ABSTRACT

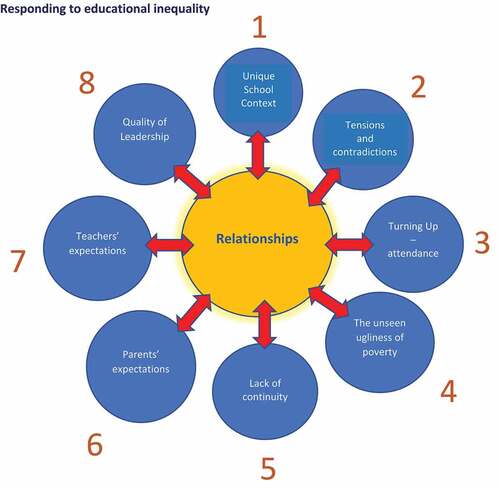

Aspirations to combat educational inequality and disadvantage in Ireland feature strongly in policy documents of recent decades. Teachers and their concerns are not always to the forefront in such publications or, indeed, in associated research. For this study, 20 teachers and school principals who work in schools located in communities with limited levels of economic, cultural and social capital were interviewed. The interviews were open-ended, allowing participants to articulate freely their thoughts and feelings about their work. Transcript analysis led to the identification of eight key themes: context; tensions and contradictions; attendance; the ugliness of poverty; lack of continuity; parents’ expectations; teachers’ expectations; school leadership. Furthermore, we propose that “relationships” is a crucially persistent thread linking the eight themes. We conclude that these themes offer a promising framework for schools to evaluate their practices and to structure a programme of staff development and to their understandings of educational disadvantage.

Introduction and context

Addressing educational inequality is central to policies and practices that aspire to contribute to a society characterised by fairness and social justice. However, as Kelleghan (Citation2001) observes “educational disadvantage” is frequently presented in broad terms, offering little guidance for educational interventions. He elaborates on the definition that:

a child may be regarded as being at a disadvantage at school if because of factors in the child’s environment conceptualized as economic, cultural and social capital, the competencies and dispositions which he/she brings to school differ from the competencies and dispositions which are valued in schools and which are required to facilitate adaptation to school and school learning (ibid, p.5).

His emphasis on the economic, cultural and social dimensions is a reminder that too narrow a focus on academic achievements or cognitive developments is undesirable. Because educational inequality is a manifestation of deeper inequalities in society, it is a multi-faceted issue, difficult to grasp fully and very challenging to address (Willis Citation1977; Kellaghan et al. Citation1995; Baker et al. Citation2004; Lynch nd Baker, Citation2005; Dermody, Smyth, and McCoy Citation2008; Joint Committee on Education and Skills Citation2010; Weir, Cavanagh, Kelleher and Moran, Citation2017; Reay Citation2018; Doyle and Keane Citation2019; Fleming Citation2020). Too often piecemeal solutions are proposed, seemingly forgetting how dimensions of inequality are interwoven.

We write as educational researchers and teacher-educators with previous experience of working in schools characterised as “educationally disadvantaged.” While appreciating the complexity of the challenges, this paper arose from a particular concern to support teachers and school leaders who are working in situations of educational inequality. In Ireland, schools in such situations are part of the DEISFootnote1 programme. We wished to construct a framework to facilitate analysis and professional conversations about the realities of working in such challenging circumstances, in Ireland or elsewhere.

The paper begins with a brief note on the persistence of the term “inequality” within Irish educational discourse and a positioning of the issue in a wider social context and the insights gained by previous researchers. We then outline our research rationale and focus: listening to the views and experiences of 20 teachers and school leaders. This is followed by the identification of eight distinct themesFootnote2 discerned from the process. These themes are presented with evidence from the transcripts and located in the context of wider literature, Irish and international. In the subsequent discussion, we attempt to see some commonality within the eight themes around the concept of “relationships” and propose a framework which might enable teachers, school leaders, policy makers and teacher-educators to engage in professional conversations about working in schools that are attempting to respond appropriately to educational inequality.

The persistence of educational inequality

Educational inequality has been a recurring theme in Irish educational discourse. A significant study in the mid-1980s (Hannan and Boyle Citation1987, 162) regretted the lack of policy attention to the “socially prejudicial allocation of pupils among schools” and noted that “the pursuit of egalitarian citizenship rights has no active political priority or urgency.” One consequence, they contended, was that “educational process over the past 20 years has clearly worked to the benefit of the majority of middle class, and moderate to large farmer class, as well as upper working-class families” (ibid, p.163).

In the subsequent three decades, various studies, policy documents, research papers and commentaries bear testament to the persistence of educational inequality (e.g. Government of Ireland Citation1995Footnote3; Kelleghan Citation2001; Combat Poverty Agency Citation2003; Department of Education and Science Citation2005a; Smyth and McCoy Citation2009; Fleming Citation2016; DES, Citation2016; Coolahan Citation2017; Department of Education and Skills Citation2017a; Fleming Citation2020). While Irish policy has become much clearer in articulating aspirations to “equality” “inclusion” and to advancing “the progress of learners at risk of educational disadvantage”, one needs to be mindful of Gleeson’s (Citation2004, 103) observations whereby policy aspirations often remain as rhetoric.

At the heart of society

Education inequality cuts at the heart of society for many reasons. Everyone’s right to education is set out unequivocally in international human rights agreements, notably, in the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights (UNDHR) (UN Citation1948)Footnote4 and in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (UN Citation1989)Footnote5. Not only is education central to human flourishing but, as Baker et al. (Citation2004, 141) note, “it is indispensable in achieving other human rights, including the right to economic well-being and good health.”

Schools can make a difference in addressing educational inequality, though other factors that inhibit progress and consolidate the status quo should not be underestimated. Ball, writing from a UK perspective, reports that school effects account for ‘somewhere between 5 and 18% of achievement differences between students, after control for initial differences (Ball Citation2010, 157). He adds, quoting Harris (Citation2009), that “research at classroom level seeking teacher effects tend to establish substantially larger differences than those seeking school effects and attempts to combine school and teacher effects find variations between 15 and 50% depending on the outcome and sample studied.

However, as Reay (Citation2010, 396) crucially observes, “Schools have been held up as both the means of achieving equality in society but also as centrally implicated in the reproduction of inequalities.” Thus, while there is extensive evidence that individual teachers and school teams can make differences in the lives of young people in situations of educational inequality, this does not always happen. This brings us close to our central concern: how do teachers and school leaders working in such contexts see themselves and their situations? Might their reflections and insights offer some pointers as to how other teachers working in the front lines of educational inequality could be supported and sustained? A recent upsurge in attention to “well-being” (DES, Citation2018), including that of teachers, adds further relevance and topicality to our questions.

Schools receive national educational policies in various way. For example, Jeffers (Citation2011) noted how schools succeeded in both embracing and resisting the Transition Year innovation, “domesticating” it to fit their traditions and cultures while rejecting more challenging aspects. Braun, Ball, Maguire and Hoskins (Citation2011, 585) arrived at a similar conclusion in a UK study, noting that “policies are intimately shaped and influenced by school-specific factors”. While respecting differences between schools and how they engage with policies, we wished to discover common threads in how school personnel conceptualise and articulate their individual responses to educational inequalities.

Methodology

With a view to identifying experiences, priorities and meanings associated with working in schools facing the daily challenges of educational inequality, the researchers decided on informal conversational interviews (Cohen, Mannion and Morrison, Citation2000, p. 270) as an appropriate method for data-gathering that would place practitioners’ voices close to the centre of the research. At the same time, we both had prior experience as teachers and school leaders in schools serving “disadvantaged” communities and believed that these experiences would actively assist in conversational clarity and subsequent data analysis (Braun and Clarke, Citation2006, 80). As has been noted, such subjectivity can be a resource rather than a threat to knowledge production (Braun and Clarke Citation2019, 591).

20 research subjects were selected in a purposive and opportunistic manner. As education lecturers and researchers, we know a wide range of school personnel working in challenging contexts and have, over many years, engaged in professional conversations with them about their working situations; we invited some of these to volunteer to take part in the research. While such on-the-ground knowledge of practitioners is a strength, the danger that the informants’ views might not be not sufficiently “representative” is recognised. However, regard the picture developed about working in situations of educational inequality to be reliable and authentic.

Brookfield (Citation1995, 31) emphasises the importance of the autobiographies of learners and teachers as sources of insight into teaching. Too often, he argues, “personal experience is dismissed and demeaned as merely anecdotal – in other words hopelessly subjective and impressionistic”. Merrill and West (Citation2009) contend that biographical perspectives enable researchers to explore the “dynamic interplay” between individuals and their histories, their inner and outer worlds, the self and other. Thus, peoples’ lives are not simply determined by historical and social forces, but interviewees are also seen as active agents constructing their own realities (Berger and Luckman, Citation1967).

Our expectations were modest. One hope was that we might construct what Geertz (Citation1973) calls “thick descriptions” relating to particular school cultures. Another was that some individual reflections might illustrate particular issues in novel ways. We were uncertain as to what themes might be highlighted given the diversity of contexts and the myriad of issues related to working in challenging circumstances. We did not know what theoretical considerations might arise from the data and subsequent analysis.

The data arose from the voices and viewpoints of the interviewees. Each interviewee works as a teacher or school leader in a school that is part of the DEIS scheme (13 teachers, 2 deputy principals and 5 principals). Prior to each face-to-face interview we indicated to the subjects, by email or ‘phone, that we were interested in hearing them talk about their experiences, satisfactions and challenges of working in their particular situations.

Typically, the interview lasted an hour though in some cases was longer. Frequently, interviewees spoke intensely at length about a particular aspect of their reality. Many accounts weaved a way between description, analysis and, strikingly, practical responses and solutions aimed at policy improvement. Often, participants related illustrative “stories”, sometimes about a particular students or incident. These anecdotes often captured, for the interviewees, some central aspects of their situations and made great sense to them. As Aguilar observes:

Words shape how we understand ourselves and make sense of the world. When we weave the scattered facts and moments of our lives into narratives, we give events of our life form, meaning and longevity. Words bring the essence of things into being. Stories tell us who we are and what is possible for us (Aguilar Citation2018).

In reviewing data, we worked through the steps and stages of Reflexive Thematic Analysis as described by Braun and Clark (Citation2006), Braun and Clarke (Citation2019).Footnote6 Firstly, we developed a close familiarity with the data, transcribing the interviews that each of us had conducted, listening to each other’s interpretations of these interviews, and discussing and challenging these interpretations. Next, we labelled identifiable features in the transcripts, a process similar to coding in grounded theory (Glaser Citation1978). Thirdly, working through both surface and latent features of the data, we generated some initial themes. Between the coding and the initial thematic identification, we felt there were far too many strands and so set about combining and discarding, all the time refining our own thinking on the significance of the findings. In keeping with the active and reflexive nature of the process, Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006), fifth step, the defining and naming of themes, continued throughout. We eventually agreed on eight themes and, subsequently, on a ninth, unifying one. The final stage, writing up, made explicit links between the themes and relevant literature and, subsequently, involved revisions with valuable contributions from peer reviewers and a critical friend.

Findings

1. The uniqueness of each school’s context

A striking feature identified in the data concerns context. Interviewees see their own situation as almost unique and are keen to emphasise this. “All of the staff agree that we work in a different type of school. We certainly do not fit into what is termed ‘the national average,” says Evelyn, principal in an inner-city school attended by children from 38 different nationalities in an area where “food poverty, addiction, violence and social unrest” are prominent features. Another principal, Noirín, states: “You can’t separate education from the context in which people are living. Many people in the inner city are so suffocated by their circumstances that they are barely existing”. Interviewees indicate how the range and intensity of challenges not only have to be located in each school’s historical and socio-economic context but, critically, need to be weighed against the strengths and weaknesses of the current teaching team, the quality of leadership and the support of parents. An incident that might escalate into a crisis in one school could be dealt with in an almost matter-of-fact way in another, reflecting variations in cultures and relationships.

Grace, a secondary school teacher, echoes a sentiment many feel: “There is a diversity of needs, cultures, economic disadvantage and some challenging behaviours with the result that I can no longer rely on what has worked in the past.” She describes students with disabilities, a growing number of blended families, varied cultural backgrounds and she stresses the importance of teachers liking their job, being open to learning from students and from colleagues. According to Grace, the context also depends greatly on whether there is co-operation from and with a “visible” principal, student affirmation, collegial trust and effective communication.

Irene, who teachers in a primary school, adds another persistent strand: “Teachers from other schools do not understand the difficulties associated with teaching in our school. They are often surprised when they hear of some of the issues. … . Every school is different and has its own set of problems.”

Sensitivity to school context is highlighted in numerous other studies (e.g. Chapman Citation2004; Lupton Citation2005; Thrupp and Lupton Citation2006; Braun et al. Citation2011; Brennan and MacRuairc Citation2017) and serves as a persistent reminder to both policy makers and practitioners to be wary of simplistic generalisations, that “one size” does not necessarily fit all. This striking emphasis on context – “our situation is unique” – suggests that an appreciation of a school’s history and traditions as well as the circumstances of the students’ lives should be an important part of teachers’ awareness and development, not only when initially appointed but on an ongoing basis. Kelleghan’s (Citation2001) highlighting of economic, cultural and social capital, mentioned earlier, is especially relevant here. There’s a rich body of educational writing on the individual cultures of schools and the ability to “read” a school’s culture appears vital for anyone wishing to make an effective response to educational inequality. Dale and Peterson, (Citation2016, 9) summarise various studies when they assert that:

School cultures are complex webs of traditions and rituals that have been built up over time as teachers, students, parents and administrators work together and deal with crises and accomplishments. Cultural patterns are highly enduring, have a powerful impact on performance, and shape the ways people think, act and feel.

This perspective also suggests that, in addition to following national policies and plans, each school may need to take locally specific measures and initiatives that respond appropriately to the unique circumstances of students, their families and the community in which the school finds itself. Growing regulatory demands on schools can, perhaps unintentionally, inhibit them from developing their own unique responses to local contexts. The observation that “Schools need flexibility in implementing DEIS to best meet the particular needs of targeted students” (DES, Citation2017a, 41) points to some recognition at the policy-making centre of the uniqueness of context. Such flexibility should, one presumes, include adequate time for staff to talk to each other about the challenges the school faces.

2. Tensions and contradictions

Among the interviewees, a strong commitment to social justice, to enhancing young peoples’ life chances, is sometimes accompanied by frustration and disappointment.

Harry describes the primary school where he works as “urban, in an area of economic disadvantage, multi-cultural with a large Special Education Needs (SEN) and English as an Additional Language (EAL) cohorts.” He says that teaching there is “very challenging” but is convinced that he is making “a difference to the lives of the children”, adding that at times he feels powerless. He cites examples of situations where the school has responded appropriately to many difficult incidents but then voices some of his irritation, “I get very discouraged when parents seem to have no interest. I am discouraged when teachers blame the children and when the support offered by services such as CAMHS,Footnote7 Speech and Language Therapy and NEPSFootnote8 are not adequate.”

Orna, after 10 years teaching at second-level, spoke about a class to whom she was a form teacher. “No matter how I tried to manage the class – I pushed and they pulled – nothing seemed to work. By the time the first term was over, I was exhausted,” she explained.

The triggers for frustration and disappointment are numerous, for example, poor attendance, limited academic achievement, strong pastoral concern in tension with academic aspirations, a “distance” between parents and the school, a feeling that the school system is not a “level-playing field”. Some worry that, in relation to academic achievement and acceptable behaviour, there can be a “lowering of expectations”, individually and collectively. Some showed signs of the “self-laceration” that Brookfield (Citation1995) identifies as a tendency among teachers to blame themselves if their students are not learning. While all schools experience some tensions related to different expectations (Ball Citation1997), some informants indicated that the absence of a shared vision among the teachers teaching the same children can be especially frustrating, particularly if there is little or no professional dialogue.

Donna, a Home School Community Liaison teacher, recounts a painful encounter from a retirement event at the school where she worked. “Don’t think you can change anything for the better here,” one of those retiring said to her. “It’s something you don’t forget easily,” remarks Donna. She estimates that as many as seven of the ten retirees were bitter and cynical about the way their careers had ended. Several recently qualified teachers attended the same event, “they came with hope to the school and equipped with knowledge of new ways of teaching.” Donna says, “The contrast between the two groups was stark”. However, she was also aware that much institutional memory was leaving with these retiring teachers. “They knew the families and their concerns and secrets.”

An empathic appreciation of the life of a child living in restricted circumstances generates its own tensions. It’s not that teachers necessarily excuse anti-social behaviour, gang violence or drug peddling but a protective impulse towards the children they teach inclines them towards explanations and understandings that often differ from dominant narratives in society. Some talked about grappling with questions as to what constitutes a “good” teacher in a DEIS context and, here again, a vexing feeling that professional colleagues working in “mainstream schooling” and in State educational agencies have a limited grasp of the realities of working in disadvantaged environments was evident.

Barbara’s interview is particularly revealing. With a strong commitment to social justice, she very consciously applied for a job in a school designated as “disadvantaged”. “I remember I wore pink stilettoes with a floral pattern to the interview,” recalls Barbara. “I wanted to make a statement about the possibility of combining a love of life and a real need to influence positively the lives of the young people as they pass through our schools.” However, having been offered the job, she realised she had underestimated the challenges. She was shocked by “the students’ limited vocabulary and disrespect for teachers and education generally.” She continues: “The standard of the ‘best’ students was below even the most challenged students in my former school.” Barbara describes how she gradually acclimatised to the situation, stating that this was helped by “a brilliant staff” with great commitment to students’ welfare. Her initial shock gave way to more nuanced insights. “I noticed the complete acceptance of gay students, transgender students and students with disabilities. I realised that our school is truly inclusive”, she says.

The concept of habitus, popularised by Bourdieu (Citation1998), can illuminate some of the bases of tensions and contradictions. Habitus refers to the deeply ingrained habits, dispositions, behaviours and worldviews associated with particular groups. Teaching tends to be dominated by people with a habitus that can differ from the habitus of their “disadvantaged” students, thus generating tensions and clashes. The concept of “cultural capital” (Bourdieu Citation1984) – including family background, accent, educational experiences, preferences etc – may also be useful in understanding the origins of these tensions and contradictions. In such explorations, the warning that a deterministic, almost fatalistic, view can lead to a downplaying of the power of individual or institutional agency is particularly relevant.

Addressing the tensions and contradictions in a school in a collegial manner contrasts starkly with an isolated, individualist and competitive model of teaching. However, teamwork, with attention to shared goals and frank conversations, while at times difficult and time consuming, can be professionally rewarding and organisationally effective (Katzenbach and Smith Citation2015),

Visser and Rayner point to a need to explore “failure” and its impact of all the players in a school. Students don’t like “failure”. When teachers – often “achievers” who rarely failed at examinations – encounter under-achieving students, unfamiliar emotions can be sparked. When students are regarded as “failing” in the system, parents also experience frustration. This may lead them to project this onto someone else. Parents may come into school shouting that teachers “should know what to do with their child in the classroom”. In turn, teachers can also feel they are failing and turn their anger to the system, the curriculum, other agencies, even the child’s family or the child herself/himself. In the middle of these chaotic emotions, the student, with a deep sense of failure, may shout at everyone involved, or “shout” through disruptive behaviour (Visser and Rayner Citation1999).

Grey and Panter (Citation2000, 5) state that “Difficult pupil behaviour challenges teacher confidence and self-esteem”. They add that “Exclusion is less likely where teachers feel supported and have access to a range of skills.” Support to assist teachers explore and clarify their multi-faceted identities (Day et al. Citation2006) may be especially important for those working in challenging circumstances. The Code of Professional Conduct for Teachers (Teaching Council Citation2016) with a focus on respect, care, integrity and trust, offers one route for such consideration. When this takes place at the level of the individual school it can be especially effective because, as Lieberman and Miller (Citation1999, 62) assert, “professional learning is most powerful, long lasting, and sustainable when it occurs as a result of one’s being a member of a group of colleagues who struggle together to plan for a given group of students, replacing the traditional isolation of teachers from one another.”

3. Turning Up – Attendance is a persistent concern

Teachers report erratic student attendance as particularly frustrating. Attendance is seen as a clear, measurable indicator of participation in schooling, though physical presence is not always a guarantee of engagement in learning.Footnote9 While there can be an appreciation of how difficult family circumstances can impact on school attendance, teachers observe that students can develop casual attitudes to attendance. In turn, teachers almost inevitably begin to lower their expectations about having a “full” class. Jack, working in an inner-city all-girls secondary school, says, in some frustration, “There seems to be an attitude amongst teachers that if the students turn up to school and engage peripherally while keeping the rules, then this is all we should ask.”

Experienced principals among the interviewees explain that improving school attendance patterns is a complex issue, demanding a range of interventions. Marian, with more than three decades experience of working in a DEIS secondary school, 10 as principal, roots many of her comments around a simple principle for effective teaching: “Get to know the kids, their lives, their needs.” She continues, “Many students arrive in our school with modest expectations, especially about possible academic achievements,” she says. “Sometimes their pastoral needs are very evident so one of our challenges is to strike the right balance between pastoral and academic support. One way we have found helpful, based on a lot of data gathering, is to identify particular targets. When they come in in first year, it’s Mol an ÓigeFootnote10 and setting targets.”

Highlighting motivation, enabling young people and their parents to see the purpose and possibilities of schooling, can impact on attendance. Frances recounted how, shortly after being appointed as principal in a second-level school, she noted that in the previous year more than 200 students had more than 20 days absenteeism, 70% of which were unexplained. There had been 65 suspensions.Footnote11 When she asked teachers for the reasons for this, their responses tended towards blaming parents, poverty, disadvantage, lack of effort etc. Frances devised a questionnaire which was completed by 42 of the most “at risk” students. While a majority regarded education as “important” and almost all had a positive relationship with one teacher, the rest of the results “made stark reading,” Based on feedback from students, a series of initiatives followed. These included more “mixed-ability” classes, less “ghettoisation” of students with special educational needs, more differentiation in teaching, a shift to a positive more pastoral behaviour code with a ladder of referral, mentoring of students who were struggling, the introduction of restorative justice, training senior students to “buddy” junior ones to counteract bullying, provision of more activities during lunch time, after school support in literacy and numeracy, a points based reward system recognising improvements in individual attendance records and more. In the following year, absenteeism dropped, particularly among those missing more than 20 days; the atmosphere calmed, there was a 10% increase in the students progressing to third-level studies, and relationships between staff and students were regarded as much improved.

Poor attendance by students is often a visible indicator and symptom of underlying problems. As suggested to many interviewees, addressing poor attendance is complex and requires multi-faceted responses; the term “whole-school” can be over-used in discourses about challenges facing schools but in relation to attendance seems appropriate. This resonates strongly with a sensitivity to school context, an appreciation of parents’ and teachers’ underlying assumptions and expectations and imaginative school leadership.

In their study of truancy in Irish secondary schools, Dermody, McCoy and Smyth (Citation2008) found that students from professional backgrounds are significantly less likely to skip classes than their working-class counterparts’. Linking class and educational outcomes and highlighting individual and institutional habitus, they suggest that truancy may serve as a form of resistance to school.Footnote12 Within the DEIS scheme, the School Completion Programme is a central feature; it focuses on attendance, participation and retention.Footnote13

4. The unseen ugliness of inequality and poverty

Poverty is not pretty. Teachers sensitive to the circumstances in which their students live often remark on the ugliness of deprivation. This theme is strongly present in both surface and latent ways in the data. Interviewees share many anecdotes about how harsh life outside school can be for some students. Stories of engagement with petty and organised crime, particularly theft and drug related activities, are interlaced with issues of attendance, misbehaviour, curriculum and pedagogy. In addition, the situations are exacerbated when various specific impediments to learning, diagnosed and undiagnosed conditions, are more concentrated in schools in the DEIS scheme.

Annette, a principal at second-level, prefaced her remarks with a reminder of the fundamental issue of poverty: “The people in this community are the salt of the earth. But they don’t have much money. The school, even though we are in the DEIS scheme, doesn’t have much money … . a. school is counter-cultural to much of what is presented to young people in a disadvantaged community.”

Barbara recounts in graphic detail an early visit to a student’s home. Front and back gardens were “full of rubbish”. Inside, a cloying smell seemed to permeate everything. Skirting boards and door jambs had been used as firewood. After a brief conversation with the mother of a student, she left quickly. “On the way back to school I was physically sick at the side of the road,” she recalls. Barbara adds that this defining visit helped her appreciate her own upbringing more. She believes that appreciating students’ backgrounds has given her a more understanding attitude to verbal abuse and aggression which students sometimes display.

Noirín, principal of an inner-city school, sees families “so suffocated by their circumstances that they are barely existing.” She talks about the impact of the local environment – including mental health issues, gangs, joyriders, drug abuse, even murders – on children in classrooms. Noirín warns against generalisations, pointing out how, in terms of both poverty and attitudes to school, she observes significant variations. “Some migrant families are very ambitious for their children to achieve educationally,” she says, contrasting such ambition with different expectations in families struggling with the legacy of inter-generational poverty and unemployment. “Others (migrant families) are overcome by trauma and poverty,” she adds.

The ideal of schools as beacons contrasting with the dark and murky conditions in which some students live is attractive but, as much of the evidence underlines, very different worlds and value systems can clash within schools and generate further tensions for teachers as well as students.

Paradoxically, accounts of the ugliness of inequality are sometimes juxtaposed with anecdotes of young people’s resilience. Interviewees report how some school-going children carry massive burdens of responsibilities within their family contexts. Donna, a primary school teacher, for example, recalls a recent conversation with a student about her parents. Her father regularly beat her mother who finally went to a women’s refuge taking her five children with her. Now the father follows them around, looking for an opportunity to smash the car or terrify the mother and the children. Donna describes the student as “like a sensible old lady”, trying to reason with her father and point out to him the consequence of his actions. This student is eleven years old.

For some, the attendance issue and the ugliness of poverty can lead to verbalising frustration and even a lack of solidarity with what they perceive as their fellow-teachers who work in more “mainstream” schools not appearing to have much appreciation of the challenges they face in the schools where they work. They point, in particular, to the unseen ugliness of poverty and its manifestation in classrooms as stark and at times brutal. One antidote to such ugliness can be the cultivation by the school of beauty, in art, music, nature and relationships.

5. Lack of continuity

A higher turnover of staff in schools serving poorer districts is a persistent theme in the international literature (Carver-Thomas and Darling Hammond, Citation2017; OECD Citation2018).

Donna remarks that “There is constant change of staff in the school.” She has observed a high number of newly-qualified teachers (NQTs) spending a short time in the school before moving elsewhere. In Donna’s opinion, these NQTs are not sufficiently prepared for dealing with their context “when the community outside the school seem to blatantly disregard the values that we as teachers hold dear”. She contends that teachers need “to interrogate our own deeply held beliefs about our responsibilities to those who are human and broken.” She believes that if this capability could be nourished more, it could reduce high staff turnover.

For a variety of reasons, teachers working at the frontline of educational inequality can be drawn towards alternative employment. Orna’s case is instructive. A teacher at second-level, she pinpoints a long conversation between herself, her sister and two teacher colleagues during a mid-term break and her sister’s follow-up phone call and concern. Following the fifth call enquiring about her wellbeing, Orna replied, “I’m fine, why do you keep calling me?” Her sister’s response still resonates: “It’s not the stories of being called ‘cunt’ and told to ‘go fuck yourself’ every day that is concerning me, it’s the fact that you have accepted it as a normal part of a day’s work; it’s not normal!” Despite feeling a strong affiliation with the students she had taught for seven years, Orna felt alienated when parents supported their unruly children “threatening to beat you up”. Critically, neither did she feel supported by the leadership team in the school. “Most days I drove home from work crying. I was depressed and it was beginning to have a detrimental effect on my health. It also affected my family watching me so unhappy and stressed. I was almost at breaking point.”

“I was on the verge of quitting teaching but thankfully found a job in a different school. Now my passion for teaching has been reignited but I am concerned about a lot of teachers who still work in horrendous circumstances.” Especially striking about Orna’s case is her obvious commitment and competence alongside the gradual erosion of her confidence and self-esteem.

Una, with a background working in Information Technology prior to qualifying as a second-level teacher, is also frank about her experiences in an inner-city DEIS school. “I had to leave this school in order to preserve myself from undue stress and fatigue. There was constant shouting by staff and arguments on corridors. Students picked up on the stress and, of course, this gave rise to sudden outbursts in the classrooms. Students would throw things at the white-board and then the teacher would be the focus of attention.” Una also points to other colleagues with much to offer, who moved to other schools.

Teresa, also working at second-level, with a background working in the pharmaceutical industry and teaching in England, states that: “I often ask myself why I stay in this school.” She explains: “Our school is slowly falling apart. This applies to the physical building but also to the decrease in the numbers enrolling and staff morale … . The building contrasts negatively with other schools within driving distance; schools that can ask for and receive donations from parents … . I struggle to reconcile my professional aims and objectives when they are stymied by the social and financial reality of the context in which I teach … I dream of being in a school that will help me achieve my potential as an outstanding teacher.”

Statistical data about turnover rates of staff in Irish schools are elusive but perceptions of a lack of continuity in the DEIS scheme are widespread. While acknowledging the positive impact of “new blood” to teaching teams, most school leaders interviewed point to the importance of teachers who have years of experience of the school and its specific context. Some cited the relatively large numbers of retiring teachers in 2012Footnote14 as especially disruptive with extensive “institutional memory” being lost. The value of a teacher with, say, twenty years’ experience working in a disadvantaged context, is inestimable; reputations and trust can take years to build; unique insights into intergenerational trends and patterns in a particular community can be taken for granted, a community’s “faith” in a school is frequently based on familiarity with and belief in particular teachers. These observations underline how critical maintaining teachers’ sense of well-being is in challenging circumstances. Once again, shared visions, purposeful leadership, cultures of respect, collegial support and relevant CPD appear to be crucial. In the review of DEIS, the DES (Citation2017a, 41) noted that several submissions reported a large turnover of staff in DEIS schools and emphasised the need for this to be addressed.Footnote15

Many factors can interact in contributing to teachers leaving a school. In their review of six studies of high teacher turnover in US “high-poverty” schools, Simon and Johnson (Citation2015) suggest that teachers who leave are not fleeing their students. Rather they are leaving the poor working conditions that make it difficult for them to teach and for students to learn. They add that the working conditions that teachers prize most–and those that best predict their satisfaction and retention–are social in nature and include school leadership, collegial relations and elements of school culture.

6. Parents’ expectations

Discussion of issues such as attendance, anti-social behaviour and low expectations frequently lead to comments about the role of parents and often illustrate a tension between parents’ and teachers’ expectations of schooling. “I try to keep my own expectations high but there is so little support and understanding from home that this is very difficult”, remarks Irene, working in a DEIS Band 2 primary school.

Some interviewees offer partial explanations for the perceived differences. Charlie, deputy principal in a second-level school, remembers one potent exchange with a parent. “She told me that the road into the school is the longest avenue in (names locality) … . because you never know what surprises lie at the end of it’, adding ‘they’re usually bad ones’.”

Some parents’ own negative experience of schooling, understandably, can contribute to a hesitancy to trust schools. Limited attendance at parent-teacher meetings or at parents’ association gatherings are not only disheartening for teachers but have consequences for students, including their career aspirations, academic progress and general well-being. Evelyn, principal of a second-level school, observes that some parents “do not understand the system and fear failure.”

Charlie points to the practice of suspending students from school as offering opportunities for dialogue with parents. In following the principles of restorative justice,Footnote16 the school where he works has developed a system where, before any suspension, the leadership “talk matters out with the parents.” The suspension policy had been worked out with students and is closely linked to a positive emphasis on good behaviour.

Lauren, a deputy-principal at second-level, suggests that parents with high aspirations for their children sometimes shy away from schools in the DEIS scheme. She says:

I know the newspapers say they are not “league tables” but those lists of transfer rates to 3rd level have a terrible effect on schools like ours. There is a lot of damage done by the casual labelling of schools, even that term DEIS has some very negative connotations. We have some fantastic teachers in our school but some parents think their children will be better off in a different school because they perceive it as more “academic”. It’s hard to fight against such perceptions because they reflect such a narrow view of education and growing up.

Such comments remind us that not all children from poorer families attend DEIS schools and that this reality prompts questions well beyond the scope of this paper.

Primary school teacher Harry talks positively about the school where he works as having students from families whose aspirations stretch from completing primary school to attending university courses. “Some children are from dysfunctional families … There are issues with alcohol and drug abuse and unemployment. Some parents have special needs themselves … Other parents, who hated school, seem to place no value on education. Harry cites one child who attended “the gifted children classes” in a nearby university at weekends but notes that “the majority find it a struggle to come to school.”

Harry cites incidents of parents under the influence of alcohol demanding access to his classroom, dealing with the consequences of suicide on families, the dynamics resulting from a heady mix of children for whom English is an additional language (EAL), those diagnosed with ADHD, severe emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD), bi-polar disorders, depression, dyslexia, and dyspraxia and so on.

These conditions, he says, all impact on parental expectations. As he sees it, clear vision and policies as well as strong teacher self-awareness promote collaboration, good communication, shared leadership, goodwill and well-being.

While mixed parental expectations are mentioned in most interviews, teachers vary in how they regard this. Irene contends that the inclusion of SEN and EAL students, combined with unexpected interruptions and outbursts has led her to realise the importance of kindness and encouragement. “Differentiation is important but targets must be realistic,” she says.

Research stretching back to the Plowden Report (Citation1967) has tended to emphasise the relative influence of the home as distinct from the school on learning outcomes. But, as Epstein (Citation2002) and others have shown, home-school relationships are complex and, if school effects account for between 20–40% (Emerson et al. Citation2012) – slightly higher than the figure quoted from Ball et al (201) earlier – it is important for schools to look closely at the patterns of school-home relationships. According to Hanafin and Lynch (Citation2002, 36) “the voices of parents of educationally disadvantaged pupils are unheard”. In another Irish study, Doyle and Keane, reporting on attitudes among parents in a local authority housing estate experiencing significant marginalisation, note the strong sense of being “let down by school”. “Parents emphasised that they and their children had been treated negatively relative to other pupils by teachers and school management due to being from this particular area.” (Doyle and Keane Citation2019, 77). Many of our interviewees spoke of efforts to engage with parents. If parents’ schooling experiences were predominantly negative, then listening, understanding and acknowledging this may be a vital first step among teachers and school leaders. Open engagement with parents about local possibilities can lead to some of the creative, school-specific initiatives mentioned earlier. Enabling parents to feel that they are genuine partners and stakeholders in the educational process seems to be both significant and challenging. Evidence from Byrne and Smyth’s (Citation2010) study of early school leaving, suggests that schools should engage positively with the parents of working-class boys, Traveller children and newcomer (immigrant) children as priorities. Conaty’s (Citation2002) account of developing home-school-community liaison links maps some possibilities clearly and concretely.Footnote17

Freedom for parents “to choose” a particular school is a long-established tradition. However, in an unregulated market environment, some schools can be predatory in their efforts to attract certain students and exclude others. As Tormey (Citation2007, 194) notes it may be that because of the capacity of education to enable people to access wealth and resources in later life ensures that those who have an advantage will use the resources at their disposal to ensure their advantage is continued. Primary schools and primary school teachers can also get sucked into an apparent competitive situation, mistakenly seeing the “placing” of their students in school B (rather than the local School A) as a positive achievement. The consequences of all this for schools in the DEIS scheme can be that some of the more academically promising students in a neighbourhood attend school elsewhere, leaving local schools to deal with an even greater concentration of educational disadvantage. Because of the way many schools have operated in the past, practices of selection and discrimination often seem to be accepted as “normal” in our educational culture. Faced with such realities, teachers and school leaders often experience tensions between their valuing of inclusion and acceptance and the need to “market” the school so that such values are not perceived as having a negative impact of enrolment. It is too early to see whether new admissions legislationFootnote18 will be effective in changing practice or, whether the contention that “The educated middle class, who are primarily in control of schooling, whether consciously or not, consistently arrange school structures to benefit children of their class” (Brantlinger Citation2003, 189) will persist. This is a complex issue that deserves greater attention.Footnote19

7. Teachers’ expectations

As evident in earlier comments, individual teachers talked about how they had adjusted their own expectations over time. Expending extensive energy on managing student behaviour can make it more difficult for teachers to maintain a focus on the formal curriculum. Interviewees suggest that lowering expectations of what students might achieve is an almost inevitable consequence for some teachers.

Kate, a secondary school teacher, remarks: “I often think that students with special educational needs – who might come from families with few expectations – are very poorly served by much of the official curriculum which doesn’t suit their needs.”

Lauren puts expectations in a different way:

We need to look more closely at recognising – not limiting – young people’s potential and then take appropriate action to help them realise that potential. For example, one phrase I hate to hear teachers using is “Our students would never be able to do that … .” That’s defeatist. If teachers begin sentences stating what young people can’t do, it’s very likely they won’t do it, whatever it is.

Lauren adds that there is a lot of social change taking place and schools are “at the frontline in how disadvantage impacts on children.” She would like more public discussion about such matters.

Donna questions homework policies in the context of children whose families have been made homeless and are living in hotel rooms where parents find it difficult to wash school uniforms. This resonates with the findings in a study of the educational needs of children experiencing homelessness and living in emergency accommodation (Scanlon and McKenna Citation2018).

Charlie, himself one of the first students from a particular DEIS school to attend university, points to staffroom discourse as often revealing of teachers’ attitudes:

I remember as a student teacher overhearing a group of teachers in the staffroom giving out about “these kids”. It was a kind of casual disrespect. Five years earlier it could have been me they were talking about. It’s frustrating when you see this evidence of how teachers talk about their own students.

While some unprofessional talk probably occurs in all schools, it can be particularly problematic when it goes unchallenged.

Some studies conclude that not only are teachers good at forecasting student outcomes but “that they can also influence outcomes by becoming self-fulfilling prophecies” (Gershenson and Papageorge Citation2018). This is not necessarily a positive. The authors of a study that looked at young people from disadvantaged backgrounds who progressed to an elite university, contend that in environments where ability and investment in education are seen negatively, young people’s engagement with learning may not be so visible and if such complexities are not recognised “teachers may perceive students who are otherwise academically engaged as apathetic or disengaged, misjudge their academic potential and predict them lower grades than they achieve as a result” (Thiele et al, Citation2017, p.65).

Diamond, Randolph and Spillane (Citation2004), go beyond the evidence of a levelling off of teachers’ expectations as they connect expectations with teachers’ sense of responsibility for students’ learning but also with what they refer to as the organisational habitus, “class-based dispositions, perceptions, and appreciations transmitted to individuals in a common organizational culture” (Horvat and Antonio Citation1999, 320). Rather than see a lowering of expectations as inevitable in challenging schools, Diamond et al. contend that deliberate action can redirect a school’s organisational habitus to raise expectations. Critical to such redirection are actions by a school’s leaders.

Many interviewees mention the confluence of pressures that can lead to a lowering of expectations over time: difficulties with attendance, interest, attention, engagement, homework, group achievement can cumulatively, over time, lead to motivational attrition, even among the most enthusiastic teachers. Some studies suggest that teachers working in “disadvantaged” situations need to think “big” and differently. Gardner’s (Citation1984, Citation2006) work on multiple intelligences and Dweck’s (Citation2007) emphasis on growth mindsets may be relevant. Farrington et al suggest that, as well as academic and cognitive skills, “Non-cognitive factors such as motivation, time management, and self-regulation are critical for later life outcomes, including success in the labour market” (Farrington et al. Citation2012) with implications with how teachers and schools see their roles. This loops back to Kelleghan’s (Citation2001) reference to economic, cultural and social capital.

We are acutely conscious that a positive school culture, where teachers’ morale remains high, where teachers and students feel valued both as individuals and as part of a wider collective, and where those encountering difficulties are supported, can be especially challenging to maintain.

8. The quality of leadership

School leadership, sometimes referred to by interviewees as “management”, features strongly throughout the transcripts, in both positive and negative ways, as a critical factor in how schools respond to social and educational inequality.

Una, quoted earlier in relation to teachers moving on from teaching in DEIS schools, recalls working in a context where student behaviour was “unacceptable”. She says that “management seemed to turn a blind eye.” Frustrated, she asks: “How can teachers teach well if they are working in this kind of environment? How can students be subjected to this perverse learning environment?” Una states that it was with regret that she left that school but “it was affecting my ability to function well as a teacher and also as a wife and mother.” She moved to another DEIS school where there was “a high-quality leadership team” of principal, deputy-principal and other post-holders. “There is a culture of absolute respect on corridors and in classrooms,” she says, adding that there is no guarantee that this will be maintained. Orna, also quoted earlier, cites “lack of support from management” as a major factor in considering quitting teaching.

When Patrick initially began work as a substitute teacher, he was shocked. “When I saw the fencing and the security cameras, I dreaded what I would meet in the school itself. I took the position as it offered me some teaching hours. I didn’t really choose to work there. But I was pleasantly surprised by the great culture within the school. Most impressive were the processes and procedures embedded by a pro-active school management and led by the principal,” he says. Patrick now works as a Behaviour for Learning teacher with intensive support from the National Behaviour Support Service (NBSS).Footnote20 He speaks of the challenges of out-of-control behaviour, flash points of anger, disrespectful language among students and how emotional difficulties, anxiety and stress are barriers to learning.

Patrick senses contradictions between teachers committed to offering multiple supports to young people and leaders whose concerns and priorities seem elsewhere. He contrasts, for example, rhetoric about student well-being with an inclination to use expulsion as an early rather than a last resort.

Lack of continuity in leadership can have negative effects. Stephen, a secondary school teacher of Maths and PE, mentions, in passing, that the school where he works had four principals in as many years. He observes a big difference between someone who falls, almost accidentally, into a leadership position nearing retirement and another who sees the role as a stepping stone to career progression. On the other hand, he adds, some are very driven, “doing the right thing for the school and the community.”

The school leaders interviewed articulate a range of views that capture many of the tensions mentioned above. The metaphor “walking a tightrope” was mentioned more than once. Evelyn emphasises the importance of seeing each student as an individual. “Difficulties arise,” she says, “when teachers do not take the time to get to know the school’s context.” She adds: “Some relatives of an individual student may be incarcerated or have a criminal record but we see the child/student who has not been in trouble with the law.” Evelyn continually returns to the importance of positivity, encouragement and affirmation of students and teachers and a refusal to give in to negativity. She leads by example.

Annette recounts an incident when, as a newly appointed principal, she met a “wave of aggression” at her first staff meeting with a teacher wanting to know how she was going to address “the crisis in discipline”. “I mumbled something about ‘reading myself into the job’ but it reminded me not to expect a ‘honeymoon’ period”. Annette recognised that this teacher was very frustrated. “At every opportunity, I tried to listen,” she says. “Whenever the teacher called to the office with complaints, I asked for suggestions.”

Annette has strong views on confidentiality. “Some teachers can be very casual and unprofessional in what they say about the students they teach,” she says. Annette believes that leaders need to challenge such unprofessional talk. She continues, “as regards discipline, the temptation is to think there are quick fixes. You have to tackle it at many levels.”

Teachers who move into formal leadership positions can be surprised by what they discover. Charlie having taught in a DEIS school for 16 years, remarks: “I thought I knew a lot. But when I moved to another DEIS school as Deputy Principal my eyes were opened. Firstly, I saw how well the school leadership protected the staff from ugly issues so they could concentrate on teaching and learning. Secondly, I realised that students are easier to manage than adults. Thirdly, because I have this role, many people presume I have the answers to their problems. Scary!”

Lauren identifies some particular challenges for leaders in DEIS schools. She dislikes status issues associated with the classes one teaches. She perceives an undervaluing of those who work with young people with special educational needs and an elevated status for those teaching Leaving Certificate classes. Lauren relates a story about Comenius project that involved linking with a school in Denmark. “We were all struck by the way they all accepted that the most qualified teachers, the ‘best’ ones, should work with the most vulnerable students.”. In Lauren’s case this experience has had a direct impact “on how we do the school timetable.”

Lauren develops the point by noting mixed attitudes to the school offering the LCA (Leaving Certificate Applied) programme.Footnote21 “This is regarded by some as reflecting badly on the school rather than acknowledging that we are trying to respond to diversity, to the children who present at the door. At times, it feels like our school is punished for doing its job well.”

Lauren, who operates an open-door policy, warns against generalising about how teachers respond to working in challenging circumstances. “Of the ones who call into my office, some cry, some shout and some say almost nothing. I worry most about the latter group”, she says.

Marian, the most experienced school leader interviewed, believes a major priority for schools should be “happy children”, acknowledging this is not easily measured. She links this with appreciation of context, respect for individuals and their families, a focus on nurturing the individual strengths of students and staff, and on developing resilience. For Marian, “happy children” is not an empty slogan; the range of issues students are dealing with is “an ongoing concern”. She estimates that at least 20% of Leaving Certificate students are dealing with serious mental health issues, with some self-harming. Marian believes that a strong guidance and counselling service is vital. A room, staffed by teachers, where students can “cool down” complements anger management interventions. Support the school gets from the National Behaviour Support Service (NBSS) makes a crucial difference.

Insights into school leadership generally tend to be especially relevant when responding to inequality. Realising that “shaping school culture is a key leadership task” (Schien Citation1985; Fullan Citation2001; Dale and Peterson Citation2016) is rich in possibility. Furthermore, Flintham (Citation2002, 2) proposed that successful school leaders act as the “external reservoir of hope” for the institution, preserving its collective self-belief and directional focus against the pressure of events. School leaders also maintain and sustain an internal “personal reservoir of hope” (the phrase is attributed to John West-Burnham), the calm centre at the heart of the individual leader from which their values and vision flow and which continues to enable effective interpersonal engagement and sustainability of personal self-belief in the face of not only day-to-day pressures but critical incidents in the life of the school. This challenge, amid hectic, fast-paced, and unpredictable demands, should not be underestimated. The review of DEIS (Department of Education and Skills Citation2017a, 53) does note that various evaluations of schools have highlighted that where good school leadership was in evidence, the school climate was better, planning was more effective and the learning and other outcomes were more favourable.

Leadership and vision are inextricably linked. Barth proposes:

The vision is, first, that the school will be a community, a place full of adults and youngsters who care about, look after, and root for one another and who work together for the good of the whole, in times of need and times of celebration. Every member of a community holds some responsibility for the welfare of every other (person) and for the welfare of the community as a whole (Barth Citation2002, 11).

Terms such as “community”. “collegiality” and “collaboration” can be sometimes dismissed as “woolly”, “vague” and ignoring the reality that classroom teaching is a highly individual, autonomous activity. However, as Lortie (Citation1975) remarked, one teacher’s autonomy can be another’s isolation. Miller (Citation2003, 17) argued that the adverse effects on a teacher of a child or young person with challenging behaviour “should not be underestimated” as teachers may feel “defeated, less competent than colleagues, or exhausted” and as result, “have little or no sympathy for a pupil who has made their life a misery.” This may lead to generating much evidence of failed interventions building and reinforcing a negative picture of the pupil. It has also been noted, rather pessimistically, that in some instances when successful strategies are identified by individual teachers, they don’t pass on this information to colleagues experiencing similar difficulties. The growing literature on trauma informed practice in education (e.g. Cavanaugh Citation2016) is particularly relevant for schools dealing with educational inequality.

Discussion

The existing evidence, nationally and internationally, point to strong negative correlations between most measures of “disadvantage” and educational achievement. However, this should not translate into a pessimistic, paralysed or deterministic view that little can be done to improve the experience of young people in schools in challenging circumstances; the capacity of schools to make a difference should not be underestimated (Harris et al. Citation2006, 11).

Listening to the perspectives of 20 teachers and principals led to the identification of eight themes, interrelated and overlapping, which offer a framework for schools responding to situations of educational inequality. Without ignoring the contributing of external factors to educational inequality, many of our informants highlight how school-specific actions can enrich responses.

The themes illustrate how teaching in challenging situations can involve high levels of both positive and negative emotions. A sense of “making a difference” is often accompanied by feelings of frustration and disappointment. Pendular swings in mood and climate can occur throughout the school year, sometimes with major highs and lows in a single day. The evidence reminds us that teaching and learning are emotional practices, not solely so but, nonetheless, irretrievably emotional (Hargreaves Citation2001).

Heightened awareness of the emotional dimension of the work can be an important step in maintaining a sustained response to the challenges. In particular, nurturing and cultivating positive relationships appears critical.

Fullan (Citation2001, 51) contends that, in a successful enterprise, “it is actually the relationships that make the difference”. In reviewing the data, codes and themes through the reflexive thematic analysis process, we regard “Relationships” as a unifying central thread. That said, Fullan’s (Citation2001, 65) warning that “Relationships are powerful, which means they can also be powerfully wrong” is especially relevant.

A non-exhaustive list of relationship categories serves as a guide of what needs to be addressed but also draws attention to the multiplicity and complexity of the issues:

teacher – student relationships

student – pupil relationships

teacher – teacher relationships

teacher – parents relationships

students and teachers – subject knowledge relationships

school leaders – teacher relationships

school leaders – student relationships

school leaders – parents relationships

school leaders – community relationships

teacher – special needs assistants (SNAs) or Inclusion Support Assistants (ISAs)

teachers – other school staff relationships

school – community organisations relationships

school – neighbouring school relationships

teachers in one school – teachers in other schools

A focus on school-related relationships can also integrate the insights of Noddings (Citation2006) on care, Johnson and Johnson (Citation1989) on collaborative learning, Hargreaves and O’Connor (Citation2018) on teacher collaboration, Fullan (Citation2001) on leadership, Epstein on parents (Citation2002), Zehr (Citation2015) on restorative justice, Bingham and Sidorkin (Citation2004) and Griffiths et al. (Citation2015) on relationships themselves in education as well as the extensive recent emphases on “wellbeing” (e.g. Burke and Minton Citation2019).

Interrogating relationships through Kellmer-Pringle’s (Citation1974) focus on children’s needs for love, security, new experiences, praise and recognition and responsibility can illuminate how relationships can have positive and negative dimensions. An awareness of the negative dimension of relationships, especially is “disadvantaged” contexts, should dispel any notions that it is a “soft” or “woolly” notion. With some children, a key challenge for a school is to offer positive educational experiences to counter the negative relationships that may dominate their lives. In their nationwide survey, Dooley, Fitzgerald, O’Connor and O’Reilly (2019) link young people’s relationships with their mental health and highlight the importance of the availability of one good adult in their lives, findings with obvious implications for schools.

If we see teaching in relational terms, it should not be an excuse to dilute engagement with content knowledge. Pedagogical relationships should build on students’ interests and strengths to forge connections with relevant subject knowledge. This is much more likely to take place when the relationships are open to listening to students, learning about their backgrounds and contexts, and informed by the spirit of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, especially articles, 3, 12, 28 and 29 (UN Citation1989; Lundy Citation2007; Fleming Citation2015).

Teacher-teacher relationships also require closer exploration. Katzenbach and Smith’s (Citation2015) analysis of teamwork provides some useful pointers to positive teacher-teacher relationships. They emphasise the importance of agreed specific performance goals, common way of working and ensuring that team members are mutually accountable for their performance. The resonances with the earlier reference to Lieberman and Miller’s (Citation1999) point about collegial professional development are clear. Foundational to all of this is an emphasis on support for teachers at an emotional level, helping them manage stress and cultivate resilience.

Conclusion

Within the context of schools facing significant challenges arising from an unequal society, the contention in this paper is that, in being attentive to the eight themes identified from the data, staff might use “relationships” as both a lens through which each theme can be assessed and as a way of focusing on improvement. This framework, we believe, offers schools a realistic and manageable structure around which professional conversations can be initiated, cultivated and developed to evaluate practice, and to deepen understandings of educational disadvantage. This eventual shared understanding might then be used to further develop a school’s mission statement so that it is exquisitely sensitive to its current context. In turn, this might lead to a fine-tuning of the professional development needs of teams and individuals .

This perspective views staff professional development not only as an individual pursuit but as a collective activity, thus including all staff in the school not solely teachers. The transfer of the positive relationships so nurtured should, ideally, transfer into students’ relationships with each other. Overall, such conversations and developments would progress the equity that all students deserve.

While the thematic analysis from data gathered from 20 practitioners led to eight major themes and a subsequent unifying one, the researchers acknowledge that the codes and themes might have been configured differently (Braun and Clark Citation2006; Braun and Clarke Citation2019). However, we think that the proposed framework is sufficiently inclusive to enable practitioners working in an individual school, in clusters of schools, in teacher education programmes or from within the system, to initiate purposeful conversations about their response to educational inequality.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gerry Jeffers

Gerry Jeffers has worked as a teacher, guidance counsellor and deputy principal in schools in Ireland and Kenya. He was national co-ordinator of the Transition Year Curriculum Support Service prior to becoming a lecturer in Education at Maynooth University in 2000. Recent books include “Transition Year in Action” (Liffey Press, 2015) which has been translated into Korean and ‘Clear Vision, The Life and Legacy of Noel Clear, Social Justice Champion 1937-2003 (Veritas, 2017).

Carmel Lillis is a former school principal. She has taught in challenging school environments throughout her career. Having trained as a coach, she now facilitates seminars and workshops for current and aspiring school leaders.

Notes

1. The DEIS (Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools) scheme is the main policy initiative of the Department of Education and Skills to tackle educational disadvantage. First introduced in 2005, it includes a system for identifying and regularly reviewing levels of disadvantage in schools and a programme to support schools with high levels of disadvantage. About 20% of all schools in the Republic of Ireland are in the scheme (Smyth, McCoy, and Kingston Citation2015; Kavanagh and Weir Citation2018; Department of Education and Science Citation2005a, Citation2005b, Citation2016, 1017a, Citation2017b)

2. By themes we refer to patterns of shared meaning underpinned or united by a core concept to emphasise a uniting idea (Braun and Clarke Citation2019, 593).

3. This important policy document proposed “equality” as one of five “educational principles” that should underpin policy. The other four were pluralism, partnership, quality and accountability

4. In particular, see article 26.

5. In particular, see articles 3, 12, 28 and 29.

6. In addition to the (Braun and Clark’s Citation2006) article, we were also informed by subsequent insights into Reflexive Thematic Analysis as set out on their website https://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/thematic-analysis.html

7. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.

8. National Educational Psychological Service.

9. In recent years schools have been obliged to report school absences regularly to the Child and Family Agency (Tusla). See https://www.tusla.ie/tess/tess-ews/reporting-absenteeism/

10. Mol an Óige agus tíocfaidh síad is an Irish proverb often translated as “Praise young people and they will flourish”.

11. Nationally, according to the most recent analysis and report to Tusla, the Child and Family Agency (Denner and Cosgrove Citation2020), 5.8% of pupil days were lost due to absence in primary schools in 2017/18 and 7.4% of student days were lost in post-primary schools. At primary level, 12.1% of pupils were absent for 20 days or more while at post-primary level, this figure was 14.6%. Non-attendance, 20-day absences, expulsions and suspensions were highest in schools in the DEIS scheme.

12. Reporting on patterns over the five-year period 2013–18, Denner and Cosgrove (Citation2020) indicate that non-attendance, 20-day absences, expulsions and suspensions were highest in DEIS schools at both primary and post-primary levels. At both levels, “unexplained absences” exceeded 30%.

13. Further information is available at https://www.tusla.ie/tess/information-for-schools/school-completion-programme-tess/

14. Following the economic downturn after 2008, cutbacks in education included some incentivising of older teachers to retire early. Many of those who availed of this left teaching in 2012.

15. That report also brings up an idea that has been mentioned in various policy documents since 2005, namely a sabbatical leave scheme for teachers in DEIS schools (Department of Education and Skills Citation2017a, 54). However, as yet, no such scheme has materialised.

16. Support for schools developing restorative justice practices can be seen through a simple handout from the National Educational Psychological Service (NEPS) at https://www.education.ie/en/Schools-Colleges/Services/National-Educational-Psychological-Service-NEPS-/NEPS-Guides/Listening-to-Young-People-and-Promoting-Dialogue/Restorative-Justice.pdf and at the website of Restorative Practices Ireland http://www.restorativepracticesireland.ie/information-schools/

17. More about the formal Home School Community Liaison scheme can be accessed at https://www.tusla.ie/tess/hscl/

18. On 18 July 2018 the President of Ireland signed into law the Education (Admissions to School) Act.

19. The authors accept that some educational inequalities arise from wider disparities beyond schooling. In particular, the impact on schooling of flawed housing policies is pronounced, especially the tendency to ghettoise people according to socio-economic status.

20. The NBSS now operates under the umbrella of the National Council for Special Education, see http://www.nbss.ie/ncse

21. The Leaving Certificate Applied is a two-year Leaving Certificate, available to students who wish to follow a practical or vocationally orientated programme. It is made up of a range of courses that are structured round three elements: Vocational Preparation, Vocational Education and General Education (www.ncca.ie).

References

- Aguilar, E. 2018. Onward Cultivating Emotional Resilience in Educators. San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Baker, J., K. Lynch, S. Cantillon, and J. Walsh. 2004. Equality, from Theory to Action. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ball, S. J. 1997. “Good School/Bad School: Paradox and Fabrication.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 18 (3): s 317–336. doi:10.1080/0142569970180301.

- Ball, S. J. 2010. “New Class Inequalities in Education: Why Education Policy May Be Looking in the Wrong Place! Education Policy, Civil Society and Social Class.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 30 (3/4): 155–166. doi:10.1108/01443331011033346.

- Barth, R. 2002. “The Culture Builder.” Educational Leadership 59 (8): 6–11.

- Berger, P. L., and T. Luckmann. 1967. The Social Construction of Reality. London: Penguin.

- Bingham, C., and A. M. Sidorkin, Eds. 2004. No Education without Relation. New York: Peter Lang.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction, A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. 1998. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Brantlinger, E. A. 2003. Dividing Classes: How the Middle Class Negotiates and Rationalizes School Advantage. Oxon: Routledge.

- Braun, A., S. Ball, M. Maguire, and K. Hoskins. 2011. “Taking Context Seriously: Towards Explaining Policy Enactments in the Secondary School.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32 (4): 585–596. doi:10.1080/01596306.2011.601555.

- Braun, V., and V. Clark. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” In Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis, Qualitative Research in Sport.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Brennan, J., and G. MacRuairc. 2017. “Different Worlds: The Cadences of Context, Exploring the Emotional Terrain of School Principals’ Practice in Schools in Challenging Circumstances.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership. https://doi-org.jproxy.nuim.ie/10.1177/1741143217725320

- Brookfield, S. D. 1995. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Burke, J., and S. J. Minton. 2019. “Well-being in Post-primary Schools in Ireland: The Assessment and Contribution of Character Strengths.” Irish Educational Studies 38 (2): s. 177–192. doi:10.1080/03323315.2018.1512887.

- Byrne, D., and E. Smyth. 2010. No Way Back? the Dynamic of Early School Leaving. Dublin: ESRI/Liffey Press.

- Carver-Thomas, D., and L. Darling-Hammond. 2017. Teacher Turnover: Why It Matters and What We Can Do about It. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-turnover-report