ABSTRACT

Policies on internationalisation exist in Higher Education around the world, but no literature is currently available which draws together scholarly responses to these policies. This study reviews responses to internationalisation policy for ‘Home’ students (as opposed to international students) in Higher Education Institutions globally. A systematic literature search was conducted to identify internationalisation policy responses which focused on practice impacting specifically on ‘Home’ students. Eighteen peer reviewed sources were selected for analysis. Key themes were purpose, collaboration, implementation and defining success. Conclusions centred around the need for clarity in policy objectives, means of measuring policy success, and the risks of perpetuating dominant paradigms of inequality. Recommendations for policymakers are for clarity in the purposes of internationalisation, for alignment between national and institutional policies and student experience, and for policy outcomes to be measurable.

Introduction

Since medieval times, universities have been beacons of internationalisation, bringing together students, staff and knowledge from around the world (Altbach Citation2003). In modern times, it would be difficult to find a university which does not claim to be ‘international’, in scope, aims, relevance or offering. Over the past few decades in Higher Education (HE), internationalisation has become a centrally important strategic agenda (De Wit and Altbach Citation2015). There has been a tendency for literature on internationalisation to focus on one aspect – student mobility – and this aspect impacts only a very small proportion of students (De Wit and Hunter Citation2015). While research into the internationalisation of HE is prolific (Mittelmeier et al. Citation2022), studies which are specifically relevant to the ‘home’ student are uncommon (Da Silva Citation2020; Leask Citation2015; Stein Citation2017). This study aimed to examine the policy intersection between home students and HE internationalisation, as evidenced in the literature. Refocusing the parameters in this way is significant for the internationalisation community; when internationalisation is to impact all students and not only those who travel overseas for education, the scarcity of policy approaches and the lack of evidenced impact on student learning outcomes is stark.

Conceptualisation of internationalisation

Definitions of internationalisation vary; ‘inter’ and ‘nation’ denote the significance of crossing national boundaries, but within HE there has been complexity in the purposes, practicalities and implications. In the 1990s student mobility was the focus, including study abroad programmes and international student recruitment (De Wit Citation2014), and this developed into internationalised perspectives emerging in the curriculum, the quality assurance, the teaching, and increasingly also in the overseas delivery of courses. In 1995 education was classified as a tradeable commodity for the first time, by the General Agreement on Trade in Services of the World Trade Organisation (Li Citation2018). This significant development posed both opportunities and threats for HE’s understanding of internationalisation (Knight Citation2002). The legitimate marketisation of education changed parameters, for example by pushing up quality through competition, raising revenue for institutions, making education available for all regardless of nationality, and simultaneously limiting access to those with the means to pay. Powered by internationalisation, commercial forces moved from the fringe to the core in HE (Brandenburg and De Wit Citation2011; Li Citation2018).

Creating a definition of ‘internationalisation’ across the sector has been complicated by the range of activities and goals involved. Knight (Citation2002) noted that without clarity on what was to be achieved, the purpose of internationalising was unclear: ‘The term internationalization refers to the process of integrating an international dimension into the teaching, research and service functions of HE institutions’ (4). Although this definition gained popularity among scholars, Maringe et al. (Citation2013) commented on the lack of evidence of its impact in university policy around the world. The United Nations Population Division definition of internationalisation referred to ‘institutional arrangements set up by governments, universities and education agents that involve the delivery of Higher Education services in two or more countries’ (Kritz Citation2006). This frames cross-border education as the sole means of internationalisation, which differs considerably from an institutional approach to teaching which incorporates intercultural dimensions.

Knight’s revised definition (Knight Citation2008) was well received in the sector: ‘integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions or delivery of post-secondary education’ (21). This definition gives a focus on process over product but lacks clarity on what was to be achieved and so the purpose for internationalisation still remained contested. Following an impactful Delphi Panel, De Wit and Hunter’s (Citation2015) update of Knight’s (Citation2008) definition was significant; purposes underpinning internationalisation were addressed, and intent was clarified: ‘The intentional process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions and delivery of post-secondary education, in order to enhance the quality of education and research for all students and staff, and to make a meaningful contribution to society.’ (p3). This definition also clarifies an intention for internationalisation to impact on ‘all’ students and ‘not just for the mobile few’ (2). This inclusive definition forms an important basis for this literature review. Although the number of internationally mobile students has risen considerably over the past two decades (OECD Citation2022), it still represents only a very small proportion of students overall. Travelling overseas for all or part of one’s education is only one way to develop international awareness and competencies (Weimer, Hoffman, and Silvonen Citation2019); international and multicultural understandings and experiences can be integrated into the HE environment at home (Garam Citation2012).

‘Home’ students

In 2013 the European Commission (Citation2013) spelled out the need for HE policies to demonstrate an understanding of the non-mobile majority student population and the need for inclusivity in the design and content of internationalisation approaches. Terminology such as Internationalisation at Home (Crowther et al. Citation2000), and Internationalisation of the Curriculum (Leask Citation2009), became incorporated into the language of HE internationalisation, but will not be the focus of this policy paper. By ensuring that curricula integrate internationalised dimensions purposefully throughout (Beelen and Jones Citation2015), on-campus internationalisation gives access to an internationally rich study experience regardless of the student’s background or access to overseas opportunities (Zou et al. Citation2020), representing a democratisation of the benefits (Harrison Citation2015).

It is surprising that a great many sources which purport to examine internationalisation in HE do not consider the experience of the vast (non-mobile) majority of students and focus solely on the small proportion who have the will and the means to study outside of their country (for example Gacel-Ávila Citation2012; Lane et al. Citation2014; Stensaker et al. Citation2008). There is a great deal of scholarly debate on the internationalisation of HE (Mittelmeier et al. Citation2022), but very little that relates specifically to the ‘home’ student (Da Silva Citation2020; Leask Citation2015; Stein Citation2017).

The research question addressed in this systematic literature review is: ‘In what ways does the literature characterise the interaction between Higher Education internationalisation policy and Home student populations?’ This question is of value to the Internationalisation community in that it re-sets the parameters of the conversation to focus on what can be universally relevant, rather than what focuses on the small minority who travel overseas for study purposes. The review outcomes were wide-ranging, and so a decision was made by the authors to divide the data into three subsets: Policy, Evidence and Theory. The present study presents the data on Policy.

Methods

To enable a rigorous review of peer-reviewed publications on the topic, to clarify what is known and highlight what is not yet known, a systematic literature review was conducted. A literature-based approach was considered to be the most comprehensive strategy to include all world regions in this knowledge creation.

Search terms were identified through an exploratory and iterative process within the literature. Whilst there was a wealth of literature on international student recruitment, acculturation and other aspects relating to student mobility, the choice of key words was driven by the need to focus on internationalised aspects of the learning experience for ‘all’ students instead of the mobile minority. The word ‘home’, which is used in common parlance to acknowledge these students, was not found to filter effectively for this variable in the literature. Accordingly, a focus was made of curriculum, policy, pedagogy and assessment. The following search terms were entered as keywords:

(internationalisation OR internationalization OR globalisation OR globalization) AND (university OR college OR ‘Higher Education’) AND (curriculum OR policy OR pedagogy OR assessment).

Three databases were selected for interrogation. The Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC) focuses on educational research and information. Scopus offered a broad span of international research output, books and related publications across a wide range of disciplines, and Scopus includes major sources which might otherwise have been interrogated separately (for example British Education Index, Psychological Abstracts). Google Scholar was selected because of its open-access reach and comprehensive inclusion of diverse sources.

Appraisal of the methodological calibre of research sources is an important criterion for systematic reviews. However, it is also important that an internationally diverse range of literature representative of practice and policy spanning the world is accessed, and with this comes a recognition that there is diversity in research approaches and epistemologies within the global academic community. Therefore, rather than screening for perceived rigour in the style of Global North methodologies and epistemologies, all sources meeting the inclusion criteria, as listed in , were retained for inclusion (Woolf and Hulsizer Citation2019).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The iterative process of screening quickly resulted in two further inclusion/exclusion criteria. Articles published in peer-reviewed journals were included and those lacking peer review were excluded. This was due to a combination of both veracity and availability. English Medium Instruction (EMI) was excluded where it was presented as a stand-alone mode of internationalisation; the exclusion was based on two reasons. Firstly, EMI was presented in the literature wholly as a student recruitment tool, which was an explicit exclusion criterion. Secondly, drawing on the purposes of internationalisation provided by De Wit and Hunter (Citation2015) above, EMI does not in itself enhance quality or create a more meaningful contribution, when the curriculum content remains mono-cultural and unchanged. EMI was included where it represented part of an integrated or wholistic approach to internationalisation (although no records fell into this category).

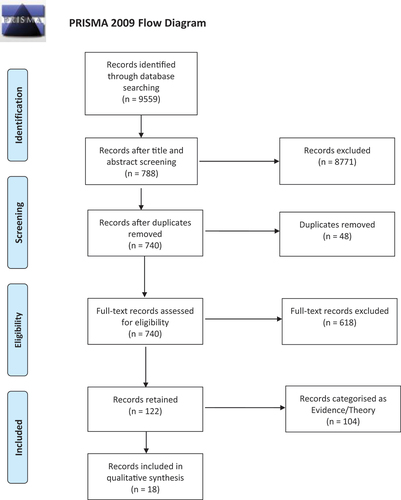

The PRISMA chart () (Page et al. Citation2021) shows a total of 9559 records identified at first extraction. All studies were initially reviewed by a single author and complex cases discussed with the two co-authors until resolution was achieved. In the first round of screening, titles and abstracts were examined according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Each database was examined in turn until 100 consecutive records were excluded, at which point the records were deemed to have reached an irrelevancy to the topic focus. After repeating this process across three databases 788 records were retained and 8771 were excluded. Forty-eight duplicates were removed before further screening, leaving 740 records. In the second round of screening, 740 full texts were examined according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria, resulting in the exclusion of a further 618 records and the retention of 104.

Figure 1. PRISMA chart showing identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion flow of review records.

The predominant themes in the dataset of 104 texts were broad, so a decision was made by the authors to create three subsets of data. This enabled a depth of interrogation of each dataset, drawing on all sources and improving specificity in qualitative synthesis. The first set (‘policy’) comprised records which focused on policy within the intersection of home students and internationalisation (n = 18), and this represents the dataset for this paper. The second set (‘evidence’) comprised records which provided primary data, either qualitative or quantitative and including author-observations. Finally, remaining records which did not provide primary data to support their conclusions but instead discussed theories and secondary data were categorised as ‘theory’. This study reports on the dataset relating to Policy. Occasionally, sources categorised as Policy contained primary data or theory and could also have been categorised as Evidence or Theory, and there is cross-referencing, but these are currently retained within Policy in order to create thematic coherence for the purposes of this paper. Policy, for the purposes of this classification, is defined broadly, as any mandate applying to the approach to internationalisation in the teaching, learning and assessment, whether assigned nationally, institutionally, or departmentally, or even to world regions (for example Europe). The 18 sources included within this systematic literature review are identified in the References List below with an asterisk.

Each source was critically evaluated under the headings ‘main findings and key messages’, ‘limitations’ and ‘how does this fit with the other literature?’. This critical interrogation enabled data analysis. Three themes emerged from this exercise as predominant issues within internationalisation relating to the home student: reasons for internationalisation, collaborations between countries, and issues of policy implementation. It was noted that the topic of ‘policy success’ was completely absent in the literature – no literature on the topic of policy considered whether policy was successful in meeting its goals – and so this gap created a fourth theme.

Regarding the geographic spread of data, records were considered from the standpoint of the population on which each study focused attention, as opposed to author location, based on availability of information. The European subcontinent was represented specifically in five sources, Australasia in four, North America in three, China and Hong Kong in two, and Argentina, Ghana, and Myanmar each in one. There were three sources claiming a worldwide reach. This geographic spread is evaluated later, and Findings are presented with country-context, albeit with acknowledgement that this represents an inaccurate generalisation.

Findings

Three themes emerged as predominant in the intersection between internationalisation policy and home students: purpose, collaboration, and implementation. A further theme, asking whether policy goals are met, emerged as significantly absent in the intersection between internationalisation policy and home students.

Theme 1: why internationalise the experience of ‘home’ students?

Disparities in the reasons for internationalisation within and between nations, institutions and stakeholders were evident (Borkovic et al. Citation2020; Joseph Citation2012). Reasons for internationalisation ranged from the altruistic role education can play in driving the public good, to the economic imperatives which drive competition and create winners and losers. In making sense of the wide range of objectives underpinning internationalisation, three papers devised categories. De Wit (Citation2010) identified political and economic imperatives, and then social, cultural and academic imperatives. Stier (Citation2010) found rationales to be either Instrumentalist (serving a commercial purpose), Idealist (humanitarian), or Educationalist (fostering learning). Maringe, et al. (Citation2013) found three models emerging, based on commerce, culture and curriculum.

Common institutional rationales for curriculum internationalisation focused on fostering critical global citizenship, intercultural understanding, interconnectedness and social justice (Borkovic et al. Citation2020; Joseph Citation2012; Kandiko Howson and Lall Citation2020; Larsen Citation2016; Söderlundh Citation2018; Villar-Onrubia and Rajpal Citation2016). Such objectives underpinning internationalisation could be grouped as desired graduate attributes. Joseph (Citation2012) suggested that the role of universities in providing a public good had declined over past decades, in tandem with the commodification and commercialisation of the educational product. De Wit (Citation2010) observed that internationalisation was often understood to be the ‘last stand for humanistic ideas against the world of pure economic benefits’ (10).

Despite these altruistic aspirations, rationales which understand internationalisation as an economic opportunity for the university in a competitive environment were predominant in the internationalisation policy literature (Buckner and Stein Citation2020; Da Silva Citation2020; Gyamera and Burke Citation2017; Joseph Citation2012; Larsen Citation2016). Exploring the discord between social justice objectives and neoliberal goals, Da Silva (Citation2020) evaluated a Canadian university internationalisation strategy through a Third World Perspective lens. Policy was found to be defined from an economic basis. Lacking pedagogical discussion or acknowledgement of global inequalities, policy was created by the university without engagement from international students, and as a result, marginal knowledges and cultures were not acknowledged in the policy. By delivering only westernised epistemologies and pedagogies, and presenting them uncritically to all students, the implicit message was that of a hierarchy of value between cultures, reinforcing north/south global inequalities.

Theme 2: are there benefits when countries work in partnership?

The alignment of policy between neighbouring states to address internationalisation has been shown to create both positive and negative outcomes. As a positive example, Argentina has been able to circumvent some of the less appealing global trends of internationalisation, such as the imposition of western models of quality assurance and accreditation (Ballerini Citation2017) by partnering with near-neighbouring countries and forming regional policy alliances. World cultures and globally promoted norms can represent a dominant force which interacts negatively with indigenous national contexts and Argentina was less able to withstand the pressures of the Global North until regional alliances created a united identity. In this way, ‘regional’ initiatives were welcome developments for the member states, signalling autonomy, as opposed to passive receipt of global trends initiated elsewhere. They were also able to liaise with dominant international organisations as a stronger cohesive unit and represent their regional interests, and home-student cultures, more effectively.

The European Union also addresses development through regional grouping among neighbouring countries. Suggesting a need for convergence in Quality Assurance, De Wit (Citation2010) envisaged an institutional level of assessment which focused on improvement processes and standardisation ‘to create comparison and best practice’ (21). However, creating convergence across Europe was not welcomed by all member nations, due to loss of localised practices and identities. In Finland, the loss of indigeneity encountered whilst aligning HE to European frameworks is reported as problematic. Historically, in their national education system, Finland prioritised social inclusion; this centred on issues of internal Finnish languages and regions, social and political classifications, and genders (Weimer, Hoffman, and Silvonen Citation2019). For EU membership, historic national values were set aside in favour of international convergence. Weimer describes the uncritical adoption of multiculturalism in HEIs as a form of benevolent othering which suggests inclusion but in fact reinforces hierarchies and difference, for example prioritising use of English as a dominant language and dropping the inclusion of local Finnish languages. Finnish cultural values were sacrificed, to enable uncritical convergence with regional imperatives. Aligned with Argentina’s situation (Ballerini Citation2017), retaining culturally localised knowledge and practice was the key factor in both perspectives.

Theme 3: what are the complexities of putting policy into practice?

Actual evidence of what happens in the classroom which is intended to fulfil the promise of internationalisation policy is extremely sparse. In this section, detailed portraits of ‘what works’ are given, light is shed on the role of inclusivity, and a gap is evidenced between the makers and the implementers of policy.

Two very different sources provided a fine-grained analysis of how curriculum internationalisation was enacted in the classroom with home students – and interestingly both drew the same conclusions. Söderlundh (Citation2018) defined the specific knowledge, understanding and skills underpinning the internationalisation policy in a Swedish university. ‘Knowledge’ was wide-ranging, encompassing knowledge of cultures, religions, international relations and international issues such as energy supply, climate change and international relations, for example. ‘Understanding’ was concerned with seeing ourselves and others in relation to this knowledge, creating self-awareness. ‘Skills’ implied the ability to relate to others, on the basis of the developed knowledge and understanding. Using a Conversation Analysis approach, one classroom case study is considered, and all three aspects of the policy were visible in the social interactions between the lecturer and the students. Söderlundh concludes that the clarity of the policy and the skilful questioning of the teacher facilitate the close coherence between policy and practice.

Villar-Onrubia and Rajpal (Citation2016) also concluded that ‘precise internationalised learning outcomes’ and ‘providing academic staff with relevant resources and training opportunities’ (81) were the enablers for policy to lead to meaningful internationalisation experiences in the classroom. Their university strategy and policy documents focus on the ‘home’ student, clarifying a commitment to provide internationalisation experiences to all students and in all courses. Policy goals such as progression through international experiences, authentic dialogue, relationship-building and developing abilities to switch between perspectives provided clarity for staff. Objectives for jointly planned syllabi and co-teaching with overseas partner institutions could then be based on these clear goals. Again, policy clarity and staff engagement were reported to be central to coherent implementation.

In Hong Kong, the University Grants Commission policy stated that internationalisation was of central importance and should permeate all institutional activity (Skidmore Citation2012), yet all recommendations related to activities which were actually optional, such as overseas study opportunities, or optional international modules; a student could complete a full undergraduate degree without encountering any aspect of internationalisation (Skidmore Citation2012). Similarly, in Finland it was found that access to specifically internationalised modules was patchy, resulting in unequal access to an internationalised education (Weimer, Hoffman, and Silvonen Citation2019). Where internationalisation activities for home students are all optional then internationalisation itself is optional and not considered to be part of the ‘core academic mission of the university’ (Skidmore Citation2012, 98).

A typical gap was evidenced between policy makers and policy implementers. In a government-commissioned report into the implementation of home student internationalisation policies in Finnish institutions, the agenda was considered centrally important by most of the 125 international officers, student union representatives and research institute personnel questioned. In contrast, the concept was largely unknown by the 764 academic staff in four institutions who were responsible for implementing the policy. Similarly, in Ireland, lecturers were willing to internationalise their teaching for home students but were largely unaware of the policy requirement to do so and expressed a limited understanding of the concept of internationalisation (Ryan et al. Citation2020).

A range of other implementation complexities were represented in the literature. In Canada, students reported that when international perspectives were given space it was from a derogatory point of view, giving outdated cliches, stereotypes and misinformation, portraying the Global South in a negative light (Guo and Guo Citation2017). In an Australian case study, university governance perceived fees-generating and status-building aspects to be the indicators of internationalisation, whereas academic faculty perceived intercultural capacities, inclusion and transformative pedagogies to be the indicators of internationalisation (Joseph Citation2012). Leask and Bridge (Citation2013) reported that lecturers in Australia were heavily embedded in their own discipline models of best practice and accredited approaches, so it was difficult for them to genuinely approach alternative disciplinary perspectives openly. On the other hand, also in Australia (and New Zealand), policy documents from 48 universities evidenced a policy focus on global citizenship for the personal development of all students and the good of society, but Discourse Analysis revealed that implementation was entirely dominated by an orientation towards the personal competitive advantage to be gained by engagement with internationalisation initiatives (Borkovic et al. Citation2020).

Enabling factors for policy and practice to align were clarity in policy aims, skilful pedagogies, and for internationalisation to be an integral part of core learning for all students as opposed to an optional bolt-on. The complexities of putting internationalisation policy into practice naturally lead to questions of outcomes, and discourses of policy success were notable for their absence in this policy literature. Whether policies are ‘successful’ is addressed in the final theme.

Theme 4: is internationalisation policy successful?

Moving from the classroom level through national policy, international policy, and even worldwide professional associations, commentary on whether policy relating to the home student meets its goals is absent.

From a classroom-based perspective, Söderlundh (Citation2018) and Villar-Onrubia and Rajpal (Citation2016) both reported positively on policy implementation experiences. Söderlundh observed classroom activities and interactions which aimed to meet the policy requirements (the ability to interact with others from different cultures with an understanding of values, histories, biases and cultural self-awareness). Similarly, Villar-Onrubia and Rajpal (Citation2016) explicitly identified key capacities and qualities from their policy which staff were attempting to foster (respect, self-awareness, other perspectives, listening, adaptation, relationships, and cultural humility). Neither study suggested how we could know whether students had developed these abilities, capacities and qualities. How can the success of the policy be measured? Teaching aimed towards this type of learning cannot be assumed to be automatically successful (Villar-Onrubia and Rajpal Citation2016) yet in both these classroom-based studies where policy implementation was being examined, there was no means to evidence whether the aligned learning had taken place.

National policy narratives also avoid defining success. Weimer et al. (Citation2019) highlighted a need for ways to measure the competences gained by students, but without any suggestion of what ways these may be. Leask and Bridge’s (Citation2013) Australia-wide study also concluded that there remained a need to examine the actual impact on students.

De Wit (Citation2010) examined the potential need for a European Standard of internationalisation, and while he was clear that internationalisation at home should be valued as much as student mobility, the sections of his report on measurement only support the measurement of student mobility and institutional structures. He gives an explanation that measuring student learning would be difficult to administrate. A general lack of interest in the impact for students is similarly reported in a broad study of 16 universities across Sweden, the US, Canada and Australia, and the Bologna Process (Stier Citation2010). Results were typically considered in terms of structures and formalities being put in place, rather than student learning outcomes.

Buckner and Stein (Citation2020) take a broader perspective, examining internationalisation policies of three leading HE professional associations through Discourse Analysis. The professional associations were NAFSA: Association of International Educators, the International Association of Universities, and the European Association of International Education. It was noted that all three included home student internationalisation in their priorities (among a wide range of student mobility operations). Policy was vague, mentioning impact, skills and attitudes, but lacked any suggestion of what should be taking place and how it could be evidenced. When it came to evaluating success, what was measured were only the activities being carried out at an institutional level to support student mobility (Buckner and Stein Citation2020). In general, the study finds that all three organisations were similar: de-politicised and de-historicised, with little attention given to enhancing the students’ understanding of real internationalisation issues of diversity, ethics, or power. Outcomes in reality would be considered likely to lead to perpetuation of global inequalities and reification of cultural dominances, as a result of uncritically applied neoliberal approaches to internationalisation (Buckner and Stein Citation2020).

Discussion

Three areas of discussion follow, based on the findings: rationales underpinning internationalisation, which voices are participating in the dialogue, and policy coherence.

Rationales underpinning internationalisation

When actions implemented by institutions are measured, but student learning outcomes are not, curriculum internationalisation is in danger of becoming an end in itself, rather than a means to an end. There was no evidence in the literature of internationalisation having an impact on student learning, and without consensus on the underpinning rationale for internationalisation, success was impossible to quantify.

Rationales underpinning curriculum internationalisation which sit well ethically in the Global North include the appreciation of, and active engagement with, cultural difference. The incorporation of internationally inclusive dimensions is valued. However, it is apparent that in post-colonial institutions and the Global South these policy ideals can be at odds with understandings of Higher Education’s true purpose of the ‘public’ good (Ballerini Citation2017; Gyamera and Burke Citation2017; Kandiko Howson and Lall Citation2020). Retaining the local or ‘indigenous’ aspects of curriculum and focusing on local languages and local professional practices can be problematic in post-colonial contexts where the standards, practices and epistemologies risk being viewed as holding a lower value than an internationalised curriculum; local curricula risk being represented as useful only to perpetuate the status quo in the local community. The alternative is to open the doors to dominant international ideology, epistemology or practice, understood as internationalising and creating desirable outward-looking courses and qualifications, yet this can be experienced as a loss of indigenous knowledge and practices rather than a public good (Ballerini Citation2017; Kandiko Howson and Lall Citation2020). Examples can be seen in the courses which are delivered in English at the expense of local languages (Kandiko Howson and Lall Citation2020) or qualifications geared towards European standards for exports or engineering, at the expense of local needs and practices (Gyamera and Burke, Citation2017). There is a danger inherent, in that by internationalising, a hierarchy is reinforced which prioritises the languages, cultures, practices and standards of the Global North (Gyamera and Burke Citation2017). Balancing the need for decolonisation alongside the need to be internationally relevant exposes the ‘public good’ as being a context-based concept. The incorporation of internationally inclusive dimensions is not painted in the literature as multiculturalism on an equal footing, but the rising tide of dominant cultures at the expense of diversity.

The Global North’s motives for internationalising are understood in the literature to be largely economic. Offering an internationalised curriculum is seen to afford better graduate outcomes and employability, and therefore institutions which are more ‘international’ are regarded as more desirable, competitive in attracting the best students, and capable of charging the highest fees. The ‘public good’ is not necessarily well served by the reframing of HE as the producer of a competitive commodity. In education, the directional flow of people, knowledge and capital are associated with historical hierarchy and inequality (Marginson Citation2006). Pressure to compete for the best students and perform comparatively with other universities on the global stage sets richer and poorer countries in historic roles and can be seen to perpetuate symbolic inequalities. For example, British education being framed as an ‘asset’ creates an understanding of international students as ‘beneficiaries’ (Hayes and Cheng Citation2020, 350), exposing the lack of democratic positioning and participation. There are repeated intimations throughout the literature that what students are learning is the role of HE in reinforcing competitive ideologies and dominant global inequalities (Borkovic et al. Citation2020; Buckner and Stein Citation2020; Da Silva Citation2020; Hayes and Cheng Citation2020; Marginson Citation2006; Pashby and de Oliveira Andreotti Citation2016; Stier Citation2010).

Which voices are participating in the dialogue?

The range of voices engaged in the academic debate on curriculum internationalisation policy reflects inequalities and exacerbates representation. The European subcontinent was represented specifically in five sources, Australasia in four, North America in three, China and Hong Kong in two, and Argentina, Ghana, and Myanmar each in one. There were three sources ostensibly carrying a worldwide reach (Buckner and Stein Citation2020; Maringe, Foskett, and Woodfield Citation2013; Stier Citation2010) but this deserves further examination.

Stier (Citation2010) examined policy across the EU, Australia, Canada, Sweden and the US, resulting in a focus which exclusively draws on powerful Global Northern perspectives. Similarly, Buckner and Stein (Citation2020) interrogated internationalisation policies of three leading HE professional associations, justifying the choice thus: ‘Combined, these three organizations represent major sources of ideas about internationalization and the professional advocacy networks that define best practices’ (153). Of these three organisations, one is North American, one is European, and the third is predominantly populated by institutions in the Global North. In their concluding remarks on the inequalities and dominant paradigms exposed through their discourse analysis, Buckner and Stein raise the question of whose voices are at the table. Obviously, having only included the most wealthy and powerful Global North organisations, and having defined them as being the ones who ‘represent major sources of ideas’ and ‘define best practices’ (153), the voices at the table are those holding the power. The construction of a similar research project, designed to also include international associations which are not standing within the Global North (such as those of ASEAN or the African Union), would present an opportunity to move research beyond the traditional dominant paradigms and gain a more globally representative understanding of ideas and definitions of best practice. In the Global North scholars are not free of their epistemologies and are therefore not well placed to offer answers about how to break out of them; wanting to repair the situation and regain clarity is our Westernized way of doing and fixing, and needs to be challenged as a further offence (Stein Citation2017).

Maringe et al.’s (Citation2013) survey, conversely, is extensive in global coverage, and has the aim of creating world-region comparisons regarding understandings and priorities about internationalisation in Higher Education. Whilst this longitudinal study uncovers significant information about globalisation and student mobility, only one very small aspect of a survey question relates to the internationalisation of the curriculum for home students. As a result its contribution to this literature is minor. Nonetheless, it is extraordinarily valuable in bringing all voices to the table and demonstrates an inclusive model to engage world regions.

Another group of voices which are conspicuously absent from the literature are those of international organisations which influence and fund HE policy worldwide. For example, the World Bank is the world’s largest funder of education (Shahjahan Citation2012), and is also impactful in advising on international policy. Whilst the World Bank has 194 member nations, indicating a broad reach, a nation’s financial input determines its voting powers and so the wealthier nations are empowered to more decision-making than their poorer counterparts (Shahjahan Citation2012) and this is significant in the policymaking arena. Other influential examples would be OECD and UNESCO. In this systematic literature review, positional papers or scholarly responses to policy emanating from such international organisations were not encountered, and this suggests there are significant players who are not currently part of the research conversation.

Policy coherence

The need for a means of measuring internationalisation is evident – and measuring what students are actually learning, as opposed to what actions institutions are taking (Brandenburg and De Wit Citation2011; Buckner and Stein Citation2020; Deardorff, Pysarchik, and Yun Citation2009; Hayes and Cheng Citation2020; Stier Citation2010; Weimer, Hoffman, and Silvonen Citation2019). Part of the issue appears to be a lack of suitable instruments to measure meaningful internationalisation and the related graduate attributes. But how to create a measuring tool when we are not sure what we are trying to measure? There is a danger of focusing only on those outcomes which are quantitative (De Wit and Hunter Citation2015), and quantitative outcomes do not sit well with the widely accepted purposes identified through the Delphi Panel – namely enhancing the quality of education, and making a meaningful contribution to society (De Wit and Hunter Citation2015).

The successful internationalisation of the curriculum requires a coherence in policy which was missing from the literature in this review – a coherence involving a clear thread of intention which runs from national policy through institutions and teachers and impacts the learning outcomes of the individual students (Garam Citation2012; Weimer, Hoffman, and Silvonen Citation2019). Fragments of this are visible, such as Söderlundh (Citation2018), and Villar-Onrubia and Rajpal (Citation2016), showing policy-into-practice at classroom level, but a connection between policy and student learning outcomes is not demonstrated as a coherent thread in the literature.

Limitations and strengths

The strengths of this paper are that it defined its area of investigation clearly as ‘home’ students and internationalisation policy which relates specifically to them, and then conducted a replicable systematic review which specified search terms, databases, and inclusion criteria. A number of limitations impact on the paper.

One limitation is that this review spotlights scholarly responses to policy at the exclusion of other literature. This means that policy itself, from different countries and institutions is not included. A larger scale study could have investigated examples of policy, although the diversity of policies and approaches even within an institution would create a great deal of complexity. The inclusion of policy would impact on the systematic, world-wide and rigorous nature of the study. Another limitation is the exclusion of texts not written in English. This is solely due to the capabilities of the researchers. English is the predominant language for academic publications, but undoubtedly points towards a Westernised bias (Collyer Citation2018). On reflection it would have been preferable to include sources in other languages, as many reasonable translation tools are available, and this could help to mitigate against cultural bias. In reality, no relevant literature in other languages was encountered in the search, presumably due to the limitation of databases selected.

English Medium Instruction (EMI) could also be perceived to be an area of exclusion which represents bias in the Findings. After Student Mobility, EMI represented the largest area of exclusion of literature. A number of rationales supported the decision. EMI was largely represented in the excluded literature as a student recruitment, status and associated course pricing tool (for example Coleman Citation2006; Nguyen, Hamid, and Moni Citation2016; Rose and McKinley Citation2018). Where the course remained unchanged and not ‘internationalised’ in any way except through the delivery language, students would not be presumed to have been exposed to internationalised content or perspectives. However, this interpretation is open to debate. A further rationale sees EMI as opposing internationalisation. Where the dominance of English increases as the language for education and knowledge, it does so at the expense of local languages and further restricts their emergence in the discourse (Coleman Citation2006; Maringe, Foskett, and Woodfield Citation2013). English Medium Instruction represents a unifying linguistic goal which could be understood to reinforce westernised dominance and close down a multicultural and inclusive curriculum. Again, the reality in practice is open to debate.

At the inclusion/exclusion screening stage, the concept of the ‘non-mobile’ or ‘home’ student proved particularly slippery. Papers which claimed to be focused on curriculum internationalisation but only examined student mobility were highly prevalent. Three of the sources which were eventually included could still be questioned as to whether they were actually addressing the ‘home’ student at all. Their focus was so unclear that they could not be ruled out completely and so they were retained (Ballerini Citation2017; Maringe, Foskett, and Woodfield Citation2013; Skidmore Citation2012); however their contribution could be regarded as a limitation in terms of the thorough application of inclusion criteria.

Implications for future research

There is a need for international organisations, as significant funders of HE and influential powers behind policies, to be present in the scholarly discussions. Where their power and voting systems are skewed towards the Global North, this is even more important; in considering internationalisation, of all topics, no voices should be excluded from the table. Linked to this, clarity on what role Education could, and should, play in the formation of connection and harmony between nations, would be an important area for policymakers and representatives of nations to explore. The paucity of literature on how internationalisation policy intersects with the (majority) ‘home’ student would show where a focus needs to lie.

Conclusions

This systematic review examined the intersection between internationalisation policy in Higher Education, and the students who undertake Higher Education within their own country. Reasons for internationalisation tended to be either altruistic, aiming for harmony between nations, or else commercial, aiming to compete and to profit. Policy collaborations between world regions were helpful when they enabled indigeneity and provided a protective buffer against incoming dominant forces but could also result in a sense of loss where national indigeneity is sacrificed to enable regional alignment. There were difficulties in translating policy into practice because the aims and goals were unclear. Only the actions were measured, not the outcomes. As a result, policy success could not be quantified; no literature on student learning outcomes was forthcoming.

Creating balance between indigeneity and multiculturalism, and between economic needs and idealist hopes, is a challenge for policy makers and implementers which does not appear to have a satisfactory solution yet. We might benefit more from cooperation than from competition. The world’s biggest problems (poverty, climate change, food supply) cannot be solved by one nation working alone but require international collaboration. There is the opportunity for Higher Education to be a space for internationalisation to take root, and to drive globalisation, rather than be driven by it.

If we agree that education is at the centre of all social change, new approaches to educational policy and process are then needed, because without education there can be no change in mentalities and society. And without a change in paradigm for international relations, there can be no solidarity among nations. (Gacel-Ávila Citation2005, 122)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Altbach, P. G. 2003. “Globalization and the University: Myths and Realities in an Unequal World.” Journal of Educational Planning and Administration 17 (2): 227–247.

- Ballerini, V. 2017. “Global Higher Education Trends and National Policies: Access, Privatization, and Internationalization in Argentina.” Policy Reviews in Higher Education 1 (1): 42–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2016.1245113

- Beelen, J., and E. Jones. 2015. “Europe Calling: A New Definition for Internationalisation at Home.” International Higher Education Special 83 (83): 12–13. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2015.83.9080.

- Borkovic, S., T. Nicolacopoulos, D. Horey, and T. Fortune. 2020. “Students positioned as global citizens in Australian and New Zealand universities: A discourse analysis.” Higher Education Research & Development 39 (6): 1106–1121. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1712677

- Brandenburg, U., and H. De Wit. 2011. “The End of Internationalization.” International Higher Education (62). https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2011.62.8533.

- Buckner, E., and S. Stein. 2020. “What Counts as Internationalization? Deconstructing the Internationalization Imperative.” Journal of Studies in International Education 24 (2): 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315319829878.

- Coleman, J. A. 2006. “English-Medium Teaching in European Higher Education.” Language Teaching 39 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480600320X.

- Collyer, F. M. 2018. “Global Patterns in the Publishing of Academic Knowledge: Global North, Global South.” Current Sociology 66 (1): 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116680020.

- Crowther, P., M. Joris, M. Otten, B. Nilsson, H. Teekens, and B. Wächter. 2000. Internationalisation at Home: A Position Paper. Amsterdam: European Association for International Education.

- Da Silva, V. A. B. 2020. “A Critical Discourse Analysis of the University of Ottawa’s Internationalization Strategy Report from a Third World Perspective.” Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy 193:49–62.

- De Wit, H. 2010. “Internationalisation of Higher Education in Europe and Its Assessment, Trends and Issues.” Nederlands Vlaamse Accreditati Organisatie. Accessed August 16, 2022. http://www.obiret-iesalc.udg.mx/sites/default/files/adjuntos/internationalisation_of_higher_education_in_europe_de_wit.pdf.

- De Wit, H. 2014. “The Different Faces and Phases of Internationalisation of Higher Education.” In The Forefront of International Higher Education. HE Dynamics, edited by A. Maldonado-Maldonado and R. Bassett. Vol. 42. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7085-0_6.

- De Wit, H., and P. G. Altbach. 2015. “Internationalization in Higher Education: Global Trends and Recommendations for Its Future.” In HEin the Next Decade: Global Challenges, Future Prospects, edited by H. De Wit, F. Hunter, L. Howard, and E. Egron-Polak, 303–325. Netherlands: Brill.

- De Wit, H., and F. Hunter. 2015. “The Future of Internationalization of Higher Education in Europe.” International Higher Education (83): 2–3. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2015.83.9073.

- Deardorff, D., D. T. Pysarchik, and Z. S. Yun. 2009. “Towards effective international learning assessment: Principles, design and implementation.” In Measuring Success in the Internationalisation of Higher Education, edited by H. de Wit, Vol. 22, 23–38. EAIE Occasional Paper 22.

- European Commission. 2013. “‘European Higher Education in the world’ Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions.” Brussels, July 11. Accessed September 11, 2022. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2013:0499:FIN:en:PDF.

- Gacel-Ávila, J. 2005. “The Internationalisation of Higher Education: A Paradigm for Global Citizenry.” Journal of Studies in International Education 9 (2): 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315304263795.

- Gacel-Ávila, J. 2012. “Comprehensive internationalisation in Latin America.” HE Policy 25 (4): 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2012.9.

- Garam, I. 2012. Faktaa. Facts and Figures. Internationality as Part of Higher Education Studies. Helsinki: Centre for International Mobility.

- Guo, Y., and S. Guo. 2017. “Internationalization of Canadian Higher Education: Discrepancies Between Policies and International Student Experiences.” Studies in Higher Education. 42 (5): 851–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1293874.

- Gyamera, G. O., and P. J. Burke. 2017. “Neoliberalism and curriculum in Higher Education: A post-colonial analyses.” Teaching in Higher Education. 23 (4): 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1414782.

- Harrison, N. 2015. “Practice, Problems and Power in ‘Internationalisation at home’: Critical Reflections on Recent Research Evidence.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (4): 412–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1022147.

- Hayes, A., and J. Cheng. 2020. “Liberating the ‘Oppressed’ and the ‘Oppressor’: A Model for a New TEF Metric, Internationalisation and Democracy.” Educational Review 72 (3): 346–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1505713.

- Joseph, C. 2012. “Internationalizing the curriculum: Pedagogy for social justice.” Current Sociology. 60 (2): 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392111429225

- Kandiko Howson, C., and M. Lall. 2020. “Higher Education Reform in Myanmar: Neoliberalism versus an Inclusive Developmental Agenda.” Globalisation, Societies & Education 18 (2): 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2019.1689488.

- Knight, J. 2002. “Trade Talk: An Analysis of the Impact of Trade Liberalization and the General Agreement on Trade in Services on Higher Education.” Journal of Studies in International Education 6 (3): 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/102831530263002.

- Knight, J. 2008. Higher Education in Turmoil: The Changing World of Internationalization. Netherlands: Brill.

- Kritz, M. M. 2006. “Globalisation and Internationalisation of Tertiary Education.” In International Symposium on International Migration and Development: contested consequences. Final Report submitted to the United Nations Population Division. Ithaca, New York.

- Lane, J. E., T. L. Owens, P. Ziegler, K. Hermann, J. Lansing, D. Salto, R. Sun, and G. Zambrano 2014. “States go global: State Government engagement in Higher Education Internationalization. Rockefeller Report.” Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government. New York.

- Larsen, M. A. 2016. “Globalisation and Internationalisation of Teacher Education: A Comparative Case Study of Canada and Greater China.” Teaching Education. 27 (4): 396–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1163331

- Leask, B. 2009. “Using Formal and Informal Curricula to Improve Interactions Between Home and International Students.” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (2): 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315308329786.

- Leask, B. 2015. Internationalizing the Curriculum. New York: Routledge.

- Leask, B., and C. Bridge. 2013. “Comparing Internationalisation of the Curriculum in Action Across Disciplines: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. 43 (1): 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.746566

- Li, J. 2018. “Endogenous Complexity and Exogenous Interdependency: Internationalization and Globalization of Higher Education.” In Conceptualizing Soft Power of Higher Education. Perspectives on Rethinking and Reforming Education, edited by J. Li. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0641-9_2.

- Marginson, S. 2006. “Dynamics of National and Global Competition in Higher Education.” Higher Education 52 (1): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-7649-x.

- Maringe, F., N. Foskett, and S. Woodfield. 2013. “Emerging Internationalisation Models in an Uneven Global Terrain: Findings from a Global Survey.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. 43 (1): 9–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.746548.

- Mittelmeier, J., S. Lomer, S. Al Furqani, and D. Huang. 2022. Internationalisation and students’ Outcomes or Experiences: A Review of the Literature 2011-2021. Manchester: University of Manchester. https://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/publications/internationalisation-and-students-outcomes-or-experiences-a-review.

- Nguyen, H. T., M. O. Hamid, and K. Moni. 2016. “English-Medium Instruction and Self-Governance in Higher Education: The Journey of a Vietnamese University Through the Institutional Autonomy Regime.” Higher Education 72 (5): 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9970-y.

- OECD (Organisation for European Cooperation and Development). 2022. International Student Mobility. Accessed November 3, 2022. https://data.oecd.org/students/international-student-mobility.htm.

- Page, M. J., J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, L. Shamseer, et al. 2021. “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews.” Systematic Reviews 10 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4.

- Pashby, K., and V. de Oliveira Andreotti. 2016. “Ethical Internationalisation in Higher Education: Interfaces with International Development and Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 22 (6): 771–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1201789.

- Rose, H., and J. McKinley. 2018. “Japan’s English-Medium Instruction Initiatives and the Globalization of Higher Education.” Higher Education 75 (1): 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0125-1.

- Ryan, D., F. Faulkner, D. Dillane, and R. V. Flood. 2020. “A Situational Analysis of the Current Level of lecturers’ Engagement with Internationalisation of the Curriculum in Ireland’s First Technological University.” Irish Educational Studies. 39 (1): 101–125. . https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2019.1663551

- Shahjahan, R. A. 2012. “The Roles of International Organizations (IOs) in Globalizing Higher Education Policy.” In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, edited by J. Smart and M. Paulsen. Vol. 27. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2950-6_8.

- Skidmore, D. 2012. “Assessing Hong Kong’s Blueprint for Internationalising Higher Education.” The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives 11 (2): 81–101.

- Söderlundh, H. 2018. “Internationalization in the Higher Education Classroom: Local Policy Goals Put into Practice.” Journal of Studies in International Education. 22 (4): 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318773635

- Stein, S. 2017. “The Persistent Challenges of Addressing Epistemic Dominance in Higher Education: Considering the Case of Curriculum Internationalization.” Comparative Education Review 61 (S1): S25–S50. https://doi.org/10.1086/690456.

- Stensaker, B., N. Frølich, Å. Gornitzka, and P. Maassen. 2008. “Internationalisation of Higher Education: The Gap Between National Policy‐Making and Institutional Needs.” Globalisation, Societies & Education 6 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767720701855550.

- Stier, J. 2010. “International Education: Trends, Ideologies and Alternative Pedagogical Approaches.” Globalisation, Societies & Education. 8 (3): 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2010.505095

- Villar-Onrubia, D., and B. Rajpal. 2016. “Online International Learning: Internationalising the Curriculum Through Virtual Mobility at Coventry University.” Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education. 20 (2–3): 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2015.1067652

- Weimer, L., D. Hoffman, and A. Silvonen. 2019. “Internationalisation at Home in Finnish Higher Education Institutions and Research Institutes.” Opetus-ja Kulttuuriministerio. Accessed August 16, 2022. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/161606/OKM_2019_21_Internationalisation_at_Home.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y.

- Woolf, L. M., and M. R. Hulsizer. 2019. “Infusing Diversity into Research Methods= Good Science.” In Cross‐Cultural Psychology: Contemporary Themes and Perspectives, edited by K. D. Keith, 107–127. John Wiley & Sons.

- Zou, T. X., B. C. Chu, L. Y. Law, V. Lin, T. Ko, M. Yu, and P. Y. Mok. 2020. “University teachers’ Conceptions of Internationalisation of the Curriculum: A Phenomenographic Study.” Higher Education 80 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00461-w.