ABSTRACT

PCK is seen as the transformation of content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge into a different type of knowledge that is used to develop and carry out teaching strategies. To gain more insight into the extent to which PCK is content specific, the PCK about more topics or concepts should be compared. However, researchers have rarely compared teachers’ concrete PCK about more than one topic. To examine the content dependency of PCK, we captured the PCK of sixteen experienced Dutch history teachers about two historical contexts (i.e. topics) using interviews and Content Representation questionnaires. Analysis reveals that all history teachers’ PCK about the two contexts overlaps, although the degree of overlap differs. Teachers with relatively more overlap are driven by their overarching subject related goals and less by the historical context they teach. We discuss the significance of these outcomes for the role of teaching orientation as a part of PCK.

Experienced history teachers know how to teach the content of an existing curriculum to facilitate the understanding of their students. They choose and develop examples, representations, assignments, strategies, and tests to explain content to a specific group of students. In 1986, Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) was introduced by Lee Shulman for that part of teacher knowledge that a teacher uses for the transformation from content knowledge to pedagogical products and teaching strategies. Ever since, researchers and teacher educators have intensively discussed the meaning of PCK. Although different definitions of PCK and its elements exist, there is general agreement on its content specific character (Gess-Newsome Citation2015; Kind Citation2009). However, most researchers have examined the PCK about one topic or substantive concept in a specific context. The PCK about one topic is generally understood not to be transferable to another topic and that makes PCK content specific (Loughran, Berry, and Mulhall Citation2006; Mavhunga Citation2016). To gain more insight into the extent to which PCK is content specific, the PCK about two or more topics or concepts should be compared. Thus far, to the best of our knowledge such studies are rare (Mavhunga Citation2016; Tuithof Citation2017.

In the research project described in this article, we capture and compare the PCK of a group of 16 experienced Dutch history teachersFootnote1 from different schools and backgrounds about two different historical contexts in the Dutch history curriculum, namely (1) the clash between Greco-Roman culture and the Germanic cultures of North-West-Europe and (2) waging World Wars I and II. Historical contexts are an important part of the Dutch history curriculum and should be interpreted differently than contexts in other subjects. We shall explain this further in the following section. We aim to investigate the differences and similarities of the individual teachers’ PCK across the two historical contexts. To gain insight into the content dependency of PCK, we analyse the PCK between the teachers. A comparison of the PCK about two specific historical contexts can shed more light on the content dependency of PCK and, consequently, inform more general PCK debates. Our research produces practical insights for history teachers and teacher educators involved in teacher education for history teaching.

Theoretical framework

The Conceptualisation of PCK

In order to relate the content knowledge of teachers more specifically to the context of their teaching practice, Shulman proposed the concept of Pedagogical Content Knowledge as a specific and unique form of teacher knowledge. PCK is seen as the transformation of content knowledge to pedagogical products and teaching strategies (Shulman Citation1986, Citation1987; Verloop, Van Driel, and Meijer Citation2001). PCK gives a teacher “the flexibility to select a teaching method that does justice to the topic” (Gudmundsdottir and Shulman Citation1987, 69). Shulman’s emphasis on teachers’ PCK closely connects with older, European traditions on subject related pedagogy, which are referred to as “Fachdidaktik” in German, “didactique spéciale” in French, and “vakdidactiek” in Dutch (Depaepe, Verschaffel, and Kelchtermans Citation2013; Van Driel and Berry Citation2010). In these traditions, researchers also looked into subject related questions about learning and teaching without using the concept PCK (Van Driel and Berry Citation2010). The construct of PCK fits further in a constructivist paradigm. Not only PCK is a social construct that makes the complex nature of subject specific teacher knowledge comprehensible (Guba and Lincoln Citation1994). PCK development is also understood Footnote2as an active and social process of knowledge construction.

Two key PCK elements in Shulman’s model are (1) instructional strategies and representations, i.e. the way in which the teacher transforms subject matter knowledge, and (2) knowledge of students’ understanding, i.e. the learning process and the content related problems of the students (Jung et al. Citation2011; Shulman Citation1987). Researchers have used these two key elements as starting points, subsequently adding new PCK elements.

A much cited model of the PCK of science teachers was developed by Magnusson, Krajcik, and Borko (Citation1999) building on Shulman (Citation1987), Grossman (Citation1990), and Tamir (Citation1988). This model contains five PCK elements. PCK element (1) knowledge of instructional strategies is connected to content knowledge and the way in which the teacher transforms the content into illustrations, examples, and teaching strategies. The PCK element (2) knowledge of students’ understanding covers the learning process and the problems of the students related to content knowledge. The element (3) knowledge of assessment pertains to the knowledge that teachers use to establish what students have learned. The fourth element (4) contains the knowledge about the curriculum and corresponding curricular goals prescribed by the educational authorities and the knowledge that a teacher needs to implement and plan this curriculum. Element (5) teaching orientation represents “a general way of viewing or conceptualizing science teaching” (Citation1999, 97) in the words of Magnusson and colleagues. They argue that this component is significant because “these knowledge and beliefs serve as a ‘conceptual map’ that guides instructional decisions” (Magnusson, Krajcik, and Borko Citation1999, 97). The exact role of teaching orientation is still under discussion and connects with a general debate on the impact of teacher beliefs and goals on decisions in the classroom (Barton and Levstik Citation2003; Gess-Newsome Citation2015; Phipps and Borg Citation2009; Pajares Citation1992). For example, Pajares (Citation1992) claimed based on his seminal review that teachers’ beliefs act as a filter through which teachers interpret new information and experience. More recently, several leading PCK researchers as described by Gess-Newsome (Citation2015), also stressed that the straightforward impact of teaching orientations and beliefs is not at all clear and they should, therefore, only be seen as an amplifier or filter (Gess-Newsome Citation2015).

Although Shulman’s key elements and Magnusson’s model mentioned above have been widely cited and used (Evens, Elen, and Depaepe Citation2016; Gess-Newsome Citation2015), there is still debate about the specific role of content or subject matter knowledge in PCK itself. Shulman describes content knowledge as a source but not as part of PCK and PCK as an amalgam of content and pedagogical knowledge (Shulman Citation1987). Yet, based on her observations in history lessons, Turner-Bisset (Citation1999) states that PCK and content knowledge cannot be separated. Reviewing various PCK models, Kind (Citation2009) argues that the models that comprise Shulman’s key components and define PCK as separate and transformed knowledge have more explanatory power for teacher education and PCK development, when compared to models that integrate content knowledge in PCK. Separating content knowledge from PCK has the advantage that it explains why novices with a great deal of content knowledge hardly demonstrate PCK, as PCK requires transformation of this knowledge for which teaching experience is a condition (Kind Citation2009). Furthermore, in a more recent PCK conceptualisation of several leading PCK researchers as described by Gess-Newsome (Citation2015), content knowledge is seen as a PCK source, but not as an integral part of PCK.

This leads to our definition of PCK. We follow the definition of the leading PCK researchers mentioned above as described by Gess-Newsome (Citation2015). They make a distinction between (1) PCK as: “the knowledge of, reasoning behind, and planning for teaching a particular topic in a particular way for a particular purpose to particular students for enhanced student outcomes” and (2) PCK and skill as “the act of teaching a particular topic in a particular way for a particular purpose to particular students for enhanced student outcomes” (Gess-Newsome Citation2015, 36). We have limited our analysis of the PCK of history teachers to “the knowledge of, reasoning behind, and planning for teaching”, so the PCK that is used in designing a lesson of pedagogical strategy. This definition implies that PCK has a content dependent nature (Kind Citation2009; Loughran, Berry, and Mulhall Citation2006; Van Driel and Berry Citation2010). We will follow this line of reasoning in Shulman (Citation1987), Kind (Citation2009), and Gess-Newsome (Citation2015) in separating content knowledge from PCK. Our research focuses on PCK as the transformation of content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge into a different type of knowledge that is used to develop and carry out teaching strategies. Having content knowledge differs from having the knowledge to explain and transfer this knowledge to others. A history teacher needs content knowledge as a source in order to choose certain teaching materials, but in doing so, knowledge about instruction, the knowledge, beliefs, and interests of the students and the curriculum is also needed.

Research on history teachers’ PCK

The learning and teaching of history has been the subject of research in different countries among which the USA, Great Britain, Belgium and the Netherlands (Achinstein and Fogo Citation2015; Wilson Citation2001; Wineburg Citation1996; Van Drie and Van Riessen Citation2010; Tuithof Citation2019). Wilson (Citation2001) observed a surge in studies of good history teachers and teaching in the 1980s. Levesque and Clark state in their contribution to The International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning (Citation2018) that the concept of historical thinking has become a “standard” in the theory and practice of history education across the Western world. Other researchers speak of historical reasoning (Van Boxtel and Van Drie Citation2018). We use the concept of historical reasoning and define it as follows: firstly, the evaluation and construction of a description of processes of change and continuity; secondly, an explanation of a historical phenomenon; thirdly, a comparison of historical phenomena or periods (Van Drie and Van Boxtel Citation2008; Van Boxtel and Van Drie Citation2018).

Some of these studies are inspired by Shulman’s introduction of the concept of PCK in 1986. However, researchers rarely conceptualise PCK in empirical research on history teachers (Achinstein and Fogo Citation2015; Author, 2019). Cunningham reflected in 2007 on the importance of the concept PCK in the domain of history. She observed that research had mainly focused on how to learn and teach content knowledge (first-order knowledge) and related knowledge of disciplinary strategies (second-order knowledge and strategic knowledge) and not on a definition or description of PCK of history teachers (Cunningham Citation2007). Monte-Sano and Budano’s research (Citation2013) is an exception. They identified four subject related PCK elements that are linked to historical reasoning. In their analysis of the literature, they refer to these PCK components: (1) representing history (the ways in which teachers communicate the nature and structure of historical knowledge to students); (2) transforming history (how teachers transform historical content in lessons and materials that target the development of historical understanding and thinking); (3) attending to students’ ideas about history (identifying and responding to students’ thinking about history, including misconceptions and prior knowledge); (4) framing history (selecting and arranging topics into a coherent story thereby framing a history curriculum that illustrates significance, connection, and interrelationships) (Monte-Sano and Budano Citation2013, 174). They use these subject related components to analyse the PCK development of novice teachers. These components are related to Shulman (Citation1987) and Magnusson and colleagues (Citation1999) and they are tailored to the disciplinary nature of history.

Our PCK framework

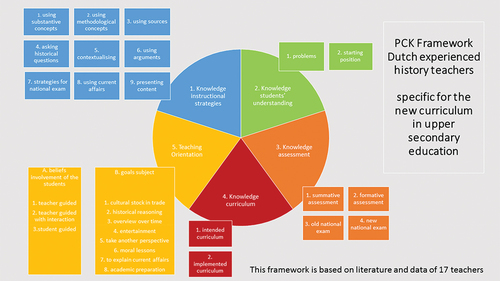

In previous research, we introduced a general framework to describe the PCK of experienced Dutch history teachers (see ) (Tuithof Citation2017). This framework describes the whole PCK of Dutch history teachers and including, but not limited to the PCK of historical reasoning. Magnusson’s model with five PCK elements (Citation1999) served as the starting point for the development of this framework. We subsequently examined theory on PCK and history teachers and interviewed 16 experienced history teachers who also filled in questionnaires. Even though we used Magnusson’s PCK elements, our categories for the history teachers’ PCK differ, because we made our framework specific for the Dutch history curriculum and the nature of the subject history. For example, in our framework, the PCK element teaching orientation has two dimensions: (1) beliefs about the involvement of the students, and (2) subject related goals.

Figure 1. PCK Framework Dutch experienced history teachers specific for the curriculum in upper secondary education.

Our framework describes the five PCK elements separately although an important characteristic of PCK is how the different elements relate to one another, for example, how teachers understand student understanding in relation to specific content. The literature emphasises the role of teaching orientation in relation to the other elements and discusses its potential steering role. Grossman (Citation1990) portrayed purposes for teaching subject matter as an overarching PCK element that influences the other PCK elements, but is simultaneously influenced by them (Grossman Citation1990). Magnusson and her colleagues introduced the term (5) teaching orientation as a central, steering PCK element (Friedrichsen and Dana Citation2003; Magnusson, Krajcik, and Borko Citation1999). Accordingly, Barton and Levstik (Citation2003) state that studies on history teaching show that teachers with comparable levels of knowledge teach in very different ways depending on their subject related goals. Recently, Gess-Newsome (Citation2015) has questioned the straightforward impact of teaching orientations and advocates that teaching orientations should only be seen as an amplifier or filter (Gess-Newsome Citation2015).

The research that exists on the PCK of history teachers is mainly qualitative and often based on a small group of participants (Author, 2017; Author, 2019). Because this kind of research is context specific, it is difficult to generate general conclusions regarding the PCK of history teachers. Descriptions of concrete PCK are rare in PCK research in general (Bertram and Loughran Citation2012; Shulman Citation2015; Author, 2019). This gap may be caused by the nature of PCK as complex tacit knowledge. It is, therefore, difficult to measure and capture (Bertram and Loughran Citation2012; Henze and Van Driel Citation2015; Van Driel, Verloop, and de Vos Citation1998). One rare example of a specific description of the PCK of history teachers can be found in Harris and Bain (Citation2011). Their instrument is a card sorting task which asks history teachers to structure events from world history. This instrument is interesting because it compels the teachers to make their PCK (knowledge of instructional strategies) visible and enables a comparison between experienced and inexperienced world history teachers (Harris and Bain Citation2011).

The current study

We expect that history teachers’ PCK differs partly per historical context but also per teacher since PCK is assumed to be content dependent. To capitalise on content differences, we purposefully choose two historical contexts from the Dutch history curriculum and tried to establish individual teachers’ PCK across these two contexts. The main research questions of this article are: Is there an overlap in history teachers’ PCK on two different historical contexts of the history curriculum? And how can we explain the (lack of) overlap? Our description of the history teachers’ PCK of two historical contexts generates insights for history teachers and teacher educators involved in teacher education for history teaching. We also expect that a description and comparison of the PCK on two different historical contexts will increase our knowledge about the relations between the five PCK elements and elucidate the ongoing debate about the role of teaching orientation.

Method

Participants

Henze and Van Driel (Citation2015, 1210) describe PCK as flexible knowledge that “develops over time based on teachers’ experience of teaching a topic repeatedly”. Consequently, experienced teachers have more PCK than novices. Therefore, we wanted to describe the PCK of experienced history teachers in our research project. We invited teachers with a teaching degree for upper secondary education and at least five years of experience in teaching students who are preparing for the national exam. We placed a request on several Dutch websites and we sent emails to history teachers in our network. Eventually, we found nineteen teachers that met our inclusion criteria and that were prepared to participate in our research project. These nineteen selected teachers all have a master in History. The teachers work at different schools spread all over the country. The experience of the teachers differs from five to 35 years of experience in upper secondary education. For anonymity, we use numbers in referring to the teachers. Two of them were approached several times, but appeared not to be able to complete all the instruments because of difficult personal circumstances. One teacher completed all the instruments, but failed to complete the member check, despite several reminders. All in all we analysed the data of sixteen history teachers. The teachers work at different secondary schools. Moreover, their teaching experience differs from five to 35 years in upper secondary education. See for some characteristics of the teachers.

Table 1. The characteristics and overlap of the teachers in ascending order.

The Dutch curriculum

The sixteen teachers all work with an open national history curriculum which requires them to choose their own concrete examples and corresponding pedagogical strategies. The Dutch curriculum has a Western-European perspective. The intended goal of the curriculum is to teach the students to use a frame of reference in order to obtain a global historical overview and use this knowledge for historical reasoning (Klein Citation2010; Van der Kaap Citation2009). The curriculum sets goals connected to historical reasoning and describes a frame of reference consisting of ten eras with 49 corresponding “characteristic features” (in Dutch: kenmerkende aspecten). Three examples of these features, which are distinguished for the tenth era (1950–2000), are: decolonisation which ended western hegemony in the world; the unification of Europe; the development of multiform and multicultural societies. These so called characteristic features contextualise substantive concepts in a specific historical context. For the sake of clarity for an international audience we refer to them as historical contexts from now on.

Instruments

Harris and Bain (Citation2011) used a card sorting task to make history teachers’ PCK of world history visible. The Content Representation-format (CoRe) of Loughran, Berry, and Mulhall (Citation2006) is a more widely used instrument that captures PCK. As far as we know, this instrument has not been used in research projects examining history teachers yet. We have used the CoRe questionnaire to capture the PCK of the teachers on the two historical contexts mentioned above (Loughran, Berry, and Mulhall Citation2006). The teachers have also been interviewed in order to capture their general PCK about the curriculum in upper secondary education. In what follows, both instruments are explained.

The CoRe questionnaire

The CoRe questionnaire includes eight questions that encourage teachers to think about their pedagogical transformation of a topic (Bertram Citation2012; Hume and Berry Citation2011; Kind Citation2009; Nilsson Citation2008), for example the instructional strategies they would use and the relevance of the topic to the student. In their study of the PCK of expert science teachers, Bertram and Loughran (Citation2012) validate the CoRe questionnaire as a meaningful method for examining PCK. According to Henze, Van Driel, and Verloop (Citation2008, 1340) this format is “a way to make teachers’ tacit knowledge explicit”. In the original design the participants were asked to think about their own concepts within a given topic (Loughran, Berry, and Mulhall Citation2006). We prescribed two historical contexts to enable comparisons across teachers.

We translated the CoRe questionnaire into Dutch () and omitted question 3 about knowledge beyond the curriculum because it was less relevant to the purposes of this study. The CoRe questionnaire was sent to the teachers by email. Teachers filled it in for the two historical contexts (1) the clash between Greco-Roman culture and the Germanic cultures of North-West-Europe and (2) waging World Wars I and II and then returned it. We asked the teachers to choose a preferred assignment or instructional strategy for each historical context. The advantage of the latter is that a concrete example was added to the teachers’ answers.

Table 2. Co-Re instrument inspired by Loughran, Berry, and Mulhall (Citation2006).

As explained above, the selected contexts in our study are two examples of the characteristic features of an era (1) The clash between Greco-Roman culture and the Germanic cultures of North-West-Europe and (2) waging World Wars I and II. The first historical context indicates the encounter of and exchange between the Romans and Germanic tribes in what is now roughly Germany, Holland, and England (58 BCE – ca. 350 CE). It encompasses military conflicts, but also processes of cultural exchange (romanisation, religious syncretism), as well as the first encounters with Christianity (the neighbouring Celts, who had a rather different culture than the Germans, are excluded). The second historical context (2) indicates the causes, courses, and aftermaths of both the First and Second World War in Europe (albeit in a rather unspecific way).

We have chosen the first historical context because it is a relatively new and small context in the Dutch curriculum. The second context (2) waging World Wars I and I has already been an important historical context for years. Generally, history teachers have strong opinions about this context for several reasons: the period it denotes belongs to recent history; teachers’ parents lived through World War II; Dutch society as a whole still has strong opinions about these wars (Wansink, Akkerman, and Wubbels Citation2016). Considering the differences between the two historical contexts and the content dependency of PCK, we expect the history teachers to have different PCK about the two historical contexts.

The semi-structured interview

The semi-structured interviews were used to explore the general PCK and the context of the teachers. We asked the sixteen history teachers questions about the five PCK elements linked to the curriculum (the structure of the interview and some sample questions are given in ). The interviews lasted 90 minutes on average after the teachers had filled in the CoRe questionnaire. As the transcripts of the interviews also contained irrelevant information, we made summaries regarding all the PCK elements (Achinstein and Fogo Citation2015; following Pillen, Beijaard, and Den Brok Citation2013). contains the categories that we used to make the summary of the interviews including representative quotes. The summaries were member checked by the teachers.

Table 3. The categories used to summarise interviews.

Table 4. The structure of the interview and examples of the interview questions.

Analysis

We used the earlier mentioned PCK framework (Author, 2017) () to analyse the data gathered with the CoRe questionnaires. This framework describes the PCK of Dutch history teachers and uses the five PCK elements of Magnusson as a starting point. A process of theoretical matching combined with analysis of empirical data led to this framework (Goldkuhl and Cronholm Citation2010).

For our analysis of the answers provided by the history teachers in the CoRe questionnaire, we first established whether the PCK elements and corresponding subcategories of our PCK framework were present in the answers about the two historical contexts (coding scheme in Appendix 1). To illustrate this step, we included the codes alongside the answers of three teachers (Appendix 2, 3, 4). Second, we established the similarities and differences between the coded answers of the history teachers about the two historical contexts. Third, we established which part of the answers on the two contexts per teacher was the same for both contexts, or in other words, which part of the PCK was the same. To be more exact, we calculated the percentage overlap of the codes per PCK element and the weighted average for the two historical contexts overall. Fourth, we sorted the teachers according to the degree of overlap in their PCK (see ). Finally, the summaries of the interviews were used for an explanation of the outcomes and differences between the teachers (Achinstein and Fogo Citation2015; Pillen, Beijaard, and Den Brok Citation2013).

Two research assistants coded all the CoRe questionnaires in the presence of the first author whom they consulted when in doubt. All the coding was subsequently verified by the first author who made a few small additions mainly regarding the fifth PCK element teaching orientation. We documented all these steps in a formative audit trail (Akkerman, Admiraal, Brekelmans, & Oost, Citation2008) about the data collection with a researcher in the field of PCK and history who is no author of this article (Leiden University, The Netherlands). He reconstructed our entire analytic procedure. He saw all the data sources and checked a selection of the data. Eventually, he evaluated our findings as grounded in the data and our analytic steps as sufficiently visible, comprehensive, and acceptable.

Results

Overlap in teachers’ PCK

All teachers showed substantial overlap in their coded PCK on two historical contexts but the overlap between the two contexts per teacher differed (see ). On the one hand, there were two teachers with only fifty percent overlap. They show many similarities between their PCK about the two historical contexts, but relatively little overlap and more differences between the PCK elements for the two contexts than the other teachers. On the other hand, one teacher has the same coded PCK for both historical contexts.

To illustrate our findings, we will describe three examples of teachers:

Doris (teacher 3) is a teacher with less overlap between her PCK about the two historical contexts. Her PCK about the two contexts differs the most compared to the other teachers.

Margie (teacher 15) is a teacher with average overlap between the PCK about the two historical contexts. She has more overlap than Doris but less than Anthony.

Anthony (teacher 19) has a total overlap between the PCK about the first and second context.

Doris

“I am and will always a be a teacher that likes to share stories and information. So I generally share stories and information, show images, give assignments, and discuss the outcomes.” Doris has twenty years of teaching experience in upper secondary education. She is the teacher whose PCK about the two contexts differs most ( and Appendix 2). Her PCK overlaps least and is related to the historical context in the strongest way. When answering the questions in the CoRe questionnaire, she partly chose other instructional strategies and goals for the two historical contexts. For the context (1) the clash between Greco-Roman culture and the Germanic cultures of North-West-Europe, she mentions goals that are related to content, historical reasoning, moral development, and explaining current affairs (see question 2 in Appendix 2). For the context waging World Wars I and II, she mentions only goals that are linked to moral development. For this historical context she chose explanation, debate, films, and some student involvement; yet, for the first context she chose teacher-guided discussion and explanation (see question 6 in Appendix 2). She describes her reasons for these choices for the context (2) waging World Wars I and II as follows: “I want to show my students in upper secondary how illogically people can behave in wartime, that not everything is black and white in wartime. They might think they won’t be capable of doing terrible things, but they will or at least they won’t be war heroes.”

In her interview, Doris said that she is used to explaining content enthusiastically with many examples, illustrations, and anecdotes. She prefers to explain the full content and, if there is time, students will process the subject matter knowledge in another way, for instance by using the assignments in the method. The majority of the lessons are used for explanation and teacher-guided discussion. She also wants to show students a variety of perspectives to encourage critical thinking and historical reasoning.

Adequately preparing the students for their national exam and providing them with clarity about the goals of the national exam is also important to her, as is shown by the historical dossier she handed in. The assignments in this historical dossier helped the students to develop a frame of reference, which is an important goal of this curriculum. Although Doris aims for variation in her instructional strategies, she wants to explain content first, preferably in a thorough way. In the CoRe questionnaire (question 4) she claims: “By telling students what to note down, I try to help students to structure the content effectively.” See Appendix 2 for her coded answers on the CoRe questionnaire.

Margie

Margie has fifteen years of experience in upper secondary education. She has fewer differences in her PCK about the two historical contexts than Doris. For the context (1) the clash between Greco-Roman culture and the Germanic cultures of North-West-Europe, she chose goals that are related to the subject related goal multi perspectivity: her students study different sources, film fragments, and a historical object. For the second context, this teacher has goals that are linked to historical reasoning. She uses several instructional strategies such as working with cartoons, films, and quizzes. She also links history to the present (see questions 6 and 7 in Appendix 3). Thus, Margie uses many different instructional strategies to motivate her students and she uses different strategies for different historical contexts or concepts with only a limited number of goals. She mentioned fewer goals than Doris and there is more variety in the activities that she refers to in the CoRe questionnaire and the interview. Students, content, and her subject related goals are together determining her PCK.

Margie said in the interview that she wants her students to be motivated and to constantly process the subject matter knowledge. She is very concerned about the motivation and achievement of her students and tries to inspire them whenever she can. Her pedagogical repertoire is rich judging from the various varied pedagogical products she handed in. As she explains in her interview:

“We do a lot of different things: I add a small assignment, preferably with sources, so some skills, to process what they have heard. I do group assignments regularly, and once a month I do an assignment on the computer; they have to search some information or use a nice educational website. I use an educational paper about the Golden Age and let the students sort something out about a specific period of that age. And then they have to exchange, so yes, I try to variate. I also use film fragments, very often with an assignment.”

She thinks that content knowledge is important, but she also aims to teach historical reasoning. For each historical context or topic, she develops tasks (in cooperation with her colleagues) or she chooses sources, images, music, or film fragments that will help her students to learn about the topic at hand. See Appendix 3 for her coded answers on the CoRe questionnaire.

Anthony

Anthony has taught for fifteen years. There are no differences between the coding of the PCK of the two historical contexts except one extra subject related goal for the second context. The goal historical reasoning is driving this teacher’s PCK. His lessons and assignments all aim at historical reasoning and related goals such as overview over time, multi perspectivity, and academic preparation (see answer 1 in Appendix 4). He uses the same instructional strategies for different contexts. All historical contexts, concepts and topics in his lessons are related to historical reasoning. He explains this as follows “I have to teach historical reasoning. Most historical facts will be forgotten. However, I am able to teach them develop historical reasoning during their school years.” He designs many tasks for the students and gathers these tasks in a dossier, all from the perspective of historical reasoning.

In the interview, he explained that the students have to describe the characteristics of the different periods and extend and deepen this knowledge by working with sources and historical questions. He thinks that history as a subject is very important and says in the interview:

“Just because the historical second order concepts are used in daily life. That is not just in the domain of history, but for scientific education in general.” (…) “Because you need to understand historical development and I always say, guys, the essential part of history is this development.”

The instruction for the students is all on paper (including roadmaps), examples of which Anthony handed in. This teacher explains the content and coaches the students, but he does not have many plenary moments during the lessons, so the students largely work independently. Thus, Anthony has the same goal for different historical contexts and his instructional strategies are connected with this subject related goal. See Appendix 4 for his coded answers on the CoRe questionnaire.

In the description of the three teachers, we observe a distinction between Doris whose PCK overlaps less and is more related to the specific historical context and Anthony whose PCK overlaps much more and is mainly driven by his subject related goals. Moreover, Margie seems to be driven by both historical contexts as her subject related goals.

Doris, Margie and Anthony’s PCK compared

We used the summaries of the interviews to explain the differences in overlap. In general the teachers with less overlap appear to relate their teaching choices more to a particular context than the teachers with more overlap. The three cases are exemplary for the whole group of teachers. Doris has the least overlap in her PCK and she refers in her CoRe more to the content of the specific contexts. Doris listed historical events and facts the students should memorise, without connecting this to the strategy of using substantive concepts. “In my opinion, students have to know a lot of facts.”

There are also teachers who relate their choices mainly to their subject related goals (such as historical reasoning or moral development). Anthony has the same goals for both historical contexts. He is constantly looking for ways to stimulate the historical thinking of his students in each and all historical contexts. He says “nowadays students may not take enough time to think independently, when so much preconceived information – constructed by others – is readily available”. He relates his subject related goal to his instructional strategies: “My instructional strategies are generally in writing, because I prepare my students for university. Often, these require written assignments.”

There are also teachers that seem to be driven by the historical context and their subject related goals. Margie has a combined focus on content knowledge and historical reasoning. She explains her routine of teaching in the context of World War II. “I assess the knowledge, and then go from there. So, I discuss the Second World War in the Netherlands and not in Germany, as we did in the third year. We also pay attention to ways in which to come to terms with the past. More and more grey areas are becoming apparent. Not everything is clear cut.” Her CoRe in Appendix 3 shows another example of her teaching, an assignment with multi perspectivism as a goal, immersed with rich content knowledge about the specific historical context.

Conclusion and discussion

In this article, we have investigated the PCK of sixteen Dutch experienced history teachers about two historical contexts that are part of the Dutch history curriculum, namely (1) the clash between Greco-Roman culture and the Germanic cultures of North-West-Europe and (2) waging World Wars I and II. The questions that guided our research are: Is there an overlap in history teachers’ PCK on two different historical contexts of the history curriculum? And how can we explain the (lack of) overlap?

All sixteen history teachers showed substantial overlap in their PCK on two historical contexts, but the degree of overlap between the two contexts per teacher differed. We saw that teachers with relatively less overlap relate their choices more to the content and characteristics of the two historical contexts. Teachers with relatively more overlap are driven by their overarching subject related goals (such as historical reasoning or moral development) and less by the historical context they teach. A number of teachers seem to be driven by both the historical contexts and their subject related goals.

This study contributes to the existing body of research on PCK in history and extends it with insight into the content dependency of history teachers’ PCK. Our conclusion that a number of the teachers seem to be driven by their overarching subject related goals matches with part of the existing literature in which teaching orientation is considered to steer teachers’ teaching strategies (Barton and Levstik Citation2003; Friedrichsen, Van Driel, and Abell Citation2011; Magnusson, Krajcik, and Borko Citation1999; Pajares Citation1992). We need to examine teaching orientation more closely in future research. Maybe teaching orientation does have the central, steering role in PCK as proposed by Magnusson, Krajcik, and Borko (Citation1999). However, the history teachers mentioned several subject related goals in their interviews and CoRe questionnaires (see Table 6–8).

The work of Phipps and Borg (Citation2009), who distinguish core and peripheral beliefs of language teachers without using the concept of PCK, could be important here. According to Phipps and Borg (Citation2009), core beliefs are a more generic set of beliefs about learning which are more influential in shaping teachers’ instructional strategies than specific peripheral beliefs about language learning. The teachers in our research who are mainly driven by the historical contexts (or content) might have a core belief about the importance of content knowledge. It is possible that the more content driven teachers in our study are driven by a core belief about content and that their subject related goals are peripheral beliefs subordinate to this core belief. And it might also imply that the core beliefs of the goal driven teachers match with their subject related goals. We hypothesise that teachers have core beliefs that are central to their teaching orientation and steer their PCK (elements), but that they might also have several peripheral beliefs that are less clearly related to PCK (elements). This hypothesis could be important in the debates regarding the role of teaching orientation.

Also these insights can be helpful for history teachers when reflecting on their goals and their classroom practice. For example, it could offer an explanation for their attitude or emotions when there are changes in the curriculum or in their school. Teacher educators could discuss the role of core and peripheral beliefs and its connection with PCK development with student teachers. The CoRe questionnaire as we have designed it could be used as an instrument for teachers and student teachers to discuss and describe their PCK.

When considering the limitations of our research project, we have to realise that it has been conducted in a specific context, namely in upper secondary education in the Netherlands. Furthermore, we analysed the data gathered among a limited number of experienced history teachers. It must also be taken into account that the instruments we used (the CoRe questionnaires and member checked interviews) produce self-reported data and, therefore, might not have captured tacit PCK. Also the chosen historical contexts cover a considerable part of the Dutch curriculum and that could have caused that the answers are not very detailed and concrete.

Our research project has a conceptual character. We showed the content dependable character of PCK from a new perspective, and also discussed the possible steering role of teaching orientation. However, because of the small scale and the specific context of our research, it would be interesting to employ the CoRe questionnaire and our conclusions regarding the overlap of PCK in other domains and in large-scale research projects. Then the content dependable character of PCK could be further explored. This could show us which aspects or parts of PCK are more general and which are content specific. Subject related pedagogical research has been often viewed as a niche in the field of educational research as a whole. The use of the concept PCK and the CoRe questionnaire enables us to compare subject related pedagogical research in different domains and offer also general insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

H. Tuithof

Hanneke Tuithof was a history teacher in upper secondary education. She is a teacher educator in history at Utrecht University since 1996. She teaches in educational master tracks and has also developed various Pedagogical Content Knowledge courses for teachers. In 2012 she started her PhD project at the Departement of History and Art History, Utrecht University. This project focused on the Pedagogical Content Knowledge of experienced history teachers in the context of a curriculum innovation. In april 2017 she became professor at the University of Applied Sciences in Tilburg. Now she is a reseracher and senior teacher educator at Utrecht University. She is also an advisor in national curriculum projects in the Netherlands.

J. Van Drie

Jannet van Drie is Associate Professor at the Research Institute of Child Development and Education of the University of Amsterdam. Her research focusses on the learning and teaching of history, with a particular focus on historical reasoning.

L. Bronkhorst

Larike Bronkhorst is Assistant Professor of Education at Utrecht University. Her work focusses on learning across the boundaries of school and interorganizational collaboration in education and health care.

L. Dorsman

Leen Dorsman is head of Utrecht University ‘s Department of History and Art History. He is professor of History of Universities. His research and teaching focusses on the intersection of literature and history.

J. Van Tartwijk

Jan van Tartwijk is the director of Utrecht University's Graduate School of Teaching. In his research and teaching, he focusses on teacher-student communication processes in the classroom (in particular in multicultural classrooms), on learning and assessment in the workplace, on the association between assessment, motivation, and creativity, and on the development of teacher expertise and the contribution teacher education can make to the development of teacher expertise.

Notes

1. We started with 17 teachers, but one of them had to leave our research project because of health problems.

2. See http://histoforum.net/history/havovwo.htm for an overview of all the characteristic features.

References

- Achinstein, B., and B. Fogo. 2015. “Mentoring Novices’ Teaching of Historical Reasoning: Opportunities for Pedagogical Content Knowledge Development through Mentor-facilitated Practice.” Teaching and Teacher Education 45: 45–58. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.09.002.

- Akkerman, S., W. Admiraal, M. Brekelmans, and H. Oost. 2008. “Auditing Quality of Research in Social Sciences.” Quality & Quantity 42 (2): 257–274. doi:10.1007/s11135-006-9044-4.

- Barton, K. C., and L. S. Levstik. 2003. “Why Don’t More History Teachers Engage Students in Interpretation?” Social Education 67 (6): 358–358.

- Bertram, A. 2012. “Getting in Touch with Your PCK: A Look into Discovering and Revealing Science Teachers’ Hidden Expert Knowledge.” Teaching Science 58 (2): 18–26.

- Bertram, A., and J. Loughran. 2012. “Science Teachers’ Views on CoRes and PaP-eRs as a Framework for Articulating and Developing Pedagogical Content Knowledge.” Research in Science Education 42 (6): 1027–1047. doi:10.1007/s11165-011-9227-4.

- Cunningham, D. L. 2007. “Understanding Pedagogical Reasoning in History Teaching through the Case of Cultivating Historical Empathy.” Theory & Research in Social Education 35 (4): 592–630. doi:10.1080/00933104.2007.10473352.

- Depaepe, F., L. Verschaffel, and G. Kelchtermans. 2013. “Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Systematic Review of the Way in Which the Concept Has Pervaded Mathematics Educational Research.” Teaching and Teacher Education 34: 12–25. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.03.001.

- Evens, M., J. Elen, and F. Depaepe. 2016. “Pedagogical Content Knowledge in the Context of Foreign and Second Language Teaching: A Review of the Research Literature.” Porta Linguarum 26: 187–200.

- Friedrichsen, P., and T. M. Dana. 2003. “Using a Card-sorting Task to Elicit and Clarify Science-teaching Orientations.” Journal of Science Teacher Education 14 (4): 291–309. doi:10.1023/B:JSTE.0000009551.37237.b3.

- Friedrichsen, P., J. Van Driel, and S. Abell. 2011. “Taking a Closer Look at Science Teaching Orientations.” Science Education 95 (2): 358–376. doi:10.1002/sce.20428.

- Gess-Newsome, J. 2015. “A Model of Teacher Professional Knowledge and Skill Including PCK.” In Re-examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education, edited by A. Berry, P. Friedrichsen, and J. Loughran, 28–42. New York and London: Routledge.

- Goldkuhl, G., and S. Cronholm. 2010. “Adding Theoretical Grounding to Grounded Theory: Toward Multi-grounded Theory.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 9 (2): 187–205. doi:10.1177/160940691000900205.

- Grossman, P. L. 1990. The Making of a Teacher: Teacher Knowledge and Teacher Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Guba, E. G., and Y. S. Lincoln. 1994. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and G. S. Lincoln, 105–117. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Gudmundsdottir, S., and L. Shulman. 1987. “Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Social Studies.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 31 (2): 59–70. doi:10.1080/0031383870310201.

- Harris, L., and R. Bain. 2011. “Pedagogical Content Knowledge for World History Teachers: What Is It? How Might Prospective Teachers Develop It?” The Social Studies 102 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1080/00377996.2011.532724.

- Henze, I., and J. Van Driel. 2015. “Toward a More Comprehensive Way to Capture PCK in Its Complexity.” In Re-examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education, edited by A. Berry, P. Friedrichsen, and J. Loughran, 28–42. New York and London: Routledge.

- Henze, I., J. Van Driel, and N. Verloop. 2008. “Development of Experienced Science Teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge of Models of the Solar System and the Universe.” International Journal of Science Education 30 (10): 1321–1342. doi:10.1080/09500690802187017.

- Hume, A., and A. Berry. 2011. “Constructing CoRes – A Strategy for Building PCK in Pre-service Science Teacher Education.” Research in Science Education 41 (3): 341–355. doi:10.1007/s11165-010-9168-3.

- Jung, J., S. Park, J. Jang, and Y. Chen. 2011. “Is Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) Necessary for Reformed Science Teaching? Evidence from an Empirical Study.” Research in Science Education 41 (2): 245–260. doi:10.1007/s11165-009-9163-8.

- Kind, V. 2009. “Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education: Perspectives and Potential for Progress.” Studies in Science Education 45 (2): 169–204. doi:10.1080/03057260903142285.

- Klein, S. R. E. 2010. “Teaching History in the Netherlands: Teachers’ Experiences of a Plurality of Perspectives.” Curriculum Inquiry 40 (5): 614–634. doi:10.1111/j.1467-873X.2010.00514.x.

- Levesque, S., and P. Clark. 2018. “Historical Thinking: Definitions and Educational Applications.” In The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning, edited by S. A. Metzger and L. Harris McA, 119–148. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Loughran, J., A. Berry, and P. Mulhall. 2006. Understanding and Developing Science Teachers Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Magnusson, S., J. Krajcik, and H. Borko. 1999. “Nature, Sources, and Development of Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Science Teaching.” In Examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge: The Construct and Its Implications for Science Education, edited by J. Gess-Newsome and N. G. Lederman, 95–132. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Mavhunga, E. 2016. “Transfer of the Pedagogical Transformation Competence across Chemistry Topics.” Chemistry Education Research and Practice 17 (4): 1081–1097. doi:10.1039/c6rp00095a.

- Monte-Sano, C., and C. Budano. 2013. “Developing and Enacting Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Teaching History: An Exploration of Two Novice Teachers’ Growth over Three Years.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 22 (2): 171–211. doi:10.1080/10508406.2012.742016.

- Nilsson, P. 2008. “Teaching for Understanding: The Complex Nature of Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Pre-service Education.” International Journal of Science Education 30 (10): 1281–1299. doi:10.1080/09500690802186993.

- Pajares, M. F. 1992. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning up a Messy Construct.” Review of Educational Research 62 (3): 307–332. doi:10.2307/1170741.

- Phipps, S., and S. Borg. 2009. “Exploring Tensions between Teachers’ Grammar Teaching Beliefs and Practices.” System 37 (3): 380–390. doi:10.1016/j.system.2009.03.002.

- Pillen, M. T., D. Beijaard, and P. Den Brok. 2013. “Professional Identity Tensions of Beginning Teachers.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 19 (6): 660–678. doi:10.6100/IR758172.

- Shulman, L. 1986. “Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching.” Educational Researcher 15 (2): 4–14. doi:10.3102/0013189X015002004.

- Shulman, L. 1987. “Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform.” Harvard Educational Review 57 (1): 1–22. doi:10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411.

- Shulman, L. S. 2015. “PCK: Its Genesis and Exodus.” In Re-examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education, edited by A. Berry, P. Friedrichsen, and J. Loughran, 3–13. New York and London: Routledge.

- Tamir, P. 1988. “Subject Matter and Related Pedagogical Knowledge in Teacher Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 4 (2): 99–110. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(88)90011-X.

- Tuithof, H. (2017). “The Characteristics of Dutch Experienced History Teachers’ PCK in the Context of a Curriculum Innovation.” PhD thesis, Utrecht University.

- Tuithof, H., A. Logtenberg, L. Bronkhorst, J. Van Drie, L. Dorsman, and J. Van Tartwijk. 2019. “What Do We Know about the Pedagogical Content Knowledge of History Teachers: A Review of Empirical Research.” Historical Encounters 6 (1): 72–95.

- Turner-Bisset, R. 1999. “The Knowledge Bases of the Expert Teacher.” British Educational Research Journal 25: 39–55. doi:10.1080/0141192990250104.

- Van Boxtel, C., and J. Van Drie. 2018. “Historical Reasoning: Conceptualizations and Educational Applications.” In International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning, edited by S. A. Metzger and L. McArthur Harris. 149–176. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Van der Kaap, A. (2009). Enquête nieuwe examenprogramma voor het vak geschiedenis, [Survey about the new national history examination]. http://downloads.slo.nl/Repository/enquete-nieuwe-examenprogramma-voor-het-vak-geschiedenis.pdf

- Van Drie, J., and C. Van Boxtel. 2008. “Historical Reasoning: Towards a Framework Foranalyzing Students’ Reasoning about the Past.” Educational Psychology Review 20: 87–110. doi:10.1007/s10648-007-9056-1.

- Van Drie, J., and M. Van Riessen. 2010. “Een Vak Dat Zichzelf Serieus Neemt: Vakdidactisch Onderzoek in Nederland (Eindelijk) in De Lift [A School Subject Which Takes Itself Seriously].” Kleio 51: 17–21.

- Van Driel, J., and A. Berry. 2010. “The Teacher Education Knowledge Base: Pedagogical Content Knowledge.” In International Encyclopedia of Education, edited by P. Peterson, E. Baker, and B. McGaw, 656–661. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Van Driel, J. H., N. Verloop, and W. de Vos. 1998. “Developing Science Teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 35 (6): 673–695. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199808)35:6<673::aid-tea5>3.0.CO;2-J.

- Verloop, N., J. H. Van Driel, and P. C. Meijer. 2001. “Teacher Knowledge and the Knowledge Base of Teaching.” International Journal of Educational Research 35 (5): 441–461. doi:10.1016/S0883-0355(02)00003-4.

- Wansink, B. G. J., S. Akkerman, and T. Wubbels. 2016. “The Certainty Paradox of Student History Teachers: Balancing between Historical Facts and Interpretation.” Teaching and Teacher Education 56: 94–105. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.02.005.

- Wilson, S. M. 2001. “Research on History Teaching.” In Handbook of Research on Teaching, edited by V. Richardson, 524–544. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Educational Research Association.

- Wineburg, S. S. 1996. “The Psychology of Learning and Teaching History.” In Handbook of Educational Psychology, edited by D. C. Berliner and R. C. Calfee, 423–437. New York, NY, US: Macmillan Library Reference Usa; London, England: Prentice Hall International.