ABSTRACT

Completing a higher education degree is a game changer for the success of Indigenous youth. However, there is a paucity of research which explores the enablers of and barriers to Indigenous higher education youth (18–25 years) wellbeing. This systematic literature review aimed to explore the nature and scope of international research that engages with Indigenous youth to identify the enablers of and barriers to youth’s wellbeing when undertaking higher education. Twenty-eight studies met our selection criteria. Major enablers of youth’s wellbeing included social connections and support. Barriers included: lack of culturally appropriate support, home sickness, financial stress and negotiating with family. These findings have highlighted a significant gap in research and practice and point to the importance of hearing Indigenous higher education youth’s voices for identifying salient strategies for respectful promotion of wellbeing in higher education.

Introduction

‘A university education can be a powerful game changer for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, families, communities and the nation’ (Universities Australia [UA], Citation2022). These ‘powerful game changers’ are valuable and have the potential to improve employment, economic, social and cultural participation and health and wellbeing outcomes (Arriangada, Citation2021; Durmush et al., Citation2021; Hutchings et al., Citation2018; Theodore et al., Citation2017; UA, Citation2022). However, considerable inequalities in educational attainment exist, internationally, for Indigenous peoples in higher education. Hence, the United Nations (UN) has set as a primary goal by 2030 to ensure quality tertiary education for Indigenous peoples (UN, Citation2022). Despite the long-term benefits of higher education, studying can be a challenging period for all students regardless of their background (Bewick et al., Citation2010; Dodd et al., Citation2021; Prowse et al., Citation2021).

For Indigenous students globally, higher education study can present additional challenges to their wellbeing on top of pre-existing wellbeing issues associated with the ongoing effects of colonisation (Dudgeon et al., Citation2020; Hop Wo et al., Citation2019). Identified challenges to Indigenous higher education include: racism and lack of cultural safety (Bailey, Citation2020; Behrendt et al., Citation2012; Bin-Sallik, Citation2003; Canel-Çınarbaş & Yohani, Citation2019; Rochecouste et al., Citation2014), lateral violence (Bailey, Citation2020; Durmush et al., Citation2021), financial difficulties and lack of financial support (Hearn & Kenna, Citation2020), lack of social support (Durmush et al., Citation2021; Hearn & Kenna, Citation2020), family responsibilities (Hearn & Kenna, Citation2020; Smith, Citation2012) and lack of Indigenous knowledge embedded in the curriculum and across university policies, deliverables and governance (Milne et al., Citation2016; Pidgeon, Citation2008).

Enablers to Indigenous higher education student success include: family and community support (Durmush et al., Citation2021), cultural safety (Rochecouste et al., Citation2014), inclusion of Indigenous knowledges taught in the curriculum and embedded in policy and university governance (Durmush et al., Citation2023), establishing Indigenous higher education units (Benton et al., Citation2021; Trudgett, Citation2009), offering Indigenous academic support programs (Lydster & Murray, Citation2019) and student financial support (Walton et al., Citation2020). However, this literature has largely examined Indigenous students’ educational experiences which is unfortunate as little is known about how to best support Indigenous higher education students’ wellbeing.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a detrimental impact on students’ mental health and wellbeing with the disruption of teaching and learning. For example, changes to higher education class structures moving from in-person classes to online has led many students to feel anxious and lonely resulting from a lack of social connection and support from peers and academic staff members (Akuhata-Huntington, Citation2020; Dodd et al., Citation2021). COVID-19 has also impacted the wellbeing of students particularly Indigenous students and their families through job losses leading to acute financial insecurity and emotional and mental pressures for families living in overcrowded housing (Akuhata-Huntington, Citation2020). Akuhata-Huntington's (Citation2020) report highlights the impacts of COVID-19 on Māori Indigenous university students’ wellbeing. The majority of Māori respondents in the study reported feeling more sad (52.2%) and more anxious (75.7%) during the COVID lockdowns in New Zealand.

These results suggest that COVID-19 has resulted in maladaptive impacts on Indigenous higher education students’ wellbeing. Given the importance of Indigenous student wellbeing and its impacts on Indigenous students’ higher education experience and outcomes such as retention and completion rates (Durmush et al., Citation2021), there is surprisingly a scarcity of evidence-based research which has investigated the enablers of and barriers to Indigenous higher education youth (aged between 18–25) wellbeing across the globe. This systematic literature review aims to address this knowledge gap. Further, many Indigenous peoples globally have an increasing younger age profile. For example, in Australia and New Zealand youth represent over 50% of the Indigenous populations (Akuhata-Huntington, Citation2020). In Canada, First Nations, Métis and Inuit youth make up 16.9% of the Indigenous population compared to the non-Indigenous youth population (12%) (Statistics Canada, Citation2021). As such, Indigenous higher education youth are increasingly an important group to target as they are the future leaders of Indigenous nations, which makes their wellbeing critical to support.

Current understandings of Indigenous wellbeing

Indigenous conceptualisations of wellbeing are holistic and acknowledge that wellbeing is shaped by many determinants, including culture (Dudgeon et al., Citation2017). However, each Indigenous culture and country may use different terminology to describe health and wellbeing (Sutherland & Adams, Citation2019). For example, in Australia, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Citation2018) defines Australian First Nations wellbeing as a holistic concept that is ‘more than just the absence of disease or illness; it is a holistic concept that includes physical, social, emotional, cultural, spiritual and ecological wellbeing for both the individual and the community’ (p. 2).

In New Zealand, Máori’s health and wellbeing is defined through Durie’s (Citation1984) Te Whare Tapa Whā model. The model identified that Máori’s health and wellbeing consists of four important dimensions, also referred to as Hauora, which are key to enhancing and balancing Māori health and wellbeing: 1) Taha tinana (the physical health of one’s body); 2) Taha wairua (spiritual health including one’s understanding of self, self-worth, confidence and values, culture and beliefs); 3) Taha whānau (family health and relationships); and 4) Taha hinengaro (mental and emotional health; Barnes & McCreanor, Citation2019). Durie illustrated the Te Whare Tapa Whā model as a whare (meeting house) with four walls representing the key factors which impact a Māori person’s wellbeing. Notably, Māori hauora is holistic, with all dimensions of wellbeing being seen as interconnected.

In Canada, First Nations people view health and wellbeing according to the medicine wheel (Sutherland & Adams, Citation2019). The medicine wheel shows how First Nations Canadian people view the world holistically and view that every person, flora and fauna is interconnected with the environment and each other, thus having a major influence on a person’s overall health and wellbeing. Similarly, Native Hawaiian peoples’ understandings of health and wellbeing stem from cultural values and places importance on interrelationships.

For instance, The Native Hawaiian concept of self is grounded in social relationships (Handy & Pukui, Citation1972) and tied to the view that the individual, society, and nature are inseparable and key to psychological health (McCubbin & Marsella, Citation2009). Health is understood through the concept of the lokahi triangle, which means peace and harmony. The lokahi triangle is made up of three interconnecting parts: spirituality, land and humans. Therefore, native Hawaiian peoples view wellbeing as holistic and recognise that family, land and the spiritual world all need to be in balance.

In Australia, the Dudgeon et al. (Citation2017) model of Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEW) conceptualises Australian Indigenous social and emotional wellbeing as a multifaceted and holistic concept that is shaped by seven inter-connected connections to: 1) Country; 2) culture; 3) community; 4) family and kinship; 5) mind and emotions; 6) body; and 7) spirit, spirituality and ancestors. Notably, the model defines Indigenous wellbeing as a collective concept whereby self is underpinned by family and community. The model recognises the impacts of social, political and historical determinants on the wellbeing outcomes of Indigenous Australians and hence is important in providing an overview of the determinants which drive and hinder Indigenous Australians’ wellbeing, a critical aim of this research. However, this model, whilst useful, has limitations in relation to the current research given it only provides an Indigenous Australian wellbeing perspective, which does not reflect nor represent the diverse wellbeing and cultural perspectives of Indigenous youth internationally.

However, despite this limitation, the model represents similar wellbeing values that Indigenous cultures share in common and in particular wellbeing barriers that globally many Indigenous people have experienced due to colonisation. These include: connection to culture, Country, family and community, spirituality, historical, political and social determinants and self-determination (Butler et al., Citation2019; Gall et al., Citation2021). A greater focus on the wellbeing needs of Indigenous Australian students to inform educational strategies seems crucial considering Indigenous university student outcomes remain at a low rate (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2019).

The present investigation

Aims

The aims of this systematic literature review were to: 1) explore the nature and scope of qualitative research which focuses on Indigenous higher education youth wellbeing; 2) identify and qualitatively synthesise the enablers of Indigenous higher education youth wellbeing; and 3) establish and qualitatively synthesise the barriers to Indigenous higher education youth wellbeing.

Research Questions

Our investigation aimed to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1.

What is the nature and scope of research focusing on Indigenous youth attending higher education institutions to explore Indigenous wellbeing?; and

RQ2.

What has research on Indigenous youth attending higher education institutions identified as the enablers of and barriers to wellbeing?

Methodology

Reporting in this review aligns with the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ statement; Tong et al., Citation2012). Notably, our review structure reports the 21 items from the ENTREQ guidelines to ensure the qualitative synthesis is transparent.

Procedures

For our review we adopted the protocol recommended by the Campbell Collaboration for conducting systematic literature reviews (Kugley et al., Citation2015; Wiley et al., Citation2020). We searched and screened articles according to guidelines by the Campbell Collaboration and guidance by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) on identifying a broader range of studies based upon detailed selection criteria (see Search strategy). This search strategy included naming specific Indigenous names in search terms in addition to more generic terms such as Aboriginal, First Nations and Indigenous (see Search strategy). We began with a Google Scholar forward search to define search terms and searched broad databases (e.g. ERIC, EBSCOhost, Informit Complete, ProQuest, Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection). We hand-searched specialist journals, experts’ publications and interrogated references in these sources to identify further relevant research for analysis.

Search strategy

(aborigin* OR koor* OR murri OR yolngu OR ‘Akimel O’odham’ OR ‘Alaska Native*’ OR ‘American Indian*’ OR anishinaabe OR apache OR athabascan OR blackfoot OR cherokee OR cree OR dakota OR dene OR eskimo OR ‘First People*’ OR ‘First Nation*’ OR haida OR hopi OR indigen* OR innu OR inuit OR inupiat OR kalaallit OR lapp OR lumbee OR maori OR metis OR mohawk OR native* OR ‘Native Hawaiian*’ OR ‘Native People*’ OR navajo OR ‘non-Indigen*’ OR ojibway OR ‘Pacific People*’ OR polynesian OR pueblo OR sami OR samoan OR saulteaux OR ‘Tohono O’odham’ OR ‘Torres Strait*’ OR yupik) AND (‘youth’ OR ‘young people’ OR student* OR pre-graduate*) AND (experience* OR voic* OR agency OR succe* or thriv* OR engag* OR achiev* OR barrier* OR worldview* OR perspectiv* OR enabler* OR driver* OR facilitator*) AND (wellbeing OR well-being OR ‘well being’ OR affect) AND (universit* OR ‘higher educ*’ OR tertiary OR college OR ‘student centre’ OR ‘student centre’)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Types of studies. Our review was limited to qualitative studies between 2000–2020 that included direct quotes from Indigenous participants to reflect their individual voices and experiences. Quantitative research or qualitative studies that did not provide direct quotes from Indigenous students were excluded.

Types of participants. The participants were required to have Indigenous heritage, being aged between 18 and 25 years. We operationally defined youth as those aged up to 25 as there is increasing recognition that youth also comprise the ages of 26–30 (Commonwealth Youth Awards, Citation2020; Indigenous Allied Health Australia, Citation2020; National Youth Council Singapore, Citation2020). Participants also needed to be currently attending or recently having graduated or left a higher education institution. Indigenous participants included all Indigenous participants globally reported in extant research.

Types of interventions. No specific intervention was required to be conducted in order for a study to be included in our review.

Types of outcome measures. Outcomes associated with higher education success and barriers, in addition to wellbeing, were required to have been measured in order for the study to be included in our review (see Search strategy).

Types of settings. The studies were required to take place within a higher education setting. This could include university, college and associated Indigenous centres and support offices.

Searching other resources

Two methods were conducted to search for relevant literature in addition to the electronic searches – forward referencing and backwards referencing. Forward referencing involves locating literature of interest via online databases (Hinde & Spackman, Citation2015). Backwards referencing was adopted to identify important literature, by first selecting an article of interest and then reading the reference list to identify further research papers relating to Indigenous higher education students and wellbeing (Hinde & Spackman, Citation2015). Further, authors of identified articles in the initial search advised of further potential studies. All studies identified were imported into Covidence, a web-based software which enables researchers to find appropriate research through the process of abstract and full text review screening (Babineau, Citation2014). All studies were abstract screened by four coders. Conflicts were resolved as they evolved by the lead researcher or when the lead researcher was involved by the second author. Full text screening was conducted by three coders and all conflicts were evaluated by the three coders. The final search articles were imported into Covidence (systematic review screening software) for further sorting of duplicates and initial and final screening of results. We conducted critical appraisal and systematically coded all systematically identified studies so coding was consistent across all studies (see Data analysis section below).

Qualitative appraisal findings

To examine the quality of extant research focusing on the voice of Indigenous higher education students regarding their wellbeing, we firstly summarised the results of the CASP. Three independent coders coded the 28 included studies each according to the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative studies checklist (CASP, 2020). CASP is an appraisal tool that supports qualitative researchers who are conducting research such as systematic literature reviews. The CASP qualitative studies checklist is designed to assess the quality of a research paper’s research design, practice and conduct (CASP, 2020). The inter-rater reliability score between the three coders assessing each paper’s CASP quality was r = 0.71. According to McHugh (Citation2012), scores between 0.61–0.80 levels of agreement are substantial. CASP is an appraisal tool that supports qualitative researchers who are conducting research such as systematic literature reviews.

The CASP qualitative studies checklist is designed to assess the quality of a research paper’s research design, practice and conduct (CASP, 2020). The CASP qualitative checklist questions included the following: (1) Was there a clear statement of the Aims?; (2) Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?; (3) Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?; (4) Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?; (5) Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?; (6) Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?; (7) Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?; (8) Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?; (9) Is there a clear statement of findings?; (10) How valuable is the research?.

The CASP findings from the 28 students were as follows: All 28 included studies showed a clear statement of aims; used qualitative methodology; 26 (89%) studies justified and discussed their research design and use of methods; 24 (85%) studies explained the recruitment strategy process; 24 (85%) studies explained and justified how methods and data was collected. A total of 21 (75%) studies highlighted the relationship between the researchers and participants; 26 (89%) studies outlined ethical considerations; and 24 (85%) studies presented details of the data analysis process.

All 28 included studies presented a clear statement of findings; and all 28 included studies demonstrated their research was valuable and important to Indigenous people. As our research is focused on leveraging Indigenous higher education youth voices, we assessed each study based on how many direct student quotes were included as either limited or high volume. Studies which had no student quotes were excluded.

Critical appraisal demonstrated that the quality of the research was limited in a number of areas. A total of seven of 28 studies did not identify the relationship between the researchers and participants. However, in Indigenous research, it is crucial that researchers develop a trustful and culturally safe research participant relationship (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010). Social, cultural and psychological determinants of wellbeing were most frequently mentioned. Concerningly, higher education wellbeing studies either referring to or focused on Indigenous students’ academic or physical wellbeing were rare. This is unfortunate as academic wellbeing is likely to be critical to retention and completion of higher education and physical wellbeing is fundamental to being able to pursue higher education.

Data analysis

Three coders conducted thematic analysis by discussing each included study’s direct student quotes to identify the underlying theme being articulated. The process of thematic analysis followed five phases (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006): 1) Researchers familiarising themselves with student quotes from the 28 studies; 2) Generating initial codes and labels of the themes; 3) Searching for the themes in the quotes; 4) Adding and finalising theme names; and 5) Writing and producing the journal paper. Hence, thematic analysis was the most appropriate and robust qualitative analysis method in ‘identifying, analysing, organising, describing and reporting themes found within a data set’ (Nowell et al., Citation2017).

Results

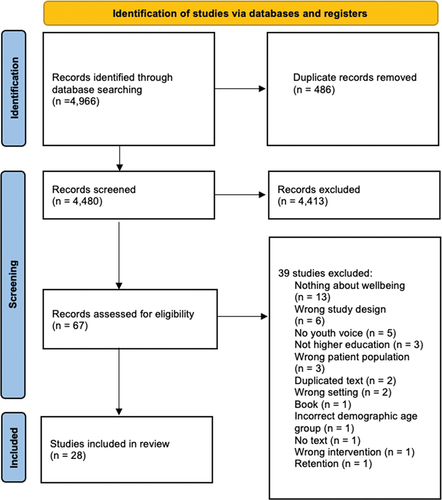

Our preliminary search identified 4,966 studies. A total of 486 duplicates were removed leaving 4,966 records for screening. A total of 4,413 studies were excluded based on selection and exclusion criteria, resulting in 67 eligible records for full text review. A further 39 studies of the 67 were excluded based on selection criteria. As a result, from our findings, a total of 28 studies with samples from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Pacific Islands and Mexico were identified for coding (see and ).

Table 1. Summary of Studies Included.

RQ2.

The Enablers and Barriers of Indigenous Youth Wellbeing in Higher Education

The following themes were identified as the most important enablers and barriers to Indigenous youth’s wellbeing in higher education. All themes are intertwined and interconnected. It is important to note that all themes can be both enablers and barriers to Indigenous youth’s wellbeing and remain subjective.

Enablers

Indigenous support units and centres

Students advocated that, having a set place and space like an Indigenous centre where Indigenous students and staff can meet, is fundamental to wellbeing and developing a sense of belonging. ‘Tjabal provides that place for interaction, for community development and through having events, we celebrate together, we mourn together. Not feeling alone on our journeys is so helpful’ (Powell, Citation2017, p. 38). Another First Nations student from Australia shares the importance of centres providing access to peer support: ‘The biggest one is that sense of community and we are like a melting pot of Indigenous peoples from around the country. I think the peer support is really beneficial and if you didn’t have Tjabal there wouldn’t be that meeting place for them’ (Powell, Citation2017, p. 62). A Māori student also explains, ‘It did help to see another Māori face in the room … you kind of feel like, “Oh, I’m not just biting off more than what I can chew here”’ (Chittick et al., Citation2019, p. 18).

A student also reflected on the importance of Elders and community members being present within the higher education space.

There were no Elders or community around when I first started in Education and it was a really wobbly journey for me. But things changed and all of a sudden we had an Elder in residence and wise old people walking around helping to guide us. Some days I went up to uni just to talk to them about how to cope with walking in two worlds, how to manage feeling black but learning white (Trimmer et al., Citation2018, p. 64).

Hence students advocated having Elders and community members as role models and leaders in higher education spaces as powerful and an important cultural support for guiding Indigenous students throughout higher education.

Connection to peer support

In much of the included studies youth identified the role of their peer community in supporting and motivating them to continue and complete their studies. In particular, Indigenous youth expressed that having peer support positively affected their wellbeing whilst no community support affected their mental health, overall wellbeing and commitment to their studies. For example, ‘Having a supportive community definitely affects my wellbeing. If I don’t have the support of people around me then I think it would be very difficult to be able to focus on my studies and be healthy mentally’ (Powell, Citation2017, p. 37). A First Nations student from Australia emphasised, ‘I developed my own little network of about three or four of us who were all studying about the same time and supporting each other. They weren’t necessarily in the same field as me. It was just a way of having a bit of a rant about how hard research is or [laughs] “Oh, my supervisor wants this” [laughs], that sort of thing’ (Barney, Citation2018, p. 18). These comments suggest that peer support during higher education courses enables wellbeing via moral support, rapport, and humour. Hence, connection to community is identified by youth as an enabler to their wellbeing.

Resilience

Youth in the studies we reviewed addressed what kept them motivated to continue their tertiary studies. For instance, for one student it was maintaining stress levels, ‘I just go about my own business, keep my stress down, come to uni every day and if I can, maintain my stress level’ (Toombs, Citation2011, p. 3). Whilst for other Indigenous students it was proving people wrong, such as teachers who questioned their ability to complete their studies, that motivated them to keep studying. For example, ‘It was teachers telling me I couldn’t [make it] which made me just push harder’ (Mayeda et al., Citation2014, p. 175). For others it was proving the negative racist stereotypes wrong and being a successful positive role model for the next generation of Indigenous people that motivated studying:

I think that for me success is overcoming that like, ‘you’re Indigenous, you don’t go to uni’, sort of stereotype … so I think for me it’s just like telling other kids and my cousins and everyone at home that they can do it too. That for me is success. (Lydster & Murray, Citation2019, p. 113)

The under-representation and visibility of Indigenous people studying higher education provided some Indigenous students with the resilience and drive to continue studying: ‘From a Māori perspective, because of all the negativity and the lack of brown faces. Absolutely – that was my number one drive … was that it can be done’ (Chittick et al., Citation2019, p. 17). Hence, resilience is a critical enabler to Indigenous higher education youth’s wellbeing, enabling students to overcome the challenges studying brings.

Barriers

Lack of cultural safety

Some students reported that the higher education environment was not culturally appropriate. Western styles of teaching are often based on requiring students to learn individually, which can be a barrier for some Indigenous students who learn better collectively as Indigenous culture and teachings and ways of knowing, being, and doing depend on collectivity, rather than individual means. As voiced by a First Nations student from Australia:

A lot of Indigenous people are comfortable talking in small groups, and not large groups. In some lectures you may have up to 150 students in the one room and that’s a scary factor when you don’t have enough confidence in yourself to publicly speak or to publicly ask questions. So therefore a lot of students will internally close themselves in and say I don’t understand and walk away from it. (Kippen et al., Citation2006, p. 7)

A Māori student advocated that: ‘I think the university should push for that kind of collective learning rather than individual learning. Because I think that’s how we flourish, and I think that’s how our ancestors have worked, and the way our culture is structured’ (Mayeda et al., Citation2014, p. 174).

The different Western teaching styles and under-representation of Indigenous academics and perspectives presented in the curriculum were also identified by students to continuously be an issue, leading many students to navigate two worlds (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) and sacrificing their cultural identity. For example, a Māori student describes: ‘University is very much a Pākehā institution. … Māori students feel like they leave their identity, leave their culture, at the door’ (Amundsen, Citation2019, p. 418).

Indigenous students reported being embarrassed about being treated as ‘black experts’. 'The lecturer said this week we’re focusing on Indigenous women, I kind of almost cringe at the time, because everyone looks at me and thinks I know everything about it' (Barney, Citation2016, p. 6).

Some students emphasised that the higher education environment was racist, noting that:

I was subjected to sitting through one class where the lecturer advocated for the 2007 [Northern Territory] Intervention by stating most Indigenous men were drunks, was shown images of deceased Indigenous people in a video about the Stolen Generation in class without warning (and was told I lost class participation marks when I went outside because I was upset), and was questioned by a class why my grandfather didn’t just sue the government for being part of the Stolen Generation. (Schwartz, Citation2018, p. 12)

Others reported that lecturers questioned their identity:

Well, I had one lecturer, and in a group of other white people said, ‘Oh, you’re the Indigenous student, aren’t you’, and I said, ‘Yeah’, and he said, ‘Oh, how are you, Koori. You don’t look … ’. I sort of just shrank. He was probably thinking he was being really open and oh, no, it was so embarrassing. (Kippen et al., Citation2006, p. 6)

Similarly, a Māori student identified that racist assumptions and stereotypes within their university were common and impacted on their wellbeing,

A lot of people just say, ‘Oh they only got into med school because they’re Māori or Pacific’. But no, they worked their butt off to get in there! You have to have a really good GPA to get into med school whatever race you are. So I guess there is racism in that sense of competitiveness at university. (Mayeda et al., Citation2014, p. 175)

The presence of successful Indigenous peers in higher education was perceived by Indigenous students as motivating. A Pacific Islander student from Tonga emphasised:

When we see other Pacific Islanders doing it, we tend to follow the same pathway … Seeing somebody else who has done it, that’s a pretty big thing. It’s helped, coming to uni, first year, seeing other Tongans who have succeeded in the same field. It’s just given you that extra push, to work that little bit harder. (Mayeda et al., Citation2014, p. 172)

A Mixtec Mexican Indigenous college student advocated that college classes should embrace students’ cultural identity and foster activities that enable students to share their cultural identity and, thus, feel culturally safe and comfortable:

So, I believe it’s important to have classes or workshops or at least identify each student with their own culture, with their identity and value that child, respect that child and not make fun of him because … making fun of a child because of his identity, certain identity … to be from a culture, it closes the door for that child. It’s like they feel embarrassed and next time they aren’t going to say they’re Mixtec [Ñuu Savi] because someone made fun of him or her. (Sānchez, Citation2020, p. 38)

Lack of culturally appropriate wellbeing services

In the included studies, Indigenous students advocated for more inclusive social and emotional wellbeing services. A First Nations student from Australia advocated for a more inclusive wellbeing service, ‘I think the promotion or addition of LGBTQI services or mentors to Nura Gili programs would be extremely beneficial’ (Schwartz, Citation2018, p. 19).

Another Australian First Nations student, reflecting on their experience with the Student Disability Unit, said, ‘I had a really hard time talking with [Student Disability Unit] just to get special consideration for exams and I felt like I didn’t get enough help’ (Schwartz, Citation2018, p. 19). Students felt that it was the university’s responsibility and duty to provide accessible and culturally safe wellbeing programs and services that connect better with Indigenous students’ social and emotional wellbeing needs.

I feel like they should be a bit more responsible for our mental health. A lot of the courses put us under a lot of pressure and they do run a mental health week but sometimes I feel like it doesn’t necessarily apply – it isn’t appropriate for Indigenous people, it’s a little bit hard to connect with it as well. So I don’t necessarily engage in those activities, it seems a little bit distant from us and what we need. (Powell, Citation2017, p. 56)

Home sickness

Many Indigenous students who live far away from higher education institutions were required to move away from home and leave loved ones behind in order to pursue a higher education pathway. Indigenous higher education students living in regional, rural and remote areas reported that there were many challenges whilst navigating living out of home. Much of these challenges burdened their social and emotional wellbeing. For example, a First Nations student from Australia explained the difficulty of living away from family whilst managing living costs and acknowledged it as an issue for all students studying away from home.

Transport issues are huge, finances are huge, living away from families are huge, and you know, family’s family, it doesn’t matter where you are, but it is not the same as your own mum and dad, and brothers and sisters. So I guess people can get homesick, I mean I’ve lived away too, and I’ve hated it. And that’s just not you know in Indigenous communities, that is in the broader population as well, so we are not alone as far as that sort of stuff goes. (Kippen et al., Citation2006, p. 5)

Another student from Australia also voiced the importance of family in providing a support network and motivation to keep studying.

I always keep in touch with my family regularly. It makes me miss them but also helps me to keep going and knowing that I can call them and they’ve got time to listen and be there for me even though it’s a bit extended, it’s a long way. (Powell, Citation2017, p. 36)

Financial stress and need for support

An Australian First Nations student reflected on the impact of their personal commitments and finances in affecting their mental health and studies, ‘For me, the times I struggled the most … more generally was when my personal life wasn’t going too well – e.g. good accommodation, work, financially and family matters back home’ (Schwartz, Citation2018, p. 18). Similarly, a Māori student reported: ‘Having to give up full-time work to study meant I could not afford food for myself and my daughter most weeks’ (Theodore et al., Citation2017, p. 126).

This quote highlights the importance of universities supporting students’ social, cultural and financial wellbeing outside of higher education.

Financial support such as assisting with accommodation and living cost scholarships, promoting more employment and career opportunities and being more flexible to enable students to visit family and cultural responsibilities such as being back on Country were deemed as useful suggestions. Notably, it is important to emphasise that Indigenous wellbeing is holistic, therefore, if one’s financial wellbeing is affected, so is their ability to support family and have good mental health.

Whilst scholarships are critical to assist students’ financial wellbeing, there is limited availability for all students, including the scholarship fund not being financially sufficient to support high living costs, particularly in big cities, and for Indigenous students with children to support. Hence, offering larger scholarships could help alleviate financial stressors for Indigenous students.

A First Nations student from Australia emphasised that a key problem was:

‘A lot of juggling of finances. A lot of people get into debt. I couldn’t find scholarships’ (Barney, Citation2016, p. 6). Mature age students found this especially difficult in regard to added responsibilities, ‘A lot of the Indigenous HDR students might be mature age, might have a family or have other competing pressures, and the standard scholarships just don’t cut it, for it can create an enormous pressure that, ultimately, is too much’ (Barney, Citation2018, p. 17).

Further, students advocated to receive more support from their university in alerting them to the availability of scholarships and helping them apply for them. For example, a Māori student voiced that: ‘There are scholarships, but we are not told how to apply. So, if someone could help with the scholarships and explain how to apply for them, that might help a little bit as well’ (Chittick et al., Citation2019, p. 17).

Negotiating with family

Studying, for many students, requires sacrificing time with family. One Australian First Nations student expressed the reality of study and the challenges it brings with negotiating one’s study, personal life and overall wellbeing. For example, ‘It takes that sort of sacrifice; it takes that sort of negotiating with your family' (Barney, Citation2018, p. 19). Studying away from home can be a challenge, especially if a student is the first person in their family to study at a higher education level. For instance,

'With my family it’s been a little bit difficult because as I said, I’m the first person to go to university, some of my family members kind of think that I’m almost making myself be better than them and trying to one up them in one sense' (Powell, Citation2017, p. 36).

'I always have to make sure that my assignments are done as soon as I get them, when that phone rings and it’s family calling, I know I am in the car and driving back to community, that’s just how it is’ (Toombs & Gorman, Citation2010, p. 15). Similarly, a Māori student noted as a key barrier: ‘The interruptions of whānau/hapū/iwi [extended family/subtribes/tribes] who need support in life generally. There is a pull when family calls for help and the studies go on the back burner while decisions and help are put into place’ (Theodore et al., Citation2017, p. 126).

Therefore, higher education can cause many students to juggle responsibilities and roles and, thus, can be a challenge to their relationships with family and thus wellbeing. Hence, family and kinship was identified as a challenge to Indigenous wellbeing.

Discussion

A systematic literature review methodology was selected as the most appropriate method to: (1) Provide an overview of nature and scope of qualitative literature that capitalised upon the voices of Indigenous higher education youth, and (2) Identify globally the Indigenous youth-identified enablers and barriers to wellbeing. The benefits of a systematic literature review methodology was to gain a global lens and overview of the research which engaged in Indigenous youth voice. A core strength of our research is that it synthesises the available research in relation to Indigenous higher education students’ voices and agency in wellbeing research. However, the nature and scope of international research focusing on Indigenous higher education students’ voices about their wellbeing whilst useful was limited in nature and scope. Many studies lacked a direct focus on student wellbeing, and wellbeing was often assumed or inferred rather than being a direct research focus. Only 28 studies globally were identified that included Indigenous higher education students’ voice with regard to wellbeing, and these were derived from only five countries (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Pacific Islands and Mexico). Hence, the research in this area is limited in nature, scope and culturally diverse Indigenous samples globally. This limitation suggests researchers may not be aware of the value and importance of focusing on Indigenous higher education youth. It is also evident that there remains to be little research specifically focusing on Indigenous student wellbeing in the university landscape. Another limitation includes the limited volume of student quotes and youth voices featured in the studies. Instead of listening to youth voices, most studies valued stakeholders’ perspectives (e.g. academic staff and community) and failed to include a greater representation of student youth voice. This specific limitation, however, was not reflected in the CASP results due to the nature of the appraisal checklist not accounting for quality considerations pertaining specifically to Indigenous research. These results imply that additional quality considerations are needed pertaining to Indigenous research.

Analysis of data revealed that the enablers of Indigenous higher education wellbeing are: Indigenous student centres and units, peer community support and resilience to be critical enablers of enhancing higher education youth’s wellbeing. Barriers to wellbeing included: Culturally unsafe higher education environments, lack of culturally safe and appropriate wellbeing services, home sickness such as separation from family while studying, negotiating with family and financial stress. Our findings emphasise what previous research has continued to advocate for, which is for higher education institutions to create more culturally safe environments which embrace Indigenous students’ cultural identity and creates a sense of belonging for students (Bin-Sallik, Citation2003; Kidman, Citation2020; Rochecouste et al., Citation2014; Sherwood & Russell-Mundine, Citation2017). Higher education institutions could support Indigenous students by employing more Indigenous academic staff and support staff such as community Elders, to enhance Indigenous representation and provide cultural support. Embedding Indigenous knowledge, voices and perspectives into the academy and enabling higher education spaces to be a place of belonging for all Indigenous peoples could also be beneficial. Culturally safe, accessible and free counselling and wellbeing services within higher education institutions were also voiced by Indigenous youth as critical to supporting their social and emotional wellbeing.

Assisting with accommodation and living cost scholarships, promoting more employment and career opportunities and being more flexible to enable students to visit family and address cultural responsibilities such as being back on Country were also considered useful by students. Whilst scholarships are critical to assist students’ financial wellbeing, there is a limited availability for all students, including the scholarship fund not being financially sufficient to support high living costs, particularly in big cities and for Indigenous students with children to support.

These findings suggest that increasing scholarships may assist students’ success in higher education by enabling financial wellbeing. Moreover, transforming higher education institutions into a place of cultural safety that embraces and uplifts the cultural identities and worldviews of Indigenous people should remain a priority for academics, staff and educators, advocating for higher education institutions to change their spaces into a place of Black excellence and leadership (Fredrickson, Citation2009; Sherwood & Russell-Mundine, Citation2017).

Implications for future research, theory and practice

Future systematic literature reviews could assess how studies foster culturally respectful research participant relationships. It could also be useful to identify if studies have Indigenous researchers and the extent to which research was conducted in partnership with Indigenous youth and communities. Therefore, future research could benefit from being more transparent in describing relationships with participants, detailing recruitment procedures and clarifying methodology. Indeed, the majority of studies would be classified as high quality per the CASP analysis, yet considerations regarding the primary source of data (i.e. from Indigenous voices versus non-Indigenous voices), and the inclusion of Indigenous researchers, are not included in this quality appraisal.

We suggest that future research could benefit from the development of a critical appraisal approach with a focus on the analysis of the employment of Indigenous theory, research and practice and ethical considerations of working with Indigenous peoples and communities within an educational context. Given theory, research and practice are inextricably intertwined such that a weakness in one area results in a weakness in others, it would also be useful to analyse the extent to which studies employed Indigenous theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches.

Significance of research

The significance of the findings from this research offer new directions for research and practice. The importance of placing First Nations higher education youth’s voices, knowledge, and perspectives at the epicentre of future higher education research was identified to advance theory, research and practice. This research is unique in that it assesses the nature and scope of qualitative studies and highlights the gaps and practices qualitative researchers should adopt when assessing Indigenous research and community engagement projects, including ensuring respectful research partnerships and relationships are established and Indigenous values and principles enacted.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review included data from 28 studies leveraging the voice of Indigenous youth in higher education about their perspectives on wellbeing. The depth of extant research suggests there is a dire need for a body of evidence from diverse Indigenous cultures to explore Indigenous higher education students’ conceptualisations of wellbeing and in particular their academic wellbeing to ascertain Indigenous-derived strategies for enabling higher education retention and completion. The results of this research also serve to identify some of the enablers and barriers of wellbeing, along with Indigenous-derived strategies for enhancing retention and completion. This research suggests that much more needs to be done in enabling Indigenous higher education youth to ascertain what works for them. Given there is now an array of Indigenous graduates in the workforce, we advocate much could be learned from them about their success, and how to augment and replicate it more broadly.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akuhata-Huntington, Z. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on Māori University students. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/543367

- Amundsen, D. L. (2019). Student voice and agency for indigenous maori students in higher education transitions. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 59(3), 405–434. https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10289/13620/Student%20Voice%20and%20Agency%20for%20Indigenous%20Maori%20students%20in%20higher%20education%20transitions.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Arriangada, P. (2021). The achievements, experiences and labour market outcomes of first nations, métis and inuit women with bachelor’s degrees or higher. Statistics Canada = Statistique Canada. http://indigenousnurses.ca/sites/default/files/inline-files/StatsCan%20Report%20LabourMkt-eng.pdf

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2018). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescent and youth health and wellbeing. cat. no. IHW202. Retrieved August 7, 2019, from. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/b40149b6-d133-4f16-a1e8-5a98617b8488/ihw-202-aihw.pdf.aspx?inline=true%20report%20Indigenous%20youth%20well-being

- Babineau, J. (2014). Product review: Covidence (systematic review software). Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association / Journal de l’Association des bibliothèques de la santé du Canada, 35(2), 68–71. https://doi.org/10.5596/c14-016

- Bailey, A. K. (2020). Racism within the Canadian University: Indigenous Students’ Experiences [ Doctoral dissertation]. McMaster University. McMaster University Libraries Institutional Repository.

- Barnes, M. K., & McCreanor, T. (2019). Colonisation, hauora and whenua in aotearoa. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 49(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2019.1668439

- Barney, K. (2013). ‘Taking your mob with you’: Giving voice to the experiences of Indigenous Australian postgraduate students. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(4), 515–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.696186

- Barney, K. (2016). Listening to and learning from the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students to facilitate success. Student Success, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v7i1.317

- Barney, K. (2018). Community gets you through: success factors contributing to the retention of aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Higher Degree by Research (HDR) Students. Student Success, 9(4), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v9i4.654

- Behrendt, L. Y., Larkin, S., Griew, R., & Kelly, P. (2012). Review of higher education access and outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Final report. https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/bitstream/10453/31122/1/2013003561OK.pdf

- Benton, M., Hearn, S., & Marmolejo-Ramos, F. (2021). Indigenous students’ experience and engagement with support at university: A mixed-method study. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 1–9. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/australian-journal-of-indigenous-education/article/abs/indigenous-students-experience-and-engagement-with-support-at-university-a-mixedmethod-study/8B9B9645217E8B367AF18A2D5DB05B5F

- Bessarab, D., & Ng’andu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

- Bewick, B., Koutsopoulou, G., Miles, J., Slaa, E., & Barkham, M. (2010). Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well‐being as they progress through university. Studies in Higher Education, 35(6), 633–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903216643

- Bin-Sallik, M. (2003). Cultural safety: Let’s name it! Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 32(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1326011100003793

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, L. (2010). Nurturing relationships within a space created by “indigenous ways of knowing”: A case study. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 39(S1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1375/S1326011100001095

- Butler, L. T., Anderson, K., Garvey, G., Cunningham, J., Ratcliffe, J., Tong, A., Whop, L. J., Cass, A., Dickson, M., & Howard, K. (2019). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s domains of wellbeing: A comprehensive literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 1982(233), 138–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.06.004

- Canel-Çınarbaş, D., & Yohani, S. (2019). Indigenous Canadian university students’ experiences of microaggressions. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 41(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-018-9345-z

- Carter, J., Hollinsworth, D., Raciti, M., & Gilbey, K. (2018). Academic ‘place-making’: Fostering attachment, belonging and identity for indigenous students in Australian universities. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1379485

- Chirgwin, K. S. (2014). Burdens too difficult to carry? A case study of three academically able Indigenous Australian Masters students who had to withdraw. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(5), 594–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.916014

- Chittick, H., Manhire, K., & Roberts, J. (2019). Supporting success for Maori undergraduate nursing students in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Kai Tiaki Nursing Research, 10(1), 15–21. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.836905608412978

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2019). Closing the gap. Prime Ministers Report 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2020, from https://ctgreport.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/ctg-report-2019.pdf?a=1

- Commonwealth Youth Awards. (2020). Youth Awards. Accessed 1 March 2021 Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Retrieved February 11, 2020, from https://thecommonwealth.org/cya

- Dodd, H. R., Dadaczynski, K. O., McCaffery, K. J., & Pickles, K. (2021). Psychological wellbeing and academic experience of university students in Australia during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030866

- Dudgeon, P., Bray, A., D’Costa, B., & Walker, R. (2017). Decolonising psychology: Validating social and emotional wellbeing. Australian Psychologist, 54(3), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12294

- Dudgeon, P., Gibson, C., & Bray, A. (2020). Social and emotional well-Being: Aboriginal health in aboriginal hands. Indigenous Studies, University of Western Australia; School of Health and Rehabilitation Science, University of Queensland.

- Durie, H. M. (1984). “Te Taha Hinengaro”: An integrated approach to mental health. Community Mental Health in New Zealand, 1(1), 4–11.

- Durmush, G., Craven, R. G., Brockman, R., Yeung, A. S., Mooney, J., Turner, K., & Guenther, J. (2021). Empowering the voices and agency of Indigenous Australian youth and their wellbeing in higher education. International Journal of Educational Research, 109(2021), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101798

- Durmush, G., Craven, R. G., Yeung, A. S., Mooney, J., Horwood, M., Duncan, A., Franklin, C., & Gillane, R. (2023). Enabling Indigenous wellbeing in higher education: Indigenous Australian youth-devised strategies and solutions. Higher Education, 87(5), 1357–1374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01067-z

- Fredrickson, B. (2009). Positivity: Groundbreaking research reveals how to embrace the hidden strength of positive emotions, overcome negativity, and thrive. Crown Publishers/Random House.

- Gall, A., Diaz, A., Garvey, G., Anderson, K., Lindsay, D., & Howard, K. (2021). Self-reported wellbeing and health-related quality of life of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people pre and post the first wave of the COVID-19 2020 pandemic. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 46(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13199

- Garvey, G., Rolfe, E. I., Pearson, S., & Treloar, C. (2009). Indigenous Australian medical students’ perceptions of their medical school training. Medical Education, 43(11), 1047–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03519.x

- Gorman, E. (2017). Blackfullas in ivory towers: Referenced reflections of a Bundjalung graduate nurse. Contemporary Nurses, 53(6), 691–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2017.1409645

- Handy, E. S., & Pukui, M. K. (1972). The Polynesian Family System in Ka’u. Tuttle.

- Hearn, S., & Kenna, K. (2020). Spending for Success: Identifying ‘what works?’ for indigenous student outcomes in Australian Universities. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 50(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2020.27

- Hill, B., Winmar, G., & Woods, J. (2020). Exploring transformative learning at the cultural interface: Insights from successful Aboriginal university students. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 49(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2018.11

- Hinde, S., & Spackman, E. (2015). Bidirectional citation searching to completion: An exploration of Literature Searching Methods. PharmacoEconomics, 33(1), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0205-3

- Hollinsworth, D., Raciti, M., & Carter, J. (2020). Indigenous students’ identities in Australian higher education: Found, denied, and reinforced. Race Ethnicity and Education, 24(1), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1753681

- Hop Wo, K. N., Anderson, K. K., Wylie, L., & MacDougall, A. (2019). The prevalence of distress, depression, anxiety, and substance use issues among Indigenous post-secondary students in Canada. Transcultural Psychiatry, 57(2), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461519861824

- Hutchings, K., Bodle, K., & Miller, A. (2018). Opportunities and resilience: Enablers to address barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to commence and complete higher degree research programs. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2. https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/informit.106269539902101

- Indigenous Allied Health Australia. (2020). Expression of interest: Canada and Australia indigenous health and wellbeing youth committee. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from. https://iaha.com.au/expression-of-interest-canada-and-australia-indigenous-health-and-wellbeing-youth-committee/

- Kidman, J. (2020). Whither decolonisation? Indigenous scholars and the problem of inclusion in the neo-liberal university. Journal of Sociology, 56(2), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319835958

- Kippen, S., Ward, B., & Warren, L. (2006). Enhancing Indigenous participation in higher education health courses in rural Victoria. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 35(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1326011100004117

- Kugley, S., Wade, A., Thomas, J., Mahood, Q., Jorgensen, K. A., & Hammerstrom, S. N. (2015). Searching for studies: A guide to information retrieval for Campbell systematic reviews. Campbell Methods Guides. https://doi.org/10.4073/cmg.2016.1

- Lydster, C., & Murray, J. (2019). Understanding the challenges, yet focusing on the successes: An investigation into Indigenous university students’ academic success. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 48(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2018.15

- Mayeda, T. D., Keil, M., Dutton, D. H., & Ofa Mo’oni, I. (2014). “You’ve Gotta Set a Precedent”: Māori and Pacific voices on student success in higher education. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 10(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011401000206

- McCubbin, L. D., & Marsella, A. (2009). Native hawaiians and psychology: The cultural and historical context of indigenous ways of knowing. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(4), 374–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016774

- McHugh, L. M. (2012). Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3). file:///C:/Users/S00270926/Downloads/McHugh%20(2012).pdf

- Milne, T., Creedy, K. D., & West, R. (2016). Integrated systematic review on educational strategies that promote academic success and resilience in undergraduate Indigenous students. Nurse Education Today, 36, 387–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.10.008

- National Youth Council. (2020). Singapore Youth Award 2019: Leading change, one wave at a time. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from. https://www.nyc.gov.sg/en/stories/sya-2019-recipients/

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, E. D., & Moules, J. N. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Pidgeon, M. (2008). Pushing against the Margins: Indigenous Theorizing of “Success” and Retention in Higher Education. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 10(3), 339–360. https://doi.org/10.2190/CS.10.3.e

- Powell, M. (2017). Indigenous wellbeing in university spaces: Experiences of Indigenous students at the Australian National University. The Artic University of Norway.

- Prowse, R., Sheratt, F., Abizaid, A., Gabrys, L. R., Hellemans, G. C. K., Patterson, R. Z., & McQuaid, J. R. (2021). Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining gender differences in stress and mental health among university students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7(12). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.650759

- Rawana, S. J., Sieukaran, D. D., Nguyen, T. H., & Pitawanakwat, R. (2015). Development and evaluation of a peer mentorship program for Aboriginal university students. Canadian Journal of Education, 38(2), 1–34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/canajeducrevucan.38.2.08

- Rochecouste, J., Oliver, R., & Bennell, D. (2014). Is there cultural safety in Australian universities? International Journal of Higher Education, 3(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v3n2p153

- Sānchez, K. G. (2020). Reaffirming Indigenous identity: Understanding experiences of stigmatization and marginalization among Mexican Indigenous college students. Journal of Latinos and Education, 19(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2018.1447484

- Schwartz, M. (2018). Retaining our best: Imposter syndrome, cultural safety, complex lives and Indigenous student experiences of law school. Legal Education Review, 28(2), 1–25. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from https://ler.scholasticahq.com/article/7455-retaining-our-best-imposter-syndrome-cultural-safety-complex-lives-and-indigenous-student-experiences-of-law-school

- Sherwood, J., & Russell-Mundine, G. (2017). How we do business: Setting the agenda for cultural competence at the University of Sydney. In J. Frawley, J. S. LarkRin, & J. Smith (Eds.), Indigenous Pathways, Transitions and Participation in Higher Education (pp. 1–15). Springer.

- Slatyer, S., Cramer, J., Pugh, J. D., & Twigg, D. E. (2016). Barriers and enablers to retention of Aboriginal diploma of nursing students in Western Australia: An exploratory descriptive study. Nurse Education Today, 42, 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.03.026

- Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies. Zed Books.

- Stahl, G., McDonald, S., & Stokes, J. (2020). ‘I see myself as undeveloped’: Supporting Indigenous first-in-family males in the transition to higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1488–1501. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1728521

- Statistics Canada. (2021). Chapter 4: Indigenous youth in Canada. Portrait of youth in Canada: Data report, Canada, December, 2021 (cat. no.42‐28‐0001). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/42-28-0001/2021001/article/00004-eng.pdf?st=tfoQZtc9

- Sutherland, S., & Adams, M. (2019). Building on the definition of social and emotional wellbeing: An Indigenous (Australian, Canadian, and New Zealand) viewpoint. Ab-Original: Journal of Indigenous Studies and First Nations and First Peoples’ Cultures, 3(1), 48–72. https://doi.org/10.5325/aboriginal.3.1.0048

- Theodore, R., Gollop, M., Tustin, K., Taylor, K. N., Kiro, C., Taumoepeau, C. M., Kokaua, J., Hunter, J., & Poulton, R. (2017). Māori University success: What helps and hinders qualification completion. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 13(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117700799

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, C. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(181), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

- Toombs, M. (2011). What factors do Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students say affect their social and emotional wellbeing while at university?. University of Southern Queensland. https://eprints.usq.edu.au/19644/2/Toombs_2011_whole.pdf

- Toombs, M., & Gorman, D. (2010). Why do Indigenous students succeed at university? Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, 34(1), 14–16. https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/ielapa.650949518709372

- Trimmer, K., Ward, R., & Wondunna-Foley, L. (2018). Retention of Indigenous pre-service teachers enrolled in an Australian regional university. Teaching and Teacher Education, 76, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.08.006

- Trudgett, M. (2009). Build it and they will come: Building the capacity of Indigenous units in universities to provide better support for Indigenous Australian postgraduate students. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 38(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1375/S1326011100000545

- United Nations. (2022). Sustainable Development Goals: Quality Education. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/education/

- Universities Australia. (2022). Indigenous Strategy 2022–2025. https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/UA-Indigenous-Strategy-2022-25.pdf

- Walton, P., Hamilton, K., Clark, N., Pidgeon, M., & Arnouse, M. (2020). Indigenous university student persistence: Supports, obstacles, and recommendations. Canadian Journal of Education, 43(2), 431–464. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1262710.pdf

- Wiley, E., Khattab, S., & Tang, A. (2020). Examining the effect of virtual reality therapy on cognition post-stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 17(1), 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2020.1755376