ABSTRACT

Children’s reading for pleasure is associated with significant academic and personal benefits and is widely recognised as an effective way to leverage social change, yet in schools this is not fully capitalised upon. The authors connect extant research in this area to the seminal concepts of Funds of Knowledge and Funds of Identity to advance the notion of Funds of Courage and unify literature on dark Funds of Identity and subjective sense, in order to put forward a volitional reading agenda that resonates with the urgent need to innovate reading curricula. The authors argue that the twin psychological pillars of Funds of Courage – resilience and vulnerability – can enable teachers to progress children’s volitional reading practices more reciprocally and thus play a role in advancing social justice. In drawing on examples from recent work with both emergent and established readers, primarily focused on early years and early primary education in England, they seek to widen conceptual and practical understanding in this area.

There are multiple injustices in the 2020s, including the environmental crisis; racial injustices; and algorithmic biases. Children and their teachers read news that is easily manipulated with Artificially Intelligent algorithms and that unethically use their personal data to automatically recommend content based on commercial interests (Hobbs, Citation2020). They access novels that lack diversity, privilege White middle-class story heroes (Crisp et al., Citation2016) and are written by authors who reflect limited cultural diversity (CLPE, Citation2023; Short, Citation2018). In schools, too, whether through a remote learning offer or in person, concerns about ‘catch up’ from learning loss predominates. As Harmey and Moss (Citation2020) argue, it is ‘time to do things differently’.

To remediate the situation, a shift in perspective is needed that is structural, systematic and happens at socio-cultural as well as individual levels. The former demands engagement with cultural politics and work on institutional levels with policymakers and key stakeholders such as publishers, children’s authors and designers, in order to influence decisions with rigorous scientific evidence. The latter – the individual level – demands a shift in dispositions. In this paper, we focus on the dispositions of teachers and children who read for pleasure and who make discerned choices about accessing, producing and propagating texts that shape their own identities and those around them. With ‘we’, we refer here to researchers and educators, including ourselves. With texts, we refer to texts in any format (print, digital, hybrid) and of any genre (novels, poetry, comics, non-fiction and so on).

Internationally, there is growing recognition of the significance and value of reading for pleasure, or choice-led recreational reading, for young children. Reading for Pleasure (RfP hereafter) is positively associated with cognitive development, specific learning outcomes such as vocabulary and mathematics (Sullivan & Brown, Citation2015), academic achievement more broadly (Smith et al., Citation2012) and psychological wellbeing (Sun et al., Citation2023). In the last five years multiple studies have underscored the claim of enhanced attainment, both those that have mined the international PIRLS and PISA data sets (e.g. Cheema, Citation2018, Jerrim & Moss, Citation2019; Lindorff et al., Citation2023) and national studies (e.g. Locher & Becker Citation2019; Schugar & Dreher, Citation2017). The relationship between reading amount, reading frequency and reading comprehension is also evidenced by recent research (e.g. Gilleece & Eivers, Citation2018; Miyamoto et al., Citation2018; Troyer et al., Citation2019), alongside a reciprocal relationship between intrinsic reading motivation and reading attainment (e.g. Hebbecker et al., Citation2019).

To help ensure children accrue the benefits associated with being keen childhood readers, reader engagement needs to be promoted across schools, homes and communities in a way that ensures equal opportunity for all (Cremin et al., Citation2014; Scholes et al., Citation2020). Collaboration among educators, parents, policymakers and community leaders is essential to integrate reading for pleasure authentically into the curriculum and sustainably into reading cultures at home. This is the case for both traditional, paper-based reading as well as digital reading, the latter of which brings with it new forms of injustices (Scholes, Citation2023).

Yet, not all children have the same access to reading resources, support and practice in their schools or local communities, with research revealing, for instance, that those who live in areas of concentrated poverty experience markedly impoverished text access in these ‘book deserts’ (e.g. Neuman & Moland, Citation2016), and may also be held back by a ‘pedagogy of poverty’ in school (Hempel-Jorgensen et al., Citation2018). Such inequalities result in unequal reading opportunities, connected to various forms of injustice. For the purposes of this study, we narrow our focus to a specific manifestation of social injustice.

Our particular social-justice stance is fuelled by the apparent discrepancy between educational theories that honour children’s diverse reading approaches and educational practices that confine success to a set of measurable indicators (Bradbury, Citation2019; Hempel-Jorgensen et al., Citation2018; Roberts‐Holmes & Bradbury, Citation2016). While we, as researchers and educators, all have the power and entitlement to truth, we are caught in a system that privileges specific literacy identities and reproduces power hierarchies in the classroom. As Black et al.’s (Citation2021) documentation of the schoolified discourses of young people shows, schools are sites of power manifestations and exchanges which are re-enacted in homes and surface in children’s knowledge. González (Citation2005) challenges educators to ask ‘so what’ questions in order to address research and practice tensions, and Esteban-Guitart (Citation2021) asserts that educators need to engage with the generative process of translating lived realities into present and future realities. We follow their call in this conceptual paper and reflect on the personal attitudes and dispositions that need to be mobilised to support children’s recreational reading.

We suggest that these dispositions are about teachers’ and students’ shifts in perceptions of their subjective stance. For these shifts to be transformative and humanising, they need to be embedded in what we, as authors, term, and explicate, as Funds of Courage. Drawing on our work in this area, primarily focused on early years and early primary education in England, we outline how Funds of Courage could act as a new guiding principle for RfP.

A note on terminology

Reading research is a fragmented field, with often opposing vantage points and the absence of a shared vocabulary (see Flippo, Citation2012). It is therefore important to define what we mean by the three main terms used in this paper: social justice; literacies; and RfP. Justice could be conceived of as the opposite force for violating one’s right to equality, equity or fairness. In this paper we aim to fulfil a larger aim of showing how children’s reading identities are shaped by established ideas about reading and how these ideas are rooted in systemic inequities and disparities that perpetuate injustice. Among the many conceptualisations of social justice, we intentionally conceive of it broadly and consider how social justice presumes notions of fairness, dignity and worth of every human being. The emphasis on social justice is a deliberate choice to foreground the collective and shared, as opposed to the individual right for justice (Capeheart & Milovanovic, Citation2020). This concept of social justice is rich enough to encompass the equal and equitable connection between individual human beings, between humans and non-humans and between humans/non-humans and the space they inhabit on Earth. It is this layered concept of social justice that informs contemporary reading studies (see Aukerman & Chambers Schuldt, Citation2021) and that we follow in our work.

We focus on literacies as a combination of reading and writing, with analogue and digital resources, in cognisance of their multiple, multimodal and context dependent nature (Street, Citation2006). Acknowledging the Internet as the current defining technology for learning, the shift of literacies from page to screen, and the changing nature of communication habits, indicates that literacies are dynamic and are not bound to a technology, group of readers/writers or medium of expression (Burnett & Merchant, Citation2020). There are many types and kinds of literacies to facilitate comprehension and meaning-making, for example skills required for acquiring information online, communication via letters or text messages, or participating in a written chat (see Coiro et al., Citation2008). In this paper, we build on E. B. Moje and Luke’s (Citation2009) emphasis on ‘popular cultural textual practices’ (p. 3) in that in conceptualising RfP we include children’s engagement with literacy apps, social media stories and e-books as well as print books. We focus on a specific engagement in literacy: reading for pleasure.

Reading is essential for academic achievement and full participation in everyday, civic life. Reading for pleasure is used interchangeably in research and practice contexts with reading for enjoyment (Cox & Guthrie, Citation2001), out-of-school reading engagement (Schugar & Dreher, Citation2017), free reading (McQuillan, Citation2019), ludic reading (Nell, Citation1988) and, in our own definition, reading characterised by delight, desire and diversity (Cremin, Citation2007). As the term indicates, it is a type of reading that has positive attitudes and enjoyment at its core, together with readers’ volition, agency and interest in voluntary, recreational reading.

There is a closely knit connection between children’s RfP and social justice, since, as effectively summarised by the OECD’s Reading for Change report (OECD, Citation2020), RfP is linked to social mobility and is an important indicator of a child’s future success; those who read for pleasure in childhood enhance the rate of their learning and later cognitive development (Sullivan & Brown, Citation2015; Sun et al., Citation2023). Indeed, as Rundell (Citation2019) argues, children’s reading of fiction is where social justice starts: ‘It’s to children’s fiction that you turn if you want to feel awe and hunger and longing for justice: to make the old warhorse heart stamp again in its stall’ (Rundell, Citation2019, p. 39). If we are to achieve educational equity, it becomes a moral imperative to promote children’s volitional reading and this needs to be framed within a solid framework.

Reading for pleasure plays a part in several research arenas, some of which have inherent tensions. Sarland (Citation1995) argues that research on reading is split between functional literacy and the broader, claimed benefits of ‘real books’. This division has long been acknowledged as unproductive, highlighting a need for a unified, comprehensive approach that evaluates literacy practices and their underlying cultural and ideological contexts. Additionally, Ashbridge et al. (Citation2022) observe a contradiction between English educational policy and the need for critical literacy, emphasised by recent global events like the COVID-19 pandemic. These scholars argue that since 2010, policies have leaned towards neoliberal priorities, making the implementation of critical literacy an imperative. These crucial real-world issues contextualise our approach to RfP.

The theoretical bases that have guided our work and that of many other educational researchers over the past two decades are Funds of Knowledge and Funds of Identity.

Funds of knowledge

The initial use of the Funds of Knowledge (FoK) concept in educational settings dates back to the late 1980s (Llopart & Esteban-Guitart, Citation2018), but significant advancements of the concept have emerged since. This ongoing progression underscores the continued relevance of the FoK approach as a tool to counteract persistent deficit perspectives prevalent in education, and to develop culturally sensitive and contextually grounded curricular activities. The FoK notion emerged from Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) socio-cultural approach to learning that positioned children’s life-world knowledge acquired outside of formal learning environments as tools and signs that are compatible with growth, achievement and wellbeing. From decades of research within the FoK approach (e.g. Moll, et al.,Citation1992,; Moll et al., Citation2013), we know that households possess rich assets of everyday literacies. For holistic learning, teachers need to actively engage with families’ FoK, that is the languages, histories and cultural practices that children bring to the classroom (Moll, Citation1992) and the socio-cultural-political contexts in which they grow up (González, Moll & Amanti, Citation2006).

Acknowledging individuality within each culture and family does not mean disposing of the idea of culture. Indeed, González et al. (Citation2011, p. 484) make it clear that no household contains ‘only individualized “funds” of knowledge’. Rather, FoK connects the unique cultures developed at home, school and community and recognises the extent to which objects and symbols are both culturally co-constructed and embedded in a cultural context. Leveraging a FoK approach involves an inquiry process that connects the diverse skills and forms of knowledge in communities with those offered at school. In the process, it empowers teachers and children to create relationships that transform their daily practices, both in schools and at home. The merits of this approach are illustrated in its not inconsiderable follow-up among educational professionals (see Hogg, Citation2011, for an overview).

With our diverse FoKs, we all shape and absorb what counts as knowledge and which source of knowledge (e.g. community or popular culture [see Hogg, Citation2011]) gets elevated in our practice. Ergo, we all are responsible for the reading cultures that get highlighted as more or less valid in the current times. So that a socially just change in children’s RfP practice occurs, it is essential to challenge dominant power discourses about what counts as reading and how it is taught in schools, and for communities’ diverse FoKs to be made manifest in classrooms. One way of eliciting and representing diverse FoK is to consider children’s Funds of Identity.

Funds of identity

Following the identity turn that occurred in literacy studies in the first decade of the twenty-first century (see E. Moje et al., Citation2009), researchers have been seeking ways to capture the multiple and hybrid forms of personal and social identity that are mediated by others and the ‘self’.

Saubich and Esteban-Guitart (Citation2011) coined the term Funds of Identity to expand the FoK framework with attention paid to the diverse identities of individuals, that is the agents of literacies situated and distributed within and outside classrooms. The Funds of Identity (FoI hereafter) framework defines the diverse literate and social practices as ‘historically accumulated, culturally developed, and socially distributed resources that are essential for a person’s self-definition, self-expression, and self-understanding’ (Esteban-Guitart & Moll, Citation2014, p. 31). Put differently, FoI are ‘a set of resources or box of tools and signs’ (p. 37) that individuals access as they seek to define their position in society and in relation to others. In the case of teachers, their personal identities are often in conflict with their professional identities, which are influenced by the socio-political ideas about teachers’ role in society, as well as teachers’ past and present aspirations about who they want to be (Ball, Citation2003; Cremin, Citation2019; Day et al., Citation2006). FoI is distinct from FoK in that it focuses on funds that are personally meaningful for students (Hogg & Volman, Citation2020). In both FoK and FoI, personal identities are intertwined with collective identities, and this mutuality includes contexts, symbols and tools of which the individuals themselves are a part.

The FoK and FoI frameworks have helped us as authors understand the challenges and opportunities in children’s RfP practices and those represented by their communities. While FoK highlight the rich and diverse cultural knowledge and resources that children and their communities possess, based on their lived experiences, FoI foreground children’s life experiences that help them to define themselves (Subero et al., Citation2017). Both feed into how children perceive and enact RfP. The conceptual gap that we identify in the FoK and FoI work relates to the refinement of dispositions that are necessary for mobilising teachers’ and children’s funds in contexts such as the recent COVID-19 crisis or a war conflict, that is situations where societal structures collapse, identities falter and texts for guiding readers become unavailable and contested. We explicate this gap by drawing on the Reading for Pleasure literature and social-justice-oriented work in this area.

Reading for pleasure and FoK

The key objective of FoK to shift the deficit thinking in education (Esteban-Guitart, Citation2021) stands in stark contrast to the standardised assessments in many national reading curricula that propagate a culture of skilling students or ‘inculcating them with certain discrete, measurable abilities, as outlined in state curriculum standards’ (González et al., Citation2011, p. 485). The discourse of deficiency that seeks to constantly improve and upskill young readers arguably constrains the professional agency of educators who operate in cultures of high accountability (Cremin et al., Citation2015; Larson & Marsh, Citation2014; Orellana, Citation2009). FoK bring to the fore the fabric of social institutions and the practices that students and teachers use to develop definitions of their present and future selves. Far from being static processes, identification with a given culture and recognition of one’s own role within it are dynamic endeavours, in which knowledge and culture are distributed. The diversity and heterogeneity of knowledge sources in FoK are not semantic subtleties, but vital contributions to the understanding of children’s RfP. Educators’ perspectives on volitional reading influence their views of what children know and should know, which in turn shape and frame the ways in which RfP is positioned and promoted in classrooms.

According to the theory of distributed cognition (Cole & Engeström, Citation1993), the dynamic and heterogenous nature of culture implies its distribution among the lived experiences of individuals, but also the material and immaterial artefacts (tools and signs) used by the individuals. Rooted in Vygotskian formulations, tools materialise the socio-cultural processes relevant to social groups and give rise to individuals’ learning and transformation of their existing thinking. With digital texts and the immaterial meaning-making possibilities they offer, Burnett et al. (Citation2014) propose a focus on the relationship between material and immaterial and suggest (im)materiality as a new lens for studying literacy practices. Young people’s RfP practices are intertwined with digital technology, especially with technologies that can be personalised by adding users’ own content, such as their images or texts. The collaborative and participatory nature of new media enables young people to see and appropriate features of others’ texts and embed them into their daily material and immaterial lives. Such technologies co-construct FoK offered in and outside classrooms, as demonstrated by McLay and Renshaw (Citation2020), who outline how ‘young people themselves accomplish digital technology’ (italics our own).

The technologies, in particular the accelerated AI advancements, also challenge RfP practice on several grounds, with ethical and moral threats that come with convincing auto-generated yet fake texts. As we move to the era of social generative AI (Sharples, Citation2023), RfP theories need to be robust as the interaction between humans and artificial intelligences can be understood not merely as a sequence of prompts and responses, but as a dynamic social process resembling a natural, ongoing conversation. FoK and FoI’s rich theoretical ideas on contemporary literacy activities are at odds with school curricula that promote knowledge hierarchies and privilege narrowly defined and heavily ‘schooled’ versions of RfP practices (Hempel-Jorgensen et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, the currently dominant discourses in some national literacy curricula do not reflect the social-justice issues that require urgent attention. While efforts are being made to ‘decolonize’, ‘ungender’ and ‘deracialize’ aspects of the reading curriculum (for example diversifying the lists of authors mandated in national reading curricula, Beach et al., Citation2020; García & Kleifgen, Citation2020), the knowledge and identity processes involved in choice-led recreational reading arguably remain inadequately understood. In many national curricula, reading and writing are described as a set of skills to be taught in a stage-like process that can be measured and quantitatively compared over time and between groups of children. And yet, RfP in childhood is a highly social process and plays a fundamental role not only in raising achievement, but also in transforming children’s lives: ‘As other life experiences do, reading has the potential to transform us in transitory as well as lasting ways, and to make more likely desirable as well as undesirable behaviours’ (Schutte & Malouff, Citation2006, p. 255). RfP, with its portrayal of alternative realities in stories for instance, provides access to a world of contrasting and overlapping truths for the reader to consider. Indeed Morgan (Citation1997), reflecting the growing emphasis on critical literacy in educational curricula, reminds us that truth is constructed through language within a socio-historical context, and that this invariably benefits one particular group more than others.

If schools do not provide a space that honours both the community’s FoK and the children’s FoI, discontinuity between school and home is created, which contradicts students’ own experiences and represents a significant source of difficulties in the classroom. In other words, if a school follows a narrowly defined reading curriculum and attendant pedagogy that views and enacts literacy as a set of skills to be transmitted from teacher to learner, then the school fails in its social-justice mission. Kirkland (Citation2014) pointed this out when he wrote that

fields of teaching and learning have become increasingly vulnerable to losing social justice as a critical tenet to those who believe that the teaching of academic skills and knowledge alone, when aligned with standards, should ostensibly provide learners with the tools needed to bring about a more just society. (p. 585)

From the FoK and FoI perspective, the challenges that teachers and RfP researchers face in this social generative AI era are not new, in that they take place in a process of cultural change to embed lifeworld RfP knowledge in everyday teaching and learning in schools. To meet this challenge, we need to wrestle with the critical notion of theories that spotlight one aspect and neglect other aspects of reality. One difficulty with the FoK and FoI approaches is, as Zipin (Citation2009) and Oughton (Citation2010), acknowledge, the assumption that FoKs and FoIs are entirely positive assets that always enrich the curriculum. We problematise this understanding in the light of relevant literature and our own data.

Reading for pleasure constrained by funds of knowledge and identity

One difficulty with current RfP approaches in many US and UK public/state schools is that they pay lip service to the problematic facets of knowledge and identity that reside in homes. Zipin (Citation2009) refers to these issues as children’s ‘Dark Funds of Knowledge’ and argues for a greater recognition of their existence beyond schools. While this is a meaningful and necessary concept, the notion creates a tension between positive and negative FoK and FoI. This is in part resolved by Poole’s (Citation2020) retheorization that suggests that ‘dark and light’ FoKs and FoIs are part of intertwined internalised resources within an individual and a society. Lived experiences are internalised differently, depending on the narratives we tell ourselves and the narratives told by others about our shared experiences. Acknowledging the refraction concept embedded in Vygotsky’s notion of ‘perezhivanie’, (which guided some of the early conceptualisation of FoI), Poole (Citation2020) highlights the dynamism of experiences and identities, and posits that identity is to be understood in terms of ‘subjective senses’. We agree that extant research privileges positive FoI, and we adopt the subjective senses orientation as a way of overcoming the positive/negative emotions inherent in previous conceptualisations of FoK and FoI.

Poole (Citation2020) writes about the ‘irreducible totality of dichotomies (micro/macro, light/dark, negative/positive) in terms of the production of internal subjective senses that are also mediated and distributed by artefacts, people, spaces and activities’ (p. 411). Connecting to this argument, we posit that the deeply reciprocal and yet subjective senses of RfP pave the way for transformative, socially just pedagogies that are necessary for times when students interact with personalised AI tutors and texts produced by algorithms that are oblivious to students’ socio-cultural context and the complex ways in which they define themselves.

Our research into children’s literacy identities and the distributed and mediated nature of reciprocal RfP has revealed a lack of awareness of shared responsibility about societal injustices. Drawing on data from two separate year-long studies, involving 61 primary phase practitioners from diverse local authorities in England (Cremin et al., Citation2014, Citation2015), we describe reciprocal reading communities as those that honour the mutually reinforcing relationship between personal and collective literacy identities (Cremin, Citation2019). By contrast, the literacy identity represented by the curriculum, school and society is a more static personal identity. Yet, if teachers adopt an ethnographic lens as learners, that is if they engage in reading, reflection and discussion (Cremin et al., Citation2015), and develop their own ‘reflexive professional identities’ (Ryan and Barton, Citation2014), they may be enabled to take a wider view and reclaim their role in a data-driven curriculum (see Williamson, Citation2021).

The duality of reciprocal and subjective RfP challenges current thinking, habits and preconceptions of what volitional reading means for individuals and communities. If we are to change the status quo and enrich the reading curriculum with the red thread of RfP that connects readers to themselves, to others, to others’ lives and other worlds, then we need to mobilise the personal and social dispositions required to engender change. More specifically, we argue for mobilising qualitative markers of teachers’ and students’ dispositions to initiate and sustain change. It is in this refinement of dispositions that we locate the most acute conceptual gap in the FoK and FoI work. We address this conceptual gap with the concept of Funds of Courage.

Funds of courage

Our common humanity implies the right to equality, equitable treatment of differences and support for everyone’s rights. Yet we live in a society characterised by many forms of injustice – violence, discrimination, poverty, mistreatment, abuse – many of which were deepened during the COVID-19 pandemic (Patel et al., Citation2020) and continue to be affected by war conflicts with tragic traumatic, longer-term health and wellbeing consequences (Sheather, Citation2022). More than ever before, the task of educational researchers is complicated with the need to build strength and collaborative capacity in teachers, schools and homes to address these challenges. We pursue this task with a specific focus on dispositions.

As authors, we use the term dispositions here to refer to the individual and personal experience of justice within shared networks. It follows that literacy is not, and never can be, neutral: personal and social choices are connected. If we see literacy not only as socially situated, but also as a personal experience, we need to recognise the deeply personal and richly contextualised nature of social justice in RfP. Not all reading tools and practices (such as texts or book talk) are deemed equal and not all support equity and equality. So that we can more effectively promote knowledge and identities that demand fairness and dignity for all, we need to mobilise the possibilities for change that lie in individual dispositions. At the time of writing, teachers are having to navigate rapidly changing literacy practices, some of which are gradual and deep-seated, such as the transition to digital literacies, whilst others are sudden and transient, such as the shift to online reading/writing during pandemic lockdowns. In such scenarios, deficit discourses are often employed. The pandemic discourse portrayed children needing to ‘catch up’ due to ‘learning loss’ and argued educational gaps needed to be filled through specific strategies. However, such narratives fail to offer solutions that address the educational loss and empower students in the process (Harmey & Moss, Citation2023).

In such challenging contexts, it is important to support teachers and young readers to consider dispositions that go beyond their own funds of knowledge and identities and allow for shifts in perspective. We refer to these dispositions as ‘Funds of Courage’.

Funds of courage: vulnerability and resilience in RfP

Courage can be defined as a companion to creativity and an antidote to fear and self-doubt (Gilbert, Citation2016). Considered a virtue since Ancient Greece, Scarre (Citation2010) nonetheless cautions against viewing courage as a heroic or privileged virtue, given that the expression of courage changes according to context. We focus on courageous shifts in perspective that are both personal and social in nature and that, as Akkerman and Meijer (Citation2011) argued in relation to teachers’ identities, are both unitary and multiple. A dialogical – rather than dichotomous – approach to perspectives connects to the dynamism embedded in the FoI concept and to contemporary views of the ‘self’ as an ever-changing system of thoughts, perceptions and actions (Schwartz, Citation2001). Courage is critical to these interpretations of the self in processing experience and shaping action, as is the role of structure in enabling and constraining the acts of courage in which educators participate.

Building on the need for duality in FoK and FoI concepts, we connect to literature that describes courage in relation to vulnerability, and the disposition of recognising an individual and a collective sense of defencelessness in the face of unprecedented or unexpected events. In discussing social change and progress in her conversation with Krista Tippett (Citation2016), Frances Kissling is quotes with what she perceives as the most noble kind of courage, namely ‘the courage to be vulnerable in front of those we passionately disagree with’. This in turn connects to Brown’s (Citation2006) conceptualisation of vulnerability which, drawing on interviews with 215 women, can lead to innovation and change. Connecting to some of our own projects into reading and literacy, we note that the teachers in these projects were part of a system of high-stakes testing and a culture of performativity, where showing vulnerability could be perceived as under-performance and weakness. Yet with support, all of those participating, through their desire to find out about the children’s everyday literacy practices and FoK in the home, stepped beyond the safe context of school, and undertook visits to children’s homes, positioned as learners with an ethnographic eye (Cremin et al., Citation2015). In other words, these teachers took responsibility for their own vulnerability and demonstrated resilience in order to develop a more rounded picture of the children than that afforded by the system. Aware of their vulnerabilities, these UK based teacher-researchers, affiliated with our university Centre, put their professional identities to one side and risked sharing their own FoK and personal identities as parents and family members with children’s parents. Brown (Citation2006) argues such ‘consciousness rising’ can become a place for resilience.

Consciousness rising was evident in this study as many teachers ‘voiced a new respect for parents and were prompted to ponder on and question previously held perceptions about the families’ (Cremin et al., Citation2015, p. 181). In addition, modern parents and caregivers, especially mothers, grapple with the dual pressures of fulfilling parental roles and providing educational activities for their children, often feeling there are insufficient hours in the day to accomplish everything (Rose, Citation2017). This tension is compounded for migrant mothers, who are consumed with the struggle for survival, both mentally and materially (Moro, Citation2014). Migrant parents’ preoccupation with overcoming daily challenges may leave them with little time, space or the capacity to engage in activities such as reading for pleasure with their children. Arguably, the combination of vulnerability and resilience creates a contextually nuanced discourse that can open vistas around courage (Brown, Citation2006). In particular, their interplay can serve to create shifts in perspective and dispositions.

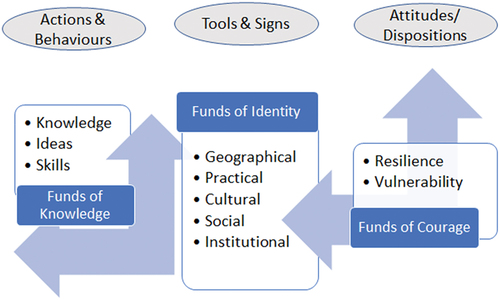

We put forward the thesis that vulnerability and resilience can expand the existing definitions of ‘funds’ (of knowledge and identity) rooted in the studies of Moll (Citation1992) and colleagues. Funds of Courage can be mobilised to shift perspectives, on a personal and a social level, connecting dynamically to the subjective sense. Mobilised Funds of Courage can shape new literacy identities that span the diverse FoKs and FoIs at home and in school, as well as demand social justice by ‘creating educational spaces that defy the hegemonic society’ (Gilmore, Citation2003, p. 11). Put simply, the ability to thrive, despite or in opposition to adverse circumstances, is what defines resilience and distances it from vulnerability. Our emphasis on the dual yet intertwined nature of vulnerability/resilience is intentional for mobilising the dispositions necessary for socially just RfP. illustrates that knowledge, ideas and skills, which fall under actions and behaviours, are the FoK that are mutually interacting with FoI, which encompass geographical, practical, cultural, social and institutional tools and signs. Funds of Courage, with their core components of resilience and vulnerability, as two types of attitudes/dispositions, feed into and are influenced by both FoI and FoK, as illustrated with the two-edged arrow in .

Applying funds of courage to RfP practice

In this section we connect our conceptual discussion to some concrete examples in order to apply educational theories to practice, and thus partially respond to the gap between reading science and practice that serves to underscore social injustice (Gibbons, Citation2021). Our authorial exemplification of the theoretical Funds of Courage concept is intended to grasp the distinctiveness of it, and to provide a concrete basis for further discussions of teachers’ dispositions that advance socially-just RfP. Primarily, we seek to ensure that our argument and examples stimulate ideas for pedagogical practice, trigger dialogue and inspire other responses among educationalists. We include educational examples with both emergent readers and established readers, attending to reading journeys over the early and primary years.

During our storytelling and story-acting research with the Our Story app (an app co-developed by The Open University following Natalia Kucirkova's doctoral thesis), we interviewed three-to-six-year-old children about their experiences of a narrative intervention in their kindergartens (Hempel-Jorgensen et al., Citation2018). The project was part of an evaluation study concerning the impact of the Helicopter Technique in local pre-schools in the UK. This research specifically focused on children involved in storytelling and story-acting exercises, seeking to understand the effects and implications of this technique on their learning processes. From our researchers’ perspective, the participating children were vulnerable in that they lacked ways to convey their opinions to adults in a manner that would fully honour their voices. They were also resilient in that they were proficient in the use of the latest technologies such as multimedia tablet apps. This sparked a rich portfolio of responses from the children and fed into attitudes and dispositions that demonstrated Funds of Courage. Some children created stories based on photos provided by us, others created new stories, interweaving their experiences into these digital tales. Their narratives comprised an authentic response to their lived experience of Gussin V. Paley’s (Citation1980, Citation2004) story-based curriculum, and opened up the space for conversations between the adult researchers and child participants. The use of the app helped us discern in more depth and detail children’s individual experiences. It also enabled us to shift our co-researchers’ perspectives, as the children came to view story-making apps as sources of authentic RfP encounters (Cremin, Citation2019).

Another example of how Funds of Courage play out in practice is that of the RfP research and practice community at the Open University institution. Working with educators, we have co-created a professional research and practice digital space (https://ourfp.org/) , which shares the findings of several relevant RfP studies and hundreds of published examples of teachers’ evidence-informed practice. The work, undertaken by sustained collaboration between researchers and practitioners, moves from ‘routinised’ and formulaic classroom based RfP, to encompass more authentic ways of involving children, parents and teachers (e.g. through the use of QR Codes, and on-line Reading Treasure Hunts connecting children’s home and school learning during the pandemic and since). The RfP community members share their expertise, with some examples tapping into potentially vulnerable contexts (e.g. examples of children’s attitudinal surveys and staff text knowledge audits), and to resilience (e.g. videoed interviews with teachers sharing culturally responsive pedagogic strategies that have positively impacted on children’s volitional reading). The community space demonstrates that many educators have shifted their perspectives in relation to RfP and embraced it as an opportunity to expand their own identities as readers and widen their knowledge of children’s reader identities. Over 100 teacher groups led by volunteers across the UK and trained by The Open University staff meet annually to engage in year-long professional development to support both their own and young people’s pleasure in reading. The digital site provides them with a communal space to showcase their resilience, offering genuine accounts of their experiences which portray the diversity of knowledge and identities that lie at the heart of authentic volitional reading encounters.

With increased professional knowledge, dialogue about what counts as reading, and new understandings of children’s reader identities, teachers’ own understanding and identities can develop in a less school-centric manner. In the original project, years before, teachers were also positioned as readers and invited to reflect on their own reading practices and identities (Cremin et al., Citation2014). We saw how these metacognitively aware readers began to share their habits, preferences and diverse literacy practices, and exchange recommendations for texts and websites that helped build their own reading repertoires. Parents and family members were also included in this process and become part of professional (and personal) conversations about the myriad texts that they and their children read as part of everyday life (Cremin et al., Citation2015). Such reciprocal reader relationships can nurture new communities and help shape more positive reader identities, encouraging RfP.

By adopting the Funds of Courage dispositions, individuals can generate resources and artefacts at times of crisis and initiate ripple effects in communities. An example of this is the Ukrainian digital library that our team co-created with international partners (StoryWeaver), volunteer teachers and translators. The digital library was created at the outset of the Russian invasion in February 2022 and has grown since into hundreds of high-quality Ukrainian children’s stories. The stories were authored, translated and remixed, in texts, visuals and audio narrations, by teachers, educational professionals and researchers across the globe to support Ukrainian families (see https://www.childrensdigitalbooks.com/ukrainian/). The digital library is just one of many instances of what can be achieved when Funds of Courage are capitalised upon in adverse situations.

Conclusion

Today, more than ever, educators need support to meet young learners where they are, and to adjust their pedagogies in response to their students’ knowledge and identities as readers. This behoves teachers not only to draw on their knowledge and identities as digitally agile, knowledge-strong pedagogues, but also on their dispositions to engage children as learners despite ongoing challenges. The FoK and FoI work is a powerful source of inspiration for educational professionals in Anglo-American countries seeking to eschew the deficit models of learners and learning inherent in the national English and US curricula. More broadly, vulnerability is often used to connote deficit, which, paradoxically, assigns more power to extant dominant groups (Butler et al., Citation2016). In an effort to overcome simplistic understandings of vulnerability and to expand the concept, we propose the novel concept of Funds of Courage, and name and advance the individual and social dispositions that are sites of possible social-justice transformation.

Adding to the ‘tools’ or different methodological approaches used by FoK researchers (e.g. Comber & Kamler, Citation2004; Hill & Wood, Citation2019; Mills et al., Citation2019), we have exemplified social-justice pedagogy around the FoK approach by, for example, inviting children to narrate their own stories with digital apps (Kucirkova, Citation2019) and involving teachers in researching children’s everyday literacy lives (Cremin et al., Citation2015). Our examples highlight the temporal dimension in the FoK, FoI and Funds of Courage approaches. Funds of Knowledge exhibit a relatively static nature as they pertain to the systemic levels in which children are situated, whereas Funds of Identity are dynamic and responsive to an individual’s specific life stage. Funds of Courage, by contrast, encompass dispositions that remain dormant within individuals and become activated to varying extents in response to need and in times of emergency. The Ukrainian children’s digital library exemplifies how Funds of Courage can be effectively mobilised for the benefit of the community that lasts beyond a crisis, however challenging.

The unique contribution of our paper lies in demonstrating the ways in which the psychological dispositions of courage, vulnerability and resilience underlie FoK and FoI. These Funds of Courage significantly and innovatively expand limited models of young people’s RfP, and can transform ‘students’ diversities into pedagogical assets’ (Moll et al., Citation2006, p. 85), as they are sensitive to the changing nature of reading and childhood and move from routinised RfP to personally, socially and culturally responsive RfP pedagogies. We recommend that future research studies acknowledge the interrelationship between vulnerability and resilience in shifting perspectives on RfP, enabling teachers’ dispositions to support socially just reading for pleasure practices.

Acknowledgment

We would like to respectfully acknowledge the passing of Professor Luis Moll, whose pioneering work and profound insights into the concept of Funds of Knowledge have significantly influenced our research and the broader academic community. His legacy continues to inspire and shape our understanding of educational practices and the importance of cultural knowledge in learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akkerman, S. F., & Meijer, P. C. (2011). A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teaching & Teacher Education, 27(2), 308–319.

- Ashbridge, C., Clarke, M., Bell, B. T., Sauntson, H., & Walker, E. (2022). Democratic citizenship, critical literacy and educational policy in England: A conceptual paradox? Cambridge Journal of Education, 52(3), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2021.1977781

- Aukerman, M., & Chambers Schuldt, L. (2021). What matters most? Toward a robust and socially just science of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S85–S103. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.406

- Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

- Beach, S. A., Nyirumbe, S. R., Monk, D., Pia Okecha, S. E., & Callow, J. (2020). Decolonizing beginning literacy instruction: Views from Ugandan teachers. The Reading Teacher, 74(2), 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1937

- Black, L., Choudry, S., Howker, E., Phillips, R., Swanson, D., & Williams, J. (2021). Realigning funds of identity with struggle against capital: The contradictory unity of use and exchange value in cultural fields. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 28(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2021.1908364

- Bradbury, A. (2019). Datafied at four: The role of data in the ‘schoolification’of early childhood education in England. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1511577

- Brown, B. (2006). Shame resilience theory: A grounded theory study on women and shame. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 87(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3483

- Burnett, C., & Merchant, G. (2020). Undoing the digital: Sociomaterialism and literacy education. Routledge.

- Burnett, C., Merchant, G., Pahl, K., & Rowsell, J. (2014). The (im) materiality of literacy: The significance of subjectivity to new literacies research. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 35(1), 90–103.

- Butler, J., Gambetti, Z., & Sabsay, L. (Eds.). (2016). Vulnerability in resistance. Duke University Press.

- Capeheart, L., & Milovanovic, D. (2020). Social justice: Theories, issues, and movements (Revised and Expanded ed.). Rutgers University Press.

- Centre for Literacy in Primary Education. (2023). Reflecting realities: Survey of ethnic representation in UK Children’s Literature 2022. https://clpe.org.uk/research/clpe-reflecting-realities-survey-ethnic-representation-within-uk-childrens-literature-1

- Cheema, J. R. (2018). Adolescents’ enjoyment of reading as a predictor of reading achievement: New evidence from a cross-country survey. Journal of Research in Reading, 41(S1), S149–S162. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12257

- Coiro, J., Knobel, M., Lankshear, C., & Leu, D. (2008). Central issues in new literacies and new literacies research. In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. Leu (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 25–32). Erlbaum.

- Cole, M., & Engeström, Y. (1993). A cultural-historical approach to distributed cognition. Distributed Cognitions: Psychological and Educational Considerations, 1–46.

- Comber, B., & Kamler, B. (2004). Getting out of deficit: Pedagogies of reconnection. Teaching Education, 15(3), 293–310.

- Cox, K. E., & Guthrie, J. T. (2001). Motivational and cognitive contributions to students’ amount of reading. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1044

- Cremin, T. (2007). Revisiting reading for pleasure: diversity, delight and desire. In K. Goouch & A. Lambirth (Eds.), Understanding Phonics and the Teaching of Reading (pp. 166–190). Berkshire: McGraw Hill.

- Cremin, T. (2015). Perspectives on creative pedagogy: Exploring challenges, possibilities and potential. Education, 43(4), 353–359.

- Cremin, T. (2019). The personal in the professional in S. Ogier and T. In Eaude (pp. 259–270). London: The Broad and Balanced Curriculum, The Broad and Balanced Curriculum.

- Cremin, T., Mottram, M. P., S, C. R., & Safford, K. (2014). Building communities of engaged readers: Reading for pleasure. Routledge.

- Crisp, T., Knezek, S. M., Quinn, M., Bingham, G. E., Girardeau, K., & Starks, F. (2016). What’s on our bookshelves? The diversity of children’s literature in early childhood classroom libraries. Journal of Children’s Literature, 42(2), 29.

- Day, C., Kington, A., Stobart, G., & Sammons, P. (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: Stable and unstable identities. British Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920600775316

- Esteban-Guitart, M. (2021). Advancing the funds of identity theory: A critical and unfinished dialogue. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 28(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2021.1913751

- Esteban-Guitart, M., & Moll, L. C. (2014). Funds of identity: A new concept based on the funds of knowledge approach. Culture & Psychology, 20(1), 31–48.

- Flippo, R. F. (Ed.). (2012). Reading researchers in search of common ground: The expert study revisited. Routledge.

- García, O., & Kleifgen, J. A. (2020). Translanguaging and literacies. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(4), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.286

- Gibbons, K. (2021, January 15). Literacy as a social justice issue. Illuminate Education. https://www.illuminateed.com/blog/2021/01/literacy-as-a-social-justice-issue/

- Gilbert, E. (2016). Big magic: Creative living beyond fear. Penguin.

- Gilleece, L., & Eivers, E. (2018). Characteristics associated with paper-based and online reading in Ireland: Findings from PIRLS and ePIRLS 2016. International Journal of Educational Research. Pergamon, 91, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJER.2018.07.004

- Gilmore, P. (2003). Privilege, privation, and the ethnography of literacy. Language Arts, 81(1), 10–11. https://doi.org/10.58680/la20032865

- González, N. (2005). Beyond culture: The hybridity of funds of knowledge. In N. Gonzalez, L. C. Moll, & C. Amanti (Eds.), Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms (pp. 29–46). Lawrence Publishing.

- González, N., Wyman, L., & O’Connor, B. H. (2011). The past, present, and future of “funds of knowledge”. A Companion to the Anthropology of Education, 479–494.

- Harmey, S., & Moss, G. (2020). Learning loss versus learning disruption: Written evidence submitted by the international literacy centre. To the education select committee inquiry into the impact of COVID-19. UCL, Institute of Education. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/12497/pdf

- Harmey, S., & Moss, G. (2023). Learning disruption or learning loss: Using evidence from unplanned closures to inform returning to school after COVID-19. Educational Review, 75(4), 637–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1966389

- Hebbecker, K., Förster, N., & Souvignier, E. (2019). Reciprocal effects between reading achievement and intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation. Scientific Studies of Reading, 23(5), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2019.1598413

- Hempel-Jorgensen, A., Cremin, T., Harris, D., & Chamberlain, L. (2018). Pedagogy for reading for pleasure in low socio-economic primary schools: Beyond ‘pedagogy of poverty’? Literacy, 52(2), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12157

- Hill, M., & Wood, E. (2019). ‘Dead forever’: An ethnographic study of young children’s interests, funds of knowledge and working theories in free play. Learning, Culture & Social Interaction, 23, 100292.

- Hobbs, R. (2020). Propaganda in an age of algorithmic personalization: Expanding literacy research and practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(3), 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.301

- Hogg, L. (2011). Funds of knowledge: An investigation of coherence within the literature. Teaching & Teacher Education, 27(3), 666–677.

- Hogg, L., & Volman, M. (2020). A synthesis of funds of identity research: Purposes, tools, pedagogical approaches, and outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 90(6), 862–895. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320964205

- Jerrim, J., & Moss, G. (2019). The link between fiction and teenagers’ reading skills. International evidence from the OECD PISA study. British Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 181–200.

- Kirkland, D. E. (2014). “They look scared”: Moving from service learning to learning to serve in teacher education—a social justice perspective. Equity & Excellence in Education, 47(4), 580–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2014.958967

- Kucirkova, N. (2019). Children’s agency by design: Design parameters for personalization in story-making apps. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 21, 112–120.

- Larson, J., & Marsh, J. (2014). Making literacy real: Theories and practices for learning and teaching. Sage.

- Lindorff, A., Stiff, J., & Kayton, H. (2023). PIRLS 2021: National Report for England Research Report. Department for Education. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pirls-2021-reading-literacy-performance-in-england,

- Llopart, M., & Esteban-Guitart, M. (2018). Funds of knowledge in 21st century societies: Inclusive educational practices for under-represented students. A literature review. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1247913

- Locher, F. M., Becker, S., & Pfost, M. (2019). The relation between students’ intrinsic reading motivation and book reading in recreational and school contexts. American Educational Research Association Open, 5(2).

- McLay, K. F., & Renshaw, P. D. (2020). Making ‘us’ visible: Using membership categorisation analysis to explore young people’s accomplishment of collective identity‐in‐interaction in relation to digital technology. British Educational Research Journal, 46(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3565

- McQuillan, J. (2019). Where do we get our academic vocabulary? Comparing the efficiency of direct instruction and free voluntary reading. The Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal, 19(1), 129–138.

- Mills, K., Bonsignore, E., Clegg, T., Ahn, J., Yip, J., Pauw, D., Cabrera, L., Hernly, K., & Pitt, C. (2019). Connecting children’s scientific funds of knowledge shared on social media to science concepts. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 21, 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2019.04.003

- Miyamoto, A., Pfost, M., & Artelt, C. (2018). Reciprocal relations between intrinsic reading motivation and reading competence: A comparison between native and immigrant students in Germany. Journal of Research in Reading, 41(1), 176–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12113

- Moje, E. B., & Luke, A. (2009). Literacy and identity: Examining the metaphors in history and contemporary research. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(4), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.44.4.7

- Moje, E., Luke, A., Davies, B., & Street, B. (2009). Literacy and identity: Examining the metaphors in history and contemporary research. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(4), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.44.4.7

- Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (2006). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. (pp. 71–87). Routledge.

- Moll, L. C. (Ed.). (1992). Vygotsky and Education: Instructional implications and applications of sociohistorical psychology. Cambridge University Press.

- Moll, L. C., Soto-Santiago, S. L., & Schwartz, L. (2013). Funds of knowledge in changing communities. International Handbook of Research on children’s Literacy, Learning, and Culture, 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118323342.ch13

- Morgan, W. (1997). Critical literacy in the classroom: The art of the possible. Psychology Press.

- Moro, M. R. (2014). Parenthood in migration: How to face vulnerability. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 38(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-014-9358-y

- Nell, V. (1988). Lost in a book: The psychology of reading for pleasure. Yale University Press.

- Neuman, S., & Moland, N. (2016). Book deserts: The consequences of income segregation on children’s access to print. Urban education. 54(1), 126–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916654525

- OECD. (2020). Reading for change: Performance and engagement across countries: Results from PISA 2000 (Publication No. ED474915). US Government Printing Office

- Orellana, M. F. (2009). Translating childhoods: Immigrant youth, language, and culture. Rutgers University Press.

- Oughton, H. (2010). Funds of knowledge—A conceptual critique. Studies in the Education of Adults, 42(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2010.11661589

- Paley, V. (1980). Wally’s Stories. Harvard University Press.

- Paley, V. G. (2004). A child’s work: The importance of fantasy play. University of Chicago Press.

- Patel, J. A., Nielsen, F. B. H., Badiani, A. A., Assi, S., Unadkat, V. A., Patel, B., Ravindrane, R., & Wardle, H. (2020). Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: The forgotten vulnerable. Public Health, 183, 110–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006

- Poole, A. (2020). Re-theorising the funds of identity concept from the perspective of subjectivity. Culture & Psychology, 26(3), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X19839070

- Roberts‐Holmes, G., & Bradbury, A. (2016). Governance, accountability and the datafication of early years education in England. British Educational Research Journal, 42(4), 600–613. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3221

- Rose, J. (2017). “Never enough hours in the day”: Employed mothers’ perceptions of time pressure. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 52(2), 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.2

- Rundell, K. (2019). Why you should read children’s books, even though you are so old and wise. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Ryan, M., & Barton, G. (2014). The spatialized practices of teaching writing in elementary schools: Diverse students shaping discoursal selves. Research in the Teaching of English, 48(3), 303–328.

- Sarland, C. (1995). Versions of Literacy? Re‐thinking reading research. Cambridge Journal of Education, 25(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764950250207

- Saubich, X., & Guitart, M. E. (2011). Bringing funds of family knowledge to school. The living Morocco project. REMIE: Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 1(1), 79–103.

- Scarre, G. (2010). On courage. Routledge.

- Scholes, L. (2023). Reading for digital futures: A lens to consider social justice issues in student literacy experiences in the digital age. Cambridge Journal of Education, 54(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2023.2281695

- Scholes, L., Spina, N., & Comber, B. (2020). Socioeconomic status, mental wellbeing and transition to secondary school: Analysis of the School Health Research Network/Health Behaviour in School-aged Children survey in Wales. British Educational Research Journal, 46(5), 1111–1130. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3616

- Schugar, H., & Dreher, M. (2017). U. S. Fourth Graders’ Informational Text Comprehension: Indicators from NAEP International Electronic. Journal of Elementary Education, 9(3), 523–552.

- Schutte, N., & Malouff, J. M. (2006). Why we read and how reading transforms us: The psychology of engagement with text. The Edwin Mellen Press.

- Schwartz, S. J. (2001). The evolution of Eriksonian and, neo-Eriksonian identity theory and research: A review and integration. Identity an International Journal of Theory and Research, 1(1), 7–58. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532706XSCHWARTZ

- Sharples, M. (2023). Towards social generative AI for education: Theory, practices and ethics. Learning: Research and Practice, 9(2), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2023.2261131

- Sheather, J. (2022). As Russian troops cross into Ukraine, we need to remind ourselves of the impact of war on health. British Medical Journal, 376, 376–499 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o499

- Short, K. G. (2018). What’s trending in children’s literature and why it matters. Language Arts, 95(5), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.58680/la201829584

- Smith, J. K., Smith, L. F., Gilmore, A., & Jameson, M. (2012). Students’ self-perception of reading ability, enjoyment of reading and reading achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(2), 202–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.04.010

- Street, B. (2006). Autonomous and ideological models of literacy: Approaches from New Literacy Studies. Media Anthropology Network, 17, 1–15.

- Subero, D., Vujasinović, E., & Esteban-Guitart, M. (2017). Mobilising funds of identity in and out of school. Cambridge Journal of Education, 47(2), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2016.1148116

- Sullivan, A., & Brown, M. (2015). Reading for pleasure and progress in vocabulary and mathematics. British Educational Research Journal, 41(6), 971–991. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3180

- Sun, Y.-J., Sahakian, B. J., Langley, C., Yang, A., Jiang, Y., Jujiao, K., Zhao, X., Li, C., Cheng, W., & Fen, J. (2023). Early initiated childhood reading for pleasure: Associations with better cognitive performance, mental well-being and brain structure in young adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 1–15.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291723001381

- Tippett, K. (2016). Conversation with Kissling, Frances, the good in the other, the doubt in ourselves. On being becoming Wise Podcast, Transcript available from: https://onbeing.org/programs/good-doubt-frances-kissling/

- Troyer, M., Kim, J., Hale, E., Wantchekon, K. A., & Armstrong, C. (2019). Relations among intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation, reading amount, and comprehension: A conceptual replication. Reading & Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 32(5), 1197–1218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9907-9

- Williamson, B. (2021). Digital policy sociology: Software and science in data-intensive precision education. Critical Studies in Education, 62(3), 354–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1691030

- Zipin, L. (2009). Dark funds of knowledge, deep funds of pedagogy: Exploring boundaries between lifeworlds and schools. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 30(3), 317–331.