Abstract

South African historians have largely overlooked the night as a frame of historical analysis. This article is an initial attempt to rectify this by exploring Drum as a source for this endeavour. Drum provides insight into the South African night in the 1950s as both a symbol and experience, predominantly as it was understood and encountered by black South Africans. At this time curfew legislation and the intentional lack of lighting infrastructure provided to black urban areas sought to circumscribe black people’s nighttime activity. The apartheid state’s racial ideology cast black people as fundamentally rural and cut off from modernity, solely allowed in the city to provide labour. In this imagination, black people were seen as city people by day only, and should disappear at night to sleep. Nevertheless, Drum’s predominantly black writers positioned the night as a key site of their reporting and short stories, the site of ‘real life’, depicting a vibrant black urban nightlife. Consequently, Drum offers a catalogue of urban black South Africans’ nighttime activity, occurring despite curfew legislation. In this, Drum challenged the state’s prescribed temporality, insisting on black people’s modernity and urban identity, imaged through their engagement in a life by night. However, Drum juxtaposed its descriptions of this vibrant night with reporting and depictions of nighttime crime predominantly located in African neighbourhoods, challenging the government’s infrastructural neglect that was held to be responsible for the danger of these areas at night. Further, in writing about black urban nightlife, in South Africa and abroad, Drum allowed its predominantly black readers to vicariously experience nighttime activity, facilitating the evasion of the curfew’s curbs on mobility. Here, Drum drew its readers, and placed black South Africa generally, into a globally imagined project of black urban modernity, represented, expressed and experienced through the night. Thus, in their struggle over the night in the 1950s, black South Africans and the apartheid state struggled over black modernity itself.

To listen to alongside this article Todd Matshikiza and Bloke Modisane recommend in their respective columns: The African or Harlem Swingsters, Dorothy Masuka, Dolly Rathebe, Elijah Nkwanyana, The Skylarks, Kippie Moeketsi, Dollar Brand or Spokes Mashiyane.Footnote1

The night in 1950s South Africa, like much of South African society, was differently produced along racial lines. While white residents freely suffused South African cities at night, racialised curfew legislation kept black residents within the peripheral townships designated for their occupation after 10 or 11 p.m.Footnote2 Furthermore, a comparatively deficient provision of artificial lighting within these townships produced a separate experience of the night in comparison to that in the central cities they fringed.Footnote3 The segregationist philosophy of the South African state since at least the 1920s, legislated through the pass laws, influx control and the Urban Areas and Group Areas acts, was that black Africans worked, but did not live, in cities. The site of their social and community life was understood to be in rural areas. Black people were imagined as fundamentally tribal, alien to city life and cut off from modernity. Their presence in the city, the claimed domain of the white man, was predicated on their provision of labour.Footnote4 In this imagination, black urban residents were city people by day only. They were workers, diurnally generative of value through their labour, who should spend their nights in the city at rest – in preparation for the next day of work. Although this ideology did not originate with the National Party, it was enacted more forcefully after 1948 following the onset of apartheid.

Despite this, a subversion took place and black urban residents engaged multifariously in nighttime activity over this period. In his book on nightwalking in London from the medieval period to the mid 19th century, Matthew Beaumont argues that being out at night, after all ‘respectable’ citizens had retreated indoors or gone to sleep, represented a challenge to the dominant ‘diurnal regime’.Footnote5 Like Beaumont’s nightwalkers, the participation in nighttime activity by South African black urban residents can be approached as a challenge to the prescribed temporal order of the South African state. A vivid record of nighttime activities and happenings from around South African black townships can be found in the pages of the much-studied, predominantly black-produced and -read magazine Drum. Over the 1950s Drum emerged as the most widely read black-produced magazine in Africa and at its height, in 1956, had a circulation of over 70,000 copies throughout Africa, Europe and the USA.Footnote6

Drum has been approached by many scholars as an expression of, and point of construction for, New Africanism, alongside South African black urban modernity, identity and subjectivities after a period of rapid black urbanisation following the Second World War.Footnote7 What is missing from Drum scholarship, however, is the recognition that, in writing a magazine to express the interests and values of a burgeoning black urban population, Drum’s writers routinely used the night as the backdrop for and symbol of this emergence. This article develops the arguments present in existing scholarship, adding the night as a key site against which and wherein Drum’s authors felt that urban modernity and identity could be explored, represented and performed. Moreover, it approaches the mobilisation of the night in the magazine, alongside the other elements of Drum’s night-writing, in order to examine how the night was conceived, understood and encountered by Drum’s writers and readers in the 1950s.

Whose ‘Real Life’? Considerations in Using Drum as a Source

Before stepping into the night through Drum, three caveats must be noted. First, Drum’s writers predominantly came from South Africa’s emergent urban petty-bourgeois or professional class. They were either sons of – or working themselves as – teachers, clerks or small business owners and therefore cannot be said to represent the interests, views and experiences of black urban society broadly.Footnote8 That being said, class in South African history is a complex phenomenon and does not fit neatly into a framework for analysis. While there did exist a differentiated, albeit ill-defined, group of better-educated, wealthier black urban residents, apartheid legislation grouped most black city residents together within townships, irrespective of wealth and societal position. Further, this same legislation constrained black people’s financial, social and political opportunities for advancement even for the more affluent.Footnote9 The line between Drum’s presumed ‘petty-bourgeois’ writers and other supposed ‘working-class’ black urban residents was not so clearly defined.

Nevertheless, performing respectability, in opposition to disreputable ‘others’, was very much a part of township life at this time. Following David Goodhew and Lynn Thomas, respectability is understood as the commitment to, and performance of, a malleable set of values related to economic independence, religion, education, law and order, neatness and cleanliness, among others.Footnote10 Concepts of modernity and respectability were interlinked and the performance of the one often involved the performance of the other. Thus, Drum was entirely involved in this process. The magazine established itself as an arbiter of modernity and respectability, declaring and debating what was respectable in its pages, shaping fashion trends and marking distinct ‘others’, mostly particular groups of black Africans, as backwards and traditional, against which they performed their own modernity. In this, Drum’s writers paternalistically understood themselves as edifying their black readers. Drum therefore still cannot be claimed to ‘speak for the people’. However, this too requires qualification before simplistically declaring Drum a vehicle of the ‘elite’. Respectability was by no means the sole preserve of a potential ‘black middle class’.Footnote11 Further, Drum’s readership often comprised a broader black public than people whom Drum’s writers would class as ‘respectable’. This wider public of readers found value in the magazine and utilised it for their own purposes, beyond a one-dimensional vision of edification.

Second, Drum was produced almost entirely by men and was filled with the objectification and infantilisation of women.Footnote12 The stated formula for selling the magazine was ‘cheese-cake and crime’ (cheese-cake being a derogatory term to describe beautiful women).Footnote13 In Drum women were largely written about as objects who gained importance through their relationship with men.Footnote14 Even in the case of women who were approached as important figures, like the jazz singers Miriam Makeba, Dolly Rathebe and others, men were rarely far away. The 1957 profile of Rathebe by Can Themba entitled ‘Dolly and her Men’ is just one example of this.Footnote15

Finally, Drum was not a utopic, non-racial magazine and workplace that provided an escape for its black writers from the oppression of early apartheid. While Drum’s black journalists had large amounts of creative control over the publication during the 1950s, they were also exploited with poor pay and steered towards producing a less ‘radical’ magazine. This has led many of these writers to express dissatisfaction with parts of Drum after leaving the paper. Drum’s journalists referred to the salary paid by the magazine as a ‘monthly mockery’ and Bloke Modisane declared in his autobiography that the magazine, along with the rest of the white-owned black press, was ‘more yellow than black’.Footnote16

Nevertheless, these considerations are representative of greater societal trends, all of which had their effect on the ideas and experiences of the night at the time. These found representation in, and were contributed to by, Drum’s reportage. Drum’s night-writing reveals a series of views, prejudices and social stratifications internalised and produced by Drum’s predominantly male, ‘respectable’ writers, alongside other members of the amorphous black ‘respectable’ class, and their specific activation in relation to the night and nighttime activity. It is important to keep these factors in mind when examining Drum, which because of these inflections, and not just despite them, provides an important, albeit refracted, view of the black urban night in 1950s South Africa.

‘It was the season of light, it was the season of darkness’: Inversion and the Night as ‘Real Life’

Towards the end of 1951 The African Drum – an almost entirely white-produced magazine, nevertheless aimed at black readers – reorganised itself as Drum in response to dismal sales. The owner, Jim Bailey, who was haemorrhaging money at this point, replaced the editor Bob Crisp with his former Oxford contemporary Anthony Sampson and promoted The African Drum’s only black writer, Henry Nxumalo, to assistant editor. Subsequently, Nxumalo and Sampson brought on various young black writers like Todd Matshikiza, Arthur Maimane, Bloke Modisane, Ezekiel Mphahlele, Can Themba and others to help run the magazine. Although Sampson was Drum’s official editor, the decisions regarding the content of the magazine largely were left to Nxumalo and the other black writers. While The African Drum had presented an image of African people aligned with apartheid tribal fantasies, the express goal of Drum’s new writers was to produce a magazine that addressed what they perceived as the realities of black urban life and reflected the aspirations and ideals of modern black city dwellers.Footnote17 Modernity is a slippery concept, defying a stable or easy definition. In an attempt at a working understanding, however, modernity is approached here as a set of social practices, produced out of a generation’s asserted sense of itself as living in a present that is undergoing a process of such rapid technological, economic, political and social transformation as to starkly separate it from all that has come before. Moreover, modernity is equally an aspiration to be ‘modern’, largely without a definite meaning. It is an open sign, a metaphor for newness juxtaposed against an older ‘other’, which acquires variable meanings and understandings in relation to local specificities wherever it appears and is claimed.Footnote18 Therefore, to be modern is partly to insist on and actively perform one’s own modernity, however that is understood.Footnote19 Drum did exactly this. The specific modernity performed by Drum involved a rejection of a supposed ‘tribal’ existence, with its perceived superstitions and demands, in favour of the celebration of urbanism, individuality, transnational black identity, technological progress and scientific rationality. Drum simultaneously pushed against the imposed apartheid conception of an essentially rural African population of happy tribes living in agrarian communities and what it perceived as the internal traditional aspects of South African black communities, targeting specifically occult belief and age-based patriarchal control.Footnote20 The response to these changes was undeniably receptive and the magazine’s sales increased exponentially.

Central to Drum’s modernity was the night and nightlife. With the maturation of public electric lighting in cities around the world in the first half of the 20th century and the concurrent proliferation of various respectable nighttime leisure activities available to the average, as opposed to elite, city dweller, nighttime activity became a global hallmark of city life, a key part of being and feeling modern, and the nightlife column became a permanent fixture in many city newspapers and magazines.Footnote21 In this way, being a part of urban modernity and living in the night were constructed as entangled; cities never slept, and to be urban and modern was, in part, to occupy the night. In attempting to steer their magazine towards representing and expressing the former, Drum’s writers focused on displaying the latter.

Drum’s representations of cities around the world often found them at night. One of the first additions to the new Drum, in late 1951, was a column called ‘Negro Notes from U.S.A.’, which displayed as its header an image of New York City at night ().Footnote22 In later years, reports from the USA and Europe repeatedly appeared in the magazine, more often than not accompanied by images of their big cities at night. In many cases these articles focused on nightlife in these far-flung places; however, even when they did not, the overwhelming image of the city that accompanied the text was of a nighttime scene.Footnote23 This was the case not only for Drum’s writing, but also for the advertisements which filled its pages, selling their products as commodities of the modern citizen, juxtaposed against a nighttime cityscape.Footnote24 Cities were imagined at night, and the images taken to represent the overseas black urban population, with whom Drum sought to commune, were images of people participating in a lively nightlife.

Figure 1. Photograph of the header of Drum’s regular column ‘Negro Notes from U.S.A.’. (‘Negro Notes from U.S.A.’, Drum, Johannesburg, October 1951, p. 10. Copyright © Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online / african.pictures.)

Moreover, in placing its focus on the night Drum was able to oppose apartheid-prescribed images and imaginaries concerning the place of Africans in urban society. The new Drum saw itself as responding to the call voiced by an interviewee in 1951, in a phrase which has since become the foundation myth of the magazine: ‘[y]ou can cut out this junk about Kraals and folk-tales. … You’re just trying to keep us backward…Tell us what’s happening right here, man, on the Reef!’Footnote25 Drum’s claim to focus on ‘real life’ should not be taken at face value, as representative of what actually appeared in the magazine. In fact, Njabulo Ndebele has criticised Drum’s writing precisely for dramatising the spectacle of the powerful against the powerless – understood to typify apartheid – by presenting abstractions, as opposed to people’s ‘ordinary day-to-day lives’.Footnote26 Rather, the desire to present ‘real life’ taken in relation to what appeared in Drum’s pages is indicative of how these writers conceived of ‘real life’ in the first place. Drum did not consider all aspects of life to be deserving of equal attention. Daily labour garnered little coverage, only receiving mention in the regular ‘Masterpiece in Bronze’ features – which profiled various influential black and coloured figures – and in occasional exposés on farm labour, albeit ones that achieved much public attention. Nevertheless, Drum’s farm labour pieces were concerned with a kind of labour beyond the daily experience of Drum’s urban writers.

Instead, Drum focused the majority of its writing beyond the workday, centring its gaze on the night. Drum published innumerable articles detailing and describing nighttime activities and happenings occurring in and around Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban and other sites, predominantly urban, throughout South Africa. Drum’s night coverage included but was not limited to descriptions and accounts of night schools, beauty competitions, boxing events, jazz, theatre and opera performances, dance parties, drag evenings, political meetings, shebeen drinking, gang violence, theft and murder.Footnote27 Additionally, Drum furnished its readers with short stories which recounted nighttime activity, featuring characters holding political meetings, as in Mphahlele’s ‘Blind Alley’, attending dances, going on dates, watching movies and listening to public lectures, as in Duke Ngcobo’s ‘Never Too Late for Love!’ or Themba’s ‘The Nice Time Girl’, drinking in shebeens, as in Ben Dlodlo’s ‘Kickido’, and perpetrating, investigating or falling victim to crime, as in Mbokotwane Manqupu’s ‘Love Comes Deadly’ or Maimane’s neo-noir investigator serials.Footnote28 In 1956 Mphahlele, then Drum’s fiction editor, reiterated the magazine’s philosophical underpinnings, by insisting that black writers had a duty to write about the ordinary lives of Africans.Footnote29 In fulfilment of this, Drum’s fiction writers, like their reporter counterparts, looked to the night as the site where this life could be found. In both their reporting and short stories, Drum’s writers conceived, presented and performed the night as the predominant site of the social, the ‘real life’ it desired to display.

Thus, Drum inverted the dichotomy of working day and restful night. Instead, the night was situated as the zone of activity where black urban residents were able to take control of their time, partake in self-defined activity and construct and participate in community. With the end of the workday came the dawn of the neighbourhood, as the impending curfew and labour rhythm ensured that racial segregation became truly visible at night. Space was segregated by time. While during the day the townships emptied, with people leaving to work in the central city, at night these workers returned. However, unlike in the state and white societal imaginary, which presupposed that these workers were returning only to sleep, Drum presented the township as enlivened in the evenings. A November 1955 article described this evening awakening: ‘[i]t’s the end of any normal working day. And the time – 6 p.m. As if suddenly brought to life, Wattville location in Benoni is packed with chattering, slow walking people. Along the main road crossing the bridge a stretch of workers enter the location’.Footnote30

Themba made use of a similar inversion in a 1958 article, referring to those he found hanging around the township during the day as ‘lotus-eaters, sun-worshippers, street corner loiterers, elegant, well-dressed ne’er do nothings, ever-drunks, shebeen-sitters, and just dead-eye gazers’. This image of lazy day-loafers was counterposed with those who, like himself, ‘galley-slave it away in the city’ during the day.Footnote31 Themba wrote about those who remained in the townships during the day as if they were dazed or asleep, particularly the ‘dead-eye gazers’, in terms which would typically be reserved for the night. ‘Sun-worshipper’ used pejoratively here is also interesting, as if in Themba’s opinion reverence of the daytime was a sign of moral or social deficiency. As Themba wrote it, the day offered two possibilities for township residents, either to ‘galley-slave it away in the city’, receiving little enjoyment or reward, or to loiter about the townships, effectively asleep. In contrast, the night appeared as a time-space where a degree of fulfilment could be achieved, as positioned, for example, in Themba’s article detailing his nighttime ‘ramblings’ around Sophiatown’s shebeens. Upon entering Little Heaven, ‘Sophiatown’s poshest shebeen’, Themba described the lively scene: ‘[m]odern jazz music of the hottest kind blared at me. And the room was crowded by African men and women sitting in clusters of threes and fours, enjoying – most of them – beer’.Footnote32 This configuration, of the townships enlivened at night, is nonetheless indicative of Drum’s class and gender biases. According to Drum, the ‘correct’ place to be during the day was at work in the city. This took an antagonistic position towards the unemployed and largely ignored the experiences of women, many of whom remained in the townships during the day.

After Drum phased out the short story for commercial reasons from 1958, the place of fictional writing in the magazine was taken over by Casey Motsisi’s ‘On the Beat’ column, which continued Drum’s authors’ focus on the night. The column ran from April 1958 into the 1960s and depicted a satirical, exaggerated, pseudo-autobiographical account of Motsisi’s nightly escapades, often in search of a drink.Footnote33 This was a character living for the night, consistently escaping work early to engage in nightly pleasures. Further, many of the shebeens in Motsisi’s tales were based on ones which were situated within Johannesburg itself, one of them a ‘stone’s throw’ away from the major Johannesburg police station at Marshall Square; Motsisi’s life by night within these shebeens, therefore, more directly challenged the temporal order by flouting curfew regulations.Footnote34 The column was popular among Drum’s audience and for some may have mirrored their own temporal orientation. In 1959 Drum received a letter from a pseudonymous ‘Kid Jerry’ in praise of Motsisi, inviting him to drink with him at his preferred shebeen.Footnote35 However, more than reflecting the lifestyle choices of some of Drum’s readers, Motsisi continued to centre the night as the temporal zone where a person truly came alive.

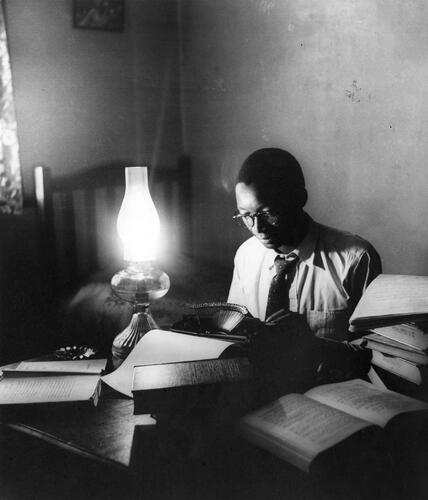

In all of this, Drum wrote the night as a new dawn which enabled an alternative set of possibilities and opportunities to the day. With the repressive control of labour during the workday, the night was a site where, to a degree, black urban residents could determine the expenditure of their time and write their own story, both figuratively and literally. Drum’s contributors made use of the freedom that the night allowed them to write. In April 1953, prior to joining Drum’s permanent staff, Themba won Drum’s first short story competition. Drum’s subsequent celebratory interview with Themba and the accompanying photograph () testify to his nocturnal writing process:

Figure 2. Can Themba photographed by Jürgen Schadeberg. (‘£50 Winner of Short Story Contest’, Drum, April 1953, p. 21. Copyright © Jürgen Schadeberg – Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online / african.pictures.)

When his work as a school teacher is over for the day, Themba seeks the peace of his room, where he can work. But peace rarely comes until after midnight. ‘I must wait until they’re all asleep’, Themba remarked patiently. ‘I don’t start writing until after 12 sometimes and then my room-mate snores. If I’m to get anything done I must work on until 3 and often 4 in the morning. It’s the best time to work here. But it’s tiring on the eyes – working by lamplight’.Footnote36

Here, the night appears not just as a time of extroversion but also one of introversion – a quiet time that facilitates personal and intimate practices. In a similar sense, the character Barney in Manqupu’s short story ‘Love Comes Deadly’, takes the opportunity which the night provides to stay inside and read, rather than hitting the town. The scene is lyrically described by Manqupu:

A velvet pall, which has silently and smoothly slid over the light of day, hung over Alexandra Township. And under its softness and the myriad of tiny stars that flickered like diamonds in a lovely evening frock, hid the filth and wickedness of this slum area. In this evening frock the ‘Dark City’ as it is called could compete for loveliness with any other town and hold its own … Children’s voices had quietened and the softening of voices from the homes and shebeens was a sign that the embers of the day’s revels were slowly dying out … Barney turned the page of his novel, chuckling as he did.Footnote37

Drum wrote the night as a temporal space where people actually lived, rather than existed, beyond their menial ‘working day’. Contrary to the apartheid imagination, the black urban night in Drum was not a dead space but one alive with black people achieving a kind of self-expression that the materiality of the South African state sought to deny them. In this, by situating the black urban night as the time-space of ‘real life’, presenting therein a vibrant social and community life within urban townships, Drum’s writers performatively wrote against the conception of essentially rural Africans, insisting on their existence as true modern, urban citizens, and asserting themselves as more than just articles of labour. Drum contended that black Africans did not just work in cities, they lived in them too, using the night to write themselves into the city, to borrow a phrase from Meg Samuelson.Footnote39

Simultaneously, Drum’s positioning of women within this nighttime space was a significant part of presenting this image. As various authors have discussed, women played an important role within Drum’s formulation of modernity. Drum used women as a site and symbol of modernity, both an example of liberation, by holding up the claimed new freedoms available to women within the urban milieu, and a point of discussion over which to debate its limits. Drum’s approach to ‘modern women’ was therefore multifarious, both exalting these freedoms but denigrating the supposed breakdown of their purity and virtue; the city presented as liberator and defiler in equal measure.Footnote40 The place of women in Drum’s nighttime world was no different. Women were ever present in Drum’s night. In the various articles, short stories and photographs of the night that Drum published, women were consistently represented. In Drum’s nightlife photographs especially, depicting scenes both inside and outside South Africa, women were placed in the forefront. On the one hand this can be seen as an extension of Drum’s use of images of women to sell their magazine. However, on another level this underlines the importance and centrality of women in this emerging urban nighttime public social space. Female participation in this nighttime space was a key part of its operation. Part of the modern night was the co-presence of men and women out, together, at leisure, allowing for the possibility of sociability across gender lines and romance. The modern woman was an active participant in nightlife and her presence was a constitutive part of the modernity of the field itself. However, the night was also presented as dangerous, and a site wherein women could be corrupted. Although Drum was happy to depict women engaging in nightlife, their participation was always set within particular social codes. In Drum’s reporting and short stories men often appear out alone at night; however, women always appeared in groups often inclusive of male escorts. Describing the scene in Little Heaven, Themba remarked,

In a corner … I saw three very respectable people, two men and a woman sipping quietly from their glasses. The woman was a very well-known staff nurse. She caught my eye and smiled sweetly at me. The men turned round and I recognised two teachers from one of Sophiatown’s primary schools.Footnote41

Here, the staff nurse is acting within Drum’s prescribed confines of femininity within the nightlife space, accompanied by ‘respectable’ male friends and acting diffident and demure. Meanwhile, Drum’s pages are filled with cautionary tales of women led astray within the nightlife world of drink, dance and sex. In Drum’s reporting and short stories, drunken women, sex workers, nightclub singers with murderous intentions, among others, all variably appeared as indicative warnings of the dangers to morality and virtue the night held if the renegotiated social codes were broken and things were left to go too far.Footnote42

Drum further reckoned with the ‘modern woman’ and the night in its representation of another two archetypal nighttime figures, the jazz singer and the ‘Shebeen queen’, the latter referring to the women who owned and ran the township watering holes. Both of these figures found some degree of economic advancement and independence within the emergent world of the modern urban night. However, Drum’s depiction either hyper- or desexualised these women. Jazz singers like Dolly Rathebe were often subject to hypersexualisation, with bikini-clad pictures of Rathebe, accompanied by infantilising text, often appearing in the pages of the magazine.Footnote43 Rathebe may have gained a degree of wealth and fame in her own right, but she was still required to make herself available to Drum’s male writers and readers. Meanwhile, the ‘Shebeen queens’ were often desexualised, as in the case of the large, overbearing and mannish ‘mountain of flesh’ Aunt Peggy from Motsisi’s ‘On the Beat’ articles, or the aged Ma Nkosi from Ben Dlodlo’s short story ‘Kickido’.Footnote44 Dorothy Driver and Rachel Johnson have argued that this was part of a process aimed at reasserting male control over these women, who were thought to have become increasingly empowered within cities.Footnote45 The emergent night-space described by Drum provided women with new opportunities, both social and economic. Although Drum was supportive of some these changes, its discussions and representations of women at night attempted to negotiate women’s newfound place within urban society, performatively restricting and limiting it in particular ways, thereby reasserting masculine control. Nevertheless, it remains important to underline the key role played by the presence of women at night within Drum’s modernity. Drum’s image of modernity contained women participating in, albeit in a limited way, and themselves in some way symbolising, the pleasures of the night. In many of Drum’s arguments against the proclaimed traditional patriarchal authority of chiefs and family units, its writers merely sought to replace this with their own form of patriarchal control and domination. Nevertheless, the nighttime leisure space that the magazine attempted to produce, perform and represent did allow women newfound possibilities for public presence, sociality, and a degree of independence – albeit restricted, differentiated and mediated through men. A full treatment of the place of gender within Drum’s night requires considerably more space and time than is available within this article, and is deserving of a specific study in and of itself.

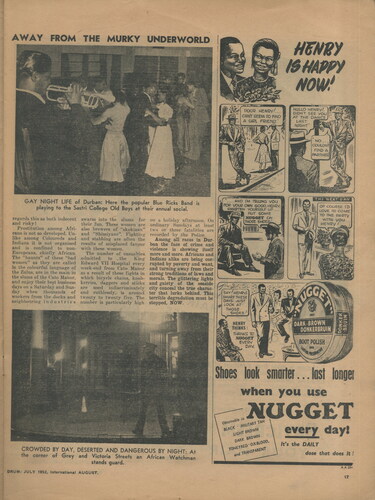

All of this is not to say that Drum presented the night as a site of pleasure alone. Crime and the threat of harm that it produced was an entangled part of Drum’s ‘real life’ and found ubiquitous coverage in the magazine. The quiet nighttime scene established by Manqupu is quickly interrupted by Barney’s murder: ‘[a] scream tore through the velvet pall, into the dark, insensate night’.Footnote46 The night in Drum was a dual space of pleasure and possibility on the one hand, and fear and constraint on the other. This vision is perhaps most vivid in Drum’s 1952 article on Durban. Here, Drum juxtaposed two photographs, one depicting Durban’s ‘gay night life’ and the other the menacing nighttime streets of the city’s ‘underworld’ (), declaring ‘[a]s night steals over this city of startling contrasts – wretched slums and palatial mansions – its streets, mostly respectable shopping centres, during the day, become the happy playground of the thousands of crooked and vicious elements which night aids and abets’.Footnote47 Drum constructed the city as a space of Manichean oppositions and the night as bringing these into sharpest contrast.

Figure 3. Drum’s 1952 depiction of the two sides of the night in Durban. (‘Durban Exposed: City with Two Faces’, Drum, Johannesburg, July 1952, p. 17. Copyright © Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online / african.pictures.)

Although Drum’s Durban article focused on the city as a whole, the main focus of nighttime crime and violence in the magazine fell on the townships. The lack of public lighting and a police force apathetic towards combating township crime aided this criminal activity and often faced objection from Drum.Footnote48 As a result of the former, Alexandra Township, to the north of Johannesburg, became colloquially known as ‘the Dark City’. As exemplified in Manqupu’s ‘Love Comes Deadly’, Drum’s authors revelled in the polysemic possibilities of this title, often in their use of it slipping between the literal and the figurative.Footnote49

Additionally, in Drum’s regular coverage of the various city gangs over the decade, the gangs were reported to be using the night’s darkness to their advantage, either to startle unsuspecting victims or to conceal their smuggling, gambling and theft from the law. For example, in 1954 Drum reported that due to the Globe Gang’s activities, ‘Cape Town docks at night are one of the city’s focal points for crimes ranging from smuggling to murder’.Footnote50 Most connected to the night was the Torch Gang. As Drum reported in 1955,

They [the Torch Gang] would move around from Moroka to Jabba, Orlando, White City, Orlando West, up to the Orlando Shelters. This whole area has no lights. When they approach a likely victim, the leader would flash the torch in his eyes. The light would blind him and the gang would pounce upon him.Footnote51

If Drum approached the night as the site of real life, this real life often involved fear, danger and the threat of harm. This was exacerbated on payday nights, which Drum labelled ‘the devil’s birthdays’.Footnote52 The anxiety of returning home in the dark on payday is captured in Drum’s 1957 article ‘Terror in the Trains!’:

Friday night and the end of the month to boot. That’s why joining the hordes that flowed into Park Station Johannesburg Isaac Moeketsi of Dube – and thousands like him – was scared. He had to a more intense degree that sinking, uneasy feeling he always got when he had to board any of these location trains. More intense because he knew that robbers would be making extra effort on this most special of nights.Footnote53

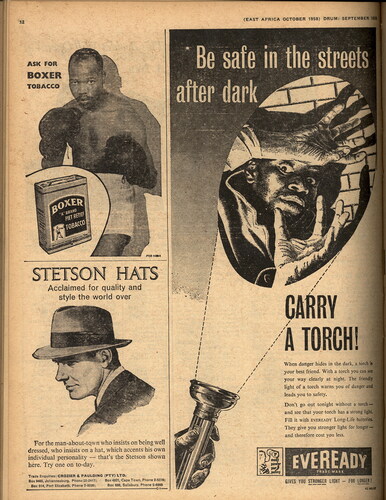

The darkness of the night and the fear it produced can also be seen in the Eveready battery advertisements which appeared in Drum, often near articles on crime (). These attempted to tap into and produce particular anxieties about the dark night to sell their product and, like Drum’s reporting and short stories, can be taken as being both representative and generative. One advertisement declares that ‘[t]here is no need to be afraid in the dark if you carry a torch. Evil doers depend on darkness to do their work – but light scares them away’.Footnote54 Another warns that ‘[d]arkness is a time of danger – but you will have no need to fear sudden, unexpected attacks and accidents in the streets at night if you carry a torch’.Footnote55 In these, the night appears as a frightening time, where its blinding darkness facilitates criminal activity. Significantly, for residents of the dark townships, the primary object Eveready chose to illustrate the necessity for its batteries was the torch.

Figure 4. An advertisement for Eveready Batteries in Drum. (Drum, Johannesburg, September 1958, p. 12. Image ref. APN33809, 98_886. Copyright © Drum Ads / Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online / african.pictures.)

Drum did not ignore the dark side of the night and consequently held up the effects of successive governments’ neglect as a call for change. In his 1957 precursor to ‘Terror in the Trains!’, Themba stated, ‘[i]t’s time the police … made it safe for us to go home at night’.Footnote56 A year later Themba voiced his ire in biblical terms demanding, ‘[l]et there be light!’, in response to damning nighttime crime statistics. He continued,

I made a staggering discovery the other day. It looks as if one in every two of our urban women can expect to be raped during her life-time. It happens in all townships. In the dark streets and alleys of Alexandra. How long have people cried out for light there? In the half broken down ruins of Sophiatown. It happens in and near the railway stations of greater Orlando. I know I’ll look naive if I ask for more policemen in these stations, but I am asking for more.Footnote57

In its focus specifically on the need to light and police trains and train stations, Drum directed blame towards the materiality of segregation’s labour rhythm. The flow of black workers into the city aboard trains and buses in the morning and out again the same way in the evening produced a commuter zone, bridging night and day, wherein crime found possibility for presence. As depicted in Themba’s outcry, women found the night particularly dangerous. This feature was expressed by Marion Morel, Drum’s ‘Girl About Town’ and one of the magazine’s only female writers in 1959: ‘[o]ne of the greatest problems for women and all women of South Africa is I think the problem of getting around. What women ever dare go out alone? Not me’.Footnote58

In ‘Crepuscule’, reflecting on Johannesburg’s townships in the 1950s, Themba wrote, channelling Charles Dickens, ‘[i]t was the best of times, it was the worst of times … it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness’.Footnote59 Following Themba, Paul Gready has claimed that in Sophiatown ‘the best and worst of black urban life were bedfellows’.Footnote60 This is palpable in Drum’s coverage of the night. Drum’s reporting, advertisements and short stories provide an image of the urban night as containing and producing both the heights of pleasure and the depths of fear. On the one hand, the townships around South Africa’s major cities at night teemed with life as their residents returned from work in the cities. On the other, the night in these areas, without public lighting, was dark, dangerous, and left one vulnerable to attack. Perhaps the present danger of the night heightened the experience of nighttime pleasure. Perhaps together these two affective extremes were interdependently involved in ‘feeling alive’. Nevertheless, what is clear is that Drum conceived and performed the night as the time-space of ‘real life’, with its component pleasures and pains, where a different reality to that of the day was possible. As Drum reported in 1960, ‘[s]trange things happen when the lights are low. The words of the great King Kong song couldn’t be truer’.Footnote61 Through this framing and the related nighttime coverage, Drum performed black nighttime urban activity in its pages, in direct contradiction to the apartheid state’s denial of its existence. Drum inverted the presupposition of black labour as active during the day and inactive at night, thereby asserting black urban permanence and modernity, framed in relation to a global trend towards urban nighttime activity, in the face of a system which refuted it. Further, Drum displayed the results of the state’s uneven service provision, a night – and therefore a real life – awash with crime and danger. Thus, it is possible that Drum saw itself as an illuminating force, shining light on the night’s delights and despairs. In constructing the night in these terms, Drum challenged the state’s racialised ideology on two fronts, a two-pronged manoeuvre in the struggle over the night.

‘Drum should be called Sputnik’: Travelling to the Night

In an additional move, Drum provided the opportunity to elude curfew laws and curbs on mobility. Drum’s writers wrote the night as a different and unfamiliar place to the day and offered its readers a chance to journey alongside them through this dark land. In this way, Drum’s writing on the night emerged as a kind of travel writing which produced a reading public able to vicariously experience and participate in black urban nightlife all over South Africa and the world.Footnote62 In 1958, Themba, following up an article on the ‘night spots of Harlem’, declared that ‘MR. DRUM has a name as a traveller’.Footnote63

At its most mundane, travel writing is a narrative, first-person account which describes the author’s movement through a foreign place, detailing its people, objects and landscapes.Footnote64 However, the genre has been closely tied to and is implicit in a history of imperialism, orientalism and colonialism. European travel narratives since the 15th century have performed the intellectual work of marking non-Europeans as distinct ‘others’, utilising them as the backdrop for their narratives of a European civilisation pitted against savagery which were used as justification for imperial progress.Footnote65 Nevertheless, scholars like Rebecca Jones have attempted to trace a largely independent history of travel writing, produced by and for black Africans. In her book on intra-Nigerian travel writing, from its appearance in particular forms of precolonial oral storytelling through to 21st century iterations, Jones argues for the need to examine the travel narrative as more than an inherently western genre.Footnote66

Significantly, in a chapter on travel writing in Lagos newspapers in the 1920s, Jones cites two main aims of travel writing identified by the authors of these accounts. First, to allow those who could not travel to foreign lands a chance to do so vicariously and, second, to orientate the writer and reader within the newly united colony of Nigeria, connecting unfamiliar places to readers back home.Footnote67 In a similar manner, Drum’s writers wrote the night as topos through which the reader could be guided, providing them with access to worlds otherwise out of reach and orientating them, and black South Africans generally, within a global world of urban nightlife.

The manner in which Drum led the reader differed by author, however, as the night narratives of each of Drum’s writers were augmented by their respective interests and influences. As a musician and composer, Matshikiza’s main concern in his articles was music, specifically jazz, and any place that it was played, including dance halls, private parties, shebeens and living rooms. In this, Matshikiza wrote about specific places and events, rarely moving between them in the space of a single article. With plenty of large-spread photographs and a snappy writing style nicknamed ‘Matshikeze’, these articles brought the jazz up off the page and placed the readers in the centre of the nighttime action.Footnote68 Nxumalo on the other hand investigated the night, searching for its darker aspects in a bid to shine the light on all that the night would hide. In his exposés on crime in South Africa’s big cities of Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban, Nxumalo took the reader on a tour of the cities by night, indicating key spots of criminal activity:

Johannesburg’s ‘red light district’, sometimes known as the ‘Square Mile of Sin’ is notorious not only for prostitution but for the crimes that accompany it – robbery, assault and pickpocketing. The east end of the city, centring around Polly Street and Nugget Street, is used as a night parade for street walkers.Footnote69

Drum performed the night to be consumed and experienced through its pages. In addition to written text, much of this night-writing was accompanied by photographs that extended Drum’s reach to those who could not speak or read English.Footnote72 Even for those that could, this added a visual medium through which to experience the night. The image in is significant for its use of overlay, superimposing two images on top of each other to provide a more evocative photograph able to transmit the feel of movement and vitality emanating from the musical performance its accompanying article described. Additionally, Drum’s regular column offering record suggestions and reviews, written first by Matshikiza and then by Modisane, provided a guided soundscape of the night, transmitting what was playing in city clubs and shebeens into readers’ houses – for those who could afford a record player.Footnote73

Figure 5. Drum’s coverage of ‘Big Jay’ McNeeley performing in California. (‘Go! Go! Go! “Big Jay” Sends Jazz Fans Crazy!’, Drum, Johannesburg, May 1953, p. 19. Copyright © Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online / african.pictures.)

In the first instance, this allowed Drum’s rural readers to participate in black urban nightlife within South Africa despite their geographical removal from it. Readers’ letters to Drum that were published in the magazine provide a loose idea of the geographic scope of Drum’s readership. In addition to its urban readers, Drum had an audience in Peddie, Mount Frere, Shongweni, Ladysmith, Kwambonambi, Vryheid, Komatipoort Potgietersrus, Kroonstad, Kuruman, Koegasbrug, Schilpadfontein, Worcester, and many other places far beyond Sophiatown, Newclare and Orlando.Footnote74 In its coverage of various nighttime activities, Drum acted as a proxy for people all over South Africa, providing them with a chance to engage in this nightlife. This inspired Rex Ndimande to write to Drum in 1953 from Piet Retief, declaring, ‘DRUM’s no worse than a television set to most of us out here on the desolate farms: town and country activities are dished out to us on hot plates’.Footnote75 Ndimande’s comparison to television, which had fairly recently emerged as a consumer technology and would only be introduced in South Africa in 1976, indicates a perception of Drum as an extremely novel technology, capable of transmitting an aural and dynamic visual experience.Footnote76 Therefore, while Drum’s focus may have been predominantly urban, the magazine produced a reading public, from all over the country, ensconced in the world of jazz, drink, dancing and danger.

In addition, to readers beyond the city, Drum also provided access to city nightlife to its urban readers who did not want to, or could not afford to, go out at night. Some readers even began to change the way they spent their evenings. In 1954 Teddy Lechoano from Bloemfontein reported, ‘[u]ntil I came across DRUM I was “Captain Midnight”. But now I buy DRUM as soon as it comes out and return home early every evening to read it’.Footnote77 A similar case was described by a reader in 1957, and traces of a broader nighttime reading culture can be found scattered throughout the magazine.Footnote78 Rather than go out and experience nightlife first-hand, these readers chose to stay in and participate in it through Drum. Moreover, curfew legislation here meant that township residents could not travel between areas at night. Residents of Alexandra in the north of Johannesburg could not travel to Orlando or Sophiatown in the west, and vice versa. Yet in its pages, Drum allowed readers to move between the nighttime worlds of the different townships within a single edition of the magazine, while also providing an opportunity to experience nightlife in the central city itself.

Furthermore, Drum’s regular accounts of various nightly activities occurring outside South Africa, as in , allowed its readers – most of whom were precluded from leaving the country by apartheid and the cost of such an endeavour – a chance to experience this nightlife.Footnote79 In one such case, a May 1953 article entitled ‘Meet Me at the Sugar Hill’ detailed the goings-on inside a London bar and nightclub, complete with photographs:

In the main for the coloured community [in London] dancing remains a favourite pastime. Maybe it is the natural love for rhythm and music, the joy of expressing ourselves without inhibition and staff ceremony which makes the Sugar Hill Club one of the favourite spots in town. … Around about seven-thirty night life begins. The more energetic go below to the dance floor which throbs with activity until midnight.Footnote80

Drum’s explorations of the international night scene provided the opportunity for Drum’s writers to express both difference and similarity, fulfilling the travel writers’ mission of characterising strange territories but also situating and orientating black South Africans within a greater world of black nighttime expression. Stanlake Samkange’s 1958 article on Harlem stands out most prominently in this regard. At times, Samkange described the differences he noticed between the nocturnal scene in Harlem and South Africa:

Although our cities in Africa may have a lot of people in the streets early in the evening, they become fewer as the night wears out. Not so with Harlem. You see as many people walking talking and loitering in the streets at 3 a.m. as you see at 6 p.m … There are pubs and restaurants open the whole night … They get crowded with patrons interested in wine, women and song.Footnote82

Here, Drum performatively addressed a global nocturnal public that was united, not necessarily in the way they spent their days, but in what they sought at night. This is encapsulated in Drum’s photo caption of the Brazil dance hall: ‘[i]n Brazil, like elsewhere, the music rises as the sun goes down. The day’s woes are forgotten’.Footnote86 Drum ensconced its readers within this networked urban nighttime world and in doing so challenged the key tenants of apartheid, which presented an image of the localised, tribalised, rural African cut off from modernity. Scholars have examined Drum’s transnationalism, particularly involving America, as an attempt to assert and enact modernity.Footnote87 What this scholarship does not consider, however, is that this transnational coverage largely focused on the international night, filled with black people participating in a vivacious nightlife. Mutual engagement with the night, vicariously or in person, was an idiom Drum placed at the centre of its modernity.

Drum transported its readers to a particular place, the urban night, and made it possible for them to participate in manifold nighttime activities through reading articles, listening to records, looking at photographs and writing letters, producing in them a sense of ‘being modern’. The opportunity for travel Drum provided prompted John Nkosi from Silverton, Pretoria, to write to the magazine with glowing praise in 1958 (just after the launch of the Sputnik spacecraft): ‘DRUM should be called Sputnik. If you are a reader of DRUM you feel as though you were in a Sputnik – not going to the moon, but just taking a cruise around the wonderful world’.Footnote88 Similarly, Motsisi has described Drum as replacing the passport most residents of Sophiatown were denied.Footnote89 The longing to travel and the substitute Drum provided is aptly described by Themba in his preamble to Samkange’s Harlem article:

To me lying in my bed dreaming, Harlem has seemed like the other side of the moon: the place I’ll never see … We wish we could be with you in New York, Stanlake Bo. But we can’t. Tough. But, folks, read his letter home. Then shut your eyes, we can dream, can’t we?Footnote90

Conclusion: ‘When the lights are low’

The night as a frame of historical analysis has not seen much examination in South African historiography. However, the night was a fundamental component of historical action within the territory, both as a symbol and experience to think with and as a determining field which facilitated, constrained and gave meaning to what occurred therein. Within the particular frame of the 1950s, and probably beyond, the night – produced through racialised legislation, uneven service provision, awareness of global approaches to and engagements with the night, alongside local conceptions of the night and nighttime activity on the ground – was variably involved in the performance, restriction and contestation of black urban identity and modernity.

Drum provides an entry point into the world of the South African night and testifies to the rich potential for study therein. The magazine offers an opportunity to examine how its writers, and more hesitantly its readers, conceived, and conceived of, the night. Drum centred the night as the site of what it called ‘real life’, depicting a vibrant social and community life by night in South Africa’s black townships when urban residents came together within their neighbourhoods after the end of the working day. This gestures towards a particular relationship to time. In contrast to the temporal rhythm regularised by industrialisation and segregation, Drum inverted the dichotomy of an active day and an inactive night, placing the night as the site of value, where an alternative reality to that of the day was possible and where one could truly feel alive.

Here, Drum serves as a source for how people lived within legal and material structures, carving out a life inside them notwithstanding their suppressive attempts and effects. Despite segregationist legislation and deficient lighting provision, black urban residents actively made use of the night. These nighttime activities consciously and unconsciously subverted apartheid’s prescribed temporal order and enacted black modernity.

However, more than this, Drum itself was an integral part of this subversion, presenting and providing an alternative night space to that of the legislative night that the state was attempting to construct. Drum performed the night and black nighttime activity, producing two effects. First, Drum testified to the existence of urban Africans’ life by night. Drum held up black urban residents’ engagement with the night as a performance of their modernity, in response to the state’s denial of this. By writing about the night and the nighttime activities of black people as ‘real life’, Drum asserted black urban residents as modern urban citizens, not just articles of labour. However, Drum juxtaposed its descriptions of the vibrant night with reporting and depictions of crime, laying bare the dangers and fears of living life by night and critiquing the state’s uneven provision of lighting infrastructure and policing which produced this condition.

Second, Drum offered its readers a chance to explore the night through its pages, allowing for the extension of nighttime activity beyond immediate physical engagement and circumventing the legislated curbs on black mobility. This allowed readers across South Africa to experience and collectively participate in the country’s urban nightlife alongside the night beyond local borders. Additionally, in placing South African nights side by side with global nighttime activity, Drum enabled its international readers to engage in South African nightlife and situated South African nights within a shared space with those around the world – in a global black modernity linked to nighttime culture.

In 1962, Mphahlele wrote of black South African writers of the time, ‘[t]hese South African writers are fashioning an urban literature on terms that are unacceptable to the white ruling class … They keep on digging their feet into an urban culture of their own making’.Footnote91 Drum’s authors’ use of the night as symbol and setting was a large part of this process, taking the night as a key site for the production of and participation in the self-defined urban culture Mphahlele described. The night was a crucial terrain in and against which the struggle between black South Africans and ‘the white ruling class’ over modernity and urban identity unfolded. While in the 1950s the apartheid state sought to constrain black people’s activity at night, as a contributive part of performing Africans’ supposed incongruity with city life and separation from modernity, the nighttime activities of black urban residents – displayed within Drum’s pages – stood in direct subversion of this. Further, Drum itself bypassed curfew legislation and restrictions on mobility, facilitating vicarious engagement with the night in South Africa and other sites around the world. In all of this, Drum involved its readers in a transnational project of African urban modernity symbolised, expressed and experienced through the night.

Faculty of History, University of Cambridge, West Road, Cambridge CB3 9EF, UK. Email: [email protected]

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8652-9663

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Ruth Watson for her generous support and assistance throughout the writing of this article. Additionally, I would like to thank Cambridge University Library for allowing me access to their Drum collection, and Bailey’s African History Archive and Africa Media Online for providing the photographs for publication. Thank you also to Liam Michael Plimmer and Mark Fleishman, who acted as readers and sounding boards during the writing process.

Notes

1 See, for example, T. Matshikiza, ‘Talking Trumpet: Elijah Nkwanyana’, Drum, August 1953, pp. 44–5; T. Matshikiza, ‘Disc-ussing’, Drum, August 1953, p. 45; T. Matshikiza, ‘Disc-ussing’, Drum, March 1954; T. Matshikiza, ‘What They Say about Dolly’, Drum, October 1954, pp. 15–17; T. Matshikiza, ‘Gramo Go Round’, Drum, May 1955, p. 73; T. Matshikiza, ‘Gramo Go Round’, Drum, December 1955, p. 79; T. Matshikiza, ‘Shantytown in City Hall!’, Drum, August 1956, pp. 17–20; B. Modisane, ‘Disc Time’, Drum, July 1958, p. 81; B. Modisane, ‘Disc Time’, Drum, August 1958, p. 83; B. Modisane, ‘Disc Time’, Drum, February 1959, p. 79; B. Dyantyi, ‘Dollar Brand’, Drum, December 1959, pp. 26–9. Access to these and all Drum articles cited in this article was provided through Cambridge University Libraries.

2 National Archives and Records Service of South Africa, NTS (Secretary of Native Affairs), 1949–1958, 4546, 866/313, ‘Curfew’; N. Nakasa, ‘Criminals Without Crime’, Drum, April 1959, p. 25; E. Mphahlele, Down Second Avenue (London, Faber and Faber, 1959), p. 45.

3 G. Magwaza, ‘Talk o’ the Rand’, Drum, September 1956, p. 15; A. Sampson, Drum: A Venture into the New Africa (Collins, London, 1956), p. 33.

4 T. Huddleston, Naught for your Comfort (London, Collins, 1956), pp. 51–2; C. Guldimann, ‘“A Symbol of the New African”: Drum Magazine, Popular Culture and the Formation of Black Urban Subjectivity in 1950s South Africa’ (PhD thesis, Queen Mary University of London, 2003), pp. 7, 53–4.

5 M. Beaumont, Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London (London, Verso, 2015), pp. 41–2.

6 M. Chapman, The Drum Decade: Stories from the 1950s (Pietermaritzburg, University of Natal Press, 1989), p. 194.

7 Ibid., pp. vii–viii; 186–7; Guldimann, ‘A Symbol of the New African’, pp. 6–7, 184, 283–4; P. Gready, ‘The Sophiatown Writers of the Fifties: The Unreal Reality of their World’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 16, 1 (1990), pp. 144–6; D. Driver, ‘Drum Magazine (1951–59) and the Spatial Configurations of Gender’, in K. Darian-Smith, L. Gunner and S. Nuttall (eds), Text, Theory, Space: Land, Literature and History in South Africa and Australia (London, Routledge, 1996), pp. 231–42; R. Johnson, ‘“The Girl About Town”: Discussions of Modernity and Female Youth in Drum Magazine, 1951–1970’, Social Dynamics, 35, 1 (2009), pp. 36–50.

8 D. Maughan-Brown, ‘The Anthology as Reliquary?’, Current Writing, 1, 1 (1989), p. 12.

9 Gready, ‘The Sophiatown Writers of the Fifties’, pp. 141, 148.

10 D. Goodhew, ‘Working-Class Respectability: The Example of the Western Areas of Johannesburg, 1930–55’, Journal of African History, 41 (2000), pp. 241–66; L.M. Thomas, ‘The Modern Girl and Racial Respectability in 1930s South Africa’, Journal of African History, 47, 3 (2006), p. 467.

11 Goodhew, ‘Working-Class Respectability’.

12 Driver, ‘Drum Magazine (1951–59)’, pp. 231, 238; Guldimann, ‘A Symbol of the New African’, pp. 275–7; Johnson, ‘The Girl About Town’.

13 Sampson, Drum, p. 30.

14 Johnson, ‘The Girl About Town’, p. 42.

15 C. Themba, ‘Dolly and Her Men’, Drum, January 1957, pp. 37–45.

16 B. Modisane, Blame Me on History (London, Thames and Hudson, 1963), pp. 147–8, 275, 279; L. Nkosi, Home and Exile (London, Longmans, 1965), p. 11; Gready, ‘The Sophiatown Writers of the Fifties’, pp. 144, 151. Yellow referred to ‘yellow press’, a description of print media that published poorly researched news, attempting to increase sales by substituting substance for scandal.

17 Sampson, Drum, pp. 15–32; Chapman, The Drum Decade, pp. 186–94; Guldimann, ‘A Symbol of the New African’, pp. 45–7; Gready, ‘The Sophiatown Writers of the Fifties’, pp. 143–4.

18 P. Geschiere, B. Meyer and P. Pels, ‘Introduction’, in P. Geschiere, B. Meyer and P. Pels (eds), Readings in Modernity in Africa (Oxford, James Currey, 2008), pp. 1–3; H. Lefebvre, Introduction to Modernity, trans. J. Moore (London and New York, NY, Verso, 1995), pp. 178–81, 185; D. Attwell, Rewriting Modernity: Studies in Black South African Literary History (Athens, Ohio University Press, 2006), pp. 3-4, 22–3.

19 E. Hunter, ‘Modernity, Print Media, and the Middle Class in Colonial East Africa’, in C. Dejung, D. Motadel and J. Osterhammel (eds), The Global Bourgeoisie: The Rise of the Middle Classes in the Age of Empire (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2019), pp. 111–12; 117–18.

20 Drum, September 1954, p. 15; ‘Blackest Magic’, Drum, September 1956, pp. 43–51; Drum, February 1959, p. 69; Drum, December 1961, p. 82; Nkosi, Home and Exile, p. 10.

21 W. Straw, ‘Gathering up the Social: Nightlife Columns in the African-American Press’, Ethnologies, 44, 1 (2022), pp. 41–59.

22 ‘Negro Notes from U.S.A.’, Drum, October 1951, p. 10.

23 ‘Negro Notes from U.S.A.’, Drum, November 1951, p. 13; ‘Negro Notes from U.S.A.’, Drum, February 1952, p. 11; ‘At the Dance Hall’, Drum, September 1958, p. 39; ‘Meet Me at the Sugar Hill’, Drum, May 1953, p. 25.

24 Drum, June 1958, p. 50; see also Drum, August 1958, p. 80; Drum, March 1959, p. 7.

25 Sampson, Drum, p. 20.

26 N.S. Ndebele, ‘The Rediscovery of the Ordinary: Some New Writings in South Africa’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 12, 2 (1986), pp. 144–50, 156.

27 For some examples see, ‘Inside Johannesburg’s Underworld’, Drum, October 1951, p. 6; ‘High Life in Cape Town’, Drum, May 1952, pp. 20–1; ‘Shebeens I have Known’, Drum, November 1952, pp. 6–7; ‘The History of “Defiance”’, Drum, October 1952, pp. 12–15; J.A. Maimane, ‘Will He Beat Jake?’, Drum, May 1953 pp. 28–9; ‘Not too Late to Learn’, Drum, June 1953, pp. 24–5; ‘Gipsy Opera Storms Cape’, Drum, October 1953, pp. 36–7; J.A. Maimane, ‘Boxing goes to the Dance’, Drum, August 1955, pp. 22–3; C. Themba, ‘Let the People Drink’, March Drum, March 1956, pp. 53–7; ‘Cape Moffie Drag’, Drum, January 1959, pp. 60–1; ‘Smash-Hit’, Drum, March 1959, pp. 24–7; G.R. Naidoo, ‘Murder at Midnight’, Drum, April 1959, pp. 68–71; M. Morel, ‘Girl about Town’, Drum, June 1959, pp. 19–21; ‘Phata Phata’, Drum, January 1960, p. 33.

28 E. Mphahlele, ‘Blind Alley’, Drum, September 1953, pp. 32–4; C. Themba, ‘The Nice Time Girl’, Drum, May 1954, n.p.; D. Ngcobo, ‘Never Too Late for Love!’, Drum (West African), September 1954, n.p.; M. Manqupu, ‘Love Comes Deadly’, Drum, January 1955, pp. 40–1, 51; B. Dlodlo, ‘Kickido’, Drum, October 1956, pp. 47–51; A. Mogale, ‘Crime for Sale’, Drum, January 1953, pp. 32–3.

29 M. Chapman, ‘Can Themba, Storyteller and Journalist of the 1950s’, English in Africa, 16, 2 (1989), p. 27; ‘Mr Drum’s Letter’, Drum, October 1956, p. 6.

30 ‘Masterpiece in Bronze: Isaac Makau’, Drum, November 1955, p. 61.

31 C. Themba, ‘Talk on the Rand: Loiterers Galore’, Drum, April 1958, p. 17.

32 Themba, ‘Let the People Drink’, pp. 53–7.

33 Gready, ‘The Sophiatown Writers of the Fifties’, p. 145. For an example, see, C. Motsisi, ‘On the Beat’, Drum, July 1958, p. 75.

34 Nkosi, Home and Exile, p. 15.

35 ‘Speak up, Man!’, Drum, December 1959, pp. 72–3.

36 ‘£50 Winner of Short Story Contest’, Drum, April 1953, p. 21.

37 Manqupu, ‘Love Comes Deadly’, p. 40.

38 S. Samkange, ‘Mr Drum Visits Harlem’, Drum, March 1958, p. 21.

39 M. Samuelson, ‘The Urban Palimpsest: Re‐Presenting Sophiatown’, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 44, 1 (2008), pp. 65–6.

40 Driver, ‘Drum Magazine (1951–59), pp. 231–42; Johnson, ‘The Girl About Town’.

41 Themba, ‘Let the People Drink’, p. 54.

42 For example, see Manqupu, ‘Love Comes Deadly’, p. 41; Themba, ‘The Nice Time Girl’; Dlodlo, ‘Kickido’; F. Hawkins, ‘Too Late to Love!’, Drum, October 1955, pp. 46–51; C. Themba, ‘Marta’, Drum, July 1956, pp. 41–5; C. Themba, ‘Dolly’, Drum, March 1957, pp. 59–63.

43 For example, Themba, ‘Dolly and her Men’; Matshikiza, ‘What They Say about Dolly’, pp. 15–17; ‘Drum Picture Gallery: Miss Dolly Rathebe’, Drum, March 1956, pp. 40–1.

44 C. Motsisi, ‘On the Beat’, Drum, March 1959, p. 56; C. Motsisi, ‘On the Beat’, Drum, May 1959, p. 59; Dlodlo, ‘Kickido’.

45 Driver, ‘Drum Magazine (1951–59), p. 238; Johnson, ‘The Girl About Town’, p. 39.

46 Manqupu, ‘Love Comes Deadly’, p. 41.

47 ‘Durban Exposed: City with Two Faces’, Drum, July 1952, pp. 13–17.

48 ‘Clean up the Reef’, Drum, March 1953, pp. 11–13; ‘MR DRUM’S LETTER’, Drum, October 1957, p. 6; G. Magwaza, ‘‘Talk o’ the Town’, Drum, September 1958, p. 15; ‘Organised Gangsterism’, Drum, December 1955, p. 33; Gready, ‘The Sophiatown Writers of the Fifties’, p. 154.

49 Manqupu, ‘Love Comes Deadly’, p. 40; ‘Organised Gangsterism’, p. 33; ‘Terror Township’, Drum, May 1953, pp. 39–41; ‘Alexandra’s Terror’, Drum, August 1955, pp. 59–61; ‘Death in the Dark City’, Drum, April 1956, p. 27.

50 ‘The Globe Gang’, Drum, April 1954, n.p.; for other examples, see ‘Terror Township’ and ‘Organised Gangsterism’, pp. 29–33.

51 ‘The Torch Gang’, Drum, April 1955, p. 29.

52 ‘Terror in the Trains!’, Drum, October 1957, p. 24.

53 Ibid., p. 22.

54 Drum, November 1956, p. 26.

55 Drum, December 1956, p. 18.

56 ‘MR DRUM’S LETTER’, Drum, October 1957, p. 6.

57 Magwaza, ‘Talk o’ the Town’, p. 15.

58 Morel, ‘Girl about Town’, p. 21.

59 C. Themba, ‘Crepuscule’, in D. Stuart and R. Holland (eds), The Will to Die (London, Heinemann, 1972), p. 5.

60 Gready, ‘The Sophiatown Writers of the Fifties’, p. 140.

61 ‘Those Gay Cape Parties’, Drum, October 1960, p. 47.

62 For the concept of ‘publics’, see K. Barber, The Anthropology of Texts, Persons and Publics: Oral and Written Culture in Africa and Beyond (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 139.

63 ‘MR DRUM’S LETTER’, Drum, September 1958, p. 6.

64 R. Bridges, ‘Exploration and Travel outside Europe (1720–1914)’, in P. Hulme and T. Youngs (eds), The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 53.

65 Ibid., pp. 53–69; M.L. Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (New York and London, Routledge, 1992).

66 R. Jones, At the Crossroads: Nigerian Travel Writing and Literary Culture in Yoruba and English (Woodbridge, Boydell and Brewer, 2019). pp. 2, 7–8.

67 Ibid., pp. 58, 78–85, 88–90.

68 For example, see T. Matshikiza, ‘Shantytown in City Hall’, Drum, August 1956, pp. 17–18.

69 ‘Clean up the Reef’, p. 13. See also ‘Durban Exposed’ and ‘The Globe Gang’.

70 Themba, ‘Let the People Drink’, pp. 53–7; Chapman, ‘Can Themba, Storyteller and Journalist of the 1950s’, p. 24.

71 For example, see Maimane, ‘Will He Beat Jake?’, pp. 28–9; Morel, ‘Girl about Town’, pp. 19-21.

72 S. David, ‘Popular Culture in South Africa: The Limits of Black Identity in Drum Magazine’ (PhD thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, 2000), p. 67.

73 For examples, see T. Matshikiza, ‘Gramo Go Round’, Drum, May 1955, p. 73; B. Modisane, ‘Disc Time’, Drum, September 1958, p. 81.

74 ‘Write to Drum’, Drum, February 1956, pp. 11–13; ‘Write to Drum’, Drum, April 1956, p. 11; ‘Write to Drum’, Drum, December 1957, p. 11; ‘Speak up, Man’, Drum, May 1958, p. 10; ‘Speak up, Man’, Drum, January 1959, p. 13; ‘Speak up, Man’, Drum, February 1959, p. 11; ‘Speak up, Man’, Drum, March 1959, p. 13.

75 ‘Letters to the Editor’, Drum, August 1953, p. 42.

76 R. Nixon, ‘The Devil in the Black Box: Ethnic Nationalism, Cultural Imperialism, and the Outlawing of TV Under Apartheid’, The Societies of Southern Africa in the 19th and 20th Century, Collected Seminar Papers, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, 45 (1993), pp. 120–37.

77 ‘Write to Drum’, Drum, November 1954, pp. 6, 12.

78 ‘Write to Drum!’, Drum, March 1957, p. 11; ‘Write to Drum’, Drum, February 1954, n.p.; ‘Write to Drum!’, Drum, January 1955, p. 9.

79 For examples, see ‘Go! Go! Go! “Big Jay” Sends Jazz Fans Crazy!’, Drum, May 1953, pp. 17–19; ‘Negro Shows Sweep the World’, Drum, August 1953, pp. 6–7; ‘All Aboard the Jazz Train’, Drum, September 1955, pp. 42–3; ‘Masterpiece in Bronze: Rock ‘Em Hampton’, Drum, March 1957, pp. 37–9; ‘How Patterson Put Ingo on Ice’, Drum, August 1959, pp. 32–3; ‘Miriam in New York’, Drum, April 1960, pp. 26–7.

80 ‘Meet Me at the Sugar Hill’, p. 25.

81 ‘It’s the Newest Craze’, Drum, June 1958, p. 51; ‘At the Dance Hall’, p. 39.

82 Samkange, ‘Mr Drum Visits Harlem’, p. 21.

83 Ibid.

84 ‘Speak up, Man!’, Drum, April 1958, p. 9.

85 ‘Pen Pal Club’, Drum, December 1951, p. 39; ‘Write to Drum’, Drum, February 1955, p. 6; ‘Pen Pal Pix’, Drum, June 1958, p. 81; ‘Pen Pal Pix’, Drum, September 1959, p. 91; ‘Speak up, Man!’, Drum, July 1958, p. 13; ‘Speak up, Man!’, Drum, September 1958, p. 13; ‘Speak up, Man!’, Drum, August 1959, pp. 87–9; ‘Speak up, Man!’, Drum, October 1959, p. 85.

86 ‘At the Dance Hall’, p. 39.

87 Guldimann, ‘A Symbol of the New African’; U. Hannerz, ‘Sophiatown: The View from Afar’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 20, 2 (1994), pp. 181–93; T. Odhiambo, ‘Inventing Africa in the Twentieth Century: Cultural Imagination, Politics and Transnationalism in Drum Magazine’, African Studies, 65, 2 (2006), pp. 157–74; M. Fenwick, ‘“Tough Guy, Eh?”: The Gangster‐Figure in Drum’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 22, 4 (1996), pp. 617–32; R. Nixon, Homelands Harlem and Hollywood: South African Culture and the World Beyond (London and New York, Routledge, 1994).

88 ‘Speak up Man!’, Drum, July 1958, p. 11.

89 Guldimann, ‘A Symbol of the New African’, p. 5.

90 ‘MR DRUM’S LETTER’, Drum, April 1958, p. 6.

91 E. Mphahlele, The African Image (London, Faber and Faber, 1962), p. 192.