Abstract

This article tracks the involvement of the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU) in the strike on the Lichtenburg diamond diggings of June 1928, during which 35,000 black workers downed tools. At the time, this was the second largest strike by black workers in South African history. This article adds to the literature on the strike in two ways. First, it argues that from mid 1927 (a year before the strike), the ICU began to pay attention to the plight of black workers and location residents on the Lichtenburg diggings and in the adjacent locations. When workers’ weekly wages were cut from 20 shillings to 12 shillings in June 1928, the ICU organised workers by picketing and mobilising workers to strike; by holding meetings to discuss their demands; and by negotiating with white diggers and state officials. A second contribution of the article is the argument it makes that recently unemployed workers and persecuted location residents joined the striking workers, broadening the composition of the body of strikers and the scope of the strike. The ICU managed to mobilise these workers and this became a hallmark of their activism in subsequent years. At the end of the strike, an agreement was reached between workers, the state, diggers and the ICU to pay 15 shillings – a less dramatic wage drop than proposed. The ICU’s role in the strike was so pronounced that in the months that followed it, the membership of the ICU exploded in towns across the Western Transvaal. This article argues that the strike was an outstanding achievement for the ICU in spite of its organisational decline towards the end of the 1920s.

Introduction

In June 1928, 35,000 black workers at the Lichtenburg diamond diggings embarked on a seven-day strike in response to an eight-shilling reduction in their weekly wage. This was, at the time, the second largest strike in South Africa’s history after the black mineworkers’ strike on the Rand in 1919–1920. The Lichtenburg strike was dubbed the ‘Kadalie Strike’ by white diggers, named after the charismatic leader of the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU), Clements Kadalie. This article provides an account of the ICU’s presence on the diggings in Lichtenburg between 1927 and 1930, focusing in particular on the June 1928 strike and the ICU’s role in it. Timothy Clynick, who has analysed the development of political consciousness among white workers on the diggings and the causes of the strike, notes how

the action of Black labourers to the growing pressure on wages and living conditions in general allows us a fascinating glimpse into the organisation and resistance of Blacks on the alluvial diggings, constituting an unwritten chapter in the social history of the Transvaal countryside.Footnote1

This article offers new perspectives on an underdeveloped aspect of the ICU’s organisational history and argues that the ICU played a pivotal role in the ‘unwritten social history’ of the strike. As well as Clynick, whose work on the political economy of the Lichtenburg diggings serves as important background to this article, this article draws on scholars who have contributed to the written history of the strike. Jack and Ray Simons briefly address the strike in their book Class and Colour, in which they describe the ICU’s role in the strike as a ‘glaring example of failure’.Footnote2 In his epic biography of sharecropper Kas Maine, Charles van Onselen provides a short chronology of the strike and the personalities involved but notes that the union ‘played a far less important role in the conflict than attributed to it by deeply resentful white employers’.Footnote3 Helen Bradford provides the most comprehensive account of the ICU’s role in the strike, giving a critical perspective on the organisation of black workers and the role of the ICU. She portrays the ICU as ‘out of touch’ with the demands and aspirations of striking workers.Footnote4 There is no mention of the strike in Kadalie’s autobiography and only a single reference to it in the memoirs of the ICU organiser, Jason Jingoes. The strike is also not mentioned in the unpublished account of the history of the ICU by another ICU officer, H.D. Tyamzashe.Footnote5 The ICU’s role in the strike has been underestimated in the existing literature.

This article adds to the literature on the strike and on the history of the ICU in two major ways. First, it uncovers new evidence of the ICU’s role that adds to our understanding of the nature of the strike and who its proponents were. It draws on interviews with workers and political activists who were present on the diggings before and during the strike, as well as archival and newspaper sources that shed fresh light on this event.Footnote6 This evidence details how ICU organisers had paid attention to workers and their plight before the strike and how, during it, the ICU acted as a trade union on behalf of workers for the furtherance of their aims in three important ways: it held meetings, picketed workers and participated in negotiating a final settlement.

Secondly, the article suggests that the causes of the strike were deeper than wage disputes and were rooted in broader grievances relating to the harsh living conditions and violent persecution of black workers, residents and the unemployed by the Lichtenburg authorities. The ICU’s activism prior to, during and after the strike highlights how the ICU regarded this constituency and their grievances as important: this can be seen in the speeches of ICU organisers, through their efforts to mobilise people to take part in the strike, and in their continued efforts to help workers as the diggings declined after the strike. Mobilising such oppressed and dispossessed constituencies became a hallmark of the ICU in the rest of the Western Transvaal.

Van Onselen has argued that the ICU’s organising on the Lichtenburg diamond diggings laid the foundation for it to spread into the rest of the Western Transvaal.Footnote7 Following the strike in Lichtenburg, the ICU blossomed in small towns throughout the Western Transvaal. The strike therefore played a major role in extending the ICU’s presence in the region into the 1930s, both through its legitimacy as a trade union and its amorphous character of representing dispossessed workers.

The Political Economy of Diamond Diggings in the Western Transvaal

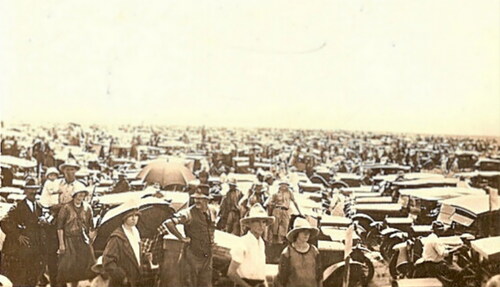

There are two regions in the Western Transvaal where diamond mining was most prevalent in the early 20th century: the Bloemhof–Schweizer-Reineke–Wolmaransstad triangle and Lichtenburg and its surrounds (see ). In the former, from as early as 1900, ‘the region enjoyed the effects of a relatively sustained but unevenly spread boom as thousands of white diggers and their black labourers invaded the district to work the local alluvial diamond deposits’.Footnote8 Further north in Lichtenburg, the discoveries of diamonds in early 1926 meant that ‘an average of some 60 to 75 per cent of farmers from the Western Transvaal districts of Lichtenburg, Ventersdorp, Zeerust, Wolmaransstad and Potchefstroom trekked to these diggings’.Footnote9 shows some of the over 10,000 prospectors who visited Lichtenburg; the initial discovery of diamonds was on the farm Elandsputte, but from 1925 a massive deposit was found in Grasfontein, with smaller ones found in Treasure Trove, Ruigtelaagte, Klipkuil, Vaalboschputte, Welverdiend and Witklip (see ).Footnote10

Figure 1. The alluvial diamond fields are divided into (1) the Mafikeng-Molopo or Northeastern field; (2) Lichtenburg-Bakerville or Northern field; (3) the Ventersdorp-Potchefstroom-Klerksdorp or Eastern field and (4) the Christiana–Schweizer-Reineke–Wolmaransstad–Bloemhof or Southern field (4). (Source: M. Wilson, G. Henry and T. Marshall, ‘A Review of the Alluvial Diamond Industry and the Gravels of the North West Province, South Africa’, South African Journal of Geology, 109, 3 [2006], p. 302.)

![Figure 1. The alluvial diamond fields are divided into (1) the Mafikeng-Molopo or Northeastern field; (2) Lichtenburg-Bakerville or Northern field; (3) the Ventersdorp-Potchefstroom-Klerksdorp or Eastern field and (4) the Christiana–Schweizer-Reineke–Wolmaransstad–Bloemhof or Southern field (4). (Source: M. Wilson, G. Henry and T. Marshall, ‘A Review of the Alluvial Diamond Industry and the Gravels of the North West Province, South Africa’, South African Journal of Geology, 109, 3 [2006], p. 302.)](/cms/asset/bc1cf640-85dc-41db-a8cf-cf29ebdc718e/cjss_a_2301894_f0001_b.jpg)

Figure 2. Thousands of motor cars at the proclamation of the Grasfontein diamond diggings, probably in 1925. (Source: J. Wood, ‘Motors at Proclamation of Grasfontein, Lichtenburg’, available at http://www.on-the-rand.co.uk/Diamond%20Grounds/Lichtenburg1.htm, retrieved 1 September 2020.)

Diamond digging constituted the second most prevalent economic activity after farming in the Western Transvaal, and many of the workers who were drawn to the diggings had ties to farms. Owing to the unreliable rainfall in the Western Transvaal generally, much of the region was suited to ‘mixed farming’ (in this case farming supplemented by an income from diamond digging).Footnote11 Mixed farming led to a large number of ‘farmer-diggers’, who used the diggings ‘during times of economic uncertainty … to recuperate losses suffered as a result of crop failure’.Footnote12 When a severe drought hit the Western Transvaal between 1926 and 1929, there was an associated rise in workers and prospectors looking towards the alluvial diamond diggings.

A ‘share’ system, similar to those on most farms, was adopted on the diggings: whites owned land and black labourers who worked on the land could share profits in a similar manner to that in crop cultivation. Robert Turrell has written about a share system on the Kimberley diamond mines which had become common practice by 1872 and which lay at the heart of the 1875 ‘black flag revolt’.Footnote13

The process of proletarianisation, which was based on the restructuring of labour relationships on farms, swept through the farming districts in the Western Transvaal between 1925 and 1930 and placed the economic livelihoods of black and white workers in a state of constant precarity. From the perspective of the government, given its anxiety over the ‘poor white problem’, the diggings were effectively a space where it could placate land-owning poor white farmers who had been hit by drought. Poor white and black workers flocked towards either farms or diggings, depending on the season, the climate and the availability of work. Clynick suggests that the economic function of the diamond diggings in the political economy of the Western Transvaal served as support for ‘marginalised rural communities or groups to resist “full proletarianisation” through their occupation of various peripheral niches in the rural economy’.Footnote14

The type of work undertaken at the diggings was stratified along the lines of race and class and the associated access to capital and land. Most white diggers sought out shallow gravel where they, or their black labourers, could ‘scratch around the surface’ with picks and shovels and use manual washing and sorting methods. Poor whites, ‘the victims of rapid economic growth’ elsewhere, made up the bulk of the farmer-diggers and workers who, having had other occupations, moved to Lichtenburg as ‘unprofessional diggers’ with little capital or expertise. Deeper gravel in Lichtenburg could only be accessed by well-resourced companies with adequate machinery.Footnote15 This meant that, while the Lichtenburg operations seemed minor when compared to those on the Rand or Kimberley, ‘landowners, syndicates and companies dominated the economic skyline in Lichtenburg’.Footnote16 An interlocking web of ‘international financial and mining interests controlled the exploitation of the Lichtenburg gravel-beds’.Footnote17 As argued by Clynick, what lay at the heart of the strike was conflict between an increasingly organised class of poor white diggers against powerful mining interests which were supported by the state.

The mineral revolution attracted people from all over the world in search of economic opportunity, and the presence of migrant workers on South African diamond mines was commonplace. Migrant workers from within South Africa’s borders who worked on the Western Transvaal diamond diggings included Basotho, Batswana (who travelled to the diggings from the districts of Mafeking and Vryburg), Xhosa and Zulu workers (the Natal ICU organiser, A.W.G. Champion, for example, worked on the Taung diamond diggings in 1917–1918).Footnote18

Migrant labourers from elsewhere in southern Africa also worked on the diggings, with a large proportion of them coming from Malawi (then called Nyasaland). Anusa Daimon notes that ‘Africans from Malawi were at the centre of this phenomenon [migration to South Africa], subverting an exploitative capitalist wage system for their own economic survival’.Footnote19 A criminal organisation called the ‘Bull Nines’, who ‘passed off bits of polished glass as uncut diamonds to gullible white farmers’ also operated on the diggings.Footnote20 The Bull Nines was an ‘ethnically diverse’ group of ‘small-time gangsters’ that was symbolic of the changing class, racial and ethnic character of the diggings.Footnote21

The white diggers and workers, meanwhile, were made up largely of farmer-diggers from the Western Transvaal, but also included a ‘cosmopolitan crowd’ of ‘Australians, Americans and Englishmen, people from all over the world’ who had come to the diamond diggings to get rich quickly.Footnote22

Economic Expansion and Depression in Lichtenburg, 1926–1928

Among the large and unregulated population that flocked to the Lichtenburg public diggings, there was prosperity to be found in a range of occupations: ‘the gamble of diamond digging provided quick and ready profits to the owners of the farms, the hotel and canteen keepers, the merchants and the diamond buyers’.Footnote23 Poorer white farmers who had lost their land because of drought, crop failure, debt and farm subdivisions made their way there; but the diggings also ‘attracted tens of thousands of blacks … and the magnitude of this response threatened to break down the existing structures of white domination, those being based on the premises of a cheap, ultra-exploitable and regulated black labour force’.Footnote24 For both black and white workers this was a departure from ordinary farm life and the diggings were, in the words of a government official speaking at the Carnegie Commission in 1931, characterised by a ‘lack of community feeling or recognised moral standards’ and an ‘all-pervading spirit of gambling, recklessness and instability’.Footnote25 Black and white workers, in the words of Solomon Buirski, digger and Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) activist, ‘live there rent free in a proclaimed area – every person, white or black can set up a house or khaya free’.Footnote26

The unregulated lifestyle that prevailed on the diggings was enjoyed mostly by men. The activities of women who had entered the diggings as domestic workers and to perform other miscellaneous jobs were more tightly controlled. Upon entering the diggings, women were made to produce a document on demand from the police called a ‘certificate of character’.Footnote27 This aimed to ensure that women had no prior criminal convictions, but it was also a mechanism to control their movement.

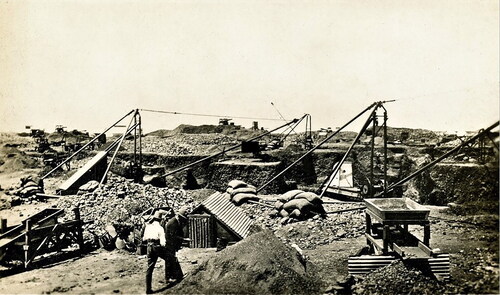

By 1926, the population of white diggers on the diggings was over 9,500, while black workers numbered over 28,000.Footnote28 White diggers hired black workers to do the manual labour; in each labour party there was a minimum of six and a maximum of 28 workers.Footnote29 shows black workers shovelling gravel through a sieve. When Sol Plaatje visited the diggings in May 1927, he described how black workers were housed: ‘in the native locations with which the diggings are intersected the shacks resemble the ant hills on a wide plain; and some of them not much bigger’.Footnote30 Plaatje wrote about whole black families who had moved to the diggings, each member being employed in a different occupation: ‘one native digging, his wife shovelling, his daughter carrying the gravel to the washing machine’.Footnote31

Figure 3. Black workers using a sieve on the Lichtenburg diggings. (Source: T.P. Clynick ‘“Digging a Way into the Working Class”: Unemployment and Consciousness Amongst the Afrikaner Poor on the Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggings, 1926–1929’, in R. Morrell (ed.), White but Poor: Essays on the History of Poor Whites in Southern Africa 1880–1940 [Pretoria, University of South Africa, 1992].)

![Figure 3. Black workers using a sieve on the Lichtenburg diggings. (Source: T.P. Clynick ‘“Digging a Way into the Working Class”: Unemployment and Consciousness Amongst the Afrikaner Poor on the Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggings, 1926–1929’, in R. Morrell (ed.), White but Poor: Essays on the History of Poor Whites in Southern Africa 1880–1940 [Pretoria, University of South Africa, 1992].)](/cms/asset/2a3951ea-6c07-46c7-a318-0ab9510d432e/cjss_a_2301894_f0003_b.jpg)

Poor living conditions were commonplace in the black locations surrounding Lichtenburg, which were characterised by ‘insanitary living conditions, lack of facilities for juvenile education, no social welfare services for the unemployed and irregular and intermittent economic opportunities’.Footnote32 A Rand Daily Mail article in March 1928 notes that there was considerable ‘misery’ on the diggings, with the influx of over 30,000 workers making the ‘distress on the fields … very great’.Footnote33

Crime and general anomie were features of the diggings, and a Workers’ Herald article in March 1927 provides three anecdotes on the ‘tit-for-tat’ between black and white workers. Criminal behaviour on the Lichtenburg diggings involved both black and white petty criminals robbing, intimidating and assaulting workers, often for large sums of money. The anecdotes of robbery and assault took on a racialised character, as those committing the crime often chose victims of a different race.Footnote34

The government’s attempt to regulate the diggings was piecemeal and it struggled to manage the mass of workers making their way to Lichtenburg. The Minister of Mines, Frederick Beyers, noted in March 1928 that ‘if people went [to the diggings] in thousands as they were, the government was not to blame’.Footnote35 The provision of police to the diggings was also desperately short. Owing to the need to ‘protect life and property in the remainder of the Union’, the diggings were staffed with 42 white and 20 black policemen for a population of over 35,000. By May 1928, the number of policemen was increased by four.Footnote36

The diamond diggings at Lichtenburg received attention from a variety of black political organisations; these included the Transvaal African Congress (TAC), the African National Congress (ANC) (as is evident in Sol Plaatje’s report) and, later, from the CPSA and ICU. During September and October 1927, Doyle Modiakgotla, who was the ICU’s Complaints and Research Secretary and conducted expert research on Western Transvaal towns, visited the Lichtenburg diggings and witnessed the dire conditions experienced by location residents.Footnote37

Modiakgotla chronicled the terrible conditions at the diggings in a letter to the ICU’s Head Office on 1 November 1927. He suggested that the ‘atrocities perpetuated on our people there are most disgraceful’ and went on to describe the grievances of workers and location residents.Footnote38 Among these was the complaint that people were hauled out of churches [by police] to demand pass and tax receipts and that those arrested for pass or tax offences were ‘bitterly assaulted and then marched down to the police station’.Footnote39 Modiakgotla also described the ways in which ordinary people were persecuted by the police, such as assaults on sick people, the destruction of personal property like suitcases and handbags and the discarding of illegally brewed beer on people’s blankets before marching them to the police station.Footnote40

The dire conditions and rough police treatment prevailing on the diggings revealed by Modiagotla’s report, as will be shown below, laid the groundwork for the ICU’s activism in the area.

Manipulation of the Market: Intervention by the State and De Beers

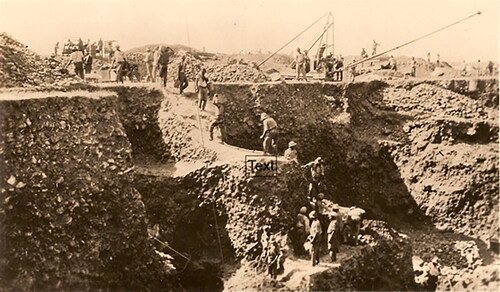

The fortunes of all workers in Lichtenburg, whether opportunistic diggers or the mass of white and black labourers, were bound to the variable nature of diamond production in South Africa. While large fortunes could be made on the Western Transvaal alluvial fields, there were great variations in alluvial diamond output (see ), as opposed to deep kimberlite diamond mining (which predominated in Kimberley, for example). and show the kinds of machinery used by workers on the alluvial diggings in Lichtenburg.

Figure 4. Deep diamond digging in Grasfontein, Lichtenburg. (Source: J. Wood, ‘Grasfontein Diamond Diggings, 1927’, available at http://www.on-the-rand.co.uk/Diamond%20Grounds/Lichtenburg13.htm, retrieved 12 September 2022.)

Figure 5. Mining gear at Welverdiend, Lichtenburg in 1926. (Source: J. Wood, ‘Deep Diggings, Grasfontein, Lichtenburg’, available at https://www.mindat.org/photo-862858.html, retrieved 12 September 2022.)

Table 1. Diamond production in alluvial diamond fields as opposed to kimberlite deposits, years 1925–1933

highlights that the communities of diggers and workers on the alluvial fields had almost managed to match the production of kimberlite diamonds across South Africa (see this in years 1927 and 1928), but were up against the world’s biggest diamond cartel: De Beers. Deborah Spar describes the control of De Beers over the diamond trade globally, the syndicate having managed to maintain the strength of the diamond price by ‘over a century of careful planning and negotiation’.Footnote41 The Diamond Syndicate, formed by Cecil John Rhodes in 1889, came to control the distribution of diamonds around the world, a mechanism which was further tightened under the leadership of Ernest Oppenheimer in 1925, in the guise of the new Central Selling Organisation.Footnote42

In Lichtenburg, such large volumes of diamonds moved, by farmer-diggers and workers, to the market in an unregulated way, ‘threatened the very existence of the Diamond Syndicate’.Footnote43 In the words of a leader in the Diamond Syndicate, the Lichtenberg discovery was a find which ‘might conceivably undermine the cornerstone of the diamond industry’; this was echoed by Ernest Oppenheimer who noted that ‘the syndicate are off their heads with worry about the find’.Footnote44 Because of this, and also as a result of new deposits being found in British Guiana and Namaqualand, Oppenheimer stipulated a standard not only for the size of the diamond, but also the quality.Footnote45 This led to a sizeable decrease in the average price per carat, from £4, to £3 and then £2 in September 1927.

The Precious Stones (Alluvial) Diamond Act of 1927 was adopted in response to this overproduction of diamonds. The Act placed ‘a ban on further prospecting in the Union as well as the non-proclamation of further farms for twelve months after the Act was passed’.Footnote46 In addition, the conditions under which men could own claims were tightened. Diamondiferous land was effectively ‘locked up’ to prevent overproduction in the interests of holdings owned by large mining groups. Big capitalists and landowners therefore took ground at the expense of independent capitalist diggers and small diggers, which created widespread unemployment.Footnote47 The Act had in fact been crafted through a pact between two turncoat local diggers, A. Ireton and W. Thom, and diamond mining magnates Ernest Oppenheimer and Solly Joel; it purported to safeguard the interests of the ‘small man’ by eliminating local capitalist diggers but in fact, particularly through petitioning for the provisions of the Act, served the interests of large companies (like those of Oppenheimer and Joel) who were facing competition from these capitalists.Footnote48

The instability of the diggings in Lichtenburg, resulting from real or threatened closures, created unemployment and increasing competition over jobs. From late 1927, black workers started experiencing reductions in wages and growing unemployment. Buirski notes that ‘as the ground got poorer, the diggings got poorer and the wages of African workers went down with a bump!’Footnote49 When Modiakgotla visited Grasfontein in October 1927, he noted that ‘the police refuse to prosecute employers who withhold wages of the employees on the grounds that the employers cannot help if they have not found good stones’.Footnote50 African people staying in locations around Elandsputte were constantly harassed for pass law contraventions and other misdemeanours. A white resident in Lichtenburg wrote to the Minister of Justice on 9 May 1928 about the situation prevalent in the locations, claiming that many black people ‘are lying in the diggings and are not in service’, and thus were ‘committing theft and burglary, and other crimes’.Footnote51 He asked of the Minister of Justice whether it was possible to ‘remove the black people in the locations who are not working’, a segregationist attitude according to which Africans were ‘temporary sojourners’ in urban areas.Footnote52

The police at Elandsputte were swift in dealing with workers who had recently become unemployed as a result of the overproduction of diamonds, increased state control over mining and claims drying up on the diggings. On 29 May 1928, the police inspector at Elandsputte noted that ‘250 natives are in custody because of contraventions of the Pass Laws. The contraveners are charged a pound fine or a short jail term’.Footnote53 The inspector also suggested that the locations are ‘attractive for black people as they finish their contract’.Footnote54 The police were tasked with patrolling locations twice per week (sometimes at night in adjacent locations) and often arrested people for pass offences and crimes relating to burglary.

In August 1927, it was noted by the South African Police (SAP) at Elandsputte that Malawian workers were engaged in ‘faction fights’ with Basotho and Xhosa workers. In order to stop the fighting, which had resulted in several deaths, the SAP at Elandsputte had the Malawian workers moved to a police camp.Footnote55 In December 1927 a flurry of fights between groups of Malawian workers and groups of Basotho and Batswana workers erupted around Christmas Day in Lichtenburg (as well as in Johannesburg’s Western Native Township). The aggressors alleged that the Malawian workers were courting Basotho women, but it is more likely that the skirmishes had to do with competition over increasingly scarce jobs. Many of the altercations between Basotho, Batswana, Xhosa workers and the Malawian workers were violent and resulted in injuries and death.Footnote56

With the influx of workers from across southern Africa, and with ethnic tensions flaring up in different parts of the Transvaal, the TAC took up an anti-immigrant position. On 1 February 1928, the TAC sent a petition to the Minister of Native Affairs requesting the repatriation of ‘Blantyre Natives’.Footnote57 Prominent leaders of the TAC, including Edward Khaile (who was an ex-ICU member, and at the time was the general secretary of the ANC), claimed that ‘Central African Natives [that is, from colonial Malawi] molest Union Natives in various ways’ and that there was ill-feeling growing on the diggings because of the ‘replacement of Union Natives by Blantyres’.Footnote58

A black attorney, Richard Msimang, suggested that the petition was fraught with contradiction and provocation. He argued that the petition ‘support[ed] a drastic policy of deportation’.Footnote59 The TAC’s appeal added fuel to the ongoing bid to banish migrant workers from outside South Africa’s borders, including Clements Kadalie, who was born in Nyasaland (present-day Malawi). Politicians had tried to deport Kadalie since 1920, and in 1926 the then Minister of Justice, Tielman Roos, told parliament that Kadalie should be deported to Nyasaland.Footnote60

In addition to the decreased price of diamonds and the control over production, by late 1927 and into 1928, claims in Elandsputte and Welverdiend became less profitable and diggers turned from the public diggings to the more prosperous gravel controlled by landowners and big capitalists. The exclusion of poorer diggers from the best land by large landowners created a ‘groundswell’ effect, in which white diggers began to organise themselves to preserve the ‘public’s [land] rights’.Footnote61 In describing the growth of the Diggers Union (DU) of South Africa in 1927, a body of white diggers who opposed the strangling of their production, Clynick notes that ‘[a]t its base lay this residue of impoverished and marginalised producers, which grew extremely impatient with the failure of the government to cater for their narrow, particular interests’.Footnote62

The ‘small’ workers on the diggings, whether claimholders or ordinary labourers, were being squeezed increasingly by the state and large capital. The DU and white diggers had a radical political influence on the diggings. This came principally from Solomon Buirski who had started a CPSA branch in Lichtenburg. Buirski had ‘taught [CPSA] study groups for the transient white population on the diamond fields’, and also had a relationship with the ICU.Footnote63

The formation of the DU was important for claimholders who were being forced into wage work and for the newly unemployed. It took up the cases of the ‘small diggers’ as well as wage workers who had recently become unemployed after large companies shut down.Footnote64 The digging community in Lichtenburg and the DU, finding themselves threatened by the limits placed on prospecting, throughout the early months of 1928 led a few unsuccessful deputations to relieve their grievances.Footnote65 These included meeting with ministers and holding conferences with landowners to free up land for ‘small’ prospectors.Footnote66

On 15 June 1928, white diggers responded to the manipulations of the diamond market by the state and De Beers and reduced black workers’ wages from 20 shillings per week to 12 shillings. Clynick suggests, convincingly, that white diggers transcended a purely rural identity and developed a strong degree of ‘group consciousness’, stating that:

the Lichtenburg diggers in the period 1926–29 exhibited a remarkable degree of resilience to the efforts by the State and Capital (represented by the large diamond producers in the Union) to eliminate the small man on the diggings through legislative and economic pressure.Footnote67

Pittance and Police Persecution: The ICU and the Lichtenburg Strike

As shown above, the ANC, TAC, ICU and CPSA all had a presence in Lichtenburg. While the CPSA held study groups among white diggers, the ANC, TAC and ICU had undertaken research visits and chronicled the dire and conflictual conditions among black workers at the Lichtenburg diggings. The DU engaged in political activism on behalf of white workers, and it was the ICU that engaged in political activism for an extended period among black workers on the Lichtenburg diamond diggings.

On 22 April 1928, ICU organiser Alexander Maduna gave a speech at the Elandsputte diggings. He was well known for his oratory and fiery speeches, and was particularly encouraging of strike action. In this speech, he drove at the heart of the problems on the diggings, which Modiakgotla had also highlighted six months prior. A police report relays some of what Maduna said:

[Maduna] spoke about the treatment the coloured workers on the diggings were receiving from their European employers. He stated that the natives were working like slaves, while the Europeans were looking on with their hands in their pockets[;] when at the end of the week their employers failed to pay them and the natives reported the matter to the police, the police invariably failed to take action against the Europeans. He urged the natives to demand that the proceeds of the diamonds be equally divided between the employers and employees. He stated that the natives were being exploited by foreign adventurers, and urged them to fight as there could be no peace between the robbers and the robbed.Footnote68

he further stated that if what he heard of the police raids were true, the present state of affairs were disgraceful, and that they [ICU members/workers/residents of locations] did not want the police there at all. On beer raids, the police first drank their gill of beer and then threw the beer over the beds and furniture … He urged natives to protest being dragged out of their bed at night on account of the pass law. The natives should not look to government for protection, as the government had failed to protect them.Footnote71

A week later, on 29 April 1928, three speakers addressed a crowd of 50 workers under the auspices of the ICU. The speakers were ICU organisers Augustus Jonathan Stephens and Albert Jonga, and H. Ghobos, who according to a police report was ‘a local native labourer and cannot be classed as an agent of the I.C.U’. Stephens opened the meeting by telling workers to carry their pass and tax receipts, as well as saying that women brew beer because their husbands were not paid properly on the diggings. Jonga and Ghobos both referred to ‘the non-payment of native labourers by their masters, and expressed the wish that the Government would take steps against the delinquents’.Footnote72

At a meeting in Potchefstroom on 24 June 1928, Keable ‘Mote spoke about a meeting at Grasfontein earlier that month.

On the 9th [of June] I opened one of the biggest agitations at Grasfontein. I found the workers treated worse than slaves. I did not go to create hostility between white and black. I went to tell the thieves and robbers that my people must leave. The people are treated and sjambokked like dogs. I told the Magistrate of Lichtenburg. I told the Commandant of Police of Potchefstroom to stop [the] sjambokking of natives or I will give him a damn good lesson. If a policeman comes at 5 a.m. and pulls me out from my sweetheart, I would fight – would you not fight? [Cries ‘Yes!’ and ‘I’ll Fight’].Footnote73

As explained above, the pressures placed on black and white workers came to a head on 15 June 1928. On 18 June some 5000 black workers embarked on a strike on the ‘poorer sections of the diggings’ and by 20 June, between 35,000 and (as reported by some members of the police force) 80,000 workers ‘struck work, picketed and pulled strike-breakers out of their claims’.Footnote74 By Wednesday, all work on the diggings was at a standstill.Footnote75 The central question that arises is: what led black workers to strike en masse and in a co-ordinated way? The account which follows attempts to provide a partial answer to this question, arguing that the ICU’s role was critical.

When white diggers cut black workers’ wages on Friday 15 June 1928, they gave no notice to black workers.Footnote76 It appears that workers found out about the reduction when they went to collect their weekly wages on Saturday, and on Monday 18 June they embarked on a strike instead of returning to work. Both Piet Baraganyi, an ordinary labourer at Grasfontein, and Ishmael Moeng, a mechanic at Elandsputte, were working on the diggings at the time and witnessed the events of the forthcoming week, which they remembered when they were interviewed many years later.

On Monday 18 June 1928, Baraganyi was working on a claim in Grasfontein (see ), when he saw Kadalie and ‘Mote with his ‘own eyes’, organising workers and demanding that ‘Tswanas must be paid reasonable wages’. Baraganyi remembered: ‘it was a Monday [18 June 1928] and we were at work, I just saw a group of people coming, they hoisted a red flag’.Footnote77 As the procession of people approached him, they began ‘thrashing’ him and other workers with switches (a kind of whip) and told them to leave their jobs.

Figure 6. Map of farms in Lichtenburg where diamond digging was prevalent. Grasfontein is at the centre of the image. Elandsputte is not on this map, but sits just north-east of Grasfontein. (Source: M. Wilson, G. Henry and T. Marshall, ‘A Review of the Alluvial Diamond Industry and the Gravels of the North West Province, South Africa’, South African Journal of Geology, 109, 3 [2006], p. 308.)

![Figure 6. Map of farms in Lichtenburg where diamond digging was prevalent. Grasfontein is at the centre of the image. Elandsputte is not on this map, but sits just north-east of Grasfontein. (Source: M. Wilson, G. Henry and T. Marshall, ‘A Review of the Alluvial Diamond Industry and the Gravels of the North West Province, South Africa’, South African Journal of Geology, 109, 3 [2006], p. 308.)](/cms/asset/c221c412-8e11-4373-914a-7a5d46c36c59/cjss_a_2301894_f0006_b.jpg)

Baraganyi believed that this was a ‘a sign of contempt and disrespect for the Boers’ and did not want to leave his job, viewing the recommendation to strike as ‘hasty’.Footnote78 The workers were then ‘told’ to follow Kadalie to a meeting and that they were ‘stupid for [they] worked for nothing for whites’.Footnote79 Kas Maine’s account of how the strike began at Lichtenburg echoes Baraganyi’s:

They would stop you from working. They get hold of you, there at the claim, they tell you you must get out, you must not work, because the man does not want to pay. That was the time of the ICU.Footnote80

the natives who were out of work loafing in the locations … were causing all the trouble, the I.C. Union being the instigators of the strike and not the boys on the claim … [W]hen the natives’ wages were reduced, they were willing to work, and it was only late this morning when the natives who were at the bottom of the trouble came to the claims and chased the boys who were working off.Footnote81

Thus, according to the DU, black workers went on strike because of intimidation ‘on account of the rise of the natives’ who took ‘pick handles’ and chased workers on the claims ‘until they all stopped working and joined the band of strikers’.Footnote82 Swanepoel, the secretary for the Diggers and Farmers Committee and the president of the DU, reiterated at a meeting held on Wednesday 20 June that the ‘instigators’ of the strike ‘were not the old diggers’ boys … but the loafers in the locations’ and that the ‘the agitators chased them and forced them to follow them. These loafers are parasites on the boys who attend work regularly’.Footnote83 A digger from Grasfontein, Jooste, noted that Grasfontein ‘[had] the largest locations’ and recounted that the ‘I.C. Union together with the loafers in the locations stirred up the bad feelings’.Footnote84

After the meeting held by Kadalie on Monday afternoon, workers were told to return to another meeting on the following day, Tuesday 19 June, at which they were addressed by Kadalie again,

we then returned the following day, Ooh! We were many. He told us that he was Kadalie and he would like to help us and was not afraid to come face to face with the white man. And during those times, while we were in Motati [the ‘ancient name of the area in the Lichtenburg district’], we were earning low wages. Some people were paid a pound a week, some nineteen shillings or eighteen shillings.Footnote85

After the meeting was concluded, the workers were advised by ICU organisers to ‘disperse to [their] respective jobs and start working’ and that they must be paid one pound and five shillings.Footnote86 This is confirmed by a Rand Daily Mail article on the same day which noted that an unnamed ICU official, when approached by workers, advised that they ‘proceed along constitutional lines’ and should resume work ‘pending a conference to settle the dispute’. Bradford notes that suggestions of ‘peaceful action’ were met with ‘sullen statements that twelve shillings was not a living wage’.Footnote87

Swanepoel affirmed that ‘meetings have been held and Kadalie has the power over the natives – they are ignorant of conditions and believe everything that is told to them’.Footnote88 Similarly, De Vos, a digger from Grasfontein, noted that the strike was convened by the ‘I.C. Union and its followers’ and that ‘Kadalie’s representative, ‘Mote had been on the diggings and started this trouble’.Footnote89

Solomon Buirski recalled that he and fellow CPSA member William Andrews had tried to ‘get in with the strikers’. Not knowing whether the striking workers had heard about the expulsion of communists from the ICU in 1926, they persisted but eventually ‘found an impenetrable wall’. He suggests, ‘I was a communist … I was a European and could not be trusted’.Footnote90 Buirski saw that the strike reached all the farms, but not all the workers and notes that it was principally led by the ICU’s Bloemfontein office (most likely led by ‘Mote).

Ishmael Moeng was working as a mechanic in Elandsputte and Vaalboschputte (see ) when he heard of the ‘big strike’. According to Moeng, on Monday 18 June 1928, Jingoes had arrived at the diggings as a ‘representative of the ICU’ and was actively involved in organising the strike: ‘if he found people working, he would order them to stop as a strategy for an increase in the wages’.Footnote91 He also addressed workers in a meeting which Moeng also attended:

when we arrived we found a lot of people and he [Jingoes] was saying that people should be paid reasonable wages and that special passes should be abolished. Those who don’t want to pay reasonable wages should leave the employer. But he didn’t suggest what should be done if one left his employer, you see.Footnote92

The same situation prevailed at Elandsputte and Vaalboschputte, where ‘they [the strikers] broke and looted shops so that they could get food to eat’.Footnote96 Moeng suggested that many of the workers then turned to Jingoes for food, because he was the one ‘who encouraged them to stop working’, but he was ‘unable to give them food’.Footnote97

By Wednesday 20 June 1928, the situation had reached a climax. Catching the wave of protest for increased wages, almost all the workers joined the strikers and ‘all labour had been suspended and an estimated 35,000 [black workers] were on strike’.Footnote98 A Rand Daily Mail article captured the tense atmosphere thus: ‘headgears and washing gears stand stark against the sky like the litter of war abandoned by a retreating army … Diggers and natives alike are wandering aimlessly, and gathering for meetings that grow more impatient as no settlement is reached’.Footnote99

On Wednesday 20 June, negotiations took place. At a large meeting that included a collection of diggers, the Lichtenburg Magistrate and the Mining Commissioner of the Western Transvaal, the Director of Native Labour, Major Cooke, suggested that workers be paid 15 or 16 shillings a week which would continue until the beginning of July after which workers would make ‘individual work arrangements with their master’.Footnote100 Cooke decried the actions of the diggers, and questioned whether they can ‘reasonably expect a native to accept work at 12/- per week without rations, quarters or medical attention’.Footnote101 While some ICU organisers had been on the diggings during the first two days of the strike, Bradford suggests that further officials from the ICU’s national leadership appeared on the diggings on the Wednesday for the wage negotiations. She suggests that it was minor activists and the black rank-and-file ‘who were forcing senior officials to bend to their will’, and that the leadership, who had initially been apprehensive to support the strike, ‘had totally shifted their position … [H]ead office, they now declared, had decided to support the strike, and four organisers would come to the diggings that very night [Wednesday 20 June 1928]’.Footnote102

Wickins quotes ‘Kadalie’s actual statement’, published in The Star:

four officials of the Union will set out for the diggings to-night. Their object is to induce the strikers to accept 15s. as a basis for further negotiation, and it is also the intention of the Union to approach the Wage Board to investigate conditions on the diggings. It is the contention of I.C.U. officials that the diggers broke the natives’ contracts.Footnote103

Police reports regarding the whereabouts of ICU organisers during the negotiations were contradictory. Sergeant Mickdal had observed that both Kadalie and ‘Mote had left the district for Potchefstroom by 20 June; whereas on 21 June, the Mafikeng SAP reported that ‘diligent enquiries’ were made to find the whereabouts of Kadalie, but noted that after giving a speech in Mafikeng, they could not ascertain whether he left for Grasfontein or Johannesburg.Footnote107

White diggers, however, still threatened violence against Kadalie and ‘Mote if they were to return to the diggings. One digger, Ruitgelaagte, promised to retaliate if the ICU continued to force labourers to stop working: ‘if the natives come back to work and are molested [by the ICU], we will take up the cudgels on their behalf’.Footnote108Another, one Malan, made the most violent threats: ‘if he knew or saw where ‘Mote was hiding, he would kill him and so would any of the diggers’, who would give both Kadalie and ‘Mote ‘a free grave on the diggings’.Footnote109 Despite the aggressive language, Buirski asserts that the attitude of the diggers to the striking workers was ‘inimical but not violent’.Footnote110

By Thursday 21 June, police protection had arrived. The Magistrate at Lichtenburg noted in a letter to the Secretary of Mines and Industries on Thursday 21 June 1928 that the police must ‘protect the black workers who want to work’.Footnote111 Moeng remembered the arrival of ‘soldiers’, some ‘by aeroplane and some by horses’.Footnote112 He also remembered that the ‘Boers called the soldiers and told them that people don’t want to work’. In ‘Mote’s account ‘there were lots of police, but nobody was hurt; the whole force was there’.Footnote113 The soldiers and policemen then went ‘in[to] the locations and announced that those people who don’t work must go back to work. Those people who don’t want to work must not raise their hands and those who will must raise theirs’.Footnote114

This strategy aimed to divide workers into ‘claim workers’ and outside ‘agitators’ and to further isolate the ICU as an external force driving the strike. This kind of thinking translated into the actions of ordinary diggers towards workers; over the course of the week, a case was reported where the police found a black worker who was severely beaten ‘tied by the feet with his hands tied behind him bleeding profusely from the nose and mouth’, because he had been working on a claim where the digger had ‘not recognised him personally’.Footnote115

The division drawn mainly by the diggers between ‘loafers’ or ‘agitators’, on the one hand, and ‘old boys’ (claim workers) on the other, does not account for the extent of the strike.Footnote116 If anything, it was a ploy to divide the workers and stifle the strike. There was considerable fluidity on the diggings, as the ‘old boys’, ‘agitators’ (ICU organisers or activists) and ‘loafers’ (unemployed location residents) all lived in the locations surrounding the diggings.

There is evidence to suggest that the wage cut was a ‘spark’ which ignited existing grievances experienced by location residents. At an ICU meeting in July 1928 its Lichtenburg branch secretary ‘injected a broader political note into the review of the strike’ suggesting that it was not only the ‘fall in wages’ but also the ‘brutality of the state’ that had ‘betrayed workers’ interests’.Footnote117 He called: ‘away with this government, away with this obnoxious pass system and let us obtain freedom’.Footnote118 Bradford argues that ‘the prominence police raids often had in the union speeches on the fields lends substance to the [diggers’] allegations that the ICU’s support was primarily drawn from these loafers’. Indeed, she notes that this constituency had a ‘strong, if indirect interest in the stoppage’.Footnote119

Similarly, ICU organiser Doyle Modiakgotla viewed the abolition of pass laws as one of the workers’ demands during the strike; at the National European–Bantu conference in February 1929, he ‘denied that the pass system was any protection to property or contract and stated that in the Grasfontein strike the Native Affairs Department did nothing to assist the Natives’.Footnote120 This is akin to an ICU protest in Waaihoek, Bloemfontein, where what had started as beer protest transformed into a generalised strike against low wages, underemployment and persecution from police.Footnote121

By Friday 22 June, it was reported by the South African Worker (the CPSA newspaper) that the ‘main body of strikers are still standing fast and at the time of writing there is no indication that they are prepared to concede their demands and accept the reduction in wages’.Footnote122 The ICU, albeit minor activists, remained on the fields; one organiser declared that despite orders to leave, the ‘ICU would nevertheless remain’.Footnote123 This was a brave pronouncement, considering van Onselen’s suggestion that the wage negotiations had placed the ICU in a difficult bargaining position where they were ‘trapped between the workers’ anger and the diggers’ militancy’.Footnote124 Strike action by black workers continued throughout the week, and as a result Bradford notes that ‘by Friday, most [white diggers] were prepared to pay fifteen shillings a week; [and that] by Monday, life was back to normal on the fields’.Footnote125

When Baraganyi went to collect his wages on Saturday 23 June, he did not get paid and found out then that his wages had been lowered. Similar to Baraganyi, when other workers went to collect their wages, they were told that ‘since the ICU had promised to give us five pounds a week, we would get it from [the ICU] and not from them [the diggers]’.Footnote126 He regarded Kadalie and ‘Mote as responsible for the reduction of workers’ wages ‘because there was no single white man at the meeting [held by the ICU], whom we could point to and say he had agreed’ on the increase.Footnote127 Baraganyi’s reflections suggest that the ICU’s influence in mobilising workers was limited – in that workers misunderstood the position of ICU organisers and even mistrusted their intentions. In this regard, Moeng remembered that after the strike rumours ‘flew around’ that Jingoes had ‘built a hotel in Johannesburg’ and had come to work with people in South Africa ‘mainly to swindle their money’.Footnote128

On 26 June 1928, a government official suggested that diggers in the meeting of Wednesday 20 June 1928 ‘seem to have considered that the I.C.U. were more responsible for the [strike] position than [suggested by] the newspaper reports[,] which … indicated feeling against Kadalie and Mote was apparently very little’.Footnote129

While the diggers foregrounded the role of the ICU in the strike, this is in dispute. Van Onselen, for example, asserts that ‘the I.C.U. had probably played a far less important role in the strike than that attributed to it by deeply resentful white employers’.Footnote130 It is undisputable that the largest constituency of the strike was made up of ordinary black workers who had little or no affiliation to the ICU.Footnote131 Bradford summarises that while the stoppage was known as the ‘Kadalie Strike and many participants may have had great faith in him’, it was the rank and file which were forcing the ICU to bend to their will.Footnote132

Reviewing the strike, the South African Worker suggested that it was a ‘partial victory’, as well as ‘splendid united action’ and an ‘example to the toiling masses of Africa’.Footnote133 Bradford also regards the strike as an ‘astounding’ achievement where ‘ordinary [black workers], with the help of lesser ICU activists brought the diggings to a halt and even spread the stoppage to farmworkers on an adjacent holding’.Footnote134

The ICU in the Aftermath of the Lichtenburg Strike: Internal Splits, Liberal Intervention and Declining Prosperity on the Diggings

In the days following the strike, ICU organisers reflected on their activities. ‘Mote delivered a speech in Potchefstroom on 25 June 1928, in which he claimed a victory for the workers at Grasfontein, saying ‘you can arrest Keable Mote but the ICU will remain. At Grasfontein I addressed a meeting of 25,000 – even the magistrate had to beg me … we don’t believe in fighting with sticks and stones, we believe in the court and law’.Footnote135 In September 1928, at a meeting held in Makwassie, Robert Makhatini suggested that ‘we will not hear of strikes because this is not Lichtenburg, wherever the ICU is, there are no strikes’.Footnote136 These contradictory statements reflected the chequered perspectives on strikes within the ICU. From its inception, when it was founded because of a strike on the Cape Town docks in 1919, it was strongly influenced by British working-class militancy and some of its members continued to regard strikes as a legitimate weapon. During his speech in Lichtenburg, Maduna urged workers to ‘do what the white workers of Britain did, and dictate what they want’.Footnote137 Yet, during the second half of the 1920s, they began to be factionally divided between moderates, who called for ‘constitutional methods’ and the ‘ginger faction’, who advocated for ‘direct action’ (‘Mote was part of the latter group).Footnote138 Fascinatingly, ‘Mote embodied both sentiments in his review of the strike.

During June and July 1928, the situation at the diamond diggings got progressively worse as diggers and workers alike were squeezed by the drop in diamond prices. Many diggers could not pay wages, and punishments were proposed, including a fine and the revoking of diggers’ licences (the ICU branch secretary at Lichtenburg campaigned for the latter).Footnote139 By September, tensions continued to grow on the diggings as black workers accused white employers of not giving ‘discharged passes on termination’ and of not paying the required wages. In turn, white diggers complained about the desertion by black workers.Footnote140 The internal disintegration of the ICU, both nationally and in Lichtenburg, precluded the ICU’s ability to exploit and capitalise on this situation. Buirski regarded the strike as ineffective, partly because of the economy surrounding diamond digging: ‘[i]n a strike in a factory – one loses money, or rent – but on the diggings, he [the digger] doesn’t lose. One – diamonds don’t run away, two there were no expenses there’.Footnote141

On 28 October 1928, Kadalie returned to Lichtenburg and gave a fiery speech in which he railed against the ‘doctrine of a white South Africa’ espoused by the then Minister of Justice Tielman Roos.Footnote142 Speaking about the situation in Lichtenburg, he noted that ‘only that afternoon men had been arrested for not carrying passes. The pass system – this despicable pass system – was slavery, and they were determined to remove it’.Footnote143 Omitted from the speech however was the dire situation on the diggings relating to the non-payment of wages.Footnote144

The Lichtenburg strike occurred just prior to the arrival of the Scottish trade unionist William Ballinger in South Africa on 18 July 1928. Together with other white liberals,Footnote145 Ballinger began wielding increasing influence over the policies and character of the ICU; it was his arrival that contributed to Kadalie’s resignation in January 1929 which broke up the ICU into a number of splinter movements, with Kadalie’s being called the Independent ICU.Footnote146 There is evidence to suggest that this affected the ICU at a local level in Lichtenburg; it was split between the ICU aligned to Ballinger and the Independent ICU aligned to Kadalie.

On 30 June 1929, the ICU, under a new banner of the ‘I.C.U. Independent Movement Lichtenburg Fields’ (a splinter group which was most likely modelled on Kadalie’s Independent ICU), decried the dire conditions on the diggings. A petition was signed by 43 workers on the diggings which argued that white diggers were withholding wages, that the police were ignoring workers’ complaints of non-payment of wages and that the police continuously harassed workers for poll tax monies.Footnote147 The Secretary of Native Affairs assured the complainants that, despite tough economic conditions, ‘everything possible is being done’ to help the workers, and the Commissioner of Police at Lichtenburg defended the actions of the police and said that the ‘arrest of pass-less African workers on the diggings is justifiable’.Footnote148

A different faction of the ICU, this time siding with Ballinger, also engaged with workers under the banner of the original ICU. The revenue received by this faction in Lichtenburg in November 1928 amounted to £1.18, which meant approximately 25 members.Footnote149 A meeting of workers was held by the ICU branch secretary, Ndadso, on 13 October 1929. A Native Affairs Official in Elandsputte who kept track of the ICU in Lichtenburg noted that Ndadso was under the ‘control of Mr. Ballinger’, and the discussion at the meeting was rather tepid and concerned the pass laws. The meeting was also reported to be very ‘orderly’.Footnote150 In another letter the official commented that ‘there has been very little activity by the I.C.U. on the diggings here since the last strike’.Footnote151 This was confirmed by the Commandant of Police, who suggested that there was ‘nothing of consequence to report on’.Footnote152 While this was indeed the case, the local authorities still asked the Director of Native Labour, Major Cooke, for the ICU meetings to be banned.Footnote153 Major Cooke argued that increased repression could lead to antagonism and resistance and that ‘[t]he Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union, as at present constituted under Mr. Ballinger, usually confines its discussions to matters affecting conditions of employment’. He suggested that there were no grounds to bar the meetings.Footnote154

Compounding the divisions within the ICU were reports of corruption and mismanagement. Henry Dee notes that ‘as corruption within the ICU became publicly known, crushing disillusionment rapidly spread amongst members’.Footnote155 In a letter to the Workers’ Herald in December 1928, the ICU branch secretary for Lichtenburg mused over the state of the branch saying that ‘[ICU members] have suffered so much under the yoke of hypocrisy, so much so that they do not even know what can heal them’. He referred to the issue of the payment of workers at the diggings, noting that they ‘are being exploited’ and further noted that money that had been sent to the ICU’s head office in Johannesburg was not being used to improve branches and pay local officials; it was being misappropriated instead. In this letter, the branch secretary argued that the continued life of the ICU was at risk.Footnote156

By the early the 1930s, work on the alluvial diggings was grinding to a halt, reaching a production of 647,100 carats in 1931 and 488,100 in 1932. The economic situation was poor; by 1931 white diggers were getting economic relief from the government and black workers were putting pressure on the government to provide them with food rations.Footnote157

Conclusion

This article has argued that from mid 1927, the ICU began to pay attention to black workers on the diggings in Lichtenburg. ICU official Doyle Modiakgotla conducted a research visit in Lichtenburg in late 1927 and Alexander Maduna, along with local ICU activists, addressed workers on the diggings in terms which spoke to the heart of the problems in the town. When black workers’ wages were cut from 20 shillings to 12 shillings in June 1928, Keable ‘Mote and Clements Kadalie as well as other local ICU activists made up the vanguard of the ICU which organised workers. They did so in three different ways, acting as a trade union: first, by picketing workers and mobilising them to strike; secondly, by holding meetings with workers to discuss their demands and thirdly by negotiating with white diggers and state officials to secure a less dramatic wage drop than initially threatened. The union thus played an important role in initiating the strike and negotiating its final settlement, which was that a wage of between 15 and 16 shillings would be paid until the beginning of July (in other words for just one week) after which workers would make individual agreements with their employers. This was a partial and short-lived victory against both the diggers and the manipulations of the monopolised diamond market. The new evidence provided showcases the success of the ICU through keeping abreast with the contexts and grievances of local workers.

The strike also highlighted the fraught conditions on the diggings. Evidence of this includes the violence and persecution by the police, the rejection of pass laws by ordinary workers and the ICU, growing unemployment and the participation of unemployed workers during the strike. ICU officials referenced these conditions in their speeches both before, during and after the strike. The ICU’s focus on living conditions in Lichtenburg’s locations and on workers who were unemployed and dispossessed showed its capacity to appeal to, and represent, a broader constituency than wage workers. This capacity was reflected in their activism with location residents and labour tenants in the years that followed in small Western Transvaal towns.Footnote158

While highlighting the ICU’s successes, this article does not assert that the ICU’s participation in the strike was omnipotent or without contradiction. The ICU did not garner the support of all workers and it is likely that the strike was equally led by ordinary workers. Furthermore, the ICU did not manage to create a lasting consciousness among workers, nor a large, loyal constituency. The measure of ICU influence is summed up beautifully by Baraganyi: ‘people joined the ICU thereafter [after the strike], but the majority did not’.Footnote159 The ICU’s activism on the diggings, both during the strike and after, shows the tensions within the organisation relating to the arrival of William Ballinger, Kadalie’s resignation and the ICU’s internal divisions, which became increasingly pronounced by the late 1920s. Public pronouncements about the strike in the weeks that followed it from the national leadership, local organisers and supporters of the ICU were contradictory and revealed their ambivalence towards strikes. Yet this ambivalence should not be a reason to omit the strike from the history of the ICU, nor to deny the Union’s agency in it. This strike should stand as a significant achievement late in the life of the ICU and an example of its radical influence. It was as influential here as it was in the strike in Cape Town in 1919, at which the ICU was formed, and as powerful as the strike in Bloemfontein in 1925.

The aftermath of the 1928 strike saw an increased interest in the ICU as an organisation. Van Onselen argues that ‘given the scale of the exodus from rural areas to the diggings, the ties of kinship and ethnicity among black workers and the close link between seasonal agricultural labourers and employment on the diggings’, it was unsurprising that the news of the ICU was swiftly transmitted to farming districts across the Western Transvaal.Footnote160 He continues, ‘the strike at Grasfontein alerted the ICU leaders to the existence of these conduits into the countryside’.Footnote161 While the ICU continued to fight battles in Lichtenburg relating to poor wages as well as to the persecution of workers by police, declining prosperity on the diggings as well as the ICU’s own organisational issues meant that by the early 1930s the ICU had no influence on the diggings.

Researcher, History Workshop, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, Johannesburg, 2050, South Africa. Email: [email protected]

http://orcid.org/0009-0005-9698-3105

Acknowledgements

I thank Arianna Lissoni and Henry Dee for their time and energy in giving critical and engaged feedback. Also, I thank the History Workshop for funding for the Master’s programme which produced my thesis and subsequently this article. The Wits Historical Papers Research Archive and the South African National Archives were extremely helpful in in providing documents. Finally, I would like to thank my friends, my darling and my family for their support during the research process.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished online with one minor update. This update does not affect the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laurence Stewart

Laurence Stewart Researcher, History Workshop, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, Johannesburg, 2050. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 T.P. Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers 1926–1929’ (unpublished paper, University of the Witwatersrand, 21 May 1984), p. 13, available online at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/39667453.pdf, retrieved 11 December 2023.

2 H.J. Simons and R.E. Simons, Class and Colour in South Africa, 1850–1950 (London, IDAF, 1983 [1st edition, 1969]), p. 362.

3 C. van Onselen, The Seed is Mine: The Life of Kas Maine, a South African Sharecropper, 1894–1985 (New York, Hill and Wang, 1996), p. 146.

4 H. Bradford, A Taste of Freedom: The ICU in Rural South Africa, 1924–1930 (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1987), p. 166.

5 C. Kadalie, My Life and the ICU: The Autobiography of a Black Trade Unionist, S. Trapido (ed.) (London, Frank Cass, 1970); S.J. Jingoes, A Chief is a Chief by the People: The Autobiography of Stimela Jason Jingoes J. and C. Perry (eds) (London, Oxford University Press, 1975), p. 117; University of the Witwatersrand (hereafter Wits), Historical Papers Research Archive (hereafter Wits HPRA), Saffery Papers, AD 1178, H.D. Tyamzashe, ‘A Summarised History of the ICU by Henri Danielle Tyamzashe who was Complaints & Research Secretary ICU and Editor of ICU Newspapers’ (unpublished manuscript).

6 The interviews were among those conducted by the Sharecropping and Labour Tenancy Project and those conducted by Sylvia Neame, both kept at the Wits Historical Papers Research Archive. The archival documents are from the Justice Files in the National Archives and from a digitised collection of newspapers in the author’s possession. These include the Workers’ Herald, the official organ of the ICU, Johannesburg, 1926–1928.

7 Van Onselen, The Seed is Mine, p. 146.

8 C. van Onselen, ‘The Social and Economic Underpinning of Paternalism and Violence on the Maize Farms of the South‐Western Transvaal, 1900–1950’, Journal of Historical Sociology 5, 2 (1992), p. 132.

9 T.P. Clynick, ‘“Digging a Way into the Working Class”: Unemployment and Consciousness Amongst the Afrikaner Poor on the Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggings, 1926–1929’, in R. Morrell (ed.), White but Poor: Essays on the History of Poor Whites in Southern Africa 1880–1940 (Pretoria, University of South Africa, 1992), p. 77.

10 Wits HPRA, Sylvia Neame Papers, A2729, interview with Solomon Buirski, London, 9 November 1968 (hereafter Buirski interview), p. 76.

11 Van Onselen, ‘The Social and Economic Underpinning’, p. 131. Further similarities between farms and diggings were the hours of work and the ways in which work was circumscribed by the weather.

12 Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers’, p. 2.

13 Wits HPRA, Institute for Advanced Social Research (hereafter IASR), A2738, Tape no. 300, Transcript no. 51, interview with K. Maine conducted by M.M. Molepo in Ledig, Rustenburg, 28 July 1987; Buirski interview, p. 76; see R. Turrell, ‘The 1875 Black Flag Revolt on the Kimberly Diamond Fields’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 7, 2 (1981), pp. 201–03.

14 Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers’, p. 1.

15 Ibid., p. 9.

16 T.P. Clynick, ‘Political Consciousness and Mobilisation Amongst Afrikaner Diggers on the Lichtenburg Diamond Fields, 1926–1929’ (MA thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 1988), p. 46.

17 T.P. Clynick, ‘Afrikaner Political Mobilisation in the Western Transvaal: Popular Consciousness and the State, 1920–1930’ (PhD thesis, Queen’s University, 1996).

18 Buirski interview, p. 76; P.L. Wickins, ‘The Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union of Africa’ (PhD thesis, University of Cape Town, 1973), p. 265.

19 A. Daimon, ‘Settling in Motion: Nyasa Clandestine Migration Through Southern Rhodesia into the Union of South Africa, 1920s–50s’, WISER Working Paper 41 (2018), p. 22.

20 Van Onselen, The Seed is Mine, p. 170.

21 Ibid.

22 D. Money, ‘Underground Struggles: The Early Life of Jack Hodgson’, in K. van Walraven (ed.), The Individual in African History: The Importance of Biography in African Historical Studies (Leiden, Brill, 2020), p. 177.

23 Clynick, ‘“Digging a Way into the Working Class”‘, p. 79.

24 Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers’, p. 7.

25 Ibid., p. 4. This characterisation of the diggings was given by J.F.W. Grosskopf to the Carnegie Commission.

26 Buirski interview, p. 76.

27 Wits HPRA, IASR, A2738, Tape no. 570, Transcript no. 158; interview with I. Moeng conducted by T. Matsetela, Oersonskraal, 19 May 1987 (hererafter Moeng interview 1).

28 Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers’, p. 2.

29 Buirski interview, p. 76.

30 S. Plaatje, ‘Native Life at the Alluvial Diggings’, English in Africa, 3, 2 (1976) [originally published 1927], p. 65.

31 Ibid.

32 Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers’, p. 8.

33 ‘Lichtenburg Distress’, Rand Daily Mail, Johannesburg, 1 March 1928.

34 ‘Tit for Tat and Another Tit’, Workers’ Herald, Johannesburg, 18 March 1927.

35 ‘Lichtenburg Distress’.

36 ‘Diggings with No Police’, Rand Daily Mail, 25 May 1928. Crime was widespread; in this article it was reported that two murders and five homicides occurred over a single weekend at the diggings.

37 University of Cape Town (UCT) Archives, Lionel Forman Papers (LFP), B 3.137, Industrial and Commercial Workers Union, letter from Kieser and McLaren, Attorneys, to C. Doyle Modiakgotla re treatment of ICU members at Mafeking, Mafeking, 29 October 1927. Modiakgotla had sought legal advice from attorneys Kieser and McLaren who advised him to send a report to the ICU’s Head Office and the Minister of Justice.

38 UCT Archives, Lionel Forman papers (LFP), B 3.145, Industrial and Commercial Workers Union, holograph of letter from C. Doyle Modiakgotla to Champion re visit to the Grassfontein [sic] diggings, Kimberley, 1 November 1927.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid.

41 D.L. Spar, ‘Markets: Continuity and Change in the International Diamond Market’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 3 (2006), p. 196.

42 Ibid., pp. 197–9. Rhodes calculated that the number of diamonds that should be allowed into the market should be equal to the number of weddings occurring globally.

43 P. Hastings, Cases in Court (Auckland, Pickle Partners Publishing, 2018), pp. 134–5.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid., pp. 135–7.

46 See Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers’, p. 10 and H. Bradford, ‘The Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union of Africa in the South African Countryside, 1924–1930’ (PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 1985), p. 242.

47 See Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers’, p. 11; Clynick, ‘Political Consciousness and Mobilisation’, pp. 99–102 and Clynick ‘“Digging a Way into the Working Class”‘, pp. 89–90.

48 Clynick, ‘Political Consciousness and Mobilisation’, pp. 59–61.

49 Buirski interview, pp. 69–71.

50 UCT Archives, LFP, B 3.145, holograph of letter from C. Doyle Modiakgotla to Champion.

51 National Archives of South Africa (NASA), Secretary of Justice (JUS), 443, 3/524/28, letter from I.V. Raubenheimer to the Minister of Justice, 9 May 1928.

52 Ibid.

53 NASA, JUS, 443, 3/524/28, letter from the Office of the Deputy Inspector at Elandsputte to the District Commandant of the SAP at Potchefstroom, 29 May 1928. Pass laws required that black, Indian and coloured people carry documents which allowed them access to areas restricted by the state, often urban areas. They ran throughout colonial and Apartheid periods. The woman’s anti-pass march of 1956 and Sharpeville massacre are major political actions of anti-pass action and ensuing violence by the state.

54 Ibid.

55 NASA, Secretary of Home Affairs (BNS), 1/1/377, 194/74, ‘Natives from Rhodesia, Bechuanaland, Portuguese East Africa, British East Africa, Nyasaland Etc Etc: Influx of. (1924–1929)’, letter from Howe, inspector for the SAP at Elandsputte, to Deputy Commissioner of Police, 2 September 1927.

56 NASA, Government Native Labour Bureau (GNLB), 356, 45/24, 208/27/48 and 23/3/28, ‘Lichtenburg Labour District, Faction Fights: Blantyre Natives and Basutos’ (1927); ‘Fights at the Western Native Township: Houseboys Formed Part of the Attacking Force’, Times of Natal, Pietermaritzburg, 29 December 1927; NASA, BNS, 1/1/377, 194/74, ‘Natives from Rhodesia, Bechuanaland, Portuguese East Africa, British East Africa, Nyasaland Etc Etc: Influx of (1924–1929)’, letter from Secretary of Native Affairs, J.E. Herbst to Schmidt, the Secretary for the Interior, 12 June 1929; ‘Africans Versus Africans’, Abantu Batho, 9 February 1928; ‘Trouble at Western Native Township’, Umteteli Wa Bantu, 31 December 1927. It is claimed that ‘Central African Natives’ were ‘interfering with Native women’.

57 R.W. Msimang, ‘Congress Supports Deportation’, Umteteli wa Bantu, 11 February 1928; R.W. Msimang, ‘Congress Folly Exposed’, Workers’ Herald, Johannesburg, 15 February 1928

58 Ibid.

59 Ibid.

60 H. Dee, ‘Clements Kadalie, Trade Unionism, Migration and Race in Southern Africa, 1918–1930’ (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2019), pp. 127, 238.

61 Clynick, ‘“Digging a Way into the Working Class”’, p. 87.

62 Ibid., p. 89.

63 Money, ‘Underground Struggles’, p. 177. Buirski had worked together with the ICU and Kadalie at the Cape Town docks in the ICU’s formative years. In 1926 he addressed numerous ICU meetings held with mineworkers in Ferreiradorp. Later in 1926, he moved to Lichtenburg where he began to dig for diamonds and remembers addressing an ICU meeting on unity between black and white workers. See Buirski interview, p. 76.

64 Clynick, ‘“Digging a Way into the Working Class”‘, pp. 92–5.

65 Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers’, p. 12.

66 Ibid., p. 12.

67 Ibid., p. 16.

68 NASA, JUS, 920, 1/18/26, vol. 16–vol. 18, report given to the Officer in charge of the Criminal Investigation Department at Elandsputte, 25 April 1928.

69 Clynick, ‘Political Consciousness and Mobilisation’, p. 133.

70 Wits HPRA, Sylvia Neame Papers, A2729, interview with Keable ‘Mote, Pretoria, July 1962 (hereafter ‘Mote interview).

71 NASA, JUS, 920, 1/18/26, vol. 16–vol. 18, report given to the Officer in charge, 25 April 1928.

72 NASA, JUS, 920, 1/18/26, vol. 16–vol. 18, report given by the Officer in charge of the Criminal Investigation Department at Elandsputte to the Criminal Investigation Department at Elandsputte, 2 May 1928.

73 NASA, JUS, 920, 1/18/26, vol. 16–vol. 18, report from the Criminal Investigation Department in Potchefstroom to the District Commandant of the South African Police at Potchefstroom, 25 June 1928.

74 Simons and Simons, Class and Colour, p. 364; ‘Diggers and Natives’, Rand Daily Mail, 23 June 1928. The RDM provides a report of police putting the number of striking workers at 80,000 and Keable ‘Mote put the number of strikers at 60,000. ‘Mote interview.

75 Clynick, ‘The Lichtenburg Alluvial Diamond Diggers’, p. 12.

76 NASA, Secretary of Native Affairs (NTS), 2092, 215/280, Lichtenburg Alluvial Diggings, Native Strike, ‘Minutes of Meeting Held at the South African Police Station on Wednesday the 20th June 1928, Convened for the Purpose of Coming to Some Finality on the Question of the Native Strike’, 20 June 1928, p. 2. It was Major Cooke who had brought up this point.

77 Wits HPRA, IASR, A2738, Tape no. 535, Transcript no. 140, interview with P. Baraganyi conducted by M.M. Molepo, Boskuil, 5 August 1985 (hereafter Baraganyi interview 1).

78 Wits HPRA, IASR, A2738, Tape no. 560, Transcript no. 157, interview with P. Baraganyi conducted by M.T. Nkadimeng, Boskuil, 16 January 1987 (hereafter Baraganyi interview 2).

79 Ibid.

80 Bradford, A Taste of Freedom, p. 166. Note that this is her translation of Kas Maine’s words which in the original are in Afrikaans. Wits HPRA, IASR, A2738, Tape no. 264, Transcript no. 45, interview with K. Maine conducted by C. van Onselen, Ledig, Rustenburg, 24 February 1982.

81 NASA, NTS, 2092, 215/280, Lichtenburg Alluvial Diggings, Native Strike, ‘Minutes of Meeting of Diggers Held at Portion ‘U’, Grasfontein, on Monday Afternoon, 18th June 1928, at Lemmers Café in Connection with the Native Strike’, 18 June 1928.

82 Ibid.

83 NASA, NTS, 2092, 215/280, Lichtenburg Alluvial Diggings, Native Strike, p. 3. Comment made by Swanepoel.

84 Ibid., p. 4. Comment by Jooste.

85 Baraganyi interview 1. Sol Plaatje glosses Motati in Plaatje, ‘Native Life at the Alluvial Diggings’, p. 64.

86 Baraganyi interview 1; Baraganyi interview 2. Baraganyi gives two amounts, one being £5 and another £1 and 5 shillings. The £5 could be referring to the monthly amount; that is, £1 and 5 shillings weekly. The £1 and 5 shillings as a weekly amount would have been a 17-shilling increase from the post-reduction wage of 12 shillings, and only 5s more than the pre-reduction wage. This is an audacious demand considering their position relative to the diggers, De Beers and the state.

87 ‘Police for Diggings: Claim Work at a Standstill’, Rand Daily Mail, 19 June 1928; ‘Big Native Strike: Over 5,000 Stop Work at Diggings’, The Star, Johannesburg, 18 June 1928; Bradford, ‘The Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union’, p. 243.

88 NTS, 2092, 215/280, Lichtenburg Alluvial Diggings, Native Strike, p. 9. Comment by Swanepoel.

89 Ibid., p. 6. Comment by De Vos. In the South African Worker, it was noted that ‘two I.C.U. officials, who had been present when the cessation of work took place, advised workers to return to work shortly afterwards’; ‘30,000 Natives on Strike at Lichtenburg’, The South African Worker, Cape Town [?], 22 June 1928.

90 Interview with Solomon Buirski, pp. 69–71.