Part of Writing Course Papers.” Journal of Instructional Psychology 34 (3): 131–136.

- Liu, J., and R. W. Sadler. 2003. “The Effect and Affect of Peer Review in Electronic versus Traditional Modes on L2 Writing.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 2: 193–227. doi:10.1016/S1475-1585(03)00025-0.

- Moust, J. H. C., H. J. M. van Berkel, and H. G. Schmidt. 2005. “Signs of Erosion: Reflections on Three Decades of Problem-based Learning at Maastricht University.” Higher Education 50: 665–683. doi:10.1007/s10734-004-6371-z.

- Nicol, D. J., and D. Macfarlane-Dick. 2006. “Formative Assessment and Self-regulated Learning: A Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (2): 199–218. doi:10.1080/03075070600572090.

- Peterson, R. A. 1994. “A Meta-analysis of Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (2): 381–391. doi:10.1086/jcr.1994.21.issue-2.

- Rae, A. M., and D. K. Cochrane. 2008. “Listening to Students: How to Make Written Assessment Feedback Useful.” Active Learning in Higher Education 9 (3): 217–230. doi:10.1177/1469787408095847.

- Reese-Durham, N. 2005. “Peer Evaluation as an Active Learning Technique.” Journal of Instructional Psychology 32 (4): 338–345.

- Sargeant, J., E. McNaughton, S. Mercer, D. Murphy, P. Sullivan, and D. A. Bruce. 2011. “Providing Feedback: Exploring a Model (emotion, Content, Outcomes) for Facilitating Multisource Feedback.” Medical Teacher 33 (9): 744–749. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2011.577287.

- Schuitema, J., H. Radstake, J. van de Pol, and W. Veugelers. 2018. “Guiding Classroom Discussions for Democratic Citizenship Education.” Educational Studies 44 (4): 377–407. doi:10.1080/03055698.2017.1373629.

- Stalmeijer, R. E., N. McNaughton, and W. N. K. A. Van Mook. 2014. “Using Focus Groups in Medical Education Research: AMEE Guide No. 91.” Medical Teacher 36 (11): 923–939. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2014.917165.

- Tsui, A. B. M., and M. Ng. 2000. “Do Secondary L2 Writers Benefit from Peer Comments?” Journal of Second Language Writing 9 (2): 147–170. doi:10.1016/S1060-3743(00)00022-9.

- Van Den Berg, I., W. Admiraal, and A. Pilot. 2006. “Designing Student Peer Assessment in Higher Education: Analysis of Written and Oral Peer Feedback.” Teaching in Higher Education 11 (2): 135–147. doi:10.1080/13562510500527685.

- Van der Schaaf, M., L. Baartman, F. Prins, A. Oosterbaan, and H. Schaap. 2013. “Feedback Dialogues that Stimulate Students’ Reflective Thinking.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 57 (3): 227–245. doi:10.1080/00313831.2011.628693.

- Weaver, M. R. 2006. “Do Students Value Feedback? Student Perceptions of Tutors’ Written Responses.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 31 (3): 379–394. doi:10.1080/02602930500353061.

- Williams, K. 2005. “Lecturer and First Year Student (mis)understandings of Assessment Task Verbs: ‘mind the Gap’.” Teaching in Higher Education 10 (2): 157–173. doi:10.1080/1356251042000337927.

- Winder, R., S. S. Kathpalia, and S. Ling Koo. 2016. “Writing Centre Tutoring Sessions: Addressing Students’ Concerns.” Educational Studies 42 (4): 323–339. doi:10.1080/03055698.2016.1193476.

- Yucel, R., F. L. Bird, J. Young, and T. Blanksby. 2014. “The Road to Self-assessment:Exemplar Marking before Peer Review Develops First-year Students’ Capacity to Judge the Quality of a Scientific Report.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (8): 971–986. doi:10.1080/02602938.2014.880400.