Abstract

In August 1970, four senior African National Congress members – Flag Boshielo, Castro Dolo, Victor Ndaba and Bob Zulu – vanished during their clandestine return to South Africa from exile in Zambia. It was thought that they had met a tragic end while crossing the Zambezi River into the Eastern Caprivi of South West Africa (now the Zambezi Region of Namibia). After 1994, renewed attempts to establish the men’s fate were hampered by a paucity of archival data, the unwillingness of witnesses to provide information and the passage of time. Recent research in the Eastern Caprivi brought new information to light when local communities were found to be familiar with a story about ‘foreign fighters’ who crossed the Zambezi River. The strangers were betrayed to the South African police and drawn into an ambush. Research in the National Archives of Namibia also yielded new information. By piecing together local narratives with archival material and interviews with former members of Umkhonto we Sizwe and the South African Police, this article chronicles the odyssey and fate of Boshielo and his companions, although some questions remain. Unfortunately, in South Africa, the search for those who disappeared during the struggle against white minority rule is by no means complete. This article demonstrates the value of extending research beyond South African borders when information and knowledge are scattered across countries, institutions, communities and individuals.

Introduction

In August 1970, four senior African National Congress (ANC) members – Flag Boshielo, Castro Dolo, Victor Ndaba and Bob Zulu – vanished during their clandestine return to South Africa from exile in Zambia. It was thought that they had met an untimely end when crossing the Zambezi River into the Eastern Caprivi of South West Africa.Footnote1 Until recently, what little was known of the men’s journey had been provided by ANC members upon their return from exile and their knowledge ended at the point where the four men crossed the Zambezi. Of late, new information has surfaced. Villagers of the Eastern Caprivi floodplains told me a story about ‘foreign fighters’ who came across the river many years ago and that the strangers had been betrayed to the South African police and led into an ambush.Footnote2

These events took place ten years after the banning of the ANC and detention of the organisation’s most senior leaders. Many of the organisation’s members and sympathisers had left the country and found their way to Dar es Salaam, where the ANC had established an office. The ANC was thus ‘transformed into an organisation in exile’.Footnote3 Domestically, resistance against the white minority government continued, as did the regime’s repression of dissent. When the struggle finally ended in 1990, up to 2,000 people had disappeared.Footnote4 Tragically, to this day many are still unaccounted for. Even when there is a high probability that they are deceased, a formal pronouncement to this effect is impossible in the absence of conclusive proof. Thus, a Missing Persons Task Team was established in 2005 to investigate unresolved cases.Footnote5 The case of Boshielo and his companions is one of them.

Over time, it seems that the uncertainty regarding the men’s fate has grown, rather than diminished. An early and straightforward version held that Boshielo and his comrades were betrayed and were ambushed and killed by South African security forces after crossing the Zambezi River.Footnote6 In later years, as the disastrous outcome of the Boshielo mission was commemorated in memoirs and histories of the anti-apartheid struggle, variations on this theme emerged and were reproduced. For instance, it was said that Boshielo had been wounded, captured and tortured, and subsequently killed or locked away in a South African prison. Other versions speculated that one of his companions might have escaped.Footnote7 Discrepancies also emerged regarding location and time. Some claimed that the men crossed into Rhodesia and were killed or arrested there, or even that Boshielo disappeared during the Wankie campaign of 1967.Footnote8 A booklet printed for the 2005 Luthuli Order awards ceremony erroneously stated that the men disappeared in 1972.Footnote9

This article chronicles the odyssey of Flag Boshielo, Castro Dolo, Victor Ndaba and Bob Zulu.Footnote10 Its objective is to dispel some of the speculation and rumours surrounding the men’s disappearance, and to present newly uncovered information that provides a more complete picture of their fate. After a methodological note, it introduces the four men, draws on existing literature to provide a historical context and traces their journey. Finally, the aftermath of the Boshielo mission and remaining questions are discussed.

Methodological Note

Past research points to the advantage of multiple methodological approaches in the search for the missing. Modern forensics have become invaluable, while oral testimonies can provide crucial contextual information, which may in turn be substantiated and expanded by archival records and vice versa. In South Africa, researchers have long endorsed a focus on local knowledge and histories, not only in order to revise or reject dominant interpretations of the past, but also to aid in the search for those who went missing during the struggle. Local knowledge has shed light on missing persons’ lives, their disappearance, place of death or the location of a grave.Footnote11 However, research has largely been limited to cases of persons who disappeared within South Africa’s borders. Where information and knowledge are scattered across countries, institutions, communities and individuals, much work remains to be done.

In the case of Boshielo and his comrades, interviews with local villagers were instrumental in piecing together what befell the men after they crossed the Zambezi. It turned out to be a well-known story.Footnote12 In the Eastern Caprivi, largely a rural region, unusual events and passing strangers do not go unnoticed and are discussed and speculated upon at length. Maurice Halbwachs, in his seminal work On Collective Memory, notes that collective memories emerge when community members pool their fragments of knowledge to construct a fitting narrative about an event. Such narratives represent the accumulation and preservation of communal knowledge and experiences. Importantly, they are passed on through time.Footnote13 Indeed, over the years, the story of Boshielo and his men was told and retold in the villages and even young people know about the ambush of the foreign fighters. This demonstrates the potential reward of conducting research in localities where communities or individuals may have knowledge regarding events that took place in their neighbourhood, even if these happened in a distant past. The value of extending research beyond South African borders was further underscored by an important discovery in the National Archives of Namibia. An inquest dossier was found that contained reports by South African state employees – police officers, a doctor and a magistrate – who provided details of the ultimate fate of the men.

Further information was obtained within South Africa from interviews with former Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) members who knew Boshielo and his men and were familiar with the circumstances of Boshielo’s mission. In addition, interviews were held with five former members of the South African Police Security Branch (SAP-S) who saw duty in Katima Mulilo, the administrative seat of the Eastern Caprivi.Footnote14

The veracity of sources could not always be established. Memories fail, people’s accounts are incomplete or biased and archival documents and official records cannot be taken as irrefutable evidence of past events. This points to the constructed nature of historical narratives. As stories that can be told in multiple ways, they are essentially unstable and do not lead to a final, unambiguous and accurate account of ‘what really happened’. Instead, I offer my interpretation of the newly uncovered information and I remain mindful of Thomas Keenan’s warning to ‘respect the fragmentary nature of what can be told, and not to give in to the notion that justice, or mourning, or narration, can be concluded once and for all’.Footnote15

Introducing Boshielo and his Companions

Of the four men, Marutle Flag Boshielo was the most senior ANC member. He was born in Phokwane in Sekhukhuneland in 1920 and was also known by the name Mokgomane, designating a male member of the royal family or a councillor. As a young man, Boshielo found employment in Johannesburg, where he became a close friend and mentor of Elias Motsoaledi and John Nkadimeng. He joined the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), and later the ANC, and rose to prominence in both organisations.Footnote16 In 1952, during the Defiance Campaign, Nelson Mandela was arrested along with Flag Boshielo and in his memoirs remembered their ride in the prison vans, which ‘swayed to the rich voices of the defiers singing Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika’.Footnote17 Two years later, Boshielo became a founder of Sebatakgomo, a migrant worker organisation in Sekhukhuneland.Footnote18 In 1962 he went into exile and was among the first ANC members to arrive in Dar es Salaam, after which he was sent to the Soviet Union to be trained at the Institute of Social Sciences, also known as the International Lenin School.Footnote19 On his return to Tanzania in 1964, Boshielo was part of a group that set up Kongwa camp, some 400km from Dar es Salaam, where eventually between 400 and 500 ANC members in exile would be accommodated.Footnote20 At the time of his disappearance, Boshielo had become one of the most senior ranking members of the ANC, having been appointed to the ANC’s highest organ, the National Executive Council (NEC), and elected as Chief Political Commissar of MK.Footnote21

Boshielo was well-liked and respected among all ranks of the ANC and his appointment to the NEC has been partly ascribed to his tremendous popularity among the MK cadres.Footnote22 Several times through the years, when the ANC in exile found itself at a critical juncture, he proved to be a voice of reason and calm persuasion and his standing with rank-and-file guerrillas carried the day.Footnote23 Boshielo’s star was on the rise, which begs the question of why he undertook his perilous journey to South Africa. Part of the answer must be sought in his unwavering commitment to the cause. Testimonies to his character and dedication abound. For instance, John Nkadimeng remembered Boshielo as disciplined, keen to learn and evangelical in his political commitment.Footnote24

Like Boshielo, his companions were trained MK cadres and respected senior members of the ANC in exile. All three were listed in the so-called Terroriste Album, a compendium of photographs created by the SAP-S.Footnote25 Castro Dolo was the nom de guerre of Faldon Mzwonke, also known as Mcebisi Kokwane. He was 52 years old at the time of his disappearance. Along with Chris Hani, Archie Sibeko and James Tyeku, he was arrested in Cape Town in 1962 for distributing banned literature and he fled the country while on bail. Castro Dolo and Victor Ndaba were long-standing friends. They were both from Transkei and both were veterans of the Wankie campaign of 1967.Footnote26 For saving the lives of comrades during the campaign, Ndaba, also known as Theo Mkhalipi or Victor Dlamini, was honoured with the Special Medal for Bravery in gold in 2012.Footnote27 At the time of their disappearance Victor Ndaba was 48 years old. Finally, Bob Zulu was the youngest of the four. He was also known as Madiba and was a relative of Nelson Mandela. Bob Zulu had been involved in the Pondo revolt in 1960.Footnote28

Background

The ANC leadership in exile recognised from the start that effective resistance within South Africa would depend on mass mobilisation. Moreover, in order to generate robust domestic support, the ANC would need to demonstrate its strength and its capacity to hit the apartheid regime where it hurt. To achieve this, MK units would have to be trained and then infiltrated into South Africa, ideally with a senior strategist to coordinate political and military activity. However, until a secure infiltration route from Tanzania to South Africa had been established, trained MK members remained on hold at Kongwa.Footnote29 The forced wait created frustration among guerrillas living at the camp. Aggravated by poor living conditions, an atmosphere of suspicion and demoralisation took hold. There was a perception that MK leaders were not committed to finding a way home for the regular cadres – and were ‘living it up’ in Dar es Salaam.Footnote30

To make matters more complicated, the chances of finding a safe route back to South Africa were diminishing. The most straightforward route home led through Botswana, which had proven itself sympathetic to exiled resistance organisations. In the early days of the struggle, Botswana welcomed ANC members fleeing South Africa and assisted them on their onward journey.Footnote31 However, as an economic hostage to South Africa, Botswana was in a precarious position and under immense pressure to deny support to liberation movements. In 1966 President Seretse Khama declared that he would not ‘permit Botswana to be used as a base for the organisation or direction of violent activities directed against other states’.Footnote32 Thereafter, trespassers were arrested by the Botswana police and sent to prison or deported to Zambia.Footnote33 An alternative was to seek passage through Rhodesia. It led to the Wankie and Sipolilo campaigns of 1967 and 1968 respectively, when the ANC, together with the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), endeavoured to establish a route through Rhodesia with secure bases along the way – a ‘Ho Chi Minh Trail’ to South Africa.Footnote34 Both missions ended in disaster. The Wankie mission was discovered soon after the men entered Rhodesia and up to fifty men perished in skirmishes with the Rhodesian security forces. Similarly, the Sipolilo campaign cost many lives and failed to achieve its objective.

There were further consequences to the failed infiltration attempts. Eighteen men of the Wankie group, among them Chris Hani, escaped from Rhodesia to neighbouring Botswana. There, they were arrested, subsequently tried for illegally entering the country and importing weapons and ammunition and sentenced to imprisonment for up to three years, although the diplomatic efforts of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and the Zambian government facilitated their early release.Footnote35 Upon their return to Lusaka, Hani and his comrades found that the ANC high command had no interest in debriefing them, nor in drawing lessons from their experience.Footnote36 Disappointed and frustrated at not being heard, Hani and five others put their concerns and grievances into a document that became known as ‘The Hani Memorandum’ (1969). It was a sharp attack on the ANC leaders in exile, accusing them of a lack of vision and purposeful direction, stating in its first point that: ‘[t]here has never been an attempt to send the Leadership inside since the Rivonia Arrests’.Footnote37 The document declared that, instead of working to further the revolution at home, ANC leaders worked to advance their own careers and had become comfortable in their exile lives. Moreover, the memorandum claimed that MK used ‘extremely reactionary methods of punishment’ and listed cadres who had been subjected to criminal and inhuman treatment.Footnote38

Flag Boshielo was almost certainly in agreement with the concerns that were voiced in the memorandum. He was much perturbed by the disastrous results of the Wankie and Sipolilo campaigns, and it seems he lost belief in the commitment of the ANC leadership in exile. He had repeatedly voiced his disapproval over operational procedures and was especially galled by the stipends paid to leaders while conditions in the ANC training camps were so poor.Footnote39 He even considered resigning but a friend convinced him that this would be ‘tantamount to committing suicide’.Footnote40 Boshielo was certainly not the only one to be so demoralised. In fact, after Wankie a number of MK soldiers did desert.Footnote41 Boshielo stayed but became determined to return to South Africa, even though a route home by way of Rhodesia or Botswana now seemed impossible.

The Hani Memorandum appeared at a time when the ANC was planning the Morogoro Consultative Conference. The conference was held in late April 1969 and was attended by over seventy leaders and delegates. Its purpose was to set a forward course for the struggle. The Hani Memorandum convinced President Oliver Tambo that a crisis had developed in the ranks of the ANC and that festering issues and grievances needed to be urgently addressed. Flag Boshielo, as head of a commissariat of ten people in Lusaka, was tasked with extensive preparations for the conference, which included discussions, research papers and individual and collective written memoranda.Footnote42 One item on the Morogoro agenda was a proposal to open ANC membership in exile to all races. During the conference, Boshielo delivered a strong speech in support of this controversial issue. The respect that he enjoyed among the MK cadres, of whom a good number attended Morogoro as delegates, was certainly helpful in getting the motion adopted.Footnote43 It cemented Boshielo’s status as a respected leader of the ANC in exile.Footnote44 He survived a cutback of the NEC from over twenty to nine members, was appointed political commissar of MK and was awarded a seat on the newly formed Revolutionary Council.Footnote45

Morogoro concluded in a spirit of harmony but within months the ANC was faced with new challenges. In July 1969, Tanzania ordered Kongwa camp closed. Citing security concerns, all ANC MK cadres were to leave the country within fourteen days. Since alternative accommodation could not be found at such short notice, the men were evacuated to the USSR, where they were to stay for three years.Footnote46 Meanwhile, in Zambia MK cadres had been misbehaving in the streets of Lusaka, with allegations of drunkenness, brawling and rape made against them. As a result, also in July 1969, the Zambian government demanded that all MK military personnel be moved from Lusaka to a bush camp east of the city.Footnote47

South African authorities, meanwhile, were concerned at the role of Zambia as a base for exiled liberation movements. Not only did Zambia host the South African ANC, but also the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) from South West Africa, and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) from Rhodesia. All these organisations were looking for ways to send trained cadres home, and in South West Africa it fell to the South African Police (SAP) to prevent such infiltration. South West Africa’s long northern border made this a difficult task. In 1965 SWAPO had despatched four small teams of trained guerrillas from Zambia, one of which managed to reach Ongulumbashe in northern South West Africa and set up a secret training base. In 1966 they were discovered, after which South African forces attacked and destroyed the camp. Interrogation of captured combatants brought to light that one of the routes from Zambia to central South West Africa led through the Eastern Caprivi.Footnote48

In May 1967 the South African security apparatus was again put on high alert. The SAP intercepted Tobias Hainyeko, a high-ranking commander of the South West African Liberation Army (SWALA), while he was travelling on the Zambezi River transport barge.Footnote49 In the resulting skirmish Hainyeko was shot and killed and two police officers were seriously wounded.Footnote50 South African military analysts observed that, due to its location adjacent to independent Zambia, the Eastern Caprivi offered a plausible infiltration route to either South Africa or South West Africa. The region was flagged as a strategically vulnerable territory, or South Africa’s ‘Achilles heel’, and the analysts recommended deployment of adequate patrols in order to safeguard against infiltration from the north.Footnote51 This was easier said than done. The UN mandate prohibited South Africa from deploying a military force in South West Africa, and the task was beyond the scope of the handful of SAP officers trained to combat crime and maintain law and order. Therefore, a training program was initiated to establish police counter-insurgency (TIN) units.Footnote52 Upon deployment in the Eastern Caprivi, their task was to patrol and guard the land and river borders with neighbouring Zambia and Botswana. Furthermore, in 1967 the Security Branch (SAP-S) deployed the specialised Counter-Terrorist Interrogation Unit.Footnote53 Their main task was to obtain intelligence, and they enlisted informants within the Eastern Caprivi and in Zambia. Aided by locally recruited policemen, the SAP-S raided villages to search for and arrest ‘subversive elements’, sometimes transporting them to South Africa for interrogation in the Kompol building in Pretoria.Footnote54 Suspected activists were singled out for frequent visits, while their families were harassed and interrogated on a regular basis. Many fled to Zambia, and in 1968 police brutality and repression induced entire villages to seek safety in neighbouring Zambia and Botswana.Footnote55

Preparations

Boshielo may have been unaware of the extent to which South Africa had recently expanded its counter-insurgency effort, but the danger of a journey back home was never in doubt. A first hurdle was thus to obtain permission from the ANC high command. Whether four senior men should be permitted to undertake such a perilous mission was debated at a meeting of members of the military HQ and of the Revolutionary Council in March 1970. Boshielo, Castro Dolo and Victor Ndaba were present, as well as Oliver Tambo, Lambert Moloi and Thomas Nkobi.Footnote56 Those in favour argued that Boshielo’s plans conformed to the guidelines recently adopted at Morogoro, which demanded ‘in the first place the maximum mobilisation of the African people as a dispossessed and racially oppressed nation’.Footnote57 To achieve this, they argued, they had to take the struggle to South Africa. Should Boshielo succeed, it would be a significant step forward in re-establishing ANC political leadership inside South Africa. Tambo, however, was against the plan. He was averse to another hazardous mission when Wankie and Sipolilo had been so unsuccessful. In his opinion the mission was also unnecessary, and he referred to secret plans that would achieve the same objective in the long run. Nevertheless, the reluctance of Tanzania and Zambia to continue to host liberation movements had to be considered. Adding to ‘demoralising conditions of defection, provocation and degeneration’, large numbers of MK members had already been moved from Kongwa to the Soviet Union.Footnote58 Tambo conceded that ‘the situation in Lusaka was likely to do more rather than less harm to our organisation and the danger of losing more of our men into it was a real one’.Footnote59 Therefore, on condition that adequate preparations be made, so that the mission should not be another suicidal ‘leap in the dark’, Tambo agreed to Boshielo’s proposal.Footnote60

Planning could now start, and participants for the mission were selected. To avoid detection, Boshielo aimed to keep the group small. It was finally narrowed down to four persons, although several others had been invited, among them Chris Hani and Fanele Mbali.Footnote61 Funding, weapons and ammunition also had to be procured, which proved to be a challenge and frustrated the original plan to leave in May 1970.Footnote62 Finally the men had to plan their route. They settled on one that had not been tried before. From Lusaka, they would make their way south-west to the Zambezi River, where they would cross into the Eastern Caprivi of South West Africa. Here started the most perilous part of the journey; traversing a short distance of South African held territory before crossing the Chobe River into Botswana.Footnote63 As had become clear during the Wankie campaign, in Botswana the danger was not over and the men faced arrest and imprisonment when caught. From the Chobe River they had to travel another 500 km to Francistown, where the ANC had an office and assistance for their return to South Africa might be arranged.

The men were aware that Lusaka was ‘infested’ with informers, and that ‘comrades had developed the habit of talking about anything and everything they saw, observed or heard of’.Footnote64 Oliver Tambo had also expressed his concern at the possibility of leaks, therefore the men prepared their mission in utmost secrecy. At the bush camp east of Lusaka they kept apart from others while making their preparations, and they did not inform anyone of their exact plans. The appointed day of departure was known only to Boshielo, who said he would communicate it person to person at the very last moment. He kept a black goat at his camp and announced that the goat’s disappearance would signal that he and his companions had left on their mission.Footnote65 Indeed, when the men left, they did so quietly and without fanfare. Archie Sibeko, returning from a trip to Lusaka, found that Castro Dolo had gone missing and that Flag Boshielo and two others had disappeared too. He suspected that ‘Castro could not resist the temptation of crossing the river and heading for home, however dangerous it was’.Footnote66

Before heading south, the men first stopped at the house of Ray and Jack Simons in Lusaka, where they conducted a traditional ritual. This was fairly common practice when ANC combatants were about to leave on a mission, and Boshielo, a trained herbalist, may have conducted the ritual himself. Having been thus fortified, Boshielo and his men would have been confident of the success of their mission.Footnote67 By contrast, in the third week of August, Tambo received an alarming report that the South Africans were aware of Boshielo’s plans. About to suggest another delay, he found Boshielo and his companions already gone.Footnote68

The Journey

From Lusaka the men made their way south to the Zambezi River, to be ferried across to the Eastern Caprivi. Until recently, it was surmised that when they arrived at the river a quarrel ensued between their Zambian guide and a team of paddlers that had been hired. According to this version of events, the guide was paid 140 Zambian Kwacha, worth about US$200 at the time, but had pocketed most of the money, after which a disgruntled boatman then betrayed Boshielo and his men to the South African authorities.Footnote69 However, this seems improbable. First of all, it is doubtful that a team of paddlers was hired, since four men can be ferried across the Zambezi by a single boatman in a fair-sized mokoro.Footnote70 If the men wanted to avoid attention this would have been the better option. Secondly, the time frame is problematic. A boatman who wished to inform on the men would first have to make his way to the police post at Katima Mulilo or Ngoma – a journey of many hours by foot or bicycle along sandy tracks. Even if the police rushed over to investigate, the Zambian and the intruders would have been long gone.Footnote71 Rather, the information that had reached Oliver Tambo was accurate: Boshielo’s mission was betrayed even before their departure. The SAP-S had received intelligence about a party of ANC combatants who planned to travel from Zambia through the Eastern Caprivi to Botswana. As a result, patrols of the Zambezi River were stepped up and policeboats visited the fishing huts that dot its banks. In due course the police found a fisherman who knew something.Footnote72

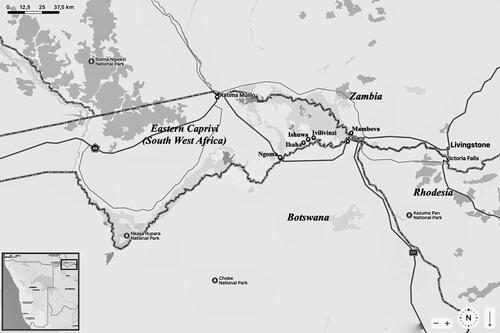

The fisherman was a man named MaShamunihango Liswaniso. He had a fishing hut at Nantungu, a small island in the Zambezi River. Liswaniso had been approached by a Zambian who asked him to escort a party of strangers through the Eastern Caprivi to the Chobe River. The police told Liswaniso to agree to the Zambian’s request and offered him a substantial sum of money to lead the strangers into a trap at a pre-arranged location. Liswaniso agreed and made arrangements with the Zambian guide. The Zambian would bring the men to Mambova, on the Zambian side of the Zambezi and Liswaniso would transport them across the river to the Eastern Caprivi. From there Liswaniso would escort them a short distance across the floodplains to the Chobe River, where he would help them to cross into Botswana. Secretly Liswaniso and the police made different plans. Instead of leading Boshielo and his men directly south, Liswaniso would wait for nightfall to lead them parallel to the Chobe River in a westerly direction (see ). The police would intercept them along this route.Footnote73

Figure 1. Map of the Eastern Caprivi in 1970, showing Ngoma, Ihaha, Ishuwa, Ivilivinzi and Mambova. (Source: Apple maps, retrieved on 4 July 2023, adapted by author.)

At the appointed date and time Liswaniso and the men did not show up. Instead, Liswaniso had brought the men across the river in his mokoro and then taken them to his island hut.Footnote74 After waiting for hours, the SAP-S team, under the command of Major Jaap Bekker, retreated to the nearby Ngoma police post at the Botswana border. Bekker dispatched two police officers to investigate. They hurried to the main police office at Katima Mulilo, and from there took a speedboat downriver to Nantungu. Travelling through the night – a perilous undertaking since they had to be on a constant lookout for shallow sandbanks and submerged hippos – they arrived at Liswaniso’s hut at daybreak. They found a woman there and learned that Liswaniso had left some hours earlier with four people. The policemen rushed back to Katima Mulilo and radioed Ngoma, warning the waiting police team that four ANC combatants had entered the Eastern Caprivi. As it happened, Liswaniso had meanwhile turned up at Ngoma.Footnote75

Before daybreak Liswaniso had left Nantungu with Boshielo and his companions. They walked until first light, then stopped at a clump of trees and vegetation known as Gofue, where Liswaniso told the men to stay hidden while he surveyed the area. From Gofue, he went on to nearby Ivilivinzi. Early that morning the headman of Ivilivinzi, Simataa Nelson Musipili, found Liswaniso at his gate. Liswaniso informed headman Musipili that he was escorting four foreigners – ‘criminals from another country’ – through the area, and that he was on his way to arrange transport to Katima Mulilo.Footnote76 He claimed to have left the men at Gofue because ‘those people must not enter anyone’s village’.Footnote77 Liswaniso said that the strangers were armed and asked headman Musipili to warn the villagers to avoid the area, since they might be fired upon. Musipili recounted that after Liswaniso departed on a borrowed bicycle, he and the villagers were left speculating that one of their own sons might be among the foreigners, perhaps having secretly returned from exile. It might even be Richard Kapelwa Kabajani, a well-known resistance activist from Ivilivinzi, who had joined SWAPO and was sought by the South African authorities. Musipili and his fellow villagers were concerned that Liswaniso might be assisting the police, but despite their apprehension they heeded Liswaniso’s warning and stayed away from Gofue.Footnote78 Only later did it become known that a few school boys had passed Gofue that day, and had spent some time playing soccer with the strangers.Footnote79

From Ivilivinzi, Liswaniso went to the Ngoma police post to finalise plans for the capture of the four men. The police had decided to intercept them at a place called Ishuwa, situated on an open plain halfway between Ivilivinzi and Ihaha villages.Footnote80 The location was chosen for a good reason. Each year when the Zambezi River comes down, the Eastern Caprivi’s floodplains become inundated and travel between villages is made treacherous by submerged channels that cut across the landscape. Come August, when the floods have receded somewhat, Ishuwa offers a safe place to ford one of the deeper channels.Footnote81 Here the police would lay an ambush. As the floodplains are virtually flat and treeless and offer few places to hide, the ambush had to take place after dark, and the policemen ordered Liswaniso to wait until sunset to bring the men to the crossing place.Footnote82

Later that day, headman Musipili found Liswaniso back at his gate to return the bicycle. Liswaniso informed him that he would escort the strangers from Gofue to Ishuwa, where a vehicle would be waiting on them. This strengthened Musipili’s suspicions that Liswaniso had arranged to meet the police, since at the time very few civilians owned cars. Becoming ever more uneasy, Musipili voiced his misgivings. He said that, since the strangers carried weapons, maybe the men with the vehicle would also be armed. And what if a fight broke out between the two groups? He asked Liswaniso how he would prevent such a turn of events. Liswaniso laughed it off and told Musipili, ‘don’t worry, leave it to me’.Footnote83

The SAP-S team arrived at Ishuwa in the late afternoon. They had hidden their vehicles in a clump of trees at Ihaha and walked the rest of the way. Before dark they were in position between the reeds and behind a very slight rise.Footnote84 Meanwhile, Liswaniso and Boshielo and his companions were making their way across the marshy landscape. As was later related by Liswaniso to headman Musipili, they reached Ishuwa just after nightfall. Since the channel at Ishuwa still ran knee deep, Liswaniso cautioned the men that it would be extremely slippery and told them to follow in his exact footsteps. Given the likelihood of getting wet, he offered to carry their weapons for them, which three of the men accepted. Liswaniso then started wading through, carrying most of the weapons. The four men were strung out behind him, following in his steps as best they could in the dark. Halfway across the stream, Liswaniso suddenly broke into a run and put some distance between himself and the other four. At that moment the police switched on their spotlight and opened fire.Footnote85

In the villages at Ivilivinzi and Ihaha the shots were clearly heard, and from the near side of Ivilivinzi people were able to see the spotlight in the distance. Headman Musipili remembers saying: ‘[l]isten to that, those people must be dead by now’. On the morning after the shootings, the elders at Ivilivinzi forbade the village children to follow the usual route past Ishuwa to their school at Nakabolelwa. They were told to take a detour. Later that day, after the police had departed, a few curious boys went to examine the site. They found spent cartridges and reeds that were damaged by bullets. It took a few days before the villagers dared to pass Ishuwa again, but when they did, they found footprints indicating that there had been a survivor. What happened to the bodies of those who were killed was unclear. Headman Musipili heard they were taken to Katima Mulilo and that some people were shown the bodies. According to him, if the men had been buried at Ishuwa, the villagers would definitely have found the grave.Footnote86

The police recorded their own version of the events of that night, and two written statements were included in an inquest dossier.Footnote87 The first statement is by SAP-S Captain Schalk Visser. He stated that on 20 August 1970 he and his colleagues were on duty five miles east of Ihaha, after having received positive intelligence that a group of terrorists had infiltrated the Eastern Caprivi on their way to South Africa. According to Visser, at about 7 p.m. the police encountered the men. They were ordered to surrender but instead tried to run, upon which the police opened fire to prevent their escape. Visser reported that, although the aim was not to kill the men, three of them died of their wounds. He listed them as ‘Faldini Mziwonke @ Castro Dolo’, ‘Theophillus Makalipi @ Victor Dhlamini’ and Joseph Mgomane. Presumably, these names were copied from some form of identification that the men carried, and referred to Castro Dolo, Victor Ndaba and Boshielo respectively.Footnote88 SAP Detective Warrant Officer Izak Bosman filed the second statement. He recorded that during the night of 20 August he arrived at a scene five miles east of Ihaha and there found the bodies of three black men. Bosman states that in the morning he transported the bodies to the mortuary at Katima Mulilo hospital and identified them to the district surgeon.Footnote89

District surgeon Frans Blignaut performed post-mortem examinations of the men’s bodies that same day. His report indicates that each of the men had been killed by a single gunshot. He examined Flag Boshielo’s body first. Boshielo had been shot in the right buttock, after which the bullet travelled through his liver and right lung before lodging in his right shoulder blade. He died of asphyxia. Castro Dolo was shot in the back of the head and the bullet exited above his left eye. Victor Ndaba was shot in the back, just to the left of his spine, and the bullet exited his body one inch to the left of his sternum.Footnote90

On 31 August word reached ANC headquarters in Lusaka that Boshielo and his men had been intercepted, that two of them were killed, one was captured and one escaped. A further report in mid September stated that all four had been killed. Oliver Tambo’s worst fears about the mission were confirmed. Together with Chris Hani, Joe Modise and John Pule Motshabi, he travelled to the Zambian side of the Zambezi River to investigate, but they were unable to establish what had happened with any certainty.Footnote91 Unbeknown to them, on 27 October 1970, a formal inquest was held at Katima Mulilo into the deaths of Flag Boshielo, Castro Dolo and Victor Ndaba. It was presided over by P.N. Hansmeyer, at that time Bantu Affairs Commissioner and resident magistrate. Being compelled to investigate any death that occurred from other than natural causes, the police statements and post-mortem reports regarding the three men were duly submitted.Footnote92 Hansmeyer found that their deaths had not been ‘brought about by any act or omission involving or amounting to an offence on the part of any person’.Footnote93 To the South African authorities, this marked the end of the matter. They did not issue an official statement regarding the capture or killing of ANC combatants in South West Africa, neither was it reported to the media.Footnote94 With no credible information forthcoming, the ANC’s attempts to establish the fate of Boshielo and his companions eventually stalled.

Aftermath

The disappearance and the failed mission of Flag Boshielo and his companions had profound and long-lasting effects in many ways. The failure of the mission had an impact on the ANC itself, but also affected South Africa’s counter-insurgency strategy in the Eastern Caprivi, which included oppressive repercussions for the local population. However, it was the families of the four men who indubitably suffered the most tragic consequences.

To the ANC the loss of four senior and experienced MK members was a severe blow, commemorated a year later by Tambo as the sacrifice of ‘some of the greatest sons of our country’.Footnote95 The loss of Boshielo was felt in particular. As MK’s chief political officer he was a moderating force and provided a counterbalance to more militant approaches. Had his mission been a success, the ANC would have had a senior strategic thinker in place to coordinate the struggle within South Africa.Footnote96 Furthermore, the failure of the mission frustrated future attempts to return trained men to South Africa, since a safe route had still not been found. It was not until 1974, during the Mozambican transition to independence, that a route via Mozambique and Swaziland opened up, and the ANC could infiltrate MK cadres into South Africa. As for infiltrating senior NEC members, that took until Operation Vula in 1988, when Mac Maharaj returned to South Africa to lead the ANC underground resistance.Footnote97

Boshielo’s attempted mission also influenced South Africa’s counterinsurgent strategy. Just a week after the men had been intercepted, the headquarters of the South African Joint Combat Forces (JCF) issued warning of a ‘spectacular attack’ by a joint SWAPO, ANC and ZAPU force of 2,000 men.Footnote98 Military analysts considered the Eastern Caprivi to be a credible objective of this offensive, possibly with the aim of establishing a ‘Republic of Namibia’, supported and protected by the OAU and the UN. The report warned that capture of the Eastern Caprivi required no sophisticated weaponry, could be achieved with three hundred well-trained men and would have enormous propaganda value for the liberation organisations. The difficulty of countering such an enemy attack was emphasised: if the local airfield at Mpacha should fall in enemy hands, and if the rivers were high, it could take more than a week to move troops by road from South Africa to the area, thus giving the enemy time to secure the new ‘Republic’. The report further claimed that secret weapon dumps were being established in the Eastern Caprivi and Zambia, and that in early August six ANC insurgents, possibly a recce patrol, had been seen near Kazungula on the Zambezi, while four terrorists – clearly a reference to Boshielo and his companions – later entered Caprivi and were thought to have been part of this ANC vanguard. An appreciation of the situation suggested the need for immediate reinforcement of the police in the Eastern Caprivi, while initiating a build-up of military strength in the region.Footnote99 Accordingly, just eleven days after the ambush of Boshielo and his men, Lieutenant-General Charles Fraser, the General Officer Commanding JCF, ordered the military reinforcement of the Eastern Caprivi through Operation Flemish.Footnote100

Under Operation Flemish, the Eastern Caprivi saw a surge in security measures and the local population came under increasing pressure to collaborate with the South African forces. A month after the events at Ishuwa, Bantu Affairs Commissioner Hansmeyer called a meeting with members of the MaSubiya people, on whose territory the ambush at Ishuwa had taken place. Major Jaap Bekker, who had led the ambush, was in attendance. Addressing the meeting, he announced plans to increase security in the Eastern Caprivi and to establish three more police stations in the region. Bekker also promised good payment for information about any passing strangers and referred to a group of people that had tried to secretly pass through Caprivi on their way to Botswana.Footnote101 In March of the next year, at a joint meeting with the MaSubiya and MaFwe people, further measures were introduced by the Commissioner-General for the Eastern Caprivi, Professor Evert Frederick Potgieter.Footnote102 Discussing the danger of the infiltration of the Eastern Caprivi by terrorists, he declared that they disrespected traditional authorities and would be armed and ready to kill. Therefore, he proposed a trained and armed ‘tribal police’ that would not only be the eyes and ears of the chiefs but would co-operate with the South African police in the interest of the Caprivi and its people.Footnote103

The thinly veiled attempts to impose local collaboration were met with reticence. The wave of repression and brutality of 1968 was not forgotten, and the police and administration were deeply distrusted. So were collaborators and informers. Liswaniso’s role in the death of Boshielo and his men was an open secret, and in the villages on the eastern floodplains of the Eastern Caprivi he was spoken of as ‘the one who betrayed the foreign freedom fighters’.Footnote104 Liswaniso was fortunate to be friendly with Chief James Mutwa of the BaSubiya. To protect Liswaniso, and to prevent repercussions that might lead to trouble with the South African authorities, Chief Mutwa arranged for Liswaniso to relocate to Kasika on the Chobe River, where he would be relatively safe.Footnote105

The disappearance of Boshielo and his companions also had an effect on their families. Uncertainty about a loved one’s whereabouts, and whether they are still alive, has been described as the most devastating kind of loss.Footnote106 It was a loss the families had to bear for many years. When the ANC came to power almost twenty-four years later, the families were informed of the men’s presumed deaths, but few of their questions could be answered. The establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) might have offered a chance to uncover more information, since the Boshielo case fell within its mandate, and similar cases of missing activists were heard.Footnote107 However, no testimony regarding the Boshielo mission was forthcoming. At the conclusion of the TRC hearings, a list of 477 missing persons was handed to the Missing Persons Task Team. Of the four men only Victor Ndaba (listed as Theo Mkhalipi) appeared on the list. Boshielo’s name was not included.Footnote108

Based on the research that led to this article, the families of Flag Boshielo, Castro Dolo and Victor Ndaba could only in recent years be informed of the men’s final fate. The families’ grief has been compounded by not having a body to bury or grave to visit. Full burial and funeral rites are, by custom, vital in ensuring that deceased family members become ancestral spirits and part of the ‘living dead’. Only then can they assist family members in times of adversity and play a role in their prosperity. Moreover, ancestor veneration is anchored to the physical location of a place of burial. At the grave, ancestors are honoured through gifts and sacrifices and may be consulted about problems.Footnote109 In the case of Boshielo and his companions, the continuum of interaction between the living and the living dead has been ruptured. No funeral rituals were held, there is no gravesite to visit and the families lost an important source of ancestral assistance.

The contribution to the struggle by Boshielo and his companions was recognised in 2005 by the South African government. Boshielo was posthumously awarded the Order of Luthuli in gold, while in 2012, all four men were awarded a campaign medal for the mission that led to their disappearance.Footnote110

Unsolved Questions

The inquest dossier and the accounts of the Eastern Caprivi villagers cleared up a number of uncertainties about the final journey and fate of Boshielo and his men. Nevertheless, the new information also generated further questions and some of them will be addressed in this section.

Information on the preparation of the mission has remained vague. A matter of great interest relates to the objective of Boshielo’s mission, and whether he had specific instructions regarding his task inside South Africa. Given the secrecy of the mission, it is perhaps no surprise that the available literature considers this in only the most general terms, as discussed above. Because of the danger of leaks, concrete instructions may not have been consigned to paper. Furthermore, regarding their planned trek through the Eastern Caprivi, it seems reasonable that Boshielo and his men would have consulted their SWAPO colleagues. The ANC and SWAPO had shared facilities at Kongwa since 1964, and some of the SWAPO cadres were former members of the Caprivi African National Union (CANU), an organisation that had emerged in the Eastern Caprivi in the early 1960s and merged with SWAPO in 1964.Footnote111 CANU members spoke Lozi, the lingua franca of southern Zambia and the Eastern Caprivi, and knew the rivers and local conditions in the Eastern Caprivi like no other. This raises the question of whether one of them might have acted as a guide, at least to reach the Zambezi.

The identity of the guide is of further interest since he may have had knowledge pertaining to the betrayal of Boshielo and his men. The police knew they were coming, which indicates that the SAP-S had informers in Zambia, perhaps even within the ANC. Curiously, Tambo knew beforehand that the men had been betrayed, although he was too late to warn them.Footnote112 This surely led to top-level discussions within the ANC, of which minutes or memoranda may have survived.

Regarding official records related to Boshielo’s mission, it is conspicuous how little has been found. The ambush and their deaths would have generated a documentary trail – they would have been fingerprinted, and their bodies, possessions, money and weapons photographed and meticulously logged.Footnote113 Since the men had all been under arrest at some point before leaving South Africa for exile, any new information would have been cross-referenced with records held in Pretoria, generating more reports. As in cases in the Missing Persons Task Team’s search for others who disappeared during the struggle, none of this has been found. This paucity of material may be related to the destruction and removal of numerous police records at the time of South Africa’s transition to democracy in 1994.Footnote114

A fortunate discovery was the dossier containing the inquest into the deaths of Flag Boshielo, Castro Dolo and Victor Ndaba in the National Archives of Namibia. Until now the sole archival source regarding their fate, this dossier added further information to the interviews. Nevertheless, it also raises questions about what purpose the records served and how accurately and fully they reflect the events at Ishuwa.

Foremost among the unresolved elements of the case is the peculiar absence of any reference to Bob Zulu, the fourth man of the Boshielo mission. It raises the possibility that he survived the ambush. The phrasing of Captain Visser’s statement that ‘three of the terrorists perished’ indicates that there was at least one other person in the group.Footnote115 It confirms headman Musipili’s testimony that footprints at Ishuwa indicated that one person survived.Footnote116 Intriguingly, almost four years later Bob Zulu’s name appears in a police security report, titled ‘Bob Zulu and three others’, which declares that Bob Zulu and Bennet Ndazuka, alias Madiba, are one and the same person, and that Sergeant H.P Nicholson in Umtata is interested in Ndazuka’s activities.Footnote117 In 1974 Bob Zulu, aka Bennet Ndazuka, may therefore have been alive and employed by the SAP. One of the interviewed policemen may have inadvertently confirmed this when he said, ‘I don’t know the names of those guys. One was Bob Zulu. He was a policeman’.Footnote118 It is not an unlikely scenario that Bob Zulu survived and joined the SAP. He may have been ‘turned’ to become an askari, which was not without precedent.Footnote119

The inquest dossier also raises questions about the shooting of the three other men. The post-mortem reports show that they were all killed by a single shot from behind. This may be explained by Captain Visser’s statement that the men were shot while trying to escape, and that their deaths were not intended. It may be so, for the preferred outcome might have been to apprehend the men in order to interrogate them. After all, they were a potential first-hand source of valuable information about the ANC in exile. However, it is equally possible that the captain’s statement shrouds what was essentially an extrajudicial killing – not an unusual practice at the time.Footnote120 When pressed for details, former SAP-S members claimed to have no clear recollection of the event and blamed their failing memories; one of them, however, did say of the men in Boshielo’s group that ‘they were not arrested. We shot them on the spot’.Footnote121 Another possible scenario emerged some years later, when the department of military intelligence of the South African Defence Force issued a memorandum stating that two participants of the Wankie campaign had been killed by the SAP ‘in an engagement in the Caprivi Strip on 20th August 1970’. The term ‘engagement’ implies an armed skirmish in which Boshielo and his men returned fire.Footnote122 Unless new information emerges, it will remain unclear whether the men were executed on the spot, were shot while trying to escape or died in combat.

Finally, as noted, the interviews and archival records have not led to the recovery of the men’s bodies. A former SAP-S member mentioned a secret burial in an unmarked grave, but this information has not been corroborated.Footnote123 If the deaths of Boshielo and his companions constituted an extrajudicial killing, the chances of finding their bodies are remote. As became clear during the TRC hearings, evidence of unlawful killings was routinely hidden, usually by the secret burial or destruction of the bodies at undisclosed locations. Unless they agree to talk, the perpetrators may take their knowledge to the grave.Footnote124

Conclusions

The difficulty of accounting for those who disappear in times of war has been ascribed to chaotic conditions that govern armed combat, the lack of accurate record keeping or careless treatment of the bodies of those who were killed on hostile territory.Footnote125 This article has identified several factors that hampered efforts to collect information regarding the Boshielo case, such as the dearth of archival data, the unwillingness of perpetrators or witnesses to provide information and the passage of time.

Although the article was able to throw light on events leading up to and including the ambush at Ishuwa and the death of Boshielo, Castro Dolo and Victor Ndaba, gaps remain in our knowledge. Some of these questions will hopefully be answered at a future date. Even this late in the day, systematic research among former ANC colleagues of Boshielo and his men may throw light on some unresolved puzzles. Perhaps more clues can be found in Zambia. Archives may yield new material, and former members of the South African security apparatus may come forward with further information. Nevertheless, it is also possible that residual questions regarding Boshielo’s mission may never be answered. In similar cases, the Missing Persons Task Team has arranged for a spiritual repatriation, in which family members visit the location where their loved one died, and where they ceremonially invite the spirit of the deceased to leave the place of death and to return home with them.Footnote126 At least for the families, this might represent a measure of closure regarding their missing loved ones.

Lecturer, Centre for Conflict Studies, Department of History and Art History, Utrecht University, Drift 6, 3512 BS, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected]

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-3178-4699

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of Professor Stephen Ellis who first alerted me to the disappearance of Flag Boshielo and his companions. I would like to thank Benjamin Chika-Matondo Mabuku of the Zambezi Region, Namibia, for his invaluable support and contribution to the research for this article.

Notes

1 South West Africa was a United Nations (UN) mandated territory under South African rule until independence in 1990, when it became the Republic of Namibia. At that time the Eastern Caprivi was renamed as the Caprivi Region, and in 2013 as the Zambezi Region. The region is located at the eastern-most end of a strip of land historically known as the Caprivi Zipfel, which separates Zambia in the north from Botswana in the south. This article uses the official names in use at the time of the events described: for example, South West Africa, Eastern Caprivi, Rhodesia.

2 While conducting fieldwork on another project in Namibia, I used the opportunity to enquire about the disappearance of Boshielo and his men. Benjamin Chika-Matondo Mabuku was the first to affirm that local residents were familiar with such an event. He spoke of freedom fighters who had been betrayed and ambushed near his family’s village in the Eastern Caprivi, and said: ‘I do not have the facts. But this incident happened. The place is known, and people will be able to locate it’. Interview, Benjamin Chika-Matondo Mabuku, Windhoek, 24 April 2014. Unless otherwise stated, all interviews were conducted by the author.

3 A. Lissoni, ‘Transformations in the ANC External Mission and Umkhonto we Sizwe, c. 1960–1969’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 35, 2 (2009), p. 293.

4 J.D. Aronson, ‘The Strengths and Limitations of South Africa’s Search for Apartheid-Era Missing Persons’, International Journal of Transitional Justice, 5, 2 (2011), p. 264.

5 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (hereafter TRC), Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 6 (2003), pp. 532–6. Also see N. Rousseau, ‘Identification, Politics, Disciplines: Missing Persons and Colonial Skeletons in South Africa’, in É. Anstett and J.M. Dreyfus (eds), Human Remains and Identification: Mass Violence, Genocide and the ‘Forensic Turn’ (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2015), p. 188.

6 F. Mbali, In Transit: Autobiography of a South African Freedom Fighter (Cape Town, Xlibris Pub., 2011), p. 130; R. Kasrils, ‘Kasrils, Ronnie [Third Interview]’, interview by H. Barrell, Johannesburg, 28 October 1990, (hereafter Kasrils, ‘Third Interview’), O’Malley archive, available at https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/index.php/site/q/03lv00000.htm, retrieved 5 March 2024; ‘The Thinker Puts Questions to Ronnie Kasrils on the Role, Function and Achievements of Umkhonto we Sizwe’, The Thinker, 52 (2013), p. 20; H. Barrell, ‘Conscripts to Their Age: African National Congress Operational Strategy, 1976–1986’ (PhD thesis, Oxford University, 1993), p. 68; P. Delius, A Lion amongst the Cattle: Reconstruction and Resistance in the Northern Transvaal (Portsmouth, Heinemann, 1996), p. 177.

7 Oliver Tambo during a speech at University of Lagos in Nigeria, 1971, quoted in V. Shubin, ANC: A View from Moscow (Bellville, Mayibuye Books, 1999), p. 101. Also see G. Houston and B. Magubane, ‘The ANC’s Armed Struggle in the 1970s’, in South African Democracy Education Trust (hereafter SADET) (eds), The Road to Democracy in South Africa. Volume 2 (1970–1980) (Pretoria, UNISA Press, 2006), p. 454; ‘ANC (SA) Splits. White-Led SACP Distorts National Question, Created Division’, Ikwezi, 2, 1 (March 1976), p. 29; H. Macmillan, ‘The African National Congress of South Africa in Zambia: The Culture of Exile and the Changing Relationship with Home, 1964–1990’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 35, 2 (2009), p. 314; S. Ellis, External Mission: The ANC in Exile, 1960–1990 (London, C. Hurst & Co, 2012), pp. 85–6; T. Simpson, Umkhonto we Sizwe: The ANC’s Armed Struggle (Cape Town, Penguin Books, 2016), p. 175.

8 T. Lodge, Black Politics in South Africa since 1945 (New York, Addison-Wesley Longman Ltd, 1983), p. 302; S. Ellis and T. Sechaba, Comrades against Apartheid: The ANC & the South African Communist Party in Exile (London, J. Currey, 1992), p. 59; A. Sibeko and J. Leeson, ‘Faldon (Castro) Mzwonke’, in Archie Sibeko’s Roll of Honour: Western Cape ANC Comrades 1953–1963 (Bellville, University of the Western Cape, Diana Ferrus Publishers, 2008); T. Gibbs, Mandela’s Kinsmen: Nationalist Elites and Apartheid’s First Bantustan (Johannesburg, Jacana Media, 2014), p. 179; G. Houston, S. Mati, D. Seabe, J. Peires, D. Webb, S. Dumisa, K. Sausi, B. Mbenga, A. Manson & N. Pophiwa, ‘The Liberation Struggle and Liberation Heritage Sites in South Africa (Prepared for the National Heritage Council)’ (Human Sciences Research Council), 25 November 2013), p. 234; S. Sijake, ‘Moses Kotane Memorial Lecture’ (Limpopo, ANC Veterans League, 12 April 2019); K. Morewane, ‘Nchabeleng Remembered. A Combatant for Life, a Patriot to the End’, The Thinker, 53 (2013), p. 57.

9 The Presidency of the Republic of South Africa, ‘National Orders Booklet’, 2005, p. 17; copy of the document held by the author.

10 In the documents and literature, the men are referred to by various names. These include family names, titles, noms de guerre and nicknames. In addition, there are multiple spellings of their names. The names listed here are used throughout the article. Discrepancies are explained in a footnote where necessary. Note: in documents and statements by the South African state and its officials, the men are referred to as terrorists, as were all members of the ANC since in the early 1960s, when the South African authorities designated the ANC as a terrorist organisation. By contrast, in his opening statement at the Rivonia trial, Nelson Mandela stated that ‘the violence which we chose to adopt was not terrorism’ (Pretoria Supreme Court, 20 April 1964), available at https://www.un.org/fr/events/mandeladay/court_statement_1964.shtml, retrieved 11 March 2024.

11 L. Douglas, ‘Mass Graves Gone Missing: Producing Knowledge in a World of Absence’, Culture & History Digital Journal, 3, 2 (2014), p. 9; N. Nieftagodien, ‘The Place of “The Local” in History Workshop’s Local History’, African Studies, 69, 1 (2010), pp. 41–2. For South African researchers who engaged with local knowledge in the search for missing persons, see: M. Fullard, ‘Some Trace Remains (An Extract)’, Kronos, 44, 1 (2018), pp. 163–80; R. Mendes, ‘The Everyday Life and the Missing: Silences, Heroic Narratives and Exhumations’ (MA thesis, University of the Western Cape, 2020); R. Moosage, ‘Missing-Ness, History and Apartheid-Era Disappearances: The Figuring of Siphiwo Mthimkulu, Tobekile “Topsy” Madaka and Sizwe Kondile as Missing Dead Persons’ (PhD thesis, University of the Western Cape, 2018).

12 The story was known most notably in the villages of Nakabolelwa, Ivilivinzi and Ihaha in the Zambezi Region of Namibia.

13 M. Halbwachs, On Collective Memory (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 23; Douglas, ‘Mass Graves gone Missing’, p. 3.

14 The SAP-S members agreed to be interviewed on condition of anonymity. Their names and the place and time of the interviews are therefore withheld.

15 T. Keenan, ‘Getting the Dead to Tell Me What Happened: Justice, Prosopopoeia, and Forensic Afterlives’, Kronos, 44, 1 (2018), p. 102.

16 For a more detailed history of Boshielo’s life, see Delius, A Lion amongst the Cattle.

17 N. Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (Boston, Bay Back Books, 1995), p. 122.

18 P. Delius, ‘Sebatakgomo; Migrant Organization, the ANC and the Sekhukhuneland Revolt’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 15, 4 (1989), pp. 605–7.

19 B. Magubane, P. Bonner, J. Sithole, P. Delius, J. Cherry, P. Gibbs & T. April, ‘The Turn to Armed Struggle’, in SADET (eds), The Road to Democracy in South Africa. Volume 1 (1960–1970) (Cape Town, Zebra Press, 2004), p. 76; Shubin, ANC: A View from Moscow, pp. 43–4.

20 L. Callinicos, Oliver Tambo: Beyond the Engeli Mountains (Claremont, David Philip, 2004), p. 366.

21 Ellis, External Mission, pp. 77–8.

22 Informal discussion with author, Pallo Jordan, James April and Zolile Nqosi, Cape Town, 9 July 2017; interview, Mavuso Walter Msimang, Zoom video call, 7 September 2021; Kasrils, ‘Third Interview’.

23 A. Lissoni, ‘The South African Liberation Movements in Exile, c.1945–1970’ (PhD thesis, SOAS, University of London, 2008), pp. 260–1; H. Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro: The Continuing Crisis in the African National Congress (of South Africa) in Zambia, 1969–1971’, Social Dynamics, 35, 2 (2009), pp. 300–1.

24 Delius, ‘Sebatakgomo’, pp. 602–3.

25 The Terroriste Album was created in the early 1960s as a record of individuals who had left for exile, or were deemed to be opposed to apartheid. J. Dlamini, The Terrorist Album: Apartheid’s Insurgents, Collaborators, and the Security Police (Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 2020). Castro Dolo appears on p. 114, Victor Ndaba on p. 82 and Bob Zulu on p. 117; see SAP Veiligheidsverslag, S.4/10746, 1 April 1974; copy of the document held by the author.

26 Mbali, In Transit, p. 128. In the Wankie and Sipolilo campaigns of 1967 and 1968, the ANC sent trained MK soldiers from Zambia through Rhodesia to infiltrate South Africa.

27 Issued on 25 July 2012, on the occasion marking the 50th anniversary of the formation of MK.

28 Mbali, In Transit, p. 129.

29 J. Slovo, ‘The Second Stage: Attempts to Get Back’, Dawn, 10, Souvenir Issue (1986), p. 33; C. Hani, ‘The Wankie Campaign’, Dawn, 10, Souvenir Issue (1986), pp. 34–5.

30 G. Houston, ‘Oliver Tambo and the Challenges of the ANC’s Military Camp’, The Thinker, 58 (2013), p. 21; Lissoni, ‘Transformations in the ANC’, pp. 297–9. For more on general conditions at Kongwa camp, see C.A. Williams, ‘Living in Exile: Daily Life and International Relations at SWAPO’s Kongwa Camp’, Kronos, 37 (2011), pp. 60–86.

31 C.J. Makgala and B. Seabo, ‘“Very Brave or Very Foolish”? “Gallant Little” Botswana’s Defiance of “Apartheid’s Golden Age”, 1966–1980’, Round Table, 106, 3 (May 2017), p. 305.

32 P. Mgadla, ‘“A Good Measure of Sacrifice”: Botswana and the Liberation Struggles of Southern Africa (1965–1985)’, Social Dynamics, 34, 1 (2008), pp. 5–7; B. Mocheregwa, ‘The Police Mobile Unit. The Nucleus of the Botswana Defence Force, 1960s–1977’, Journal of African Military History, 3, 2 (December 2019), p. 106.

33 D. Dabengwa, ‘The 1967 Wankie and 1968 Sipolilo Campaigns’, The Thinker, 80 (2019), p. 10.

34 R.M. Ralinala, J. Sithole, G. Houston and B. Magubane, ‘The Wankie and Sipolilo Campaigns’, in SADET (eds), The Road to Democracy in South Africa. Volume 1 (1960–1970) (Cape Town, Zebra Press, 2004), pp. 479–540; Hani, ‘The Wankie Campaign’, p. 35; Dabengwa, ‘The 1967 Wankie and 1968 Sipolilo Campaigns’, p. 9.

35 ‘Our Fight Is against Apartheid, Not Botswana’, Sechaba, 2, 2 (1968), p. 15; Hani, ‘The Wankie Campaign’, p. 37; Ralinala et al., ‘The Wankie and Sipolilo Campaigns’, pp. 529–31.

36 H. Macmillan, ‘The “Hani Memorandum” – Introduced and Annotated’, Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 69 (2009), pp. 107–8; N. Ndebele and N. Nieftagodien, ‘The Morogoro Conference: A Moment of Self-Reflection’, in SADET (eds), The Road to Democracy in South Africa. Volume 1 (1960–1970) (Cape Town, Zebra Press, 2004), p. 587.

37 Macmillan, ‘The “Hani Memorandum”‘, p. 115. In 1963 a number of ANC leaders were arrested on Liliesleaf Farm in the Rivonia suburb of Johannesburg. During the subsequent trial many of them, including Nelson Mandela who had been arrested earlier, received life sentences. Most of the remaining ANC leadership fled the country, leaving no leaders to direct the domestic struggle.

38 Ibid., p. 119. Bob Zulu, one of Boshielo’s three companions, was named as a victim of the ANC’s cruel punishments. I was not able to establish the reason for his detainment, nor whether this had any bearing on his decision to join Boshielo’s mission. Regarding atrocities committed by MK, as claimed in The Hani Memorandum, in 1998 the TRC reported that both the ANC and PAC and their organs – including MK, committed gross violations of human rights in the course of their political activities and armed struggles; TRC Report, Volume 2 (1998), p. 325.

39 Fanele Mbali, informal discussion with author, Johannesburg, 21 June 2017.

40 Ellis, External Mission, p. 65.

41 Ralinala et al., ‘The Wankie and Sipolilo Campaigns’, pp. 537–8.

42 Available at http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/fanele-mbali, retrieved 29 April 2017; Ndebele and Nieftagodien, ‘The Morogoro Conference’, p. 589.

43 Report of the Subcommittee, July 1966, 24 August 1966, ANC Morogoro Papers, ANC Archives, UFH, p. 5; Ellis and Sechaba, Comrades against Apartheid, p. 55; Ndebele and Nieftagodien, ‘The Morogoro Conference’, p. 583.

44 In his speech at the ANC National Consultative Conference (June 1985), Oliver Tambo said, ‘[m]any who participated to ensure that the Morogoro conference was the success that it was, are no longer with us. I refer to such outstanding leaders, stalwarts and activists of our movement as … Flag Mokgomane Boshielo … and others’. ‘The Eyes of Our People Are Focussed on This Conference’, Sechaba, October 1985, p. 4.

45 Ellis, External Mission, pp. 77–8; Shubin, ANC: A View from Moscow, pp. 91–2; Simpson, Umkhonto we Sizwe, pp. 171–4.

46 Ellis, External Mission, pp. 83–4; V. Shubin and M. Traikova, ‘There Is No Threat from the Eastern Bloc’, in SADET (eds), The Road to Democracy in South Africa. Volume 3: International Solidarity (Pretoria, UNISA Press, 2008), p. 1006. For further discussion of reasons for the expulsion see S.M. Ndlovu, ‘The ANC’s Diplomacy and International Relations’, in SADET (eds), The Road to Democracy in South Africa. Volume 2 (1970–1980) (Pretoria, UNISA Press, 2006), p. 566.

47 Ellis, External Mission, pp. 83–4; Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, pp. 298–301.

48 South African National Defence Force, Department of Documentation, Pretoria (hereafter SANDF DoD), OD 1968 Aanv Dok Box 16, ‘Terroristebedreiging teen Suider Afrika’ (1960–1967), pp. 10–18, 21–3.

49 SWALA was SWAPO’s military wing. The name was changed to People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) at the Tanga conference held by SWAPO from 26 December 1969 to 2 January 1970.

50 Interview, former SAP-S member, 2012.

51 SANDF DoD, HVS Group 1 Box 31, ‘Die Militêr-Strategiese Waarde van die Caprivistrook’ (1966–1969), p. 6; SANDF DoD, Diverse Group 2 Box 28, ‘Oorsig van die Onkonvensionele Bedreiging teen Suid–Afrika’ (31 October 1967), pp. 14–15; SANDF DoD, HSI/AMI Group 3 Box 430, ‘Die Caprivistrook’ (1967), p. 13.

52 TIN was the acronym for Teeninsurgensie or counter-insurgency. M. de W. Dippenaar, The History of the South African Police 1913–1988 (Silverton, South Africa, Promedia Publications, 1988), p. 365.

53 Teen-Terroriste Ondervragingseenheid, in Afrikaans. The unit was deployed under command of the widely known ‘Rooi Rus’ Swanepoel. Also see G. Richter, ‘1967: Eerste Terroriste-Aanval in Die Oos-Caprivi: Kol Gawie Richter’, Nongqai, 10, 1 (2019), p. 52.

54 National Archives of South Africa, Pretoria (hereafter NASA), BAO 6702 Ref 105/44, ‘Caprivi Zipfel Administrasie 1940–1964’; Richter, ‘Eerste Terroriste-Aanval’, p. 52.

55 C. Murphy, ‘Information Sharing Workshop’, report, held at Imusho Ward, Sioma Ngwezi National Park, Zambia, (Conservation International, 2007), p. 14; National Archives of Namibia, Windhoek, South West Africa (hereafter NAN), LKM SU 3/3/18, ‘Tribal Authorities – Basubia Meetings 1968’, 23 November 1968.

56 Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, pp. 305–6.

57 African National Congress, ‘Strategy and Tactics of the African National Congress’ (Morogoro, 1969), p. 8.

58 Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, p. 305.

59 Ibid.

60 Ibid., p. 306.

61 University of Cape Town Libraries: Special Collections, Jack Simons Papers, ZA UCT BC1081, J.P. Motshabi, ‘Brief Autobiography’ (1988), p. 11; Mbali, In Transit, p. 129. Mbali accepted the invitation based on his ‘personal respect of and confidence in Chief Commissar Boshielo and the calibre of his men’. He was prevented by circumstances from joining the mission.

62 Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, p. 306.

63 Mbali, In Transit, p. 130.

64 Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, p. 306.

65 Ibid.; Mbali, In Transit, p. 130; Zolile Nqosi, Pallo Jordan and James April, informal discussion with author, Cape Town, 9 July 2017.

66 Sibeko and Leeson, ‘Faldon (Castro) Mzwonke’, Chapter 35.

67 Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, p. 306; R. Suttner, ‘Being a Revolutionary: Reincarnation or Carrying over Previous Identities?’, Review Article, Social Identities, 10, 3 (2004), pp. 419–20; E. Harvey, Kgalema Motlanthe: A Political Biography (Johannesburg, Jacana Media, 2012), p. 44; interview, Mavuso Walter Msimang, video call, 7 September 2021; Delius, A Lion amongst the Cattle, p. 102.

68 Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, p. 306.

69 Ibid.; Ellis, External Mission, p. 85.

70 Mokoro (also makoro): a traditional dugout canoe, usually propelled by a single boatsman, standing up and punting with a long pole.

71 Informal discussion with author, Benjamin Mabuku, Dominic Mulenamaswe, Luckson Mulenamaswe and White Masule., Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015.

72 Interviews, former SAP-S members, 2012, 2019.

73 Ibid.

74 Interview, Gilbert Muhongo Mutwa, Windhoek, 4 July 2018; informal discussion with author, Benjamin Mabuku and White Masule, Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015.

75 Interview, former SAP-S member, 2012.

76 Interview, Simataa Nelson Musipili, Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015.

77 Ibid.

78 Ibid.; informal discussion with author, Benjamin Mabuku and White Masule, Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015.

79 Informal discussion with author, Benjamin Mabuku, Katima Mulilo, 11 June 2018.

80 Interview, former SAP-S member, 2012.

81 Informal discussions with author, Benjamin Mabuku, Dominic Mulenamaswe, Luckson Mulenamaswe and White Masule; and as observed by the author at Ishuwa, 14 July 2015.

82 Interview, Simataa Nelson Musipili, Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015; and as observed by the author at Ishuwa, 14 July 2015.

83 Interview, Simataa Nelson Musipili, Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015.

84 Interview, Altar John Mofu, Ihaha, 10 Sept 2015; interview, former SAP-S member, 2012.

85 Simataa Nelson Musipili, interview by author, Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015.

86 Ibid.; interview, Altar John Mofu, Ihaha, 10 Sept 2015.

87 NAN, LKM SU 3/2/1 File 1/7/2, ‘Inquests 1970–71’.

88 Faldini Mziwonke must refer to Faldon Mzwonke and I assume that Theophillus Makalipi @ Victor Dhlamini is Victor Ndaba, also known as Theo Mkhalipi @ Victor Dlamini. The third name (Joseph Mgomane) must either refer to Bob Zulu or Flag Boshielo. Since Flag Boshielo was also known as Mokgomane, I deduce that Boshielo was the third man, although it is not clear why he used the name Joseph.

89 NAN, LKM SU 3/2/1 File 1/7/2, ‘Inquests 1970–71’.

90 Ibid.

91 Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, p. 306; Ellis, External Mission, p. 85.

92 The South African Inquests Act of 1959.

93 NAN, LKM SU 3/2/1 File 1/7/2, ‘Inquests 1970–71’. Hansmeyer served in the Eastern Caprivi from 1968 till 1971. The P.N Hansmeyer Collection can be found at the Archive for Contemporary Affairs (ARCA), PV816, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. No mention was found among his papers of the highly unusual event of the deaths of three armed ANC cadres in the Eastern Caprivi.

94 Shubin, ANC: A View from Moscow, p. 101.

95 O. Tambo, ‘Minutes of the Meeting of the National Executive Committee of the African National Congress of South Africa’, transcript of opening address, Lusaka, 27 August 1971, available at https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/cis/omalley/OMalleyWeb/03lv03445/04lv04015/05lv04051/06lv04052/07lv04053.htm, retrieved 6 March 2024.

96 Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, p. 307.

97 Lodge, Black Politics, p. 302; T. Simpson, ‘“The Bay and the Ocean”: A History of the ANC in Swaziland, 1960–1979’, African Historical Review, 41, 1 (2009), pp. 98–100; T. Simpson, ‘Main Machinery: The ANC’s Armed Underground in Johannesburg during the 1976 Soweto Uprising’, African Studies, 70, 3 (2011), pp. 419–22; Shubin, ANC: A View from Moscow, pp. 332–9.

98 The report claims to be based on information provided by a reliable source. SANDF DoD, 1MG Box 122, Op Flemish 1970–71, ‘HQ JCF – Appreciation on Terrorist Threat to Carry Out a “Spectacular” Attack on the RSA in 1970/1971’ (26 August 1970).

99 Ibid.

100 Ibid., ‘Operational Directive no. 1/70, code name Flemish’ (31 August 1970).

101 NAN, KCA Vol 4 File N.1/15/4, Part III, ‘Notule van die Stamvergadering gehou te Bukalo op 25/9/70’.

102 E.F. Potgieter (1921–1996) was rector of South Africa’s University of the North (1960–1970) and Commissioner-General of the Machangana Territory (Gazankulu) and the Eastern Caprivi.

103 NASA, BAO 5/177 Ref 54/26/8, ‘Notule van Kwartaalvergadering van albei Stamme te Ngweze, gehou op 2 Maart 1971’, Katima Mulilo, 2 March 1971.

104 Interview, Simataa Nelson Musipili, Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015; interview, Altar John Mofu, Ihaha, 10 September 2015.

105 Interview, Gilbert Muhongo Mutwa, Windhoek, 4 July 2018; informal discussion with author, Benjamin Mabuku and White Masule, Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015.

106 P. Boss, Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 6.

107 Republic of South Africa Government Gazette, Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act, Vol. 361, No. 16579, Act No. 34, Section 4, 26 July 1995.

108 M. Fullard, head of the Missing Persons Task Team at South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority, email correspondence with author, 18 September 2021. Due to different interpretations of the criteria, as well as human error, the list of 477 was incomplete and inaccurate from the start. For instance, most of the TRC amnesty cases involving missing persons were not included on the list as in the cases of the Pebco three and the Mamelodi 10. In addition, there was a good chance that the missing family members of families who did not make statements to the TRC were not registered on the list.

109 Interview, M.E.K. Lebaka, WhatsApp video call, 15 September 2021; M.E.K. Lebaka, ‘A Theological Understanding of Ancestor Veneration in the Bapedi Society as an Expression of Transcendence and Anticipation of Comfort and Hope’, Dialogo, 8, 1 (2021), pp. 111, 114; M.E.K. Lebaka, ‘The Art of Establishing and Maintaining Contact with Ancestors: A Study of Bapedi Tradition’, HTS Theological Studies, 74, 1 (2018), pp. 1, 5.

110 ‘National Orders Booklet’ (2005), p. 17; Medals to be Issued on the Occasion Marking the 50th Anniversary of the Formation of MK (25 July 2012), p. 18; copy of the document held by the author.

111 Williams, ‘Living in Exile’, p. 67; C. Leys and J.S. Saul, Namibia’s Liberation Struggle: The Two-Edged Sword (London, James Currey, 1995), p. 42.

112 Macmillan, ‘After Morogoro’, p. 306.

113 N. Rousseau, ‘Death and Dismemberment: The Body and Counter-Revolutionary Warfare in Apartheid South Africa’, in E. Anstett and J.M. Dreyfus (eds), Destruction and Human Remains: Disposal and Concealment in Genocide and Mass Violence (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2014), p. 211; Rousseau, ‘Identification, Politics, Disciplines’, p. 177.

114 Fullard, ‘Some Trace Remains’, p. 167.

115 NAN, LKM SU 3/2/1 File 1/7/2, ‘Inquests 1970–71’. In Afrikaans, ‘by nadere ondersoek [is] vasgestel dat drie van die terroriste asgevolg (sic) van skietwonde beswyk het’.

116 Interview, Simataa Nelson Musipili, Katima Mulilo, 14 July 2015.