The conflation of labour activism and political activism in Namibian history and historiography – or views of a seamless transition between the two – has meant that meaningful empirical historical studies of labour relations and labour policy in Namibia have been downplayed, leaving scholars to rely on older, potentially outdated studies. The articles in this part-special issue de-centre Namibian nationalism from the economic and labour history of Namibia, instead re-centring the labour process, labour policy and the lived history of labourers themselves. Studying labour history necessitates working at multiple scales. Global labour history (GLH) frameworks, in conjunction with transnational and microhistory methodologies, enable deep consideration of structural transformations in globally interconnected economies as well as local contingent factors. GLH has helped to guide labour historians to balance both global and local scales. The articles in this special issue draw from new archival and oral history sources in order to reinvestigate central themes in Namibian labour history and to open new vistas for future research.

Introduction: A Meeting

On 7 October 1960, just a few months after its founding, four representatives of the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) participated in a conference with the vice president of Newmont Mining Corporation, M.D. Banghart, in New York. Mburumba Kerina, Sam Nujoma, Jacob Kuhangua and Markus Kooper represented the nascent nationalist movement in exile and were regular petitioners to the UN Special Committee on Decolonisation. In 1947, Newmont had become managing partner in Tsumeb Corporation Ltd (TCL), the owner of Tsumeb mine.Footnote1 Tsumeb was the largest base metal mine in Namibia, then South West Africa (SWA), and one of the colony’s largest private employers. TCL management played a prominent role in the territory’s migrant contract labour recruiting organisation, the South West Africa Native Labour Association (SWANLA).

In the meeting, the SWAPO representatives aired their grievances regarding Namibia’s contract labour system, through which black workers from densely populated northern Namibia and southern Angola were recruited and transported to work in areas of white colonial settlement. They lamented poor housing conditions and wages for black workers at Tsumeb mine and elsewhere and they raised concerns about TCL’s unwillingness to train black workers for skilled labour. Furthermore, Kerina highlighted the deleterious social effects of 6–18-month labour contracts on workers themselves and their families left in the sending areas. He and his colleagues ultimately sought the abolition of SWANLA itself. The SWAPO representatives’ visit profoundly worried Banghart, who noted, ‘[w]e think this organisation [SWAPO] is dangerous and it may result in the equivalent of a Native Labour Union at Tsumeb’.Footnote2

Conflating Labour and Politics: Progress and Pitfalls

Although SWANLA contract labour played a crucial role in Namibia’s 20th-century political history, the path from anti-SWANLA activism to nationalism was a sinuous rather than straight one. Historians of Namibia have correctly noted that, unlike the African National Congress (ANC) of South Africa and other southern African anti-colonial movements, whose founders originated from the budding African intelligentsia class, SWAPO was born out of labour activism, particularly Ovambos involved in the contract labour system.Footnote3 After all, the predecessors to SWAPO were two parallel ethnically defined labour organisations: the Ovamboland People’s Congress (OPC), founded by Andimba Toivo ya Toivo and other Ovambo workers in Cape Town, and the Ovamboland People’s Organisation (OPO), founded by Sam Nujoma and Ovambo migrant workers in Windhoek.Footnote4 When SWAPO was formally inaugurated in 1960, built upon the foundations of the OPC and OPO, its founders’ initial critique centred on labour grievances.Footnote5

The historical trajectory of SWAPO – from a workers’ organisation to a nationalist movement – has shaped the way in which scholars have considered the history of labour and workers in Namibia. In emphasising a causal link between the exploitation of the SWANLA contract labour system and the rise of anti-colonial nationalism, the historiography of Namibia has obscured and downplayed various forms of labour relations and political mobilisation throughout the 20th century. Political activism and labour activism need not be identical. Indeed, it took time for SWAPO’s initial critiques to be shaped into a broader anti-apartheid and anti-colonial platform received on international stages.

There is a voluminous literature stretching back to the apartheid period itself on the relationship between migrant labour and anti-colonial political action. These issues are central throughout SWAPO’s 1981 official history, To Be Born a Nation, and other academic studies of Namibia during the apartheid years. Zedekia Ngavirue’s doctoral thesis was among the first to include an extended study of labour relations in Namibia.Footnote6 Richard Moorsom’s work on the contract labour system, based primarily on official reports, revealed some of the intricacies of SWANLA’s labour hire policies, but it was ultimately marred by teleological understandings of the development of workers’ consciousness amid nationalism.Footnote7 Moreover, international organisations have long appreciated connections between labour relations and anti-colonial politics in Namibia, with an in-depth study published by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in 1977.Footnote8 Since Namibia’s independence in 1990, histories of contract labour and liberation remain intertwined within both popular consciousness and academic writing.Footnote9 In a growing body of ‘exile literature’, senior Namibian politicians and former freedom fighters often discuss their experiences with the contract labour system and engagement with okaholo as something of a prelude to nationalist sentiment.Footnote10

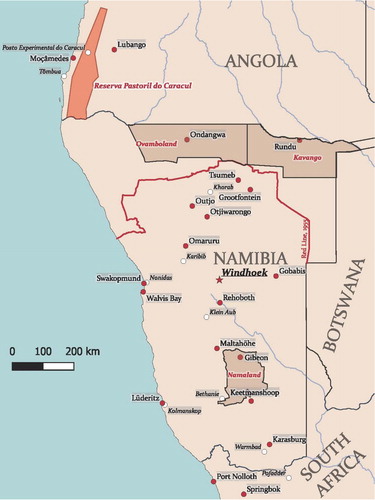

Views in Namibian historiography of a seamless interlinking of labour activism and anti-apartheid politics have inhibited our ability to conduct meaningful studies of labour relations, labour policy and the history of workers. This part-special issue seeks to redress this. We build upon groundwork laid in an earlier special issue of the Journal of Southern African Studies – ‘The South African Empire’Footnote11 – which emphasised the absence of Namibia within South African historiography, revealing a misunderstanding of both central aspects of Namibia’s historical trajectory and its importance to South African history itself.Footnote12 JSAS’s ‘South African Empire’ issue did not, regrettably, contain any articles concerning Namibian labour history, itself a transnational and global phenomenon that was intricately related to central themes in that issue. GLH, as well as transnational and microhistory approaches, unsettles a predominantly national historiography to enable empirical investigation of the broad factors shaping labour relations in Namibia. These articles also place Namibia in trans-colonial and transnational contexts of labour migration and administration; the ‘labour question’ in Namibian history stretched beyond the Kunene, Okavango, and Orange rivers (see ). The articles in this issue reveal that regional and global perspectives can be held in conjunction with sensitivity to the specificities of Namibia and of Namibians’ lived experiences.

The emerging field of GLH seeks to move beyond the ‘methodological nationalism’ of classical labour history, instead analysing transnational, cross-border phenomena or placing small-scale processes in global context.Footnote13 GLH, according to one of its most vocal proponents, Marcel van der Linden, is at its essence concerned with ‘comparing commodified labour relations and … reconstructing their global interconnections and their consequences’.Footnote14 Concerning Namibian and southern African history, these global interconnections can take a number of forms: from commodity chains and pathways of labour associated with producing and transporting goods, to ideologies of colonial capitalism spanning empires, to global economic transformations which affect local labour relations. Furthermore, van der Linden argues that, by examining the intensification (or weakening) of local and global interconnections and migrations, it is possible to write a global labour history of ‘a small village, work site, or family’.Footnote15 A GLH of Namibia takes seriously its spatiality, fraught frontier sites where both increasing and decreasing mobility occurred, its dual colonial heritage (German and South African), and its trans-imperial connections. Ultimately, the empirical material considered within each of the articles in this special issue adds context and nuance to various themes in Namibian labour history, each with transnational implications and applicability beyond the borders of Namibia.

Broadening the Scales in Namibian Labour History: Beyond the Local

Since the years surrounding Namibia’s independence in 1990, there has been a growth in historical writing about topics relating to labour. Not all of these have conflated labour history and political history or labour activism and political activism. Many are grounded in local case studies of specific African communities in Namibia, and these often provide excellent guides to specific instances of the ‘labour question’. While the geographical rootedness of these (mostly) social histories furnish insights that only local studies could, the questions that labour historians ask often require both working at broader geographical scales and to move between scales. In this section, we make a brief historical foray into some aspects of the ‘labour question’ that interested historians in the late 20th century independence era, allowing us to build a road map for broader transnational and global perspectives and comparisons.

Once the League of Nations mandate for Namibia was officially handed over to South Africa – replacing the latter’s martial law administration – South Africa quickly took steps to consolidate power over Namibia and to treat Namibia as its own settler colony: a source of raw materials for export and of land to settle their growing ‘poor white’ population. Although South Africa preserved most aspects of German ‘native policy’ within the Police Zone, the beginning of South African rule in Namibia saw important changes in the north. This included the installation of a permanent resident commissioner in Ovamboland for the first time and the transformation of the Police Zone’s northern boundary into a labour cordon.Footnote16 Within the Police Zone, the new South African regime overturned the Germans’ ban on African cattle ownership and instituted a de jure ban on corporal punishment but maintained most German labour policy south of what became the Red Line.Footnote17

It is reasonable to assume that the majority of the South Africans’ condemnations of German policy arose less from an altruistic attitude concerning human rights and rather more from intercolonial power politics within the changed international system of the League of Nations.Footnote18 Many South African magistrates in Namibia were in favour of the resumption of corporal punishment of Africans, agreeing with German farmers that it was a better deterrent against labour desertion than fines within a vagrancy system.Footnote19 Much native affairs legislation throughout the early South African period was, like that of the Germans before them, centred around labour procurement for white farmers and colonial industry. Concerning native reserves policy, even aspects as mundane as water infrastructure were framed as a labour issue: ‘[i]f the water-facilities [in the reserves] are improved, more natives will be able to go out to work. The natives are only too ready to make use of the excuse of water drawing, and the improvement of the water-facilities will take this weapon out of their hands’.Footnote20 As Gijs Hofmeyr, the first civilian Administrator of SWA during the South African period, noted: the ‘native question … is synonymous with the labour question’ in Namibia.Footnote21

The conflation of the ‘labour question’ and the ‘native question’ is not unique to Namibian history; it has broader applicability. Frederick Cooper has noted, with reference to British and French labour policy, that, for much of the colonial period, the ‘labour question’ entailed officials’ calculations of how many workers could be recruited and how much coercion and compulsion a ‘civilised’ administration could use in obtaining such workers.Footnote22 In Namibian historiography, we have several surveys of how the ‘native question’ and the ‘labour question’ were indeed synonymous. Concerning the German colonial period, Helmut Bley has explored the confluence of labour legislation and native policy in the post-genocide German period, revealing both the fundamental reliance of settlers upon a (now diminished) local labour supply and conflicts between settlers and the government in Berlin over the best way to legislate and enforce legislation.Footnote23 In addition, Jürgen Zimmerer has explored the history of the so-called Eingeborenenpolitik, including labour legislation, noting that the transformations often attributed to post-genocide contexts have pre-1903 origins, such as masters–servants laws.Footnote24 Concerning the South African colonial period, Jeremy Silvester, focusing on southern Namibia, has noted how reserve policy was fundamentally about meeting district-level labour shortages rather than maintaining Nama cultural and legal institutions. Despite these restrictions, Nama farm employees still managed to maintain a degree of independence by negotiating work-for-grazing arrangements to build up flocks.Footnote25 Along similar lines, we learn in Wolfgang Werner’s study on central and eastern Namibia that colonial policy in the early South African period was often framed in response to an increased tendency of ‘self-peasantisation’ among Herero pastoralists, who sought to remove themselves from waged labour and squat on crown lands to build up cattle herds.Footnote26 These studies, and others conducted in the immediate aftermath of Namibian independence, were among the first to approach the topic of the ‘labour question’ in Namibian history. In them, conflict was often framed as a direct opposition between colonial administrators seeking to legislate labour hire and Africans seeking to maintain self-sufficient pastoral lives in the reserves.

If the ‘labour question’ in Namibian history was partially the quest by colonial powers to secure labourers for white farms and industries, then a central component of resolving it was deemed to be the importation of migrant labourers.Footnote27 This theme is not unique to Namibian history; migrant labour is a trend across African and global history, structurally influencing both the sending areas and the work destinations.Footnote28 Furthermore, because migrant labour under colonialism often leaves a fairly clear paper trail – in a way that local labour may not – it is a fruitful avenue of research for economic and labour historians and social scientists, especially in southern Africa, where the practice was most common.Footnote29 This has been the case in Namibian historiography as well.

Since most long-distance labour migration throughout Namibian history involved the northern Namibian Ovambo kingdoms, the majority of literature about migrant labour deals with these areas.Footnote30 Ernst Stals was among the first to publish on the topic, drawing from German colonial archives in Windhoek, Rhenish mission records in Wuppertal and published correspondence of Finnish missionaries who served in Ovamboland. Despite breaking new ground, his study was ultimately marred by diffusionist understandings of cultural and economic change.Footnote31 Fritz Wege, an East German scholar, also considered migrant labour in his Marxist exploration of the birth of a Namibian working class, based largely on German colonial records at Potsdam.Footnote32 Finnish researchers were able to make better use of these difficult-to-read missionary records, offering much more nuanced local histories of the economic relationships between Ovambo polities and their colonial neighbours.Footnote33 With the opening of colonial archival resources about Ovambo migrant labour from the mid 1980s, non-Finnish scholars were able to contribute to these debates.Footnote34 These historiographical advances were crucial to understanding migrant labour in Ovamboland, as these new archival sources were complemented by increased access to oral history informants in the aftermath of the Border War. Patricia Hayes, for example, showed that, while Ovamboland was envisaged as the panacea to labour shortages in post-genocide Namibia, colonial officials still struggled to obtain sufficient workers to meet demands.Footnote35 In her important work, Meredith McKittrick has shown that migrant labour and Christian missionary activity in Ovamboland in the first half of the 20th century strained not only subsistence economies but also social relations, creating gendered and intergenerational tensions over access to resources and the definition and responsibilities of family.Footnote36

These works on the history of Ovamboland complemented studies of the Police Zone, many of which were also completed in the immediate aftermath of Namibian independence.Footnote37 However, as Giorgio Miescher has noted, this fruitful period of Namibian historiography faced difficulties building broader narratives from ultimately local or ethnic-based histories.Footnote38 While much of the reason for ethnically framed histories deals with the structure of the colonial archive, practitioners of social, cultural and economic history must take great care in avoiding reproducing the same immutable ethnic conceptualisations of the apartheid period. Following Miescher’s move to examine the Red Line, authors in this special issue emphasise the importance of analysing labour north and south of it – and across other colonial boundaries – in the same frame. It is tempting to write about the long-distance migrant labour recruitment policies and schemes of SWANLA and its predecessors as separate phenomena from recruitment methods for Africans from the Police Zone. While the Red Line did administratively separate the Police Zone from the northern native reserves, this administrative border was a porous one, and debates concerning local labour policy and migrant labour policy were intertwined. Jeremy Silvester’s study of the intersections between reserve policy in southern Namibia and territory-wide labour policies was among the first to show the importance of considering both migrant and non-migrant workers in a study of a given region.Footnote39 Investigations of the ‘labour question’ in Namibia must inevitably move back and forth across the Red Line and further afield to other African countries, colonies and territories.Footnote40

While these works – concerning both the Police Zone and beyond the Police Zone – broke new ground and allowed historians to ask new questions about labour in Namibian history, much more empirical work needs to be done, especially concerning the second half of the 20th century, when apartheid governance structures were implemented in Namibia. Furthermore, economic and labour historians of Namibia must be willing to move beyond the boundaries of the territory, applying new scales to the study of labour migration, labour policy and labourers’ world views. Namibian labour history was not – and is not – bound by the Orange, Okavango, and Kunene rivers.

New Scales: Studying Labour Locally, Regionally and Globally

Breaking from the existing local and national(ist) historical narratives of Namibian labour necessitates new methodologies and scales that have relevance across boundaries and borders. Practitioners within the recent field of GLH have noted the need to re-evaluate the role of the nation state within labour history.Footnote41 While not abandoning its importance, they urge scholars to reconsider its place in labour history methodology. No longer is it sufficient to write of a workers’ movement from Namibia, Ghana, Argentina, and so on; in the same way that commodities produced by workers move across national borders and continents, so do the workers themselves and the ideas that shape their lives. What makes a ‘Namibian worker’? Labour history, while often grounded in local contexts, is inherently a regional and global field that must be cognisant of the flows of workers, commodities, ideologies and the structural transformations in capitalism that condition these flows.

Besides its important conceptual goals of decentring labour history from the ‘classical worker’ (white, male, industrial, wage-earning proletarian),Footnote42 GLH is in part a methodological game of scales. At its broadest, the ‘global’ in GLH necessitates examining the transformations (intensification or weakening) of interactions between world regions and the structural conditions that give rise to these.Footnote43 GLH is more than just following the most mobile sectors of a given economy (transport and maritime workers, for example);Footnote44 it extends beyond tracing the interconnections in global commodity exchanges prominent within the ‘new history of capitalism’ school.Footnote45 GLH necessitates investigation into the ways in which global transformations in economic ideologies and the technologies of production and governance shape a variety of commodified labour relations.Footnote46 However, GLH practitioners must be careful not to lose sight of the local; as Sanjay Subrahmanyam writes, it is ‘impossible to write a global history “from nowhere”’.Footnote47 No matter how comprehensive archival digitisation projects may become, global (labour) history ultimately requires intensive place-based research. Transnational and international connections and transfers are important not simply because they connect and transfer; rather, they are significant because they explain local power structures and embedded social dynamics.Footnote48 As John-Paul A. Ghobrial notes, ‘nobody wants their history, their city, and their community to be reduced to a mere way station along the path of a global flow’.Footnote49

By returning to the questions of work, production and ideologies and governance concerning work and production, GLH seeks to balance multiple scales: the global, regional and local. This can sometimes be in line with classic Italian-style microhistories, where global processes and exchanges are scaled down and local sources are carefully read and reconstructed to focus on social constraints and social dynamics, which may themselves have global roots.Footnote50 While there have been trends to use microhistory as a means to reject structural tendencies and emphasise the utter uniqueness of place and context,Footnote51 microhistory need not run from global structures. Christian De Vito and Anne Gerritsen have built on this to argue for a micro-spatial historical method to cross the divide between global and local by utilising micro-analysis in combination with a ‘spatially aware’ approach; this allows for analysis not confined to a single location and one which pushes against viewing localities as ‘self-sufficient units’.Footnote52 At a descriptive level, GLH draws from microhistorians in its desire to describe empirically forms of labour relations which may not align with the classical ‘double free’ industrial proletarian model. But, at the same time, there is a need to contextualise these ‘non-traditional’ forms of commodified labour as reflective of particular capitalist structures, enabling comparison at different analytical scales. GLH seeks to balance the scales; the uniqueness of local labour relations is often shaped by (and potentially itself shapes) global economic developments and transformations in capitalism itself.

Scholars of labour relations in southern Africa have been aware of the limitations of ‘classical’ definitions of the working class for some time. Marxist works from the 1970s on migrant labour in South Africa and beyond recognised that circular labour migrants did not fit neatly within a typical proletarian model. Claude Meillassoux and Harold Wolpe – perhaps the two most prolific scholars in this field – powerfully argued that the very nature of labour migration meant that crucial aspects of the cost of labour power were not being paid by capitalist employers. Capitalists paid the cost of day-to-day reconstitution of the worker himself, but the costs of the maintenance of the worker during times of unemployment, and the care of children and elderly ex-workers, were placed upon the non-capitalist sending areas.Footnote53 In essence, since migrant workers were paid as bachelors, the agricultural and child-rearing capacity of those left behind acted as a subsidy for capitalists. These analyses ultimately gave birth to the term ‘super-exploitation’, whereby the support networks in the sending areas were also exploited by capital.Footnote54 They argued that it was in the interest of capital to maintain a weakened ‘pre-capitalist’ world to subsidise the reproduction of labour power of semi-proletarians. Capitalist expansion was limited not simply to the brutal processes of primitive accumulation. Their analysis was in part linked to a growing recognition that the foundations of capital accumulation were globally changing, leading to a rise in migrant labour and offsetting the costs of production upon the workers themselves, and southern Africa was seen to be at the forefront of this transformation.Footnote55

While Wolpe and Meillassoux’s writings were received fairly well throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, they garnered their fair share of criticism: most concerning an overly structuralist framing and insufficient historical data. They were not balancing the scales very well. Social scientist Archie Mafeje criticised Wolpe and some of his student followers for the thick brush-strokes painted using their theory, often a result of writing from exile without conducting extensive fieldwork.Footnote56 Furthermore, Mafeje correctly noted that this risked missing both the changing nature of apartheid’s relationship with the homelands and class conflict within the homelands themselves. Bozzoli echoed these sentiments, noting that class struggle is often what determined wage rates, and Wolpe’s structural analysis leaves no room for this. Furthermore, in Bozzoli’s critique of Marxist scholars like Wolpe, she noted that the transfer of labour burdens to women did not originate with South African capitalism but has roots in struggles over gendered production during the pre-colonial period. The usefulness of this gendered inequality to capitalist accumulation need not determine causality and responsibility.Footnote57 Bozzoli’s critique underscores the need to examine gendered struggles over labour as central to the development of economic structures across the pre-colonial/colonial divide.Footnote58 Echoing calls for additional grounded historical contextualisation, Donham and Cooper each held that, while there is a great deal of importance to the questions that Wolpe and Meillassoux ask – namely, how to come to terms with the dominance of capitalism in situations where wage labour in a classical sense is only partially relevant – this is a question which cannot be looked at simply through structural logics of capitalism. The global scales of capitalist transformations must be complemented by local scales of deep empirical analysis.Footnote59

Much of the rise of the social history movement within South African historiography has its roots in unease with their ‘radical’ Marxist colleagues. From the late 1970s and early 1980s, the History Workshop at the University of the Witwatersrand pioneered a community-oriented historical programme, seeking to write the ‘history from below’, namely the history of black South Africans previously neglected in historical studies.Footnote60 Most History Workshop participants and scholars were uninterested in the theoretical debates that Wolpe, Meillassoux and their students thought were crucial to understanding the economic history of South Africa.Footnote61 These social historians believed that the Marxists viewed individuals, as E.P. Thompson phrased it, simply as ‘träger or supports of [social] process’.Footnote62 Therefore, a deeper empirical uncovering of the history and lives of ‘ordinary people’ was necessary to democratise historical research.

Some critics of the Wits History Workshop argued that the social historians moved too far away from the Marxist scholars’ engagement with global scales of historical causality in the pursuit of ‘bottom-up’ perspectives. While this criticism should not negate the value of social historians’ attention to the experiences of ordinary people, an over-emphasis on experience can prevent adequate analysis of large-scale processes and tendencies. Mike Morris, a follower of Wolpe’s frameworks, has argued that the social historians’ ‘view from below’ as a counter to traditional ‘big men’ histories still maintains a micro-scale mode of explanation that does not attend to structural relations and class forces in South(ern) Africa beyond a Thompsonian understanding of ‘experience’.Footnote63

Ultimately, social and cultural historians won the academic fight. Especially in the context of a rising heritage industry in southern Africa, deep questions relevant to economic and labour historians were often put on the back burner. This meant, in South African historiography, that the central debates concerning the structural relationship between the sending areas and the work site were not fully resolved, merely left behind. These questions remain crucial for GLH, however; while some of the language has been transformed, the classic questions concerning partial proletarianisation, varieties of commodified labour forms and the structural conditions of capitalism are a central part of GLH’s agenda.Footnote64 In the context of increased access to archival sources and oral informants, new historical research has the capacity to bring in under-represented voices (as the social historians did) not just for representation’s sake but because they help to illuminate broader regional and global issues and points of disjuncture and conjuncture.Footnote65 Historians of labour must combine the local scales with regional and global ones.

Namibian historiography was never divided into the liberal/radical/Wits school battle lines of South African historiography. The lack of any tertiary institutions within the territory until the 1980s – then still focused on technical/vocational education – means that most academic debates concerning foundational issues in Namibian economic/labour history were happening far from the territory. Archives and oral informants were difficult to access in the context of the apartheid border war, and the country was not able to develop a local class of historical researchers until after independence. Furthermore, South African historians’ inward-gazing research agendaFootnote66 meant that Namibia was neglected from these important historiographical debates, and it is necessary for Namibianists to look into some of these central debates relevant to southern African history more broadly. While there was a short period of interest during the early 1990s in the history of the ‘labour question’ in Namibia, much more additional research must be conducted using the increased archival capacities of the post-apartheid state. The articles in this special issue draw from new archival records and oral testimonies in re-centring labour in Namibian history.

Re-Centring Labour and Labourers: Our Contributions

While it is beyond the scope of this special issue to close the book on these debates, our articles add empirical data and analysis on the relationship between colonial/apartheid capitalism and labour policy in Namibian history. The ‘labour question’ is a relevant analytical lens through which to examine Namibian history, but it is important to remember that the solution to the ‘labour question’ was ultimately a moving target, changing alongside transformations in colonial/apartheid capitalism and other forms of production. Our articles, collectively and individually, consider (1) the structural relationship between migrant labour systems in Namibian history and the relationship between migrant and non-migrant labour flows; (2) ways in which the Namibian ‘labour question’ was not bound by the borders of the nation state; (3) the variety of forms of ‘free’ and ‘unfree’ labour that exist within Namibian history and the structural causes of them; (4) the ways in which the lived experiences and actions of workers themselves shaped and challenged labour policy and its implementation. These contributions draw on new archival documentation from Namibia and abroad, frameworks from global history, GLH, transnational history, microhistory, and oral testimonies of (ex-)workers and relevant parties.

Kai F. Herzog’s article draws from colonial records in South Africa, Germany and Namibia to explore the history of convict labour in the Cape–Namibia border region during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Herzog uses colonial policies surrounding convict labour, the implementation of said policies and the actual labour performed by convicts as a lens through which to examine the issues of labour mobilisation and control in this trans-colonial frontier zone. Globally circulating ideas addressing the ‘labour question’ and compulsion in post-slavery colonial Africa led both the government of the Cape Colony and the administration of German South West Africa to pursue shared yet differing approaches towards convict labour, aiming to manage the labour demands of the emerging settler economies either side of the border. Moreover, Herzog reveals the disparate ways in which colonial violence was used to achieve these goals and how it shaped the consolidation of settler colonialism in the region.

William Blakemore Lyon reveals some of the global economic connections present in Namibia from its earliest days as a German colony by examining the history of west African migrant workers in Namibia. Contracted through the global connections of German shipping companies, these workers (mostly from Liberia) were employed as longshoremen at Lüderitz and Swakopmund and were central to the construction and maintenance of the colony's infrastructure. Lyon also explores the social trajectory of this group of workers and their relations to local black Namibians; these west Africans played a key role in early Namibian Garveyism and Pan-Africanism. Lyon ultimately shows that west African labourers contributed more than just their labour power to the Namibian economy, and they remained connected to their former lives in Liberia.

Stephanie Quinn’s article seeks to place Namibia’s contract labour system in the broader contexts of labour migration in southern Africa and South African empire-building. She argues that the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (WNLA) and SWANLA’s transnational migrant labour networks were an important way that South Africa and SWA projected regional power in the 20th century. WNLA and SWANLA have primarily been seen for their role in providing cheap migrant labour and, in SWANLA’s case, motivating anti-colonial resistance, but WNLA and SWANLA controls on Africans’ mobility and livelihoods served as templates for apartheid influx control. The article then examines African engagements with urban influx control infrastructures and practices on a small scale in the port and fishing town of Walvis Bay. Long-term urban residents of location houses and northern contract labourers living in the municipal compound identified their relationship with the municipality – mediated through payments for housing and basic services – as a crucial expression of colonial power. Urban infrastructure thus formed a site of contestation between the local state and African urban residents across the location–compound divide, although members of the two groups understood the implications of their relationship to the municipality very differently.

Kletus Muhena Likuwa’s article looks at migrant labour from the perspective of the sending area (in this case, Kavango), noting that, while the sending area did play a distinct role in the reproduction of the labour power of migrants, this was not simply an economic ordeal related to subsistence production. Rather, residents of Kavango were more concerned with the ways in which observance of cultural taboos within the region could affect the welfare and fortune of migrant workers in the Police Zone. The sending area did not simply reproduce the labour power of men by supporting women, children and the elderly (in part) through additional agricultural duties, but there were additional cultural and religious duties as well. Furthermore, Likuwa reminds readers of the need to consider gender dynamics in understanding migrant labour regimes.

Bernard C. Moore’s article explores the fluctuating labour demands and dilemmas on karakul sheep farms in southern Namibia, noting how sheep farmers became increasingly dependent upon migrant workers coming in from southern Angola. Portuguese colonial development schemes in the region threatened this flow, causing white farmers to intensify installing labour-saving infrastructure and mechanising farm production, reducing the need to hire local Nama labour for full-time farm positions as well. Moore shows that, in this context, there is a degree of validity to Wolpe’s and Meillassoux’s arguments, but this need not be simply a migrant labour phenomenon – rural capitalism in Namibia shaped both migrant and non-migrant labour flows concurrently.

In her study of Namibia’s mining industry in the 1970s and 1980s, Saima Nakuti Ashipala reveals that economic transformations in the global mining industry, as well as changes in the way apartheid was administered in Namibia, created bottlenecks in the traditional SWANLA labour recruitment methods. The increasing mechanisation of mines – alongside the flight of skilled white workers from Namibia to South Africa – meant that it was no longer sufficient for mines simply to procure unskilled labour from the sending areas; there was an increasing need for skilled black labour not engaged in circular migration. In mines singly and collectively, steps were taken to raise workers’ skills through foundations funded by the mining companies. This still maintained the subservient position of black employees, however.

Each of the six articles in this special issue confronts labour in Namibia and its frontiers (both north and south) following the precepts of GLH and the examples set in the recent ILO General Labour History of Africa. Regrettably, Namibia is barely mentioned in that work. In responding to this oversight, it is our goal not just to address the nuances of Namibian labour history but also to set the stage for further regional and trans-regional comparisons and entanglements.Footnote67

Conclusion: Two Strikes

On the morning of Saturday the 14th of October, forty-one Native dock workers at Lüderitz refused to off-load an Italian boat. The port authorities telephoned the police, and then the police escorted the Natives to the station, where the chief constable noted that if they do not do their jobs, they will be held in custody indefinitely. The workers thought it over, and within an hour they all decided to return to work. The boat was unloaded within ninety minutes, and no workers were held in custody. The Natives gave the reason for their refusal to work that they believe the Italians are planning war against Abyssinia.Footnote68

Local labour relations might not be very local at all. What occurs at a given work site is the culmination of a broad array of ideas, structures and movements. While historians must begin their investigations in a particular geographical locale, linkages connect the work site to global processes. This section’s epigraph, concerning a brief report of a short-lived work stoppage, reveals the degree of knowledge that workers had of global events and the structural implications that faraway actions might have upon their own lives. The Italian invasion of Ethiopia would not occur until the following month, yet Lüderitz’s African dockworkers – presumably Kru, Ovambo and Nama labourers – understood the Welwel border incident as the League of Nations failing to uphold Ethiopia’s sovereignty and siding with the European colonial power. As residents of a League of Nations ‘C’-class mandate, Namibian workers in Lüderitz are likely to have understood that the League’s failure in north-east Africa affected South West Africa; thus they refused to unload cement from the SS Savoia.

Some workers’ actions are spontaneous and end quickly, like the September 1935 work stoppage in Lüderitz. Others are the culmination of longer-term processes that go back decades. The declassification and opening of new archival materials in Namibia, South Africa, and elsewhere enables historians to (1) re-contextualise and better establish causality for workers’ action, and (2) understand more deeply the structural processes conditioning the recruitment of labourers and the work that they perform. Regarding the first point, we must be able to distinguish between spontaneous, short-term political action and long-term structural causality. The assumption within Namibian historiography of the continuity of labour activism and political activity has conflated the famous 1971–72 contract workers’ strike with the rise of SWAPO membership in contract workers’ ranks, with some even alleging that SWAPO itself arranged for the strike.Footnote69 As Quinn shows in her article, the roots of the strike are much deeper than the history of SWAPO, and officials in Pretoria, Windhoek and various localities in Namibia planned the replacement of SWANLA long before the strike – not least in response to workers’ day-to-day subversions of SWANLA controls on their mobility and livelihoods.

It is important for historians to re-investigate key moments in Namibian labour history such as these to tease out the complex relationship between, on the one hand, labour conditions and associated activism and, on the other hand, nationalist political activism. In this way, scholars can garner a better picture of (1) the structural conditions of the Namibian economy, (2) the political conditions shaping the ‘labour question’, and (3) the lived experiences of workers themselves. The articles in this special issue seek to break new ground in addressing these issues, and each opens new vistas toward future local, regional and global perspectives on Namibian labour history.

Notes

1 Newmont also owned 57.5 per cent of O’Okiep Copper Mine in Namaqualand, reaching as high as 67 per cent. See Michigan State University (MSU) African Activist Archives (AAA): R. Kramer and T. Hultman, ‘Tsumeb: A Profile of United States Contribution to Underdevelopment in Namibia’, Report to the Corporate Information Center, National Council of Churches, New York (April 1973); and Consolidated Gold Fields, Plc.: Partner in Apartheid (London, Counter Information Services, 1986), pp. 14–16. See also: L. Walker, ‘States in Waiting: Nationalism, Internationalism, Decolonization’ (PhD thesis, Harvard University, 2018), pp. 124–8; J.M. Smalberger, Aspects of the History of Copper Mining in Namaqualand,1846–1931 (Cape Town, C. Struik, 1975), pp. 123–4; J.H. Morris, Going for Gold: The History of Newmont Mining Corporation (Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 2010), pp. 47–53.

2 National Archives of Namibia (NAN) Archives of the South West Africa Secretariat: AS-Series (SWAS) 372 File AS.50/2/3/2 (v. 2): M.D. Banghart and F.A. Scheck ‘Memorandum: Conference with Four Representatives of SWAPO’ – 26 September 1960.

3 See M. Wallace, A History of Namibia: From the Beginning to 1990 (London, Hurst, 2011), pp. 245–8.

4 A. Toivo ya Toivo, interviewed by B.C. Moore, Windhoek, August 2012. K. Hishoono, interviewed by B.C. Moore, Windhoek, July 2012. B. Ulenga, interviewed by B.C. Moore, Windhoek, August 2012.

5 The foundation date of SWAPO is debated in Namibian historiography; however, some of the earliest party documents are housed at the NAN in Windhoek, and they outline the history along these lines. NAN SWAS 372 File AS.50/2/3/2 (vol. 2): S. Nujoma and M. Kerina, ‘A Brief History of the South West African People’s Organisation’ – 1 August 1960.

6 SWAPO of Namibia, To Be Born a Nation: The Liberation Struggle for Namibia (Luanda, SWAPO Department of Information and Publicity, 1981), pp. 57–85, 169–76; Z. Ngavirue, Political Parties and Interest Groups in South West Africa (Basel, Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 1997 [1972]), pp. 229–39. There were some earlier academic engagements with labour policies, albeit from a far less condemnatory perspective. See M.J. Olivier, ‘Inboorlingbeleid en -Administrasie in die Mandaatgebied van Suidwes-Afrika’ (D.Phil thesis, Stellenbosch University, 1961), pp. 250–320; F.E. Rädel, ‘Die Wirtschaft und die Arbeiterfrage Südwestafrikas: von der Frühzeit bis zum Ausbruch des zweiten Weltkrieges’, (D.Comm thesis, Stellenbosch University, 1947); E.L.P. Stals, ‘Die Aanraking tussen Blankes en Ovambo’s in Suidwes-Afrika, 1850–1915’, (D.Phil thesis, Stellenbosch University, 1967). See also E.L.P. Stals, Duits-Suidwes-Afrika na die Groot Opstande: ‘n Studie in die Verhouding tussen Owerheid en Inboorlinge (Pretoria, Staatsdrukker, 1984), pp. 35–59.

7 R.D. Moorsom, ‘Underdevelopment, Contract Labour and Worker Consciousness in Namibia, 1915–1972’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 4, 1 (1977), pp. 52–87. R.D. Moorsom, ‘Colonisation and Proletarianisation: An Exploratory Investigation into the Formation of the Working Class in Namibia under German and South African Colonial Rule to 1945’, (MA dissertation, University of Sussex, 1973). R.D. Moorsom, ‘Labour Consciousness and the 1971–2 Contract Workers’ Strike in Namibia’, Development and Change, 10, 2 (1979), pp. 205–31.

8 International Labour Organisation, Labour and Discrimination in Namibia (Geneva, ILO, 1977). In addition, Revd Michael Scott, one of the early advocates of Namibian liberation at the UN and beyond, long acknowledged the strong connections between labour exploitation and political action. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, this became central in international anti-apartheid knowledge about Namibia, exhibited, for example, in various protest films, notably: Michael Scott’s Civilisation on Trial (1950), the UN’s Colonialism: A Case Study, Namibia (1975), Frank Morrow’s Free Namibia (1978), and the UN’s Namibia: Independence Now! (1985).

9 Some academic accounts include, G. Bauer, ‘Labour Relations in Occupied Namibia’, in G. Klerck, A. Murray and M. Sycholt (eds), Continuity and Change: Labour Relations in Independent Namibia (Windhoek, Gamsberg Macmillan, 1997) pp. 55–78. A.D. Cooper, ‘The Institutionalisation of Contract Labour in Namibia’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 25, 1 (1999), pp. 121–38. K. Likuwa and N. Shiweda, ‘Okaholo: Contract Labour System and Lessons for Post-Colonial Namibia’, Mgbakoigba: Journal of African Studies, 6, 2 (2017), pp. 26–47.

10 Okaholo is the Oshiwambo term for the metal necklace/bracelet identifying migrant workers. As a start, see S. Nujoma, Where Others Wavered: The Autobiography of Sam Nujoma (London, PANAF Books, 2001), pp. 26–36; J. ya Otto, Battlefront Namibia: An Autobiography (Westport, Lawrence Hill and Co., 1981), pp. 13–26; H.V. Ndadi, Breaking Contract (Windhoek, Archives of Anti-Colonial Resistance and the Liberation Struggle, 2009 [1974]), pp. 9–66. Also note the keynote speech by former president Hifikepunye Pohamba on 7 February 2018 at the launch of E.N. Namhila’s book Little Research Value: African Estate Records and Colonial Gaps in a Post-Colonial National Archive (Basel, Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 2018).

11 Journal of Southern African Studies, 41, 3 (2015), special issue, ‘The South African Empire’.

12 D. Henrichsen, G. Miescher, C. Rassool and L. Rizzo, ‘Rethinking Empire in Southern Africa’, in ibid., pp. 431–5.

13 M. van der Linden, ‘Globalising Labour Historiography: The IISH Approach’, working paper, International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam, 2002).

14 M. van der Linden, Workers of the World: Essays toward a Global Labour History (Leiden, Brill, 2008), p. 373.

15 M. van der Linden, ‘The Promise and Challenges of Global Labour History’, International Labour and Working-Class History, 82 (2012), p. 62.

16 The Police Zone was the legal term defining the areas of white settler colonialism, namely the areas of southern and central Namibia south of the so-called Red Line. G. Miescher, Namibia’s Red Line: The History of a Veterinary and Settlement Border (New York, Palgrave, 2012), pp. 69–100. The South African offensive against the Kwanyama leader Mandume ya Ndemufayo was crucial to the consolidation of South African power over labour in northern Namibia. See P. Hayes, ‘A History of the Ovambo of Namibia, c.1880–1935’, (PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 1988), pp. 178–233. Concerning the transition period to South African rule, see J-B. Gewald, ‘Near Death in the Streets of Karibib: Famine, Migrant Labour, and the Coming of Ovambo to Central Namibia’, Journal of African History, 44, 2 (2003), pp. 211–39.

17 NAN Archives of the Secretary of the Protectorate, 1915–1920 (ADM) 043 File 567/2 (vol. 3): Memorandum Concerning the Laws Affecting the Native Population in the Protectorate of South West Africa (August 1916).

18 See J. Silvester and J-B. Gewald, ‘Footsteps and Tears: An Introduction to the Construction and Context of the 1918 “Blue Book”’, in Silvester and Gewald (eds), Words Cannot Be Found: German Colonial Rule in Namibia, An Annotated Reprint of the 1918 Blue Book (Leiden, Brill, 2003), pp. xiii-xxxvii.

19 NAN ADM 041 File 567/2 (vol. 1): Magistrate Karibib to Secretary for SWA ‘Attitudes of Natives: Karibib District’ – 18 December 1917.

20 NAN AP 5/7/2: Report of the Native Reserves Commission, 1928. Note that this report was a follow-up to the 1921 commission of the same name.

21 NAN AP 2/3: Union of South Africa, South West Africa Territory: Report of the Administrator for the Year 1920 (Cape Town, 1921), p. 13.

22 F. Cooper, Decolonization and African Society: The Labor Question in French and British Africa (New York, Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 1–2.

23 H. Bley, Namibia Under German Rule (Hamburg, LIT Verlag, 1996), pp. 226–48.

24 J. Zimmerer, Deutsche Herrschaft über Afrikaner: Staatlicher Machtanspruch und Wirklichkeit im kolonialen Namibia (Hamburg, LIT Verlag , 2002), pp. 9–10, 28, 68–71.

25 J. Silvester, ‘Black Pastoralists, White Farmers: The Dynamics of Land Dispossession and Labour Recruitment in Southern Namibia, 1915–1955’ (PhD thesis, SOAS, University of London, 1993), pp. 28–54.

26 W. Werner, No One Will Become Rich: Economy and Society in the Herero Reserves in Namibia, 1915–1946 (Basel, P. Schlettwein, 1998), pp. 57–65.

27 Concerning the ‘labour question’ as an evolving colonial preoccupation, see F. Cooper, Decolonization and African Society.

28 S. Stichter, Migrant Laborers (New York, Cambridge University Press, 1985). F. Manchuelle, Willing Migrants: Soninke Labor Diasporas, 1848–1960 (Oxford, James Currey, 1997).

29 J. Crush, A. Jeeves and D. Yudelman, South Africa’s Labour Empire: A History of Black Migrancy to the Gold Mines (Cape Town, David Philip, 1991). C. Murray, Families Divided: The Impact of Migrant Labour in Lesotho (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1982).

30 Henrichsen has shown, however, that there were existing labour flows between pre-colonial central Namibia and the Cape Colony. D. Henrichsen, ‘“Damara” Labour Recruitment to the Cape Colony and Marginalisation and Hegemony in Late-19th Century Central Namibia’, Journal of Namibian Studies, 3 (2008), pp. 63–82. See also J-B. Gewald, ‘The Road of the Man Called Love and the Sack of Sero: The Herero–German War and the Export of Herero Labour to the South African Rand’, Journal of African History, 40, 1 (1999), pp. 21–40.

31 E.L.P. Stals, ‘Die Aanraking tussen Blankes en Ovambo’s’, pp. 190–234 especially.

32 F. Wege, ‘Die Anfänge der Herausbildung einer Arbeiterklasse in Südwestafrika unter der deutschen Kolonialherrschaft’, Jahrbuch Für Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 10, 1 (1969), pp. 183–222.

33 See M.L. Kouvalainen, ‘Ambomaan siirtotyöläisyyden synty’ (Master’s dissertation, University of Helsinki, 1980). H. Siiskonen, Trade and Socio-Economic Change in Ovamboland, 1850–1906 (Helsinki, Suomen Historiallinen Seura, 1990), pp. 229–37. M. Eirola, The Ovambogefahr: The Ovamboland Reservation in the Making: Political Responses of the Kingdom of Ondonga to the German Colonial Power, 1884–1910 (Rovaniemi, Pohjois-Suomen Historiallinen Yhdistys, 1992), pp. 213–16.

34 R. Strassegger, ‘Die Wanderarbeit der Ovambo während der Deutschen Kolonial-Besetzung Namibias. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Wanderarbeiter auf den Diamantenfeldern in den Jahren 1908 bis 1914’ (PhD thesis, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, 1988). P. Hayes, ‘The Failure to Realise Human Capital: Ovambo Migrant Labour and the Early South African State, 1915–1938’, The Societies of Southern Africa in the 19th and 20th Centuries (London, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, 1993). Also see the works by R. Moorsom and A. Cooper, among others.

35 P. Hayes, ‘A History of the Ovambo of Namibia’, pp. 145–56, 273–90, 332–42.

36 M. McKittrick, To Dwell Secure: Generation, Christianity, and Colonialism in Ovamboland (Portsmouth, Heinemann, 2002), pp. 170–99. See also N. Shiweda, ‘Yearning to Become Modern? Dreams and Desires of Ovambo Contract Workers’, Journal of Namibian Studies, 22 (2017), pp. 81–98. For further insights into the confluence of struggles over labour and gender relations, see P. Hayes, ‘The “Famine of the Dams”: Gender, Labour, and Politics in Colonial Ovamboland, 1929–1930’, in P. Hayes, J. Silvester, M. Wallace and W. Hartmann (eds), Namibia Under South African Rule: Mobility and Containment, 1915–46 (Oxford, James Currey, 1998), pp. 117–48; L. Rizzo, Gender and Colonialism: A History of Kaoko in Northwestern Namibia, 1870s–1950s (Basel, Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 2012); M. Wallace, Health, Power, and Politics in Windhoek, Namibia, 1915–1945 (Basel, P. Schlettwein, 2002).

37 See W. Werner, ‘An Economic and Social History of the Herero of Namibia, 1915–1946’, (PhD thesis, University of Cape Town, 1989); R.J. Gordon, The Bushman Myth: The Making of a Namibian Underclass (Boulder, Westview Press, 1991).

38 Miescher, Namibia’s Red Line, pp. 5–7, 195–6.

39 Silvester, ‘Black Pastoralists, White Farmers’.

40 Namibia was also a destination for migrant workers coming from South Africa, Angola, west Africa and other locations. See articles by Moore, Quinn, Lyon and Herzog, elsewhere in this issue. See also W. Beinart, ‘“Jamani” Cape Workers in German South West Africa, 1904–12’', in W. Beinart and C. Bundy (eds) Hidden Struggles in Rural South Africa: Politics and Popular Movements in the Transkei and Eastern Cape, 1890–1930 (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1987), pp. 166–91; U. Lindner, ‘Transnational Movements between Colonial Empires: Migrant Workers from the British Cape Colony in the German Diamond Town of Lüderitzbucht’, European Review of History, 16, 5 (2009), pp. 679–95. For information on European, mainly Italian, migrant labour to colonial Namibia, see Lyon’s in-progress doctoral thesis at Humboldt University of Berlin, provisionally titled, ‘Migrant Labor in Namibia under German and Early South African Rule, 1890–1925’.

41 M. van der Linden, Transnational Labour History: Explorations (Aldershot, Ashgate, 2003).

42 S. Amin and M. van der Linden, ‘Introduction’, in ‘Peripheral’ Labour? Studies in the History of Partial Proletarianisation (Amsterdam, Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, 1996), pp. 1–8. There are parallels between GLH’s questioning of classical labour categories and conceptual reconfigurations coming out of the subaltern studies movement in South Asia, although GLH remains slightly closer to variations of Marxist theory than subaltern studies. See S. Sinha, ‘Workers and Working Classes in Contemporary India: A Note on Analytical Frames and Political Formations’, in M. van der Linden and K.H. Roth (eds), Beyond Marx: Theorising Global Labour Relations of the Twenty-First Century (Leiden, Brill, 2014), pp. 145–72. See also C. Joshi, P.P. Mohapatra and R.P. Behal, ‘Dialogues Across Borders: Marcel van der Linden and the Association of Indian Labour Historians’, in K.H. Roth (ed.), On the Road to Global Labour History: A Festschrift for Marcel van der Linden (Leiden, Brill, 2018), pp. 9–16.

43 M. van der Linden, ‘The Promise and Challenges of Global Labor History’, International Labor and Working-Class History, 82 (2012), pp. 57–76.

44 See S.J. Rockel, Carriers of Culture: Labor on the Road in Nineteenth-Century East Africa (Portsmouth, Heinemann, 2006). L. Schler, Nation on Board: Becoming Nigerian at Sea (Athens, Ohio University Press, 2016).

45 See S. Beckert and C. Desan (eds), ‘Introduction’, in American Capitalism: New Histories (New York, Columbia University Press, 2018), pp. 1–32; S. Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York, Knopf, 2014); R.S. Gendron, M. Ingulstad and E. Storli (eds), Aluminum Ore: The Political Economy of the Global Bauxite Industry (Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 2013).

46 Van der Linden, Workers of the World.

47 S. Subrahmanyam, ‘On the Origins of Global History’, inaugural lecture at the Collège de France (20 November 2013), available at https://books.openedition.org/cdf/4200, retrieved 28 October 2020.

48 L. Putnam, ‘The Transnational and the Text-Searchable: Digitized Sources and the Shadows They Cast’, American Historical Review, 121, 2 (2016), pp. 377–402.

49 J-P.A. Ghobrial, ‘Introduction: Seeing the World Like a Microhistorian’, Past and Present, 242, suppl. 14 (2019), p. 10.

50 On Italian microhistory, see W. Sewell Jr., Logics of History: Social Theory and Social Transformation (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2005), pp. 73–4.

51 On this tendency, see J. de Vries, ‘Playing with Scales: The Global, the Micro, the Macro, and the Nano’, Past and Present, 242, suppl. 14 (2019), p. 25.

52 C.G. De Vito and A. Gerritsen (eds), Micro-Spatial Histories of Global Labour (Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), p. 2.

53 C. Meillassoux, Maidens, Meal, and Money: Capitalism and the Domestic Community (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1981 [1975]), especially pp. 100–101. H. Wolpe, ‘Capitalism and Cheap Labour Power in South Africa: From Segregation to Apartheid’, Economy and Society, 1, 4 (1972), pp. 425–56. See also H. Wolpe (ed.), The Articulation of Modes of Production (London, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980).

54 C. Meillassoux, ‘From Reproduction to Production: A Marxist Approach to Economic Anthropology’, Economy and Society, 1, 1 (1972), pp. 93–105.

55 See E. Mandel, Late Capitalism (London, Verso, 1976 [1972]), pp. 180–82.

56 A. Mafeje, ‘On the Articulation of Modes of Production’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 8, 1 (1981), pp. 123–38.

57 B. Bozzoli, ‘Marxism, Feminism, and South African Studies’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 9, 2 (1983), pp. 139–71.

58 This has been a fruitful avenue of research within gender and labour history in African contexts; see L. Lindsay, ‘“No Need … to Think of Home”? Masculinity and Domestic Life on the Nigerian Railway, c.1940–61’, Journal of African History, 39, 3 (1998), pp. 439–66; L. Lindsay, Working with Gender: Wage Labour and Social Change in Southwestern Nigeria (Portsmouth, Heinemann, 2003). J. Parpart, ‘The Household and the Mine Shaft: Gender and Class Struggles on the Zambian Copperbelt, 1926–64’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 13, 1 (1986), pp. 36–56; T. Barnes, ‘“So That a Labourer Could Live with His Family”: Overlooked Factors in Social and Economic Strife in Urban Colonial Zimbabwe, 1945–1952’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 21, 1 (1995), pp. 95–113.

59 D.L. Donham, History, Power, Ideology: Central Issues in Marxism and Anthropology (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1999), pp. 207–10. F. Cooper, ‘Africa and the World Economy’, in F. Cooper et al. (eds), Confronting Historical Paradigms: Peasants, Labor, and the Capitalist World System in Africa and Latin America (Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1993), p. 101.

60 P. Delius, ‘E.P. Thompson, “Social History”, and South African Historiography’, Journal of African History, 58, 1 (2017), pp. 3–17.

61 D. Posel, ‘Social History and the Wits History Workshop’, African Studies, 69, 1 (2010), pp. 29–40.

62 E.P. Thompson, The Poverty of Theory, or an Orrery of Errors (London, Merlin Press, 1995), p. 103.

63 M. Morris, ‘Social History and the Transition to Capitalism in the South African Countryside’, Review of African Political Economy, 15, 41 (1988), pp. 60–72.

64 Van der Linden, Transnational Labour History, p. 201. Amin and van der Linden (eds), ‘Peripheral’ Labour?

65 While not explicitly writing in defence of Wolpe and Meillassoux’s frameworks, Jock McCulloch’s work on health and disease in the South African gold mines adds empirical evidence to their arguments about capital externalising production costs upon homelands and foreign nations. After all, he was able to base his arguments on richer access to archival materials than Wolpe or Meillassoux, who were writing from exile. J. McCulloch, South Africa’s Gold Mines and the Politics of Silicosis (Oxford, James Currey, 2012), p. 161.

66 See JSAS, 41, 3 (2015), special issue, ‘The South African Empire’.

67 S. Bellucci and A. Eckert (eds), General Labour History of Africa: Workers, Employers, and Governments, 20th–21st Centuries (Geneva, ILO, 2019).

68 NAN Archives of the South West Africa Secretariat: A-Series (SWAA) 2450 File A.521/60: Magistraat Lüderitz to Sekretaris van SWA ‘Staking van Naturelle in die Hawe Lüderitz’ – 20 September 1935, trans. B.C. Moore.

69 University of Cape Town Special Collections, Simons Collection box 5: ‘Press Statement by the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) of Namibia, Lusaka’ – 4 February 1972. SWAPO itself claimed responsibility for the strike as a nationalist act in an early 1972 press statement.