Abstract

For colonial troops from the British Empire, the military mobilizations of the First World War created the opportunity to visit the imperial metropolis – London – leaving the war behind. This article explores the experience and encounters of New Zealand's soldiers in London during the First World War and the ambiguity of their identity and belonging in a city that could be positioned as ‘home’. Using diaries, letters, newspapers and oral testimonies, the article builds on the work of Felicity Barnes to question the extent to which these colonial troops could feel at ‘home’ in the ‘Big City’, inside and outside the familiar space, to explore colonialism's tensions in a global war.

Introduction

There is one thing; I am getting round the world on the cheap and seeing plenty of places.Footnote1

Writing home to New Zealand, Henry Kitson reflected on being both soldier and tourist during the First World War (Figure ). The men mobilized in this global conflict from throughout the British Empire had the opportunity to explore places that they had never been to before, some replicating the journeys between colony and metropole made by thousands prior to war's outbreak.Footnote2 British bases for deployment on the Western Front and other fronts necessitated an empire come ‘home’. London, as the metropolis, experienced an influx of troops on leave, adding to its existing colonial milieu, who in intense bursts explored the city made familiar through novels, picture postcards, cigarette cards, magazines, photograph and film.Footnote3 In diaries, letters, postcards and photographs, the combatants and non-combatants from the British Empire articulated and described their experiences of ‘arriving’ in the ‘Big City’, a marker of success and achievement, as well as freedom from the war and the practice of behaviour more positive and comprehensive, both to the men and to their families reading at home. As one Private Gray expressed,

The sense of freedom from army restraint is a thing you can never comprehend until you have been under the yoke, and are set free, even for a day. I had forgotten about the war. This was London, and it was my innings.Footnote4

60,000 soldiers from New Zealand passed through the capital during the First World War, alongside Australians, Canadians, South Africans, Indians, West Indians and others from the British Empire.Footnote5

The purpose of this article is to explore the experience and encounters of New Zealand's soldiers in London during the First World War and the ambiguity of their belonging in a city that could be positioned as ‘home’. Work by Felicity Barnes has suggested a form of ‘cultural co-ownership’ between New Zealand and London. The metropolis was constructed and appropriated by New Zealanders during this period and beyond to minimize the colony's peripheral status and Barnes argues that by the twentieth century, New Zealanders ‘took physical, not phantom, form as ‘Britons’ ‘at home’ in their imperial metropolis’, exemplified by soldiers in the city during the First World War.Footnote6 I build on Barnes’ study and add nuance by exploring disconnects between the soldiers’ imagined template of the metropolis and their represented experience of it. Rather than being at ‘home’, accounts by New Zealanders in London reveal their position as visitors and an ambiguous status as insiders and outsiders in the imperial, urban space.

Certainly, for the white dominions with family networks that linked centre and periphery, London ‘was the locus of inherited cultural memory, the site of ancestral connections, and the setting of major historical episodes.’Footnote7 For those from the colonies who were yet to ‘come home’, they were able to ‘know’ London through the vehicles of imperial propaganda and popular culture which permeated the Empire. Imperial exhibitions in the metropolis, as one example, were reported on throughout the Empire and frequently travelled to the colonies. New Zealand hosted touring exhibitions in 1865 and 1906–1907.Footnote8 For those New Zealanders who did not see the 1911 Pageant of London in person, newspapers reported upon it as part of the coverage of the Festival of Empire, with the depiction of London as the heart of the British Empire, ‘essential in the acquisition of overseas territory, and as the metropolitan centre where colonial inhabitants came to be “at home”.’Footnote9 These cultural productions were part of the complex relationship that positioned New Zealand as a ‘hinterland’ to the metropolis rather than its periphery.Footnote10

Yet, the arrival of white dominion peoples in the metropolis raised important questions about the status of these colonial subjects. Angela Woollacott has outlined how white colonials ‘reveal simultaneously the privileged foundations to whiteness and the subordination inherent to colonial status.’Footnote11 While the ‘“invisible” normativity’ of whiteness allowed New Zealanders or Australians to travel through the city without being racially discriminated against, their colonial status could separate them from the city, and English people could hold white colonials as less ‘civilized’.Footnote12 Woollacott utilizes the work of Paul Gilroy to think about the ‘inside/outside’ relationship through which, despite the higher position of the white dominions in the racial hierarchy, these people could be ‘tainted’ by their upbringings in a colonial setting, on the frontiers of empire rather than at its centre.Footnote13 Woollacott works on the experience of women, further subordinated by gender, so the privilege of masculinity must be taken into account. Yet, it is productive to place the white New Zealand soldiers in their colonial context and reconsider the ambiguity of their status. By placing white New Zealand accounts in conversation with Maori representations of time in the capital in the final section, I begin to think more laterally about colonial experiences of London during the war. The article begins by examining how white New Zealand soldiers could be seen to appropriate London's spaces before turning to representations of encounters between troops and city that reinforced differences in identity. I then ask how more ambiguous status affected sexual activity in the city, before bringing in Maori representations of time in London.

Touring the city: mapping New Zealand's London

Why have New Zealand's soldiers been seen to be at ‘home’ in London during leave? Here, the systems that created ‘home’ – guidebooks and soldiers’ organizations – are examined. First, though, we must understand the soldiers’ ability to be tourists in London. While work on the soldier as tourist, particularly by Australian historians, has complicated the degree to which the analogy can be used, the representation by the men of their sightseeing rendered war a sideshow; to echo Gray, he had ‘forgotten about the war’.Footnote14 Bart Ziino's work demonstrates that soldiers held parallel identities: aware of the war they were caught up in but full of desire to explore their destinations when on leave, before finally reaching home.Footnote15 Tourism became part of how the troops represented their war experience, and the simultaneity of being soldier and tourist allowed them to make the most of these opportunities.

London was a site of cultural interaction between the New Zealanders and the city. Yet, it is difficult to trace what shaped individual soldiers’ expectations of the metropolis. Most wrote home during or at the end of their stay in ‘the Big Smoke’, rather than in anticipation. Edward Ryburn's diary reveals how hearing others’ experiences could influence the eagerness of the men to visit London. He was envious of an acquaintance whose injury had taken him to England, and wrote in August 1915,

Ever since (he) has been having all sorts of a time in England - England mind you…He made me frightfully envious with his tales of sight seeing, being entertained by titles etc., and he said a colonial simply couldn't help having a good time.Footnote16

Ryburn's appetite for the ‘colonial’ experience of England was whetted, though we know little about what precisely he yearned for. The Colonial's Guide to London written especially for ‘Overseas Visitors, Anzacs, Canadians and all other soldiers of the Empire’ by A. Staines Manders, offered clearer direction for those awaiting leave in the metropolis.Footnote17 James Curran describes guidebooks for Australian troops in Paris as ‘objective, informative and compact… the medium through which the magnitude of Paris could be miniaturized’.Footnote18 Guidebooks enabled the soldiers to access a knowable version of the city, aiding planning and preventing the user from becoming overwhelmed.Footnote19 For New Zealand troops, the particular version of London offered in guidebooks like The Colonial's Guide made the city easier to navigate, maintaining London's familiarity.

A prime aim of the guidebook was to instil in the tourist the historic significance of the sights.Footnote20 The Colonial's Guide directed the visiting troops towards the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey and St Paul's, encouraging a sense of shared history. Manders was clear that it is ‘Old London that the overseas visitor most desires to know and understand.’Footnote21 These sights ‘appeal to the imagination of the peoples of the Dominions as no novelty however brilliant can appeal. For these are theirs and ours, and in the shadow of the Abbey or the White Tower, we are Londoners all.’Footnote22 The sights of ‘Old London’ were the emblems of empire and the past shared by the metropolis and her colonies. London excited identification.

The guides’ mapping of knowable London formed the basis for many expeditions by visiting New Zealand troops, as represented in their letters and diaries. Albert Bousfield remembered having ‘a good look around and have seen most of the principal sights: Houses of Parliament, Westminster Abbey, Tower of London, Kings Stables, Buckingham Palace, Waxworks and Zoo.’Footnote23 Harry O'Donnell Bourke

visited the Tower, St Pauls in the morning, and Westminster and the King's stables at Buckingham Palace in the afternoon. We had a lady guide, who pointed out the buildings and places of interest as we went along. It cost us four shillings a head for the trip, and was well worth it.Footnote24

Guided tours, run by organizations like the New Zealand War Contingent Association, were ‘directed towards keeping the men in a healthy and cheerful atmosphere’.Footnote25 Tours, alongside the guidebooks’ daily itineraries, could direct the soldier's attention away from ‘disreputable London’ as well as reinforcing the version of London that existed in the peripheral imagination.Footnote26 The men saw London specifically in its historic sights of imperial significance, spaces of pageantry, power, religion and (imperial) knowledge. Alfred Olsson, who wrote home in June 1917 that London was ‘the world's greatest city’, similarly echoed this sentiment:

What I consider the most magnificent building I have ever seen is St Paul's Cathedral, which as also does Westminster Abbey (where I attended an afternoon service) contains the remains of so many of England's most famous dead.Footnote27

John Moloney was even more explicit about the symbolism of Westminster Abbey:

Its beauty is typical of English culture and English customs have been a heritage to the Empire, the value of which will be seen as the years pass. The thousands of colonial soldiers who will visit this shrine must be impressed with the majesty and wonder of the country under whose colours they have travelled so far to fight.Footnote28

London was home to a heritage that spanned beyond the British people. It was where empire had been founded and developed and in doing so, the colonies and dominions had become part of this shared past as well as the future. By accessing these sights, the sense of cultural co-ownership promoted by the Colonials’ Guide became apparent as a reality within these New Zealander accounts. As Barnes has reflected, the reinforcement of London as a centre of heritage occurred ‘not only in situ, but through the transmission of their experiences back to New Zealand in letters, postcards, photographs and stories’ and therefore in the peripheral imagination as well.Footnote29 By the mapping and remapping of familiar London through the occupation of its space and seeing the historic sights, the New Zealand soldiers maintained the links between centre and periphery, and shortened the imagined space between the two. How exclusive this experience was to the white New Zealanders remains to be seen.

In examining how official bodies such as the New Zealand High Commission attempted to make the visiting troops at ‘home’ in London, Barnes points to the establishment of soldiers’ clubs and residences, from which the men could then engage in authentic metropolitan living. The use of these clubs is frequently reflected upon in letters and diaries and so prove a useful intersection between attempts to create ‘home’ and the men's responses. The clubs were often nationally defined and funded by individual patrons or organizations like the New Zealand War Contingent Association, taking over large spaces in central and West London. As well as middle class women from London who staffed these clubs, women from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa travelled to the imperial centre to recreate ‘home’. Barnes establishes the club environment as ‘at once a return to an imagined familial home and a reconfiguration of metropolitan experience, with a didactic purpose. The maternal archetype was set against its obverse, the prostitute.’Footnote30 It is true that the men appreciated the comforts made available to them during their time in the city. Albert Bousfield raved about the Anzac Buffet refreshment rooms. ‘These rooms are run by Australian ladies and are absolutely free. We go in any time and have as much as we want and never need to pay a penny.’Footnote31 Francis Healey preferred the Catholic Women's League Hut: ‘one of the best places in London for soldiers as the food is good and very reasonable and the beds are only 8d.’Footnote32 William Malcolm chose the Shakespeare Hut as his accommodation:

No matter when a soldier arrives he can always get a meal. The place was crowded with soldiers on leave. It costs sixpence for a bed. The dormitories were all full as well as a big hall, which was laid down with wire stretchers about 6 inches from the floor.Footnote33

Norman Coop stayed at the Shakespeare Hut too; having arrived into Euston in the early hours of the morning it was one of the few places he could sit by the fire and have a cup of tea. ‘See a digger can get a feed here any time of the day or night, so after breakfast I caught the bus from Russell Square to Waterloo station.’Footnote34 The men's odd arrival times and need for food is a reminder that these were soldiers on leave, rather than just tourists. The troops needed accommodation and sustenance for the brief periods they would spend in the city and the clubs were an affordable way of doing so. They could be used as a ‘home’ base, but there is little reflection by the men that this was a straightforward substitute, beyond their appreciation of the hot food and lodgings. The affordability to enjoy the city during their time on leave dominates, rather than home writ small. Though, as Barnes states, ‘clubs became the physical location and manifestation of New Zealand's home in London’, this was not necessarily how the soldiers’ perceived them.Footnote35 The parallel identities held by the New Zealanders as soldiers and tourists was echoed by a further representative identity as occupiers of London's space, both sightseers and temporary inhabitants, that was much less conscious in how they communicated this experience. While participating in these acts may have seen them ‘at home’, claiming their shared heritage, the simple enjoyment of being on leave is what resonates most strongly in the soldiers’ representations.

Not at ‘Home’? New Zealanders rather than Londoners

If the New Zealand soldiers did not explicitly express their feelings of belonging in London, did they suggest maintaining a sense of colonial or New Zealander identity? Where the Colonials’ Guide fostered a sense of shared history for overseas visitors to London, Manders also created limits on feeling at ‘home’ in the city. The guide advised not to talk too vigorously about New Zealand or other dominions, as well as refraining from making comparisons between London and home, challenging a sense of co-ownership. The guide recommended,

To remember always that Great Britain is a country with a very vital and illustrious past – their past, no less than hers – and at the moment matters so enormously that her influence upon the destiny of the civilised world is incalculableFootnote36

While this was a past that dominion visitors could have a stake in, reminding the visiting colonials to remember their place within the Empire was particularly important at a time of war. The implored, though temporary, surrender of national identity to allow London and Britain to take precedence indicated underlying tensions between being at ‘home’, being colonial and being New Zealanders, both inside and outside.

How would this tension manifest in the represented experience of New Zealand? Though Barnes has pointed to soldiers who were dissatisfied with the sights of the city, she understands an underlying appreciation of the achievement of arriving in London.Footnote37 However, in reading the descriptions of Edward Ryburn of the Otago Regiment, who had so envied his compatriot, the critique runs deeper than disappointment with historic London. As Woollacott highlights, one of the ways ‘Australians represented national identity in London was through their criticism of the city itself and Britain more generally.’Footnote38 Ryburn's criticism is of a similar form. On his first visit, he ticked off ‘all sorts of things so well known by name to us’.Footnote39 Yet he found that ‘these places lose a lot of their romantic interest, I think you could call it, by seeming to fit so naturally into their surroundings. I found this strike me with regards to all the so-called “sights”’.Footnote40 Similarly, on his second visit on 5 October 1916, though ‘it would have been criminal to have missed seeing’ Westminster Abbey, he found the space inside claustrophobic and unfulfilling.Footnote41 Going to Madame Tussauds later in the month, he found it ‘quite a fraud’ in its inauthentic representation of Britain's illustrious history.Footnote42 Disillusioned with war and far from home, the capital's sights did not fulfil his expectations and previous enthusiasm.

But when Ryburn looked for New Zealand in London, his experience was more satisfying. In October 1916, he went to the museums in South Kensington:

Gave it up in the end and I asked one of the numerous bobbies about if they had any Australasian exhibits. Seemed they didn't go in for stuffed animals etc. and he directed us to the Imperial Institute not far away. I wanted to see a bit of N.Z. We found the Institute and found there were exhibits from all the different colonies. Made our way to Australasia and found that the N.Z. exhibit was humiliatingly small. However, there was any amount of interest in what was there and we filled in the morning.Footnote43

Coming to the exhibition allowed him to feel at home in a way that culturally co-owned historic sights of London had not. Despite being upset by ‘the humiliating small’ place his homeland held in the Institute, he was able to spend a whole morning there. The Mother Country's capital was not always enough. Being able to sightsee in London was small compensation for the continuing hardships of military service, an imminent return to the front and the absence of family. The city could not be a direct substitute for ‘home’ life, despite the efforts of guides and clubs. Though the museums had featured on official maps and tours, Ryburn and his friends chose to look for their national identity in their exploration of the city.

Equally, touring London beyond its West, where most of the historic sights were situated, revealed the conflict for the New Zealand soldiers between feeling metropolitan in the metropolis and having their difference from the city reinforced. The geographic binary of East/West in London ‘increasingly took on imperial and racial dimensions, as the two parts of London imaginatively doubled for England and its Empire.’Footnote44 Where the West of the city was a site of modernity and urban development that overwhelmed the imperial visitors – the underground named ‘the limit in wonders’ by Harry Hall – London's East End was its very own colonial periphery in which the white soldiers could adopt a metropolitan superiority and tourist gaze.Footnote45 Areas like Petticoat Lane or Chinatown proved to be of ‘exotic’ interest with their ‘foreign’ populations. These were notorious slum areas – overcrowded, impoverished, with poor sanitation – but the maritime connections made it ‘the most cosmopolitan district of the most cosmopolitan city in Britain.’Footnote46 The Colonial's Guide described ‘knots of men in neat blue suits and smoking aromatic cigars stand in the doorways or about the street corners talking in strange languages – these of the Chinese of Chinatown.’Footnote47 Pennyfields too had its ‘Oriental colony’.Footnote48 By visiting these areas, white New Zealand soldiers could perform a survey of ‘otherness’, turning an imperial gaze back on the centre.Footnote49 Egbert Dredge ‘went down Petticoat Lane and round Whitechapel most of morning and had great deal of fun. Almost foreign quarters’ and his compatriot John McWales was similarly ‘very much amused’ by Petticoat Lane.Footnote50 Harry O'Connell Bourke went further: ‘Bert, Dean and I took a bus to Petticoat Lane and had a look round there. This place is an eye-opener for a colonial, and the people are mostly Jews.’Footnote51 In these areas of ‘amusement’ on the bounds of the metropolis the New Zealanders certainly did assume a metropolitan gaze, amused and beguiled by these areas of ethnic diversity, that could see them positioned as members of the imperial centre. But the identification of ‘foreign’-ness within London, particularly given working-class Londoners lived alongside more recent immigrants to the city in these areas, rendered the city ‘other’ to these colonials, as Bourke considered himself. The observation of the odd sights could form a kind of critique of London itself, once again reasserting national identity. The disconnect between the New Zealanders and London, and New Zealand and London, simultaneously inside and outside, was emphasized by the journey to the city's own periphery.

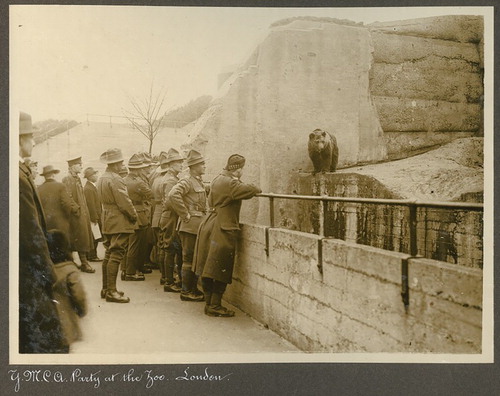

Feelings of ‘home’ in London rested upon the soldiers’ experiences but, also, on how the city itself received them. While clubs and guidebooks aimed to help visiting colonial troops feel at ‘home’, other cultural media emphasized how temporary the presence of the visiting soldiers was in illustrating their difference from London's population. Whiteness and shared British ancestry did not make all the New Zealand soldiers visibly separate from London's white population, an ‘obvious expression of New Zealand's assumed metropolitan-ness’, but their distinctive uniforms worn in the city certainly emphasized their difference.Footnote52 Though they had felt themselves tourists and the war forgotten despite their uniforms, dress was a visible marker of soldiering identity. Photographs of New Zealand soldiers passing through London's streets demonstrated the spectacle created by their presence, including their recognizable ‘lemon-squeezer’ hats (Figure ):

FIGURE 2 World War I New Zealand troops marching in London. Royal New Zealand Returned and Services’ Association: New Zealand official negatives, World War 1914–1918. Ref: 1/2-013808-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22813516.

Similarly, newspaper articles like ‘A Pageant of War’ in The Times described crowds watching detachments from the British Empire parade:

The Australian and New Zealand soldiers, finely built men with alert bronzed faces, swung along cheerfully in the rain, and the South Africans were an equally inspiring body. A company from the West Indian contingent, which included many coloured men, got a specially hearty cheer.Footnote53

There was a form of mutual exchange: the visual novelty of the colonial troops for the sights of the city. As New Zealander John Maguire put it, ‘“London” the big city or the big smoke as every soldier termed it, was wanting to see us and we were wanting to see her.’Footnote54 This article and a similar piece in an American magazine outlined the encounter between the London population and the different ethnic and national groups of the imperial forces.

In the Strand any day there may be seen the Canadian and Australian, the Maori, the South African, sauntering about seeing the sights, either back from France on leave, or perhaps just in from over the world and about to go across the Channel. Now and again, there is an ebony face under the cap of the King's uniform - a soldier from the West Indies, while often there are Indians.Footnote55

The newsworthy presence of the colonials troops enforced how specific this scene was to the wartime context, the troops, both white and black, different from London's already racially diverse population. The troops were presented as an imported phenomenon, reliant on the contingent circumstances of war, who would leave the city once the war was over. While the white dominion troops appear first in this quasi hierarchy of empire – the men of colour from the West Indies and India being further separated – they are still part of the empire, ‘colonials’, and national and ethnic stereotypes were deployed in describing them. The New Zealand soldiers were just one group among many who had come to assist the ‘Mother Country’ in its time of need. In ‘The Tall New Zealanders’, in the Times in January 1917, the author commented that ‘no one knew who they were at first, but they are now a familiar part of the scene – these New Zealanders, whose complexions are as bright as the red in their hats.’Footnote56 The New Zealanders’ height and ruddiness were part of their constructed masculinity as pioneer men, and this ‘othered’ them from the British population, presented as red, rather than white. The soldiers were aware of the unfamiliarity of the population with New Zealanders and their recognizable difference. Charles Saunders wrote that,

We were very conscious with our slouch hats in the streets, and little boys used to gape at us quite a lot. We had “New Zealand” in white on a crimson ribbon on both arms just below the shoulders, and one little paper boy looked hard at it and slowly and laboriously spelled it out, looked into my face, then said to his mate “New Zealand!! And cor blimey e's white”. I guess he thought we were all Maoris in NZ.Footnote57

New Zealanders might have ‘known’ the city in some form, but London itself made them conscious that this was not their home. The representation of New Zealanders, amongst other colonial troops, negated a sense of particular connection between the two countries, and highlighted physical demarcations of difference that reminded the troops that they were a transitory part of the city.

Longing for ‘Piccadilly’: women, sex and London

The poem ‘Leave’, published in the 1917 version of the troop magazine New Zealand at the Front, articulated one London experience shared by many New Zealanders, which could shape the expectations of others:

I long for Piccadilly

And its crowds of lovely girls,

With their neat silk-stockinged ankles

And their captivating curls,

With their thin, delicious blouses,

Dreams of silk and filmy net.

(Are pink nighties now the fashion?

Or is it crepe Georgette?)Footnote58

Going on leave in London was envisioned as a time and space for sexual contact, of a strictly heterosexual nature. Sex was an expected part of leave for soldiers during the First World War, particularly with prostitutes. Being on leave took the men away from the homosocial spaces of the military and into spaces of heterosexual activity. The poet did not indicate that these women were prostitutes but these ‘crowds of lovely girls’ could be seen to be part of the ‘khaki fever’ phenomenon: the attraction to men in uniform which could render collective female behaviour ‘immodest’ and even ‘dangerous’.Footnote59 The troops were prepared for women on the streets, from fashionable shopping districts to the East End slums, in train stations and outside theatres. The army recognized sexual encounters as part of leave. Eric Hames expressed his shock that before leave in London, they were issued with contraceptives and antiseptic ointments. ‘The great majority of us I am sure had never heard of such a practice, being unsophisticated in an unsophisticated era, and we received our initiation with a sort of wild incredulity.’Footnote60

In understanding representations of sex by New Zealand soldiers, the familial audiences for letters and diaries would filter the impressions that the troops chose to share. Yet, within their descriptions, the disgusted fascination with the women on London's streets revealed more than self-preservation. Herbert Hart observed that ‘London is very crowded and very, very wicked. I have never seen so many “Totties” before, well dressed and looking radiant’.Footnote61 Francis Healey's dislike of London arose from ‘the way the women drink in the public bars and the amount of the prostitution on the streets both day and night’.Footnote62 Writing about prostitution created an elite gaze turned back on the metropolis, mirroring reflections on the East End, where New Zealanders like Hart and Healey could experience a form of metropolitan superiority towards London's ‘exotic’ periphery and its core. Rather than longing for ‘Piccadilly and its crowds of lovely girls’, the soldiers presented themselves as curious or disgusted observers of prostitutes on London's streets which served to distance them from the city.Footnote63 They were ‘outside’ of this ‘wickedness’ rather than complicit insiders in metropolitan ‘vice’.

This is not to say that references were not made to encounters with women in the city. New Zealanders’ representations of flirtations and romantic encounters were integrated into other tourist experience. Herbert Tuck brought a ‘nice little girl’ with him to the theatre, ‘a different one from last night. Oh I can tell you, I am getting no better fast.’Footnote64 The men combined traditional tourist activity like going to the theatre with courtship. Though theatres had associations with prostitution, they were part of the official sightseeing agenda.Footnote65 The representation of sex in London could become more domesticated, as exemplified in New Zealander John A. Lee's novel, Civilian into Soldier (1937), which drew on his own experience in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force.Footnote66 Lee's narrator associated sex on leave in London with the domestic and home. Though he had refused to visit brothels in Egypt and France, something specific about the English women that allowed a relationship with home to be maintained and so he felt able to engage in sexual activity.

Their presence, their attractiveness, their Anglo-Saxon characteristics, their pure English, catered for a something in the soldier that had been stifled, a something for which the sight and sound of a French slattern was a poor substitute. There was a touch of home, of New Zealand, about the Club in the heart of Empire, and reactions of a subtle nature were evoked.Footnote67

While this could be read as the exemplification of Barnes’ ‘domesticated sex in the city’, deconstructing the passage reveals once again the ambiguity of ‘home’ within the setting of London.Footnote68 The women's Englishness had a specific appeal to this New Zealand soldier, but there was also the familiarity of New Zealand within this setting that fuelled the attraction. It was the reminiscence of a home far away, rather than the identification of London as an extension of home, within the encounter. The conflicting emotions of New Zealand soldiers engaged in sexual relations in London becomes apparent as they grappled not only with their desires and repulsions but their identity as men both at home and abroad in the strange but familiar city.

Maoris in London

In analyzing New Zealand soldiers in London, Barnes draws exclusively on the experiences of Pakeha New Zealanders, those soldiers of European descent, rather than Maori troops, who also visited the city during the First World War. Understandably, the connections between those New Zealanders whose families were British and London as the metropolis provided a basis for shared heritage. However, by demonstrating the ‘colonial’ identity of New Zealand's soldiers and the ambiguity of the position they held in the city, I have tried to situate this experience in the broader context of colonial troops arriving in London during the First World War. It therefore makes sense to address Maori tourism, as members of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, both in the Maori Contingent and the Maori Pioneer Battalion, and part of the colonial milieu in London during the war. How would the experience of Maori men differ from their Pakeha compatriots?

That non-white troops were present in the metropolis as troops on leave during the course of the war was recognized by the press; these men added to the ‘pageantry’ of the empire on London's streets, whether white or non-white. Equally, the Colonial's Guide did not make explicit that its directions were exclusively for white troops. Manders wrote in the preface that,

This Guide, though issued mainly for the use of visitors from the Dominions and Crown Colonies of the Empire, will be found of considerable value to visitors from other parts of the world.Footnote69

There is a specific address to the Anzacs and Canadians in the guide's title and throughout the text, advice and examples centre on Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, South Africans – those white troops from the settled dominions – but there is no explicit designation for white troops alone. A degree of assumption about the invisible ‘normativity’ of whiteness is present in the text, for instance in the othering of the Chinatown area or in the easy movement of the troops through the majority white urban space. However, the list of soldiers’ clubs towards the guide's end includes the West Indian Club, which opened membership to those serving in West Indian Contingents during the war years, catering for the incoming men in much the same way the Anzac Buffet did.Footnote70 While it is difficult to ascertain whether Maori men, among the other non-white colonial troops, used The Colonial's Guide or other similar guidebooks, the existing accounts reveal a similar tourist trail through the city as that of the white New Zealanders.

In the face of the prolific travel writing of white New Zealand soldiers, there are fewer Maori accounts to draw upon. One of the most important sources is the diary of Rikihana Carkeek, published as Home Little Maori Home: A Memoir of the Maori Contingent, 1914–1916 (2003). Carkeek was a member of the First Maori Contingent. He left New Zealand in February 1915 on the SS Warrimoo, sailing to Egypt via Colombo, involved in active combat at Gallipoli, before coming to the Western Front in April 1917. He was invalided to England with tuberculosis and spent four months convalescing, between May and October 1916. From his base in the New Zealand military hospital, Carkeek made a number of visits to London. His descriptions of his time in the city echo those of the Pakeha men. On 6 July 1916, he was given leave from the hospital and took the train up to London with a friend.

This was my first trip to the Big Smoke. We went to see Madame Tussaud's waxworks. It's a marvellous show. We had afternoon tea there, paid for by a New Zealand lady. Then we went to see the sights and along the Strand. Some kind ladies from Kent shouted tea for both of us. We saw St Paul's Cathedral and came back by railway tube via Charing Cross to Waterloo station, and thence home to the hospital. It was a most enjoyable day.Footnote71

On his return to London a month later, Carkeek ‘went straight to the New Zealand War Contingents Association to get my balance of one pound. Stayed at the NZ soldier's club in Russell Square.’Footnote72 The next day he strolled around ‘the Big City’, seeing ‘Westminster Abbey and St Andrew's Church, Grosvenor Square, Rotten Row, Hyde Park, Piccadilly and to Christies, the famous auction rooms.’Footnote73 These were the same historic sights identified as having cultural significance for the white dominion troops, and while Carkeek does not reflect explicitly on a sense of shared history, they were still the vital sights to see. Carkeek's diary reads much the same as the Pakeha accounts of time in London, an opportunity to see the Big City, which was freely available for him to explore. The easy mingling with women in the space, treating him and his friend to tea on multiple occasions, reveals no racial distinction, simply recognition of colonial soldiers on leave, a sentiment echoed by Maori veteran William Bertrand. In an oral history interview with Jane Tolerton, Bertrand discussed the time he spent in London on leave.

I was really impressed by the hugeness of London, I went there on leave, I took a taxi…I was very impressed with the immensity of the place…I thought to myself, well I can say I've seen London, which a lot of people haven'tFootnote74

The sense of success at ‘arriving’ in the vast metropolis reverberated through Bertrand's memory of his war experience, much like the contemporary writings of the white New Zealanders. Tolerton asked him directly, ‘How did they (people in Britain) react to you as a Maori?’ He replied,

There was no sign of any distinction, I was a soldier serving my country, that's all there was to it… They didn't seem to ask anything personal, they just took you as a New Zealand soldier, and that was that. Everybody was well treated by the people, as far as I know. I had some very interesting conversations in the soldiers’ clubs talking about New Zealand.Footnote75

Like Edward Ryburn's attempts find New Zealand in London to articulate a sense of identity, Bertrand was even more vocal, using the social spaces of the city to communicate a sense of his home to those he met, far away and unfamiliar in the metropolis.

Further, while experience of sightseeing would be expected to follow familiar patterns, even other pleasure seeking activities in the city were not off limits to Maori men. The kits preventing venereal disease, which had so shocked Eric Hames, were not provided to non-white troops. Instead limiting their mobility was the chosen method of prevention, indicating ‘a modicum of personal freedom’ offered to the white dominion troops in their management of sexual encounters.Footnote76 Philippa Levine has addressed the policing of Indian soldiers in Brighton to highlight how racialization determined the access troops had to spaces in the imperial centre.Footnote77 Yet Rikihana Carkeek, having returned back to the New Zealand soldiers’ club for a bath, wrote about going to Hyde Park one evening ‘to meet a lady friend’; the night outing reveals Carkeek's freedom in the city to engage with women on a more than platonic basis.Footnote78 Like theatres, cinemas, music halls and even streets, parks had multiple, overlapping mappings which enabled them to be presented as respectable while their public-ness could allow them to hide illicitness, particularly at night and in the dark. From his London base, Carkeek was relatively free to combine his leisure and pleasure activities. His freedom in London indicated the complexity and variation in the restrictions on the movements of troops of colour and how they mixed with English women.

Relying on Carkeek and Bertrand's representations of their time in London means working within a more limited scope than addressing the experience of white troops, hence the separate analysis of these accounts. Discerning whether Carkeek and Bertrand felt like they should belong in London, as part of the British Empire, or whether they simply enjoyed exploring the famous city is difficult. Yet, by reading these in conversation with the white troops’ accounts, the entangled experience of both groups in London becomes more apparent. Rather than solely interrogating the line from dominion to metropolis, a more horizontal analysis is made to better understand New Zealanders’ time in London as colonials as well as ‘Britons’ in the space, the white men experiencing the city in much the same way the Maori soldiers did.

Conclusions

Time in London was significant for the soldiers from New Zealand, both Pakeha and Maori: the status equated to ‘arriving’ in the metropolis; the opportunity to see in person sights made familiar to them and their families through postcards, films and magazines; the leave from life at war and the horrors it entailed. That this was a time of being ‘at home’ or feeling part of the city as an extension of New Zealand, or culturally co-owned is less certain. What has been asserted is the role of ambiguity for New Zealanders in London during the war, both insiders and outsiders in the imperial capital, a reading of experience that offers nuance to the previous work of Felicity Barnes. There were certainly efforts to make the men feel at home, through the advice of guidebooks to present a knowable London or the activities of organizations like the New Zealand War Contingent Association, which created accessible, home-like spaces within the capital, which gave the soldiers a sociable base for their tourism. The descriptions of being on leave in the city from the men indicate the appreciation of such organizations and how they used guided tours to find those elements of the city that were of most importance, which Barnes has described as forming New Zealand's London.

Yet, the encounters between the men and the urban space reveal a degree of separation that limited the extent to which ‘home’ was a possibility. Critiques of London, either in the traditional sightseeing or explorations into the ‘exotic’ East End or of the city's women, offered an opportunity to seek out or assert a distinct New Zealander identity. Further, depictions of the men in newspaper reports as identifiably colonial or having a clear ‘New Zealand’ appearance that borders on a racial difference, part of the imperial pageant of war, asserts the temporariness of the New Zealand soldiers in the city. While their whiteness placed them at the top of the racial hierarchy, their colonial status as soldiers of the Empire was evident to the Londoners who encountered them. Understanding the uncertainty and ambiguity of status of the white dominion soldiers in the metropolis helps to draw out the complexity of the relationship between the enlisted troops and the empire they were nominally fighting for.

Whether this experience of London was exclusive to the white New Zealanders is questioned by the inclusion of Maori experiences in the city, whose accounts reveal significant parallels across the two groups. How did the experience of the New Zealand soldiers in London compare to those of other nationalities and ethnicities mobilized by the British Empire? With an increase in studies recovering the experiences of colonial troops, particularly non-white groups, and analyzing transnational mobility, entanglement and encounter during the war, comparing the experiences of colonial troops in London as a locus point of empire and connection would be a fruitful topic of future research. Rather than solely thinking about the relationship between metropolis and colony, drawing horizontal links between different colonies and how they related to London offers a rich scope for understanding questions of identity and belonging during the turbulent period of conflict.

ORCiD

Anna Maguire http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9867-1122

Notes on Contributor

Anna Maguire is an AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award Student at King's College, London and Imperial War Museums, London. Her PhD, entitled ‘Colonial Encounters during the First World War’ explores the experience of war for troops from New Zealand, the West Indies and South Africa through the framework of encounter. She is a member of the HERA funded project ‘Cultural Exchange in a Time of Global Conflict: Colonials, Neutrals and Belligerents’.

Notes

1 Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington (henceforth ATL), MS Group 2082, Diary of Henry Kitson, 28 July 1915.

2 Angela Woollacott estimates 10,000 visitors annually from New Zealand and Australia from the late 1880s to beyond 1900. A. Woollacott, To Try Her Fortune in London. Australian Women, Colonialism and Modernity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 5.

3 J. MacKenzie, Propaganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880–1960 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984), 17.

4 ATL, MS Papers 4134, Letter from E. Gray, 4 February 1917.

5 F. Barnes, New Zealand's London: A Colony and its Metropolis (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2012), 16. Elleke Boehmer's recent work Indian Arrivals, 1870–1915: Networks of British Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015) includes a coda on Indians and the First World War.

6 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 2.

7 Woollacott, To Try Her Fortune, 4–5.

8 MacKenzie, Propaganda and Empire, 99. Exhibitions also played a role during the First World War, as ‘an effective medium for fashioning and disseminating images of modern war for consumption by a civilian audience’. See S. Goebels, ‘Exhibitions’ in Capital Cities at War. Paris, London, Berlin, 1914–1919. Volume II: A Cultural History, ed. by J. Winter and J. Robert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 143.

9 D. S. Ryan, ‘Staging the Imperial City: the Pageant of London, 1911,’ in Imperial Cities: Landscape, Display and Identity, ed. by F. Driver and D. Gilbert (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), 119.

10 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 6.

11 A. Woollacott, ‘The Colonial Flaneuse: Australian Women Negotiating Turn-of-the-Century London’, Signs, 25, 3 (2000), 762–763.

12 Woollacott, To Try Her Fortune, 14.

13 Woollacott, To Try Her Fortune, 34.

14 R. White, 'The Soldier as Tourist: The Australian Experience of the Great War', War and Society, 5, 1 (1987); J. Wieland, ‘There and Back with the ANZACs: More than Touring’, in Perceiving Other Worlds ed. by Edwin Thumbo (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1991); Gray, 4 February 1917.

15 B. Ziino, ‘A Kind of Round Trip: Australian Soldiers and the Tourist Analogy, 1914–1918’, War & Society, 25 (2006), 52.

16 Imperial War Museum (henceforth IWM) Documents 16373, Diary of E. M. Ryburn, 26 August 1915.

17 A. Staines Manders, Colonials’ guide to London (London: Fulton-Manders Publishing, 1916), 18.

18 J. Curran, ‘“Bonjoor Paree!” The first AIF in Paris, 1916-1918’, Journal of Australian Studies, 23 (1999), 22.

19 Curran, ‘“Bonjoor Paree!”’, 22.

20 D. Gilbert, “‘London in All Its Glory—or How to Enjoy London”: Guidebook Representations of Imperial london’, Journal of Historical Geography, 25 (1999), 281.

21 A. Staines Manders, Colonials’ guide, 18.

22 A. Staines Manders, Colonials’ guide, 18.

23 ATL, MS 2003/71, Letters from A. Bousfield, 7 May 1916.

24 National Military Museum New Zealand (henceforth NMMNZ), MSS-058, H. Bourke, 21 September 1917.

25 ‘New Zealanders in England’, The Times, 26 September 1916.

26 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 68.

27 ATL, MS Papers 7899/2, Letters from A. Olsson, 14 June 1917.

28 ATL, MS Papers, Diary of J. Moloney, n.d.

29 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 69.

30 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 61.

31 ATL, MS 2003/71, Letters from A. Bousfield, 13 May 1916.

32 AWMM, Diary of F. Healey, 5 July 1917

33 NAMNZ, MSS-051, Letters of W. Malcolm, 8 March 1918.

34 NMMNZ, MSS-038, Diary of N. Coop, 20 March 1918.

35 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 60.

36 A. Staines Manders, Colonials’ guide, 168.

37 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 26; Woollacott, To Try Her Fortune, 4.

38 Woollacott, To Try Her Fortune, 163.

39 IWM Documents 16373, Diary of E. M. Ryburn, 21 June 1916.

40 IWM Documents 16373, Diary of E. M. Ryburn, 21 June 1916.

41 IWM Documents 16373, Diary of E. M. Ryburn, 5 October 1916.

42 IWM Documents 16373, Diary of E. M. Ryburn, 28 October 1916.

43 IWM Documents 16373, Diary of E. M. Ryburn, 28 October 1916.

44 J. Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 26.

45 AWMM, MS 2002/72, Diary of H. Hall, 19 August 1916.

46 J. Seed, ‘Limehouse Blues: Looking for ‘Chinatown’ in the London Docks, 1900–40’, History Workshop Journal, 62 (2006), 59.

47 A. Staines Manders, Colonials’ guide, 77.

48 A. Staines Manders, Colonials’ guide, 77.

49 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 31, 2.

50 AWMM, MS 99/22, Diary of E. Dredge, 27 April 1917; AWMM, MS 2002/97, Diary of J. McWales, 26 June 1918.

51 NMMNZ, MSS-058, H. Bourke, 23 September 1917.

52 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 38.

53 ‘A Pageant of War’, The Times, 10 November 1915.

54 AWMM, MS 2002/165, Diary of J. Maguire, n.d.

55 ‘What the Empire had done’, Everyman, November 1916

56 ‘The Tall New Zealanders’, The Times, 29 January 1917.

57 IWM Documents 12000, Private Papers of C. W. Saunders, 8.

58 New Zealand at the Front (1917), 48.

59 See A. Woollacott, ‘'Khaki Fever' and Its Control: Gender, Class, Age and Sexual Morality on the British Homefront in the First World War’, Journal of Contemporary History, 29 (1994) and P. Levine, ‘"Walking the Streets in A Way No Decent Woman Should": Woman Police in World War One’, Journal of Modern History, 66 (1994).

60 IWM, Documents 5515, Diary of E. Hames, 19.

61 J. Crawford, ed., The Devil's Own War: The First World War Diary of Brigadier-General Herbert Hart (Auckland: Exisle Publishing, 2008), 11 November 1916.

62 AWMM, Diary of F. Healey, 5 July 1917.

63 New Zealand at the Front (1917), 48

64 IWM, Documents 19697, Letters of H. Tuck, 9 January 1917.

65 T. C. Davis, Actresses as Working Women: Their Social Identity in Victorian Culture (London: Routledge, 1991), 80.

66 J. A. Lee, Civilian into Soldier (London: T. W. Laurie, 1937).

67 Lee, Civilian into Soldier, 255.

68 Barnes, New Zealand's London, 64.

69 A. Staines Manders, Colonials’ guide, preface.

70 D. Clover, ‘The West Indian Club Ltd: An Early 20th Century West Indian Interest in London’, Society for Caribbean Studies Annual Conference Papers, 8 (2007), 4.

71 R. Carkeek, Home Little Maori Home: A Memoir of the Maori Contingent, 1914–1916 (Wellington: Totika Publications, 2003), 6 July 1916.

72 Carkeek, Home Little Maori Home, 2 August 1916.

73 Carkeek, Home Little Maori Home, 3 August 1916.

74 ATL, OHInt-0006/06, Oral History Interview with William Bertrand, Reel 1.

75 Bertrand, Reel 1.

76 P. Levine, Prostitution, Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire (London: Routledge, 2013), 151.

77 Levine, Prostitution, Race and Politics, 154.

78 Carkeek, Home Little Maori Home, 3 August 1916.