ABSTRACT

A college of education established a research-based framework, Principled Innovation (PI), to support education professionals to consider the role character plays when innovating. Three instructors who authored this study integrated the four assets and eight practices of the PI framework into their courses and wanted to support one another in identifying bright spots for how PI was used and expanding upon them. They used a protocol they created, the Appreciative Tuning Protocol (ATP), to help one another expand on their original efforts. This study involved a triangulated, qualitative review of the three ATP meeting transcripts, natural artifacts from the courses, and their reflections. Findings revealed that all three instructors were successful in integrating PI, that all three instructors decided to integrate PI implicitly by applying the PI assets and practices in activities, and that PI supported the course learning objectives in all courses. This study has implications for other instructors who wish to utilize PI in their courses. Research is needed to determine how PI can be integrated into other higher education topics and whether the addition of PI can impact student achievement.

In a large college of education in the southwestern area of the United States, the incoming dean wanted to find a way to support educators in their mission to innovate, and to help them consider morals and character in doing so. The dean held a series of conversations with college stakeholders and asked them, ‘Just because we can innovate, should we?’ and ‘What could it mean for a college of education at a public university to integrate a character education framework into the systems of teacher and leader preparation?’ (Foulger et al., Citation2021). The college received a grant to develop the Principled Innovation (PI) framework and to support its adoption. After refinement meetings with stakeholder groups and researchers, the college felt PI was ready for innovative educators who function in various aspects of educational systems, including instructors in the college, to apply it themselves, in their work, and to use it to support students and others in developing their character.

A workshop was conducted by the PI staff to teach faculty who taught in the same online (undergraduate) degree program about the PI framework and to support them to explore how PI might be integrated into courses. The major outcome of the degree is that graduates effectively use educational theory in the examination and design of pedagogy, educational activities, and learning environments, and can initiate innovations and support change (Foulger et al., Citation2021). By the end of the workshop, the three instructors who authored this study had successfully re-designed one area in their course to integrate the PI framework in ways they felt supported the curriculum. They were excited about the possibilities they had already experienced. However, they fully realized this first experience with integrating PI was experimental, setting the stage for making improvements in the future.

Consequently, they sought an efficient means for supporting each other to foster progress toward the deeper integration of the PI framework. As such, they decided to combine two protocols from the literature, Appreciative Inquiry (Fredrickson, Citation2003; Mohr & Watkins, Citation2002; Stavros et al., Citation2015, Citation2018) and Tuning (Paulsen et al., Citation2016; Schon, Citation1984; Thompson & Pascal, Citation2012). The result was a collaborative experience they call the Appreciative Tuning Protocol (ATP), a 30-minute, outcome-oriented, agenda-driven meeting to help the hosting instructor (a) identify promising areas of their course where the PI framework was working well (i.e., the appreciative component) and to support one another to (b) brainstorm and think through how a promising area might be expanded (i.e., the tuning component). The ATP meeting (see agenda template in the Appendix) provided an experience-based roadmap for this work. The outcome of each ATP meeting was a bright spot—their term for a promising area where PI was represented well—and a list of ways the bright spot could be expanded. Then, after the meetings, each instructor composed a reflection, outlining their detailed plans to expand the identified bright spot.

The protocol showed promise in helping the instructors more expediently address the practice gap related to the integration of PI. Consequently, the authors of this study sought to document the result of how the PI framework was integrated into their pre-existing courses. The following research questions guided the inquiry:

How did the instructors decide to include the PI framework in their courses?

How did the PI framework relate to or enhance the pre-existing course content?

Character development in higher education

Hackett and Wang (Citation2012) contend that virtues are contextually defined—that a person acquires character traits by repetitively practicing them in real-life settings until they are developed into a habit. Students in institutes of higher education (IHE) who are in the early years of their adulthood naturally experience changes in character and moral opinion as they engage with diverse peers, are exposed to new ideas and contexts, and are immersed in a learning setting over a long period of time (Nagashima & Gibbs, Citation2022). But, leaving the development of students’ character to happenstance—to coincidence as a learning model—is inadequate for what could be the most important human development need.

Conversations about how character is developed extend as far back as Aristotle and Confucius in the 6th Century B.C. (Althof & Berkowitz, Citation2006). Throughout history, IHE have attempted different methods for developing students’ character (Bara, Citation2015). Starting in 1810, at the University of Berlin, Humboldt (Bara, Citation2015), advocated for ‘bildung,’ the marrying of education with morals to create productive citizens. Then, in the 1850s, Cardinal John Henry Newman, the founder of the University of Dublin, instigated the adoption of high academic principles coupled with character development that went beyond the previous reliance on the teachings of the Catholic Church (Bara, Citation2015). Later, Newman suggested that universities should include a mix of theology and science, allowing for the representation of morals, values, and character in coursework. At the University of Madrid, Jose Ortega Y Gasset advocated for IHE to educate students so that they can be tools of social change (Bara, Citation2015). Gasset’s proposition outlined the important connection character could play in ensuring learners graduate with a sense of purpose that would allow them to contribute positively to their communities.

When the priority exists, researchers have shown that educational systems that view character as integral to the work of teaching and learning and that seek to develop character through lived experiences have the potential to impact students’ identities (Althof & Berkowitz, Citation2006; Lamb et al., Citation2021). However, since an authoritative definition for character does not exist, and since virtues of character are also ill defined, IHE have not come to agreement on the most appropriate method (Komives et al., Citation2011; McGrath, Citation2022).

Recognizing the essential need for IHE to address character as core to interactions with students, in 2015, the United Nations recommended that all IHE students, worldwide, should graduate prepared to be positive global citizens, with ‘the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes required by citizens to lead productive lives, make informed decisions and assume active roles locally and globally in facing and resolving global challenges’ (Brooks & Villacís, Citation2023, p. 52). Specifically, the United Nations encouraged faculty in higher education to teach human rights and fundamental freedoms alongside technical and professional skills (Brooks & Villacís, Citation2023), and to address character development as part of students’ higher education learning experiences.

Scholarship about the development of character in IHE

Lawrence Kohlberg (Citation1975) identified six stages of moral development grouped into three main levels: (a) the preconventional level, where individuals make decisions to be obedient and to avoid punishment; (b) the conventional level, where individuals grow to realize relationships, social conventions, and social order are important, and (c) the postconventional or principled level where individuals consider their rights and the rights of others, in order to live by ethics-informed moral principles. In an experiment with young children, Walker (Citation1982) confirmed Kohlberg’s (Citation1975) proposed developmental aspect of character, which suggests that individuals who reach the highest level of moral development are principled—they have effectively passed through prior stages and have learned to act according to their self-chosen ethical principles, which may, at times, transcend societal norms or laws if they conflict with fundamental human rights or justice.

The Oxford Global Leadership Initiative provides character-based leadership training using an Aristotelian approach that focuses on developing the ‘practical wisdom’ needed by future leaders (Lamb et al., Citation2021). In preparing for all types of career responsibilities (for example, social sciences and STEM fields), organizations demand that incoming professionals have a strong sense of ethics and social responsibility (Leydens & Lucena, Citation2018; Riley, Citation2008). Research by Schiff et al. (Citation2020) found that engineering students have more fixed notions of ethics and values, cultivated prior to college, than those in other fields. Scholars suggest that students who do not progress in their character development tend to focus on the technical aspects of their career, tend to remove themselves from social concerns, and have a ‘meritocratic ideology’ that emphasizes hard work over other considerations (Cech, Citation2014; Schiff et al., Citation2020). Implications of non-advancement suggest that teaching approaches include strategies for continual character development (Schiff et al., Citation2020).

Another factor IHE must grapple with is the imposition of values on others when character education is brought up. Philosophers of the modern era, such as Jacques Maritain (Citation1943), have suggested that honoring the individual’s expression of their personal viewpoint and opinion can be beneficial to the development of character. Furthermore, research has found that explicitly addressing concepts such as integrity in IHE can lead to a stronger ethical foundation in students and improved societal trust in graduates (Nafi & Kamaluddin, Citation2019). Some who advocate for including character education in IHE, suggest that innovative approaches to teaching can impart information and cultivate the whole student without imposing institutional definitions of morality or values (Fitzmaurice, Citation2008).

Principled innovation as a character framework in IHE

To support innovative endeavors, the PI framework positions human flourishing because of values-driven choices and decisions (Jubilee Center for Character and Values, Citationn.d.). Additionally, to ensure the PI framework is useful and generalizable to many educational endeavors, our college drew on the work of Shields (Citation2011) who suggested ‘Education should develop intellectual character, moral character, civic character, and performance character, along with the collective character of the school’ (p. 49). College leadership wanted a framework that would align with work from the University of Birmingham, which represents scholarship on character and how character is developed (Jubilee Center for Character and Values, Citationn.d.).

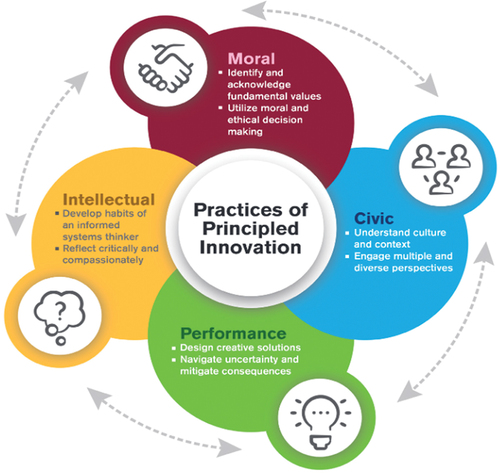

PI considers how intellectual, moral, civic, and performance assets, can be leveraged to shape innovative circumstances. In the PI framework, the four assets are positioned as equally important and interrelated, evenly contributing to the production of ethical standing for innovations. To support the practical use of the framework, our college culled literature to define each asset as specific practices that can help educators operationalize an innovative attempt. See for a visual representation of the PI assets and practices.

While there was no empirical evidence about the use of the PI framework in practice, the scholarship behind the development of character suggests that innovators who consider the eight practices of the PI framework will strengthen their innovation efforts and support those involved to achieve the principled level of their character, as noted by Kohlberg (Citation1975). Further, utilizing the PI framework to support innovations is aligned to findings from research by Shields and Bredemeier (Citation2011) suggesting that character is at the center of successful innovation efforts because innovators (a) treat others with dignity and worth; (b) support the equal rights and opportunities of those involved; (c) support the greater good; and (d) protect and encourage the ‘well-being, liberty, and autonomy of the people’ (Shields & Bredemeier, Citation2011, p. 28). PI was designed to be conceptual in nature and broadly generalizable in any education setting. Although research about using a character attributes framework to improve students’ exhibitions of character (Bryant et al., Citation2016; Keser et al., Citation2022) shed light on the opportunity, when this study commenced, the PI framework was very new to the college—prior examples for how PI could support students in their learning activities did not exist, and the instructors involved in this study were challenged to find meaningful ways to integrate PI into their teaching.

Method

In this study, the researchers used a qualitative approach to provide an in-depth opportunity for analysis (Creswell, Citation2015) of the integration of the PI framework into courses. Many scholars argue that qualitative research that includes various strategies tends to be the strongest (Esterberg, Citation2002, p. 37). Further, a comparative approach allowed researchers to review the uniqueness of each course and the creativity utilized by the three instructors involved in this study as they designed ways to integrate the PI framework. By combining interviews with analysis of course material such as syllabi, assignments, and resources, the researchers could review how the nuances of the context played into their effort (Mik-Meyer, Citation2020). It should be noted that prior to conducting this research, the project was reviewed by the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. The research was deemed to be exempt and could therefore proceed.

Participants

All participants are full-time faculty at a large state university in the southwestern U.S. They are all women who, at the time of the study, ranged in age from early 40s to late 50s. They were all reared in the U.S. As a group, they represent various cultural affiliations with ethnic roots in Europe, the region of the Middle East and North Africa, and North American indigenous populations. The three instructors had been teaching in the program for several years and were familiar with the program outcomes, which were aligned with program goals. Their areas of expertise relate to aspects of education and change in unique ways. The professional profiles of the three instructors and their course content are shown in .

Table 1. Instructor title & expertise, course titles, and course descriptions.

Data collection

Prior to the ATP meetings, the instructors had integrated PI into their courses and had taught the revised version of their courses. As part of the study, the instructors created templated video-based tours of how PI was integrated into their course. The instructors then participated in three virtual ATP meetings to determine bright spots and generate ideas for how a bright spot could be expanded. The meetings were held via Zoom and recorded. The agenda and outcomes were also recorded (see Appendix).

Additionally, documents were collected for analysis purposes. These included course syllabi and assignment-specific artifacts such as directions and evaluation materials. Finally, each instructor wrote a reflection after they participated in the ATP meetings about their planned next steps in expanding the bright spots of PI in their courses. The emphasis of the reflection was to explain the realistic challenges of how integrating PI played out in actual coursework activities and to define next steps in expanding the bright spot.

Once all the data were collected, the researchers used Otter.ai to transcribe each of the 30-minute ATP meeting recordings. Then they reviewed their respective transcripts for accuracy and edited them where inaccurate transcriptions were made. In this way, the researchers reviewed the transcripts, line by line, and there was no loss of data.

Data analysis

After we prepared the data, we used a grounded theory approach to review the data for emergent findings and interpretations (Williams & Moser, Citation2019). We coded the meeting transcripts twice. First, we used open and axial coding to review the themes that emerged, then we used an a priori coding scheme to code the transcripts based on predetermined codes, the assets of the PI framework (Saldana, Citation2013). This allowed for the axial codes to be chunked and examined in order to better understand the extent to which they fit into the PI framework. Combining open, axial, and selective methods ensured a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation, both in terms of the emergent themes and how these themes matched, or did not match, the assets of the PI framework.

Finally, we followed the suggestion from Denzin (Citation2012), that including multiple data sources can be a useful way to corroborate findings and compensate for weaknesses in the data, and Fusch et al. (Citation2018) who suggested that triangulation can add depth to the findings, thereby increasing the study’s validity and reliability. To triangulate the findings from the coding processes, we reviewed course-specific documents, the video tours each instructor created and shared during the ATP meetings, and the instructors’ final reflections.

Open and axial coding

During the first coding experience, the lead author coded the ATP meeting transcripts using a grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990). First, the lead researcher coded the data and reviewed it with the other two co-authors to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the process and to validate the coding scheme. Once the transcripts were coded, axial codes were generated by reviewing the connections between the open codes, which included codes such as: PI integration, community, reflection, professionalism, knowledge-building, communication, values, societal change, theory and practice, and teaching.

Selective coding

During a second pass of the data, researchers used a selective coding process to analyze the meeting transcripts based on the PI framework. This time, the lead author coded the same transcripts using an a priori coding scheme as the core concept with the four assets and practices of the PI framework functioning as the codes. This allowed researchers to ‘elucidate alternative interpretations’ (Savage, Citation2000, p. 1493) from the unique data provided by three separate experiences of the same process and to review the data for PI specifically.

Data triangulation

During the ATP meetings, instructors established an initial plan to expand the bright spot identified in the course. The researchers reviewed their written reflections, which included a detailed explanation of their specific plan to improve the promising area. Reflections emphasized perspectives, plans, and contextual factors. Finally, researchers referenced course-specific artifacts to help them understand the experiences and designs within the actual course environment.

Findings

In review of the findings, it is crucial to emphasize that, throughout the process, the instructors retained complete autonomy over their courses. In doing so, they actively demonstrated their independence and expertise in the course content and delivery. For example, each instructor independently determined how to expand the PI framework based on their knowledge of the unique curriculum in their course. This guaranteed that the integration of PI was tailored to specific course needs. It also ensured that the instructors maintained their authority to make decisions regarding the curriculum in their course. Furthermore, the ATP meetings empowered the instructors’ decision-making, their ability to be decisive about how PI was represented, and their complete autonomy over their course.

In the qualitative analysis of the ATP meeting transcripts and artifacts shown during video-based course tours, three themes emerged: (1) PI was integrated, (2) PI was integrated implicitly, and (3) PI was integrated in ways that supported the learning objectives. The following sections provide an explanation of how the instructors decided to integrate PI into their courses. In the following sections, these three themes and the data that elucidated them are covered in depth.

PI was integrated

It was evident that the instructors were successful with the challenge of integrating PI into their courses after the training. Further, during the ATP discussions, the instructors identified promising areas where they felt a better representation of PI could improve the course. They also brainstormed ways PI could help expand those areas. See for a summary of each instructor’s noted promising area, a list of changes to be made, and the connection to PI.

Table 2. Promising area identification and expansion.

Instructor 1

The instructor shared that the course was designed to help students ‘increase their performance capacity (e.g., the performance practices of PI) through iterative opportunities to advocate, apply collaboration at many levels, and be strategic and creative.’ To do this, the course was designed around the motive for students to start a movement. While the other two instructors re-designed one unit of their course after the PI training, this instructor decided to use the PI assets and practices to develop a comprehensive support model to help students increase their performance capacity.

The course already employed a facilitation model for teaching and a coaching model for evaluation, which aligns with the performance practices of PI. The coaching role required instructors to provide forward-thinking advice to students about improving their strategy in the next advocacy cycle. During the ATP meeting, the instructor decided to expand upon and formalize this promising practice. As a result, the instructor made plans to (a) revise rubrics with a pass or revise-and-submit grading schema, (b) include personalized and personal feedback through screencasting, (c) enhance forward-thinking advice to students to be developmentally appropriate based on their continual improvement in practice, (d) prepare a more approachable, user-friendly, and synthesized presentation of the advocacy tools, and (e) improve internal motivation by adding badging and microcredentials based on the knowledge students gain and their demonstration of the advocacy tools in practice.

Instructor 1 pointed out specific ways she viewed the four assets of the PI framework when she revised the course. For example, including in-depth reflection, meaningful collaboration among students and classmates, re-building ideas from the key readings as an instructor-authored ‘briefing,’ were coded as addressing the Intellectual asset. Having students publish a blog post with a call to action embedded in it and pushing their weekly blog posts to targeted individuals who they had identified as being like-minded were coded as addressing the Moral Asset. Requiring students to take responsibility for researching the contextual circumstances from all angles, staying abreast of current events, and verifying the credibility and comprehensiveness of news sources was coded as addressing the Civic Asset. Asking students to increase their fluency and use of the advocacy tools, reflect on and apply their instructor’s feedback, and seek to ‘start a movement’ was coded as addressing the Performance Asset.

Instructor 2

Students in TEL 410 learn about styles of leadership, study advocacy techniques, position themselves as advocates, and create a plan with goals that will allow them to help address the identified needs within a selected community. They do this by working with an already-established organization. The goal of the course is twofold: 1) to get students to think about what they are passionate about and 2) to encourage community engagement.

This instructor noted three interrelated areas that would be expanded upon. The first is that students should have multiple ways of interacting with an organization and learning about a cause. This is related to the Intellectual Asset. Films, recorded interviews, and other forms of multimedia will be accepted in the future as a means of allowing students to expand their knowledge base. Furthermore, as part of the information-gathering process and defined as related to the Moral Asset, it was determined that students should also understand the opposing views and organizations to better understand the cause of the organization and the organization itself. Finally, it was determined that students should journal with the intention of reflection and growth. While journaling was initially part of the course, it was less intentional before this research was conducted. Prompts will now be provided to students to help facilitate deeper-level thinking. This is related to the Civic Asset of the PI framework. Finally, when students engage with the organization that they have chosen, the goal is that this pre-work will allow them to be better prepared and have a greater understanding of the cause and the organization. Therefore, this is representative of the Performance Asset since this is the point in the course when students are engaging with the organization and using their newly gained knowledge.

Instructor 3

The instructor selected the first unit in LSE 401 for integration of PI to increase students’ viewpoints on diversity and to broaden their concept of the defining factors of diverse populations. In prior course iterations, students had viewed diversity in a limited manner, mainly focusing only on race, socioeconomic status, or physical ability. The instructor was challenged with engaging students in learning about multiple perspectives and being critical and compassionate even when presented with an unknown viewpoint or aspect of diversity. The ATP meeting helped the instructor determine that the promising area was using personal narratives early in the course to broaden student understanding of diversity in later units.

To expand the promising area, the instructor decided to move beyond having students simply reflect on already-understood concepts of diversity in the initial unit. This would provide students a starting point when they were asked to research and respond to different perspectives surrounding diversity issues. The instructor also made changes to improve the use of first-person narratives by asking students to consider how their concept of diversity was changed through reading, watching, and listening to diverse perspectives. The instructor revised the reflection unit to focus on civic assets by asking students to consider their experiences in the context of different types of diversity, and instances where they had limited experiences with diversity and diverse viewpoints. This adjustment would allow students to consider where their personal limitations impact their perceptions and actions. The instructor indicated that these adjustments would better prepare students to evaluate a public space for different types of diversity and accessibility.

Instructor 3 considered each asset of the PI framework when creating course revisions. Throughout the course, students critically and compassionately reflect on the lived experiences of others through the examination of narratives, artifacts, personal interviews, and location visits. The instructor coded these experiences as the Intellectual asset, specifically using the practice of reflecting critically and compassionately. Students used moral and ethical decision-making, a key practice from the Moral asset, to create proposals to address inequity at locations they visited and analyzed. The Civic asset played a large role in the course, and the instructor coded many experiences as civic. Students participated in the practice of understanding culture and context by engaging with the course texts key ideas surrounding diversity, through personal interviews with individuals that are experiencing challenges related to diversity, and through course discussions. Student experiences that were also coded as Civic included opportunities for students to participate in the practice of engaging multiple and diverse perspectives. This was accomplished through the examination of diverse narratives that were found in course readings, TED talks, interviews, and student-to-student discussions. Finally, students participated in designing creative solutions, a practice from the Performance asset. They first did this hypothetically through a practice evaluation of an organization’s diversity practices, and later created actual proposals and presentations given to organizations providing creative solutions to current diversity issues plaguing the organization.

PI was integrated implicitly

As a result of the professional development work, all three instructors chose to represent PI as an underlying construct to support students in the learning of course content, not to teach the PI assets and practices directly. Further, the ATP data showed that after establishing the promising area and making plans to expand it, instructors still opted to apply the PI framework implicitly.

Instructor 1

Instructor 1 explained that the course did not explicitly represent character, although, prior to the workshop, some aspects of character were evident. During the ATP protocol, this instructor realized the importance of students synthesizing the many change-oriented frameworks and implications of research studies covered by the course materials to improve their advocacy strategy. Although the articles and research studies included in the course did not explicitly address character, as the instructor explained, they represented a principled orientation to gathering followers and leading advocacy projects:

So, first of all, principled innovation is not explicit in this course at all. I never talked about it. I never explained it. I chose um, the primary reading is Stephen Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective People and there are seven units in the course, so each week one of those readings is the central focus. Additionally, I’ve added or complimented that with a practice-based research article. So, students get the opportunity to see that particular habit represented principally in research, and there are a variety of contexts. Those articles come from medicine, social work, etc. So, I like the universal nature of how principled innovation shows up in this course.

The ATP conversation helped this instructor realize the challenge students taking this course face when asked to apply a combination of leadership, change, education, and communication tools of advocates, all at once. Referring to the Performance assets and practices of the PI framework helped the instructor empathize with undergraduates about this challenge. The instructor chose to keep all the tools, but to relocate them to one place, organize them in a way that made the most sense for the course, and establish a portal for easy access. The instructor has since realized the importance of the frameworks being contextualized for advocacy and authored a user-friendly article written for undergraduates that is practice-oriented for educators (Foulger, Citation2022).

Instructor 2

Instructor 2 took over a course that had previously been designed and was provided the latitude to make changes that she felt were needed in the course content and delivery. This did not include the explicit inclusion of PI. However, she integrated and utilized the PI card deck given to faculty members during the training. The cards had a set of PI oriented attributes and associated questions for innovators. She used the cards as a scaffold for students (Arizona State University, Citationn.d.). The questions are meant to encourage innovators to be more critical about their reflection as part of the course design process. Instructor 2 discussed how she utilized the cards to ensure that she had critically reflected on the changes she had made.

I did not infuse PI explicitly in my course, but I did so implicitly and I’m going to show you how. One way that I did this was that I use these cards that were given to us. They have questions that we should be considering when we’re designing courses and when we’re doing work and engaging in work as a means of infusing PI into what we do. So, if we look at module one, module one thinks about privilege, community building, and partnership. It discusses what leadership means to the student so it’s trying to get students to think about what it means to them.

Instructor 2 additionally explained:

As you can see [referencing the online course materials], there’s information about the context of the community one works in, coalition building, and if we go to readings, there are readings on privilege, there are readings on cultural humility, and there are readings on cultural competence. The goal was to get students to really think about how others might perceive this decision or action. So, how others perceive the person’s decision or action based on that person’s positionality.

Instructor 2, being a researcher who focuses on critical theory, utilized this method to incorporate criticality into her course. She wanted to ensure that she was modeling reflection, since she was asking her students to reflect.

Instructor 3

The instructor shared that the PI training helped her address some of the assets and practices of PI in LSE 401, albeit implicitly. When the instructor participated in the ATP meeting, she realized that re-designing the use of first-person narratives within the sequence of activities would implicitly support students in gaining skills from PI.

This course does not explicitly teach principled innovation; however, it is implicitly linked for nearly all of the assignments. In this course, the students use many of the practices of principled innovation. They understand the culture and context in which they’re working, and they engage multiple diverse perspectives by understanding who is and isn’t included in various environments. They also identify and acknowledge fundamental values and utilize moral and ethical decision-making.

During the ATP conversation, the instructor decided to include more opportunities for students to engage with first-person narratives to improve their ability to reflect on the experiences of others. To expand the promising area, the instructor wanted to have the students conduct fieldwork from others’ perspectives, create advocacy proposals, and share their proposals with influential individuals in the field.

PI was integrated in ways that supported the learning objectives

When challenged to add PI to their course and then identify and expand upon a promising area, all instructors maintained the original instructional goals and learner outcomes. Overall, the instructors felt that the ways in which they expanded the promising area would afford students the opportunity to learn the course content while developing their character.

Instructor 1

Instructor 1 discussed the goal of supporting students to be successful in ‘starting a movement.’ After the ATP conversation about expanding the promising area, the instructor added badging to the course to help students have a stronger commitment to strengthening the individual skills of advocates as promoted by the course (i.e., students can earn seven badges).

The overall goal in the course for students is to create a movement, and there is a badging structure to the course where, um, students who demonstrate that they have followers can level up through four levels.

Microcredentials were added to publicly recognize students who establish followers and who engage their followers in calls to action that they promote (i.e., students can earn four microcredentials).

Beyond the goal and measurable outcome of engagement related to their ‘movement,’ this instructor also highlighted that she feels PI as an underlying construct of the course has helped improve the extent to which students have a clearer understanding of themselves at the end of the course.

The space that I think this helps students the most is that it sends them away from me at the end of the semester changed … They have seen their, um, their passions, the things they care about the most in the world from many, many, many different angles, and they have seen how other people do or do not care about them.

Instructor 2

Throughout the research process, Instructor 2 noted the importance of students being intellectually prepared to engage with professionals in an organization. After the ATP conversation about what intellectual ‘preparedness’ means, the instructor decided to require students to investigate ideas that are oppositional to their cause. This would allow students to be more well-rounded and consider diverse perspectives. To further support students considering diverse perspectives, the instructor decided to expand the optional readings and multimedia resources. While the course has required journaling, the instructor has planned journal prompts as a means of reflecting more deeply about their values, perspectives, and motives as well as the values, perspectives, and motives of those who work in the organizations students partner with.

Instructor 2 highlighted that the PI training and adding PI to the course helped her realize the necessity of scaffolding students to go into the professional world with a strong sense of knowledge about the field they will be working in and to speak to others outside of the university in a professional manner. As students must go to an organization, introduce themselves, and discuss the organization with stakeholders, the intent is that they will learn to utilize the background information they have collected and facilitate change-oriented discussions with stakeholders. The instructor made these changes to support students in building professional skills that would help them be effective advocates who are engaged with the community.

Instructor 3

Finally, Instructor 3 expanded on the use of personal narratives because of an in-depth review of the promising area identified during the ATP discussion. A major goal of the course is for students to advocate effectively for educational solutions that address social concerns. The majority of the students who take this course have significant interest in special education, but they are expected to look at inclusion from various perspectives. In one assignment, narratives were used to help students relate to current conditions from different perspectives:

In order to do this, they go on a universal design field trip where they actually visit a community space and evaluate it for universal design properties. This may be a museum or restaurant, anywhere that they can go and explore an area and see who the setup is for and who this is excluding. Using that information from that they will complete number three, redesign a current community space to better meet the needs of diverse participants using the elements of universal design. So, for this, they actually propose a change to the community space by writing to and including visuals of the space that they evaluated and suggesting different designs.

The assignment includes advocacy and community involvement, as well as the exploration of others’ experiences. The instructor shared how she wanted to change the course to encourage students’ critical reflection about familiar spaces:

I feel like throughout the course there, they have to confront spaces they may have been 100 times but haven’t really thought about the space and in a moral and ethical way of like, ‘is this a positive and productive space for everyone?’

During the ATP conversation, the instructor decided to improve how students used first-person narratives and to take advantage of the deep exploration of diverse viewpoints and experiences found in narrative writing. The instructor also wanted to leverage the power of the narratives to help students learn to explore the world around them, especially in their future career fields. The instructor explained her ideas about these changes to the sequence of activities:

We want to broaden students’ minds to understand the different concepts of diversity in the workplace. Additionally, they explore the specific areas of need in different workplaces. For example, if they are exploring the medical industry, they may look at a current events surrounding the treatment and inclusion of people in the LGBTQ+ community. They create new solutions for current and historical diversity and inclusion issues.

This instructor incorporated PI into her curriculum in such a manner that students were able to utilize personal narratives to a greater extent. This allows for students to reflect on diversity and inclusion but also through their own paradigm and experiences.

Discussion

This discussion consists of two parts. First, we discuss connections to other studies about the integration of a character framework as related to the implicit and explicit representation of character. Second, we propose a framework that might support the systematic representation of character in courses.

Existing courses can be improved by integrating a character framework

In our study, we successfully incorporated character education in our courses in an implicit manner, using a pre-existing framework. Other studies have evaluated the effectiveness of integrating character development into the pre-existing curriculum with mixed outcomes.

As an example of integrating a pre-determined character framework explicitly, the International Baccalaureate (IB) program has ten attributes of character that are explicitly and implicitly taught to K-12 students in addition to the general curriculum (Bryant et al., Citation2016; Keser et al., Citation2022). The attributes of the IB program encourage and train learners to continuously develop their abilities to be inquirers, knowledgeable students, thinkers, communicators, principled, open-minded, caring, risk-takers, balanced, and reflective (Bryant et al., Citation2016; Keser et al., Citation2022). There are clear definitions, curriculum, and age-appropriate activities provided for each year students are in the IB program to teach these attributes. Students, teachers, administrators, and families find added educational value when the 10 attributes of the IB program are used at schools (Bryant et al., Citation2016; Keser et al., Citation2022). Research has demonstrated that explicitly teaching the 10 attributes to IB students improved their academic scores, preparation to act as a global citizen, cultural awareness, and self-efficacy (Bryant et al., Citation2016; Keser et al., Citation2022).

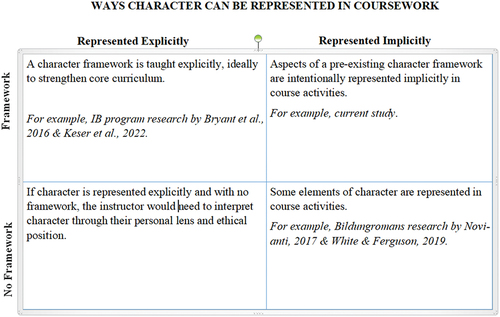

Studies in higher education showed that when instructors did not rely on a framework and students were expected to apply their new understandings of character from course materials, they had limited success (Novianti, Citation2017; White & Ferguson, Citation2019). In these studies, character education was implicitly taught through literature courses using Bildungsromans, which are stories about character and spiritual development that occur during the characters’ formative years, or through critical stages of their development (Novianti, Citation2017; White & Ferguson, Citation2019). This model allowed students to better identify and discuss character attributes; however, implicitly representing character did not necessarily develop the learners’ character (Novianti, Citation2017). For instance, a student may recognize that Character A is persistent, and that persistence is a desirable character attribute, but it does not necessarily translate into the student developing persistence themselves (Novianti, Citation2017; White & Ferguson, Citation2019). This research demonstrated that addressing character implicitly and without a character development framework helped students to be more aware of character but showed limited impact on the development of their own character.

The approach faculty took to infuse PI into their courses was a combination of the two examples provided above. Regarding the use of a framework, like the IB program, there are specific assets and practices in the PI framework to define character and what attributes a person should have to demonstrate the desired character outcomes. Regarding implementing character implicitly, like the use of Bildungsroman to allow for implicit teaching of character traits, the researchers used readings, projects, and experiences to allow students to construct their own understanding of character and internalize their viewpoint of what PI means to them. When these parts of the courses were re-designed by integrating the PI framework, they did not include all assets and practices. In this way, the course curriculum stayed intact and remained the focus of the learning, and the aspects of character development were represented during the learning process but did not overshadow the main thrust of the course.

A proposed character representation framework

Reviewing our study from the perspectives of implicit and explicit representations of character, with or without a framework, we wonder what would happen if character development was represented without a framework and how instructor bias about how to define character may play into course design. More research is needed in this area. See .

As important as it was that instructors found ways to integrate PI into courses, it was more important that the inclusion of PI supported the learning objectives in all three courses. As instructors noted, the PI framework helped them find ways to simultaneously support students to strengthen professional skills while they were performing education-oriented functions such as advocating, leading, or teaching. In these courses, professional skills such as communication, perspective-taking, collaboration, and establishing a platform or followership were strengthened by the PI assets and practices. Notably, integrating PI in all three courses improved students considering how individuals, each with diverse talents and needs, can be included in change-oriented processes and target goals or outcomes.

All three courses had some component of community embeddedness, which could have made this finding unique to these courses. We have little information regarding how the framework might be integrated into other subject areas in education such as in mathematics or a scientific field. Generalizing the results to courses of education that address other subjects such as mathematics methods or a scientific field should be done cautiously. Additionally, our research context was unique in that all three courses in this study asked students to engage in real-world activities that were field-based or field-oriented. Although fieldwork is an essential component to most majors, this factor could have been an essential ingredient to instructors’ work in applying PI in meaningful ways. When considering integrating a character framework like PI into coursework in majors outside of education, instructors should be cautious that the framework advantages the development of a student’s professional character. Innovation and research in this area are needed.

Community immersion projects and service-learning activities often require students to interact with marginalized populations. A study of counseling coursework (Couture, Citation2021) suggested that students with an ethics-taking perspective showed enhanced multicultural awareness—a better understanding of diversity and similarities, improved empathy, and increased motivation to establish relationships. Others have remarked that character development is a relational and context-specific attribute and that one’s character is developed by those in the organization and, reciprocally, that the organization and those in it are impacted by an individual’s strengthened moral, performance, intellectual, and civic character (Shields, Citation2011). In fields where strong character is essential to successful interactions and leadership callings, scholars have called for opportunities to apply these practices in situations where mentoring, instruction, and developmentally appropriate leadership opportunities could benefit the learner (Murray et al., Citation2019).

Conclusion

The instructors who were involved in this study learned about and then integrated a character development framework, Principled Innovation, into courses that were oriented toward change. Our study demonstrated that the instructors integrated the very specific and practically oriented PI framework implicitly in their courses. While the ways in which the instructors integrated the PI framework did not change the goals of the course, the adjustments instructors made to their courses when they integrated the PI framework supported students in explicitly defining their own passions, recognizing their values, and honoring differences and similarities among individuals and organizations in their communities. Instructors also noted that in their effort to integrate PI implicitly, they ended up also improving the course design and pedagogy.

There are limitations to this study. It consisted of three participants and while that can provide robust data for analysis, it also leaves space for concern about whether the findings are replicable and if they would have been the same if there had been more participants. Furthermore, it is unclear whether those in different academic fields might have the same results as the authors/instructors in this study. For example, those in STEM fields might have a more difficult time focusing on character because of the nature of the work they do. Researchers, such as Martin et al. (Citation2021), point this out in their work on engineering departments in IHE and the growing concern regarding a lack of character education. More research is needed regarding how this framework might work in such a setting. Instructors who teach topics outside of the domain of education might call on this study to help them think about how their subject matter could benefit from integrating character frameworks like PI into their teaching.

Future scholarship is needed to support instructors in determining the impact of integrating the PI frameworks on students’ performance and on their future demonstrations of character. Additionally, attempts to use coursework to address the development of character by integrating PI across an entire program need to be researched to understand how learning experiences can be reshaped to ensure students meet developmental milestones in the shaping of their character.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shyla González-Doğan

Shyla González-Doğan is an assistant professor in the Division of Educational Leadership and Innovation at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University. Much of her research focuses on the experiences of immigrants, refugees, or those of the first generation. She also has a strong interest in identity formation, practices of inclusion and exclusion, and Islamic education.

Teresa S. Foulger

Teresa S. Foulger is an associate professor of educational technology in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University. She has expertise in leading educational transformation and seeks to advance the use of technology for learning. Her research interests include technology integration and technology infusion in teacher preparation, professional development, and organizational change.

Ashleigh M. King

Ashleigh M. King is the Arizona State University site coordinator for students seeking their master’s degree in elementary education and teacher certification through a 15-month accelerated program. She developed an innovative program, the Technology Infusion Experience, to bring training and technology to teacher candidates and mentor teachers. Ms. King has her master’s degree in educational administration, a reading instruction endorsement, structured English immersion endorsement, cross categorical K-12 special education certification, and undergraduate degrees in English composition with an emphasis in comparative religion.

References

- Althof, W., & Berkowitz, M. W. (2006). Moral education and character education: Their relationship and roles in citizenship education. Journal of Moral Education, 35(4), 495–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240601012204

- Arizona State University. (n.d). Principled innovation card deck. https://url.us.m.mimecastprotect.com/s/dZfZC82o95fwxpB2zsnZzasdomain=pi.education.asu.edu/

- Bara, F. E. (2015). Wilhelm Von Humboldt, Cardinal John Henry Newman, and José Ortega y Gasset. Some thoughts on character education for today’s university. Journal of Character Education, 11(1), 1–20. https://link-gale-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/apps/doc/A437132810/AONE?u=googlescholar&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=24fea635

- Brooks, E., & Villacís, J. L. (2023). To educate citizens and citizen-leaders for our society: Renewing character education in universities. Spanish Journal of Pedagogy, 81(284), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.22550/REP81-1-2023-03

- Bryant, D. A., Walker, A., & Lee, M. (2016). A review of the linkage between student participation in the international baccalaureate continuum and student learning attributes. Journal of Research in International Education, 15(2), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240916658743

- Cech, E. A. (2014). Culture of disengagement in engineering education? Science, Technology, & Human Values, 39(1), 42–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243913504305

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

- Couture, V. (2021). Enhancing multicultural awareness: Understanding the effect of community immersion assignments in an online counseling skills course. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(5), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v10n5p201

- Creswell, J. (2015). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

- Denzin, N. K. (2012). Triangulation 2.0. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(2), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689812437186

- Esterberg, K. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research. McGraw Hill.

- Fitzmaurice, M. (2008). Voices from within: Teaching in higher education as a moral practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(3), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802045386

- Foulger, T. S. (2022). Tools for starting a movement: A briefing for advocates. In Pathways to Research in Sustainability SUS008 (pp. 1–23). Salem Press & EBSCO Information Services. https://www.pathways2research.com/search/eds/details/tools-for-starting-a-movement-a-briefing-for-advocate?query=Tools%20for%20starting%20a%20movement%3A%20A%20briefing%20for%20advocates&db=pts&an=158273337

- Foulger, T. S., González-Doğan, S., & King, A. (2021, November). Infusing the Principled Innovation Framework into undergraduate coursework [Symposia session]. In From Values Education to Principled Innovation. Mohamed I University.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2003). The value of positive emotions: The emerging science of positive psychology is coming to understand why it’s good to feel good. American Scientist, 91(4), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1511/2003.26.330

- Fusch, P., Fusch, G. E., & Ness, L. R. (2018). Denzin’s paradigm shift: Revisiting triangulation in qualitative research. Journal of Social Change, 10(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.5590/JOSC.2018.10.1.02

- Hackett, R. D., & Wang, G. (2012). Virtues and leadership: An integrating conceptual framework founded in Aristotelian and Confucian perspectives on virtues. Management Decision, 50(5), 868–899. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211227564

- Jubilee Center for Character and Values. (n.d.). Jubilee center for character and values. https://www.jubileecentre.ac.uk/

- Keser, Ö., Altan, S., & Lane, J. (2022). Learner profile attributes in IB teaching: Insights from a continuum school in Turkey. Journal of Research in International Education, 21(3), 256–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/14752409221139051

- Kohlberg, L. (1975). The cognitive-developmental approach to moral education. Phi Delta Kappan, 56, 670–677. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20298084

- Komives, S. R., Dugan, J. P., Owen, J. E., Slack, C., & Wagner, W. (2011). The handbook for student leadership development (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Lamb, M., Brant, J., & Brooks, E. (2021). How is virtue cultivated? Seven strategies for postgraduate character development. Journal of Character Education, 17(1), 81–108.

- Leydens, J. A., & Lucena, J. C. (2018). Engineering justice: Transforming engineering education and practice. Wiley-IEEE Press.

- Maritain, J. (1943). Education at a crossroads. Yale University Press.

- Martin, D. A., Conlon, E., & Bowe, B. (2021). A multi-level review of engineering ethics education: Towards a socio-technical orientation of engineering education for ethics. Science and Engineering Ethics, 27(60). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00333-6

- McGrath, R. E. (2022). Some key issues in the evaluation of character education. Journal of Education, 202(2), 498–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220574211025066

- Mik-Meyer, N. (2020). Multimethod qualitative research. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 357–374). Sage Publications.

- Mohr, B. J., & Watkins, J. M. (2002). The essentials of appreciative inquiry: A roadmap for creating positive futures. Pegasus.

- Murray, E., Berkowitz, M., & Lerner, R. (2019). Leading with and for character: The implications of character education practices for military leadership. The Journal of Character & Leadership Development, 6(1), 33–39. https://jcldusafa.org/index.php/jcld/article/view/139

- Nafi, N. B., & Kamaluddin, A. (2019). Good governance and integrity: Academic institution perspective. International Journal of Higher Education, 8(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v8n3p1

- Nagashima, J., & Gibbs, N. P. (2022). Sensegathering and iteration: The evolution of a character education framework in higher education. Journal of Moral Education, 51(4), 518–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2021.1909547

- Novianti, N. (2017). Teaching character education to college students using bildungsromans. International Journal of Instruction, 10(4), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2017.10415a

- Paulsen, T., Clark, T., & Anderson, R. (2016). Using the tuning protocol to generate peer feedback during student teaching lesson plan development. Journal of Agricultural Education, 57(3), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2016.03018

- Riley, D. (2008). Engineering and social justice. Springer.

- Saldana, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Savage, J. (2000). One voice, different tunes: Issues raised by dual analysis of a segment of qualitative data. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(6), 1493–1500. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01432.x

- Schiff, D. S., Logevall, E., Borenstein, J., Newstetter, W., Potts, C., & Zegura, E. (2020). Linking personal and professional social responsibility development to microethics and macroethics: Observations from early undergraduate education. Journal of Engineering Education, 110(1), 70–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20371

- Schon, D. A. (1984). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books, Inc.

- Shields, D. L. (2011). Character as the aim of education. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(8), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171109200810

- Shields, D. L., & Bredemeier, B. L. (2011). Coaching for civic character. Journal of Research in Character Education, 9(1), 25–33. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-24859-002

- Stavros, J. M., Godwin, L. N., & Cooperrider, D. L. (2015). Appreciative inquiry: Organizational development and the strengths revolution. In W. J. Rothwell, J. Stavros, & R. L. Sullivan (Eds.), Practicing organization development: Leading transformation and change (4th ed., pp. 96–116). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119176626.ch6

- Stavros, J. M., Torres, C., & Cooperrider, D. L. (2018). Conversations worth having: Using appreciative inquiry to fuel productive and meaningful engagement. Berrett-Koehler.

- Thompson, N., & Pascal, J. (2012). Developing critically reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 13(2), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2012.657795

- Walker, L. J. (1982). The sequentiality of Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. Child Development, 53(5), 1330–1336. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129023

- White, K., & Ferguson, F. (2019). The silence, exile, and cunning of “I”: An analysis of bildungsroman as the place model in the work of Charlotte Brontë and James Joyce. Education Sciences, 9(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040248

- Williams, M., & Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review, 15(1), 45–72. https://imrjournal.org/uploads/1/4/2/8/14286482/imr-v15n1art4.pdf