ABSTRACT

Transnational higher education (TNHE) has become an important research topic in international higher education (HE). Many universities have actively engaged in developing TNHE for diverse development goals, such as enhancing the internationalisation of HE, gaining financial benefits, and improving HE quality. While many researchers have explored TNHE-related issues from various perspectives (e.g. policy and management, learning and teaching, employability), relatively few studies have reviewed the historical development and landscape of TNHE research from comparative and international perspectives by adopting scientometric analysis. To fill this gap, we utilised CiteSpace to analyse TNHE-related research systematically. Based on reviewing journal articles indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection database, we illustrate the landscape of TNHE research (e.g. the overview of publication development, researchers, and research themes). Then, we summarise the current research status of TNHE and provide suggestions for future research.

Introduction

Since the 21st century, transnational higher education (TNHE) has become an important approach for academics, students, and educational resources to move around the world (Waters and Leung Citation2022). The origin of TNHE may be traced back to the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) leading to the global commodification and transnational operation of education (Hou, Montgomery, and McDowell Citation2014). Consequently, many developing countries (e.g. China, Vietnam, Malaysia, and United Arab Emirates) have ‘imported’ educational services from developed countries, such as the USA, the UK, and Australia (Altbach and Knight Citation2007). These practices are referred to as TNHE or cross-border education and have become increasingly popular due to the demand for international education in developing countries (Wilkins Citation2016).

Researchers (e.g. Dai Citation2020, Citation2021; Healey Citation2020; Levatino Citation2017; Li, Dai, and Zhang Citation2023; Sin, Leung, and Waters Citation2019; van der Rijst, Lamers, and Admiraal Citation2022; Wilkins and Neri Citation2019) have investigated TNHE-related issues in regional contexts, such as Asia, Europe, Oceania, Middle East, and America. The global expansion of TNHE has also brought about challenges, such as educational quality, university governance, and students’ development (Healey Citation2020). Meanwhile, a systematic review is missing from comparative and international perspectives. This scientometric review will systematically map the TNHE research field since its emergence. It aims to examine the development trends, challenges and opportunities for TNHE, particularly within the post-pandemic context. We ask two questions: 1) What are the research trends of TNHE? 2) Who are the major contributors of knowledge in the TNHE field?

Research method

To conduct a scientometric review of TNHE research since its emergence from approximately the early 2000s (Kosmützky and Putty Citation2016), CiteSpace is used as the analytic tool. CiteSpace is a scientometric software developed to map the knowledge domain of a research topic or field by synthesising and visualising bibliometric data into longitudinal trends and relational networks (e.g. countries, institutions, authors, journals, and topics) (Chen Citation2006). CiteSpace has two fundamental aspects: intellectual base and research fronts (Chen Citation2006). Intellectual base, as the evolving network of scientific literature interlinked by citation and co-citation, is the foundation from which clusters of concepts and underlying research issues emerge. These emerging trends are regarded as research fronts, each consisting of 40 to 50 recent articles that scholars frequently cite. CiteSpace could identify the ‘trajectories of competing paradigms, turning points of paradigm shifts, long-lasting research interests, and transient bursts of scholarly activities’ (Chen Citation2016, xvii). The current paper will examine the knowledge base and research fronts of global research on TNHE.

CiteSpace entails two data collection procedures: 1) to determine a reliable and reputable database that contains key bibliometric data (e.g. titles, authors, journals, keywords, abstracts, reference lists) of all publications of scientific value on a chosen topic; 2) to generate a unique dataset containing the inquired bibliometric information using keyword search in the database for scientometric analysis, where nodes and links are the two analytic units (Chen Citation2016). Nodes refer to the interconnected entities in a network displaying one type of bibliometric data. The important property of a node is betweenness centrality, which measures the number of shortest paths between all pairs of nodes that pass through a key node. It is visualised by scaling the size of the node and is useful for identifying authors/documents that broker collaboration with greater connectivity. The connections joining the nodes are known as links and their thickness indicates the strength of the interrelationship between two nodes.

The application of CiteSpace is independent of knowledge domain and commonly has three types of analysis (Fang, Yin, and Wu Citation2018). Collaboration analysis identifies the authors/institutions/countries that work more closely than others in forming a community of knowledge production in the field. Co-citation analysis identifies two items of research often cited together in ongoing literature, such as Author Co-citation Network (ACN) and Journal Co-citation Network (JCN). Keyword co-occurrence analysis relies on keyword co-occurrence matrix to display the research trends and topics by clusters either in a whole-field network or time-zone view tracking their progression overtime (Chen Citation2004).

Current studies utilising CiteSpace for systematic review in the global education field include those on international students (Jing et al. Citation2020) and higher education (Pan and An Citation2021; Tight Citation2012). However, no research has adopted a similar approach to reviewing the TNHE field. Different from some recent systematic reviews tapping the factors leading to successful development of TNHE programmes (Carvalho, Rosa, and Amaral Citation2022; Tran, Amando, and Santos Citation2023), we aim to identify the deep knowledge structure sustaining this field.

Research data

The current research utilised CiteSpace 5.8.R3 (64-bit) as the software. We first identified a set of keywords based on the widely recognised, and often interchangeable, terms for TNHE as input queries in the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection to retrieve all high-quality publications available on TNHE since 1999 (earliest record of TNHE research on WoS) until February 2022 (time of data collection). The keywords include transnational education (TNE), transnational higher education (TNHE), offshore education, borderless education, and cross-border education, synonyms referring to the international flow of educational services across contexts (Knight Citation2016; Yang Citation2008). WoS is one of the world’s largest and most authoritative bibliographic databases containing publications in multidisciplinary sciences. The indexed journal databases included as the core collection of WoS are Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-Expanded), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI), and Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI). We confined our search indexes to these three sources to retrieve high-quality articles in the social sciences. A total of 574 articles were identified after data screening.

Results and discussion

TNHE research trajectory

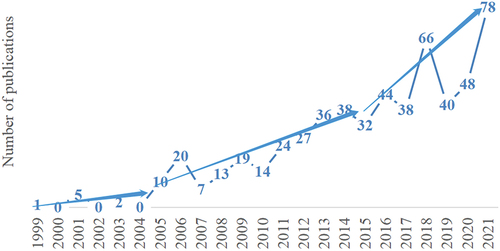

displays the upward publication trend of TNHE research since 1999 and until 2021. Given that manuscripts in social sciences usually take one to two years from submission to publication, a downward trend in a certain year does not necessarily suggest a lack of scholarly interest or output. Thus, we delineate the TNHE research trajectory into three waves based on the three trend-lines in , and previous review articles on TNHE development (Kosmützky and Putty Citation2016; Wilkins Citation2016), and thematic analysis of keyword citation bursts (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1. The number of journal articles related to TNHE in WoS core collection with trend-lines (1999–2021).

Wave I (1999–2004): TNHE institutionalisation

The emergence of scientific literature on TNHE began from 1999 to 2004. At this stage, formats of TNHE were being institutionalised to suffice as research topics for academic inquiry, as some early literature focused on TNHE regulation and management. McBurnie and Ziguras (Citation2001) were among the first authors to discuss TNHE regulation in Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Australia and the impact of the GATS on transnational tertiary education (Ziguras Citation2003). These early studies set the stage for understanding TNHE practices modelled after the Australian-South Asian higher educational collaboration.

Wave II (2005–2014): TNHE development

TNHE development phase refers to the development of programmes, partnerships, national policies and practices in TNHE following the globalisation trend in the 21st century. Of all 208 journal articles in this period, topics progressed from TNHE strategy and professionalisation (Scherrer Citation2005; Shams and Huisman Citation2012), management and quality assurance (Chapman and Pyvis Citation2006), regulation and marketisation (Mok Citation2008; Oleksiyenko, Cheng, and Yip Citation2013), to student and faculty experiences (Leung and Waters Citation2013; Seah and Edwards Citation2006; Wilkins, Stephens Balakrishnan, and Huisman Citation2012). Critical perspectives of TNHE development also emerged in this phase (Blackmur Citation2007).

Wave III (2015–2022): TNHE proliferation

TNHE proliferation refers to the fast growth of TNHE programmes and research publications globally. In total, 358 journal articles were found in these recent seven years. While previous research topics consistently appeared, some conceptual frameworks became more prevalent, such as globalisation, internationalisation of higher education, and student mobility (Tight Citation2021; Wilkins and Lan Citation2022; Zhang Citation2021).

Major contributors to the field

Prolific authors and collaboration networks

demonstrates the Top 10 most productive authors in the TNHE research field by publication frequency, measured by the number of articles published by a scholar as the first author. In the top 5, the most prolific author is Stephen Wilkins, Professor of Strategy and Marketing at The British University in Dubai. He has published 14 articles on TNHE management and development in the Arab Gulf States regarding student satisfaction and organisational management (Wilkins and Juusola Citation2018; Wilkins and Neri Citation2019; Wilkins and Stephens Balakrishnan Citation2013). The second is Ka Ho Mok, whose research focuses on TNHE policy, governance, and student development in East Asia (Mok Citation2008; Mok and Han Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017; Mok et al. Citation2018). Nigel Healey, Professor of International Higher Education at the University of Limerick, is the third productive author. His research focuses on the internationalisation of higher education, policy, and TNHE management (Healey Citation2015, Citation2017, Citation2023). The fourth productive author, Ravinder Sidhu, is Associate Professor at School of Education, The University of Queensland, Australia. Her research about TNHE mainly focuses on globlisation of universities and international student mobilities in East Asia. The fifth productive scholar is Johanna L. Waters, Professor of Human Geography at the UCL Department of Geography. Her research critically examines student mobility, social reproduction, and the transnational space of TNHE in Hong Kong (Waters and Leung Citation2012, Citation2013). Given that the TNHE field is relatively new within two decades of development, the author collaboration analysis did not produce a network (Supplementary Figure S2). While some prolific authors have regular collaborators, such as Johanna L. Waters and Maggi W. H. Leung, the links between co-authors do not extend to other nodes, suggesting that author collaboration in TNHE research is yet to be internationalised.

Table 1. A list of top 10 most productive authors in the TNHE field.

Country collaboration analysis

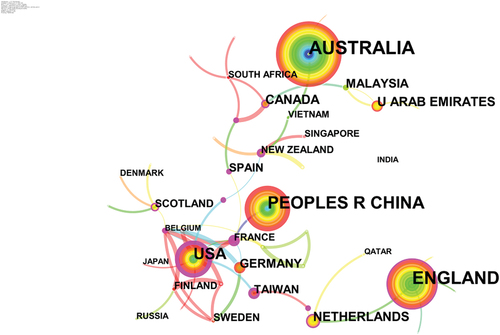

shows the country collaboration network in TNHE research, where 68 countries/regions established collaborative relationships. As demonstrated by the circle size, Australia published the most articles (118), followed by the UK (101), China (89), USA (57), United Arab Emirates (26), and the Netherlands (25). Notably, those countries were some of the largest sending (Australia, England, USA, the Netherlands) and host (China, UAE) countries of TNHE. Among the most published sending countries, only the USA has the greatest collaborative relationships with other countries with a betweenness centrality of 0.53. In comparison, Australia (0.04), China (0.00), and UAE (0.04) establish fewer collaborations with other countries, implying a regional/local approach to TNHE research collaboration. This finding is in line with institution collaboration analysis (Supplementary Figure S3), where no institution is a key node in the TNHE research network and most institutions remain scattered in a field of rather isolated actors (i.e. prolific single author representing their institutions) yet to be networked. Therefore, global collaboration in TNHE research shall be encouraged.

Author co-citation analysis

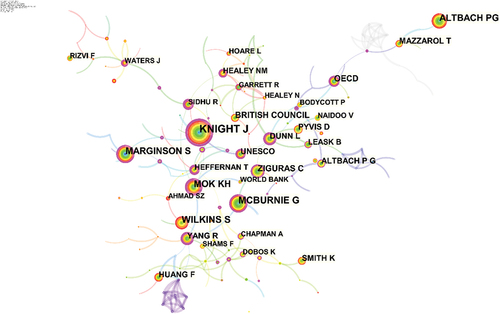

Author co-citation network in presents authors frequently co-cited in TNHE research. The analysis sums the publications cited of a scholar as first author. A total of 178 nodes and 243 co-citation links were identified. shows the 10 most cited authors and their co-citation frequency. The top three cited authors are Jane Knight, Stephen Wilkins, and Grant McBurnie. Knight is Adjunct Professor in the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at University of Toronto, specialising in the internationalisation of higher education. McBurnie was a senior research associate at RMIT university, known for his two co-authored books on TNHE with Ziguras (McBurnie and Ziguras Citation2006; Ziguras and McBurnie Citation2015). His research focuses on international student mobility and institutional governance in TNHE.

Table 2. Top 10 most cited authors with co-citation frequency.

The capacity of an author to join other nodes in the network is assessed by betweenness centrality, indicating the author’s scientific impact in the knowledge domain (Yan and Ding Citation2009). Those core authors are Ka Ho Mok (0.55), Knight (0.48), and OECD (0.33). In particular, Ka Ho Mok has both considerable output (see ) and scientific impact (0.55) in TNHE research. The works of other prolific authors from non-educational disciplines are less impactful with lower betweenness centrality, such as Wilkins (0.04) and Waters (0.23). Some other highly cited authors in TNHE publications are from the international/global education background, such as Knight (0.48), Ziguras (0.30), McBurnie (0.27), and Marginson (0.26). These results indicate that the current TNHE field is dominated by scholars from global higher education compared with other disciplines that also conduct TNHE research (e.g. management and geography) – when both knowledge production and circulation are considered. This inference is corroborated by further discipline distribution analysis where disciplinary clusters appear rather distinct with education taking predominance (Supplementary Figure S4). OECD is also a key node in the network given the significance of its joint guidelines with UNESCO on quality provision in cross-border higher education (OECD Citation2005).

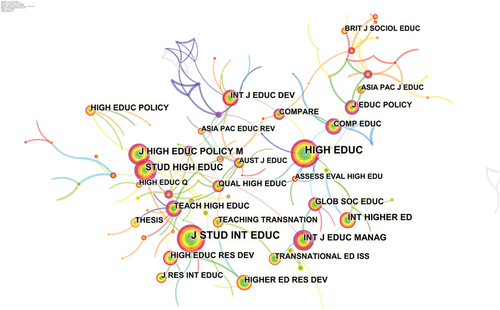

Journal co-citation analysis

displays the 10 most cited journals by co-citation frequency among all 195 journals in the journal co-citation network (). The 10 journals all feature international or higher education. Journal of Studies in Higher Education tops the list with 274 co-citations, followed by Higher Education and Studies in Higher Education. While journals with high impact factors are cited more often, two relatively low-impact journals and low co-citation frequency, Teaching in Higher Education (0.31) and International Journal of Educational Management (0.22), are the key players joining other nodes in the network. Particularly, some prolific authors in have published in International Journal of Educational Management (Ahmad, Buchanan, and Ahmad Citation2016; He and Liu Citation2018; Healey Citation2018; Mok Citation2008; Wilkins and Stephens Balakrishnan Citation2013), but none in Teaching in Higher Education, suggesting a research focus on educational management in TNHE. While International Higher Education is not a WoS journal in the original dataset, it is highly cited in the references of the sourced articles and thus becomes a key node in the co-citation network.

Table 3. Top 10 most cited journals with co-citation frequency.

Emerging trends in the TNHE field

References with citation bursts

Citation bursts indicate the increased attention academic works receive in a period of time, offering insights into the emerging topics that scholars pay attention to. Reference burst detection in CiteSpace summarises a list of published articles with the strongest citation bursts and the time range in which the strongest bursts take place. shows the top 25 references with the strongest citation bursts in TNHE research from 1999 to 2022. The beginning of dark blue blocks marks the publication year of an article and the blue continuum indicates the duration it has been cited; the red blocks in-between refer to the years when citations increased dramatically. Each block represents a year. As shown, Davis, Olsen, and Anthony’s (Citation2000) conference paper on Australian offshore education was the first cited work in TNHE research by journal articles included in the data, with a citation burst from 2005 to 2006, corresponding to the emergence of TNHE as a field in the same period. Since 2009, citation bursts of articles have been persistent over time, focusing on the emerging trends (Dunn and Wallace Citation2006; Huang Citation2007; McBurnie and Ziguras Citation2006; Olds Citation2007), strategies (Becker Citation2009; Wilkins and Huisman Citation2012), framework and practices (Altbach and Knight Citation2007) of TNHE – themes that continued to characterise ongoing publications.

Table 4. Top 25 references with strongest citation bursts.

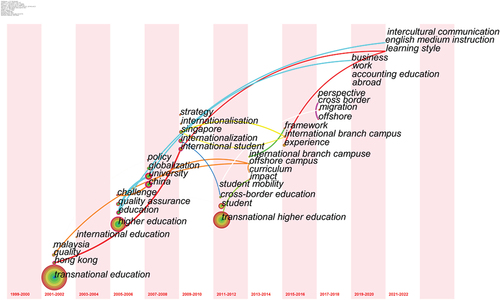

Keyword analysis over time

To understand when TNHE research keywords emerged and how they are related in a co-occurrence network over time, a time-zone view of keyword co-occurrence was shown in . The time spot of a keyword suggests its first occurrence in publication. Once a keyword appears again in later literature, its ring size becomes slightly bigger with increased occurrence. This explains why ‘transnational education’ is the largest circle, followed by ‘transnational higher education’ and ‘higher education’. The coloured line joining two keywords implies their co-occurrence in one or more publications. We summarise TNHE research development from 1999 to early 2022 into three themes: 1) TNHE policies and quality assurance; 2) Student motivations and experiences; and 3) Transnational fields and student mobility. We conclude this synthesis by suggesting the research gaps and future issues within the current context of post-pandemic TNHE.

TNHE policies and quality assurance

Since its inception, TNHE has featured the internationalisation of higher education as an overall win-win goal for both sending and host countries (Altbach and Knight Citation2007). However, when this universal framework is implemented locally, TNHE programmes are often caught between the national demand for globalisation and the specific logic of governance within local institutions (Mok and Han Citation2017). Scholars have explored the interconnections of global-national-local sectors in TNHE across a range of locations, including China (Han Citation2021; Mok and Han Citation2017), Ethiopia (Tamrat and Teferra Citation2021), Finland and Russia (Kallo and Semchenko Citation2016). The disparity between policy goals, such as internationalising education and talent development, and the reality of local TNHE practices raise concerns over educational equity, management, and quality assurance (e.g. Sharp Citation2017). Relevant problems have become the targets of strategy-making (Neri and Wilkins Citation2019). While much focus is on the top-down factors determining TNHE strategy- or policy-making, the bottom-up forces have not brought about significant shifts in programme management and quality supervision. Despite 41 publications on quality and quality assurance in TNHE, TNHE quality delivery remains a challenge, most possibly due to a lack of universal standard on quality assessment, programme management, and the global-local disjuncture (Lim et al. Citation2016).

Student motivations and experiences

Another stream of TNHE literature focuses on students’ choices for TNHE, their programme and learning experiences, and their transition/adaptation in TNHE. Students’ perspectives from some popular TNHE hubs (e.g. China and East Asia) have been investigated. Regarding school choice, Chinese students consider TNHE a middle destination between domestic higher education and overseas higher education out of concerns for economic affordability, academic aptitude, and personal development (e.g. Fang and Wang Citation2014). Malaysian students choose Australian offshore education for positional investments or self-transformations (Pyvis and Chapman Citation2007). Research on student experiences largely revolve around their perceptions of quality, learning experiences, and sociocultural adaptations (e.g. Dai, Matthews, and Renshaw Citation2020). While students were generally satisfied with programme and teaching quality at international branch campuses (e.g. Ahmad and Buchanan Citation2017; Wilkins, Stephens Balakrishnan, and Huisman Citation2012), others were unsatisfied with interpersonal contact and service processes (Bhuian Citation2016). It seems that students’ evaluations of TNHE quality varied by dimensions, some of which are not included in institutional quality assessment and are pursued differently across programmes/institutions. Therefore, quality assurance and policy-making need to concern the specific dimensions of programme experience that pertain to the needs of various stakeholders (e.g. students, faculty, institution).

Students in TNHE also face the demand of adapting to the academic norms of Western education. The experience of learning between two systems may result in intercultural transitions (Dai, Lingard, and Musofer Citation2020; Yu Citation2021). For example, Yu (Citation2021) pointed out the symbolic power of Western higher education reflected in Chinese students’ perceptions of TNHE. Learning adaptation also occurs for students facing two national sets of educational logic, such as hierarchical versus liberal learning management (Pyvis and Chapman Citation2005). Other sociocultural challenges posed by TNHE may exist in multilingual socialisation and academic identification (Chapman and Pyvis Citation2006; Ou and Gu Citation2021), reflecting the potential cross-cultural ignorance in teaching and learning practices between TNHE partners (Dai, Matthews, and Reyes Citation2020).

Transnational fields and student mobility

The third theme demonstrates a sociological focus on TNHE in global mobility and transnational migration. Geographically, some countries/regions received greater research attention than others and have thus become transnational fields of student mobility. These places dominating current literature are ‘Australia’ (0.36), ‘China’ (0.33), ‘Asia’ (0.24), ‘Hong Kong’ (0.21), ‘Malaysia’ (0.14), and ‘Singapore’ (0.1). The Asia Pacific has obviously become a TNHE hub of knowledge economies within the internationalisation trend that diversified international student mobility. Regarding TNHE mobility via transnationalism, scholars have focused the socio-political motivations of governments and sociocultural motivations of students in pursuing TNHE. Specifically, government policymakers emphasise the enhancement of soft power by bringing TNHE into local higher education fields (Mok Citation2012) as infrastructures of im/mobility that keep students within the local economy (Kleibert Citation2022). The growing impact of geo-politics on international student mobility would further promote TNHE into local higher education fields, especially when students plan for overseas learning have taken personal safety and potential symbolic violence encountered with the anti-Asian movement since the COVID-19 crisis (Hartmann and Mok Citation2021; Mok and Mok Citation2023).

Compared to traditional student mobility requiring substantial economic resources, TNHE offers students and families an opportunity to achieve greater social mobility and social reproduction at home (Tsang Citation2013). Thus, TNHE also serves as transnational spaces of flexible mobility and strategic investments (Gargano Citation2009). From a transnational perspective, there is a considerable intersection of macro-, meso-, and micro-level factors that influence students’ mobility choices in TNHE, reflecting the dynamics of policies, practices, programmes, and individual cosmopolitan aspirations in this field (Li, Haupt, and Lee Citation2021). Having experienced the challenging time resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic era, scholars should also take the broader geo-political perspectives when analysing the patterns and development of international learning (Mok Citation2022; Guan, Mok, and Yu Citation2023).

Regarding the multi-faceted dynamics of TNHE, one question has rarely been addressed. That is, TNHE for whose interest? Student experiences in TNHE are important, but probably not as highlighted as the neoliberal framework of higher education they represent in the global commodification of TNHE (Knight Citation2008). No doubt, the TNHE field is filled with complexities and contradictions (Hou, Montgomery, and McDowell Citation2014). Yet it is critical for scholars, especially those who serve both insider and outsider positions in the field to interrogate the core issues underlying the gap between decision-makers distanced from educational practices, and education practitioners/students alienated or objectified by policies. Intuitively, quality assurance of TNHE is the bridge across policies and practices in serving the interest of different stakeholders in the TNHE system for its sustainable development. In analysing these issues, scholars point out the cross-cultural differences that may distinguish host and sending countries’ systematic differences in their educational approaches (Dai, Matthews, and Reyes Citation2020). However, critical reflections should also be given to the power dynamics embedded in TNHE, such as neoliberalism versus nationalism, and potential colourism that racialises faculty experiences in transnational education delivery (Koh and Lin Sin Citation2022).

Finally, in a post-pandemic era of international student mobility and geopolitical uncertainties, TNHE equally face opportunities and challenges. TNHE may increasingly become a substitute for international higher education (Mok et al. Citation2021) and more TNHE programmes may emerge soon, forming new regional education hubs, for example, intra-country branch campues operated by Hong Kong institutions in the Greater Bay Area (see Dai, Wilkins, and Zhang Citation2023). The underlying dynamics and complexities reviewed above may also become more obvious as TNHE policy priorities shift with global geopolitics and national interests.

Conclusion

This article provides a scientometric review of TNHE-related research by analysing publications archived in WoS. Findings illustrate the landscape of the TNHE research, including trajectory, active scholars, key journals, networks, and emerging trends, offering an international and comparative perspective. Regarding how TNHE has developed in a globalised world and how it will develop in a post-pandemic world recovering from these years of anti-globlisation, we offer some suggestions. First, there is much room for researchers, institutions, and countries to collaborate beyond cultures in identifying the common problems of TNHE across its sub-fields and seek shared solutions. Second, much interdisciplinary collaboration is needed to bridge knowledge gaps, and make TNHE a truly networked field with diversified research fronts. Third, alternative research paradigms may be brought in to foster methodological pluralism and bring practical changes, such as critical studies or action-oriented research. These directions may support researchers from different regions to explore TNHE-related issues more effectively. In conclusion, although we have begun to resume normalcy after COVID-19, the closure of national borders and the rise of online learning during the crisis may have significantly affected the future development of TNHE. More research is needed to track changes in terms of motivations, student experiences and destination/learning mode choices at the individual level. More research should also be conducted to examine how factors at the macro and meso levels (i.e. broader political economy and institutional arrangements) would have affected international student mobility in general and TNHE in particular. A limitation of this review is that it only focuses on WoS indexed data and future study may explore a broader literature scope.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (729.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2023.2292517

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmad, S. Z., and F. R. Buchanan. 2017. “Motivation Factors in Students Decision to Study at International Branch Campuses in Malaysia.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (4): 651–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1067604.

- Ahmad, S. Z., F.Robert Buchanan, and N. Ahmad. 2016. “Examination of students’ Selection Criteria for International Education.” International Journal of Educational Management 30 (6): 1088–1103. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-11-2014-0145.

- Altbach, P. G., and J. Knight. 2007. “The Internationalization of Higher Education: Motivations and Realities.” Journal of Studies in International Education 11 (3–4): 290–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303542.

- Becker, R. F. J. 2009. International Branch Campuses: Markets and Strategies. London: Observatory on Borderless Higher Education (OBHE).

- Bhuian, S. N. 2016. “Sustainability of Western Branch Campuses in the Gulf Region: Students’ Perspectives of Service Quality.” International Journal of Educational Development 49: 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.05.001.

- Blackmur, D. 2007. “A Critical Analysis of the UNESCO/OECD Guidelines for Quality Provision of Cross‐Border Higher Education.” Quality in Higher Education 13 (2): 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320701629137.

- Carvalho, N., M. J. Rosa, and A. Amaral. 2022. “Cross-Border Higher Education and Quality Assurance. Results from a Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Studies in International Education 27 (5): 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153221076900.

- Chapman, A., and D. Pyvis. 2006. “Quality, Identity and Practice in Offshore University Programmes: Issues in the Internationalization of Australian Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 11 (2): 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510500527818.

- Chen, C. 2004. “Searching for Intellectual Turning Points: Progressive Knowledge Domain Visualization.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101 (suppl_1): 5303–5310. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0307513100.

- Chen, C. 2006. “CiteSpace II: Detecting and Visualizing Emerging Trends and Transient Patterns in Scientific Literature.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (3): 359–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317.

- Chen, C. 2016. CiteSpace: A Practical Guide for Mapping Scientific Literature. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

- Dai, K. 2020. “Learning Between Two Systems: A Chinese Student’s Reflexive Narrative in a China-Australia Articulation Programme.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 50 (3): 371–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1515008.

- Dai, K. 2021. Transitioning ‘In-Between’: Chinese Students’ Navigating Experiences in Transnational Higher Education Programmes. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Dai, K., B. Lingard, and R. P. Musofer. 2020. “Mobile Chinese Students Navigating Between Fields: (Trans)forming Habitus in Transnational Articulation Programmes?” Educational Philosophy and Theory 52 (12): 1329–1340. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1689813.

- Dai, K., K. E. Matthews, and P. Renshaw. 2020. “Crossing the ‘Bridges’ and Navigating the ‘Learning gaps’: Chinese Students Learning Across Two Systems in a Transnational Higher Education Programme.” Higher Education Research & Development 39 (6): 1140–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1713731.

- Dai, K., K. E. Matthews, and V. Reyes. 2020. “Chinese students’ Assessment and Learning Experiences in a Transnational Higher Education Programme.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (1): 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1608907.

- Dai, K., S. Wilkins, and X. Zhang. 2023. “Understanding Contextual Factors Influencing Chinese Students to Study at a Hong Kong Institution’s Intra-Country Branch Campus.” Journal of Studies in International Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153231205079.

- Davis, D., A. Olsen, and B. Anthony. 2000. “Transnational Education Providers, Partners and Policy: Challenges for Australian Institutions Offshore.” In The 14th Australian International Education Conference, Brisbane 2000. Brisbane, Australia: IDP Education Australia.

- Dunn, L., and M. Wallace. 2006. “Australian Academics and Transnational Teaching: An Exploratory Study of Their Preparedness and Experiences.” Higher Education Research & Development 25 (4): 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360600947343.

- Fang, W., and S. Wang. 2014. “Chinese students’ Choice of Transnational Higher Education in a Globalized Higher Education Market: A Case Study of W University.” Journal of Studies in International Education 18 (5): 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315314523989.

- Fang, Y., J. Yin, and B. Wu. 2018. “Climate Change and Tourism: A Scientometric Analysis Using CiteSpace.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26 (1): 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1329310.

- Gargano, T. 2009. “(Re) conceptualizing international student mobility: The potential of transnational social fields.” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (3): 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315308322060.

- Guan, L. H., K. H. Mok, and B. Yu. 2023. “Pull Factors in Choosing a Higher Education Study Abroad Destination After the Massive Global Immobility: A Re-Examination from Chinese Perspectives.” Cogent Education 10 (1): 2199625.

- Han, X. 2021. “Disciplinary Power Matters: Rethinking Governmentality and Policy Enactment Studies in China.” Journal of Education Policy 38 (3): 408–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2021.2014570.

- Hartmann, E., and K. H. Mok. 2021. “Knowledge, Power and Geopolitics of Transnational Higher Education.” Paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research General Conference. https://scholars.ln.edu.hk/en/publications/knowledge-power-and-geopolitics-of-transnational-higher-education

- He, L., and E. Liu. 2018. “Cultural Influences on the Design and Management of Transnational Higher Education Programs in China: A Case Study of Three Programs.” International Journal of Educational Management 32 (2). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-02-2017-0044.

- Healey, N. M. 2015. “Towards a Risk-Based Typology for Transnational Education.” Higher Education 69 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9757-6.

- Healey, N. M. 2016. “The Challenges of Leading an International Branch Campus: The ‘Lived experience’ of In-Country Senior Managers.” Journal of Studies in International Education 20 (1): 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315602928.

- Healey, N. M. 2017. “Transnational Education and Domestic Higher Education in Asian-Pacific Host Countries.” Pacific-Asian Education Journal 29 (1): 57–74.

- Healey, N. M. 2018. “The Challenges of Managing Transnational Education Partnerships: The Views of ‘Home-based’ Managers Vs ‘In-country’ Managers.” International Journal of Educational Management 32 (2): 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2017-0085.

- Healey, N. M. 2020. “The End of Transnational Education? The View from the UK.” Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 24 (3): 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2019.1631227.

- Healey, N. M. 2023. “Transnational Education: The Importance of Aligning stakeholders’ Motivations with the Form of Cross‐Border Educational Service Delivery.” Higher Education Quarterly 77 (1): 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12371.

- Healey, N., and L. Michael. 2015. “Towards a New Framework for Analysing Transnational Education.” Higher Education Policy 28 (3): 369–391. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2014.17.

- Heffernan, T., M. Morrison, P. Basu, and A. Sweeney. 2010. “Cultural Differences, Learning Styles and Transnational Education.” Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management 32 (1): 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800903440535.

- Hoare, L. 2013. “Swimming in the Deep End: Transnational Teaching as Culture Learning?” Higher Education Research & Development 32 (4): 561–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.700918.

- Hou, J., C. Montgomery, and L. McDowell. 2014. “Exploring the Diverse Motivations of Transnational Higher Education in China: Complexities and Contradictions.” Journal of Education for Teaching 40 (3): 300–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2014.903028.

- Hu, M., and L.-D. Willis. 2017. “Towards a Common Transnational Education Framework: Peculiarities in China Matter.” Higher Education Policy 30 (2): 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-016-0021-9.

- Huang, F. 2007. “Internationalization of Higher Education in the Developing and Emerging Countries: A Focus on Transnational Higher Education in Asia.” Journal of Studies in International Education 11 (3–4): 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303919.

- Jing, X., R. Ghosh, Z. Sun, and Q. Liu. 2020. “Mapping Global Research Related to International Students: A Scietometric Review.” Higher Education 80 (3): 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00489-y.

- Kallo, J., and A. Semchenko. 2016. “Translation of the UNESCO/OECD Guidelines for Quality Provision in Cross-Border Higher Education into Local Policy Contexts: A Comparative Study of Finland and Russia.” Quality in Higher Education 22 (1): 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2016.1144902.

- Kleibert, J. M. 2022. “Transnational Spaces of Education as Infrastructures of Im/Mobility.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47 (1): 92–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12475.

- Knight, J. 2008. “The Role of Cross-Border Education in the Debate on Education as a Public Good and Private Commodity.” Journal of Asian Public Policy 1 (2): 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/17516230802094478.

- Knight, J. 2015. “International universities: Misunderstandings and emerging models?” Journal of Studies in International Education 19 (2): 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315572899.

- Knight, J. 2016. “Transnational Education Remodelled: Toward a Common TNE Framework and Definitions.” Journal of Studies in International Education 20 (1): 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315602927.

- Koh, S. Y., and I. Lin Sin. 2022. “Race, Whiteness and Internationality in Transnational Education: Academic and Teacher Expatriates in Malaysia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (4): 656–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2021.1977362.

- Kosmützky, A., and R. Putty. 2016. “Transcending Borders and Traversing Boundaries: A Systematic Review of the Literature on Transnational, Offshore, Cross-Border, and Borderless Higher Education.” Journal of Studies in International Education 20 (1): 8–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315604719.

- Leung, M. W., and J. L. Waters. 2013. “British Degrees Made in Hong Kong: An Enquiry into the Role of Space and Place in Transnational Education.” Asia Pacific Education Review 14 (1): 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-013-9250-4.

- Levatino, A. 2017. “Transnational Higher Education and International Student Mobility: Determinants and Linkage.” Higher Education 73 (5): 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-9985-z.

- Li, X., J. Haupt, and J. Lee. 2021. “Student Mobility Choices in Transnational Education: Impact of Macro-, Meso-And Micro-Level Factors.” Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management 43 (6): 639–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2021.1905496.

- Li, X., K. Dai, and X. Zhang. 2023. “Transnational Higher Education in China: Policies, Practices, and Development in a (Post-)Pandemic Era.” Higher Education Policy. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-023-00328-x.

- Lim, C. B., D. Bentley, F. Henderson, S. Y. Pan, V. D. Balakrishnan, D. M. Balasingam, and Y. Y. Teh. 2016. “Equivalent or Not? Beyond Measuring Teaching and Learning Standards in a Transnational Education Environment.” Quality Assurance in Education 24 (4): 528–540. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-01-2016-0001.

- McBurnie, G., and C. Ziguras. 2001. “The Regulation of Transnational Higher Education in Southeast Asia: Case Studies of Hong Kong, Malaysia and Australia.” Higher Education 42 (1): 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017572119543.

- McBurnie, G., and C. Ziguras. 2006. Transnational Education: Issues and Trends in Offshore Higher Education. New York: Routledge.

- Miller‐Idriss, C., and E. Hanauer. 2011. “Transnational Higher Education: Offshore Campuses in the Middle East.” Comparative Education 47 (2): 181–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2011.553935.

- Mok, K. H. 2008. “Singapore’s Global Education Hub Ambitions: University Governance Change and Transnational Higher Education.” International Journal of Educational Management 22 (6): 527–546. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540810895444.

- Mok, K. H. 2012. “The Rise of Transnational Higher Education in Asia: Student Mobility and Studying Experiences in Singapore and Malaysia.” Higher Education Policy 25 (2): 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2012.6 .

- Mok, K. H. 2022. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and International Higher Education in East Asia.” In Changing Higher Education in East Asia, edited by S. Marginson and X. Xu, 225–246. London: Bloomsbury.

- Mok, K. H., and X. Han. 2016a. “From ‘Brain Drain’to ‘Brain bridging’: Transnational Higher Education Development and Graduate Employment in China.” Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management 38 (3): 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1174409.

- Mok, K. H., and X. Han. 2016b. “The Rise of Transnational Higher Education and Changing Educational Governance in China.” International Journal of Comparative Education and Development 18 (1): 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-10-2015-0007.

- Mok, K. H., and X. Han. 2017. “Higher Education Governance and Policy in China: Managing Decentralization and Transnationalism.” Policy and Society 36 (1): 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1288964.

- Mok, K. H., X. Han, J. Jiang, and X. Zhang. 2018. “International and Transnational Education for Whose Interests? A Study on the Career Development of Chinese Students.” Higher Education Quarterly 72 (3): 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12165.

- Mok, K. H., and W. C. E. Mok. 2023. “Health Hazard and Symbolic Violence: The Impact of Double Disturbance on International Learning Experiences.” In Reimagining Higher Education, System Reform and Quality Management, edited by A. Y. C. Hou, J. Smith, K. H. Mok, and C.-Y. Guo, 3–19. Singapore: Springer.

- Mok, K. H., W. Xiong, Ke, G., and J. Oi Wun Cheung. 2021. “Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on International Higher Education and Student Mobility: Student Perspectives from Mainland China and Hong Kong.” International Journal of Educational Research 105:101718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101718.

- Naidoo, V. 2009. “Transnational Higher Education: A Stock Take of Current Activity.” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (3): 310–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315308317938.

- Neri, S., and S. Wilkins. 2019. “Talent Management in Transnational Higher Education: Strategies for Managing Academic Staff at International Branch Campuses.” Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management 41 (1): 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1522713.

- OECD. 2005. “Guidelines for Quality Provision in Cross-Border Higher Education.” https://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/35779480.pdf.

- Olds, K. 2007. “Global Assemblage: Singapore, Foreign Universities, and the Construction of a ‘Global Education Hub.” World Development 35 (6): 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.05.014.

- Oleksiyenko, A., K.-M. Cheng, and H.-K. Yip. 2013. “International Student Mobility in Hong Kong: Private Good, Public Good, or Trade in Services?” Studies in Higher Education 38 (7): 1079–1101. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.630726.

- Ou, W. A., and M. M. Gu. 2021. “Language Socialization and Identity in Intercultural Communication: Experience of Chinese Students in a Transnational University in China.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24 (3): 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1472207.

- Pan, L., and T. An. 2021. “The Evolutionary Characteristics of Higher Education Studies Worldwide: Central Themes and Regions.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (12): 2568–2580. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1735331.

- Pyvis, D., and A. Chapman. 2005. “Culture Shock and the International Student ‘Offshore’.” Journal of Research in International Education 4 (1): 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240905050289.

- Pyvis, D., and A. Chapman. 2007. “Why University Students Choose an International Education: A Case Study in Malaysia.” International Journal of Educational Development 27 (2): 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2006.07.008.

- Scherrer, C. 2005. “GATS: Long-Term Strategy for the Commodification of Education.” Review of International Political Economy 12 (3): 484–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290500170957.

- Seah, W. T., and J. Edwards. 2006. “Flying In, Flying Out: Offshore Teaching in Higher Education.” Australian Journal of Education 50 (3): 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494410605000306.

- Shams, F., and J. Huisman. 2012. “Managing Offshore Branch Campuses: An Analytical Framework for Institutional Strategies.” Journal of Studies in International Education 16 (2): 106–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315311413470.

- Sharp, K. 2017. “The Distinction Between Academic Standards and Quality: Implications for Transnational Higher Education.” Quality in Higher Education 23 (2): 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2017.1356615.

- Sin, I. L., M. W. H. Leung, and J. L. Waters. 2019. “Degrees of Value: Comparing the Contextual Complexities of UK Transnational Education in Malaysia and Hong Kong.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 49 (1): 132–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2017.1390663.

- Smith, K. 2009. “Transnational Teaching Experiences: An Under-Explored Territory for Transformative Professional Development.” International Journal for Academic Development 14 (2): 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440902969975.

- Tamrat, W., and D. Teferra. 2021. “Advancing Transnational Higher Education in Ethiopia: Policy Promises and Realities.” Journal of Studies in International Education 26 (5): 623–639. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153211042088.

- Tight, M. 2012. “Higher Education Research 2000-2010: Changing Journal Publication Patterns.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (5): 723–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.692361.

- Tight, M. 2021. “Globalization and Internationalization as Frameworks for Higher Education Research.” Research Papers in Education 36 (1): 52–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1633560.

- Tran, N. H. N., C. A. D. E. F. Amando, and S. P. D. Santos. 2023. “Challenges and Success Factors of Transnational Higher Education: A Systematic Review.” Studies in Higher Education 48 (1): 113–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2121813.

- Tsang, E. Y.-H. 2013. “The Quest for Higher Education by the Chinese Middle Class: Retrenching Social Mobility?” Higher Education 66 (6): 653–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9627-7.

- van der Rijst, R. M., A. M. Lamers, and W. F. Admiraal. 2022. “Addressing Student Challenges in Transnational Education in Oman: The Importance of Student Interaction with Teaching Staff and Peers.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 53 (7): 1189–1205. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2021.2017768.

- Waters, J., and M. Leung. 2012. “Young People and the Reproduction of Disadvantage Through Transnational Higher Education in Hong Kong.” Sociological Research Online 17 (3): 239–246. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.2499.

- Waters, J., and M. Leung. 2013. “Immobile Transnationalisms? Young People and Their in situ Experiences of ‘International’education in Hong Kong.” Urban Studies 50 (3): 606–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012468902.

- Waters, J., and M. W. H. Leung. 2022. “Chapter 15: Transnational Higher Education.” In Handbook on Transnationalism, edited by B. S. A. Yeoh and F. L. Collins, 230–245. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Wilkins, S. 2016. “Transnational Higher Education in the 21st Century.” Journal of Studies in International Education 20 (1): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315625148.

- Wilkins, S. 2017. “Ethical Issues in Transnational Higher Education: The Case of International Branch Campuses.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (8): 1385–1400. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1099624.

- Wilkins, S., and J. Huisman. 2012. “The International Branch Campus as Transnational Strategy in Higher Education.” Higher Education 64 (5): 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9516-5.

- Wilkins, S., and K. Juusola. 2018. “The Benefits and Drawbacks of Transnational Higher Education: Myths and Realities.” The Australian Universities’ Review 60 (2): 68–76.

- Wilkins, S., and H. Lan. 2022. “Student Mobility in Transnational Higher Education: Study Abroad at International Branch Campuses.” Journal of Studies in International Education 26 (1): 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315320964289.

- Wilkins, S., and S. Neri. 2019. “Managing Faculty in Transnational Higher Education: Expatriate Academics at International Branch Campuses.” Journal of Studies in International Education 23 (4): 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318814200.

- Wilkins, S., and M. Stephens Balakrishnan. 2013. “Assessing Student Satisfaction in Transnational Higher Education.” International Journal of Educational Management 27 (2): 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513541311297568.

- Wilkins, S., M. Stephens Balakrishnan, and J. Huisman. 2012. “Student Satisfaction and Student Perceptions of Quality at International Branch Campuses in the United Arab Emirates.” Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management 34 (5): 543–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2012.716003.

- Yan, E., and Y. Ding. 2009. “Applying Centrality Measures to Impact Analysis: A Coauthorship Network Analysis.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (10): 2107–2118. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21128.

- Yang, R. 2008. “Transnational Higher Education in China: Contexts, Characteristics and Concerns.” Australian Journal of Education 52 (3): 272–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494410805200305.

- Yu, J. 2021. “Consuming UK Transnational Higher Education in China: A Bourdieusian Approach to Chinese students’ Perceptions and Experiences.” Sociological Research Online 26 (1): 222–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780420957040.

- Zhang, Y. 2021. “Student Evaluation of Sino-Foreign Cooperative Universities: From the Perspective of Internationalization of Higher Education.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 43 (4): 1107–1124. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2021.2008872.

- Ziguras, C. 2003. “The Impact of the GATS on Transnational Tertiary Education: Comparing Experiences of New Zealand, Australia, Singapore and Malaysia.” The Australian Educational Researcher 30 (3): 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216799.

- Ziguras, C., and G. McBurnie. 2015. Governing Cross-Border Higher Education. New York: Routledge.