ABSTRACT

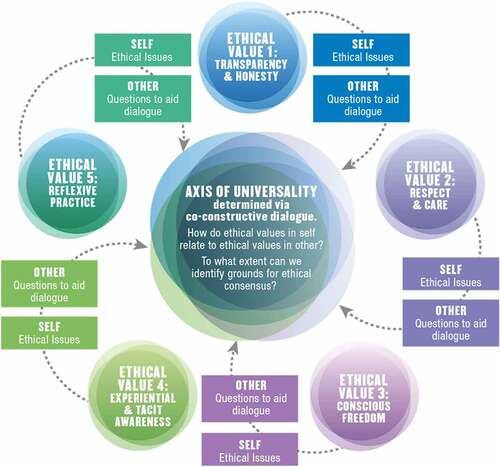

Research ethics in international and comparative education (ICE) highlights the diverse challenges that ICE researchers face in enacting ethical practice. In particular, the significant gaps between ethics presented in Western ethical guidelines and international fieldwork. Through analysis of existing guidelines and questionnaire responses from 46 BAICE members, this article demonstrates that more ethical guidance is needed to support ICE researchers. A new framework is put forward centred on five core ethical values – transparency and honesty, respect and care, conscious freedom, experiential and tacit awareness and reflexive practice – situated on an axis of universality and enacted through co-constructive dialogue. This extends the theory of relational ethics as a contemporary approach to ethics. In the context of ICE, it is hoped that this framework will provide guidance for researchers to navigate ethics in a global world, in which we find ourselves universally bound to divergence and change.

Introduction

This article puts forward a dialogic, values-based framework for working through ethical issues encountered in international and comparative education (ICE) research. These issues – related to consent, harm, respect, and transparency – are not restricted to ICE, but can be heightened in the international and collaborative contexts that ICE researchers work. The framework offers a set of five overlapping values – transparency and honesty, respect and care, conscious freedom, experiential and tacit awareness and reflexive practice. These values are located on an axis to denote the myriad of ways in which they might change according to context. For example, what we say we do and what we actually do are not necessarily the same. This propensity for variation can be observed through a process of dialogue, which the framework invokes via ethical questions not ethical codes. The framework has been developed in response to the growing recognition that educational researchers working in cross-cultural settings need further support in negotiating research ethics (Robinson-Pant and Singal Citation2013a) and that ‘codes are not enough’ (Small Citation2002, 387). This sentiment was clearly shared by participants in the British Association for International and Comparative Education (BAICE) 2015 forum ‘Research ethics in international and comparative education’ and related symposia at the 2014 and 2018 BAICE conferences.

The framework has been developed from thematic analysis of responses to an open-ended questionnaire sent to all BAICE members, (see Appendix 1). Thematic analysis revealed significant challenges related to ethics and some clear values that underpin work in the field. What emerges from this analysis is that ICE researchers want practical support in how to enact perceived universal ethics in culturally sensitive ways. In this article, following a review of the relevant literature and overview of the research methodology, we present research findings related to two key research questions: (1) What ethical guidelines do BAICE members currently use and how applicable do they find them to the work they do? and (2) What are the key ethical values that underpin BAICE members’ research? We then present the proposed framework based on the values identified.

Literature review

Despite the prominence of ethical debates in educational research (see Simons and Usher Citation2012; David, Edwards, and Alldred Citation2001; Small Citation2002; Harcourt, Perry, and Waller Citation2011; Parsons et al. Citation2015), there has been relatively little attention paid to such debates within the field of ICE (Robinson-Pant and Singal Citation2013a; Tikly and Bond Citation2013). This is particularly concerning when we consider the long-established literature on researching across cultures, the colonial legacy of ICE and the associated issues of power and inequality which continue to define much of the research in the field (Tikly and Bond Citation2013; Takayama, Sriprakash, and Connell Citation2017).

A 2013 special issue of this journal (Robinson-Pant and Singal, Citation2013a) highlighted the challenges in conforming to mandatory ethical procedures in Western universities when conducting research in cross-cultural settings. This was supported by research conducted by McMahon (Citation2018) which showed that there is limited attention paid to cross-cultural issues in existing guidelines that are used by educational researchers. For example, content analysis of ten guidelines, including the 2011 British Educational Research Association (BERA) guidelines, showed no mention of ‘comparative,’ ‘cross-cultural’ or ‘universal’ and limited mention of context.Footnote1

It has also been widely noted that ethics in Western universities tend to focus on ‘ethical clearance’ at the start of a research project which can lead to a ‘bolt-on view of research ethics’ (Robinson-Pant Citation2005, 95–96). Here, universal ethical guidelines are critiqued on the basis that exponents believe they are acting ethically when they are simply conducting ‘a function of the application of ethical codes and principles of practice’ (Simons and Usher Citation2012, 10). Halse and Honey (Citation2007, 336) convincingly argue that the discourse of such ethical codes constitutes a ‘regime of truth’ that is often dissonant with what they view as ethical research practice.

This ‘regime of truth’ can be seen to reflect a Kantian deontological ethics which has underpinned much of Western moral-political thought and is reflective of the biomedical origin of the ethical regulations in research across the social sciences (see Robinson-Pant and Singal, Citation2013b). As Kvale (Citation1996, 121) explains, this approach promotes universal and normative principles that should not be broken and ‘carried to its extreme, the intentional position can become a moral absolutism with intentions of living up to absolute principles of right action, regardless of the human consequences of an act.’ Hammersley (Citation2015) highlights how the 2012 UK Economic and Social Research Council’s framework of research ethics has six principles that broadly frame how researchers ‘should’ or ‘should not’ act. In the field of ICE, what is particularly problematic is that ethical guidelines underpinned by such principles can be seen to be developed within a Western normative framework that suits Western Universities and their associated cultural norms (Robinson-Pant Citation2005; Stake and Rivzi Citation2009).

There are clear challenges here for researchers when they enter the field of ICE, particularly so for early career researchers who may be relatively inexperienced undertaking fieldwork in cross-cultural settings. Researchers have explored these tensions in relation to language, negotiating access with gatekeepers at national and local levels, informed consent, and methods of data collection such as recording devices (Robinson-Pant Citation2005; Dwyer Citation2006; Heller et al. Citation2011; Lunn Citation2014). Authors such as Silverman (Citation2000, Citation2017) and Milligan (Citation2016) have also highlighted how such discussions of ethical practice in the field need to be contextualised within the power dynamics at play both in the production and use of knowledge gained through research.

Other authors take this further by emphasising the incompatibility of Western research ethics with the ethics of non-Western contexts, such as indigenous and Confucian ethical traditions (Smith Citation2006; Zhang, Chan, and Kenway Citation2015). Smith (Citation2006) reveals how Western ethical procedures value individualism and the privileging of individual rights and decision-making which directly contrasts with community-based values of Maori society where more collective and community-oriented strategies are seen to be appropriate (see also Smith, Tuck, and Yang Citation2018). Similar critiques of the assumption of individual responsibility can be seen among the Ubuntu philosophy literature (Metz and Gaie Citation2010). The term Ubuntu loosely translating into English as ‘humanness, or being human’ (Khoza Citation2006, 6) is a Southern Africa philosophy of the interconnectedness of life through reciprocal relationships. In this way, action is guided by the balance of relational bonds which recognise flux as the energy driving all phenomena: ‘I value my relationship with my family in the same manner I value the trees, waters, rocks, and other animals’ (Mucina Citation2013). In contrast, Western ethical procedures which value individualism as the privileging of individual rights and decision-making, do not fully integrate the social reality of the individual. A key tenant of this assumption might be the framing of individual existence and existence for others as divorced from one another, which is in fact counter to what Ubuntu philosophy exposes: ‘Under Ubuntu there is an individual existence of the self and the simultaneous existence for others,’ (Luthans, Van Wyk, and Walumbwa: Citation2004, 515). From this perspective, communality is not at the expense of individuality – they do not deny one another but rather: they find one another.

In response to the critiques of universal deontological ethics, alternative and more contextualised approaches to ethics have been promoted in educational and social research (e.g. Tikly and Bond Citation2013). These reflect a consequentialist ethics where the emphasis is on good practice and moral behaviour. The act of being ethical is judged by the consequences of your actions rather than how you adhere to a particular set of rules (Stutchbury and Fox Citation2009). Similarly, a situated ethics approach (Simons and Usher Citation2012) views ethics relatively and ‘mediated within different research practices.’ De Laine (Citation2000, 3) has argued that dominant ethical codes and practices need to be adapted to the particular research context:

The researcher needs some understanding of how to use the code together with other resources to make a decision that is more ‘right.’ The individual’s intentions, motivations, and ways of cognitively structuring the ethically sensitive situation are equally important to ethical and moral practice as are conforming to or violating an ethical code.

This can be seen as a more contextualised and complex interpretation of ethics in practice. However, it is important to note that De Laine’s articulation of being ‘ethically mindful,’ confers the locus of control to the individual in building ethical self-awareness, without extending an awareness of the self in relation to other. Nonetheless, what is important in De Laine’s argument is the recognition of the need to find an ethical space between procedural and practical ethics; something that has also been put forward by other researchers (Guillemin and Gillam Citation2004; Stutchbury and Fox Citation2009; Tikly and Bond Citation2013) in order to connect the dichotomies of universal-relative ethics.

Methodology

The data presented in this article were collected and analysed within a predominantly qualitative research design, undertaken in 2017. The research aimed to answer these two research questions:

What ethical guidelines do BAICE members currently use and how applicable do they find them to the work they do?

What are the key ethical values that underpin BAICE members’ research?

To answer these questions, a questionnaire was designed and sent to all BAICE members. BAICE members were also asked to share the questionnaire within their networks. The overall size of the BAICE membership is 301, with the majority of members based in the UK. There were 46 respondents of which 35 were BAICE members and 11 were non-BAICE members. All member types were represented (postgraduate researchers – 17; permanent university staff – 19; contract researcher – 4; practitioner/contractor – 3; retired – 3) and direct quotes are attributed to these subgroups using a participant code. Postgraduate researchers (PR) include doctoral and masters level students, permanent university staff (PU) refers to those on permanent contracts, contract university researchers (CR) represent those employed on specific research projects including postdoctoral researchers, practitioner/contractors (PC) refer to ICE researchers not employed at higher education institutions, and (R) denotes retired members.

The majority of the questions were open-ended, and the responses were collated into a single qualitative data set. An inductive, thematic analysis was conducted on all textural data from the questionnaire (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 81–83). Both semantic and latent codes were developed from the material to answer the two research questions. While the values and questions came from our interrogation of the dataset, they are influenced by our experience within UK institutions, positioning and this dialogue.

The themes were clustered together to articulate distinct domains, which resulted in the deletion of infrequent and/or repetitive themes. These domains were given an overall category (theme) and subcategory (sub theme) which encapsulated the relationship between different aspects of the same domain. The following themes capture the issues which respondents emphasised more frequently (10 > counts); ‘Ethical guidelines provide professional UK standards,’ ‘Ethical guidelines as non-representative of non-western cultures,’ ‘Insider/Outsider relationship as an important ethical consideration,’ ‘Power Differentials’ and ‘Research context in need of protection.’ Interestingly, the themes which were reported less by respondents included the particularly challenging issues around dialogue and the need to situate ethics to contextual factors. These themes each scored the lower range of frequency (5 counts), yet when viewed together they articulate a substantial frequency (20 counts) of varied yet interconnected issues; ‘Value of Dialogue,’ ‘Meaningful dialogue is challenging,’ ‘Assumptions about the universal application of western values’ and ‘Importance of Situated Ethics.’ These issues encompassed contradictory and problematic experiences of dialogue and situated ethics, which the following sub themes illustrate: ‘Normative values around education & ethical procedures shaped by local context,’ ‘Develop principles cross-culturally with stakeholders.’ Situated ethics and dialogue emerge as both valuable and challenging themes, cutting through seemingly disparate issues in ways that are unclear and often in conjecture. These findings informed the overall framework, which conceptualises dialogue and situated ethics in tandem, in ways that are more explicit and focused.

In the following section, we present the main findings from our analysis of the questionnaire responses, from 46 respondents. It is important to note that this sample consists of researchers who are mainly based at institutions within the UK. The responses also only reflect those who willingly responded to the questionnaire request and so data may be skewed to those who have more concerns or interest in ethics. Therefore, the applicability of the framework in different contexts will need further examination. There is a recognised limitation in that the study focuses exclusively on researchers and so the voices of research participants are absent. This is something that we hope to address in future research.

Findings

In this section, we present the main findings from the thematic analysis based on the two research questions.

What ethical guidelines do BAICE members currently use and how applicable do they find them to the work they do?

BAICE members report using a combination of sources to guide them in making ethical decisions regarding research. Respondents were asked to indicate all of the sources that they may use, and illustrates these and their reported usage.

Table 1. Types and usage of ethical guidance used by BAICE members.

When asked how useful researchers found this range of guidance less than half of the 46 respondents reported that it was useful (20% very useful and 28% useful). Although interpretations of ‘useful’ may have differed among the respondent group, it is an important finding that despite researchers drawing on a range of different sources for ethical guidance, many do not feel fully supported in the practice of research ethics within ICE. This is perhaps not surprising when we consider this together with the findings of the content analysis of existing guidelines discussed above.

Across the responses, it is clear that existing university and association (e.g., the 2011 BERA) guidelines provide a useful starting point for the consideration of ethics. For example, existing guidelines ‘provide most answers to my research requirements’ (PR25), are important because they offer ‘predetermined boundaries in place before any research begins’ (PR1) and provide ‘clear guidance on what should or should not be done’ (PU30). For others, their use is more utilitarian as a requirement for ethical approval – ‘useful in the sense that reference to these documents is required’ (CR3). What is clear is that guidelines are more commonly used at the outset of research studies, when obtaining ethical approval, rather than a reference point throughout the research process. For some, it means that ethical practice is subsumed into ‘another “tick the box”/“stick to the rules” activity,’ (PR35) echoing many of the concerns raised in the literature (Robinson-Pant Citation2005).

This approach focuses on compliance, which ‘seems to expect the worst possible consequences’ (PU18) and was seen by some to reflect Western normative values and formed one of the main critiques of the existing guidelines. In particular, permanent staff stated that they ‘do not deal critically with cross-national, cross-cultural ethical issues’ (PU19) and that ‘the assumptions of the guidelines are for work conducted in the UK and inevitably this leads to the need for further explanatory information’ (PU6). This can contribute to power imbalances when there are not country-specific guidelines: ‘in the absence of many local guidelines, it also becomes difficult to draw comparisons to an international standard like the ESRC/BERA’ (PR25).

Interestingly, it became clear that dialogue emerged as the most important source of support, including the practice of dialogue with self as this can support the interrogation of personal values and inherent biases. For example, the inductive thematic analysis of data derived ‘value of dialogue’ as a key theme. This encapsulated several sub themes which expressed dialogue with a wide range of stakeholders including peers, research partners and participants: ‘Our institutional review process requires a conversation with a colleague, and this is fabulously useful’ (PU4) and ‘Importance of negotiating a shared set of ethical principles with local partners and participants,’ (PU23). UK external evaluators were also cited in relation to dialogue: ‘Often the ethics committee at my university make suggestions and offer considerations that I hadn’t previously thought of’ (R38).

However, the instigation of dialogue does not always guarantee its success; ‘The challenge of working with children and young people, roles of Southern partners in research process’ (PU19). Finding a common language between local and national governance is challenging and participants are not always accustomed to having a voice. This developed into a further theme: ‘Meaningful dialogue is challenging,’ which articulated the barriers associated with implementing dialogue in the research process.

However, when it is meaningful, dialogue has the potential to scaffold a more shared approach to enacting ethical practice; ‘Future guidelines should value collectivist cultures,’ (CR3) where researchers coproduce knowledge in international teams; ‘Benefit from the expertise of international researchers (published and otherwise) who have researched in the context you intend to research’ (PU7). Respondent PU30 noted that discussion can lead to ‘shared understanding of what is meant by core concepts such as “do no harm,” professional misconduct and responses to child safeguarding’ (PU30). In this way, dialogue opened the door beyond existing ethical procedures and enabled the co-production of a novel language that might come closer to capturing the research context; ‘Redefining how we consider ethical issues within a global context’ (PR8).

What are the key ethical values that underpin BAICE members’ research?

Thematic analysis across the responses led to the identification of five key values, alongside that of dialogue discussed above, that shape respondents’ ethical practice in ICE research. The first value transparency and honesty (Counts: 19) captures the importance of transparency and honesty between researchers and participants about the research purpose, aims and potential impact. For example, the problem of competing roles in local & national governance, the imbalance of reciprocity and the legacy of colonialism in ICE practice were reported widely. This was viewed as a threat to the value of trust and transparency, which respondents emphasised as integral to ethical practice. For instance, trust was voiced as establishing relationships in research settings to ensure participants and the wider community fully understand the purpose of the research. The value of trust could be traced to problems which emerged through a lack of transparency: ‘… challenges as a result of the mismatch between some research participants and researchers about what the research is about and the likely impact of that research’ (CR31).

The second value, respect and care, (26 counts) highlights the importance felt across respondent types that ICE researchers need to respect cultural differences, be flexible to many research approaches and practices (particularly within vulnerable communities) and maintain a duty of care towards researchers and participants. For example, one researcher expressed how ‘maintaining the safety, protection and wellbeing of your participants and yourself as a researcher,’ (PR22) was not adequately expressed in existing guidelines. Other researchers pointed to the issue of gaining access in appropriate ways. Here, existing guidelines were critiqued for being ‘fixed’ and ‘assuming specific gatekeepers and effective authorities’ (PC27).

In this way, respect and care extends to the value of effective communication which requires active listening and congruence between intentions and actions. The value of care evolved from voices in the field expressing the need for specific research contexts to receive protection. This was articulated in terms of protecting participants subject to harm and at risk of sanctions from governance. The emerging picture was the value of care to participants on part of the researcher and that this was viewed as a professional duty.

The third value conscious freedom (41 counts) emerged from examples of competing rights across research participants and differences between individualist and collectivist cultures regarding consent. The issues of power differentials were widely noted with some fearing that people can feel obliged to participate in the research and less able to withdraw freely, as this would let the researcher or gatekeeper down. This illuminated the question: ‘How far can participants act freely?’ and the value of voicing the extent and limitation of freedom in self and other, in order to understand how they are related. The importance of this value can be understood as a process of bringing relational freedom into awareness, which we define as conscious freedom. It is important to note that researchers were also critical that individual consent/assent reflects Western good practice underlined by the value of individualism. This can be disruptive to contextual socio-cultural norms for example, that ‘speaking directly to students can be seen as challenging teacher leadership in the school,’ (PR39). These responses highlighted the need to consider conscious freedom alongside flexibility in practice.

Such flexibility in practice underpins the fourth value of experiential and tacit awareness, (26 counts). Respondents tended to use the example of consent to highlight this need for experiential awareness when faced with the tension of ‘rigid bureaucracy rather than realities’ (PU37). One postgraduate researcher highlighted how ‘completing consent forms’ can be ‘often misconstrued,’ (PR22) Another, showed how they:

Faced challenges to adapt the requirements to a context in India where the bulk of my fieldwork was conducted. For instance, to be able to get a signed acceptance from the participants according to the Ethics guidelines, but where local cultural requirements look down on a signed document, as a sign of mistrust (PR25).

The value of recognising unsaid (tacit) ethical issues, was linked to more widely reported values of trust which could be traced to problems which emerged through a lack of transparency. The value of experiential and tacit awareness in research contexts responds to the needs articulated by respondents to navigate contextual pressures experientially as well as logically. This approach was valued in respondents that expressed tacit ethical dimensions as only emerging during the research process and the often dynamic and emotional nature of many ICE contexts. The negative effects of applying a deontological ethical approach were also emphasised in that ethical guidelines can impact on rapport building with research participants. This can accumulate in unchecked tensions between partners, participants and researchers around negotiating clearance and data ownership.

The value of reflexive practice (18 counts) incorporated responses about individuals’ positioning and impact on the research process and the need to be open to and responsive to different cultural practices as a form of reflexivity. Respondents highlighted the need for UK-based researchers to consider their impact on ethical practice. For example, how the position of the visible outsider makes it difficult to guarantee anonymity, ‘the implications of the enhanced visibility of being a foreign researcher for the possibilities of confidentiality and anonymity’ (PU6).

Significantly, for some ICE researchers, reflexivity is linked to broader concerns about the need to decolonise the field of ICE, resonating with the critiques of Takayama, Sriprakash, and Connell (Citation2017). One researcher, for example, identified the need to unpack the ethics underlying how education is defined in the field, particularly ‘western-style schooling and all of its colonial baggage’ since ‘this reproduces systems of inequality in terms of who decides what valuable knowledge is’ (PR32). Furthermore, there were ethical concerns raised about the potential impact of research. This was voiced as a perceived imbalance between ‘what the researchers are likely to gain from the research rather than the research participants’ (CR31). This call to reflect on the field of ICE as a whole, highlights the significant role of dialogue across contexts and value sets, taking the concept of reflexivity beyond the individual to the discipline as a whole.

Discussion

It is evident from the findings that the BAICE community share concerns about the applicability of existing guidelines for the types of research that ICE researchers undertake. It is also clear that ICE researchers view ethics as something that goes beyond ontological and epistemological debates about knowledge and into the ethics of how and why research is conducted and how we manage its impact. Significantly, some shared values have emerged that underpin their research practice. Responses also suggest the importance of dialogue with ICE researchers valuing discussions in appropriate language (including not using jargon), with a range of different actors (including partners, colleagues, participants, supervisors, and other critical friends) and throughout the research cycle (not just in the initial phase of gaining ‘ethical clearance’).

This has led to the development of a suggestive framework with example guidance (see and accompanying ) that is intended to be used alongside, rather than in place of, the existing ethical guidelines that BAICE members cited using (see ). Since the framework has been developed based on the responses from researchers primarily at UK institutions, it is intended in the first instance to be used by researchers in this context. However, it is also hoped that the values and questions within the framework will be of use and adapted by researchers based at institutions around the world with varying degrees of different ethical rules and value sets (Stake and Rivzi, Citation2009).

Table 2. and accompanying Figure 1: Relational values in dialogue, a framework for ethical research in international and comparative education.

Table 3. and accompanying Figure 1: Relational values in dialogue, a framework for ethical research in international and comparative education.

Table 4. and accompanying Figure 1: Relational values in dialogue, a framework for ethical research in international and comparative education.

Table 5. and accompanying Figure 1: Relational values in dialogue, a framework for ethical research in international and comparative education.

Table 6. and accompanying Figure 1: Relational values in dialogue, a framework for ethical research in international and comparative education.

Figure 1. and accompanying : Relational values in dialogue, a framework for ethical research in international and comparative education.

The framework is based on the premise that the ‘universal-relative’ dichotomy requires space to co-exist and centres around an axis of universality. The framework accepts that there may be certain prescribed ethical requirements but that these can be viewed as in a state of flux rather than static entities. This sort of reflexive thinking is implicated in the axis which articulates the myriad of possible connections and disconnections between different ethical practices, enabling the interplay between value and context to be observed. The influence of context on ethical values was reported across all respondents. It was clear that a common challenge in navigating ethical practice in cross-cultural settings was the variability between self and other in (1) what is being valued and (2) how it is being enacted. For example, some researchers described honesty as monitoring how congruent researchers are in relating to stakeholders. Others focused on the importance of building trust and establishing relationships in research settings so that participants and the wider community fully understand the purpose of the research. Similarly, the experience of respect and care varied across contexts as a result of researchers communicating misinformation and/or raising expectations too high. For ethical value ‘conscious freedom’ respondents linked variability in enacting freedom to challenging contextual socio-cultural norms. For example, asking for young people’s assent to take part in a study requires speaking directly to students ‘… which can be seen as challenging teacher leadership in the school’ (PR39). The challenges associated with consent were particularly noted in situations where there are ‘local expectations often that permission given on participants’ behalf is sufficient’ (PU7). Respondents expressed the importance of experiential knowledge of context and the ability to tune into what’s being felt but not said: ‘What is considered to be unethical in the UK may not be considered unethical in another context and this can result in a delicate negotiation process’ (R16). Reflexivity was valued in data which described a responsive approach to research contexts. For example, gathering information on local cultural norms and rules and the utilisation of all available local channels (including local researchers).

The framework illustrates this inherent variability in cross-cultural ethics by juxtaposing the term ‘universality’ with ‘axis.’ This seeks to re-configure assumptions of cross-cultural applicability and re-affirm the relative nature of ethics. In this way, the framework responds to the oft-cited concerns in the questionnaire data that ‘simplistic impositions or application of standard ethical guidelines may be damaging or inappropriate in context’ (PU17) and the recommendations for ‘contextual modifications essentially pertinent to a setting’ (PU42).

Axis of universality is a key concept to the theoretical framework, which at its centre places ethics as relational. Relational as a term is concerned with the way in which two or more people or things are connected. The term axis describes a reference point in a structure, which other parts are connected. In this way, the term axis articulates ethics as relational, existing on a continuum of variability. For example, if we view values on an axis, then we are able to see them in connection with context and dialogue. The term axis derives from the Latin ‘axle, pivot’ which is useful here as it specifies a ‘turn’ or ‘rotation.’ This is how we depict values in our framework ( and accompanying ), which locates values as rotating around the point of co-constructive dialogue. This rotation is further implicated if we unpack how values enter into a dialogue: through dialogue between self and other. Given that we have defined the term other as encompassing context, including people and the different stories, ethical approaches, values, and guidelines within it, values in dialogue carries a number of potential ‘turns,’ which the word axis captures.

The term axis of universality is useful in conceptualising cross-cultural ethics as it articulates our findings that ethical values operate on both universality and variability. By juxtaposing the term ‘universality’ with the term ‘axis’ we are able to view ethical values on a continuum between universality and variability. This acts as a tool for locating ourselves in new terrain through increasing our awareness of ethical values in self in relation to ethical values in other. This enables the continuum of ethical issues such as universality and individuality, freedom and constraint, certainty, and uncertainty to be viewed in tandem. From this perspective, the accumulative influence of ethical issues is understood and consensus between ethical universality and ethical variability reached.

Meaningful dialogue emerged as an important tool for ICE researchers to navigate ethical values in practice. The framework mirrors this finding, placing meaningful dialogue at the centre of ethical processes, driving the interpretation, negation, and reinforcement of values. It was clear from responses that the most meaningful form of dialogue between self and other was associated with explanation, elaboration, and the co-production of values: ‘ … To redefine how we consider ethical issues within a global context’ and negotiate ‘a shared set of ethical principles with local partners and participants,’ (PR8). These characteristics are captured in the term co-constructive dialogue which acts as an alternative to disputational talk (indicative of conflict), accumulative talk (focused on maintaining the status-quo) and exploratory talk (logical deductive reasoning) from the literature on talk typologies (Mercer Citation2000, Citation2013). In contrast, co-constructive dialogue captures both verbal and non-verbal acts (experiential and tacit), broadening the definition of dialogue to encompass a dialogue with self and other (as context). This opens up dialogue with all aspects of a given context including people, stories, ethical approaches, values, and guidelines within it. Therefore, the five core values act as linchpins for locating self in relation to other and co-constructive dialogue acts as a tool for identifying grounds for consensus towards the five core values. What is determined to be good ethical practice is thus decided collaboratively rather than by individual researchers.

We have therefore purposively not developed a normative framework with a list of rules, checklists, or text heavy instructions. In contrast, we propose a set of core ethical values alongside a series of questions. This is aimed at capturing the dynamic and relational nature of ethics, which exists in the space between people, contexts, and stories. The framework puts forward the five ethical values – transparency and honesty, respect and care, conscious freedom, experiential and tacit awareness and reflexive practice – alongside suggested questions to instigate dialogue among research groups. We argue that values are a useful way of expressing general ethical commitments that underpin the purpose and goals of our actions. Significantly, we have chosen values rather than principles, which bring with them assumptions of normative intent (Hammersley Citation2015). We argue that values underlie the purpose of our actions and act as antecedents to the more explicit nature of principles. Values are embryonic principles, not yet defined through actions or directed towards ethical responsibilities. It is this emergent state accessed through values, which is most conducive to cross-cultural dialogue as it seeks to understand rather than to absolve.

The framework seeks to close the gap between deontological ethics on the one hand (presenting questions rather than rules) and consequentialist, situated ethics on the other hand (presenting the situation of values in context rather than context alone). The questions that sit within each value are intended to structure dialogue within contexts and partnership teams where research is taking place and are underpinned by data which articulated the re-appropriation of self in relation to other: ‘I justify how I am not causing harm, and I cite precedent and discipline-specific ethics protocols to support my case’ (PR32). For each value, we outline the issues that were identified by participants as key areas for consideration.

Conclusion

In this article we have put forward a dialogic framework that can be used by ICE researchers to facilitate the enactment of ethics in research. Through co-constructive dialogue, the different cultural ways of enacting ‘universal’ ethical values as intention can be understood, even if they are not agreed upon. As a by-product of these exchanges, ‘universal’ ethical values are useful as they provide a linchpin for re-imagining ethical values in cross culturally diverse ways. To articulate this relationality of ethical values our framework is called ‘Relational Values in Dialogue: A Framework for Ethical Research in International and Comparative Education.’ This extends the theory of relational ethics as a contemporary approach to ethics in several ways.

Firstly, our framework situates ethical values rather than ethical action in relationship. In this way, values are framed as key to acting ethically as values underlie the purpose of our actions and act as antecedents to the more explicit nature of ethical responsibility. Co-constructive dialogue is the mechanism through which we examine ourselves in relation to others. In this way, language (verbal and nonverbal) provides the tool for dismantling and reinforcing the values which underpin our stories for describing ethical self in relation to ethical other. This perception of ethics as relational calls to mind the Ubuntu Philosophy discussed earlier in this article, particularly its critiques on the assumption of individual freedom as guiding action and its belief in the relational bonds which drive all phenomena: ‘My humanity is tied to yours’ (Zulu proverb). This possible new way of considering ethics is one that we plan to take forward and explore its feasibility with the wider research community.

Secondly, our framework articulates the concept of other and relationship more broadly. For example, ethics is not only realised through the relationship between self and other but also through the relationship between values and dialogue, including the definition of values (I) and the enactment of values (me). The relationship between ethical values and dialogue is articulated as co constructive, indicating reflexivity, awareness, and knowledge co construction. Furthermore, the concept of other encompasses context, including people and the different stories, ethical approaches, values, and guidelines within it.

Thirdly, the concept of relationality is viewed on an axis of universality in order to identify the continuum of ethical issues in juxtaposition. These ethical issues include universality and variability, freedom and constraint, certainty, and uncertainty. Only when viewed together, can the accumulative influence of such paradoxical ethical issues be understood.

It is our intention that this framework could be used both by BAICE members and the wider international and comparative education community. However, given the value that we have placed on ongoing discussion, we also hope that they will be debated and adapted. There is space to galvanise the field further and we encourage this activity alongside the consideration of postcolonial ethics (Tikly and Bond Citation2013). This is especially pertinent for the many of us who work in contexts where there are distinct and structural inequalities that exist between the researcher, their home/university country, and the researched. It is our hope that the framework will help to contribute to this debate and guide how the ICE community acts with regards to ethics. The potential of ICE to play a pivotal role in grappling with globalised identities and transnational ethical debates such as global warming and the current global health pandemic, cannot be underplayed. The framework seeks to examine the ethical stories which are being written as a result of these global identities and transnational debates. In this way, the axis of universality values the complex global encounters in which we find ourselves, universally bound to divergence and change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. It is important to note that this analysis and the questionnaire data analysis presented in this article were conducted before the 2018 BERA guidelines were published. We recognise that these guidelines go some way to addressing the issue of context but do not believe that they are sufficiently focused on ICE research to address the concerns raised by the literature and questionnaire respondents. However, the framework proposed in this article is not intended to transpose the 2018 BERA guidelines but to enrich them.

References

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- David, M., R. Edwards, and P. Alldred. 2001. “Children and School-based Research: ‘Informed Consent’ or ‘Educated Consent’?” British Educational Research Journal 27 (3): 347–365. doi:10.1080/01411920120048340.

- De Laine, M. 2000. Fieldwork, Participation and Practice: Ethics and Dilemmas in Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Dwyer, A. M. 2006. “Ethics and Practicalities of Cooperative Fieldwork and Analysis.” In Essentials of Language Documentation, edited by Ulrike, J. G. N. P. H., 31–66. Boston.

- Guillemin, M., and L. Gillam. 2004. “Ethics, Reflexivity, and “Ethically Important Moments” in Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 10 (2): 261–280. doi:10.1177/1077800403262360.

- Halse, C., and A. Honey. 2007. “Rethinking Ethics Review as Institutional Discourse.” Qualitative Inquiry 13 (3): 336–352. doi:10.1177/1077800406297651.

- Hammersley, M. 2015. “On Ethical Principles for Social Research.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18 (4): 433–449. doi:10.1080/13645579.2014.924169.

- Harcourt, D., B. Perry, and T. Waller, eds. 2011. Researching Young Children’s Perspectives: Debating the Ethics and Dilemmas of Educational Research with Children. Oxford: Taylor & Francis.

- Heller, E., J. Christensen, L. Long, C. A. Mackenzie, P. M. Osano, B. Ricker, E. Kagan, and S. Turner. 2011. “Dear Diary: Early Career Geographers Collectively Reflect on Their Qualitative Field Research Experiences.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 35 (1): 67–83. doi:10.1080/03098265.2010.486853.

- Khoza, R. 2006. Let Africa lead: African Transformational Leadership for 21st Century Business. Johannesburg: Vesubuntu Pulishing.

- Kvale, S. 1996. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Interviewing. London: Sage.

- Lunn, J., ed. 2014. Fieldwork in the Global South: Ethical Challenges and Dilemmas. Oxford: Routledge.

- Luthans, F., R. Van Wyk, and F. O. Walumbwa:. 2004. “Recognition and Development of Hope for South African Organizational Leaders.” The Leadership & Organization Development Journal 25 (6): 512–527. doi:10.1108/01437730410556752.

- McMahon, E. (2018). “Comparative Analysis of Existing Ethical Guidelines.” Unpublished report.

- Mercer, N. 2000. Words and Minds. How We Use Language to Think Together. London: Routledge.

- Mercer, N. 2013. “The Social Brain, Language, and Goal-Directed Collective Thinking: A Social Conception of Cognition and Its Implications for Understanding How We Think, Teach, and Learn.” Educational Psychologist 48 (3): 148–168. doi:10.1080/00461520.2013.804394.

- Metz, T., and J. B. Gaie. 2010. “The African Ethic of Ubuntu/Botho: Implications for Research on Morality.” Journal of Moral Education 39 (3): 273–290. doi:10.1080/03057240.2010.497609.

- Milligan, L. 2016. “Insider-outsider-inbetweener? Researcher Positioning, Participative Methods and Cross-cultural Educational Research.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 46 (2): 235–250. doi:10.1080/03057925.2014.928510.

- Mucina, D. 2013. “Ubuntu Orality as a Living Philosophy.” The Journal of Pan-African Studies 6 (2013): 18–36.

- Parsons, S., C. Abbott, L. McKnight, and C. Davies. 2015. “High Risk yet Invisible: Conflicting Narratives on Social Research Involving Children and Young People, and the Role of Research Ethics Committees.” British Educational Research Journal 41 (4): 709–729. doi:10.1002/berj.3160.

- Robinson-Pant, A. 2005. Cross Cultural Perspectives on Educational Research. London: McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Robinson-Pant, A., and N. Singal. 2013a. “Researching Ethically across Cultures: Issues of Knowledge, Power and Voice.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 43 (4): 417–421. doi:10.1080/03057925.2013.797719.

- Robinson-Pant, A., and N. Singal. 2013b. “Research Ethics in Comparative and International Education: Reflections from Anthropology and Health.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 43 (4): 443–463. doi:10.1080/03057925.2013.797725.

- Silverman, C. 2000. “Researcher, Advocate, Friend: An American Fieldworker among Balkan Roma, 198-1996.” In Fieldwork Dilemmas: Anthropologists in Postsocialist States, edited by H. De Soto and N. Dudwick, 195–217. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

- Silverman, C. 2018. “From Reflexivity to Collaboration: Changing Roles of a Non-Romani Scholar, Activist, and Performer.” Critical Romani Studies 1 (2): 76–97. doi:10.29098/crs.v1i2.16.

- Simons, H., and R. Usher. 2012. Situated Ethics in Educational Research. 2nd ed. Oxford: Routledge.

- Small, R. 2002. “Codes are Not Enough: What Philosophy Can Contribute to the Ethics of Educational Research.” Journal of the Philosophy of Education 35 (3): 387–406. doi:10.1111/1467-9752.00234.

- Smith, L. T. 2006. “Researching in the Margins Issues for Māori Researchers a Discussion Paper.” Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 2 (1): 4–27. doi:10.1177/117718010600200101.

- Smith, L. T., E. Tuck, and K. W. Yang, eds. 2018. Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View. Oxford: Routledge.

- Stake, R., and Rizvi, F. 2009. “Research Ethics in Transnational Spaces.” In The handbook of Social Research Ethics, edited by Mertens, D. M., and Ginsberg, P. E., 521–536. London: Sage.

- Stutchbury, K., and A. Fox. 2009. “Ethics in Educational Research: Introducing a Methodological Tool for Effective Ethical Analysis.” Cambridge Journal of Education 39 (4): 489–504. doi:10.1080/03057640903354396.

- Takayama, K., A. Sriprakash, and R. Connell. 2017. “Toward a Postcolonial Comparative and International Education.” Comparative Education Review 61 (S1): S1–S24. doi:10.1086/690455.

- Tikly, L., and T. Bond. 2013. “Towards a Postcolonial Research Ethics in Comparative and International Education.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 43 (4): 422–442. doi:10.1080/03057925.2013.797721.

- Zhang, H., P. W. K. Chan, and J. Kenway, eds. 2015. Asia as Method in Education Studies: A Defiant Research Imagination. Oxford: Routledge.

Appendix 1

1. Are you a BAICE member?

2. What is your main research role?

3. Are you based in the UK?

4. Please state your main area of research:

5. Where do you go to get guidance about research ethics?

6a. How useful do you find this guidance for the type of research you undertake?

6b. Please explain your answer

7. If you conduct research outside of the UK, how do you negotiate ethical clearance in countries where research is taken place?

8. What do you think are the most challenging ethical issues that arise in cross-cultural and international research?

9. Can you give an example of an ethical issue you have encountered in your fieldwork? How did you respond? What guided you to respond in this way?

10. BAICE is considering developing core ethical principles in international and comparative research to be used alongside existing ethical guidelines, such as BERA. What do you think are the main ethical principles for researchers in the field of international and comparative education?