ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on the experiences of out-of-school girls in Zimbabwe. It draws on a research strand of SAGE (Supporting Adolescent Girls’ Education), a UKAid programme funded through the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) initiative. Using a digital storytelling approach the research highlights critical events that have changed girls’ lives and impacted on how they see their futures. The paper explores insights made possible by this alternative methodology. Crucially, it challenges the often-static representation of ‘marginalised’ and ‘out-of-school’ girls in Sub-Saharan Africa by illustrating the unpredictability of individual circumstances and girls’ perceptions of these, within broader contexts of persistent vulnerability factors. Drawing on the capability approach the paper also offers new insights into the perceived value and purpose of school for out-of-school girls. The findings have implications for conceptualising more creative, contextually appropriate policies and practices for young people who miss out on formal school.

Introduction

In the beginning, my life blossomed like a flower … but if nothing changes, it will be like the grass, ignored and stepped on, a painful life. (Buhle)

This paper focuses on the experiences of adolescent girlsFootnote1 in rural Zimbabwe who are out of school. The longitudinal study from which this paper draws is interested in their aspirations, what has shaped these, and what influences the likelihood of them being realised. It aims to understand girls’ perspectives on learning contexts, pedagogy and curricula that could support these aspirations, and map these perspectives as they participate in a two-year community-based accelerated learning programme.

Here we focus on some findings from phase one of the study, which was carried out with girls who were eligible for, but had not yet been invited to join, the programme. This was deliberate: much work on young people’s aspirations in similar contexts draws on the perspectives of those already engaged with alternative education, where aspirations are potentially shaped by normative values embedded in the programme. As educators who work within capability frameworks we believe that education is a key component of the freedom necessary to live a life of value (Mkwananzi, Citation2019; Sen, Citation1999; Walker & Unterhalter, Citation2007), but as socioculturalists we acknowledge that education can impose perspectives on what is considered to be a valuable life (Appadurai, Citation2004; Buckler, Citation2019). The potential for this is even greater in the international education context we work in: a field powered by donor-funded programmes aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals and other international conventions. These conventions incorporate standardised evaluation tools which shape how education programmes and systems are assessed – and therefore shape what is valued within them. One of our overarching questions in the wider study is how local ideas in relation to learning and imagined futures can be recognised and respected alongside ‘global’ values.

We draw on data generated with girls aged 15–19 during a residential storytelling research workshop. Each girl created a digital story about a critical moment in her life that affected her aspirations: something that made her reflect on whether what she wanted to do or be in the future would, or would not be, possible. We focus on the stories, but also outputs from multi-modal activities built into the story development process and reflections on the stories (from the girls, the research team and audiences who attended story-screening events after the workshop).

This is not the first paper we intended to write from this study. Our plan was to focus on the relationship between critical events and aspirations. However, the data and the process by which it was generated and analysed led to two reflections on the experiences of out-of-school girls that we feel have been previously absent from the academic and policy literature and are necessary to contextualise further findings from the study. Therefore, first, by writing about these stories we aim to disrupt prevailing narratives about ‘marginalised’ and ‘out-of-school’ girls, which tend to frame them within a static state of disadvantage – a state which can be ‘treated’, usually through enhanced access to formal schooling. Second, we explore the perceived purpose and value of school to the girls. While there is a rich and growing body of work on girls’ education and capabilities (see Cameron, Citation2012; Cin & Walker, Citation2016; Raynor, Citation2007; Seeberg, Citation2014; Unterhalter, Citation2012; Vaughan, Citation2007), studies tend to be conceptual, focus on an application of Nussbaum’s central list of capabilities, focus on girls who are currently attending school, or focus on longer-term outcomes of schooling, i.e. how school can enable them to do and be things that they value in the future. Given what our data shows us about the unpredictable nature of the girls’ lives, our analysis in this paper is narrowed to more immediate capabilities articulated by the girls and embedded in their perceptions of the process and experience of schooling, i.e. how school can enable girls to do and be things that they value ‘now’. This is a crucial additional perspective because it can inform programmes designed to make formal schooling more accessible and appealing to girls who are not currently attending, but, more importantly, it can inform multi-sectoral programmes designed to support girls who do not and who likely will not go to school.

Context and conceptual framework

While there has been a welcome shift over the past two decades from focusing on access to schools to also considering what happens in schools, the key public message remains that school attendance guarantees young people a better future (Camfed, Citation2020; Human Rights Watch, Citation2017). This notion is held by many young people themselves (Charaf, Citation2019; Posti-Ahokas, Citation2014). This message runs in parallel with a growing body of research that suggests many young people in schools do not achieve ‘minimum proficiency’ (World Bank, Citation2018, p. 8) and that the potential of formal schooling to transform lives ‘may be more imagined than real’, particularly for girls (Porter, Hampshire, Mashiri, Dube, & Maponya, Citation2010, p. 1094; Ansell, Citation2004; Kruss & Wildschut, Citation2016).

Despite this, reforms for girls’ education repeatedly prioritise 12 years of formal schooling (Commonwealth, Citation2018; Gordon, Marston, Rose, & Zubairi, Citation2019; UK Government, Citation2021, Citation2019). This mainstream consensus, which draws on rights-based frameworks, but is predominantly rooted in human capital perspectives, risks positioning girls as ‘foot-soldiers’ of broader economic aims (Chant & Sweetman, Citation2012, p. 534) and can marginalise exploration of alternative frameworks for re-thinking ‘the frontier between schooling, education and well-being’ (Cameron, Citation2012, p. 300). But there is a scarcity of data about alternative education provision, insufficient funds directed towards it, low implementation capacity, lack of commitment to programme sustainability, and limited coordination at national and international levels (Inoue, Di Gropello, Taylor, & Gresham, Citation2015, p. 1). It is easy to see why formal schooling persists as the normative agenda.

In most countries girls are more likely to be out of school than boys (GEC, , Citation2018a). This is the case in Zimbabwe, where this study is based. Reasons vary between contexts and are recognised to be a complex combination of economic and sociocultural issues. These include school location, absent parents, religious beliefs, inadequate resources, irrelevant curriculum, hunger, poverty, early marriage and teenage pregnancy (Chinyoka, Citation2014; Dakwa, Chiome, & Chabaya, Citation2014; Mandina, Citation2013; Mawere, Citation2012; Moyo, Ncube, & Khuphe, Citation2016; Mukwambo, Citation2019; Ngwenya, Citation2016), with financial constraints repeatedly reported as the most significant. These findings align with large-scale GEC data (, Citation2018b).

A range of models represent this complexity: CREATE’s (Citation2011) extensively referenced ‘zones of exclusion’ facilitated easier identification of those at risk of dropping out; UNICEF’s (Citation2018) Five Dimensions of Exclusion model was designed to ‘capture subtleties of the exclusion problem and the need for different strategies to address different categories of out-of-school children’ (p. 6); and the GEC’s Education Marginalisation Framework (, Citation2018a) demonstrates the interrelation of education access, intersectional characteristics and system level factors. Proposals to address the challenge of out-of-school girls in Zimbabwe can be positioned within these models: a recent policy makes it illegal to exclude pregnant girls (Fambasayi, Citation2020); Moyo et al. (Citation2016, p. 855) promote subsidies for examination fees and the removal of informal costs; Mawere (Citation2012) recommends civil education for communities on the importance of school; Mandina (Citation2013) suggests that schools expand curricula and invest in teaching materials and infrastructure.

While a preventative approach to drop-out focused on external factors (policies, curricula, resources, community support) is clearly important, there are two gaps in the national literature and international framing. The first is girls’ own perspectives around leaving school. There is an implication that girls automatically buy in to the normative value of schooling and that drop-out is imposed upon them by larger, powerful forces (whether family pressures, social norms, systemic poverty or national policies). While we recognise that this may be the case for many, there is little space given to girls’ ideas on what schooling means (or may not mean) to them based on their diverse experiences, or to their agency around the decision to attend school or not.

The second omission is around the presentation of drop-out as an ‘end point’. These external factors are presented as terminal; staying in school is framed as ‘survival’ (Sabates, Akyeampong, Westbrook, & Hunt, Citation2010; UNESCO, Citation2020). Children who have been out of school for a considerable number of years, who would be unable to return to an age-appropriate grade, and those whose responsibilities and financial resources cannot (and likely will not) accommodate full-time education are ‘policy orphans’ (Inoue et al., Citation2015, p. 1), whose needs slip between the responsibilities of different government departments. This has led to a missing narrative around the ‘what next’ for the girls who have dropped out of school, including the consideration that some may not want to go back. A GEC report (GEC, Citation2019), for example, highlights different forms of alternative education provision and emerging evidence around its appeal to girls and their families. For some, alternative education is more appealing than formal schooling.

This study is interested in what girls who are currently out of school want to do with their lives, and how they think education might support this (or not). As mentioned, what is distinct about the findings from this first phase is that they were generated in advance of the participating girls having any engagement with the education programme. Most research on the aspirations of out-of-school children is undertaken within such a programme (DeJaeghere, Citation2016; Dutt, Citation2010; Matsumoto, Citation2018). We recognise logistical and methodological reasons for this, but relying on these narratives as representative of all out-of-school girls resonates with Khoja-Moolji (Citation2016), who highlights the tendency for girls’ voices to be used to ‘re-amplify the already established consensus around possibilities and limitations for girls in the global south and often serve to reinforce the solutions and programmes that are already in place’ (p. 746, also Van Diesen, Citation1998).

Enarson (Citation2000) points to the tendency for development programmes to separate distinct aspects of people’s lives along thematic lines that speak to the underlying logic of proposed solutions. The popular lists of reasons why girls do not attend school can be read in this way, and it is notable that recent lists (Theirworld, Citation2017; Wodon, Citation2018) are almost identical to those published two decades ago (Tijerina, Citation1998), ‘freezing’ understood experiences of these girls in time and space. We know much less about the day-to-day experiences of girls, critical events that can trigger – or partially resolve – more persistent challenges, or the influence girls have over these experiences and events. The interrelation between these and how they individually and collectively impact on out-of-school girls’ imaginations about what their futures might look like, as well as girls’ agency in relation to these experiences and the resolution of them, is often missing from accounts of their lives (see also Zipin, Sellar, Brennan, & Gale, Citation2015). As a result, we often only ‘see’ these girls in the context of what outside agencies can do for them within the parameters of conveniently isolated and deceptively discrete challenges.

With this in mind, a conceptual framework was developed which combines sociocultural ideas (e.g. Wenger, Citation1998) and the capability approachFootnote2 (Sen, Citation1999). This was designed to enable a lens on what girls value, how they are able to navigate the pursuit of these values, and how their situations change – for the better as well as for the worse – in rural contexts often portrayed to be static (Buckler, Citation2015). Our understanding of the girls’ aspirations and the meanings they attach to schooling is supported by how the capability approach helps researchers and participants to articulate what is valued and the real opportunities and the freedom (capability) to pursue what is valued in their unique contexts. A key strength of the capability approach is its potential to account for opportunities and constraints (conversion factors) within social and institutional structures that can convert resources into genuine freedoms (or not) (Robeyns, Citation2005; Robeyns, Citation2017). Working backwards, too, identifying girls’ perspectives on school-related capabilities (i.e. the freedoms – from their experiences – that school can facilitate) helps us understand what shapes their aspirations and the decisions they make related to schooling.

The capability approach recognises that the freedom to choose from available opportunities to lead valued lives encourages individuals to act as agents to bring about the achievements they desire (Griffin, Citation2008; Liao, Citation2010). However, it also recognises that individuals may have very different levels of capability even if the contexts in which they are living look very similar (Sen, Citation1992). In line with the GEC’s Gender Equality and Social Inclusion standards (GEC, , Citation2018c), we wanted to draw attention to and evidence interpersonal comparisons between out-of-school girls’ experiences, opportunities, aspiration and agency rather than treating them as a homogenous group. According to Robeyns (Citation2016), considering the complex interaction of societal influence is important, as individual capabilities are influenced by their social ecology (Sen, Citation2009; Stern & Seifert, Citation2013), which is non-static. This notion of interaction links the capability approach and our sociocultural framing which conceptualises individuals in a process of ‘becoming’ through their learning experiences (Wenger, Citation1998, p. 215) and where the potential for transformation of what is valued and what is possible in spaces of learning is in dynamic tension between the individual and the community. The capability approach, informed by a sociocultural understanding of learning and development, facilitated the positioning of the girls not as static and passive, but within ‘a dynamic frame in which they are constantly involved in the process of becoming themselves and realising themselves’ (Giovanola Citation2005, p. 251).

The study

The research is a collaboration between The Open University (UK) and Plan International (UK and Zimbabwe) as part of a FCDO UKAid-funded programme under their Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) initiative. The data for this paper were generated during a residential storytelling workshop in Harare, Zimbabwe in April 2019. Eleven girls (aged 15–19) from across Zimbabwe participated in the workshop. The girls were invited having been selected by community leaders for participation in a forthcoming programme called SAGE (Supporting Adolescent Girls’ Education)Footnote3 – although they were not made aware of this until after the workshop. Consent to participate in the workshop was sought from the girls and their parents/caregivers. Local chaperones accompanied and had pastoral responsibility for the girls. The workshop was designed to be inclusive of disabilities, welcoming to breastfeeding mothersFootnote4 and entirely text-free to ensure girls with all literacy levels could participate. The main languages in the workshop were Shona and Ndebele. Pseudonyms are used for girls in this paper.

The Principal Investigator and one of the Co-Investigators are UK-based academics with several years’ experience working in education in Zimbabwe and Sub-Saharan Africa. The other Co-I is a Zimbabwean academic based in South Africa, specialising in researching young people’s aspirations. The team also included two Zimbabwean research assistants (Plan staff members with extensive experience of evaluating girls’ education and welfare programmes). A third Zimbabwean Plan colleague contributed as a support counsellor in case girls needed time out from the workshop.Footnote5

Approach

The research required a methodology that would support the process of building trust and a shared language around ideas of key moments, aspirations, agency and the interplay between these (Hart, Citation2013). Because we knew (from the literature and our own experiences) that the girls might not have had many opportunities to articulate their plans for the future, the approach was developed to slowly and iteratively build a picture of the girls’ ‘aspiration horizons’, to help them to articulate the opportunities and limitations of their environments and imagine other possibilities (Mkwananzi, Citation2013, p. 45). The research is using storytelling as its core methodological approach, specifically a tailored version of an approach developed by Wheeler, Shahrokh, and Derakhshani (Citation2018).Footnote6 As such, we frame this kind of storytelling as both methodology and epistemology: practically it generates data around social issues, but it also frames knowledge as a process or temporary state. Storytelling research does not search for ‘answers’ or ‘truths’ but aims to understand how people (both storytellers and audiences) make sense of the world and help them to think about persistent problems in new ways (ibid). Capturing these shifts in thinking is key to the role storytelling research can play in policy change.

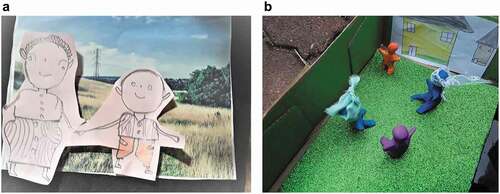

Across five days the girls were supported to develop, illustrate and produce a digital story about a key moment in their lives that had influenced their aspirations. Carefully curated activities helped them to ‘zoom out’ and think about their lives as a whole, before ‘zooming in’ to consider critical moments. Each girl chose one of these moments and subsequent activities helped her to develop a narrative structure and a series of images around it.Footnote7 indicates the kinds of outputs from these activities. On the last day, the girls collated the narrative and images into a digital story on a tablet using the ‘Power Director’ app. The workshop concluded with a celebratory screening of all the stories to the group.

Figure 1. Two examples of the kinds of creative outputs that were designed by the girls in the development and illustration of their story narratives.

The use of narrative and story are simultaneously held up as ‘indigenous’ research approaches (Datta, Citation2018; Iseke, Citation2013) and criticised for their colonial notion of abstracting the individual voice from wider structural realities (Mayo, Citation2004). We are invested in this debate and in other work we critique how storytelling is facilitated across institutions and geopolitical boundaries (Chamberlain, Buckler, & Mkwananzi, Citation2021). Our intention was that the iterative and collaborative research design would help girls to share stories of individual experiences, while also helping them, and us, to see how their stories ‘echo those of others in the sociocultural world’ (Webster & Mertova, Citation2007, p. 2). Drawing on Jackson’s (Citation2013) suggestion that opportunities to shape a moment into a coherent narrative can help people to see how they are – or could be – ‘actors and agents in the fact of experiences that make [them] feel insignificant, unrecognised or powerless’ (p. 17), we intended that the space to share stories about aspirations would support our capabilities framing where freedoms (and unfreedoms) and agency (or not) would be surfaced. This positioning of storytelling also resonates with our conceptual framework, for example Bruner’s ideas about the symbiotic nature between ‘our experience of human affairs’ and ‘the narrative we use in telling about them’ (Citation1996, p. 132), as well as understandings of capabilities and aspirations that show how they are formed in the ‘thick of social life’ (Appadurai, Citation2004, p. 67; Buckler, Citation2015).

Data and analysis

The workshop generated 11 digital stories, 3–6 minutes long, as well as a wide range of creative outputs (collage, drawings, plasticine models), transcribed interviews, conversations and focus groups with the girls about themes emerging from the stories, and fieldnotes from the research team.

The analysis process for stories necessarily differs from other qualitative data, given the distinction between a series of prompted, un-prepared responses across a range of topics (generated through interviews, for example) and an iteratively constructed account of an event chosen by the participant. We do not suggest that the stories provide a comprehensive account of the aspirations or experiences of out-of-school girls in Zimbabwe, but rather an insight into how girls see themselves in relation to particular events and/or how they want to be seen by others in relation to these events. As in Buckler, Stutchbury, Wilson, Cullen, and Kaije (Citation2021), our analysis is inspired by Walter Benjamin (Citation1968) in that a story differs from ‘information’ which must be ‘understandable in itself’ and is ‘shot through with explanation’ to facilitate this. Stories contain ‘openly or covertly, something useful’ but people may have different perspectives on the nature of this ‘use’. The stories were not an ‘end point’, but prompts for capturing different interpretations of how the ideas within them spoke to notions of aspirations and capability.

The analysis, therefore, involved three parallel activities. In the first the research team aimed to identify their interpretation of the key message of each story. This was not the critical moment or the specific aspirations, but rather the capabilities (freedoms) the story spoke to and what each girl was communicating about these freedoms through the story. We individually identified capabilities across the stories, before sharing and debating these. Second, we systematically revisited the other data to understand these capabilities in the context of the wider experiences of the girls’ lives, and how these experiences were communicated through the stories’ development. Finally, we collected responses to and insights around the stories from the girlsFootnote8 and a range of colleagues and stakeholders who were shown the stories at screening events in the UK and Zimbabwe,Footnote9,Footnote10 and we used these responses to reflect on and add to our initial analysis.

These activities align with our sociocultural framing and reflect the commitment to iterative dialogue and reflection that underpins the process of story-generation, but also stories’ reception, interpretation and use. They support the ongoing construction of more inclusive and fluid narratives around development challenges (Wheeler & Bivens, Citation2021) and the potential for a story’s message to be received and responded to in different ways by different people over time.

Findings

We anticipated a narrow range of aspirations and a diverse range of critical events. Instead, the girls articulated a wide range of aspirations, but the critical event in all 11 stories was either about, or related to, a time they had to stop going to school: school was centrally significant across the broader story of their lives, even though (or perhaps because) they were not currently attending. We write ‘a time’ they had to stop going to school, not ‘the time’, because for several of the girls this was not a one-off event. Also, for some girls, the connection between the critical event and drop-out was abrupt, but, for others, the critical event was the catalyst for a prolonged and unpredictable period where the decision to attend school or not was part of a wider range of choices focused around the pursuit of the girls’ and their families’ well-being. Some of the girls had much more input into these decisions than is suggested by the top-down factors for drop-out discussed earlier.

The following excerpts from the stories illustrate two key ideas that have emerged from this first stage of the research. The first challenges the predominantly static portrayal of out-of-school girls’ lives. The second considers the centrality of schooling in their narratives and explores values associated with this.

‘Marginalisation’ is not a static state

The stories reveal multifaceted lives where the complexity of marginalisation written about elsewhere is evident. More than this, however, the stories detail lives lived either side of the marginalisation boundary. Some girls had crossed this boundary multiple times. Busi attended a local school, but then dropped out. Her sister got a scholarship to an exclusive boarding school and Busi was able to enrol with some left-over funding. But the funding ran out and she returned home. For a while she attended a local school, but then her mother lost her job, so Busi had to drop out again to earn money to support the family. Other stories convey a similar pattern:

I was born a premature child. When I was still in hospital with my mother, my brother died. This caused the separation of my father and mother. They would blame each other for my brother’s death. So I was born under a shadow, and my life as a young girl was full of darkness [… .] The darkness lifted after my mother took us to go and live with our grandfather who loved me so much and bought me everything I needed. We went to school, ate good food, had shoes and nice clothes. We lived in a big house [… .] But when I completed Grade Seven [I had to drop out]. I went to live with my mother [… .] Life was good [but] in Form Two my mother did not get money to pay for my school fees. That is when I thought of getting married. I got married and had a child. […] I had thought that my husband would take me back to school. This did not happen. I also thought that since he was working, he would make my life better. This did not happen. (Linda)

The stories challenge prevailing ways in which girls’ lives are framed and reported. First the girls’ experiences of attending school intermittently in different locations adds a new dimension to the literature on drop-out as well as models of it which position it as an ‘end point’. The experiences of moving in and out of school, and affluence, also challenge established conceptualisations of marginalisation, and UNESCO’s regularly drawn-upon 2010 definition with its emphasis on a ‘persistent’ state (Citation2010, p. 135). These conceptualisations facilitate an analysis of exclusion or marginalisation at a moment in time but do not capture how girls move into and out of a state which would be considered to be marginalised. The World Bank’s model for addressing drop-out has the three strategies of retain, remediate and integrate into the labour market (Inoue et al., Citation2015), but includes no recognition of or strategy for young people who move in and out of different schools in different locations.

The stories, therefore, are motivating us to question how marginalisation and drop-out are articulated and understood, as well as the relationship between these. It could be argued that these girls were experiencing ‘persistent’ disadvantage even during the times when ‘life was good’, and that it is this disadvantage that made them more vulnerable to unpredictable shifts in circumstance, but this denies the girls the right to experience or talk about their reality on their own terms. A capability framing might consider this a case of ‘adapted preferences’, where persistent disadvantage leads to a distorted sense of the freedoms necessary for well-being (Sen, Citation1984), but the iterative nature of the research approach and the diverse opportunities it provided for articulating and discussing different periods in their lives suggested that Linda’s experiences with her grandparents and Busi’s time in the private school and when her mother was working were genuinely positive, financially secure and emotionally fulfilling periods. This is important because eligibility criteria for programmes offering support to girls might miss those who are – even briefly – on the other side. At multiple points in their lives these girls could not be positioned on a marginalisation framework and there would be no reason to believe they were ‘at risk’ of drop out. This suggests that girls’ lives need to be seen in more dimensions – including intertemporally – than simply ‘marginalised’ and ‘not marginalised’ if interventions are to have long-term and sustainable impact, and not just catch those who have slipped into a position determined as marginalised at a particular moment in time.

School and perceived capability

The mobility of girls across marginalisation boundaries and their movement in and out of formal schooling moves the debate beyond whether education expands or limits capabilities for the future: ‘Theories need to be viewed not just as background context to an evaluative space, but as having profound implications for how that space is understood’ (Unterhalter, Citation2007, p. 8). In this section we show how the stories give us a richer understanding of the multiple ways the ‘space’ of formal schooling is understood by girls who cannot access it. We outline three key capabilities school represents, not just in relation to their future, but to their ‘now’.

The capability to aspire

The girls positioned school as an opportunity that would directly facilitate the realisation of their personal, professional and economic aspirations. This instrumental perspective (Dreze & Sen, Citation1999) was visible across all of the stories:

When I was growing up, I wished to have my own beautiful, big house and a nice car. But [now I am not in school] that will not be possible. (Linda)

I want to stay [at school] until university and become a lawyer. I want to earn my own money so I can help my family. (Batsi)

School was valued for the ways it was thought to expand social and economic opportunities, and provide a comfortable life, an interesting career and support for their families. But there was little engagement with the idea that these opportunities might be dependent on the regularity of their attendance, the abilities and attendance of their teachers, gender discrimination within classes, the resources available in school for teaching, or their own abilities or performance in national exams – in capabilities language, the ‘conversion factors’ (Sen, Citation2000) that transform opportunities into achievements – all of which are highly likely to be challenges for girls who are in school.

Instead of having instrumental value for the girls, therefore, school offered instrumental promise. Girls were able to imagine and hope for alternative futures through socialising with peers and having exposure to other adult role models: school expanded the girls’ aspiration horizons by offering opportunities for seeing themselves in different ways (Appadurai, Citation2004; Mkwananzi, Citation2013; Ray, Citation2006). Dropping out forced an abrupt narrowing of these expanded horizons:

I was excited because my friends and I had promised each other that we would be attending secondary school together … [after being told I could not continue with schooling]. My heart was pained. I was going to be left behind [… .] Did this mean I would live a life of farming? […] I knew now I might never be a soldier. (Paida)

By offering a space for aspirations to flourish, school supported the capability to aspire (Nussbaum, Citation2000; Hart, Citation2016) and membership in a community where aspirations could be experimented with and hoped for.

The capability to belong

This sense of membership was significant in other ways, too. The value of school as a site of belonging was evident through the stories:

School was fun because we never had to be chased away. (Buhle)

I loved carrying my school trunk. I liked wearing my uniform because it was beautiful and it suit [sic] me well, our uniform was also unique to our school. (Busi)

For girls whose home lives had been disrupted and difficult, school represented a space of friendship and care that they bitterly missed now they were unable to access it:

Even when I was at school and did not have a book or pen, sometimes no food, my teacher gave me all this. (Danai)

The severing of these membership ties and perceived narrowing of future possibilities were experienced traumatically:

The last words from the school headmaster were “my child, one day it will be well”. This hurt me a lot. It hurt thinking about what was different between me and all the other students that I was leaving behind at school. I asked myself a lot of questions but there was no one who could answer. (Busi)

[My father] looked at my stepmother, who said there was no money for school for me […]. She said: “Maybe you will continue with school after your siblings have completed. With the disability that you have, you will not be able to help us in any way.” When I heard those words, I was so hurt. I went out feeling like a chicken that had been rained on. I went to bed in the girls’ hut. I continued crying. I thought of drinking poison to kill myself, but at that moment, I fell asleep. (Rutenda)

The notion of school as a site of belonging can also be identified in reports from an accelerated-learning programme for out-of-school children in Zimbabwe that located classes within school buildings and provided uniforms – two factors that were repeatedly referenced in young people’s reflections on why the programme was important to them (MoPSE, Citation2019). Especially when the girls were experiencing uncertainty in other areas of their lives, school represented a space of stability and affiliation.

The capability to conform

Busi and Rutenda’s excerpts illustrate how access to school represents wider notions of fairness and equality, but being in school was positioned through all of the stories as a state that marked a girl and her family out as being ‘ok’.

[My school friends and I] spoke about a lot of different things about life, especially that getting married was not the way to solve poverty. But many people at the school had never known what poverty looked like. This advice was for other girls. (Busi)

The stories framed the girls’ intermittent periods in school as times in their lives that were freer from the embarrassment of being poor, and where they had the freedom to be children without the additional responsibilities they were required to take on when their family was going through a difficult time:

We had school shoes and everything else that was needed. Our school fees were paid on time. When we brought homework from school, we got help, so life was good. When we got home from school, my mother would have done everything, we would come back and sit. (Buhle)

… at school, we lived in nice houses. We ate good food. All we had to do was learn and eat. (Busi)

As the girls’ school attendance tended to be one of the first things to be cut when a family was experiencing challenges, being in school served as a litmus paper for how well the whole family was doing:

I remember coming from school, my mother sat me down and told me that my father has been imprisoned. I was so much pained and I cried, and my mother told me I cannot proceed [with] school. (Batsi)

As being in school represented a lack of problems elsewhere in the girls’ lives, re-joining school was aspired to because it was a sign of life getting back on track:

I [now] live with my aunt and her five children. Three are at school [… .] The twins are infants but they will go to school soon [… .] As I work with my aunt, I hope that when we make enough money she will also be able to take me to school [with my cousins]. (Danai)

The capability to conform was shaped by past, present and perceived future interactions of capabilities, conversion factors and agency, and was closely associated with the capability to aspire: a demonstration of how capabilities can be interdependent (Buckler, Citation2015; Walker, Citation2006). For the girls, having aspirations was in itself a symbol of conformity and being in school offered the potential capability to advance the instrumental promise of school for a more stable, conforming future.

Perceptions of the limitations of capability offered through school

Despite the high value placed on attending school across all the stories, two girls were clear that it was not the solution to their challenges. These girls expressed more agency in decisions around attendance and drop-out than is commonly reported. For example, Gugu was unexpectedly allowed to continue attending school after her mother died, but it added to the complex challenges she was dealing with at home:

I had the idea of moving in with my stepmother and father. But my stepmother was very abusive and did not like us. As I went to school, my siblings remained home […] and they would be abused and they were not given food. So even in class I was not able to concentrate as I thought of my siblings at home. I wondered what our stepmother was doing to them in my absence. (Gugu)

Gugu chose to leave school in order to move her siblings out of her stepmother’s house and take care of them herself. For some girls, as we saw earlier, school was a sign that things were going well at home, but when things were not going well at home school could frustrate their capability to deal with additional responsibilities or pursue what was most important to them at that particular time. As shown earlier, capabilities can be interdependent where the realisation of one can lead to the realisation of others. So too can the realisation of one capability diminish the possibility of others being achievable (Buckler, Citation2015): there can be a ‘trade-off’ between positive and negative freedoms (Walker & Unterhalter, Citation2007, p. 11).

Another girl, Gamuchirai, struggled to pay the bus fare to school and, encouraged by her friends, initiated a relationship with a driver. She became pregnant and estranged from her family. She moved in with the driver, but their baby died, and he became abusive and violent. Gamuchirai escaped, reunited with her family, returned to school and paid her fees by selling vegetables. She is now the family breadwinner and main carer for her elderly parents. While she has completed school, her exam results will not be released until she pays $50. This is far beyond her saving capacity, but she cannot apply for a better-paid job without these results. Against extraordinary odds, Gamuchirai completed formal schooling, but is in limbo, with extremely limited capability. For her, school has failed to fulfil its instrumental promise as a facilitator of a better future.

Reflections and conclusions

The point of this article is not to argue against the pursuit of formal schooling. We believe that governments and funders should continue to strive to expand capacity and improve the experience of schools. As researchers and practitioners we will continue to proactively contribute to this agenda. But we have attempted to show that we should not strive for this at the expense of thinking creatively and inclusively about how to support young people who are unrecognised in this pursuit.

The girls’ stories illustrate agentic lives lived across both sides of the marginalisation boundary (as it is currently framed) and stop–start experiences of schooling which is valued more for its normative status and instrumental promise than for its practical potential. The girls’ marginalisation is not characterised by persistent poverty, but by persistent unpredictability; in this context, formal schooling represents, rather than facilitates, stability. The stories also show how girls experience unpredictable shifts, and how and where they have agency to alleviate the impacts on them and those they care for. For example, Gugu chose to leave school because doing so meant she could pursue other, more urgent, capabilities (protecting her siblings). Gamuchirai made the decision to return to school and independently curated the circumstances to facilitate and fund this.

Understanding more about how girls make decisions about their education, and who else’s needs they might need to consider is important: these stories challenge the internal logic of ‘quick fix’ education initiatives focused on ‘target’ individuals, and demonstrate the need for more holistic, systemic, longitudinal approaches for supporting girls’ learning and development within the intertemporal dynamics of their lives: the individualised framing of many policies and campaigns do not adequately take into consideration girls’ interactions with family, different locations and relationships and how fluid these can be over the relatively short period in which most formal schooling is available. The (long-term) future-looking perspective of these campaigns, which emphasise how girls who have received a formal education will have capabilities for more agency and autonomy, to navigate better relationships and ‘contribute to their communities’ as adults (World Bank, Citation2021, p. 1), can under-value girls’ existing capabilities for these pursuits. The stories suggest that these campaigns also fail to recognise how formal schooling – as it currently exists – can undermine capabilities they already have in these areas.

While programmes do increasingly work with communities to bolster support for girls’ education, they could focus more attention on how the meaning of school and values associated with it might change for girls as their relationships within their communities change in response to disruptive events. As Nussbaum (Citation2004, p. 345) suggests, the problem of education ‘cannot be stably solved without raising the living standard of the poor in each nation’; similarly, the girls’ stories suggest that education initiatives will have a greater positive effect on girls’ lives if they work in tandem with broader attempts to stabilise the unpredictable nature of these lives beyond school, or at the very least be designed to adapt to this unpredictability.

We started this research open to the idea that schooling might not feature strongly in the girls’ valued capabilities. It did, just not in quite the way that is often assumed, and not for the reasons that school is promoted as valuable to a global audience and to the girls themselves. School is desperately sought by most of the girls and missed awfully when it is taken away. However, the stories surface girls’ perceptions around the value(s) school adds to their lives: it supports the capability to aspire (by offering a space to consider and hope for alternative futures), to belong (by offering access to a shared identity distinct from the limitations of their home environment) and to conform (by representing household-level financial and social security and stability and, for some, what is seen to be a more normal experience of childhood). Alternative education programmes that can integrate into the dynamic nature of girls’ lives, and that are designed to inspire feelings of stability, membership and hope, may encourage enrolment and sustainability. A storytelling approach has helped to shift attention away from the assumption that an educated girl will (or indeed will want to) ‘fix the world’ (Chant & Sweetman, Citation2012, p. 527) and offer insights into what school supports girls to do and be in the ‘now’. Focusing on valued outcomes of education programmes remains important, but the wider, unstable contexts of these girls’ lives offer them little opportunity to imagine or plan for the long term. Recognising that they have more agency than is often suggested around short-term decisions, however, could be an additional dimension for programmes to focus on.

We have written elsewhere (Buckler, Mkwananzi, Chamberlain, & Dean, Citation2019) how the storytelling process facilitated time and the building of a level of trust with the girls that would have been impossible if we had visited their communities to interview them. It also showcased ways in which the girls are more articulate and capable than could ever be captured by the standardised tests that are widely used to generate an understanding of children’s abilities. One girl said she could not read and then later talked about reading the Bible in church. When asked about this contradiction she exclaimed, ‘Oh, I can read the Bible, just not school books!’ Given that most had only had a few years of intermittent schooling, their capacity for creativity in terms of metaphor, poetry, symbolism and art, as well as critical thinking, collaboration problem-solving, emotional intelligence and, of course, information and communication (ICT) literacy was astonishing. A common reflection from the story screenings with practitioners in girls’ education has been what their peers are missing out on by not having these girls attend school, and how these skills, which are critical elements of the twenty-first century skills agenda (UNESCO, Citation2021), are invisible to or under-valued by schools, education programmes, standardised testing and the girls themselves. Recognising, valuing and adding value to these ‘invisible’ skills is something important that alternative education programmes, less restricted by formal curriculum requirements, can focus on, and in doing so, challenge how formal schools operate and what is taught and valued within them. It also bolsters the call for more creative ways of assessing ‘learning’. Storytelling, analysed through a capabilities lens, therefore has offered insights into what additional ‘informational broadening’ (Sen, Citation1999, p. 253) might be necessary in considering why school matters, what matters to girls within school, and how what matters can be captured to develop policies and programmes for education opportunities that are more compatible with the realities of girls’ lives and values.

These reflections have been taken up by the SAGE programme, which is drawing on the research to shape the content of the learning materials to enhance their appeal and relevance to girls in similar contexts and develop parallel, qualitative approaches for capturing learning distinct from standardised literacy tests. We appreciate Plan’s openness and enthusiasm for a research approach that did not set out to generate ‘answers’, but spaces for a ‘confluence of interpretations’, recognising that this could ‘question mainstream evidence and its normative underpinnings’ (Vandekinderen, Roets, Van Keer, & Roose, Citation2017, p. 274). This openness is even more important in the context of Covid-19, where the combination of sudden, exacerbated economic hardship and school closures is a major threat to girls’ access to formal schooling, and where alternative education programmes will need to become increasingly mainstream.

A postscript: One of the anonymous reviewers of this paper asked what the girls felt about their finished stories, and what happened next. The screening at the end of the workshop was a happy, high-energy event – as is often the case after a storytelling research workshop, which can be consuming and emotional for participants and facilitators. The release and sense of achievement when the stories are ‘finished’ is palpable. The girls were sad to leave the workshop, proud of their stories, and asked pertinent, challenging questions about what we were going to do with them (see Chamberlain et al., Citation2021). What has happened next, however, is inextricably bound up with the ideas we share in this paper about the vulnerability of girls on the marginalisation boundary to the unpredictability of their environment. The research was designed as a three-year project that would follow the girls through the alternative education programme, but the second workshop has had to be postponed due to Covid-19. The research team recently contacted the girls to explore whether (after so much time) they would still be interested in participating in a second workshop when it is safe to do so. We have been able to locate seven of the girls; the other four have moved away or are temporarily living in another country. Since the first workshop, three of the seven have got married and two of these have had a child. One other girl has had a child but is not living with the father. Five of the girls have enrolled on the alternative education programme, two have not. All are enthusiastic about the idea of continuing with the research and generating new stories about their lives. These new stories will no doubt, and importantly, challenge the ways we have written about their lives in relation to how they articulated them two years ago.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the FCDO for their feedback on a draft of this paper, but would like to emphasise that the views expressed are those of the research team and not necessarily the FCDO. We would like to thank Lizwe Sibanda, Tafadzwa Mhou and Precious Babbage from Plan International, Zimbabwe for their valued research support. We would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their contributions and insights. Most of all we thank the 11 girls who shared their stories. Thank you to Dr Joanna Wheeler who was an advisor for the research and helped to adapt the storytelling approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The programme and research are working specifically with adolescent girls. From this point, we use ‘girls’ as a shorthand.

2. In other publications we describe our conceptual framework for exploring capabilities, aspiration and education through a sociocultural lens in more detail (Buckler, Citation2019; Chamberlain et al., Citation2021).

3. SAGE aims to support 20,000 out-of-school girls through accelerated learning activities. The research strand is funded by the programme and is distinct from (although informed by) core monitoring and evaluation activity. The research participants represented a diverse cohort that incorporated SAGE’s target groups. Two thirds were Shona speakers, one third Ndebele speakers, two had physical impairments, one had a learning disability, two were from apostolic communities and three were mothers. These were not discrete categories; girls were affiliated with multiple groups.

4. Girls were invited to bring their child and a friend or family member with them to assist with childcare. All costs associated with childcare were covered by the research budget.

5. See acknowledgements for the names of the research team members.

6. The research was approved by The Open University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/3193), as well as Open University and Plan risk assessment and safeguarding panels. More details about ethical considerations are covered in the text and subsequent footnotes.

7. These activities were multi-modal and included collage, drawing, drama, clay modelling and an activity called ‘story-scape’, where participants create a ‘scene’ from their story in a box using craft materials and locally available resources (e.g. rocks, plants, artefacts) incorporating literal and metaphorical representations, with thought given to the colours, textures, size and positioning of the ‘characters’ and backdrop. At regular points in the workshop the girls told the latest version of their story in a story circle, where the other girls would offer advice on how to develop it. The activities drew on and were adapted from Wheeler’s storytelling approach (Citation2018).

8. A more comprehensive analysis workshop was planned with the girls, but this has been postponed due to Covid-19. A further paper will be developed which builds in their contribution to analysis and combines it with updated stories from the girls.

9. The research adopted Wheeler et al.’s (Citation2018) staged-consent process. Girls consented to participate in the workshop in advance, but at the end after the completion of their story, they were asked to choose a level of consent for the use of their story. These ranged from the story not being shown to anyone else outside of the research team (which no one chose) to the story being available online. (While three girls did consent to this, we do not intend to action this until after the three-year project has concluded, and consent for this will be revisited). All girls selected the option of their stories being shown at closed screening events aimed at people with a professional interest. It is also important to emphasise that no images of the girls were included in the digital stories. Some girls chose to include their first name, others chose not to.

10. The stories were shown at a range of academic and Plan International events. The main screening event took place in February 2020 with approximately 80 audience members (in-person and online) from non-governmental organisations (NGO) and academic institutions. Reflections on the stories were captured informally at the smaller events, and through a feedback form sent to invitees of the main screening. The feedback form included prompt questions such as how the stories made them feel, whether anything surprised them about the stories and how the stories helped them to reflect on their work. Ten feedback forms were returned, containing rich and detailed reflections which substantiated and shaped the analysis from stages one and two.

References

- Ansell, N. (2004). Secondary schooling and rural youth transitions in Lesotho and Zimbabwe. Youth & Society, 36(2), 183–202.

- Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire. In, M. Walton & V. Rao (Eds.), Culture and public action (pp. 59–84). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Benjamin, W. (1968). Illuminations. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace and World.

- Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Buckler, A., Mkwananzi, F., Chamberlain, L., & Dean, C. (2019, October 3) Inclusive ways of knowing? Problematising the relationship between research and the design of inclusive education, UKFIET. Retrieved 4 October 2019 from https://tinyurl.com/ybbca938

- Buckler, A., Stutchbury, K., Wilson, G. K., Cullen, J., & Kaije, D. (2021). What prevents teacher educators from accessing professional development OER? Storytelling and professional identity in Ugandan Teacher colleges. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(1), 10–26.

- Buckler, A. (2015). Quality teaching and the capability approach: Evaluating the work and governance of women teachers in rural sub-Saharan Africa. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Buckler, A. (2019). Being and becoming in teacher education: Student teachers’ freedom to learn in a college of education in Ghana. Compare, 50(6), 844–864.

- Cameron, J. (2012). Capabilities and the global challenges of girls’ school enrolment and women’s literacy. Cambridge Journal of Education, 42(3), 297–306.

- Camfed. (2020) Campaign for female education website. Retrieved 23 February 2021 from https://camfed.org/

- Chamberlain, L., Buckler, A., & Mkwananzi, F. (2021). Building a case for inclusive ways of knowing through a case study of a cross-cultural research project of out-of-school girls’ aspirations in Zimbabwe: Practitioners’ perspectives’. In, A. Fox, H. Busher, & C. Capewell (Eds.), Thinking critically and ethically about research for education: Engaging with voice and empowerment in international contexts. London: Routledge (in press).

- Chant, S., & Sweetman, C. (2012). Fixing women or fixing the world? “Smart economics”, efficiency approaches, and gender equality in development. Gender and Development, 20(3), 517–529.

- Charaf, A. (2019). Youth and changing realities: Perspectives from Southern Africa. Paris: UNESCO.

- Chinyoka, K. (2014). Causes of school drop-out among ordinary level learners in a resettlement area in Masvingo, Zimbabwe. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 5(3), 294–300.

- Cin, F. M., & Walker, M. (2016). Reconsidering girls’ education in Turkey from a capabilities and feminist perspective. International Journal of Educational Development, 49, 134–143.

- Commonwealth. (2018). Commonwealth Women’s Forum 2018 Report. Retrieved 14 November 2019 from https://thecommonwealth.org/sites/default/files/inline/D16377_CW_Womens_Forum.pdf

- CREATE. (2011) Making rights realities: Researching educational access, transitions and equity, CREATE consortium. Retrieved 12 August 2019 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08aede5274a31e0000866/Making-Rights-Realities-Keith-Lewin-September-2011.pdf

- Dakwa, F. E., Chiome, C., & Chabaya, R. A. (2014). Poverty-related causes of school dropout- dilemma of the girl child in rural Zimbabwe. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 3(1), 233–242.

- Datta, R. (2018). Traditional storytelling: Effective indigenous methodology and implications for environmental research. AlterNative, 14(1), 35–44.

- DeJaeghere, J. (2016). Girls’ educational aspirations and agency: Imagining alternative futures through schooling in a low-resourced Tanzanian community. Critical Studies in Education, 59(2), 237–255.

- Dreze, A., & Sen, A. (1999). India: Economic development and social opportunity. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Dutt, S. (2010). Girls’ education as freedom? Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 17(1), 25–48.

- Enarson, E. (2000). Gender and natural disasters. Working paper no. 1, In focus programme on crisis response and reconstruction. Geneva: International Labour Organisation. Retrieved 15 September 2019 from https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/WCMS_116391/lang–en/index.htm

- Fambasayi, R. (2020) Zimbabwe’s education law now does more for children, but there are still gaps. The conversation. Retrieved 9 September 2020 from https://theconversation.com/zimbabwes-education-law-now-does-more-for-children-but-there-are-still-gaps-145265

- GEC. (2018a). Understanding and addressing educational marginalisation: A new conceptual framework for educational marginalisation. Girls Education Challenge Thematic Review. Retrieved 12 December 2020 from https://dfid-gec-api.s3.amazonaws.com/linked-resources/Thematic-Review-Addressing-Educational-Marginalisation-Part-1.pdf

- GEC. (2018b). Steps to success: Learning from the Girls’ Education Challenge 2012-2017. Retrieved 12 December 2020 from https://dfid-gec-api.s3.amazonaws.com/linked-resources/GEC_S2S_report_final.pdf

- GEC. (2018c). Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) self-assessment tool for projects: Guidance document. Retrieved 12 December 2020 from https://dfid-gec-api.s3.amazonaws.com/production/assets/27/GESI_Tool_External_October_2019.pdf

- GEC. (2019, December). Lessons from the field: Alternatives to formal education for marginalised girls. Girls’ Education Challenge Report. Retrieved 12 December 2020 from https://dfid-gec-api.s3.amazonaws.com/production/assets/29/LFTF_ALP_December_2019_Final.pdf

- Giovanola, B. (2005). Personhood and human richness: good and wellbeing in the capability approach and beyond. Review of Social Economy, 63(2), 249–269.

- Gordon, R., Marston, L., Rose, P., & Zubairi, A. (2019). 12 years of quality education for all girls: A commonwealth perspective. Cambridge: REAL Centre, University of Cambridge.

- Griffin, J. (2008). On Human Rights. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hart, C. J. (2013). Aspirations, education and social justice: Applying Sen and Bourdieu. London/New York: Bloomsbury.

- Hart, C. S. (2016). How do aspirations matter? Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 17(3), 324–341.

- Human Rights Watch. (2017). Africa: Make girls’ access to education a reality. Retrieved 9 September 2021 from https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/16/africa-make-girls-access-education-reality

- Inoue, K., Di Gropello, E., Taylor, Y. S., & Gresham, J. (2015). Out-of-school youth in Sub-Saharan Africa: A policy perspective, directions in development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Iseke, J. (2013). Indigenous storytelling as research. International Review of Qualitative Research, 6, 559–577.

- Jackson, M. (2013). The politics of storytelling. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Khoja-Moolji, S. (2016). Doing the ‘work of hearing’: Girls’ voices in transnational educational development campaigns. Compare, 46(5), 745–763.

- Kruss, G., & Wildschut, A. (2016). How does social inequality continue to influence young people’s trajectories through the apprenticeship pathway system in South Africa? An analytical approach. Journal of Education and Work, 29(7), 857–876.

- Liao, S. M. (2010). Agency and human rights. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 27(1), 15–25.

- Mandina, S. (2013). School based factors and the dropout phenomenon: A study of Zhomba cluster secondary schools in Gokwe district of Zimbabwe. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 3(1), 51–60.

- Matsumoto, M. (2018). Technical and vocational education and training and marginalised youths in post-conflict Sierra Leone: Trainees’ experiences and capacity to aspire. Research in Comparative and International Education, 13(4), 534–550.

- Mawere, M. (2012). Girl child dropouts in Zimbabwe secondary schools: A case study of Chadzamira Secondary School in Gutu district. International Journal of Politics and Good Governance, 3(3), 1–14.

- Mayo, P. (2004). Liberating praxis: Paulo Freire’s legacy for radical education and politics. West Port, CT: Praeger.

- Mkwananzi, F. (2013). Challenges for vulnerable young people in accessing higher education: A case study of orange farm informal settlement, South Africa (Unpublished Masters Dissertation). Centre for Development Support, University of the Free State.

- Mkwananzi, F. (2019). Higher education, youth, and migration in contexts of disadvantage: Understanding aspirations and capabilities. London: Palgrave McMillan.

- MoPSE. (2019) Zimbabwe Accelerated Learning Programme (ZALP): Giving out-of-school children a second-chance. Retrieved 2 April 2020 from http://bantwana.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Zimbabwe-Accelerated-Learning-Programme-Out-of-School-Children-Second-Chance.pdf

- Moyo, S., Ncube, D., & Khuphe, M. (2016). An assessment of factors contributing to high secondary school pupils dropout rates in Zimbabwe, A case of Bulilima District. Global Journal of Advanced Research, 3(9), 855–863.

- Mukwambo, P. (2019) Human development and perceptions of secondary education in rural Africa: A Zimbabwean case study. Compare (awaiting issue allocation).

- Ngwenya, V. C. (2016). The best way of collecting fees without infringing on the liberties of learners in Zimbabwean primary schools. International Journal of Research in Business Technologies, 8(3), 974–981.

- Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and human development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. (2004). Women’s Education: A Global Challenge. In F. Lionnet, O. Nnaemeka, S. Perry, C. Schenck (eds) Signs, 29(2), 325–355.

- Porter, G., Hampshire, K., Mashiri, M., Dube, S., & Maponya, G. (2010). Youthscapes’ and escapes in rural Africa: Education, mobility and livelihood trajectories for young people in Eastern Cape, South Africa. Journal of International Development, 22(8), 1090–1101.

- Posti-Ahokas, H. 2014. Tanzanian Female Students’ Perspectives on the Relevance of Secondary Education (Academic dissertation). University of Helsinki.

- Ray, D. (2006). Aspirations, poverty, and economic change. In, A. V. Banerjee, R. Benabo, & D. Mookherjee (Eds.), Understanding poverty (pp. 409–421). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Raynor, J. (2007). Education and capabilities in Bangladesh. In, M. Walker & E. Unterhalter (Eds.), Amartya Sen’s capability approach and social justice in education (pp. 157–176). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Robeyns, I. (2005). The Capability Approach: a theoretical survey. Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 93–117.

- Robeyns, I. (2016). Capabilitarianism. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 17(3), 397–414.

- Robeyns, I. (2017). Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: The capability approach re-examined. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers.

- Sabates, R., Akyeampong, K., Westbrook, J., & Hunt, F. (2010) School drop-out: patterns, causes, changes and policies, paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2011, The hidden crisis: Armed conflict and education.

- Seeberg, V. (2014). Girls’ schooling empowerment in rural China: Identifying capabilities and social change in the village. Comparative Education Review, 58(4), 678–707.

- Sen, A. (1984). Resources, values and development. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Sen, A. (1992). Inequality re-examined. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. (2000). A decade of human development. Journal of Human Development, 1(1), 17–23.

- Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. London: Penguin.

- Stern, M. J., & Seifert, S. C. (2013). Creative capabilities and community capacity. In, H. U. Otto & H. Ziegler (Eds.), Enhancing capabilities: The role of social institutions (pp. 179–196). Berlin, Toronto: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

- Theirworld. (2017, October 11) 13 reasons why girls are not in school in International day of the girl child. Retrieved 4 March 2010 from https://theirworld.org/news/13-reasons-why-girls-are-not-in-school

- Tijerina, A. (1998, May) Why do girls drop out? Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA). Retrieved 19 November 2019 from https://www.idra.org/resource-center/why-do-girls-drop-out/

- UK Government. (2019, September 24). PM steps up UK effort to get every girl in the world into school. Prime Minister’s Office, Press Release. Retrieved 3 December 2020 from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-steps-up-uk-effort-to-get-every-girl-in-the-world-into-school

- UK Government. (2021, May 03) G7 to boost girls’ education and women’s employment in recovery from COVID-19 pandemic, Foreign Affairs news story. Retrieved 3 December 2020 from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/g7-to-boost-girls-education-and-womens-employment-in-recovery-from-covid-19-pandemic

- UNESCO (2010). Reaching the Marginalized, Education for All Global Monitoring Report. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. (2020). Survival rate by grade. UNESCO Glossary. Retrieved 3 December 2020 from http://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/survival-rate-grade

- UNESCO. (2021). 21st century skills, UNESCO Glossary. Retrieved 9 September 2021 from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/en/glossary-curriculum-terminology/t/twenty-first-century-skills

- UNICEF. (2018). The Out-of-School Children initiative (OOSCI). Evaluation Report. New York: Author. Retrieved 3 December 2020 from https://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/files/Formative_Evaluation_of_the_Out-of-School_Children_Initiative_OOSCI.pdf

- Unterhalter, E. (2007). The capabilities approach and gendered education: An examination of South African complexities. Theory and Research in Education, 1(1), 7–22.

- Unterhalter, E. (2012). Inequality, capabilities and poverty in four African countries: Girls’ voice, schooling, and strategies for institutional change. Cambridge Journal of Education, 42(3), 307–325.

- Van Diesen, A. (1998). Keeping hold of the stick and handing over the carrot: Dilemmas arising when development agencies use PRA. In, B. Boog, H. Coenen, L. Keune, & R. Lammerts (Eds.), The complexity of relationships in action research (pp. 37–50). Tilburg: Tilburg University press.

- Vandekinderen, C., Roets, G., Van Keer, H., & Roose, R. (2017). Participation and participatory research from a capability perspective. In, O. Hans-Uwe, V. Egdell, J.-M. Bonvin, & R. Atzmüller (Eds.), Empowering young people in disempowering times: Fighting inequality through capability oriented policy (pp. 274–292). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Press.

- Vaughan, R. (2007). Measuring capabilities: An example from girls’ schooling. In, M. Walker & E. Unterhalter (Eds.), Amartya Sen’s capability approach and social justice in education (pp. 109–130). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Walker, M., & Unterhalter, E. (2007). Amartya Sen’s capability approach and social justice in education. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Walker, M. (2006). Towards a capability-based theory of social justice for education policy making. Journal of Education Policy, 21(2), 163–185.

- Walker, M. (2007). Selecting capabilities for gender equality in education. In, M. Walker & E. Unterhalter (Eds.), Amartya Sen’s capability approach and social justice in education (pp. 177–195). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Webster, L., & Mertova, P. (2007). Using narrative inquiry as a research method: Introduction to using critical event narrative analysis in research on learning and teaching. London: Routledge.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wheeler, J., & Bivens, F. (2021). Storytelling as participatory research. In, D. Burns, J. Howard, & S. Ospina Eds., Sage handbook of participatory research and inquiry (pp. 649–662). Oxford: Sage.

- Wheeler, J., Shahrokh, T., & Derakhshani, N. (2018). Transformative storywork: Creative pathways for social transformation. In, and J. Servaes (Ed.), Handbook of communication and participatory development (pp. 1–22). London: Springer.

- Wodon, Q. (2018, August 1) Why do girls drop out of school and what are the consequences of dropping out? Medium. Retrieved 3 December 2020 from https://medium.com/world-of-opportunity/why-do-girls-drop-out-of-school-f2762389a07e

- World Bank. (2018). Learning to realize education’s promise. Washington, DC: Author.

- World Bank. (2021) Girls’ education. Retrieved 17 April 2021 from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/girlseducation

- Zipin, L., Sellar, S., Brennan, M., & Gale, T. (2015). Educating for futures in marginalized regions: A sociological framework for rethinking and researching aspirations. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(3), 227–246.