Abstract

The London Blitz was a catalyst for national state control of the entire commodity network for furniture; the only wartime commodity for which this was done. The Utility furniture scheme sought to manage material shortages and combat profiteering in the markets for new and second-hand furniture. It also responded to the vulnerability of the nation’s furniture producers, which were disproportionately concentrated in and around London. Set against the immorality of indiscriminate bombing of civilian populations and illegal practices on the ‘black market’, the Utility scheme prescribed new moral geographies of equitable distribution based on need, of consumer rights protection, and of improvements to labour conditions and wages. The paper intervenes into debates about the social construction of moral geographies by examining the collective institutional response of the Utility scheme and the manner in which it sought to provision wartime homes.

Introduction

The Utility furniture scheme, which was planned in late 1942 and implemented from 1943 by Britain’s wartime coalition government, represented a distinctive response to the materials shortages generated by war as well as to the specific impacts of the London BlitzFootnote1 on the city’s households and furniture industry. The bombing of London acted as a catalyst for action: it brought about state control of the entire commodity network of furniture design, manufacturing, distribution, and consumption. No other consumer goods were coordinated in this way during the Second World War and until the closure of the scheme in 1952. As design historians of Utility have emphasized, ‘one of the main roles of the Utility scheme […] was that it should be seen to be fair to the whole population in its allocation of scarce consumer goods’.Footnote2 At the same time, the pursuit of equity at a national level emerged directly from assessments of socio-economic dynamics at work in London, notably moral concerns over historic labour conditions and wages within the furniture industry — particularly in the East End. That is, London is central to an understanding of wartime furniture commodity control and industry restructuring, not just because of the spatial concentration of the industry in the capital, but further because late nineteenth-century moral geographic understandings of sweated labour and sweated trades in London were so important to the framing of the Utility furniture scheme.

In this paper, we extend our previous analysis of the pragmatic character of the schemeFootnote3 to foreground the moral geographies of Utility. In doing so, we make four important contributions. First, we develop geographers’ engagements with moral philosophy as a means of ‘ask[ing] questions about social and spatial justice’.Footnote4 Importantly, we extend debates about how moral geographies are constructed by understanding how ‘morality’ is expressed through ‘the world of collectivities and institutions’ rather than ‘the consideration of individual conduct’.Footnote5 Moreover, we reveal the varied and morally complex nature of these geographies by examining institutional responses by the Nazi state to parallel pressures. Secondly, we argue that whilst Utility was a national scheme, it cannot be fully understood without examining how it was shaped by the distinctive geographies and characteristics of the London furniture industry as it developed over the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In this sense, we tease out connections between locally grounded and more spatially extensive networks of action and intervention. Third, our focus on the impacts of the Utility scheme on the London furniture industry fills a significant gap within existing analyses of the twentieth-century furniture industry,Footnote6 which tend to pass over the wartime period and calculate trends between the 1921 and 1951 Censuses.Footnote7 We argue this neglect is unfortunate since Utility established important dynamics for London’s post-war furniture industry. Fourth, and following on from the above, we are able to extend discussions of the post-war reconstruction of bombed cities and their tendencies to focus on the physical architectures and planning of the built environments, to draw attention to how cities were also remade through the spaces of the home and the networks through which material items are produced and supplied.

Our account of Utility’s geographies should not be viewed as ‘moral’ ‘in any absolute sense’Footnote8 — that is, as ‘good’ rather than ‘bad’ or ‘just’ versus ‘unjust’ in general or universal terms. The Utility scheme was based upon a set of practical organizational arrangements designed to resolve crisis and scarcity in an equitable and socially just manner, acting to both produce and reproduce moral geographies in and beyond London. That is, ‘moral assumptions and arguments often have built into their very heart thinking about space, place, environment, landscape and (in short) geography’.Footnote9 As Garelli and Tazzioli have more recently argued, the notion of moral geographies allows us to understand how morality takes on a strong ‘spatial articulation’: morality can become ‘a spatial technology (predicated on space and through space); a spatial outcome […] and […] an economic space’.Footnote10

Moral geographies are thus complex and ambiguous. There is, of course, a strong irony that the Utility scheme emerged amidst the immorality of war; and as part of the indiscriminate bombing of civilian populations across ‘innumerable settlements in the European and Pacific theatres of war’.Footnote11 At the same time that London’s householders were able to purchase Utility furniture made by ‘designated’ firms, other London furniture manufacturers were engaged in the production of wood-based military equipment (ranging from ammunition cases and tent pegs to aircraft such as the de Havilland MosquitoFootnote12 and Horsa Glider), which were deployed to wage war and undertake bombing raids against civilian populations in enemy cities.

The paper is organized as follows: in the first section, we scrutinize long-standing concerns about the furniture industry and in particular its distinctive characteristics in and across London. This includes unpacking moral anxieties about working conditions in the industry, about the quality of products supplied to consumers; and reflecting upon moral evaluations of problems within the ‘East End’ trade, which were at times xenophobic. We then examine the immediate circumstances and moral concerns provoked by the start of the war, consequent from the London Blitz and its impact upon the city’s furniture industry and the consumer market. This section details how the Utility furniture scheme sought to respond to pressing circumstances of war as well as to seek to ‘correct’ problems within the furniture trade as historically constituted. The specific impacts of the scheme upon the London furniture industry are documented in the fourth section, before we move on to consider the legacies and resonances of the Utility scheme for London in the post-war period. Our conclusions draw into focus broader insights into moral geographies that our analysis has revealed.

Historic concerns with the London furniture industry

The wartime motivations for the Utility scheme emerged amidst a set of much older moral assessments about the shape of the London furniture industry, which had been historically characterized by long hours, low wages, and unsanitary conditions. Although some larger firms existed, the furniture industry at the time of Charles Booth predominantly involved subdivided, specialized subcontracting arrangements, in which ‘small makers’ oversaw fewer than six workers, utilizing little capital or machinery.Footnote13 Much production was speculative: ‘East End manufacture was done to the express order of the dealer: a maker would produce for stock only when times were slack, and might have to hawk the goods thus made along Curtain Road’.Footnote14 Small makers often worked out of rented small rooms at the back of residential properties, as documented in Samuels’ East End Underworld. Footnote15

The London furniture industry had been a particular focus of concern in the 1888 House of Lords Select Committee report on Sweated Trades; and featured in Booth’s reports on London Life and Labour as well as the follow-up New Survey undertaken by the London School of Economics in 1928.Footnote16 The latter was critical of interwar labour conditions:

while on the whole wages and conditions of work have altered for the better, one of the grave evils of the furnishing trades is still the large number of small cabinet-makers who have no margin for bad times, and not being members of trade unions, sick clubs or provident associations, soon sink into the poverty-stricken class when times are bad, or public taste changes, or when the breadwinner falls ill or dies.Footnote17

Honourable/dishonourable trades: East End/West End furniture makers

Moral judgements and discourses about labour conditions in the furniture industry had long rested upon a reputational distinction between an ‘honourable’ West End and ‘dishonourable’ East End furniture trade, first articulated by Henry Mayhew in the mid-nineteenth century. Citing Mayhew, Edwards asserts that the:

‘dishonourable’ part of the trade operated in the East End of London, where the ‘sweating system’ took advantage of self-employed cabinet makers and pushed down the possibility of quality work by price pressure, lack of training, and fierce competition.Footnote19

One of the significant moral geographies at work in the ‘honourable’/‘dishonourable’ binary was a repeatedly expressed opinion that the prevalence of sweating in the furniture and clothing trades had emerged and was reinforced as a result of a distinct wave of Jewish immigration to the East End from Russia and Poland in the late nineteenth century. Xenophobia was significant in the damning of the East End sweated trade, as revealed in Booth’s account:

The unfortunate East End worker, struggling to support his family and keep the wolf from the door, […] is met and vanquished by the Jew fresh from Poland or Russia, accustomed to a lower standard of life, and above all of food, than would be possible to a native of these islands; less skilled and perhaps less strong, but in his way more fit pliant, adaptable, patient, adroit.Footnote21

All their [Collinson and Lock’s] furniture is made by Englishmen, who are paid ten pence and a shilling an hour, and not by Jews in the East End for threepence or fourpence.Footnote22

Consumer concerns

Critical historical assessments of parts of the furniture trade extended to expressions of concern about the nature of goods offered to consumers. As Aves reported:

… in the great bulk of the trade repetition, and the making up of fresh patterns which are simply slight variations on those already in the market, are the ruling practices. […] the hurry is too great, and the popular demand for cheapness, cheap things ‘at any cost,’ too strong, to give much opportunity for the exercise of artistic talent, or to allow much really good and careful work to be produced.Footnote25

Through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the specific demands and dynamics of the London consumer market, including furniture, acted as key drivers of industrial development in the capital, highly reliant as it was upon conspicuous and ‘competitive consumption’.Footnote28 Seasonal patterns of production in the furniture industry were even more exaggerated in London: the ‘season’ drove purchase fluctuations in amongst high-end consumers placing orders with West London retailers, for example. More generally, the capital was seen to display high levels of consumer demand for ‘variety and variation’.Footnote29 Whilst at one level, such forces may have produced an industrial structure that was ‘more responsive and dynamic than in the provinces’,Footnote30 a pursuit of endless ‘variety’ in the London industry created downward wage-price spirals as competition amongst subcontractors directly led to ‘declining profits for masters and declining wages for workmen’.Footnote31 As Steadman Jones has emphasized, sweating

was one radical solution to the problem of provincial factory competition. Temporarily at least, it provided a successful answer to the most pressing problem of the inner London manufacturer — how to offset the disadvantages of high rents, expensive fuel, high wages and scarce skills in competition with cheaper semi-skilled factory production.Footnote32

In summary, therefore, in the period prior to the outbreak of war, the dominant characterization of London’s East End furniture trade was as a long-standing cause of poor quality furniture, copying, and sweated trades. For reformers, however, these associations and the reforms they necessitated were by extension a challenge for the whole national space economy of furniture making. In this sense, therefore, the reforms initiated by the catalytic effect of war and as enacted through the Utility furniture scheme rested on a distinctive moral geography of a disreputable East End furniture trade in London. The paper will now examine the development of the scheme, detail how it sought to fix these and emergent moral challenges, and assess the impacts upon London’s firms and consumers.

The wartime Utility furniture scheme

The outbreak of war and the bombing of London from September 1940 aggravated existing concerns over the furniture industry whilst also mapping onto it a new set of challenges and moral apprehensions. The destruction of homes and displacement of ‘bombee’ households rapidly increased demand for furniture whilst simultaneously undermining production capacity, as industrial premises were destroyed, voluntarily closed or in the case of larger premises diverted into war work. This left limited plant and labour capacity in the capital’s remaining small and medium-sized firms. Restricted supplies of raw materials, notably timber, plywood, and veneers, due to disrupted international supply chains and rationing for military use compounded the situation, as did a general rise in consumer purchasing power via earnings from war work.

Acute shortages of furniture as a consumer good led to rapid price inflation across markets for both new and second-hand furniture, with which price control legislation, such as the June 1940 Price of Goods Act and the May 1942 Goods and Services (Price Control) Act struggled to contend.Footnote35 Inevitably, price inflation led to concerns over ‘uneconomic production and the use of inferior substitute materials’Footnote36 alongside governmental anxieties over profiteering and an emerging black market, particularly in second-hand furniture. Footnote37 There were also reports of theft and looting of bombed premises. The full extent of overt criminal activity is difficult to judge empirically. Some accounts provide anecdotal evidence of its character in the early years of the war, such as Thomas’ example of thieves stripping an entire street in Dover:

there was little doubt that this was the work of a London gang, large enough to dispose of such quantities at a time when the underground market in second-hand domestic goods was most active … [given timber supply restrictions from 5 September 1939] pre-war items were at a premium on the illegal market supplied by thieves and looters.Footnote38

Large-scale black market operations involving big sums of money and large quantities of controlled goods were few and far between, but petty transactions involving large numbers of people and little or no money were commonplace.Footnote40

Designing and implementing the Utility scheme

Whatever the full extent of ‘black market’ activities, assumptions or expectations about how they might create inequalities in the production, distribution, and consumption of goods formed an important motivation for government intervention. Utility represented a collective institutional attempt to establish a new set of equitable moral geographies regarding furniture distribution and consumption, and the labour conditions of its production. The first of these moral interventions controlled sales of Utility furniture to consumers ‘in need’ and in possession of a government-issued buying permit. A rigid system of pointing was designed, under which a specific number of units were required for each piece of furniture. In 1942, ‘priority classes’ of consumers were defined as couples and/or ‘bombees’ who

proposed to marry and set up house within three weeks or who had married on or after 1st January 1941; people who were setting up house because they had or were about to have young children, and people who had lost furniture through enemy action.Footnote43

The Utility scheme initiated a form of consumer rights protection, prompted both by the immediate social and economic pressures of war as well as by concerns about undesirable trade practices in sections of the industry. The scheme carefully specified a narrow range of designs that not only ensured economy of materials in manufacturing, but also was able to provide a uniform quality of product to consumers at a fixed price. An extensive network of Government inspectors visited firms to ensure manufacturing standards; and as a result, the CC41 utility mark, which was to appear on each individual item along with the accompanying manufacturer’s designation number, functioned as a symbol of product quality control and traceability.

Moral concerns about labour conditions and wages were enacted through the process by which the state chose firms to manufacture Utility furniture. The Board of Trade restructured domestic furniture production at a national level via the ‘designation’ of individual firms in particular cities and regions to produce specific types of Utility furniture (i.e. chairs, sideboards, wardrobes, etc.). Given the industry’s historic concentration in London and High Wycombe, the state determined that it was vital to spread manufacturing capacity more widely over the national space economy during wartime across 38 ‘production zones’.Footnote44 This would reduce vulnerability to future enemy bombing and access a pool of available labour throughout the rest of the country. In conjunction with geographical area restrictions placed on buying permits, carefully specified production zones also facilitated reductions in distribution costs and demands upon scarce petrol resources. The simplicity of standardized designs made it easier for new or inexperienced manufacturers and their workforces to take on Utility work.

Importantly, firm designation was linked to improved wages and conditions for workers, although this situation was to emerge through the negotiated process of designation rather than made explicit in the initial stated design of the scheme. Inspectors appraised firms’ working conditions and technical ability, including making moral assessments of firms’ reputation (as ‘good’ or ‘not good’).Footnote45 The designation was also closely connected to the way the war augmented the effectiveness of trade union organization across the furniture industry by bringing together employees, manufacturers, and retailers organizations under government sponsorship, such as, from 1939/1940 the British Furniture Trade Joint Industrial Council (JIC) and the 1940 Manufacturing Trade Board.Footnote46 These agreed policies on wages and conditions, such as minimum wages for male and female workers from June 1940. The government also accepted union pressure that all firms involved in war production should be unionized.Footnote47 For example, Harris Lebus, London’s largest furniture company with some 3,500 employees, had resisted interwar lobbying by the National Amalgamated Furnishing Trades Association (NAFTA) for union recognition until 1939 when the firm’s involvement with government work forced compliance.Footnote48

This framework of employer–union relations had a precursor in the Joint Industrial Council (JIC) set up in December 1918 comprising employers and trade unions which sought to regulate wages, hours, grievance procedures, and working conditions for the post-World War I furniture industry. Amongst other achievements, the 1918 JIC agreed a 47-hour working week. The dominant union at the time, NAFTA, campaigned strongly during the interwar period across both large and small firms for union recognition and the abolition of piece-rate payment by results (PBR); however, success was not uniform.Footnote49

Union influence became more pervasive as the Utility scheme developed. Having been consulted early on in the process, furniture trade unions argued that since the product was to be standardized in design and price then so too should there be a standard national wage for its workers. At a meeting on 3 July 1942 between Lord Forres and the furniture trade, it was recorded that on the issue of a national wage, unions were ‘by no means satisfied by being told that this was a matter for the Ministry of Labour’.Footnote50 Furthermore:

wages paid per hour vary greatly in the industry at the moment, and the Trade Union representative said he thought the workers would accept 2/2d an hour as a national wage. The non-adherence of certain firms to the ‘Fair Wages Clause’ has always been a source of great contention in the Furniture trade.Footnote51

I think we should have to insist that a firm paid the Joint Industrial Council wages, and we should certainly take into account the Union’s views on a firm, for example, if they reported exceptionally bad working conditions, I do not think we should licence.Footnote52

As soon as we knew the name of a factory which was to produce furniture under the utility scheme, we sent an official down to meet the management, and told them, ‘We have come to sign up all your work people as you are going into the utility scheme.’ The suggestion was that it was a condition of the contract that all workers should be in the union. No one ever questioned it and we established our influence over the whole of the utility making factories very quickly.Footnote54

Geographies of Utility in London

The Utility scheme had a dramatic impact upon the scale and geographies of the furniture industry, both nationally and across its traditional centres of London and High Wycombe. Initially, only 137 nucleus firms across the UK were licensed for production by March 1943.Footnote55 With a total of just over 4,000 employees, this marked a dramatic reduction from the national pre-war figure of 100,000 furniture workers.Footnote56 The Board of Trade licensed more firms as the war progressed — for example, responding to rising demand consequent from the renewed bombing campaign of 1944 — but by the end of the war in September 1945, there were only 497 designated firms, employing 19,091 workers.Footnote57

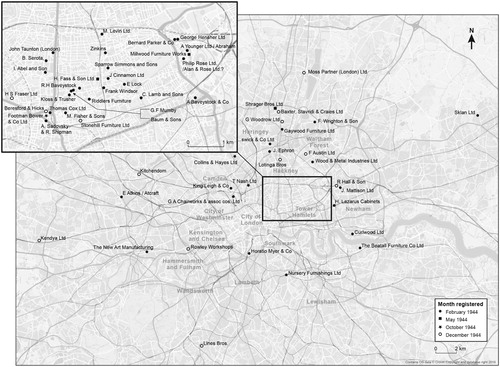

We can get a sense of the implications for London by examining mappings of firms licensed to manufacture utility during the war, across London more widely () and the traditional East End production centre more specifically (inset). It is notoriously difficult to compile consistent figures for the furniture industry, given its precarious and fragmentary structure; and gaps in the Census record are in part behind the aforementioned tendency for commentators to ignore wartime economic geographies.Footnote58 However, we can discern the scale of concentration by comparing Utility designations to the pre-war situation. The Final Report of the 1935 Census of Production (published 1944) indicates a total of 771 furniture establishments across Greater London. This figure, which includes High Wycombe manufacturers, had an estimated total employment of 52,852 persons.Footnote59 Oliver’s estimates, which exclude High Wycombe firms, suggest a figure as high as 1,103 firms by 1939.Footnote60 (See .)

Figure 1 London designated firms for Utility furniture production, February 1943 to December 1944 Source: Board of Trade, Correspondence re designations, TNA BT 64/1816.

TABLE 1 LONDON FURNITURE TRADES: NUMBER OF ENTRIES IN POST OFFICE DIRECTORIES, 1939

Under the Utility scheme, 40 London firms were designated by February 1944, rising to 58 by December 1944, which represented 11 per cent of firms nationally. These were mostly what might be described as ‘middling’ sized firms.Footnote61 Whilst a few designations were group schemes, such as GA Chairworks in Camden, which was an amalgamation of 17 smaller firms,Footnote62 the contraction of firms is clearly evident.

There was considerable variation across the London firms in terms of which of the 17 items of Utility furniture they were licensed to manufacture and the geographical zones they could supply. Most firms were allocated one or two items; and in comparison with firms outside the capital, their supply zones were relatively extensive, covering Greater London and much of the South East of England. For example, Zinkins of Hackney made sideboards and dining tables, A. Sadovsky and R. Shipman on Curtain Road made wardrobes, chests, and tallboys. Some firms allocated specialist items were permitted to ship them even more widely to compensate for lower levels of demand. Makers of kitchen cabinets (e.g. Bernard Parker & Co., Sparrow Simmons and Sons) could supply 22 different zones stretching from London and the South East through the Midlands and into South and mid-Wales, whilst Nursery Furnishings Ltd of Peckham supplied 10 zones.

Supply territories for London firms were modified at certain points in time. In February 1944, for example, following transportation difficulties, they were ‘appreciably cut down’.Footnote63 By August 1944, they were expanded because production rates in London were starting to exceed local consumer demand, whilst unmet demand existed elsewhere in the country and fuel for transport was more available. Predicting and allocating demand on the basis of allocated units to those entitled was never easy as is discernible from the exasperation of Board of Trade reports:

It is a curious phenomenon of war-time shortages that even people who don’t want something very badly will queue up for it or apply for a piece of paper which will entitle them to it just in case they want it later Footnote64

… a very different complexion has been put upon the position in every respect. Even in London, production and orders received show a steep rise and it may be that we are past the danger spot. The recent comparative immunity from flying bombs and the start made on repairing houses have made for greater security of tenure. I have no doubt also that the President’s timely statement in the House on the Vote of Credit about the continuance of utility — which fortunately received a good Press — has also helped a great deal.Footnote67

Of those London firms not designated to manufacture Utility, many larger firms such as Lebus were involved in war work. Whilst Lebus lobbied to produce Utility furniture alongside manufacture of munitions cases and glider components, their 1943 application was rejected, being judged as part of ‘the difficult labour area of Tottenham’ as well as government concern over ‘the reaction of the rest of the [furniture] trade, knowing that there are other firms in London now without work’.Footnote68 Many remaining undesignated smaller companies closed down as their owners enlisted for military service. Some survived by being allocated repair work of bombed damaged furniture or the making of making domestic woodware products from ‘off-cuts’, whilst there was also a compensation scheme for firms not designated.

Post-war resonances: the 1946 Working Party Report and beyond

The Utility furniture scheme lasted until 1948, and a modified ‘Freedom of Design’ phase, which gave manufacturers flexibility in design within the specified material dimensions but with continued price control and quality assurance, lasted until 1952.Footnote69 Across London, larger companies formerly engaged in war contracts were now permitted to join the range of firms who had been given Utility designations. The group of small and medium-sized firms that had not received designations during the war often did not return to furniture production in peacetime. In addition to materials shortages, wartime bomb damage of premises made it particularly difficult for London firms to restart production.Footnote70

As the London furniture industry continued to develop over the 1950s and 1960s, production, output, and employment became increasingly concentrated in the upper Lea Valley area. It was here that larger and more highly capitalized firms developed economies of scale through mass production of higher volume modularized furniture using new materials such as plywood and particle chipboard, which in turn were less dependent upon traditional furniture making labour skills. In relative terms, the traditional East End furniture cluster was to decline, although the 1957 County of London Plan was still able to identify over 60 establishments in the Bethnal Green and Shoreditch areas. Surviving smaller firms, unable to compete with the scale producers, tended to concentrate on more specialized ‘period piece’ reproduction trade.

There have been some attempts to document the scale of these shifts over this period, albeit again hindered by inconsistencies and gaps in official data sources. In broad terms, however, by 1961, the London and South East region accounted for 45% of national furniture work by turnover, which rises to 60% with the inclusion of High Wycombe and the Southern region.Footnote71 The 1958 Census of Production suggests some 32,500 employees in the furniture industry across Greater London, 35.3 per cent of the national total, whilst the 1957 County of London Development Plan identifies 18,655 ‘Furniture-making operatives’.Footnote72 This much lower figure is partly explained because much of the Lea Valley area lay at that time outside the County jurisdiction. Oliver’s survey enumerates 11,842 ‘Furniture making operatives in known works’ either side of the Lea Valley in 1961.Footnote73

In omitting analysis of the war and the Utility scheme, existing accounts of twentieth-century furniture economic geographies are unable to fully understand a set of important economic and political shifts and the character of this evolving industry.Footnote74 In contrast, we argue that Utility instigated a set of important implications and resonances that continued to shape the London furniture industry over the peacetime period of reconstruction. Although Freedom of Design ended in 1952, there was continued desire for a means of guaranteeing quality standards, and the Furniture Development Council sought to work with the British Standards Institution to prepare British Standards for domestic furniture, albeit that the achievement of agreement across different industry interest groups ultimately was highly problematic.Footnote75

The two most identifiable aspects in these impacts were the way it was to shape the modernization of furniture production and the transformation of labour relations. Both of these formed important themes within the 1946 Board of Trade Working Party Reports: Furniture, an official attempt to consolidate concerns underpinning the Utility scheme. Published after a year of investigation, the Working Party Report explicitly sought reform of the ‘chaotic labour conditions which prevailed before the war’ which were ‘responsible for many of the evils of the trade, not least for the depreciation of quality resulting from price-cutting’.Footnote76 Post-war reconstruction was thus not just seen as physical renewal but had strong moral implications. The Report was scathing of many traditional London firms that had been excluded from the Utility scheme:

There is a tendency in some quarters to sentimentalise about small firms and to represent them all as being craftsmen producing the finest furniture. In fact, a relatively small proportion are within this category and far too many of them are producing shoddy furniture under shocking conditions.Footnote77

Modernizing labour relations: trade union organization

To address their concerns, the Working Party recommended the establishment of a body to oversee the post-war development of the industry and to guide innovations in production marketing and training. The resulting Furniture Development Council established under the 1947 Industrial Organisation and Development Act was unique to the furniture industry. The Report also argued that the Utility scheme along with the accompanying tripartite relations it established between state, employers, and unions had been fundamental in discouraging the condition of sweated labour.Footnote79 The Joint Industrial Council established during the war was viewed as a model for post-war collaboration: it

… is now a truly representative body, able to speak and act for the industry, to survey its problems and potentialities without sectional bias, and reliable to negotiate with Government Departments. The good work of this organisation will extend far beyond the period of controlsFootnote80 (BT 64/2042)

In May 1947, NAFTA and the Amalgamated Union of Upholsterers (AAU) merged to form a single union.Footnote82 This in part reflected union recognition that modernization and mass production within the industry was breaking down traditional skill boundaries. Between 1946 and 1952, industry output almost doubled alongside only a 10 per cent increase in employment, demonstrating that industry was ‘ … well on the way to becoming a hand assisted machine production industry’.Footnote83 As unions sought a share of this prosperity, targeting recruitment in the larger London establishments, wages and conditions strengthened considerably such that by the 1960s much of the worst of the East End sweated trades had disappeared and furniture work had become one of the better-paid trades.Footnote84

Modernizing production

Not only did good labour relations provide a platform for the transformation of production, but also technological and organizational lessons were learnt during the war. Some of these were directly attributable to the Utility scheme. As reported to Maurice Jay in 1965, furniture manufacturer Leslie Gomme, whose firm went on to develop the well-known G-Plan range, indicated that ‘ … the Utility scheme [was] a godsend to the furniture industry’:

‘It opened our eyes,’ he told me, ‘to what could be done when a limited number of designs is produced in large quantities. When freedom of design was restored, there was an immediate return to the proliferation of designs of the prewar era. Our profits dropped slightly and we realised that we were unable to utilise our factories efficiently because of the multiplicity of designs that the trade demands’.Footnote85

All were quite fundamental in establishing the technological base for the furniture industry of the post-war years, as well as the management/control function of this now technologically rather than craft based industry.Footnote86

Im/moral geographies

Our evaluation of the Utility furniture scheme has shown the enduring impact of its interventions and underpinning through a set of morally virtuous discourses, both features of which are captured by Labour MP for Edmonton Austen Albu’s address to Parliament at the end of the scheme where he characterizes it

… as a guarantee of quality in the difficult times which we were passing through, so as to be able to supply furniture of a reasonably decent design and quality to people building up homes for the first time, or people who had been bombed out of their homes. The scheme was very popular during those war years, and the word ‘Utility’ became, in the words of my right hon. Friend [H Dalton], a ‘noble title.’ No one will deny the influence which this scheme has had on standards in the furniture industry, not only during the war but after the war, when there was very considerable modification and relaxation.Footnote87

Highlighting the particular moral geographies of production and supply that Utility set in train both during and after the war further enables us to emphasize that moral geographical outcomes are not fixed or guaranteed. The Second World War saw varying geographies of bombing across Europe as well as disparate responses to wartime aerial bombardment and their moral geographies. Commenting on the relative ‘success’ of British rationing schemes, Waller has written that the black market in the immediate post-war period:

bore no comparison with the black market in newly liberated Paris, which in the absence of rationing to ensure fair shares for all, was raging out of control […] In England, where there was an ordered rationing system which had public support, the black market operated on the fringes.Footnote88

Comparison with the moral complexities and spatialities of Nazi Germany is also insightful in this respect. In Germany, compensation paid to bombed householders had its roots in reparation arrangements developed during the Franco-Prussian war, allowing civilians in need to claim cash or materials from war damage offices administered by local authorities.Footnote89 Süss reports that the War Damage Legislation in Germany (KSR: Kreigsschädenrecht) was explicitly viewed by the Nazi administration as ‘much more comprehensive, more equitable and more robust’ than equivalent British legislative model.Footnote90 German war damage offices were required to be ‘fast, generous and unbureaucratic in their granting of compensation of ‘national comrades’, with one clear exception: Jews were excluded from any compensation.Footnote91 Not only were Jews prohibited from making claims, but Jewish property was:

regarded by the local compensation offices as an important resource they controlled and that could be used in the interests of the ‘national community’ to provide victims of bombing with furniture, household goods and living quarters.Footnote92

Between March 1942 and July 1943 Hamburg alone received 45 shiploads from Holland, containing 27,000 metric tons of furniture, household goods and clothing that were intended primarily for the victims of bombing. In total some 100,000 inhabitants of the city and the surrounding area are likely to have benefited between 1941 and 1945 from plundered Jewish property, which in the words of one of the auctioneers speaking after the war went ‘for the most part for knockdown prices’ without arousing significant moral qualms.Footnote93

The later history of London’s furniture trades provides further insight. Whilst Utility helped to launch a period of post-war growth in output and labour conditions, by the 1970s, the fragility of such achievements became apparent as the industry entered a period of crisis and rapid decline. Increased competition both with more highly capitalized industries in some countries and with low wage production in others became highly problematic for remaining London firms. One response was the cheapening of production costs through the use of immigrant labour in anti-union establishments, which was to leave the industry as fragmented and divided as it had been in the nineteenth century.Footnote97

Conclusion

Whilst dominant reconstruction narratives of bombed cities such as London have tended to focus on the physical renewal of the post-war built environment and public or civic architectures of planning and building, our consideration of the Utility furniture scheme emphasizes that the material destruction of London’s houses and homes also necessitated a pragmatic reworking of household provisioning and of the networks through which the material objects of the home were supplied. The paper illustrates the ways in which — alongside the immoralities inherent in the direct consequences of the bombing of London for consumers and makers of furniture — governmental response was shaped by longer-standing moral concerns about furniture production, distribution, and consumption that were grounded in specific discourses regarding the character of the London’s furniture trades, particularly in its traditional East End location. Moreover, we have shown that the Utility scheme was to have important and enduring impacts and resonances during London’s peacetime reconstruction. The paper has delineated the entanglements involved in the making and remaking of moralities across spaceFootnote98 and in particular the role of collective and institutional responses to the bombed city.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the anonymous referees for their comments; and to Lyn Aspden and Julia Branson at the School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Southampton for their work in preparing . Many thanks also to Sam Johnson-Schlee for the organization of Bombsites/Building Sites: A symposium on post destruction urban cultures held at London South Bank University, at which an earlier version of this paper was presented.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Suzanne Reimer

Dr Suzanne Reimer is an Associate Professor at the University of Southampton. Her research interests centre upon aspects of design, creativity, and knowledge, including the gendering of creativity and design labour. Suzanne has ongoing interests in the furniture industry; modernism and design; and moto-mobilities.

Philip Pinch

Dr Philip Pinch is an Associate Professor at London South Bank University. His research crosscuts the fields of planning, politics and spatial governance, including work on territorial cohesion and the economic potential of rural areas within Europe. Philip also has interests in landscape strategies for minerals planning; and in urban rivers and ‘waterspace’ planning. He is currently engaged in research on moto-mobilities and design.

Notes

1 ‘The word “Blitz” is derived from the German term “Blitzkrieg” (lightning war) and is associated with a period of continued aerial bombing by the Germans on Britain’ between 7 September 1940 and 11 May 1941 (http://bombsight.org/faq/)

2 M. Denney, ‘Utility Furniture and the Myth of Utility 1943–48’, in J. Attfield (ed.), Utility Reassessed: The Role of Ethics in the Practice of Design (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), 110–24: quotation 120. More broadly, the contributors to the edited volume seek to draw out the development and application of ‘ethical principles’ through Utility (J. Attfield, ‘Introduction’, 1–10, in Utility Reassessed), 3).

3 P. Pinch and S. Reimer, ‘Nationalising local sustainability: lessons from the British wartime Utility scheme’, Geoforum, 65 (2015), 86–95; S. Reimer and P. Pinch, ‘Geographies of the British government’s wartime Utility furniture scheme, 1940–1945’, Journal of Historical Geography, 39 (2013), 99–112.

4 T. Cresswell, ‘Moral Geographies’, in D. Atkinson, P. Jackson, D. Sibley, and N. Washbourne (eds.), Cultural Geography: A Critical Dictionary of Key Concepts (London: I.B. Taurus, 2005), 128–34: quotation 130. Cresswell refers directly to work on social justice by D. Harvey, Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996) and D.M. Smith, Moral Geographies: Ethics in a World of Difference (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000). See also D.M. Smith, ‘Morality, Ethics and Social Justice’, in P. Cloke et al. (eds), Envisioning Human Geographies (London: Routledge, 2004), 195–209.

5 F. Driver, ‘Morality, Politics, Geography: Brave New Worlds’, in C. Philo (ed.), New Words, New Worlds: Reconceptualising Social and Cultural Geography (Lampeter: Department of Geography University of Wales at Lampeter, 1991), 61.

6 J.L. Oliver, ‘The East London furniture industry’, East London Papers, 4 (1961), 88–101; J.L. Oliver, ‘The location of furniture manufacture in England and elsewhere’, Tijdschrift voor Economishe en Sociale Geographie, 55 (1964), 49–48; J.L. Oliver, The Development and Structure of the Furniture Industry (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1966); P.G. Hall, The Industries of London since 1861 (London: Hutchinson University Library, 1962).

7 See, in particular Hall, 71–81.

8 Cresswell, 130.

9 C. Philo, ‘Delimiting Human Geography: New Social and Cultural Perspectives’, in C. Philo (ed.), New Words, New Worlds: Reconceptualising Social and Cultural Geography (Lampeter: Department of Geography University of Wales at Lampeter, 1991), 16; see also Driver, note 5.

10 G. Garelli and M. Tazzioli, ‘Arab Springs making space: territoriality and moral geographies for asylum seekers in Italy’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31 (2013), 1004–21; quotation 1013.

11 K. Hewitt, ‘Place annihilation: area bombing and the fate of urban places’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 73 (1983), 57; see also D. Gregory. ‘“Doors into Nowhere”: Dead Cities and the Natural History of Destruction’, in P. Meusburger, M. Heffernan, and E. Wunder (eds.), Cultural Memories (Dordrecht: Springer, 2011), 249–83.

12 P. Kirkham, R. Mace and J. Porter, Furnishing the World: The East London Furniture Trade 1830–1980 (London: Journeyman, 1987), 27, reports that the Mosquito became known as ‘the cabinet makers plane’.

13 E. Aves, ‘The Furniture Trade’, in Charles Booth, Life and Labour of the People in London: First Series: Poverty Vol. 4 The Trades of East London Connected with Poverty (London, Macmillan and Co., Ltd, 1902), 164.

14 Hall, 85–86, which is taken directly from the narrative in Aves, ‘The Furniture Trade’, 175–76.

15 ‘During the years 1890 and onwards, land developers could be seen in every road where there were houses which had gardens in the rear. The gardens were bought from the landlord and the builders would put up small workshops which were let to cabinet makers. […] There was no entrance or exit for the workmen and their work had to be carried through the passage-way of the houses. So one can guess at the filthy conditions of the premises’. R. Samuels, East End Underworld: Chapters in the Life of Arthur Harding (London: Routledge, 1981), 96.

16 First report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Sweating System, PP 1888 (361); C. Booth, ‘Sweating’, in Charles Booth, Life and Labour of the People in London: First Series: Poverty Vol. 4 The Trades of East London Connected with Poverty (London, Macmillan and Co., Ltd, 1902), 328–47; Aves, ‘The Furniture Trade’, 157–218; H.L. Smith, The New Survey of London Life and Labour, Volume II: London Industries (London: P.S. King and Son, 1931).

17 Smith, New Survey, 232.

18 Findings and Decisions of a Sub-Committee Appointed by the Standing Committee on the Investigation of Prices to Investigate Costs, Profits and Prices at all Stages in Respect of Furniture, London, 1920, Cmd. 983, 11.

19 C. Edwards, ‘Tottenham court road: the changing fortunes of London’s furniture street’, The London Journal, 36 (2011), 143. Mayhew’s ‘honourable/dishonourable’ distinction is cited at page 143: see especially note 15.

20 Aves, 163.

21 C. Booth, ‘Sweating’, in Life and Labour of the People in London: First Series: Poverty Vol. 4 The Trades of East London Connected with Poverty (London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd, 1902), 339–40.

22 Cited in C.D. Edwards, 2012. ‘“Art Furniture in the Old English Style”: the Firm of Collinson and Lock, London, 1870–1900’, West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture, 19 (2012), 258

23 L. Smith, ‘Greeners and Sweaters’, Jewish Historical Studies, 39 (2004), 105.

24 Smith, ‘Greeners and Sweaters’, 104.

25 Aves, 173.

26 Aves; see especially 191–92.

27 Smith, New Survey, 222.

28 M.J. Daunton, ‘Industry in London: revisions and reflections’, The London Journal, 21 (1996), 2.

29 G. Riello, ‘Boundless competition: subcontracting and the London economy in the late nineteenth century’, Enterprise & Society, 13 (2012), 528.

30 Daunton, 2.

31 Riello, 528. Benson’s account of ‘penny capitalism’ calls strongly for consideration of ‘the kinds of local economy that sustained it’ (J. Benson, The Penny Capitalists: A Study of Nineteenth Century Working-class Entrepreneurs (Gill and Macmillan, 1983), 6). See also Benson’s citation of Mayhew’s discussion of ‘garret masters’ in the London furniture trade, 46–47.

32 G. Steadman Jones, Outcast London: A Study in the Relationship Between Classes in Victorian Society (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, [1971] 2002), 23.

33 WP, 11–12.

34 WP, 11.

35 E.L. Hargreaves and M.M. Gowing, Civil Industry and Trade (London, HMSO/Longmans, 1952), 513.

36 WP, 68.

37 Kirkham et al., 27.

38 D. Thomas, The Enemy Within: Hucksters, Racketeers, Deserters and Civilians During the Second World War (New York: New York University Press, 2004), 77–78.

39 Thomas, 124. Zinkins was a Hackney firm designated to supply Utility furniture in February 1944 (see ). One of the family members (Jacob Zinkin) later worked for Lebus.

40 M. Roodhouse, Black Market Britain: 1939–1955 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 48.

41 Roodhouse, 48. The potential complexity of the wartime black market in coupons is captured in Samuel’s East End Underworld, the oral history of ‘professional criminal’ Arthur Harding, who during the war was involved in ‘the old clothes business’: ‘People came in to sell clothing coupons, I used to give £3 a book, but I never sold them for money, only exchanged them for second-hand clothes. Mind you I made a great bargain out of it, for £3 I might get £20 of clothing back. I could never understand why wealthy people risked their reputation and character in order to get something the rest of the community wasn’t getting. The poorer people used to sell the coupons, because they couldn’t afford to buy new clothes, so I exchanged them for old clothing. It was the better off people who bought them … ’ (Samuels, 260). Parallel practices of coupon trafficking are likely to have taken place for furniture.

42 Roodhouse, 256. Roodhouse (78) refers to Smithies’ assessment ‘that overcharging, imposing conditions of sale, and coupon-free sales were rife, while illicit manufacturing fed local markets in luxuries and home comforts such as cosmetics and toys’. (E. Smithies, The Black Economy in England since 1914 (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1984), but at the same time emphasizes that Smithies’ reliance upon court reports in the local press, whilst illuminating ‘how people evaded the regulations’, is not able to describe ‘how illegal markets functioned’.

43 Hargreaves and Gowing, 335.

44 Reimer and Pinch, 107.

45 Suggestions for completing designation of manufacturers of utility furniture, 8 May 1943, Board of Trade, Correspondence re designation, TNA BT 64/1816.

46 Oliver, Development and Structure, 167; see also H. Reid, The Furniture Makers: A History of Trade Unionism in the Furniture Trade 1868–1972 (Oxford: Malthouse Press, 1986), Chapter IX.

47 Kirkham et al., 29.

48 Kirkham et al., 90.

49 Oliver, Development and Structure, 166.

50 Memorandum, n.t., 3 July 1942, Board of Trade, Advisory Committee on Utility Furniture, TNA BT 64/1835.

51 Memorandum, BT 64/1835.

52 Memorandum, n.d., Board of Trade, Utility Furniture. General Policy, TNA, BT 64/2052

53 ‘Suggestions for Completing Designation of Manufacturers of Utility Furniture’, n.d., Board of Trade, Correspondence re designations, TNA, BT 64/1816.

54 Reid, 158.

55 WP, 69.

56 WP, 69.

57 Hargreaves and Gowing, 521.

58 1931 Census of Population records were destroyed by fire; and a 1941 Census did not take place because of the war.

59 Final Report on the Census of Production, London, 1944

60 Oliver ‘The East London furniture industry’, 8.

61 Kirkham et al., 27.

62 Board of Trade, Correspondence re designations, TNA, BT 64/1816.

63 Correspondence to members of Utility Distribution Committee, February 1944, Board of Trade, Utility Furniture Distribution Committee, TNA BT 64/1749.

64 ‘Utility Furniture Production’ memorandum, 30 October 1944, Board of Trade, Advisory Committee on Utility Furniture, TNA BT 64/1835.

65 Charles H. Walker, Memorandum: Utility furniture: production and demand to August 1944, dated 19 September 1944, 5, Board of Trade, Utility Furniture Policy 1944/46, TNA BT 64/2825.

66 ‘Utility Furniture Production in July 1944’, memorandum, 6 September 1944, Board of Trade, Advisory Committee on Utility Furniture, TNA BT 64/1835.

67 ‘Utility Furniture Production’ memorandum, 30 October 1944, Board of Trade, Advisory Committee on Utility Furniture, TNA BT 64/1835.

68 Letter from President of the Board of Trade Hugh Dalton, 12 August 1943, Board of Trade, Utility Furniture 1944/46, TNA BT 64/2825.

69 Reimer and Pinch, 99; see also C.D. Edwards, Twentieth-century Furniture: Materials, Manufacture and Markets (Manchester, 1994), 141.

70 Kirkham et al., 31.

71 Oliver, Development and Structure, 99.

72 Oliver, Development and Structure, Table 30, 101.

73 Oliver, Development and Structure, Table 36, 107.

74 See note 6.

75 See, in particular, the debate at Hansard, January 1953 ‘Furniture (D Scheme) HC Deb 21 January 1953 vol 510 cc 211–319.

76 WP, 92. This characterization of (e.g.) ‘certain evils’ (13); ‘serious pre-war evils’ (204) are prevalent throughout the text.

77 WP, 31.

78 WP, 93.

79 WP, 15.

80 Report of Furniture Production Committee, n.d. ‘Furniture’, Board of Trade, Policy File: Control of Furniture Production, 1947 TNA BT 64/2092, 3.

81 Reid, 162.

82 Reid, 164.

83 Reid, 165–66.

84 Reid’s index of basic weekly wage rates displays furniture workers ‘at the top of the league table’, 172.

85 Reported in M. Jay, ‘Design management: Furniture: autocracy versus organisation’, Design, 195 (February 1965), 50.

86 Reid, 158.

87 Hansard, 21 January 1953, cc 229.

88 M. Waller, London 1945: Life in the Debris of War (London: John Murray, 2004), 263.

89 D. Süss, Death from the Skies: How the British and Germans Survived Bombing in World War II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 160.

90 Süss, 160.

91 Süss, 163.

92 Süss, 163.

93 Süss, 188.

94 Jewish Museum Berlin, Raub und Restitution <https://www.jmberlin.de/raub-und-restitution/en/glossar_m.php> [accessed 20 November 2018]. See also S. Fogg, ‘“Everything had ended and everything was beginning again”: The public politics of rebuilding private homes in postwar Paris’, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 28 (2014), 277–307.

95 J-M. Dreyfus and S. Gensburger, Nazi Labour Camps in Paris: Austerlitz, Lévitan, Bassano, July 1943–August 1944 (New York: Berghahn, 2011).

96 Dreyfus and Gensburger, 17

97 Kirkham et al., 95; see also Greater London Council, London Industrial Strategy (London: GLC, 1985), 97–116; J. Smith and R. Rogers, Behind the Veneer: The South Shoreditch Furniture Trade and Its Buildings (London: English Heritage, 2006).

98 Smith, Moral Geographies, 5.