ABSTRACT

Student agency in assessment is evident when students make assessment choices, and their voices inform decisions. This paper presents an in-depth case study of a high performing school that sought student voice to reform its assessment culture to enhance student agency. Secondary students in an Australian school were invited to draw a visual metaphor: if assessment were a food, what would it be? Responses were analysed to identify: What can be learnt about assessment culture from students’ drawings and comments? And how did student voice inform changes in school assessment practices and assessment culture? Six years later, the student ideas were revisited by a school leader to identify how cultural and structural conditions for student agency within the assessment culture had changed. Using visual methodologies with students provided insightful commentary on how assessment practices may be modified to support learning and the challenges of engaging in assessment culture reform.

Introduction

Students provide important insights when consulted on assessment change, yet their perspectives are not sought very often (Barrance & Elwood, Citation2018; Elwood et al., Citation2017). Instead, top-down policy changes usually drive assessment culture change in a school, often with unwanted side effects like accountability pressures; reduced teacher and student wellbeing; and narrowed curriculum (Klenowski & Wyatt-Smith, Citation2012; Spina, Citation2019). In this case study an Australian school used a top-down assessment policy change as an opportunity to rethink how assessment impacts student wellbeing and agency.

Student agency is increasingly linked to wellbeing. Students are envisioned to be agentic in personal and collective activity as they respond to global challenges and create collective wellbeing (OECD, Citationn.d.). Agency occurs when individuals have the opportunity and power to make choices within their social contexts. Yet students’ agentic assessment actions always occur ‘within temporal-relational contexts of activity’ (L. E. Adie et al., Citation2018, p. 3). School assessment is controlled by teachers and examination boards. These cultures and structures can communicate that only some domesticated types of agentic aspiration are permissible (Consuelo et al., Citation2020) and only for some students (Woods et al., Citation2019). Adept students, especially girls, can learn that agency means compliance when these forms of agentic identities are rewarded by their school culture (Martin, Citation2016). Agentic students may find that teachers do not recognise or value their assessment choices (Charteris & Thomas, Citation2017; Harris et al., Citation2018). Agency that challenges the school assessment culture is also risky for students who rely on assessment results to access opportunities beyond school.

Invitations for students to have greater agency in assessment can be in tension with strong cultural pressures to perform, fear of failure and assessment anxiety (Burcaş & Creţu, Citation2021). Burcaş and Creţu (Citation2021) noted as many as 60% of students experience assessment anxiety. Girls are often over-represented despite having coping and preparation strategies (Putwain & Daly, Citation2014). This case study in a non-selective, independent girls’ school catering for Years 7–12 (ages 12–18) in Queensland, Australia was a multi-year inquiry focused on assessment change (L. Adie et al., Citation2021; Willis et al., Citation2019). It followed two lines of inquiry:

What can be learnt about assessment culture from students’ drawings and comments about assessment?

How did student voice inform changes in school assessment practices and assessment culture?

The school’s goal was to pivot their assessment culture towards one that focused on assessment for learning, at a time when government top-down policy change was introducing more testing.

Top-down assessment change as opportunity

The new assessment processes in Queensland for senior years in 2020 included the introduction of a common external exam. The processes described in disrupted the status quo enough for schools to reconsider traditional assessment practices.

Table 1. Changes in the Queensland Senior Assessment system.

After 50 years, secondary schools were contemplating how to prepare students for a high-stakes externally designed and marked assessment task. Some schools scheduled more practice examinations in junior grades to prepare students for the new assessment conditions. Other schools, such as this case study school, began to question how to prepare students to be agentic to respond to unknown assessment prompts.

Agency and cultural change

Culture change is risky, especially when the school is regarded as successful and high performing (L. Adie et al., Citation2021). Culture shapes assessment practices, relationships and effects for individuals usually demonstrated through sociocultural theories (L. Adie & Willis, Citation2016; L. Adie et al., Citation2021; Allal, Citation2016; Cowie et al., Citation2018). To more directly consider interrelationships with agency, culture and broader structural change, Margaret Archer’s (Citation1996, Citation2000) sociological theories are employed. Assessment research draws on a range of theories, with Black and Wiliam (Citation1998) borrowing from systems engineering to view classroom assessment and learning as a black box, and Pryor and Crossouard (Citation2008) applying the cultural-historical school of theories. Theory provides concepts to understand the social processes and construction of meaning (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021), in this case to articulate relationships among assessment structures, culture and student agency.

Archer proposes that change happens when the agency of people interacts with structures that pre-date and post-date action, so that agency, culture and structure ‘emerge, intertwine and redefine’ one another (Archer & Morgan, Citation2020, p. 184). Culture is more than the background of ‘community of shared meanings … [found in the] principal ideational elements (knowledge, belief, norms, language, mythology) that are shared within a social unit’ (1996, p. 4). Archer additionally focuses on the interactions with ‘people as active makers and re-makers of their culture’ (p. 184). Cultural change occurs when the cultural ideas and structural systems begin to change through the actions of reflexive agents: structural systems as materially grounded, and cultural systems as ideationally grounded. They are interrelated, as structural systems use material ways to reproduce ideas and so reproduce the cultural organisation of a group. As structures and cultures are experiencing rapid change, individuals need greater reliance on their reflexive powers to make choices by discerning the options, deliberating and dedicating themselves to courses of action (Archer, Citation2012). These reflexive decisions occur in cultural and structural conditions that may enable or constrain what is possible, but also may be resisted or reformed by actions of agents.

Assessment is an example of a structural system, as assessment feedback routines, rubrics and reporting programmes are material conditions that create cultures around assessment practices (Allal, Citation2016; Finch & Willis, Citation2021; Pryor & Crossouard, Citation2008). Through their activity, students sustain cultural and structural systems as well as continually modify the culture, as they make decisions to prioritise, accept or resist expectations, a process that Archer calls morphogenesis (2000, 2003). It is a dual evaluation: agents evaluate their situations in light of what matters to them, and they evaluate what is possible in the light of their situations (Archer, Citation2003). There are links to wellbeing as agents seek to make decisions to live a life worth living. Where there is incongruence between an individual’s experiences and their ideational expectations, emotions are typically heightened, and point to important concerns (Archer, Citation2000, p. 207, 210). For a school engaged in assessment culture change and with a focus on student well-being, tapping into these concerns would provide essential information for their decision-making.

Student perspectives were sought as the school was aiming to move from a traditional testing culture towards an assessment culture. These two common cultures of assessment – a testing culture and an assessment culture – are distinguished by Gipps (Citation1994), Birenbaum (Citation2016) and Shepard (Citation2000). A testing culture is often focused on grades and separates teaching from assessing. It is also known as an instrumental culture (Woods et al., Citation2019), data culture (Spina, Citation2019) or institutional or examination performance culture (Wong et al., Citation2020). The testing culture reflects a long history and layers of assessment policy and material structures that represent logics of cultural beliefs. For example, the structure of the individual examination conducted under rigorously controlled conditions was introduced in ancient China and made popular in British colonial contexts through nineteenth-century public-service recruitment processes (Stobart, Citation2008; Wong et al., Citation2020). The material structure of examinations mostly reflected cultural ideas of meritocracy, as competitive ranking and access to higher social status occupations was earned by individuals recalling complex information unassisted and from memory under time pressure. These conditions persist as cultural values long after the historical epochs in which they were developed. The values are kept alive by the interplay of ongoing structures and cultures of assessment practices (Shepard, Citation2000). When contemplating assessment change, attention to the underlying assessment cultures and structures in a school is essential.

An assessment culture that focuses on learning as integral to assessment prioritises the active participation of students in assessment, that is, their agency. Birenbaum (Citation2016), like Pryor and Crossouard (Citation2008), identify that an assessment culture includes a range of practices such as deep learning, the use of assessment to inform teaching and learning, an inquiry approach, dialogue between teachers and students, diversity, collaboration and creativity in assessment design and response, which inevitably informs curriculum and assessment choices. Such priorities require changes to traditional structural and cultural systems (Allal, Citation2016; Woods et al., Citation2019). This paper argues that collaborative inquiry with students into a school’s assessment culture can productively identify how school assessment structures influence opportunities for agency and create opportunities for students to be involved in assessment culture change.

Case study school: changing assessment culture

The academic leaders at the case study school decided that the assessment policy changes were an opportunity to provoke new ways of working and a more student-centred assessment culture. They suspected Year 7 and Year 8 students were feeling overwhelmed by assessment, and approached researchers to collaboratively design research informed inquiries. This article draws on the data analysis of (1) 45 student drawings with annotations, a 20% sample of five drawings randomly selected from each of nine class groups for close collaborative analysis by two school leaders and the researchers; and (2) three focus groups (n = 5 students/group) with students whose drawings were randomly selected so they could talk more about their drawings and interpretations. This sample size was practically manageable for reflexive analysis of the rich data with the school leaders. It was also large enough to be indicative of recurring patterns of meaning across the group (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). Ethical approval was granted by two universities (approval number 1,500,001,126), with written consent given by the school principal, the participating teachers, students and their guardians. Student drawings are a well-established methodology for student voice research; however, few studies are with secondary school students so it is explained in detail.

Visual methods for enabling student voice

Agentic approaches to student voice include finding methodological approaches for students to highlight school concerns that are important to them (Cook-Sather, Citation2018; Gillett-Swan, Citation2018). Drawing enables young people to represent and express how they may see the world a little differently to adults (Mayes et al., Citation2019), and importantly include student oral or written comments (Alerby, Citation2015; Groundwater-Smith & Mockler, Citation2016). Swain et al. (Citation2018) recommend using focus groups with students to triangulate the drawings and words.

Student drawings about assessment have been used alongside student focus group interviews (Carless & Lam, Citation2014; Harris et al., Citation2009) and survey responses (Harris et al., Citation2014). New Zealand Year 5–10 student drawings identified a variety of assessment types and purposes, with variety narrowing among high school students (Harris et al., Citation2009). In Harris et al. (Citation2014), students identified through drawings that feedback was valued, but the range of feedback sources (teachers, peers, self) decreased as students entered secondary school. Carless and Lam (Citation2014) used drawings to investigate the perceptions of assessment of lower primary school students (Year 3) in Hong Kong. Students expressed satisfaction with a good result, but over half of their participants also depicted assessment as an anxiety-laden event.

In Australia student drawings have focused on national assessment in literacy and numeracy (NAPLAN). Drawings were collected in two primary schools with different NAPLAN cultures, where the first school focused on exam preparation and the second did not (Swain et al., Citation2018). The students from the first school generally expressed ‘sadness, fear and anxiety’ during preparation (p. 330), while at the second school, students who were minimally affected by preparation also experienced ‘anxiety’, ‘stress’ and ‘feeling sick’ when sitting the test (p. 334). Similarly, Howell (Citation2017) used drawings to elicit students’ constructions of NAPLAN in two Catholic schools with multiple children linking it to fears about their future employability.

Analysis of drawings: if assessment were a food?

Students were invited to draw and write a short annotation in response to the question: ‘If assessment was a food, what kind of food would it be?’ First, an inductive analysis initially focused on the dominant features in the drawing and phrases in the student’s annotation (Bland, Citation2012). The second deductive analytic phase involved trait coding (Haney et al., Citation2004, p. 253), where the researchers and leaders agreed on ratings from 1 (low) to 3 (high) on the extent to which theory informed traits were apparent using criteria. The traits included (1) emotions as indicators of concerns, addressing the school’s interest in student wellbeing; (2) a sense of control as an indicator of student agency; and (3) awareness of how assessment was informing learning, focusing on the school’s interest in promoting an assessment culture rather than a testing culture (see ). The two school leaders were then asked, ‘What patterns do you see in the drawings?’ and ‘What do you think might be done differently in your school as a result of what you see in the drawings?’ with the discussion audio recorded and transcribed.

Table 2. Coding of student drawing ‘If assessment was a food’: responses for students who were interviewed.

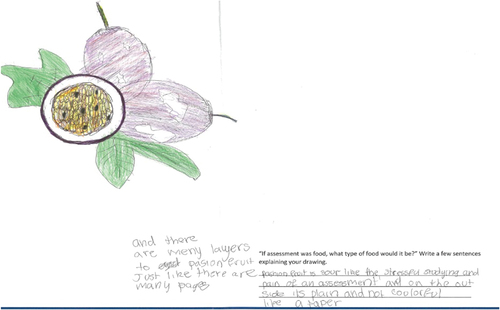

Figure 1. Passionfruit. The annotation reads ‘Passionfruit is sour like the stressful studying and pain of an assessment and on the outside it’s plain and not colourful like a paper and there are many layers to passionfruit just like there are many pages’.

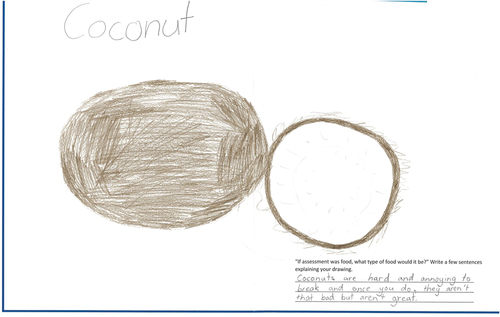

Figure 2. Coconut The annotation reads ‘Coconuts are hard and annoying to break and once you do they aren’t that bad but aren’t great’.

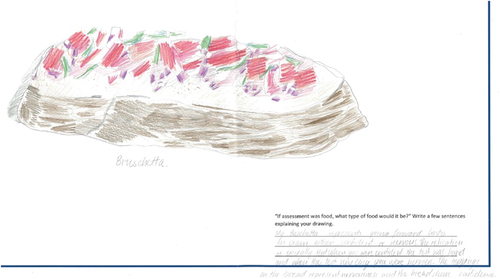

Figure 3. Bruschetta. The annotation reads ‘My bruschetta represents going forward into an exam either confident or nervous. The realisation is usually that when you were confident, the test was hard and when the test was easy, you were nervous. The topping on the bread represents nervousness and the bread shows confidence’.

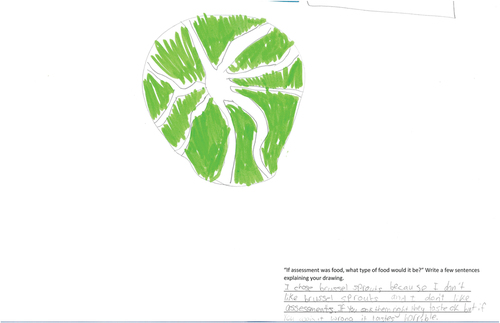

Figure 4. Brussels sprouts. The annotation reads, ‘I chose brussel sprouts because I don’t like brussel sprouts and don’t like assessments. If you cook them right they taste ok but if you cook it wrong it tastes horrible’.

Four of these students’ drawings are reproduced to illustrate a range of traits identified in the responses from students. These drawings represent a range of scores from a more traditional orientation to assessment with low emotion, low sense of control, separate from learning (), to higher scores indicative of an assessment culture () (Birenbaum, Citation2016; Gipps, Citation1994; Shepard, Citation2000).

The data was sorted to reflect the scoring patterns in the student emotions, sense of control and assessment literacies () and to identify how many students had similar combinations to gain a sense of the social construction of meaning, or culture.

Table 3. Summary of codes for drawings and annotations.

Analysis of interviews

Students from three of the classes whose pictures had been analysed were then invited to provide further comment in focus group discussions with the researchers. These three classes were nominated by the school to provide least disruption to the students who were undertaking summative assessment tasks at the time. Their drawings and annotations (see ) represent the wider range of perspectives. The students provided additional commentary and interpretations in the focus group interviews with prompts:

Can you tell us what your picture was, what it meant?

Would you still draw the same thing?

How does assessment help you learn?

The interview data was then theoretically coded using Archer’s (Citation2000) concepts of cultural (ideational) and structural (material) conditions to identify how they impacted student ideas around their agency (capacity for choices to enhance learning and wellbeing) with examples in .

Table 4. Sample coding from analysis of student focus group interviews.

Table 5. Thematic summary with barriers, enablers and student suggestions for assessment culture change.

The final phase of data collection was an interview with one school leader five years later to identify the changes that were prompted by the student commentary. While small in scale, the reflexive methodology had conceptual integrity (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022), bringing together the research goal of exploring possibilities for culture change in new assessment policy, as well as commitments to co-inquiry and co-construction of meanings among researchers, school leaders and students.

What can be learnt about assessment culture from students’ drawings and comments about assessment?

Students’ drawings offered insights into how existing assessment culture practices informed their learning (see ). Sixty-two percent of students did not see assessment as related to learning, an indicator of a traditional assessment culture, and 90% of students associated assessment with negative or mixed emotions, indicating a concern about assessment wellbeing. Annotations and focus group comments highlighted cultural and structural barriers that could be addressed, enablers for learning that they valued, and suggestions for change.

Cultural expectations of stress

A traditional testing culture with hallmarks of pressure and stress was structuring the learning of many students. Without the students’ annotations and commentary in the focus groups the drawings of food like coconuts, pineapple and kiwi fruit could indicate that assessment was a healthy experience. The annotations instead indicated that even if the end purpose was good for you, there was trepidation and ambivalence: ‘Assessments can be hard sometimes. They’re good for you, but sometimes you still don’t want to do them. That’s like pineapple: it’s good for you but sometimes you don’t want to eat it.’ Students spoke about assessment as a cause of stress: ‘I don’t really love assessment, because it puts a lot of pressure on you, and you get really stressed out and stuff.’ While several students commented that ‘it’s not as scary when you get in there’, the expectation of stress was a consistent theme.

In the focus groups, students who tried to minimise the association with stress did not question its reality. Comments from several students showed they deliberated about ways to push assessment stress further away from their daily lives: ‘I think a lot of people stress too much about the exam on the first week back. You don’t really need to stress until later on when you’re revising it.’ They wondered how they would manage additional stress that seemed inevitable, as learning became more complex: ‘What happens if we get into the older grades? It’s going to be even more packed’, and ‘Grade 7 we’re not that far into high school and we’re already very worked up about results’. A few students added critical commentary about the levels of stress that seemed to be accepted as natural with assessment. Each of their critiques focused on whether expectations were fair for young learners:

It’s not fair, because you only have one childhood, so you want to make the best of it, but at the same time if there’s too much school stuff to try and get done while also having the fun of being a kid; it just doesn’t work together.

I’m going to [this school which is] a good school and I can learn how to manage my time and I can learn how to be organised and be able to control what I do, and to be in control of my life obviously. I know that’s what is expected, but you can’t automatically do that in Grade 7. I feel like we should be edged into it, but it was pretty much first term full on.

Strong emotions are indicators of difficult deliberations for students highlighting opportunities for cultural change, especially when cultural ideas were being reproduced through structural systems, such as examinations.

Desire for structures that build confidence

A lot of student commentary was about examinations, which occurred at the end of each school term and structured the culture of assessment. Several students commented on not being confident that what they had learned would be sufficient for them to confidently complete the assessment task.

Sometimes I think I know what I’m doing, but then when I actually got my results back I’m like, oh, I didn’t know what I was doing, so how do I know to get help?

This confidence was achieved when there were clear connections between what was learned and what was assessed.

I feel like assessment it’s like not just the actual test, but it’s everything you’ve worked on the entire term, even if it’s not like your mark. So everything in your recipe is like - has to come together otherwise it just won’t work.

Students suggested that exams should be structured to have greater alignment between what had been taught and what was being assessed, and that assessment could bring the learning together:

The questions to be more similar to what we learned. Because sometimes I open an exam and I’m like, I didn’t learn this, and I just start freaking out.

Alignment between learning intentions and shared success criteria of assessment with students is a fundamental principle of an assessment culture that enables learning (L. Adie & Willis, Citation2016). Yet the sharing of success criteria is not a cultural practice that is commonly associated with exams – even low stakes teacher designed tests.

The school’s traditional practice was for teachers to give general advice beforehand, feedback about exam performances in a lesson after the exam, and then collect the papers: ‘ … they just go away. You never see them again … . I’d like to see them because I forget again.’ Students saw potential in making more use of exams to inform learning. One suggestion was that questions that caused difficulty could be used as a point of inquiry: ‘ … maybe like a big pie chart or something with this many people got this question wrong, and it’s quite a lot of people, so maybe we should go over it’. Personal review was also seen as potentially valuable: ‘ … if you don’t do well in the first term then you can use that to improve for the next exam and then you can really see a difference from each time, when you look back’.

Students had other suggestions for assessment structures that they found helpful to reduce stress and increase confidence. Clarity about connections between learning and assessment were valued, with one student associating a teacher’s clear structure with her own affinity with the discipline: ‘I really love science. I love how she always has everything perfectly planned out and all her notes are so neat, and you can see it all. I really like that.’ Many students expressed appreciation for checklists, revision plans, teachers making clear connections between learning episodes, and clearly scaffolded directions: ‘If you miss part of the lesson, you know that you can go back and check it and you’re not just running along a loose end.’ These materials needed to be easily accessible and used often. Students suggested that practice tests could be in rooms and under conditions similar to exams to reduce stress associated with new environments. They recognised that different disciplines have different assessment expectations and appreciated that assessment guidance would look different depending on the discipline. Overall, there was a sense of wanting to be clearly guided through a process and not be under continual time pressure.

Structural time pressures affect wellbeing

Students frequently made comments on how assessment timetables and timing impacted their wellbeing. For most students, the time pressure meant that they were not able to prepare well to represent their understanding. Prior to the interviews, students had experienced an assessment week: ‘ … it’s pretty much just, bang, bang, bang, bang’. Three students commented:

Let’s say you have science on Monday and then maths on Tuesday, you can have all of the weekend and before that to work on science and like, oh my goodness - I forgot I have maths tomorrow, and I need to have to do it that night. So, if there was, let’s say maybe three days at least before, in between each one?

So you’re not trying to also try and learn science and maths stuff at the exact same time and then get it confused.

There are normally about nine assessments in one week, so they have to double up on each day. So they give two assessments in one day … . It’s horrible.

Several students expressed a preference for assignments, indicating that the extended time frame gave them greater control over how they managed their time and led to more learning.

When you finish assignments it’s … not more hard work, but it’s been over a bigger time frame, so you have a chance to put more work into it.

I think I learn more from assignments because you have more time to search it up. In an exam, you have to know it – or you’ve studied and you know it. You just go through. You’re not learning any more as you’re going through the exam. But in the assignment, you’re learning it as you go, because you’re adding more and more.

A smaller number of student responses indicated that they preferred exams more than assignments as in, ‘I like it done really quick.’ The increasing variety in assessment types was recognised as a strength of the changing school assessment culture, with benefits like gaining different perspectives on themselves as learners and on the disciplines.

Students appreciated that the school was changing the culture away from an intense week of assessment: ‘ … this term we have them pretty spread out, but in previous terms they would have been all in the same week’. However, they felt that if they were unwell, they were still expected to complete the assessment task: ‘ … with exams, you need to do it that day – it doesn’t matter – unless you’re sick it doesn’t really matter how you’re feeling’. A few students also noted that the time pressure contributed to feelings of anxiety.

I always get really nervous before an exam, and I feel sometimes that reflects on my results. So, I much prefer having assignments because I get to spread out over a period of time so if I’m not feeling great on that day then I won’t do it.

Other concerns about wellbeing referred to the impact of time pressure on their family lives, their commitments to sport and their sleep with three students in one focus group elaborating:

I have a very sporty family and my brother will be out at soccer till nine and I have dance or swimming or netball – everything is going on. Some nights a week – like a Wednesday night and Thursday nights are really, really busy in my family. So, we don’t get home till 9.30pm, 10pm some nights anyway … . I have to do my homework and study, and that makes it really stressful especially if I’m studying for multiple tests.

Some nights I don’t get home till 11 o’clock at night. Then I’ll normally have my homework done, because sometimes I just do it in the car.

This might sound a bit silly, but it affects how late you stay up.

The student’s phrasing – ‘this might sound a bit silly’ – is an important emotional cue. In traditional assessment cultures there can be an assumption that sacrificing personal time and experiencing time pressure is a sign of effort and success. Students drew on these subtle cultural messages of identity in their assessment approaches, with their responses indicating their awareness that they needed ‘to put time in’ to assessment and work hard. Their responses also indicated that they struggled to reconcile competing messages within the time pressures associated with assessment structures and expected involvement in co-curricular activities.

How did student voice inform changes in school assessment culture?

The school leaders were open to hearing from students and were involved in initial data analysis of the student drawings to gain ideas. Parr and Hawe (Citation2020) challenge researchers and schools to

systematically [trace] the audit trail from the soliciting of voice or the opportunity for voice to be employed; through to the hearing, the reception and response; to the outcome of that response in terms of changed practice and also student awareness of their part in the changed practice; and, finally, student response to changed practice, the outcomes for learning.

The following audit trail explores the reception and response and some of the outcomes of changed practice. While the researchers had planned to gather responses from the same students to the changed school culture five years later in their senior year, that year was severely disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and research in schools was paused to reduce demands on students. Instead, to identify the assessment culture changes that did happen in areas that the students had identified, interviews with two leaders in 2016 and one leader in 2021 were thematically analysed for structural and cultural assessment changes.

In 2016 the school leaders recognised that cultural change in a school with a long and esteemed history would take time. They decided to let ideas and change ‘bubble up’ from collaborative inquiry, communicating a message to staff and students that the assessment culture change was ‘based on the philosophy of trust, so we trust you to do this … . We want it to be bottom-up and led that way. We’ve got to show sincerity with that and not keep on coming up with new things.’ Three interrelated agendas were identified: to maintain high performance; to shift the focus to formative assessment; and to reduce student anxiety associated with assessment (L. Adie et al., Citation2021). These agendas were especially the focus for the Year 7 students who were beginning their first year of high school.

Structural changes were made to assessment. The school conducted an audit before reducing the number of assessment tasks. A recurring two weeks of examination time every 10 weeks was abandoned in favour of more class time assessment and the teacher noticing evidence of learning through formative activities (Cowie et al., Citation2018). Time for more formative interactions was created by allocating each subject in Year 7 with the same amount of time per week where previously mathematics and English had more time allocated. Other structural and cultural changes included the removal of academic prizes in Year 7 to reinforce the focus on deep learning and wellbeing and remove pressures of competition. In the interview in 2021, the remaining leader reflected that the changes to timetabling and prize-giving felt like ‘crazy, brave’ decisions at the time, yet no complaints were received from parents or students. The leader attributed the acceptance to a clear communication of the intention to focus on wellbeing and stronger connections between assessment and learning. Grades were removed from Year 7 assessment, instead teachers focused on noticing evidence from formative assessment and giving feedback. A new reporting app was developed in 2017 where students and parents could access continuous reports on their progress, which replaced end of term testing and reporting in junior secondary. Additional structural changes included the school funding teacher professional learning about formative assessment and Cultures of Thinking (Ritchhart, Citation2015). Teacher annual performance processes were changed to a programme of peer observation supported by release time from classrooms. However, the school leader in 2021 also noted that continuous reporting has had an unwanted effect: ‘ … students have less time to recover in any areas of performance before parents become aware of any concerns with their child’s assessment performance’. Another concern the school leader noted was an intensification of work for teachers, as noticing evidence of student learning through discussions or capturing ideas within classroom activities takes additional time and energy.

Cultural changes were occurring simultaneously. In the six years since the start of the process of change, the remaining leader reported that by 2021 students and staff more readily used the language of assessment for learning, ‘noticing evidence of learning’ and ‘personal bests’ that was not evident previously. The curriculum included a new emphasis on self-assessment and self-regulation. While the school culture is still one of high performance, there has been some evidence of greater student wellbeing with fewer referrals for counselling support around assessment anxiety being documented, and wellbeing has been added as a reportable priority to the school’s strategic plan.

Before these cultural changes the school leader indicated the experience for students ‘was just teach-learn-assess’. Now the school professed to value a more deliberate approach to assessment culture and structures so that students were not overwhelmed by their first semester of high school. The leader indicated that more ‘time to breathe’ in the curriculum and assessment programme had been necessary to create a curriculum that focused more on learning and developing students’ agency and skills in self assessing. Since most of the school leadership had remained the same during this time, they were able to continually identify the vision, narrate the progress, induct new staff, listen to staff learning and collaborate on decisions about how to make progress. Additional evaluation within the school would be needed to fully represent the extent of cultural change and the concerns and tensions that are still to be resolved. However, in this reflective interview data, there was clear evidence of changed practice.

Discussion

Looking back, the students’ conclusions about assessment, wellbeing and time pressures were important catalytic data for the school leaders and teachers that confirmed their own concerns. As Archer (Citation2003) notes, material and cultural conditions are open to change through new types of social interactions, questioning and articulation of new ideas, yet agential powers are always conditioned by contexts. Students did not have the agency to make changes to the frequency of tests. Yet collectively students had achievable suggestions for ways to make assessment more manageable and additional insights, such as impacts on wellbeing. The frequency of assessment comments by students about fairness, time pressures and the emotions in annotations gave additional motivation to leaders to act.

Most student responses were about summative assessment and its influence on their sense of self at school and in family life. Students’ perceptions of assessment are not just contained within their experience of schools (Bourke & Loveridge, Citation2016). Their critique raises questions such as whether stress and anxiety about assessment is inevitable. This inquiry did not focus on how gender mediates learning, however anxiety and performance pressure are associated with gendered cultural norms of being ‘good’ and ‘hardworking’ female students. Norms that are shared at a girls’ only school may be so pervasive and invisible as a ‘form of life’ that they may not be easily shifted merely by changing some assessment structures (Elwood, Citation2006, p. 273). Cultural assessment beliefs persist over time as a form of sedimentation or layering (Elwood & Murphy, Citation2015; Finch & Willis, Citation2021; Wong et al., Citation2020). Other Australian drawing-based assessment research (Howell, Citation2017; Swain et al., Citation2018) also found evidence of assessment generating anxiety, indicating a cultural link beyond gendered schooling cultures.

Student comments about assessment anxiety did prompt assessment culture change. Archer (Citation2000) points out the valuable role that emotions play as a commentary on important concerns. Emotions provide ‘shoving power’ to take action (Archer, Citation2007, p. 13). Topics that are associated with hopes or worries point to areas of importance for cultural attention. For most students, assessment was separate from learning, a sign of traditional assessment cultures (Shepard et al., Citation2018). Such associations between assessment cultures and emotions were readily captured through the annotations in the drawings.

Making changes away from a testing culture at a time when the state policy was moving towards more testing was a risk for a school that was seen as highly successful. However, the school improved further on their high-performance outcomes in the Year 9 NAPLAN and the new senior examinations. The school leader attributed these outcomes to the changed assessment culture which has led to deeper learning and greater student agency in assessment, claims that are not explored in this research, but could be a future inquiry. Further inquiry into teacher workload is also needed to recognise the time involved in generating assessment cultures that equip students as agents and address important wellbeing concerns. The process outlined in this case study was possible in a school with resources to support a comprehensive focus on assessment culture change, but may be more challenging for other schools without the financial resources to support the teacher professional learning that accompanied such a change, or the material changes such as a new reporting app. The school leader also reported that some of these cultural changes are starting to be challenged by a delayed washback effect from the senior assessment changes, such as community expectations for students to do more practice tests in junior high school to prepare for senior examinations.

Being open to critical inquiry when new top-down assessment policies are introduced is challenging for schools as policies create material changes and new cultural norms. Yet assessment is always a process of inquiry, as there is never a perfect assessment system (Delandshere, Citation2002). Critical inquiry in assessment involves gathering multiple perspectives about the social and cultural acts of doing assessment in actual contexts, and considering conceptions, knowledge and beliefs of participants (Willis et al., Citation2019; Wyatt-Smith & Gunn, Citation2009). Cultural change is more likely to occur as people reflexively inquire – Archer’s (Citation2000) concept of morphogenesis. Planning for change in an assessment culture needs to involve teachers and students in discerning and deliberating through critical inquiry. However, listening to student voices can be challenging for educators as it is not a practice that teachers or leaders typically experienced in their own schooling (Tay et al., Citation2020). When students are critical, it may not match the teachers’ conceptions or ideals, leading teachers to reinterpret student perspectives in light of their own main concerns (Bourke & Loveridge, Citation2016; Cook-Sather, Citation2006.). Teachers in a high-performance school culture may feel tension when there are equally pressing cultural expectations to help students achieve good assessment results (L. Adie et al., Citation2021; Wong et al., Citation2020). Research into the conditions for co-inquiry into assessment culture change was not a focus of this paper, but as Bourke and Loveridge (Citation2018) highlight, is an important step in moving beyond tokenistic inclusions of student voice in schools.

Artworks with annotations and focus group interviews are demonstrated in this case study to be a productive process to invite student voice. The use of metaphor to prompt the drawings enabled a range of student representations, with annotations providing insights into abstract concepts, such as wellbeing and agency. The visual methodologies were quick to generate in a class activity, yet they were time-consuming to analyse, and schools considering this methodology would need to plan sufficient time for collaborative analysis conversations. In analysing random samples of the drawings, dominant themes could be identified swiftly in a structured and collaborative way which suited the pragmatic focus of this inquiry (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). One limitation is that important student views only expressed by one or two students may have been overlooked. A further limitation of drawing-based research is that adults can potentially interpret students’ voices in ways that serve their own aims or not recognise the situated contexts (Teachman & Gladstone, Citation2020). This limitation was addressed by the collaborative inquiry approach between school leaders, teachers and researchers as critical colleagues, and analysing the data through a theoretical lens. Future iterations could engage students in direct analysis of the data, and teacher discussions about what might be done in response.

Conclusion

This study is a small-scale case study that outlines a theoretically informed and practical process of collaborative analysis that could enable leaders and teachers to work with students to generate new ideas. Assessment culture change occurred as the assessment material structures began to change. New professional learning, timetabling and reporting structures led to new cultural expectations about the role of assessment to inform learning progress, and students drawing on the language and skills for self-reflection. The disruption to the structural changes in the senior secondary state-wide assessment enabled new assessment cultural possibilities, yet the pressure of wider cultural forces may make these changes hard to sustain within one school culture. Assessment culture is not stable and always a work in progress. Assessment change can be driven by structural changes initiated by school leaders and teachers, but, we would argue, also by students as agents reflexively weighing up their concerns or ongoing courses of action.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Archer describes cultural and structural properties as emergent as they are not inherently enabling or constraining, as this depends on how the individuals engage with the properties.

References

- Adie, L., Addison, B., & Lingard, B. (2021). Assessment and learning: An in-depth analysis of change in one school’s assessment culture. Oxford Review of Education, 47(3), 404–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1850436

- Adie, L., & Willis, J. (2016). Making meaning of assessment policy in Australia through teacher assessment conversations. In L. Allal & D. Laveault (Eds.), Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation (pp. 35–53). Springer.

- Adie, L. E., Willis, J., & Van der Kleij, F. M. (2018). Diverse perspectives on student agency in classroom assessment. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0262-2

- Alerby, E. (2015). A picture tells more than a thousand words. In J. Brown & N. F. Johnson (Eds.), Children’s images of identity. transgressions: Cultural studies and education (p. 107). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-124-3_2

- Allal, L. (2016). The co-regulation of student learning in an assessment for learning culture. In L. Allal & D. Laveault (Eds.), Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation (pp. 259–273). Springer.

- Archer, M. S. (1996). Culture and agency: The place of culture in social theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. (2000). Being human: The problem of agency. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511488733

- Archer, M. S. (2003). Structure, agency and the internal conversation. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139087315

- Archer, M. S. (2007). Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility. Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. (2012). The reflexive imperative in late modernity. Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S., & Morgan, J. (2020). Contributions to realist social theory: An interview with Margaret S. Archer. Journal of Critical Realism, 19(2), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2020.1732760

- Barrance, R., & Elwood, J. (2018). National assessment policy reform 14–16 and its consequences for young people: Student views and experiences of GCSE reform in Northern Ireland and Wales. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 25(3), 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2017.1410465

- Birenbaum, M. (2016). Assessment culture versus testing culture: The impact on assessment for learning. In L. Allal & D. Laveault (Eds.), Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation (pp. 275–292). Springer.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment.

- Bland, D. (2012). Analysing children’s drawings: Applied imagination. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 35(3), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2012.717432

- Bourke, R., & Loveridge, J. (2016). Beyond the official language of learning: Teachers engaging with student voice research. Teaching and Teacher Education, 57, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.008

- Bourke, R., & Loveridge, J. (2018). Using student voice to challenge understandings of educational research, policy and practice. In Radical collegiality through student voice (pp. 1–16). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1858-0_1

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis?. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Burcaş, S., & Creţu, R. Z. (2021). Multidimensional perfectionism and test anxiety: A meta-analytic review of two decades of research. Educational Psychology Review, 33(1), 249–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09531-3

- Carless, D., & Lam, R. (2014). The examined life: Perspectives of lower primary school students in Hong Kong. Education 3-13, 42(3), 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2012.689988

- Charteris, J., & Thomas, E. (2017). Uncovering ‘unwelcome truths’ through student voice: Teacher inquiry into agency and student assessment literacy. Teaching Education, 28(2), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1229291

- Consuelo, M., Grazia, V., & Molinari, L. (2020). Agency, responsibility and equity in teacher versus student-centred school activities: A comparison between teachers’ and learners’ perceptions. Journal of Educational Change, 21(2), 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-019-09366-y

- Cook-Sather, A. (2006). Sound, presence, and power:“Student voice” in educational research and reform. Curriculum Inquiry, 36(4), 359–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2006.00363.x

- Cook-Sather, A. (2018). Tracing the evolution of student voice in educational research. In Radical collegiality through student voice (pp. 17–38). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1858-0_2

- Cowie, B., Harrison, C., & Willis, J. (2018). Supporting teacher responsiveness in assessment for learning through disciplined noticing. The Curriculum Journal, 29(4), 464–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2018.1481442

- Delandshere, G. (2002). Assessment as inquiry. Teachers College Record, 104(7), 1461–1484.

- Elwood, J. (2006). Gender issues in testing and assessment. The Sage Handbook of Gender and Education, 262–278. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607996.n20

- Elwood, J., Hopfenbeck, T., & Baird, J. A. (2017). Predictability in high-stakes examinations: Students’ perspectives on a perennial assessment dilemma. Research Papers in Education, 32(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2015.1086015

- Elwood, J., & Murphy, P. (2015). Assessment systems as cultural scripts: A sociocultural theoretical lens on assessment practice and products. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(2), 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2015.1021568

- Finch, M., & Willis, J. (2021). Learning to be expert writers: Feedback in secondary English. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 28(2), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2021.1908226

- Gillett-Swan, J. K. (2018). Children’s analysis processes when analysing qualitative research data: A missing piece to the qualitative research puzzle. Qualitative Research, 18(3), 290–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117718607

- Gipps, C. (1994). Developments in educational assessment: What makes a good test? Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 1(3), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594940010304

- Groundwater-Smith, S., & Mockler, N. (2016). From data source to co-researchers? Tracing the shift from ‘student voice’ to student–teacher partnerships in educational action research. Educational Action Research, 24(2), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1053507

- Haney, W., Russell, M., & Bebell, D. (2004). Drawing on education: Using drawings to document schooling and support change. Harvard Educational Review, 74(3), 241–272. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.74.3.w0817u84w7452011

- Harris, L. R., Brown, G. T., & Dargusch, J. (2018). Not playing the game: Student assessment resistance as a form of agency. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0264-0

- Harris, L. R., Brown, G. T. L., & Harnett, J. A. (2014). Understanding classroom feedback practices: A study of New Zealand student experiences, perceptions, and emotional responses. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 26(2), 107–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-013-9187-5

- Harris, L. R., Harnett, J. A., & Brown, G. T. L. (2009). Drawing” out” out student conceptions: Using pupils’ pictures to examine their conceptions of assessment. In D. M. McInerney, G. T. L. Brown, & G. A. D. Liem (Eds.), Student perspectives on assessment: What students can tell us about assessment for learning (pp. 53–83). Information Age Publishing.

- Howell, A. (2017). ‘Because then you could never ever get a job!’: Children’s constructions of NAPLAN as high-stakes. Journal of Education Policy, 32(5), 564–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1305451

- Klenowski, V., & Wyatt-Smith, C. (2012). The impact of high stakes testing: The Australian story. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 19(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2011.592972

- Martin, J. (2016). The grammar of agency: Studying possibilities for student agency in science classroom discourse. Learning, Culture & Social Interaction, 10, 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2016.01.003

- Mayes, E., Finneran, R., & Black, R. (2019). The challenges of student voice in primary schools: Students ‘having a voice’ and ‘speaking for’ others. Australian Journal of Education, 63(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944119859445

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (n.d.). Student agency for 2030. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/student-agency/

- Parr, H., & Hawe, E. (2020): Student pedagogic voice in the literacy classroom: A review. Research Papers in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1864769

- Pryor, J., & Crossouard, B. (2008). A socio-cultural theorisation of formative assessment. Oxford Review of Education, 34(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980701476386

- Putwain, D., & Daly, A. (2014). Test anxiety prevalence and gender differences in a sample of English secondary school students. Educational Studies, 40(5), 554–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2014.953914

- Ritchhart, R. (2015). Creating cultures of thinking: The 8 forces we must master to truly transform our schools. John Wiley & Sons.

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X029007004

- Shepard, L. A., Penuel, W. R., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2018). Using learning and motivation theories to coherently link formative assessment, grading practices, and large‐scale assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues & Practice, 37(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12189

- Spina, N. (2019). ‘Once upon a time’: Examining ability grouping and differentiation practices in cultures of evidence-based decision-making. Cambridge Journal of Education, 49(3), 329–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2018.1533525

- Stobart, G. (2008). Testing times: The uses and abuses of assessment. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203930502

- Swain, K., Pendergast, D., & Cumming, J. (2018). Student experiences of NAPLAN: Sharing insights from two school sites. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(3), 315–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0256-5

- Tay, K., Tan, K., Deneen, C., Leong, W., Fulmer, G., & Brown, G. (2020). Middle leaders’ perceptions and actions on assessment: The technical, tactical and ethical. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1582016

- Teachman, G., & Gladstone, B. (2020). Guest editors’ introduction: Special issue: Constructions of “Children’s voices” in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940692098065. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920980654

- Willis, J., McGraw, K., & Graham, L. (2019). Conditions that mediate teacher agency during assessment reform. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 18(2), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-11-2018-0108

- Wong, H. M., Kwek, D., & Tan, K. (2020). Changing assessments and the examination culture in Singapore: A review and analysis of Singapore’s assessment policies. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 40(4), 433–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2020.1838886

- Woods, K., McCaldin, T., Hipkiss, A., Tyrrell, B., & Dawes, M. (2019). Linking rights, needs, and fairness in high-stakes assessments and examinations. Oxford Review of Education, 45(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2018.1494555

- Wyatt-Smith, C., & Gunn, S. (2009). Towards theorising assessment as critical inquiry. In C. Wyatt-Smith & J. J. Cumming (Eds.), Educational Assessment in the 21st Century (pp. 83–102). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9964-9_5