ABSTRACT

School climate is crucial for understanding everyday school life. For pupils, breaktime seems to be associated with how they feel about their school climate. To better understand school climate and what social processes pupils address, this study explores pupils’ perspectives on school climate with attention on how they perceive their breaktimes. The study was based on 29 focus group interviews (n = 164) with pupils from two public schools in grades 1–9 (i.e. 7–15 years old). Constructivist grounded theory guided data gathering and analysis. Findings revealed how breaktime was an indicator of how pupils perceived their school climate, but their perceptions were dynamic. We conceptualised breaktime as a social process influenced by three main categories: peer climate, levels of unsafe incidents, and availability of activities. We adopted a social-ecological perspective to conceptualise how pupils’ perceptions of breaktimes varied due to how breaktimes were nested within different social-ecological systems.

Introduction

School climate, which refers to “the quality and character of school life” (National School Climate Council Citation2007, 5), is a crucial factor in understanding everyday school life and issues relating to school safety, school belongingness and relationships at school. School climate includes the “shared beliefs, values and attitudes that shape interactions between the pupils, teachers, and administrators” (Mitchell, Bradshaw, and Leaf Citation2010, 272). Previous research highlights how school climate is associated with pupils’ academic achievement (Roorda et al. Citation2017), psychological wellbeing (Aldridge and McChesney Citation2018), problem behaviour (Reaves et al. Citation2018), violence (Steffgen, Recchia, and Viechtbauer Citation2013), and bullying (Zych, Farrington, and Ttofi Citation2019). Research has also found that pupils themselves relate their wellbeing to school climate, including their social relationships with teachers and peers (Newland et al. Citation2019; Powell et al. Citation2018). During breaktimes pupils have more freedom over their activities where they form and negotiate friendships, roles and social identities (Baines, Blatchford, and Golding Citation2020; Bohn-Gettler and Pellegrini Citation2014; Rönnlund Citation2015). As such, breaktime can be a crucial space for social development and learning (Baines, Blatchford, and Golding Citation2020; Bohn-Gettler and Pellegrini Citation2014; Mulryan-Kyne Citation2014; Rönnlund Citation2015). However, breaktime is where a lot of troublesome incidents occur such as fights, peer rejection, harassment and bullying (Fram and Dickmann Citation2012; Mulryan-Kyne Citation2014; Woolley Citation2019), because of its unstructured character and activities (Mulryan-Kyne Citation2014; Vaillancourt et al. Citation2010; Woolley Citation2019), and lack of teacher supervision (Horton, Forsberg, and Thornberg Citation2020; Zumbrunn et al. Citation2013). In a review, McNamara, Colley, and Franklin (Citation2017) reveal how teacher supervision, school policies, availability of equipment, size of breaktime location and various aggressive behaviours are factors influencing breaktimes. When pupils are asked about how they perceive their school, breaktime is oftentimes raised by the pupils themselves (Mulryan-Kyne Citation2014), which suggests that the way pupils feel about their breaktime reflects how they feel about their school (Boulton et al. Citation2009). Research on pupils’ perspectives on breaktime has revealed positive views in general (Baines, Blatchford, and Golding Citation2020; Mulryan-Kyne Citation2014). Studies have reported several reasons why pupils look forward to going on break: socialising with their friends, getting a break from work, free time, time to play games, and being physically active and outside (Fink and Ramstetter Citation2018; Mulryan-Kyne Citation2014). However, studies also show negative views linked to pupils’ experiences of breaktime as dangerous and associated with bullying and conflicts (Massey, Neilson, and Salas Citation2020; Mulryan-Kyne Citation2014), which affect their sense of safety at school (Cowie and Oztug Citation2008; Vaillancourt et al. Citation2010). This has also been linked to teacher supervision, which is sometimes found to be lacking as teachers are too few in number or absent (Syrjäläinen et al. Citation2015; Zumbrunn et al. Citation2013).

Pupils’ perceptions on being on breaktime can also be associated with the intersection of age, scheduling and breaktime location. For example, secondary pupils are more often located and scheduled indoors during breaktime, while it is usually compulsory to be outside during breaktime for elementary pupils. Secondary pupils also tend to be scheduled for shorter breaktimes compared to elementary pupils (Baines, Blatchford, and Golding Citation2020). Time and location can also affect pupils’ perspectives on breaktime activities. Pupils who are located indoors tend to have a shorter breaktime and less activities available. In that sense, secondary pupils might not even have a particular space but rather walk around wishing there were more indoor activities during breaktime (Blatchford Citation1998). Breaktime location might explain why elementary pupils report more bullying in the playground, whereas secondary pupils report more bullying in hallways and cafeterias (Vaillancourt et al. Citation2010). Breaktime location might thus be associated with more or less negative incidents. Differences in how pupils perceive the breaktime might, therefore, be associated with how pupils are scheduled during the school day, which in turn might be connected to what grade they are in. Despite the impact of the breaktime on pupils’ wellbeing, including their social relationships, perception of school climate and sense of school safety, it has not received much attention. There is a need (a) to study breaktimes (recess) “as an entire unit of analysis” (McNamara, Lodewyk, and Franklin Citation2018, 114), and (b) for more research on children’s perspectives in this area (Massey, Neilson, and Salas Citation2020; McNamara, Lodewyk, and Franklin Citation2018). Likewise, it has been argued that more qualitative studies on school climate are needed (Massey, Neilson, and Salas Citation2020; Thapa et al. Citation2013) in order to focus on how pupils themselves understand their school climate and what social processes they address when being asked to reflect on these issues (Massey, Neilson, and Salas Citation2020). The aim of this study is therefore to explore pupils’ perspectives on school climate with attention on how they perceive their breaktimes.

A social-ecological perspective on school climate

In our analysis of pupils’ perspectives on school climate, a social-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979) seemed fruitful. From such a perspective, the school climate and associated processes are understood as embedded within several interconnected systems affecting the school climate, such as peer processes and pupil – teacher relationships (microsystem), the interrelations between different systems (mesosystem), and systems that do not involve the pupil but still affect the school climate, such as the architectural design and the local school board (exosystem) and societal norms (macrosystem) (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979). Thus, the social-ecological perspective can contribute an understanding of how pupils’ perspectives on school safety, relationships at school and breaktime are influenced by these various layers (Zumbrunn et al. Citation2013). There might also be differences between locations in school as different spaces might be affected by different aspects such as scheduling, use of space and whether teachers are present. These differences might, in turn, have an impact on how pupils perceive their breaktimes (Zumbrunn et al. Citation2013).

Methods

This study is part of a project investigating school climate, teacher-pupil relationships and teachers’ leadership through focus group interviews with pupils and teachers. In this study, we explore pupils’ perspectives on school climate. Data were gathered from two public schools which, independently of each other, contacted us and wanted to form a project. The first school was an elementary and lower secondary school including grades 1–9 (approximately ages 7–15) located in a small village where 61% of the pupils had highly educated parents, and 10–12% had a foreign background (i.e. either born in another country or both parents were born in another country). The second school was an elementary school including grades 1–6 (approximately ages 7–12) located in a medium-sized city, where 86% of the pupils had highly educated parents and only 5% had a foreign background. In total, 164 pupils (78 boys and 86 girls) participated in 29 semi-structured focus group interviews.

In each school and grade, a focus group of six boys and a focus group of six girls were organised through a random sampling procedure. Twenty-two focus groups met with six participants, while seven focus groups wound up with four or five participants due to absence or sickness. Prior to data collection, we informed all pupils and caregivers about the project by handing out information and consent letters to the pupils to take home and read, discuss, and decide whether to participate or not, together with their caregivers. We obtained active, written consent from all participating pupils and their caregivers. The teachers helped us to distribute and gather the consent letters from pupils in their classes. Because this procedure took place during the autumn term, some ninth graders were still 14 years old, while other ninth graders had turned 15 (e.g. age 15 is considered old enough to sign a legal consent in Sweden). To avoid pupil-perceived age-discrimination within these school classes, parental consent was required for all in order to participate. All pupils were repeatedly informed about their voluntary participation and assured that information would be confidential and anonymised. Participants have been given pseudonyms. In addition, ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board.

Using focus group interviews can decrease power imbalances between researchers and pupils (Corsaro Citation2011), and gives the pupils greater opportunity to address own topics and questions (Morgan Citation2012). The first and second author conducted all the interviews. Both have extensive experience doing focus group interviews. Pupils were asked open, broad questions about how they perceived the school climate, their sense of safety at school, relationships and activities, including breaktime, and how they perceive spaces available at school to explore their main concern(s) about these contexts and situations. Probing questions were used to further explore the pupils’ perspectives. The interviews took place at the schools, in assigned rooms with closed doors, with only one interviewer present. Interviews were recorded and ranged between 30 and 60 minutes. All interviews were transcribed verbatim. Only the research team had access to the recordings and transcripts.

The data were collected and analysed using a constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz Citation2014). This approach is especially attentive to exploring participants’ perspectives and voices, while at the same time recognising data as co-constructed by researchers and participants. In line with this approach, the interview guide was slightly revised to explore the participants’ main concern(s) and explore relationships between codes, until no additional theoretical insights or patterns emerged (Charmaz Citation2014; Forsberg Citation2022).

We conducted initial, focused and theoretical coding (Charmaz Citation2014). These coding methods were used in a flexible manner where the different levels of coding were not linear; rather we moved back and forth between them. In initial coding, we summarised the data word by word and line by line and compared these codes with each other. A main concern among the pupils when talking about their school climate was their focus on how school safety and peer relations were related to a particular time of the school day, namely breaktime. The breaktime was associated with a number of codes such as being fun/enjoyable, use of space, safety/unsafety and bullying. Through focused coding, we used the most recurring and comprehensive codes developed during initial coding to compare against the data and later to develop concepts. During theoretical coding the relationships between our focused codes were explored. In this part of the coding, we put the categories together to create an analytical story of our categories and their relationships (Charmaz Citation2014).

Findings

Our findings suggest that elementary and lower secondary pupils – both boys and girls – perceived breaktime as an indicator of how they perceive their school climate. Breaktime was a salient context in school where important interactions, friendship processes, belongingness and a sense of school safety/unsafety were experienced and negotiated among the peers. Pupils also reported that negative actions and interactions – such as conflicts, fights, violence, social rejection and bullying – took place much more frequently during breaktime compared with the classroom context. Therefore, their experiences of breaktime at school seemed to have a strong impact on how students perceived and discussed the overall school climate. From their perspective, the quality of breaktime varied as a result of different factors. Reflecting how pupils in the present study talked about breaktime, we conceptualised it as a social process influenced by three main categories: peer climate, levels of unsafe incidents and availability of activities. In this way, their experiences were dynamic rather than static. Our further analysis suggests that pupils’ perspectives on breaktime and these three categories varied due to how breaktime was nested within different social-ecological systems. In the upcoming sections we will present our three main categories in more detail. Although there are overlaps between our categories, we will deal with them one at a time.

The peer climate

One of the main aspects affecting the pupils’ perceptions of their breaktimes was the social processes that occurred in the peer ecology, what we refer to as peer climate. The peer climate focuses on how pupils experience the peer interactions and the peer activities during breaktimes. Thus, what happened among peers during breaktimes was a crucial dimension of how pupils perceived the overall school climate. The degree to which the peer climate was considered great, mostly good, variable, or bad depended on their exposure to positive interactions (e.g. having fun together and friendship) and negative interactions (e.g. fights and violence). In other words, their reports portray a dynamic peer climate. When we asked the pupils what they thought makes a good school climate, the boys in the following excerpt pointed to friendly and trustful peer interactions.

Jon: The pupils are kind.

Melvin: We can trust each other. In my peer group we can. I don’t know what it’s like among everyone else.

Jon: Yes, I’m not in that much trouble.

Bernie: It’s good. (Boys, grade 7)

Other factors that contributed to a good peer climate, according to the pupils, were that everyone was included, had something to do, and could explore new games together with other peers with joy.

On the breaks it’s pretty good. We usually play together. Football and wall games. Not many pupils walk around alone. And if someone is walking around alone, others usually come and ask what is going on or if the person is sad (Jennie, grade 5)

Pupils’ perceived breaktimes as fun and good when they were engaged and included in social activities with peers. However, they also reported factors that contributed to a poor peer climate by referring to disputes, exclusions and other problematic incidents. Thus, a significant factor that seemed to influence pupils’ perceptions of the everyday school climate and sense of school safety was how peers interacted with and treated each other during the breaktimes. This, in turn, created a changeable and dynamic school climate due to what was going on among them. The positive and joyful side of the breaktime, such as playing games and socialising, could turn into an unpleasant and unsafe time of the school day as a result of the presence of fights, teasing, peer rejection, bullying etc. among peers. For example, Liam in first grade disclosed how the peer climate varied due to whether there had been any disputes or not.

It’s different from day to day. Sometimes there’s a dispute. You ask someone if they want to play, and you end up in a dispute because that boy gets angry. So, there are disputes sometimes, but sometimes it’s completely calm and everyone is friends. (Liam, grade 1)

Peer activities and interactions in the playground or breaktimes are at the core of the dynamic and changeable peer climate. In these activities, pupils reported how rules for games could change and be used in an unfair way. They also talked about how disputes could occur about spaces and what activity to engage in. Another possible source of troublesome and negative peer climate that some pupils highlighted was competitive elements such as not being considered skilled enough to play football.

It’s fun to play, usually everyone’s nice. But often not nice as well. It’s fun to play football if you don’t have to do it perfectly. By the rules, but you don’t have to play perfect. But sometimes it is such a pressure. Perfect is like scoring a goal and not letting anyone else take the ball. But sometimes you’re not good at football, and then you aren’t allowed to participate. (Sally, grade 2)

Our analysis of the focus group interview data suggested that the peer climate was highly affected by unstructured peer activities in the playground and other school settings during breaks. If the pupils were included and engaged in these activities, and if peers got along with each other and agreed on activities and rules, they perceived the peer climate during breaktime to be good. In contrast, interruptions, disputes, fights, exclusions and loneliness during their breaktimes were associated with a poor peer climate, which in turn negatively affected their perception of the school climate, particularly in terms of student – student relationship quality, sense of school safety and sense of belongingness. For example, Bettina in ninth grade reported that the peer climate in her class was poor because of ongoing tensions and conflicts between boys and girls. She explained that they did not talk to each other during breaktimes, and they did not get along after having been involved in various disputes. Their current peer climate was poor at the time, and this was especially visible during breaktimes as these were less structured and, therefore, more open for social positioning, conflicts and aggression to take place.

Boys and girls in our class don’t talk to each other on breaks only when you’re forced to work with each other during lesson time. It can happen that people go and throw bread at each other from the dining room, butter packets. Things can happen. (Bettina, grade 9)

Among the lower secondary pupils there were fewer reports of poor peer climate compared to elementary pupils, even though they did state that peers could behave badly and engage in fights, teasing, name-calling, rumour-spreading, social rejection etc. They too pointed to how the peer climate was dynamic and varied due to the ongoing interactions among peers. As pupils also linked their perceptions of the breaktime with how they felt about their school, this also suggested that their perspective on their school climate was changeable and dynamic. Compared to the lower secondary pupils, the elementary pupils in the current study more often talked about their peer climate as poor and negative. Breaktime location seemed to be a possible reason and could be linked with the levels of unsafe incidents.

Levels of unsafe incidents

Like the perception of peer climate, the pupils in our study strongly linked their sense of safety with breaktimes and whether unsafe incidents took place or not. Unsafe incidents included negative peer interactions, disputes, teasing, harassment, exclusion and bullying and were also related to ongoing peer norms. Kind and respectful social interactions created a good peer climate, which produced a sense of safety among the pupils. In contrast, a sense of unsafety tended to emerge when pupils witnessed or became involved in unsafe incidents such as bullying, disputes and peer harassment. Thus, from the pupils’ perspectives, a poor peer climate characterised by negative social interactions was associated with feeling unsafe at school. The negative connection between pupils’ perception of levels of unsafe incidents and their perception of school climate in our findings can be compared with the literature that conceptualises school safety as a dimension of the school climate (Bradshaw et al. Citation2014; Kutsyuruba, Klinger, and Hussain Citation2015; Thapa et al. Citation2013).

While pupils’ sense of safety was situated and fluent as it was dependent on ongoing social interactions and peer activities, some pupils reported a recurrent pattern of feeling unsafe, and they associated their sense of unsafety with repeated experiences of being teased, rejected or commented upon. In other words, experiences of repeated peer victimisation, such as being bullied, created a sense of school unsafety. For instance, Tyra in second grade expressed that she felt unsafe during breaktimes because “a lot of people tease me during breaktimes”.

Pupils’ experiences of being safe or unsafe were also related to peer norms. If pupils’ felt that they did not fit into certain peer norms, they were afraid that peers would give them negative comments, call them names, tease them, exclude them and even bully them. The perceived presence of peer norms and expectations of socially desirable and undesirable behaviours and ways of being a person were also more subtle in creating a sense of unsafety in school and particularly during breaktimes. For example, a third-grade girl told us that she felt unsafe and sad when a peer said to her that she was boring. She and another girl in the same focus group related this label with not being engaged in the “right” type of activities during breaktimes.

Moa: Sometimes I’m not safe, when someone says that I’m not kind, or that I’m boring, then I get very sad, I can get very sad.

Interviewer: Why do you think they say that?

Moa: Because I might not want to do the thing she wants.

Lisa: It can be that they want to play horse, and then you say, no, I don’t want that. You’re boring! (Grade 3)

According to the girls in the excerpt above, pupils’ sense of safety was negatively affected by experiences of verbal comments and being positioned as “boring”. Peer norms are a part of the peer climate in school and, thus, the overall school climate. Peer norms are negotiated in peer interactions, and peers in more powerful positions have a stronger influence on norm setting. Thus, peer norms can be linked to power imbalance, and less powerful peers who fail to live up to certain peer norms may experience more teasing, labelling, rejection and victimisation, and therefore less school safety. The association between power imbalance and a sense of school unsafety is also associated with age. Participants in our study reported experiences of feeling unsafe as a result of being teased or victimised by older pupils.

Lana: I think most people feel safe, but some don’t. Some may tease others. Those who are a little younger than them. And it doesn’t feel so safe then. You get out on breaks, and you get teased. It doesn’t feel great.

Interviewer: No, so you think it has to do with age, older pupils who?

Lana: It’s older people who tease younger people. (Grade 2)

A poor peer climate is created when a power imbalance in terms of age produces peer victimisation towards those who are younger, which in turn leads to a sense of school unsafety among the younger pupils. Again, this point about how pupils perceived the interactions among peers at school indicated something about how they perceived the school climate. As these interactions could vary, so too could their perceptions of the school climate. One aspect that pupils raised was the link between school unsafety and the presence of more aggressive and conflictual pupils (e.g. “You can be scared for those who fight a lot. During breaktimes. Because indoors you have the teachers nearby”, Max grade 2). This also points at differences between indoor and outdoor spaces, as the former were associated with teacher presence while the latter were more related to teacher absence. In relation to this, elementary pupils were located outdoors during breaktimes, whereas lower secondary pupils were located indoors. Many pupils related their perceptions of school safety to the presence of teachers, while they associated school unsafety with the absence of teachers, which in turn emphasised breaktimes as a potential area of school unsafety. This was put forward by a group of boys who argued that teacher absence in particular locations in the playground made breaktimes more unsafe.

Elias: It’s probably at the steeplechase course or the football field.

Danny: Or in the middle of the schoolyard, because there is quite a lot.

Interviewer: What is it that makes those places–

Elias: I think the football field is–

Danny: There are no teachers and then there is–, that is usually where you fight. (Grade 3)

As described by the pupils in the excerpt, various locations could become unsafe depending on the levels of unsafe incidents happening there. They also pointed out that the absence of teachers made room for negative incidents to occur. The pupils argued that the more teachers were present during breaktime, the safer pupils felt in these situations because teachers’ presence would decrease the level of unsafe incidents. According to the elementary pupils, some spots could also become more conflictual and unsafe due to teacher absence. The elementary pupils pointed out several issues related to how teachers were not outside during breaktime, how there were not enough teachers, and how they could not cover the whole schoolyard, which refers to school design and scheduling.

Once something is going on, an adult does not take care of it, there are maybe three adults in the whole schoolyard, on a long break, and everyone is down in the big schoolyard. On the football field. So, if something happens up here, no one takes care of it. And it takes time to fetch a teacher and then the student is sad already. (Benji, grade 6)

Whether teachers were present or absent was found to be associated with the peer climate as well as with the sense of safety, which pointed to the interplay across different components of school climate (i.e. teacher – pupil interactions, peer climate, and school safety in this case) from the pupils’ point of view.

While there were fewer reports of negative interactions among peers and a poor school climate from lower secondary pupils and their indoor breaks, incidents did, nevertheless, occur indoors, and affected pupils’ sense of safety at school. Some girls reported that there was a particular spot in the hallway where unsafe incidents could take place as some pupils brought food from the canteen to throw at other pupils in the hallway.

Bettina: You want to avoid the bread and things that come flying during the breaks.

Sandra: It can be a bit chaotic.

Bettina: In the hallway they usually run around play wrestling or throw things at each other

Sandra: There you may not be so safe, because you don’t want to be beaten.

Jasmine: You don’t want to get soaked bread in your head.

Bettina: Or like crushed noodles. But it’s like – people are sitting there at the benches and maybe trying to study to prepare for class, you want to read through it one last time, they get very disturbed by the fact that things are flying. (Girls, grade 9)

These incidents affected their sense of safety, and they also raised how it might affect pupils who want to prepare for class. In addition to this, lower secondary pupils also emphasised how they had shorter breaks and few places to be during breaktime, which might affect their ability to get away from unsafe incidents and spaces. However, they also disclosed how there was not enough time to do anything other than just sit around, waiting for the next lesson to start. The passive waiting within a short breaktime made less room for unsafe incidents, and therefore seemed to make hallways safer than the schoolyard (but still more unsafe than classrooms where teachers were present), according to the pupils.

Marcus: The place I’m at is the classroom and the benches outside the classroom and the sofa group, so it’s not, you sit where there is room and it’s not unsafe anywhere.

Henry: It’s not like we’re out in the schoolyard doing something, so it’s more like sitting down somewhere and waiting. Because we have like a quarter of a break. What are you going to do?

Marcus: More like go to the next lesson and sit and wait for it to start. (Grade 8)

The lower secondary pupils argued that the scheduling of lessons and breaks affected their breaktimes and what was going on there in several ways. Scheduling affected where they were located during their breaktimes and what they were doing. In contrast to being outdoors during longer breaks (as in the elementary school), the lower secondary pupils expressed that they were safe because their breaktime was short, located indoors, where they were only sitting down and waiting for the next lesson to start.

A number of these issues raised here connect to school design and aspects such as size and availability of activities. Another aspect emphasised was that of scheduling of both teachers and pupils that affected pupils’ perception of their breaktime and what activities they were or could be involved in during breaktime. The next part explores factors related to their peer activities during breaktime.

Availability of activities

In addition to peer climate and levels of unsafe incidents, the pupils’ perceptions of their school climate were also affected by their breaktime activities, which, in turn, were influenced by peer norms, power imbalance, breaktime lengths and where their breaktime took place, and thus what activities were available. One crucial issue that pupils talked about was that there were not enough activities available. This aspect was prevalent both indoors and outdoors. Not having anything to do during breaktime created a basic feeling of boredom.

Carl: It’s boring at breaks, there’s nothing to do.

Joseph: No, there is nothing to do.

Martin: You can play football

Carl: No, I don’t like football. (Grade 5)

As seen in the example above, a low availability of activities made breaktimes boring for some pupils, and pupils asked for more available resources and, thus, activities during breaktime (e.g. “I want more stuff to play with in school, more footballs”, Milton, grade 1). While the elementary pupils described various and situated levels of availability of activities during their breaks, the lower secondary pupils complained about the lack of availability of activities during breaktime indoors.

Cecile: Sit still, check your mobile, go to the supermarket, there should be more things to do.

Sarah: There is too little to do

Cecile: And they have said that ‘when the ninth-graders end there will be more space’, but no there isn’t.

ecile: And they have said that ‘when the ninth-graders end there will be more space’, but no there isn’t.

Sarah: No, new pupils come.

Cecile: Yes, so many people are sitting there, and you don’t want to sit very close to people you don’t know.

Marie: No, but it’s like either you sit on top of each other or you have to go and sit on someone–, on the floor or something instead.

Cecile: It isn’t that great to sit on the floor. I think that they should have some sofas by the classroom or in the hallway or something, but they don’t think you should have sofas in the hallway because – I don’t know why they don’t want it, they suggest that we go to the leisure centre, but it’s often full there. (Grade 8)

As seen from this example from the lower secondary pupils, their experiences point to how there was not enough to do during breaktime. This was also related to the crowdedness of the spaces they were located at during the breaktimes. High pupil density limited the availability of activities and, hence, contributed to a sense of boredom. The degree of pupil density (crowdedness) was connected to the degree to which pupils were scheduled at breaktime at the same time. For the pupils in elementary school, high pupil density not only decreased the availability of activities, but also increased competition and conflicts about available activities, which suggests a link between low availability of activities and levels of unsafe incidents through pupil density or crowdedness. In the example below, this is pointed out by pupils in elementary school.

I think most things work well during breaks. There may be competition over spaces in the schoolyard, for example when playing Kråkan, but otherwise I think it’s pretty good, it’s a big schoolyard. Sure, it can get messy, because there are so many pupils on the same break, and then there can be quite a lot of disputes about how much space you can use. But I haven’t seen so much. It happens sometimes. (Roland, grade 6)

The connection between disputes and crowded breaks was most prevalent among the elementary pupils who were located outside in the playground. According to the pupils, the type of available activities outdoors also seemed to be linked to more disputes and negative incidents. In the excerpt below, some lower secondary pupils talked about how the availability of activities in the different settings contributed to more or less negative incidents.

Cleo: It was probably that you were outside on breaks, more things happen when you’re outdoors like when you play floorball or football or something.

Alma: And then there can be conflicts and fights. It happens a lot more on breaks. Here indoors, it’s like you sit on the couch and check your mobile. (Grade 7)

As seen from this excerpt, the pupils associated the levels of unsafe incidents with the type of activities they were engaged in during breaktime. However, many elementary pupils thought that if the school scheduled the breaktimes differently (i.e. having smaller groups of pupils in the playground at the same time) to avoid the crowdedness, then the troublesome and sometimes hostile competition over availability of activities would decrease.

Roland: To solve this problem you could go on break when another class stops having a break.

Sean: So, no one needs to have a break at the same time.

Roland: Yes, maybe only two classes that have a break at the same time, so you don’t need to–

Sean: Like be just as messy.

Roland: So, there will not be as much competition over spaces. (Grade 6)

As can be seen, elementary pupils pointed to issues of scheduling and how a different schedule would resolve the issue of crowded spaces and in turn affect the number of competitions, disputes and fights over spaces and available activities. Like high levels of unsafe incidents, these competitive and hostile social processes caused pupils to perceive school unsafety and a negative peer climate, which altogether produced a sense of a negative school climate. At the same time, they suggested changes in scheduling breaks in order to avoid crowdedness in the playground as a potential solution.

Discussion

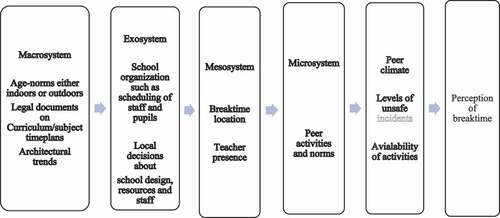

The aim of this study was to explore pupils’ perspectives on school climate, with attention on breaktime. Our study contributes important insights on children’s perspectives regarding some of the social dynamics during breaktime. Furthermore, our study suggests that perceptions of breaktime are a prominent part of how pupils perceive their school climate. However, their perceptions are dynamic due to three interrelated aspects: peer climate, levels of unsafe incidents and availability of activities. These aspects are, in turn, influenced by a complex interplay among social-ecological factors (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979) on the micro-, meso-, exo- and macrosystem levels ().

The macrosystem includes societal discourses and norms, and school political regulations on how to organise schools, the school environment, teaching subjects, schedules, and activities (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979), and some of these macro-level discourses, norms and regulations are related to discourses on children’s age and development (cf. Leonard Citation2016). In this way, the macrosystem affects how the pupils in the current study experienced their breaktime in terms of, for instance, lengths and location due to their age. According to their reports, elementary pupils were located outdoors and had longer breaktimes compared to lower secondary pupils, who were located indoors. Older pupils have oftentimes shorter breaktimes compared to younger pupils (Baines, Blatchford, and Golding Citation2020; Bohn-Gettler and Pellegrini Citation2014). This points to how breaktimes are related to age-related norms on where and what pupils should be doing during breaktime (Pihlgren Citation2019) but also legal documents, school policies and ongoing school political debates about how long breaktimes should be (Bohn-Gettler and Pellegrini Citation2014). Although the principal at each particular school in Sweden has the authority to decide on breaktime lengths and how to schedule them (Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education] Citation2021), the macrosystem (re)produces frame factors that influence and limit their decisions and agency (Maxwell Citation1985). For instance, considering that lower secondary pupils read more subjects and have more lesson hours for every subject compared to elementary pupils (Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education] Citation2021), it is thus probable that the curriculum and subject timetables affect this scheduling. The macrosystem influences how schools organise breaktime (local decisions that take place in the exosystem from the pupils’ position in school). This interplay influences availability of activities, the feelings pupils experience during the break (e.g. joy, boredom, worry), crowdedness (pupil density), peer climate, levels of peer conflicts and aggression, and thus the levels of unsafe incidents, which altogether affect the school climate and pupils’ sense of school safety.

There is also the issue of architectural trends that will affect decisions made at the exosystem level (Lenninger Citation2019), where various decisions are taken on how schools and playgrounds should be designed, and schools and teachers can seldom influence these decisions. In relation to this, the local school board and associated organisation also take decisions on school finances affecting the ability of schools to purchase material such as more footballs, as asked for by the pupils in this study, and decisions affecting the availability of teachers. In other words, frame factors (re)produced in the exosystem affect the local school’s resources, including how breaktime is organised in the school, which in turn influences how pupils perceive and experience the availability of activities, teacher presence/absence and levels of unsafe incidents during breaktimes in the local school.

On a mesosystem level then, these exosystem factors influenced, for example, how many teachers were present or absent as playground supervisors. The pupils considered teacher presence versus absence as a key factor regarding the prevalence of unsafe incidents, where the latter was experienced to have a negative effect on the peer climate (Syrjäläinen et al. Citation2015; Zumbrunn et al. Citation2013). Teachers were more often present among lower secondary pupils, as they spent their breaktimes indoors. Teacher presence created a safer context because it decreased the opportunities for unsafe incidents to take place. In contrast, the elementary pupils spent their breaktimes in the playground, where there were too few teachers present. In relation to school design, teacher presence was more of a concern outdoors, but it was the absence of teachers that enabled unsafe incidents, such as teasing, fights and peer victimisation, to take place both indoors and outdoors. Although teacher presence as playground supervisors has an impact on reducing unsafe incidents such as peer aggression and bullying (Bohn-Gettler and Pellegrini Citation2014; Ttofi and Farrington Citation2009), school design might also affect teachers’ ability to cover all areas (Horton, Forsberg, and Thornberg Citation2020).

Unsafe incidents were also related to peer activities. On a microsystem level, what pupils were doing during breaktimes and their involvement in various activities affected both the peer climate and levels of unsafe incidents. Breaktimes outdoors seemed to offer more opportunities for various activities, but also more unsafe incidents. Indoors, pupils were cramped and bored but appeared safer. Their activities were also influenced by peer norms about “right” and “wrong” activities, popularity and power structure in the peer ecology, rule negotiations, inclusion criteria, and popular and crowded spaces. This adds to our understanding of some of the social dynamics involved at breaktimes (Massey, Neilson, and Salas Citation2020). As previously pointed out, where and when their breaktimes took place also affected what activities pupils could engage in, in terms of activities available. Scheduling thus clearly affected availability of activities. This was also addressed by the pupils, who pointed to the relation between scheduling and pupil density, availability of activities and unsafe incidents.

The breaktime was a crucial aspect for how pupils perceived their school climate (Boulton et al. Citation2009) and their perceptions of the school climate were related to their social relationships in school (Newland et al. Citation2019; Powell et al. Citation2018) and school safety. The present findings indicate the relevance of various frame factors such as school design, scheduling, supervision, material resources and availability of activities and how they were linked to the levels of unsafe incidents, peer conflicts, aggression and victimisation (Horton, Forsberg, and Thornberg Citation2020; Massey, Neilson, and Salas Citation2020; McNamara, Lodewyk, and Franklin Citation2018). In other words, and with reference to the pupils’ perspectives, these frame factors influenced the quality of peer climate and the sense of school (un)safety, which are salient dimensions of the overall school climate (Bradshaw et al. Citation2014; Kutsyuruba, Klinger, and Hussain Citation2015; Thapa et al. Citation2013), particularly from the pupils’ point of view. In addition, our findings revealed that the location of the breaktime is a crucial factor (Zumbrunn et al. Citation2013) based on the pupils’ experiences: indoors versus outdoors, availability of supervision, size and space popularity.

Some limitations should be addressed in relation to our study. This is a small-scale, in-depth qualitative study where we attend to pupils’ narratives about their breaktimes and school climate. This might not resonate with what is happening in their everyday, real-life setting. In addition, our findings might not be representative of other contexts. However, in line with our constructivist grounded theory position (Charmaz Citation2014), we offer an interpretive portrayal of the phenomenon studied, where our study contributes valuable insights into pupils’ perspectives on their school climate.

We also chose to organise the focus groups based on a random sampling procedure within each school, gender and grade. This might have affected group dynamics during the interviews. In addition, we conducted gender-segregated focus group interviews because pupils usually form same-gender friendships and thus might feel safer in a gender-segregated setting to discuss gendered dimensions of breaktime. However, mixed-gender groups might have bought attention to other social processes and nuances. With that said, we did not discover any differences based on gender in terms of how pupils experienced breaktime. However, some gendered examples were disclosed – such as the disputes among boys and girls – that might not have been raised in a more mixed-gender group setting.

These limitations aside, the present findings have some practical implications. Principals, teachers and schools need to pay attention to how breaktime can be organised to support a positive and safe school climate. Special attention can be given to the aspects that appear to affect the peer climate, levels of unsafe incidents and availability of activities, where various frame factors were pointed out by pupils. Teacher supervision and scheduling, in particular, seem to be two tools to create a more positive, pleasant and safer breaktime for pupils. This would affect the peer climate, as well as the school climate in general. According to pupils, scheduling of breaktime could influence crowding and decrease pupil density, along their involvement in activities to increase and reducing unsafe incidents. Having teachers present during breaktime seems to decrease unsafe incidents and make pupils feel safer. However, whether scheduling or supervision can be used as tools raises questions about the scheduling of the school day in relation to the national curriculum/timetabling (macrosystem) and possible decisions at the exosystem level that might influence and limit individual schools’ agency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Camilla Forsberg

Camilla Forsberg is a senior lecturer in Education at the Department of Behavioral sciences and Learning, Linkoping University, Sweden. Her current research explores the relationships between schooling, gender and school bullying in Swedish schools. Other research areas include students’ and teachers’ perspectives on social climate and relations in school.

Eva Hammar Chiriac

Eva Hammar Chiriac is a professor of Psychology at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linkoping University, Sweden. Her scientific activity lies within the social psychological research field with a strong focus on group research, group processes, learning and education. Her current research project concerns group work assessment, school climate and relations in schools, and problem-based learning.

Robert Thornberg

Robert Thornberg is a professor of Education at the Department of Behavioral sciences and Learning, Linkoping University, Sweden. His current research is on school bullying, social and moral processes involved in bullying, bystander reactions and actions, and students’ perspectives and explanations. Other research areas include social climate and relations in school, values education, and student teachers’ emotionally distressing educational situations.

References

- Aldridge, J. M., and K. McChesney. 2018. “The Relationships Between School Climate and Adolescent Mental Health and Wellbeing: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Educational Research 88: 121–145. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2018.01.012.

- Baines, E., P. Blatchford, and K. Golding. 2020. “School Breaktimes/recess as a Context for Understanding Children’s Development.” Health 80: 517–526.

- Blatchford, P. 1998. Social Life in School: Pupils´experience of Breaktime and Recess from 7 to 16 Years. London: Psychology Press.

- Bohn-Gettler, C. M., and A. D. Pellegrini. 2014. “Recess in Primary School: The Disjuncture Between Educational Policy and Scientific Research.” In Justice, Conflict and Wellbeing: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Brian H. Bornstein, and Richard L. Weiner, 313–336. New York: Springer.

- Boulton, M. J., C. Chau, C. Whitehand, K. Amataya, and L. Murray. 2009. “Concurrent and Short‐term Longitudinal Associations Between Peer Victimization and School and Recess Liking During Middle Childhood.” The British Journal of Educational Psychology 79 (2): 207–221. doi:10.1348/000709908X336131.

- Bradshaw, C. P., T. E. Waasdorp, K. J. Debnam, and S. Lindstrom Johnson. 2014. “Measuring School Climate in High Schools: A Focus on Safety, Engagement, and the Environment.” The Journal of School Health 84 (2): 593–604. doi:10.1111/josh.12186.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambride: Harvard University Press.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: Sage.

- Corsaro, W. 2011. The Sociology of Childhood. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

- Cowie, H., and O. Oztug. 2008. “Pupils’ Perceptions of Safety at School.” Pastoral Care in Education 26 (2): 59–67. doi:10.1080/02643940802062501.

- Fink, D. B., and C. L. Ramstetter. 2018. ““Even if They’re Being Bad, Maybe They Need a Chance to Run Around”: What Children Think About Recess.” The Journal of School Health 88 (12): 928–935. doi:10.1111/josh.12704.

- Forsberg, C. 2022. “The Importance of Being Attentive to Social Processes in School Bullying Research: Adopting a Constructivist Grounded Theory Approach.” International Journal of Bullying Prevention 1–10. doi:10.1007/s42380-022-00132-y.

- Fram, S. M., and E. M. Dickmann. 2012. “How the School Built Environment Exacerbates Bullying and Peer Harassment.” Children, Youth and Environments 22 (1): 227–249. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.22.1.0227.

- Horton, P., C. Forsberg, and R. Thornberg. 2020. “It’s Hard to Be Everywhere”: Teachers’ Perspectives on Spatiality, School Design and School Bullying 12 (2): 41–55.

- Kutsyuruba, B., D. A. Klinger, and A. Hussain. 2015. “Relationships Among School Climate, School Safety, and Student Achievement and Well-Being: A Review of the Literature.” Review of Education 3 (2): 103–135. doi:10.1002/rev3.3043.

- Lenninger, A. 2019. “Föreställningar Om Skolgården.” In Rasten: Möjligheternas Mellanrum, edited by Ann S. Pihlgren, 137–155. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Leonard, M. 2016. The Sociology of Children, Childhood and Generation. London: Sage.

- Massey, W., L. Neilson, and J. Salas. 2020. “A Critical Examination of School-Based Recess: What Do the Children Think?” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 12 (5): 749–763. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1683062.

- Maxwell, T. 1985. “The Illumination of Situational Analysis by Frame Factor Theory.” Curriculum Perspectives 5 (1): 47–52.

- McNamara, L., P. Colley, and N. Franklin. 2017. “School Recess, Social Connectedness and Health: A Canadian Perspective.” Health Promotion International 32 (2): 392–402. doi:10.1093/heapro/dav102.

- McNamara, L., K. Lodewyk, and N. Franklin. 2018. “Recess: A Study of Belongingness, Affect, and Victimization on the Playground.” Children & Schools 40 (2): 114–121.

- Mitchell, M. M., C. P. Bradshaw, and P. J. Leaf. 2010. “Student and Teacher Perceptions of School Climate: A Multilevel Exploration of Patterns of Discrepancy.” The Journal of School Health 80 (6): 271–279. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00501.x.

- Morgan, D. L. 2012. “Focus Groups and Social Interaction.” In The Sage Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft, edited by Jaber F. Gubrium, James A. Holstein, Amir B. Marvasti, and Karyn D. McKinney, 161–176. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Mulryan-Kyne, C. 2014. “The School Playground Experience: Opportunities and Challenges for Children and School Staff.” Educational Studies 40 (4): 377–395. doi:10.1080/03055698.2014.930337.

- National School Climate Council. 2007. The School Climate Challenge: Narrowing the Gap Between School Climate Research and School Climate Policy, Practice Guidelines and Teacher Education Policy. http://www.schoolclimate.org/climate/advocacy

- Newland, L. A., D. Mourlam, G. Strouse, D. DeCino, and C. Hanson. 2019. “A Phenomenological Exploration of Children’s School Life and Well-Being.” Learning Environments Research 22 (3): 311–323. doi:10.1007/s10984-019-09285-y.

- Pihlgren, A. 2019. “Introduction.” In Rasten: Möjligheternas Mellanrum, edited by Ann S. Pihlgren, 21–32. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Powell, M. A., A. Graham, R. Fitzgerald, N. Thomas, and N. E. White. 2018. “Wellbeing in Schools: What Do Students Tell Us”?” Australian Educational Researcher 45 (4): 515–531. doi:10.1007/s13384-018-0273-z.

- Reaves, S., S. D. McMahon, S. N. Duffy, and L. Ruiz. 2018. “The Test of Time: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Relation Between School Climate and Problem Behavior.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 39: 100–108. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2018.01.006.

- Rönnlund, M. 2015. “Schoolyard Stories: Processes of Gender Identity in a ‘Children’s Place’.” Childhood 22 (1): 85–100. doi:10.1177/0907568213512693.

- Roorda, D. L., S. Jak, M. Zee, F. J. Oort, and H. M. Y. Koomen. 2017. “Affective Teacher–student Relationships and Students’ Engagement and Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Update and Test of the Mediating Role of Engagement.” School Psychology Review 46 (3): 239–261. doi:10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3.

- Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education] (2021). Rektorns Ansvar [The Responsibility of the Principal]. https://www.skolverket.se/regler-och-ansvar/ansvar-i-skolfragor/rektorns-ansvar

- Steffgen, G., S. Recchia, and W. Viechtbauer. 2013. “The Link Between School Climate and Violence in School: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 18: 300–309. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.12.001.

- Syrjäläinen, E., P. Jukarainen, V. M. Värri, and S. Kaupinmäki. 2015. “Safe School Day According to the Young.” Young 23 (1): 59–75. doi:10.1177/1103308814557399.

- Thapa, A., J. Cohen, S. Guffey, and A. Higgins-D’Alessandro. 2013. “A Review of School Climate Research.” Review of Educational Research 83 (3): 357–385. doi:10.3102/0034654313483907.

- Ttofi, M., and D. Farrington. 2009. “What Works in Preventing Bullying: Effective Elements of Anti‐bullying Programmes.” Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 1 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1108/17596599200900003.

- Vaillancourt, T., H. Brittain, L. Bennett, S. Arnocky, P. McDougall, S. Hymel, K. Short, et al. 2010. “Places to Avoid: Population-Based Study of Student Reports of Unsafe and High Bullying Areas at School.” Canadian Journal of School Psychology 25 (1): 40–54. doi:10.1177/0829573509358686.

- Woolley, R. 2019. “Towards an Inclusive Understanding of Bullying: Identifying Conceptions and Practice in the Primary School Workforce.” Educational Review 71 (6): 730–747. doi:10.1080/00131911.2018.1471666.

- Zumbrunn, S., B. Doll, K. Dooley, C. LeClair, and C. Wimmer. 2013. “Assessing Student Perceptions of Positive and Negative Social Interactions in Specific School Settings.” International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 1 (2): 82–93. doi:10.1080/21683603.2013.803001.

- Zych, I., D. P. Farrington, and M. M. Ttofi. 2019. “Protective Factors Against Bullying and Cyberbullying: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 45: 4–19. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2018.06.008.