Abstract

Drawing on five years of intermittent ethnographic work at Kariba, I discuss the impoverishment of the Tonga of Mola chiefdom in the context of escalating human–wildlife conflict and frequent drought. I critically examine emerging competing forms of knowledge regarding traditional authority and environmental challenges between the chief and his subjects. I argue that persistent environmental crisis in the region is generating different conflictual forms of knowledge regarding traditional authority. In advancing this argument, I draw extensively upon the broader literature on power, authority and legitimacy. Local people firmly believe that these problems are induced by the current chief’s avoidance and reluctance to enact rainmaking ceremonies and to appease ancestors. I document people’s opinions about the current chief’s ‘rebellious’ behaviour and how they believe it exacerbates their impoverishment and suffering through drought and attacks by animals. I demonstrate why and how the chief’s behaviour contributes to the waning of his authority. The chief offers counter-narratives but, interestingly, both the chief’s and the people’s narratives relate to their relationship with the spirits and ancestors. By documenting these spiritual and religious narratives of human–wildlife conflicts and droughts, I extend the debates on power, knowledge and authority in southern Africa.

Doing Ethnography in Mola Chiefdom

‘Hesi Kutya’ (How are you, Kutya?) was the way in which the Tonga of Mola, particularly in Chitenge, Dhobe and Chiweshe villages, greeted me whenever they saw me. Kutya is a Shona term which means ‘fear’, while the Tonga word for fear is ‘kuyowa’. Villagers nicknamed me Kutya because I feared moving around the chiefdom at night. I avoided organising or making appointments for interview sessions and focus group discussions after 5 p.m. as this would involve walking at night. The Tonga of Mola nicknamed me using a Shona term because their language is increasingly borrowing Shona words. An elaboration of the development of my nickname elucidates how everyday life in Mola chiefdom is characterised by fear arising from problems such as witchcraft, human–wildlife conflict and droughts. Locally, these problems are strongly believed to be caused by both material and non-material forces, all encapsulated in the illegitimacy of the current chief, known as Rare.

The article discusses the conflictual relations between the chief and his subjects as mediated through the interpretation of local problems. Drawing upon literature on knowledge, power and authority, I delve into these competing forms of knowledge regarding local authority. Arguably, such knowledges are often formulated to advance particular agendas. I elucidate how ancestors and spirits are entangled in the fabrication of knowledge and interpretation of everyday problems. Such a discussion sheds light on the experiences and interpretations of droughts and wildlife attacks by marginalised communities.

During my early days of engaging in ethnographic research in this area in 2017, some people thought I feared witchcraft attacks, as witches are generally believed to operate at night. The Tonga people are generally stereotyped and labelled witches by some ethnic groups (such as the Shona and Ndebele) in Zimbabwe, and villagers thought that I held the same perceptions about them. The Shona and Ndebele people’s negative perceptions of the Tonga as well as the impacts on young Tonga generations are confirmed by previous studies that have listed some of the terms used to demean the Tonga, including ‘two-toed tribe’, ‘lazy’, ‘childlike’ and ‘witches’.Footnote1 These stereotypes are hinged on the marginalisation and underdevelopment of their chiefdoms. Some people thought I subscribed to the same views since I came from Kariba, a multiracial and multi-ethnic town where the Tonga inhabitants are also looked down on.

One morning, as I was going to pee in the bush nearer to the homestead I stayed in, one old man shouted: ‘Kutya … go a bit further … women and children fetching water at the well are watching you …. There are no witches … no one will hurt you … you are a visitor here’. It was at this moment that I realised that some people thought I was afraid of walking at night because I was scared of witchcraft attacks. I responded to him: ‘Sekuru [Grandfather], I am not scared of witches, I am scared of lions and hyenas’. From this day onwards, I explained to people that called me Kutya that I feared lions and hyenas, and not witches. I did not want to create an impression that I regarded people I was studying as witches, as this could have impacted on my ethnography. However, this did not stop them from calling me Kutya. When I went back there for intermittent fieldwork in 2020, 2021 and early 2022, people still referred to me as Kutya. I retained the nickname because I was still scared of moving around at night, albeit for different reasons to those held by the villagers earlier. This time human–wildlife conflicts were escalating. Lions and hyenas were attacking people and livestock almost every day. Sightings of these predators or their paw prints were reported informally and discussed at social sites (such as boreholes and wells, where women frequently meet when fetching water, or beer halls, where most men met for beer drinking). My fear of moving around at night was also heightened. Most villagers move around on foot in the area at night due to adaptation. Some could even go as far away as Lake Kariba, 15 kilometres on foot. Even though they are scared of animals, they have no choice because of limited means of transport.

To some people, my fear for animals was surprising because they knew I was born and bred in Kariba town, which is also a hotspot for human–animal conflicts.Footnote2 But for me the fear was heightened because it was a rural area with no electricity or proper road networks, which made it difficult to see animals at night. Studies of human–wildlife conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa substantiate my observation here by showing that underdevelopment and marginalisation in most of rural Africa heightens the incidence of human–animal conflicts.Footnote3 Of note is the absence of developed communications and road networks, resulting in humans travelling through bush inhabited by high numbers of animals, and unavailability of or inadequate water infrastructure (such as boreholes), resulting in women and girls travelling long distances to fetch water from rivers and wetlands within thick bush cover, thereby exposing themselves to attacks from animals.

In contrast, Mola villagers interpret increasing human–wildlife conflict in religious terms. For the Tonga, human–wildlife conflicts were escalating because of the ‘rebellious behaviour’ of the chief and the anger of the ancestors. It is alleged that Chief Rare avoids appeasing ancestors at the local malende rain shrine, because he fears the wrath of his ancestors. His coronation in the 1990s was controversial and some believe that he was not the rightful heir. He is also believed to have skipped some processes of the coronation. Many people that I interviewed say that he is scared of approaching sacred places, as this may result in grave consequences or his death. In addition, angry ancestors are believed to induce animal attacks as they ‘do not approve’ of the legitimacy of the current chief.

During the late 2010s and early 2020s there were frequent droughts that were also attributed to the ‘rebellious behaviour’ of the current chief. Such interpretations are used to put pressure on the chief to ‘do the right things’ regarding veneration of ancestors and the enactment of rainmaking ceremonies. These narratives are also used to question the legitimacy of the current chief. On the contrary, the chief blames his people for the occurrence of these calamities.

Competing Forms of Knowledge regarding Traditional Authority

The Tonga people of Mola speak the CiTonga language, but they also speak ChiShona eloquently because of their interactions over many years with Shona chiefdoms that speak the Shangwe dialect, including Musampakaruma and Nebiri. They are a matrilineal Bantu-speaking people who migrated from the north and settled in the Zambezi Valley around 1100 AD and were later displaced from the Zambezi due to the construction of the Kariba Dam.Footnote4

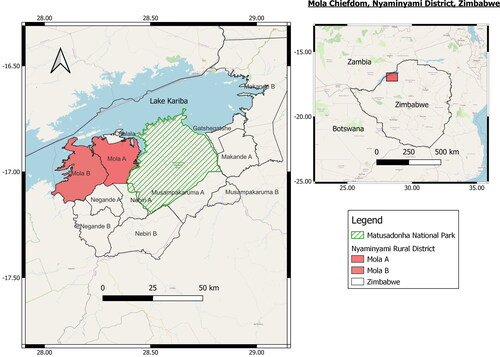

Mola is part of Nyaminyami district (as shown in ), and it is adjacent to Lake Kariba in the Middle Zambezi Valley. Mola chiefdom is within Matusadonha National Park. The park was established as a non-hunting reserve in 1963 and proclaimed a National Park in 1975. Its establishment resulted in the displacement of the Tonga from Dhela Valley where they had settled after their initial displacement in the late 1950s, induced by the construction of the Kariba Dam. Dhela Valley was within Matusadonha National Park and close to the lake. People were suspected of poaching, so the authorities considered that they needed to be pushed further inland to minimise their contact with the game park. The game park is managed by the Zimbabwe National Parks and Wildlife Management Authority. There is no physical demarcation between the chiefdom and the game park, hence the two are always in contact and conflict. The majority of Tonga people survive below the poverty datum line. Too few economic opportunities were made available to them by both the colonial and postcolonial governments. As a result, Tonga chiefdoms remain marginalised, with poor infrastructure, health facilities and schools.Footnote5

Figure 1. Map showing the location of Mola in the Middle Zambezi Valley, northwestern Zimbabwe. (Photograph by the author.)

In this article, I draw on ethnography in Mola to extend scholarly debates on knowledge, authority and tradition in sub-Saharan Africa. In the words of Shannon Morreira and Fiona Iliff, who have shown how the Nharira Hills in eastern Zimbabwe are entangled in conflicts between different kinds of knowledge, ‘[s]truggles over ways of knowing, and what sorts of knowledge are deemed accurate, operationalizable, and legitimate, have lain at the heart of struggles for authority in colonial and postcolonial Africa’.Footnote6 Different actors hold varied knowledges about the Nharira Hills including ‘traditional knowledge about sacred spaces; legal knowledge about those sacred spaces and about the right of individuals and communities; and the politico-economic logic that sees a different, monetary value of the Hills’.Footnote7 Such an argument is comparable to the Mola case, where the chief and his subjects hold conflicting forms of knowledge regarding the enactment of rain-petitioning ceremonies as well as their entanglement with chiefly authority. Such conflicting forms of knowledge, I argue, result in different interpretations of the calamities experienced in the area, with the chief blaming his subjects, and vice versa, for not doing things right. Such a blame game is often played by different actors to legitimise or delegitimise the authority of the current chief. It is also about forcing the chief to do ‘the right things’. Some local people claim that he is illegitimate, while he speaks of himself as legitimate and also respectful and fearful of ancestors. This is indicative of conflictual pluralism of traditional knowledge in communities which has been identified in other regions as well.Footnote8 As Mario Blaser argued, environmental conflicts or situations of contested ecologies are caused partly by divergence between the ways of knowing the environment (and its entangled relations with the spirits).Footnote9

There are emerging studies about the complexities of knowledge production on customary authority and their resultant effects across sub-Saharan Africa,Footnote10 and here I draw on these arguments. It has been suggested that current confusions and contestations about traditional authority are a colonial legacy.Footnote11 In the Tonga case, before colonialism the society was amorphous, and the office of the chief was introduced by the colonists for convenience of administration.Footnote12 Colonists saw the chief’s role as being a political authority, while overlooking ritual, medicinal and spiritual aspects of the role. Today, chiefs and subjects often contest the definitions of chieftainship. In some contexts, chiefs maintain the modern stance created by colonists and, in doing so, they conflict with the commoners who expect chiefs to do more, including playing spiritual, religious, cultural, ritual and medicinal roles.

The chief is often perceived as ‘modern’ as he sometimes justifies his reluctance to ‘properly’ follow tradition through ‘modern’ thinking and laws. At times, he speaks of tradition through the idioms of modernity. Here we see how modernity is validated by the chief as he downplays the importance of tradition. Such reliance on modernity perpetuates the core acts of its totalising influence on African traditions.Footnote13 Although we are in a postcolonial age, modernity introduced by the coloniser still retains a measure of significance as it is sometimes used as a point of reference in justifying the failure to follow tradition. As noted below, the chief also adopts traditional ways of enacting rain-petition ceremonies as dictated by the Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF) government, with the aim of showing allegiance to the ruling party. These government-initiated ceremonies are locally known as mazambangulwe. He wants to be recognised by ZANU–PF and receive incentives, including cars, that the government offers to chiefs in the country. As Christian Lund writes, governments and the chieftaincy institution often forge alliances to constitute authority and political control.Footnote14 In this case, Chief Mola has to abandon local rain-petitioning ceremonies and lead the ones initiated by the government, which are highly political and which local people consider to be ZANU–PF’s political mobilisation strategy. Sometimes mazambangulwe are taken to replace or represent the local rain-petitioning activities by the chief, but the local people heavily criticise this. The two camps admit that droughts can be minimised by enacting rituals, but they do not agree on which ones to perform. The understanding is that since droughts are caused by ancestors, scientific cloud seeding cannot bring rain: droughts can only be averted by recourse to ‘traditional’ ceremonies.Footnote15

Droughts and the Rebellious Behaviour of the Chief

On 13 December 2021, in the afternoon, I was coming from Dhobe village, where I had conducted focus group discussions with the elders and face-to-face interviews with village heads. As I was returning home from the shopping centre, I met Oliver Mola, an uncle to Clifford Chalibamba, who hosted me during my stay in the chiefdom. He offered to accompany me home. The distance from the shopping centre to the homestead was 2.5 kilometres. As we were walking, we passed two local dry streams, known as Chiwonzola and Nabhole, that were once perennial. He told me that they grew up playing, swimming and fishing in these streams, as Mola was isolated and had few entertainment activities. He ascribed this dryness to ancestral rage induced by the chief’s behaviour: the chief was not petitioning for rains from the angry ancestral spirits, and spirits were believed to be central to these problems. Consistently, spirits are known to leverage local politics and decision-making in some parts of Zimbabwe, as reported by such scholars as Marja SpierenburgFootnote16 and Joost Fontein.Footnote17 But an alternative perception, as I observed and was told by others, would be that these streams are no longer perennial probably because of the small dams that were built further upstream, and this is compounded by extreme-heat weather patterns experienced in the region since the 2010s.

It is only during rainy seasons that water flows in these stream beds. I had crossed these streams during my previous visits. Although some parts of the channels were dry at the time, I could see water in some areas. Before this day, I had discussed the drying up of these water resources with other people, but what was interesting in Oliver’s nostalgic narrative was the ways in which he located himself within the landscape. As a child and young adult who grew up in the area with plenty of wetlands that he fished and swam in, he was worried that he (and today’s children) could not do this any more because of one person’s (the chief’s) irresponsible behaviour.

This was in mid December, but it had not rained in Mola, and rain is normally expected in November. The more the days went by without rain, the more people complained about the chief’s rebellious behaviour. Many people had cleared their fields but had not planted anything, as they were waiting for the rains. Many people were despondent. However, I saw other families sowing their seeds of such crops as zipoka (maize), maila (millet) and nzembwe (groundnuts) under the soils. When I asked them why they were doing that before the rains, they told me: ‘[w]hen the rain comes, it will find the seeds already underground’. Even though they knew that their region does not receive good rainfall, they had hope that it would rain. Many others avoided this strategy because they were unsure whether it was going to rain or not, since ‘ancestors were angry’. They feared that if they planted their seeds before the rain, they could dry up, or birds or termites would eat the seeds. As one old man remarked: ‘I have very few maize seeds, I do not want to risk them … they [government or non-governmental organisations] are not coming back to give us more seeds’. The fear was not only about the drying up of seeds, but also about worsening hunger and poverty that would result because of that. Such fears pushed people to challenge the chief.

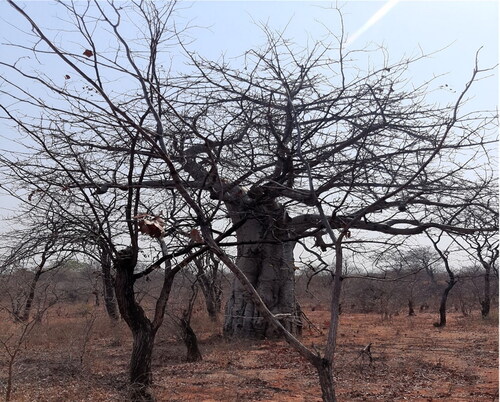

According to Tonga tradition, a reigning chief should organise and take the lead in rain petitioning. This includes arranging the collection of sorghum from all homesteads that is used to brew beer (known as lwiindi) and setting the date for the ceremonies (in consultation with local spirit mediums). The rituals are held at full moon in November, normally after the first rains. In addition, the ceremonies are held at the chief’s palace throughout the night accompanied by singing, dancing and drinking beer. The next morning the chief, ritual wives and local senior spirit mediums are expected to visit malende shrines where they throw libations, clap hands and proclaim all the clan praises, asking for rain from the ancestors. The malende shrine () is located close to the sub-office and shopping centre right in the middle of the chiefdom, but it is not as significant as the small malende that I was also shown, which is dedicated to wives of former chiefs.

Among the Tonga, malende are areas where all past chiefs are buried. Each of the malende in Mola is marked by the presence of a huge baobab tree. These former chiefs are considered communal ancestors and were rainmakers (the role that the current chief is reluctant to perform). For this reason, malende are supposed to be approached with awe and respect. As Elizabeth Colson writes, there is a set of rules governing the approaching of shrines of the land.Footnote18 In the case of the Tonga of Mola, pregnant women must not approach malende, otherwise they bear toothless children; young girls should avoid them, as they may become barren; and the cutting down of trees and herding of livestock around malende shrines is a taboo that may result in serious misfortunes. Also, the spirit mediums should regularly clean the malende and clear all grasses growing under and near to it. Fontein reports a comparable situation in which the Karanga avoid washing clay pots using soap nearer to sacred waters as this may anger njuzu (mermaids) and may have grave consequences.Footnote19

Currently, no one among the Tonga of Mola approaches the malende with awe or respect, let alone the one dedicated to ritual wives. No one is concerned about the associated serious consequences, largely because the places are not used for their intended purposes and have become ordinary places just like many other spaces with baobab trees. I personally, as an outsider, passed through the area many times as it was the shortest route to and from the shopping centre. No recognisable misfortunes (such as sickness) befell me. If people repeatedly disrespect sacred places, they become desacralised over time. This has also been the case in some parts of Zambia, where inconsistency in conducting ceremonies, coupled with environmental degradation, has contributed to the desacralisation of places of power, and it is considered that ancestors have abandoned their people, who are now experiencing serious problems.Footnote20 I saw the malende pictures taken back in the early 1990s before the current chief came into office. The pictures are in JoAnn McGregor’s and Pamela Reynolds and Colleen Crawford-Cousins’s books.Footnote21 I noticed that at that time the shrines used to be cleaned, grass in the surroundings was often cut and there were tiny tsakas (huts) representing all the chiefs that reigned in the Zambezi Valley. Furthermore, ritual wives no longer participate in the rainmaking ceremonies because the chief is not leading in this regard. In addition, for these wives to become recognised ritual wives, the chief was supposed to have sexual intercourse with them as part of his coronation, which he refused to do. I will return to this point later.

The mazambangulwe ceremonies that the chief now conducts at his palace and which he claims have replaced the traditional rain-petitioning rituals do not involve any pilgrimage to malende, the sacred space upon which he fears encroaching. Local elders told me that he fears encroaching on malende because he may die. Currently, nobody collects rapoko (finger millet) and sorghum for beer brewing. The chief only enacts mazambangulwe using donations from the government.Footnote22 Mazambangulwe are countrywide national bira (beer brewing ceremonies) initiated by the government for the first time in 2005 but organised locally by individual chiefs. They were meant to address the several droughts experienced in the early 2000s immediately after the introduction of the government’s fast-track land reform programme, but they have had an impact on the local ways of enacting ceremonies, particularly in a Mola context. These bira ceremonies, as Fontein writes, ‘point exactly to the entanglement of local and national regimes of rule within localised performances of sovereignty and legitimacy linked to rainmaking’.Footnote23 They also demonstrate the allegiance of many local chiefs to the ruling party, ZANU–PF, thereby ‘illustrating how political, religious and meteorological fortunes are often intertwined’.Footnote24

Human–Animal Conflicts and the Angry Ancestors

Another calamity bedevilling the people of Mola, also linked to the irresponsible behaviour of the chief and ancestral rage, is animal attacks on humans and livestock. The prevalence of human–wildlife conflict in the Zambezi Valley is the subject of a substantial literature. Previous scholars have mainly focused on the impact of human–wildlife conflict on the lives and livelihoods of the people.Footnote25 Others have focused on the distribution of conflicts in terms of age, gender, seasons and activity when attacked.Footnote26 While important, these impact studies are limited: they downplay human agency and offer little in terms of understanding local perceptions and the spiritual connotations of such conflicts. To the best of my knowledge, studies focusing on the interlinkages between human–animal conflicts and religious interpretations in the Middle Zambezi Valley are scant. Further downstream the Zambezi in Mbire, a study by Steven Matema and Jens Andersson focused on people’s interpretations and social commentary of conflicts. Social commentary blamed the increased attacks by lions on changes in the governance of wildlife.Footnote27 In contrast, here, I offer a nuanced account of religious interpretations of conflicts in Mola chiefdom. Rather than merely documenting impact, I describe the ways in which animal attacks are spiritually interpreted to invalidate current political authority. Arguably, human–wildlife conflict is a phenomenon whose impact transcends socio-economic impact, but significantly shapes relations and politics in this region.

Mola is adjacent to Matusadonha National Park, which exposes its residents to wildlife attacks. People tend to share space and paths with animals, resulting in conflict. Specifically, animals encroach upon people’s homesteads and humans encroach upon the lake for fishing and on the bush for fruit gathering, poaching, fetching of firewood and when travelling on foot for long distances. Rivers are drying up, animal habitat is lost and natural food in the wild is becoming depleted, culminating in animal encroachment upon the people’s homesteads for survival. As one woman remarked, ‘animals’ “livelihoods” are within the people’s homesteads’. This means that animals now survive by encroaching on people’s farms and gardens as well as preying on humans and livestock. The bush no longer sustainably offers food, shelter and water to the animals.

Human–wildlife conflict is not a recent phenomenon in Mola, though. In her field diary written between 1984 and 1985, my colleague Pamela Reynolds, the first anthropologist to study the Tonga of Mola, Zimbabwe, recorded nearly 40 accounts of human–wildlife conflicts resulting from attacks by such animals as elephant, buffalo and birds.Footnote28 Although people were attacked, the situation was not as serious as it is now. Livestock were mostly attacked while foraging in bush far from people’s homesteads. Today, some people fear and complain more about these attacks because they are escalating. The connection between these problems with the angry ancestors exacerbates fear in some people. Protracted fear was a source of frustration for most of the villagers with whom I interacted. Consequently, they are developing negative attitudes towards animals, which is a threat to animal conservation.

In Mola chiefdom, human–wildlife conflicts occur every day; Quegas Mutale and Taruvinga Muzingili call this ‘the greatest challenge within Tonga communities’.Footnote29 In my field diary that I kept from September 2021 to February 2022, I recorded at least one incident of human–wildlife conflict each day, including lion and hyena predation on livestock, and sightings of predators or their paw prints. At the same time, the community guardians of Wildlife Conservation Action (WCA) frequently reported the same problems and were busy donating mobile bomasFootnote30 to villagers to conceal cattle kraals from predators at night (see ).Footnote31 I consider the sightings of predators and paw prints within homesteads to be incidents of conflict because of the negative impact they had on villagers, as well as myself. In most cases, for instance, I avoided moving around villages or conducting fieldwork in areas where predators and paw prints were most encountered. One morning, paw prints were seen in the homestead close to ‘ours’ and for this reason I spent two days at home due to fear. It is indicative of how ethnography can be shaped by landscapes of human–wildlife conflict and drought. Socio-economic and political events within the areas where fieldwork is enacted also seriously impact on ethnographic research designs.

In narrating the occurrence of these spiritualised conflicts, one of the local elders, who is possessed by a mhondolo (lion spirit), told me that:

Nowadays the ancestors are very angry. Lions now roam around the villages day and night because we are not propitiating them. These lions are angry ancestors. The current chief is not honouring our ancestors. We no longer receive rains in time because of this … lions attack livestock, especially in the areas where the chief lives. This occurs in that area a lot because the ancestors want to show the chief that they are angry.Footnote32

Different animals caused different problems. Hyenas were preying on goats at night. More people in Mola own goats than cattle because they lack resources to purchase cows, and the area was for a long time a tsetse corridor which discouraged cattle breeding. Goats are a form of wealth. They are used in paying bride price, and for food. Families do not always consume them. They prefer to eat vegetables every day and keep their goats for very important occasions or for the most difficult times. In response to this, villagers fenced their kraals with thorn bushes or sticks to deter predators from entering the kraals. Villagers also monitored their goats (and cattle) towards sunset to make sure they were all in their thorn-fenced kraals. People invested considerable effort due to fear of losing their wealth. According to local accounts, people did not go to so much trouble in the past. Sometimes they would let their goats spend the night outside the kraals but in their yards. Doing this increases demand for labour in the homesteads, and it is mostly children that are tasked with this duty. On 17 November 2021 at around 6 p.m., I, together with Clifford’s three children, were sitting in our homestead, when Village Head Chalibamba passed by looking for his missing goat. We had the following conversation:

Village Head Chalibamba: Mbiyeni mbiyeni, Kutya (Hello hello, Kutya).

Researcher: Hi there.

Village Head Chalibamba: I cannot see one of my goats, white in colour, a male one. So I am looking for it. I want to ask these kids if they have seen it. I am scared that it may be attacked by predators at night. These days our ancestors have forsaken us. We are losing a lot of our wealth to these predators.

Researcher: Okay, let me ask one of these kids to check in our kraal to see if it is there or not …. He has just checked, it is not there, you may want to check in other homesteads or in the bush.

Village Head Chalibamba: Thank you Kutya, let me go and check in homesteads across the stream.Footnote33

Although hyenas caused challenges for goat owners, lions were considered to be the most problematic. Cattle were killed and wounded by lions. Meat from the cattle killed was sold locally, with some of it retained by the owners for subsistence. Wounded cattle were slaughtered and sold as well. Lions also attacked people. On one sad occasion, a man who was travelling on a motorcycle from Mola to Bumi Hills was attacked and killed by lions. The mysterious behaviour of lions at the time resulted in people seeing them as something other than lions: because they were behaving in an unusual manner and roaming around people’s communities every night, they were at times interpreted as the embodiment of witches or ancestors, and no longer seen as ‘normal’ lions. Similarly, in Mbire district in 2010, lions caused havoc in communities to the extent that people interpreted them religiously as ‘spirit lions’.Footnote35 In the distant past, as Shaurabh Anand and Sindhu Radhakrishna write, ancestral spirits moved around in the form of lions and predated on humans.Footnote36 In many riverine communities, witches (and spirits) are consistently believed to move around in the form of crocodiles and kill people.Footnote37

Why Does the Chief Avoid Conducting the Rainmaking Ceremonies?

According to local people, the chief’s avoidance of engaging in rain petitioning is at the root of the calamities experienced today. This is one form of knowledge regarding authority and legitimacy in Mola that is held by the subjects. The chief is said to have bypassed major traditional coronation procedures, which is why the ancestors are believed to be angry with him. To avoid grave consequences that may befall him, he avoids encroaching upon the sacred places dedicated to them. Thus, on these grounds local people argue that the chief may be as sceptical of his own legitimacy and authority as are the local people.

Once the matrilineal heir to the throne is identified, he must spend seven days in the forests. If he comes back alive, he is approved by the ancestors. But if he dies, or is attacked by lions or disappears, it means that they do not approve of him. In 2016, my colleague Felix Tombindo was also told this. He reports that Chief Mola did not go through the traditional procedure of coronation, which involves being

taken without notice when they [local spirit mediums at the behest of ancestors] want to make you the new chief. They ambush and catch you at night and clothe you with a string of beads; they take you to a forest and leave you there. It is a taboo for you to run away. Elephants, lions and other dangerous animals will be roaming around you. You will be sheltered in a musasa [a makeshift habitat] and it is required of you to spend seven days in the forest [where the animals do not attack you if you are the rightful heir].Footnote38

Many of the elders with whom I interacted confirm this. I also interviewed Chief Mola to hear his side of the story, and he told me quite the opposite, in the following words:

When I became chief, I slept at the malende shrine for seven days. Elephants could come at night, but they could not attack me. I could see them. This shows that I was the rightful candidate for the position. Chieftainship is not just inherited, you have to go through this process.Footnote39

When he returns from the bush, the chief must have sexual intercourse with all the former chief’s wives. The former chief had two ritual wives that the current chief was supposed to have sex with, but he refused, arguing that they were too old to consent. Here the chief invoked modern ‘laws’, shunning tradition that forces women to sleep with men for cultural reasons. Instead, he demanded to be given a very young girl (13 years old) to have sex with. Members of the community claim that this was a rape case that was never brought to trial. This act also denied the young girl access to education (and other teenage rights). This young girl is now old, and she is the third wife to the chief. The chief’s take on modernity appears to be subjective and selectively applied. In the case of the young girl he took as his wife, he did not obey modern laws.

In addition to these processes, there is also the ceremony itself to which every member of the community is invited to celebrate the appointment of the new chief. The chief did participate in this; however, when he was appointed, several disputes arose. Some men among his kin wanted to dethrone him, claiming that he was not the rightful heir. One young man informed me:

When the current chief got into power there were serious problems. There were people who wanted to kill him through malicious means. People sent bees to attack him while he was at his home, but the bees did not sting him because he had been given powers to protect himself by n’angas [diviners].Footnote40

When I became Chief Mola, there were conflicts. There were people who had connections working in government as policemen and correctional officers. They did not want me to become chief. They were powerful. They wanted to grab the office from me, the rightful heir … these people are now dead because they were acting against the will of the ancestors. They just wanted to be chiefs without even going to sleep at malende [rain shrines] for seven days.Footnote41

The young man’s narrative is indicative of the entanglement between succession and witchcraft in Tonga communities. The chief told me that those who wanted to dethrone him died as a result of the ancestors’ wrath, but some people in the chiefdom told me that the chief bewitched these people, as they died one by one immediately after his coronation. The successive nature of these deaths is considered mysterious enough to have been caused by witchcraft.

Furthermore, the chief is believed not to follow tradition because he is modern. This perception of his modernity stems from the fact he worked as a driver at the District Development Fund for many years. One elder explained to me that

all these problems we face today can be stopped if only our chief does the right thing …. He does not appease the spirits and ancestors and those who are underground. He is an English [modern] chief. Right now, our customs and traditions are disappearing. Ancestors are angry …; animals are eating people and cattle … we used to engage in many ceremonies using traditional methods, but this is not happening anymore. We used to engage in ceremonies such as masabe [alien] spirits rituals with the playing of nyele [kudu horns], but this does not happen anymore. These days many people do not play nyele and the young do not know how to play them. We are no longer connected to our ancestors as before.Footnote42

The interviewees’ opinions emphasise the disappearing of tradition and the overriding influence of modernity as all being encapsulated in the bad behaviour of the chief. Many elders told me that the young do not know what tradition is because it is not practised. Of course, I noticed that the young barely talk about the importance of tradition, let alone engage in it.

The Waning of the Chief’s Authority

Competing forms of knowledge between the chief and his subjects regarding the coronation and the chief’s authority have mixed effects for the conflicting camps. In the comparable Nharira Hills case presented by Morreira and Iliff, different forms of knowledge held by different regimes of authority have resulted in court cases. Here, I focus on how such different forms of knowledge have an impact on the chief’s authority. The persistence of drought-induced calamities is inducing the waning of the power and authority of the chief. As Fontein writes:

It is good rains, at the right time, in sufficient quantities, and not destructive of crops or houses, that can signify the legitimacy of chiefs, clans, mediums, and the moral wellbeing of community, government, or even the state at large. Bad rains, or no rain at all, question such claims to legitimacy, even as they demonstrate perhaps most forcefully the ultimate sovereignty of the ancestors and of [God], as owners of the land and the provider of rain respectively.Footnote43

Chief Mola’s loss of legitimacy resembles the case of another Tonga chief, Sinansengwe of Binga, who shunned tradition in favour of Christianity and did not appease the mizimu (ancestors). Instead, he appointed another relative to perform the mizimu rites while he performed administrative functions. To illustrate Chief Sinansengwe’s loss of legitimacy, credibility and respect, his subjects composed traditional buntibe songs in which they publicly expressed their contempt for him. While this highlights the difficulties the chieftaincy system faces, it also demonstrates how the chieftaincy continues to rebrand itself in order to maintain its relevance to modern societal demands.Footnote46 In a Mola context, people have not publicly opposed the chief in such ways; instead, they oppose him by murmuring within the private sphere. This form of opposition takes the character of what James Scott referred to as ‘hidden transcripts’.Footnote47 The idea of hidden transcripts explains a situation whereby the subjects are aware of the wrongs of their leaders but fear revealing them in public. Revealing the wrongs of leaders in public creates tensions between chiefs and their people. Since chiefs control the distribution of food aid in Mola, people avoid creating tensions with them as it may result in their removal from the list of beneficiaries. Understood in the impoverishment context of many Tonga, no one risks having his or her name removed from the list of beneficiaries, so everyone maintains good relations with the chief. As Thomas Sikor and Christian Lund write, access to resources is intimately bound up with the exercise of power and authority.Footnote48 Such a trend, where disobedience against the leaders results in the malefactor being punished by blocking their access to resources, is common in local politics, even at village level. Leaders use their control of resources to enforce compliance among their subjects.

The Chief’s Counter-Narratives

Although the chief is blamed for the current problems, he asserts counter-narratives, making evident the conflictual existence of different forms of knowledge in local politics. I had the privilege of interviewing the chief several times to hear his side of the story and develop a balanced argument. The chief attributes the problems to the bad behaviour of his subjects and that of the neighbouring chiefs. After interviewing the chief, I realised that both the subjects and authorities blame each other whenever there are problems, hence my use of the term ‘blame game’. The chief’s narratives serve to justify events surrounding his coronation and overall legitimacy, which is questioned by many local people. His narratives are also aimed at consolidating his power amid the waning of his authority and loss of respect. Entangled in the chief’s narrative is another version of ancestral causation that is in opposition to that asserted by his people. It seems that both camps invoke the ancestors to authenticate their own perceptions, narratives and interpretations.

First, the chief responded to the issues of human–wildlife conflicts and the anger of ancestors. He blamed his subjects and other neighbouring chiefdoms for this. Regarding his subjects, the chief said that ‘some of our elders here are engaging in abominable activities including having sex with their own daughters; and killing their own children through witchcraft so that they obtain more wealth’. He reiterated that ‘many people were doing such things and this was angering the ancestors’.Footnote49 Indeed, some of the issues the chief was talking about were also confirmed by people, though they did not connect them to angry ancestors and the persistent calamities. For example, a prominent local man was rumoured to have bewitched his own daughter before having sex with her. When the daughter realised this, she was angry with her father. At the time of this research they were not on speaking terms. The same man was believed to have killed one of his sons as a sacrifice in order to gain wealth. According to the chief, such abominations were contaminating nyika (land). Henceforth, the ancestors were discontented and punished people by means of animal attacks and drought.

Furthermore, regarding other chiefdoms, the chief provided a narrative that other elders confirmed, but did not connect to the anger of ancestors. Chief Rare blamed Chief Nyamhunga who through his political connections displaced him from appeasing the ancestors in Lake Kariba. Chief Mola believes that human–wildlife conflicts are taking place because people are not brewing beer according to the traditional Tonga procedures intended to appease the angry ancestors that inhabit the lake. Since independence, the Mola and Musampakaruma reigning chiefs were logistically supported by the district administrator’s office to engage from time to time in ritual ceremonies in the lake. The support included transport and food. Mola and his people had to travel to Kariba town, where the rituals were enacted under the rubric of ‘Nyaminyami festivals’.Footnote50 Through this, Mola and Musampakaruma people obtained some money from the Zambezi River Authority to improve their lives and chiefdoms. Such assistance was considered to be reparations for the ills induced by the displacement and the disconnection of people from their ancestors, whose graves were submerged by the lake.

However, between 2015 and 2021, the Tonga of Mola (and also the Shangwe of Musampakaruma) did not lead ceremonies in the lake, as this prerogative was handed over to Chief Nyamhunga and his Korekore people. The elders I spoke to told me that this was because Chief Nyamhunga was greedy and wanted access to resources in the lake: he had therefore used connections within the ruling party ZANU–PF to culturally displace them from the lake. This coincided with the Tonga’s increasing support for the opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change, which was led by Morgan Tsvangirai. The district administrator, who was a ZANU–PF cadre, then decided to hand over this privilege to Nyamhunga and his Korekore people. The Korekore were also displaced from the Zambezi Valley when the dam was constructed, but evidently the larger part of their former homes was not submerged by the lake. Nowadays the appeasement in the lake is done according to the Korekore tradition, which is believed to anger Tonga ancestors. The chief connected this problem to human–wildlife conflict in the following words:

Lake Kariba is ours, [belonging to us] and the people from Musampakaruma. The lake is for the [Ba]Tonga people and not the Korekore …, the Korekore claim to have been displaced from the areas covered by the lake but this is not true. The Korekore lived far from the lakeside. Their chiefdoms were located near Chirundu. They claim the lake is theirs because they just want fish from the lake. They do not even know the spirits that control the lake and the way they enact the rituals aimed at appeasing the spirits of the lake is wrong. The ancestors are angry. No wonder that you see that many people are drowning in the lake and some are being killed by lions, crocodiles and hippos …. These people are taking the lake from us. Footnote51

Some people say that there are traditional aspects of life that we are not following, but I wonder what these are. We have our shrines here, we carried them with us from the Zambezi, we brought them here. We have other practices we banned here [that were practised in the Valley] because they lacked ‘ubuntu’, such as the killing of twins. Bearing twins was considered a taboo …. We will keep appeasing the ancestors to tell them that we do not want such things so that they do not become angry. Things change, culture is not static. Even the law itself does not permit these things. Hahaha …! [he laughs]. We do rainmaking ceremonies. But some people do not understand how we do them. We now call them mazambangulwe; we do them together with the Tonga in Zambia. If we do mazambangulwe we have done the required yearly rainmaking ceremony. We cannot repeat the things that we have already done. Here in Mola we do not do yearly rainmaking ceremonies because in the past our elders did not do it like that, they only enacted them when there were problems. But with this English [modernity] that came, I am expected to lead rainmaking ceremonies each year. This is how other elders here are getting lost.Footnote52

Conclusions

People in Mola depend significantly on food aid from donors such as World Vision and Save the Children UK because, as a result of animal encroachment and drought, they do not have a sufficient harvest. Aid is not given consistently throughout the year, which leaves many families hungry and poverty-stricken. During the rainy season, dilapidated roads mean that vehicles with food aid cannot reach the area. During elections, ZANU–PF limits the operations of non-governmental organisations in the areas as they fear that villagers might be persuaded to support the opposition. People live in fear not just of animals but of worsening hunger and poverty, as well as losing wealth through livestock predation. Such heightened fear is opposed to my own fear as elucidated in a vignette at the beginning of this article. While residents mostly fear losses and impoverishment resulting from calamities and ancestral rage, I feared being injured or killed by animals. Our nerves were triggered by the same problems, but in different ways. At the same time, it was alleged that the chief was afraid to encroach on malende, sacred shrines, because he feared that ancestors would kill him. His conducting of mazambangulwe indicates that he also feared that his subjects might starve as a result of loss of rainfall and bad relations with ZANU–PF. Evidently, there were and are entangled fears across different actors all encapsulated in the anger of ancestors. Living in and dealing with fear, as shown in the paper, generates competing forms of knowledge.

One key issue in Mola is the shortage of options to solve these problems. Of course, as I have shown in the paper, people have their own reasons for why these problems are occurring, as the varying explanations from different actors and regimes of authority attest. Local people call for the chief to do ‘the right thing’ so that these calamities are brought to an end, but the chief is reluctant to do what they are asking. In fact, he justifies his actions by engaging in mazambangulwe, which are not part of local tradition. Modernity is being embraced by downplaying tradition, and this is the source of problems. A contest between the chief and his subjects is rhetorically a contest between modernity and tradition. In this rhetorical contest both the chief and his subjects deploy the ‘traditional’ and ‘modernity’ terminology to legitimise their respective behaviours and to ascribe blame. The ‘traditional’ and ‘modernity’ dichotomy is loosely used in this context to either legitimise one’s own or delegitimise the next person’s behaviour. The two terms are levers for judging or questioning a person’s behaviour.

I have elucidated the existing and competing forms of traditional knowledge regarding the chieftainship office, from coronation to enactment of ritual. Ancestors and local spirits are entangled in these conflicting knowledges and ascriptions of blame among different actors. Ancestral spirits are levers for asserting different forms of (counter-) narrative. The inclusion of ancestors often legitimises one’s claims and knowledges within these everyday contestations. Each person or group of people tries to distance themself from these problems, or justify their authority, by apportioning blame to others. I have argued that the more the problems worsen, the more people blame each other. An escalating blame game is a reliable lens through which the magnitude of droughts and human–wildlife conflicts can be comprehended at a given time. Both the people and the chief explain these problems from the point of view of ancestral rage. This signifies the centrality of ancestors in the Mola community. Narratives are framed in ways that centralise ancestors as a validation strategy. An understanding of the intersections between droughts, human–wildlife conflicts and ancestors is pertinent in understanding the everyday life in Mola.

Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, The University of Queensland, St Lucia QLD 4072, Brisbane, Australia. Email: [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9709-9005

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was funded by the Sandisa Imbewu Scholarship from Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa and the Humanities and Social Science Internal Research Grant Scheme at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia, under grant number 2021-2OS-HDR-0004. I want to thank Professor Thayer Scudder and Professor Chris de Wet, who have read and commented on my fieldnotes and drafts of this paper. My PhD supervisors Dr Brooke Wilmsen, Dr Nicholas Herriman and Dr Thomas McNamara have supported me throughout my academic journey and commented on parts of this article. I would like to thank the people from Mola chiefdom, with whom I have worked since 2017, for engaging with me in knowledge production. Gratitude also goes to the Journal of Southern African Studies editors and two anonymous reviewers who provided me with very constructive feedback.

Notes

1 S.B. Manyena, ‘Ethnic Identity, Agency and Development: The Case of the Zimbabwean Tonga’, in L. Cliggett and V. Bond (eds), Tonga Timeline: Appraising Sixty Years of Multidisciplinary Research in Zambia and Zimbabwe (Lusaka, Lembani Trust, 2013), pp. 25–66; J. Matanzima, ‘Thayer Scudder’s Four Stage Framework, Water Resources Dispossession and Appropriation: The Kariba Case’, International Journal of Water Resources Development, 38, 2 (2022), pp. 322–45; J. Matanzima and U. Saidi, ‘Landscape, Belonging & Identity in North-West Zimbabwe: A Semiotic Analysis’, African Identities, 18, 1–2 (2020), pp. 233–51.

2 J. Matanzima and I. Marowa, ‘Human–Wildlife Conflict and Precarious Livelihoods of the Tonga-Speaking People of North-Western Zimbabwe’, in K. Helliker, P. Chadambuka and J. Matanzima (eds), Livelihoods of Ethnic Minorities in Rural Zimbabwe (Cham, Springer, 2022), pp. 107–22; J. Matanzima, I. Marowa and T. Nhiwatiwa, ‘Negative Human–Crocodile Interactions in Kariba, Zimbabwe: Data to Support Potential Mitigation Strategies’, Oryx, 57, 4 (2023), pp. 452–6; I. Marowa, J. Matanzima and T. Nhiwatiwa, ‘Interactions Between Humans, Crocodiles, and Hippos at Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe’, Human–Wildlife Interactions, 15, 1 (2021), pp. 212–27.

3 M. Thorn, M. Green, K. Marnewick and D. Scott, ‘Determinants of Attitudes to Carnivores: Implications for Mitigating Human–Carnivore Conflict on South African Farmland’, Oryx, 49, 2 (2015), pp. 270–7; J. McGregor, ‘Crocodile Crimes: People Versus Wildlife and the Politics of Postcolonial Conservation on Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe’, Geoforum, 36, 3 (2005), pp. 353–69.

4 J. Matanzima and K. Helliker, ‘Contextualizing Tonga Lives and Livelihoods in Zimbabwe’, in K. Helliker and J. Matanzima (eds), Tonga Livelihoods in Rural Zimbabwe (Abingdon, Routledge, 2023), pp. 1–22.

5 F. Tombindo and S. Gukurume, ‘Resource Access, Livelihoods and Belonging Amongst the Tonga in Mola, Nyaminyami District’, in Helliker and Matanzima, Tonga Livelihoods in Rural Zimbabwe, pp. 84–98.

6 S. Morreira and F. Iliff, ‘Sacred Spaces, Legal Claims: Competing Claims for Legitimate Knowledge and Authority over the Use of Land in Nharira Hills, Zimbabwe’, in A.S. Steinforth, S Klocke-Daffa (eds), Challenging Authorities: Ethnographies of Legitimacy and Power in Eastern and Southern Africa (Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), pp. 293–316.

7 Ibid., p. 294.

8 See for example the cases presented in L. Green (ed.), Contested Ecologies: Dialogues in the South on Nature and Knowledge (Cape Town, HSRC Press, 2013).

9 M. Blaser, ‘Notes Towards a Political Ontology of “Environmental” Conflicts’, in L. Green, Contested Ecologies, pp. 13–27.

10 L. Nkomo, ‘Winds of Small Change: Chiefs, Chiefly Powers, Evolving Politics and the State in Zimbabwe, 1985–1999’, Southern Journal for Contemporary History, 45, 2 (2020), pp. 152–80; C. Rassool, ‘Power, Knowledge and the Politics of Public Pasts’, African Studies, 69, 1 (2010), pp. 79–101; J. Verweijen and V. Van Bockhaven, ‘Revisiting Colonial Legacies in Knowledge Production on Customary Authority in Central and East Africa’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14, 1 (2010), pp. 1–23.

11 Ibid.

12 T. Scudder, The Ecology of the Gwembe Tonga (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1962); E. Colson, The Social Organisation of the Gwembe Tonga (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1960).

13 W. Mignolo, The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Durham, Duke University Press, 2011); S.J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘The Cognitive Empire, Politics of Knowledge and African Intellectual Productions: Reflections on Struggles for Epistemic Freedom and Resurgence of Decolonisation in the Twenty-First Century’, Third World Quarterly, 42, 5 (2021), pp. 882–901.

14 C. Lund, ‘Twilight Institutions: Public Authority and Local Politics in Africa’, Development and Change, 37, 4 (2006), pp. 685–705.

15 A. Nhemachena, ‘Are Petitioners Makers of Rain? Rains, Worlds and Survival in Conflict-Torn Buhera, Zimbabwe’, in L. Green, Contested Ecologies, p. 110.

16 M. Spierenburg, Strangers, Spirits, and Land Reforms: Conflicts about Land in Dande, Northern Zimbabwe (Leiden, Brill, 2004).

17 J. Fontein, Remaking Mutirikwi: Landscape, Water and Belonging in Southern Zimbabwe (Oxford, James Currey, 2015).

18 E. Colson, ‘Places of Power and Shrines of the Land’, Paideuma, 43, 1 (1997), pp. 47–57.

19 J. Fontein, Remaking Mutirikwi.

20 L. Siwila, ‘An Encroachment of Ecological Sacred Sites and its Threat to the Interconnectedness of the Sacred Rituals: A Case Study of the Tonga People in the Gwembe Valley’, Journal for the Study of Religion, 28, 2 (2015), pp. 138–52.

21 J. McGregor, Crossing the Zambezi: The Politics of Landscape on a Central African Frontier (Oxford, James Currey, 2009); P. Reynolds and C. Crawford Cousins, Lwaano Lwanyika: Tonga Book of the Earth (Harare, C.C. Cousins in association with Save the Children (UK), 1989).

22 Interview with the Chief’s wife, Mumenyi, 21 November 2021.

23 Fontein, Remaking Mutirikwi, p. 82.

24 Ibid.

25 C.G. Dhodho, ‘Letting Them Starve: The 2008 Food Crisis and Marginalisation of the Tonga of Binga in Zimbabwe’, in Helliker, Chadambuka and Matanzima, Livelihoods of Ethnic Minorities in Rural Zimbabwe, pp. 157–71; L. Jeke, ‘Human-Wildlife Coexistence in Omay Communal Land, Nyaminyami Rural District Council in Zimbabwe’, Mediterranean Journal of Social Science, 5, 20 (2014), pp. 809–18.

26 Matanzima, Marowa and Nhiwatiwa, ‘Negative Human–Crocodile Interactions’.

27 S. Matema and J. Andersson, ‘Why Are Lions Killing Us? Human–Wildlife Conflict and Social Discontent in Mbire District, Northern Zimbabwe’, Journal of Modern African Studies, 53, 1 (2015), pp. 93–120.

28 P. Reynolds, The Uncaring Intricate World: A Field Diary, Zambezi Valley, 1984-1985 (Durham, Duke University Press, 2019).

29 Q. Mutale and T. Muzingili, ‘Addressing Vulnerability of Crop Farmers to Climate Change through Flood Plain Cultivation (Bbonzye) in Luunga, Binga’, in Helliker and Matanzima, Tonga Livelihoods in Rural Zimbabwe, pp. 25–39.

30 Bomas are livestock enclosures, in this case used to cover kraals in order to protect cattle from predator attacks at night.

31 WCA is a non-governmental organisation which promotes co-existence between people and animals and animal conservation in several Zimbabwe rural areas, including Mola.

32 Interview with Time Gwangwaba, 17 November 2021.

33 Informal conversation with Village Head Chalibamba, 17 November 2021.

34 D. Mwamidi, S. Mwasi and A. Nunow, ‘The Use of Indigenous Knowledge in Minimizing Human-Wildlife Conflict: The case of Taita Community, Kenya’, International Journal of Current Research, 4, 2 (2012), p. 28.

35 Matema and Andersson, ‘Why are Lions Killing Us?’

36 S. Anand and S. Radhakrishna, ‘Investigating Trends in Human-Wildlife Conflict: Is Conflict Escalation Real or Imagined?’, Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 10, 2 (2017), pp. 154–61.

37 J. McGregor, ‘Crocodile Crimes’; S. Pooley, ‘A Cultural Herpetology of Nile Crocodiles in Africa’, Conservation & Society, 14, 4 (2016), pp. 391–405.

38 An interviewee cited in F. Tombindo, ‘Landscape and Belonging in Mola, Nyaminyami District, Zimbabwe’ (Master’s thesis, Rhodes University, 2017), p. 89.

39 Interview with Chief Mola, 1 October 2021.

40 Informal discussion with Lloyd Nyuni, 25 November 2021.

41 Interview with Chief Mola, 1 October 2021.

42 Interview with Kevious, 1 October 2021.

43 Fontein, Remaking Mutirikwi, p. 85.

44 T. Takuva, ‘“Rains Come from the Gods!”: Anthropocene and the History of Rainmaking Rituals in Zimbabwe with Reference to Mberengwa District, c.1890–2000’, South African Historical Journal, 73, 1 (2021), pp. 138–61.

45 Focus group discussion with elders, 3 October 2021.

46 S.B. Manyena, ‘Disaster Resilience: A Question of “Multiple Faces” and “Multiple Spaces”?’, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 8, 2 (2014), pp. 1–9.

47 J. Scott, Domination and the Art of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1990).

48 T. Sikor and C. Lund, ‘Access and Property: A Question of Power and Authority’, Development and Change, 40, 1 (2009), pp. 1–22.

49 Interview with Chief Mola, 1 June 2017

50 Matanzima, ‘Thayer Scudder’s Four Stage Framework’.

51 Interview with Chief Mola, 1 June 2017.

52 Interview with Chief Mola, 1 October 2021. ‘English’ here is used to mean modernity. The word ‘English’ is deliberately used to mean modernity in local terminology.